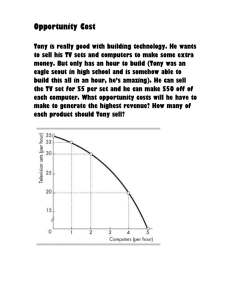

Principles of Microeconomics Status Reading Author Dr. Jose J. Vasquez Publishing/Release Date Publisher Link https://life-economics.mylearnworlds.com/course? courseid=econ102uiuc Summary Score /5 Type Textbook Five Basic Principles Five Basic Principles The Economic Problem Modern economics is based on a few major principles. Master these principles and you not only go a long way to understand everything that comes afterward in this course, but also be a much better decision maker in your daily life. But before you learn these principles you must understand when to apply them; namely the scope of modern economics. What is the Main Economic Problem? All resources are scarce. This truth drives modern economics, and limits the scope of study to the following question: Principles of Microeconomics 1 What is the best way for society to distribute a scarce resource? Three important conclusions follow from this simply question statement. First, the “what” refers to some kind of distributional scheme. For instance, the capitalist system is a distributional scheme that relies heavily on the idea of free markets to distribute scarce resources among members of society. The socialist system, on the other hand, is a distributional scheme that relies heavily on a central entity (e.g. the government), to distribute scarce resources. Second, the word “best” refers specifically to a situation where society uses all its resources in their most efficient way. Economist have a pretty straightforward way of operationalizing this situation: ❕ A situation if efficient when it is impossible to change it without reducing the net benefits associate with it. Finally, a scarce resource is any resource that exist in a limited quantity. As it turns out, this definition of scarcity encapsulates pretty much anything we can think of; from concrete goods such as coal and clean air to more abstract ones such as ideas, time and even romantic relationships. Yes, unless you think you could start a romantic relationship with the first person you see walking along the street without even doing any effort, then good romantic partners are also a scarce resource, and hence we can apply economics to it. Nothing exist in infinite quantity. Therefore, economics would have something to say about pretty much anything you can think of. The Nothing is Free (Opportunity Cost) Principle Since no resources exist in unlimited quantity, using any amount of any resource mean giving something up. Think about the time you are taking to read this sentence; oopss; it is now gone. Or the time you are taking to read this new sentence…yeah, that is now gone too. And, by the time you are done reading this complete section of the book you probably have given up 10-15 minutes you Principles of Microeconomics 2 could have used to do something else, like reading a book for another one of your courses, or spending time with your friends. Every action any other economic agent take carries a trade off given taht resources are always in limited quantity. Economists call this trade off an opportunity cost. The opportunity cost of any economic action or good or service is the net value of the best alternative. so from now every time we mention the word “cost” in this course we are really taking about an opportunity cost. For example, part of the cost of eating a burger for lunch, is the value you would have received from eating your next best alternative, a slice of pizza. And part of the cost of attending college is the salary you could be earning in your best job opportunity. It is going to take some time, and much practice, for you to start thinking of all costs as the opportunity lost. But, once you do, you will have an edge over non-economists in terms of decision making. The Net Marginal Benefit Principle Since economics deal with the way people make decision, we are forced to make some basic assumptions about the way people make decisions. The simplest assumption we can make about people’s choices is the following: ❕ A rational economic agent (say a person or a firm), will take an action if, and only if, that ONE action increases net marginal benefits for that economic agent. This assumption has two major implications. First, when we evaluate economic actions, we only consider the consequence of that single action. Economists called this the marginal change of that action. Second, no rational economic agent will take an action if the marginal costs of that action outweigh the marginal benefits of that action. If they did, then the net marginal benefits will decrease. Principles of Microeconomics 3 Notice that one problem of using averages to make decisions is that they include events that already took place and you have no way of changing. Economists call this type of events sunk costs. For instance, suppose you purchase a brand new tractor to improve the efficiency of your farm. Can you increase the price of the corn you sell in order to pay for the large investment costs of purchasing the new tractor? Of course you can not! If you did no buyer will buy corn from you, since they could probably buy it from your next door farmer; after all, corn is usually the same no matter where you buy it. Unfortunately for you, the money you spent buying the tractor is gone and you can’t get back, so no point in considering it when deciding what to do about the next bushel of corn you sell. The net marginal principle will take you some time to master. In the meantime, just try to remember the following two rules when making a decision about what to do: ❕ 1. never make decisions based solely on AVERAGES. 2. never make decisions based on things that have already taken place, and hence Principles of Microeconomics 4