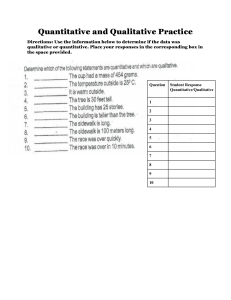

Summary Data Collection Methods in the Social and Behavioral Sciences I.1 Basics of Data Collection in the Social and Behavioral Sciences 2.1 Basic terms and concepts Theories are comprehensive systems of ideas which explain a specific section of reality. They systematize and summarize knowledge about phenomena in a certain area. In the social sciences, theories serve to describe, explain, and predict social phenomena. They often postulate causes for events, phenomena, or processes. Causes are components of causal explanations but should not be confused with reasons: A reason is a mental state which usually involves (conscious) intention. Causes can refer to reasons, but both should be clearly distinguished. When a theory is deliberately simplified, we call it a model. However, a model can also be formulated (and tested) without an underlying theory. A (research) paradigm is a set of concepts and practices, including research methods and standards, which are generally accepted in a scientific field. To test theories against reality, hypotheses are derived from them. A scientific hypothesis is a theoretically based assumption about real facts. Characteristics of scientific hypotheses are: Generalizability / general validity beyond the individual case. Formal structure of a conditional sentence ("if-then" or "the-the") Falsifiability, i.e. potentially refutable by empirical data. In order to be tested, scientific hypotheses need to be converted into statistical hypotheses. This requires determining how theoretical constructs that are not directly observable can be operationalized, i.e. made observable and measurable. Once this has been done, operational hypotheses can be formulated, which in turn form the basis for statistical hypotheses. In the social and behavioral sciences, the units of interest are described by their attributes or characteristics. The totality of a characteristic’s different expressions is a variable, i.e. something that can take more than one value. If variables are not directly observable, they are called latent variables or constructs (e.g. intelligence, motivation) and are measured by their indicators (e.g. an intelligence test), which need to be defined first. In contrast, the values of manifest variables can be directly observed or measured (e.g. a person's age). In the social sciences, variables are placeholders for characteristics of entities, persons, or objects that can take on different categories, levels, or values. A variable can take at least two, but often more values: the variable 'gender', for example, can take the values ‘male‘, ‚female‘ and ‘diverse’ (at least, at the time this is written). The presence or absence of a characteristic (e.g. smoker/non-smoker) can also be expressed as a variable. If characteristics only have one expression, however, they are called constants. Characteristics are measured through the assignment of numbers to their different expressions. The set of all measurements of a study is called quantitative data. If characteristics are described verbally, this is referred to as qualitative data. Chapter 2.2 “The quantitative and the qualitative research paradigm” In empirical social research, there are two research approaches or paradigms: the qualitative and the quantitative paradigm. Research paradigms in empirical social research The quantitative and the qualitative research paradigm differ quite fundamentally in their understanding of social science and social science research. This also affects how the role of the researcher and the research process are conceived. The quantitative and qualitative research paradigms work with different research designs, sample types, data collection methods and data analysis procedures. The distinction between quantitative and qualitative paradigms is ever-present in the social sciences, but there is some disagreement about how fundamental it really is. At the very least, it provides a useful framework for classifying research approaches and methods. Research paradigms: characteristics The central characteristic of the quantitative research paradigm is measurement. It stands in the tradition of the natural sciences and is committed to objectivism. The predominant epistemological approach in quantitative social research is critical rationalism, which specifies how empirical theories should be formulated and tested. The objects of measurement are manifestations and correlations of variables, especially causal relationships. In contrast, the qualitative research paradigm is based on a constructivist view of the world its central characteristic is interpretation. The qualitative research paradigm stands in the tradition of the humanities, but its scientific theoretical foundations are more inconsistent than those of the quantitative paradigm. They encompass various positions such as hermeneutics, dialectics, phenomenology, and others. Research based on the qualitative paradigm primarily aims at an understanding-interpretative reconstruction of social phenomena in their respective context. The focus is on the perspectives and interpretations of the participants, for example what’s important to them, which experiences have they made, what goals are they pursuing, and so on. Research on the basis of the quantitative paradigm Research based on the quantitative paradigm follows a deductive approach. Its objective is to obtain findings that can be generalized. The quantitative research process is usually linear and highly structured. It begins with the derivation of hypotheses from a theory. Subsequently, numerical data is collected with standardized instruments using samples that are as representative as possible. This is then analyzed with statistical methods to determine whether the hypotheses should be accepted or rejected. Research on the basis of the qualitative paradigm The qualitative paradigm follows an inductive approach. Its objective is to obtain a holistic understanding of social phenomena and their interrelation in their respective contexts. The research process is usually circular and deliberately unstructured. It begins with a general research question, for which non-numerical, verbal data is collected. The instruments and procedures that are used are nonstandardized or at most partially standardized. The samples are small and are deliberately selected according to content-related criteria. The data is analyzed interpretatively with the objective of developing new insights, hypotheses and theories. Some contrasts between quantitative and qualitative research Here you can see some chief contrasting features of quantitative and qualitative research, compiled by Alan Bryman (2016). On the left side, you see the orientation towards numbers and the researchers’ point of view, who usually have a great distance to their research object. As we have already seen, in quantitative research, theories are tested using a static and fully structured procedure with the objective of generalizing the findings and thus uncovering large-scale social trends and connections between variables. On the qualitative research paradigm’s side, the research object is described with words. The researchers are very close to their subjects, whose point of view they try to understand. Their objective is to develop theories and to gain a holistic understanding of social phenomena in their respective context. To do so, they proceed in a deliberately open and process-oriented way and focus only on small-scale aspects of social reality, such as group interaction. Some similarities of both paradigms The distinction between a quantitative and a qualitative paradigm is useful for classifying data collection methods and analytical procedures. However, the two paradigms have some common features, too: Both are fundamentally concerned with answering questions about the nature of social reality. For this purpose, they select research methods and approaches to the analysis of data that are appropriate to their research question. Both relate their findings to themes or issues raised in the research literature. Both collect large amounts of data, which is then systematically reduced to get a result. Both seek to uncover and then to represent the variation that they uncover. In addition, both include frequency in their analyses: In quantitative research, frequency is a core outcome of collecting data, but the analysis of qualitative data is also guided by the frequency with which certain themes occur. Both seek to avoid errors and deliberate distortion. Both make a point of being clear about their research procedures and how they arrived at their findings. Alan Bryman points out that research methods are much more free-floating than it is sometimes supposed. For example, qualitative research is not exclusively concerned with generating hypotheses and theories, but it is also used to shed light on them. An example is the study "When prophecy fails" by Lion Festinger and colleagues, who collected data through covert participant observations in a religious group whose members believed in an imminent apocalypse, to find evidence for Festinger's theory of cognitive dissonance. Moreover, in many cases it makes sense to combine qualitative and quantitative data collection methods. Method-mix and mixed methods paradigm A mix of methods is especially common in applied research, for example when semi-structured interviews or focus groups are used to gain input for the development of a fully standardized questionnaire. There are different types of mixed-method designs, four of which I’ll exemplify here: 1. In parallel designs, quantitative and qualitative data is collected simultaneously and with equal priority. The resulting analyses are then compared or merged to discover integrated findings. 2. In sequential designs, qualitative and quantitative research take place successively, for example to prepare a quantitative survey with the help of qualitative research. In this case, we speak of an exploratory sequential design. 3. Conversely, qualitative research can be used to supplement or interpret quantitative data in retrospect. In this case, we speak of an explanatory sequential design. 4. In an embedded design, either quantitative or qualitative research is enhanced with the other approach. Data collection can be simultaneous or sequential. Supporters of the mixed-methods paradigm emphasize that it is an independent research approach that goes beyond a mere combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches. They don’t see the basic assumptions of the quantitative and qualitative paradigm as insurmountable opposites, but rather as extremes between which a middle position can be taken, too. Chapter 2.3 „Research designs and objectives” Dimensions for the description of research designs One way of describing research designs is by their epistemic goal. Here we distinguish between basic research and applied research studies. Basic research aims at solving scientific problems by further developing theories and methods or by analyzing specific issues in greater detail. Basic research primarily contributes to gaining scientific knowledge. Although practical consequences or possible applications are usually discussed, they are not the focus of the research. In contrast, applied research aims at solving practical problems or improving matters with the aid of scientific methods and theories. it is therefore judged on the basis of the practicability of its results. Research designs can also be described in terms of their research object. A theoretical study presents and evaluates the current state of theory and research. Theoretical studies are based on literature reviews. They either summarize the current state of research in a review or overview article, or by conducting a meta-analysis. A methodological study’s research objects are scientific research methods. Methodological studies aim at examining and advancing qualitative or quantitative research methods, including, for instance, the development of new scales or psychological tests. In empirical studies, the researcher typically collects and/or analyzes data themselves in order to answer research questions or to test research hypotheses. A distinction is made between original studies, whose design is newly developed by the researcher, and replication studies, whose design is based on previous studies. Empirical research: Definitions The social and behavioral sciences are empirical sciences. In these, knowledge results from the systematic collection, processing and analysis of empirical data within the framework of an orderly and documented research process. Empirical data is information about the reality of experience that is specifically selected and documented with regard to the research problem. This information is collected with scientific data collection methods using appropriate standardized or non-standardized instruments. The empirical research process is fundamentally connected with scientific theories, which are either applied and tested or formed and developed in its course. Empirical data can only be interpreted meaningfully with reference to such theories. Dimensions for the description of empirical studies: Overview Empirical studies can also be described on the basis of different dimensions, for instance: their underlying scientific approach, their data basis, their research interest, the way research groups are formed and treated, the research setting, the number of objects that are studied, or the number of measurements. Dimensions for the description of empirical studies An important and very frequently used dimension for the description and classification of empirical studies is the underlying scientific approach. Here, a distinction is made between quantitative studies, qualitative studies and mixed-methods studies, according to the research paradigms we have already discussed. As data basis for empirical studies you can use primary data (analysis), secondary data (analysis), or other studies (meta analysis). By far most typical is the analysis of primary data, where the researcher collects data themselves and then analyzes them. In a secondary analysis, existing data sets are re-evaluated by the researcher. In a meta-analysis, the results of several directly comparable studies on a given topic are statistically analyzed and combined to produce an overall result. Since no original data is used in a meta analysis, it can also be considered a theoretical study. Empirical studies can also be described according to their research interest. Exploratory studies attempt to explore and describe a research object as precisely as possible, with the aim of developing hypotheses and theories. They are theory-generating studies that usually follow a qualitative research paradigm. In contrast, explanatory studies serve to test hypotheses and the theories from which the hypotheses were derived. As a rule, such theory-testing studies are based on the quantitative research paradigm. Descriptive studies are quantitative studies which describe the distribution of characteristics and effects in large populations, for instance that of a country. An important goal of explanatory studies is the testing of causal hypotheses. To allow for causal conclusion, at least two groups need to be formed, treated differently, and then compared with each other. Depending on how these groups are composed and treated, we speak of an experimental, quasi-experimental or non-experimental research design. Finally, empirical studies can also be classified according to whether they are conducted in a laboratory or in the field, i.e., in a natural environment, whether several cases or only a single case are studied, and whether one or several measurements are carried out. Chapter 3. „Quality criteria in empirical research” What are characteristics of good science? What distinguishes high-quality scientific work from average or weak contributions? Standards of science and scientific quality criteria To assess the quality of a scientific study, the first basic question is whether a scientific approach has been taken at all. This can be judged by four basic standards that must be met by any scientific study. You can see them here on the left: First, we need to have a scientific research problem. This means that the research questions or research hypotheses need to refer to aspects that can be studied empirically, and that they need to be based on the current state of scientific knowledge. The second point is the scientific nature of the research process, which includes the use of established scientific research methods and techniques at all stages of the research process. The research process also needs to follow ethical rules. For example, a study loses its scientific character if data are manipulated, if ideas are stolen, if funders or conflicts of interest are concealed, and so on. We will take a closer look at such ethical rules in our last session. It is also necessary to document the entire research process in such a way that it can be understood and replicated by other researchers. Without such documentation, others can’t assess the quality of a study. If these basic standards of science are fulfilled, the next question concerns the study’s scientific quality. Corresponding with the standards of science, there are four scientific quality criteria, which you can see on the right-hand side. They tell you whether you are dealing with an outstanding, good, average or weak study. The degree to which these criteria are met can vary greatly in different studies. The criterion “relevance“ includes the scientific relevance as well as the practical relevance of a study. “Methodological rigor” refers to different types of validity, depending on the research paradigm. We will look at these in more detail in a moment. “Ethical rigor” concerns the study’s orientation at ethical guidelines and codes of scientific conduct, and … “Presentation quality” refers to documentation, but also to standards of reporting, for example completeness, weighting and structuring of the content, readability, clarity, etc. Among the four scientific quality criteria, methodological rigor is particularly important. We will therefore take a closer look at it now. Quality in quantitative and qualitative research In quantitative empirical research, methodological rigor is described primarily with the concept of validity. This encompasses construct validity, internal validity, external validity, and statistical validity. These four types of validity are widely recognized in quantitative research and elaborated in detail for many areas. In qualitative research, on the other hand, there is less consensus: There has been – and still is – a controversial discussion about suitable quality criteria for qualitative research. Various researchers have proposed different frameworks, of which I will present the one by Lincoln and Guba as an example. Quality in quantitative research: validity But first, let's start with the quality criteria for quantitative research. The central criterion here is validity. Research validity refers to the correctness or truthfulness of an inference that is made from the results of a study. In quantitative research, the typology of Donald T. Campbell, an American psychologist and methodologist, and his colleagues is decisive. This is how they define validity: „We use the term validity to refer to the appropriate truth of an inference. When we say something is valid we make a judgement about the extent to which relevant evidence supports that inference as being true or correct.“ The four types of validity refer to the generation, accuracy, and transferability of conclusions about causal relationships. Validity is not either fulfilled or not, but is best seen as falling on a continuum rather than into dichotomous categories of 100% versus 0% valid. The goal is to maximize all four types of validity as much as possible. However, we cannot incorporate all the methods and procedures that would enable us to simultaneously achieve all four types of validity in one study. Sometimes, a method with which we can achieve one type of validity even reduces the chances of achieving another type of validity. We will see that this is especially true for internal and external validity. It is also important to keep in mind that we are talking here about the validity of scientific inferences, especially those about causal relationships. This depends primarily on the quality of the study design. It must not be confused with the test quality criteria of objectivity, reliability, and validity, which refer to measuring instruments. Internal validity Let’s start with internal validity. A study is considered to be internally valid if the relationship between the variables can be interpreted as causal with a high degree of certainty. Internal validity therefore concerns the question to which extent the presumed causal influence of the independent variables on the dependent variables can be proven for the effects of interest. Internal validity depends primarily on the quality of the study design and its implementation. External validity A study is considered externally valid to the extent that its findings can be generalized beyond the context of the study. External validity thus concerns the extent to which the study’s results can be generalized to other places, times, treatment variables, treatment conditions, or people than those that have been studied. External validity depends primarily on the quality of the study design and the sampling. It is threatened when there is an interaction of the causal relationship with subjects, outcomes, settings, or over treatment variations. Therefore, the representativeness of the sample and the control of confounding variables have a major impact on the external validity. Construct validity When theoretical constructs or concepts that can’t be observed directly are to be measured, they first must be precisely defined and operationalized. This involves specifying through which observable attributes and with which instruments the theoretical concept should be measured. Construct validity concerns the extent to which a study actually allows inferences about what is intended to be measured, or in other words: the extent to which the operations used in a study represent the higher-order constructs. The more this is the case, the more valid are inferences about the higher-order constructs. Construct validity depends primarily on the quality of the concept specification and operationalization. Another decisive factor is the construct validity of the respective measuring tools. Validity of measuring tools The construct validity of a measuring tool, like the construct validity of a study, concerns the question of how well the underlying theoretical construct is captured or measured. The construct validity of a measuring tool depends on the tools’ quality, which is described by the three quality criteria: objectivity, reliability, and validity. A measuring tool can only provide valid measures if it’s also reliable and objective. Statistical conclusion validity A quantitative empirical study has statistical conclusion validity if the results of the study are based on correct descriptive and inferential statistical analyses. Statistical conclusion validity thus concerns the question of whether the statistical analyses were performed correctly so that the results are statistically significant and have a theoretically or practically relevant effect size. Statistical conclusion validity depends primarily on the quality of the statistical data analysis. However, aspects of the study design are also relevant, for example the sample size or the reliability of the chosen measuring tool. Statistical conclusion validity is threatened, for example ... if the statistical data analysis is not based on hypotheses but searches for significance without theory, or if inadequate statistical procedures are used, or by insufficient power of significance tests, for example it the sample size is too small. Quality criteria for quantitative and qualitative research As already mentioned, there is less consensus between researchers here. Quality in qualitative research The framework most frequently cited in the international literature was proposed by the American educationalist Yvonna Lincoln and her colleague Egon Guba. They distinguish four criteria for evaluating the trustworthiness of qualitative research. Quality in qualitative research: trustworthiness According to Lincoln and Guba, good qualitative research should meet, above all, the criterion of trustworthiness, that is: it needs to convince its audience that its findings are true. Lincoln and Guba (1985) propose four criteria of trustworthiness, namely credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. The most important quality criterion in the trustworthiness framework is credibility. This is about whether the conclusions and interpretations drawn from the data are justified. Credibility is therefore the qualitative counterpart to internal validity. Aspiration: establish confidence in the “truth” of a study’s findings and interpretations based on its data. In the qualitative research process, trustworthiness is ensured by, among other things ... comprehensive data collection, for example by prolonged engagement or persistent observation, but also by combining different data, methods, and researchers peer debriefing, questioning assumptions by analyzing negative cases using the raw data to check interpretations, and through consultation with the research subjects. Transferability is about ensuring that a study’s findings or conclusions can be transferred to other contexts. This corresponds to the quantitative criterion of external validity. To estimate the transferability of findings to other persons and contexts, a thick description of the research subjects and context conditions is required. Aspiration: the study’s findings or conclusions can be transferred to other contexts. Dependability describes the extent to which the design and procedure of a study is comprehensible. It corresponds to reliability in quantitative research. Dependability is ensured, for example, by an inquiry audit, in which the research team explains and justifies its approach to experts. It can also be ensured by triangulation, which means that some steps of the research are carried out simultaneously by different members of the team (stepwise replication) or that the data obtained with one method is checked with another method (overlap methods). Aspiration: comprehensible study design and procedure (that could thus be replicated). The fourth criterion of trustworthiness is confirmability, which means that the findings were not predetermined or influenced by biases, interests, perspectives, etc. of the individual researchers. It thus represents the qualitative counterpart to objectivity. Aspiration: the findings are not predetermined by biases, interests, or perspectives of individual researchers. Confirmability is examined in confirmability audits. Here, the research team presents the available data and the documentation of the research process and explains it in detail. Arguments in favor of the trustworthiness model are its worldwide recognition, but also the availability of extensive references and checklists. These make it easier to check whether the four quality dimensions are met by one's own study or by published studies. Chapter 4.1 Experimental study designs Experimental study designs are used to test causal hypotheses by systematically varying (= “manipulating”) potential influencing factors. The aim is to test the causal influence of one or more independent variables (IV) on one or more dependent variables (DV). Independent variables always precede dependent variables and are manipulated by the researcher. At the same time, the influence of other variables (“confounding variables” or “confounders”, e.g. characteristics of the subjects or the situation) on the dependent variables is “controlled” in experimental designs by keeping the experimental conditions as constant as possible, comparison of at least two groups, and random assignment of subjects to these groups (= “randomization”, see below). Thus, the observed variation in the dependent variables can be attributed to the effect of the independent variables beyond doubt, as alternative explanations can be ruled out. True experiments therefore have high internal validity and are considered the gold standard for testing causal hypotheses. A classic experimental design, also called a randomized control trail (RCT), is characterized by: Several groups In addition to one or more treatment groups that receive the experimental treatment, the classic experimental design always contains a control group that is either treated in the conventional way or not treated at all. The simplest form of experimental design is the two-group design. Randomization Subjects are randomly assigned to control and treatment groups to ensure that the groups’ socio-demographic and psychological characteristics are comparable. Randomization also ensures that characteristics that could potentially be confounding variables (e.g. differences in intelligence or motivation of subjects) are distributed evenly between control and treatment groups. Experimental manipulation To test whether an independent variable has an influence on a dependent variable, the independent variable is systematically varied (= experimental manipulation) and the resulting effect on the dependent variable in the control and treatment groups is measured. Providing that the confounding variables have been carefully controlled, causal conclusions can be drawn from the comparison of effects between groups. Control of conditions In addition to person-related confounding variables, environmental or study-related confounding variables (e.g. noise, heat, technical problems, experimenter effects, etc.) can reduce the validity of experiments. To eliminate environmental confounding variables or at least keep them constant, experiments should take place under precisely controllable conditions if possible (ideally in a laboratory). To reduce biases that arise from the participants’ or experimenter’s expectations, experiments should be blinded if possible. Experimental designs are used, for example, in medical research to test the effects of new drugs. In these cases, the control group receives either a placebo (= no intervention) or the so-called “standard of care”, i.e. an already established treatment. Compared to this, the new drug should prove superior. Treating control groups with placebos is common to prevent participants from realizing they are not receiving a treatment. Ideally, clinical trials are double-blind, i.e. neither participants nor researchers know whether a person is receiving a placebo or a verum (= a drug containing an active substance). If a double-blind study is not possible for practical or ethical reasons, at least the participants should be blinded (= single-blind study). Quasi-Experiment In quasi-experimental studies, existing groups are used to test causal hypotheses (e.g. school classes, work groups, etc.), so there is no random assignment of subjects. However, like in a true experiment, the groups are systematically treated differently and the resulting effects on the dependent variable(s) are measured. This design is also referred to as a non-randomized controlled trial (NRCT). Due to the lack of randomization, the internal validity of quasi-experimental studies is lower than that of true experiments: differences between experimental and control groups cannot be clearly attributed to the independent variable. Therefore, controlling potential confounding variables that result from individual differences is very important in quasi-experimental study designs. By parallelizing or matching of samples, for example, it is possible to create groups that are homogeneous with respect to certain potential confounding variables. Other options are to include potential confounding variables as independent variables in the study design, or to control them statistically. Chapter 4.2 Non-experimental study designs Non-experimental studies are studies in which pre-existing groups are compared without randomization or active experimental manipulation. Non-experimental designs are also referred to as “natural experiments”, correlation studies, observational studies or ex post facto studies, since one only observes what is there or determines effects in retrospect (= “ex post”). In the social and behavioral sciences, non-experimental studies are the most common study design. The internal validity of non-experimental studies is even lower than that of quasi-experimental studies: although they allow conclusions about correlations between variables, it is not possible to draw conclusions about the existence of cause-effect relationships in one direction or the other. Example: People who laugh a lot state in surveys that they are happier than others. Consequently, a positive correlation is found between the variables 'laughter' and 'happiness'. This could be because happier people laugh more, or because laughter makes people happier. However, it could also be that there is no causal relationship between laughter and happiness at all, but that both variables are causally influenced by a third variable. Based on these two variables alone, a deduction such as “laughter makes people happier” is not valid since causality has not been proven. Conclusions about a potential causal relationship can only be drawn from non-experimental studies if variables are highly unlikely to be dependent variables, for example because they are innate (such as gender, handedness, number of siblings). Such person- or environment-bound variables simply cannot be manipulated, which is why in the social sciences, non-experimental study designs are sometimes the only option. Moreover, research in the social and behavioral sciences often is not concerned with proving causality at all, but rather with testing hypotheses of difference, correlation, or change. Hence, non-experimental studies are conducted when ... 1. non-causal research questions are addressed, or 2. causal research questions are addressed, but an experimental manipulation of the independent variables is not possible, the organizational or financial effort of an experimental manipulation would be too high, or an experimental manipulation would not be ethically justifiable (e.g. if the effects of potentially harmful content, substances, or the like are to be tested). Chapter 4.3 Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies Both (quasi-)experimental and non-experimental studies can be designed as cross-sectional or longitudinal studies. In a cross-sectional study, one sample is examined at one point in time. Cross-sectional studies always represent snapshots which do not allow conclusions to be drawn about developmental processes or changes in behavior. Cross-sectional designs are frequently used in empirical social research, as the effort required for both the researchers and the participants is comparatively low. Many market and opinion research studies are crosssectional studies in which, for example, the participants’ opinions or preferences at a certain point in time are surveyed. Cross-sectional studies allow statements about differences between groups of people with regard to the variables of interest (e.g. attitude toward a particular issue among voters of different parties) at the time the data is collected. In longitudinal studies, samples are repeatedly examined over a longer period in order to record changes in the variables of interest. The same empirical study is thus conducted at several (at least two) points in time in order to then compare the results of the individual “waves”. In addition to testing hypotheses of change, a longitudinal design is “the comparatively best way to test causal hypotheses for variables that cannot or may not be varied experimentally”. There are three types of longitudinal studies: Trend studies A trend study consists of several cross-sectional studies, i.e. the same study is conducted in different samples at intervals. The prerequisite for comparing data from several samples is that it is representative of the population of interest (e.g. the population of a country). Trend studies are used, for example, to monitor social and societal developments. However, it is not possible to make statements about individual changes, from which causal relationships between different variables could be derived, on the basis of trend studies. Panel studies In a panel study, the same sample (= the panel) is surveyed at several points in time. Compared to trend studies, panel studies are therefore “true” longitudinal studies that also allow individual changes to be analyzed and conclusions about causal relationships to be drawn. They are, however, much more time-consuming than trend studies, especially if a panel is to be studied for years or even decades. For the same people to be reached again after a longer period of time, a panel needs to be managed and maintained carefully – the longer the period, the more carefully. Nonetheless, if panel studies run over long periods, it cannot be avoided that participants drop out of the panel due to relocation, illness, death, or other reasons (so-called “panel mortality”). In addition to careful maintenance of the panel, it is therefore necessary to begin with a sufficiently large sample. Panel mortality can lead to systematic biases if the attributes of those who drop out differ from those who remain in the panel. Repeated surveying of the same people can also influence the findings, e.g. if the research leads them to develop, reflect on, or consolidate certain attitudes or behaviors. Moreover, changes in participants’ personal circumstances (e.g. birth of children, career advancement) can alter a panel’s composition so that it is no longer representative of the population. Cohort studies A cohort is a group of individuals in whose biographies certain events (e.g., birth, school enrollment, etc.) occurred at approximately the same time. In longitudinal studies, cohort designs are used to observe members of a cohort over an extended period of time. A classic example of a cohort study is the British National Child Development Study (NCDS), for which data was collected from 11,407 individuals born within one week (from March 3 to 9, 1958) in the UK, at ages 7, 11, 16, 23, and 33 (e.g., Ferri, 1993). Cohort studies are a special type of panel studies, which are limited to specific cohorts. However, cohort studies only allow conclusions about age effects (i.e., individual changes over the life span), while panel studies allow both age and cohort effects (i.e., differences between different age groups) to be analyzed. The effort and expense of cohort studies is comparable to that of panel studies that run over longer time spans. “Panel mortality” also exists in cohort studies: the cohort which was surveyed in the NCDS, for example, included 17,414 individuals at the outset in the fifth wave in 1991, data could still be collected from 11,407 individuals. A special type of longitudinal study are studies with repeated measurements. An example are pre-post designs, in which certain attributes are measured before an intervention (pre-test), then the intervention takes place, and afterwards the same attributes are measured again (post-test). Further measurements (follow-ups) can be carried out at intervals to analyze the stability of the observed effects. If the treatment group is compared with a control group which receives either no treatment or a different treatment between the pre-test and post-test, this is a (quasi-)experimental longitudinal design. Pre-post designs are used in medical research, but also for the evaluation of new psychotherapeutic approaches, training concepts, forms of work, etc. Chapter 4.4 Laboratory and field studies Laboratory studies take place in an artificial environment and thus under controllable conditions. This way, it is possible to largely exclude the influence of environmental confounding variables and thus to increase the results’ internal validity. However, this is at the expense of external validity since the artificial conditions reduce the results’ transferability to everyday life. In contrast, the external validity of field studies is usually high since they take place in a natural environment. Thus, the study conditions are similar to or even identical with everyday conditions. “In the field”, however, it is more difficult to control potential confounding variables, which can limit the results’ internal validity. Summary In the social and behavioral sciences, knowledge results from the systematic collection, processing and analysis of empirical data. The central characteristic of the quantitative research paradigm is measurement, and that of the qualitative research paradigm is interpretation. Research based on the quantitative paradigm: Deductive approach: testing of hypotheses => testing theories against reality Aim: generalization of findings Collection of numerical data, which is analyzed with statistical methods Research based on the qualitative paradigm: Inductive approach: development of new hypotheses and theories Aim: holistic understanding of social phenomena in their respective contexts Typically, collection of non-numerical, verbal data, which is analyzed interpretatively In many cases, it can be useful to combine qualitative and quantitative data collection methods. Mixedmethod designs include parallel designs, exploratory or explanatory sequential designs, and embedded designs. The quality of an empirical study can be judged by its relevance, methodological rigor, ethical rigor, and presentation quality. In quantitative empirical research, methodological rigor is described primarily by the concept of validity; this refers to the correctness or truthfulness of an inference that is made from the results of a study. Donald T. Campbell and his colleagues introduced four types of validity: Construct validity Internal validity External validity Statistical conclusion validity According to Lincoln and Guba, good qualitative research should, above all, meet the criterion of “trustworthiness”. This involves establishing its Credibility Transferability Dependability Confirmability Common study designs in quantitative empirical studies include experimental, quasi-experimental, and non-experimental designs. These can be conducted as cross-sectional or longitudinal studies in the laboratory or in the field. In experimental studies, causal hypotheses are tested by systematically varying influencing factors (independent variables) and measuring the effects on one or more dependent variables. True experiments have a high internal validity and are considered the gold standard for testing causal hypotheses. Cross-sectional studies allow conclusions to be drawn about differences between groups of people with regard to the variables of interest at the time of data collection. In longitudinal studies, samples are repeatedly examined over a longer period in order to record changes in the variables of interest.