EFFECTIVENESS OF EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION ON

KNOWLEDGE ON FEBRILE SEIZURE AMONG THE MOTHERS OF

CHILDREN ATTENDING PRIMARY HEALTH CENTRE, PODANUR.

Mrs. A.S.ARUN SUBINI

Reg. No: 301818401

A Dissertation Submitted to

The Tamil Nadu Dr. M.G.R. Medical University,

Chennai - 32.

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the

Award of the Degree of

MASTER OF SCIENCE IN NURSING

BRANCH-II

PAEDIATRIC NURSING

2020

EFFECTIVENESS OF EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION ON

KNOWLEDGE ON FEBRILE SEIZURE AMONG THE MOTHERS OF

CHILDREN ATTENDING PRIMARY HEALTH CENTRE, PODANUR.

Mrs. A.S.ARUN SUBINI

Reg. No: 301818401

A Dissertation Submitted to

The Tamil Nadu Dr. M.G.R. Medical University,

Chennai – 32.

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the

Award of the Degree of

MASTER OF SCIENCE IN NURSING

BRANCH-II

PAEDIATRIC NURSING

2020

EFFECTIVENESS OF EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION ON

KNOWLEDGE ON FEBRILE SEIZURE AMONG THE MOTHERS OF

CHILDREN ATTENDING PRIMARY HEALTH CENTRE, PODANUR.

BY

Mrs. A.S.ARUN SUBINI

Reg. No: 301818401

A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE TAMILNADU DR.M.G.R. MEDICAL

UNIVERSITY, CHENNAI IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF REQUIREMENT FOR THE

DEGREE OF

MASTER OF SCIENCE IN NURSING

BRANCH-II

PAEDIATRIC NURSING

2020

INTERNAL EXAMINER

EXTERNAL EXAMINER

EFFECTIVENESS OF EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION ON

KNOWLEDGE ON FEBRILE SEIZURE AMONG THE MOTHERS OF

CHILDREN ATTENDING PRIMARY HEALTH CENTRE, PODANUR.

APPROVED BY THE DISSERTATION COMMITTEE

1. RESEARCH GUIDE : …………………………………….

Prof. Dr.D.CHARMINI JEBAPRIYA, M.Sc(N)., M.Phil, Ph.D.,

Principal,

Texcity College of Nursing,

Coimbatore - 23.

2. CLINICAL GUIDE : …………………………………….

Prof.Mrs.THEMOZHI.P, M.Sc (N), M.Sc (Psy), MA Sociology,

Professor cum Vice Principal,

Texcity College of Nursing,

Coimbatore – 23.

3. MEDICAL GUIDE : ……………………………………

Dr. MALLIKAI SELVARAJ, MBBS..DCH. Pgd. DN

Developmental paediatrician,

Royal Care Super Speciality Hospital,

Coimbatore – 18.

CERTIFICATE

Certified that this is the bonafide work of Mrs.A.S.ARUN SUBINI, Texcity College of

Nursing, Coimbatore, submitted as a partial fulfillment of requirement for the Degree of Master

of Science in Nursing to The Tamilnadu Dr.M.G.R.Medical University, Chennai under

Registration No: 301818401

College Seal

Prof. Dr. D. CHARMINI JEBAPRIYA, M.Sc (N)., M.Phil, Ph.D,

Principal,

Texcity College of Nursing,

Coimbatore – 23,

TEXCITY COLLEGE OF NURSING

Podanur Main Road

Coimbatore-23.

2020

DECLARATION

DECLARATION

I hereby declare that the dissertation entitled “A study to evaluate the effectiveness of

educational intervention on knowledge on febrile seizure among the mothers of children

attending Primary Health Centre, Podanur”.

Submitted to the Tamilnadu Dr.M.G.R Medical University, Chennai, in partial fulfillment

of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Science in Nursing is a record of

original research done by myself.

This is the study under the supervision and guidance of Prof. Mrs. THENMOZHI.P

M.Sc (N) Paed. Nsg M.Sc (Psy), MA(Socio), Vice Principal, Texcity College of Nursing,

Coimbatore and dissertation has not found the basis for the award of any degree / diploma /

associated degree / fellowship or similar title to any candidate of any university.

SIGNATURE OF THE PRINCIPAL

SIGNATURE OF THE GUIDE

CANDIDATE

Mrs. A.S.ARUN SUBINI

DEDICATION

THIS DISSERTATION IS

DEDICATED TO

ALMIGHTY GOD

OUR EVER LOVING TEACHERS,

PARENTS, HUSBAND AND FRIENDS

FOR THEIR

“VALUABLE SUPPORT AND

ENCOURAGEMENT”

THROUGHOUT THE STUDY.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The perfection of work and efforts molded by various persons to complete it successfully. It

will not be a fruitful one unless I extend my heartfelt thanks and gratitude to all who guided me

to the treasure of knowledge.

First of all, I would like to convey my sincere gratitude to ALMIGHTY GOD for His

grace, strength and wisdom throughout the completion of the study.

I

would

like

to

extend

my

sincere

thanks

to

Haji.Janab.A.M.M.Khaleel,

Chairman, Texcity Medical and Educational Trust, Coimbatore, for his support and providing

me an opportunity to utilize all the facilities in this esteemed institution for successful

completion of the study.

I express my sincere thanks to Major H.M. Mubarak, Manager, Texcity College of

Nursing, for supporting me to complete this study, as greater achievements comes from

experience and success.

With profound delight, I have immense pleasure to respect and heartfelt gratitude to my

beloved Prof. Dr. Charmini JebaPriya, M.sc (N)., M.Phil., Ph.D The Principal, Texcity

college of nursing, Coimbatore, for her appreciation, support and excellent, guidance

encouragement which enabled me to reach my objective.

With profound pleasure I express my deep sense and sincere heart full gratitude to my

research guide Prof. Mrs. P.Thenmozhi, M.Sc (N),[Paed], MSc (Psy), MA (Socio), Vice

Principal, Department of Child Health Nursing, Texcity college of Nursing, Coimbatore for

all the support rendered to during the endeavor. Her hard work, sincerity, inspiration, suggestion,

illuminating comments and support helped me to mould this study in a successful way. This

study could not have been presented in the manner it has been made and would have never taken

up the shape.

I extend my sincere and deep sense of thanks to Asst Prof. A.Vedha Darly, M.Sc (N),

[MHN], class Co-ordinator Texcity College of Nursing, Coimbatore for her extended

suggestions, constant support, timely help and guidance till the completion of this study.

I express my sincere and deep sense of gratitude to Mrs.Valarmathy, M.Sc(N), [CHN],

who encouraged and guided me to carry out the thesis in a successful manner in a given period.

I would like to extend my thanks to Mrs.Litterishia Balin, M.S.c (N), [MSN]., and

Mrs.Saranya M.Sc (N), [MHN]; Mrs.Akila, M.Sc (N) [OBG], Texcity College of Nursing,

Coimbatore, for their expert guidance, support and valuable suggestion given to me throughout

the study.

I express my sincere thanks to Ms.Delpa Alex, M.Sc (Statistics), Coimbatore for her

necessary guidance in statistical analysis.

I would like to thank all the experts who have done the content validity and contributed

their valuable suggestion in modification of tool even in their busy schedule.

I extend my cordial thanks to my medical guide, Dr. MALLIKAI

SELVARAJ,

MBBS., DCH. Pgd. DN, Developmental pediatrician. Royal Care Super Speciality Hospital,

Coimbatore for permitting me to do the data collection.

I would like to extend my thanks to Mrs.D.Muthumalni Alice, M.A(English)., B.Ed

Professor. Texcity College of Nursing, Coimbatore, for editing and for helping me to achieve

english language appropriateness in my dissertation.

I honestly express my sincere thanks and gratefulness to the mothers of under five children

who participated in my study for their co operation.

I express my heartful thanks to Mrs.Famy Carmel.F, M.Li.Sc, Librarian and

Ms.SUMAYA.A M.Sc (CS) computer staff for her kind cooperation in providing the necessary

materials.

Final and not the least my special thanks goes to my parents Mr.S.Arul peter, N.Suseela

and my husband Mr.M.John Manoj, for sparing their time and providing financial support for

my study.

I would like to extend my thanks to Star Color Park, Gandhipuram, for his full

cooperation and help in bringing in a printed form.

Above all, I express my deep sense of gratitude and indebtedness to our ever loving parents

and family members and friends for rendering emotional support during the hard working period

for preparation of this project.

ABSTRACT

ABSTRACT

The main aim of the present study was “To evaluate the effectiveness of educational intervention

on febrile seizure among the mothers of under five children at Primary Health Center, Podanur”.

OBJECTIVES

To assess the existing level of knowledge and practice on febrile seizure among the

mothers of under five children.

To evaluate the effectiveness of educational intervention on febrile seizure among

mothers of under five children.

To associate the pretest knowledge and practice score with selected demographic

variables.

To identify the Correlation between post test knowledge and practice on febrile seizure

among the mothers of under five children.

HYPOTHESIS

H1- There will be a significant difference between pretest and post test knowledge score on

febrile seizures.

H2- The mean post test practice score will be significantly higher than mean pretest practice

score.

H3- There will be a significant association between pretest scores of knowledge and selected

demographic variables.

H4- There will be a significant association between pretest practice score and selected

demographic variables.

H5- There will be significant relation between the post test knowledge and practice score.

METHODOLOGY

Pre-experimental one group pretest and post test design was used, 40 samples were

selected using non- probability convenient sampling method. A self administered

questionnaire and observational checklist was used to evaluate the knowledge and practice of

mothers. Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyze the data.

RESULTS

The study findings revealed that the educational intervention was effective on knowledge and

practice of mothers in prevention and care of children with febrile seizures.

The findings shows that among 40 mothers of under five children, 36(90%) had moderate

knowledge, 4(10%) had adequate knowledge in the pretest. The level of knowledge was

improved after intervention and in the post test 1(2.5%) had moderate knowledge and

39(97.5%) had adequate knowledge.

The findings shows that among the 40 mothers of under five children, 2 (5%) had

inadequate practice, 28 (70%) had moderate practice, 10 (25%) had adequate practice in

pre test. The level of practice improved after the intervention and in the post test 3 (7.5%)

had moderate practice and 37 (92.5%) had adequate practice.

The findings revealed that, the pretest knowledge score mean was 10.6 and post test mean

was 16.3, So mean difference 5.75 was a true difference. The standard deviation of

pretest was 2.340 and post test was 1.388. The calculated paired ‘t’ value was 24.01 was

highly significant than the table value (2.05) at 0.05 level. Hence the stated hypothesis

was accepted.

The findings revealed that, the pretest practice score mean was 9.10 and post test mean

was 12.77, So mean difference 3.67 was a true difference. The standard deviation of

pretest was 2.08 and posttest was 1.44. The calculated paired ‘t’ value 18.933 was highly

significant than the table value (2.05) at 0.05 level. Hence the stated hypothesis was

accepted.

The findings done by chi square test to find out the association between the pretest

knowledge score with the selected demographic variables, revealed that the pretest

knowledge score is associated with the reason of visit to primary health centre and

χ2value was 8.393 which is significant at level of p<0.05.

The findings revealed by, chi square analyzes to find out the association between the

pretest practice score with the selected demographic variables. The findings revealed that

there was no association between the pretest practice score with the selected demographic

variables.

The findings revealed that there is a positive correlation between the post test knowledge

and post test practice score.

CONTENTs

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER

I

II

CONTENT

INTRODUCTION

PAGE NO

1

1.1

Background of the study

4

1.2

Significance and Need for the study

11

1.3

Statement of the problem

16

1.4

Objectives of the study

16

1.5

Hypothesis

16

1.6

Operational definition

17

1.7

Assumptions

17

1.8

Delimitations

18

1.9

Projected outcome

18

1.10

Conceptual frame work

18

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

2.1

Studies and literature related to febrile seizure in

21

22

children.

2.2

Studies and literature related to educational

26

intervention on febrile seizure.

III

METHODOLOGY

3.1

Research approach

35

3.2

Research design

36

3.3

Research variables

36

3.4

Setting of the study

36

3.5

Population

37

3.6

Samples

37

3.7

Sample size

37

IV

V

VI

VII

3.8

Criteria for selection of samples

37

3.9

Sampling technique

38

3.10

Description of the tool

38

3.11

Scoring procedure

38

3.12

Validity and reliability

39

3.13

Pilot study

40

3.14

Data collection procedure

40

3.15

Plan for data analysis

41

3.16

Ethical considerations

41

DATA ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATIONS

43

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

66

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

6.1

Summary

68

6.2

Objectives

68

6.3

Major findings

69

6.4

Conclusion

71

6.5

Implication

71

REFERENCES

APPENDICES

73

76

LIST OF TABLES

TABLE

NO

TITLE

PAGE

4.1

Frequency and percentage distribution of samples with

demographic variables

45

4.2

Distribution of the samples according to their level of knowledge

in pretest and post test

55

4.3

Distribution of the samples according to their level of practice in

57

pretest and post test

4.4

Mean, Mean difference, Standard deviation and ‘t’ value of

pretest and post test level of knowledge among samples.

59

4.5

Mean, Mean difference, Standard deviation and ‘t’ value of

pretest and post test level of practice among samples.

60

4.6

Frequency, percentage and chi square distribution of pretest level

of knowledge score among mothers of under five children with

the selected demographic variables.

61

4.7

Frequency, percentage and chi square distribution of pretest level

of practice score among mothers of under five children with the

selected demographic variables.

63

4.8

Correlation between post test knowledge and post test practice of

mothers regarding febrile seizure.

65

NO

LIST OF FIQURES

FIQURE

TITLE

PAGE

NO

1.1

Prevalence and cumulative prevalence rates for febrile seizures

2

at different ages.

1.2

Prevalence of febrile seizures in children.

3

1.3

Depicting the causes of febrile seizure.

4

1.4

Recurrence rates of febrile seizures versus sex and the duration

9

after the first seizure.

1.5

Incidence rate of febrile seizures for different ages.

14

1.6

Frequency of consequative episodes of febrile seizure.

14

1.8

Conceptual frame work based on pender’s health promotion

20

model (1996)

3.1

Schematic representation of research methodology

4.1

The percentage distribution of sample in terms of age of the

42

48

mothers.

4.2

The percentage distribution of sample in terms of their

49

educational status.

4.3

The percentage distribution of samples in terms of their

50

occupation.

4.4

The percentage distribution of sample in terms of family history

51

of febrile seizure.

4.5

The percentage distribution of the sample in terms of previous

52

history of febrile seizure.

4.6

The percentage distribution of the sample in terms of reason of

53

visit to primary health center.

4.7

The percentage distribution of the sample in terms of having

thermometer at home.

54

NO

4.8

The percentage distribution of sample in terms of their pretest

56

and post test level of knowledge score.

4.9

The percentage distribution of sample in terms of their pretest

and post test level of practice score.

58

LIST OF APPENDICS

APPENDIX

I

TITLE

Plagirism certificate.

Letter seeking and granting permission to conduct the study.

II

III

IV

Letter requesting expert’s opinion for content validity.

List of experts given opinion for content validity.

Evaluation criteria check list for content validity

V

Tool-I demographic data

Evaluation criteria check list for content validity

VI

Tool-II self administered questionnaire and observational

checklist.

Evaluation criteria check list for content validity.[ Educational

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

Intervention]

Letter seeking consent for participation in this study.

Certificate for English Editing.

Research Tools.

Health teaching plan and module

AV Aids.

CHAPTER - I

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER – I

INTRODUCTION

It‟s health that is real wealth and not pieces of gold and silver

-Mahatma Gandhi

A febrile seizure is a convulsion in a child caused by a spike in body temperature, often

from an infection. They occur in young children with normal development without a history of

neurologic symptoms. Children aged 3 months to 5 or 6 years may have seizures when they have

a high fever.

Febrile seizures are convulsions that can happen when a young child has a fever above

100.4°F (38°C). (Febrile means "feverish.") Febrile seizures (seizures caused by fever) occur in

3 or 4 out of every 100 children between six months and five years of age, but most often around

twelve to eighteen months old.

Children younger than one year at the time of their first simple febrile seizure have

approximate 50 percent chance of having another episode, while children over one year of age

when they have their first seizure have about a 30 percent chance of having a second one.

Nevertheless, only a very small number of children who have febrile seizures will go on to

develop epilepsy.

Alexander KC (2018) stated that febrile seizures are generally defined as seizures occurring

in children typically 6 months to 5 years of age in association with a fever greater than 38°C

(100.4°F), who do not have evidence of an intracranial cause (e.g. infection, head trauma, and

epilepsy).

Medscape (2018) updated pediatric essentials; Pediatric febrile seizures, which represent the

most common childhood seizure disorder, exist only in association with an elevated temperature.

Evidence suggests, however, that they have little connection with cognitive function, so the

prognosis for normal neurologic function is excellent in children with febrile seizures.

1

Diana K. Wells (2018) written that, febrile seizures usually occur in young children who are

between the ages of 3 months to 3 years. They‘re convulsions a child can have during a very

high fever that‘s usually over 102.2 to 104°F (39 to 40°C) or higher. This fever will happen

rapidly. The rapid change in temperature is more of a factor than how high the fever gets for

triggering a seizure. They usually happen when your child has an illness. Febrile seizures are

most common between the ages of 12 and 18 months of age. There are two types of febrile

seizures: simple and complex. Complex febrile seizures last longer. Simple febrile seizures are

more common.

John J Millichap (2019) revealed that febrile seizures are convulsions that occur in a child

who is between six months and five years of age and has a temperature greater than 100.4ºF

(38ºC). The majority of febrile seizures occur in children between 12 and 18 months of age.

Febrile seizures occur in 2 to 4 percent of children younger than five years old. They can be

frightening to watch, but do not cause brain damage or affect intelligence. Having a febrile

seizure does not mean that a child has epilepsy; epilepsy is defined as having two or more

seizures without fever present.

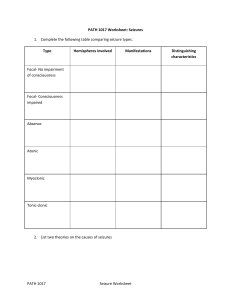

Fig:1.1

Prevalence and cumulative prevalence rates (reported as percentages) for

febrile seizures at different ages. The prevalence peaked (at 27.5%) among

those aged 2 years (age range 18-30 months).

2

National institute of health (2020) modified, febrile seizures are seizures or convulsions

that occur in young children and are triggered by fever. Young children between the ages of

about 6 months and 5 years old are the most likely to experience febrile seizures; this risk peaks

during the second year of life. The fever may accompany common childhood illnesses such as a

cold, the flu, or an ear infection. In some cases, a child may not have a fever at the time of the

seizure but will develop one a few hours later.

The vast majority of febrile seizures are convulsions. Most often during a febrile seizure, a

child will lose consciousness and both arms and legs will shake uncontrollably. Less common

symptoms include eye rolling, rigid (stiff) limbs, or twitching on only one side or a portion of the

body, such as an arm or a leg. Sometimes during a febrile seizure, a child may lose

consciousness but will not noticeably shake or move.

Fig:1.2 Prevalence of febrile seizures in children younger than 5 years in Korea

during 2009-2013.

3

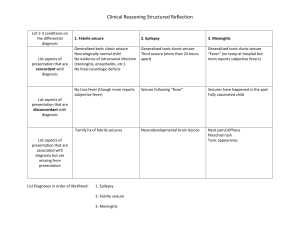

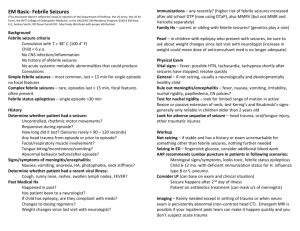

causes of febrile seizure

45

40%

40

35

28%

PERCENTAGE

30

RESP.TRACT.INF

24%

25

CNS Inf

20

UTI

15

Others

10

8%

5

0

RESP.TRACT.INF

CNS Inf

UTI

Others

Fig 1.3: Depicting the causes of febrile seizure

Most febrile seizures last only a few minutes and are accompanied by a fever above 101°F

(38.3°C). Although they can be frightening for parents, brief febrile seizures (less than 15

minutes) do not cause any long-term health problems. Having a febrile seizure does not mean a

child has epilepsy, since that disorder is characterized by reoccurring seizures that are not

triggered by fever. Even prolonged seizures (lasting more 15 minutes) generally have a good

outcome but carry an increased risk of developing epilepsy.

1.1 BACK GROUND OF THE STUDY

Children comprise one third of our population and all of our future and their health is our

foundation. The childhood period is also a vital period because many of the health problems will

arise from this period and most of the studies reveal that many children are suffering from one or

the other disease. Our responsibility is to maintain certain specific biological and psychological

4

needs to ensure the survival and healthy development of the child, future adult and also to

maintain optimum health of the children to enjoy their childhood. But unfortunately children are

at risk of diseases, the reason may be many. One of such disease is febrile seizure which

threatens life of the child.

Hackett R (2011) conducted a study one thousand four hundred and three children

participated in a home-based survey of psychiatric disorders in 8- to 12-year-old children in

Calicut District, Kerala, India. One thousand one hundred and ninety-two consecutive children

underwent neurological and psychometric assessments. The projected number of children with a

history of febrile seizures was 120 giving a lifetime incidence of 10.1%. Recurrent febrille

seizures predominated and these were strongly associated with a history of perinatal adversity.

Febrile seizures were independently association with indices of infective illness and mothers'

education. Epilepsy developed in 2.7% of children with febrile seizures, but no evidence was

found that febrile seizures had adverse intellectual or behavioural sequelae.

Srinivas.M (2011) found out that febrile seizures are defined as ―an event in neurologically

healthy infants and children between 6 months and 5 years of age, associated with fever >38ºC

rectal temperature but without evidence of intracranial infection as a defined cause and with no

history of prior afebrile seizures. Febrile seizures are to be distinguished from epilepsy which is

characterized by recurrent non febrile seizures. All seizures with fever are not febrile seizures.

Generally, febrile seizures occur during early phase of rising temperature and are uncommon

after 24 hours of onset of fever.

National Survey (2011) found out the Prevalence of febrile seizure in the countries are,

India it is 360/100,000,in Japan it is 89/1000 in children younger than 13 years, in Peru it is

2016/100,000 in children younger than 15 years and 10.1% is estimated to be life time

prevalence of febrile convulsion in India. Iranian journal of public health says that in a study the

life time prevalence of febrile convulsion was 32/1000 population, approximately 60% of case

reported febrile convulsion as the presumptive cause.

Manikam K (2011) conducted a cross sectional study in Andhra Pradesh showed that the

prevalence

rate

of

epilepsy as

6.2/1000

population,

where

as

in

Kerala

it

is

4.9/1000population.School age children are most affected with a slight male preponderance. In

5

America 300,000 people have a first convulsion each year and 120,000 of them are under the age

of eighteen.

Child Welfare Report (2011) elated that discrimination against persons suffering from

febrile seizure is common. This is often due to sudden falls and convulsive episodes at

unexpected times in public places 6resulting in rejection. Sometimes, the social discrimination

against these persons with epilepsy may be more devastating than the disease itself. Children

with epilepsy may be rejected from their classes because of frequent seizures which makes their

teachers and fellow students uncomfortable with their presence in class. Also, some children are

not allowed in schools once the school authority become aware that the child has epilepsy.

World Health Organization (2012) stated that febrile seizures (FS) are common, with a life

time prevalence of 2-6%. The definition of FS is controversial. The International League against

Epilepsy (ILAE) defines FS as ―an epileptic seizure occurring in childhood associated with fever,

but without evidence of intracranial infection or defined cause. Seizures with fever in children

who have experienced a previous non-febrile seizure are excluded (ILAE, 1993). British

Pediatric Association suggested "an epileptic seizure occurring in a child aged from six months

to five years, precipitated by fever arising from infection outside the nervous system in a child

who is otherwise neurologically normal‖ (Joint Working Group of the Research Unit of the

Royal College of Physicians and British Pediatric Association, 1991). Although it is important to

distinguish "seizures with fever" and "febrile seizures" in terms of management and prognosis,

this is often not possible in many primary health facilities in resource poor countries (Joint

Working Group of the Research Unit of the Royal College of Physicians and British Pediatric

Association, 1991). Seizures with fever include any seizure in a child of any age with fever of

any cause.

World Health Organization (2012) revealed that febrile Seizure is a common neurological

problem in children. Many seizures disorders have their origin in childhood. Nearly two-third of

febrile seizure disorder can be treated easily by them without the need for the specialist. In

ancient times convulsions are considered as curse of evils. Today also people with seizure

disorders are facing superstitions to this disease, this attitude can be changed once the scientific

cause of this condition is defined and the public is aware through education.

6

Fernandocendes (2012) pointed that febrile seizure promotes temporal lobe epilepsy

through the retrospective study: The sequence of febrile seizures followed by intractable

temporal lobe epilepsy is rarely seen from a population perspective. There is a significant

relationship between a history of prolonged febrile seizures in early childhood and mesial

temporal sclerosis. This association results from complex interactions among several genetic and

environmental factors. Early febrile seizure damages the hippocampus, and therefore the child

has a prolonged febrile seizure because the hippocampus was previously damaged. A

retrospective study of a series of 167 consecutive patients with lesional epilepsy supports the

concept of prolonged febrile seizure leading to mesial temporal sclerosis in a predisposed

hippocampus. In the study, febrile seizures were recurrent in five patients: three had simple and

two had complex febrile seizures. There is a strong correlation between mesial temporal sclerosis

and the severity of the epilepsy. Although there is a high incidence of complex febrile seizures

among patients with mesial temporal sclerosis, it is still not clear whether complex febrile

seizures are an epiphenomenon or a causative factor.

Peter Camfield (2012) conducted a study on Antecedents and Risk Factors for Febrile

Seizures; One child in 28 will have a febrile seizure. It would be an enormous clinical boon to be

able to predict accurately which child would develop febrile seizures so that parents could be

counseled and potentially preventive treatment could be offered. There are a significant number

of independent risk factors, such as day-care attendance, parental education, prenatal maternal

smoking, maternal alcohol intake, late neonatal discharge, slow development, degree of fever,

gastroenteritis, and family history of febrile seizures. In a study described in the chapter, an

interview with 13,135 parents who gave birth to children in the same week revealed that 303

children were known to have had at least one febrile seizure. The effect of low birth weight

seemed to be the result of a brain injury from complications of prematurity or premature birth in

children with existing brain abnormalities. The strongest association with febrile seizures is a

history of febrile seizures in the mother. Risk factors provide an insight into the pathophysiology

of febrile seizures, which will eventually yield all the secrets of this common and frightening

disorder.

Carl E.Stafstrom (2012) said that nearly every article or text written about febrile seizures

contains a statement about febrile seizures being the most common type of seizure in childhood,

7

occurring in 2–5% of children. The prognosis of febrile seizures in the early literature was fairly

pessimistic because of the inclusion of symptomatic causes of seizure other than fever and

patient selection bias. The consensus that febrile seizures do not constitute a form of epilepsy is

an important conceptual advance with relevance to the consideration of febrile seizure incidence

and prevalence. A disproportionate number of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy have febrile

seizures as young children. According to the International League, febrile seizures are an acute,

symptomatic type—that is, a ―special,‖ situation-related—seizure. Febrile seizures are not

associated with a structural or developmental anomaly of brain, though the existence of such

pathology may enhance the susceptibility to febrile seizures. The majority of febrile seizures

occurs between 6 months and 3 years of age, with the peak incidence at about 18 months. The

data obtained from epidemiological studies can help in the understanding of the genetics and

prognosis of febrile seizures.

Wongs (2013) pointed out another treatment option for seizure is surgical removal of the

brain tissue where the seizures originate (i.e., temporal lobectomy) but this technique is not often

used in children. Another possible preventive measure for epilepsy in children is avoidance of

triggers for seizures. Many children with epilepsy have triggers for seizures such as foods,

scents, or other environmental factors. If these triggers can be identified, seizures may be more

easily controlled. When used in some combination, all of these treatment methods have shown

effectiveness, however, there are few treatments that keep individuals entirely seizure free.

Ali Delpisheh (2014) said febrile seizures are the most common neurological disorder

observed in the pediatric age group. The present study provides information about

epidemiological and clinical characteristics as well as risk factors associated with FS among

Iranian children. On the computerized literature valid databases, the FS prevalence and 95%

confidence intervals were calculated using a random effects model. A meta regression analysis

was introduced to explore heterogeneity between studies. The important viral or bacterial

infection causes of FSs were; recent upper respiratory infection 42.3% (95% CI: 37.2%–47.4%),

gastroenteritis21.5% (95% CI: 13.6%–29.4%), and otitis media infections15.2% (95% CI: 9.8%20.7%) respectively. The pooled prevalence rate of FS among other childhood convulsions was

47.9% (95% CI: 38.8–59.9%). The meta–regression analysis showed that the sample size does

not significantly affect heterogeneity for the factor ‗prevalence FS‘.

8

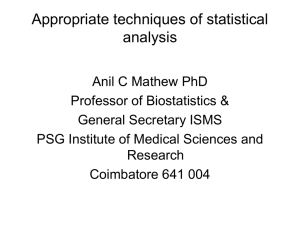

Fig:1.4

Recurrence rates of febrile seizures versus sex and the duration after the first

seizure. The recurrence rate was more than halved in patients with no

recurrence for 6 months after the first seizure.

Hocken Berry and Wilson (2015) stated that Febrile seizure management techniques

include the use of deep brain stimulators and vagus nerve stimulators. Deep brain stimulators are

implanted within the brain and send impulses to the cerebellum to increase seizure control by

stimulating deep brain structures, while vagus nerve stimulators are implanted near the clavicle

and send an electrical impulse to stimulate the vagus nerve in the neck.

Subramaniyam (2016) revealed that there is a dramatic global disparity in the care of febrile

seizure between high and low income countries and in rural and urban setting. The burden of

epilepsy in developing countries has become obvious as nearly 75% of people with epilepsy

were residing in these countries, where the diagnostic and therapeutic facilities are poor. A large

proportion of patients with epilepsy do not get treatment because medical facilities are not

available or approachable to them. In many of the cases it was found that the people are unaware

regarding the care of febrile seizure.

9

Dr. Bhattia (2017) conducted two community based studies in India (both rural and urban)

showed that the prevalence rate of febrile seizure stands around 5/1000 population (at this rate

present estimate of total epileptics in this country is about 5 million) and incidence rate varies

from 38 to 49.3 per 100,000 population per year. Treatment gap, which is a measure of per cent

of patient populations not receiving the treatment, was estimated to be up to 73.7% to 78% in

India. In 2/3 of cases etiology was unknown. Hot water epilepsy is unique in South India and

single solitary ring enhancing lesion in brain imaging is a common feature in Indian

subcontinent.

Dutta (2018) stated that febrile Seizures are caused by malfunctions of the brain‘s electrical

system that results from cortical neuronal discharge. The manifestations of seizures are

determined by the site of origin and may include altered consciousness, involuntary 2

movements, changes in perception, behaviours, sensation and posture. A diagnosis of epilepsy is

made when a person has three or more seizures. A seizure is behaviorally characterized by an

abrupt unconscious change in behaviour, movement, autonomic function, or sensation.

Henry (2018) stated that febrile seizures are the most common pediatric neurologic disorder.

Four per cent to ten per cent of children suffer at least one febrile seizure in the first 3 years of

life. The incidence is highest in children less than 6 years of age, with a decreasing frequency in

older children.

Febrile Seizures associated with fever occur in one in every 30-50 children, and those

unassociated with fever occur in about 1/200 children. About 5% of children experience one or

more seizures before they reach adulthood. Febrile Seizures activity often involves the diagnosis

of potential for injury, both physical& psychosocial. A potential for injury can be minimized

with first aid measures. Thus school teachers should possess skills in observational assessment

and first aid.

World Health Organization report suggested that even though the febrile seizure are

managed with the help of technology in present era people who are staying at rural and remote

areas of developing countries are not accessible or approachable to them. People in the

developing countries like India, Pakistan and Bangladesh believe that febrile seizure is one of the

diseases caused due to mistakes done in the past life. It is also concluded from various studies

10

that, false belief have major implication regarding epilepsy in illiterate as well as in the minds of

the people from these countries.

The disease enrobed in superstition, discrimination, and stigma. There is a clear cut lack of

information programmes in the developing world about febrile seizure and its management. The

febrile seizure has an impact on many aspects of a child‘s development and functioning. As a

result many of these children are at risk for unsuccessful school experiences, difficulties in social

engagement with peers, inadequate social skills and poor self-esteem.

Many of the parents were not familiar with the initial procedures in attending a child during

febrile seizure. The initial procedures adopted by some parents were inappropriate, like to

pulling the tongue or to putting objects in the child's mouth. Some of these wrong procedures,

which are potentially harmful, are mainly related to mythical concepts. As the parents are always

in touch with febrile seizure children, public enlightenment program on health issues especially

recognition and management of febrile seizure must be created in order to ensure that people

have sufficient knowledge about this disease. This will helps to improve the quality of life of

children with febrile seizure.

1.2 SIGNIFICANCE AND NEED FOR THE STUDY

Becker (2011) revealed that febrile seizure affects all age groups, but for children a variety

of issues exists that can affect one‘s childhood. Some epilepsy ends after childhood, some forms

of epilepsy are associated only with conditions of childhood that cease once a child grows up.

Approximately 70%of children who suffer epilepsy during their childhood eventually outgrow.

There are also some seizures, such as febrile seizures, that have one-time occurrence during

childhood and do not result in permanent febrile seizure. The worldwide prevalence of active

febrile seizure is between four and ten per thousand populations. Epidemiologic studies of febrile

seizure have done much to define the frequency of seizures and seizure disorders in the

population and to provide a far more accurate understanding of prognosis. Although the majority

of individuals with febrile seizure do very well with respect to seizure control, they still face

many challenges in everyday life. A recent meta-analysis of published and unpublished studies

puts the overall prevalence rate of febrile seizure in India as 5.59 per 1,000 populations, with no

statistically different rates between men and women or urban and rural residence. Based on the

11

total projected population of India in 2001 the estimated number of people with epilepsy is 5.5

million.

Midhun Lal (2011) conducted a population based cohort study was conducted to examine the

effect of pregnancy and neonatal factors on the subsequent development of childhood febrile

seizure in Nova Scotia, Canada were followed up to December 2001. Data on pregnancy and

neonatal events and on diagnosis of childhood febrile seizure were obtained through record

linkage of 2 population based databases; the Nova Scotia Atlee Perinatal Database and the

Canadian febrile seizure Database and Registry. Factors analysed included events during the

prenatal, labor and delivery, and neonatal time periods. Cox proportional hazards regression

models were used to estimate relative risks at 95 per cent confidence interval. There were 648

new cases of febrile seizure diagnosed among 124,207 live births, for an overall rate of 63 per

100,000 persons. Incidence rates were highest among children <1 year of age.

Bahadhoor (2011) done a home based survey was done on psychiatric disorders in 8 to12

year old children in Calicut District, Kerala, India. One thousand one hundred and ninety-two

consecutive children underwent neurological and psychometric assessments. The projected

number of children with a history of febrile seizures was 120 giving a lifetime incidence of

(10.1%). Recurrent febrile seizures predominated and these were strongly associated with a

history of perinatal adversity. Febrile seizures were 9 independently associated with indices of

infective illness and mother‘s education. Epilepsy developed in (2.7%) of children with febrile

seizures.

Journal of Pediatrics (2012) the article on advances in febrile seizure states that the

prevalence rate of febrile seizure in countries of Asia was (4.4), Japan (1.7), Pakistan (4.7),

Kashmir in India (2.4), Srilanka (9.0) and Guan (4.9) million. This prevalence rate indicates that

prevalence of febrile seizure in Asian countries is comparatively higher than the prevalence in

the world.

Daisy (2012) said that in India, there are 30 million people affected by febrile seizure in 2004.

About one in two hundred school children are affected with febrile seizure, about one person in

twenty has a seizure of some type during life, and in the population at large about one in 200 has

febrile seizure. Most of those who develop idiopathic febrile seizure do so before the age of 20

12

years. The general systemic conditions in which seizures most commonly occur in children is

due to hypoxia or high fever. As the understanding of its physical and social burden has

increased, it has moved higher up in the world health agenda. 8 Seizure disorders are more

common among children between 6 months of age and 15 years and in new-born period. It has

been estimated that about 4 to 6% of all children will have fits during their lifetime and 90% of

convulsive disorders have their onset in early life. One in 15 or 20 children admitted in hospitals

give a history of convulsion.

Jung Hye Byeon (2018) published Febrile seizures are the most common type of seizure

during childhood, reportedly occurring in 2–5% of children aged 6 months to 5 years. However,

there are no national data on the prevalence of FS in Korea. This study determined the

prevalence, incidence, and recurrence rates of FS in Korean children using national registry data.

Methods The data were collected from the Korea National Health Insurance Review and

Assessment Service for 2009–2013. Patients with febrile convulsion as their main diagnosis were

enrolled. The overall prevalence of FS in more than 2 million children younger than 5 years was

estimated, and the incidence and recurrence rates of FS were determined for children born in

2009. Results The average prevalence of FS in children younger than 5 years based on hospital

visit rates in Korea was 6.92% (7.67% for boys and 6.12% for girls). The prevalence peaked in

the second to third years of life, at 27.51%. The incidence of FS in children younger than 5 years

(mean 4.5 years) was 5.49% (5.89% for boys and 5.06% for girls). The risk of first FS was

highest in the second year of life. The overall recurrence rate was 13.04% (13.81% for boys and

12.09% for girls), and a third episode of FS occurred in 3.35%. Conclusions Our study

determined the overall prevalence of FS using data for the total population in Korea. The

prevalence was comparable to that reported for other countries. Patients with three episodes of

FS need to be monitored carefully.

Many parents still have a negative attitude about febrile seizure. Some of them feel it is

contagious. Hence during the episodes of seizures the children are not given any assistance or

care. The availability of antiepileptic drugs and the prolonged medical care needed by children

with febrile seizure justify the careful planning of a social program.

13

Fig:1.5

Incidence rate of febrile seizures for different ages. The cumulative incidence

rate was 5.49% among those aged 4 years (age range 42-54 months).

Fig:1.6

Frequencies of first, second, and third episodes of FS. The recurrence rates

of FS (second and third episodes of FS) were highest among those aged 3

years (age range 30-42 months). FS: febrile seizures.

14

It is also found that society‘s misconceptions have a major impact on peoples view

towards febrile seizure and its management in rural areas in various parts of the country. Parental

fear of convulsion is the major problem with serious negative consequences in their daily life. In

early times people believed febrile seizure as a divine origin and were called the sacred disease

because someone with epilepsy was thought to be ―seized‖. Majority of mothers have false belief

about febrile seizure and they have different knowledge, attitude and practices especially in low

socio-economic families. Global campaign against febrile seizure in Senegal, Zimbabwe and

Argentina showed that the training and education programmes of parents of children suffering

with febrile seizure effective and disseminating the knowledge regarding febrile seizure.

The parents should involve themselves in matters concerning their Childs febrile seizure.

It is important to involve the siblings of the febrile seizure, child helps to develop better

understanding of condition as they may have all kinds of fears and misinformation about the

disease. In many families, the mother tends to come closer to the situation. Often, she is the

parent who visits the doctor, or meets the teacher or 10 talks to other parents at the local level.

As she learns more about the febrile seizure, it becomes much easier to adjust with the idea of

having a child with febrile seizure.

Febrile seizure children express anxiety and embarrassment and see themselves as being

different and inferior. A thorough evaluation of the patient‘s attitude and expectations

concerning health maintenance is essential. The attitude and expectations of family members

should also be evaluated since their understanding and support is crucial to the patient‘s ability to

adjust to his condition. It is important for the nurse to be aware of potential prejudices which

may be encountered by the client and his family.

During the clinical posting the investigator noticed that during the year of 2015 there

were 184 admissions of children with seizure disorders, 253 cases of febrile seizures and 63

cases of convulsions of new-born. The mothers of children were anxious about the disease

condition and also they had many doubts regarding the etiology, risk factors and both medical

and home management of children with seizure disorder. It is very important to adhere with

therapeutic regimen and the care giver should reinforce to avoid skipping of antiepileptic drugs.

It is also important to give attention to the emotional aspect of the child. So it is found that a

15

structured Teaching Programme will be a guide for mothers regarding management of febrile

seizure at home.

1.3 STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

―Evaluate the effectiveness of educational intervention on febrile seizure among the

mothers of under five children at Primary Health Center Podanur.

1.4 OBJECTIVES

To assess the existing level of knowledge and practice on febrile seizure among the

mothers of under five children.

To evaluate the effectiveness of educational intervention on febrile seizure among

mothers of under five children.

To associate the pretest knowledge and practice score with selected demographic

variables.

To identify the correlation between post test knowledge and practice on febrile seizure

among the mothers of under five children.

1.5 HYPOTHESIS

H1- There will be a significant difference between pretest and post test knowledge score on

febrile seizures.

H2- The mean post test practice score will be significantly higher than mean pretest practice

score.

H3- There will be a significant association between pretest scores of knowledge and selected

demographic variables.

H4- There will be a significant association between pretest practice score and selected

demographic variables.

H5- There will be significant relation between the post test knowledge and practice score.

16

1.6 OPERATIONAL DEFINITIONS

•

Evaluate: It means judgment of the value of that which is being assessed. In this study, it

means judging the effectiveness of learning package regarding febrile seizure.

•

Effectiveness: It refers to the extent of which the learning package on febrile seizure

gives the desired effect in improving knowledge of mothers attending in Primary Health

Center, Podanur.

•

Educational Intervention: It is a teaching module developed by the researcher to impart

knowledge on febrile seizure. In this study it is referred as organized content with

relevant audio visual aids to provide information on febrile seizure among mothers of

children.

•

Knowledge: It refers to the response received from the mothers regarding febrile seizures

in their children as measured by a structured knowledge questionnaire.

•

Practice: It refers to the activities reported by mothers in relation to prevention,

compliance with therapeutic regimen, and management of child with febrile seizure as

measured by checklist.

•

Mothers: It refers a mothers of under five children attending primary health center,

podanur.

•

Febrile Seizure: A febrile seizure is a convulsion in a child caused by a 100.4˚f in body

temperature, often from an infection.

1.7 ASSUMPTIONS

This study assumes that, knowledge is the basis of practice

Parents of children may have inadequate knowledge regarding febrile seizure.

Educational intervention is interactive and effective way to gain knowledge regarding

febrile seizure and related health problems.

17

1.8 DELIMITATIONS

The study is limited to

Mothers of children attending Primary Health Center, Podanur.

Sample size is 40.

Data collection period is limited to 4 weeks.

Educational intervention will be evaluated by self administered questionnaire.

1.9 PROJECTED OUTCOME

This study will help to evaluate the level of knowledge regarding febrile seizure.

This study will help the mothers of children to gain knowledge regarding febrile

seizure.

The study will help to prevent complications of febrile seizure such as impaired

growth and development.

1.10 CONCEPTUAL FRAME WORK

Based on the Nola J. Pender (1996)

Health promotion model was designed to be a ―Complementary counterpart to models of health

protection‖. The health promotion model describes the multi dimensional nature of persons as

they interact with in their environment to pursue health.

It defines ―Health as a ―positive dynamic state not merely the absence of disease‖.

This model focuses on following three areas:

Individual characteristics and experiences.

Behavioral specific cognition and affect.

Behavioral out comes.

Individual characteristics and experience:- The health promotions model notes that each

person has unique personal characteristics and experience that affect subsequent action. In this

study we are focusing the factors influencing the mother and child on biological, psychological,

and socio cultural.

18

Behavioral specific cognition and affect:- The set of variables for specific knowledge and

affect have important significance. In this we evaluate the specific cognition and affects related

to febrile seizure.

Behavioral outcomes:- It is the end point. In this we are evaluating the mothers health promoted

behaviours through post test questionnaires on prevention of febrile seizure.

19

Individual characteristics and

experience

Behaviour specific cognitive and

affect

Behaviour outcome

Perceived benefits of action

Pre test

Prior related behavior

Mothers may have inadequate

knowledge

and

practice

on

prevention and care during febrile

seizure.

Intervention

Perceived barrier to action

Inadequate exposure to health

education related to prevention and

care of children during febrile seizure

Perceived self efficacy

Personal Factors

Biological factors; Age, Sex, type of

family.

Immediate competing demands

and preference

Mothers of children will be able to

gain adequate knowledge on febrile

seizure

Mothers of children are able to

execute health promotion behavior

related to febrile seizure

Psychological factors; knowledge,

beliefs, Personal norms.

Teaching programme related affect

Socio-cultural factors Consists of

occupational status, family income,

educational status.

By

administering

the

educational

intervention mothers of children will gain

adequate knowledge regarding febrile

seizure.

Low control : environmental factors:age, sex, religion, type of family, bread

winner, food habits.

High control: education, monthly

income

Post test

Commitment to a

plan action

Implementation of

educational intervention

on prevention of febrile

seizure group with the

duration of 60 Minutes.

Health Promotion behaviour

Accomplishing of health promotion

behavior on knowledge regarding

prevention of febrile seizures

Prevent the febrile seizure for children

and care of childhood febrile seizure.

Encourage the children to take healthy

foods like milk, cereals, pulses eggs,

fish, etc.. and prevent the infections.

Interpersonal Influences

Encouragement and support from primary

health care personnel, mothers and children

Inadequate

knowledge

Situational influences

Favorable family and Primary Health

Center environment

Moderately

adequate

knowledge

Adequate

knowledge

FEED BACK

Figure 1.8 Conceptual frame work based on modified Pender‟s Health Promotion Model (1996)

20

CHAPTER - II

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

CHAPTER - II

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

“Every moment is an experience” - Jake Roberts

INTRODUCTION

Review of literature is a broad systematic and critical collection and evaluation of

important scholarly published literature as well as unpublished materials. The review serves as

an essential background for any research. The review of literature is essential to all steps of the

research process. It is an account of what is already known about a particular phenomenon. The

main purpose of literature review is to convey to the reader about the work already done and the

knowledge and ideas that have been already established on a particular topic of research. From

this prospective the review is based on broad, systemic and critical collection and evaluation of

the important published scholarly literature and unpublished research findings, critically reading

the literature is to develop a sound study that contribute to development of knowledge in the

aspect of theory, research, evaluation and practice.

According to Polit and Hungler (2010) review of literature is a critical summary of

research on a topic of interest generally prepared to put a research problem in context to identify

gaps in prior studies to justify a new investigation.

According to Suresh.K.Sharma (2013) literature review is defined as a broad,

comprehensive, in depth, systematic and critical review of scholarly publication, unpublished

printed or audio visual materials and personal communication.

THE LITERATURE WAS REVIEWED AND PRESENTED UNDER THE FOLLOWING

SECTIONS

Section-I: Studies and literature related to febrile seizure in children

Section-II: Studies and literature related to educational intervention on febrile seizure

21

SECTION-I: STUDIES AND LITERATURE RELATED TO FEBRILE SEIZURE IN

CHILDREN

European Journal of Pediatrics (2011) modified and published assessment of febrile

seizure in children; Febrile seizures are the most common form of childhood seizures, affecting

2-5% of all children and usually appearing between 3 months and 5 years of age. Despite its

predominantly benign nature, a febrile seizure (FS) is a terrifying experience for most parents.

The condition is perhaps one of the most prevalent causes of admittance to pediatric emergency

wards worldwide. The risk of epilepsy following FS is 1-6%. The association, however small,

between febrile seizure and epilepsy may demonstrate a genetic link between febrile seizure and

epilepsy rather than a cause and effect relationship. The effectiveness of prophylactic treatment

with medication remains controversial. There is no evidence of the effectiveness of antipyretics

in preventing future febrile seizure. Prophylactic use of paracetamol, ibuprofen or a combination

of both in febrile seizure, is thus a questionable practice. There is reason to believe that children

who have experienced a simple febrile seizure are over-investigated and over-treated. This

review aims to provide physicians with adequate knowledge to make rational assessments of

children with febrile seizures.

Lalith. K (2011) conducted a prospective study which carried out in a tertiary hospital to

evaluate the knowledge and attitudes of parents toward children with febrile seizure.

Questionnaires were administered to all the parents who attended the hospital with their children

diagnosed of febrile seizure. Two hundred and eighty parents whose children suffered from

febrile seizure participated in the study. The investigator concluded that more than 90% of

parents and caregivers know about febrile seizures. There is a need to disseminate more

information to the public about 22 its causes, clinical manifestation, approach to managing a

convulsing child, and its outcome and periodic medical campaigns aimed at educating the public

about febrile seizure through the media could go a long way in reducing the morbidity and

mortality associated with this disorder.

Misle. K. et.al., (2012) anthropological study was conducted to analyse current parental

perceptions of febrile seizures in order to improve the quality of management, care, and

explanations provided to families at paediatric emergency unit. Investigators analysed

22

interviews of 37 parents, whose child was admitted to the paediatric emergency unit due to a first

seizure. The parental experience of the crisis was marked by upsetting memories of a "scary"looking body and the perception of imminent death. The meaning attributed by parents to the

word "seizure" and "epilepsy" usually referred to an exact clinical description of the

phenomenon, but many admitted being unfamiliar with the term or at least its origin.

Understanding and integrating these parental interpretations seems essential to improving care

for families who first experience this symptom.

Reese C. Graves (2012) published febrile seizures; risk, evaluation and prognosis for that

Febrile seizures are common in the first five years of life, and many factors that increase seizure

risk have been identified. Initial evaluation should determine whether features of a complex

seizure are present and identify the source of fever. Routine blood tests, neuro imaging, and

electroencephalography are not recommended, and lumbar puncture is no longer recommended

in patients with uncomplicated febrile seizures. In the unusual case of febrile status epilepticus,

intravenous lorazepam and buccal midazolam are first-line agents. After an initial febrile seizure,

physicians should reassure parents about the low risk of long-term effects, including neurologic

sequelae, epilepsy, and death. However, there is a 15 to 70 percent risk of recurrence in the first

two years after an initial febrile seizure. This risk is increased in patients younger than 18 months

and those with a lower fever, short duration of fever before seizure onset, or a family history of

febrile seizures. Continuous or intermittent antiepileptic or antipyretic medication is not

recommended for the prevention of recurrent febrile seizures.

Joshua R. Francis. (2016) conducted an observational study of febrile seizures: the

importance of viral infection and immunization, Children aged 6 months to 5 years presenting to

the Emergency Department of a tertiary children‘s hospital in Western Australia with febrile

seizures were enrolled between March 2012 and October 2013. Demographic, clinical data and

vaccination history were collected, and virological testing was performed on per-nasal and perrectal samples. The result was one hundred fifty one patients (72 female; median age 1.7y; range

6 m-4y9m) were enrolled. Virological testing was completed for 143/151 (95%). At least one

virus was detected in 102/143 patients (71%). The most commonly identified were rhinoviruses

(31/143, 22%), adenovirus (30/151, 21%), entero viruses, (28/143, 20%), influenza (19/143,

13%) and HHV6 (17/143, 12%). More than one virus was found in 48/143 (34%). No significant

23

clinical differences were observed when children with a pathogen identified were compared with

those with no pathogen detected. Febrile seizures occurred within 14 days of vaccine

administration in 16/151 (11%). At least one virus was detected in over two thirds of cases tested

(commonly picorna viruses, adenovirus and influenza). Viral co-infections were frequently

identified. Febrile seizures occurred infrequently following immunization.

Alexander KC Leung (2018) published febrile seizure overview; To provide an update on

the current understanding, evaluation, and management of febrile seizures. In that results ,

Febrile seizures, with a peak incidence between 12 and 18 months of age, likely result from a

vulnerability of the developing central nervous system to the effects of fever, in combination

with an underlying genetic predisposition and environmental factors. The majority of febrile

seizures occur within 24 hours of the onset of the fever. Febrile seizures can be simple or

complex. Clinical judgment based on variable presentations must direct the diagnostic studies

which are usually not necessary in the majority of cases. A lumbar puncture should be

considered in children younger than 12 months of age or with suspected meningitis. Children

with complex febrile seizures are at risk of subsequent epilepsy. Approximately 30–40% of

children with a febrile seizure will have a recurrence during early childhood. The prognosis is

favorable as the condition is usually benign and self-limiting. Intervention to stop the seizure

often is unnecessary.

J.Clin Neurol (2018) conducted a study which determined the prevalence, incidence, and

recurrence rates of FS in Korean children using national registry data. The data were collected

from the Korea National Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service for 2009–2013.

Children with febrile convulsion as their main diagnosis were enrolled. The overall prevalence of

FS in more than 2 million children younger than 5 years was estimated, and the incidence and

recurrence rates of FS were determined for children born in 2009. Results of the average

prevalence of febrile seizure in children younger than 5 years based on hospital visit rates in

Korea was 6.92% (7.67% for boys and 6.12% for girls). The prevalence peaked in the second to

third years of life, at 27.51%. The incidence of FS in children younger than 5 years (mean 4.5

years) was 5.49% (5.89% for boys and 5.06% for girls). The risk of first FS was highest in the

second year of life. The overall recurrence rate was 13.04% (13.81% for boys and 12.09% for

girls), and a third episode of febrile seizure occurred in 3.35%. Our study determined the overall

24

prevalence of febrile seizure using data for the total population in Korea. The prevalence was

comparable to that reported for other countries. Children with three episodes of febrile seizure

need to be monitored carefully.

Dr. Nurun Nahar (2019) conducted a study on clinical aspects of febrile seizures,

knowledge, attitude, practice and its impact in admitted children and Socio-demographic

characteristics of the parents; febrile seizures are common and mostly benign. They are the most

common cause of seizures in children less than five years of age. There are two categories of

febrile seizures, simple and complex. 116 Children‘s with FS were listed within the study WHO

(World Health Origination) were aged matched to four controls to work out risk factors for a

primary febrile seizure. The mean (±SD) age of youngsters underneath the study was 22.4± 14.3

months. 63 (54.3%) of the Children‘s were aged 18 months and below, mean (±SD) age of onset

of seizures was 16.1 ± 9.6 months. Male to feminine ration was 1.5: 1.70 Children‘s (60.3%) of

febrile seizure were simple seizures whereas 46 Children‘s (39.7%) were complicated. In

Children‘s with perennial febrile seizure, 25 had complicated seizures representing 54.3% of

total children with complicated seizures and seventeen children had a simple seizure. 6.9%

connected the cause on to looking and another 6.9% to witch craft. 33.6% of oldsters thought of

febrile seizure as a kind of brain disease. 26.7% of the oldsters recognized aspiration as associate

acute complication of seizure. Injuries (19.8%) and cardiopulmonary arrest (2.6%) were

recognized to a lesser degree. Health institutes and personnel (12.9%) and media (9.5%) were

weak sources of data. Ancient treatment was advocated by 30.2% of oldsters. Care to be applied

throughout a seizure was renowned by few and performed by fewer. Non-recommended or

perhaps harmful practices were thus prevalent (82%).

Navneet Kumar (2019) conducted a study and found out that febrile seizures are commonly

seen in children and about one-third of the children develop a recurrence of febrile seizures. The

main objective is to study the risk factors associated with recurrence of febrile seizures in Indian

children. This prospective, longitudinal study was carried out in the Department of Pediatrics,

GSVM Medical College, Kanpur. All children, 6 months to 5 years of age, attending the

department from February 2015 to January 2016 presenting with first febrile seizures were

included in the study and followed up for recurrence. Results of 528 children, 174 (32.9%) had

recurrence and 354 (67.1%) had a single episode of febrile seizures. Recurrence was more in

children <18 months (41.3%) as compared to children ≥18 months (24.1%). Children with

25

temperature 101°F during the seizure had a recurrence rate of 52.5% while recurrence was seen

in only 17.2% in children with temperature ≥105°F. There was a significant declining trend of

recurrence with increase in temperature. Recurrence was significantly more common in children

with a family history of febrile seizures (45.5%) as compared to those without family history

(27.8%). Multiple logistic regression analysis revealed that younger age at onset of first seizure,

lower temperature during the seizure, brief duration between the onset of fever and the initial

seizure, and family history of febrile seizures were risk factors significantly associated with

recurrence of febrile seizures in children.

SECTION-II: STUDIES AND LITERATURE RELATED TO EDUCATIONAL

INTERVENTION ON FEBRILE SEIZURE

R C Parmar (2011) conducted the study on knowledge, attitude and practices of parents of

children with febrile convulsion. In that Parental anxiety and apprehension is related to

inadequate knowledge of fever and febrile convulsion. Prospective questionnaire based study in

a tertiary care centre carried over a period of one year. 140 parents of consecutive children

presenting with febrile convulsion were enrolled. Chi-square test used. It result, 83 parents

(59.3%) could not recognise the convulsion; 90.7% (127) did not carry out any intervention prior

to getting the child to the hospital. The commonest immediate effect of the convulsion on the

parents was fear of death (n= 126, 90%) followed by insomnia (n= 48, 34.3%), anorexia (n= 46,

32.9%), crying (n= 28, 20%) and fear of epilepsy (n= 28, 20%). Fear of brain damage, fear of

recurrence and dyspepsia were voiced by the fathers alone (n= 20, cumulative incidence 14.3%).

109 (77.9%) parents did not know the fact that the convulsion can occur due to fever. The longterm concerns included fear of epilepsy (n= 64, 45.7%) and future recurrence (n= 27, 19.3%) in

the affected child. For 56 (40%) of the parents every subsequent episode of fever was like a

nightmare. Only 21 parents (15%) had thermometer at home and 28 (20%) knew the normal

range of body temperature. Correct preventive measures were known only to 41 (29.2%).

Awareness of febrile convulsion and the preventive measures was higher in socio-economic

grade (P< 0.05). At last concluded that parental fear of fever and febrile convulsion is a major

problem with serious negative consequences affecting daily familial life.

26

Magnil. L (2011) conducted a quasi-experimental study to assess the impact of health

education on knowledge and home management of febrile convulsion amongst mothers in a rural

community in North Western Nigeria. A one in three samples of fifty mothers that met the

eligibility criteria where selected using systematic random sampling. Interviewer administered

same structured questionnaire with close and open-ended questions to obtain data during pre and

post-test. The study concluded that the use of effective educational intervention programmes and

parental support groups will go a long way in reducing the incidence of febrile convulsions

among children in our communities.

Kepler (2011) conducted a prospective cross – sectional study on parent‘s knowledge and

attitude towards children with febrile seizure, and to identify contributing 21 factors to negative

attitudes conducted among parents attending the paediatric neurology clinics of king Abdul-Aziz

university Hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. A structured 40-item questionnaire was designed to

examine their demographics, knowledge, and attitudes. A total of 117 parents were interviewed,

57% were mothers. The level of knowledge among parents of epileptic children needs

improvement. Many have significant misconceptions, negative attitudes, and poor parenting

practices. Increased awareness and educational programme are needed to improve the quality of

life of this family.

Lovera. D (2011) conducted a cross sectional study to determine the knowledge, attitudes

and practices of parents and guardians of children with febrile seizure regarding the illness

conducted in Paediatric Clinic at Kenyatta National Hospital revealed that more than 77% of

the parents/guardians had some knowledge on the type of illness their children were suffering

from, the features of a febrile convulsion, the alerting features before febrile convulsions, the

type of antiepileptic drug treatment their children were receiving and the potential hazards to an

seizure child during a febrile convulsion. Samples consisted of 116 parents and guardians and

they were interviewed using a semi-structured questionnaire. Focused group discussions were

also carried out on 42 other parents and guardians. The study concluded that higher level of

formal education of the Parent/Guardian had a positive influence on their Knowledge and

practice towards febrile convulsion.

27

Swetha. K (2011) conducted a study which entitled the effectiveness of informational

booklet on cure and management of febrile seizure children was conducted in Karnataka. The

objectives were to assess the knowledge of mothers of febrile seizure children using the

structured knowledge questionnaire, to develop and validate a booklet on epilepsy care and home

management for mothers of febrile seizure children. Population comprised of mothers of children

with febrile seizure, who were in the age group of 2 to 12 years. Non probability purposive

sampling technique was utilised. Tools used for the study included, Background Information,

Structured Knowledge 23 Questionnaire and an Opinionnaire. The study concludes that the

information booklet on epilepsy care and home management and reinforced teaching was an

effective strategy for enhancing the knowledge of the mothers of febrile seizure children

regarding care and rehabilitation of their children.

Pooja. R (2012) conducted a prospective questionnaire-based study to evaluate the

knowledge, attitude and practice of mothers of under-five children suffering with febrile

convulsion at the Mofid children hospital. Sample consisted of 126 mothers of children with

febrile convulsion. The study result shown that most common cause of concern among parents

was the state of their child‘s health in the future, followed by the fear of reoccurrence, mental

retardation, paralysis, physical disability and learning dysfunction. Awareness of preventive

measures was higher in mothers with high educational level. Majority of mothers (76%) did not

know anything about the 19 necessary measures in case of recurrence. This study concluded that

parental fear of febrile convulsion is the major problem, with serious negative consequences

affecting daily familial life.

Misbha. K (2012) conducted a cross sectional study to evaluate the concerns and home

management of childhood convulsions among mothers in Tesbesun, Nigeria. Samples consisted

of 500 mothers of children with convulsion. A structured questionnaire was used for

interviewing the study subjects and the study period was 10 weeks. A result of the study showed

that fear of death was the commonest concern (450, 90%) among mothers. Putting the hand

and/or a spoon into the mouth of the convulsing child was the commonest unwholesome practice