Cured (Jeffrey Rediger, M.D. [Jeffrey Rediger, M.D.]) (z-lib.org)

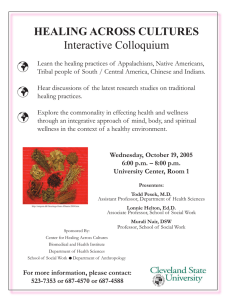

advertisement

![Cured (Jeffrey Rediger, M.D. [Jeffrey Rediger, M.D.]) (z-lib.org)](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/026226598_1-b4843893be6b23171ae1d7cd01fa3803-768x994.png)