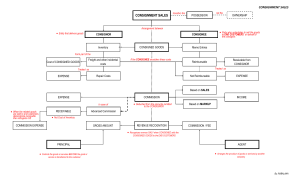

◌ِ Faculty of Commerce Assiut University LECTURES NOTES IN SPECIALISED ACCOUNTING Part I Compiled and Edited by Dr. Mostafa Kayed PhD in Accounting Preface The accounting courses you have already studied over the previous semesters included a general accounting framework suitable for the economic units, whether these units take the form of sole proprietorships, partnerships, or corporations. However, there are some economic activities require different accounting application and the accounts’ style. This difference extends to the books and ledgers that these units keep to properly prepare the financial statements for the entities that perform such activities. This book presents some of these activities and discusses the relevant accounting approaches to compute the profits/surplus or losses/ deficit and prepare the financial statements. Notable that this book ignores some other activities that require special accounting applications not because they are less important but because of the limited time allocated for teaching this course. The author hopes that the desired objectives of studying this book will be realised. Dr Mostafa Kayed 2 Table of Contents Chapter One: Accounting for Consignment ....................... - 2 Chapter Two: Accounting For Clubs And Societies .......... - 2 Chapter Three: Revenues Recognition …………………..- 2 - 3 CHAPTER ONE ACCOUNTING FOR CONSIGNMENT 4 Chapter One Accounting for Consignment Learning Objectives: After studying this chapter, you will be able to: • Understand the special features of the consignment business, the meaning of the terms consignor and consignee. • Analyse the difference between the sale and consignment transactions and understand why consignment is termed a special transaction. • Practise the accounting treatments for consignment transactions and events in the books of consignor and consignee. • Note the variations in accounting when goods are sent at cost and goods are sent above the cost. • Learn the technique of computing the value of closing inventory lying with the consignor and the amount of Inventory reserve. • Learn the technique of computing the cost of abnormal loss and treatment of insurance claims in relation to it. • Understand the distinction between the ordinary commission, delcredere commission and over-riding commission paid to the consignee. • See the variety of accounting treatment for bad debts when the consignee is paid ordinary commission and when the consignee is paid del-credere commission in addition. • Understand the reason for including/excluding various expenditures to cost while valuing the goods returned by the consignee. 1. The consignment as a concept: -5- To consign means to send. In Accounting, the term “consignment account” relates to accounts dealing with a situation where one person (or a firm) sends goods to another person (or a firm) on the basis that the goods will be sold on behalf of and at the risk of the former. The following should be noted carefully: 1) The party which sends the goods (consignor) is called the principal. 2) The party to whom goods are sent (Consignee) is called the agent. 3) The ownership of the goods, i.e., the property in the goods, remains with the consignor or the principal – the agent does not become their owner even though they are in his possession. On sale, of course, the buyer will become the owner. 4) The principal does not send an invoice to the agent. He sends only a proforma invoice, a statement that looks like an invoice but is really not one. The object of the proforma invoice is only to convey information to the agent regarding the particulars of the goods sent. 5) Usually, the agent recovers from the principal all expenses incurred by him on the consignment. This, however, can be changed by agreement between the two parties. 6) It is also usual for the agent to give an advance to the principal in the form of cash or a bill of exchange. It is adjusted against the sale proceeds of the goods. 7) For his work, the agent receives a commission calculated based on the gross sale. For ordinary commission, the agent is not responsible for any bad debt that may arise. If the agent is to be made responsible for bad debts, he is to be paid a commission called del-credere commission. It is calculated on total sales, not merely on credit sales until and unless agreed. -6- 8) Periodically, the agent sends to the principal a statement called Account Sales. It sets out the sales made by the agent, the expenses incurred on behalf of the principal, the commission earned by the agent and the balance due to the principal. 9) Firms usually like to ascertain the profit or loss on each consignment or consignments to each agent. 2. Advantages of consignment arrangements: A consignment arrangement offers certain advantages to both the consignor and the consignor. A consignor may prefer shipping goods on consignment for the following reasons: - Wider market for a product: dealers may not be willing to assume the risk of purchasing certain goods such as a new product or an item that may become obsolete but may be willing to carry them on consignment. - Control over selling price: if gods are sold directly to the consignee, the consignor may find it challenging to establish and control the selling price of goods. - Recovery of an asset: since the legal title does not transfer to the consignee, the consignor has the right to possession of all unsold goods or the right to payment for goods sold if the consignee declares bankruptcy. Creditors of the Consignee do not have the claim against the consigned assets that they would have if the goods had been sold to the consignee. On the other side, the consignee may find a consignment arrangement attractive primarily for the following reasons: -7- - Avoid risks of ownership: Goods that do not sell or become obsolete, deteriorate, or decline in market value may be returned to the consignor. - Requires less capital: the consignee does not incur liability and does not make a cash payment on the goods until they are sold (despite sometimes the consignor requires the consignee to send an advance once he receives the goods on consignment). Thus the consignee’s capital investment will be lower if the goods are held on consignment. 3. Rights and responsibilities of the Consignee: Before goods are transferred on consignment, a written agreement should specify clearly the intent of the parties. The agreement should address such issues as the amount and type of the consignee's expenses to be reimbursed by the consignor, how the consignee's commissions are to be computed when commissions are to be paid, the credit terms and conditions, if any, to be considered by the consignee in granting credit, and the responsibility for collection of receivables and losses on receivables (bad debt written off). The agreement, also, should be complete and attempt to avoid potential points of conflict. The commercial law has to be applied for items not provided for in the agreement that results in litigation. 3.1 Rights of the Consignee: Some of the more important rights and responsibilities of the consignee are: - Compensation: The Consignee has a right to be compensated for services performed. Usually, this compensation is stated as a percentage of the sales price, or the consignee is permitted to retain -8- all the sales prices above a specified amount. - Reimbursement for Advances and Necessary Expenses: Unless otherwise provided for in the agreement, the consignor, as the owner of the goods, is responsible (or all costs incurred that are directly related to the sale of the goods (for example, freight and insurance on the goods while in transit to the consignee's place of business). Before the goods are sold, several expenses that are directly related to the sale may be paid by the consignee for the convenience of the consignor. In addition, in some cases, the consignee may make an advance to the consignor before the sale is made to a third party. The consignee has the right to be reimbursed for such advances and expenses. Usually, recovery is made by deducting the expenses and advances from the amounts collected from the sale of tile consigned goods. If the collection ؛are insufficient to cover these expenses and advances, the consignee has a direct claim against either unsold goods or receivable balances on items already sold. - Granting of credit: unless limited by an express agreement, the consignee has the right to sell goods on credit and extend normal credit terms. Of course, the consignee must exercise due care and act prudently in the granting of credit. A consignee may guarantee the collection of the receivables balance. The consignee is referred to as a del-credere agent and generally receives additional compensation for assuming this risk. - Warranty of Consigned Goods. The consignee has the right to make warranties that are normal for the product being sold. 3.2 Responsibilities of the Consignee: -9- - Care and protection for consigned goods: The Consignee must provide reasonable care and protection that fits the type of goods being held and care for the goods in accordance with specific instructions for the consigner. - Identification of consigned goods and receivables: Although physical separation is not required, the consignee must establish sufficient controls and provide adequate accounting records to identify consigned goods and consignment receivables. - Due care in granting and collecting receivables: The Consignee must express reasonable effort to assure that the goods are sold at the specified price, that normal credit terms arc granted, that a normal warranty is made, and that a reasonable effort is made to collect the sales price. - Timely Periodic Reporting of Sales and Collections: The Consignee must report the sales and collections activities during the period and settle the account with the consignor for in the consignment agreement. The report rendered by the consignee is referred to as "account sales". Typically, this report presents information related to the received goods on consignment, the expenses incurred by the consignee, the consignee's commission, in addition to the net amount deserved by the consignor. 4. The distinction between goods on consignment and goods on sale: Consignment Account relates to accounts dealing with such business where an entity or a company (the consignor) sends goods to another entity or company (the consignee) on the basis that such goods will be sold on behalf of and at the risk of the consignor. - 10 - Consignment Ownership of the goods remains with the consignor until the 1 consignee sells them, no matter whether the goods are transferred to the consignee. The consignee can return the 2 unsold goods to the consignor. Sale The ownership of the goods transfers with the transfer of goods from the seller to the buyer. Goods sold are the property of the buyer and can be returned only if the seller agrees. The consignor bears the loss of It is the buyer who will bear the loss, 3 goods held with the consignee. if any, after the delivery of goods. The relationship between the 4 consignor and the consignee is that of a principal and agent. Expenses done by the consignee to 5 receive the goods and keep them safe are borne by the consignor. The relationship between the seller and the buyer is that of a creditor and a debtor. Expenses incurred by the buyer are to be borne by the buyer after the delivery of goods. 5. Distinction Between Commission and Discount Commission Discount The commission may be defined as remuneration of an employee or agent relating to services performed in connection with sales, purchases, collections or other types of business transactions and is usually based on a percentage of the amounts involved. Commission earned is accounted for as an income in the books of accounts, and commission allowed or paid is accounted for as an expense in the The term discount refers to any reduction or rebate allowed and is used to express one of the following situations: An allowance is given to settle a debt before it is due, i.e. cash discount. An allowance is given to the whole sellers or bulk buyers on the list price or retail price, known as a trade discount. A trade discount is not shown in the books of account separately, and it - 11 - books of the party availing such is shown by way of deduction from facility or service. the cost of purchases. 6. Accounting for Consignment Transactions and Events: The Books Of The Consignor For ascertaining profit or loss on any transaction (or series of transactions), there is one golden rule; open an account for the transaction (or series of transactions) and (i) put down the cost of goods and other expenses incurred or to be incurred on the debit side, and (ii) enter the sale proceeds as also the cost of goods remaining unsold on the right hand or the credit side. The difference between the total of the two sides will reveal profit or loss. There is profit if the credit side is more. - Open Consignment Account and debit it with the cost of goods and credit it with "Goods sent on Consignment Account" as follows. Consignment to the agent …… Goods Sent on Consignment ××× ××× To record sending goods to the agent …… - - Recording the expenses incurred by the consignor by debiting the consignment account and crediting the cash Consignment to the agent ……. ××× Cash ××× To record the expenses paid to send the merchandise to the agent ……. If the consignee sends an advance ( cash or a note receivable), debit Cash consignee’s personal account: Cash Or Notes Receivable The Agent ……. To record receiving cash/ a note receivable from the agent ……. - 12 - ××× ××× - When the consignor receives the sales invoices, the following entries have to be recorded: • Recording the total sales as follows: The agent …… Consignment to the agent…. ××× ××× To record receiving the sales invoice indicating selling goods amounted …….by the agent …… • For expenses incurred by the consignee as well as bad debts suffered by him on behalf of the consignor, debit Consignment Account and credit Consignee Account: Consignment to the agent…… ××× ××× The Agent ……… To record the expenses incurred by the agent … • For commission due to the Consignee, debit Consignment Account and credit the consignee. Consignment to the agent …… ××× ××× The Agent …….. To record the commission entitled to the agent …… (the amount of consignment sales the commission rate) • Receiving the remaining balance at the consignee (agent) Cash ××× The Consignee……. ××× To record receiving the remaining amount for the consignment sales by the consignee • For the goods that may remain unsold debit the Inventories on Consignment Account and credit Consignment Account - 13 - Inventories on Consignment Consignment to the agent…….. ××× ××× To record the remaining unsold consignment merchandise at the agent … Notes: a. The cost of unsold goods at the agent must include its part from all the expenses incurred by the consignor, including the freight charges and any other expenses that the consignor incurred. b. Inventories on Consignment Account is an asset; it w be shown in the balance sheet of the consignor, and next year it will be transferred to the debit of the Consignment Account. • At this stage, the Consignment Account will reveal profit or loss. The profit or loss will be transferred to the income summary by debit to the Consignment Account. Consignment to the agent….. Income Summary ××× ××× To recognise the profits resulting from the consignment sales by the agent …… OR Income Summary (Profit and losses account) ××× Consignment to the agent …….. ××× To recognise the losses resulted from the consignment sales by the agent …… The Important ledger accounts appear as follows: Consignment out- the consignee…….. account To Goods sent on consignment ×× By The Agent … (Sales ××× × Proceeds) - 14 - To cash (Consignment expenses) ×× By Inventories Consignment To the agent …… ( the agent expenses and bad debts) To the agent .. (Commission) To Income Summary (or Profit and Losses account) on ××× × × ×× ××× ××× The Consignee Account Year Year To Consignment out- the××× agent. By Notes receivables ××× By Consignment out- × the agent (Expenses and bad debts) By Consignment out- × the agent…. ( Commission) By cash ×× ××× ××× Goods sent on Consignment Account Year Year To Income Summary ××× (Or Trading Account) By Consignment out- the ××× agent…… ××× ××× Inventories on Consignment Account Year Year To Consignment out- the ××× agent… Year To Balance B/D ××× - 15 - By Balance ××× C/D The following example illustrates the transactions and the main ledger accounts required to present detailed information on the consignment. Example 1 On 1st Jul. 2018, Ahmed sent to Kareem goods costing 50,000 and spent 1,000 on packing etc. On 3rd Jul. 2018, Kareem received the goods and sent his acceptance to Ahmed for 30,000 payable in 3 months. Kareem spent 2,000 on freight and cartage, 500 on the godown rent and 300 on insurance. On 31st Dec. 2018, Kareem sent his Account Sales (along with the amount due to Ahmed) showing that 4/5 of the goods had been sold for 55,000. Kareem is entitled to a commission of 10%. One of the customers turned insolvent and could not pay 600 due from him. Required: To record these transactions in Ahmed’s books. The Solution First: Journal Entries: - Open Consignment Account: 1st Jul. Consignment out- Kareem 50000 Goods Sent on Consignment 50000 To record sending goods to the agent Kareem - Recording the expenses incurred by the consignor: 1st Jul. Consignment out- Kareem Bank 1000 1000 To record the expenses paid to send the merchandise to the agent Kareem - 16 - - Receiving a note payable from the Consignee Kareem: 3rd Jul. Notes Receivable The Agent Kareem 30000 30000 To record receiving a note receivable from the agent Kareem - Remember that Kareem accepted a note payable to the consignor Ahmed on 3rd Jul. that matures after three months. Therefore, Kareem has to pay this amount to Ahmed by 3rd Oct. The entry to record collecting the amount shall be as follows: 3rd Oct. Cash 30000 Notes Receivable 30000 To record collecting the amount of a note receivable from the agent Kareem - When the consignor receives the sales invoice, the following entries have to be recorded: • Recording the total sales as follows: 31st The agent Kareem Dec. Consignment out- Kareem 55000 55000 To record receiving the sales invoice indicating selling goods amounted 55000 by the agent Kareem • Record deducting the Consignee Kareem's expenses and bad debts from the Consignment out- Kareem's account 31st Consignment out- Kareem Dec. The Agent Kareem 3400 3400 To record the expenses incurred by the agent Kareem • Recording the commission entitled to the agent Kareem: - 17 - 31st Consignment out- Kareem Dec. The Agent Kareem 5500 5500 To record the commission entitled to the agent Kareem (55000 × 10%) • Receiving a cheque indicates the remaining balance at the agent Kareem 31st Cash Dec. 16100 16100 The Agent Kareem To record receiving the remaining amount for the consignment sales by the agent Kareem • Recording the unsold goods: 31st Dec. Inventories on Consignment Consignment out- Kareem 10600 10600 To record the remaining unsold consignment merchandise at the agent Kareem The cost of unsold goods at the agent Kareem was calculated as follows: 1/5 of the cost to the consignor 1/5 of expense incurred by the consignor 1/5 of the freight charge Total 50000× 1/5= 10000 1000× 1/5 = 200 2000× 1/5= 400 10600 • Recognising the profits from goods on Consignment out- Kareem: 31st Dec. Consignment out- Kareem Income Summary To recognise the profits resulting from the consignment sales by the agent Kareem Second: the main ledger accounts: - 18 - 5700 5700 Consignment out- Kareem Account 2018 1/7 1/7 31/12 31/12 31/12 2018 on 50000 31/12 To Goods sent Consignment To Cash (Consignment expenses) To Kareem ( the agent expenses and bad debts) To Kareem (Commission) To Income Summary (or Profit and Losses account) 1000 31/12 By Kareem (Sales 55000 Proceeds) By Inventories on 10600 Consignment 3400 5500 5700 65600 65600 Goods sent on Consignment Account 2018 31/12 To Summary (Or Account) 2018 Income 50000 31/12 By Consignment Kareem Trading 50000 out 50000 50000 Inventories on Consignment Account 2018 31/12 1/1/2019 To Consignment outKareem To Balance B/D 2018 10600 31/12 By Balance C/D 10600 12600 The Consignee Kareem’s Account 2018 31/12 To Consignment out- 55000 Kareem 2018 3/7 31/12 55000 - 19 - By Notes receivables 30000 By Consignment out- 3400 Kareem (Expenses and bad debts) By Consignment out- 5500 Kareem ( Commission) By Cash 16100 55000 7. Valuation of Inventories The principle is that inventories should be valued at cost or net realisable value, whichever is lower, the same principle as is practised for preparing final accounts. In the case of consignment, cost means not only the cost of the goods as such to the consignor but also all expenses incurred until the goods reach the consignee's premises. Such expenses include packaging, freight, cartage, insurance in transit, etc. However, expenses incurred after the goods have reached the consignee's godown (such as go down rent, insurance of godown, delivery charges) are not treated as part of the purchase cost for valuing inventories on hand. That is why in the case given above, inventories have been valued, ignoring godown rent and insurance. Sometimes an examination problem states only that the consignor’s expenses amounted to such and such amount and that consignee spent so much. If details are not available for valuing inventories, the expenses incurred by the consignor should be treated as part of the cost, while those incurred by the consignee should be ignored. If the expected selling price of inventories on hand is lower than the cost, the value put on the inventories should be expected net selling price only, i.e. expected selling price, less delivery expenses, etc. 8. Goods Invoiced Above Cost Sometimes the proforma invoice is made out at a value higher than the cost, and entries in the books of the consignor are made out on that basis - even the inventories remaining unsold will initially be valued based on the invoice price. However, it must be remembered that the profit or loss can be ascertained only if sale proceeds (plus) inventories - 20 - on hand, valued on cost basis, is compared with the cost of the goods concerned together with expenses. Hence, if entries are first made on an invoice basis, the effect of the loading (i.e., amount added to arrive at the invoice price) must be removed by additional entries. Example 2: Suppose in the example given above, if the invoice is cost plus 20%, i.e., 60,000 for the goods sent to Kareem. The entries will be as follows: 1/7 Consignment out- Kareem Goods Sent on Consignment To record sending goods to the agent Kareem (50000+50000×20%) 1/7 Consignment out- Kareem Cash To record the expenses paid to send the merchandise to the agent Kareem 3/7 Notes Receivable The Agent Kareem To record receiving a note receivable from the agent Kareem Cash 3/10 Notes Receivable To record collecting the amount of a note receivable from the agent Kareem 31/12 The agent Kareem Consignment out- Kareem To record receiving the sales invoice indicating selling goods amounted 55000 by the agent Kareem Consignment out- Kareem 31/12 The Agent Kareem To record the expenses incurred by the agent Kareem - 21 - 60000 60000 1000 1000 30000 30000 30000 30000 55000 55000 3400 3400 31/12 Consignment out- Kareem The Agent Kareem 5500 5500 To record the commission entitled to the agent Kareem (55000 × 10%) 31/12 Cash 16100 16100 The Agent Kareem To record receiving the remaining amount for the consignment sales by the agent Kareem 31/12 Inventories on Consignment Consignment out- Kareem To record the remaining unsold consignment merchandise at the agent Kareem 31/12 Consignment out- Kareem Income Summary 12600 12600 5700 5700 To recognise the profits resulting from the consignment sales by the agent Kareem You can see that except for the difference in the amounts in entries related to sending the goods on Consignment out- Kareem and the entry to record the inventory of goods on consignment at the Consignee Kareem. The difference in the first entry amounts $10000 ($60000 $50000), and the later entry amounts $2000 ($12600 - $10600). In this case, where the goods on consignment are loaded on a value that exceeds the cost; therefore, two additional entries are required to remove the effect of loading as follows: 31/12 31/12 Goods sent on consignment Consignment out- Kareem To remove the loading to the consignment merchandise sent to the agent Kareem Consignment out- Kareem - 22 - 10000 10000 2000 Inventory Reserve 2000 To remove the unrealised profit from overvaluing the end of period inventory at the Consignee Kareem The Consignment Account will now reveal a profit of $5,700, the same as before. It will be transferred to the income summary (profit and losses account). Similarly, entry given in 8 above will be made to transfer the balance in the Goods sent on Consignment Account (now against $5,000) after entry in (a) above to the credit of Trading Account. The accounts (except for Kareem, whose account will be the same as already shown) are given below: Consignment – out- to Kareem 2018 1/7 To Goods sent on Consignment 1/7 To Cash (Consignment expenses) To Kareem ( the agent 31/12 expenses and bad debts) To Kareem (Commission) 31/12 To Inventory reserve (Adjustment) To Income Summary (or 31/12 Profit and Losses account) 2018 60000 31/12 By Kareem (Sales 55000 Proceeds) 1000 31/12 By Inventories on 12600 Consignment 3400 By Goods sent on 10000 Consignment (Loading) 5500 2000 5700 65600 65600 Goods sent on Consignment Account 2018 2018 31/12 To Consignment out- 10000 By Consignment Kareem Kareem 31/12 To Income Summary 50000 31/12 (Or Trading Account) 60000 - 23 - out- 50000 60000 Inventories on Consignment Account 2018 31/12 1/1/2019 To Consignment outKareem To balance b/d 2018 12600 31/12 By Balance C/D 12600 12600 Inventory Adjustment Account 2018 31/12 To balance c/d 2018 2000 31/12 By Consignment Kareem 2019 1/1 By balance b/d out- 2000 2000 The last two accounts will be carried forward to the following year, and their balance will then be transferred to the Consignment Account – $12,600 on the debit side and $2,000 on credit. This year in the balance sheet, the net amount of $10,600 will be shown on the assets side as shown below: Inventories on consignment 12,600 Less: Reserve 2,000 10600 What would be the situation if the commission to Kareem includes the del-credere commission also? In that case, Kareem would not be able to charge the bad debt of $600 to Ahmed; he will have to bear the loss himself. You can see that then the profit on consignment will be $6300 (The original profit of 5700 + the bad debts 600). In this regard, it is to be noted that when del-credere commission is paid to the consignee, the consignee account is debited in the books of the - 24 - consignor for both cash and credit sales. But if no such del-credere commission is paid, then the consignee account cannot be debited for credit sales, and in that case, the following entry is passed in the books of the consignor for credit sales. Consignment Trade receivables Consignment out- the consignee.. ××× ××× 9. Abnormal Loss If any accidental or unnecessary loss occurs, the proper thing to do is to find out the cost of the goods thus lost and then to credit the Consignment Account and debit income summary (the Profit and Loss Account). This will enable the consignor to know what profit would have been earned had the loss not occurred. Suppose 1,000 sewing machines costing $250 each are sent on consignment basis, and $10,000 are spent on freight etc., 20 machines are damaged beyond repair. The amount of loss will be: Cost = Share of Expenses = 20 unit × $250 2× $10000 1000 Unit $5000 $200 $5200 This amount should be credited to the Consignment Account and debited to the income summary (Profit & Losses Account). If any amount, say, $4,000, is received from the insurers, then debit to the Income Summary will be only $1,200. But the credit to the Consignment Account will still be $5,200. $4,000 will have been debited to the Cash Account. You should have noted that abnormal loss is valued just like inventories in hand. Also, you should be careful while valuing goods lost in transit and goods lost in consignee's warehouses. Both are abnormal loss, but - 25 - in the case of the former consignee, non-recurring expenses are not to be included, whereas it is to be included in the the latter casetter. 10. Normal Loss If some losses were essential and unavoidable, they would be spread over the entire consignment while valuing inventories. The total cost plus expenses incurred should be divided by the quantity available after the normal loss to ascertain the cost per unit. Suppose 1,000 kg of apples are consigned to a wholesaler, the cost being $3 per kg, plus $400 of freight. It is concluded that a loss of 15% is unavoidable. The cost per kg will be ($3000+ $400)/850 kg = $4/kg. If the inventory is 100 kg, its value will be $400. 11. Commission The commission is the remuneration paid by the consignor to the consignee for the services rendered to the former for selling the consigned goods. The consignor can provide three types of commission to the consignee, as per the agreement, either simultaneously or in isolation. They are: 11.1 Ordinary Commission The term commission simply denotes ordinary commission. It is based on a fixed percentage of the gross sales proceeds made by the consignee. It is given by the consignor regardless of whether the consignee is making credit sales or not. This type of commission does not give any protection to the consignor from bad debts and is provided on total sales. - 26 - 11.2 Del-Credere Commission To increase the sale and encourage the consignee to make credit sales, the consignor provides an additional commission generally known as del-credere commission. This additional commission, when provided to the consignee, gives protection to the consignor against bad debts. In other words, after providing the del-credere commission, bad debts are no more the loss of the consignor. It is calculated on total sales unless there is an agreement between the consignor and the consignee to only provide it on credit sales. 11.3 Over-Riding Commission It is an extra commission allowed by the consignor to promote sales at a higher price than specified or encourage the consignee to put hard work into introducing new products in the market. Depending on the agreement, it is calculated on total sales or the difference between actual sales and sales at invoice price or any specified price. 12. Return of Goods From the Consignee Consigned goods can be returned by the consignee for many reasons like poor quality or not up to the specimen or destroyed in transit etc. In such a situation, the question that arises is the valuation of returned goods. Consigned goods returned by the consignee to the consignor are valued at the price it was consigned to the consignee. Expenses incurred by the consignee to send those goods back to the consignor are not considered while valuing it because only those expenses are included in the cost of goods, which help bring the goods into present location and condition, i.e. the saleable condition. - 27 - 13. Account Sales An account sale is the periodic summary statement sent by the consignee to the consignor. It contains details regarding: (a) sales made, (b) expenses incurred on behalf of the consignor, (c) commission earned, (d) unsold inventories left with the consignee, (e) advance payment or security deposited with the consignor and the extent to which it has been adjusted, (f) balance payment due or remitted. It is a summary statement and is different from the Sales Account. 14. Accounting Books of the Consignee The consignee is not concerned when goods are consigned to him or when the consignor incurs expenses. He is concerned only when he sends an advance to the consignor, makes a sale, incurs expenses on the consignment and earns his commission. He debits or credits the consignor for all these, as the case may be. The entries to record consignment goods and their related transactions in the consignee's books are as follows: - - When the consignee make sales Cash/ accounts receivable ××× Consignment – in – the consignor….. ××× To record sales from the consignment goods For expenses incurred and his commission Consignment – in – the consignor ….. ××× Cash ××× To record loading the expenses related to the goods on consignment - 28 - - Record the advance paid to the consignor, if any: Consignment – in – the consignor ..….. Cash ××× ×× To record payment of an advance for the consignor….. - In the case of writing off bad debts (the consignee is granted a normal commission): Bad debts ×× Accounts receivables – on consignment To record writing off bad debts of the consignment customers Consignment – in – the consignor ..….. Bad debts To deduct the bad debts from the balance entitled to the consignor……. ×× ×× ×× Note that if the consignment agreement states that the consignee is entitled to a del-credere commission, therefore, he will incur any losses result from writing off bad debts. In this case, the entries will be as follows: Bad debts ×× Accounts receivables – on consignment To record writing off bad debts of the consignment customers Commission ×× Bad debts To close the bad debts from the consignment customers ×× ×× Example 3 On 1st Jul. 2018; Ahmed sent to Kareem merchandise costing $50000 and spent $1000 on packing etc. On 3rd Jul. 2018, Kareem received the - 29 - goods and sent his acceptance to Ahmed to write a note payable of $30000, dues after three months. Kareem spent $2000 on freight and cartage, $500 on warehousing rent and $300 on insurance. On 31st Dec. 2018, he sent the Account Sales (along with the amount due to Ahmed) showing that 4/5 of the goods had been sold for $55,000, of which $15000 were sold on credit, and the remaining sold in cash. Kareem is entitled to a commission of 10%. One of the customers turned insolvent and could not pay $600 due from him. Instructions: To record the necessary journal entries in the consignee’s books. The Solution - On sending the acceptance of a note payable to Ahmed: 3rd July Consignment – in- the consignor Ahmed Notes Payable 30000 30000 To record accepting a note payable as advance for consignment –in- to the consignor Ahmed - Payment of expenses related to the consignment– in Ahmed: 3rd Jul. Consignment – in- the consignor Ahmed Cash 2800 2800 To record payment of freight, cartage, and warehousing rent of consigned goods - On 3rd Oct., paying the notes payable to the consignor Ahmed: 3rd Oct. Notes payable 30000 Cash 30000 To record paying the note payable to the consignor Ahmed - Record the sales from consigned goods: - 30 - Over Cash the Accounts receivables – on consignment period 40000 15000 Consignment – in- the consignor Ahmed 55000 To record sales from the consigned merchandise - Recognising the bad debts of consignment-in sales: 31st Cash 14400 Dec. Bad debts 600 Accounts receivable – on consignment 15000 To record collecting consignment-in credit sales and writing off $600 st 31 Consignment – in- the consignor Ahmed Dec. Bad Debts 600 600 To close the bad debts resulted from consigned goods Note that it is possible to gather the above two entries in a sole entry as follows: 31st Cash Dec. Consignment – in- the consignor Ahmed (Bad debts) Accounts receivable- on consignment 14400 600 15000 To record collecting consignment-in credit sales and writing off $600 - Deducting the commission from the dues of the consignor Ahmed: 31st Consignment – in- the consignor Ahmed Dec. Earned Commission 5500 5500 To record the commission earned on consigned goods ($55000× 10%) - Settling the consignor Ahmed account and paying the remaining balance - 31 - 31st Consignment – in- the consignor Ahmed Dec. Cash 16100 16100 To record paying the residual balance entitled to the consignor Ahmed Also, the Consigner Ahmed account appears as follows: Consignment – in- the consignor Ahmed 2018 --- 40000 To Cash To Accounts receivables – 15000 on consignment 2018 3/7 3/7 By Notes Payable By Cash 30000 2800 31/12 By Bad debts 600 31/12 By Earned Commission 5500 31/12 By Cash (bal. fig.) 16100 55000 55000 Now assume that the consignment agreement entitles the Consignee Kareem to receive a del-credere commission of 10%. In this case, the commission that was computed covers both the consignee rewards on sales and any bad debts as well. In that case, the debit side should be to the Commission Earned Account, whose net balance will then be $4,900, and he will have to pay $16,700 to Ahmed. Therefore, the entries will be the same except for two entries as follows: - Recognising the bad debts of consignment-in sales: 31st Cash Dec. Bad debts Accounts receivable– on consignment To record collecting consignment-in credit sales and writing off $600 st 31 Earned Commission Dec. Bad Debts To close bad debts resulted from selling the consigned merchandise - 32 - 14400 600 15000 600 600 - Settling the consignor Ahmed account and paying the remaining balance 31st Consignment – in- the consignor Ahmed Dec. Cash 16700 16700 To record paying the residual balance entitled to the consignor Ahmed As the consignor Ahmed account changes to be as follows: Consignment – in- the consignor Ahmed 2018 -To Cash -To receivablesconsignment 2018 40000 3/7 Accounts 15000 3/7 By Notes Payable By Cash 30000 2800 on 31/12 By Earned Commission 31/12 By Cash (bal. fig.) 55000 5500 16700 55000 15. Advance by the Consignee Vs Security Against the Consignment Generally, the consignor insists the consignee for some advance payment for the goods consigned at the time of delivery of goods. This advance payment is adjusted in full against the amount due by the consignee on account of the goods sold. However, if the advance money deposited by the consignee is in the form of security against the goods consigned, then the full amount is not adjusted against the amount due by the consignee to the consignor on account of goods sold in case there are any unsold inventories left with the consignee. In that case, proportionate security - 33 - regarding unsold goods is carried forward until the respective goods held with the consignee are sold. An overview of the consignment transaction between consignee and consignor can be depicted with the help of the following chart: Example 4 Alessandra consigned 1,000 radio sets costing $900 each to AnnaMaria, her agent on 1st Jul. 2018. Alessandra incurred the following expenditure on sending the consignment. Freight $7650 Insurance $3250 - 34 - AnnaMaria received the shipment of 950 radio sets. An account sale dated 30th Nov. 2018 showed that 750 sets were sold for $900000, and AnnaMaria incurred $10500 for carriage. AnnaMaria was entitled to commission 6% on the sales affected by her. She incurred expenses amounting to $2500 for repairing the damaged radio sets remaining in the inventories. Alessandra lodged a claim with the insurance company that was admitted at $35000. Instructions: To prepare the consignment- out Account and AnnaMaria’s Account in the books of Alessandra. The Solution In the books of Alessandra The Consignee – Annamaria account 2018 30/11 2018 To consignment- 900000 30/11 By consignment- out Annamaria (Sales) out Annamaria Carriage Repairs Commission By Cash 900000 900000 10500 2500 54000 67000 833000 900000 - 35 - The Consignment- out - Annamaria 2018 1/7 1/7 To Goods sent consignment To cash Freight Insurance 2018 900000 July By Insurance company 35000 on 30/11 By Annamaria 900000 7650 3250 10900 30/11 By Income Summary 10545 30/11 To the Annamaria Carriage Repairs Commission (Profits and losses Account) – abnormal loss By consignment 184391 Inventories consignee 10500 2500 5400 67000 Income (Profits account) Summary and losses 152036 1129936 1129936 Note: We assumed that the agent had remitted the amount due from her. Working notes: a. The abnormal loss is calculated as follows: Cost to the consignor Add: proportionate expenses incurred by the consignor Less: Insurance claim (compensation) - 36 - 50 units $10900 × $900 × 50 unit 1000unit 45000 545 45545 (35000) 10545 Remember that the damage occurred before the consignee receives the shipment. Thus, it is necessary to compute its part from the consignor expenses. b. Valuation of inventory of the consigned goods at Annaamaria warehousing is calculated as follows: Cost to the consignor 200 units Add: proportionate expenses incurred by the consignor $10900 × Add: The consignee expenses (Carriage) $10500 × $900 180000 200 unit 1000unit 200 unit 950 unit 2180 2211 184391 Example 5 Dora Milk Foods Company, located in Cairo, sent to Elhamed Stores, in Assiut, 5000 kgs of baby food packed in 2000 packets of net weight 1 kg and 6000 packets of net weight 1/2 kg for sale on a consignment basis. The consignee’s commission was fixed at 5% of sale proceeds. The cost price and selling price of the product were as under: 1 kg $10 $15 Cost Price Selling price ½ kg $6 $7 The consignment was booked on a freight "To Pay" basis, and freight charges came to 2% of selling value. One case containing 50 1 kg tins were lost in transit, and the transport carrier admitted a claim of $450. At the end of the first half-year, the following information is gathered from the “Account Sales” sent by the consignee: - 37 - • Sale proceeds: 1500 of 1 kg packets and 4000 of 1/2 kg packets. • Store rent and insurance charges amounted to $600. Instructions a. Compute the value of closing inventory on consignment. b. Prepare the consignment –out account and the consignee's account in the books of Dora Milk Food Company, assuming that the consignees had paid the amount due from him. The Solution Dora Milk Foods Company: Consignment- out Elhamed stores To Goods sent on consignment 2000, 1 kg. packets 6000 ½ kg. packets By the Consignee Elhamed Stores 1500, 1 kg 22500 4000, ½ kg 28000 20000 36000 56000 To the Consignee Elhamed stores 1440 Freight 600 Rent & Insurance 2225 Commission By Insurance company 4565 To Income Summary (Profits and losses Account) By Income Summary (Profits and losses Account) – abnormal loss 7365 By consignment Inventories 67930 - 38 - 50500 450 65 16915 67930 The Consignee Elhamed stores Account To consignment- out 50500 By consignment- Elhamed stores out Elhamed stores: Freight 1440 Rent & Insurance 600 2525 4565 By Cash 50500 45935 50500 Working notes: a. Sale value of total consignment: 2000 unit, 1 kg packet × $15 30000 6000 unit, ½ kg packet × $7 42000 Total Sales 72000 b. Freight: 2% of above 1440 2% of the sales = 2% × 72000 = 1440 c. Inventories at the end of the six months 450 unit, 1 kg packet × $10 (selling price 6750 4500 2000 unit, ½ kg packet × $6 (selling price 14000) 12000 16500 Add: freight charge 2% of selling price 2% × (6750 + 14000) 415 The inventory cost 16915 d. Loss in transit: Cost of 50 units 1 kg packet (50 unit × $10) - 39 - 500 Add: proportion of the freight charges (2% × $750 selling 15 price) 515 Les: claim from the insurance company Loss (450) 65 Example 6 Medhat Trading Company purchased 10000 TV of which costing $100 each. Six thousand TVs were sent on consignment to Hayah Company at the selling price of $120 per TV. The consignor paid $3000 for packaging and freight. Hayah sold 5000 TVs at $125 per TV and incurred $1000 for selling expenses and remitted $500000 to Cairo on account. They are entitled to a commission of 5% on total sales plus a further 20% commission on any surplus price realised over $120 per TV. Owing to a fall in market price, the value of the inventories of TVs in hand is to be reduced by 10%. Instructions - Prepare the Consignment- out Account. - Prepare the Consignor account in the books of Hayah Company. The Solution Books of the Consignee: The Consignor Medhat Trading Company Account To consignment- out Medhat 37250 By Cash 625000 Trading Company To Cash 500000 To balance c/d 87750 625000 - 40 - 625000 Books of the consignor: Consignment- out Hayah Company account To Goods sent on 7200000 By the consignee 625000 consignment (6000 Units Elhamed Store ۱$×20) To Cash 3000 To the Consignee Hayah By Goods sent on 120000 Company consignment 1000 Expenses (loading) 36250 Commission 37250 Inventory Reserve 18000 (unrealised profits) To Income Summary (Profits and losses Account) 75200 By consignment 108450 inventories 853450 853450 Working Notes: a. The commission entitled to the consignee is calculated as follows: 5% × $625000 20% × $25000 31250 5000 36250 b. The inventory at the end of the period is computed as follows: 1000 TV × $120 120000 Add: Proportionate expenses= $3000 × 1000 unit 6000 unit 500 120500 Less: 10% reduction due to fall in market price (10% × 120500) = (12050) 108450 Example 7 ElSalam Stores consigns 1000 units of goods costing $100 each to Elboghdady Shop. - 41 - ElSalam Stores paid the following expenses in connection with consignment: Carriage 1000 Freight 3000 Loading charges 1000 Elboghdady Shop sells 700 units at $140 per unit and incurs the following expenses: Clearing charges 850 Warehousing and storage 1700 Packing and selling expenses 600 It is found that 50 units have been lost in transit, and 100 units are still in transit. Elboghdady Shop is entitled to a commission of 10% on gross sales. Instructions: Draw up the Consignment Account and Elboghdady’s Account in the books of ElSalam Stores. The Solution The books of ElSalam Stores The Consignee Elboghdady Shop Account To consignment- out Elboghdady Shop 98000 98000 - 42 - By consignmentout Elboghdady shop By balance c/d 12950 85050 98000 Consignment- out Elboghdady shop account To Goods sent on 100000 By the Consignee consignment Elboghdady Shop To Cash 5000 To the Consignee By Income Elboghdady Shop summary (Loss in Transit) Expenses 3150 (50 unit× $105 each) Commission 9800 12950 By consignment inventories In hand (150 unit× 15900 $106) In transit (100 unit 10500 × $105) To Income Summary 11700 (Profits and losses Account) 129650 98000 5250 26400 129650 Working Notes: a. Consignor’s expenses on 1000 units amounted to $5000; it comes to $5 per unit. The cost of units lost will be computed at $105 per unit. b. Elboghdady shop has incurred $850 on clearing 850 units, i.e., $1 per unit; while valuing closing inventories with the agent, $1 per unit has been added to units in hand. Example 8 Bebo consigned goods to Besheer to be sold at invoice price, representing 125% of the cost. Besheer is entitled to a commission of 10% on sales at invoice price, and 25% of any excess realised over invoice price. The expenses on freight and insurance incurred by Bebo - 43 - were $10000. The sales report received by Bebo shows that Besheer sold 75% of the consignment, amounting to $100000. His selling expenses to be reimbursed were $8000. Ten percentage of consignment goods of which valued at $12500, were destroyed in the fire at the Cairo warehousing and the insurance company paid $12000 net of salvage. Besheer remitted the balance in favour of Bebo. Instruction: Prepare consignment account and the account of Besheer in the books of Bebo, along with the necessary calculations. The Solution The books of Bebo Consignment- out Besheer account To Goods sent on 125000 By Goods sent on consignment consignment To Cash 10000 To the consignee Besheer By Income Expenses Summary (Profits 8000 Commission and losses Account) 10937 – abnormal loss 18937 By the consignee Besheer To inventory reserve consignment 3750 By inventories By Income summary (Profits and Losses account) 157687 - 44 - 25000 11000 100000 20250 1437 157687 The Consignee Besheer Account To consignment- out Besheer 100000 By consignment- out Besheer shop By consignment- out Besheer shop By Cash 100000 8000 10937 81063 100000 Working Notes: a. Calculation of value of goods sent on consignment: Abnormal Loss at Invoice price = 12500 Abnormal loss as a percentage of total consignment = 10%. Hence the value of goods sent on consignment = $12500 X 100/ 10= 125000 b. Calculation of abnormal loss (10%): Abnormal Loss at Invoice price = 12500 Abnormal Loss at cost = $12500 X 100/125 = 10000 Proportionate expenses of Bebo (10 % of $10000) = 1000 c. `Calculation of closing Inventories (15%): Bebo’s Basic Invoice price of the consignment 125000 Bebo’s expenses on consignment 10000 135000 Value of closing inventory (15% × 135000) 20250 Unrealised profits in closing Inventories = 18750 X 25/125 (Where $18750 = (15% of 125000) is the basic invoice price 3750 of the goods sent on consignment) d. Calculation of commission: Invoice price of the goods sold = 75% × 125000 = 93750 Excess of selling price over invoice price =(100000- 93750) = $6250 Total Commission = 10%× 93750+ 25% × 6250 - 45 - = 9375 + 156250 = 10937.5 Example 9 Elhoda Company purchased 10000 metres of cloth for $200000, of which 5000 metres were sent on consignment to Assiut Company at the selling price of $30 per metre. Elhoda paid $5000 for freight and $500 for packing etc. Assiut Company sold 4000 metres at $40 per metre and incurred $2000 for selling expenses. Assiut is entitled to a commission of 5% on total sales proceeds plus a further 20% on any surplus price realised over $30 per metre. The agent sent a cheque that amounted to $130000, and the remaining balance still unpaid until the end of the fiscal year. Owing to a fall in market price, the Inventories of cloth in hand will be reduced by 10%. Required: Prepare the consignment – out account and the consignee Assiut company account in the books of Elhoda Company. The Solution In the books of Elhoda Company The Consignee Assiut Company Account To consignment- out Assiut Company 160000 By Consignment- out 2000 Assuit Company (expenses) By Consignment- out Assuit 16000 Company (Commission) By Cash 130000 By balance c/d 12000 160000 160000 - 46 - Consignment- out Assiut Company’s account To Goods sent on consignment 150000 By Goods sent on consignment (cancellation of loading) 5500 To Cash (Freight and Packing) To the Consignee Assiut Company Expenses 2000 Commission 16000 50000 By the Consignee 160000 Assiut Company (Sales) 18000 To inventory reserve 9000 3750 By consignment 27990 inventories To Income summary 55490 (Profits and Losses account) 237990 237990 Working Notes: a. Calculation of commission payable to Assiut Company: Total sale proceeds of Assiut Company Surplus proceeds realised over $30 per metre [4000 x LE (40-30)] 160000 4000 Commission: 5% of total sale proceeds (5% × 160000) 8000 20% of surplus (20% × 40000) 8000 16000 b. Inventories on Consignment: Cost of consignment Inventories (1000 mtrs۳$×0) 30000 Add: Expenses of the consignor (5500× 20%) 1100 31100 - 47 - Less: Reduction of 10% due to the fall in market price (10%× 31100) (3110) 27990 c. Inventories on Consignment: Cost of consignment Inventories (1000 mtrs۳$×0) 30000 Add: Expenses of the consignor (5500× 20%) 1100 31100 Less: Reduction of 10% due to the fall in market price (10%× 31100) (3110) 27990 d. Loading ( $10 x 1000 mtrs) – 10% of ( $10 x 1000 mtrs) - 48 - 9,000 CHAPTER TWO ACCOUNTING FOR CLUBS AND SOCIETIES - 49 - Chapter Two Accounting For Clubs And Societies Learning Objectives: After studying this chapter, you should be able to understand: • Understand the concept of clubs & societies. • Comparison between businesses and clubs/societies. • Know the accounting requirements of clubs and societies. • Prepare the financial statements for club and societies • Understanding the concepts of surplus/deficit and the accumulated fund. • Measure the profit or loss of each activity carries out by a club/society. 1. Introduction: Accounting practice should always reflect the actual and likely needs of the organisation concerned and-for, the most part, those needs since it is a waste of time producing information that no one wants. This is as true of clubs and societies and other non-for-profits organisations as it is of any other organisation. If all that is needed is a record of cash currently available, then simple cash and bank accounts are sufficient. However, the members of an organisation-even quite a small one-may feel that they need something more than just a cash balance at the end of the day, week, month or year. They may want to know, for example, exactly where the money has come from over the past year and on what it has been spent. - 50 - Also, a club or society does not have to be larger for its members to see the importance of knowing what income, such as subscriptions for the year, has been 'earned' (whether received or not) by the club and what expenditure has been incurred (again, whether actually paid or not). In other words, they may well see a need for an account that follows all the principles of a profit and loss, though not described as such. 2. Meaning and Characteristics of Not-for-Profit Organisation Not-for-Profit Organisations refer to the organisations used for the welfare of society and are set up as charitable institutions that function without any profit motive. Their main aim is to provide service to a specific group or the public at large. Normally, they do not manufacture, purchase or sell goods and may not have credit transactions. Hence they need not maintain many books or accounts (as the trading concerns do) and Trading and Profit and Loss Account. The funds raised by such organisations are credited to the capital fund or the general fund. The major sources of their income usually are subscriptions from their members' donations, grants-in-aid, income from investments, etc. The main objective of keeping records in such organisations is to meet the statutory requirement and help them exercise control over the utilisation of their funds. They also have to prepare the financial statements at the end of each accounting period (usually a financial year), ascertain their income and expenditure and the financial position, and submit them to the statutory authority called Registrar of Societies. The main characteristics of such organisations are: - 51 - • Such organisations are formed to provide service to a specific group or public at large, such as education, health care, recreation, sports, and so on, without considering caste, creed, and colour. Its sole aim is to provide service either free of cost or at nominal cost, and not profit. • These are organised as charitable trusts/societies, and subscribers to such organisations are called members. • Their affairs are usually managed by a managing/executive committee elected by its members. • The main sources of income of such organisations are (i) subscriptions from members, (ii) donations, (iii) legacies, (iv) grant-in-aid, (v) income from investments, etc. • The funds raised by such organisations through various sources are credited to the capital fund or the general fund. • The surplus generated in the form of excess income over expenditure is not distributed amongst the members. It is simply added to the capital fund. • The Not-for-Profit Organisations earn their reputation on the basis of their contributions to the welfare of the society rather than on the customers’ or owners’ satisfaction. • The accounting information provided by such organisations is meant for the present and potential contributors and to meet the statutory requirement. The following table illustrates a comparison between for-profit entities and not-for-profit (clubs and societies) concerns. - 52 - For-profit entities Clubs and societies Set up to earn profit by selling goods Set up to promote activities of interest to and services its members (cultural, recreational, intellectual, sports etc.) Sell goods and services at more than No value placed on the normal facilities cost price to earn profit Business financed by provided to members owners' Financed by monthly or yearly equity, most of which invested in subscriptions from members setting up the business Money received and paid are Money received and paid are recorded in recorded in the cash book receipts and payments account Trading account (first part of the If the club runs a restaurant, bar or income statement) to calculate gross canteen, a trading account is prepared to profit or gross loss as Sales Revenue – Cost of Sales calculate profit from the restaurant, bar or canteen as Trading Revenue- Trading Expenses Main source of revenue is sales or Main source of income is subscriptions fees received from members Profit and loss account (second part Income and Expenditure account of the income statement) prepared to prepared to calculate surplus or deficit calculate the net profit as: as: Net Profit= Gross profit + Other Surplus (deficit) = Revenues Income - Expenses Expenditure Balance Sheet equation as Balance Sheet equation as Assets = Owners Equity + Assets = Accumulated fund + Liabilities Liabilities The Main revenues resources in the for-profit units and not-for-profit units: - 53 - For-profit units Clubs and Societies Sale of goods Subscriptions Receipts from services Entrance fees Rent received Profit from sale or refreshments Commission received Profit from activities Discount received Interest received Interest received Donations Profits on disposal 3. Receipts and Payments Accounts Nothing more is needed for many small clubs and societies than an accurate record of cash and bank transactions. It is normal, once a year, to prepare a year-end summary of these transactions, and this is known as a receipts and payments account. A receipts and payments account is nothing more nor less than a summarised cash and bank account, and it follows all the rules of cash and bank accounts. This means that the summarised receipts are listed as debits and the summarised payments as credits- either in normal ledger format or as a vertical statement. Whichever way it is presented, a receipts and payments account starts with the opening balances of cash and bank at the beginning of the year and ends with the closing balances at the end of the year. If cash has been drawn from or paid into the bank account, there will be corresponding entries in both cash and bank accounts. These will, of course, be self-cancelling when the accounts are combined and will not appear in the receipts and payments account. The title 'receipts and payments' account is essential since this is precisely what it is a summary of actual cash receipts and actual cash payments. The account is not concerned with accruals or pre- 54 - payments; neither does it include 'notional' expenses such as depreciation and bad debts provisions or take any note of whether transactions are capital or revenue. Although called an 'account', it is not part of the double-entry system, and nothing is transferred to it or from it. In order to draw up a receipts and payments account, it is necessary to do the following: • Combine similar items-such as the various payments for rent. This may involve combining entries in both the cash and the bank accounts. • Exclude transfers from bank to cash and from cash to bank. • Ignore any reference to the dates that items refer to, and concentrate solely on the actual sums received and the actual payments made. • Although a summary for the year, a receipts and payments account follows the same basic rules as a cash account, with receipts on the debit side and payments on the credit side. It starts with the opening balance and ends with the closing balance of both cash-in-hand and cash-at-bank. Example 1 The following are the bank and cash accounts of the Fortuna Social Club for the year ended 31st Dec. 2018. Bank account 1st Jan. 2018 14th Feb. Balance Cash 1440 15th Mar. Bequest from late President 4000 Cash 1600 10th Aug. b/f 1000 1st Feb. 14th Feb. 20th Jun. 30th Jun. - 55 - Rent (Apr-Jun 2018) Electricity (July-Dec 2017) Rent (July-Sep 2018) New disco equipment 300 240 300 3000 20th Nov. Cash 500 15th Aug. 14th Sep. Insurance (July 2018Jun 2019) Rent (Oct- Dec 2019) Electricity (Jan-June 2018) 7th Dec. Rent (Jan-Mar 2019) 31st Bank charges Dec. 31st Balance c/d Dec. 5th Oct. 8540 1st Jan., 2019 Balance b/d 2400 300 320 600 40 1040 8540 1040 Cash Account 1st Jan., 2018 31st Jan. 30th May 1st Aug. 3rd Oct. 15th Nov. Balance b/f 92 Subscriptions 1448 Refreshment receipts Subscriptions Refreshment receipts 1652 Subscriptions 590 200 240 14th Feb. 20th May 10th Aug. 3rd Sep. 20th Nov. 31st Dec. 1440 Bank Refreshment Costs 1600 Bank Refreshment Costs Bank Balance c/d 4222 1st Jan., 2019 Balance b/d 160 180 500 342 4222 342 Required: Show the receipts and payments account for the year. The Solution: Receipts and payments account for the year ended 31st Dec. 2018 Receipts Payments Balances on 1st Jan., 2018 Cash 92 Rent Electricity - 56 - 1500 560 Bank 1000 Subscriptions Bequest Refreshments 1092 3690 4000 440 Refreshments Disco equipment Insurance Bank charges 340 3000 2400 40 Balances on 31st Dec., 2018 Cash 342 Bank 1040 9222 1382 9222 The cash and bank accounts shown in Example 1 were elementary ones, and it was not difficult to combine and summarise the items concerned. Normally, even with quite a small club or society, the accounts for the year will be spread over a number of pages. So it makes the task considerably easier if a cash book with analysis columns is used, similar to those described in unit 18. Or a full set of ledger accounts can be maintained, but this is not usually necessary, except for large clubs and societies. 4. Income and Expenditure Accounts a. General principles In earlier courses, you learnt that profits and losses account take the income earned in a trading period (whether or not it has been received) and charges against it all items of expenditure incurred (no matter whether they have been paid or not). It is only by doing this that a fair view of the operating efficiency-measured by 'profit' or 'loss'-of the organisation can be obtained. As we saw, profit is something quite different from money received. Strictly, the income statement ( or the profit and losses account) only refer to commercial businesses. But the same principles can be applied to non-profit-making organisations-the only real difference is - 57 - a name change. Instead of being known as a profit and loss account, it is called an income and expenditure account; and in place of the terms profit and loss, the terms surplus and deficit are used. These terms are considered to be more suitable for non-profit-making organisations. Even the Not-for-Profit Organisations would like to know the net result of their activities of a particular period, generally one year. Though such organisations do not engage in trading activities and their objective is not earning profits, yet they would like to know whether income exceeds expenditure or vice versa. The amount of such difference is not termed Net Profit or Net Loss as it is so termed in business organisations. In the case of Not-for-profit organisations, the net result is termed as 'surplus’ or ‘deficit’ as the case may be. Despite that the preparation of the Income and Expenditure Account is a legal requirement, it helps organisations control their expenditure. As with a P&L account, adjustments are made when preparing an income and expenditure account for pre-payments and accruals. In addition, any 'capital' receipts or expenditures are excluded. 'Notional' charges, such as depreciation, are also allowed for. Also, income will appear on the credit side and expenditure on the debit side. The detailed figures for each item can be picked up either by keeping a complete system of ledger accounts in the normal way or by adjusting (where necessary) the data obtained from the cash book. An income and expenditure account may be drawn up either instead of the receipts and payment account or in addition to it. b. The Main Items of income and Expenditure: Revenues items: - 58 - • Subscription. It is a periodic contribution by members of the organisation • Entrance fees/Admission fees. It is received from members at the time of their admission to the organisation. • Donations. Donation is the amount received from a person, firm, company etc., by way of gift. But only general donation that too of smaller amount and recurring nature is treated an item of revenue income. • Sale of old newspapers, sports material, etc. Sale of old newspapers or condemned books, sports material etc. is treated as an item of revenue income. • Interest receipt. The surplus funds may be kept in a fixed deposit account in a bank or invested elsewhere. Interest received thereon is an item of revenue income. Expenditures Items: • Salaries, wages, rent, stationery, postage, telephone charges, electricity charges are some items of revenue expenses which are common to all Not for Profit Organisations (NPOs). • Depreciation. Depreciation is provided on the fixed assets such as furniture, building and books, etc. • Other Items. c. Preparation of Income And Expenditure Account In the previous section, the Income and Expenditure Account format and the items that are usually entered in the account have been explained. Now you will learn how to prepare the Income and Expenditure Account from the given items. This account is prepared from the Receipts and Payments account and additional information while preparing an Income - 59 - and Expenditure account. The following important points have to be kept in mind: Steps for Expenditure side The payment column of the Receipts and Payments Account contains both revenue items as well as capital items. Revenue items such as rent, paid salary, telephone charges etc., will be entered on the expenditure side of the Income and Expenditure Account. If necessary, adjustments will be made in these items for expenses outstanding at the end of the current year and/or were outstanding at the end of the previous year. Adjustments will also be made for prepaid expenses at the end of the previous year and those at the end of the current year. Steps for the Income side The receipt column contains items of revenue receipts as well as capital receipts. Revenue receipts are entered in the income column of the Income and Expenditure Account. Examples of such items are subscription, interest on investment, entrance fees etc. These items need to be adjusted for the amount received for the previous year or the following year. Similarly, adjustments should be made for outstanding income at the current year and at the end of the previous year. There may be other adjustments such as bad debts, depreciation, etc., which will also be entered in the expenditure column. Surplus or Deficit Finally, this account is balanced, i.e. difference of the totals of two amount columns is worked out. If the credit side is more than the debit side, the difference amount is written on its debit side as surplus, and if the debit side exceeds the credit side, the difference is a deficit is written on the credit side of the account. - 60 - Illustration 1 Prepare Income and Expenditure A/c of the following information of Promising Sportsmen’s club, Cairo for the year ending 31st Dec., 2020: Cash balance as on 1.1.2020 Subscriptions Interest received Sports material 7000 30000 2500 24000 Match fund 15000 Donations 2000 Sale of grass 300 Newspaper expenses 600 Investments purchased 10000 Salaries paid 16000 Rent paid 5400 Miscellaneous receipts 600 Telephone charges 1200 Cash balance as on 31.12.2020 200 Solution: Income & Expenditure Account for the year ended on 31st Dec. 2020 Expenditure Salaries Rent Newspaper Expense Telephone charges Surplus excess of income expenditure Amount 16000 5400 600 1200 12200 35400 - 61 - Income Subscriptions Interest Received Sale of grass Miscellaneous receipts Donations Amount 30000 2500 300 600 2000 35400 d. The problem of subscriptions Care has to be taken with club subscriptions. It must be remembered that these are payable to a club, unlike expenses, which are payable by a club. If subscriptions are owing at the end of the financial year, these will be subscriptions owing to the club. The amount is added to subscriptions for the year and will appear as an asset in the balance sheet alongside the prepaid expenses. If a ledger account is being kept for subscriptions, then the old period will be credited (thus increasing the amount to be transferred to income and expenditure), and the new period will be debited. If, on the other hand, subscriptions have been received during the year in advance for the following year, then the amount must be deducted from the actual subscriptions received for the current year and carried forward-appearing as a liability in the balance sheet. The ledger entries will be to debit the old period of the account with the amount paid in advance and credit the new period. Various adjustments relating to subscription are made in the following manner: - Subscription outstanding for the current year: the Journal entry takes the following form: Accrued ( outstanding) Subscriptions Subscriptions ×× ×× Subscription for the current year due but not received Adjustment in Income and Expenditure This amount will be added to subscriptions received in the Income and Expenditure Account and will be shown on the Asset side of the Balance Sheet. - 62 - - Subscription due in the previous year but received during the current year. The Journal entry takes the form: Cash ×× Accrued ( outstanding) Subscriptions ×× Adjustment of subscription due in last year but received in the current year Example 2 The following is information relates to the subscriptions at Assiut Club: Subscription received during the year 2019 15000 Subscription outstanding as of 31st Dec. 2019 1500 Subscription received in 2018 on account of 2019 800 Subscription received in the year 2019 for the outstanding 400 amount of the year 2018 Subscription received in the year 2019 for the year 2020 600 Required: Calculate the amount of subscription received to be shown in the Income and Expenditure Account for the year ending on 31st Dec., 2019. Solution: Subscription received during 2019 Add: current year outstanding Add: received in 2018 for 2019 Less: received for 2018 Less: advance for 2020 Subscription to be shown in Income & Expenditure Account for 2019 - 63 - 15000 1500 800 400 600 2300 17300 (1000) 16300 Subscriptions Account Balance (Accrued subscriptions 2018) Subscriptions received in advance 2020 Income & Expenditure 400 15000 Cash Accrued Subscriptions 2019 Subscriptions received in 16300 advance 17300 1500 600 800 17300 e. Rent Paid Rent paid is an item of expenditure. It may also require some rent adjustments. The adjustments required to be made to the amount of rent paid during the year may be as follows : (i) Rent outstanding for the current year (ii) Rent paid in the current year as advance for the next year (iii) Rent paid in the current year on account of the outstanding amount in the previous year (iv) Rent paid in the previous year on account of the current year. Journal entries will be made as follows: Rent A/c ×× Rent outstanding A/c (Rent due but not paid) Rent paid in advance A/c Dr. Bank A/c (Rent paid in advance for the year) ×× ×× ×× Rent outstanding A/c Dr. To Bank A/c (Amount paid for outstanding rent of the previous year) ×× Rent A/c ×× Dr. Rent paid in advance ×× ×× (Rent paid in advance last year being transferred to Rent A/c) - 64 - Calculation of Rent Amount to be shown for the current year in the Income and Expenditure Account Rent paid in the current year xx Add : xx Rent paid in advance in the previous year for the current year Rent due in the current year but not paid Outstanding rent paid for the previous year in the current year Advance rent paid for next year in the current year Add: Less: Less: Amount of Rent to be debited to Income and Expenditure A/c xx (x x) (x x) x xx Example: A club has paid rent of $20000 in the year 2020. Rent still to be paid amounts to $2000. An amount of $1500 was paid in 2019 on account of the year 2020. Calculate the amount to be taken to Income & expenditure A/c of 2020. Solution: Rent paid in 2020 $20000 Add rent outstanding for 2020 $2000 Add rent paid in advance in 2019 for the year 2020 1500 Rent for 2020 to be charged to Income and Expenditure A/c 23500 Example 3 Change the receipts and payments account in Example 1 into an income and expenditure account, taking into account: (i) Rent of $260 for the first quarter of 2018 had been paid in advance in December 2017. - 65 - (ii) Depreciation of $200 is to be allowed on the new disco equipment. (iii) Subscriptions of $700 due to the club for 2017 were received during 1989. Overdue subscriptions at the end of 2018 amounted to $680, but subscriptions for 2019 amounting to $80 had been paid in advance and were entered in the cash account during 2018. (iv) Amount owing for electricity for the period July-December 2018 was estimated at LE300. (v) Insurance for the period January-June 2018, $960, had been paid in advance during 2017. Notes: - Further information regarding accruals and pre-payments can be picked up from the data given in the cash and bank accounts of the original example. - The bequest from the late President and the new disco equipment's purchase should both be regarded as capital transactions. - Where an item involves both income and expenditure (e.g. refreshments in the example), the two elements can be brought together, and a net figure worked out and entered-showing, of course, the surplus or deficit on that particular item. Preliminary calculations Subscriptions Cash received during 2018 Add: owing at the end of 2018 Less: 2017 subscriptions received in 2019 2019 subscriptions received in 2018 Electricity - 66 - 3690 680 700 80 4370 (780) 3590 Cash paid during 2018 Add: owing at the end of 2018 Less: 2018payments for 2017 560 300 Insurance Cash paid during 2018 Add: pre-payment in 2017 for 2018 Less: pre-payment in 2018 for 2019 2400 960 Rent Cash paid in 2018 Add: pre-payment in 2017 for 2018 Less: pre-payment in 2018 for 2019 1500 260 860 (240) 620 3360 (1200) 2160 1760 (600) 1160 Income and expenditures account for the year ended 31st Dec. 2018 Expenditure Revenues Rent 1160 Subscriptions 3590 Electricity 620 Refreshments 440 Depreciation 200 less: Costs (340) 100 Insurance 2160 Deficit of the year 490 Bank charges 40 4180 4180 f. Depreciation on Assets: Depreciation is a non-cash item. It is to be charged on every fixed asset such as Land & Building, Furniture, Books etc., every year as per the predetermined method. The amount of depreciation is shown on the expenditure side of the Income & Expenditure Account. It is deducted from the respective value of the asset while showing it on the assets side of the Balance Sheet. Journal Entries will be as follows: - 67 - ×× Depreciation A/c Asset A/c Income and Expenditure A/c Depreciation A/c ×× ×× ×× 5. Other Final Accounts of Clubs and Societies a. Trading accounts Many clubs, societies and similar organisations, although nonprofitmaking as such, sometimes undertake trading activities to provide a service to members or make a profit to subsidise their normal work. Many clubs, for example, provide a bar for their members, and many charities sell a range of merchandise (goods) to raise funds. With these activities, it is possible to prepare a conventional trading account, the profit (or loss) taken either to the income and expenditure account, or directly to the balance sheet. b. Balance sheets Provided the appropriate information concerning assets and liabilities is available, it is possible to draw up balance sheets for clubs and societies. If the club concerned is maintaining (keeping) a full set of accounts, then the data required for the balance sheet will be available in the ledger in the usual way. If such accounts are not maintained, the data will have to be calculated from such information as may be available. Provided the source information is adequate and reliable, a perfectly satisfactory balance sheet can usually be constructed. The following points should be noted: (i) The term capital is considered unsuitable for a non-profitmaking organisation; the expression accumulated fund (or sometimes consolidated fund) is used instead. - 68 - (ii) It is common in examination questions to provide a list of the balances of assets and liabilities as they stood at the beginning of the period, plus the actual cash and bank accounts. The list of assets may well not include the following: - The cash and bank balances. Candidates are expected to obtain these from cash and bank accounts. - The opening balance of the accumulated fund. This has to be calculated by finding the difference between assets and liabilities at that date. - The amount to be charged in respect of depreciation. This can be calculated by comparing the opening and closing balances of the assets concerned after allowing for any assets bought or sold. (iii) The surplus or deficit on income and expenditure account will be added to or subtracted from the accumulated fund in the same way that profit (or loss) is taken to the capital account in a commercial firm. The four sections of the Balance Sheet are: • Fixed Assets – land, buildings, vehicles. • Current Assets – cash, closing stock, expenses prepaid etc. • Current Liabilities – bank overdraft, expenses due etc. • Financed By - Accumulated Fund, excess Income over Expenditure. Example 4: The assets and liabilities of Alahly Sports Club on 1st Jan. 2018 were: (Amounts in thousands) Premises $60000; subscriptions-in-arrears $96; equipment $6400; bank balance $3792; bar stocks $1840; subscriptions-in-advance $68. - 69 - Receipts during the year were: subscriptions $3388; bar takings $14400; disco evenings $640; sub-letting of room LE400. Payments during the year were: new equipment $2000; equipment maintenance LEl620; light and heating LE440; insurance $172; general expenses $108; bar purchases $13600; rates $1400. Further information available on 31st Dec. 2018: (i) Equipment at the year-end was valued at $8200, and bar stocks at $1642. (ii) Subscriptions-in-arrears amounted to $90 and in-advance $40. (iii) Insurance had been prepaid in the sum of $28. (iv) It was estimated that $100 was owing for heat and electricity. Draw up a receipts and payments account, the bar trading account and the income and expenditure account for the year to 31st Dec. 2018, and a balance sheet as of that date. The Solution Receipts and payments account for the year ended on 31st Dec. 2018 Receipts Bank Balance 1.1.2018 Subscription Sub-letting of rooms Bar takings Disco evening Payments 3792 3388 400 14400 640 Equipment Maintenance Light and heat Insurance General expenses Bar purchase Rates Bank balance 31.12.2018 22620 Bar trading account for the year ended on 31st Dec. 2018 - 70 - 2000 1520 440 172 108 13600 1400 3380 22620 Stocks 1.1.2018 Purchases 1840 13600 15440 Less stocks 31.12.2018 (1642) Cost of sales 13798 Bar profit 602 14400 Bar takings 14400 14400 Income and expenditures account for the year ended on 31.12.2018 Depreciation Insurance Less prepaid Maintenance Rates Light, heating Add: accrued General expenses Surplus of the year 200 172 (28) 440 100 144 1520 1400 Subscriptions Disco evenings Sub-lets of room Bar profit 3400 640 400 602 540 108 1130 5042 5042 The balance sheet as on 31st Dec. 2018 Fixed assets Premises Equipment Accumulated fund 1.1.2018 Add: surplus of the year 50000 8200 62070 1130 58200 Current assets Stock Subs, owing Insurance prepaid Bank Current liabilities: Subs. In advance Light, heat accrued 1642 90 28 3380 40 100 140 5140 63340 63340 Notes: a. Depreciation - 71 - Equipment 1.1.2018 Purchases 6400 2000 8400 (8200) 200 Less: Equipment 31/12/2018 The year depreciation (bal.fig.) b. Subscriptions Cash received Add: in advance on 1.1.2018 In arrears on 31.12.2018 3388 58 90 3536 Less: in arrears on 1.1.2018 In advance on 31.12.2018 96 40 (136) 3400 c. The accumulated fund on 1.1.2018 Fixed assets Premises Equipment Stock Subscription owing bank 50000 6400 1840 96 3792 62128 (58) 62070 Less: subscriptions in advance - 72 - CHAPTER THREE REVENUES RECOGNITION - 73 - Chapter Three Revenues Recognition Learning Objectives After studying this chapter, you should be able to: Discuss the fundamental concepts related to revenue recognition and measurement. Explain and apply the five-step revenue recognition process. Apply the five-step process to major revenue recognition issues. Describe presentation and disclosure regarding revenue. Background Revenue is one of, if not the most, important measures of financial performance that a company reports. Revenue provides insights into a company’s past and future performance and is a significant driver of other performance measures, such as EBITDA, net income, and earnings per share. Therefore, establishing robust guidelines for recognizing revenue is a standard-setting priority. Most revenue transactions pose few problems for revenue recognition. That is, most companies initiate and complete transactions at the same time. However, not all transactions are that simple. For example, consider a cell phone contract between a company such as Verizon and a customer. Verizon often provides a customer with a package that may include a handset, free minutes of talk time, data downloads, and text messaging service. In addition, some providers will bundle that with a fixed-line broadband service. At the same time, the customer may pay for these services in a variety of ways, possibly receiving a discount on the handset and then paying higher prices for connection fees and so forth. In some cases, depending on the package purchased, the company may provide free upgrades in subsequent - 74 - periods. How, then, should Verizon report the various pieces of this sale? The answer is not obvious. Both the FASB and the IASB indicated that the state of reporting for revenue was unsatisfactory. IFRS was criticized because it lacked guidance in a number of areas. For example, IFRS had one general standard on revenue recognition-IAS 18-plus some limited guidance related to certain minor topics. In contrast, GAAP had numerous standards related to revenue recognition (by some counts, well over 100), but many believed the standards were often inconsistent with one another. Thus, the accounting for revenue provided a most fitting contrast of the principles-based (IFRS) and rules-based (GAAP) approaches. Recently, the FASB and IASB issued a converged standard on revenue recognition entitled Revenue from Contracts with Customers. To address the inconsistencies and weaknesses of the previous approaches, a comprehensive revenue recognition standard now applies to a wide range of transactions and industries. The Boards believe this new standard will improve GAAP and IFRS by: a. Providing a more robust framework for addressing revenue recognition issues. b. Improving comparability of revenue recognition practices across entities, industries, jurisdictions, and capital markets. c. Simplifying the preparation of financial statements by reducing the number of requirements to which companies must refer. d. Requiring enhanced disclosures to help financial statement users better understand the amount, timing, and uncertainty of revenue that is recognized. New Revenue Recognition Standard The new standard, Revenue from Contracts with Customers, adopts an asset-liability approach as the basis for revenue recognition. The assetliability approach recognizes and measures revenue based on changes in - 75 - assets and liabilities. The Boards decided that focusing on (a) the recognition and measurement of assets and liabilities and (b) changes in those assets or liabilities over the life of the contract brings more discipline to the measurement of revenue, compared to the ”earned and realized” criteria in prior standards. Under the asset-liability approach, companies account for revenue based on the asset or liability arising from contracts with customers. Companies analyse contracts with customers because contracts initiate revenue transactions. Contracts indicate the terms of the transaction, provide the measurement of the consideration, and specify the promises that must be met by each party. Illustration 1 shows the key concepts related to this new standard on revenue recognition. The new standard first identifies the key objective of revenue recognition, followed by a five-step process that companies should use to ensure that revenue is measured and reported correctly. Illustration 1: Key Concepts of Revenue Recognition Key Objective Recognize revenue to depict the transfer of goods or services to customers in an amount that reflects the consideration that the company receives, or expects to receive, in exchange for these goods or services. Five-Step Process for Revenue Recognition • Identify the contract with customers. • Identify the separate performance obligations in the contract. • Determine the transaction price. • Allocate the transaction price to the separate performance obligations. • Recognize revenue when each performance obligation is satisfied. Revenue Recognition Principle Recognize revenue in the accounting period when the performance obligation is satisfied. - 76 - The culmination of the process is the revenue recognition principle, which states that revenue is recognized when the performance obligation is satisfied. We examine all steps in more detail in the following section. Overview of the Five-Step Process: Boeing Example Assume that Boeing Corporation signs a contract to sell airplanes to Delta Air Lines for $100 million. Illustration 2 shows the five steps that Boeing follows to recognize revenue. As indicated, Step 5 is when Boeing recognizes revenue related to the sale of the airplanes to Delta. At this point, Boeing delivers the airplanes to Delta and satisfies its performance obligation. In essence, a change in control from Boeing to Delta occurs. Delta now controls the assets because it has the ability to direct the use of and obtain substantially all the remaining benefits from the airplanes. Control also includes Delta’s ability to prevent other companies from directing the use of, or receiving the benefits from, the airplanes. Illustration 2: Five Steps of Revenue Recognition - 77 - Extended Example of the Five-Step Process: BEAN To provide another application of the basic principles of the five-step revenue recognition model, we use a coffee and wine business called BEAN. BEAN is located in the Midwest and serves gourmet coffee, espresso, lattes, teas, and smoothies. It also sells pastries, coffee beans, other food products, wine, and beer. Identifying the Contract with Customers-Step 1 Assume that Tyler Angler orders a large cup of black coffee costing $3 from BEAN. Tyler gives $3 to a BEAN barista, who pours the coffee into a large cup and gives it to Tyler. - 78 - Step 1 We first must determine whether a valid contract exists between BEAN and Tyler. Here are the components of a valid contract and how it affects BEAN and Tyler. 1. The contract has commercial substance: Tyler gives cash for the coffee. 2. The parties have approved the contract: Tyler agrees to purchase the coffee and BEAN agrees to sell it. 3. Identification of the rights of the parties is established: Tyler has the right to the coffee and BEAN has the right to receive $3. 4. Payment terms are identified: Tyler agrees to pay $3 for the coffee. 5. It is probable that the consideration will be collected: BEAN received $3 before it delivered the coffee. From this information, it appears that BEAN and Tyler have a valid contract with one another. Step 2 The next step is to identify BEAN’s performance obligation(s), if any. The answer is straightforward-BEAN has a performance obligation to provide a large cup of coffee to Tyler. BEAN has no other performance obligation for any other good or service. Step 3 BEAN must determine the transaction price related to the sale of the coffee. The price of the coffee is $3, and no discounts or other adjustments are available. Therefore, the transaction price is $3. Step 4 BEAN must allocate the transaction price to all performance obligations. Given that BEAN has only one performance obligation, no allocation is necessary. Step 5 Revenue is recognized when the performance obligation is satisfied. BEAN satisfies its performance obligation when Tyler obtains control of the coffee. The following conditions are indicators that control of the coffee has passed to Tyler: a. BEAN has the right to payment for the coffee. b. BEAN has transferred legal title to the coffee. c. BEAN has transferred physical possession of the coffee. d. Tyler has significant risks (e.g., he might spill the coffee) and rewards of ownership (he gets to drink the coffee). e. Tyler has accepted the asset. - 79 - Solution: BEAN should recognize $3 in revenue from this transaction when Tyler receives the coffee. Identifying Separate Performance Obligations-Step 2 The following day, Tyler orders another large cup of coffee for $3 and also purchases two bagels at a price of $5. The barista provides these products and Tyler pays $8. Question: How much revenue should BEAN recognize on the purchase of these two items? Step 1 A valid contract exists as it meets the five conditions necessary for a contract to be enforceable as discussed in the previous example. Step 2 BEAN must determine whether the sale of the coffee and the sale of the two bagels involve one or two performance obligations. In the previous transaction between BEAN and Tyler, this determination was straightforward because BEAN provided a single distinct product (a large cup of coffee) and therefore only one performance obligation existed. However, an arrangement to purchase coffee and bagels may have more than one performance obligation. Multiple performance obligations exist when the following two conditions are satisfied: 1. BEAN must provide a distinct product or service. In other words, BEAN must be able to sell the coffee and the bagels separately from one another. 2. BEAN’s products are distinct within the contract. In other words, if the performance obligation is not highly dependent on, or interrelated with, other promises in the contract, then each performance obligation should be accounted for separately. Conversely, if each of these products is interdependent and interrelated, these products are combined and reported as one performance obligation. The large cup of coffee and the two bagels appear to be distinct from one another and are not highly dependent or interrelated. That is, BEAN can sell the coffee and the two bagels separately, and Tyler benefits separately from the coffee and the bagels. - 80 - BEAN should therefore record two performance obligations-one for the sale of the coffee and one for the sale of the bagels. Step 3 The transaction price is $8 ($3 + $5). Step 4 BEAN has two performance obligations: to provide (1) a large cup of coffee and (2) the two bagels. Each of these obligations is distinct and not interrelated (and priced separately); no allocation of the transaction price is necessary. That is, the coffee sale is recorded at $3 and the sale of the bagels is priced at $5. Step 5 BEAN has satisfied both performance obligations when the coffee and bagels are given to Tyler (control of the product has passed to the customer). Solution: BEAN should recognize $8 ($3 + $5) of revenue when Tyler receives the coffee and bagels. Determining the Transaction Price-Step 3 BEAN decides to provide an additional incentive to its customers to shop at its store. BEAN roasts its own coffee beans and sells the beans wholesale to grocery stores, restaurants, and other commercial companies. In addition, it sells the coffee beans at its retail location. BEAN is interested in stimulating sales of its Smoke Jumper coffee beans on Tuesdays, a slow business day for the store. Normally, these beans sell for $10 for a 12-ounce bag, but BEAN decides to cut the price by $1 when customers buy them on Tuesdays (the discounted price is now $9 per bag). Tyler has come to the store on a Tuesday, decides to purchase a bag of Smoke Jumper beans, and pays BEAN $9. Question: How much revenue should BEAN recognize on this transaction? Step 1 As in our previous examples, with the sale of a large cup of coffee or the sale of a large cup of coffee and two bagels, a valid contract exists. The same is true for the sale of Smoke Jumper beans as well. - 81 - Step 2 The identification of the performance obligation is straightforward. BEAN has a performance obligation to provide a bag of Smoke Jumper coffee beans to Tyler. BEAN has no other performance obligation to provide a product or service. Step 3 The transaction price for a bag of Smoke Jumper beans sold to Tyler is $9, not $10. The transaction price is the amount that a company expects to receive from a customer in exchange for transferring goods and services. The transaction price in a contract is oft en easily determined because the customer agrees to pay a fixed amount to the company over a short period of time. In other contracts, companies must consider adjustments such as when they make payments or provide some other consideration to their customers (e.g., a coupon) as part of a revenue arrangement.3 Step 4 BEAN allocates the transaction price to the performance obligations. Given that there is only one performance obligation, no allocation is necessary. Step 5 BEAN has satisfied the performance obligation as control of the product has passed to Tyler. Solution: BEAN should recognize $9 of revenue when Tyler receives the Smoke Jumper coffee beans. Allocating the Transaction Price to Separate Performance Obligations-Step 4 For revenue arrangements with multiple performance obligations, BEAN might be required to allocate the transaction price to more than one performance obligation in the contract. If an allocation is needed, the transaction price is allocated to the various performance obligations based on their relative standalone selling prices. If this information is not available, companies should use their best estimate of what the good or service might sell for as a standalone unit. - 82 - BEAN wants to provide even more incentive for customers to buy its coffee beans, as well as purchase a cup of coffee. BEAN therefore offers customers a $2 discount on the purchase of a large cup of coffee when they buy a bag of its premium Motor Moka beans (which normally sell for $12) at the same time. Tyler decides this offer is too good to pass up and buys a bag of Motor Moka beans for $12 and a large cup of coffee for $1. As indicated earlier, a large cup of coffee normally retails for $3 at BEAN. Question: How much revenue should BEAN recognize on the purchase of these two items? Step 1 In our previous situations, valid contracts have existed. The same is also true for the sale of a bag of Motor Moka beans and the large cup of coffee. Step 2 The bag of Motor Moka beans and the large cup of coffee are distinct from one another and are not highly dependent on or highly interrelated with the other. BEAN can sell a bag of the Motor Moka beans and a large cup of coffee separately. Furthermore, Tyler benefits separately from both the large cup of coffee and the Motor Moka coffee beans. Step 3 BEAN’s transaction price is $13 ($12 for the bag of Motor Moka beans and $1 for the large cup of coffee). Step 4 BEAN allocates the transaction price to the two performance obligations based on their relative standalone selling prices. The standalone selling price of a bag of Motor Moka beans is $12 and the large cup of coffee is $3. The allocation of the transaction price of $13 is as follows. Product Standalone Selling Price $12 Percentage Allocated Amount $10.40 (413x.80) Motor Moka beans 80% ($12 ÷ $15) (one bag) Large cup of coffee 3 20% ($3 ÷ $15) 2.60 ($13 x .20) Total $15 100% $13.00 As indicated, the total transaction price ($13) is allocated $10.40 to the bag of Motor Moka beans and $2.60 to the large cup of coffee. - 83 - Step 5 BEAN has satisfied both performance obligations as control of the bag of Motor Moka beans and the large cup of coff ee has passed to Tyler. Solution: BEAN should recognize revenue of $13, comprised of revenue from the sale of the Motor Moka beans at $10.40 and the sale of the large cup of coffee at $2.60. Recognizing Revenue When (or as) Each Performance Obligation Is Satisfied-Step 5 As indicted in the examples presented, BEAN satisfied its performance obligation(s) when Tyler obtained control of the product(s). Change in control is the deciding factor in determining when a performance obligation is satisfied. A customer controls the product or service when the customer has the ability to direct the use of and obtain substantially all the remaining benefits from the product. Control also includes Tyler’s ability to prevent other companies from directing the use of, or receiving benefits from, the coffee or coffee beans. As discussed earlier, the indicators that Tyler has obtained control are as follows: a. BEAN has the right to payment for the coffee. b. BEAN has transferred legal title to the coffee. c. BEAN has transferred physical possession of the coffee. d. Tyler has significant risks and rewards of ownership. e. Tyler has accepted the asset. The Five-Step Process Revisited The Boeing and BEAN examples provide a basic understanding of the five-step process used to recognize revenue. We now discuss more technical issues related to the implementation of these five steps. Identifying the Contract with Customers-Step 1 A contract is an agreement between two or more parties that creates enforceable rights or obligations. Contracts can be written, oral, or - 84 - implied from customary business practice (such as the BEAN contract with Tyler). Revenue is recognized only when a valid contract exists. On entering into a contract with a customer, a company obtains rights to receive consideration from the customer and assumes obligations to transfer goods or services to the customer (performance obligations). The combination of those rights and performance obligations gives rise to an (net) asset or (net) liability. In some cases, there are multiple contracts related to an arrangement; accounting for each contract may or may not occur, depending upon the circumstances. These situations often develop when not only a product is provided but some type of service is performed as well. To be valid, a contract must meet the five conditions illustrated in the BEAN example. If the contract is wholly unperformed and each party can unilaterally terminate the contract without compensation, then revenue should not be recognized until one or both of the parties have performed. A basic contract in which these issues are discussed is presented in Illustration 3. - 85 - Illustration 3 Basic Revenue Transaction Contracts and Recognition Facts: On March 1, 2020, Margo Company enters into a contract to transfer a product to Soon Yoon on July 31, 2020. The contract is structured such that Soon Yoon is required to pay the full contract price of $5,000 on August 31, 2020. The cost of the goods transferred is $3,000. Either party can unilaterally terminate the contract without compensation. Margo delivers the product to Soon Yoon on July 31, 2020. Question: What journal entries should Margo Company make in regards to this contract in 2020? Solution: No entry is required on March 1, 2020, because neither party has performed on the contract. On July 31, 2020, Margo delivers the product and therefore should recognize revenue on that date as it satisfies its performance obligation by delivering the product to Soon Yoon. The journal entry to record the sale and related cost of goods sold is as follows. July 31, 2020 Accounts Receivable 5000 Sales Revenue 5000 Cost of Goods Sold 3000 Inventory 3000 After receiving the cash payment on August 31, 2020, Margo makes the following entry. August 31, 2020 Cash 5000 Accounts Receivable 5000 A key feature of the revenue arrangement is that the contract between the two parties is not recorded (does not result in a journal entry) until one or both of the parties perform under the contract. Until performance occurs, no net asset or net liability exists.5 - 86 - Identifying Separate Performance Obligations-Step 2 A performance obligation is a promise to provide a product or service to a customer. This promise may be explicit, implicit, or possibly based on customary business practice. To determine whether a performance obligation exists, the company must provide a distinct product or service to the customer. A product or service is distinct when a customer is able to benefit from a good or service on its own or together with other readily available resources. This situation typically occurs when the company can sell a good or service on a standalone basis (can be sold separately). For example, BEAN provided a good (a large cup of coffee) on a standalone basis to Tyler. Tyler benefited from this cup of coffee by consuming it. To determine whether a company has to account for multiple performance obligations, the company’s promise to sell the good or service to the customer must be separately identifiable from other promises within the contract (that is, the good or service must be distinct within the contract). In other words, the objective is to determine whether the nature of a company’s promise is to transfer individual goods and services to the customer or to transfer a combined item (or items) for which individual goods or services are inputs. For example, when BEAN sold Tyler a large cup of coffee and two bagels, two performance obligations occurred. In that case, the large cup of coffee had a standalone selling price and the two bagels had a standalone selling price-even though the two promises may be part of one contract. Conversely, assume that BEAN sold a large latte (comprised of coffee and milk) to Tyler. In this case, BEAN sold two distinct products (coffee and milk), but these two goods are not distinct within the contract. That is, the coffee and milk in the latte are highly interdependent or interrelated within the contract. As a result, the products are combined and reported as one performance obligation. - 87 - To illustrate another situation, assume that General Motors sells an automobile to Marquart Auto Dealers at a price that includes six months of telematics services such as navigation and remote diagnostics. These telematics services are regularly sold on a standalone basis by General Motors for a monthly fee. After the six-month period, the consumer can renew these services on a fee basis with General Motors. The question is whether General Motors sold one or two products. If we look at General Motors’ objective, it appears that it is to sell two goods, the automobile and the telematic services. Both are distinct (they can be sold separately) and are not interdependent. As another example, SoftTech Inc. licenses customerrelationship software to Lopez Company. In addition to providing the software itself, SoftTech promises to perform consulting services by extensively customizing the software to Lopez’s information technology environment, for total consideration of $600,000. In this case, the objective of SoftTech appears to be to transfer a combined product and service for which individual goods and services are inputs. In other words, SoftTech is providing a significant service by integrating the goods and services (the license and the consulting service) into one combined item for which Lopez has contracted. In addition, the software is significantly customized by SoftTech in accordance with specifications negotiated by Lopez. As a result, the license and the consulting services are distinct but interdependent, and therefore should be accounted for as one performance obligation. Determining the Transaction Price-Step 3 The transaction price is the amount of consideration that a company expects to receive from a customer in exchange for transferring goods and services. The transaction price in a contract is often easily determined because the customer agrees to pay a fixed amount to the company over a short period of time. In other contracts, companies must consider the following factors. - 88 - • Variable consideration. • Time value of money. • Noncash consideration. • Consideration paid or payable to the customer. Variable Consideration In some cases, the price of a good or service is dependent on future events. These future events might include price increases, volume discounts, rebates, credits, performance bonuses, or royalties. In these cases, the company estimates the amount of variable consideration it will receive from the contract to determine the amount of revenue to recognize. Companies use either the expected value, which is a probability-weighted amount, or the most likely amount in a range of possible amounts to estimate variable consideration. Companies select among these two methods based on which approach better predicts the amount of consideration to which a company is entitled. Illustration 4 highlights the issues to be considered in selecting the appropriate method. Most Likely Amount: The single most likely amount in a range of possible consideration outcomes. • May be appropriate if a company has a • May be appropriate if the large number of contracts with similar contract has only two possible characteristics. outcomes. • Can be based on a limited number of discrete outcomes and probabilities. Expected Value: Probability-weighted amount in a range of possible consideration amounts. Illustration 5 provides an application of the two estimation methods. - 89 - Illustration 5 Transaction Price Variable Consideration Estimating Variable Consideration Facts: Peabody Construction Company enters into a contract with a customer to build a warehouse for $100,000, with a performance bonus of $50,000 that will be paid based on the timing of completion. The amount of the performance bonus decreases by 10% per week for every week beyond the agreed-upon completion date. The contract requirements are similar to contracts that Peabody has performed previously, and management believes that such experience is predictive for this contract. Management estimates that there is a 60% probability that the contract will be completed by the agreed-upon completion date, a 30% probability that it will be completed 1 week late, and only a 10% probability that it will be completed 2 weeks late. Solution: The transaction price should include management’s estimate of the amount of consideration to which Peabody will be entitled. Management has concluded that the probability-weighted method is the most predictive approach for estimating the variable consideration in this situation: On time: 60% chance of $150,000 [$100,000 + ($50,000 × 1.0)] = $ 90,000 1 week late: 30% chance of $145,000 [$100,000 + ($50,000 × .90)] = 43,500 2 weeks late: 10% chance of $140,000 [$100,000 + ($50,000 × .80)] = Thus, the total transaction price is $147,500 based on the probability-weighted estimate. Management should update its estimate at each reporting date. Using a most likely outcome approach may be more predictive if a performance bonus is binary (Peabody either will or will not earn the performance bonus), such that Peabody earns either the $50,000 bonus for completion on the agreed-upon date or nothing for completion aft er the agreed-upon date. In this scenario, if management believes that Peabody will meet the deadline and estimates the consideration using the most likely outcome, the total transaction price would be $150,000 (the outcome with 60% probability). - 90 - A word of caution-a company only allocates variable consideration if it is reasonably assured that it will be entitled to that amount. Companies therefore may only recognize variable consideration if (1) they have experience with similar contracts and are able to estimate the cumulative amount of revenue, and (2) based on experience, it is highly probable that there will not be a significant reversal of revenue previously recognized.7 If these criteria are not met, revenue recognition is constrained. Illustration 6 provides an example of how the revenue constraint works. Illustration 6 Transaction Price-Revenue Constraint Revenue Constraint Facts: On January 1, Shera Company enters into a contract with Hornung Inc. to perform asset-management services for 1 year. Shera receives a quarterly management fee based on a percentage of Hornung’s assets under management at the end of each quarter. In addition, Shera receives a performance-based incentive fee of 20% of the fund’s return in excess of the return of an observable index at the end of the year. Shera accounts for the contract as a single performance obligation to perform investment-management services for 1 year because the services are interdependent and interrelated. To recognize revenue for satisfying the performance obligation over time, Shera selects an output method of measuring progress toward complete satisfaction of the performance obligation. Shera has had a number of these types of contracts with customers in the past. Question: At what point should Shera recognize the management fee and the performance-based incentive fee related to Hornung? Solution: Shera should record the management fee each quarter as it performs the management of the fund. However, Shera should not record the incentive fee until the end of the year. Although Shera has experience with similar contracts, that experience is not predictive of the outcome of the current contract because the amount of consideration is highly susceptible to volatility in the market. - 91 - In addition, the incentive fee has a large number and high variability of possible consideration amounts. Thus, revenue related to the incentive fee is constrained (not recognized) until the incentive fee is known at the end of the year. Time Value of Money Timing of payment to the company sometimes does not match the transfer of the goods or services to the customer. In most situations, companies receive consideration after the product is provided or the service performed. In essence, the company provides fi nuancing for the customer. Companies account for the time value of money if the contract involves a significant financing component. When a sales transaction involves a significant financing component (i.e., interest is accrued on consideration to be paid over time), the fair value should be determined by discounting the payment using an imputed interest rate. The imputed interest rate is the more clearly determinable of either (1) the prevailing rate for a similar instrument of an issuer with a similar credit rating, or (2) a rate of interest that discounts the nominal amount of the instrument to the current sales price of the goods or services. The company will report the effects of the financing as interest revenue. Illustration 7 provides an example of a financing transaction. Illustration 7 Transaction Price- Extended Payment Terms Facts: On July 1, 2020, SEK Company sold goods to Grant Company for $900,000 in exchange for a 4-year zero-interest-bearing note with a face amount of $1,416,163. The goods have an inventory cost on SEK’s books of $590,000. SEK uses the perpetual inventory method. Solution: (a) SEK should record revenue of $900,000 on July 1, 2020, which is the fair value of the inventory in this case. - 92 - (b) SEK is also financing this purchase and records interest revenue on the note over the 4-year period. In this case, the interest rate is imputed and is determined to be 12%. SEK records interest revenue of $54,000 (.12 × 6/12 × $900,000) at December 31, 2020. The entry to record SEK’s sale to Grant Company is as follows. July 1, 2020 Notes Receivable 1416163 Discount on Notes Receivable 516163 Sales Revenue 900000 Cost of Goods Sold 590000 Inventory 590000 SEK makes the following entry to record (accrue) interest revenue at the end of the year. December 31, 2020 Discount on Notes Receivable 54000 Interest Revenue (.12 × 6/12 × $900,000) 54000 As a practical expedient, companies are not required to reflect the time value of money to determine the transaction price if the time-period for payment is less than a year. Noncash Consideration Companies sometimes receive consideration in the form of goods, services, or other noncash consideration. When these situations occur, companies generally recognize revenue on the basis of the fair value of what is received. For example, assume that Raylin Company receives common stock of Monroe Company in payment for consulting services. In that case, Raylin Company recognizes revenue in the amount of the fair value of the common stock received. If Raylin cannot determine this amount, then it should estimate the selling price of the services performed and recognize this amount as revenue. - 93 - In addition, companies sometimes receive contributions (e.g., donations and gifts). A contribution is often some type of asset (e.g., securities, land, buildings, or use of facilities) but it could be the forgiveness of debt. In these cases, companies recognize revenue for the fair value of the consideration received. Similarly, customers sometimes contribute goods or services, such as equipment or labor, as consideration for goods provided or services performed. This consideration should be recognized as revenue based on the fair value of the consideration received. Consideration Paid or Payable to Customers Companies often make payments to their customers as part of a revenue arrangement. Consideration paid or payable may include discounts, volume rebates, coupons, free products, or services. In general, these elements reduce the consideration received and the revenue to be recognized. Illustration 8 provides an example of this type of transaction. Illustration 8: Transaction Price-Volume Discount Volume Discount Facts: Sansung Company offers its customers a 3% volume discount if they purchase at least $2 million of its product during the calendar year. On March 31, 2020, Sansung has made sales of $700,000 to Artic Co. In the previous 2 years, Sansung sold over $3,000,000 to Artic in the period April 1 to December 31. Assume that Sansung prepares financial statements quarterly. Question: How much revenue should Sansung recognize for the first 3 months of 2020? Solution: In this case, Sansung should reduce its revenue by $21,000 ($700,000 × .03) because it is probable that it will provide this rebate. Revenue is therefore $679,000 ($700,000 - $21,000). To not recognize this volume discount overstates Sansung’s revenue for the first 3 months - 94 - of 2020. In other words, the appropriate revenue to be recognized is $679,000, not $700,000. Given these facts, Sansung makes the following entry on March 31, 2020, to recognize revenue. Accounts Receivable 679000 Sales Revenue 679000 Assuming that Sansung’s customer meets the discount threshold, Sansung makes the following entry to record collection of accounts receivable. Cash 679000 Accounts Receivable 679000 If Sansung’s customer fails to meet the discount threshold, Sansung makes the following entry to record collection of accounts receivable. Cash 700000 Accounts Receivable 679000 Sales Discounts Forfeited 21000 Sales Discounts Forfeited is reported in the “Other revenues and gains” section of the income statement. In many cases, companies provide cash discounts to customers for a short period of time (often referred to as prompt settlement discounts). For example, assume that terms are payment due in 60 days, but if payment is made within five days, a two percent discount is given (referred to as 2/5, net 60). These prompt settlement discounts should reduce revenues, if material. In most cases, companies record the revenue at full price (gross) and record a sales discount if payment is made within the discount period. Allocating the Transaction Price to Separate Performance Obligations-Step 4 Companies often have to allocate the transaction price to more than one performance obligation in a contract. If an allocation is needed, the transaction price allocated to the various performance obligations is - 95 - based on their relative fair values. The best measure of fair value is what the company could sell the good or service for on a standalone basis, referred to as the standalone selling price. If this information is not available, companies should use their best estimate of what the good or service might sell for as a standalone unit. Illustration 9 summarizes the approaches that companies follow (in preferred order of use). Illustration 9 Transaction Price-allocation Allocation Approach Adjusted market assessment approach Expected cost plus a margin approach Residual approach Implementation Evaluate the market in which the company sells goods or services and estimate the price that customers in that market are willing to pay for those goods or services. That approach also might include referring to prices from the company’s competitors for similar goods or services and adjusting those prices as necessary to reflect the company’s costs and margins. Forecast expected costs of satisfying a performance obligation and then add an appropriate margin for that good or service. If the standalone selling price of a good or service is highly variable or uncertain, then a company may estimate the standalone selling price by reference to the total transaction price less the sum of the observable standalone selling prices of other goods or services promised in the contract. To illustrate, Travis Company enters into a contract with a customer to sell Products A, B, and C in exchange for $100,000. Travis Company regularly sells Product A separately, and therefore the standalone selling price is directly observable at $50,000. The standalone selling price of Product B is estimated using the adjusted market assessment approach and is determined to be $30,000. Travis Company decides to use the residual approach to value Product C as it has confidence that Products - 96 - A and B are valued correctly. The selling price for the products is allocated as shown in Illustration 10. Illustration 10 Residual Value Allocation: Product A B Price $ 50000 30000 20000 C Rationale Directly observable using standalone selling price. Directly observable using adjusted market assessment approach. [$100,000 - ($50,000 + $30,000)]; using the residual approach given reliability of the two above measurements. Total trans- $100000 action price Illustrations 11 and 12 are additional examples of the measurement issues involved in allocating the transaction price Illustrations 11: Allocation-Multiple Performance Obligations Multiple Performance Obligations-Example 1 Facts: Lonnie Company enters into a contract to build, run, and maintain a highly complex piece of electronic equipment for a period of 5 years, commencing upon delivery of the equipment. There is a fixed fee for each of the build, run, and maintenance deliverables, and any progress payments made are non-refundable. It is determined that the transaction price must be allocated to the three performance obligations: building, running, and maintaining the equipment. There is verifiable evidence of the selling price for the building and maintenance but not for running the equipment. Question: What procedure should Lonnie Company use to allocate the transaction price to the three performance obligations? Solution: The performance obligations relate to building the equipment, running the equipment, and maintaining the equipment. As indicated, Lonnie can determine verifiable standalone selling prices for the equipment and the maintenance agreements. The company then can make a best estimate of the - 97 - selling price for running the equipment, using the adjusted market assessment approach or expected cost plus a margin approach. Lonnie next applies the proportional standalone selling price method at the inception of the transaction to determine the proper allocation to each performance obligation. Once the allocation is performed, Lonnie recognizes revenue independently for each performance obligation using regular revenue recognition criteria. If, on the other hand, Lonnie is unable to estimate the standalone selling price for running the equipment because such an estimate is highly variable or uncertain, Lonnie may use a residual approach. In this case, Lonnie uses the standalone selling prices of the equipment and maintenance agreements and subtracts these prices from the total transaction price to arrive at a residual value for running the equipment. Illustration 12 Multiple Installation, and Service Performance Obligations-Product, Facts: Handler Company is an established manufacturer of equipment used in the construction industry. Handler’s products range from small to large individual pieces of automated machinery to complex systems containing numerous components. Unit selling prices range from $600,000 to $4,000,000 and are quoted inclusive of installation and training. The installation process does not involve changes to the features of the equipment and does not require proprietary information about the equipment in order for the installed equipment to perform to specifications. Handler has the following arrangement with Chai Company. • Chai purchases equipment from Handler for a price of $2,000,000 and chooses Handler to do the installation. Handler charges the same price for the equipment irrespective of whether it does the installation or not. (Some companies do the installation themselves because they either prefer their own employees to do the work or because of relationships with other customers.) The installation service included in the arrangement is estimated to have a standalone selling price of $20,000. - 98 - • The standalone selling price of the training sessions is estimated at $50,000. Other companies can also perform these training services. • Chai is obligated to pay Handler the $2,000,000 upon the delivery and installation of the equipment. • Handler delivers the equipment on September 1, 2020, and completes the installation of the equipment on November 1, 2020 (transfer of control is complete after installation). Training related to the equipment starts once the installation is completed and lasts for 1 year. The equipment has a useful life of 10 years. Questions: (a) What are the performance obligations for purposes of accounting for the sale of the equipment? (b) If there is more than one performance obligation, how should the payment of $2,000,000 be allocated to various components? Solution: (a) Handler’s primary objective is to sell equipment. The other services (installation and training) can be performed by other parties if necessary. As a result, the equipment, installation, and training are three separate products or services. Each of these items has a standalone selling price and is not interdependent. (b) The total revenue of $2,000,000 should be allocated to the three components based on their relative standalone selling prices. In this case, the standalone selling price of the equipment is $2,000,000, the installation fee is $20,000, and the training is $50,000. The total standalone selling price therefore is $2,070,000 ($2,000,000 + $20,000 + $50,000). The allocation is as follows: Equipment $1,932,367 [($2,000,000 ÷ $2,070,000) × $2,000,000] Installation 19,324 [($20,000 ÷ $2,070,000) × $2,000,000] Training 48,309 [($50,000 ÷ $2,070,000) × $2,000,000] $2,000,000 - 99 - Handler makes the following entry on November 1, 2020, to record both sales revenue and service revenue on the installation, as well as unearned service revenue. November 1, 2020 Cash 2000000 Service Revenue (installation) 19324 Unearned Service Revenue 48309 Sales Revenue 1932367 Assuming the cost of the equipment is $1,500,000, the entry to record cost of goods sold is as follows: November 1, 2020 Cost of Goods Sold 1500000 Inventory 1500000 As indicated by these entries, Handler recognizes revenue from the sale of the equipment once the installation is completed on November 1, 2020. In addition, it recognizes revenue for the installation fee because these services have been performed. Handler recognizes the training revenues on a straight-line basis starting on November 1, 2020, or $4,026 ($48,309 ÷ 12) per month for 1 year (unless a more appropriate method such as the percentage-of completion method-discussed in the next section-is warranted). The journal entry to recognize the training revenue for 2 months in 2020 is as follows. December 31, 2020 Unearned Service Revenue Service Revenue (training) ($4026 × 2) 8052 8052 Therefore, Handler recognizes revenue at December 31, 2020, in the amount of $1,959,743 ($1,932,367 + $19,324 + $8,052). Handler makes the following journal entry to recognize the remaining training revenue in 2021, assuming adjusting entries are made at year-end. - 100 - December 31, 2021 Unearned Service Revenue 40257 Service Revenue (training) ($48309 - $8052) 40257 Recognizing Revenue When (or as) Each Performance Obligation Is Satisfied-Step 5 A company satisfies its performance obligation when the customer obtains control of the good or service. As indicated in the Handler example (in Illustration 18.12) and the BEAN example, the concept of change in control is the deciding factor in determining when a performance obligation is satisfied. The customer controls the product or service when it has the ability to direct the use of and obtain substantially all the remaining benefi ts from the asset or service. Control also includes the customer’s ability to prevent other companies from directing the use of, or receiving the benefits, from the asset or service. Illustration 13 summarizes the indicators that the customer has obtained control. Illustration 13 Change in Control Indicators 1. The company has a right to payment for the asset. 2. The company has transferred legal title to the asset. 3. The company has transferred physical possession of the asset. 4. The customer has significant risks and rewards of ownership. 5. The customer has accepted the asset. This is a list of indicators, not requirements or criteria. Not all of the indicators need to be met for management to conclude that control has transferred and revenue can be recognized. Management must use judgment to determine whether the factors collectively indicate that the customer has obtained control. This assessment should be focused primarily on the customer’s perspective. Companies satisfy performance obligations either at a point in time or over a period of time. Companies recognize revenue over a period of time if one of the following three criteria is met. - 101 - 1. The customer receives and consumes the benefits as the seller performs. 2. The customer controls the asset as it is created or enhanced (e.g., a builder constructs a building on a customer’s property). 3. The company does not have an alternative use for the asset created or enhanced (e.g., an aircraft manufacturer builds specialty jets to a customer’s specifications) and either (a) the customer receives benefits as the company performs and therefore the task would not need to be re-performed, or (b) the company has a right to payment and this right is enforceable. Illustration 14 provides an example of the point in time when revenue should be recognized. Illustration 14 Satisfying a Performance Obligation Facts: Gomez Software Company enters into a contract with Hurly Company to develop and install customer relationship management (CRM) software. Progress payments are made upon completion of each stage of the contract. If the contract is terminated, then the partly completed CRM soft ware passes to Hurly Company. Gomez Software is prohibited from redirecting the software to another customer. Solution: Gomez Software does not create an asset with an alternative use because it is prohibited from redirecting the software to another customer. In addition, Gomez Software is entitled to payments for performance to date and expects to complete the project. Therefore, Gomez Software concludes that the contract meets the criteria for recognizing revenue over time. A company recognizes revenue from a performance obligation over time by measuring the progress toward completion. The method selected for measuring progress should depict the transfer of control from the company to the customer. For many service arrangements, revenue is recognized on a straight-line basis because the performance obligation is being satisfied ratably over the contract period. In other settings (e.g., long-term construction contracts), companies use various - 102 - methods to determine the extent of progress toward completion. The most common are the cost-to-cost and units of-delivery methods. The objective of all these methods is to measure the extent of progress in terms of costs, units, or value added. Companies identify the various measures (costs incurred, labor hours worked, tons produced, floors completed, etc.) and classify them as input or output measures. Input measures (e.g., costs incurred and labor hours worked) are efforts devoted to a contract. Output measures (with units of delivery measured as tons produced, floors of a building completed, miles of a highway completed, etc.) track results. Neither is universally applicable to all long-term projects. Their use requires the exercise of judgment and careful tailoring to the circumstances. The most popular input measure used to determine the progress toward completion is the cost-to-cost basis. Under this basis, a company measures the percentage of completion by comparing costs incurred to date with the most recent estimate of the total costs required to complete the contract. The percentage-of-completion method, which examines the accounting for long-term contracts, is discussed more fully in a following section in this chapter. Accounting for Revenue Recognition Issues This section addresses revenue recognition issues found in practice. Most of these issues relate to determining the transaction price (Step 3) and evaluating when control of the product or service passes to the customer (Step 5). The revenue recognition principle and the concept of control are illustrated for the following situations: • Sales returns and allowances. • Consignments. • Repurchase agreements. • Warranties. • Bill and hold. - 103 - • Nonrefundable upfront fees. • Principal-agent relationships. Sales Returns and Allowances Sales returns and allowances are very common for many companies that sell goods to customers. For example, assume that Fafco Solar sells solar panels to customers on account. Fafco grants customers the right of return for these panels for various reasons (e.g., dissatisfaction with the product). Customers may receive any combination of the following. 1. A full or partial refund of any consideration paid. 2. A credit that can be applied against amounts owed, or that will be owed, to the seller. 3. Another product in exchange. To account for these sales returns and allowances, Fafco should recognize the following: a. Revenue for the transferred solar panels in the amount of consideration to which Fafco is reasonably assured to be entitled (considering the products to be returned or allowance granted). b. An asset (and corresponding adjustment to cost of goods sold) for the goods returned from customers. Credit Sales with Returns and Allowances To illustrate the accounting for a return situation in more detail, assume that on January 12, 2020, Venden Company sells 100 cameras for $100 each on account to Amaya Inc. Venden allows Amaya to return any unused cameras within 45 days of purchase. The cost of each product is $60. Venden estimates that: 1. Three products will be returned. 2. The cost of recovering the products will be immaterial. 3. The returned products are expected to be resold at a profit. - 104 - On January 24, Amaya returns two of the cameras because they were the wrong color. On January 31, Venden prepares financial statements and determines that it is likely that only one more camera will be returned. Venden makes the following entries related to these transactions. To record the sale of the cameras and related cost of goods sold on January 12, 2020 Accounts Receivable 10000 Sales Revenue (100 × $100) 10000 Cost of Goods Sold 6000 Inventory (100 × $60) 6000 To record the return of the two cameras on January 24, 2020 Sales Returns and Allowances 200 Accounts Receivable (2 × $100) 200 Returned Inventory 120 Cost of Goods Sold (2 × $60) 120 The Sales Returns and Allowances account is a contra-account to Sales Revenue. The Returned Inventory account is used to separate returned inventory from regular inventory. On January 31, 2020, Venden prepares financial statements. As indicated earlier, Venden originally estimated that the most likely outcome was that three cameras would be returned. Venden believes the original estimate is correct and makes the following adjusting entries to account for expected returns at January 31, 2020. To record expected sales returns on January 31, 2020 Sales Returns and Allowances 100 Allowance for Sales Returns and 100 Allowances (1 × $100) To record the expected return of the one camera and related reduction in Cost of Goods Sold Estimated Inventory Returns - 105 - 60 Cost of Goods Sold (1 × $60) 60 The Allowance for Sales Returns and Allowances account is a contra account to Accounts Receivable. The Estimated Inventory Returns account will generally be added to the Returned Inventory account at the end of the reporting period. For the month of January, Venden’s income statement reports the information presented as follows: Sales revenue (100 × $100) $10000 Less: Sales returns and allowances ($200 + $100) 300 Net sales 9700 Cost of goods sold (97 × $60) 5820 Gross profit $ 3880 As a result, at the end of the reporting period, the net sales refl ects the amount that Venden expects to be entitled to collect. Venden reports the following information in the balance sheet as of January 31, 2020, as shown bellow: Accounts receivable ($10,000 - $200) Less: Allowance for sales returns and allowances Accounts receivable (net) Returned inventory (including estimated) (3 × $60) $9800 100 9700 $ 180 Cash Sales with Returns and Allowances Assume now that Venden sold the cameras to Amaya for cash instead of on account. In this situation, Venden makes the following entries related to these transactions. To record the sale of the cameras and related cost of goods sold on January 12, 2020 Cash 10000 Sales Revenue (100 × $100) 10000 Cost of Goods Sold 6000 Inventory (100 × $60) 6000 - 106 - Assuming that Venden did not pay cash at the time of the return of the two cameras to Amaya on January 24, 2020, the entries to record the return of the two cameras and related cost of goods sold are as follows. To record the return of two cameras on January 24, 2020 Sales Returns and Allowances 200 Accounts Payable (2 × $100) 200 Returned Inventory 120 Cost of Goods Sold (2 × $60) 120 Venden records an accounts payable to Amaya to recognize that it owes Amaya for the return of two cameras. As indicated earlier, the Sales Returns and Allowances account is a contra-revenue account. The Returned Inventory account is used to separate returned inventory from regular inventory. On January 31, 2020, Venden prepares financial statements. As indicated earlier, Venden estimates that the most likely outcome is that one more camera will be returned. Venden therefore makes the following adjusting entries. To record expected sales returns on January 31, 2020 Sales Returns and Allowances Accounts Payable (1 × $100) 100 100 To record the expected return of the one camera and related Cost of Goods Sold Estimated Inventory Returns 60 Cost of Goods Sold (1× $60) 60 At January 31, 2020, Venden records an accounts payable to recognize its estimated additional liability to Amaya for expected future returns. The Estimated Inventory Returns account will generally be added to the - 107 - Returned Inventory account at the end of the reporting period to identify returned and estimated inventory returns. The following table presents the information related to these sales that will be reported on Venden’s income statement for the month of January. Sales revenue (100 × $100) $10000 Less: Sales returns and allowances (3 × $100) 300 Net sales 9700 Cost of goods sold (97 × $60) 5820 Gross profit $ 3880 On Venden’s balance sheet as of January 31, 2020, the information shown in the table is reported as follows: Cash (assuming no cash payments to date to Amaya) $10000 Returned inventory (including estimated) (3 × $60) 180 Accounts payable ($200 + $100) 300 Companies record the returned asset in a separate account from inventory to provide transparency. The carrying value of the returned asset is subject to impairment testing, separate from the inventory. If a company is unable to estimate the level of returns with any reliability, it should not report any revenue until the returns become predictive. Repurchase Agreements In some cases, companies enter into repurchase agreements, which allow them to transfer an asset to a customer but have an unconditional (forward) obligation or unconditional right (call option) to repurchase the asset at a later date. In these situations, the question is whether the company sold the asset. Generally, companies report these transactions as a financing (borrowing). That is, if the company has a forward obligation or call option to repurchase the asset for an amount greater than or equal to its selling price, then the transaction is a financing transaction by the company. - 108 - The table bellow examines the issues related to a repurchase agreement. Repurchase Agreement Facts: Morgan Inc., an equipment dealer, sells equipment on January 1, 2020, to Lane Company for $100,000 It agrees to repurchase this equipment (an unconditional obligation) from Lane Company on December 31, 2021, for a price of $121,000. Question: Should Morgan Inc. record a sale for this transaction? Solution: For a sale and repurchase agreement, the terms of the agreement need to be analyzed to determine whether Morgan Inc. has transferred control to the customer, Lane Company. As indicated earlier, control of an asset refers to the ability to direct the use of and obtain substantially all the benefits from the asset. Control also includes the ability to prevent other companies from directing the use of and receiving the benefit from a good or service. In this case, Morgan Inc. continues to have control of the asset because it has agreed to repurchase the asset at an amount greater than the selling price. Therefore, this agreement is a financing transaction and not a sale. Thus, the asset is not removed from the books of Morgan Inc. Assuming that an interest rate of 10% is imputed from the agreement, Morgan Inc. makes the following entries to record this agreement. Morgan Inc. records the financing on January 1, 2020, as follows. January 1, 2020 Cash 100000 Liability to Lane Company 100000 Morgan Inc. records interest on December 31, 2020, as follows. December 31, 2020 Interest Expense 100000 Liability to Lane Company ($100,000 × .10) 100000 Morgan Inc. records interest and retirement of its liability to Lane Company as follows. - 109 - December 31, 2021 Interest Expense Liability to Lane Company ($110,000 × .10) Liability to Lane Company Cash ($100,000 + $10,000 + $11,000) 11000 11000 121000 121000 Rather than Morgan Inc. having a forward or call option to repurchase the asset, assume that Lane Company has the option to require Morgan Inc. to repurchase the asset at December 31, 2021. This option is a put option; that is, Lane Company has the option to put the asset back to Morgan Inc. In this situation, Lane Company has control of the asset as it can keep the equipment or sell it to Morgan Inc. or to some other third party. The value of a put option increases when the value of the underlying asset (in this case, the equipment) decreases. In determining how to account for this transaction, Morgan Inc. has to determine whether Lane Company will have an economic incentive to exercise this put option at the end of 2021. Specifically, Lane Company has a significant economic incentive to exercise its put option if the value of the equipment declines. In this case, the transaction is generally reported as a financing transaction as shown in Illustration 18.20. That is, Lane Company will return (put) the equipment back to Morgan Inc. if the repurchase price exceeds the fair value of the equipment. For example, if the repurchase price of the equipment is $150,000 but its fair value is $125,000, Lane Company is better off returning the equipment to Morgan Inc. Conversely, if Lane Company does not have a significant economic incentive to exercise its put option, then the transaction should be reported as a sale of a product with a right of return. Bill-and-Hold Arrangements A bill-and-hold arrangement is a contract under which an entity bills a customer for a product but the entity retains physical possession of the - 110 - product until it is transferred to the customer at a point in time in the future. Bill-and-hold sales result when the buyer is not yet ready to take delivery but does take title and accepts billing. For example, a customer may request a company to enter into such an arrangement because of (1) lack of available space for the product, (2) delays in its production schedule, or (3) more than sufficient inventory in its distribution channel. The following illustration provides an example of a bill-and-hold arrangement: Illustration 16: Recognition-Bill and Hold Bill and Hold Facts: Butler Company sells $450,000 (cost $280,000) of fireplaces on March 1, 2020, to a local coffee shop, Baristo, which is planning to expand its locations around the city. Under the agreement, Baristo asks Butler to retain these fireplaces in its warehouses until the new coffee shops that will house the fireplaces are ready. Title passes to Baristo at the time the agreement is signed. Question: When should Butler recognize the revenue from this bill and-hold arrangement? Solution: When to recognize revenue in a bill-and-hold arrangement depends on the circumstances. Butler determines when it has satisfied its performance obligation to transfer a product by evaluating when Baristo obtains control of that product. For Baristo to have obtained control of a product in a bill-and-hold arrangement, it must meet all of the conditions for change in control plus all of the following criteria: (a) The reason for the bill-and-hold arrangement must be substantive. (b) The product must be identified separately as belonging to Baristo. (c) The product currently must be ready for physical transfer to Baristo. (d) Butler cannot have the ability to use the product or to direct it to another customer. - 111 - In this case, assuming that the above criteria were met in the contract, revenue recognition should be permitted at the time the contract is signed. Butler has transferred control to Baristo; that is, Butler has a right to payment for the fireplaces and legal title has transferred.\ Butler makes the following entry to record the bill-and-hold sale and related cost of goods sold. March 1, 2020 Accounts Receivable Sales Revenue Cost of Goods Sold Inventory 450000 450000 280000 280000 Principal-Agent Relationships In a principal-agent relationship, the principal’s performance obligation is to provide goods or perform services for a customer. The agent’s performance obligation is to arrange for the principal to provide these goods or services to a customer. Examples of principal-agent relationships are as follows. • Preferred Travel Company (agent) facilitates the booking of cruise excursions by finding customers for Regency Cruise Company (principal). • Priceline (agent) facilitates the sale of various services such as car rentals for Hertz (principal). In these types of situations, amounts collected on behalf of the principal are not revenue of the agent. Instead, revenue for the agent is the amount of the commission it receives (usually a percentage of total revenue). The following illustration provides an example of the issues related to principal-agent relationships: - 112 - Illustration: Recognition-Principal-Agent Relationship: Principal-Agent Relationship Facts: Fly-Away Travel sells airplane tickets for British Airways (BA) to various customers. Question: What are the performance obligations in this situation and how should revenue be recognized for both the principal and agent? Solution: The principal in this case is BA and the agent is Fly-Away Travel. Because BA has the performance obligation to provide air transportation to the customer, it is the principal. Fly-Away Travel facilitates the sale of the airline ticket to the customer in exchange for a fee or commission. Its performance obligation is to arrange for BA to provide air transportation to the customer. Although Fly-Away collects the full airfare from the customer, it then remits this amount to BA less the commission. Fly-Away therefore should not record the full amount of the fare as revenue on its booksto do so overstates revenue. Its revenue is the commission, not the full price. Control of performing the air transportation is with BA, not Fly-Away Travel. Some might argue that there is no harm in letting Fly-Away record revenue for the full price of the ticket and then charging the cost of the ticket against the revenue (often referred to as the gross method of recognizing revenue). Others note that this approach overstates the agent’s revenue and is misleading. The revenue received is the commission for providing the travel services, not the full fare price (often referred to as the net approach). The profession believes the net approach is the correct method for recognizing revenue in a principal-agent relationship. As a result, the FASB has developed specific criteria to determine when a principal-agent relationship exists.12 An important feature in deciding whether Fly-Away is acting as an agent is whether the - 113 - amount it earns is predetermined, being either a fixed fee per transaction or a stated percentage of the amount billed to the customer. Warranties Companies often provide one of two types of warranties to customers: 1.Warranties that the product meets agreed-upon specifications in the contract at the time the product is sold. This type of warranty is included in the sales price of a company’s product and is often referred to as an assurance-type warranty. 2.Warranties that provide an additional service beyond the assurancetype warranty. This warranty is not included in the sales price of the product and is referred to as a service-type warranty. As a consequence, it is recorded as a separate performance obligation. Companies do not record a separate performance obligation for assurance-type warranties. This type of warranty is nothing more than a quality guarantee that the good or service is free from defects at the point of sale. In this case, the sale of the product and the related assurance warranty are one performance obligation as they are interdependent of and interrelated with each other. The objective for companies that issue an assurance warranty is to provide a combined item (product and a warranty). These types of obligations should be expensed in the period the goods are provided or services performed. In addition, the company should record a warranty liability. The estimated amount of the liability includes all the costs that the company is expected to incur after sale due to the correction of defects or deficiencies required under the warranty provisions. In addition, companies sometimes provide customers with an option to purchase a warranty separately. In most cases, these extended warranties provide the customer a service beyond fixing defects that existed at the time of sale. For example, when you purchase a TV, you are - 114 - entitled to the company’s warranty. You will also undoubtedly be offered an extended warranty on the product at an additional cost. These servicetype warranties represent a separate service and are an additional performance obligation. The service-type warranty is sold separately and therefore has a standalone selling price. In this case, the objective of the company is to sell an additional service to customers. As a result, companies should allocate a portion of the transaction price to this performance obligation, if provided. The company recognizes revenue in the period that the service-type warranty is in effect. The following illustration presents an example of both an assurance-type and a service-type warranty. Warranties Facts: Maverick Company sold 1,000 Rollomatics on October 1, 2020, at total price of $6,000,000, with a warranty guarantee that the product was free of defects. The cost of the Rollomatics is $4,000,000. The term of this assurance warranty is 2 years, which Maverick estimates will cost $80,000. In addition, Maverick sold extended warranties related to 400 Rollomatics for 3 years beyond the 2-year period for $18,000. On November 22, 2020, Maverick incurred labor costs of $3,000 and part costs of $25,000 related to the assurance warranties. Maverick prepares financial statements on December 31, 2020. It estimates that its future assurance warranty costs will total $44,000 at December 31, 2020. Question: What are the journal entries that Maverick Company should make in 2020 related to the sale of the Rollomatics and the assurance and extended warranties? Solution: Maverick makes the following entries in 2020 related to Rollomatics sold with warranties. October 1, 2020 To record the sale of the Rollomatics and the related extended warranties: Cash ($6,000,000 + $18,000) 6018000 Sales Revenue 600000 - 115 - Unearned Warranty Revenue 18000 To record the cost of goods sold and reduce the inventory of Rollomatics: Cost of Goods Sold 4000000 Inventory 4000000 November 22, 2020 To record the warranty costs incurred: Warranty Expense Salaries and Wages Payable Inventory (parts) December 31, 2020 28000 3000 25000 To record the adjusting entry related to its assurance warranty at the end of the year: Warranty Expense Warranty Liability 44000 44000 Maverick Company makes an adjusting entry on December 31, 2020, to record a liability for the expected warranty costs related to the sale of the Rollomatics. When actual warranty costs are incurred in 2021, the Warranty Liability account is reduced. In most cases, Unearned Warranty Revenue (related to the servicetype warranty) is recognized on a straight-line basis as Warranty Revenue over the three-year period to which it applies. Revenue related to the extended warranty is not recognized until the warranty becomes effective on October 1, 2022. If financial statements are prepared on December 31, 2022, Maverick makes the following entry to recognize revenue: Unearned Warranty Revenue Warranty Revenue [($18,000 ÷ 36) × 3] 1,500 1,500 Maverick Company reduces the Warranty Liability account over the warranty period as the actual warranty costs are incurred. The company also recognizes revenue related to the service-type warranty over the three-year period that extends beyond the assurance warranty - 116 - period (two years). In most cases, the unearned warranty revenue is recognized on a straight-line basis. The costs associated with the servicetype warranty are expensed as incurred. Nonrefundable Upfront Fees Companies sometimes receive payments (upfront fees) from customers before they deliver a product or perform a service. Upfront payments generally relate to the initiation, activation, or setup of a good or service to be provided or performed in the future. In most cases, these upfront payments are nonrefundable. Examples include fees paid for membership in a health club or buying club, and activation fees for phone, Internet, or cable. Companies must determine whether these nonrefundable advance payments are for products or services in the current period. In most situations, these payments are for future delivery of products and services and should therefore not be recorded as revenue at the time of payment. In some cases, the upfront fee is viewed similar to a renewal option for future products and services at a reduced price. An example would be a health club where once the initiation fee is paid, no additional fee is necessary upon renewal. The following illustration provides an example of an upfront fee payment. Upfront Fee Considerations Facts: Erica Felise signs a 1-year contract with Bigelow Health Club. The terms of the contract are that Erica is required to pay a non-refundable initiation fee of $200 and a membership fee of $50 per month. Bigelow determines that its customers, on average, renew their annual membership two times before terminating their membership. Question: What is the amount of revenue Bigelow Health Club should recognize in the first year? Solution: In this case, the membership fee arrangement may be viewed as a single performance obligation (similar services are provided in all periods). That is, Bigelow is providing a discounted price in the second - 117 - and third years for the same services, and this should be reflected in the revenue recognized in those periods. Bigelow determines the total transaction price to be $2,000—the upfront fee of $200 and the three years of monthly fees of $1,800 ($50 × 36)—and allocates it over the three years. In this case, Bigelow would report revenue of $55.56 ($2,000 ÷ 36) each month for three years. Unless otherwise instructed, use this approach for homework problems. Long-Term Construction Contracts Revenue Recognition over Time For the most part, companies recognize revenue at the point of sale because that is when the performance obligation is satisfied. However, as indicated in the chapter, under certain circumstances companies recognize revenue over time. The most notable context in which revenue is recognized over time is long-term construction contract accounting. Long-term contracts frequently provide that the seller (builder) may bill the purchaser at intervals, as it reaches various points in the project. Examples of long-term contracts are construction-type contracts, development of military and commercial aircraft, weaponsdelivery systems, and space exploration hardware. When the project consists of separable units, such as a group of buildings or miles of roadway, contract provisions may provide for delivery in installments. In that case, the seller would bill the buyer and transfer title at stated stages of completion, such as the completion of each building unit or every 10 miles of road. The accounting records should record sales when installments are “delivered.” A company satisfies a performance obligation and recognizes revenue over time if at least one of the following three criteria is met: - 118 - 1. The customer simultaneously receives and consumes the benefits of the seller’s performance as the seller performs. 2. The company’s performance creates or enhances an asset (for example, work in process) that the customer controls as the asset is created or enhanced; or 3. The company’s performance does not create an asset with an alternative use. For example, the asset cannot be used by another customer. In addition to this alternative use element, at least one of the following criteria must be met: a. Another company would not need to substantially re-perform the work the company has completed to date if that other company were to fulfill the remaining obligation to the customer. b. The company has a right to payment for its performance completed to date, and it expects to fulfill the contract as promised. Therefore, if criterion 1, 2, or 3 is met, then a company recognizes revenue over time if it can reasonably estimate its progress toward satisfaction of the performance obligations. That is, it recognizes revenues and gross profits each period based upon the progress of the construction-referred to as the percentage-of-completion method. The company accumulates construction costs plus gross profit recognized to date in an inventory account (Construction in Process), and it accumulates progress billings in a contra inventory account (Billings on Construction in Process). The rationale for using percentage-of-completion accounting is that under most of these contracts the buyer and seller have enforceable rights. The buyer has the legal right to require specific performance on the contract. The seller has the right to require progress payments that provide evidence of the buyer’s ownership interest. As a result, a continuous sale occurs as the work progresses. Companies should recognize revenue according to that progression. - 119 - Alternatively, if the criteria for recognition over time are not met (e.g., the company does not have a right to payment for work completed to date), the company recognizes revenues and gross profit at a point in time, that is, when the contract is completed. This approach is referred to as the completed-contract method. The company accumulates construction costs in an inventory account (Construction in Process), and it accumulates progress billings in a contra inventory account (Billings on Construction in Process). Percentage-of-Completion Method The percentage-of-completion method recognizes revenues, costs, and gross profit as a company makes progress toward completion on a longterm contract. To defer recognition of these items until completion of the entire contract is to misrepresent the efforts (costs) and accomplishments (revenues) of the accounting periods during the contract. In order to apply the percentage-of-completion method, a company must have some basis or standard for measuring the progress toward completion at particular interim dates. Measuring the Progress Toward Completion As one practicing accountant wrote, “The big problem in applying the percentage-of-completion method . .. has to do with the ability to make reasonably accurate estimates of completion and the final gross profit.” Companies use various methods to determine the extent of progress toward completion. The most common are the cost-to-cost and units ofdelivery methods. As indicated in the chapter, the objective of all these methods is to measure the extent of progress in terms of costs, units, or value added. Companies identify the various measures (costs incurred, labor hours worked, tons produced, floors completed, etc.) and classify them as input or output measures. Input measures (costs incurred, labor hours worked) are efforts devoted to a contract. Output measures (with units of delivery measured as tons produced, floors of a building completed, miles - 120 - of a highway completed) track results. Neither measure is universally applicable to all long-term projects. Their use requires the exercise of judgment and careful tailoring to the circumstances. Both input and output measures have disadvantages. The input measure is based on an established relationship between a unit of input and productivity. If inefficiencies cause the productivity relationship to change, inaccurate measurements result. Another potential problem is front-end loading, in which significant upfront costs result in higher estimates of completion. To avoid this problem, companies should disregard some early-stage construction costs—for example, costs of uninstalled materials or costs of subcontracts not yet performed-if they do not relate to contract performance. Similarly, output measures can produce inaccurate results if the units used are not comparable in time, effort, or cost to complete. For example, using floors (stories) completed can be deceiving. Completing the first floor of an eight-story building may require more than one-eighth the total cost because of the substructure and foundation construction. The most popular input measure used to determine the progress toward completion is the cost-to-cost basis. Under this basis, a company like Halliburton measures the percentage of completion by comparing costs incurred to date with the most recent estimate of the total costs required to complete the contract. The formula for the cost-to-cost basis takes is presented as follows: Formula for Percentage-of-Completion, Cost-to-Cost Basis: Costs Incurred to Date = percentage complete Most Recent Estimate of Total Costs Once Halliburton knows the percentage that costs incurred bear to total estimated costs, it applies that percentage to the total revenue or the - 121 - estimated total gross profit on the contract. The resulting amount is the revenue or the gross profit to be recognized to date. Formula for Total Revenue (or Gross Profit) to Be Recognized to Date: Percent complete x Estimated Total revenue = (or Gross Profit) Revenue (or Gross Profit) to Be Recognized to Date To find the amounts of revenue and gross profit recognized each period, Halliburton subtracts total revenue or gross profit recognized in prior periods: Formula for Amount of Current-Period Revenue (or Gross Profit) Costto-Cost Basis Revenue (or gross profit) to be recognized to Date Revenue (or gross Current-period profit) recognized = Revenue (or in Prior periods Gross Profit) Because the cost-to-cost method is widely used (without excluding other bases for measuring progress toward completion), we have adopted it for use in our examples. Example of Percentage-of-Completion Method-Cost-to-Cost Basis To illustrate the percentage-of-completion method, assume that Hardhat Construction Company has a contract to construct a $4,500,000 bridge at an estimated cost of $4,000,000. The contract is to start in July 2020, and the bridge is to be completed in October 2022. The following data pertain to the construction period. (Note that by the end of 2021, Hardhat has revised the estimated total cost from $4,000,000 to $4,050,000.) 2020 Costs to date $1000000 3000000 Estimated costs to complete Progress billings during the year 900000 750000 Cash collected during the year 2021 $2916000 1134000 2400000 1750000 2022 $4050000 1200000 2000000 Hardhat would compute the percent complete as shown below: - 122 - Contract price Less estimated cost: Costs to date Estimated costs to complete Estimated total costs Estimated total gross profit Percent complete 2020 $4500000 2021 $4500000 2022 $4500000 1000000 3000000 4000000 $2916000 1134000 4050000 4050000 -4050000 $500000 $450000 $450000 72% 25% ($1000000) ($2916000) ($4000000) ($4050000) 100% ($4050000) ($4050000) On the basis of the data above, Hardhat would make the entries shown below to record (1) the costs of construction, (2) progress billings, and (3) collections. These entries appear as summaries of the many transactions that would be entered individually as they occur during the year. 2020 2021 2022 To record costs of construction: Construction in Process 1000000 1916000 1134000 Materials, Cash, Payables, etc. 1000000 1916000 1134000 To record progress billings: 2400000 900000 1200000 Accounts Receivable 2400000 900000 1200000 Billings on Construction in Process To record collections: Cash 750000 1750000 2000000 Accounts Receivable 750000 1750000 2000000 In this example, the costs incurred to date are a measure of the extent of progress toward completion. To determine this, Hardhat evaluates the costs incurred to date as a proportion of the estimated total costs to be incurred on the project. The estimated revenue and gross profit that Hardhat will recognize for each year are calculated as shown below: - 123 - Recognized in Prior Years To Date 2020 Revenues ($4500000 x .25) Costs Gross profit 2021 Revenues ($4500000 x .72) Costs Gross profit 2022 Revenues ($4500000 x 1.00) Costs Gross profit Recognized in current year $1125000 1000000 $125000 $1125000 1000000 $125000 3240000 2916000 324000 $1125000 1000000 $125000 $2115000 1916000 $199000 $4500000 4050000 $450000 $3240000 2916000 $3240000 $2160000 1134000 $1260000 Furthermore, Hardhat’s entries to recognize revenue and gross profit each year and to record completion and final approval of the contract is shown below: 2020 To recognize revenue and gross profit: Construction in Process(gross profit) Construction Expenses Contracts To record completion of the contract: Billings on Construction in Process Construction in Process 2021 2022 $125000 $199000 $126000 1000000 1916000 1134000 $1125000 2115000 $1260000 - - $4500000 4500000 Note that Hardhat debits gross profit to Construction in Process. Similarly, it credits Revenue from Long Term Contracts for the amounts computed. Hardhat then debits the difference between the amounts recognized each year for revenue and gross profit to a nominal account, Construction Expenses (similar to Cost of Goods Sold in a manufacturing company). It reports that amount in the income statement as the actual cost of construction incurred in that period. For example, in 2020 Hardhat - 124 - uses the actual costs of $1,000,000 to compute both the gross profit of $125,000 and the percent complete (25 percent). Hardhat continues to accumulate costs in the Construction in Process account, in order to maintain a record of total costs incurred (plus recognized gross profit) to date. Although theoretically a series of “sales” takes place using the percentage-of completion method, the selling company cannot remove the inventory cost until the construction is completed and transferred to the new owner. Hardhat’s Construction in Process account for the bridge would include the summarized entries shown below over the term of the construction project. Construction in Process 2020 construction costs $1000000 31/12/22 To close project 2020 recognized gross profit 125000 2021 construction costs 1916000 2021 recognized gross profit 199000 2022 construction costs 1134000 2022 recognized gross profit 126000 Total $4500000 Total complete $4500000 $4500000 Recall that the Hardhat Construction Company example contained a change in estimated costs: In the second year, 2021, it increased the estimated total costs from $4,000,000 to $4,050,000. The change in estimate is accounted for in a cumulative catch-up manner, as indicated in the chapter. This is done by first adjusting the percent completed to the new estimate of total costs. Next, Hardhat deducts the amount of revenues and gross profit recognized in prior periods from revenues and gross profit computed for progress to date. That is, it accounts for the change in estimate in the period of change. That way, the balance sheet at the end of the period of change and the accounting in subsequent periods are as they would have been if the revised estimate had been the original estimate. - 125 - Financial Statement Presentation-Percentage-of-Completion Generally, when a company records a receivable from a sale, it reduces the Inventory account. Under the percentage-of-completion method, however, the company continues to carry both the receivable and the inventory. Subtracting the balance in the Billings account from Construction in Process avoids double counting the inventory. During the life of the contract, Hardhat reports in the balance sheet the difference between the Construction in Process and the Billings on Construction in Process accounts. If that amount is a debit, Hardhat reports it as a current asset; if it is a credit, it reports it as a current liability. At times, the costs incurred plus the gross profit recognized to date (the balance in Construction in Process) exceed the billings. In that case, Hardhat reports this excess as a current asset entitled “Costs and recognized profit in excess of billings.” Hardhat can at any time calculate the unbilled portion of revenue recognized to date by subtracting the billings to date from the revenue recognized to date, as illustrated for 2020 for Hardhat Construction in Illustration 18A.9. Contract revenue recognized to date: $4500000 x Billings to date Unbilled revenue $1000000 $1125000 4000000 (900000) $225000 At other times, the billings exceed costs incurred and gross profit to date. In that case, Hardhat reports this excess as a current liability entitled “Billings in excess of costs and recognized profit.” What happens, as is usually the case, when companies have more than one project going at a time? When a company has a number of projects, costs exceed billings on some contracts and billings exceed costs on others. In such a case, the company segregates the contracts. The asset side includes only those contracts on which costs and recognized profit exceed billings. The liability side includes only those on which - 126 - billings exceed costs and recognized profit. Separate disclosures of the dollar volume of billings and costs are preferable to a summary presentation of the net difference. Using data from the bridge example, Hardhat Construction Company would report the status and results of its long-term construction activities in 2020 under the percentage-of-completion method as shown below. Financial Statement Presentation-Percentage-of-Completion Method (2020) Hardhat Construction Company Income Statement Revenue from long-term contracts Costs of construction Gross profit 2020 $1125000 1000000 $ 125000 2020 Balance Sheet (12/31) Current assets: Accounts receivable Inventory: Construction in process Less: Billings 1125000 $1125000 900000 Costs and recognized profit in excess of billings 225000 Financial Statement Presentation-Percentage-of-Completion Method (2021) Hardhat Construction Company 2021 Income Statement Revenue from long-term contracts $2115000 Costs of construction 1916000 Gross profit $ 199000 Balance Sheet (12/31) Current assets: Accounts receivable (150000+ 2400000 – 1750000) Current liabilities - 127 - 2020 800000 Billings $3300000 Less: Construction in process 3240000 Billings in excess of costs and recognized 60000 profit In 2022, as shown in the table below, Hardhat’s financial statements only include an income statement because the bridge project was completed and settled. Hardhat Construction Company Income Statement Revenue from long-term contracts Costs of construction Gross profit 2022 $1269000 1134000 $ 126000 Completed-Contract Method Under the completed-contract method, companies recognize revenue and gross profit only at point of sale-that is, when the contract is completed. Under this method, companies accumulate costs of long term contracts in process, but they make no interim charges or credits to income statement accounts for revenues, costs, or gross profit. The principal advantage of the completed-contract method is that reported revenue reflects final results rather than estimates of unperformed work. Its major disadvantage is that it does not reflect current performance when the period of a contract extends into more than one accounting period. Although operations may be fairly uniform during the period of the contract, the company will not report revenue until the year of completion, creating a distortion of earnings. Under the completed-contract method, the company would make the same annual entries to record costs of construction, progress billings, and collections from customers as those illustrated under the percentageof-completion method. The significant difference is that the company would not make entries to recognize revenue and gross profit. - 128 - For example, under the completed-contract method for the bridge project previously illustrated, Hardhat Construction Company would make the following entries in 2022 to recognize revenue and costs and to close out the inventory and billing accounts. Billings on Construction in Process Revenue from Long-Term Contracts Costs of Construction Construction in Process 4500000 4500000 4500000 4500000 The table compares the amount of gross profit that Hardhat Construction Company would recognize for the bridge project under the two revenue recognition methods. Comparison of Gross Profit Recognized under Different Method Percentage-of-completion Completed-contract 2020 $125000 $0 2021 199000 0 2022 126000 450000 Financial Statement Presentation-Completed Contract Method Hardhat Construction Company 2020 2021 2022 - - $4500000 4050000 $450000 2020 2021 2022 $150000 $800000 $-0- Income statement Revenue from long-term contracts Costs of construction Gross profit Hardhat Construction Company Balance Sheet (31/12) Current assets: Accounts receivable Inventory: Construction in process Less: Billings $1000000 900000 - 129 - Costs in excess of Billings Current liabilities: Billings (3300000) in excess of costs ($2916000) 100000 $-0- 384000 $-0- Note 1. Summary of significant accounting policies. Long-Term Construction Contracts. The company recognizes revenues and reports profits from long-term construction contracts, its principal business, under the completed contract method. These contracts generally extend for periods in excess of one year. Contract costs and billings are accumulated during the periods of construction, but no revenues or profits are recognized until completion of the contract. Costs included in construction in process include direct material, direct labor, and project related overhead. Corporate general and administrative expenses are charged to the periods as incurred. Long-Term Contract Losses Two types of losses can become evident under long-term contracts: - Loss in the current period on a profitable contract. This condition arises when, during construction, there is a significant increase in the estimated total contract costs but the increase does not eliminate all profit on the contract. Under the percentage-of-completion method only, the estimated cost increase requires a current-period adjustment of excess gross profit recognized on the project in prior periods. The company records this adjustment as a loss in the current period because it is a change in accounting estimate. - Loss on an unprofitable contract. Cost estimates at the end of the current period may indicate that a loss will result on completion of the entire contract. Under both the percentage-of-completion and the completed-contract methods, the company must recognize in the current period the entire expected contract loss. The treatment described for unprofitable contracts is consistent with the accounting custom of anticipating foreseeable losses to avoid overstatement of current and future income (conservatism). - 130 - Loss in Current Period To illustrate a loss in the current period on a contract expected to be profitable upon completion, we will continue with the Hardhat Construction Company bridge project. Assume that on December 31, 2021, Hardhat estimates the costs to complete the bridge contract at $1468962 instead of $1134000. Assuming all other data are the same as before, The “percent complete” has dropped, from 72 percent to 66½ percent, due to the increase in estimated future costs to complete the contract. Computation of Recognizable Loss, 2021-Loss in Current Period: Cost to date (3112//21) Estimated costs to complete (revised) Estimated total costs Percent complete ($2916000 ÷ $4384962) Revenue recognized in 2021 ($4500000 × .665) - $1125000 Costs incurred in 2021 Loss recognized in 2021 $2916000 1468962 $4384962 66½% $1867500 1916000 $ (48500) The 2021 loss of $48500 is a cumulative adjustment of the “excessive” gross profit recognized on the contract in 2020. Instead of restating the prior period, the company absorbs the prior period misstatement entirely in the current period. In this illustration, the adjustment was large enough to result in recognition of a loss. Hardhat Construction would record the loss in 2021 as follows. Construction Expenses Construction in Process (loss) Revenue from Long-Term Contracts 1916000 48500 1867500 Hardhat will report the loss of $48500 on the 2021 income statement as the difference between the reported revenue of $1867500 and the costs - 131 - of $1916000. Under the completed-contract method, the company does not recognize a loss in 2021. Why not? Because the company still expects the contract to result in a profit, to be recognized in the year of completion. Loss on an Unprofitable Contract To illustrate the accounting for an overall loss on a long-term contract, assume that at December 31, 2021, Hardhat Construction Company estimates the costs to complete the bridge contract at $1640250 instead of $1134000. Revised estimates for the bridge contract are as follows. Contract price Estimated total cost Estimated gross profit Estimated loss *($2,916,000 + $1,640,250) 2020 Original Estimates $4500000 4000000 $500000 2021 Revised Estimates $4500000 4556250* $ (56250) Under the percentage-of-completion method, Hardhat recognized $125000 of gross profit in 2020 (see Illustration 18A.6). This amount must be off set in 2021 because it is no longer expected to be realized. In addition, since losses must be recognized as soon as estimable, the company must recognize the total estimated loss of $56250 in 2021. Therefore, Hardhat must recognize a total loss of $181250 ($125000 + $56250) in 2021. The following table shows Hardhat’s computation of the revenue to be recognized in 2021. Revenue recognized in 2021: Contract price Percent complete Revenue recognizable to date $4500000 × .64* 2880000 - 132 - Less: Revenue recognized prior to 2021 Revenue recognized in 2021 1125000 $1755000 *Cost to date (12/31/21) Estimated cost to complete Estimated total costs $2916000 1640250 $4556250 Percent complete: $2916000 ÷ $4556250 = 64% To compute the construction costs to be expensed in 2021, Hardhat adds the total loss to be recognized in 2021 ($125,000 + $56,250) to the revenue to be recognized in 2021. The table below shows this computation. Revenue recognized in 2021 (computed above) Total loss recognized in 2021 Reversal of 2020 gross profit Total estimated loss on the contract Construction cost expensed in 2021 $1755000 $125000 56250 $125000 181250 $1936250 Hardhat Construction would record the long-term contract revenues, expenses, and loss in 2021 as follows. Construction Expenses Construction in Process (loss) Revenue from Long-Term Contracts 1936250 181250 1755000 At the end of 2021, Construction in Process has a balance of $2859750 as shown in the following table: Construction in Process 2020 Construction costs 1000000 2020 Recognized gross profit 125000 2021 Construction costs 1916000 2021 Recognized loss Balance 2859750 - 133 - 181250 Under the completed-contract method, Hardhat also would recognize the contract loss of $56,250 through the following entry in 2021 (the year in which the loss first became evident). Loss from Long-Term Contracts Construction in Process (loss) 56,250 56,250 Just as the Billings account balance cannot exceed the contract price, neither can the balance in Construction in Process exceed the contract price. In circumstances where the Construction in Process balance exceeds the billings, the company can deduct the recognized loss from such accumulated costs on the balance sheet. That is, under both the percentage-of-completion and the completed-contract methods, the provision for the loss (the credit) may be combined with Construction in Process, thereby reducing the inventory balance. In those circumstances, however (as in the 2021 example above), where the billings exceed the accumulated costs, Hardhat must report separately on the balance sheet, as a current liability, the amount of the estimated loss. That is, under both the percentage-of-completion and the completed-contract methods, Hardhat would take the $56,250 loss, as estimated in 2021, from the Construction in Process account and report it separately as a current liability titled “Estimated liability from long-term contracts.” - 134 -