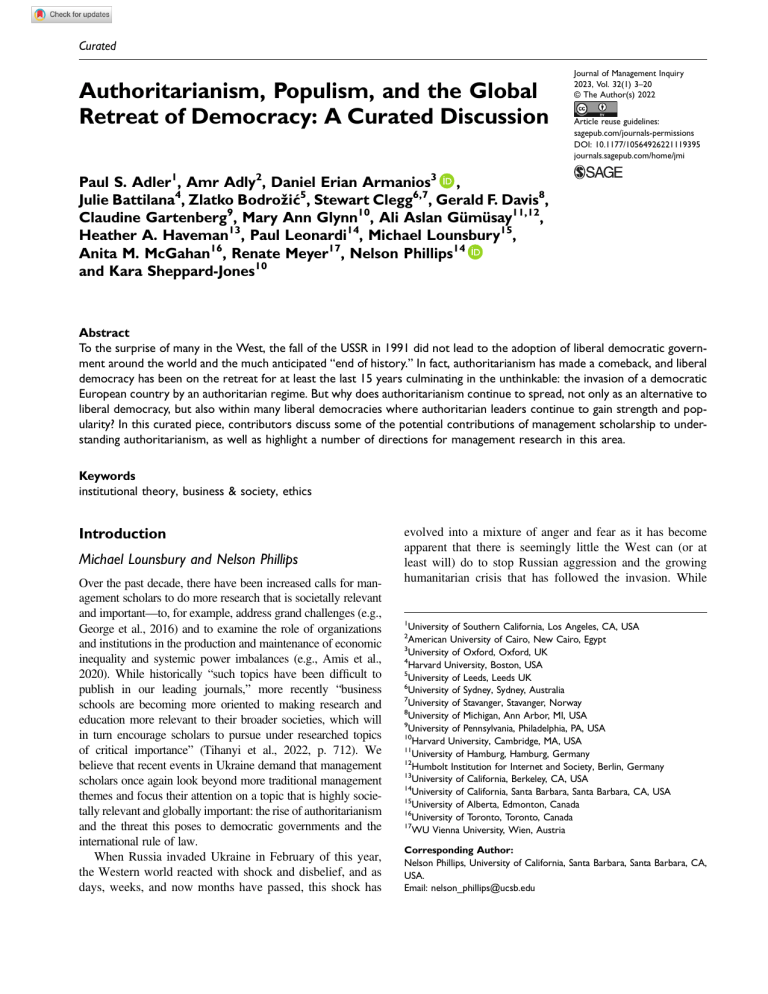

Authoritarianism, Populism, and Democracy: A Management Inquiry

advertisement