Health-promotion-in-health-and-educational-settings-study-report-final

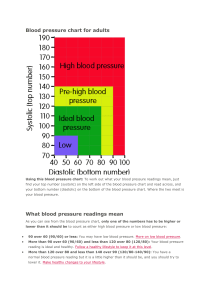

advertisement