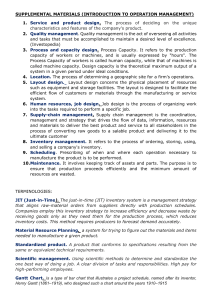

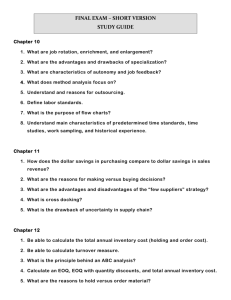

Course Content SECTION A Overview of Operation Management Unit 1: Introduction to Operations Management 1. Scope of Operations Management Operations management is about the management of the processes that produce or deliver goods and services. Not every organisation will have a functional department called ‘operations’, but they will all undertake operations activities because every organisation produces goods and/or delivers services. The operations manager will have responsibility for managing the resources involved in this process. Positions involved in operations have a variety of names, and may differ between the manufacturing and service sectors. Examples of job titles involved in manufacturing include logistics manager and industrial engineer. Examples in the service industry include operations control manager (scheduling flights for an airline), quality manager, hotel manager and retail manager. People involved in operations participate in a wide variety of decision areas in an organisation, examples of which are given below: • Service Operations: How do we ensure customer receives a prompt service? • Operations Strategy: What strategy should be followed? • Operations Performance: How do we measure the objectives performance of our operations processes? • Process: Types How do we configure the process which will deliver our service to customers? • Layout Design: How do we organize the physical layout of our facilities and people? • Long-term Capacity: How do we ensure we have Planning the correct amount of capacity available when needed? • Facility Location: What should be the location of our operations facilities? • Process Technologies: What role should technology have in the transformation of materials in the operations system? • Designing Products: What products and services and Services should the organization provide? • Process Design: How do we design the service delivery process? • Job Design: How do we motivate our employees? • Planning and Control: How do we deploy our staff day-to-day? • Capacity Management: How do we ensure that our service is reliably available to our customers? • Inventory Management: How can we keep track of our inventory? • Lean Operations and JIT: How do we implement lean operations? • Enterprise Resource: How do we organise the Planning movement of goods across the supply chain? • Supply Chain Management: What benefits could e-procurement bring to our operations? • Project Management: How do we ensure our projects finish on time and within budget? • Quality: How can we implement a TQM programme? • Operations Improvement: How do we improve our operations performance over time? Page 1|1 Operations management covers a very wide scope: Operation Management Elements Operations management is important. 1. It is concerned with creating the services and products upon which we all depend. All organizations produce some mixture of services and products, whether that organization is large or small, manufacturing or service, for profit or not for profit, public or private. Thankfully, most companies have now come to understand the importance of operations. This is because they have realized that effective operations management gives the potential to improve both efficiency and customer service simultaneously. But more than this, operations management is everywhere, it is not confined to the operations function. All managers, whether they are called Operations or Marketing or Human Resources or Finance, or whatever, manage processes and serve customers (internal or external). This makes at least part of their activities ‘operations’. Operations management is also exciting. 2. It is at the center of so many of the changes affecting the business world – changes in customer preference, changes in supply networks brought about by internet-based technologies, changes in what we want to do at work, how we want to work, where we want to work, and so on. There has rarely been a time when operations management was more topical or more at the heart of business and cultural shifts. Operations management is also challenging. 3. Promoting the creativity which will allow organizations to respond to so many changes is becoming the prime task of operations managers. It is they who must find the solutions to technological and environmental challenges, the pressures to be socially responsible, the increasing globalization of markets and the difficult-to-define areas of knowledge management. Major Functions For operations management The operations function is central to the organization because it creates and delivers services and products, which is its reason for existing. The operations function is one of the three core functions of any organization. These are: The marketing (including sales) function – which is responsible for ● communicating the organization’s services and products to its markets in order to generate customer requests. The product/service development function – which is responsible for ● coming up with new and modified services and products in order to generate future customer requests; The operations function – which is responsible for the creation and delivery ● of services and products based on customer requests. Operations Management perspectives: Operations Management can be viewed from three perspectives. 1. Organisational perspective Operations Management can be understood from the organisational point of view by taking into consideration factors that are under the control of the organisation and disregarding all other factors that affect organisational performance. 2. Systems perspective A systems view of Operations Management that is more comprehensive than the organization’s view and it takes into consideration the fact that organizations do not operate in a vacuum, hence are affected by the environment in which they operate. Therefore, an Page 2|1 organisation has to coexist and interact with its environment in order to effectively achieve its objectives. 3. Supply Chain perspective Viewing Operations management in a supply chain perspective puts more emphasis on the organisation’s supply side, but being cognisant of the complexities and importance of dealing with suppliers in the manner that achieves value addition to the organisation. It also emphasises on the transformational processes of the buying organisation to ensure efficiency and effectiveness. Importantly also, it emphasises on the demand side of the organisation by appreciating the complexity and importance of satisfying customer requirements. Need for Operations Management In general, Operations management is a strategic capability which greatly impacts on business performance and profits directly. It is therefore important to study and properly manage Operations in order to achieve enhancement in the following: 1. Product/Service design Proper Operations management will create opportunities by designing and bringing to the market new or improved products or services that posses characteristics that are attractive to the intended customers thereby increasing sales and revenue. 2. Process design Due to proper Operations management, processes that are involved in creation of products and services are analyzed and designed to provide convenience and time/cost savings for both the producer and the customer, thereby increasing revenue. 3. Efficiency and effectiveness People that have studied and apply Operations management skills in organizations will become efficient and effective. For those in finance, making an audit of inventory turnover and provide recommendations (the number of times inventory is sold and replaced) becomes simple if one can asses the underlying operational reasons. For marketers, a promise to customers on speed of delivery of a product or service can only be genuine after considering the operational capabilities of the business. In Human Resource, appropriate recruitment and staff management can only be effective if skills needed for operational activities are analyzed. 4. Customer service Well managed organization operations will lead to production of optimum quantities that reduce holding costs, and at the same time meeting expected demand and agreed time of delivery. 5. Adaptability for future survival. Organisations have to stand a test of time even when they are operating in a fast changing environment. Operations management will ensure flexibility of organisations in meeting customer demands. For example, if capacity of a business’ facilities and machinery are designed to accommodate future expansion, it is easy for such a business to cope with a sudden rise in product or service demand, thereby leading to customer satisfaction. Support Functions For operations management In addition, there are the support functions which enable the core functions to operate effectively. These include: the accounting and finance function, ▪ the technical function, ▪ the human resources function, ▪ the information systems function. ▪ Page 3|1 Remember that different organizations will call their various functions by different names and will have a different set of support functions. Almost all organizations, however, will have the three core functions, because all organizations have a fundamental need to sell their products and services, meet customer requests for services and products, and come up with new services and products to satisfy customers in the future. The relationship between major functions and support functions are illustrated below: What Operations Management is involved in: a. Forecasting and planning on: i. Products and services: What should we be producing and what will be our market? ii. Make or buy: What will we be doing ourselves and what will we be outsourcing form service providers. This decision has an impact on costs as well as quality of products or services. iii. Capacity: How much should we be producing and how much should be the maximum production capability should our plant have. Capacity decisions influence operating costs and the ability to respond to customer demand. iv. Location: Where should we locate our office facilities, production plant, distribution centers, etc. Location decisions among others, impact transportation costs, labor availability, material costs, and access to markets. b. Organising Organisational structure: Which and how many departments are we going to have and which and how many units will be in such departments. This determines the size of the organisation (hence costs), organisation of actual work (who will be doing what) and chain of command. It also affects career progression and employee motivation. c. Staffing This involves hiring and laying off decisions. Staffing determines what skills and competencies to hire (temporarily or permanent) in an organisation and ensure proper motivational initiatives that add value to the organisation. These decisions affect a business’ Page 4|1 labour attractiveness and staff turnover, which consequently affects consistency of quality and services produced. d. Directing This relates to the chain of command laid down by the organisational structure. It involves issuance of work orders and providing leadership to those responsible for assigned work to perform accordingly. e. Controlling This ensures that everything pertaining to the organisation occurs in conformity with the plans laid down. It ensures that at intervals, predetermined plans are compared with the actual performance. This has a very direct impact on costs, as well as the quality of products and services produced. f. Budgeting Operations management also involves financial planning so that costs of running the business should not exceed the revenue earned from spending on organisational activities. This has a direct bearing on profitability of the business. 2. Operations Management and decision making Decision-making is the process of choosing a course of action from among alternatives to achieve a desired goal. It is one of the important aspects in operations management. Characteristics of decision making process: 1. Decision making is a selection process. The best alternative is selected out of many available alternatives. 2. Decision-making is a goal-oriented process. Decisions are made to achieve some goal or objective. 3. Decision making is the end process. It is preceded by detailed discussion and selection of alternatives. 4. Decision making is a human and rational process involving the application or intellectual abilities. It involves deep thinking and foreseeing things. 5. Decision making is a dynamic process. An individual takes a number of decisions each day. Operations Management and decision making Terry GR Lays’ decision making sequence: Determining the problem. Acquiring general background information and different viewpoints about the problem. State what appears to be the best course of action. Investigate alternative solutions. Evaluate the alternative solutions. Select the best alternative and implement. Institute follow up and modify the decision the possible necessary. In managing operations, it is vital to make sure that a proper decision-making process has been followed in the pursuit of coming up with a good and right decision, whilst avoiding wrong and bad decisions. A wrong decision cannot be avoided because you make the best decision out of the wrong information available (it is a mistake every manager is bound to make). A bad decision however is made after knowing all the correct facts on the high chances of the decision not bearing fruits (for example launching a product after experts have warned you of its faulty characteristics). Page 5|1 Types of decisions in Operations Management Operations management make strategic as well operational decisions. 1. Strategic decisions These are decisions that have a long-term effect as well as affecting the entire business. Because they influence a larger part of the system, it is extremely undesirable and difficult to undo them when implemented. They also require more resources, skills as well as judgement. It is therefore important for operations managers to be very certain on the implementation of these decisions. These decisions must be made by top level managers in collaboration with each other for them to have a harmonizing effect across the entire organization. Below are examples of strategic decisions that operations are supposed to make: Product selection and design-what product to offer. This has a long term effect as well as greatly impact on the overall performance on the market against competitors. In essence, this decision will define the business’ survival. Process selection and planning-choosing optimal process and detailing the processes of resource conversion required. Facilities location-location of production systems or facilities (warehouses, distribution centers, offices, etc.). Facilities layout and materials handling-this is the orderly and logical designing of activity centers in order to facilitate materials flow, reduce handling costs, and minimize delays. Capacity planning-acquisition of productive resources. (capacity: maximum available amount of output of the conversion process over some specified time span 2. Operational decisions These decisions deal with short term planning and control of problems. Mostly, they are routine decisions related with general functioning of the organisational operations. They do not require much evaluation and analysis and can be carried quickly. Ample powers to carry out these decisions should be delegated to middle and lower ranks. Production scheduling and control-determine optimal schedule and sequence of operations, economic batch quantity, machine assignment, etc. Production control is a follow up of the production plans laid down by top management. Inventory planning and control-determining optimal inventory levels at raw material, WIP and finished goods. Quality control and assurance-ensuring that whatever product/ service that is produced satisfies the quality requirements of the customer. Work design-design of work methods, systems and procedures (e.g. Job enlargement), design of work incentives. Maintenance and replacement-optimal policies for repetitive, scheduled and breakdown maintenance of machines, replacement decisions. 3. Importance of Studying Operations Management Why study Operations Management These are a total sum of efforts and processes that are carried out in order to create value for the consumers in the form of products or services. It can therefore be said that operations as a total some of processes, encompasses production, hence for most authors, they emphasize their discussion on ‘operations management’. Operations can also be viewed as a part of an organization, a function among other organisational functions. Page 6|1 Below are the generic/basic functions of organisations: Marketing- Generates demand (sales promotion, advertising, market research). Finance/accounting–Tracks how well the organization is doing, pays bills, collects the money, investments. Human Resources–Provides labor, wage and salary administration and job evaluation, recruitment. Operations–Creates the product/ services (facilities layout, product development and design, capacity planning). With this view, Operations is said to be one of very core functions of any organisation, that is devoted to the production or delivery of goods and services. In affirming the importance of Operations, Porter (1985) include the Operations function among the primary activities of organisations. Types of Operations: Physical: Farming, Mining, Construction, Manufacturing, Power generation, etc. Locational: Warehousing, Trucking, mail service, moving, taxis, airlines, etc. Exchange: Retailing, wholesaling, banking, renting or leasing, etc. Entertainment: Films, radio and television, plays, concerts, etc. Informational: Newspapers, radio and television, telephone, satellites, the internet, etc. Physiological: Healthcare. Inputs (Doctors, Nurses, Medical supplies, Equipment, Laboratories, etc.), Processing (Examination, Surgery, Monitoring, Medication, Therapy, etc.), and Output (Healthy patients) 4. Historical evolution of Operations Management Systems of production have been in existence since ancient times. This is evidenced by historical features that we see for example the great wall of china built by Chinese emperors (220-206 BC) that stretches to 21,196km, Egyptian pyramids (around 600 BC), ships built by the Spanish and roman empires, roads and aqueducts, etc. Although these ancient works are public works, they provide proof of the human ability to organize themselves and materials for production. The production of goods for sale, in the modern sense, and in the factory systems that are in existence can be traced from how it began and how such systems of production keep on changing. The Industrial Revolution The Industrial Revolution was basically a transition on methods and systems of manufacturing. It began in the 1770 sin England and spread to the rest of Europe and to the United States during the 19thcentury. Prior to the Industrial Revolution period, goods were produced in small shops by craftsmen and their apprentices. Under the craft production system, it was common for one person to be responsible for making a product in its entirety, such as a horse-drawn wagon or a piece of furniture, from start to finish. It required high skills yet simple tools to produce and the products were usually unique each time they are produced. Craft production system had major shortcomings. Because products were made by skilled craftsmen who custom fitted parts, production was slow and costly. And when parts failed, the replacements also had to be custom made, which was also slow and costly. Page 7|1 Another shortcoming was that production costs did not decrease as volume increased; there were no economies of scale, which would have provided a major incentive for companies to expand. Instead, many small companies emerged, each with its own set of standards. Due to high demand of products, a number of innovations changed the methods of production by substituting machine power for human power. The most significant of these was the steam engine, made practical by James Watt around 1764, because it provided a source of power to operate machines in factories. The availability of coal supplies and iron ore provided materials for generating power and making machinery. The new machines, made of iron, were much stronger and more durable than the simple wooden or rough iron machines that were being used in the craft production system. Because of use of durable machines, volume of production increased, Costs were reduced because of economies of scale, and also time of production was greatly reduced. The Industrial Revolution era was further advanced with the invention of the gasoline engine and electricity in the 1800s. Scientific Management This era started around 1880s and gained more popularity in the 1910s. The scientific management era brought widespread changes to the management of operations in the factories. The movement was spearheaded by the efficiency engineer and inventor Frederick Winslow Taylor, who is often referred to as the father of scientific management. Taylor believed in a "science of management" based on observation, measurement, analysis and improvement of work methods, and economic incentives. He studied work methods in great detail by conducting stopwatch studies in order to establish standard output per worker on each task, as well as to identify the best method for doing each job. 1. Competitiveness, strategy and productivity Competitiveness In business, the name of the game is competition. Those who understand how to play the game will succeed, those who don’t are doomed to failure. It should be noted that this game is not just a company against other companies. In companies that have multiple factories or divisions producing the same item or service, factories or divisions sometimes find themselves competing with each other. When a competitor (another company or sister factory or division) can turn out products better, cheaper, and faster; that spells real trouble for the factory or division that is performing at a lower level. Consequences can be layoffs or shutdown if managers cannot turn things round. The bottom line is better quality, higher productivity, lower costs, and the ability to quickly respond to customer needs. It is therefore incumbent for businesses to develop solid strategies for dealing with these important issues in business. Competitiveness is a measure of how effectively an organization meets the needs of customers relative to others that offer similar goods or services. It is an important factor in determining whether a company prospers, barely gets by, or fails. Quality refers to materials and workmanship, as well as design. Usually, it relates to a buyer's perceptions of how well the product or service will serve its intended purpose. Other businesses choose to compete by offering products that customers will eventually consider having better characteristics than those of competitors. Page 8|1 Producer service differentiation refers to any special features (e.g., ease of use, convenient location) that cause a product or service to be perceived by the buyer as more suitable than a competitor's product or service. Flexibility is the ability to respond to changes. The better a company or department is at responding to changes, the greater its competitive advantage over another company that is not as responsive. The changes might relate to increases or decreases in volume demanded, or to changes in the design of goods or services. Time refers to a number of different aspects of an organization's operations. Another is how quickly new products or services are developed and brought to the market. How quickly a product or service is delivered to a customer. This can be facilitated by faster movement of information backward through the supply chain. Another is the rate at which improvements in products or processes are made. Service might involve after-sale activities that are perceived by customers as value added; such as setup, warranty work, technical support, or extra attention while work is in progress, such as courtesy calls and keeping the customer informed. Strategy In developing strategies that are to achieve competitive advantage, a business needs to identify which elements are order qualifiers and which ones are order winners. This concept was developed by Terry Hills (1993). Hills states that order qualifiers are those characteristics that the company must comply with to be considered as a possible supplier. Having a good performance in these characteristics, however, is not enough to win the orders, and exceeding the threshold limit for these factors influences nothing or very little in the customer final decision. These characteristics are considered by potential customers as minimum standards of acceptability to be considered as a potential for purchase. On the other hand, order winners are characteristics of an organization's goods or services that cause them to be perceived as better than the competition. These characteristics are those that make up the company differentiation in comparison to the competitors and allow businesses that hold them to win business. The higher a business scores in these factors, the higher the chances of winning the order. Both groups of criteria are essential to the business success. Therefore, suppliers must guarantee meeting the qualifying criteria in order to get into and stay in a market place, while performance in the order winning criteria is the key to win the battle for customers’ preference. Whilst in the drive to achieve competitive advantage over others in the industry, it is important that ethical behaviour on the part of the organisation as well as its employees is always regarded. Managers have to be vigilant and ensure that all rules and regulations that govern the industry are being followed. Also, it is important that focus is not only emphasised on the internal organisational activities. Focus has to be broadened by considering the entire supply chain and environment in which the business is operating. Organizations fail, or perform poorly, for a variety of reasons. Being aware of those reasons can help managers avoid making similar mistakes. Among the chief reasons for failure are the following: Putting too much emphasis on short-term financial performance at the expense of long term goals through research and development. Failing to take advantage of strengths and opportunities, and/or failing to recognize competitive threats. Neglecting operations. Page 9|1 Placing too much emphasis on product and service design and not enough on process design and improvement. Neglecting investments in capital and human resources. Failing to establish good internal communications and cooperation among different functional areas. Failing to consider customer wants and needs. Productivity This is a measure of the effective and efficient use of resources; hence it is an objective measure of efficiency on resource utilization usually expressed as a ratio of output to input(output/input). It is a quantitative relationship between what we produce and what we have spent to produce. Since it is a measure of efficiency, higher productivity means lower costs of production as well as higher profitability and better competitive advantage. Higher or improved productivity means that more is produced with the same expenditure of resources, or even with lesser expenditure on factors of production e.g. land, materials, machine, time or labor. Total-factor productivity (TFP) Total factor productivity is measured by combining the contribution of all the resources used in the production of goods and services and dividing it into the output.It gives an aggregateof how efficient a process has been of producing goods and services, without looking at specific contribution of each factor of production. TFP does not show the interaction between each input and output separately and is thus too broad to be used as a tool for improving specific areas. It requires that total output must be expressed in the same unit of measure and total input must be expressed in the same unit of measure. Productivity growth Productivity ratio is nothing but a number. It becomes useful when the measure is used in comparison with previous measurement or in comparison with a competitor, or comparing with a common and expected standard. In operations, productivity measurement is important because it defines the level of individual, machine, team, department, as well as an entire organization's performance, thereby making it easy to improve. Productivity measurement also relates to competitiveness. If two firms both have the same level of output but one requires less input because of higher productivity, that one will be able to charge a lower price and consequently increase its share of the market. Operations Performance Objectives In order to ensure that resources are allocated appropriately in operations it is necessary to record, monitor and review aspects of operations performance. A key task in this process is the identification of appropriate measures of performance that relate to the internal and external factors that are relevant to organisational competitiveness. The five basic operations performance objectives which allow the organisation to measure its operations performance. The performance objectives are quality, speed, dependability, flexibility and cost. Each one of these objectives will be discussed in terms of how they are measured and their significance to organisational competitiveness. P a g e 10 | 1 FIVE BASIC OPERATIONS PERFORMANCE OBJECTIVES 1. Quality From customer perspective quality characteristics include reliability, performance and aesthetics. From an operations viewpoint quality is related to how closely the product or service meets the specification required by the design, termed the ‘quality of conformance’. The advantages of good quality on competitiveness include: • Increased dependability: less problems due to poor quality mean a more reliable delivery process. • Reduced costs: if things are done right first-time expenditure is saved on scrap and correcting mistakes. • Improved customer service: a consistently high-quality product or ser vice will lead to high customer satisfaction. 2. Speed Speed is the time delay between a customer request for a product or service and the receiving of that product or service. Although the use of a make-to-stock system may reduce the delivery time as seen by the customer, it cannot be used for services and has disadvantages associated with producing for future demand in manufacturing. These include the risk of the products becoming obsolete, inaccurate forecasting of demand leading to stock-out or unwanted stock, the cost of any stock in terms of working capital and the decreased ability to react quickly to changes in customer requirements. Thus the advantage of speed is that it can be used to reduce both costs (by eliminating the costs associated with make-to-stock systems) and delivery time, leading to better customer service. 3. Dependability Dependability refers to consistently meeting a promised delivery time for a product or service to a customer. Thus an increase in delivery speed may not lead to customer satisfaction if it is not produced in a consistent manner. Dependability can be measured by the percentage of customers that receive a product or service within the delivery time promised. Dependability leads to better customer service when the customer can trust that the product or service will be delivered when expected. Dependability can also lead to lower cost, in that progress checking and other activities designed to ensure things happen on time can be reduced within the organisation. Unit 2: Product and Service Design 1. New products and services development Sources for new or redesigned products and services Product and service design It is the detailed specification of a manufactured item’s parts (or detailed specification of components of a service) and their relationship to the whole. Product and service design deals with conversion of ideas into consumable reality. P a g e 11 | 1 Process design Process design is a macroscopic decision-making of an overall process route for converting the raw material into finished goods. These decisions encompass the selection of a process, choice of technology, process flow analysis and layout of the facilities. Hence, the important decisions in process design are to analyze the workflow for converting raw materials into finished products. Both these processes are integral aspects in operations as they define how a product or service will come out to be, thereby affecting demand on the market as well as cost of production. Product and service as well as process design touch every aspect of a business organization, from operations and supply chains to finance, marketing, accounting, and information systems, hence design decisions have far-reaching implications for the organization and its success in the market place. It is important therefore that design decisions should be closely tied to an organisation’s overall strategy and that the processes should be a product of co-ordinated efforts involving the entire business. Sources for new or redesigned products and services Considerations in Product and Service design 1. Customer satisfaction This is the main or primary focus of product and service design. The process aims at satisfying the customer while making a reasonable profit. A business has to make sure that a product or service being offered to the customer is a translation of customer needs, such that the features embedded and components of the product and service will provide functionality as required by the customer. 2. Cost/Profit: This include cost of production, the price at which the customer will be paying for the product or service, as well as the profitability towards the business. 3. Quality: Fit for purpose. 4. Appearance: Attractiveness, ergonometric (ease of use and enhancement of comfortability when in use) and aesthetics. 5. Ease of maintenance/service: Possibility of providing a service at an acceptable cost or profit. Sources for new or redesigned products and services. Reasons for redesigning products and services A business may at one point in time decide to amend product or service design for various reasons. Economic (e.g., low demand, excessive warranty claims, the need to reduce costs). Social and demographic (e.g., changes in customer tastes and population shifts). Political, liability, or legal (e.g., government policy changes, safety issues-A manufacturer is liable for any injuries or damages caused by a faulty product, new laws and regulations). Competition (e.g., new or changed products or services by competitors, new advertising/promotions). Cost or availability (e.g., of raw materials, components, labor). Technological (e.g., in product components, processes). Sources for new or redesigned products and services. P a g e 12 | 1 Sources of product and services design There are internal and external sources of design ideas of products and services. Internal/Primary sources: 1. Employees Employees are the ones who have the expertise of producing the products and services (those in production), as well as the ones who meet the customers (marketing and sales). It is imperative therefore that employees have to be motivated and encouraged to be innovative in order to achieve business winning product and services designs. 2. Sources for new or redesigned products and services Creative thinking techniques that encourage employee innovation 3. Brain storming This is a technique of generating a large number of ideas from a group of people in a short time. Usually, a group of 8 to 12 people take a problem and come up with ideas randomly in a free atmosphere. Judgement and analysis of the ideas is suspended until all ideas are generated. In this technique, wild and unorthodox ideas are encouraged. Ideas are displayed on sheets of paper and are produced very quickly, such that a one hour session may even produce over 200 ideas. The disadvantage of this technique is that all ideas generated have to be evaluated including those that are obviously foolish and irrelevant. Sources for new or redesigned products and services 4. Forced relationships This technique takes objects or ideas and asks the question, “in how many ways can these be combined to give a new object or idea?” This brings about a hybrid idea or object which did not exist before. 5. Attribute listing This technique lists down the main attributes of an idea or object, and examines each one to see how it can be changed. Mostly, it is applied on tangible rather than intangible things. Each attribute is questioned and changes on improvements are suggested. Sources for new or redesigned products and services. It has to be noted that no matter which technique can be chosen in creative thinking in the action planning stage, the following guidelines have to be applied: 1. Suspended judgement: Rule out premature criticism of any idea. 2. Free-wheel: The wilder or unorthodox the ideas, the better results. 3. Quantity: The more ideas, the better. 4. Cross-fertilize: Combine and improve on the ideas of others. Sources for new or redesigned products and services. 5. Marketing department-The marketing department generates enormous information about customers that can productively be used in designing products and services. Marketing is typically aware of problems with products or services (those by the business as well as by competitors) on the market. They assess current needs of customers, buying patterns, and familiarity with demographics. Importantly also, P a g e 13 | 1 6. 7. 8. 9. marketing can help craft a vision of what customers are likely to want in the future. All this information can be a source of product and service design. Customers- They are the ones who directly use the products and services hence have a true experience of performance. A business should therefore devise ways of extracting information and use it to incorporate and better the design of its products and services. Customers may submit suggestions for new products or improvements, or they may be queried through the use of surveysor focus groups. Customer complaints can also provide valuable insight into areas that need improvement hence they should be regarded as an input to design ideas. Similarly, product failures and warranty claims indicate where improvements are needed. Competitors- Competitor products and services can be a very important source of designs. A business can develop a new design or improve on an existing design by studying a competitor's products or services and how the competitor operates (pricing policies, return policies, warranties, location strategies, etc.). A business can use reverse engineering in order to understand a competitor’s product or service’s components. Reverse engineering involves dismantling and inspecting a competitor's product for the purpose of finding ways to improve their own product or service. Suppliers- Because of improved supply chain practices, suppliers have a huge influence on businesses as they are regarded as partners. They are the ones who supply the business with materials and components, hence they are much knowledgeable on improved raw materials and components which ultimately have an impact on product or service design. Businesses should therefore strive to utilise the expertise that suppliers have in order to improve product and service design. Businesses can use the Japanese concept of kyoryokukai, that encourages suppliers that are important to a business to form an association that eventually becomes a platform for improvement suggestions. Research and Development Apart from the marketing department, other organizations have Research and Development department responsible for organized efforts to increase scientific knowledge or product innovation, usually without near-term expectations of commercial applications and benefits. The cost of R&D could be high but the benefits are enormous. R&D can achieve patents with possibilities of earning royalties due to licensing of use of the patents. Also, being the first to introduce a product or service achieves more profits due to a temporary monopoly on the market as other producers will take time to catch up. Phases in product/service development process 1. Idea generation Sources of ideas have to be reliable and comprehensive. This phase result in conceptualization of how a product or service should be like. 2. Product/Service screening This is a feasibility multi-disciplinary phase hence all departments in a business have to be involved. The screening is done based on three dimensions; market analysis, economic analysis and technical analysis. Sources for new or redesigned products and services P a g e 14 | 1 3. Market analysis This consist of evaluating the product concept with potential customers through interviews, focus groups, and other data collection methods. The purpose of market analysis is to ascertain whether the product is viable, and to be sure whether sufficient demand exists. In market analysis, top managers at a strategic level have to project the life cycle of the product and draw beforehand strategies at each phase of the cycle. The product cycle describes the product sales volume over time. Ordinarily, in the early introduction stage, production costs are higher due to low production. Also, changes in design must be anticipated. A proper strategy could be to charge a premium price, as there would be no competitors if the product is new, and that the product might be attracting innovative and fashionable customers. At the growth stage, it is anticipated that production costs will be reducing due to high production and perfection of production methods. There is also a high chance of competitors as new entrants. It is therefore important to increase promotion sin order to firmly establish the product on the market. At the mature stage, competition is usually high, thereby requiring more advertising to keep customers interested, product rebranding, among other strategies, in order to achieve differentiation. Sources for new or redesigned products and services 4. Economic analysis This aims at ascertaining that rolling out the product will make economic sense that total cost of production will eventually be recouped by breaking even (selling costs = production costs) and also have a profit margin. In order to carry out this analysis, there is need to have accurate estimates of demand derived from statistical forecasts of industry sales and estimates of market share in which the product will be competing. Techniques of conducting this analysis could be: Cost/benefit analysis, Decision theory, Net Present Value, Internal Rate of Return. Sources for new or redesigned products and services. 5. Technical analysis This consists of determining whether the business has the capability and capacity to manufacture the product as required in terms of quality and volume. This also includes whether the business has the required skills and that sources of raw materials are available. 6. Preliminary Design Product concepts that pass the feasibility stage enter this stage. This stage involves mapping how components that will make up the product or service will be arranges in coherence. This can be done by use of drawing sketches. 7. Final Design This final stage involves the use of a prototype for the purpose of testing the outcome of the preliminary design until a final design is chosen. Computer Aided Design (CAD) can be used at this stage. The advantage of using CAD is that the process is P a g e 15 | 1 made fast, simple and cheaper. Also, because it is computer aided, it is easy to document the best process (steps) in coming up with the prototype. 2. Legal, ethical and environmental issues Legal, ethical and environmental issues Legal issues As stated earlier, a manufacturer is liable for any injuries or suffering due to the customer’s use or consumption of their product or service. Legal suits and potential suits leads to increased legal and insurance costs, expensive settlements with injured parties, and costly product recalls. It is extremely important to design products that are reasonably free of hazards. In case hazards do exist, it is necessary to install safety guards or other devices for reducing accident potential, and to provide adequate warning notices of risks as well as what to do in the event of injuries. Consumer groups, business firms, and various government agencies often work together to develop industrywide standards that help avoid some of the hazards. In designing and manufacturing of products, this important factor has to be considered, such that all the legal obligations that regulators set regarding quality and standards of a product has to be met. This reduces claims of damages that have both financial and reputational effects on the business. Ethical issues In most of the times, manufacturers tend to ignore universal ethics in manufacturing and service provision due to the reason that mostly, they don’t attract legal penalties. Most of the unethical issues rampant in the manufacturing industry are exploitation of labour by offering low wages to vulnerable groups such as women, children, and displaced people. Tax avoidance and evasion is also a common unethical issue that manufacturers are susceptible. Acting unethical reduces brand image as well as business reputation, thereby leading to lower demand and sales. Legal, ethical and environmental issues. Environmental issues Manufacturers have to always avoid producing products and services that have the potential to harm the environment. Ways on how manufacturers can protect the environment: 1. Make the product reusable for its intended purpose by reselling (if the products are unsold merchandise), repairing, refurbishing or remanufacturing. 2. Cannibalization, the process of retrieving reusable parts from old or broken products. 3. Recycling so that parts of products are reused for different purposes. 4. Disposing of the products by putting them to the landfill, incineration or composting. Considering environment issues have benefits not only to the environment, but P a g e 16 | 1 importantly to the organization. It boosts corporate image as well as reducing manufacturing costs through reuse of materials. 3. Designing for manufacturing, designing for services Designing for manufacturing, designing for services Before products can flow into a market, someone must design and invest in the facilities and organisation to produce them. Capacity planning for manufacturing and service systems are different. Both must be designed with capacity limitations in mind. The approaches for longterm and short-term capacity planning will help the managers to make best use of resources. MANUFACTURING AND SERVICE SYSTEMS Manufacturing and service systems are arrangements of facilities, equipment, and people to produce goods and services under controlled conditions. Manufacturing systems produce standardized products in large volumes. This plant and machinery have a finite capacity and contribute fixed costs that must be borne by the products produced. Variable costs are added as labour is employed to combine or process the raw materials and other components. Value addition will takes place during the production process for the product. The cost of output relative to the cost of input can be measured, as the actual cost is known i.e. productivity is measurable quantity. Service systems present more uncertainty with respect to both capacity and costs. Services areproduced and consumed in the presence of the customer and there is little or no opportunity to store value, as in a finished goods inventory. As a result capacity of service systems like hospitals, restaurants and many other services must be sufficiently flexible to accommodate a highly variable demand. In addition, many services such as legal and medical involves professional or intellectual services judgments that are not easily standardized. This makes more difficult to accumulate costs and measure the productivity of the services. There are fundamental differences between services and products, which have to be taken into consideration when designing. Differences: Products are generally tangible; services are generally intangible. Consequently, service design often focuses more on intangible factors (e.g., peace of mind, ambiance or atmosphere) than does product design. In many instances, services are created and delivered at the same time (e.g. driving, laundry). In such instances there is less latitude in finding and correcting errors before the customer discovers them. Consequently, training, process design, and customer relations are particularly important. Designing for manufacturing, designing for services. Services cannot be inventoried or stored. This poses restrictions on flexibility and makes capacity design very important such that a business has to have extra capacity to cater for eventuality of excess demand. P a g e 17 | 1 Location is often important to service design, with convenience as a major factor. Hence, design of services and choice of location are often closely linked. Service design general guidelines: Have a single, unifying theme, such as convenience or speed. This will help personnel to work together as they will have a uniform focus when offering the service. Always be certain that your system has the capability to handle any expected variability in service requirements. Include design features and checks to ensure that services rendered will be reliable and will provide consistently high quality. For example, if the focus is on time, set measurable parameters on how long does it take to provide the service? Design the system to be user-friendly. This is especially true for self-service systems, such that it is easy for customers to operate by themselves. SECTION B FORECASTING AND PROCESS IN PRODUCTION AND OPERATIONS MANAGEMENT Unit 3: Forecasting and Capacity Planning 1. Forecasting Forecasts are essential for the smooth operations of business organizations. They provide information that can assist managers in guiding future activities toward organizational goals. FORECASTING OBJECTIVES AND USES Forecasts are estimates of the occurrence, timing, or magnitude of uncertain future events. Forecasts are essential for the smooth operations of business organizations. They provide information that can assist managers in guiding future activities toward organizational goals. Operations managers are primarily concerned with forecasts of demand—which are often made by marketing. However, managers also use forecasts to estimate raw material prices, plan for appropriate levels of personnel, help decide how much inventory to carry, and a host of other activities. This results in better use of capacity, more responsive service to customers, and improved profitability. FORECASTING DECISION VARIABLES Forecasting activities are a function of (1) the type of forecast (e.g., demand, technological), (2) the time horizon (short, medium, or long range), (3) the database available, and (4) the methodology employed (qualitative or quantitative). Forecasts of demand are based primarily on non-random trends and relationships, with an allowance for random components. Forecasts for groups of products tend to be more accurate than those for single products, and short-term forecasts are more accurate than long-term forecasts (greater than five years). Quantification also enhances the objectivity and precision of a forecast. 2. Forecasts methods a. Judgment and opinion (Delphi) b. Time series data FORECASTING METHODS P a g e 18 | 1 There are numerous methods to forecasting depending on the need of the decision-maker. These can be categorized in two ways: 1. Opinion and Judgmental Methods or Qualitative Methods. 2. Time Series or Quantitative Forecasting Methods. Opinion and Judgmental Methods Some opinion and judgment forecasts are largely intuitive, whereas others integrate data and perhaps even mathematical or statistical techniques. Judgmental forecasts often consist of (1) forecasts by individual sales people, (2) Forecasts by division or product-line managers, and (3) combined estimates of the two. Historical analogy relies on comparisons; Delphi relies on the best method from a group of forecasts. All these methods can incorporate experiences and personal insights. However, results may differ from one individual to the next and they are not all amenable to analysis. So there may be little basis for improvement over time. Time Series Methods A time series is a set of observations of a variable at regular intervals over time. In decomposition analysis, the components of a time series are generally classified as trend T, cyclical C, seasonal S , and random or irregular R. (Note: Autocorrelation effects are sometimes included as an additional factor.) Time series are tabulated or graphed to show the nature of the time dependence. The forecast value (Ye) is commonly expressed as a multiplicative or additive function of its components; examples here will be based upon the commonly used multiplicative model. Y= T. S. C. R multiplicative model Y= T + S + C + R additive model where T is Trend, S is Seasonal, C is Cyclical, and R is Random components of a series. Trend is a gradual long-term directional movement in the data (growth or decline). Seasonal effects are similar variations occurring during corresponding periods, e.g., December retail sales. Seasonal can be quarterly, monthly, weekly, daily, or even hourly indexes. Cyclical factors are the long-term swings about the trend line. They are often associated with business cycles and may extend out to several years in length. Random component are sporadic (unpredictable) effects due to chance and unusual occurrences. They are the residual after the trend, cyclical, and seasonal variations are removed. 3. Choosing forecasting technique and using forecast information Choosing forecasting technique and using forecast information Forecasting is used in almost every area of business today. It is an essential tool for managing an organization of any size. In business meetings and conferences executives often hear about forecasts for the next quarter or year from their company CEOs or directors. Data analysts spend a considerable amount of time to make a forecast based on the historical data. Prediction of sales volume, stock prices, demand, and trends is the backbone of decisionP a g e 19 | 1 making in most of the organizations. It is a business necessity which pays off if analyzed and optimized effectively. Data collected over time is complex in nature and include components related to seasonality, irregularity, and cyclicality. As a result, it is important to select the right forecasting method to handle the increasing variety and complexity of data to forecast correctly. However, before selecting the forecasting model, a forecaster needs to have answers to the following questions. What is the purpose of the forecast. Are there any relationships between variables? Is your historical data sufficient to make forecasts? These questions will help forecasters direct themselves to the right forecasting model and build an accurate set of growth projections for their businesses. What are forecasting models? In statistics, there are two types of methods by which a business forecast can be made. These are categorized broadly into qualitative and quantitative models. Qualitative Models Qualitative models are used to make short-term forecasts. These models depend on the information available in different sources which have been quoted by thought leaders. The qualitative model is used when the availability of data is low. These models are frequently used in predicting numbers based on: Market Research: It incorporates procedures for testing hypothesis from the available numbers for real markets. Delphi Method: This method involves taking opinions from experts through questionnaires and then using it into a forecast. The objective of qualitative models is to forecast numbers based on logical and unbiased opinions. A lot of organizations use a combination of these methods to forecast sales and revenues. However, there are a few limitations to this method. The first one is that it depends solely on opinions which may be wrong. Secondly, the accuracy of this method is not high and mostly depends on human judgements. Quantitative Models Quantitative models are used when the data is available for several years and we can build relationship among variables. Further, quantitative models can be categorized as: Regression Model: The model uses the least square technique to form an equation based on a dependent and one or more independent variables. P a g e 20 | 1 Econometric Model: The econometric model tests the relationships between variables such as GDP, inflation, and exchange rates over time. The model forms interdependent regression equations. Time-Series Model: The objective of a time-series model is to discover patterns in historical data and extrapolate it into forecasts. It uses exponential smoothing, ARIMA,and trend analysis to forecast data for the next time period. Leading Indicator: This model uses the relationship between different macroeconomic activities to identify leading indicators and estimate the performance of the lagging indicators. Both qualitative and quantitative models provide decision-makers with numbers which are useful in production planning, financing, and business optimization. A successful forecaster removes irregularity and non-stationary components in data. However, there are a few factors which might lead to wrong forecasts. This happens when: 1) The data is inaccurate. 2) The data is produced with a lag and requires revision. 3) The data is a proxy for the decision-making criteria. Forecasting plays a pivotal role in long-term business planning. An accurate analysis of trends is vital in managing the growth of organization, and ultimately in ensuring its success. However, necessary steps should be taken to review the forecasts before making the blueprint of sales and marketing plans. A right forecast will make your business more profitable and pave the way to a successful organization. In a nutshell, forecasting is like a magical crystal ball that can see the future when asked the rights questions and used the right techniques for all your business problems. 4. Importance of capacity decisions IMPORTANCE OF CAPACITY DECISIONS 1. Capacity decisions have a real impact on the ability of the organization to meet future demands for products and services; capacity essentially limits the rate of output possible. Having capacity to satisfy demand can allow a company to take advantage of tremendous opportunities. 2. Capacity decisions affect operating costs. Ideally, capacity and demand requirements will be matched, which will tend to minimize operating costs. In practice, this is not always achieved because actual demand either differs from expected demand or tends to vary (e.g., cyclically). In such cases, a decision might be made to attempt to balance the costs of over and under capacity. 3. Capacity is usually a major determinant of initial cost. Typically, the greater the capacity of a productive unit, the greater its cost. This does not necessarily imply a one for-one relationship; larger units tend to cost proportionately less than smaller units. 4. Capacity decisions often involve long-term commitment of resources and the fact that, once they are implemented, it may be difficult or impossible to modify those decisions without incurring major costs. 5. Capacity decisions can affect competitiveness. If a firm has excess capacity, or can quickly add capacity, that fact may serve as a barrier to entry by other firms. Then too, capacity can affect delivery speed, which can be a competitive advantage. P a g e 21 | 1 6. Capacity affects the ease of management; having appropriate capacity makes management easier than when capacity is mismatched. Capacity Planning A definition of capacity should take into account both the volume and the time over which capacity is available. Thus capacity can be taken as a measure of an organisation’s ability to provide customers with services or goods in the amount requested at the time requested. Capacity decisions should be taken by firstly identifying capacity requirements and then evaluating the alternative capacity plans generated. Identifying Capacity Requirements This stage consists of both estimating future customer demand but also determining current capacity levels to meet that demand. Measuring Demand In a capacity planning context the business planning process is driven by two elements; the company strategy and forecasts of demand for the product/service the organisation is offering to the market. Demand forecasts will usually be developed by the marketing department and their accuracy will form an important element in the success of any capacity management plans implemented by operations. The demand forecast should express demand requirements in terms of the capacity constraints applicable to the organisation. This could be machine hours or worker hours as appropriate. The demand forecast should permit the operations manager to ensure that enough capacity is available to meet demand at a particular point in time, whilst minimising the cost of employing too much capacity for demand needs. The amount of capacity supplied should take into account the negative effects of losing an order due to too little capacity and the increase in costs on the competitiveness of the product in its market. Organisations must develop forecasts of the level of demand they should be prepared to meet. The forecast provides a basis for co-ordination of plans for activities in various parts of the organisation. For example personnel employ the right amount of people, purchasing order the right amount of material and finance can estimate the capital required for the business. Forecasts can either be developed through a qualitative approach or a quantitative approach. Measuring Capacity When measuring capacity it must be considered that capacity is not fixed but is a variable that is dependent on a number of factors such as the product mix processed by the operation and machine setup requirements. When the product mix can change then it can be more useful to measure capacity in terms of input measures, which provides some indication of the potential output. Also for planning purposes when demand is stated in output terms it is necessary to convert input measures to an estimated output measure. For example in hospitals which undertake a range of activities, capacity is often measured in terms of beds available (an input) measure. An output measure such as number of patients treated per week will be highly dependent on the mix of activities the hospital performs. The theoretical design capacity of an operation is rarely met due to such factors as maintenance and machine setup time between different products so the effective capacity is a more realistic measure. However this will also be above the level of capacity which is available due to unplanned occurrences such as a machine breakdown. Evaluating Capacity Plans P a g e 22 | 1 The organization’s ability to reconcile capacity with demand will be dependent on the amount of flexibility it possesses. Flexible facilities allow organisations to adapt to changing customer needs in terms of product range and varying demand and to cope with capacity shortfalls due to equipment breakdown or component failure. The amount of flexibility should be determined in the context of the organizations’ competitive strategy. Methods for reconciling capacity and demand can be classified into three ‘pure’ strategies of level capacity, chase demand and demand management although in practice a mix of these three strategies will be implemented. Level Capacity This approach fixes capacity at a constant level throughout the planning period regardless of fluctuations in forecast demand. This means production is set at a fixed rate, usually to meet average demand and inventory is used to absorb variations in demand. During periods of low demand any overproduction can be transferred to finished goods inventory in anticipation of sales at a later time period. The disadvantage of this strategy is the cost of holding inventory and the cost of perishable items that may have to be discarded. To avoid producing obsolete items firms will try to create inventory for products which are relatively certain to be sold. This strategy has limited value for perishable goods. For a service organisation output cannot be stored as inventory so a level capacity plan involves running at a uniformly high level of capacity. The drawback of this approach is the cost of maintaining this high level of capacity although it could be relevant when the cost of lost sales is particularly high, for example in a high value retail outlet such as a luxury car outlet where every sale is very profitable. Chase Demand This strategy seeks to change production capacity to match the demand pattern over time. Capacity can be altered by various policies such as changing the amount of part-time staff, changing the amount of staff availability through overtime working, changing equipment levels and subcontracting. The chase demand strategy is costly in terms of the costs of changing staffing levels and overtime payments. The costs may be particularly high in industries in which skills are scarce. Disadvantages of subcontracting include reduced profit margin lost to the subcontractor, loss of control, potentially longer lead times and the risk that the subcontractor may decide to enter the same market. For these reasons a pure chase demand strategy is more usually adopted by service operations which cannot store their output and so make a level capacity plan less feasible. 23 Demand Management While the level capacity and chase demand strategies aim to adjust capacity to match demand, the demand management strategy attempts to adjust demand to meet available capacity. There are many ways this can be done, but most will involve altering the marketing mix and will require co-ordination with the marketing function. Demand Management strategies include: Varying the Price - During periods of low demand price discounts can be used to stimulate the demand level. Conversely when demand is higher than the capacity limit, price could be increased.Provide increased marketing effort to product lines with excess capacity. Use advertising to increase sales during low demand periods. Use the existing process to develop alternative product during low demand periods. Offer instant delivery of product during low demand periods. Use an appointment system to level out demand. 5. Measuring and determining capacity requirements P a g e 23 | 1 Determining capacity requirements Capacity requirements can be evaluated from two perspectives—long-term capacity strategies and short-term capacity strategies. 1. Long-term capacity strategies: Long-term capacity requirements are more difficult to determine because the future demand and technology are uncertain. Forecasting for five or ten years into the future is more risky and difficult. Even sometimes company’s today’s products may not be existing in the future. Long-range capacity requirements are dependent on marketing plans, product development and life-cycle of the product. Long-term capacity planning is concerned with accommodating major changes that affect overall level of the output in long-term. Marketing environmental assessment and implementing the long-term capacity plans in a systematic manner are the major responsibilities of management. Following parameters will affect long-range capacity decisions. Multiple products: Company’s produce more than one product using the same facilitiesin order to increase the profit. The manufacturing of multiple products will reduce the risk of failure. Having more than on product helps the capacity planners to do a better job. Because products are in different stages of their life cycles, it is easy to schedule them to get maximum capacity utilisation. Phasing in capacity: In high technology industries, and in industries where technology developments are very fast, the rate of obsolescence is high. The products should be brought into the market quickly. The time to construct the facilities will be long and there is no much time, as the products should be introduced into the market quickly. Here the solution is phase in capacity on modular basis. Some commitment is made for building funds and men towards facilities over a period of 3-5 years. This is an effective way of capitalizing on technological breakthrough. Phasing out capacity: The outdated manufacturing facilities cause excessive plant closures and down time. The impact of closures is not limited to only fixed costs of plant and machinery. Thus, the phasing out here is done with humanistic way without affecting the community. The phasing out options makes alternative arrangements for men like shifting them to other jobs or to other locations, compensating the employees, etc. 2. Short-term capacity strategies: Managers often use forecasts of product demand to estimate the short-term workload the facility must handle. Managers looking ahead up to 12 months, anticipate output requirements for different products, and services. Managers then compare requirements with existing capacity and then take decisions as to when the capacity adjustments are needed. For short-term periods of up to one year, fundamental capacity is fixed. Major facilities will not be changed. Many short-term adjustments for increasing or decreasing capacity are possible. The adjustments to be required depend upon the conversion process like whether it is capital intensive or labour intensive or whether product can be stored as inventory. Capital-intensive processes depend on physical facilities, plant and equipment. Short-term capacity can be modified by operating these facilities more or less intensively than normal. In labour intensive processes short-term capacity can be changed by laying off or hiring people or by giving overtime to workers. The strategies for changing capacity also depend upon how long the product can be stored as inventory. The short-term capacity strategies are: 1. Inventories: Stock finished goods during slack periods to meet the demand during peak period. 2. Backlog: During peak periods, the willing customers are requested to wait and their orders are fulfilled after a peak demand period. P a g e 24 | 1 3. Employment level (hiring or firing): Hire additional employees during peak demand period and lay-off employees as demand decreases. 4. Employee training: Develop multi skilled employees through training so that they can be rotated among different jobs. The multi skilling helps as an alternative to hiring employees. 5. Subcontracting: During peak periods, hire the capacity of other firms temporarily to make the component parts or products. 6. Process design: Change job contents by redesigning the job. Unit 4: Process Selection and Facility Layout 1. Basic process strategies Basic Process Strategies A process (or transformation) strategy is an organization’s approach to transforming resources into goods and services. The objective of a process strategy is to build a production process that meets customer requirements and product specification within cost and other managerial constraints. The process selected will have a long term effect on efficiency and flexibility of production as well as on cost and quality of the goods produced. Therefore the limitations of a process strategy are at the time of the process decision. A process or transformation strategy is an organization's approach to transform resources into goods and services. These goods or services are organized around a specific activity or process. Every organization will have one of the four process strategies: a. Process focus in a factory; these processes might be departments devoted to welding, grinding, and painting. In an office the processes might be accounts payable, sales, and payroll. In a restaurant, they might be bar, grill, and bakery. The process focuses on low volume, high variety products are also called job shop. These facilities are process focus in terms of equipment, layout, and supervision. b. Repetitive focus; falls between the product and process focus. The repetitive process is a product-oriented production process that uses modules. Modules are parts or components of a product previously manufactured or prepared, often in a continuous process. Fast-food firms are an example of repetitive process using modules. c. Product focus, are high volume, low variety processes; also called continuous processes. Products such as light bulbs, rolls of paper, beer, and bolts are examples of product process. This type of facility requires a high fixed cost, but low costs. The reward is high facility utilization. d. Mass customizations focus; is rapid, low-cost production that caters to constantly changing unique customer desires. This process is not only about variety; it is about making precisely what the customer wants when the customer wants it economically. Achieving mass customization is a challenge that requires sophisticated operational capabilities. In understanding Process strategy there are three principles that are particularly important: P a g e 25 | 1 The key to successful process decisions is to make choices that fit the situation. They should not work at cross-purposes, with one process optimized at the expense of other processes. A more effective process is one that matches key process characteristics and has a close strategic fit. Individual processes are the building blocks that eventually create the firm’s whole supply chain. Management must pay close attention to all interfaces between processes in the supply chain, whether they are performed internally or externally. It can be utilized to guide a variety of process decisions, operations strategy, and your business’ ability to obtain the resources necessary to support them. A process involves the use of an organization’s resources to provide something of value. Major process decisions include: Process Structure determines how processes are designed relative to the kinds of resources needed, how resources are partitioned between them, and their key characteristics. Customer Involvement refers to the ways in which customers become part of the process and the extent of their participation. It is Manager’s job to assess whether the advantages outweigh disadvantages, judging them in terms of the competitive priorities and customer satisfaction. Customer involvement is not always the best option as there are disadvantages commonly associated with it. For example, allowing customers to play an active role in a service process can be disruptive thereby making the process less efficient. Quality measurement also becomes more difficult to manage. Additionally, customer involvement in processes can also mean greater expenses for your business as you will require employees with greater interpersonal skills and possibly consider revising your facility layout. However, despite these possible disadvantages, the advantages of a more customer-focused Customer involvement process might increase the net value to your customer. Some customers seek active participation in and control over the service process, particularly if they will enjoy savings in both price and time. More customer involvement can mean better quality, faster delivery, greater flexibility, and even lower cost. Resource flexibility is the ease with which employees and equipment can handle a wide variety of products, output levels, duties, and functions. We consider resource flexibility mainly at two levels: Workforce One of the decisions and operations manager has to make is whether or not to have a flexible workforce, that is, employees that are capable of doing many tasks. The type of workforce you require is also dependent on the need for volume flexibility. For example, when conditions allow for a smooth, stead rate of output, the likely choice is a permanent workforce that expects regular full-time employment. P a g e 26 | 1 Alternatively, if the process is subject to hourly, daily, or seasonal peaks and valleys in demand, the use of part-time or temporary employees to supplement a smaller core of fulltime employees may be the best solution Equipment When a firm’s product or service has a short life cycle and a high degree of customization, low production volumes mean that a firm should select flexible, inexpensive, general-purpose equipment. When volumes are low, the low fixed cost more than offsets the higher variable unit cost associated with this type of equipment. Conversely, specialized, higher-cost equipment is the best choice when volumes are high and customization is low. Its advantage is low variable unit cost Capital intensity is the mix of equipment and human skills in a process. It is calculated: total assets of a company/sales of the company. A higher capital intensity ratio for a company means that the company needs more assets than a company with lower ratio to generate equal amount of sales. A high capital intensity ratio may due to lower utilization of the company’s assets or it may be because the company’s business is more capital intensive and less labor intensive (for example, because it is automated). However, for companies in the same industry and following similar business model and production processes, the company with lower capital intensity is better because it generates more revenue using less assets. 2. Facility layout planning FACILITY LAYOUT PLANNING Facility layout refers to the arrangement of machines, departments, workstations, storage areas, aisles, and common areas within an existing or proposed facility. Layouts have farreaching implications for the quality, productivity, and competitiveness of a firm. Layout decisions significantly affect how efficiently workers can do their jobs, how fast goods can be produced, how difficult it is to automate a system, and how responsive the system can be to changes in product or service design, product mix, and demand volume. The basic objective of the layout decision is to ensure a smooth flow of work, material, people, and information through the system. Effective layouts also: • Minimize material handling costs; • Utilize space efficiently; • Utilize labor efficiently; • Eliminate bottlenecks; • Facilitate communication and interaction between workers, between workers and their supervisors, or between workers and customers; • Reduce manufacturing cycle time and customer service time; • Eliminate wasted or redundant movement; • Facilitate the entry, exit, and placement of material, products, and people; • Incorporate safety and security measures; • Promote product and service quality; • Encourage proper maintenance activities; • Provide a visual control of operations or activities; • Provide flexibility to adapt to changing conditions. P a g e 27 | 1 3. Types of facility layout Special cases of process layout Basic Layouts There are three basic types of layouts: process, product, and fixed-position; and three hybrid layouts: cellular layouts, flexible manufacturing systems, and mixed-model assembly lines. We discuss basic layouts in this section and hybrid layouts later in the chapter. Process Layouts Process layouts, also known as functional layouts, group similar activities together in departments or work centers according to the process or function they perform. For example, in a machine shop, all drills would be located in one work center, lathes in another work center, and milling machines in still another work center. In a department store, women's clothes, men's clothes, children's clothes, cosmetics, and shoes are located in separate departments. A process layout is characteristic of intermittent operations, service shops, job shops, or batch production, which serve different customers with different needs. The volume of each customer's order is low, and the sequence of operations required to complete a customer's order can vary considerably. The equipment in a process layout is general purpose, and the workers are skilled at operating the equipment in their particular department. The advantage of this layout is flexibility. The disadvantage is inefficiency. Jobs or customers do not flow through the system in an orderly manner, backtracking is common, movement from department to department can take a considerable amount of time, and queues tend to develop. In addition, each new arrival may require that an operation be set up differently for its particular processing requirements. Although workers can operate a number of machines or perform a number of different tasks in a single department, their workload often fluctuates--from queues of jobs or customerswaiting to be processed to idle time between jobs or customers. Figure below Material storage and movement are directly affected by the type of layout. Storage space in a process layout is large to accommodate the large amount of in-process inventory. The factory may look like a warehouse, with work centers strewn between P a g e 28 | 1 storage aisles. In-process inventory is high because material moves from work center to work center in batches waiting to be processed. Finished goods inventory, on the other hand, is low because the goods are being made for a particular customer and are shipped out to that customer upon completion. Process layouts in manufacturing firms require flexible material handling equipment (such as forklifts) that can follow multiple paths, move in any direction, and carry large loads of in process goods. A forklift moving pallets of material from work center to work center needs wide aisles to accommodate heavy loads and two-way movement. Scheduling of forklifts is typically controlled by radio dispatch and varies from day to day and hour to hour. Routes have to be determined and priorities given to different loads competing for pickup. Process layouts in service firms require large aisles for customers to move back and forth and ample display space to accommodate different customer preferences. The major layout concern for a process layout is where to locate the departments or machine centers in relation to each other. Although each job or customer potentially has a different route through the facility, some paths will be more common than others. Past information on customer orders and projections of customer orders can be used to develop patterns of flow through the shop. Product Layouts Product layouts, better known as assembly lines, arrange activities in a line according to the sequence of operations that need to be performed to assemble a particular product. Each product or has its own "line" specifically designed to meet its requirements. The flow of work is orderly and efficient, moving from one workstation to another down the assembly line until a finished product comes off the end of the line. Since the line is set up for one type of product or service, special machines can be purchased to match a product's specific processing requirements. Product layouts are suitable for mass production or repetitive operations in which demand is stable and volume is high. The product or service is a standard one made for a general market, not for a particular customer. Because of the high level of demand, product layouts are more automated than process layouts, and the role of the worker is different. Workers perform narrowly defined assembly tasks that do not demand as high a wage rate as those of the more versatile workers in a process layout. The advantage of the product layout is its efficiency and ease of use. The disadvantage is its inflexibility. Significant changes in product design may require that a new assembly line be built and new equipment be purchased. This is what happened to U.S. automakers when demand shifted to smaller cars. The factories that could efficiently produce six-cylinder engines could not be adapted to produce fourcylinder engines. A similar inflexibility occurs when demand volume slows. The fixed cost of a product layout (mostly for equipment) allocated over fewer units can send the price of a product soaring. The major concern in a product layout is balancing the assembly line so that no one workstation becomes a bottleneck and holds up the flow of work through the line. Figure below shows the product flow in a product layout. P a g e 29 | 1 A product layout needs material moved in one direction along the assembly line and always in the same pattern. Conveyors are the most common material handling equipment for product layouts. Conveyors can be paced (automatically set to control the speed of work) or unpaced (stopped and started by the workers according to their pace). Assembly work can be performed online (i.e., on the conveyor) or offline (at a workstation serviced by the conveyor). Aisles are narrow because material is moved only one way, it is not moved very far, and the conveyor is an integral part of the assembly process, usually with workstations on either side. Scheduling of the conveyors, once they are installed, is simple--the only variable is how fast they should operate. Storage space along an assembly line is quite small because in-process inventory is consumed in the assembly of the product as it moves down the assembly line. Finished goods, however, may require a separate warehouse for storage before they are shipped to dealers or stores. Fixed-Position Layouts Fixed-position layouts are typical of projects in which the product produced is too fragile, bulky, or heavy to move. Ships, houses, and aircraft are examples. In this layout, the product remains stationary for the entire manufacturing cycle. Equipment, workers, materials, and other resources are brought to the production site. Equipment utilization is low because it is often less costly to leave equipment idle at a location where it will be needed again in a few days, than to move it back and forth. Frequently, the equipment is leased or subcontracted, because it is used for limited periods of time. The workers called to the work site are highly skilled at performing the special tasks they are requested to do. For instance, pipefitters may be needed at one stage of production, and electricians or plumbers at another. The wage rate for these workers is much higher than minimum wage. Thus, if we were to look at the cost breakdown for fixed-position layouts, the fixed cost would be relatively low (equipment may not be owned by the company), whereas the variable costs would be high (due to high labor rates and the cost of leasing and moving equipment). Because the fixed-position layout is specialized, we concentrate on the product and process layouts and their variations for the remainder of this chapter. In the sections that follow, we examine some quantitative approaches for designing product and process layouts. Unit 5: Location Planning and Analysis 1. The nature of location decision P a g e 30 | 1 Location decisions represent an integral part of the strategic planning process of every organization. Although it might appear that location decisions are one-time problems pertaining to new organizations, existing organizations often have a bigger stake in these kinds of decisions than new organizations. Location decisions are critical at several levels. At the national level, retail analysts screen and select metropolitan and regional market for new store entry. The location of the non-manufacturing operation helps determine how conveniently customers can conduct business with the company. Importance of location decision Location decisions are closely tied to an organization’s strategy. Location choices can impact capacity and flexibility. Transportation costs: high costs can occur due to poor infrastructure or having to ship over great distance. Security costs: increased security risks and theft can increase cost, and slow shipment to other countries. Before getting into location decisions, it will be helpful for you to understand the terms related to plant location decisions. Plant means any set-up, for the purpose of business, which is engaged in any kind of production operation and yields semi-finished or finished goods as end results. Location, on the other hand, means any place or region of any set-up or concern in which the set-up or concern is situated. Thus plant location decisions are those, made by managers, which are aimed to the selection of a location for the settlement of any intended plant of the concern business. Plant Location decisions are usually based on factors as labour supply condition, raw materials supply condition, distance with the market place, and a lot of others of this type. The location of these facilities can involve a long term commitment of resources, so known risks and benefits should be considered carefully. 2. General procedure for making location decisions Procedure for Making Location Decisions As with capacity planning, managers need to follow a three-step procedure when making facility location decisions. These steps are as follows: Step 1 Identify Dominant Location Factors. In this step managers identify the location factors that are dominant for the business. This requires managerial judgment and knowledge. Step 2 Develop Location Alternatives. Once managers know what factors are dominant, they can identify location alternatives that satisfy the selected factors. Step 3 Evaluate Location Alternatives. After a set of location alternatives have been identified, managers evaluate them and make a final selection. This is not easy because one location may be preferred based on one set of factors, whereas another may be better based on a second set of factors. P a g e 31 | 1 Procedures for Evaluating Location Alternatives A number of procedures can help in evaluating location alternatives. These are decision support tools that help structure the decision-making process. Some of them help with qualitative factors that are subjective, such as quality of life. Others help with quantitative factors that can be measured, such as distance. A manager may choose to use multiple procedures to evaluate alternatives and come up with a final decision. Remember that the location decision is one that a company will have to live with for a long time. It is highly important that managers make the right decision. The three factors of location alternatives. Identify Dominant Location factor. Develop Location Alternatives. Evaluate Location alternative. 3. Factors that affect location decisions Factors Affecting the Location Decisions The selection of location is influenced by a number of factors. These factors can be broadly classified as market related factors such as proximity to market, tangible or cost factors such as transportation availability, and intangible or qualitative factors such as environmental aspects. Some of the factors that influence the location decision are discussed below. Market Proximity Locating facilities close to the market helps firms not only reduce transportation costs, but also serve their customers better. The firms can provide just-in-time delivery, respond to changes in demand and react quickly to field or service problems. Market proximity is a prime consideration for pure service organizations such as hotels, hospitals, retail stores and theatres. Therefore, they should always be located close to the market. Integration with Other Parts of the Organization An organization/group that already has some plants and wants to start or establish a new plant would like to locate it near to the existing plants so that its work can be integrated with that of other plants. This helps firms view the entire group as a single entity rather than as a number of independent units. Availability of Labor and Skills The availability of labor and skills is one of the important factors in production. Labor may be readily available in some areas than in other areas. Availability of skilled as well as unskilled labor in the required proportion in one area is usually not possible. Firms that emphasize more on technology require skilled people and so prefer a location where the skilled people are available. On the other hand, firms with more labor intensive processes prefer the area where the cost of labor is cheap and the labor is available plenty in number. Site Cost The management of the firm should ensure that the cost of the site is reasonable for the benefits that it is going to provide. P a g e 32 | 1 Availability of Amenities Locations with good external amenities such as housing, shops, community services, communications systems, etc. are more attractive than those located in the remote areas. For instance, personal transport system like bus and train service is considered very important by many companies. Availability of Transportation Facilities The five basic modes of physical transportation are air, road, rail, water and pipeline. Firms consider the relative costs, convenience and suitability of each mode and then select the transportation method. For instance, firms that produce goods that are to be exported may choose a location near a seaport or a large airport. Availability of Inputs Though goods transportation helps in obtaining and delivering goods and services readily, a location near to the suppliers helps the firms reduce costs. It also enables the management of the firm to meet the suppliers easily and discuss aspects like quality, technical or delivery problems. Availability of Services Electricity, water, gas, drainage, and disposal of waste are some of the important services that need to be considered while selecting a location. For example, the food and textile units require considerable quantities of water and power. Rapid communication network is required for financial services, and effective drainage and disposal system is required for process industry as it produces lot of waste. Suitability of Land and Climate Climatic conditions such as humidity, temperature and atmosphere, and the geology of the area should be considered while selecting a location. If geographic conditions are not favorable, firms have to use modern building techniques (and incur high costs) to overcome these disadvantages. For instance, a hilly, rough and rocky terrain is not suitable for a plant location, since leveling the area needs a lot of expenditure. Regional Regulations Firms should ascertain that the proposed location does not violate any local regulation and laws. The laws and regulations concerning the recruitment of employees have to be carefully studied while selecting the location. Room for Expansion While selecting a location, firms should ensure that there is adequate room for expansion of the firm's operations in the future. Safety Requirements Some units such as nuclear power stations and other chemical and explosive factories may present potential threat to the surrounding neighborhood. So firms should ensure that such units are located in remote areas where the damage will be minimal in case of an accident. Political, Cultural and Economic Situation Firms should be aware of the political, cultural and economic environment of the proposed location as these factors might affect the smooth running of the plant. For instance, firms suffer losses if their plants are located in politically and socially sensitive places. P a g e 33 | 1 Regional Taxes, Special Grants and Import / Export Barriers For developing production facilities in locations such as export promotion zones, technology parks and industrial estates, governments offer some special grants like tax holidays, infrastructure support, low-interest loans, etc. Firms can prefer to locate their units in these places. 4. Transport model Transportation Model The Transportation model uses the principle of transplanting something from one place and inserting it on another without change. First it assumes that to disturb or change the idea being transported in any way will damage and reduce it somehow. It also assumes that it is possible to take an idea from one person’s mind into another person so that the two people will then understand it exactly the same way. The transportation model is valuable tool analyzing and modifying existing transporting systems of the implementation of new ones. The model is effective in determining resource allocation in existing business structures. The model requires a few key pieces of information, which includes the following: The Origin of the supply. Destination of the supply. Unit cost of the ship. The transportation model can also be used as a comparative tool providing business decision makers with the information they need to properly balance cost and supply. This model will help decide what the optimal shipping plan is by determining a minimum cost for shipping from numerous sources to numerous destinations. This will help for comparison when identifying alternatives in terms of their impact on the final cost for a system. The main applications of the transportation model mention in this paper are location decisions, protection planning, capacity planning and shipment. Nonetheless, the major assumptions of the transporter model are as follows; 1) Items are homogenous 2) Shipping cost per unit is the same no matter how many units are shipped. 3) Only one route is used from place of shipment to the destination. The variables in this model have a linear relationship and therefore, can be into a transportation table. The table will have a list of origins and each one’s capacity of supply quantity period. It will also, show a list of destinations and their respective demands per period. It will also show the unit cost of shipping goods from each origin to each destination. Transportation costs play an important role in location decision. The transportation model can be used to compare location alternatives in terms of their impact on the total distribution costs for a system. It is subject demand satisfaction at market supply constraints. It also determines how to allocate the supplies available from the various functions to the warehouses that stock or demand those goods, in such a way that total P a g e 34 | 1 shipping cost is minimized. The total transportation cost, distribution cost of shipping cost and production cost are to be minimized by applying the model. Unit 6: Quality 1. Introduction to quality and evolution of quality management Introduction to quality and evolution of quality management Total quality management (TQM) has evolved over a number of years from ideas presented by a number of quality Gurus. Total quality management (TQM) was one of the earliest of the current wave of management ‘fashions’. Its peak of popularity was in the late 80s and early 90s. As such it has suffered from something of a backlash in recent years and there is little doubt that many companies adopted TQM in the simplistic belief that it would transform their operations performance overnight. Yet the general precepts and principles that constitute TQM are still the dominant mode of organizing operations improvement. The approach we take here is to stress the importance of the ‘total’ in total quality management and how it can guide the agenda for improvement. This is achieved by eliminating common causes of quality problems such as poor design and insufficient training and special causes such as specific machine or operator. He also places great emphasis on statistical quality control techniques and promotes extensive employee involvement in the quality improvement program. Juran put forward a 10 step plan in which he emphasizes the element of quality planning, designing the product quality level and ensuring the process can meet this quality control-using statistical process control methods to ensure quality levels are kept during the production process and quality improvementtackling quality problems trough improvement projects. Crosby suggest a 14 step programme for the implementation of TQM. The organization should consider quality both from the producer and customer point of view. Thus product design must take into consideration the production process in order that the design specification can be met. Thus it means viewing things from a customer perspective and requires that the implications from the customers are considered at all stages in corporate decision making. Secondly quality is the responsibility of all employees in all parts of the organization. In order to ensure the complete involvement of the whole organisation in all quality issues TQM uses the concept of the internal customer and internal supplier. This recognizes that everyone in the organization consumes goods and services provided by the organizational members or internal supplier. In turn every service provided by an organisation member will have internal customer. The implication is that poor quality provided within an organisation will, if allowed to go unchecked along the chain of customer/supplier relationships, eventually leads to the external customer. Therefore it is essential that every internal customers needs are satisfield. This requires a definition for each internal customer about what constitutes an acceptable quality of services. It is a principle of TQM that the responsibility for the quality should rest with the people undertaking the task which can either directly or indirectly effect the quality of customer service. P a g e 35 | 1 This requires not only a commitment to avoid mistakes but actually the capability to improve the ways in which they undertake their jobs. This requires management to adopt an approach of empowerment with people provided with training and decision making authority necessary in order that they can take responsibility for the work they are involved in and learn from their experiences. Finally a continuous process of improvement culture must be developed to instill a culture which recognizes the importance of quality to performance. 2. Quality control Quality Control in TQM TQM for quality control is ‘an effective system for integrating the quality development, quality maintenance and quality improvement efforts of the various groups in an organization so as to enable production and service at the most economical levels which allow for full customer satisfaction’. However, it was the Japanese who first made the concept work on a wide scale and subsequently popularized the approach and the term ‘TQM’. It was then developed further by several so-called ‘quality gurus’. Each ‘guru’ stressed a different set of issues, from which emerged the TQM approach. It is best thought of as a philosophy of how to approach quality improvement. This philosophy, above everything, stresses the ‘total’ of TQM. It is an approach that puts quality at the heart of everything that is done by an operation including all activities within an operation. This totality can be summarized by the way TQM lays particular stress on the following: meeting the needs and expectations of customers; covering all parts of the organization including every person in the organization; examining all costs which are related to quality, especially failure costs and getting things ‘rightfirst time’; developing the systems and procedures which support quality and improvement; developing a continuous process of improvement. Not surprisingly, several researchers have tried to establish how much of a relationship there is between adopting total quality management and the performance of the organization. One of the best-known studies found that there was a positive relationship between the extent to which companies implement TQM and its overall performance. It found that TQM practices did indeed have a direct effect on operating performance but managers should implement TQM as a whole set of ideas rather than simply picking a few techniques to implement. The same study also suggests that where TQM does not prove successful in improving performance the problems could be the result of poor implementation rather than in the TQM practices themselves, and that a serious commitment on the part of top management to TQM as a prerequisite for success. a) TQM means meeting the needs and expectations of customers Earlier we defined quality as ‘consistent conformance to customers’ expectations’. Therefore any approach to quality management must necessarily include the customer perspective. In TQM this customer perspective is particularly important. It may be referred to as ‘customer centricity’ or the ‘voice of the customer’. However it is called, TQM stresses the importance P a g e 36 | 1 of starting with an insight into customer needs, wants, perceptions, and preferences. This can then be translated into quality objectives and used to drive quality improvement. b) TQM means covering all parts of the organization For an organization to be truly effective, every single part of it, each department, each activity, each person and each level, must work properly together, because every person and every activity affects and in turn is affected by others. One of the most powerful concepts that has emerged from various improvement approaches is the concept of the internal customer/supplier. This is recognition that everyone is a customer within the organization and consumers goods or services provided by other internal suppliers, and everyone is also an internal supplier of goods and services for other internal customers. The implication of this is that errors in the service provided within an organization will eventually affect the service or product which reaches the external customer. c) TQM means including every person in the organization Every person in the organization has the potential to contribute to quality and TQM was amongst the first approach to stress the centrality of harnessing everyone’s potential contribution to quality. There is scope for creativity and innovation even in relatively routine activities, claim TQM proponents. The shift in attitude which is needed to view employees as the most valuable intellectual and creative resource which the organization possesses can still prove difficult for some organizations. Yet most advanced organizations do recognize that quality problems are almost always the results of human error. Even Google can fall victim to human error: see the short case ‘Even Google suffers “human error” ’. d) TQM means all costs of quality are considered The costs of controlling quality may not be small, whether the responsibility lies with each individual, or a dedicated quality control department. It is therefore necessary to examine all the costs and benefits associated with quality (in fact ‘cost of quality’ is usually taken to refer to both costs and benefits of quality). These costs of quality are usually categorized as prevention costs, appraisal costs, internal failure costs and external failure costs. 1. Prevention costs- are those costs incurred in trying to prevent problems, failures and errors from occurring in the first place. They include such things as: identifying potential problems and putting the process right before poor quality occurs; designing and improving the design of products and services and processes to reduce quality problems; training and development of personnel in the best way to perform their jobs; process control through SPC. 2. Appraisal costsAre those costs associated with controlling quality to check to see if problems or errors have occurred during and after the creation of the service or product. They might include such things as: the setting up of statistical acceptance sampling plans; the time and effort required to inspect inputs, processes and outputs; 3. Internal failure costsAre failure costs associated with errors which are dealt with inside the operation. These costs might include such things as: ● the cost of scrapped parts and material; ● reworked parts and materials; ● the lost production time as a result of coping with errors; ● lack of concentration due to time spent troubleshooting rather than improvement. P a g e 37 | 1 4. External failure costsAre those which are associated with an error going out of the operation to a customer. These costs include such things as: loss of customer goodwill affecting future business. aggrieved customers who may take up time. litigation (or payments to avoid litigation). guarantee and warranty costs. the cost to the company of providing excessive capability. 3. Obstacles to implementing TQM Obstacles to implementing TQM There are many obstacles of TQM as follows: The customer’s specification gap. Perceived quality could be poor because there may be a mismatch between the organization’s own internal quality specification and the specification which is expected by the customer. For example, a car may be designed to need servicing every 10,000 kilometres but the customer may expect 15,000 kilometre service intervals. The concept–specification gap. Perceived quality could be poor because there is a mismatch between the service or product concept and the way the organiza-tion has specified quality internally. For example, the concept of a car might have been for an inexpensive, energy-efficient means of transportation, but the inclusion of a climate control system may have both added to its cost and made it less energy-efficient. The quality specification–actual quality gap. Perceived quality could be poor because there is a mismatch between actual quality and the internal quality specification (often called ‘conformance to specification’). For example, the internal quality specification for a car may be that the gap between its doors and body, when closed, must not exceed 7 mm. However, because of inadequate equipment, the gap in reality is 9 mm. The actual quality–communicated image gap. Perceived quality could be poor because there is a gap between the organization’s external communications or market image and the actual quality delivered to the customer. This may be because the marketing function has set unachievable expectations or operations is not capable of the level of quality expected by the customer. For example, an advertising campaign for an airline might show a cabin attendant offering to replace a customer’s shirt on which food or drink has been spilt, whereas such a service may not in fact be available should this happen. There are also cost related obstacles to achieve TQM. 1 The Cost of Quality All the areas in the production system will incur costs as part of their TQM program. For example the marketing department will incur the cost of consumer research in trying to establish customer needs. Quality costs are categorized as either the cost of achieving good quality- the cost of quality assurance or the cost of poor quality products – the cost of not conforming to specifications. P a g e 38 | 1 2 The Cost of Achieving Good Quality The cost of maintaining an effective quality management program can be categorized into prevention costs and appraisal costs. Prevention reflects the quality philosophy of doing it right the first time and includes those costs incurred in trying to prevent problems occurring in the first place examples of prevention costs include; The cost of designing products with quality control characteristics. The cost of designing processes which conform in quality specifications. The cost of the implementation of staff training programmes. 3.Appraisal costs are the cost associated with controlling quality through the use measuring and testing products and processes to ensure that quality specifications are conformed to. Examples of appraisal costs include: The cost of testing and inspecting products The costs of maintain testing equipment The time spent in gathering data for testing The time spent adjusting equipment to maintain quality 4. Criticisms of TQM Criticisms of TQM Total Quality Management (TQM) is the approach that focuses on the customer satisfaction. In this, the main focus of the management team is on the quality of the product. The staff of the organization focuses on improving the process of manufacturing, the quality of product and services, and the culture. TQM involves the continuous process of improving the quality of the product which will satisfy the customer. It is done to retain the customer as a satisfied customer will not switch the product. The criticism of TQM is stated below: 1. Changing culture: To fulfill the satisfaction of the customer, the organization is required to change the culture of the organization. The culture of the organization involves the change in the operations of the organization. It is not possible for every organization to change the culture. 2. Time Consuming: TQM is a time-consuming process as it involves proper evaluation of the process of manufacturing a product or service. First, it is required to evaluate and then improve the quality of the product. 3. Expensive: To maintain the quality of the product huge cost is involved. It requires the cost of training the employees, improving the infrastructure of the organization, charges of the consultancy firm to provide assistance in improving quality. 4. No creativity and innovation: The staff of the organization focuses on the satisfaction of the customer. If the product satisfies the needs of the customer then it is not necessary that the innovative product will also satisfy. Thus, the management cannot use creative ideas as it may result in losing the customer. The International Organization for Standardization defines total quality management, or TQM as “a management approach for an organization, centered on quality, based on the participation of all its members and aiming at the long-term success through customer satisfaction, and benefits to all members of the organization and to society.” TQM has significant advantages in terms of quality improvement, increased productivity, greater financial yield and more customer loyalty. P a g e 39 | 1 It also has several challenges and disadvantages. Demands a Change in Culture TQM demands an organizational culture that focuses on continuous process improvement and customer satisfaction. It requires a change of attitude and a reprioritization of daily operations. TQM also requires a long-term management commitment and constant employee involvement. According to Forbes, changing an organization’s culture is a difficult challenge, because culture amalgamates an interlocking set of values, processes, attitudes, communication practices, roles, goals and assumptions, and is often met with resistance by employees, who view it as a threat to their jobs. Demands Planning, Time and Resources A good TQM system often takes years to implement, and that occurs only after significant planning, time, long-term resource allocation and unwavering management commitment. Lack of proper planning can cause a TQM system to ultimately fail. Quality is Expensive TQM is expensive to implement. Implementation often comes with additional training costs, team-development costs, infrastructural improvement costs, consultant fees and the like. The system also requires continuous investment in the form of refresher trainings, process and machine inspections, and quality measurement. TQM is not suitable for very small companies, because its implementation, training and execution costs far supersede its financial gains. Takes Years to Show Results TQM is a long-term process that shows results only after years have passed. It requires perseverance, patience, dedication and motivation. Many organizations give up on it after failing to see tangible results quickly. Organizations that function in highly competitive environments cannot afford the luxury of time. Discourages Creativity TQM’s focus on task standardization to ensure consistency discourages creativity and innovation. It also discourages new ideas that can possibly improve productivity. Not a Quick-Fix Solution Many companies, in their excessive focus on quality, end up losing financially. Both Xerox, the American document management company, and Federal Express, the cargo airline, suffered significant financial setbacks after winning the Baldrige Quality Awards- awards that recognize quality performance. According to the book, "Corporate Transformation and Restructuring," two-thirds of companies that embrace TQM fail to experience major performance breakthroughs or improvements in customer satisfaction. According to an Arthur D. Little survey of 500 companies, only 36 percent felt that TQM improved their competitiveness. 5. Process improvement PROCESS TO IMPROVEMENT Achieving conformance to improvement requires the following steps: Step 1 Define the quality characteristics of the service or product. Step 2 Decide how to measure each quality characteristic. Step 3 Set quality standards for each quality characteristic. Step 4 Control quality against those standards. P a g e 40 | 1 Step 5 Find and correct causes of poor quality. Step 6 Continue to make improvements. Step 1 – Define the quality characteristics Much of the ‘quality’ of a service or product will have been specified in its design and can be summarized by a set of quality characteristics. Also many services have several elements, each with their own quality characteristics, and to understand the quality characteristics of the whole service it is necessary to understand the individual characteristics within and between each element of the whole service. For example, table below shows some of the quality characteristics for a web-based online grocery shopping service. Step 2 – Decide how to measure each characteristic These characteristics must be defined in such a way as to enable them to be measured and then controlled. This involves taking a very general quality characteristic such as ‘appearance’ and breaking it down, as far as one can, into its constituent elements. ‘Appearance’ is difficult to measure as such, but ‘colour match’, ‘surface finish’ and ‘number of visible scratches’ are all capable of being described in a more objective manner. They may even be quantifiable. Other quality characteristics pose more difficulty. The ‘courtesy’ of airline staff, for example, has no objective quantified measure. Yet operations with high customer contact, such as airlines, place a great deal of importance on the need to ensure courtesy in their staff. In cases like this, the operation will have to attempt to measure customer perceptions of courtesy. P a g e 41 | 1 Step 3 – Set quality standards When operations managers have identified how any quality characteristic can be measured, they need a quality standard against which it can be checked; otherwise they will not know whether it indicates good or bad performance. The quality standard is that level of quality which defines the boundary between acceptable and unacceptable. Such standards may well be constrained by operational factors such as the state of technology in the factory, and the cost limits of making the product. At the same time, however, they need to be appropriate to the expectations of customers. But quality judgements can be difficult. If one airline passenger out of every 10,000 complains about the food, is that good because 9,999 passengers out of 10,000 are satisfied? Or is it bad because, if one passenger complains, there must be others who, although dissatisfied, did not bother to complain? And if that level of complaint is similar to other airlines, should it regard its quality as satisfactory? Step 4 – Control quality against those standards After setting up appropriate standards the operation will then need to check that the products or services conform to those standards; doing things right, first time, every time. This involves three decisions: 1 Where in the operation should they check that it is conforming to standards? 2 Should t hey check every service or product or take a sample? 3 How should the checks be performed? Developing the systems and procedures which support quality and improvement The emphasis on highly formalized systems and procedures to support TQM has declined in recent years, yet one aspect is still active for many companies. This is the adoption of the ISO 9000 standard. And although ISO 9000 can be regarded as a stand-alone issue, it is very closely associated with TQM. ISO 9000 provides a standard quality standard between the supplier and a customer that helps to reduce the complexity of managing a number of different quality standards when a customer has many suppliers. ISO 9000 is a series of standards for quality management and assurance and has five major subsections as follows: ISO 9000 IS0 9001 provides guidelines for the use of the following four standards in the series applies when the supplier is responsible for the development, designing, production, installation, and servicing of the products ISO9002 applies when the supplier is responsible for production and installation ISO9003 applies to final inspection and testing of products P a g e 42 | 1 ISO 9004 provide guidelines for managers of organization to help them to develop their quality system. It gives suggestions to help organizations meet the requirements of the previous four standards. The standards is general enough to apply to almost any good or service, but it is a specific organisation or facility that is registered or certified to the standard. To achieve certification a facility must document its procedures for every element in the standard. These procedures are then audited by the third party periodically. The system thus ensures that the organization is following a documented and thus consistent, procedure which makes errors easier to find and correct. However the system does not improve quality in itself and has been criticized for incurring cost in maintaining documentation which not providing guidance in quality improvement techniques such as statistical process control. The ISO 9000 approach The ISO 9000 series is a family of standards compiled by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) which is the world’s largest developer and publisher of International Standards, based in Geneva, Switzerland. According to the ISO ‘the standards represent an inter-national consensus on good quality management practices. It consists of standards and guide-lines relating to quality management systems and related supporting standards’. To be precise, it is the ‘ISO 9001:2008’ standard that provides the set of standardized requirements for a quality management system which should apply to any organization, regardless of size, or whether it is in the private or public sector. It is the only standard in the family against which organizationscan be certified – although certification is not a compulsory requirement of the standard. Its purpose when it was first framed was to provide an assurance to the purchasers of products or services that they have been produced in such a way that they meet their requirements. The best way to do this, it was argued, was to define the procedures, standards and characteristics of the management control system which governs the operation. Such a sys-tem would help to ensure that quality was ‘built into’ the operation’s transformation processes. Rather than using different standards for different functions within a business, it takes a ‘process’ approach that focuses on outputs from any operation’s process rather than detailed procedures. This process orientation requires operations to define and record core processes and sub-processes. In addition, processes are documented using the process mapping approach. It also stresses four other principles: ● Quality management should be customer-focused. Customer satisfaction should be measured through surveys and focus groups and improvement against customer standards should be documented. ● Quality performance should be measured. In particular, measures should relate both to processes that create products and services and customer satisfaction with those prod-ucts and services. Furthermore, measured data should be analyzed in order to understand processes. ● Quality management should be improvement-driven. Improvement must be demonstrated in both process performance and customer satisfaction. ● Top management must demonstrate their commitment to maintaining and continually improving management systems. This commitment should include communicating the P a g e 43 | 1 importance of meeting customer and other requirements, establishing a quality policy and quality objectives, conducting management reviews to ensure the adherence to quality policies, and ensuring the availability of the necessary resources to maintain quality systems. The ISO illustrates the benefits of the standard as follows: ‘Without satisfied customers, an organization is in peril! To keep customers satisfied, the organization needs to meet their requirements. The ISO 9001:2008 standard provides a tried and tested framework for taking a systematic approach to managing the organization’s processes so that they consistently turn out product that satisfies customers’ expectations.’ In addition, it is also seen as providing benefits both to the organizations adopting it (because it gives them detailed guidance on how to design their control procedures) and especially to customers (who have the assurance of knowing that the products and services they purchase are produced by an operation working to a defined standard). Further, it may also provide a useful discipline to stick to ‘sensible’ process- orientated procedures which lead to error reduction, reduced customer complaints and reduced costs of quality, and may even identify existing procedures which are not necessary and can be eliminated. Moreover, gaining the certificate demonstrates that the company takes quality seriously; it therefore has a marketing benefit. Unit 7: Inventory Management 1. Effective inventory management Effective inventory management Operations managers need to manage the day-to-day tasks of managing inventory. Orders will be received from internal or external customers; these will be dispatched and demand will gradually deplete the inventory. Orders will need to be placed for replenishment of the stocks; deliveries will arrive and require storing. In managing the system, operations managers are involved in three major types of decision: ● How much to order. Every time a replenishment order is placed, how big should it be some-times called the volume decision? ● When to order. At what point in time, or at what level of stock, should the replenishment order be placed sometimes called the timing decision? ● How to control the system. What procedures and routines should be installed to help make these decisions? Should different priorities be allocated to different stock items? How should stock information be stored? Decisions on how much to order for effective management of the inventory 1. Volume decision To illustrate this decision, consider again the example of the food and drinks we keep at our home. In managing this inventory we implicitly make decisions on order quantity , which is how much to purchase at one time. In making this decision we are balancing two sets of costs: the costs associated with going out to purchase the food items and the costs associated with holding the stocks. The option of holding very little or no inventory of food and purchasing each item only when it is needed has the advantage that it requires little money since purchases are made only when needed. However, it would involve purchasing provisions several times a day, which is inconvenient. At the very opposite extreme, making one P a g e 44 | 1 journey to the local superstore every few months and purchasing all the provisions we would need until our next visit reduces the time and costs incurred in making the purchase but requires a very large amount of money each time the trip is made – money which could otherwise be in the bank and earning interest. We might also have to invest in extra cupboard units and a very large freezer. Somewhere between these extremes there will lie an ordering strategy which will minimize the total costs and effort involved in the purchase of food. 2. Inventory costs The same principles apply in commercial order-quantity decisions as in the domestic situation. In making a decision on how much to purchase, operations managers must try to identify the costs which will be affected by their decision. Earlier we examined how inventory decisions affect some of the important components of return on assets. Here we take a cost perspective and re-examine these components in order to determine which costs go up and which go down as the order quantity increases. Inventory management can have a decrease as order size is increased, whereas the next four generally increase as order size is increased: 1. Cost of placing the orderEvery time that an order is placed to replenish stock, a number of transactions are needed which incur costs to the company. These include preparing the order, communicating with suppliers, arranging for delivery, making payment, and maintaining internal records of the transaction. Even if we are placing an ‘internal order’ on part of our own operation, there are still likely to be the same types of transaction concerned with internal administration. 2. Price discount costs. Often suppliers offer discounts for large quantities and cost penalties for small orders. 3. Stock-out costs. If we misjudge the order-quantity decision and our inventory runs out of stock, there will be lost revenue (opportunity costs) of failing to supply customers. External customers may take their business elsewhere, internal customers will suffer process inefficiencies. 4 Working capital costs. After receiving a replenishment order, the supplier will demand payment. Of course, eventually, after we supply our own customers, we in turn will receive payment. However, there will probably be a lag between paying our suppliers and receiving payment from our customers. During this time we will have to fund the costs of inventory. This is called the working capital of inventory. The costs associated with it are the interest we pay the bank for borrowing it, or the opportunity costs of not investing it elsewhere. 5 Storage costsThese are the costs associated with physically storing the goods. Renting, heating and lighting the warehouse, as well as insuring the inventory, can be expen-sive, especially when special conditions are required, such as low temperatures or high security. 6 Obsolescence costs . When we order large quantities, this usually results in stocked items spending a long time stored in inventory. This increases the risk that the items might either become P a g e 45 | 1 obsolete (in the case of a change in fashion, for example) or deteriorate with age (in the case of most foodstuffs, for example). 8. Operating inefficiency costsAccording to just-in-time philosophies, high inventory levels prevent us seeing the full extent of problems within the operation. It is worth noting that it may not be the same organization that incurs the costs. For example, sometimes suppliers agree to hold consignment stock. This means that they deliver large quantities of inventory to their customers to store but will only charge for the goods as and when they are used. In the meantime they remain the supplier’s property so do not have to be financed by the customer, who does however provide storage facilities. Inventory profiles An inventory profile is a visual representation of the inventory level over time. Every time an order is placed, Q items are ordered. The replenishment order arrives in one batch instantaneously. Demand for the item is then steady and perfectly predictable at a rate of D units per month. When demand has depleted the stock of the items entirely, another order of Q items instantaneously arrives, and so on. Why should there be an inventory? There are plenty of reasons to avoid accumulating inventory where possible The following are some of the benefits of inventory. 1. Physical inventory is an insurance against uncertainty-Inventory can act as a buffer against unexpected fluctuations in supply and demand. For example, a retail operation can never forecast demand perfectly over the lead-time. It will order goods from its suppliers such that there is always a minimum level of inventory to cover against the possibility that demand will be greater than expected during the time taken to deliver the goods. This is buffer, or safety, inventory. It can also compensate for the uncertainties in the process of the supply of goods into the store. The same applies with the output inventories, which is why hospitals always have a supply of blood, sutures and bandages for immediate response to Accident and Emergency patients. Similarly, auto-servicing services, factories and airlines may hold selected critical spare parts inventories so that Inventory should only accumulate when the advantages of having it outweigh its disadvantages. Primarily time-cost to the customer, i.e. wastes customers’ time Cost of set-up, access, updating and maintenance staff can repair the most common faults without delay. Again, inventory is being used as an ‘insurance’ against unpredictable events. 2. Physical inventory can counter act a lack of flexibilityWhere a wide range of customer options is offered, unless the operation is perfectly flexible, stock will be needed to ensure supply when it is engaged on other activities. This is sometimes called cycle inventory. Because of the nature of the mixing and baking process, only one kind of bread can be produced at any time. The baker will have to produce each type of bread in batches large enough to satisfy the demand for each kind of bread between the times when each batch is ready for sale. So, even when demand is steady and predictable, there will always be some inventory to compensate for the intermittent supply of each type of bread. 3. Physical inventory allows operations to take advantage of short-term opportunities Sometimes opportunities arise that necessitate accumulating inventory, even when there P a g e 46 | 1 is no immediate demand for it. For example, a supplier may be offering a particularly good deal on selected items for a limited time period, perhaps because they want to reduce their own finished goods inventories. Under these circumstances a purchasing department may opportunistically take advantage of the short-term price advantage. Physical inventory can be used to anticipate future demands- Medium-term capacity management may use inventory to cope with demand. Rather than trying to make a product (such as chocolate) only when it is needed, it is produced throughout the year ahead of demand and put into inventory until it is needed. This type of inventory is called anticipation inventory and is most commonly used when demand fluctuations are large but relatively predictable. 3. Physical inventory can reduce overall costsHolding relatively large inventories may bring savings that are greater than the cost of holding the inventory. This may be when bulk-buying gets the lowest possible cost of inputs, or when large order quantities reduce both the number of orders placed and the associated costs of administration and material handling. This is the basis of the ‘economic order quantity’ (EOQ) approach that will be treated later in this 4. Physical inventory can increase in valueSometimes the items held as inventory can increase in value and so become an investment. For example, dealers in fine wines are less reluctant to hold inventory than dealers in wine that does not get better with age. (However, it can be argued that keeping fine wines until they are at their peak is really part of the overall process rather than inventory as such.) A more obvious example is inventories of money. The many financial processes within most organizations will try to maximize the inventory of cash they hold because it is earning them interest. 2. EOQ model The economic order quantity (EOQ) formula The most common approach to deciding how much of any particular item to order when stock needs replenishing is called the economic order quantity (EOQ) approach. This approach attempts to find the best balance between the advantages and disadvantages of holding stock. For example, Figure below shows two alternative order-quantity policies for an item. Plan A, represented by the unbroken line, involves ordering in quantities of 400 at a time. Demand in this case is running at 1,000 units per year. Plan B, represented by the dotted line, uses smaller but more frequent replenishment orders. This time only 100 are ordered at a time, with orders being placed four times as often. However, the average inventory for plan B is one-quarter of that for plan A. To find out whether either of these plans, or some other plan, minimizes the total cost of stocking the item, we need some further information, namely the total cost of holding one unit in stock for a period of time (Ch) and the total costs of placing an order (Co). Generally, holding costs are taken into account by including: ● working capital costs ● storage costs ● obsolescence risk costs. Order costs are calculated by taking into account: ● cost of placing the order (including transportation of items from suppliers if relevant); P a g e 47 | 1 ● price discount costs. P a g e 48 | 1 P a g e 49 | 1 Sensitivity of the EOQ Examination of the graphical representation of the total cost curve in Figure above shows that, although there is a single value of Q which minimizes total costs, any relatively small devia-tion from the EOQ will not increase total costs significantly. In other words, costs will be near-optimum provided a value of Q which is reasonably close to the EOQ is chosen. Put another way, small errors in estimating either holding costs or order costs will not result in a significant deviation from the EOQ. This is a particularly convenient phenomenon because, in practice, both holding and order costs are not easy to estimate accurately. P a g e 50 | 1 Worked Example The approach to determining order quantity which involves optimizing costs of holding P a g e 51 | 1 stock against costs of ordering stock, typifi ed by the EOQ models, has always been subject to criticisms. Originally these concerned the validity of some of the assumptions of the model; more recently they have involved the underlying rationale of the approach itself. The criticisms fall into four broad categories, all of which we shall examine further: ● The assumptions included in the EOQ models are simplistic. ● The real costs of stock in operations are not as assumed in EOQ models. ● The models are really descriptive, and should not be used as prescriptive devices. ● Cost minimization is not an appropriate objective for inventory management. Responding to the criticisms of EOQ In order to keep EOQ-type models relatively straightforward, it was necessary to make assumptions. These concerned such things as the stability of demand, the existence of a fixed and identifiable ordering cost, that the cost of stock holding can be expressed by a linear function, shortage costs which were identifiable, and so on. While these assumptions are rarely strictly true, most of them can approximate to reality. Furthermore, the shape of the total cost curve has a relatively flat optimum point which means that small errors will not significantly affect the total cost of a near-optimum order quantity. However, at times the assumptions do pose severe limitations to the models. For example, the assumption of steady demand (or even demand which conforms to some known probability distribution) is untrue for a wide range of the operation’s inventory problems. For example, a bookseller might be very happy to adopt an EOQ-type ordering policy for some of its most regular and stable products such as dictionaries and popular reference books. However, the demand patterns for many other books could be highly erratic, dependent on critics’ reviews and word-of-mouth recommen-dations. In such circumstances it is simply inappropriate to use EOQ models. Cost of stock Other questions surround some of the assumptions made concerning the nature of stockrelated costs. For example, placing an order with a supplier as part of a regular and multi-item order might be relatively inexpensive, whereas asking for a special one-off delivery of an item could prove far more costly. Similarly with stock-holding costs – although many companies make a standard percentage charge on the purchase price of stock items, this might not be appropriate over a wide range of stock-holding levels. The marginal costs of increasing stock-holding levels might be merely the cost of the working capital involved. On the other hand, it might necessitate the construction or lease of a whole new stock-holding facility such as a warehouse. Operations managers using an EOQ-type approach must check that the decisions implied by the use of the formulae do not exceed the boundaries within which the cost assumptions apply. An EOQ approach of regarding inventory as being more costly than previously believed. Increasing the slope of the holding cost line increases the level of total costs of any order quantity, but more significantly, shifts the minimum cost point substantially to the left, in favour of a lower economic order quantity. In other words, the less willing an operation is to hold stock on the grounds of cost, the more it should move towards smaller, more frequent ordering. Using EOQ models as prescriptions Perhaps the most fundamental criticism of the EOQ approach again comes from the Japanese-inspired ‘lean’ and JIT philosophies. The EOQ tries to optimize order decisions. Implicitly the costs involved are taken as fixed, in the sense that the task of operations managers is to find out what the true costs are rather than to change them in any way. EOQ is essentially a reactive approach. Some critics would argue that it fails to ask the right question. P a g e 52 | 1 Rather than asking the EOQ question of ‘What is the optimum order quantity?’ operations managers should really be asking, ‘How can I change the operation in some way so as to reduce the overall level of inventory I need to hold?’ The EOQ approach may be a reasonable description of stock-holding costs but should not necessarily be taken as a strict prescription over what decisions to take. For example, many organizations have made considerable efforts to reduce the effec -tive cost of placing an order. Often they have done this by working to reduce changeover times on machines. This means that less time is taken changing over from one product to the other, and therefore less operating capacity is lost, which in turn reduces the cost of the changeover. Under these circumstances, the order cost curve in the EOQ formula reduces and, in turn, reduces the effective economic order quantity. Figure 12.9 shows the EOQ formula represented graphically with increased holding costs ( see the previous discussion) and reduced order costs. The net effect of this is to significantly reduce the value of the EOQ. Should the cost of inventory be minimized? Many organizations (such as supermarkets and wholesalers) make the most of their revenue and profits simply by holding and supplying inventory. Because their main investment is in the inventory it is critical that they make a good return on this capital, by ensuring that it has the highest possible ‘stock turn’ (defined later in this chapter) and/or gross profit margin. Alternatively, they may also be concerned to maximize the use of space by seeking to maximize the profit earned per square metre. The EOQ model does not address these objectives. Similarly, for products that deteriorate or go out of fashion, the EOQ model can result in excess inventory of slower-moving items. In fact the EOQ model is rarely used in such organizations, 3. Fixed Order Interval model FIXED ORDER INTERVAL SYSTEM Fixed Order Interval System is a method of inventory control system. It is also known as fixed reorder cycle inventory model. In this, a fixed interval is developed by keeping a check on the demand of the product. It is used in managing the supply of the raw material. In fixed order interval system, the stock levels are evaluated and a periodic schedule of fixed order is developed. This operation is developed on the basis of time. Stock levels refer to the inventory or the stock kept in the warehouse of the organization. Fixed order interval system involves a regular check of the inventory so as to develop an interval of reordering. It is important for the efficient and effective operations of the organization. Through this, there will be no surplus inventory kept in the warehouse. Thus, the cost of storing inventory is reduced. The supplier of the raw material mostly accepts this method of inventory system as there is no uncertainty of changing the orders. Suppliers know the quantity and the time period of reordering. So, the inventory is not kept idle in the warehouse. It is delivered as per the time of its requirement. Thus, the supplier is secured as there are fewer chances of switching the supplier. The quantity of the order is determined by the three factors: P a g e 53 | 1 1. The daily usage which is anticipated. It is developed by analyzing the inventory regularly. 2. The time period which occurs between the analyses of the inventory. 3. The quantity of inventory available and the demand for the product. 4. Single model A single period inventory model is a business scenario faced by companies that order seasonal or one-time items. There is only one chance to get the quantity right when ordering, as the product has no value after the time it is needed. There are costs to both ordering too much or too little, and the company's managers must try to get the order right the first time to minimize the chance of loss. The single period inventory model is often explained in terms of the "newsboy problem." A newsboy who stands on the corner and sells papers to passers-by must order the papers the day before. He only has one chance to order because the papers only have any value on the day they are published; the next day they are worth nothing. If he orders too many he'll have to absorb the loss of the unsold papers, and if he orders too few he will have lost profits and annoyed customers. Getting the order quantity correct is how the newsboy makes the most profit. The Cost of Ordering Too Much Stocking too much of a seasonal item can lead to large losses for a business. In the case of Christmas cards, for example, sales go to zero on the day after Christmas. The company has the choice of destroying the remaining inventory, selling some at huge discounts or storing them until next Christmas. The latter option may save the cost of the inventory, but will cost the company in warehouse and storage fees. Inventory that is dated, such as magazines or royal wedding memorabilia, may have no market after the date. The Cost of Ordering Too Little There are many costs associated with having too little inventory on hand, and not all of them are directly financial. The main cost is the lost opportunity to make profit. The difference between the sales price and the cost multiplied by the number of customers who had to be turned away equals the lost profit. It could even be higher if some customers told others that the company was out of stock and those potential customers did not show up. A more subtle but just as damaging cost is customer goodwill. If customers are expecting to be able to buy a product from you and cannot because you ordered ineffectively, their annoyance can extend farther and they may choose to buy products elsewhere in the future. Marginal Analysis Approach The marginal analysis approach is one way to find the order quantity that has the best chance of being correct. The cost of ordering one more unit is compared to the profit gained P a g e 54 | 1 of ordering another unit. Quantitative analysis is used to determine the economic order quantity based on expected demand and the costs of getting it wrong. Complex calculations are often used to come up with a statistically sound order quantity. Unit 8: Just in Time Systems 1. Conversional systems Conversional systems Just-in- time (JIT) is a philosophy originating from Japanese auto maker Toyota where Taiiichi ohno developed the Toyota Production system. The basic idea behind JIT is to produce only what you need, when you need it. This may seem a simple idea but to deliver it requires a number of elements in place such as the elimination of wasteful activities and continuous improvements. Eliminate Waste Waste is considered in the widest sense as any activity which does not add value to the operation seven types of wastes identified by Toyota are as follows; Waiting time; this is the time spent by labour or equipment waiting to add value to a product. This May be disguised by undertaking unnecessary operations ( e.g generating work in progress (WIP) on a machine) which are not immediately needed ( i.e the waste is converted from time to WIP) Transport; unnecessary transportation of WIP is another source of waste. Layout changes can substantially reduce transportation time. Process; some operation do not add value to the product but are simply there because of poor design or machine maintenance. Improved design or preventative maintenance should eliminate these process. Inventory; inventory of all types ( e,g pipeline cycle) is considered as waste and should be eliminated Motion; simplification of work movement will reduce waste caused by unnecessary motion of labour and equipment. Defective goods; the total costs of poor quality can be very high and will include scrap material, wasted labour time and time expediting orders and loss goodwill through missed delivery dates. Continuous improvement Continuous improvement or Kaizen, the Japanese term is a philosophy which believes that it is possible to get to the ideas of JIT by continuous stream of improvements over time. JIT pull system P a g e 55 | 1 2. Conversion to a JIT system The idea of pull system comes from the need to reduce inventory within the production system. In a push system a schedule pushes work on to machines which is then passed through to the next work centre. A production system for an automobile will require the coordination of thousands of components many of which will need to be grouped together to form an assembly. In order to ensure that there is no stoppages it is necessary to have inventory in the system because it is difficult to coordinate parts to arrive at a particular station simultaneously. The pull system comes from the idea a supermarket in which items are purchased by a customer only when needed and are replenished as they are removed. The inventory coordination is controlled by a customer pulling items from the system which are then replaced as needed. To implement a pull system a Kanban (Japanese for ‘card’ or ‘sign’) is used to pass the information through the production system. Each Kanban provides information on the part identification quality per container that the part is transported in the preceding and next work station. Kanban in themselves do not provide the schedule for production but without them production cannot take place as they authorize the production and movement of materials through the pull system. Kanban need not to be a card, but something that can be used aa a signal for production such as marked area of flootspace. There are two types of Kanban system, the single card and the two card. The single card system uses only one type of Kanban system called the conveyance Kanban which authorizes the movement of parts. The number of containers at a work centre is limited by the number of Kanbans. A signal to replace inventory at work centre can only be sent when the container is emptied. Toyota use a dual card system which in addition to the conveyance Kanban, utilizes a production Kanban to authorize the production of parts. This system permits greater control over production as well as inventory. If the processes are tightly linked (i.e one always follows the other) then a single Kanban can be used in order for a Kanban system to be implemented it is important that the seven operations rules that govern the system are followed. These rules can be summarized as follows; Move a Kanban only when the lot it represents is consumed No withdrawal of parts without a Kanban is allowed The number of parts issued to the subsequent process must be the exact number specified by the Kanban A Kanban should always be attached to the physical product P a g e 56 | 1 The preceding process should always produce its parts in the quantities withdrawn by the subsequent process. Defective parts should never be conveyed to the subsequent process A high level of process must be maintained because of the lack of buffer inventory. A feedback mechanism which reports quality problems quickly to the preceding process must be implemented. Process the Kanban in every work Centre strictly in order in which they arrive at the work Centre If several Kanban are waiting for production they must be served in the order that they have arrived. If the rule is not followed there will be a gap in the production rate of one or more of the subsequent processes. The system is implemented with a given number of cards in order to obtain a smooth floor. The number of cards is then decreased, decreasing inventory and any problem which surface are tackled. Cards are decreased one at a time to continue the continuous improvement process. 3. Goals and objectives of JIT GOALS AND OBJECTIVE OF JIT Definition of Just-In-Time (JIT) Method: Just-In-Time (JIT) is a purchasing and inventory control method in which materials are obtained just-in-time for production to provide finished goods just-in-time for sale. JIT is a demand-pull system. Demand for customer output (not plans for using input resources) triggers production. Production activities are “pulled” not “pushed” into action. As philosophy, JIT targets inventory as an evil pres-ence that obscures problems that should be solved, and declares that, by contributing significantly to casts, target inventories keep a company from being as competitive or profitable as it otherwise might be. A just-in-time manufacturing system requires making goods or service only when the customer, internal or external, requires it. JIT requires better coordination with suppliers so that materials ar-rive immediately prior to their use. It reduces or eliminates inventory and the costs associated with carrying the inventory. It emphasises that workers immediately correct the system making defective units because they have no inventory. With no inventory to draw from for delivery to customers, just-in-time relies on high quality materials and production. It is required that the companies that use just-in-time manufacturing must eliminate all the sources of failure in the system. Production people must be better trained so that they can carry out their works without errors. Suppliers must be able to produce and deliver defect free materials or components just when they are required, and equipment must be maintained so that machine failures are eliminated. P a g e 57 | 1 Objectives of Just-In-Time (JIT) Method: JIT aims to achieve the following objectives in the inventory system: (i) Zero inventory (ii) Zero breakdowns (iii) 100% on time delivery service (iv) Elimination of non-value added activities (v) Zero defects. The major differences between JIT manufacturing and traditional manufacturing are as follows: Difference between JIT and Traditional Manufacturing JIT applies to raw materials inventory as well as to work-in-process inventory. The goals are that both raw materials and work in process inventory are held to absolute minimums. JIT is used to complement other materials planning and control tools, such as EOQ and safety stock levels. In JIT system, production of an item does not commence until the organisation receives an order. When an order is received for a finished product, productions people give orders for raw materials. As soon as production is complete to fill the order, production ends. In theory, in JIT, there is no need for inventories because no production takes place until the organisation knows that it will sell them. In practice, however, companies using just-in-time inventory generally have a backlog of orders or stable demand for their products to assure continued production. The fundamental objective of JIT is to produce and deliver what is needed, when it is needed, at all stages of the production process-just-in-time to be fabricated, sub-assembled, assembled, and dispatched to the customer. Although in practice there are no such perfect plants, JIT is an ideal and therefore a worthy goal. The benefits are low inventory, high manufacturing cycle rates, high output per employee, minimum floor space requirements, minimum indirect labour, and perfect in-process control. An associated requirement of a successful JIT operation is the pursuit of perfect quality in order to reduce, to an absolute minimum, delays caused by defective product units. Example: Godrej Manufacturing has developed value-added standards for its activities among which are the following three: materials usage, purchasing, and inspecting. The value-added output levels for each of the activities, their actual levels achieved, and the standard prices are as follows: Value-added output levels P a g e 58 | 1 Assume that material usage and purchasing costs correspond to flexible resources (acquired as needed) and inspection uses resources that are acquired in blocks, or steps, of 2,000 hours. The actual prices paid for the inputs equal the standard prices. Required: 1. Assume that continuous improvement efforts reduce the demand for inspection by 30 percent during the year (actual activity usage drops by 30 percent). Calculate the activity volume and unused capacity variances for the inspection activity. Explain their meaning. Also, explain why there is no activity volume or unused capacity variance for the other two activities. 2. Prepare a cost report that details value-added and non-value-added costs. 3. Suppose that the company wants to reduce all non-value-added costs by 30 percent in the coming year. Prepare kaizen standards that cap be used to evaluate the company’s progress toward this goal. How much will this save in resource spending? 4. Suppose that Godrej Manufacturing has implemented the Balanced Scorecard. Explain how non-value-added cost reduction, non-value-added cost reports, and kaizen standards might fit into the Balanced Scorecard framework. Just-In-Time (JIT) Method - Solution There is no reduction in resource spending for inspecting because it must be purchased In increments of 2,000 and only 1,200 hours were saved—another 800 hours must be reduced before any reduction in resource spending is possible. The unused capacity variance must reach Rs 2, 40,000 before resource spending can be reduced. 4. The Balanced Scorecard has four perspectives: financial, customer, process, and learning and growth. One of the objectives of the financial perspective is reducing the unit costs of products. Reducing non-value-added costs should produce a reduction in the company’s product costs. But the most direct connection to the Balanced Scorecard is with the internal process perspective of the Balanced Scorecard. Value- and non-value-added cost reports are financial measures that relate to internal process efficiency. Similarly, kaizen standards deal with improving internal process efficiency. Activity volume variances and unused capacity measures also are concerned with process efficiency. Finally, the value of the Balanced Scorecard relative to these measures is that the Balanced Scorecard will integrate these measures into the overall strategic framework. The learning and growth perspective provides the enabling factors needed to reduce nonvalue-added costs. What good are non-value-added cost reports if nobody has the capability of finding ways to improve activities and processes? As process efficiency increases and costs are reduced, then customer value can be increased by reducing prices. As customer value increases, market share may increase, and this, in turn, may increase revenues and profits. P a g e 59 | 1 4. JIT JIT Most manufacturing facilities are looking to lower the costs associated with their production in order to maximize their profits. Over time, many scheduling techniques have emerged as a way to help these manufacturing facilities meet their production goals and increase their efficiency. Just-In-Time manufacturing was designed to help manufacturers reduce inventory-related costs by receiving materials and producing goods only when they are needed. Just-In-Time scheduling is used to accommodate last-minute changes to orders and prevent damage or spoilage of inventory by preventing jobs from starting too early. JUST-IN-TIME (JIT) MANUFACTURING When the techniques are implemented, production facilities are able to align their raw material orders directly to their production schedules so that these items do not have to be stored for long periods of time. Just-In-Time production scheduling prevents jobs from being scheduled much before they are needed, which requires WIP items to be held in inventory. JIT means that your production operations start with just enough time to be completed by the need date so that your goods are being produced to ship, not to be stored. There are many benefits associated with Just-In-Time production, but the main goals of this method is to increase the efficiency of production while decreasing waste to ultimately lower the production costs and increase profits. On the flip side, implementing JIT methodology requires producers to be able to accurately forecast their demand to avoid running into material shortages. Before implementing Just-In-Time strategies, it is essential to understand the advantages and disadvantages of the process. The advantages of Just-In-Time (JIT) manufacturing include the following: Reduced Space Needed - With JIT you have a faster turnaround of stock, which means that you do not need a lot of warehouse or storage space to store goods or materials. Ultimately, this will reduce the amount of storage space your organization will need to rent or buy, which will free up funds for other parts of the business. Smaller Investments - JIT inventory management is an ideal methodology for small production facilities that do not have the funds needed in order to purchase huge amounts of stock at once. Ordering stock materials only when they are needed enables you to maintain a healthy and smooth cash flow. Waste Elimination/Reduction - A quicker turnaround of stock prevents goods that have become damaged or obsolete while sitting in storage, reducing waste. This again saves money through preventing investment in any unnecessary stock and reducing the need to replace old stock. P a g e 60 | 1 While there are many advantages to the Just-In-Time manufacturing methodology, there are also some drawbacks to it as well. Listed below are some of the disadvantages of Just-InTime (JIT) manufacturing. Disadvantages of Just-In-Time (JIT) Manufacturing The disadvantages of Just-in-Time (JIT) Manufacturing include the following: Risk of Running Out of Stock - With JIT manufacturing, you do not carry as much stock. This is because you base your stock off of demand forecasts, and if those are incorrect, then you will not have the correct amount of stock readily available for your consumers. This is one of the most common issues with manufacturing that utilize methodologies such as JIT and lean. Dependency on Suppliers - Having to rely on the timelessness of suppliers for each order puts you at risk of delaying your customers’ receipt of goods. If you are unable to meet consumer expectations, then they could take their business elsewhere. This is why it is important to choose reliable suppliers and have a strong relationship with them so that you can make sure that you have the materials you need to meet your customer demands. More Planning Required - JIT inventory management requires companies to understand sales trends and variances in close detail. Many companies have seasonal sales periods, meaning that a number of products will need a higher stock level to combat consumer demand. Therefore, you must plan ahead for instances like this and ensure that your suppliers are able to fulfill the requirements. 5. JIT in services JIT IN SERVICE Just in time (JIT) manufacturing is a workflow methodology aimed at reducing flow times within production systems, as well as response times from suppliers and to customers. A digital Kanban board is an essential element of any true just-in-time manufacturing system. JIT manufacturing helps organizations control variability in their processes, allowing them to increase productivity while lowering costs. JIT manufacturing is very similar to Lean manufacturing, and the terms are often used synonymously. The ins and outs of JIT manufacturing, including its history, the basic concepts included in this methodology, and its potential risks. Applying JIT only to manufacturing you may not see how JIT could be applicable to service organizations. However, we have seen in this chapter that JIT is an all-encompassing philosophy that includes eliminating waste, improving quality, continuous improvement, increased responsiveness to customers, and increased speed of delivery. That philosophy is equally applicable to any organization, service or manufacturing. Following are examples of JIT concepts seen in service firms. P a g e 61 | 1 Improved Quality Service quality is often measured by intangible factors such as timeliness, service consistency, and courtesy. Building quality into the process of service delivery and implementing concepts such as quality at the source can significantly improve service quality dimensions. For example, McDonald's has become famous by building quality into the process and standardizing the service delivery system. Regardless of location, McDonald's customers receive the same product and service consistency. Uniform Facility Loading The challenge for service operations is synchronizing their production with demand. Many service firms have developed unique ways to level customer demand in order to provide better service responsiveness. For example, hotels and restaurants use. Supporting a JIT manufacturing system requires discipline, structure, and explicit processes. In addition to strictly limiting inventory, the following methods are included in a true JIT system: Housekeeping – physical organization and discipline Setup reduction and flexible changeover approaches Small lot sizes Uniform plant load – leveling as a control mechanism Balanced flow – actively managing flow by limiting batch sizes Skill diversification – multi-functional workers Control by visibility – using visual tools to improve communication Designing for process Streamlining the movement of materials Cellular manufacturing Pull system Elimination of defects P a g e 62 | 1