Exercised The Science of Physical Activity, Rest and Health (Daniel Lieberman) (Z-Library)

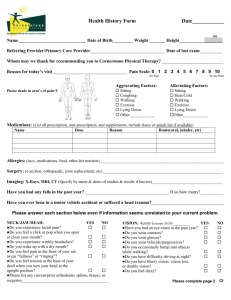

advertisement