Origins of US Congress: Continental Congress & Constitution

advertisement

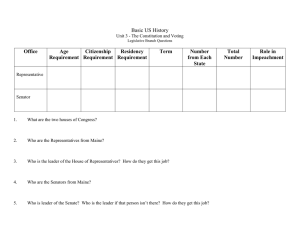

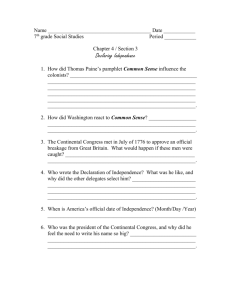

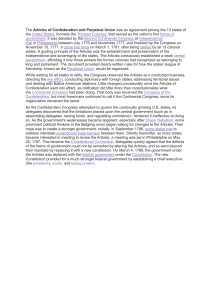

The origins of today's Congress may be traced back to the American Revolution. In the fall of 1774, fiftysix men from twelve of the thirteen colonies gathered in Philadelphia. The First Continental Congress met here. They demanded that the British government recognize the colonists' rights as Englishmen. They were dissatisfied with the British answer. So, they reconnected in 1775. In 1776, fifty-five individuals at the Second Continental Congress signed the Declaration of Independence after a year of deliberation. The pamphlet details the atrocities committed by the King of the United Kingdom. The Declaration then declares, "These United Colonies are Free and Independent States." Following the American Revolution, the states were unified. However, the central government proved ineffective. Each state is in charge of its own money, trade, and army. Many state leaders want a more powerful federal government. In February 1787, they asked for a Constitutional Convention to be held in Philadelphia. Convention on the Constitution: State representatives collaborated on a strategy for governing the United States for seven months. They established the present congress with two houses. The House of Representatives was the "lower house" based on population. The "upper chamber," known as the Senate, was composed of two senators from each state. Other debates took up more time. Exhausted by the lengthy spring and summer of work, thirty-nine men from thirteen states signed the final text of the Constitution on September 17, 1787. After that, the Constitution had been accepted or ratified by nine states by June 1788. It became the nation's fundamental legislation. In September 1789, the first 10 amendments, or Bill of Rights, were offered. The states adopted the revisions in less than two years. The work of the previous Continental Congress was completed. It established a federal government with a powerful legislature that remained for more than two centuries. The history of the house of the senate: