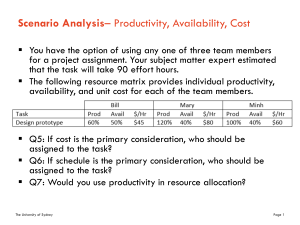

Teachers as curriculum arbiters and navigators Presented by Professor Valerie Harwood Lecture developed by Dr Samantha McMahon Sydney School of Education and Social Work The University of Sydney Page 1 This week we are focusing on: teachers – teaching – curriculum How do we think about this…? How do we think about teachers and curriculum and knowledge? The University of Sydney Page 2 The lecture – – – – Excerpt from the start of the reading What might the simile in the lecture title mean? What you know impacts what you do (and how you teach) Arbitration, navigation and teachers’ knowledge of curriculum – Arbitration, navigation and teachers’ knowledge of learners Two channels of teacher education – content and pedagogic reasoning. The University of Sydney Page 3 The following slide contains an excerpt from the start of this week’s reading by Comber & Kamler (2004). The University of Sydney Page 4 “Well, as I said before, it has a lot to do with work ethic of the parents, and although the Early Years program is very structured and doesn't leave a whole lot of room for teacher error, you're always going to need the support of parents, and if the parents aren't giving as much support, the students won't show it in their work. You know it from class to class. You see groups of children in my class that are doing the best. I've met their parents, they've all come and made themselves very known to me, and just through speaking to them you know what goes on at home and you know that they do have a stronger work ethic and help their kids at home as well. I think that's huge. The parents do need to help. We've got structures in place to teach at school, but then it needs to be backed up at home.” (Marc, cited in Comber and Kamler, 2004, p.298) The University of Sydney Page 5 Teachers as curriculum arbiters and navigators What might the simile in lecture title mean? The University of Sydney Page 6 ARBITER (noun): 1. gen. One whose opinion or decision is authoritative in a matter of debate; a judge. 2. spec. One who is chosen by the two parties in a dispute to arrange or decide the difference between them; an arbitrator, an umpire. 3. One who has power to decide or ordain according to his[sic] own absolute pleasure; one who has a matter under his [sic] sole control. Also fig 4. ǁ arbiter elegantiarum, arbiter elegantiae [Latin, lit. ‘judge of elegance’: Petronius Arbiter was the elegantiae arbiter of Nero's court (Tacitus Ann. xvi. 18)] , a judge of matters of taste, an authority on etiquette. (Oxford Online Dictionary, 2018a) In what way might teachers be considered arbiters of curriculum? The University of Sydney Page 7 NAVIGATOR, n. 1. A person who navigates. a. A sailor, esp. one …responsible for directing the course of a particular vessel. b. a person who plots and directs the course of an aircraft or spacecraft. c. A person who directs the course of a motor vehicle; a person who map-reads for, or gives directions to, the driver of a motor vehicle. 3. Computing. Categories » a. A person who searches large computer databases… b. A program which searches for and locates data about a specified topic from the Internet or other data collection; …any program or device designed to help a user move around an interface, program, etc. (Oxford Online Dictionary, 2018b) Discuss: In what way might teachers be considered navigators of curriculum? The University of Sydney – Page 8 What you know impacts what you do (and how you teach) The University of Sydney Page 9 Trevor Gale, Carmen Mills, Russell Cross This idea of the relationship between knowing and doing is at the centre of educational thinking and practice. In 2017 these three academics released a theoretical paper demonstrating the centrality of knowledge and belief in pedagogic work especially, now. The University of Sydney Page 10 This work by Gale and colleagues affirms that what we believe and know impacts what we do as educators in the community and in the classroom. OUR CHOICES about what and how we teach something craft different learning opportunities and educational experiences for our students. This makes our decisions as educators important ethical and political actions. WAIT – what do we mean by political? One way of thinking about the political is to think about the ‘polis’, the idea of people together, contributing. The idea of the polis is discussed in rich detail by Hannah Arendt. For Arendt (1968) the purpose of the political, “…would be to establish and keep in existence a space where freedom as virtuosity can appear. This is the realm where freedom is a worldly reality, tangible in words which can be heard, in deeds which can be seen, and in events which are talked about, remembered… Whatever occurs in this space of appearances is political by definition...” (p.154–5) The University of Sydney Page 11 349 Gale et al. Figure 1. Elements of Pedagogic Work: belief, design, action. The University of Sydney (Gale et al. 2017, p.349) pedagogy are represented by Figure 1 below and discussed in the sections that follow. Page 12 Attempts to define “good” teaching as the basis to evaluate and improve the professional standards of teachers has gained traction across OECD nations, particularly in the You don’t have to understand in detail this diagram – it is being used to show that educator knowledge and beliefs are at the apex, sitting at the top of the triangle on current theorizations of pedagogical work. This reminds us that whilst examples in this lecture might be specific, the issue is foundational to contemporary educational practice. We use our knowledge and beliefs as chief currency in our work as curriculum arbiters and navigators. The University of Sydney Page 13 Curriculum arbitration, navigation and teachers’ knowledge of curriculum The University of Sydney Page 14 Image caption The University of Sydney Page 15 Building a case for multiple ‘ways of knowing Drawing on ideas from Michel Foucault • Discourse, discipline, knowledge. • What each of these pictures represented was a certain discourse (or way of knowing and talking) about eggplants. • Multiple knowledges of eggplants J. • Discourses do stuff! They form objects, inform how we say things, form concepts AND strategies (Foucault 1972). • Discourses limit the sayable, repeatable and doable (Kendall & Wickham, 1999) • Discourses do this, in part, by providing you with a position in relation to the ‘thing’ to be known. • What you know => tells you something about who you are (your positionality) => What you say and do. (see also, McMahon & Harwood, 2016) The University of Sydney (see also, Foucault 1972, Gutting 2003) Page 16 For a botanist the eggplant is an object of study, a thing to be understood. In this case the scientist is positioned as the knower of eggplants. The University of Sydney Page 17 A farmer will view the eggplant as a thing to be nurtured and protected from threats such as birds, insects and extreme weather. They might position themselves as protectors of the eggplant The University of Sydney Page 18 Image caption The University of Sydney A dietician might see the eggplant as merely the sum of its nutritional parts, a single piece in a informational jigsaw piece for them to manipulate when providing dietetic advice to a patient. They might position themselves as eggplant problem solvers. Page 19 Image caption The University of Sydney The economist will think of the eggplant in terms of data. And themselves as data analysts. Page 20 For the chef, the eggplant is a material to be manipulated and used in the construction of culinary their arts. They may consider themselves eggplant artists?!?!?! Image caption The University of Sydney Page 21 The different ways of knowing give each of our knowers a different subject position in relationship with the eggplant: • • • • • expert, protector, problem solver, data analyst, artist. So what happens if each knower is given a kitchen knife and an eggplant? The University of Sydney Page 22 The chef would never pick up a knife, then carefully and slowly vertically dissect the eggplant then pull out a piece of paper and pencil to draw the seed placements … but a botanist would (and they would use a scalpel). The chef would gladly and expertly wield a kitchen knife to shape the eggplant appropriately for incorporation in this art. Diced, sliced etc. But the farmer would never think to pick up a knife or plunge a knife into the thing they may be protecting it from all damage so it may fully grow before selling it at market. The dietician and the economist arguably wouldn’t ever think to pick up a knife in their professional dealings with eggplants information. The limits of what you know (or discourses or ways of knowing) impacts what you say AND do. Image caption The University of Sydney Knowing yourself, your knowledge and your positionality as a teacher is a very important starting point in deciding how to teach the curriculum content to students. Page 23 This is what Year 6 students have to know about food and fibre production and management and its relationship to health and wellbeing. Question: Will all primary school teachers go about teaching this content in the same way? YOUR POSITIONALITY, PRIOR KNOWLEDGE AND Disciplinary PREDISPOSITIONS as a teacher MEANS YOU WILL READ THIS DOCUMENT IN A UNIQUE WAY. The University of Sydney Page 24 (Screenshot with overlay: https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/resources/curriculumconnections/dimensions/?Id=46751&Subjects=45760&Subjects=45758& Subjects=45721&Subjects=45753&Subjects=45720&isFirstPageLoad=f alse) The University of Sydney Page 25 Two year 6 classrooms… Classroom #1 Foody, creative arts, predisposed to the creative process – you might respond very differently to this content elaboration compared to a teacher who has strengths in science and experimental design / controlling variables. The first teacher might ask to work in groups to design and develop a way of making eggplants presentable and palatable to younger eaters; Classroom #2 Solve a maths problem that involves comparing and contrasting the health benefits of swapping out a single ingredient in a recipe (different nutritional values of chicken v. eggplant parmigiana, then ask you to repeat this ‘change one variable’ evaluation on a recipe of your choice). “Equipment” to the first teacher might be cookie cutters, spiral peelers, food processor and an entire kitchen pantry, whilst in the second it might mean supermarket brochures, kitchen scales and a calculator). – – – Do you think students in one of these classrooms are getting a better educational ‘deal’ compared with the other classroom? Are there any equity issues here? If everyone know the same outcome is it okay that different teachers will teach it differently? Why? Has to In what ways were these two teachers arbiters or negotiators of curriculum? (maybe think back on those definitions from the start of the lecture) The University of Sydney Page 26 Key messages The University of Sydney – What you know impacts what you say and do. (Discourses do stuff!) – Each discourse places you in a particular relationship to the thing you know (‘subject position’ or positionality). – Positionality impacts your decisions of how to interpret, curate and teach curriculum. – This impacts learners. So, teacher knowledge and teacher decisions matter in ethical and political ways. Page 27 Curriculum arbitration, navigation and teachers’ knowledge of students The University of Sydney Page 28 Would you coach basketball the same way if: – Your team are top of the national basketball league – Your team normally plays national netball but are training for a charity basketball match – Your team are wheelchair users – Your team are octogenarians? – Your school is trying lunchtime basketball instead of detention and your team has been in significant trouble with classroom teachers that morning. The University of Sydney Why? Why not? Page 29 Getting out of deficit: Pedagogies of reconnection (Comber and Kamler, 2004) The University of Sydney Page 30 Marc turns around to Willem (Comber & Kamler, 2004) In the beginning “New knowledge” Then… Deficit understandings of families when he hadn’t met the parents. “never completing writing tasks”, “little motivation toward reading books from the provided book boxes”, “simply disinterested in set work” (p. 299) The University of Sydney Page 31 Marc turns around to Willem (Comber & Kamler, 2004) In the beginning “New knowledge” Deficit understandings of families when he hadn’t met the parents. The non reader can read! “never completing writing tasks”, “little motivation toward reading books from the provided book boxes”, “simply disinterested in set work” (p. 299) Parents work ethic is not so bad! The University of Sydney Then… Page 32 Marc turns around to Willem (Comber & Kamler, 2004) In the beginning “New knowledge” Then… Deficit discourses The non reader can regarding families read! when he hadn’t met the parents. Different teaching for Willem “never completing writing tasks”, “little motivation toward reading books from the provided book boxes”, “simply disinterested in set work” (p. 299) Innovative and inclusive teaching strategies for whole class (radio segment / access to TEXTEASE) The University of Sydney Parents work ethic aint so bad! Page 33 What did this mean for Willem’s learning? – “I liked fineing the snake sing and it saw yag. (February)” (p.300) – “Dery Diary, I am going to the football to nit and I going to see Richmnd and Mlbne and I hop it is fun and I am going to set rit up the top or the stad and it is fun. (21 March)” (p.300) The University of Sydney Page 34 – “At the third quarter bounce the Tigers are ahead, 10.3.63 and Collingwood are only 2.2.14. Trailing by 49 points the Magpies do not have a chance against Richmond. Darren Gaspar taps the ball down to Campbell. Wyane Campbell, 4 times best and fairest, handballs to Rodan. David Rodan runs on as Brad Ottens shepherds Nathan Buckley. The 2002 AFL rising star, Rodan boots one long from 60 metres out. The pack comes together right in front of goals. Richardson sticks his boot into Cloak’s back. He launches in the air and takes a mark! The crowd goes wild as superstar Mark Richardson lines up for his sixth goal. The scoreboard will now be 11.3.69. Richmond is killing Collingwood! (End of May)” (p.300-301) The University of Sydney Page 35 Let’s think about our eggplants, ‘subject positions’ (positionality) and Marc and Willem – Blame students and/or families for their ‘lack’ = deficit discourse = Teacher positioned as helpless. – Recognise reading ability and family strengths (virtual school bags) = nondeficit discourses = Teacher positioned as researcher (assessment), teacher positioned as designer (new coursework), teacher positioned as supporter (improvement in Willem’s work) – Willem was always and always will be Willem. Only Marc’s knowledge of Willem changed, as did his capacity and strategies for negotiating and arbiting curricululm for his students. The University of Sydney Page 36 Marc’s is a story of hope (connecting with previous reading) – Marc held multiple knowledges of Willem, each to different effect on teaching and learning. – “as soon as we admit pluralism, we are forced to admit that ours is not the only standpoint, the only experience, the only way, and the truths we have built our lives on begin to feel fragile.” (Palmer, 2009, p.63). WK7 – Teachers work is, in part, discursive (Comber, 2006). WK6 – “The point to remember is that if we have been made, then we can be ‘unmade’ and ‘made over’” (McLaren, 2009, p.80). WK2 &3 The University of Sydney Page 37 Key messages The University of Sydney – What you know impacts what you say and do. (Discourses do stuff!) – Each discourse places you in a particular relationship to the learner you know (‘subject position’ or positionality). – The change from ‘non-reader Willem’ to ‘successful writer Willem’ was Marc’s knowledge and related teaching decisions (“getting out of deficit” discursive work) – Positionality impacts your decisions of what and how to teach. Page 38 Pulling it all together – that which robots could never do J Teachers are arbiters and navigators of curriculum. Arbitration and navigation is dependent on the discursive work and positionality of teachers. This discursive work includes interpreting and curating curriculum knowledges and “matching” these to the perceived learning needs of students. The University of Sydney Page 39 Reflect: In what way might teachers be considered arbiters of curriculum? ARBITER (noun): 1. gen. One whose opinion or decision is authoritative in a matter of debate; a judge. (Think about the two teachers’ different but finite presentations of the food design and technology outcome to their students) 2. spec. One who is chosen by the two parties in a dispute to arrange or decide the difference between them; an arbitrator, an umpire. (Think about the basketball coach who is reconciling specific team’s learning needs by curating expert knowledges) 3. One who has power to decide or ordain according to his own absolute pleasure; one who has a matter under his sole control. (Think about the power dynamics inherent in Marc’s two different understandings of Willem) The University of Sydney (Oxford Online Dictionary, 2018a) Page 40 Reflect: In what way might teachers be considered navigators of curriculum? NAVIGATOR, n. 1. A person who navigates. a. A person who directs the course of a motor vehicle; a person who map-reads for, or gives directions to, the driver of a motor vehicle (Think about Marc’s approach to book boxes before and after the home visit to Willem) (Oxford Online Dictionary, 2018b) – The University of Sydney Page 41 References – – – – – – – – – – – Comber, B. (2006). Pedagogy as work: Educating the next generation of literacy teachers. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 1(1): 59-67. Comber, B., & Kamler, B. (2004). Getting out of deficit: Pedagogies of reconnection. Teaching Education, 15(3), pp. 293-310. Foucault, M. (1972). The Archaeology of Knowledge (A. M. S. Smith, Trans.). London: Routledge. Gale, T., Mills, C., & Cross, P. (2017). Socially Inclusive Teaching: Belief, design, action as pedagogic work. Journal of Teacher Education, 68(3), pp. 345-356. Gutting, G. (2003). Introduction. Michel Foucault: A user's guide. In G. Gutting (Ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Foucault (2nd ed., pp. 1-28). New York: Cambridge University Press. (Reprinted from: 2006). Kendall, G., & Wickham, G. (1999). Using Foucault's Methods. London: Sage Publications McLaren, P. (2009). Critical pedagogy: A look at the major concepts. In A. Darder, M.P. Baltodano & R.D. Torres (Eds), The Critical Pedagogy Reader. New York and London: Routledge. McMahon, S., Harwood, V. (2016). Confusions and conundrums during final practicum: A study of preservice teachers' knowledge of challenging behaviour. In E. Bendix Petersen & Z. Millei (Eds.), Interrupting the PsyDisciplines in Education, (pp. 145-166). London: Palgrave Macmillan. Palmer, P. J. (2007). The courage to teach: Exploring the inner landscape of a teacher's life (Chapter 2). San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass. Oxford Online Dictionary. (2018a). Arbiter, n. Available at: http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/10167 Oxford Online Dictionary. (2018b). Navigator, n. Available at: http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/125478 The University of Sydney Page 42 Images – – – – – – – – – – Eggplant (botanic drawing): https://theoddpantry.com/2015/03/13/a-thousand-names-for-eggplant/ Eggplant (harvest on truck) : http://www.producebites.net/five-fun-facts-about-eggplants/ Australian Guide to Healthy Eating: https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/guidelines/australian-guide-healthyeating Graphic for ‘economics’: http://www.reuun.com/download-wp/402774133.html Cartoon chef: http://www.cestboncooking.ca Trevor Gale, https://www.gla.ac.uk/schools/education/staff/trevorgale/ Carmen Mills, https://researchers.uq.edu.au/researcher/1374 Russell Cross, http://education.unimelb.edu.au/llrh/experts Barbara Comber, http://www.unisa.edu.au/Education-Arts-and-Social-Sciences/school-ofeducation/Archive/education/Our-research/Our-people/ Basketball on court, https://www.capitalfm.co.ke/lifestyle/2017/06/05/east-africa-city-slam-basketballtournament-comes-nairobi-kenya-mombasa/ The University of Sydney Page 43