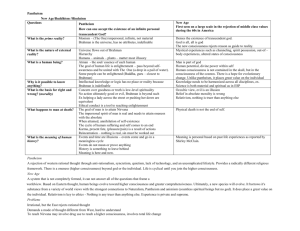

A N IN TRODUCTION TO IN DI A N PHILOSOPH Y An Introduction to Indian Philosophy offers a profound yet accessible survey of the development of India’s philosophical tradition. Beginning with the formation of Brāhma ṇical, Jaina, Materialist, and Buddhist traditions, Bina Gupta guides the reader through the classical schools of Indian thought, culminating in a look at how these traditions inform Indian philosophy and society in modern times. Offering translations from source texts and clear explanations of philosophical terms, this text provides a rigorous overview of Indian philosophical contributions to epistemology, metaphysics, philosophy of language, and ethics. This is a must-read for anyone seeking a reliable and illuminating introduction to Indian philosophy. Key Updates in the Second Edition • • • • • • • • • Reorganized into seven parts and sixteen chapters, making it easier for instructors to assign chapters for a semester-long course. Continues to introduce systems historically but focuses on new key questions and issues within each system. Details new arguments, counter-arguments, objections, and their reformulations in the nine schools of Indian philosophy. Offers expanded discussion of how various schools of Indian philosophy are engaged with each other. Highlights key concepts and adds new grey boxes to explain selected key concepts. Includes a new section that problematizes the Western notion of “philosophy.” New Suggested Readings sections are placed at the end of each chapter, which include recommended translations, a bibliography of important works, and pertinent recent scholarship for each school. Adds a new part (Part III) that explains the diffculties involved in translating from Sanskrit to English, discusses the fundamental concepts and conceptual distinctions often used to present Indian philosophy to Western students, and reviews important features and maxims that most darśanas follow. Provides new examples of applications to illustrate more obscure concepts and principles. Bina Gupta is Curators’ Research Professor Emerita at the University of Missouri-Columbia and Affliated Faculty, South Asian Studies, University of Pennsylvania. A N INTRODUCTION TO IN DI A N PHILOSOPH Y Perspectives on Reality, Knowledge, and Freedom SECOND EDITION Bina Gupta Second edition published 2021 by Routledge 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017 and by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2021 Taylor & Francis The right of Bina Gupta to be identifed as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identifcation and explanation without intent to infringe. First edition published by Routledge (2012) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this title has been requested ISBN: 978-0-367-36308-6 (hbk) ISBN: 978-0-367-35899-0 (pbk) ISBN: 978-0-429-34521-0 (ebk) Typeset in Baskerville by codeMantra To Claudio, the light of our daughter’s life and whom Madan and I cherish as our “son,” Sonya, Dylan, Avi (my three grandchildren) who make all worthwhile, Swati (daughter) and Madan (husband) my anchors, my orbit, and for being the voices of sanity in my life CON TEN TS ix xvii Preface List of Abbreviations PA RT I 1 Introduction 1 Introduction 3 PA RT I I 25 The Foundations 2 The Beginnings of Indian Philosophy: The Vedas 27 3 The Upaniṣads 41 PA RT I I I Dar śanas: Preliminary Considerations 4 Darśanas: Preliminary Considerations 57 59 PA RT I V Non-Vedic Dar śanas 75 5 Indian Materialism: The Lok āyata/Cārvā ka Darśana and the Śrama ṇas 77 6 The Jaina Darśana 91 7 The Bauddha Darśana 106 vii CONTENTS PA RT V The Ancient Dar śanas 135 8 The M īmāṃsā Darśana 137 9 The Sāṁ khya Darśana 157 10 The Yoga Darśana 176 11 The Vaiśeṣika Darśana 191 12 The Nyāya Darśana 209 PA RT V I Systems with Global Impact 237 13 The Buddhist Schools 239 14 The Vedānta Darśana 269 PA RT V I I The Bhagavad G ītā 319 15 The Bhagavad G īt ā 321 PA RT V I I I Modern Indian Thought 345 16 Modern Indian Thought 347 PA RT I X Translations of Selected Texts 367 Appendix A: The Foundations 368 Appendix B: The Non-Vedic Systems 380 Appendix C: Ancient Systems 393 Appendix D: Systems with Global Impact 415 Glossary of Important Sanskrit Words Notes Selected Bibliography Index 427 436 462 467 viii PR EFACE This is the book I always wanted to write; however, I postponed writing it for almost four decades. One may ask: Why? In the early seventies, as a young assistant professor, I was completely taken aback by two persistent misconceptions. 1 2 I became painfully aware of the marginalization of Indian philosophy in philosophy departments at American universities, of the prevalent deepseated prejudice that Indian philosophy lacks theoretical rigor, that it is theology at its best, and, at the other end, it is motivated by practical concerns rather than being directed toward the disinterested search for a theory that characterizes Western philosophy. To make the matters worse, I was told in many ways that most good philosophers are men and that women couldn’t be good philosophers. It was triple jeopardy for me; a woman, a minority with a dark complexion, and working in an area which allegedly is not a legitimate philosophical enterprise. The issues became: How can a woman philosopher living in the United States do Indian philosophy, and how can an Indian woman do philosophy per se? I will begin with the frst misconception. I realized that if I wish to thrive in a PhD granting philosophy department in the United States, writing an Indian philosophy textbook is not a viable option. In response to the above challenge, I decided to focus on Advaita Vedānta, one of the nine schools of Indian philosophy. This entailed for me several things: First, I must re-read the original Sanskrit texts of the great Vedānta teachers, especially of Śa ṃ kara, along with the most important commentaries on them; secondly, I must use all the tools of philosophy, whether Eastern or Western, to interpret their theses and supporting arguments; and thirdly, I must interpret Vedānta in light of textual exegesis. In order to be able to enter into the traditional Vedāntic schools, I studied Sanskrit texts under traditional pandits (classical scholars) in India. Thus, I worked hard toward equipping myself with Sanskrit-based Vedānta scholarship, along with the Western phenomenological, logical, and analytical methodologies. ix P R E FAC E I translated and interpreted Sanskrit texts to bring out their logical, epistemological, and analytical bases with a philosophical and rigorously analytical approach, at times, using the Western conceptual apparatus. Provoked by the Western analytic thinking and the criticisms of Indian philosophy, I began pondering over the following questions: Could analytic thinking and logical analysis make sense of the Advaitic thesis that the “brahman alone is real, world is ‘false,’ and all individuals are identical”? Could phenomenology help make sense of the Advaitic notion of a pure, non-intentional consciousness? Can Advaita fnd room for the individual’s existential individuality and freedom of choice? Who could have predicted that these questions will preoccupy me for over four decades—that they would, so to speak, become my destiny? Thus, for over four decades, in my published works, and my class lectures, my goal had been to demonstrate that Indian philosophy is an intensely intellectual, rigorously discursive, and relentlessly critical pursuit. My efforts initially resulted in the publication of several short studies in the form of articles, essays, book chapters, and fnally, several books on different facets of Indian philosophy with a focus on Advaita Vedānta. However, after gaining the title of Curators’ Research Professor (highest award for research accomplishments from my university), I thought that the time has arrived for me to begin crafting the narrative of a textbook on Indian philosophy, and several reasons reinforced in my mind that such a work is sorely needed. So, when Routledge contacted me, I accepted the offer. Indian philosophy represents an accumulation of an enormous body of material refecting the philosophical activity of 3,000 years, but it is ignored in most PhD granting philosophy departments in the United States. Frustrated with this marginalization of Indian philosophy, many scholars, writing on Indian philosophy, using the rhetoric of modern Western analytic philosophy, began making a case for Indian philosophy as a legitimate enterprise by demonstrating parallels between Indian and Western analytic philosophy, and, an increasing number of scholars to this day are doing the same. Unfortunately, an academic philosophical world in the United States still continues to ignore non-Western philosophy and maintains that Indian philosophy is not worthy of being included in their graduate curriculum. Before proceeding further, let me note here that, I am not arguing against cross-cultural comparisons. However, I have considerable anxieties about presenting Indian philosophical thought dressed up in the garb of Western rhetoric, particularly in the rhetoric of modern Western analytic philosophy in which the distinctive logic of Indian thinking, the nature of Indian analysis of thought, the nature of disputation, and the style in which philosophy was conducted in India, is totally lost. I am simply pointing out that comparing philosophical ideas in a piecemeal fashion at times may be dangerous because though an idea in one tradition may seem to be very similar to another idea in a different tradition, that similarity may only be deceptive. So, in detaching ideas from their background and contextual contexts, one runs the risk of oversimplifcation and decontextualization. One must exercise great caution x P R E FAC E in using such an approach. It is imperative that we identify the entire setting and proceed based on the overall context. Indian philosophy must neither be viewed from a religion-theological perspective nor is there any need to unthinkingly foist upon it the structures of Western rationality. Indian philosophy must be presented in its own terms, and that is what I have done in this work. I had taught an upper-division Indian philosophy course and a graduate seminar each on Advaita Vedānta and Eastern ethics for over four decades. In my lectures, one of my goals had been to demonstrate the theoretical and the discursive nature of Indian philosophy; so, I decided to use my lecture notes as the point of departure for this book. I belong to the old school; I always handwrote my lecture notes. I hired students to type these notes, and the rough draft of the frst edition was born. The book introduces students to the style in which philosophy was conducted in India, that through the centuries there has been a remarkable development, emergence of new interpretations of the ancient texts, new ways of arguing for the old theses, and the emergence of new interpretations of the ancient texts, and, at times, a totally novel point of view. I have tried to be as faithful to the Indian tradition as was possible for me, to enable students to have an accurate and authentic understanding of the various philosophical conceptions that exist on the Indian philosophical scene. The book will help students understand the different ways in which basic philosophic issues have been considered in India and introduce them to an understanding of the Indian mind. The work primarily focuses on classical darśanas (schools) of Indian philosophy.1 The basic Sanskrit texts are presented in argument-counterarguments, objection-reply forms, and it is important that students appreciate the rhetoric that bears testimony to the vibrant Indian intellectual life. Such a mode of presentation is also needed to dispel from the minds of the Western readers certain persistent myths about Indian philosophy and to bring home to them the truth of Indian philosophy, namely, that it has been a genuinely philosophical and intellectual, highly sophisticated, rigorous discipline. I would like students to understand a particular philosophical system in its integrity, to enter into its fundamental doctrines with an open mind to grasp its philosophy as a whole, and subject each philosophical school to philosophical criticisms, frst, of an internal sort, to reveal fundamental inconsistencies between the different assumptions of the philosophy, and, secondly, an external sort which discloses the limitations of a given philosophy when judged in the context of the phases of human experience and knowledge to which it fails to do justice. Though I have introduced the darśanas in historical order, the exposition of each system focuses on certain key questions and issues. The book not only demonstrates the theoretical and the discursive nature of Indian philosophy, but also shows that there exist an amazing variety of epistemological, metaphysical, ethical, and religious conceptions in Indian philosophy. These xi P R E FAC E conceptions developed within a period roughly of 1,500 years and contain very sophisticated arguments and counter-arguments that were advanced by the defenders of each thesis and its opponents. My approach therefore may be called historical-cum-philosophical. The source material of Indian philosophy particularly demands such a combination. Regarding the content of this book, an introduction sets the stage for what is to come in the subsequent chapters. I begin with the Vedas and the Upaniṣads, the foundational texts of the tradition, where one fnds the frst philosophical questions and some decisive answers. I discuss the three n āstika and the six āstika systems. The encounter with the Buddhist critique led to the rise and the strengthening of the Vedic darśanas, each with its epistemological bases, logical theory, metaphysics, and ethics. A systematic exposition of the darśanas gradually takes precedence over the historical and we have the six āstika darśanas expounded in a manner that skips over centuries of development. All this leads to the section in which four schools of Buddhism and Vedānta become the focus of my attention, because as we stand today in the twenty-frst century; it is these two that have earned a global interest. There have been numerous attempts to interpret and reinterpret them in novel ways. This book expounds on various positions rather freely, and, in detail, while staying close to Sanskrit sources, which are relevant for contemporary students’ interests. It also adds some selected texts in lucid English translation without jeopardizing the integrity of original Sanskrit texts. Wherever necessary, I have added comments in parentheses to make translations easier to understand. It is my hope that these translations will give students some taste of the literary style and philosophical rhetoric of the source material, without being too bogged down with philosophical questions. I do realize that some of the material discussed in this book is complex, and my use of Sanskrit terms throughout the book further compounds the problem. I am assuming that students will have familiarity with such philosophical terms as “epistemology,” “metaphysics,” reality,” and “appearance.” They, however, might have no acquaintance with such Indian philosophical terms as “ātman,” “brahman,” “pram āṇas,” “dharma,” “mok ṣa,” etc. I have explained selected important technical terms in their frst occurrence, when they occur after an interval, and in explanatory grey boxes in the body of each chapter. Additionally, Part III discusses issues surrounding translations. Section I of this part introduces students to the diffculties involved in translating from Sanskrit into English. Presenting Indian philosophy in English does not amount to simply translating from one language to another; it requires the use of concepts that are familiar to Western scholars and identifcation of them in the Sanskrit philosophical discourse. Section II examines which Sanskrit terms can be translated as “reason,” “experience” “intuition,” “transcendent,” “transcendental,” etc. and, alternately, which English terms may be used for “ jñ āna,” “pram āṇas,” “anubhava,” etc. This leads to questions of conceptual meaning: Does “ jñ āna” mean “knowledge” in the Western sense of the term? Is there a concept of “reason” in Indian philosophy? Are Indian philosophies xii P R E FAC E rational structures, and if so, in what sense? In using Western concepts, are we importing into our understanding of Indian thought concepts already loaded with the history of Western religion and philosophies? Section III, prior to undertaking an in-depth discussion of the nine darśanas, identifes their important features as well as selected maxims they followed. Wherever necessary and useful, I have related Sanskrit concepts to Western concepts in terms of thematic relevance. Notwithstanding the fact that a comparison of Indian concepts with Western concepts is not intrinsically necessary to explain Indian thought in English, any translation unavoidably is an exercise in comparative philosophy. Additionally, when one uses the known to explain the unknown, familiar to explain the unfamiliar, the unknown becomes less unknown and the unfamiliar less unfamiliar, and helps students gain an understanding of the unknown. I have also incorporated materials from my published and unpublished works in this book which, in my opinion, might illuminate and help students gain insights into the Indian mind. Though I always wanted to write this book, completing the frst edition became challenging due to some unforeseen medical challenges. One of the purposes of the second edition has been to correct the mistakes of the frst edition. I have thoroughly edited the book, softened the style to make it more accessible to beginners, included fundamental postulates at the beginning of each system, explained diffcult Sanskrit terms in explanatory boxes, drawn students’ attention to recent scholarship, explained how various schools of Indian philosophy engaged with each other, and compared Indian concepts with familiar Western concepts so that they may gain insights into the Indian cultural context. I have also added study questions–which include the applicability of selected concepts and principles to real-life situations–and suggested readings at the conclusion of each chapter. Given that I have retired, and this is my last book, I will candidly share with you some of my thoughts regarding my professional journey. It has been a diffcult journey, but the journey worth taking. During this journey, what has saddened me the most is the gender bias and the double standard practiced in the philosophical circles in the United States. This brings me to the second misconception mentioned at the outset of this Preface.2 In a nutshell, the problem with gender bias is two-fold. First, the assumption of male superiority with its claim to objectivity or pure reason in academia and elsewhere is pervasive, and women have no recourse to discourse or a meta-narrative to combat the insidious abuses of power. Secondly, the male perspective scholarship limits not only women but philosophy as well, and, for that matter, all forms of knowledge. This suppression of women's ways of knowing has been going on for centuries and can be referred to as the “gendering of knowledge” as an exclusive realm for male cultural domination. If one controls knowledge one controls everything. This is not the place to detail these biases. However, it would be unworthy of me if I did not note that these biases dictate every phase of evaluation in academia: Tenure, promotion, review of fellowship proposals and manuscripts, xiii P R E FAC E etc., and impact women adversely. Some women accede, others withdraw, still others change careers, and leave academia altogether. I had no choice but to confront these male biases. To accede, to give up, was not in my DNA. Let me elaborate. My father, a very religious man, often discussed with his children the basic Advaita thesis that all human beings share the same universal consciousness (ātman, or soul), and that wisdom comes in seeing all beings in one’s self and seeing one’s self in all beings. Apart from the basic Advaitic beliefs, there was another point that he had indelibly stamped upon my mind; viz., women are not second-class citizens; they can do anything they set their minds to do. I had a fascination for different languages; I had already taken courses in Sanskrit and Bengali. I wanted to learn German; he encouraged me to sign up for German courses, which I did. Bear in mind, encouraging a daughter to pursue her interests was a very progressive and unusual attitude given both the time and the cultural context. I struggled hard to reconcile the Advaita doctrine of the identity of all human beings with the treatment women received in India. I was overwhelmed by these concerns and with these unresolved tensions in mind, left India for the United States. When I emigrated from India to the United States in 1970, given that I came from a very sheltered upper-middle-class family, I was totally unaware of the struggles taking place to achieve equal treatment of women and minorities. I remember watching the Billy Jean King and Bobby Riggs tennis match being referred to as the “battle of the sexes” by American television. The expression, “Battle of the Sexes,” was being fashed on the TV screen repeatedly…and I found myself asking, “What the heck is this battle of the sexes?” I was about to fnd out. A series of experiences, to use the words of a famous philosopher, “aroused me from my dogmatic slumber,” and I soon discovered that as a woman working in a male-dominated feld of academia—in which the rational ability of women has historically been suspect—would not be easy. I was completely taken aback not only by the marginalization of Indian philosophy but also by prevalent attitudes toward women philosophers. When I began my philosophical writings, as an Indian, it was tempting to claim that there is nothing in Western philosophy that is not found in Indian philosophy. That might well be the case, but I knew that such a declaration only feeds one’s cultural-political interest; it does not characterize true philosophical wisdom. Though my initial intention was to focus solely on the elucidation of the logical principles and theories inherent in Indian philosophy and make them accessible to Western scholars, I soon discovered that a full expression of the complexities of Indian thought requires using the conceptual apparatus of Western philosophies i to make them intelligible to the Western audience. The study of East-West had no comparative models from which to originate discourse. I had to create a methodology based on my knowledge of two diverse cultural worldviews. This necessitated the ability to speak to one tradition from inside the other and vice versa leading me to examine issues from within each tradition to see how they might enlighten and enhance each xiv P R E FAC E other, in order to place living philosophical questions in their full context for the purpose of approaching the truth. In most of my writings, I tackled issues and questions by invoking whomever or whatever seems relevant and useful to the task in most of my published works and conference presentations. In the present work, however, my primary goal has been to present the classical darśanas (schools) in their own terms, to make students familiarize with the context in which these schools originated, grew, lived, developed, and had their being, in order to provide an authentic interpretation of Indian philosophy. I knew the task of writing an introductory book to such a vast topic as Indian philosophy would be daunting, both by virtue of its magnitude and the competence needed to carry it out. Any author venturing to write such a book must not only be conversant with the general philosophical issues, history of Indian philosophy, and the Buddhist thought but must also possess necessary linguistic skills, i.e., expertise in the Sanskrit language, a combination which is not easy to come by. It would be easy to say that it is foolish to undertake such a book. I accepted the challenge and decided to pursue the project, believing that there is no perfect textbook. No matter how hard an author may try, gaps remain. If this book entices a few students to pursue Indian philosophy and provides the impetus for further research, it would have served its purpose. Especially for a philosopher, it is tempting to remain immersed in the pleasures of abstract thinking and place less weight on many experiences that he/ she undergoes in real life. I, however, frmly believe that one’s thinking is never fulflling and harmonious until it is brought into practice; I am a practicing Advaitin insofar as I believe that all human beings are equal. Advaita goes beyond the phenomenal diversity of the world and by a sustained process of thinking reaches a conception of one reality behind diversity and rises to a level of thinking that achieves global relevance independently of all cultural variations. The term “globalization,” in my understanding, implies a process aiming at creating one world; it is not to be misconstrued as a process of bringing more developed countries of the West into our backyard. The goal of human existence according to Advaita Vedānta is to recover the original non-difference of all things, the oneness of all human beings, the perfection that is implicitly there in the fnite individual. None is favored. Since diversity is transcended, it is opposed to none but is the ground of all. The question is: Can Advaita Vedānta serve as a metaphysics undergirding “globalization”? I will let my readers answer this question. My own path is thinking, and I do not wish to abandon it. For me it is not a choice between “rejuvenating” the traditional philosophical ideas and embracing the analytical and/or phenomenological traditions of the West; there need not be either the wholesale acceptance or a total rejection of the past. Rather we must reappraise the traditional to see what is viable in it. Creativity thrives in an atmosphere of freedom and openness. Conversely, dogmatic adherence to any tradition, whether indigenous or foreign, amounts to philosophic suicide. In my works, one fnds neither a simple textual exegesis nor a freelance analysis. I stay clear of the two extremes. I am guided by the xv P R E FAC E conviction that no matter which tradition I am engaged in, I am above all a philosopher! Phenomenology allows access to the structure of consciousness regarded as transcendental. Existentialism reveals a human being’s place in the world. Analytic philosophy shows how philosophical arguments and conceptual rigor work. I believe Indian philosophy incorporates all three of these approaches; my very existence and my sense of purpose as a philosopher is tied to showing how this is so, and why it matters. In closing, I would like to thank my daughter, Swati, and, my husband, Madan, for believing in me. I really do not know where I would be without their constant guidance and support. Bina Gupta, Phoenixville, PA January 2021 xvi A BBR EV I ATIONS AV BG BGBh BS BSBh BU Cit CPR CU Dasgupta’s History Digha Nik āya Disinterested Witness KUBh MAU MMK MS MU NS NSBh NVT PDS Perceiving PPD Reason and Experience RV SB SD SDS Atharva Veda Bhagavad G īt ā Bhagavad G īt ābh āṣya Brahmas ūtras Brahmas ūtrabh āṣya B ṛhad āranyaka Upani ṣad Bina Gupta, Cit (Consciousness) Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, (tr.) Norman Kemp Smith Ch āndog ya Upani ṣad S. N. Dasgupta, History of Indian Philosophy, 5 Vols. Dialogues of the Buddha, (tr.) W. Rhys Davids Bina Gupta, Disinterested Witness: A Phenomenological Analysis Kena Upani ṣadbh āṣya Māṇḍukya Upani ṣad Mūlamadhyamakak ārik ā M īm āṃsās ūtras Mu ṇḍaka Upani ṣad Nyāyas ūtras Nyāyabh āṣya of Vātsyāyana Nyāyavārttika, Udyotakara on Nyāyabh āṣya Praśastapāda’s Pad ārthadharmasaṅgraha Bina Gupta, Perceiving in Advaita Ved ānta: An Epistemological Analysis The Pañcapādik ā of Padmapāda, (tr.) D. Venkataramiah, 1948 Bina Gupta, Reason and Experience in Indian Philosophy Ṛ g Veda Śatpatha Brāhma ṇa Śāstrad īpik ā Madhva, Sarvadarśanasa ṁgraha, (tr.) E. B. Cowell and A. E. Gouch xvii A BBR EV I AT IONS SK SLV Sourcebook Studies in Philosophy Śvet ā TS TSDNB TU TUBh Ved ānta S āra VP VS S āṁkhyak ārik ā Ślokavārtika A Sourcebook in Indian Philosophy, (eds.) Radhakrishnan and Moore Studies in Philosophy, (ed.) Gopinath Bhattacharyya Śvet āśvatara Upani ṣad Tarka-Sa ṃgraha of Anna ṃbha ṭṭa with D īpīka, (tr.) Chandrodaya Bhattacharyya Tarka-Sa ṃgraha of Anna ṃbha ṭṭa with D īpīka, (tr.) Yashwant Vasudev Athalye Taittir īya Upani ṣad Taittir īya Upani ṣadbh āsya Ved ānta S āra of Sadananda, (tr.) Swami Nikhilananda, Advaita Ashrama Ved ānta Paribh āṣā, (tr.) Swāmī Mādhavānanda, Advaita Ashrama Vai śe ṣikas ūtras of Ka ṇāda xviii Part I INTRODUCTION 1 IN TRODUCTION I Philosophy, Indian and Western: Preliminary Considerations In my classes on Indian philosophy in American universities, I am often asked: what is Indian philosophy, and how is it different from Western philosophy? I fnd it diffcult to answer these questions because I am being asked not only what philosophy is but also what makes Indian philosophy “Indian.” In dealing with such general questions, one must always bear in mind that the frequently used designation “Indian philosophy” is as much a construction—concealing in its fold many internal distinctions—as is the designation “Western philosophy.” Clearly, for instance, there are fundamental differences among Western philosophical schools and traditions, such as the contemporary “analytic-continental” division among philosophers in the tradition of Russell and Wittgenstein, on the one hand, and those in the tradition of Kant and Hegel, on the other hand. Thus, the category names “Indian” and “Western” do not actually bring together any common essence among the systems of thinking they designate; rather, they indicate contingently related features of geographical origin. It seems to me that history and geography are not of much help in this search for essential features of a philosophical tradition. It is indeed anachronistic to give a geographical adjective to a mode of thinking, unless one agrees with Nietzsche’s statement that Indian philosophy has something to do with the Indian food and climate, and German Idealism with the German love of beer. There must be some way of characterizing a philosophical tradition other than identifying such contingent features as the geographical and historical milieu in which it was born; some way of identifying it by its concepts and logic, its problems, its methods, and other features that are internal to the tradition under consideration. Prior to the Colonial period, philosophers in India did not concern themselves with questions of difference between Indian and Western philosophy. Most of these philosophers wrote in Sanskrit, some in their local 3 I N T RODUCT ION languages, and never sought to distinguish what they were doing from what was being done outside the Pan-Indic culture. The task of distinguishing Indian thought from the Western modes of thinking gradually became important to Indian philosophers, especially in the Colonial period. A lmost every Indian philosopher worth the name, writing in English (because that was the only Western language in which they wrote) expressed some opinion about it, although these opinions differed considerably. It is worth noting, however, that no Western philosopher—unless he/she was also an Indologist, e.g., Paul Deussen (1845–1919), Halbfass (1940–2000), or had acquired some acquaintance with Indian thought under the guidance of an Indologist, e.g., Schopenhauer (1788–1860) and Hegel (1770–1831)— thought it necessary to delimit what is called “Western philosophy” from non-Western philosophies. It is difficult to ascertain the reason for this asymmetry; perhaps, it is a political rather than a philosophical distinction. Likewise, the Indian philosophers of the classical period, e.g., Śa ṁ kara (788–820 CE), Vā caspati (900–980), or Raghun āth Śiroma ṇ i (1477–1557) did not deem it necessary to distinguish their domain of thinking from Western or Chinese thought. However, since the question has been raised, and since philosophers like me—trained both in Western thought and traditional Indian philosophy, writing on Indian philosophy and hoping to contribute to the development of Indian thought while maintaining her continuity with the tradition— must provide a satisfactory answer. This predicament is not only mine but also characterizes such thinkers as Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (1888–1975), Bimal Matilal (1935–1991), and J. N. Mohanty (1928–present). It is incumbent on my part to concede that, though reared in Western academia, I carry in my baggage the entire tradition of Indian thought. There are two kinds of positions taken by my predecessors on the issue of how Indian philosophy is different from Western philosophy. One position, more prevalent in the generations of thinkers that ended with Radhakrishnan, may be articulated thus: despite superficial similarities, Indian and Western modes of thinking are fundamentally different; this difference may be expressed in such binary oppositions as intellectual v. intuitive, discursive or logical v. spiritual, and theoretical v. practical. This contrastive view of Indian and Western philosophy is rejected by such philosophers as Matilal and Mohanty, who tend to see affinities between the Indian and the Western modes of thinking; they argue that both traditions have developed their own logic, epistemology, and metaphysics, and so the binary oppositions listed above fail to capture the exact differences between the two traditions. These thinkers, especially Matilal, under the influence of modern Western philosophy, overemphasize the analytic nature of Indian philosophy. “Verification and rational procedure” argued Matilal “are as much part of Indian philosophical thinking as they are in Western philosophical thinking.”1 Mohanty has made a similar juxtaposition by selecting theories of consciousness in Indian philosophy and 4 I N T RODUCT ION comparing them to modern Western phenomenological theories of intentionality from Brentano, Husserl, and Sartre. I stand in continuity with the second group of Indian thinkers and am greatly infuenced by their writings. Matilal and Mohanty make a good case for bridging the distance between Indian and Western philosophies. My goal in this book, however, is not to bridge this distance, but rather to focus on Indian thought as considered on its own terms, as it has presented itself to participants in its discourse from ancient times until the beginning of the Colonial period. The question is: How was the Indian world of thinking circumscribed? If we can give an adequate representation of this world in the broadest outline, it will enable us to compare and contrast the pictures that emerge. I will attempt a total circumspection of the structure of Indian thought, in the hope that it will not only make differences between Indian and Western philosophies evident, but also recognize affnities between the two. However, in order to proceed further, it is imperative that we have some understanding of the concept of “philosophy” in Western and Indian cultural contexts. II Philosophy and Western Cultural Context Philosophy, it has been said, is its own frst problem, at least insofar as self-defnition constitutes a problem. Probably, no single locution is likely to win acceptance among all philosophers, since “philosophy” encompasses a vast array of enterprises and modes of inquiry. Perhaps the safest course is to approach the issue historically, frst noting what has been done in the name of philosophy, and then ascertaining whether there can be a defnition that is adequate to exhaust all these activities. All human activities, philosophical or otherwise, take its distinctive shape within a cultural setting and tends to bear the mark of that culture. In reviewing the concept and scope of Western philosophy, we see that it has changed considerably over the 2,500 years of its existence. The word “philosophy” comes from the Greek word philien, meaning “to love or desire” and from sophia, meaning “wisdom,” so that etymologically, philosophy means “love of wisdom.” Philosophy originally signifed any general practical concern, encompassing in its scope what are generally known today as the natural sciences. As late as the nineteenth century, physics was still called natural philosophy. Eventually, science broke away from philosophy and became an independent discipline. The separation forced philosophers to redefne the nature, goals, method, and boundaries of their own inquiry. Subsequently, in the nineteenth and the twentieth century, the scope of philosophy broadened to include conceptual treatments of topics, such as violence, sex, drugs, abortion, and suicide. Obviously, philosophy cannot be the sum-total of all these concerns. What, then, is common to all these philosophical investigations? 5 I N T RODUCT ION Branches of Philosophy Metaphysics Metaphysics is the philosophical investigation of the ultimate nature of reality. It is the branch of philosophy that studies the nature of reality, “being-as-such,” and the frst causes or principles of things, and includes such abstract concepts as causality, identity and difference, space and time, mind and matter, necessity and possibility, among others. It deals with such questions as: 1 2 3 Does the external world exist? What is the nature of the external world? Are mind and matter radically different? Does God exist? What is God’s relationship to the world? Epistemology Epistemology, derived from the Greek epist ēm ē (“knowledge”) and logos (“reason”) is the philosophical study of the nature, scope, and limits of knowledge. Much debate in epistemology focuses on how knowledge relates to such concepts as “truth,” “belief,” and “ justifcation.” It deals with such questions as: 1 2 3 What are the sources of knowledge? What is the limit and extent of knowledge? How certain are we of things we claim to know? Ethics Ethics or moral philosophy is the study of moral principles; it systematizes, defends, and attempts to establish rational grounds for good conduct. It discusses such questions as: 1 2 3 What constitutes human happiness or well-being? What makes an action right? What is the foundation of moral principles? Are moral principles universal? One tradition within speculative philosophy has always focused its attention on metaphysics. It considers that the goal of philosophy is to inquire into the nature of ultimate reality. The business of metaphysics, accordingly, is to answer 6 I N T RODUCT ION the most fundamental questions possible about the universe, such as: What is the nature, composition, function (if any), and meaning (if any) of the universe? And who are we in all of this? Examples in early Western philosophy include Plato’s theory that there is a realm of perfect Forms (Ideas) that not only exists but is more real than the world of particulars (observable things), which is not a thesis to be demonstrated empirically. Similarly, speculation about the existence of an immortal soul, of a creator God, and similar issues were all matters of serious metaphysical discussion. Until recently, a majority of philosophers believed that speculative theorizing was one of the most important tasks of a philosopher. Most philosophers today no longer believe that the role of philosophy is to “discover” the real nature of the world, but that it is rather, frst and foremost, to clarify the basic concepts and propositions in and through which philosophic inquiry proceeds. The most devastating attack on speculative theorizing came from the logical positivists, who carried their ideas to Britain and America in the late 1930s, declaring that in order for a statement to be meaningful, it must be empirically verifable. Metaphysical statements about God and soul, for example, cannot be verifed by empirical procedures: they are quite literally, “nonsense.” These positivist developments underwent considerable changes in the early part of the twentieth century in the hands of such critical philosophers as G. E. Moore, Bertrand Russell, and Ludwig Wittgenstein. These philosophers were only interested in the logical analysis of propositions, concepts, terms, etc. Their contention was that the philosophy’s primary function is to analyze statements, to identify their precise meaning, and to study the nature of concepts as such to ensure that they are used correctly and consistently. This view of philosophy as conceptual-linguistic analysis has become widespread among philosophers, especially in Great Britain and America, and is considered the sine qua non of any proper philosophical enterprise. Philosophy then, may be defned as a kind of conceptual analysis that attempts to clarify the meaning of words, ideas, and beliefs. But is philosophy merely linguistic analysis? Can we really say that when a philosopher is engaged in linguistic analysis, he or she is not concerned about reality or value, but simply with the meaning and clarifcation of terms? The answer is: “no.” One philosopher, John Wild, attempts to answer such questions. In his words: Vision offers us an accurate analogy. It may be that I cannot see except by the use of spectacles. But to take off one pair of spectacles and to study them by another pair will not enable me to gain a panoramic view, it merely gives me another object to be ftted into such 7 I N T RODUCT ION a view. To know something about the spectacles — their size, weight, refraction, etc. — will not enable me to understand vision as such, which also involves other factors. And even to know what vision is in general will not enable me to see real objects. A blind man may have such knowledge. Analytic philosophy, which surrenders objective insight to focus on the logical and linguistic tools of knowledge, is like a man who becomes so interested in the crack and spots of dust upon his glasses that he loses all interest in what he may actually see through them.2 A too-exclusive preoccupation with language may lead one to lose sight of what language is all about. Linguistic analysis is an important tool but it should not—in fact, cannot—be expected to produce any meaningful results about the nature of reality or value on its own, divorced from an analysis of the world itself. The instrument of analysis is always, necessarily insuffcient to provide the content of the analysis. A philosopher’s quest is still defned by the questions that have been reiterated throughout history—What is truth? Does God exist? What is morality? Is my life controlled by outside forces or do I have control over it? What is beauty? Are some things clearly good and right, or do values differ from time to time and place to place? Is there life after death? The attempt to answer these questions has given rise to myriad and various forms of thought. Philosophy is not only a search for meaning, but a search for truth about reality and value. Philosophy, in its search for this truth, critically and rationally explicates the meaning and justifcation of beliefs, judgments, values, and facts, as well as linguistic analysis of concepts. This defnition may appear to be unduly stipulative, even arbitrary, in fact. Nonetheless it will provide a frame of reference. It may be more fruitful to think of it as a heuristic device that will enable us to move forward, comparing and contrasting the pictures that emerge rather than as a formal completed defnition. III Philosophy and Indian Cultural Context The Indian philosophical tradition represents the accumulation of an enormous body of material refecting the philosophical activity of 2,500 years. It goes back to the large, rich Vedic corpus, the earliest and the most basic texts of Hinduism.3 The earliest extant texts of this corpus are the Vedas, known as “śruti” (from “śru,” “to hear”) as they were transmitted orally from teacher to disciple; they were not systematized as a collection until around 800–600 BCE. The Vedas do not refer to a particular book, but rather to a literary corpus extending over 2,000 years. The Indian philosophical tradition, in its rudiments, began in the hymns of the Ṛg Veda, the earliest of the four Vedas, composed most probably around 2000 BCE.4 The rootedness of Indian philosophy in the Vedas has given rise to the widespread belief—not only among educated Western intelligentsia but also 8 I N T RODUCT ION among Indian scholars—that Indian philosophy is indistinguishable from the Hindu religion. The reason for this belief is obvious: it is possible that whoever were the frst translators and interpreters of the Vedic literature saw there what they found to be a religious point of view consisting of beliefs, rituals, and practices with an eschatological concern, and concluded that, as all Indian philosophical thinking goes back to the Vedic roots, the entire Indian philosophy must be religious in its motive, inspiration, and conceptualization. However, to draw such a conclusion from the literary and philosophical evidence available is uncalled for. There are several mistakes in this argument; I will address just two at this point. 1 2 The entire attempt to impose a Western concept of “religion” over the Vedic thought is a mistake. It results from an unthinking application of the Western word “religion” or its synonym, to the Vedic context. The word “religion” being Western in origin, when applied to the Indian context, prejudges the issue. It covers up the distinctive character of the Vedic religion and results in translating, better yet mistranslating, “śruti” as “revelation,” which completely distorts the signifcance of the Vedic hymns, the Vedic deities, and the entire worldview that articulates a certain relationship between human beings, nature, and the celestial beings in poetic forms. The second mistake is the apparent assumption that the pre-philosophical origins of a philosophical tradition somehow dictate the evolved character of that tradition as it develops and matures. On this unfounded assumption, the conceptual and logical sophistication of the Indian philosophical “schools” are totally overlooked either out of prejudice, or ignorance, or both. It will become obvious, as we proceed in our investigation, that a philosophical discourse is very different from a religious discourse. Indian philosophy is rich and variegated. It is a multi-faceted tapestry and cannot be identifed with any single one of its strands. Therefore, any simplifcation is an over-simplifcation. The problem is further compounded when we realize that in the Indian tradition there is no term corresponding directly to the Western term “philosophy”; the Sanskrit term “darśana” or “seeing within” is a rough approximation, lending itself to a variety of meanings not connoted by its Western counterpart. For example, “seeing within” must not be understood in a subjectivist sense (e.g., as if I were checking in with my body or emotions to see how I feel or what I need in a given moment). It signifes a cognitive process through which we engage our intellect to understand the world. Indian philosophy is concerned not only with the searching for knowledge of reality but also with critically analyzing the data provided by perception. Another term used to describe Indian philosophy is “ānvīk ṣik ī,” or “a critical examination of the data provided by perception and scripture.”5 Inferential reasoning involves critically analyzing not only observable empirical data but also ideas—so that even the foundational texts of the Vedic tradition were subject to rigorous analysis in the event of conficting evidence. 9 I N T RODUCT ION Two Sanskrit Words Approximating the Meaning of “Philosophy” 1 “Dar śana” “Darśana,” derived from the Sanskrit root “dṛś,” means “to see” or a “way of seeing.” “Seeing” as the end result of darśana is “seeing within”—the Indian seer sees the truth and makes it a part of his understanding. 2 “Ānvīk ṣik ī” “Ānvīk ṣik ī ” is critical examination of the data provided by perception and scriptures. Such an examination encompasses sources and objects of knowledge, validity and invalidity of arguments, determination of truths, etc.6 Darśana also connotes a “standpoint” or “perspective” (cf. diṭṭhi, the Pā li word for “a point of view.”) It is in this second sense that Indians allowed the possibility of more than one darśana. There are nine darśanas (schools or viewpoints) of Indian philosophy: C ārvā ka, Jainism, Buddhism, M īmāṃsā, Sāṃ khya, Yoga, Vaiśeṣika, Nyāya, and Vedānta. Traditionally, these schools are grouped under two headings: n āstika, and āstika, which in common parlance, signify “atheist” and “theist,” respectively. The Manu states that a n āstika does not believe in the existence of life after death, the existence of “the other world,” and the Vedic doctrines.7 Eventually, these Sanskrit terms came to signify those who deny the authority of the Vedas and those who accept it respectively. Classical Darsanas (Reject and argue against the Vedic Canons) Carvaka Jainism Buddhism Darsanas Founded on Independent Grounds Samkhya Yoga Nyaya Astika Darsanas (Do not Reject the Vedic Canons) Darsanas Grounded on the Vedic Texts Vaisesika Darsana Interpreting the Ritualistic Aspect, viz. 10 Darsana Interpreting the Speculative Aspect, viz. Vedanta I N T RODUCT ION It is customary to couple the six āstika darśanas in pairs: Sāṃ khya-Yoga, Vaiśeṣika-Nyāya, Vedānta-M īmāṃsā; the former in each pair is viewed as providing a theoretical framework and the latter primarily as a method of physical and spiritual training. However, in viewing the evolution of these schools such a coupling together does not make much sense, for example, it is misleading to characterize the Nyāya school as a method of physical and spiritual training. Additionally, the six āstika darśanas are usually referred to as the six “orthodox schools” of Indian philosophy. Though I do not see any harm in using the term “schools” for darśanas, I fnd the use of the term “orthodox” misleading. Daya Krishna, in his article “Three Myths about Indian Philosophy,” discusses what he calls “the myth of the schools” as one of the three myths. He argues that the concepts of school and authority are closely connected in Indian philosophy, and that “if the authority of the Vedas or the Upaniṣads or the S ūtras is fnal, then what is presumed to be propounded in them as philosophy is also fnal. Thus, there arises the notion of a closed school of thought, fnal and fnished, once and for all.”8 On Daya Krishna’s understanding of Indian philosophy—because there is no possibility of innovation in a school of thought, due to its inextricable relationship to authority—we must deny the concept of “schools.” He argues that there is “no such thing as fnal, frozen positions which the term ‘school,’ in the context of Indian philosophy usually connote.”9 He further adds that in the context of Indian darśanas, no distinction “is ever drawn between the thought of an individual thinker and the thought of a school. A school is, in an important sense, an abstraction.10 It does not contribute to the legitimacy of Indian philosophy; Indian darśanas are rather “styles of thought.”11 Notwithstanding the fact that Daya Krishna was trying to correct the “dead mummifed picture of Indian philosophy” and make it “contemporarily relevant,”12 it is not evident either that the concepts of “school” and “authority” are inextricably bound, nor that “school” is a mere abstraction. It is indeed true that Indian philosophy has its origin in the Vedas. It is also historically true that the Vedas contain the origins of all secular and spiritual knowledge, and as such prompted respect. However, this obligation to respect the Vedas never constrained the adventure of thinking. Out of this huge body of knowledge, there arose such conficting schools of Indian philosophy as the M ī māṃ s ā , S āṃ khya-Yoga, Ny āya-Vai śeṣika, and the Ved ā nta. Neither the six āstika dar śanas nor their basic framework is found in the Vedas. The existence of the nine dar śanas in the Indian tradition provides an eloquent testimony to the fact that paying homage to Vedic authority did not interfere with the freedom of investigation and rational examination of the data given in experience. So, contrary to Daya Krishna’s view, it hardly seems that respect for the authority of the Vedas constrained the adventure of thinking. 11 I N T RODUCT ION The above also explains why I fnd the persistent use of term “orthodox” in connection with the āstika darśanas by scholars of Indian philosophy to be problematic. “Orthodox” means “conforming to what is generally or traditionally accepted as right or true, established and approved.” Some of its synonyms are: “conservative, traditional, observant, conformist,” and so on. In common parlance, an orthodox group is one which follows age-old customs, traditions, and has stayed away from innovations. Designating the āstika darśanas as “orthodox schools” reinforces the erroneous belief that the six darśanas dogmatically accept the authority of the Vedas. The Vedic texts did open up a kind of discourse, a kind of questioning that led to the formation and development of divergent Indian philosophical darśanas. However, one should not miss the difference between the Vedic discourse—in style, intent, questions, and answers—and the widely divergent methods, concerns, and aims of the darśanas that developed subsequently. If one has not read the texts of Śa ṁ kara, Vātsyāyana, Udayana, or Kumārila, they would have no idea how distinct they are from the Vedic hymns and the Upanisadic dialogues. Thus, given the connotation of the term, it is misleading to say that the six āstika darśanas are the six “orthodox” schools of Indian philosophy. A review of the basic presuppositions of Indian philosophy will provide a framework and help us better understand the context in which the darśanas are embedded, which I will discuss next. IV Presuppositions of Indian Philosophy I will discuss three presuppositions, which are: (1) karma and rebirth, (2) mok ṣa, and (3) dharma. In the language of R. G. Collingwood, we may call them “absolute presuppositions” and the rest of the philosophy may be regarded as a rational and critical elaboration of these presuppositions.13 The resulting philosophies do not justify these presuppositions; they rather draw out their implications. Karma and Rebirth It is almost universally admitted that a common presupposition of Pan-Indic thought is encapsulated in karma and rebirth. The word karma is derived from the verbal root k ṛ, meaning “to act,” “to bring about,” “to do,” etc. Originally, karman referred to the correct performance of ritualistic activity; it was believed that if a ritual is duly performed, nobody, not even divinities, could stop the desired results. On the other hand, any mistake in the performance of rituals, say, a word mispronounced, would give rise to undesired results. Thus, a correct action was a right action and no moral value was attached to such an action. Eventually, karma acquired broader meaning and came to signify any correct action having ethical implications. Depending on the context, this could mean (a) any act, irrespective of its nature; (b) a moral act, especially 12 I N T RODUCT ION in the accepted ritualistic sense; or (c) accumulated results, the “unfructifed fruits of all actions.” Underlying all of these senses is the idea that by doing and acting, every individual creates something and subsequently, shapes his destiny. Karma Karma literally means, “action” or “deed.” It has been used in a variety of senses, to refer to • • • • • • any action, any intentional and voluntary action with moral import, a specifcally ritualistic action, a principle of justice, an unseen causal connection between the moral and ritualistic realms, and the causal law applied to the moral realm that the consequences of a person’s deeds infuence their subsequent lives Karma is based on the single principle that no cause goes without producing its effects, and there is no effect that does not have an appropriate cause. Nothing is arbitrary: some effects are visibly manifested in the immediate future (i.e., in one’s present life) while others, affecting one’s future lives, are not immediately apparent. Thus, freed from any theological understanding— that is, independent of postulating a God or a supreme being as the creator and destroyer of the world—karma posits a necessary relation between previous births, actions in this life, and future rebirths. Karma involves the belief that differences in the fortunes and misfortunes of individual lives, to the extent they are not adequately explained by known circumstances in this life, must be due to the unknown (adṛṣṭa) causes which can only be actions done in their former lives. Since many of our actions seem to go unrewarded in the present life, and many evil actions go unpunished, it seems reasonable to suppose that such consequences, if not fructifed in this life, will determine future lives. From a psychological perspective, these karmas form a person’s character, making us who we are and shaping our habits. The concepts of karma and rebirth are interlinked and together form a complex structure. The doctrine of karma forms the basis of a plethora of ethical, metaphysical, psychological, and religious Indian doctrines. Belief in karma is also shared both by the Buddhist and the Jaina thinkers despite other differences in their metaphysical and religious beliefs. It has even entered the American vocabulary and is expressed as “what goes around comes around.” Commonly stated account of karma in terms of “as you sow so shall you reap” or “as you act, so 13 I N T RODUCT ION you enjoy or suffer” are attempts to connect the underlying idea of karma to our ordinary ethical and soteriological thinking, and precisely for this reason, do not capture the underlying thought in its totality. A necessary sequence of lives, worlds (insofar as each experiencer has his/her own world), destinies, and redemptions is posited in order to eliminate all traces of contingency, arbitrariness, or good/bad luck from the underlying order. Karma denotes both (a) the law of causality and (b) the potential effcacy of an action, i.e., the force generated by an action having the potency of bearing fruit. A distinction is made between the prārabdha karmas, potential effcacy that is in the process of being actualized (“bearing fruit like the present body,”) and the an ārabdha karmas, which have not yet begun to bear fruit. A distinction is also made between karmas accumulated from past lives (sañcita) and those accumulating now (āgāmī ). Karma is an absolute presupposition of Indian philosophy. It is the axiom that causal order obtains within the world. This order is not assumed to be the result of an omnibenevolent and omnipotent God willing things to be; it is independently assumed. From this shared premise, both theistic and atheistic/ non-theistic philosophies could develop. Religious thinkers formed concepts of divinity that conformed to this principle of underlying order; others took the axiom of causal order as the frst step in building a metaphysical or psychological picture of things. Though we may understand the ideas of karma and rebirth, and, in some way wish to accept them, our understanding and acceptance never rise to the level of clarity we expect of our thoughts. In this context, Martin Heidegger’s insight—that Being as distinguished from beings can never be brought to pure presence or complete illumination, that all unconcealment goes with concealment, presence with absence, light with darkness—makes me wonder whether it is possible to achieve clarity in the case of an absolute presupposition. All our attempts to capture the ideas of karma and rebirth by employing the categories of causality, moral goodness, reward and punishment, or the logical idea of God as the dispenser of justice, are faint attempts to illuminate karma and rebirth. Such categories are drawn from and concern mundane experiences with which the thinker is familiar; karma and rebirth, however, concern past, present, and future experiences. Most Indian thinkers seek to establish karma as a logically necessary causal order. The most familiar argument is that in the absence of such an order, there would arise the twin fallacies (a) of phenomena which are not caused and (b) of phenomena which do not produce any effect. This idea of necessary causality requires, better yet, demands that every event has a cause and that every event produces an effect. The idea of causal necessity applied here is modeled after empirical and natural order. It is best exemplifed in scientifc laws and philosophically captured in Kant’s Second Analogy of Experience.14 The resulting understanding of karma and rebirth in this framework becomes that of a super-science, a science that not only allows us to comprehend the natural order and the human order, but also the order of all possible worlds, each 14 I N T RODUCT ION world corresponding to one birth. However, the order that is being posited in karma and rebirth is not a natural order, and what is called a “theory,” if it is a theory, is neither a scientifc theory nor a super-science. Many Hindu and the Buddhist enthusiasts wish to see karma and rebirth as a scientifc theory,15 although it does not share any features with a scientifc theory. Then, there are those who regard karma and rebirth as a “convenient fction.”16 To be clear, this assertion implies that the entire pan-Indian culture, both the Vedic and the Buddhist, is based upon a falsehood. Where must we position ourselves as critics in order to hold such a view of these ultimate presuppositions? As thinkers, we have no ground to stand upon from which we can pass such a judgment. A plausible philosophical move would be to say that karma and rebirth encapsulate Indic peoples’ understanding of a transcendental ground of the human life and the world. It is not an empirical or scientifc theory; it belongs to a different order, neither natural nor supernatural (the supernatural being understood as another natural). The transcendental, usually construed as the domain of subjectivity, selectively isolates an area of human experience and grounds the totality of the empirical in it. Many thinkers have rejected this conception of ground and prefer that the ultimate ground be ontological, some principle of being. Karma and rebirth encapsulate a fundamental understanding of that ontological ground, of our relationship to the world, which cannot be adequately accounted by a metaphysics of nature or a metaphysics of subjectivity. Both the Advaitins and the Buddhists postulate beginning-less ignorance (avidyā) as the ground, arguing that this principle accounts for our inescapable experience of obscurity, darkness, and failure to completely understand this ontological ground. And yet, both the Hindus and the Buddhist philosophers have sought to throw light on this beginning-less ignorance in different ways, assuring us that though we do not quite understand it, wise individuals do, because they have a direct experience of this ontological ground. It is worth noting that in Advaita Vedānta, this beginning-less ignorance is not simply non-knowledge, i.e., not knowing; it is also a positive entity, the source of all creativity, indeed, of the entire mundane world. In Indian thought, (1) the truth of karma and rebirth, no matter how shielded from us, may be realized; and (2) however inviolable it may be (such that even Gods cannot escape it), the hold of karma and rebirth can be broken by human beings through the realization of mok ṣa. Mok ṣa Mok ṣa is the next absolute presupposition, held by every school with the exception of the Cārvāka school. It functions not as a determining ground but as the telos beckoning humans to escape the ontological ground of karma and to come home to their transcendental essence. Mok ṣa, derived from the Sanskrit root muc, means “to release” or “to free.” Accordingly, it signifes “freedom,” “release,” 15 I N T RODUCT ION i.e., freedom from bondage, freedom from contingency. Mok ṣa—notwithstanding the differences regarding its nature and the path that leads to it—means spiritual freedom, freedom from the cycles of bondage, freedom from mundane existence, and the realization of a state of bliss. It is the highest value—value in its most perfect form—a state of excellence, the highest good, which cannot be transcended, and when attained, leaves nothing else to be desired. Mokṣa “Mok ṣa” literally, “release” or “freedom” is the most important of the four goals of life.17 In the soteriological sense, • • • it is release from the cycle of birth and death, it is freedom from karma, and it is freedom from suffering In the epistemological sense, • • • it is freedom from ignorance, it is highest knowledge, and it is a state of positive bliss From the Indian standpoint, all human beings, in fact all living beings, are of dual nature; we are, in the words of Foucault, “empirical-transcendental doublets.”18 In one respect, we are mundane being-in-the-world, and we transcend this worldly nature through a series of other grounded lives posited by the principle of karma and rebirth. In another respect, we are pure, free, nonworldly beings, inserted into a mundane context that we aspire to transcend altogether. These two transcendences are different. The frst, transcendence from one worldly life to another, through the effcacy of the unspent traces of the past events, we do not quite understand. We try to make it intelligible in various ways, using such natural categories as necessity, such moral categories as just reward and punishment, and such theological categories as divine goodness. The second, mok ṣa, is the transcendence of pure self from all mundane existence. It is a possibility that stands before us on the horizon as pure light, self-shining, and whose pure light seems to blind us, because we are accustomed to seeing things in a mingling of light and darkness. The conceptual problem really concerns how the empirical-transcendental doublet is made possible. How do I, who is essentially pure freedom, become— or appear to be—an empirical self? The origin of the empirical, its ontological ground, is not in the transcendental, but rather in the dark ground of being, viz., in the order of karma and rebirth. Thus, we have an ultimate dualism between 16 I N T RODUCT ION karma and rebirth and the transcendental, which is both my essence and serves as the telos of my empirical being. The conceptual situation in which human existence is caught may be analogous to, but is not identical with, Kant’s dualism between the unknown and the unknowable thing-in-itself. All schools of Indian philosophy, with the exception of C ārvā ka, accept mok ṣa. However, this does not mean that every school arrived at the same conception of mok ṣa; each school developed its own idea and demonstrated the possibility of mok ṣa so conceived. Anirmok ṣa (“impossibility of mok ṣa”) then becomes a material or non-formal fallacy, which, for a philosophical position, is more serious than a formal logical fallacy (hetvābh āsā), belonging to the domain of logical argumentation. Thus, we have a general conception of mok ṣa as freedom or release, but the specifc understanding of mok ṣa in each system is determined by the conceptual categories available in that system. In short, the conception of mok ṣa as freedom serves as an ultimate presupposition and the specifc understanding becomes a philosophical doctrine. Dharma So far, we have seen that there are two ultimate orders: the frst pointing backward to the order of karma and rebirth, and the second pointing forward to the possibility of mok ṣa. Human life is not truly human if it is not conscious of these two opposite directions. The third ultimate presupposition, dharma, promises to mediate between these two; it announces itself as grounded in the tradition handed over from the past and promises to help accomplish the goal sought after in the future. The term dharma, derived from the Sanskrit root dhṛ, means “to sustain,” “to support,” “to uphold,” “to nourish.” It is one of the most basic and pervasive concepts, embracing a variety of related meanings. Dharma Dharma, a very complex concept, has been used in a variety of senses. Some of these are given below. Iterations of dharma as duty include— • • • • normative duty (what one ought to do) moral imperative religious duty social responsibility Iterations of dharma as nature include— • • essential attribute or innate characteristic of a thing (“the dharma of water is to fow”) essential foundation of all things, i.e., truth 17 I N T RODUCT ION Dharma as a system of rules governs every aspect of human life, including our relationship with ourselves, to our families, to our communities, to the state, and to the cosmos. Accordingly, we have the family-dharma, the royaldharma, the dharma pertaining to various stages of an individual’s life, the caste-dharma, the ordinary dharma, etc. Besides the social differentiation of dharma, there are also dharmas that cannot be brought under the social rubric, e.g., an individual has a duty to himself (e.g., purity), to others irrespective of var ṇa (e.g., charity), to Gods (e.g., sacrifce), and nature (e.g., protecting the plants). These rules have different strengths, and hold good with differing binding force, permitting exceptions at times, and, in their totality, form a world by themselves. But how does one determine the essence of each domain? Who legislates them, if at all they are legislated? Alternately, do they fow from the essential nature of each domain as it is the dharma of water is to fow and fre to burn? It is here that philosophy can get down to work instead of simply invoking a dharma śāstra (dharma-treatise). But the work is endless, and dharmas provide a perpetual feld of philosophical research. Now, with this enormously complex notion of dharma, it is inevitable that there would be situations when the multitude of prescribed duties by which we live our lives come into confict with each other. It is such conficts that generate moral dilemmas and determine the tragedies of the Indian epics, leading to a deeper spiritual vision and the need for mok ṣa to override what seems to be the inviolable claims of dharma. The origin of dharma does not lie in the command of God, but rather in the immemorial tradition and customary usages. Dharma is the embodiment of truth in life, eternal, and uncreated, as is life itself. The relation of dharma to God is thus somewhat nebulous and constitutes a perennial issue for commentary and disputation in Hindu literature exemplifed, for instance, in the great Hindu epic, Mah ābh ārata. Dharmas also promise consequences and goals to be reached in the future. If you wish to attain such and such goal, then you should follow such and such line of actions. This hypothetical imperative, to use Kantian language, always refers to future goals to be reached. The conceptual world of dharma therefore talks about the rules of actions received from the time immemorial, and ascending orders of human existence to be reached by performing these rules. Human existence is thus caught up in the pursuit of goals in this world or in the next, giving rise to theories of morality and theological doctrines. The philosophical systems fnd here a fertile feld for conceptualization. But dharma in the long run cannot bring human beings to mok ṣa which is their constant secret aspiration. Dharma is still caught up in the order of karma and rebirth and within that order promises humans better and happier lives. Dharmas are only stepping stones, always pointing beyond themselves but never reaching a resting place; as a means of transcendence, they remain ultimately world-bound, and each world, no matter how much happier and better than the one before it, still exists within the clutches of the dark ontological ground of karma and rebirth, and contains the same distant telos of mok ṣa on 18 I N T RODUCT ION the horizon. It is this human situation which comprehends human’s pursuit of knowledge, morality, and religion, but aiming at something still higher which includes both human history as a development of the race and of the individual which take place as though a priori delimited by the ground of karma and rebirth and the goal of freedom from it. Understanding the human situation through the framework of karma and rebirth—again, considered as a super-science that provide a consistent basis for understanding orders, both observed and unobserved—also help us understand the human aims. We pursue knowledge, morality, and religious fulfllment, both individually and collectively, to forge a connection between the grounded givenness of our situation and our desire to transcend it. In between lies the space of thinking, of the philosophy of the darśanas. V Concluding Reflections The space—I described above in the last sentence as the space for thinking or philosophy—was frst opened, disclosed, and given to the people of India by what came to be known as the Vedas (śrutis). It is indeed true that the three presuppositions discussed above go back to the śrutis for their origin, but to exactly understand the nature of this origin, one must clearly understand what is meant by “opened up,” “disclosed,” or “given to the people.” Schleiermacher, the German interpreter of sacred texts, held that hermeneutics is the art of avoiding misinterpretations, and, in the case of the śrutis, misinterpretations abound.19 To say that these texts “opened up for” or “disclosed to” the people means that they gave people a new way of looking at things. The three presuppositions listed above defne a new way of looking at things. How this disclosure took place cannot be made precise by using the model of Moses receiving the Ten Commandments from God or Mohammed receiving the Qur’an from Allah. It was not a revelation in the standard Abrahamic sense of the term. The Vedic texts stand today available to us in print, pure temporality frozen into spatiality. Under such transformation, the safest way to make sense of the apauru ṣeyatva (authorlessness) of the śrutis would be to fnd a God-like author, thereby moving religion to the center of discourse. This, however, was not the origin of śrutis; the śrutis were heard, retained in memory, and transmitted from teachers to disciples. If we can capture this experience of “pure hearing” and not freeze it into a static presence of written texts, then we could perhaps have some inkling of the authorlessness of the śrutis. They are not divine revelations; they have no divine origin; God did not interrupt the course of history to reveal the Vedas. Again, referencing Kant, I would say rather that “a light broke upon all students of nature.”20 The heard texts, the words, the language, the poems, the mantras were the only access to the origins of truth. Question after question arose as to how, when, and by whom, this original truth was spoken, but no answers to these questions were given. The spirit of inquiry and interrogation 19 I N T RODUCT ION led, however, to the development of divergent paths of thought, articulated by individual teachers to their students. The spoken words became frozen into written texts, and metaphysical meanings were read into them. But the pure inner speech that was heard, the voice (which today has come under severe criticisms, e.g., by Derrida) was that of the śrutis. The śrutis thus opened up to their hearers an infinite domain of human existence to be mastered and conceptualized, systematized, and expounded in the darśanas. The three absolute presuppositions began functioning with the disclosure effected by the śrutis. It is not my purpose in this introduction to survey the philosophies of India in all their doctrinal differentiations and disputations, but to lay down and circumscribe a boundary within which the philosophical schools (darśanas) found their fields of work. Thinking did not open up its own field, but once this field was opened up by the śrutis and circumscribed by the presuppositions of karma and rebirth, mok ṣa, and dharma, philosophy could now explore the nature of human existence that these presuppositions helped to delimit and define. The C ārvā kas and the Ājīvikas, though materialists, earned their position in the spectrum of Indian philosophy by virtue of their sustained attempts to deny karma and rebirth, mok ṣa, and dharma. It is important to keep in mind that negation as well as affirmation can function equally well regarding the same presuppositions. Philosophies that do not have these presuppositions move in a different conceptual space defined by a different set of absolute presuppositions. If we forget these ultimate presuppositions and take out the locutions within different philosophical systems, Eastern and Western, the ideas might sound very much alike and may even translate into one another. However, what lies buried beneath different philosophical systems would need to be uncovered if we are not to be deceived by superficial similarities. With this in mind, let us discuss the Vedas, the foundational texts of Indian tradition. Study Questions 1. Explain briefy the following concepts: “darśana,” “ānvīk ṣik ī,” and “Vedas.” Why are these concepts important? 2. Name the three anti-Vedic schools of Indian philosophy. Why are they classifed as anti-Vedic schools? 3. Name the six Vedic schools of Indian philosophy. Why are they classifed as Vedic schools? 4. Explain the doctrine of karma. Does the doctrine appeal to you? If it does, discuss three strongest objections against the doctrine, and why those objections do not persuade you to reject the doctrine. If the doctrine does not appeal to you, discuss three strongest reasons for accepting the doctrine, and why these reasons do not persuade you to accept the doctrine. 20 I N T RODUCT ION 5. What is dharma? Explain the importance of dharma as one of the presuppositions of Indian philosophy. 6. Comment on the following passage: But dharma in the long run cannot bring human beings to mok ṣa which is their constant secret aspiration. Dharma is still caught up in the order of karma and rebirth and within that order promises humans better and happier lives. Dharmas are only stepping stones, always pointing beyond themselves but never reaching a resting place; as a means of transcendence, they remain ultimately world-bound, and each world, no matter how much happier and better than the one before it, still exists within the clutches of the dark ontological ground of karma and rebirth, and contains the same distant telos of mok ṣa on the horizon. a. b. c. What is mok ṣa? Do you think dharma is simply a means to mok ṣa? Explain the relationship between karma, dharma, and mok ṣa. 7. Defend or criticize the claim “I, who is essentially pure freedom, become— or appears to be—an empirical self.” 8. Read the following paragraphs carefully and answer the questions asked. A Sample Case: An Attorney’s Appeal Based on the Doctrine of Karma Most of us are familiar with the Dr. Larry Nassar case and his treatment of young athletes. He sexually assaulted them under the pretense of medical treatment. Nassar pleaded guilty to three counts of criminal sexual conduct: There were two counts of frst-degree involving girls between the ages of thirteen and ffteen, and one count of third-degree assault against a girl younger than thirteen. He had already pleaded guilty to child porn possession in July 2017 and was sentenced to sixty years in federal prison for child pornography. In November 2017, he pleaded guilty to sexual assault charges (CNN). However, for the sake of this discussion, let us assume that he pleaded Not Guilty, and his attorney made the case as follows: Nassar is not responsible for sexually assaulting young athletes, because his present actions were completely conditioned and determined by his previous karmas. Moral responsibility presupposes the freedom of the will; Larry was not free to choose. Therefore, he is not responsible for his actions. A person is born with certain “sa ṃsk āras” (subliminal and latent tendencies) and “vāsan ās” (desires). The confguration of the nature and proportion of these tendencies and desires are determined by his previous karmas. These tendencies and desires played an adverse 21 I N T RODUCT ION role in the formation of Nassar’s habits, self-perception, and his interactions with others in society. The low sense of self, bad habits, desires, and latent tendencies caused him to perform these horrifc actions. Bad habits are hard to change. So, he is not to be blamed for his actions. Finally, according to the karma theory, he is not going to attain mok ṣa in this life. He will go through the repeated rounds of birth and death. The region, appearance, structure, and the form of his future births will be determined by the quality of the actions performed in this life. Given his present actions, he may be born as an insect, an ant, or a cockroach in his future births. Could there be a greater punishment than that? So, why to punish him now? Please set him free. Evaluate the attorney’s arguments. If there are weaknesses, explain exactly what they are. If you fnd the argument to be a good one, think about potential challenges to each component of those arguments. Here are some questions you might wish to consider in formulating your response: • • • • • Is it accurate to say that, according to the doctrine of karma, a person is “completely conditioned and determined by his previous deeds”? Is determinism consistent with freedom? Is it impossible for a person to change his nature? What do we really mean when we say we are “free”? When we say we are free, do we mean that we have unrestricted license to do whatever we wish to do? Or is it the case that freedom does not preclude self-determination, i.e., the choice of being determined by one’s own self? Suggested Readings For karma, mok ṣa, and dharma, see J. A. B. van Buitenen, “Dharma and Mok ṣa,” Philosophy East and West, Vol. 7, No. 1/2, 1957, pp. 33–47; Daniel H. Ingalls, “Dharma and Mok ṣa,” Philosophy East and West, Vol. 7, No. 1/2, 1957, pp. 41–48; Rajendra Prasad, “The Concept of Mok ṣa,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, Vol. 36, No. 4, March 1971, pp. 381–393; and A. Chakrabarti, “Is Liberation (Mok ṣa) Pleasant?” Philosophy East and West, Vol. 33, April 1983, pp. 167–182. Ronald Neufeldt’s Karma and Rebirth (Albany: SUNY, 1986) is an excellent anthology on karma from different perspectives. Readers seeking an introduction to the nine schools of Indian philosophy will fnd the following works useful: S. N. Dasgupta, A History of Indian Philosophy, 5 Vols. (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1975); S. Radhakrishnan and 22 I N T RODUCT ION C.A. Moore (ed.), A Sourcebook in Indian Philosophy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1973); S. C. Chatterjee and D. M. Datta, An Introduction to Indian Philosophy (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 2009); and M. Hiriyanna, Outlines of Indian Philosophy (Bombay: George Allen and Unwin, 1973). Advanced students may consult J. N. Mohanty, Classical Indian Philosophy (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefeld, 2000). 23 Part II THE FOUNDATIONS The Vedas The Upaniṣads 2 THE BEGIN N INGS OF IN DI A N PHILOSOPH Y The Vedas The Vedic Literature Approximate Chronology of the Vedic Texts Ṛ g Veda 1400 BCE Yajur Veda 1400–1000 BCE S āma Veda 1400–1000 BCE Atharva Veda 1200 BCE Brāhma ṇas 1000–800 BCE Āra ṇyakas 800–600 BCE Upaniṣads 600–500 BCE The Sa ṃhitas, or more precisely, the four Vedas, viz., the Ṛg Veda, the Yajur Veda, the S āma Veda, and the Atharva Veda, are in verse. The expository literature includes the Brāhma ṇas, the Āra ṇyakas, and the Upani ṣads. Each of the Veda is further subdivided into sākh ās (branches): the Brāhma ṇas, the Āra ṇyakas, and the Upani ṣads are linked to them as appendices. All the branches did not develop into a complete literature and all recensions have not survived. I Introduction The Indian philosophical tradition in its rudiments began in the Vedas, the earliest extant texts of the Hindus. The Vedas are not the name of a particular book but the name of the literature, spanning over 2,000 years, which records 27 T HE FOU N DAT IONS the religious and speculative thinking of the Hindus. These texts were collected over several centuries by several generations of poets, philosophers, and brahmins (priests). The Vedas were transmitted orally from teachers to disciples for a considerable period of time; they are called “śrutis” (from śru, “to hear”). Evidently this designation says what it means: the Vedic texts were recited, remembered, and orally transmitted from teachers to students for a long time. They were not systematized as a collection until around 800 BCE. Thus, it is not surprising that these texts vary signifcantly not only in form but also in content. Also, given that they were not written down until much later, it is diffcult to correctly assess the difference between the original form of the Vedas and what we fnd today. The Vedas, the foundational texts of the Hindus, are written in the old Sanskrit; their expressions are highly symbolic and not easily translatable. Deriving from the verbal root √vid, meaning “to know,” the Vedas etymologically mean “knowledge” (Wissenschaft) and by implication “the sources of knowledge.” The Vedic corpus may be regarded as a body of texts incorporating all knowledge, sacred as well as profane that the community at one time possessed and prized. These texts not only discuss the nature of the deities to be worshipped, the rituals to be performed to please the deities and avoid their wrath, religious hymns to be chanted in praise of deities, sacrifcial rituals to be performed, but also such mundane topics as medicine, astronomy, agriculture, social organization and practices, music, as well as such philosophical topics as the origin of the world, the source of all things, and the nature of the relationship between the world and the One principle. When one takes all these into account, one realizes it is not only Indian philosophy but also all the subsequent developments of the science are grounded in the Vedas, making it easier to understand why the Hindus consider them to have an unquestionable validity. Sanskrit Sanskrit is a language of the Vedic and Classical India. The earliest form of the language is found in the Vedic Sa ṃhitas. Pāṇ ini in the fourth century BCE in his A ṣṭādhyāyī (Book in Eight Chapters) analyzed and standardized the Sanskrit language in 4,000 succinct rules, for the preservation of the Vedas. The language receives its name from this refnement “sa ṃsk ṛta,” meaning “perfected” or “refned.” The tradition distinguishes śruti (what is heard) from sm ṛti (what is remembered). The Vedas are taken to be self-authenticating and in case of confict between śruti and sm ṛti, śruti prevails. The Vedas are “apauru ṣeya,” i.e., “not created by a human being”; they are eternal, authorless, without 28 THE BEGINNINGS OF INDIA N PHILOSOPHY any beginning, which should not be taken to mean that the “śrutis” were “revelations,” as many Indian and Western writers seem to think. For example, K. S. Murty, an eminent Indian scholar, titles one of his books Reason and Revelation in Indian Philosophy, and argues that the Vedic revelation gives us the kind of knowledge “which is not got through perception and inference—that the Veda is promulgated at the beginning of each worldcycle by Īśvara. This is the main type of revelation accepted by Śa ṃ kara, and accordingly the greater part of this book will be concerned with the Vedic revelation.”1 Another internationally known Indologist, W. Halbfass, in his book, India and Europe, argues that the “Vedic revelation provides the most original, most immediate documentation of religious experience.”2 Such translations hide a deep prejudice stemming from the Judaic-Christian tradition, i.e., an attempt that jeopardizes an authentic understanding not only of the Vedic worldview but also of the entire Indian discourse. Revelation The Vedas are not god’s word; at no time did god interrupt the course of history to reveal the Vedas. The sacred, even infallible, status of this literature is not due to its revealed character (as is often misleadingly attributed), but rather to the fact that they are the source of the Hindu culture and civilization, and everything, including philosophy, begins there. The Ṛg Veda is the oldest of the four Vedas. The term “Ṛg” is derived from the root √ṛc, which means “a hymn,” “to praise,” and “to shine,” and the term “veda,” a cognate of the English term “wisdom,” gives the collection its name: “the sacred wisdom consisting of the stanzas of praise.” Each verse of the hymns of the Hot ṛ (an ancient order of Aryan priests) was called a “ṛc,” or a “praise,” stanza. These hymns were probably recited by the Hot ṛ priests who invoked Vedic divinities during the detailed and complicated ritualistic sacrifces performed in those days. Given the importance of the Ṛg Veda, I will return to it shortly. The purpose of the Yajur and the S āma Veda, compiled after the Ṛg Veda, is essentially liturgic. The Yajur may be regarded as the frst manual of the Vedic rituals. It explains the duties of a priest responsible for the performance of a sacrifce, formulas to be used in a sacrifce, preparation for the utensils used, physical site and the altar where the ritual is performed, and the meaning and the purpose of the sacrifce, etc. The S āma Veda is a collection of melodies that were chanted at different sacrifces, the Ṛg Vedic stanzas set to music. 29 T HE FOU N DAT IONS In the Atharva Veda, we fnd the beginnings of Indian medicine. There are hymns addressed to different powers for the sake of alleviating diseases, death, etc. Additionally, this collection also contains many highly speculative hymns which, at times, are monotheistic and at other times, are monistic in nature. The general characterization of the four groups given above must not be over emphasized, because the themes of different nature appear at places where one would expect them to appear, but they also appear at places where one would not expect them to appear. To each of these Vedas were assigned a number of texts grouped together as Upaniṣads, where philosophical questions in a more pointed sense arose for the frst time. Traditionally, the entire Vedic corpus has been divided into two parts: the portion concerned with actions (karma k āṇḍa) and the portion concerned with knowledge ( jñ āna k āṇḍa). Whereas the four Vedas are in verse, next body of texts, appearing as the frst appendices, are known as the Brāhma ṇas (relating to brahmins or the priests). These texts are commentaries on the rituals and are in prose. The Brāhma ṇas are professional literature through which one priest speaks to another priest. The brahmin professionals devoted their entire lives to the performance of the rites, traveled from estate to estate to compete for various positions patronized by kings. Rituals at times brought together brahmins from different regions for weeks, for a year, leading to a never-ending discussion about the nature of sacrifces, guidance regarding the sacrifce to be performed beftting the occasion, interpretations of rituals, utensils to be used, establish links between the procedures involved in sacrifce and cosmos, and equivalencies between universe and sacrifce. The purpose of sacrifce was to please deities to receive boons; it was not guilt offerings or thanks offerings which one fnds among the Hebrews. Sacrifce was a kind of divine event. Rites sustain the universe, and there is a correspondence between the microcosms and the macrocosms. In the next body of texts, i.e., the Āra ṇyakas (“forest treatises”), now appearing as the appendices to the Brāhma ṇas, discuss some of the above concerns. Whereas the Brāhma ṇas were primarily concerned with the relationship between the rite and the cosmos, the Āra ṇyakas (“forest treatises”) go a step further and discuss the role and importance of the human being involved in the sacrifce. We are reminded that the true wisdom consists not in the performance of the sacrifce, but rather in grasping the spiritual signifcance of the reality that underlies these rites, thereby pointing to a three-way parallelism between microcosms, the macrocosms, and the human person involved in the rite. Thus, in the Āra ṇyakas, thought moved from thinking about rites to thinking about the human person involved in the sacrifce and how such sacrifces help sustain the universe. In order to make students conversant with the Vedic worldview, I will frst discuss the Ṛg Vedic religion, and conclude with a discussion of Vedic cosmology. 30 THE BEGINNINGS OF INDIA N PHILOSOPHY II The Ṛg Vedic Religion Fundamental Postulates 1 2 3 4 5 6 Pluralities of deities are invoked in the Vedic hymns. Nature and human behavior are not chaos; they are governed by a basic law. Rituals play an important role in the hymns. Though the Vedic hymns invoke a plurality of deities, they cannot be said to be polytheistic in the Homeric sense of the term. In the later Ṛg-Vedic hymns, there is a tendency to move away from a series of more or less separate deities or powers of nature, toward the notion of a single principle. The universe is derived from the various parts of the Puru ṣa, the “Primeval Man.” The Vedic Deities (Devas) The Ṛg Veda contains 1,028 hymns organized in ten books. Interpretation and reconstruction of the Ṛg Veda, like the other three Vedas, is fraught with peril. In many places, a diffcult idea is expressed in a simple language; at other places, a simple idea is obscured by a very diffcult language. It is replete with half-formed myths, crude allegories, paradoxes, and tropes. These diffculties notwithstanding, the collection remains the source of the later practices and philosophies of the Hindus. Deva Deva (cognate with the Latin deus), derived from the noun div (sky), suggests a place of shining radiance. Though many devas are worshipped, they are not gods. In the Ṛg Vedic hymns a plurality of devas (the shining ones) or deities have been addressed and invoked. From a functional point of view, these deities may be grouped under three headings: (a) the deities of the natural world, e.g., Sū rya (Sun),3 Uṣas (dawn),4 Vāyu (wind),5 etc.; (b) the deities that represent the principals of human relations, e.g., Indra6 and Varu ṇa;7 and c) the deities of the ritual world, e.g., Agni (fre)8 and Soma (literally “sprinkle,” “distill,” “extract”; the Moon deity in Hindu mythology). a The Vedic deities were often personifed natural forces. Many hymns are addressed to the deities of the natural world, e.g., Sū rya (Sun), Uṣas 31 T HE FOU N DAT IONS b c (dawn), Vāyu (wind), and so on, though the degree of personifcation varies signifcantly. The Vedic seers were interested in nature, in establishing a correlation between human activities and nature. They read natural phenomena in terms of their own behavior; a food meant the river was angry, spring signifed peace and prosperity, and that the deities were pleased. They projected their own emotions upon nature. Indra is the most addressed deity in the Ṛg Veda; in fact, a quarter of the Ṛg Veda is dedicated to him. His vajra (the thunderbolt), horses, and chariots receive enough attention in the hymns. He drinks soma (the defed drink of immortality) and bestows fertility upon women, at times by sleeping with them. He is addressed at once as the war-deva and the weather-deva. However, his most famous deed is the unloosening of the water with his thunderbolt. He slew the demon Vṛ ta9 who prevented the monsoon from breaking. Vṛ ta had dammed the water inside a mountain that resulted in a massive drought and caused much human death and suffering. Indra is also represented as a benevolent power and a mediator. At times, he is referred to as an asura (demon), although most of the hymns emphasize his heroic deeds. Another deva, Varu ṇa, is most important from an ethical point of view; he oversees moral behavior. Varu ṇa is a celestial deva par excellence, a universal monarch. Guilty human beings confess to Varu ṇa. He is an enemy of falsehood and the punisher of sin. He resides in a thousand-column golden mansion and surveys the deeds of human beings. His eye is the Sun who is also his spy. The Sun sees everything and reports to Varu ṇa. In addition to the Sun, Varu ṇa has a number of other spies whose sole duty is to report on the evil doings of human beings. Varu ṇa is a just and inscrutable deva who inspires the sense of guilt and the feeling of awe. Human beings are destined to sin, and only Varu ṇa can release them of their sins. The Ṛg Vedic hymns allude to numerous complicated and detailed rituals in which the devas are invoked to attend the sacrifce. Thus, it is not surprising that there is tremendous interest in Agni and Soma, the two deities essentially associated with a variety of rituals. In fact, Agni is the second most addressed deva in the Vedic hymns. Agni is indispensable in the performance of sacrifces. He symbolizes the renewal and interconnectedness of all things and events. On the one hand, he is greater than the heaven and the earth, and on the other hand, he is a householder—he is the household fre, which even today is the center of domestic rituals. Fire serves as the medium and transforms the material gifts of the sacrifce into the spiritual substance from which the deities draw their strength and of which they can partake. In Agni, both the divine and the human world coalesce. He also acts as the mediator between the deities and human beings. The meeting point is the sacrifcial altar where Agni, as fre, consumes the oblation in the name of the deities and in so doing transmits his virtues to the human beings he represents. 32 THE BEGINNINGS OF INDIA N PHILOSOPHY Soma is the divinized plant of immortality. The juice of soma plant is ritually extracted in the famous soma sacrifce, a very important feature of many Vedic rituals. This juice—fltered in a woven sieve—is identifed with the sky and the pouring of the juice, water, and milk is identifed with all sorts of cosmic processes. In Hindu mythology, Soma10 represents the Moon deity; he rides through the sky in a chariot drawn by white horses. Many other deities have been mentioned in the Ṛg Veda: Mitrā (the deva of compacts and vows and is associated with Vṛ ta), Viṣṇu (known for his three strides that measured the universe), and Yama (the deva of death), to name only a few. Surprisingly, the deities that became important in later Hinduism, e.g., Viṣṇu and Śiva, play insignifcant roles in the Ṛg Vedic hymns. Is the Ṛg Vedic Religion Polytheistic? Given that a plurality of divinities is addressed, invoked, and placated, it may be argued that that the Vedic religion is polytheistic. For example, the Sanskrit commentary of Sāya ṇa11 takes the Vedic deities to be real gods with supernatural powers, and in the hymns these gods are praised through prayers so that they may confer material and other worldly benefts on human beings and communities. This understanding, which may be called both ritualistic and polytheistic, has not only infuenced the way in which the Sanskrit Vedic scholarship came to understand the Vedas, but has also exerted tremendous infuence on the writings of both Indian and Western scholars. A slightly modifed reading of Sāya ṇa’s interpretation is found in the chapter on Ṛg Veda in Radhakrishnan’s book on Indian Philosophy.12 Taking a developmental point of view, Radhakrishnan argues that (1) in the Vedic hymns there is a transition from a naturalistic polytheism through henotheism to a spiritualistic monism which we fnd in the Upaniṣads, and (2) from the religious attitude of prayer—meant to elicit benefts and avoid calamities—there emerges a dominantly philosophical enquiry, an inquiry into the one being, ekam sat, the brahman, subsequently identifed with the inner self or the ātman in the Upaniṣads. Ṛ g Vedic Religion may be called “polytheistic” in the standard sense of the term, i.e., the worship of or belief in many divinities.13 However, Ṛg Vedic religion is different from the Greek polytheism. A careful reading of the hymns reveals that the conceptual apparatus that goes with the Greek polytheism is not found in the Ṛg Vedic hymns. In the Homeric epics, gods are fully personalized entities having a precise function and power, and there is an organized system of gods with a clear ranking. In the Greek polytheism, many gods are hierarchically arranged in a patriarchal family with Zeus as the head. Their place in the hierarchy is determined by their relationship to Zeus; each god has a clearly defned function and symbolism. There exist goddesses of wisdom, of marriage, of sex, of beauty, of war, etc., and their power is limited insofar as they must answer to Zeus who has the power to modify the results of their actions. Gods are fully personalized entities and are divided 33 T HE FOU N DAT IONS in watertight compartments. The Vedic divinities, on the other hand, are not fully personalized entities; they are not divided in watertight compartments. In the Vedic pantheon, the organized system of devas with specifc power and rank is not found. The Ṛg Vedic hymns extol a particular divinity and even exaggerate its importance at the expense of the other deities. They glorify devas using the terms or epithets generally applicable to other devas (power, wisdom, and brilliance) and often confer upon one deva mythical traits and actions that characterize other devas. In these hymns the interconnections among deities are glorifed, and their distinctions are implicitly rejected. For example, Indra is assisted not only by the storm deva, but also by Viṣṇu in the breaking of the monsoon. Indra was the recipient of the soma sacrifce aimed at promoting rain and fertility. It was believed that the soma juice was highly intoxicating and it inspired the devas to do good deeds. Indeed, it is the copious imbibing of soma that gives Indra the power to overcome his enemies. As Indra assumes a position of greater supremacy in the pantheon, Soma becomes associated with his activities and at times praised as a mighty warrior. At other times, Varu ṇa and Indra are portrayed in opposition to each other, but on still other occasions, they complement each other. There is no counterpart of the Greek Zeus in the Vedic hymns. Philologist Max Müller argues that it is more accurate to describe the Vedic religion as “kathenotheistic” rather than polytheistic. Kathenotheism is the worship of one deity or god without excluding the possible supremacy of another deity. Kathenotheism (from the Greek kath’hena, “one by one”) refers to the worship of a succession of supreme gods, “one at a time.” It is the supremacy of one deity or god without excluding the possible supremacy of another deity.14 The God of Sunday is supreme on Sunday and the God of Monday is supreme on Monday. One deity is not supreme for a long time. One could say that it is a kind of quasi-monotheism. Sāya ṇa’s interpretation captures neither the original intent nor the spiritual signifcance of the hymns. I am adopting here the Advaitic hermeneutic perspective rather than the literal meaning that Western Indologists uphold following literal translations. Radhakrishnan’s reading is attractive insofar as it accommodates the Western ritualistic interpretation and synthesizes it with the traditional interpretation of Sāya ṇa. The Radhakrishnan reading, however, does not accurately represent the Vedic worldview. Indeed, many devas are worshipped, but devas are not gods. Deva (cognate with Latin deus), derived from the noun div (sky), suggests a place of shining radiance. To call “devas” “gods” is not appropriate. Īśvara (God), a fully personalized concept, is not found in the Vedas, and the Vedic concern with the cosmos must not be understood naturalistically, but in a sense that is prior, not posterior, to the nature–spirit divide. One must not lose sight of the fact that if it is naturalism, this naturalism is not materialism, and the spiritualism that is achieved is not cosmic, which fnds a vibrant spirit in natural forces and powers. Thus, we need to look upon the Upaniṣads not 34 THE BEGINNINGS OF INDIA N PHILOSOPHY as a movement of thought beyond the Vedic religion, but as the ancient commentaries, that provide varied interpretations of the hymns. The best account of the spiritualistic understanding of the Vedic deities is given in the third interpretation. Śr ī Aurobindo argues that given the Vedic etymologies, the Vedic deities or rather their names, at the same time, have a set of different meanings which confer on the stories of the sacrifces, at least three different meanings: the external-ritualistic, the psychological, and the spiritual.15 He argues that such names as “Agni,” “Indra,” “Varu ṇa,” “Mitra,” etc., have a host of interconnected meanings. The Vedic Sanskrit words, deriving from their verbal roots, have multivalence of meanings. To impose a universal meaning on them is to lose sight of this important multivalency. For example, the word “agni” means both the “natural element fre,” “a supernatural deity” symbolized by fre, and an “inner spiritual will” which aspires after the highest knowledge. All these meanings stem from the multivocity of the verbal root (aj meaning to “drive”) from which the word “agni” is derived. That verbal roots have multivalence of meanings cannot be denied. If we follow this line of interpretation, we can say that the Vedic thinking had not yet clearly separated thought from poetry, nature for them was still spiritual, and there was no Cartesian split between matter and mind. The Vedic rituals are social acts, rule-governed, and supposed to bring about social good. They also symbolize deep spiritual action, discipline, yoga, penance, austerity, intended to bring about transformation of the inner being. Thus, it would be a serious mistake to think that the Vedic religion was at best polytheism and at worst nature worship. The worship of devas was not simple nature worship; it was a part of a complicated system of rituals which could only be performed by priests. Initially, the goal of rituals was to satisfy and please devas; however, eventually sacrifces became more detailed, complicated, and sacrifces became an end in themselves. Perhaps, it is not an exaggeration to say that whereas the Vedic hymns express an intuitive experience and appreciation of the world, from the Upaniṣads begins a gradual emergence of the intellectual, better yet, of clear philosophical thinking. It would be more appropriate to fnd in these hymns a mode of thinking, a mode of experiencing the world that was prior to religion and philosophy unprejudiced by the subsequent distinction between nature and spirit. In the later Ṛg Vedic hymns there is a tendency away from a series of more or less separate deities toward the notion of a single principle. It is remarkable to note that these texts do not end with a defnite answer; they raise many more questions, and, at times end with such agnostic conclusion as “who knows, perhaps, no one, not even devas.”16 They move between a wonderful poetic response to nature and an inquisitive mind that asks questions without being committed to any dogmatic answer. We fnd on the one hand, frst-rate poetry and on the other hand, the beginnings of human questionings about the truth of the world around us. If, as Heidegger often remarked, original thinking is 35 T HE FOU N DAT IONS poetic and “thinking” (Denken) is also “thanking” (Danken),17 then the Vedic hymns show the emergence of that original thinking, not yet frozen into conceptual abstractions. The overall picture points to the sacredness of the manifest nature, the recognition that behind the manifest nature there is an unmanifest spiritual principle, and that the ideal life is to be in conformity to the deeper vision of the unity of all things which, at the same time, preserves a stratifed and hierarchical, orderly nature of social organization. We also fnd in these hymns indications of the beliefs in the imperishability of a soul and in the effcacy of one’s actions across death and rebirth. In short, there were several central philosophical concerns and questions that the Vedic seers were trying to come to grips with. I will discuss some of these under two headings: (1) the Conception of the True order and the Essence of Humanity, and (2) Cosmology. III Central Philosophical Concerns The Conception of the True Order and the Essence of Humanity The Vedic seers held that the universe is governed by “order,” or “way” or “truth,” called “ṛta,” an abstract principle that ensures justice and order in the universe. No term in English really captures what is meant by this concept in the Vedic context. Etymologically, “ṛta” is derived from the verbal root √ṛ, meaning to “go,” “move,” etc.; it signifes “the course of things,” that which enables the world to run smoothly. It is at once the ordered universe and the order that pervades it. It represents the law, unity, and rightness that underlie the orderliness of the universe. Ṛta enables natural events to move rhythmically: days follow nights, there is a succession of the seasons, the cycles of birth, growth, decay, and so on. Ṛta provides balance, and guides the emergence, dissolution, and the reemergence of the cosmic existence. It represents a powerful power that not only regulates the physical but also the ethical world; it sustains and unites all beings. Not only natural phenomena, but also truth and justice are subject to ṛta. Varu ṇa is the custodian of ṛta, the Vedic counterpart of the later notion of dharma. It is the moral law that regulates the conduct of human beings. When human beings observe ṛta, there is peace and order. In social affairs, ṛta is propriety and makes possible harmonious actions among human beings. In human speech, ṛta is truth. Eventually, satya as “agreement with reality” and anṛta as “negation of ṛta” became confned to truth and falsity of speech respectively, and appeared in moral contexts to represent virtue and vice respectively. In human dealings, ṛta is justice, and in worship ṛta assures correct performance of the ritual, which results in harmony between human beings and the deities, human beings and nature, and among human beings in general. To sum up: ṛta is the right course of things, the right structure of things. Going against the structure would be anṛta. The idea permeating the Ṛg Veda is that nature 36 THE BEGINNINGS OF INDIA N PHILOSOPHY in all its diversity and multiplicity is not chaos, but rather governed by a basic cosmic law. There are no hymns addressed to ṛta, though there are many references to it emphasizing the natural, i.e., the way things are, and the moral, i.e., the way they should be. Even the divinities derive their strength from ṛta, e.g., “from fervor ṛta and truth were born”;18 “ṛta is the movement of the Sun,”19 and “ṛta is also the way of Heaven and Earth”;20 “ṛta removes transgressions”;21 “ṛta is the right path for humans.”22 In other words, the natural course is the proper course; human beings should follow ṛta and avoid unṛta. The later Vedic texts raise numerous philosophically important questions: What is the essence of human beings? Who am I? What happens at death? Does anything survive after death? Given that life ceases to exist when the breath goes out, at many places, the essence of human beings is taken to be breath, or an airy substance like wind. However, most discussions focus on ātman, which means “self,” used as a refexive pronoun, like the German sich.23 The immaterial ātman exists in the human body, constitutes its essence,24 and survives death when everything is abstracted from the man. On death, the ātman leaves the body and goes to heaven, the level above the atmosphere. During the Vedic era, human beings prayed for a long earthly life. Praying for a span of one hundred years was the norm. People generally believed that the correct performance of rituals would ensure them a place in the heaven. The Vedic seers believed in the three horizontal levels (triloka): the earthly level, the atmospheric level (where the birds and god’s chariots few), and svarga (the abode of the gods and the blessed dead ones). Śatpatha Brāhma ṇa also reinforces the idea of the separation of the soul and the body; at one place, it declares that those who do not perform sacrifces are born, and at another place, assures us that the due performance of sacrifces ensures material comforts in another world and that doers of bad deeds are punished. Thus, though the discussions of the destiny of human beings are scattered, there is no doubt that the principle of ṛta, and the ideas of reward and punishment later evolved in the notions of dharma and karma, respectively, two basic presuppositions of Indian philosophy discussed in the previous chapter. It is not an exaggeration to say that a modern brahmin in his prayers three times a day utters the same Vedic verses he did 3,000 years ago. Cosmology The questions regarding the world-breath corresponding to the life-breath of the human being lead to several speculations regarding the source of the world and the process of creation. Several questions were raised: What is the source of things? What is the nature of that deeper principle which underlies manifest nature? What is the relation between the One principle and the diversity of empirical phenomena? Regarding the ultimate source of things, one fnds various speculations. The Vedic divinities could not be said to be the source of the world because 37 T HE FOU N DAT IONS they were associated with the natural world, for example, the deities of rain and wind, residing in the atmospheric level; Soma on the earthly level; and Agni on all three levels. Even the divinities that were not associated with the natural world, e.g., Indra and Varu ṇa, were taken to reside in some spatial location or the other, and so they could not be said to be the source of the world either. Thus, it is not surprising that in the later hymns we fnd a transition from the personal to the impersonal power or principle to explain the origin of things. To explain the nature of the One and its relation to the empirical world and the process of creation, I will focus on three hymns: Ṛg-Veda X.90 and 129, and the Atharva Veda XIX.53.25 In X.90, we see the frst streak of monistic thought. The universe is derived from the various parts of the Puru ṣa, the “Primeval Man.” Puru ṣa is at once the entire existence and an androgynous being. It is the sacrifcial victim and the deity of the sacrifce. In this hymn, the gods perform the sacrifce, the Puru ṣa becomes the oblation, and from the dismemberment of the Puru ṣa, all animals, the four castes, and the cosmic powers, e.g., the moon, the sun, the wind, breath, etc., are created. The hymn expresses Puru ṣa as both, immanent and transcendent; immanent because it pervades the entire existence, transcendent because it is not exhausted by the existence. The hymn in no uncertain terms declares that the Puru ṣa precedes and goes beyond the creation, which became very important for the later philosophical speculations in India. It gave rise to countless speculations and served as the paradigm for many types of rites; for example, it is recited in the rites performed after the birth of a son, in the ceremonies performed when the foundation stone of a temple is laid, etc. Puru ṣa typifes the Hindu cosmogonic divinity, e.g., Prajāpati (the lord of all creatures); it repeatedly appears in the Atharva Veda. There are various hymns addressed to the Support, on which everything rests. The notion of Support resembles the Puru ṣa of the Ṛ g-Veda.26 It should come as no surprise that the Vedic poet was intent on fnding an answer to the question “what is it that is the warp and woof of everything else?” The famous “Hymn of Creation” (X.129) articulates the Vedic seer’s attempt to go beyond “being” and “non-being,” to a primordial being, their unifying ground. The hymn opens in the time before creation, when there was nothing: neither being (existent) nor non-being (non-existent), no midspace, no trace of air or heaven; even the moon and the sun did not exist so that one could differentiate between the day and night, days and month. The One, which was enveloped by emptiness, came into being by its own fervor, desire (the primal seed of mind) arose giving rise to thought; thus, existence somehow arose out of non-existence. At this juncture, the poet realizes that he has gone too far because to claim that existence arises out of non-existence goes against the verdict of experience. Thus, after presumably describing the origin of the things, the last two verses ask whether anyone truly knows the origin of the existents. Even the deities cannot answer this question, because 38 THE BEGINNINGS OF INDIA N PHILOSOPHY they were created along with the world. So, the poet concludes that the origin of the existents is inexplicable; it is an enigma, a riddle. It is worth noting that creation in the Indian context is never creation ex nihilo; it signifes the ordering of already existing matter into intelligible form. In other words, the cosmos evolved out of its own substance. The hymn from the Atharva Veda articulates Time as the ontological reality; it is the creator, preserver, and the destroyer of the universe. The Sanskrit term “k āla,” derived from the root √kal, means “to collect,” “to count.” Time, in this hymn, collects or gathers past, present, and future. Time is compared to a perfectly trained horse upon which a jar flled with water to the brim is placed; time runs like a horse without spilling even a single drop. Everything—earth, heaven, Sun, wind, breath, etc.—originates in Time. It is not an exaggeration to say that Time is both the Prajāpati and the brahman of the Atharva Veda.27 Central Philosophical Questions 1 2 3 4 What is the nature of that deeper spiritual principle which underlies manifest nature? What is the relation between that One principle and diversity of empirical phenomena? How do human actions that involve social duties, sacred ritualistic performance, and the spiritual meditative practices affect the destiny of the individual soul? We also fnd in these hymns, indications of the belief in the imperishability of a soul, and a belief in the effcacy of one’s actions across death and rebirth. Overall, there is recognition that behind the manifest nature there is an unmanifest spiritual principle, and that the ideal life should be in conformity with the deeper vision of the unity of all things while at the same time preserving a stratifed and hierarchical nature of social organization. Also, a scattered discussion of such concepts as “reward and punishment,” “birth and rebirth,” “identity and difference,” and “spirit and nature,” is found throughout the Vedic texts. Thus, the dominant concepts that are handed to the philosophers are those of karma and rebirth, identity and difference, spirit and nature. Around the axis generated by these concepts revolves the destiny of Indian philosophy. In the later Ṛg Vedic hymns, on the other hand, there is a tendency away from a series of more or less separate deities or powers of nature, toward the notion of a single principle. These ideas fnd a fuller exposition, development, and conceptualization in the part of the Vedic corpus known as “Upaniṣads,” the concluding portion of the Vedas. 39 T HE FOU N DAT IONS Study Questions 1. What are the Vedas? 2. Discuss the śruti and the smṛti distinction. Are the Vedas revelations? Argue for or against, and give reasons for your position. 3. Identify the four Vedas. Discuss the key conceptions of these four Vedas. 4. Critically discuss the Hymn of Creation. Refect on the following: “X.129 represents one of the earliest impersonal conceptions of the world origin in Indian thought.” Defend or criticize the claim. 5. Discuss the Central Philosophical Concerns of the Vedas. 6. Is the Ṛg Vedic Religion Polytheistic? Compare and contrast Greek and Vedic polytheism. What is Kathenotheism? Is it accurate to say that the Vedic religion is kathenotheistic? Defend your position with rational arguments. 7. Summarize the key conceptions of the Ṛg-Veda X.90. Is it accurate to say: “In X.90, we see the frst streak of monistic thought in India”? Argue pro or con. 8. Explain the signifcance of the Atharva Veda XIX.53, the “Hymn of Time” (XIX.53). Is it accurate to say that the Time is both the Prajāpati and the brahman of the Atharva Veda? Argue pro or con. Suggested Readings For translations of the selected Ṛg Vedic hymns, insights into early Indian mythology, religion and culture, and fascinating discussions of the enduring themes of creation, sacrifce, death, women, the sacred plant soma, and devas, see Wendy Doniger O’Flaherty, The Rig Veda: An Anthology (Harmondsworth: Penguin Classics, 1981); Raimundo Panikkar, The Vedic Experience, Mantramañjari: An Anthology of the Vedas for Modern Man (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977); Frits Staal, Discovering the Vedas: Origins, Mantras, Rituals, Insights (New York: Penguin Books, 2008); and Franklin Edgerton, The Beginnings of Indian Philosophy (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1965). 40 3 THE UPA N IṢA DS I Introduction Anyone acquainted with the story of the unfolding of Indian philosophy is well aware that the Upaniṣads, the foundational texts, are multifaceted, versatile, and address a plethora of logical, epistemological, grammatical, linguistic, hermeneutical, psychological, physiological, and phenomenological theories. The Upaniṣads, formally part of the Vedas, set forth the nature of the ultimate reality, self, foundation of the world, rebirth, and immortality, to name only a few. They are generally taken to signify the esoteric teachings imparted orally by the gurus (teachers) to their disciples. Such teachings were not meant for common persons. The Upaniṣads categorically assert that “no one who has not taken a vow think on this.”1 Eventually, such expressions as “paramam guhyam” (the greatest secret), came to be used for the Upaniṣads.2 Thus, the Upaniṣads gradually came to signify the highest knowledge which was received from the teacher, a sort of secret instruction, which could only be imparted to those students who were qualifed to receive it. The prefx “upa” denotes “nearness”; ni means “down,” or “totality”; and sad “to sit,” “to attain,” or “to loosen.”3 Etymologically, a disciple humbly approaches the teacher, to gain the highest knowledge of the totality to break away from the bondage of the world. In this oral erudition, the guru and the pupils engaged in discussions and debates that added to the erudition which eventually became incorporated as part of the textual tradition. First, a few remarks about the texts themselves. The principal Upaniṣads were composed sometime between 600 and 300 BCE. There is no agreement about the number of the Upaniṣads. It is generally believed that there are over 200 Upaniṣads; the tradition maintains that one hundred and eight are extant. Of these, thirteen are said to be the major Upaniṣads; they are: B ṛhad āra ṇyaka (BU), Ch āndog ya (CU), Taittr īyā (TU), Kau ṣītak ī, Aitreya, Kena, Ka ṭha, Mu ṇḍaka (MU), Īśā, Śvet āśvatara (Śvet ā), Pra śna, Māṇḍukya (MAU), and Maitr ī. Of these thirteen, CU and BU are the longest. The order of the composition of the Upaniṣads and their antiquity is diffcult to ascertain; philological scholars have been trying different hypotheses and applying different methods to determine their antiquity. Scholars usually 41 T HE FOU N DAT IONS assign a relative chronology keeping in mind their literary form and language. Given that they were composed by different individuals, living at different times and in different parts of North India, their methods of presentation, and the larger cultural contexts in which these teachings were inserted, were different. Additionally, the individuals who put the Upaniṣads into the fnal written form may have incorporated their own teachings in the Upaniṣads. The Upaniṣads were frst put into written form in 1656 under the patronage of Dara Shikoh, the son of Śhāh Jahān, the Emperor of Delhi; ffty Upaniṣads were translated into Persian. In 1801–1802, Anquetil Duperron translated these texts from Persian into Latin. Schopenhauer, after studying the Upaniṣads in Latin, stated: “With the exception of the original text, it is the most proftable and sublime reading that is possible in this world; it has been the consolation of my life and will be that of my death.”4 Since then, the Upaniṣads have been translated into all the major languages of the world. The Number and Chronology of the Upaniṣads The earliest Upaniṣad are pre-Buddhist (800–600 BCE). There are over 200 Upaniṣads, the traditional number is 108. Of these, thirteen are said to be the major Upaniṣads. The Early Upaniṣads are in Prose Prose Upaniṣads B ṛhad āra ṇyaka (BU) Ch āndog ya (CU) Taittr īyā (TU) Kena Kau ṣītak ī Aitreya The Later Upaniṣads are both in Verse and Prose. Verse Upaniṣads Ka ṭha Mu ṇḍaka (MU) Īśā Śvet āśvatara (Śvet ā) Prose Upaniṣads Pra śna Maitr ī Māṇḍukya (MAU) 42 T H E U PA N I Ṣ A D S It is not easy to summarize the teachings of the Upaniṣads. These are openended texts and lend themselves to a variety of interpretations. Additionally, these texts use symbols, narratives, metaphors, and concrete images to convey their thoughts that further compound the interpretive problems. However, there is a broad theme that runs through these texts and this theme has been reiterated in many different ways using different paradigms. Each Upaniṣadic teaching stresses the coherence and fnal unity of all things. To that end, the Upaniṣads identify a single fundamental principle which underlies everything and explicates everything. Behind the spatial and temporal fux, there is a subtle partless, timeless, unchanging reality, called “brahman.” This fundamental principle is also the core of each individual and this core has been designated “ātman,” the “self,” the life-force independent of physical body. The Upaniṣads use different paradigms to explain the brahman and the ātman and their relationship.5 Etymologically the word “brahman” is derived the verbal root bṛh, meaning, “to grow,” or “the great”; thus, the word “brahman” came to mean “the greatest” and “the root of all things”; “ātman” meant “breath,” and came to signify the essence of the individual person. The central teaching of the Upaniṣads revolves around the thesis that the brahman and the ātman are identical. To the Upaniṣadic seers the ātman and the brahman signify the same reality one within and the other without. I will begin with a discussion of the brahman. II The Brahman We know that toward the end of the Ṛg Veda there was a search for the One, the abiding, the Supreme Being or principle. Many questions about the origin and the nature of the Supreme Being were raised. It was asked: Does being emerge from non-being or from the prior being? The former alternative was set aside as absurd and the latter was not quite rejected but was seen as leading to further questions about the origin of being. If one being lies at the beginning, then we need to know who or what that being is. The seers concluded that this power or principle, the unitary, undifferentiated principle of all beings that lies behind the world to make the world explicable for sure is not the God of religion. This most perfect being, the greatest, from which all things arise and into which they all return, was given a new designation, and it was called “brahman.” In the Vedic hymns the term “brahman,” refers to the power contained in the words recited as well as to the mysterious power present in the utterances of the Vedic hymns. The primary goal in the Vedas was to search for the power connecting the microcosm with the macrocosm, though the idea of the brahman as the ground of all things was not entirely absent. “The notion of the brahman as the sacred power within a priest may have contributed to an identifcation of the brahman with the inner spirit or the ātman. This transformation of a much older notion into a discursively idealized philosophical concept resembles the way the concept of ‘logos’ was transformed into ‘logic,’ ‘Vernunft,’ and ‘language.’”6 43 T HE FOU N DAT IONS Fundamental Postulates 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 The fundamental principle called “brahman” is the foundation of all existence. It is the cause of the origination, sustenance, and destruction of the world. This fundamental principle is also the core of each individual and as the core it has been called “ātman,” the “self,” the life-force, independent of physical body. Ātman is brahman; the ātman and the brahman signify the same reality, one within and the other without. The world is a moral stage where one gets what one deserves. Avidyā (ignorance) is the cause of bondage and preserves the cycle of transmigration (sa ṃsarā). There is a path that leads to realizing the brahman. Knowledge, not rites, can get one release from re-death, transmigration. Mok ṣa is the supreme goal of life. The word “brahman,” though found in the Vedas, came to prominence in the Upani ṣ ads. What is brahman?7 This fundamental question was formulated in different ways: What is the One being that underlies many beings? What is that by knowing which all else becomes known? 8 What is that by knowing which one overcomes suffering? What is that from which everything arises? 9 There is also the standard metaphysical enquiry: What was there at the beginning? What is that from which all things arise and into which they all enter after dissolution? The answer in all cases was “brahman.” The Vedic sense of power continues in the Upaniṣads: Ka ṭha Upani ṣad, for example, states that the various devas carry out their respective jobs because of the fear of the brahman;10 Kena Upani ṣad informs us that the various devas have no power outside the power of the brahman, etc.11 The brahman of the Upani ṣads, however, is much more than a power; it is the cause of the origination, sustenance, and destruction of the world.12 In the BU, when Yājñavalkya is questioned about the number of gods, he initially says that 3,306 gods were simply manifestations of thirty-three gods, but he successively reduces the number to six, three, two and a half, and fnally, to one. This god is none other than the brahman, and all other gods of the Vedas, the senses, and the mind are said to be the various powers of the brahman.13 This brahman is not only the source of everything, but also the core of each individual being called “ātman.” 44 T H E U PA N I Ṣ A D S In MU, Śaunaka (a householder), with great deal of respect and humility, asks Angirā (a wise man): what is that by knowing which all else becomes known?14 The text that immediately follows does not answer this question but rather seems to move on to other matters including the classifcation of knowledge into higher and lower15 and the order of creation (or emanation) of the world by (or from) the brahman. MU concludes with the statement: “all this is the brahman,” that “the brahman is this one world; it is the greatest.”16 It appears as if with the affrmation that the brahman is everything, it follows that to know the brahman is to know everything. But what is the nature of the brahman apart from its being everywhere and everything? Bh ṛgu asks this question to his wise father Varu ṇa.17 Varu ṇa informs his son that the brahman is that from which things are born, in which they live after being born, and into which they return upon departing.18 Bh ṛgu leaves in his quest for the real. He initially thinks that the brahman is food.19 All beings arise from food, after being born live in it, and return to it at the end. This is the frst answer. If this is so, then one should increase food. Further refections reveal to him that the brahman is neither food, nor vital breath, nor manas, nor intellectual awareness; it is bliss (ānanda).20 All beings arise out of bliss, continue to live in bliss, and return at the end into bliss. The entire Īśā Upani ṣad uses the paradigm of paradox and antinomies to explain the nature of the brahman. For example, whereas one verse describes the One, the essence of everything, as “unmoving, yet swifter than the mind,”21 the next verse articulates the brahman as “moving and not moving,” “far and near,” “inside” and “outside” this world.22 Ka ṭha reiterates that the brahman is subtler than the subtle, greater than the great, and seated at one place, it travels far; though asleep, it wanders around; it is present as bodiless in all bodies, present as eternal in all non-eternal things.23 The Śvet ā makes the same point when it asserts that the brahman is smaller than the smallest, and greater than the greatest.24 One cannot but ask how to interpret these patent self-contradictory statements? Clearly, if they are literally true, then our logic fails. It is more plausible to suggest that our ordinary categories (space, time, motion, rest, one, and many, etc.) do not apply to the brahman, since application of these categories generates contradictions. The brahman is all-encompassing, nothing is excluded from it. It is unmoving insofar as it is eternal; it is swifter than the mind because it is inconceivable. The brahman signifes the totality of things; it is both the unmanifested beyond and manifest phenomena, implying it is both the one and the many. In another dialogue, which occurs in the BU, there is a clear break from the ritualistic tradition of identifying the brahman with the self as residing in various deities. The text occurs in the course of a conversation between Bā lā ki (a brahmin) and the King of K āśī, Ajātaśatru.25 In this dialogue, Bā lā ki, a brahmin, successively argues that the brahman is the person in the sun, in the moon, in the lightening in the sky, in the air, and in the fre. The King rejects all these accounts. I presume that these answers prevailed among brahmins in the 45 T HE FOU N DAT IONS ritualistic tradition. The King then takes Bā lā ki by his hands to a person who was fast asleep, and asks: “Where does the person inside this man go when he is asleep, when he wakes up wherefrom does, he return? Where is he, what is he doing, when the person is asleep but dreaming?” The King fnally informs Bā lā ki that during sleep when the senses are restrained, the empirical person rests in the space within the heart. In dreams, the mind and the senses are not restrained and a person is able to move as he pleases, he becomes a King or a brahmin as it were, so to speak. In deep sleep, however, a person knows nothing; in this state, one rests like a youth or a King or a brahmin who has reached the maximum of bliss.26 The different centers of life are there, but their truth is the ātman, the truth of truths.27 It is quite clear from the above conversations that the Upaniṣadic seers reject attempts to identify the highest being with any one natural or naturalistically identifable entity as satisfying the description and, in so doing, set aside all objective and cosmological thinking about the brahman. The answers generally end up with the affrmation that the brahman is none other than the inner self of all beings, especially of humans, called “ātman.” Thus, a turn from the cosmological to the psychological mode is affected. However, one is still not clear about the precise nature of the innermost essence of human beings, the ātman. Let us discuss what the Upaniṣadic seers have to say about this essence. III The Ātman Many Upaniṣads analyze the states of consciousness (waking, dreaming, and dreamless sleep) to arrive at the knowledge of the ātman. Among the paradigms used, the paradigm of hierarchy, in which one moves from the grossest to the subtlest, explains the nature of the ātman clearly. The most succinct, systematic, and formal analysis of the states of consciousness occurs in MAU; however, the two earliest and signifcant precursors to the MAU’s analysis are found in BU and CU. In BU, the analysis of the states of consciousness occurs twice. Leaving aside the Ajātaśatru and Bā lā ki dialogue discussed above, there is a conversation between the Sage Yājñavalkya28 and the King Janaka, in which the King desires to know the source of illumination that makes it possible for human beings to function in this world. Yājñavalkya successively informs the King that it is the light of the Sun, of the moon, of the fre, and of the speech. The King is not satisfed with these answers and rejects them one by one. Yājñavalkya then goes on to describe the three states of consciousness: the waking, the dreaming, and the dreamless sleep. In the waking state a person moves and functions on account of external physical light, but in the dream state a person passes from dream consciousness to waking consciousness and then returns to dream consciousness like a fsh swimming from one bank of the river to another. In deep sleep, however, there are no dreams, no desires, and no pleasure; the self in this state is free from pain, does not lack anything, does not know anything; there are no desires, no dreams.29 The self sees by 46 T H E U PA N I Ṣ A D S its own light,30 and it is the ultimate seer; there is no other for the self to see. There is a perfect quietude (samprasanna), and there is nothing wanting or lacking; it is bliss. The self is its own light;31 it is self-effulgent and self-luminous.32 In this state, though the self does not see with the eyes; it is still the seer. The character of seeing is intrinsic to the self; the self can never lose this characteristic just as fre cannot lose the characteristic of burning. Indra, Virocana, and Prajāpati dialogue in the CU sheds further light on the nature of the ātman. It states that “pleasures and pain do not touch the bodiless self.”33 Indra representing the gods and Virocana representing the demons, after undergoing the necessary preparations with austerity and penance, go to Prajāpati and ask him to instruct them about the knowledge of the immortal self,34 which is free from sin, old age, death, hunger, thirst, etc., and after knowing which one is not afraid of anything. Prajāpati asks them to wear their best clothes and jewelry and look into a pool of water, which refects their adorned images. Prajāpati tells them that the true self is nothing but the self as seen in a refection: that the self is the same as the body. Virocana leaves with the mistaken notion that the ātman is the same as the body, and informs the demons accordingly. Indra, however, is not satisfed and returns to Prajāpati for further instructions. He rejects Indra’s subsequent answers that the ātman is the self as seen in the dream and the dreamless states. Finally, Prajāpati reveals to Indra the true nature of the self that, as the support of the body, it is unchangeable essence of the empirical self. It is the highest light (parama jyotiḥ), the light of lights. The above analyses of the states of consciousness found in BU and CU inform us that the self is at once beyond the three states (the waking, the dreaming, and the dreamless sleep) and also endures identically through them all. This self is experienced not in the deep sleep state but in the fourth, the transcendental state. MAU calls this state “tur īya.”35 At the outset, MAU declares that the self has four feet (or quarters). The waking state is said to be outward-directed; it is conscious of external objects.36 In this state, consciousness is tied to external objects. In the language of phenomenology, its intentionality is outward-directed. In the dreaming state, the self is inward-directed.37 There are no outer objects, but inner objects produced by inner desires and impressions are there. Intentionality is still there, but the intentional objects are inner. In the deep sleep state, however, the experiences that characterize waking and dreaming experiences disappear.38 Self in this state is pure consciousness. Since there is no individuated, object-directed consciousness, the pure consciousness in this state, is “consciousness enmassed or densely packed” (“vijñ ānaghana eva”), into which all objects and object-consciousness are dissolved. Finally, the fourth state is described as “the lord of all” (not in the sense of god), but as the truth of all, as that which underlies all others and comprehends them within it. It is called luminous because it has for its object only consciousness that is the light itself. It enjoys consciousness in itself unrelated to any objects whatsoever. It is also called the source of all, the inner controller, the beginning and the end of all objects—the real self or ātman. 47 T HE FOU N DAT IONS In refecting on the teachings of the sages discussed above, one notices differences; different sages use different starting points and emphasize different facets to explain the nature of the ātman. Whereas Yājñavalkya and Prajāpati begin with an analysis of the states of experience, Uddā laka in CU begins with sat or being. Yājñavalkya and King Janaka dialogue begins with the King’s question: “of what light is this puru ṣa?” After a series of answers, Yājñavalkya fnally informs the King: “The self is indeed his light; with the self as light, he sits, runs around, does his work and returns.”39 It is important to note that the above reply is given in response to the question “what light does a person here have?” “Light” in this context does not mean simply consciousness and its conditions in an abstract sense, but also that which helps one to sit, walk, work, and return. It is self-effulgent and eternal. In CU, when Indra and Virocana approach Prajāpati for the knowledge of the immortal self, Prajāpati employs a kind of physico-psychological method to progressively unfold the essence of ātman.40 Indra and Virocana desire to know the self that is free from sin, old age, death, hunger, thirst, etc. Finally, Prajāpati reveals to Indra the true nature of the self—the self is immortal, the body is destructible: the body is but the abode of the immortal self. The self is progressively identifed with the bodily self, the dreaming self, and self of dreamless sleep, until fnally, it is declared to be that which is not affected by the changing modes. It is that which is present in all three states. It is not Yājñavalkya’s or Ajātaśatru’s maximum bliss. There are at least two ways of construing the doctrine of the four states of consciousness. The frst three may be regarded as empirical pointers to the fourth, the transcendent. Alternately, the fourth may be regarded as what comprehends and makes possible the other three. The frst is suggested in BU and CU, and the second in MAU. Irrespective of whether one explicitly admits the fourth state, the point that is being made is as follows: in what lies beyond the three states, the self becomes non-dual; it becomes one with the brahman. Thus, it is not surprising that at many places in the Upanisads, the two terms the “brahman” and the “ātman” are used synonymously. The CU asks: “What is ātman? What is brahman?”41 When the inquiry pertains to the source of the universe, the word “ātman” is used, and in other cases, when the inquiry is regarding the true self of a human being the word “brahman” is used. For example, in the dialogue between B ā l ā ki and Ajāta śatru discussed above, the conversation begins with the brahman but ends with the ātman as the world-soul from which gods, divinities, and all beings are derived. IV The Brahman and the Ātman The Four Great Upaniṣadic sayings, viz., tat tvam asi, “you are that,”42 prajñ āna ṃ brahma, “brahma is intelligence,”43 aha ṃ brahm āsmi, “I am brahma,”44 “ayam ātm ā brahma,” and “this ātm ā is brahma,”45 have generally been regarded as expressing the quintessence of the Upaniṣads. These Sayings in different 48 T H E U PA N I Ṣ A D S ways reiterate that the brahman, the frst principle, is discovered within the ātman, or conversely, the ātman, the essence of the individual self, lies in the frst principle, the brahman, the root of all existence. Here, I will focus on only one of these four, viz., “tat tvam asi,” which contains one of the clearest discussions of the identity thesis. The dialogue occurs in CU,46 between Śvetaketu and Uddā laka. In this conversation, Uddā laka identifes the being (sat), the ground of all existence, and the source of all human beings, with the self of Śvetaketu. This identity thesis has been repeated nine times in this dialogue. To give my readers a favor of the style and content, I have translated a portion of the conversation in the Appendix A of this work. The context is as follows: Udd ā laka sends his son Śvetaketu to study with a teacher. Śvetaketu studies with the teacher for twelve years and returns home very proud of his knowledge and learning. Noticing his son’s arrogance, Udd ā laka asks his son: “Do you understand the implications of that teaching by which the unheard becomes heard, the unperceived becomes perceived, and the unknown becomes known?” Śvetaketu confesses that he does not know the answer. Using the examples of things made of clay and gold, Udd ā laka explains the identity thesis to his son: knowing a lump of clay means knowing all things made of clay, because things made of clay differ only in form, the essence is the clay; similarly, knowing a nugget of gold means knowing all things made of gold, because things made of gold differ only in form, the essence is the gold. Likewise, the self of Śvetaketu is not different from the being or the essence, the ground of the entire existence. Śvetaketu did not quite understand what his father was trying to tell him, and so he asks his father for further instruction. Udd ā laka states that in the beginning, there was only being, and that being had a desire to become many. Thus, he projected the universe out of himself, and after projecting the universe entered into every being. That being alone is the essence of all things; all beings have this essence as their support.47 Śvetaketu did not quite understand what his father was trying to teach him, so he again requests for further instruction. Udd ā laka asks Śvetaketu to bring a fruit from the nyagrodha tree and instructs him to cut it open. Śvetaketu does so and fnds seeds in the fruit; but he does not fnd anything in the seeds. The father explains to the son that the entire tree comes from the invisible essence that exists within the seeds. He says: “Believe me my child, that which is the subtle essence, this whole world has that for its self. That is the true self. You are that, Śvetaketu.”48 This being, the source of everything, is the self of Śvetaketu, which is not different from the ātman or consciousness. This pure consciousness, the being that is the ground of all existence, also underlies empirical consciousness. The thesis of the identity of the ātman and the brahman has been an infuential landmark in the history of Indian thought. Two different concepts, two different goals, two objects of inquiry are pursued, and, in the fnal analysis, are found to be the same. Perhaps, the inquiry regarding the brahman is more 49 T HE FOU N DAT IONS connected with the Vedic discourses: What is that One being which is called by different names? What is that ultimate stuff or power which is at the root of all things? The Upaniṣads pursue the Vedic question and reject such answers as that the brahman is the primal fire, water, the sun in the heaven, etc. Regarding the ātman such answers as that it is body, or the life-principle, or the manas, or the buddhi were rejected. Finally, the ātman is understood as the indwelling spirit in all things which is none other than the brahman. The different texts and teachers emphasize different aspects of this identity. Many texts in the Upani ṣads proceed step-by-step ascending from co-relation to fnal identity. Thus, to the idea of the ātman as body, there corresponds the concept of “brahman” as material nature. To the concept of the “ātman” as the life-principle within, there corresponds the concept of the “brahman” as indwelling life-principle within all beings. While there is such a correlation, irrespective of how one understands the nature of the individual self and the nature of cosmic reality, the gap between them is eventually closed, and one passes from co-relation to identity when both terms are understood in their true nature. Thus, with regard to both, the ātman and the brahman, there are varieties of discourses some affrming the fnal truth with regard to each, while others exhibiting a graded movement as in the doctrine of the fve sheaths (ko śas), which like onion skins have to be peeled off until the innermost core comes to light. MAU’s analysis takes us through the four states of the self: the waking, the dreaming, the dreamless, and the fourth that transcends all three, in which the inner nature of the self is manifested. One way to understand the identity is to read it as the identity of the subjective and the objective reality. Though the distinction between the subject and the object was not clearly formulated in the Upaniṣadic texts, the distinction between the subjective and the objective, the inner world and the outer world that one perceives was there, and one could argue that the distinction determines the two different directions in which the search moved forward, and that the identity thesis overcomes this distinction. Sat or being underlies both the subject and the object; thus, the two concepts the “brahman” and the “ātman” may be construed as laying down the two paths both leading to the same goal, which may be said to be either the ātman or the brahman or the identifcation of the two; alternately, better yet ātman-brahman, which is neither subjective nor objective, but both rolled in one. This identity thesis (we now know particularly from Frege) between two terms is signifcant, not a mere tautology; the two terms have different meanings but an identical referent. Affrmation of such an identity, I imagine, must have shaken the intellectual world of that time resulting in various systematizations that we come across within the Vedāntic systems. I might add that this metaphysical achievement predates by almost 2,000 years the philosophy of Hegel, in which reality was taken to be spirit, beyond the subject/object distinction. To sum up: the point that is being made is that the reality encompasses everything; it signifes the totality of things. It is both the unmanifested beyond 50 T H E U PA N I Ṣ A D S and the manifest phenomena thereby implying it is both one and many; it is also the self, the seer, and the thinker. Thus, it is not an exaggeration to say that each Upaniṣadic teaching stresses the coherence, the fnal unity of all things; everything is the brahman. V The Brahman and the World The Upaniṣads conceive the brahman both positively and negatively. The “Four Great Sayings” mentioned above describe the brahman in positive terms. Additional positive sentences are found in most of the Upaniṣads; for example, the brahman is that who consists of mind, whose body is life, whose form is light, whose conception is truth, whose soul is space, containing all works, desires, odors, and tastes, and encompassing the whole world, the speechless, the calm,49 I am the brahman,50 all this is the brahman,51 etc. Again, one also fnds such negative sentences as the brahman is neither gross, nor subtle, nor short, nor long, nor red, nor adhesive, without shadow, darkness, air, space, attachment, taste, smell, eyes, ears, speech, mind, light, breath, mouth, and measure, and without inside and outside.52 The negative sentences are best typifed by “neti, neti,” “not this, not this.”53 Accordingly, the brahman in the Upaniṣads is said to be both sagu ṇa (with qualities) and nirgu ṇa (without qualities). The positive sentences assert that everything, this object in front of me, the object at a distance, all is the brahman; the negative sentences in effect deny that any of these things is the brahman. Thus, the question arose regarding how to reconcile these contradictory statements if the Upaniṣads are not to be guilty of self-contradiction. One group of thinkers privilege the affrmative over the negative, but the others follow the reverse route. The former group argues that the negative sentences assert none of this by itself is the brahman, that negation presupposes a prior affrmation which is then to be denied, and this is exactly what happens. The second group holds that the affrmative sentences affrm the fnal truth, i.e., all that we see, the totality of all things, has its being within the brahman, but none separately. The frst group accords priority to the negative sentences by maintaining that the negation, the brahman is “not this,” “not this,” is the fnal truth, while the affrmations are provisional affrmations that everything is the brahman. There is no need to choose between the two; it is enough for our purposes to underscore the fact that the great commentators of Vedānta, which we will study later in the chapter on Vedānta, follow different interpretations of the same Upaniṣadic sentences. Ultimately one must choose which line of interpretation is logically stronger before deciding which interpretation is more plausible. Corresponding to the two views of the brahman as sagu ṇa and nirgu ṇa, there are two answers about the cause of the world. According to the former, the world is a real emanation of the brahman, according to the latter, the world is simply an appearance of the brahman. Śvet ā at the outset asks such questions as: Is brahman the cause of the world?54 Wherefrom have we all come, who has 51 T HE FOU N DAT IONS kept us alive, and at the end where do we go? Time, the nature of things, destiny, chance, the elements of being, and the ātman (the all-knowing, thinking self) were rejected as the cause of the world. No reason was given for rejecting these possibilities. The Śvet ā proceeds to develop a theistic conception of the brahman, with m āyā as its creative power that creates the world in accordance with karmas (dharma and adharma) of the fnite souls. The major trend of thought in the Upaniṣads, however, remains a theory of emanation, not of creation. Two metaphors that dominate are: (1) a spider spinning his web, and (2) a lump of salt dissolved in a bucket of water. Let me elaborate. Just as a spider, without requiring any other cause, spins its web from within, and also swallows it up; similarly, the world emanates out of the brahman and goes back into it.55 Uddā laka, the father, asked his son Śvetaketu to place a lump of salt in the water and return to him in the morning. When Śvetaketu came in the morning, the father asked Śvetaketu to go and get the lump of salt from the bucket of water. The son could not do so, because the salt had dissolved. The father then asked the son to throw away the water and return; the son did so. The father then informed the son, though he did not see the salt, it was there. The invisible, the fnest essence, that which constitutes the self of the entire world, and that is the truth; that is the ātman, “you are that.”56 Most Upaniṣadic seers agree that the brahman is the cause of the world and that the world is not manifested out of any external matter; it rather is a manifestation of an aspect of the brahman. Several Upaniṣads articulate the brahman as the creator, sustainer, and destroyer of the world; it is both the material and the effcient cause of the world. From the standpoint of the nirgu ṇa brahman, the world is an appearance of the brahman, and the principle of m āyā accounts for this appearance. The teachings of Yājñavalkya in BU, for example, “duality as it were,”57 means duality is not real. The world is an appearance; the sensually perceived world is due to m āyā, which, in the Upani ṣ ads, denotes the empirical world, i.e., the world characterized by space, time, cause-effect, is simply an appearance. Irrespective of whether the Upaniṣadic seers construe the brahman as cosmic or acosmic, they generally argued that empirical knowledge cannot be trusted to give us the highest knowledge, the knowledge of the brahman. The Upaniṣads make a distinction between the higher knowledge and lower knowledge. In MU, the wise man Angira told Śaunaka that those who know the brahman, say that there are two kinds of knowledge, the lower and the higher.58 The lower consists of the four Vedas, grammar, rituals, astrology, etc. Knowledge of anything that changes, and eventually perishes, is the lower knowledge. The highest knowledge (than which there is nothing higher) is the knowledge of the unchanging immutable, immortal, ātman/brahman. The highest knowledge is the knowledge of omnipresent self. Each of the lower objects could be worshipped as if it were the brahman, but only the ātman is brahman. The true object of the higher knowledge is the unseen, unperceivable, 52 T H E U PA N I Ṣ A D S omnipresent, inapprehensible to the senses, imperishable subtle brahman, who is the cause of all things.59 From him, brahm ā, name-form, hira ṇyagarbha, and food, are born.60 Scattered throughout the Upaniṣads is the idea that this brahman-ātman is the highest knowledge, the knowledge of which leaves nothing else to be known. It brings about the highest good, puts an end to all sufferings, and brings about immortality. The Upaniṣads repeatedly reiterate that the knowledge of the brahman is the highest knowledge. However, can we literally speak of the knowledge of the brahman? There are texts that strongly emphasize the ineffability and the unknowability of the brahman, e.g., “the self cannot be reached by spiritual learning, nor by intellect”;61 “one who knows does not know (it), one who does not know, knows,”62 “words return from it without reaching it,” etc.63 One could argue that the brahman is like the Kantian thing-in-itself, unknown and unknowable. Nothing could be further from the truth. The above quoted texts only suggest that our ordinary epistemic means do not yield the knowledge of the brahman, the only means to mok ṣa. “One who knows the brahman becomes the brahman.”64 Kena Upani ṣad raises what may be called a more strictly philosophical question, namely, what makes knowledge possible? Or, literally, who is spurred by whom? Because of whom?65 The eyes see it; the ears hear it, etc. The idea is that the senses including the manas and the buddhi by themselves cannot perform other appropriate functions unless they are guided by the ātman. So, in the long run, it is the ātman, which makes it possible for them to discharge their proper functions. The sense organs and other cognitive faculties perform their appointed jobs owing to the inspiration, intention, or command of something other than them. And yet, this something else, the ātman, is not seen by the eyes, expressed by words, or reached by the mind. How is it then, though in itself incapable of being known, it makes knowledge possible?66 The next verse improves upon the last formulation: this ātman is other than what is known and also other than what is unknown.67 An object is either known, or unknown, or in part known, while remaining unknown in other aspects. But the subject, the knower, is neither known nor unknown. It is not seen by the eyes, and yet because of it the eyes see; it is not comprehended by the manas (mind) while the manas is manifested by it, the speech organ cannot articulate it but the speech organ and the sounds are produced by it, are manifested by it. This precisely is the ātman or the brahman. The point that is being made is well established philosophically: the subject, the self, the ātman, is the ground of the possibility of the knowledge of objects, but in itself it is not a possible object. It is not the case then that I know the ātman-brahman; it is not the case that I do not know the ātman-brahman. A paradox no doubt, but the paradox has to be confronted in its full implications. “One for whom brahman is said to be unknown, truly knows it: one who knows it does not indeed know it”;68 it is the paradox of transcendental philosophy. The ātman manifests all objects because it is self-manifesting. 53 T HE FOU N DAT IONS The point that is being made is as follows: The brahman-ātman is not accessible through the empirical modes of knowing. Hence, the question: how is it known? This particular question has been answered in many different ways in different Upaniṣads. MU states that when the “buddhi is purifed of all faults, one becomes ft for acquiring that knowledge.”69 Being self-manifesting, brahman shows itself to the one whose heart is pure, who has practiced austerity, and has “burnt away” all his faults. The Ka ṭha introduces the metaphor of a chariot: the body is like a chariot on which the ātman rides, the buddhi or the intellect is the driver of the chariot, the manas or the mind is the rein, the sense organs are the horses and the sensory objects are what the horses travel over. The complex of self, i.e., the sense-organs and mind, is what the wise call the “enjoyer.” When the buddhi, under the infuence of an unsettled mind, becomes non-discriminating, the horses become uncontrollable. On the contrary, a settled mind, knows the path, and the charioteer, i.e., the buddhi is discriminating, the mind is controlled making it possible to reach the sacred goal.70 But all these faculties, as functioning within the body, have their effcacy only with regard to the empirical knowledge, i.e., the lower knowledge. Thus, the Ka ṭha in no uncertain terms affrms that the ātman is neither grasped by the Vedic hymns, nor by the intellect, nor by hearing the scriptures. He, whom the ātman chooses, grasps him, and the ātman manifests her own nature to him.71 This last sentence, as formulated here, suggests a theistic conception of god. But on Śa ṃ kara’s reading, true being, self-manifesting consciousness is revealed only to those who are true aspirants, those who seek to know the true self whole-heartedly. In another Upani ṣad, i.e., the I śa Upani ṣad, in which knowledge (vidyā ) and its opposite ignorance (avidyā ) are discussed, states that avidy ā leads to darkness, but vidyā leads to still greater darkness. It is by knowing vidyā as vidyā and avidyā as avidyā that one overcomes death and attains immortality. The above two verses have given rise to various interpretations. Here, it is suffce to note that many commentators take avidy ā to mean the knowledge of the plurality of things and vidyā simply the textual knowledge of the Vedas. Though most schools of Indian philosophy accept mok ṣa as the highest knowledge, they differ regarding the process that leads to it, and what in fact happens upon attaining mok ṣa. Some schools regard knowledge, others devotion, and still others a combination of the two, to be indispensable for reaching this knowledge. In some schools, upon attaining the highest knowledge, the empirical individual ( jīva) becomes identical with the supreme self; in others, he becomes a part of the supreme self, etc. On one account, mok ṣa is reached all at once; on another, it is reached step-by-step. The latter account makes moral life and religious practices preliminary and preparatory steps towards the fnal goal. These differences are contingent upon the ontological and epistemological presuppositions of each school, and we will study some of these issues in the chapters to follow. 54 T H E U PA N I Ṣ A D S Questions Arising from the Upaniṣadic Teachings These questions, not clearly answered in the Upaniṣads themselves, became central themes of the later philosophical traditions (e.g., within Vedānta). 1 2 3 4 5 What is the nature of the brahman? Is the brahman nirgu ṇa or sagu ṇa? What is the nature of the ātman? What is the relationship between the brahman and the world? How can one know the brahman? In conclusion, let me note the following: inquiry into the nature of knowing precedes that of being, although in the order of the way things are, being precedes knowing. The Upaniṣadic affrmation that the knower of the brahman becomes the brahman formulates the paradox, leaving it open for at least two interpretations. In a straightforward sense, it simply means that knowing results in the realization of being. But it lends itself to being understood the other way around as well, i.e., one, who becomes brahman, alone is the knower of the brahman. Knowledge is identity with the brahman. Study Questions 1. Briefy explain the meaning and the signifcance of the following terms: a. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Avidyā, (b) vidyā, (c) mok ṣa, (d) saccid ānanda, (e) nirgu ṇa, and (f) sagu ṇa. How are these concepts related? Identify the thirteen major Upaniṣads. Critically discuss the Indra and Virocana dialogue. Explain the paradigm of paradox. Critically analyze the states of consciousness discussed in the Upaniṣads. CU states: That which is the subtle essence, this whole world has that for its self. That is the true self. You are that, Śvetaketu. a. b. c. d. e. First, explain the context of this dialogue. Explain the meaning of “that” and “you.” Explain the meaning and the signifcance of the passage using examples from the dialogue. How does the passage relate to the overall teachings of the Upaniṣads? Use paradigms from different Upaniṣads to substantiate your thesis. Do you think the Upaniṣadic thought represents an advance over the Vedic thought? If so, why? If not, why not? Give reasons for your answer. 55 T HE FOU N DAT IONS Suggested Readings For an excellent translation of the twelve selected Upanisads with a useful Introduction and Bibliography, see Patrick Olivelle, Upani ṣads (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996). Students may also wish to consult Robert Ernest Hume, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads (Oxford: University Press, 1995, and S. Radhakrishnan, The Principal Upani ṣads (New Delhi: Harper Collins Publishers India, 1953), reprinted in 1994. For an introduction to the Upanisadic thought in terms of paradigms, see Joel Brereton, “The Upanishads,” in Approaches to the Asian Classics, edited by Wm. T. de Bary and I. Bloom (New York: Columbia University), pp. 115–135. 56 Part III DAR Ś ANAS Preliminary Considerations 4 DAR Ś A NAS Preliminary Considerations I Issues of Translation There is no doubt that introducing darśanas properly and without sacrifcing the integrity of the Sanskrit original texts upon which all good expositions must be based is a very diffcult venture. Many Indian philosophers today use Sanskrit sources, write in English, and wish to preserve the authenticity of their interpretations. However, presenting these sources in English (or any other language, for that matter) does not amount to simply translating from one language to another; it requires using concepts that are familiar to Western scholars and identifying them in the Sanskrit philosophical discourse. This is no doubt a tricky venture, strewn with possibilities for selfdeception and incorrect interpretations. First, any translation—whether it is of an ancient or a modern text—takes place from the vantage point of the historical present in which the translator is situated. In translating a text, the idea of capturing the original intellectual milieu is simply a romantic aspiration that is unattainable in practice. Translating a text with an effort to make it ancient implies using one’s own preconception of what was the case, which is no more or no less of a construction than the person who translates an ancient text with the preconception of making it relevant to contemporary times. Secondly, if the matter were simply of translation, of using technical terms properly, or of representing Indian thought in Western languages, the issues discussed here would be semantic. However, this is not the case. Semantic issues—questions of correct translation or mistranslation—refect deep conceptual confusions. Let us take for example the term “śruti.” Many scholars, notably Indologists, take for granted that this Sanskrit word translates into “revelation.” In its simplest and etymological rendering, “śruti” means “heard texts,” primarily referring to the Vedic literature due to its oral transmission. Translation of “śruti” as “revelation” raises serious questions regarding the deep structure of Indian philosophical thinking and signals a greater danger that many excellent writers do not realize. Translating śruti as “revelation” creates a conceptual muddle, and brings with it, additional conceptual ambiguities. 59 D A R ŚA NAS : PR E L I M I NA RY CONSI DE R AT IONS Thirdly, I am aware that literal translation from one language to another is impossible if one means by “literal translation” that which preserves the identity of meaning. Despite the best intentions of the translator not to jeopardize the integrity of original texts, all translations are at one level unavoidably interpretations, insofar as they involve the translator’s subjective frame of reference. This means that it is interpretations and translations of texts that are compared, not the original texts themselves. Those of us who work with Sanskrit texts and compare their ideas to Western philosophical ideas know very well the risk of such translations and comparisons. Even if we agree that there is no such thing as pure translation, that all translations involve interpretation, it is important that we make our interpretations as free from arbitrariness as possible. Recent research indicates that the two go hand in hand. For instance, the term “brahman” is often translated as “god” when the translator interprets it from a theological perspective but is more frequently translated as “absolute” when tinged with a purely metaphysical sense. Choosing one or the other of these translations of the term already predetermines whether the Upanisadic texts lie closer to theology or Hegelian metaphysics. So, for those scholars who depend upon translations of original materials, as well as for those who are the translators, some comparison is almost inescapable. In translating a Sanskrit text from Vedānta or Buddhism, one almost unavoidably uses the technical vocabulary of her contemporary philosophers’ writings in the language into which she is translating. So, for example, when Stcherbatsky translated Dharmak īrti into English, his translation was mediated by the philosophical vocabulary of the German Neo-Kantians. I think the same characterizes any translator. One may discard the antiquated language of the philosophers of the beginning of the twentieth century, but one would instead be using the language of more recent analytic philosophers. Engaging with any such translation then is covertly, and almost unavoidably, doing comparative philosophy. As the one who works on Indian philosophical texts and believes in the rapprochement between East and West in philosophy, I have several anxieties that relate to presenting Indian philosophy using the rhetoric of Western analytic philosophy. Over a decade ago, I reviewed a book proposal by two famous Indian philosophers from this part of the world for a university press. This proposal illustrated some of my anxieties—the authors’ goal was to “provide a comprehensive philosophical introduction to classical Indian philosophy” primarily “for students of Indian philosophy” and “Asian or non-Western philosophies in general.” To this end, the book was organized “around philosophical themes rather than religious systems,” and, since another aim of the book was to foster “interchange between the two traditions,” one of the chapters was titled “Transcendence.” It is understandable that these authors were presenting Indian philosophy in English and did not wish the book to become heavily scholastic and diffcult for a beginner, so they decided to translate “darśanas” as “religious systems.” The nine darśanas of Indian philosophy are by no means religious, let alone religious systems. However, there is the other 60 D A R ŚA NAS : PR E L I M I NA RY CONSI DE R AT IONS extreme, which consists in diluting the issues so much that the distinctive flavor of the original discourse is lost. A middle course, which I am sure, the authors wished to follow was to avoid the technicalities of the Sanskrit discourse and present Indian philosophical theses and arguments under the guise of Western philosophical rhetoric resulting in titling a chapter “Transcendence.” But it is important to use available English terms and concepts with extreme caution so that they do not jeopardize the integrity of the original philosophical discourse. When we are dealing with general issues, our preferences and prejudices may easily infuence our judgment. This is quite different from discussing specifc philosophical concepts within specifc Indian philosophical systems (darśanas), such as brahman, ātman, sāk ṣin,1 and cit.2 In such cases, the texts provide a constraint on one’s tendencies to arrive at conclusions not borne out by the texts, and usually, it is only after one has done textual research and interpretation that one is in a position to speculate on such general questions as the nature of Indian philosophy. However, here again, we should not indulge in the free play of our preferred choices. To determine the nature of Indian philosophy and present it accurately to Western students, one may look for specifc Western concepts to determine its nature; in that case, it is natural to ask how important Western concepts fgure in Indian thought and to subsequently search for their Sanskrit equivalents. Some obvious candidates of interest are which Sanskrit terms can be translated as “reason,” “experience” “intuition,” “transcendent,” “transcendental,” “spirit,” “spiritual,” etc., and alternately, which English terms may be used for “ jñ āna,” “pram āṇas,” “anubhava” etc. This leads to questions of conceptual meaning: Does “ jñ āna” mean “knowledge” in the Western sense of the term? Are pram āṇas “sources” of knowledge along the lines of “reason” and “experience” in Western philosophy? Is cit “transcendent” or “transcendental”? Is there a concept of “reason” in Indian philosophy? Are Indian philosophies rational structures, and if so, in what sense? Is Indian philosophy founded on “revealed” truths? Is Indian philosophy practical as opposed to a more theoretical Western intellectual tradition? In using Western concepts are we importing into our understanding of Indian thought concepts already loaded with the history of Western religion and philosophies? Clearly, the above questions cannot be answered without an examination of the crucial concepts entailed in them on which translations and contexts impact. This has impressed upon me that Indian philosophy must be examined in its own terms.3 This increasing awareness has compelled me to fnd a proper language, so to speak, in which to explain and discuss the structure of Indian philosophies. By “structure,” I mean the foundation, the reason, the logic, the rationality, that is specifcally Indian and refuses to be assimilated into the terms of Western logic. This is not to champion a complete separation between East and West, but rather an appeal to keep in perspective the fact that our search for philosophical universals should not blind us to the specifc features of Indian thought. 61 D A R ŚA NAS : PR E L I M I NA RY CONSI DE R AT IONS So, before undertaking an examination of the nine darśanas, I will review selected fundamental concepts and distinctions that are frequently used to present Indian philosophy to Western readers. Wherever necessary, I will place them in their historical context in the hope that this discussion will help my readers correctly understand the basic issues that surround Indian darśanas, remove some of their biases and preconceived notions, set the stage for ensuing discussion, enable the authentic nature of Indian philosophical discourse to manifest, and provide an inkling of this author’s framework. II Conceptual Considerations Jñāna and Knowledge Etymologically, “ jñ āna” is usually translated as “knowledge,” but it is important to keep in mind that the uses of these two words are different. In Western philosophy, it is linguistically absurd to say that “he knew that P” and that “P turned out to be false.” “S knows that P” entails that P is true. There is no such implication in the corresponding use of “ jñ āna” in the Indian tradition. In the Indian context, it is permissible that “S had jñ āna,” which, however, was false. A jñ āna is a cognition, an event, that happens to a subject, and when such a cognitive event is true, it becomes knowledge as pram ā (true cognition or true knowledge). Thus, not all cognitions are knowledge; some cognitions may be instances of error, doubt, wrong perception, etc. This distinction is already implied in the use of the Greek word “epist ēm ē,” from which “epistemology” is derived. “Epist ēm ē” is contrasted with “doxa” or opinion. Since the object of knowledge must be true, Plato asked in the Theaetetus: What do we know when we have a belief that turns out to be false? Let us say one falsely believes that 2 + 2 is 5. Does it imply that there are false facts, or should we say that in false beliefs we make a false combination of the elements where each constituent is really there, which means that the 2 is there, the 5 is there, but the sign of equality is wrong? There does not seem to be a good equivalent in Sanskrit of “doxa.” Like Parmenides, Plato regarded doxa as belief based on sensory perception; in Indian epistemology, perceptual knowledge was never viewed as falling short of true knowledge. This contrast between epist ēm ē and doxa in Sanskrit discourse confrms the point that “knowledge” implies truth, while “ jñ āna” does not. If one keeps in mind their differences, there is no harm in using “knowledge” and “cognition” interchangeably for “ jñ āna,” and that is how I have used it in this work. “Sources” of Cognition or Knowledge (Pram āṇas) Both Eastern and Western philosophers have tried to identify the “sources” of knowledge. However, there is an important difference between the two projects. Western epistemologists, taking “source” in a strict, literal sense, 62 D A R ŚA NAS : PR E L I M I NA RY CONSI DE R AT IONS developed two contrasting traditions—rationalism and empiricism—to address the question: Does knowledge arise from sensory experience or reason? In this question, “experience” and “reason” designate two different faculties of the mind. In the twentieth century, Karl Popper proposed that the very question of a “source” of knowledge is misleading, and modern Western epistemologists now claim to have completely left the project behind. However, for nearly 2,000 years, the search for the proper cognitive faculty dominated Western epistemology. In contrast, Indian epistemologists were not looking for such a cognitive faculty, nor a source of knowledge. They developed the theory of pram āṇas, which are means of knowing, a set of causal conditions that produce knowledge— but not a “source” in the strict Western sense given above. This difference partly accounts for the fact that the two theories of rationalism and empiricism which dominated the history of Western epistemology do not exist in Indian philosophy. The Concept of “Reason” The connotation of “reason” in the history of Western thought was once much broader than it has since become. The use of logic captured only a specifc function of reason. The word “reason,” derived from the Latin “ratio,” signifes “relation” or “connection.” When a logician or mathematician proceeds step by step and arrives at a conclusion, she is said to be grasping a relation or connection by means of reason. Similarly, one is using reason when on the basis of observing many men dying, she establishes a connection between mortality and humanity, inferring that “all men are mortal.” Thus, the reasoner makes observational generalizations and abstractions, and possesses the ability to grasp principles underlying events. In so doing, reason exercises its ability to analyze, refect, abstract, evaluate, justify, set principles, and perform other cognate functions. In contemporary times, it is customary to hold that “reason” means “logical thinking,” and that logical rationality signifes “logical validity.” Accordingly, when one asks whether a philosophical system is based on reason, one is really asking whether it can be logically established. On my thesis, though reason and logic are closely connected, they cannot be identifed. A philosophical position is rational if and only if it is adequately grounded in evidence and reasoning. By “evidence” I mean an experience, which presents the thing itself in the way in which a philosophical theory describes it. It is the grounding of a theory which makes it rational. One of the ways of grounding a theory is by logical proof, but this can only demonstrate the theory’s consistency, not its truth. The truth that a philosophical theory claims can only be demonstrated by experiential evidence, which together with logical consistency constitutes the rationality of a theory. Keeping the above in mind, I maintain that the pram āṇas of Indian philosophical systems constitute a theory of reason insofar as pram āṇa theory is 63 D A R ŚA NAS : PR E L I M I NA RY CONSI DE R AT IONS not only a theory of the way a true cognition is generated but also a theory of justifcation. A pram āṇa is that by which a prameya or an object of knowledge is established. Pram āṇas include perception, inference, comparison, śabda, postulation, and anupalabdhi. Each is a way of validating one’s beliefs, while at the same time, each is also a way in which one’s beliefs are generated. “Logic” as the “Logic of Cognitions” in the Indian Context4 In Indian discussions of epistemology, whatever is regarded as logic forms an important chapter. This is somewhat unusual when considered from the perspective of Western theories of knowledge. In Western philosophy, logic gradually achieved a kind of separation from epistemology, and almost the status of a completely independent and autonomous discipline. Today, a Western logician is concerned with the formal consistency and/or contradiction between propositions, which has nothing to do with whether the propositions express any true knowledge or not. Logic’s concern is not to determine the criteria for truth and falsity, nor it is to determine, given a proposition p, whether p is true or false. A Western logician frst removes all material terms from a concrete proposition, until she is left with only logical terms such as “all,” “some,” “none,” “is or is not,” “if-then,” “either-or,” etc. With such propositional forms as “if p then q,” “p and q,” “not p,” and “p or q,” the logician determines the truth value of any sentence in these forms by constructing truth tables for the functions. Reduced to this skeleton, the logician has a subject matter which is far removed from the concrete knowledge as though with the fesh and blood of concrete knowers. The Indian systems of logic maintain their concern with concrete knowledge or knowledges acquired by concrete knowers. Its domain is that of cognitive events occurring in the mental lives of persons. It asks such questions as: If a person sees (has a perceptual cognition of) smoke on a distant mountain at a temporal moment, what other cognitive events would happen in succession so that the person would be justifed in arriving at cognition of there being fre on the hill? To Western philosophers, such an interest in cognitive events has seemed an inappropriate diversion into psychology, which many wish to banish from logic totally and only marginally admit in epistemology. Though logic and psychological ultimately diverge in contemporary Indian thought, in their origins they were closely intertwined. To say a little more about this and the logic of cognitions, I can do no better than return to the theme of inference. Inference is generally treated by Indian logicians (Nyāya the chief among them), as being of two types: Inference for oneself and inference for another. The former is concerned with how a person arrives at an inferential cognition for herself, in the privacy of her own thinking. Obviously, here psychology dominates. A person sees a column of smoke arising from a hilltop, remembers the rule she has learned from past experience—wherever there is smoke there is fre—and then almost by necessity (call it logical or psychological or both) arrives at the inferential 64 D A R ŚA NAS : PR E L I M I NA RY CONSI DE R AT IONS cognition that there is fre on that hill. If one then wishes to convince another, then the original psychological process is cast into the purely logical form that the Naiyāyikas regard as a formal, fve-membered syllogism. Logic casts off its psychological garb and reveals a foundation that should hold good for any thinker’s attempt to convince the other. Note that in the psychological account of inference for oneself, each cognitive event occurs at a certain temporal moment and the order of succession between them becomes of central importance. Furthermore, all these successive cognitive events must occur, rather must belong to the same self. Cognition is not only a particular event brought about by specifc causal conditions, but it also has a content which is propositional and can remain identical amidst numerically different cognitive events. So, my perceptual cognition of smoke on the hill has the content: There is a column of smoke on that hill. Another perceiver who also perceives smoke on that hill will experience a cognitive event that is numerically distinct from my perceptual cognitive event, but which shares the same content. In this sense, a proposition, like an entity, can be abstracted from perceptual cognitions of infnitely many subjects so that logic of cognitions is possible. Jñāna and Truth To determine the concept of “truth” in the Eastern and Western traditions, I will begin by asking the question: What precisely is the bearer of truth in the two traditions? Truth in Western philosophy may be taken to belong either to a declarative sentence or a judgment or a proposition. A sentence is a linguistic entity: It is either in English, or German, or Sanskrit, or any other language. A judgment is a product of a mental act of judging or asserting something of something. A proposition is neither of these. It is the meaning of a sentence, a thought abstracted from any thinker, and may be judged about but is not necessarily the content of a judgment. Truth in Indian philosophy is predicated of a cognition. A cognition is not a linguistic entity; it is neither in English, nor German, nor Sanskrit. It is no doubt someone’s cognition—that is, it belongs to a knower—and cannot be identifed with an abstract proposition. It might seem as though it is a judgment; we know that at a minimum Kant seems to have taken knowledge in this sense. However, a judgment has a subject/predicate structure, while a cognition by itself does not have such a structure. A cognition is a complex relational entity consisting of several such epistemic components as qualifers, epistemic relations, and components that function as substantive. It is this complex entity that is said to have the property of truth when its structure and the structure of reality agree. Thus, Indian logic, irrespective of whether one has Vedānta or Nyāya in mind, is not a logic of sentences, nor of propositions, nor of judgments—but of, as we have already seen, cognitions. Indian epistemologists consider the extent to which our beliefs and propositions agree with reality, rather than simply assessing the consistency of 65 D A R ŚA NAS : PR E L I M I NA RY CONSI DE R AT IONS propositions. But epistemology can neither decide which of our beliefs are true or false nor tell us why. It can only ask very general questions, namely: What does it mean for a belief or proposition to be true or false? How can a general criterion for answering the truth question be given when material truths differ from case to case? It is here that the Indian philosophers have something important to say. A cognition is true according to Indian theories of truth if and only if— 1 2 3 its structure correctly represents the structure of reality, if the cognition is caused by one of the means of true cognition, and if it leads to a successful practical response. On this account, epistemology is not completely independent of questions about the origin of cognition and so it is not reducible to formal logic. Rather, Indian interest in logic, such as the theory of inference, has traditionally been epistemological; it considers inference as a means of acquiring genuine knowledge. So, in the Indian tradition, the discipline of epistemology intersects with logic and metaphysics, which have largely been kept apart in Western thought. Transcendent and Transcendental In my classes, I have been often asked whether the brahman (pure consciousness) is transcendent or transcendental. Here, it is important to keep in mind that the notion of “transcendence” employed to characterize the sub-feld of metaphysics and religion has its origin in Judeo-Christian theology. Additionally, the concept has different meanings in Kant and Husserl. In Kant, the transcendent is beyond the limits of possible experience; such supersensible entities as the soul, God, the universe are transcendent. “Transcendental” does not mean beyond the limits of possible experience; rather, it constitutes the conditions that make experience possible (a priori conditions of experience). In Husserl’s phenomenology, we bracket (set aside) what is transcendent or mundane, in order to reach the transcendental—that which constitutes experience along with its objects and the meaning these objects have. The brahman or pure consciousness may be regarded as both transcendent and transcendental. It is transcendent insofar as the experience of brahman is non-sensuous; it transcends all ordinary mundane experiences. It is transcendental inasmuch as the brahman is itself the possibility of any experience at all, without it nothing would be manifested or known. The Concept of “Concept” Western scholars have long talked about the role of conceptual thinking and discursivity in Western philosophy and its alleged absence in Indian philosophy. The conceptual thought in this case is differentiated from intuition. Several points are worth noting. 66 D A R ŚA NAS : PR E L I M I NA RY CONSI DE R AT IONS One may say that most, if not all, thinking is conceptual without presupposing a concept of “theory.” Socrates and Plato forged the dominant Western model of concepts (such as “ justice,” “goodness,” etc.) which have been reifed into entities of some kind, whether mental or not. They were less concerned with which discrete acts were good than with the concept of “goodness” itself. The meaning of a word, when reifed, becomes a concept. The task of philosophy has been to defne the concept in such a way that the content and limits are precisely stated. When Hegel remarked that Indian thought was not able to raise its intuitions to the level of concepts, he had meant that the subject matter of true philosophy must be concepts and not things that are intuited. It does not appear that Indian philosophy ever reifed concepts into entities, nor held that the domain of philosophy is the domain of all things, including the real things that we encounter in the world. Concepts, where they appear, are tools for thinking about things and not independent entities. The reifed concepts, one may say, are but reifed meanings. Indian philosophy shows extreme reluctance to admit meanings as distinguished from reference. 5 In fact, Indian thinkers typically—with the possible exception of some interpretations of the Buddhists apohav āda—eschewed a referential theory of meanings or the idea that words designate things.6 Given this theory of meaning, the Indian theory of defnition is an attempt to devise linguistic expression which would apply exclusively to the thing being defned, and not to anything more or anything less. Philosophical thinking therefore cannot be simply a logical analysis. As a conceptual analysis, it must derive its concepts from somewhere, either from language or from experience. However, in these two cases, irrespective of whether our fnal court of appeal is language or experience, we are dealing with resources that are at our disposal. Let me give an illustrative example. Philosophers, from the East and the West alike, are concerned with moral goodness. Mere logical and conceptual analysis cannot tell us what goodness is; we have to determine what people mean by “good.” This amounts to either linguistic analysis or experiential analysis (how people experience goodness, which implies appealing to moral experience). My contention is that Indians used conceptual thinking, but their concept of “concept” never became the Western concept of “concept.” Let me explain this point further using the concept of duty found in Kant and the Indian text Bhagavad G īt ā. The goal of Kant’s duty ethics was to identify a principle from which all our duties can be derived so that they are applications of a single principle. That is, a single moral principle in duty ethics is supposed to work as the criterion by which one can decide what one ought to do in all situations. Kant gives us the Categorical Imperative (the principle of the universalizability of maxims without contradiction). A moral rule in the Hindu context, on the other hand, is not a categorical imperative, that is, it is not an unconditional command. The dharma-imperatives in the G īt ā are hypothetical imperatives; they assume 67 D A R ŚA NAS : PR E L I M I NA RY CONSI DE R AT IONS the conditional form: “If you wish to achieve X, then you should do Y” rather than “you ought to do Y.” The latter, as an example of the strong Kantian notion of “ought” (which is completely independent of all consequences), is not available in Hindu thought. The Indian “concepts” are concrete concepts and the process of abstraction never reached the level of abstraction available in Western thought. A superfcial reading of Indian thought has suggested that the Indians were concerned with intuitive things, whether a perceptual object or a metaphysical reality, but this is not quite correct. The Indian philosopher’s interest was to give the lak ṣa ṇa (meaning by implication) of the perceived entity. To give a lak ṣa ṇa is to produce a linguistic expression sometimes consisting of negations, or at other times, a combination of negations with positive attributions, so that it applies to nothing else. Using language in this manner is precisely philosophical thinking. Thinking qua thinking is never materialistic or spiritualistic. The sort of objects which may qualify as thinking mostly derive from the subject matter of thinking rather than the nature of thinking. One would be completely mistaken if one held that thinking about matter is materialistic thinking or that thinking about spirit is spiritualistic. Thinking, however, may be good thinking, i.e., it is well-articulated, clear, elegant and in some yet to be defned sense, true of its object; or, thinking may be bad thinking, i.e., it is not clearly articulated, unclear, inelegant and may be true of its object in some sense. However, it is important to note that that thinking about vagueness is not eo ipso vague thinking. When Cezanne painted a vague landscape on a misty morning, the vagueness was clearly painted. A good thinker clearly thinks about what he or she is thinking about, irrespective of whether it is the brahman of Advaita Vedānta or the referent of Fregean semantics; it does not matter what one is thinking about. Clarity, by whatever standard it is gauged, is not enough. Where clarity is dictated not by the thinker’s methodological prejudice, but by the very nature of subject matter that one is thinking about, thinking achieves greatness. Finally, I believe that the contrast between concept and intuition is spurious; concepts are rooted in intuition, intuitions are concepts in the making, and concepts transform into intuitions when they are perfected. Both Indian philosophy and Western philosophy integrate intuitions and concepts and different systems and thinkers do so in different ways. This explains why an Advaitin speaks a language that is closer to Plato or Spinoza, while a Naiyāyika speaks a language that is closer to Bertrand Russell. The relative importance of intuition and concepts in the total structure of thinking varies from thinker to thinker, and not across the East and the West. Philosophical thinking is never merely conceptual, nor merely intuitive. I believe it is diffcult to speak about philosophy meaningfully in purely formal, general, abstract terms. Pure philosophy is an empty abstraction; we always have a contextual interpretation and reinterpretation, we have reference 68 D A R ŚA NAS : PR E L I M I NA RY CONSI DE R AT IONS to a culture, a tradition. Philosophy is a category, and once we defne what appropriately belongs to that category, we develop internal differentiations and variations. The major threads of philosophical thought—European, American, Indian, Chinese, and others—differ not just as a matter of geographical location, but of historical and social context. I hope the above provides my readers an inkling of the present author’s subjective frame of reference, insights into the historical and philosophical contexts of some of the important concepts used in Indian darśanas, and helps them understand Indian contexts from “within” so to speak and relate to Western conceptual apparatus in terms of thematic relevance. With this in mind, let us review the selected important features of the nine darśanas. III Important Features of the Dar śanas Before proceeding with our in-depth discussion of the individual darśanas, let’s look at some important features that most darśanas (excluding the Cārvā kas) share. 1 Each darśana has a pram āṇa theory. The technical word “pram āṇa” has been variously translated as “proofs,” “means of acquiring knowledge,” “means of true or valid cognition,” or “ways of knowing.” In other words, logic and epistemology are components of each of these nine Indian schools. The theories differ from darśana to darśana: The Indian materialists admit only the perception as a reliable source of valid cognition, the Buddhists accept both perception and inference, the Naiyāyikas add comparison (upam āna) and verbal testimony (śabda) to the list, and the Advaitins accept all four of these pram āṇas and add two more: Postulation or presumption (arth āpatti) and non-perception (anupalabdhi). 2 The pram āṇas are advanced not merely to validate empirical cognitive claims, such as “it rained yesterday,” or “it will rain tomorrow,” but also to validate such philosophical claims as “the world has a creator,” or that “the substance is permanent.” In most Western philosophies, philosophical and empirical statements are sharply differentiated, and the grounding of the empirical epistemic claims follows a pattern which is different from what the grounding of philosophical claims requires. Even the Advaita Vedānta school uses the pram āṇas to validate its basic thesis that reality is One, universal consciousness, although there is a ranking of the pram āṇas with regard to their relative strength. 3 In Western epistemologies, for example in Immanuel Kant, there is a continuing tension between the causal question of how a cognition comes into being and the logical question of its validity. This tension is not found in Indian epistemologies. The pram āṇas are at once the instruments by which true cognitions arise and the ways of justifying a cognitive claim. So, we 69 D A R ŚA NAS : PR E L I M I NA RY CONSI DE R AT IONS 4 5 6 7 8 may say, a perceptual cognition is valid or justifed if it arises through specifable conditions (for example, the contact of the sense organ with the object, etc.). This simple account of perception as a pram āṇa is too simplistic and requires several conditions to be added; the formula, however, indicates the overall structure. My claim amounts to this: In Indian epistemologies a causal theory of the origin also serves as a component of an epistemic theory of justifcation of cognitive claims. Another feature of the theory of pram ā ṇas, irrespective of the system one has in mind, is the primacy of perception. This feature has two aspects. First, every other mode of knowing presupposes and is founded on perception. This also characterizes inference (anum ā na) and verbal testimony (śabda)—One must see the smoke on the yonder hill to be able to infer that there must be smoke; one must hear spoken words, to grasp their meanings. Perception, however, is not limited to sensory perception. According to many schools, one also perceives universals and relations. Irrespective of the theory of consciousness held by the different darśanas, each affrms that consciousness plays the evidencing role in knowledge since every instance of knowledge is a manifestation of an object to and by consciousness. The schools disagreed regarding the self-manifestedness of consciousness, but that it is the only source of manifestation of an object was beyond dispute. This thesis led to an epistemological realism in the āstika darśanas, while the Buddhists combined it with certain constructivism. Though correspondence and coherence (samvāda) were widely used as criteria for truth, a pragmatist account of truth was common to all the darśanas. The two concepts, when available, tended to merge: Truth leads to successful practice (arthakriyāk āritva). There are many versions of it, but there is no doubt that the concept of “successful practice” did play a central role in the discussions of truth which points to a close relationship between theory and practice for the Indian mind. This relation has been noticed, but often misconstrued as implying that Indian philosophy lacks theoretical thinking, that thinking is motivated for the practical goal of freedom from the chain of karma and rebirth. The truth, however, lies deeper. We will learn, as we proceed further in our investigation, there is much theoretical thinking which, however, is taken as leading to a benefcial practical consequence. In this respect, Indian thinking is a close ally of the ancient Greek view, especially Socratic thinking, that philosophical thinking paves the way for cultivating a good life. The ultimate goal, not alone of philosophy but also of ethical life, serves as a spiritual transformation of existence. The presence of a spiritual goal for philosophical thinking has been well recognized but again, at the same time, misconstrued. “Spirituality” in the Indian context does not exclude theoretical thinking but demands that one searches for the truth in order to reach this goal. Saying that Indian philosophy is “spiritual” often 70 D A R ŚA NAS : PR E L I M I NA RY CONSI DE R AT IONS 9 10 11 12 13 calls up the misleading picture of a philosopher meditating in yogic postures. The admission of a spiritual goal does not mean that the methodologies applied in seeking that goal must, and do, exclude rigorous analysis and critical argument. The style of debate in classical Indian philosophy, carried out through case-making and rebuttals, belies this assumption. Much of philosophical thinking in Indian philosophy transpired in the form of objections and replies ad nauseum. At the same time, it is true that the practice of yoga was a pervasive component of Indian culture; it was practiced by the Hindus, the Buddhists, and the Jainas. Consequently, many philosophers, who excelled at theoretical thinking and critical argument, did also, as a matter of fact, practiced yoga. Consequently, various types of yoga developed consistent with the goal of each darśana’s specifc theoretical position. All the darśanas (except for C ārvā kas), accepted the following soteriological structure: karma and rebirth → (sa ṃsāra) bondage → mok ṣa. Each concept in this chain was differently conceived within each darśana’s theoretical system, with corresponding differences in their practices being the result. Indian philosophers engaged in what Western thinkers call “theory”; however, they neither conceptualized the idea of a “pure theory” nor glorifed it by making it autonomous. Rather, they made it a component in a process that is motivated by the spiritual goal of self-knowledge. Basic to the metaphysical theories of the classical schools of Indian philosophy is the distinction between the self and the not-self, and the goal of removing suffering through the cultivation of self-knowledge. At the same time, parallel to this spiritual pursuit, there is also a naturalistic/materialistic component of each darśana. So, there are two independent strands of thought: The naturalistic/materialistic and the spiritualistic. These two strands eventually merged, each retaining its own identity while infuencing the other. It may be a more authentic characterization of Indian philosophical thought to say that a reconciliation of the two seeming opposites, “nature” and “spirit,” is what it aimed at— analogously to the opposition between theory and practice. Ethics in the Hindu context parallels Hegel’s concept of Sittlichkeit, i.e., the actual order of norms, duties, and virtues that a society values. In classical Western moral philosophy, the task of ethics is to legitimize and ground our moral beliefs on the basis of fundamental principles (e.g., Kant’s principle of universalizability without contradiction, Mill’s principle of utility, etc.), Hindu ethical philosophies do not give a supreme principle of morality to legitimize all ethical choices, but rather cover a large spectrum of issues, encompassing within its fold a theory of virtues, a theory of rules, the ideal of doing one’s duty for duty’s sake, actual norms, customs, and social practices that an individual in society cherishes. The following are some of the maxims that the classical darśanas generally followed.7 The list is by no means exhaustive. 71 D A R ŚA NAS : PR E L I M I NA RY CONSI DE R AT IONS Maxims 1 The same thing cannot both be an agent and the object of an action. 2 Contradictories cannot occupy the same place (and locus) at the same time. 3 Every event must have a cause. 4 Every event must produce an effect. 5 No action is lost without producing an effect. 6 Nothing arises without having a cause. 7 Knowledge is freedom; it transforms the knower. 8 Desire is the cause of bondage. 9 Freedom from the chain of birth and death is possible. 10 Something cannot come out of nothing. 11 What exists cannot disappear without any residue. (Note: 3–6 defne the universality of the principle of cause and effect, and 10–11 state the eternity of being/non-being. Each of these maxims was changed, reformulated, and some almost rejected, viz., in Buddhism.) 14 In addition to such specifc maxims, darśanas have their own thematic and operative concepts. Here I am following Eugen Fink’s thesis that in a system there are concepts that are used but not thematized. He argues that just as a thing when illuminated casts its own shadow, thematization produces non-thematic concepts. He calls such concepts “operative” concepts.8 In the darśanas, some of the important thematic concepts are: “being,” “existence,” “reality-appearance,” “truth-error,” “method-spirit,” “world-beyond,” “the locus and its object,” “the pure-impure,” “self and liberation,” etc. Some of the important operative concepts are: “subject-object distinction,” “inter-subjectivity principle” (understanding and knowing the other), “relation between language and thought,” “preservation of thought and practices across time constituting a tradition,” etc. 15 There is no doubt that Indian philosophy (as also religion) does contain the idea of Īśvara, bhagavāna, or sag uṇa brahman as the creator of the universe. But even where the idea appears (as in the Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika and the Vedānta), the function of God, his “omnipotence” is limited by the eternity of fnite souls, the law of karma and rebirth, and the belief in the possibility of “mok ṣa.” Consequently, one does not fnd the idea of creation out of nothing. 16 The early Sanskrit philosophical texts always took the form of a disputation between a real or imagined opponent and a proponent, the author 72 D A R ŚA NAS : PR E L I M I NA RY CONSI DE R AT IONS himself. Indian philosophers usually employed three philosophical methods: 1 2 3 Logical arguments in favor of one’s own position and against the opponent’s position; phenomenological evidence in support of one’s position and against the opponent’s position; and a hermeneutical method to determine what the texts, especially the Vedic texts, mean. A cursory glance at these features of the darśanas leaves no doubt whatsoever that the darśanas were concerned with the philosophical problems: The nature of reality and the nature and sources of cognition, logic, ethics, the status of the empirical self, and so forth. These darśanas had a certain acceptance of the relation between the theoretical and the spiritual, and a certain conception of being from within the bounds of a tradition. Philosophy in the Indian tradition was not simply an intellectual luxury, a mere conceptual hair-splitting, or an attempt to win an argument or to defeat an opponent, though all these excesses characterized many works of Indian philosophy. Underlying them, there was an awareness of a thorough process of thinking toward a distant goal on the horizon for the individual person and, perhaps, for humankind overall. 73 Part IV NON-VEDIC DAR Ś ANAS Indian Materialism: The Lokāyata/Cārvāka Darśana and the Śramaṇas The Jaina Darśana The Bauddha Darśana 5 IN DI A N M ATER I A L ISM The Lok āyata/Cārvāka Darśana and the Śramaṇas I Introduction Many scholars hold that “the materialistic School of thought in India was as vigorous and comprehensive as materialistic philosophy in the modern world.”1 There is no need to enter into a discussion of this claim in this chapter. For our purposes, it is suffcient to note that, originally there were two trends in Indian thought: The materialistic and the spiritualistic. Of these two trends, it is the latter which came to fruition in the Vedas and the Upaniṣads, and we will have ample reasons to become acquainted with it in the chapters to follow; the former, however, is a neglected story, though the germs of the materialistic philosophy are found in the Upaniṣadic literature, e.g., in the Uddālaka conception that mind is created out of the fnest essence of food,2 in the Indra-Prajāpati dialogue that the self is identical with the body,3 in the early Buddhist literature,4 and in the repudiation of afterlife in the Kaṭha5 and the Maitr ī Upani ṣads.6 The materialistic tendencies, better yet, naturalistic tendencies,7 left a permanent mark on Indian thought. Naturalistic tendencies infuenced and greatly shaped such powerful systems as Nyāya, Vaiśeṣika, and Sāṃ khya—although these sought to combine both naturalistic and spiritualistic tendencies. In this chapter, I will discuss the Lok āyatas, the Cārvākas, and the Śramanas ̣ . These are ancient schools that antedate or were contemporaneous with the rise of Buddhism. The Buddhist texts, especially the Pāli Nikāyas, are excellent sources of our knowledge of the Lok āyatas, but more particularly of the śramaṇas. II The Lokāyatas The name lok āyata is very old. It is found in Kautilya’s Artha śāstra 8 where it is construed as ānvῑk ṣik ῑ. Buddhaghosa says that “the lok āyata is a textbook of the Vita ṇḍā s (sophists),”9 meaning that it discusses tricky disputation, sophistry or casuistry, that the non-Buddhists practiced.10 S. N. Dasgupta notes that lok āyata is as old as the Vedas, and it is quite likely that it was pre-Aryans.11 The word “lok āyata” has been variously translated as that which is “prevalent in the common world,” “the basis of the foolish and the profane world,” a “commoner” or “a person of low and unrefned taste,” etc.12 No lok āyata texts 77 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S have survived. Tucci, however, argues that from the fact that no lok āyata text is extant, one cannot conclude that no lok āyata text ever existed.13 Dasgupta echoes similar sentiments when he notes that a commentary on Lok āyata śāstra by Bhāgur ī with its commentary existed in ancient times, though it is diffcult to say anything about the author of Lok āyata śāstra.14 Scattered references to Lok āyata are found in the Vedic darśanas. On the basis of these “available fragments,” Bhattacharya concludes that “the C ārvā ka/Lok āyata system had developed along the same lines as M īmāṃsā, Vedānta, Nyāya, and Vaiśeṣika.” He further adds that there “was a base text” consisting of “s ūtras or aphorisms,” and many commentaries were composed to elucidate these s ūtras.15 In the second act of the allegorical play Prabodahcandrodayam, the teachings of the lok āyatas are summed up as follows: Lok āyata is the only śāstra; perception is the only source of knowledge; earth, water, fre, and air are the only elements; artha and k āma are the only two goals of human life; consciousness (in the body) is produced by earth, water, fre, and air. Mind is only a product of matter. There is no other world. Only death is mok ṣa. On our view, Vācaspati (Bṛhaspati), after composing this important śāstra, in accordance with our likings (inclinations), dedicated it to the Cārvā kas, who spread it through his students and students of the students.16 The Lok āyatas were around during the time of the rise of Buddhism and were known and condemned as being the “abusers of the Vedas,” “negativists,” “deniers of the after-world.” Their teachings seem to have two aspects: On the one hand, they indulged in destructive arguments, and, on the other hand, they were clearly connected with the practice of statecraft and politics. It seems their original interest was practical: Denial of the authority of the Vedas, of “another world,” i.e., of life after death, the denial of morality (“no good or bad”), the rejection of the idea of God, of reward and punishment, and the elevation of the absolute monarch to the status of the wise person. The art of sophistry and negative disputation gradually came to be a system of philosophy with its own metaphysics and epistemology and came to be known as the Lok āyata/C ārvā ka darśana. III The Cārvāka Darśana In the history of Indian philosophy, the C ārvā ka darśana is associated with materialism.17 Cārvā ka, traditionally classifed as a n āstika school, is the most radical of the Indian philosophical schools. It denies the authority of the Vedas, excessive ritualism, rejects the Hindu immortal soul, the existence of another world, i.e., life after death, the distinction between good and bad, the doctrine of karma, and supernaturalism. It accepts perception as the only pram āṇa, embraces hedonism, supports philosophical skepticism, takes the 78 I N DI A N M ATER I A L ISM entire material world as consisting of four material elements. Consciousness, Cārvā kans argue, resides in the body; it is co-extensive with the body and perishes when the body perishes. The history of the school is uncertain. It is diffcult to say whether there was a historical person named Cārvā ka. Sarvadarśanasa ṃgraha states that a sage named “C ārvā ka,” the disciple of Bṛhaspati, founded this school.18 Bṛhaspati is equated with Vācaspati, the eponymous founder of the C ārvā ka school of Indian philosophy.19 MBH mentions the name C ārvā ka.20 Bṛhaspati is equated with the teacher of gods who put forward materialism among the demons in order to ruin them. Bhattacharya notes that the school known fnally as the C ārvā ka/Lok āyata did not fourish before the sixth century CE or a bit later. It is only from the eighth century CE that the name C ārvā ka is associated with a materialist school (some later writers such as Śāntarak ṣita and Śa ṅ kara continued to call it Lok āyata). Both names, however, came to refer to the same school of thought after the eighth century CE.21 There is a difference of opinion regarding the original meaning of the word “Cārvāka.” Etymologically, Cārvāka is derived from “carv” meaning “to eat” or “to chew” and vāk = word; so, the term describes a materialist who taught hedonism, enjoy this life, there is nothing beyond. Alternately, the name “Cārvāka” may also mean the words that are pleasant to hear (cāru = nice or sweet). Fundamental Postulates 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Perception, the only means of true cognition. Consciousness is an epiphenomenon of the body. Material world is made of four material elements, viz., earth, water, fre, and air. There is no soul, after-life, and God. There is no law of karma. Hedonism is the standard of morality. Pleasure is the only thing desirable as an end. There is no heaven and hell. The life ends in death, which is mok ṣa. Irrespective of the meaning of the word “c ārv ā ka,” tradition maintains that another name for this school is Lok ā yata (based on the etymology: loka + ayata, “prevalent in the world”) and its followers are known as “lok āyatikas.” 22 79 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S As materialism developed from being a general denial of all morality to being a well-argued philosophy with its logic, epistemology, and ethics, Cārvākas came to be recognized as philosophers and continued through the ages to be included among the classical darśanas. Their negativist rhetoric of deriding the Vedic beliefs changed into a philosophical style. It is quite possible that the negative portrayal of the Cārvāka school has been exaggerated because no lokāyata texts with the exception of the Tattvopaplavasiṃha (“the lion that throws overboard all categories”) have survived.23 Regarding the Tattvopaplavasiṃha (TPS), its editors hold that this text more precisely belongs to a “particular division”24 of the Cārvāka school and that this work carries the skeptical tendencies of the Cārvāka school “to its logical end.”25 Bhattacharya, on the other hand, holds that TPS is not a Cārvāka/ Lokāyata work: It represents the view of a totally different school that challenged the very concept of pram āṇa (means of knowledge).26 In reviewing the philosophical doctrines of the C ārvā ka school, we must keep in mind that the primary sources of our information are the writings of the opponents of C ārvā ka who sought to refute or ridicule it. It is unfortunate that we have no choice but to rely on such accounts. My exposition in this chapter will primarily be based upon such doxographic writings as Madhva’s Sarvadarśanasa ṃgraha (SDS),27 which portrays C ārvā kas as hedonists, and materialists, and calls this school “the crest-gem of the atheistic school.”28 In the opening paragraph, Madhva states, “The efforts of the Chārvā ka are indeed hard to be eradicated, for the majority of living beings hold by the current refrain— While life is yours, live joyously; None can escape Death’s searching eye; When once this frame of ours they burn; How shall it e’er again return?”29 It is not surprising that Madhva at the outset of his work presents C ārvā ka in a very unfavorable light, and sets up an adversarial tone vis-à-vis the brāhma ṇical tradition. The passage highlights and brings to the forefront the opposition between the C ārvā ka and the other schools of Indian philosophy. For example, the brāhma ṇical schools accept the four goals of life, after-life, the soul that survives the body, and the eradication of pain by mok ṣa. The C ārvā kas, on the other hand, propound a crude or unrefned form of hedonism, soul, and identify death with mok ṣa. Epistemology Madhva’s account of C ārvā ka epistemology may be summed up in the following words: 1 2 Perception is the only valid source of knowledge. Neither inference nor testimony is a valid source of knowledge. 80 I N DI A N M ATER I A L ISM 3 4 5 The self is the body. Consciousness arises from a combination of natural elements. There is no dormant consciousness in the fetus; consciousness does not continue after death. Pram āṇas30 (Means of Valid Knowledge or True Cognition) in the Nine Schools of Indian Philosophy Notwithstanding the differences among the different schools of Indian philosophy regarding the nature, number, and function of the pram āṇas, it would be helpful to provide a listing of the pram āṇas recognized by the nine schools of Indian philosophy: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 C ārvā ka Jainism Buddhism Vaiśeṣika Sāṃ khya Yoga Nyāya 8 Vedānta (Advaita) Perception Perception, Inference, and Testimony Perception and Inference Perception and Inference Perception, Inference, and Testimony Perception, Inference, and Testimony Perception, Inference, Comparison, and Testimony Perception, Inference, Comparison, Testimony, Postulation, and Non-perception 9 M īmāṃsā • Bhāṭṭ a • Prābhā kara Perception, Inference, Comparison, Testimony, Postulation, and Non-perception Perception, Inference, Comparison, Testimony, and Postulation The C ārvā kas argue that perception is the only means of knowing the truth: Whatever is available to sense-perception is true; whatever is not, is doubtful. In order to defend this fundamental epistemological position, they reject inference, testimony, and comparison as pram āṇas. They reject inference (anum āna) because there is no suffcient ground for ascertaining the truth of vyāpti (universal concomitance). Madhva states: Those who maintain the authority of inference accept the sign or middle term as the causer of knowledge, which middle term must be found in the minor and be itself invariably connected with the major. Now this invariable connection must be a relation destitute 81 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S of any condition accepted or disputed; and this connection does not possess its power of causing inference by virtue of its existence, as the eye, &c., are the cause of perception, but by virtue of its being known. What then is the means of this connection’s being known?31 Let me give an illustrative example: “on perceiving smoke on a hill, one infers that there is fre.” The inference assumes the following form: All cases of smoke are cases of fre. The hill is a case of smoke. Therefore, the hill is a case of fre. This inference is based on the vyāpti: “wherever there is smoke, there is fre.” The C ārvā kas ask: How does one determine the validity of the universal major premise, i.e., the universal relation of co-existence between the major term (e.g., “fre”) and the middle term (e.g., “smoke”)? They state that such a universal relation can never be established. 32 The vyāpti can be established only when the invariable and unconditional concomitance is known to exist between the fre and the smoke in such a way that in every case when the smoke is present the fre is also present. They challenge the cognitive feasibility of proceeding from the known to the unknown. In other words, inference proceeds from the observed to the unobserved, and there is no guarantee that what is true of the perceived cases will also be true of the unperceived cases. Madhva argues that perception can only determine what we perceive now, but it cannot provide us with the necessary connection required for a valid inference. Perception of two things together does not establish a causal relation between them. 33 Our observation of a large number of cases of concomitance cannot eliminate the possibility of a future failure. Nor can a vyāpti be established by inference because inference itself is dependent upon the universal concomitance. To say that we can determine a vyāpti by inference is to open the doors to infnite regress. Madhva further argues: Inference cannot “be the means of the knowledge of the universal proposition, since in the case of this inference we should also require another inference to establish it, and so on, and hence there would arise the fallacy of an ad infinitum retrogression.”34 Śabda (verbal testimony) and upam āna (comparison) also cannot help us determine the relation of universal concomitance because knowledge generated by śabda and upam āna presupposes inference. So Madhva concludes: “Hence by the impossibility of knowing the universality of a proposition it becomes impossible to establish inference, &c.”35 We can only determine with a higher degree of probability, never with certainty, what is to be true in all cases. Thus, depending as it does on the apprehension of a vyāpti, anum āna is not a pram āṇa (means of true cognition). 82 I N DI A N M ATER I A L ISM The C ā rv ā ka critique extends to include śabda as a pram āṇa, because its validity is ascertained by inference. Additionally, the Vedic testimony has no cognitive value. Vedic v ākyas (sentences) are simply the idle utterances of the brahmins who sought to serve their own interests. All their words about “merit” and “demerit,” life after death, and sacrifces are completely useless from the cognitive point of view. In short, śabda also fails to deliver certain knowledge. By rejecting anum āna, C ārvā kas place themselves in a precarious situation, because any proof they give to prove the validity of their own position would require some sort of inference. How can C ārvā kas prove that perception is the only pram āṇa? At this juncture, C ārvā kas realize that there are only two alternatives open to them: Either accept the validity of inference as a means of true cognition or refuse to recognize perception as a source of true cognition. Both these positions have in fact been taken, the frst by Purandara and the second by Jayarāśi Bhāṭṭ a. Purandara, 36 a seventh-century C ā rv ā ka, accepts inference to strengthen perceptual beliefs and argues that it absolutely has no power to yield any knowledge of what lies beyond the limits of sensory perception, for example, the existence of life after death.37 Perhaps the rationale behind maintaining the distinction between the usefulness of inference in our everyday experience and in ascertaining truths beyond perceptual experience lies in the fact that an inductive generalization is made by observing a large number of cases of agreement in presence and agreement in absence, and since agreement in presence cannot be observed in the transcendental world assuming such a world exists, no inductive generalization relating to such a world can be made. Jayarāśi Bhāṭṭ a, argues that there is no valid ground for accepting perception as the only source of true knowledge, because perception itself cannot be regarded as the means for ascertaining the validity of perception. Jayarāśi not only attacks the C ārvā ka account, he also demonstrates the invalidity of all the pram āṇas accepted by such Indian philosophical schools as Nyāya, M īmāmṣā, Sāṃ khya, and Buddhism, and challenges the validity of the theories of knowledge put forward by them.38 He further argues that there is no valid ground for accepting the existence of material elements, because if perception is the only source of true cognition, how can one be certain that perception reveals the true nature of objects? So, he not only argues for the invalidity of all the pram āṇas but also the consequent invalidity of all metaphysical principles and categories. Thus, the title Tattvopaplavsi ṃha is highly appropriate as the main thesis of the book demonstrates the impossibility of establishing the truth of any view of reality. Metaphysics The C ārvā kas use their logical-epistemological thesis that perception is the only pram āṇa to support their metaphysical position, viz., everything arises 83 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S out of the combination of the four elements. These four elements constitute everything including self or consciousness. Their core metaphysical doctrines may be stated as follows: 1 2 3 Earth, water, fre, and air are the only realities. Consciousness arises from these elements in the same way as the intoxicating nature of a drink arises when elements are combined, though each element separately does not have that power to intoxicate. The so-called self or puru ṣa is nothing but the body possessed of consciousness. Regarding #1, it is worth noting that the C ārvā kas do not include āk āśa or “ether” as one of the elements in their list, since it cannot be cognized by sense-perception. Accordingly, they hold that all objects are composed of the above-listed four perceptible elements. It includes both animate and nonanimate objects. With regard to #2, the C ārvā kas argue that we perceive consciousness as existing in the body, therefore, it must be a property of the body. In response to the question, how can the four non-conscious elements when combined produce consciousness, the C ārvā kas state that just as intoxicating quality is produced during fermentation when yeast come in contact with the natural grape, sugar, water, etc.; similarly, consciousness arises when the four material elements are combined in a special way, though none of the four elements possess consciousness.39 In other words, consciousness is a by-product or the epiphenomenon of matter. There is no difference between the soul and the body; the soul is identical with the body. The C ārvā kas use #3 to reject both the Hindu belief in an eternal self and the Buddhist thesis that self is nothing but a series of impermanent states in rapid succession. When a person dies, nothing survives. What people generally mean by the soul is a body with consciousness. Whereas we do not perceive any disembodied soul, we do directly perceive the self as identical with the body in our daily experiences. Such judgments as “I am white,” “I am short,” “I am thin,” bear testimony to the fact that the self is not different from the body. Other schools of philosophy, especially the Naiy āyikas, subjected the two C ā rv ā ka theses—consciousness is generated by four elements, and that self is not different from the conscious body—to a devastating attack. While subscribing to the C ā rv ā ka thesis that quality cannot have an independent existence of its own, the Naiy āyikas40 argue that if none of the elements have the property of consciousness, their co-existence cannot produce it. It is absurd to say that consciousness originates when the material elements are combined in a defnite proportion. It is indeed true that when grapes, etc., are combined in a certain order intoxicating quality originates, which is found in the smallest quantity of wine; however, consciousness is never found when the parts of a body are separated, say, in an arm of the body, 84 I N DI A N M ATER I A L ISM or a leg of the body. In other words, the material body cannot be the locus of consciousness; it can only belong to a conscious self. Moreover, in the state of swoon or coma, there is no consciousness but the self continues to exist. There is no evidence that with the death of the body, the self also ceases to be. The C ā rv ā ka, in its epistemology, depends upon perception, but no perceptual evidence establishes that with death, the self also becomes extinct. Nor can the C ā rv ā ka use inference or any other form of reasoning to substantiate his position because he has already rejected inference as a pram āṇa. Indeed, the C ā rv ā ka critique of inference itself makes use of inference, and in so doing becomes guilty of self-contradiction. Additionally, how can C ā rv ā kas reject śabda as a pram āṇa, when they depend upon the words of their predecessors, teachers, etc.?41 In the face of such criticisms, the C ārvā kas modify #3, i.e., that self is nothing but the body possessed of consciousness, to 31 as follows. 31 It is the functioning sense organs that constitute the self. However, realizing that since there are many sense organs, some of which may be defcient (for example, eyes being blind), it would amount to saying that the self of a person are many, and, at times, in confict with each other, they again modify their position to 32. 2 3 The self is the body with the prāṇa (life-force) in it, which is due to the intersection of the body with the environment outside. This allows them to speak of one’s self in each body as well as of many instruments of experiencing, e.g., the visual, tactual, auditory, and taste sense organs. The life-force, the prāṇa, when inside a body, becomes “conscious,” but upon leaving the body, like the air outside, becomes unconscious. However, this would imply that there are different kinds of life-breath and that each of these constitutes a distinct self. Additionally, the breath, being exhaled out every moment, could not be the self. The C ārvā kas again change their position as 33. 3 3 The self is manas (mind); consciousness is located in the manas (which experiences pleasure and pain, and whose properties are desire, jealousy, etc.). There is one manas in each body. But manas being subtle, i.e., lacking as it does gross dimension, cannot be perceived, which would make pleasure, pain, etc.—that belong to it—imperceptible. Additionally, if the self is the manas, it could not have the sense of “I.” All these criticisms lead the philosophers to posit a self as distinct from the body, the sense organs, the life force, and the manas. Sadānanda in his Ved āntasāra notes that there were four schools of C ārvā ka: One school takes self to be identical with the body; the second with the vital breath; the third with the sense-faculties, and the fourth with the mind.42 The distinction is based on the different conceptions of self where each succeeding view is more refned than the preceding one. However, all schools agree that self is a by-product of the matter. There is no transcendental being or god. There is no heaven or hell; life ends in death. Consciousness originates with a 85 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S specifc concatenation of the four physical elements known as the living body and disappears when these four elements disassociate. I will conclude this section with the following remarks. In reading C ārvā ka, the readers must not lose sight of the following: (1) lack of extant texts makes it diffcult to ascertain with certainty the views C ārvā ka actually held; (2) our knowledge of their doctrines is primarily drawn from their opponents who ridiculed and criticized them; and (3) most schools of Indian philosophy took great pains to answer C ārvā ka objections, which brought the critical spirit and rigor of the Indian classical schools to the forefront.43 II The Śramaṇas The voice of the C ārvā kas was the voice of protest against excessive ritualism, superstitions, and exploitation by the brāhmi ṇs. It is worth noting that the C ārvā ka was not the only school to voice its protest against the brāhma ṇism. There was the reaction of the local self-governing republican communities against the monarchical systems which the brāhma ṇism of the Vedas and the Upaniṣads had glorifed. However, by the sixth century BCE, another class of philosophers had exercised a tremendous infuence on the Indian tradition. As the Vedic culture originating in the Eastern valley began to spread eastward along the Gangetic plains, there arose a reaction against many of its excesses. This reaction was as much religious as it was social and political. It was a time of great upheaval and turmoil in India. The old structures of tribunal republics had begun to break down, and new kingdoms had begun to take shape. There was a great deal of uncertainty; old ways were being replaced by the new ones. Many wandering ascetics and mendicants, with different philosophical and religious ideas, had begun to establish their authority and superiority. These people did not belong to a specifc class, though they provided a formidable challenge to the authority of the brāhmins. Fundamental Postulates 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Experience is the only source of knowledge. There is no ātman; there is no brahman. The universe is not created by god or any supernatural power. Vedic ritualism is useless. Heaven and hell are invented by deceitful brāhmi ṇs. There is no after-life. There is no law of karma. There is no distinction between good and bad. 86 I N DI A N M ATER I A L ISM In general, this class of teachers and philosophers lived the lives of wandering mendicants, rejected the Vedic proliferation of deities and ritualism, the Upaniṣadic conception of the ātman and the brahman, the doctrine of rebirth and karma, the effcacy of action, the domination of the priestly class, the distinction between good and bad, and argued that heaven and hell were invented by deceitful brāhmi ṇs in order to exploit people to earn their livelihood. These wanderers were known as the “śrama ṇas” (recluses). Much controversy surrounds the śrama ṇas of the Indian tradition. We do not know about their social origin. This group of wanderers rejected the Vedic deities, brāhma ṇism, i.e., the conceptions of ātman, brahman, karma, and rebirth, but otherwise differed a great deal among themselves. We, however, know that they abandoned their family lives and offered alternative ways of knowing the truth. In general, they appealed to experience as the source of knowledge, and, in so appealing, aligned themselves with the empiricists. Regarding the nature of the universe, their views varied considerably, however, they believed that the universe is not created by any supernatural power or god. They subscribed to a sort of the naturalistic conception of the universe insofar as they believed that within nature there are different reals: Matter, life, mind, etc.; there is nothing beyond nature. The reference of the śrama ṇas (from “śram” meaning “to exert”) or those “who practice religious exertions” is found as early as the BU, where it occurs alongside t āpasa (from “tapa” meaning “to warm”) or who practice religious austerities implying that the śrama ṇas, like the t āpasas, belonged to a class of religious ascetics.44 Numerous references to śrama ṇas are found throughout the Buddhist texts, both earlier and later. It is diffcult to ascertain with certainty whether the “śrama ṇas” of the BU refer to the śrama ṇas found in the Buddhist literature. The oldest Buddhist records, i.e., the P āli Nik āyas, mention that the Buddha met some of them to discuss their views. Each of these śrama ṇas had many lay and ascetic followers. The Buddhist text S āmaññaphala Sutta (“Fruits of the life of a śrama ṇa”) provides a description of the six śrama ṇas of the pre-Buddhist India in the course of a dialogue between Ajātaśatru, the king of Magadha, and the Buddha.45 The text lists six śrama ṇas: P ū ra ṇa Kassapa, Makkhali Gosā la, Ajita Keśakambali, Pakudha Kaccāyana, Niganṭha Nātaputta, and Sañjay Belaṭṭhiputta. P ū ra ṇa Kassapa was an antinomian who denied all moral distinctions between good and bad. He held that theft, murder, and robbery are not bad, and acts of charity and sacrifce are not good. He argues, “In generosity, in self-mastery, in control of the senses, in speaking the truth, there is neither merit nor increase of merit.”46 His theory is known as the “no-action” theory (akriyāvāda). The soul does not act, so no merit accrues to a person from sacrifces, just as no demerit arises from the so-called bad actions. There is no cause and condition for knowledge and insight.47 The P āli epithet “p ūra ṇa” 87 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S means “complete” or “perfect”; accordingly, P ū ra ṇa’s followers believed that he had attained perfect knowledge or wisdom. Makkhali Gośā la, the leader of the Ājīvika sect, was a contemporary of Mahāvira, the twenty-fourth perfect soul of Jainism. Pāṇ ini48 notes that Makkhali or maskarin wandered here and there carrying a maskara (bamboo staff). Makkhali taught that neither purity nor sufferings of men have any cause and that one’s actions have no effcacy, power, or energy. There are no moral obligations. He denied karma and agreed with P ū ra ṇa that good deeds have no bearing on transmigration which is governed by “niyati” (fate), a rigid cosmic principle. The attainment of any given condition, of any character does not depend either on one’s own acts, or on the acts of another, or on human effort. There is no such thing as power or energy, or human strength or human vigour …. They are bent this way and that by their fate, by the necessary conditions of the class to which they belong, by their individual nature: and it is according to their position in one or other of the six classes that they experience ease or pain.49 One often hears that Ājīvikas followed severe ascetic practices. They gave up household life, covered their bodies with a kind of mat, carried a bunch of peacock feathers, abstained from taking ghee and sweets, and practiced begging. It is diffcult to determine why the Ājīvikas prescribed moral observances as well as also denied their value. Makkhali himself observed religious practices, not as a means of attaining mok ṣa, but to gain a livelihood. Ajita Keśakambali is taken to be the earliest representative of materialism in India. He was called “ke śakambali,” because he wore a blanket of hair on his body. He—in addition to denying moral distinctions, “merit” and “demerit”—taught that there is neither this world nor the other world, there are no recluses, no brāhma ṇas in this world, who after reaching the highest “walk perfectly, and who having understood and realised, by themselves alone, both this world and the next, make their wisdom known to others.”50 A human being consists of the four elements, viz., earth, water, fre, and air, and after death, these elements return to the original elements (earthy to earth, the fuid to the water, the heat to the fre, the wind to the air, and his faculties (the fve senses and the mind) pass into space. 51 As a corollary to his metaphysics of materialism, in terms of ethical teachings, Ajit held that there is no merit in offering sacrifces, there is no life after death, and no one passes from this life to the next. Good deeds do not give rise to any result (phala). No ascetic has reached perfection by purifying the mind, following the right path, and has experienced this world and the next world. Pakudha Kaccāyana, argued that there are seven things which are neither made nor “caused to be made.” The four elements, i.e., earth, water, fre, and air, are the roots of all things. These elements do not change qualitatively, meaning thereby that they are permanent; they unite as well as separate 88 I N DI A N M ATER I A L ISM without human intervention, i.e., without any volitional activity. In addition to these unchangeable entities, of the three additional elements, viz., pleasure, pain, and soul, pleasure and pain are the two elements of change and bring the four elements together along the lines of Vaiśeṣika adṛṣṭa. Finally, the soul is the living principle, prāṇa (vital breath), or what we understand by “ jīvātm ā”; there is nothing transcendent. Pakudha is taken to be the forerunner of the Hindu Vaiśeṣika school.52 Niganṭha Nātaputta is another śrama ṇa discussed in this text. “Niganṭha” means “a man free from bonds”; he is self-restrained. A nigan ṭha “lives restrained as regards all water; restrained as regards all evil; all evil has he washed away; and he lives suffused with the sense of evil held at bay. Such is his fourfold restraint.”53 Sañjay Belaṭṭhiputta denies the possibility of certain knowledge: “If you ask me whether there is another world—well, if I thought there were, I would say so. But I don’t think, it is thus or thus. And I don’t think it is otherwise. And I don’t deny it. And I don’t say there neither is, nor is not, another world.”54 It is quite possible that Sañjay was the frst to formulate the four-fold logic of existence, non-existence, both, and neither. These śrama ṇas with the exception of Niganṭha Nātaputta directly or indirectly deny the moral basis of karma and mok ṣa. Ajita Keśakambali (ke śa = hair, kambala = blanket) propounded materialism, and may very well have been the forerunner of the C ārvā ka in India. Gośā la is taken to be the founder of the school known as Ājīvikas. Sañjay, the agnostic, may be the teacher of Sāriputta, one of the famous disciples of the Buddha. Niganṭha Nātaputta or Mahāv īra is associated with Jainism. Jayatilleke argued that in order to do justice to the doctrine of the skeptics, he will use Ājīvikas to denote those śrama ṇas “who were neither Jainas, Materialists, or Sceptics.”55 The Jaina tradition portrays Gośā la, an ascetic, as a person of a low family born in a cow-shed (go- śala). Apparently, Gośā la once approached Mah āv ī ra and expressed his desire to become Mah āv ī ra’s disciple; Mahāv ī ra, however, refused to accept him. Imitating Mahāvira, Gośala became a naked man and declared himself to be a “ j īna,” “a victor,” a t īrtha ṇkara (a person who has mastered all passions and attained omniscience). Mah āv ī ra exposed Gośā la’s true nature for who he was, that he was a fake and declared that he, Mahāv ī ra, was the only true j īna, not Gośala. He is said to have codifed the Āj īvikas six factors of life: Gain/loss, joy/sorrow, and life/death. It is diffcult to say with absolute certainty whether the Jaina account of Go śala is correct, but there is no doubt that the Buddhists took the Āj īvikas to be their main rival because they practiced extreme self-mortifcation and rejected the Buddha’s Middle Way. In P ā li Nik āyas, one frequently comes across such compounds as śrama ṇa-brāhma ṇa which refers to two different groups of holy ascetics, the former denoting ascetics of all affliations and the latter denoting only the upholders of the Vedic tradition. It is worth noting that the brāhma ṇas were never referred to as śrama ṇas and the Buddha was referred to as mah ā (great) śrama ṇa. 89 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S The rise of the śrama ṇas marks the end of the Vedic period, the beginning of the Upaniṣadic era, and a confict between the śrama ṇas and the brāhma ṇic philosophies. The śrama ṇas became a powerful force in India of those days; their voice was the voice of protest to get rid of the oppression of the past and embrace different perspectives. The emergence and the rise of Jainism and Buddhism provides an eloquent testimony to their infuence, and I will discuss these schools next. Study Questions 1. Explain the C ārvā ka materialism. The Cārvā ka school argues that consciousness arises from a combination of the natural elements. Argue for or against this thesis. 2. Explain C ārvā ka epistemology. The school recognizes perception (pratyak ṣa) alone as a reliable source of knowledge. Given that the Cārvā kans do not recognize inference as a valid source, how can they claim that perception is the only source of valid knowledge? Discuss critically. 3. Discuss the hedonistic ethics of C ārvā ka. Does it appeal to you? Give reasons for your answer. 4. Who were the śrama ṇas? Discuss the central theses of the six śrama ṇas discussed in this chapter. Why are they important in the history of Indian philosophy? Suggested Readings Readers seeking an introduction to C ārvā ka will proft from, Daksinaranjan Sastri, A Short History of Indian Materialism (Calcutta: The Book Company, Ltd., 1957); Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya, Lok āyata: A Study in Ancient Materialism (Bombay: People’s Publishing House, 1959); S. N. Dasgupta, A History of Indian Philosophy (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1975), Vol. 3, pp. 512–550; Ramkrishna Bhattacharya, “What the C ārvā kas Originally Meant: More on the Commentators on the ‘C ārvākas ūtra,’” Journal of Indian Philosophy, Vol. 38, No. 6, December 2010, pp. 529–542; and E. B. Cowell and A. E. Gouch (tr.), Madhva, Sarvadarśanasa ṃgraha, (Vārāṇasi: Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series, 1978). Eli Franco, Perception, Knowledge, and Disbelief: A Study of Jayarāśi’s Scepticism (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1994) contains a very useful introduction, a detailed analysis, and translation with notes of the frst half of TPS. For śrama ṇas, see B. M. Barua, A History of Pre-Buddhistic Indian Philosophy (Calcutta: University of Calcutta, 1921), Part III, and A. L. Basham, History and Doctrine of the Ājīvikas: A Vanished Indian Religion (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1981). 90 6 THE JA INA DAR Ś A NA I Introduction Many religious and philosophical movements have contributed to the rich tapestry of Indian philosophical darśanas. Of these, the Jaina darśana, traditionally classifed as a n āstika darśana, is famous for its metaphysical thesis of anek āntavāda (reality has infnite aspects), the logical thesis of syadvāda (a proposition does not admit of only two truth values—true and false—but seven, and the doctrine of ahi ṃsā (not only physical non-injury but also intellectual and psychological non-injury). Jainism is the only philosophical account known to me that accommodates competing and rival positions while leaving open the possibility of many other perspectives. The school is also known as “Śrama ṇism” (a term that is used for all non-brāhma ṇical sects) and “Nigranṭḥism” (“bondless” because of its emphasis on non-possession, the conquest of unwholesome tendencies, and asceticism). The extensive Jaina literature is based on the teachings of Mahāv īra (literally the “great hero”), a senior contemporary of the Gautama Buddha. The term “Jainism” is derived from the Sanskrit root ji, “to conquer,” meaning the victor who has conquered his desires and passions, destroyed the karmas, and has become a perfect soul. Not much is known about Mahāv īra’s life. His given name was Vardhamāna. He was the son of Siddhārtha, a k ṣatriya, chieftain of the Licchavis, born at a place near modern Patna in Bihar, married a woman named Yaśodā at an early age, had a daughter, and at the age of twenty-eight left his home and became a mendicant. He led a very austere life for twelve years and wandered naked in the Gangetic plains. He met Buddha during his wandering days and discussed his philosophical ideas with him. Makkhali Gośala, the leader of the Ājīvikas, met Mahāv īra during these years and witnessed many miracles Mahāv īra had performed. The tradition maintains that during his thirteenth year, after fasting for several weeks, Mahāv īra became a jina, a “conqueror” or a “spiritual victor.” He became a “t īrtha ṇkara” (literally “one who makes a ford”), the omniscient one. There is no divine revelation in Jainism; a jina restores the tradition for succeeding generations. The tradition’s monastic and lay adherents are called “Jains” (“Followers of the Conquerors”) or “Jainas.” 91 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S Jainism is a living religion of India. The designation applies to approximately four million members of India’s most ancient śramaṇa tradition. Whereas Buddhism traveled far and wide outside of India and underwent radical transformations over the centuries, Jainism primarily remained confned to India. Though there are some Jaina communities outside India, most Jains reside in India. Its doctrines have remained unchanged, with the exception of minor details. Contrasted with the Buddha’s compassionate nature, Mahāv īra’s doctrines and practices seem to have been marked by severe austerity, and in the words of a modern scholar, a “peculiar stiffness”1 characterizes the Jaina doctrines. The tradition maintains that Mahāvīra is the founder of this school. Given that he was the twenty-fourth tīrthaṇkara (“ford maker,” a perfect soul, the one who shows the path across the rounds of rebirths to kevalajñāna), this thesis is technically false. Tradition reckons twenty-three prophets preceding Mahāvīra, who proclaimed that he is the last, the twenty-fourth, the frst being Ṛṣabhadeva, and Pārśva the twenty-third, who lived 250 years before Mahāvīra. Pārśva’s monks observed four vows; namely, ahiṃsā, i.e., the vow of non-injury (non-violence), satya (the vow of truthfulness), asteyam (the vow of not taking what is not given), and aprigraha (the vow of abstinence from all attachment). Mahāvīra added the ffth vow, viz., brahmacarya (celibacy), made nudity mandatory, imposed severe restrictions on everyday activities, and implemented total renunciation. Mahāvīra taught for thirty years as a tīrthaṇkara and entered nirvāṇa at the age of seventy-two. He left behind a well-organized Jaina community, thousands of monks, laymen, and laywomen; it also included many followers of the ancient order of Pārśva. In due course, the followers of Mahāv īra became the leaders of the lay Jaina monks. In the frst century CE, the Jaina community was divided into two sects: The orthodox, practicing the nudity rule of Mahāv īra, came to be known as “Digambaras” or “space clad” (the fundamentalists, who considered women second class citizens, and held women must be reborn as men to become a jina, i.e., a “perfect soul”), and Śvēt āmbaras or “white-clad,” (liberals, wearing the white clothes, accepted women in their order, and held that women can attain liberation). Jain scriptures are called āgamas, and like the Vedas and the Upanisads, they were transmitted orally from one generation to the next. Mahavira’s followers collected and developed his teachings. Initially, the Jaina composed their rules and teachings in Ardham āgadhī language (prākrit dialect) spoken in the Western part of India. Later works, however, were composed in Sanskrit. The basic aphorisms of the school were collected by Um āsvāti (also known as Um āsvāmi, third CE) in his Tattvārthadhigamas ūtra (also known as Tattvārthas ūtra). Other important works include: Hemacandra’s Anyayoga-vyavaccheda-dvātri ṃt īk ā (twelfth century), Malliṣeṇa’s Syadmañjari (thirteenth century), Haribhadra’s Ṣa ḍdarśanasamuccaya (nineth century CE), and Kundakunda’s Pañcāstik āyasāra, Pravacanasāra, and Samayasāra (second century CE). My analysis in this chapter is primarily based on Umā svāmi’s Tattvārthadhigamas ūtra/Tattvārthas ūtra. It presents basic issues of Jainism systematically without jeopardizing its authenticity. Additionally, both Digambaras and Śvēt āmbaras accept the authority of this text, and claim Umā svāmi or Umā svāti as their own. 92 THE JAINA DARŚANA Fundamental Postulates 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Reality has infnite aspects. All truths are “relative” to a standpoint. Every judgment is true from a certain standpoint (relationism). Perception, inference, and verbal testimony are the only means of true cognition. There are souls in every living being. Each soul can develop infnite consciousness, power, and happiness. Ahi ṃsā or non-violence is the most important Jaina virtue. Right faith, right knowledge, and right conduct constitute the path to mok ṣa. There is no God. The philosophical outlook of Jainism is metaphysical realism and pluralism as it holds that the objects exist independently of our knowledge and perception of them, and these objects are many. Every living being has a soul and a body. Respect for life, i.e., non-injury to life, plays a central role in its teachings. Additionally, the importance Jainism places on the respect for the opinions of others fnds expression in its theory of reality as many-sided or multiple viewpoints, and (anek āntavāda) leads to its logical doctrine that every judgment is conditional (syadvāda). Thus, various judgments about the same reality may be true when each is subjected to its own conditions. I will begin with Jaina metaphysics. II Jaina Metaphysics At the outset, it must be noted that Jaina metaphysics is a thorough-going realism, which is best articulated in the position that whatever is manifested in the form of a cognition is in the nature of the object of that knowledge. If in a cognition, the form “blue pitcher” is given, then there must be a blue pitcher that is being manifested. The Jainas take great pains to avoid absolutism and to demonstrate that everything is relational. Their decisive statement is: a thing has infinite aspects. In its anek āntavāda or the many-sided conception of reality (non-absolutism), Jaina philosophers argue that each philosophical position is true from a certain perspective. They sought to synthesize these perspectives, not by putting them together as “p and q and r…,” but as alternates (p or q or r…), each valid from a point of view (naya). It is important to note in this context that this notion of a “point of view,” is not subjective; it is an objective point of view. So, the perspectives are all objective and yield truths that are true, but only within that perspective, not absolutely. Jainas argue that emphasis on one aspect to the exclusion of others is analogous to the story of seven blind men who upon seeing an elephant describe the elephant based on the part (the trunk, the ears, the tail) of the 93 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S elephant they had touched. Each naya is partially true; nonetheless, it yields true knowledge. These partial cognitions need to be synthesized to get a complete knowledge of the object. So, for Jainas objects are complex in structure, and to comprehend their entire nature, they must be examined from various perspectives. The objects have innumerable characteristics, both positive and negative. For example, an object, say, a chair, has such positive qualities as shape, weight, color, etc., and negative characters, which distinguish it from other objects, say, a table, a stool, etc. Additionally, over time an object may lose some of its characteristics, assume different characteristics, which makes us realize that an object really possesses innumerable characteristics. It is not possible for an individual to know an object in all its characteristics; only omniscient beings possess knowledge of an object in all its aspects. The thesis of the infnite characters of an object leads Jaina philosophers to make a distinction between that which possesses the characteristics and the characteristics themselves, i.e., between a substance and attributes. Each substance has two kinds of attributes: Essential and accidental. The essential characteristics (gu ṇas) of a substance are permanent; they belong to a substance as long as it exists. For example, consciousness is an essential attribute of the soul. Accidental characteristics, on the other hand, are transitory; they come and go. Desires, pleasure, pain, etc., are such accidental characteristics of the soul. It is through these accidental characteristics that a substance undergoes changes and modifcations, and these accidental characteristics are called “modes” (paryāyas).2 A substance is real; it consists of three factors: (1) permanence, (2) origination, and (3) decay of changing modes. Jainas in their metaphysics explain the nature of the universe without resorting to a god as the creator of the world, preserve elements of the theory of atoms, and construe karmas as subtle matter-particles. The Jainas classify substances into extended and non-extended. Extended substances are divided into jīvas (souls, the principle of sentience, consciousness) and ajīvas (insentient or non-living objects). There are four ajīvas: (1) dharma, the medium of motion, (2) adharma, the medium of rest,3 (3) āk āśa or space, and (4) pudgala or matter. K āla or time is the only non-extended substance; extended substances are a collection of space-points, which time is not. I will quickly review the Jaina classifcation of substances. Extended Substances J īva (Soul) The soul is not perceived by the outer senses; its existence is inferred. Such experiences of self-awareness as “I am happy,” “I know,” “I believe,”4 testify to its existence. The soul is different from the body. A dead body does not possess such properties as knowledge, desires, and feelings. A non-conscious body, the Jainas argue, cannot be the locus of these properties. A body is composed 94 THE JAINA DARŚANA of physical elements. The sense organs are located in the body, and the soul uses them as instruments to see colors, hear sounds, etc. But the soul in itself is identical neither with the body nor with the sense organs. Knowledge is the essence of the jīva (soul); therefore, the soul can know everything directly.5 Sense organs, light, etc., are indirect aids in the production of a cognition ( jñ āna) when the impediments are removed. It is the soul that remembers the past experiences; so, recollection is not a function of any one of the sense organs. Were it so, it would not have been possible for a person who now has become blind to remember his past experience of seeing something (or, if he is now deaf, say, of past hearing)? There is an infnite number of souls distinct from the bodies and the sense organs. One of the unique features of the Jaina conception is the belief that the soul in its empirical state is capable of expansion and contraction according to the size of the empirical body.6 The Jaina thinkers argue that just as a lamp illuminates the area, small or large, in which it is placed; similarly, the soul expands and contracts contingent upon the size of the physical body. Most Indian thinkers, on the other hand, believe that the soul is not capable of expansion and contraction. Past actions yield fruits now or shall yield them in the future, because the actions now gone, leave their impressions on the soul. Here the Jaina metaphysics comes to its peculiar position where it seems to contradict itself. Karmas are impressions left behind by actions. These karmas are material, but they are construed as clinging to the immaterial soul. Karmas in Jainism are construed on the analogy of atoms; they are tiny material entities, the impressions of the past actions, and cling to souls. Souls are omniscient and each soul can attain omniscience only when the veil that conceals the nature of the soul is removed.7 Souls are classifed into those that transmigrate and those that are liberated. Transmigrating souls are tied to their bodies owing to their karmas. These souls are either moving or unmoving, depending on the nature of their bodies. Whereas the immobile souls are one-sensed, the mobile ones are two, three, four, or fve-sensed. Animals, plants, any particle of the matter of earth, water, fre, and wind also possess souls. Aj īvas (Insentient or Non-living Objects) 1 Dharma and 2. adharma are not taken in their usual senses of virtue and vice respectively, but rather as the conditions of movement and rest respectively.8 They are eternal and passive extended substances. These two pervade the entire mundane space. Though these two substances are not perceived, they are postulated to explain the possibility of motion and rest that we perceive in our daily lives.9 It seemed to Jaina thinkers that since the world is constituted of atoms, these material elements would get scattered and distributed in the entire space, unless there is a principle to provide stability to material elements, and adharma is such a principle. 95 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S 3 4 They further argue that an opposite principle is needed to explain movements, and dharma is that principle. In the absence of these principles, there would be no worldly structure, no distinction between loka (this world) and aloka (beyond this world), no constancy, and there would be utter chaos. Āk āśa or space is infnite10 and its function is to accommodate other substances. The Jainas distinguish between two kinds of space: Lived or mundane space (lok āk āśa), and the space beyond this world (alok āk āśa).11 Space provides room for all extended substances. All extended substances exist in space. To put it differently, substances occupy space; space is occupied. Thus, unlike Descartes, a substance is not the same as an extension, it rather is the locus of extension similar to what one fnds in John Locke. Space is inferred; it is not perceived. Pudgala or matter is the raw stuff of which the universe is constituted; it is capable of integration and disintegration. It possesses four qualities: Taste, touch, smell, and color.12 Sound is not a quality of matter but a mode of it. One may combine material substances to form larger wholes or break them into smaller and smaller units. The smallest part of the matter is aṇu or an atom.13 Atoms may combine to form aggregates called “skandhas.” In Jaina metaphysics, these aggregates range from the smallest aggregate of two atoms to the largest aggregates which the entire physical world represents.14 The objects that we perceive in our everyday lives are compound objects, e.g., animals, senses, the mind, and so on. It is worth noting that pudgala does not simply mean matter; it functions as the basis of the body, and it is the material cause of the body, speech, mind, and breath.15 Non-extended Substance Time Time, constituted of the atomic moments of time, is present everywhere in the world; it is real. It does not extend in space. Time, argue Jainas, is a necessary condition of change, motion, duration, etc. It is one, indivisible, infnite substance,16 though there are cycles of it. A thing changes, continues to exist, assumes new forms, and discards old ones; all these presuppose time. Time, like space, is inferred, not perceived. The Śvet āmbara Jainis do not confer on time the status of an independent substance; they, however, maintain that it is necessary to explain the worldly progression. III Jaina Logic (Syādvāda) Syādvāda Jaina syādvāda is based on anek āntavāda, i.e., the Jaina attitude to the nature of things, that yields a logic, which is perhaps one of India’s most important contribution to world philosophy. For the frst time in the history of logic, 96 THE JAINA DARŚANA the Jaina philosophers came to speak of a seven-truth-valued logic, known as “syadvāda,” which has two components, “syad” and “vāda.” “Syad” means “in some respect,” or “from a particular standpoint,” while “vāda” means “statement.” The statement “this is a pitcher” is true, from a certain point of view, and, at the same time from another point of view, this is not a pitcher. Thus, a judgment may be true from a certain point of view; however, from another point of view, the same judgment may be false. So, “syad” should not be taken to mean “may be,” “possibly,” etc. It would be a mistake to regard “syadvāda” as a theory of doubt, uncertainty, and skepticism. It certainly is not skepticism; it rather is a doctrine of conditional certainty. This leads Jaina logicians to distinguish between seven perspectives from which the same statement or judgment can be evaluated.17 Of the sevenfold judgments or predications, there are only three primary modes: (1) existent, (2) non-existent, and (3) inexpressible. The seven are developed out of these three basic modes. Syadvāda Given a judgment p, the Jainas hold that 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 there is a perspective from which p is true; there is a perspective from which p is false; there is a perspective from which p is both true and false; and there is a perspective from which p is “inexpressible.” These four, the basic truth-values, were then combined into three more: there is a perspective from which p is true and is also inexpressible; there is a perspective from which p is both false and is inexpressible; and there is a perspective from which p is true, is also false, and is also inexpressible. I will provide an illustrative example. If p is “this is a pitcher,” then from the perspective of a certain place, time, and quality (e.g., “brown”), p is true; the pitcher exists. But from the standpoint of another region of space, time, and quality (e.g., “red”), this statement is false, i.e., the pitcher does not exist. The two standpoints may then be combined, and it may be asserted that as being in a certain region of space and time18 and as having a certain quality this pitcher exists, but also from another perspective it does not; so, p is both true and false. Being both true and false, and failing to combine the two values, p becomes inexpressible. The set of positive and negative properties of a thing cannot be exhaustively enumerated. Everything whatsoever has 97 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S therefore an aspect of inexpressibility. From a purely logical perspective, “p” becomes undecidable. Given these three possibilities, one generates from them the remaining four primary modes. The Jaina holds that such moral propositions as “truthfulness is a virtue,” or “killing is a sin,” can be regarded as having the seven truth-values. Let us apply these forms to a common moral judgment, “you should speak the truth.” 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 there is a perspective from which to speak the truth is a virtue (is); there is a perspective from which to speak the truth is not a virtue (e.g., to speak the truth before a hunter who is searching for a deer, or to speak the truth to a dangerous man who is after a woman) (is not); there is a perspective from which to speak the truth is wholesome and is a virtue, but from another perspective to speak the truth is unwholesome and is not a virtue (is and is not); there is a perspective from which without considering the situation or circumstance, we can never say whether truth-speaking is or is not a virtue (is inexpressible); there is a perspective from which to speak the truth is a virtue, but without considering circumstances, we cannot say whether it is or is not a virtue (is and is inexpressible); there is a perspective from which to speak the truth is not a virtue, but without considering circumstances, we cannot say whether it is or is not a virtue (is not and is inexpressible);19 and there is a perspective from which to speak the truth is a virtue, but from another perspective to speak the truth is not a virtue; so, we cannot say whether it is or is not a virtue (is, is not, and is inexpressible).20 To sum up: Syadvāda is a method of viewing a thing from different standpoints. It is a method of synthesizing apparently incompatible attributes in a thing from differing standpoints. As we will see shortly, different systems of Indian philosophy hold different views regarding the nature of reality: For example, the Vedānta school regards the brahman as permanent; the Buddha held that everything is momentary; the Sāṃ khya school regards prak ṛti as permanent-cum-impermanent and the puru ṣas as impermanent; the NyāyaVaiśeṣika school some of the real entities like atoms, time, soul, are permanent, while others, e.g., a jar and a cloth, are impermanent. The Jaina school, as distinguished from the above schools, maintains that everything is both permanent and impermanent. Everything has origination, destruction, and persistence. A thing is permanent from the standpoint of substance, but it is also impermanent from the standpoint of modes. Thus, it makes sense to say that the Jaina syadvāda emphasizes “the conditionality and limitedness of human power and human vision and therefore it applies to all humanly constructible positions.”21 98 THE JAINA DARŚANA IV Theory of Knowledge Whereas a naya, as explained above, is the knowledge of a thing from a certain standpoint, a pram āṇa gives knowledge of a thing in its totality. In a pram āṇa, knowledge cognizes a thing in all its aspects. Whereas the function of a pram āṇa is to comprehend the total nature of an object, a naya apprehends the object from a particular perspective. In other words, a pram āṇa lays bare the whole truth; a naya gives a partial truth. Initially, the Jaina commentators make a distinction between the two types of standpoints (nayas): Substantial standpoint (dravyārthika naya) and moded standpoint (paryāyārthika naya). The former focuses on the generic and permanent aspect of a substance, the latter on modes, changes, or transformations. Thus, a pitcher as a substance, i.e., as a pitcher, is permanent; however, as its form or quality, the pitcher is impermanent. Thus, whereas the substantial standpoint grasps the generic aspect, the moded standpoint grasps the specifc aspect. A pram āṇa, argue Jainas, is self-illuminating, manifests its object, and is not subject to cancellation. A pram āṇa is free from three kinds of bādha or cancellations, viz., doubt, error, and not knowing the specifc features of the object. Right determination of the object is the main function of a pram āṇa. Jainas regard knowledge as an evolution of the self and deny any positive and direct determination by the object in the occurrence of knowledge. The knowledge, in the long run, must lie within the self. The absence of objectdetermination in knowledge and the innate self-luminous character of knowledge give rise to the Jaina doctrine of omniscience. The self’s original essence is pure luminosity. The self in the absolute state is the pure transcendental principle of self-luminosity. The “object” according to Jaina, is an independent real entity. It is not one, but many; it is opposite to self in nature. It is ja ḍa or unconscious. It is subject to continuous transformation (pari ṇāma), possesses different qualities (gu ṇas), and modifcations (paryāya). Self also changes constantly; it evolves into the form of knowledge of the non-self. The not-self evolves into the form of the knowable for the self. However, the object does not literally enter the self. Thus, the Jainas reject not only the epistemological monism of Vijñānavada, but also the Advaita theory of non-difference.22 The senses, according to Jainism, have a double character. They partake of the nature of substance (dravya), but their being is psychical. The Jaina accepts only fve senses, not ten as the Sāṃ khya does.23 Sense organs of action do not fnd a place in the Jaina scheme; the senses are not the instruments of actions. Though not a sense, manas (mind) is the instrumental cause of sense-functions. Mind, from a functional point of view, is a power of the soul, though it has a body as its material support. The mind is extended all over the body; it is not atomic as the Naiyāyikas take it to be. Valid knowledge is either direct or indirect. Direct knowledge or perception is either sense perception that occurs through the sense organs or 99 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S mental perceptions, e.g., perceptions of pleasure and pain within. Perceptual knowledge is defned as the knowledge that is detailed. Empirical knowledge is produced by the senses and the mind.24 Empirical knowledge at times is produced by the cooperation of the senses and the mind together, but at other times, by the activity of the mind alone. For example, when I say “this is a chair,” it is produced by the joint activity of the sense of sight and mind: I see the table with the sight, but the recollecting that it looks like a chair requires the activity of the mind. In addition to empirical perceptions (external and internal) or knowledge, the Jainas speak of more innate knowledge, not dependent on sense organs and mind, a kind of immediate knowledge, which again is of three kinds.25 1 2 3 Avadhi, a form of direct perception, is the perception of things in remote space and time (roughly corresponds to what modern psychology calls “clairvoyance”).26 It is a kind of extra-sensory perception that enables us to perceive things that have form and shape. Things without form, e.g., dharma and soul, cannot be perceived by avadhi. Manaḥparyāya is the direct cognition of the thoughts and ideas of other persons (along the lines of Western telepathy). In this cognition instrumentality of the sense-organs is not involved; it involves mind-contact among different individuals. Such a cognition requires developed mental discipline. Kevalajñ āna, knowledge par excellence, is the total comprehension of reality. It is omniscience; there is no distinction of time as the past, the present, and the future in it. It is perfect knowledge. The soul acquires this knowledge when all the karmas are removed. There are certain interesting features of the Jaina theory of perception, which must be emphasized. 1 Unlike the Nyāya and M īmāṃsā systems, the Jainas do not defne perception in terms of its causes (e.g., by the contact of the sense organs with their objects), but rather by the nature of the knowledge, namely, by its character of being a detailed and clear knowledge of its object. Etymologically the term “pratyak ṣa” consists of “prati” (before, near, to) and “ak ṣa” (sense organ) or “prati” and “ak ṣi” (eye). Thus, “pratyak ṣa” is taken to signify both “before any sense organ” or “the eyes giving rise to direct and immediate knowledge.” It is usually contrasted with mediate (parok ṣa) knowledge signifying away from the sense organs or the eyes. Early Jainas, however, argue that “ak ṣa” means “self” or “ jīva” that comprehends all objects in space and time. So, knowledge derived from the self is pratyak ṣa (perception), and knowledge that is not derived from the self is mediate.27 Later Jaina philosophers, for example, Hemacandra in his Pram āṇa M īm āṃsā28 however, argues that “ak ṣa” can be taken either to mean the self that knows everything or sense organ. So, pratyak ṣa may mean either 100 THE JAINA DARŚANA 2 3 the knowledge that arises from the self alone or that which arises from the sense organ. The former, however, is superior to the latter; the former is non-sensuous, the latter is simply sense perception. Again, the Jainas, contrary to most Indian schools, do not recognize indeterminate perception. We perceive objects in the world. The Jainas in this regard are realists. The Jainas respect the Buddhist thesis that perception in the strict sense must be free from all conceptual construction (kalpan ā). Finally, the Jaina conception of sense organs is very different from the other Hindu systems which regard sense organs to be material objects of some sort or the other. The Jainas, on the other hand, regard them primarily as powers of the self, and the external perceptible organs as their outer supports. There are four mediate (parok ṣa) pram āṇas: Memory, recognition, anum āna, and āgama. The Jainas is the only school among Indian schools that recognizes memory as a pram āṇa. In memory, an object which was already grasped by a previous pram āṇa, now referred to as “that” (tat) is revived. Recollection signifes the awakening of some past impressions. To recollect “X” means, “X” was known directly in the past, left its impressions, and is recollected now as a result of the awakening of the impressions of “X.” It is a form of valid knowledge, argue Jaina philosophers because it is a correct impression of the thing perceived in the past. Recognition is a complex mental act consisting of both the elements of presentation and representation, perception, and memory. It lacks the sort of clarity that belongs to perception alone; one comprehends identity, difference, resemblance, and comparison in it. It assumes the form: “this is that.” It is the correct apprehension of a thing. It is worth noting that the Jaina school does not recognize comparison as a separate means of true cognition. Inference (anum āna), like the Nyāya inference, contains fve members: 1 2 3 4 5 The Hill is smoky. (Claim to be proven) Because it is fery. (Reason) Wherever there is smoke, there is fre, e.g., kitchen. (Example) The Hill is smoky. (Application) Therefore, the Hill is fery. (Conclusion) For Western logic, it is the major premise that conveys the relationship between the middle and the major terms. For the Nyāya logicians, this function is carried by the “example.” I will detail some of these issues in Chapter 12 of this work. It is worth noting that for the Jaina philosophers, tarka (reasoning) is also a means of knowing the vyāpti or the universal concomitance between the major term (sādhya) and the middle term (hetu) to arrive at the conclusion (anumiti), i.e., the knowledge gained from an inferential process. Tarka 101 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S is a unique source of such knowledge because neither perception alone nor inference alone can yield the knowledge of vyāpti. The Jainas, of all Indian philosophers, regard āgama (scriptural testimony) or śabda (verbal testimony) as parok ṣa (mediate) knowledge. By śabda they do not mean either the Vedic texts or the words of the Vedic seers as the Hindus do, but the words of the t īrtha ṇkaras (perfected souls). The Jainas identify āgama with āptavacana, i.e., the words of a trustworthy person. But they distinguish between two kinds of āpta: The ordinary and the extraordinary. The extraordinary āpta is one who has attained omniscience. Regarding the meaning of a sentence or (vākyārtha), the Jainas argue that words have meanings, both expressed and implied by virtue of which they get connected to form a unifed sentential meaning. While the Buddhists wavered a great deal on the issue of omniscience (some accepted it, while others did not) or even on the specifc question of whether the Buddha was omniscient, the Jainas had no doubt that the perfected souls, the jinas or the t īrtha ṇkaras, attain omniscience. Once the covering karmas are removed by the long process of self-purifcation, any human can attain omniscience. V The Jaina Ethics: Bondage and Liberation The most important part of Jaina ethics is the path to mok ṣa (salvation). The Jainas argue that the contact between jīva and ajīva brings about birth and death. Bondage results when soul and matter interpenetrate; freedom is their separation. Matter particles are the obstacles that infect the soul.29 The soul can attain omniscience if the obstacles are removed. It is important to keep in mind that karma in Jaina philosophy means both an action and the impression left on the soul by an action. Karma in the latter sense is the karmic matter attached to the soul. Collectively, the karmas are the sum total of the tendencies generated in the past lives that determine our present birth, i.e., the family in which we are born, our shape, color, longevity, and so on.30 The karmic matter is of eight kinds: Knowledge-covering, vision-covering, feeling-producing, delusion-causing, longevity-determining, body-making, status-determining, and obstructive ones.31 These determine one’s life until karmas are dissociated from one’s soul. The jīva on account of passions, desires, etc., attracts karma-matter, so there is an infux (āśrava) of the karma-matter in the soul. How much karma-matter one attracts depends upon the kinds of actions one has performed. Dissociation consists of two special kinds of entities, entities in a very peculiar sense, more appropriately process or steps: The stoppage of the karma-matter and the exhaustion of already attracted karmas. (The soul is not devoid of extension; it is coextensive with the living body. The soul is the jīva; it is matter as well as consciousness). The Jaina prescribes a path of self-purifcation, the path that leads to the gradual destruction of karmic matter and the recovery of self’s original omniscience, i.e., the knowledge of the nature of the soul. 102 THE JAINA DARŚANA The three jewels together, viz., right faith, right knowledge, and right conduct constitute the path to mok ṣa.32 Jaina commentators use the analogy of medicine as a cure to explain it. Just as the faith in the effcacy, knowledge of how to use it, and taking the medicine is mandatory for the cure to be affected; similarly, the three principles are necessary to remove suffering. Right faith is the basis and the starting point of the discipline. It is the attitude of respect toward truth. Such an attitude may be inborn or acquired. One begins the study of the Jaina writings with partial faith; however, when one gets deeper into them, rationally examines what is taught by the t īrtha ṇkaras, one’s faith in the Jaina teachings increases. In other words, with the increase of knowledge, faith increases. Five signs of the right faith are: Tranquility, spiritual craving, disgust, compassion, and conviction. Right knowledge is free from doubt, error, and uncertainty. It is the knowledge of the real nature of the ego. The Jaina writers outline different kinds of wrong views. 1 2 3 4 5 Uncritical and obstinate acceptance of views. A wise person does not accept any view without critical examination. Indiscriminate acceptance of all views. Such an acceptance leads to a dull-witted acceptance of all views as true. Intentional clinging to a wrong view due to attachment. Obstinate attachment to a wrong view despite knowing that it is wrong. The attitude of uncertainty and doubt about the spiritual truths. Sticking to the false beliefs and views owing to a lack of growth. The Jaina prophets preach the essential equality of all living beings. Equality is natural to all living beings, while differences among them are adventitious, primarily owing to the differences between auspicious and inconspicuous karmas. Besides, according to Jainism, any human can attain liberation. No particular status is a necessary condition for the attainment of liberation. The soul in the body is god. God, according to Jainism, is not eternal but has worked out his own freedom or liberation. The three categories (tattvas), god, spiritual teacher, and religion, in their true nature, are called “samyak” (right). Recognizing all living beings as oneself is the root of the right attitude. The opposite of “samyaktva” is “mithyā” (false or wrong). There are various types of wrong or false attitudes about things, about the highest good, about the spiritual teacher, about god, and so on. One should cultivate the attitude of seeing all beings as equal to oneself. There are four such attitudes: Friendliness, gladness, compassion, and neutrality. Right conduct is doing what is benefcial and avoiding what is harmful.33 The goal here is to get rid of the karmas that lead to bondage and liberation. Right conduct contains two sets of rules: The rules for the householders and the rules for the mendicants. The householders’ rules are less stringent. These are: Honesty in earning wealth, fearlessness, self-control, non-violence, not-lying, not-taking anything that is not given, refraining from illicit sexual relations, 103 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S limiting one’s possessions, limiting the scope of one’s immoral activities, limiting the things one will use, not indulging in senseless harmful acts such as giving harmful advice, giving to others the means of destroying life, not indulging in harmful thoughts, not indulging in harmless behavior, the vow to remain equanimous for a certain period of time, the vow of fasting and living like a monk for a certain length of time, and the vow to share with guests. For the mendicants, the rules of right conduct consist of observing fve vows and gradual curbing of the activities of the body, speech, and mind. For the stoppage of the karmas, one takes the fve great vows: Ahi ṃsā, i.e., the vow of non-injury (non-violence), satya (the vow of truthfulness), asteyam (the vow of not taking what is not given), brahmacaryam (celibacy), and aprigraha (the vow of abstinence from all attachment). Overall, there is the lifelong vow of universal brotherhood. Ahi ṃsā or non-violence is the most important Jaina virtue, just as “compassion” is for the Buddhists. It is one of the cardinal virtues; it signifes nonviolence in thought, deed, and action. Ahi ṃsā leads to pure love. Pure love or nonviolence may be negative or positive. In the negative sense, pure love abstains from causing the injury of any sort to any living being. In a positive sense, it is performing positive virtuous activities like serving or helping others and doing good to them.34 To sum up: Right faith, knowledge, and conduct are necessary for liberation. If one of the three is missing, there would be no mok ṣa. The perfected soul, according to Jainism, becomes a god. God, in Jainism, is not the creator of the world. There are thus (infnite?) many perfected souls and so one could say that there are many gods (not in the sense of polytheism) but in the sense of a community of spirits. The perfected souls are, as a matter of fact, all alike, and so the Jainas speak of one god, although there are many perfected souls. God is to be worshipped, not to please him, but in order to pursue the ideal of complete freedom from the accumulated karmas. One does not seek God’s mercy and help; one pursues the ideal that is actualized in him. VI Concluding Remarks In reviewing the ancient Indian philosophies, we see that there existed many nayas. Of all the nayas, two were most fundamental: The substance perspective (dravya-naya) and the process perspective (paryāya-naya). The Vedāntins adopt the former, the Buddhists the latter. The Jaina naya theory yields a framework for synthesizing both. For the Jainas, reality is both permanent and changing, universal and, positive and negative; there are really no binary oppositions among these as each of these is valid from a certain perspective. The complete nature of reality consists both of identity and difference, of permanence and change, of universal and particular. This synthetic approach of the Jainas is their most important contribution to Indian thought.35 The above discussion makes it obvious that the Jainas are not only realists and non-absolutists; they are also “relativists.” A “perspective,” on the Jaina 104 THE JAINA DARŚANA thesis, is not to be construed as a subjective way of looking at things, but an objectively partial view which singles out one aspect out of the infinite, objective, aspects of reality. Thus, Jaina “relativism” is not subjectivism. Perhaps, it is more accurate to say that it is “relational-ism.” A comparison with A. N. Whitehead’s metaphysical system worked out in his Process and Reality may throw some light on the nature of objective relationalism. In Whitehead’s system, every actual entity is related to every other actual entity. Thus, a thing’s having a certain color is always from a certain perspective. On Whitehead’s account, an infinite number of perspectives constitute each and every entity. His system is much more complex than the Jaina system, but it is not an exaggeration to say that the Jaina syadvāda anticipates Whiteheadian objective relativism. It is one of the greatest achievements of the ancient Indian mind. Study Questions 1. Explain the Jaina conception of anek āntavāda. Do you find their account plausible? Give reasons for your answer. 2. Critically discuss the Jaina syadvāda or the conditional standpoint. If there are weaknesses, explain clearly what they are. If you find the theory to be a good one, explain its strong points. 3. Explain the role of ahi ṃsā in Jaina ethics. Discuss to what extent the anek āntavāda and syadvāda are parts of the Jaina theory of non-violence. 4. Elaborate on the Jaina conceptions of bondage and liberation. 5. Comment on the following statement: “Karmas are impressions left behind by actions. They are material and cling to the immaterial soul.” Compare the Jaina and the Upaniṣadic conceptions of karma. Which one do you find more persuasive, and why? Suggested Readings For an excellent introduction to Jaina philosophy, see Padmanabh S. Jaini, The Jaina Path of Purification (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1998). Additional good introductions on Jainism are: Jeffery Long, Jainism: An Introduction (London: I.B. Tauris, 2013); Lawrence A. Babb, Understanding Jainism (Edinburgh: Duneding Publishing 2015); and M. L. Mehta, Outlines of Jaina Philosophy (Bangalore: Jaina Mission Society, 1954). For translations of some of the basic texts, see Tattvārtha S ūtra, That Which Is, Um āsvāti/Um āsvāmi with the combined commentaries of Umā svāti/Umā svāmi, P ūjyapāda, and Siddhasenaga ṇ i (San Francisco, CA: Harper Collins, 1994). 105 7 THE BAUDDH A DAR Ś A NA I Early Life and Enlightenment By the middle of the sixth century BCE, about the time the major Upaniṣads were composed, a new mode of thinking revolutionized the intellectual and religious scene of India; over the course of time, it impacted almost all of Asia. This revolution originated with an individual known as the Buddha. Details of the Buddha’s life—the exact date of his birth, his social background, his early experiences—are inextricable from the conficting legends that surround him.1 However, tradition maintains that he was born to Śuddhodana Gautama, chief of the Śā kya clan, and his wife Māyā in the foothills of the Himalayas around 560 BCE, on the border of India and modern-day Nepal. The name given to the Buddha at birth was Siddhārtha, and his family name was Gautama, so in his early years, the Buddha was known as Siddhārtha Gautama. His father, Śuddhodana, was the chief of the Śā kya clan, so Siddhārtha was also referred to as “Śā kyamuni,” or the “Sage of the Śā kyas.” The father, Śuddhodana, fearing a prophecy, shielded Siddhārtha from any kind of suffering and unpleasant experiences that might take him toward religious life. Śuddhodana made certain that the young prince was sheltered and indulged so thoroughly that he never wanted to leave the luxurious surroundings of the palace; as a result, he never saw the hard realities of life. Some accounts say that while he was still a boy, Siddhārtha did once beg his father to let him visit the lands beyond the palace. For this tour, his father reportedly had the scene swept clean of anything that might shatter Siddhārtha’s ignorance, and so the prince returned home satisfed and incurious. Other accounts inform us that Siddhārtha did witness one thing that stayed with him ever after: The sight of farmers cutting through earthworms as they plowed their felds, prompting him to feel a moment of sympathy for their suffering. When Siddhārtha turned sixteen, his father had him married to a beautiful princess named Yaśodharā, who gave birth to a son a year later. Siddhārtha named the child Rahula (“The Fetter”). Restless with married life, legend says, Siddhārtha commanded his chariot driver to take him to the city under cover of night. He witnessed three sights of ordinary human suffering that shattered his complacency: An elderly person, a diseased person, and a 106 T H E BAU DDH A DA R ŚA NA corpse. Confronted with the reality of illness, aging, and death for the frst time, Siddhārtha was deeply, existentially troubled. A fourth sight—an ascetic monk with a begging bowl— excited something new in him. Siddhārtha decided he must leave the palace and his indulged life, as well as his wife and young son, in order to learn what another kind of life he could live. Fearing that if he kissed his sleeping family in farewell they would wake up and he would not be able to leave, he crept away without a sound or a word. He traded clothes with his chariot driver, gave away his jewels, and cut off his long hair. He would fnd the monk, or others like him, and begin his life anew. There were two main strands of monastic practice in India when Siddhārtha started his quest for truth: The brāhma ṇas, followers of the Vedic precepts, and the śrama ṇas or recluses. The brāhma ṇas followed the path prescribed by Vedic rituals and remained engaged in society, recommending appropriate sacrifces and promising a life of enjoyment thereafter. The śrama ṇas followed a path of austerity and self-mortifcation, shunning all social responsibility by retiring to the forest to infict pain upon themselves and deny themselves any of the pleasures in life. Siddhārtha initially pursued the path of self-mortifcation. He met fve ascetics who believed that practicing austere self-mortifcation would help the practitioner gain great vigor of the mind and have extraordinary insight. Hoping to attain this insight, Siddhārtha began living on smaller and smaller quantities of food and practicing control of his breathing, learning to fall into a trance-like state for hours. It is said that he became so malnourished that his ribs protruded sharply, his eyes sank into his skull, and his sitting bones were sore. But he persisted, earning the respect of the other ascetics for his unwavering diligence. However, for all his efforts, Siddhārtha did not attain enlightenment this way; on the contrary, he fainted from starvation. This experience prompted Siddhārtha to realize that indulging every emotional whim and physical desire does not lead to wisdom, but neither does denying every physical need and eliminating all experience of pleasure. He left the company of the ascetics and took to wandering on his own across the Gangetic plains in search of the truth, encountering other ascetics, philosophers, and spiritual leaders with whom he engaged in dialogues. Chief among them were—the Ājivīkas, the skeptics, and above all, Mahāv īra, the twenty-fourth t īrtha ṇkara of Jainism—who revolted against many key ideas of brāhma ṇism. Finally, it is said, Siddhārtha stopped wandering and settled under a large pipal tree to meditate, vowing not to arise until he had discovered truth. Eventually, he did rise, enlightened, and the pipal tree was ever afterward known as the “bodhi” tree. What exactly happened during Siddhārtha’s illumination is a matter of some controversy. On one popular account, found in the Vinaya Piṭaka, he is said to have beheld all twelve links of dependent origination; this would be anachronistic, however, since the twelve links theory was a later development. A more reliable interpretation is found in the words of Śā kyamuni speaking to a brāhma ṇa in Majjhima Nik āya (MN). 107 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S Enlightenment2 The Mahasaccaka Sutta describes how, after destroying the “cankers of his mind,” it became purifed, without deflements, became established, and after attaining the concentration of the mind, the Buddha attained four cognitions: 1 2 3 4 Insight into his own past lives: He, then, directed his mind toward wisdom, and he recollected his previous existences one by one. He recollected the details, the names he had, the families he was born in, how he died, and so on. His ignorance was dispelled, and this was the frst light of wisdom he attained during the early part of the night. Insight into the past lives of Others: He, then, directed his mind toward wisdom, and he then recollected the birth and death of all living beings and realized the hold of karma and rebirth: Good acts lead to a happy birth and bad acts to a miserable life. His ignorance was dispelled, and this was the second light of wisdom he attained during the middle of the night. Insight into the Four Noble Truths: He, then, directed his mind toward wisdom and realized that all is dukkha. He saw the truth of Dependent Origination, the real nature of the world, when there is no ignorance, there is no karma formation, and this was the third light of wisdom he attained during the end of the night. Finally, at the dawn, the fourth knowledge was attained. Right knowledge is gained. Since one cannot observe the true nature of the highest with the human eye, it is necessary to possess “divine-eyes.” The designation Buddha, “the Enlightened One” or “the Awakened One,” was given to Siddh ā rtha after he attained nirv āṇa. His disciples mostly referred to him as Tath āgata, which means “he-who-has-thus-arrived-there,” and in his conversations with his disciples, the Buddha referred to himself as Tath āgata. After attaining nirv āṇa, the Buddha set out on a path to teaching the truth he had learned to common people (and not particularly to scholars), in a manner that was intelligible to them. The nirv āṇa of the Buddha was a verifed experience; he believed, thought, and acted the way he preached. He clearly thought that by following his path, anybody could reach nirv āṇa. The Buddha refused to answer questions about the existence of God, or the immortal soul persisting in an afterlife or the origins of the world. When asked if there is a life after death, or whether there is a temporal beginning of the universe, he sometimes emphasized that the answers to these questions were not necessary for a good life, at times stated that whatever answer he might 108 T H E BAU DDH A DA R ŚA NA give is likely to be misunderstood, and at other times maintained a Noble Silence, saying nothing on the matter at all. Here is a summary of one of the conversations that the Buddha had with his disciple Mā lu ṇ kyaputta, who demanded answers to the following questions, and threatened to leave the Buddhist order if the Buddha did not answer them. These questions were: Is the universe eternal? Is the universe non-eternal? Is the universe fnite? Is the universe infnite? Is the soul the same as the body? Are the soul and the body different? Does the Tath āgata exist after death? Does the Tath āgata not exist after death? Does the Tath āgata both (at the same time) exist and not exist after death? Does the Tath āgata both (at the same time) not exist and not not-exist after death?3 When Mā lu ṇ kyaputta went to the Buddha with these questions, the Buddha responded as follows: It is as if a man had been wounded by an arrow thickly smeared with poison, and his friends, companions, relatives, and kinsmen were to get a surgeon to heal him, and he were to say I will not have this arrow pulled out until I know by what man I was wounded, whether he is of the warrior caste, or a brahmin, or of the agricultural, or the lowest caste. Or, if he were to say, I will not have this arrow pulled out until I know of what name or family the man is … or whether he is tall, or short, or of middle height…or whether he is black, or dark, or yellowish…or whether he comes from such…. That man would die, Mā lu ṇ kyaputta, without knowing all this. It is not on the view that the world is eternal, Mā lu ṇ kyaputta that a religious life depends: it is not on the view that the world is not eternal that a religious life depends. Whether the view is held that the world is eternal, or that the world is not eternal, there is still rebirth, there is old age, there is death, and grief, lamentation, suffering, sorrow and despair, the destruction of which even in this life I announce.4 The Buddha was an ethical teacher and reformer rather than a metaphysician. He was strongly in favor of the effcacy of ethical practices and the possibility of reaching perfection in this life. His goal was to change our lives, to alleviate dukkha; it was not to argue about the nature of reality. However, when we do an in-depth study of the Buddha’s teaching, we realize that his views were profoundly shaped by his early conversations with the śrama ṇas, 109 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S the Jainas chief among them. Perhaps, M ā hāv īra—older than Siddhārtha by ten years—was a signifcant infuence on his thoughts; he would have heard his reasons for denying the existence of God, giving a naturalistic account of the world, affrming the existence of souls, rebirth, and karma and prescribing self-purifcation as the means of attaining spiritual perfection. While the Buddha agreed with the Jainas about the nature of rebirth and the ethical importance of non-violence, he still judged their practice of asceticism to be extreme and rigid. The Buddha also rejected the teachings of the brāhma ṇas, including their caste distinctions and sacrifcial rituals. However, it would be wrong to say that the Buddha rejected the entire Vedic tradition. He had sympathies with many Upaniṣadic beliefs, including the conceptions of self-knowledge, mok ṣa, and rebirth, as well as the pursuit of yogic practices. While rejecting the Upaniṣadic thesis about the eternity of ātman (soul), he placed a strong emphasis on the principles of karma and rebirth. The question naturally arose whether these two approaches are compatible, as the brāhma ṇas and Jainas represented often contradictory views. The Buddha characterized his teaching as madhyama pratipad, the Middle Way because it avoids all extremes—of being and non-being, self and non-self, self-indulgence and self-mortifcation, substance and process—in general, all dualistic affrmations. So, mediation between the extremes of brāhma ṇism and Jainism would be possible in his view. I am not trying to suggest here that the Buddha’s teachings were a mere hybrid of various ideas already around. He added his own interpretation and personal wisdom to other views, integrating them into a grand system. Nevertheless, it is always good to remember that no thinker, however original, is untouched by the cultural context which shapes his thinking, and the Buddha was no exception. Despite the Buddha’s rejection of authority, and of śabda (word) as a legitimate means of knowing, his own words attained the status of one of the authoritative means of knowing the truth. Many philosophical schools developed during the thousand-year history of Buddhism in India, not to mention the numerous schools of Buddhism that arose in Southeast Asia, Tibet, China, and Japan after it traveled to these countries. But, in the end, one piece of advice given by the Buddha on his deathbed to Ā nanda, his closest disciple, remains symptomatic of the Buddhist spirit. Asked by Ā nanda, “what shall we do after you are gone?” The Buddha replied, “be a light unto thyself” (“ātm āna ṃ prad īpo bhava.”) “Do not betake any external refuge; hold fast to the truth as a lamp.” The Buddha continued to preach and reply to inquiries from his disciples for over forty years. These discussions bring to light his perspective on many common questions of the day, but his remarks were not common. However simple the words of the Buddha, they were always packed with meaning, and one’s understanding of their meaning was contingent on one’s ability. Thus, it is not surprising that many of his statements stimulated discussions for generations to come. 110 T H E BAU DDH A DA R ŚA NA The Buddha is said to have died at the age of eighty in 483 BCE. As was customary during those days, he taught through oral instruction, and his teachings were handed down orally by his disciples to successive generations. Although his followers agreed that the goal of Buddhist practice is to overcome the suffering caused by the cycle of rebirth, they differed in their interpretations of the path to nirvāṇa and the relative importance of the specifc teachings and practices of various texts. This resulted in the division of Indian Buddhism into two primary branches: The Therāvāda school, or the “School of the Elders,” also known derogatorily as the Hinayāna school, or “Lesser Vehicle,” by the self-named Mahāyāna school, or “Greater Vehicle.” Varieties of Therāvāda Buddhism are practiced in Ceylon, Thailand, and Myānmār; Mahāyāna Buddhism is found in East Asian countries such as China (including the autonomous regions of Tibet and Inner Mongolia), Outer Mongolia, and Malaysia. Numerous schools of Mahāyāna Buddhism have fourished in Japan, such as Pure Land, Zen, Nichiren Buddhism, Shingon, and Tiantai (Tendai). My analysis in this chapter is primarily based on the Therāvāda Pali text Tipi ṭakas, or “Three Baskets,” consisting of the (1) Vinaya-Piṭaka, rules of conduct and discipline of the order; (2) Sutta-Pi ṭaka (also known as the Nik āyas), a collection of the sayings and sermons of the Buddha; and (3) Abhidhamma-Pi ṭaka, a discussion of philosophical issues. I will begin with the First Sermon of the Buddha. II The Middle Way and the Four Noble Truths Dharma Revisited Dharma (Pā li: dhamma) is a complex concept which has acquired a variety of meanings and interpretations in Buddhism. In Buddhism, dharma can have many different meanings in different contexts. 1 2 3 4 5 Dharma is a generic term used to represent the teachings of the Buddha. Dharma can be understood to be the True Doctrine, such as the Four Noble Truths which refect the fundamental moral law of the universe. Phenomena, in general, are dharmas, as are qualities and characteristics of phenomena. “Growing old is the dharma [nature] of all compounded things.” In a technical sense, dharma denotes the ultimate constituents or elements of the whole of reality. 111 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S After attaining nirvāṇa, the Buddha walked from Bodhgayā to the Deer Park near Vārāṇasī (Banaras) in northern India, where he set in motion what is known as the Wheel of Dharma. The Buddha delivered his frst sermon to a group of admiring and curious villagers who had assembled there. There was something unique about his speech as well as his audience. His audience did not consist of the members of the priestly class, of those who were adept in scriptures, but rather of the common village folks, who neither spoke nor understood Sanskrit. The Buddha spoke in the Pā li language and continued to preach in that language to make his teachings accessible to the common people. The Middle Way The brāhma ṇas encouraged the elaborate performance of various kinds of rituals and the śrama ṇas practiced different kinds of self-mortifcation; the Buddha had learned from experience the pitfalls of self-indulgence. In the doctrine of the Middle Way, he rejected the two extreme paths of selfmortifcation and self-indulgence—the former being demeaning and the latter useless—recommending instead a Middle Way between them. He says: There are two extremes, O recluses, which he who has gone forth ought not to follow: The habitual practice, on the one hand, of those things whose attraction depends upon the pleasures of sense, and especially of sensuality (a practice low and pagan, ft only for the worldly-minded, worthy of no abiding proft); and the habitual practice, on the other hand, of self-mortifcation (a practice painful, unworthy, and unproftable equally of no abiding proft). There is a Middle Way, O recluses, avoiding these extremes, discovered by the Tath āgata—a path which opens the eyes and bestows understanding, which leads to the peace of mind, to the higher wisdom, to enlightenment, to Nirvāṇa.5 The Middle Way leads from attachment to non-attachment, from existence to non-existence, and from self to not-self. In this context, one must not lose sight of the fact that “non-attachment” does not mean “craving for nonattachment,” “non-existence” does not mean “craving for non-existence,” and “not-self” does not mean “craving for not-self.” The Middle Way, the Buddha declared, is not the result of any metaphysical inquiry, or any mystical intuition; it has a purely empirical basis. He had arrived at this judgment by investigation and analysis. The Middle Way is deemphasis and devaluation of the extremes of existence and non-existence, both of which are rooted in ignorance. The Buddha condemned all existing dogmas and speculations, ranging from the affrmation of a permanent soul in the Upanisads to its denial in the materialism of 112 T H E BAU DDH A DA R ŚA NA Ajita who subscribed to the total annihilation of the soul after death. Between the two extremes also lay the fatalism of Ājīvikas and anek āntavāda of Jainism. The Buddha exhorted people to follow the Middle Path, informing his audience that his “Middle Way” leads to peace, insight, and enlightenment. The doctrine of the Middle Way, so much reminiscent of Aristotle’s as well as Confucius’ Golden Mean, gradually became a major theme of Buddhist philosophy. In fact, an entire school of Mahāyāna Buddhism came to be known as “madhyama” or the Middle Path. Fundamental Postulates of Early Buddhism 1 2 3 4 5 6 The Middle Way (the Dhamma) The Four Noble Truths Aniccā Anatt ā The Doctrine of the Dependent Origination The Highest Goal: Nirvāṇa The second important theme of the frst lecture focused on the Four Noble Truths, which state the fact of dukkha. These two, i.e., the doctrines of the Middle Way and the Four Noble Truths, form the foundation of the Buddhist philosophy. The Four Noble Truths The truth of dukkha articulated as the Four Noble Truths is formulated in a manner and style that follows a pattern of Indian medical literature anticipated in Caraka Sa ṃhit ā. The frst Noble Truth identifes the disease, the second the cause, the third informs us that it is curable, and the fourth outlines the path, the procedure by which the disease is cured. The Four Noble Truths 1 2 3 4 There is dukkha. There is the origin of dukkha (depending on causes and conditions). There is the cessation of dukkha (upon the cessation of causes and conditions). There is a path leading to the cessation of dukkha (the Noble Eightfold Path). 113 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S There is Dukkha In the First Noble Truth, the Buddha states the fact of dukkha, a pervasive fact of all human existence: Birth is painful, death is painful, disease is painful, and separation from the pleasant is painful. To drive home the omnipresence of dukkha, the Buddha told the story of a very distraught mother who came to the Buddha with her dead baby in her arms and asked the Buddha to restore his dead baby to life. The Buddha listened to her request and asked her to fetch a grain of mustard seed from a house where none had died. She searched for a long time in vain, and fnally, returned to the Buddha and informed him of her failure. The Buddha said: ‘My sister; thou hast found’, the Master said, ‘Searching for what none fnds - that bitter balm I had to give thee. He thou lovedst slept Dead on thy bosom yesterday; to-day Thou know’st the whole wide world weeps with thy woe: The grief which all hearts share grows less for one.’6 One’s understanding of the Buddha’s teachings depends upon how clearly one comprehends the concept of “dukkha,” and one of the roots of the development of Buddhism consists in precisely unfolding its meaning. Saṃsāra • • • Literally, sa ṃsāra means, “perpetual wandering,” indicating the cycle of rebirth, of coming around again and again, of going through one life after another. Sa ṃsāra in Buddhism is dukkha; it is perpetuated by desire and avidyā (ignorance). A single lifetime is not enough to appreciate the truth of dukkha entailed in existence. Sa ṃsāra is the unbroken continuum of the fve skandhas, constantly changing, forming an unending chain of rebirth. Dukkha signifes the universal feature of the entirety of sa ṃsāric existence. It is the opposite of sukha, hence “dis-pleasure,” “dis-comfort,” “dis-satisfaction,” “dis-content,” or “dis-ease.” This term has been variously translated as “pain,” “sorrow,” or “suffering.” These translations, however, do not really capture the essence of what the Buddha was trying to convey to his audience by this concept; the connotation is much wider and comprehensive. The Buddha discussed three tiers of dukkha, each more complicated and sophisticated than the previous one. 114 T H E BAU DDH A DA R ŚA NA Three Tiers of Dukkha Dukkha-dukkha Physical illness, pain, suffering Vipari ṇāma-dukkha Psychological suffering due to change Sa ṇkh āra–dukkha Existential suffering due to rebirth First, there is dukkha-dukkha, which includes physical illness, degradation due to aging, and bodily or psychosocial trauma. Second, there is vipari ṇāmadukkha, the dukkha on account of change; in this sense, enjoyment and pleasures are also dukkha, inasmuch as the pleasures that one enjoys pass away; they do not last forever. The Buddha was aware that there are moments of pleasure, there are moments of satisfaction of one’s desires, but he also realized that such moments are transitory; they are followed by the experience of unhappiness and longing for what is no more. Even when one gets what one wants, either one cannot hold on to it; alternately, one gets it, and then wishes to have more than what he does have and feels pain on account of the deprivation of what could have been. The Buddha emphasized that when the causes and conditions that produce pleasant experiences cease, pleasant or happy experiences also cease to exist. Saṇkh āras • • • • • • The term “saṇkh ārā” is derived from the prefx sam, meaning “together,” joined to the noun “kara,” meaning “doing, making.” Accordingly, “saṇkh ārā” signifes “co-doings,” things that act in concert with other things, or things that are made by a combination of other things. Sa ṇkh āras are the karmically active volitions; they are responsible for generating rebirth. Reinforced by ignorance and fred by craving, sa ṇkh āras drive the stream of consciousness onward to a new union of skandhas, and the character of the sa ṇkh āra determines the character of future birth. If one performs meritorious deeds, the sa ṇkh āras or volitional formations will push or move consciousness to a happy realm of rebirth. If one engages in demeritorious deeds, the sa ṇkh āras will push or move consciousness toward an unhappy rebirth. Sa ṇkh ārās, the second link in the Dependent Origination, are virtually used synonymously with karmas. 115 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S Pleasant or happy experiences eventually change to unpleasant or do not last forever. To be separated from what is pleasant is dukkha, to be joined with unpleasant is dukkha. Failure in getting what one wants is dukkha. It is the very nature of desire to breed new desires. So, far we have seen, dukkha connotes not only the well-known phenomena of illness, disease, old age, and death, which the Buddha had witnessed early in his life but also the deeper metaphysical truth that everything is impermanent. The Buddha, however, did not stop here; he provided the third tier of dukkha, i.e., sa ṇkh āra–dukkha. It is the dukkha of “conditioned” experience. “Condition,” in this context, signifes volitions that cause rebirth. Sa ṇkh āra–dukkha includes a basic unsatisfactoriness that characterizes entire existence, including that which we call an “I” or a “being.” An “I” is a union of changing, impermanent physical and mental aggregates; to search for permanence in an existence characterized by impermanence also causes dukkha. The above analysis reveals the complex nature of the Buddha’s concept of “dukkha.” It is dissatisfaction, discontent, disharmony, incompleteness, imperfection, ineffciency, physical and mental suffering, the confict between our desires and our accomplishments, the suffering produced on account of change, old age, disease, and death. It is the opposite of perfection, harmony, bliss, happiness, and well-being. Impermanence, the relativity of pleasure and pain, passivity (i.e., subjection to the causal chain), the lack of freedom and spontaneity, conditioned experiences, all point to the fact that existence is dukkha. Thus, when rightly understood, the truth that existence is dukkha implies a rejection of all metaphysics of permanence and replacing it with a metaphysics of impermanence. Ultimately, it suggests that metaphysical thinking ought to be avoided altogether. Given that dukkha exists, the question arises, what is the cause of it? Is there an end to it? If there is an end, how do we reach it? The Origin of Dukkha The Second Noble Truth discusses the origin of dukkha, that there is a cause of dukkha. Like a true medicine man, the Buddha states that one cannot cure the disease unless one is able to identify its root cause. The Buddha says: Now this, O recluses, is the noble truth concerning the origin of suffering. Verily it originates in that craving thirst which causes the renewal of becoming, is accompanied by sensual delight, and seeks satisfaction now here…that is to say, the craving for the gratifcation of the passions, or the craving for a future life, or the craving for success in this present life (the lust of the fesh, the lust of life, or the pride of life).7 The immediate cause of dukkha, the Buddha argued, is t ṛṣṇā, which is generally, though wrongly, translated as “desire.” Rather, t ṛṣṇā, is closer in meaning 116 T H E BAU DDH A DA R ŚA NA to “thirst,” indicating the cravings of fnite individuals, their selfsh needs and desires. These desires in turn breed attachments resulting in frustrations and disappointments, i.e., dukkha. But the remote and ultimate cause of dukkha is ignorance (avidyā) of the nature of things. The ignorance consists in mistaking what is impermanent for something permanent. There is nothing permanent, whether in the external world or within oneself. On account of ignorance, we ascribe to our own selves as well as to others a permanent soul, and we ascribe permanent essences to the objects of the world. The belief in permanence leads to desire, which in turn leads to attachments causing rebirth, which is dukkha. Accordingly, we have here a large thesis ready for generations of Buddhist thinkers to refect upon, viz., to determine what precisely constitutes existence, and how precisely to construe the idea of “desire.” The second and the third noble truth are based on the doctrine of the Dependent Origination, an important doctrine in the Buddhist teachings. It states that all dharmas (“phenomena”) arise depending upon other dharmas: “When this is, that comes to be; on the arising of that, this arises. When this is not, that is not; on the cessation of that, this ceases.” This doctrine, when applied to the specifc case of human existence, takes the form of a well-known twelve-membered chain, which I will detail a little later. Suffce it to note here that dukkha arises when we crave and cling to these changing phenomena. The clinging and craving produce karmas, and bind us to sa ṃsāra, the round of death and rebirth. These cravings include craving for sense-pleasures during our lives and craving to continue the cycle of life and death itself. In short, the list is traditionally interpreted as describing the conditional arising of rebirth in sa ṃsāra, and the resultant dukkha. At this juncture, it is important to underscore an important point. There is no concept of “original sin” in Buddhism, and no one is foreordained to be damned. There is no forgiveness of sins, no atonement because there is no one with the power to bestow forgiveness. Every cause gives rise to its inevitable effect; if we understand the cause-effect chain, then we can remove it if we wish to do so. Otherwise, the cause-effect chain, i.e., the never-ending cycle of birth and death continues. The Cessation of Dukkha The Third Noble Truth is an assurance that the disease, the basic problem of human existence, is curable. In other words, it is the assurance that dukkha can end. In the Buddha’s words: “it is the destruction, in which no craving remains over, of this very thirst; the laying aside of, the getting rid of, the being free from, the harboring no longer of, this thirst.”8 This cessation or extinguishing or extinction of all desires is nirvāṇa. It is not easy to ascertain precisely what the Buddha meant by nirv āṇa. Scholars have raised such questions as: If to exist is to desire, then does the cessation of all desires means cessation of existence? Is nirvāṇa a negative state 117 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S of ceasing to be? Or, is it also a positive experience of bliss? The Buddhist schools (yet to be discussed)9 differ among themselves on this important question. We know, for example, that Nāgārjuna distinguished nirvāṇa from all ways of looking (dṛṣṭis) at things. I will discuss some of these questions in the concluding section of this chapter. Etymological meanings of nirvāṇa, such as “cessation of,” “ceasing to be” or “blown out” suggest to some scholars that in nirvāṇa existence, which is permeated by dukkha, is extinguished. Nothing could be further from the truth. The Buddhist thinkers wrestled with the problem of describing nirvāṇa in more positive terms. One thing is obvious: Nirvāṇa is not a negative state of ceasing to be. The Buddha’s life testifes to this. The Buddha lived for forty-fve years after attaining nirv āṇa, teaching and showing laypersons how to attain nirv āṇa. So, it is safe to say that, in nirv āṇa, dukkha ceases to be, not the person himself. If the Buddha were alive today, he would have said that the words “positive” and “negative” are relative; they are applicable in a realm that is characterized by conditionality, duality, and relativity. Nirv āṇa is freedom from relativity, conditionality, and all evils; it is not the annihilation of a person, it is “Truth,” the term that the Buddha uses unequivocally several times in the place of nirv āṇa. One, who has attained nirv āṇa has extinguished cravings; he has become an “arhat.” Arhat • • Literally, it means, “worthy” or “venerable.” The term is used in Therāvāda Buddhism for the person who has reached the highest stage of spiritual development. Therāvādins require four extinctions for arhatship: (1) sensual desires, (2) desire to be, (3) wrong views, and (4) ignorance. A person who has conquered all four attains arhatship. So, the arhat is free from cravings, passions, desires, and rebirth. The question is often asked what happens to an arhat after death? This was one of the ten questions that the Buddha refused to discuss. Human language is designed to describe empirical objects. No word or sentence can capture meaningfully what happens to an arhat; however, this much is certain: Desires, passions, the feelings of “I” and “mine,” etc., which are rooted in egoism, are destroyed upon becoming an arhat. Nirvāṇa, the highest accomplishment of life in Buddhism, has been used by various religious groups as a generic term to refer to enlightenment. Nirvāṇa is freedom from dukkha, which encompasses within its fold grief, lamentation, pain, sorrow, sadness, despair, discontent, incompleteness, dissatisfaction, etc. 118 T H E BAU DDH A DA R ŚA NA Dukkha occurs due to desires, attachments, and cravings; the freedom of nirvāṇa is freedom from these attachments. Ignorance (avidyā), however, is the root cause of desire, attachments, and cravings, so the goal is to free oneself from ignorance. As soon as the hold of ignorance is broken, a person attains nirvāṇa. The fourth noble truth outlines the path to attaining nirvāṇa. The Noble Eightfold Path The Fourth Noble Truth lays down the Noble Eightfold Path for the attainment of nirvāṇa. The Noble Eightfold Path10 Śila, Wisdom 1 Right view Knowledge of the Four Noble truths and the Middle Way 2 Right intention Renunciation of worldly attachments, ill-will, and harming others, resolve to follow the path Śila, Ethical Practice 3 Right speech Abstaining from lying; being kind, open, and truthful 4 Right action Refraining from killing, stealing, lying, intoxication, and performing peaceful, honest, and pure actions 5 Right livelihood Freedom from hurt and danger to another human being Sam ādhi, Meditation 6 Right effort Effort to prevent unwholesome thoughts from arising, to renounce unwholesome thoughts, to develop and retain positive thoughts 7 Right mindfulness Having an active, watchful mind 8 Right concentration Meditating deeply on the realities of life The Noble Eightfold Path is usually divided into three groups: Sila, sam ādhi, and prajñ ā. (1) Śila consists of ethical practices: Right speech, right action, and right living. (2) Sam ādhi consists of different stages of meditation: Right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration. (3) Prajñ ā of knowledge and wisdom: Right view and right intention or resolve. The Buddha reiterated that these steps must be cultivated simultaneously and not successively because he believed that virtue and wisdom purify each other, and thus the two are inseparable. One begins with the right view, and 119 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S the remaining seven steps of the path are interdependent. Repeated contemplation, steadfast determination, and continuous effort (performing good deeds) habituate and train the will, giving rise to a personality in which one fnds a fne assimilation of pure will and emotion, reason and intuition, which is perfect insight, i.e., nirvāṇa. It is worth noting that the Noble Eightfold Path shares similarities with the practice described in Patañjali’s Yogas ūtras; the extent and signifcance of these similarities warrant a separate discussion. Although the Eightfold Path might be viewed as a kind of moral catechism or a list of negative injunctions (what to avoid), or as providing a list of virtues, a proper understanding of the path includes seeing how steadfastly following the integrated components of the path keep the practitioner along the Middle Way. The central question is how precisely to orient one’s life so that one is on the way to attaining nirvāṇa. For this purpose, the Buddha developed the eightfold path, and the major portion of the frst sermon is devoted to describing it. The Buddha repeatedly emphasized that one should pay close attention to how his actions affect those who are around them. Our actions should include the welfare of all, our own self, and the selves of others. Five wrong actions are specifcally mentioned in the Buddhist texts: Killing and hurting others, stealing, false speech, immoral sex life, and the consumption of alcoholic beverages. These are wrong because they cause harm to our own self and others. Abstaining from these fve wrong actions constitute the Five Buddhist Precepts. Five Buddhist Precepts11 1 2 3 4 5 I undertake the rule of training to refrain from killing or hurting living things. I undertake the rule of training to refrain from appropriating what belongs to others. I undertake the rule of training to refrain from falsehood. I undertake the rule of training for self-control. I undertake the rule of training to refrain from making myself a nuisance. It is not only by following the strict path of ethical self-control, avoiding extremes, and following the Middle Path but also by training one’s mind to focus exclusively upon the truth that one eventually attains wisdom and freedom from dukkha. The Four Noble Truths play an important role in the Buddha’s overall teachings. “All formations are subject to dukkha,” is one of the three characteristics of existence that form the foundation of his teachings. The other two characteristics are: “all formations are ‘non-eternal’ (anitya),12 and all things are ‘without a self’ (anatt ā).” 120 T H E BAU DDH A DA R ŚA NA The Buddhist concept of annicā or the law of impermanence or transiency of all things fnds classical expression in the famous formula “sabbe sa ṇkh ārā aniccā,”13 and in the more popular statement annicā vata sankh ārā. Both these formulas amount to saying that all conditioned things or processes are transient or impermanent. All conditioned things (sa ṅkh āra) are in a constant state of fux. Human life embodies this fux in the aging process, and the cycle of repeated birth and death (sa ṃsāra). Nothing lasts, and everything decays. There is no being; there is only ceaseless becoming. And what is impermanent is dukkha. III All Things are Impermanent (Anitya) “All is impermanent (sarvam anityam)” was one of the Buddha’s frequent utterances. All schools of Buddhism subscribe to the thesis of impermanence, though their interpretations vary. There are two aspects of it: Negative and positive. The negative thesis states that there is nothing permanent; everything is in perpetual fux. Due to the limitations of our sensory apparatus, we are not able to perceive change, though change is taking place all the time. Permanence, essence, unchanging substances, exist only in thought and not in reality. Regarding the positive thesis, there is no unanimity. One dominant version of the positive thesis asserts that everything is momentary. Such modern scholars as Kalupahana, who represent the Ceylonese Buddhism, argue that the Buddha himself only taught the doctrine of impermanence and that the “doctrine of moments” was “formulated from a logical analysis of the process of change” by the later Buddhists.14 The denial of permanence must be understood in the context of the important idea of the eternal self of the Upaniṣads. Rejecting the soul of the Upaniṣads, the Buddha held that there is nothing eternal, neither in the external world nor in the inner life of consciousness. Given that everything is conditional and relative, everything passes through the process of birth, growth, decay, and death. The search for permanence leads us in a false direction, and all false doctrines arise from the misconception that there are permanent essences. The Buddha’s goal was to demonstrate the all-pervasive nature of dukkha and show people how to alleviate it. He believed that craving for something or the other lasts forever, and the realization that everything is impermanent would lead to the pacifcation of cravings. Thus, the doctrine of impermanence is not only theoretically important, but it is also of considerable practical and spiritual importance. The idea of impermanence became the focus of Buddhism; however, from the exposition of the Sanskrit critical literature on Buddhism, we learn that on the Buddhist view, everything is also momentary. Whether this positive thesis correctly represents the earliest Buddhist view, is diffcult to ascertain. However, there is no doubt that many Buddhist philosophies, especially Tibetan and Chinese Buddhism, do in fact subscribe to the doctrine of momentariness. 121 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S The doctrine of momentariness states that things arise and then perish. Between the two, the arising and the perishing, there is only one moment of being, and, in the disputational literature, even this moment of being, which separates the arising from the perishing, came to be challenged. The thesis that things last only for a moment (leaving out the difficult question of what precisely is meant by a “moment”), is made to rest upon an argument that runs as follows: 1 2 3 4 5 6 To exist is to be causally efficacious. To be causally efficacious is to produce such effects as are possible. So, for an entity to exist is to produce such effects as it is capable of producing. But in producing these effects, all of an entity’s causal power is actualized. If all of an entity’s causal power is actualized, no more causal efficacy remains. If no more causal efficacy remains, the entity by definition would cease to exist. In this argument, in the first premise (to exist is to be causally efficacious), the definition of existence as causal efficacy is of central importance. According to this definition, nothing can exist for more than a moment, and the causal power that a thing has must be spent in the very first moment of its being. The Hindu writers who believed not only in the eternal soul but also things that may exist for a stretch of time, believed in the possibility that an entity’s entire causal efficacy is expended not at the very first moment of its being but over a stretch of time, implying thereby that while some power or efficacy is being actualized at the very first moment, some can remain potential. The Buddhists vehemently denied this. They argued that there is no “potential power,” but rather that every power that we can meaningfully talk about is the power that is actualized. Therefore, given the two assumptions that (1) to exist is to be causally efficacious, and (2) to have causal power is to produce all the effects an entity is capable of producing at the very first moment of its being, it follows that an entity can exist only for a moment. Later Buddhist writers carried this thesis to its logical consequence. Of the supposed three moments in the biography of an entity, arising → being → perishing, it is the second, i.e., being, can be eliminated, leaving only arisings and perishings, which is precisely the doctrine of momentariness carried to the logical end. Their zeal for taking thought to its furthest logical consequence did not stop even here. The Mahāyāna writers, following Nāgārjuna, argued that the moment of arising itself must arise and perish, and so also the moment of perishing so that there would be an arising of arising, a perishing of arising, an arising of perishing, and a perishing of perishing. Each of these again would lead to similar internal splits and we would find ourselves in a vicious infinite regress. The above led to the result that the doctrine of impermanence, 122 T H E BAU DDH A DA R ŚA NA even in its iteration as a doctrine of momentariness, is not a metaphysically true representation of reality; that like all representations, it is also śūnya or empty. Hence the conclusion of the doctrine of impermanence is the thesis of emptiness. In this brief account, I have tried to trace the development of the impermanence thesis from the early Therāvāda Buddhism to the Mahāyāna’s śūnyat ā (emptiness) thesis. It is always good to remember that the Buddhist philosophy has been a historically developing philosophy and it is always useful to trace the path that its history has traversed. I will revisit some of these issues in the chapter on the schools of Buddhist philosophy. It is not only that things are conditioned and impermanent, but human existence is also impermanent. Human life embodies this fux in the aging process and the cycle of repeated birth and death (sa ṃsāra). However, the Buddhists were frm in their denial of a permanent self or ātman that persists through and beyond this fux. IV All Elements of Being are No-Self (Anattā) As discussed earlier, the Upaniṣads postulate an identical ātman in all human beings and hold that an “I,” an individual self, is a combination of a body and a soul. The Buddha, in his sermons, gives a very different answer to the question: Who am I? The Buddha’s anatt ā (no-soul), is the opposite of the Hindu doctrine of att ā, that there is a permanent soul. The Five Skandhas 1 2 3 4 5 Bodily form Sensations Perceptions (recognition, understanding, and naming) Dispositions Consciousness The Buddha argued that there is no soul or ātman; a self is composed of fve skandhas: Bodily form (matter or body), sensations (feelings, sensations, etc., sense object contact, generating desire), perceptions (recognition, understanding, and naming), dispositions (impressions of karmas), and consciousness. These fve aggregates together are known as “n āma-r ūpa.” R ūpa signifes body, and n āma stands for various such processes as feelings, sensations, perceptions, ideas, and so on. These fve skandhas that constitute the self are themselves impermanent; so, they cannot give rise to a permanent self. The Buddha provided many similes to explain the arising of the self. One of his favorite examples was that of a chariot. A chariot is nothing more than an arrangement of the axle, wheels, pole, and other constituent parts in a certain 123 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S order, but when we take the constituents apart, there is no chariot. Similarly, “I” is nothing but an arrangement of fve skandhas in a certain order, but when we examine the skandhas one by one, we fnd that there is no permanent entity, there is no “I,” there is only a name (n āma) and a form (r ūpa).15 At this point, readers may wonder, if there is no permanent self, who or what is reborn? The Buddha uses the metaphor of the fame of a lamp to explain rebirth. He argues that life is a fame, and rebirth, is the transmission of the fame from one aggregate to another. If we light one candle from another, the communicated fame is one and the same, the candle, however, is not the same. Upon death, the union of the fve skandhas dissolves, but the momentum, the karmas of that former union, give rise to another union of fve skandhas. Accordingly, rebirth is the “endless transmission of such an impulse through an endless series of forms.” Nirvāṇa is the realization that the self is a union of fve impermanent skandhas that dissolve at death, and “that nothing is transmitted but an impulse, a vis a tergo, dependent on the heaping up of the past. It is a man’s character, and not himself, that goes on.”16 Any existent individual self is the karmic result of defnite antecedents. Rebirth is only a manifestation of cause and effect. Impressions of karmas generate life after life, and the nature and character of successive lives are determined by the goodness and badness of the actions performed previously. The Buddha’s rejection of an underlying permanent substance (soul) behind the ever-changing skandhas is not merely an intellectual analysis. The following points are worth noting: First, on the Buddha’s analysis, the denial of a permanent self or soul does not destroy the notion of an empirical self or personality. “Self” or “being” means a union of impermanent skandhas; when the skandhas dissolve, the self disappears and we have death. In so denying a ‘self,’ the Buddha deemphasized the ego-oriented framework of language; if there is no “I,” “you,” or “my,” then “I belong,” “I own,” etc., do not make much sense. Secondly, although the Buddha denied the existence of a soul, he argued for the continuity of the karmas. A self, argued the Buddha, is merely an aggregation of fve skandhas; so long as the karmas providing the momentum for aggregation remain the same, for all practical purposes we recognize a person as ‘the same.’ But these karmas are not restricted to one union; they pass on to others and remain in them even after one’s death. Thus, when one person dies, karmas give rise to another union of fve skandhas, and this process goes on until one attains nirvāṇa. Thirdly, the denial amounts to rejecting all principles of identity in favor of the idea of the difference. According to the att ā theory, everything in the world—not only a human being but also the mountain I see over there, this pen with which I write—has its own identity across time. A human being can be identifed, reidentifed, perceived, remembered, and referred to by such names as Bina Gupta, while perception and memory, and recognition guarantee us that this is the same Bina Gupta I encountered before. 124 T H E BAU DDH A DA R ŚA NA Buddhist philosophers consider this position to be naive, not only because it involves believing that names designate real things but also because it involves believing in the validity of perception, memory, and recognition. Once the referential theory of meaning is rejected and the ability of perception to convey its own validity is questioned, we then begin to see the plausibility of the Buddhist theory. Names do not simply name a thing, but they help to bring together many percepts under a common concept by virtue of their similarity; by this means they contribute to the construction of the world. The name “Bina Gupta” creates the impression that there is an identity between the person seen in Columbia twenty years ago, and the person seen in Philadelphia today. The differences between these percepts are being glossed over, aided by using the name. Likewise, when we consider the name “Ganges,” we must remember that the river Ganges in Patna and the Ganges near Vā r āṇasī are not the same Ganges. In the same sense that Heraclitus argued that we never step in the same river twice, the Buddha argued that the inner is actually a process of change, arrested by the use of a name. The rapidity of succession creates an illusion of identity; identity is only the continuity of becoming. Ignorance creates the false impression of identity; however, only becoming exists. It is important to remember in this context that things are really aggregates of parts, those parts again of other parts and that the last constituents are the momentary events that arise and perish. We do not perceive these momentary events and given that we do not perceive the constituent parts, we cannot claim to be perceiving the whole. Indeed, the Buddhist denies the thesis that there are genuine wholes that arise out of the combination of parts. It is the language that makes us believe that we perceive wholes even though we do not perceive their constituent parts. Thus, what we perceive is really a construct, and in this construction, language plays an important role. This chain of argument is designed to make us see that the alleged identical object is a construct out of differences that perpetually escape our grasp. Fourthly, it follows from everything that has been said so far that there is no universal (sām ānya) of which particulars are instantiations as Plato and Naiy āyikas would have it. Rather, a universal is constructed from particulars by virtue of their similarity aided by the use of language. Some Hindu metaphysical theorists, such as M ī māṃ s ā , believe that the word “cow” signifes “cowness”; alternately, on the Ny āya account, the word “cow” signifes a particular cow, as qualifed by the universal “cowness.” The Buddhists reject this theory of meaning and replace it with the apoha theory. In its simplest formulation, the apoha theory holds that the word “cow” does not signify “cowness,” but rather “not-non-cow.” This amounts to saying that one of the functions of language is exclusionary, that is, to indicate what a thing is not, emphasizing difference, rather than to indicate what it is, emphasizing identity. It is not necessary here to enter into the complicated and unending disputes between Hindu and Buddhist semantic theories; suffce it to note that 125 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S (1) Buddhist an ātm ā theory, (2) anti-essentialism, (3) anti-referentialism, and (4) prioritization of differences over identity, hang together. It is also worth noting that the Buddhist philosophers anticipated contemporary antiessentialism arguments and the prioritization of difference, which one fnds in the writings of such twentieth century philosophers as the French deconstructionist Derrida. Buddhism rejects both (1) Upani ṣ adic essentialism, which posits an enduring, substantial ātman shared by all human beings that persists through multiple reincarnations, and (2) traditional Christian accounts of unique individual souls that are incarnated only once. Buddhism affrms the self to be an epiphenomenon of the fve impermanent skandhas, which cannot, as such, give rise to a permanent self. An individual’s existence, his being, is in fact a becoming—it is an event, a process. Any account of this process mandates that there must be an adequate cause to explain it. The Buddha explains anatt ā in terms of the doctrine of karma, the doctrine of cause and effect. Thus, the Buddha favors a process philosophy, though the process with a structure. The Buddha’s doctrine of the twelve-membered chain of the Dependent Origination illustrates this process philosophy, which I will discuss next. V Dependent Origination (Pratītyasamutpāda) A common theme of all Buddhist philosophies is the doctrine of Dependent Origination. It is essentially the Buddhist doctrine of causality. Etymologically, “samutp āda” means, “arising in combination,” or “co-arising.” However, when prefxed with the term “prat ītya” (which means “moving” or “leaning”), the term implies “dependence.” Accordingly, “prat ītyasamutp āda,” has generally been translated as “Dependent Arising,” “Dependent Origination,” etc. In the Buddhist texts, the formula of Dependent Origination has often been expressed in the following words: “When this is, that comes to be; on the arising of that, this arises. When this is not, that is not; on the cessation of that, this ceases.”17 It means that, depending on the cause, the effect arises; when the cause ceases to exist, the effect also ceases to exist. Dukkha being a fact of existence must have a cause, and, when the cause of dukkha is removed, the dukkha also ceases to exist. The doctrine of Dependent Origination, essentially a doctrine of causality, includes within its fold such important interrelated notions as, ignorance, karma, moral responsibility, rebirth, craving, death, the nature of psychophysical personality, and consciousness. The Buddha detailed this doctrine in the context of explaining the doctrine of the Middle Way in the Discourse to K ātyāyana— On ignorance depends karma; On karma depends consciousness; 126 T H E BAU DDH A DA R ŚA NA On consciousness depend name and form; On name and form depend the six organs of sense; On the six organs of sense depends contact; On contact depends sensation; On sensation depends desire; On desire depends attachment; On attachment depends existence; On existence depends birth; On birth depend old age and death, sorrow, lamentation, misery, grief, and despair. Thus, this entire aggregation of misery arise.18 Given that everything arises depending on some conditions when these conditions and causes are removed, the effect is also removed. Again, in the Buddha’s words: But on the complete fading out and cessation of ignorance ceases karma; On the cessation of karma ceases consciousness; On the cessation of consciousness cease name and form; On the cessation of name and form cease the six organs of sense; On the cessation of the six organs of sense ceases contact; On the cessation of contact ceases sensation; On the cessation of sensation ceases desire; On the cessation of desire ceases attachment; On the cessation of attachment ceases existence; On the cessation of existence ceases birth; On the cessation of birth cease old age and death, sorrow, lamentation, misery, grief, and despair. Thus, does this entire aggregation of misery cease.19 There are twelve links in the causal chain of Dependent Origination. Because of (1) ignorance (avidy ā ), an individual accumulates (2) impressions of karmas, which are responsible for bringing about the renewal of the present embodiment. (3) A vague consciousness provides the link between the past and the present embodiment; the nature of this consciousness depends on the actions and desires of the previous embodiments. Gradually, (4) the embryonic consciousness assumes a psychophysical form, develops (5) sense organs, and (6) contact of the sense organs with sense objects results in (7) all sorts of pleasant and unpleasant experiences. An individual thus (8) craves pleasant experiences and tries to avoid unpleasant ones, and (9) clings to the idea of permanence. Consequently, (10) a desire to be born again is created, resulting in (11) birth and (12) death. It is worth noting that each of these twelve factors is both conditioned and that which conditions. Thus, the psychophysical form one assumes is conditioned not only by what one experiences in this life but also by the way 127 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S The Twelve Links of the Causal Chain of Dependent Origination Passive Active Past 1 Ignorance (avidyā) 2 Karmas Present 3. Initial consciousness 4 Psycho-physical organism 5 Sense organs 6 Sense object contact 7 Sensory experience 8 Craving (t ṛṣṇā) 9 Clinging 10 Becoming Future 11 Birth 12 Death in which one responds to these experiences. Links (1)–(7), existing in the relative past and present, are passive insofar as no one can control them because they are the result of past actions. But from the eighth link (thirst, desire) to the tenth moral will plays an important role. Although the normal response to a pleasant experience is to cling to it and try to prolong it, one can through moral will proceed in the opposite direction, and there will be neither clinging nor grasping. If one realizes that pleasurable experiences are temporary and controls his cravings, desires, etc., he will begin to have a better understanding of his own personality and the world that surrounds him, leading him to wisdom. On the other hand, if one’s actions are the result of cravings and clinging to pleasurable experiences, then the desire to be, to continue, will be created, thereby giving rise to another collection of name and form—to be born, live, and die again and again. Thus, thirst, clinging, and becoming are the most important active components of the twelve links of the wheel of Dependent Origination. The doctrine of Dependent Origination is the foundation of the Buddha’s teachings. It explains the nature of sa ṃsāra, the world where dukkha is manifested, and points to the relativity of all things. In the empirical world, everything is relative, dependent, and accordingly, subject to decay and death. In order to understand the originality of this view, we should bear in mind several features of this doctrine: First, Buddhism affrms that an effect arises when all the causal conditions are present; it is constantly a new beginning, and in so asserting, the Buddha rejects both varieties of satk āryavāda and asatk āryavāda.20 Note that the Buddhist is not thinking of a distinct event called “cause” and another event called “effect.” Causality is not a relation between two events but a 128 T H E BAU DDH A DA R ŚA NA relation between many preceding events, all of which lead to the arising of the succeeding event. The succeeding event arises or comes into being when all the causal conditions are present. Let me explain with the help of an example: What precisely produces a visual perception? For the Buddhist, it includes a properly functioning visual sense organ, a visually perceptible object out there, auxiliary light, such conditions as the contact of the visual organ with the object, the previous perceptions, and their impressions. The twelve-membered chain of human life gives a picture of a similar chain of causation which binds the arising of one life, of the embodied consciousness, to previous lives. Secondly, the doctrine of Dependent Origination covers the three dimensions of time; it makes a person in the present life a result of the past and a cause of the future. The wheel of Dependent Origination operates without any brahman, lawgiver, or God. There is no frst cause, no absolute beginning; each cause is an effect of the preceding causes and gives rise to the succeeding ones. This view postulates neither predeterminism nor complete freedom; it instead affrms an interdependence of conditions, some of which are within a person’s control. In the fnal analysis, we are responsible for who we are and what we become. The cycle does not end with death; death is only the beginning of another life. It is a circular chain; the twelfth link is joined to the frst one. One may begin with the twelfth link, and ask: Why do we suffer old age and death? Because we are born. Why are we born? Because there is a will to be born. Why is there a will to be born? Because we cling to the objects of the world. Why do we cling to the objects of the world? Because of the craving to enjoy the objects of the world. Why do we crave? Because of sense-experience. Why sense-experience? Because of sense-object contact. Why sense-object contact? Because of sense organs. Why sense organs? Because of psychophysical organism. Why psychophysical organism? Because of initial consciousness of the embryo. Why initial consciousness of the embryo? Because of karmas. Why karmas? Because of ignorance. 129 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S Thus, ignorance is the root cause of dukkha. Impressions of karmas give rise to an unending series of physical and mental formations until ignorance is destroyed. Everything depends on to what degree the cravings are brought under control. Until the impressions of the karmas are completely rooted out, fresh sprouting of the physical and mental formations is generated; the cycle comes to a stop when the impressions are destroyed by the right knowledge. It is easy to see that this understanding of the chain of causation can only be provisional. For once one rejects the simple linear chain of cause and effect—that is, “one cause, one effect”—then one cannot remain satisfied with its expansion to say, four causes and one effect. In other words, one cannot stop short of saying that an effect arises not only depending upon the conditions of one body, mind, and society but also on the entire nature of the material world and the totality of the universe. On this view, which is shared by many schools of Mah ā y ā na, especially Zen Buddhism, I am not an identifiable entity standing apart from the universe, not an individual in the modern Western Cartesian sense of the ego, but a process upon which all nature and all other humans and living beings are having an impact. Thus, while the understanding and formulation of the doctrine of Dependent Origination begin with the rejection of a linear chain of causation, one cannot but expand it to the point where one begins to see that every change in the universe depends upon everything else. The only way to get out of it is by attaining nirvāṇa. VI Nirvāṇa It might be obvious that the view of Dependent Origination found in Zen Buddhism completely transforms the way one understands the concept of “nirvāṇa.” Without a doubt, the idea of nirvāṇa is the culmination of Buddhist philosophy, just as attaining nirvāṇa is the goal pursued by the Buddhist aspirant. But what precisely is nirvāṇa and how to understand it? If we take the earliest reading of the Buddha, the word “nirvāṇa” conceals a metaphor, viz., that of blowing out a lamp as if by a gust of wind; it is the complete overcoming of dukkha. Questions about nirvāṇa have played an important role in the history of Buddhist philosophy. Some of these questions are: 1 2 3 Is nirvāṇa a negative state of cessation of pain or a positive state of bliss? Or, is it something that cannot be described by either term? Is nirvāṇa a state that one attains, or arrives at, at the conclusion of a process? Is it brought about or is it eternally present? If the latter, how can there be an eternal nirvāṇa given the doctrine of impermanence? Is the distinction between sa ṃsāra and nirvāṇa a distinction between two mutually exclusive realms, such that the Buddha upon attaining nirvāṇa left sa ṃsāra? 130 T H E BAU DDH A DA R ŚA NA 4 Is the pursuit of nirvāṇa not a selfsh pursuit? To put it differently, is the expression “my nirvāṇa” a coherent notion? Can there be nirvāṇa for one person before everyone else attains it? I think answering these questions, or at least trying to understand the aporia articulated in them, would lead to a better and deeper understanding of the concept of “nirvāṇa.” Given space limitations, it is not possible to discuss these questions in detail. For our purposes, the following should suffce. In early Buddhism, at least in some of the schools, such as the Sautrāntika, nirvāṇa was construed in purely negative terms as a complete cessation of suffering. But gradually this negative conception of nirvāṇa was replaced by a more positive understanding, according to which the cessation of dukkha brings about the complete transformation of existence, not its extinction. The Buddhists still hesitated to say that nirvāṇa is a state of bliss. Understandings and interpretations of nirvāṇa continued to change, culminating in Nāgārjuna’s statement that nirvāṇa and sa ṃsāra are the same, that they are two sides of the same coin—a statement that has both puzzled and inspired Nāgārjuna scholars since. What did he mean by it? Nirvāṇa is a mode of existence that one attains when one experiences the truth of sa ṃsāra. The picture that one must transcend sa ṃsāra before reaching nirvāṇa is misleading and wrong. If suffering is due to cravings, and cravings are due to avidyā (ignorance) reinforcing the illusion of permanence and eternity, then nirvāṇa is the realization of the truth of impermanence. The idea of permanence, as stated earlier, is due to the way conceptual thinking embodied in language constructs the world. The path to nirvāṇa would be the path of seeking complete deconceptualization, freeing oneself from the way our view of the world is bewitched by language, and getting rid of all metaphysical representations of reality. The world remains what it is; only now, it experienced in its truth, and that is nirvāṇa. Ignorance makes us ascribe identity and permanence not only to the self but also to objects in this empirical world. This ignorance is dispelled by the right view that neither the self nor the things in the world are permanent; they are impermanent aggregates or processes, bound together by the chain of causation. When we see the truth of things, we realize that there is no enduring self, no permanent things in the world. This realization results in a kind of desirelessness (because who will desire what?), with no cravings; there is no pleasure and pain, and so no suffering. This freedom is called “nirvāṇa.” Nirvāṇa stops rebirth by breaking the causal chain of Dependent Origination. It is not the result of a process; it is not brought about by anything. Nirvāṇa— truth—simply is. Buddhist thinking began with the idea of individual nirvāṇa. In Therāvāda Buddhism, an individual who attains nirvāṇa becomes an arhat. Mahāyāna replaces this idea with that of the bodhisattva, who after attaining nirvāṇa, helps others to attain it too. A bodhisattva recognizes that their own nirvāṇa is a lesser or minor nirvāṇa, only completed by nirvāṇa for all. 131 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S Bodhisattva (A Buddha-to-be) • • • Bodhisattva literally means an “enlightenment being,” a future Buddha, one who has postponed their own nirvāṇa to help others attain nirvāṇa. In early Pā li literature, the designation “Bodhisattva” was used only to identify Siddhārtha Gautama (the historical Buddha), and only future Buddhas merited this title prior to their enlightenment. In Mahāyāna Buddhism, this term came to signify an enlightened being who, though standing at the door of nirvāṇa, defers his own nirvāṇa to help others attain it. Scholars at times argue that nirvāṇa is the Buddhist counterpart of the Hindu mok ṣa. It is true that the Buddha used a new word for a concept that was in a certain sense already existed in the Upaniṣads and so already in the brāhma ṇic culture. Nobody would disagree that nirvāṇa and mok ṣa are the highest goals of life in Buddhism and the brāhma ṇic traditions, respectively. “Nirvāṇa,” however, is not simply a new designation; the concept itself is markedly different from the Hindu mok ṣa, especially when nirvāṇa is taken literally as “ceasing to be” or “extinction.” The Hindu philosophers—except for the Vaiśeṣika21—describe mok ṣa, as a state of bliss. The Buddhist philosophers, over the centuries, have differed considerably in their understanding of nirvāṇa. While always denoting “extinction,” the object of extinction is not the individual, but his selfsh desires, cravings, and subsequently, the extinction of continued rebirth. It is important to remember in this connection that neither the Buddhist nirvāṇa nor the Hindu mok ṣa is “caused” (for whatever is caused, ceases to be); both are called “unconditioned,” both are beyond time, and both are “supersensible.” For the Buddhists and the Hindus alike, ignorance leads to birth after birth. The goal is to free oneself from the clutches of karma and sa ṃsāra, and this freedom is found—not brought about—by knowledge of the true nature of the self and the world. In this sense, everyone is already potentially free, although realizing this freedom requires effort, practice, meditation, and refective knowledge. Though the Buddha rules out excessive self-mortifcation as well as extreme asceticism and endorses us to follow the Middle Way, some forms of renunciation, such as renunciation of family and social attachments, and some forms of asceticism have been recommended. All excesses of behavior are ruled out; the moderate practice of some austerity and asceticism is part of training and discipline. The followers of the Buddha used to wear a simple dress and wear robes of the cheapest cotton. Asceticism is detachment from the things that distract our desires. 132 T H E BAU DDH A DA R ŚA NA Let me conclude with the following note: Both the Hindu and Buddhist traditions recognize that weakness of the will causes human beings to act according to their passions and desires. A famous Sanskrit prayer sums up this point beautifully: “ jān āmi dharmam na ca me pravṛtti, jān āmi adharmam na ca me nivṛtti,” which means “I know what is dharma, but cannot will to do it, I know what is adharma but cannot will to desist from it.” Then the prayer continues: “tvayā hṛṣike śa hṛdisthitena, yath ā niyukto’smi tath ā karomi,” which means, “as you, O’ K ṛṣṇa who resides in my heart, incite me, I will act accordingly.” In other words, it emphasizes that moral will, operating through its own efforts, comes to a point when it surrenders its autonomy to divine guidance. This last point, of course, does not hold good of the teachings of the Buddha, because there is no God to which to surrender. Thus, the Buddhist has no choice but to rely on his own efforts in exercising moral will and freedom. In the Western tradition, Aristotle, and Augustine emphasized the importance of free will; however, in their philosophies, freedom is the freedom to choose. The Indian tradition has focused upon the idea of freedom from—while differing among themselves as to what it is one seeks to be free from, and the means by which such freedom is achieved. Both the Hindus and the Buddhists understood true freedom as freedom from pain and suffering. Since suffering is due to desire and craving and the latter is due to ignorance, freedom in the strict sense is freedom from ignorance (avidyā). Study Questions 1. Outline the central theses of Buddhism. Was Buddhism an entirely new philosophy, or did it appropriate any teachings of Hinduism and gave them a new interpretation? 2. Explain the Buddha’s Doctrine of the Middle Way. 3. What is dukkha? Analyze the Buddha’s Doctrine of the Four Noble Truths. To what extent do you feel Buddha’s evaluation of the nature of the human predicament (that all life is “suffering”) and his solution to it is valid or invalid? Answer in detail. If you believe that life involves a lot of “suffering,” to what extent do you feel we in the West attempt to overcome it and how? How does your approach to the problem differ from that of the Buddha’s and which one do you fnd more persuasive and why? 4. Buddha states, “the cause of dukkha is ta ṇh ā (craving).” Discuss the meaning and signifcance of the above statement in light of the Buddhist doctrine of Dependent Origination. Be sure to include in your answer an analysis of the twelve links in the wheel of moral causation. 5. Explain the Buddha’s Doctrines of impermanence and anatt ā. Is nirvāṇa compatible with the Buddhist doctrines of impermanence and anatt ā. 6. Compare and contrast the Hindu mok ṣa and the Buddhist nirvāṇa. 7. You have completed your reading of the three non-Vedic darśanas. The questions raised below concern these darśanas. 133 N O N -V E D I C D A R Ś A N A S A Sample Case: A Tenant’s Appeal to the Landlord Not to Evict Him • Suppose you are a landlord. One of your best tenants has been laid off from his job due to COVID-19, and he is not able to pay rent. You have the legal right to evict him; you choose to do so. What would the following individuals say of your decision to evict your tenant? • Based on your reading of the C ārvā ka school, do you believe a Cārvā kan (materialist) would agree with your decision? If so, why? If not, why not? Clearly explain the criterion a C ārvā kan would use to agree or disagree and include in your answer a discussion of some of the C ārvā kan theses, viz., hedonism, rejection of inference, account of consciousness, and so on. • Based on your reading of Jainism, do you think a Jaina would agree with your decision? If so, why? If not, why not? Clearly explain the criterion a Jaina would use to agree or disagree, and include in your answer a discussion of the Jaina, non-absolutism, ethics of non-violence, etc. • Finally, do you think the Buddha would agree with your decision? If so, why? If not, why not? Clearly explain the criterion the Buddha would use to agree or disagree, and include in your answer a discussion of some of the Buddhist concepts, viz., dukkha, the Four Noble Truths, aniccā, anatt ā, nirvāṇa, etc. • Conclude your answer with a discussion of why you believe your action as a landlord to be morally right. Philosophy is about critical thinking. It is important that you substantiate your position with rational arguments. Suggested Readings For the basic concepts of Buddhism, e.g., dukkha, aniccā, anatt ā, nirvāṇa, and the doctrine of Dependent Origination, see, Walpola Rahula, What the Buddha Taught (New York: Grove Press, latest), T. W. Rhys Davids, The History and Literature of Buddhism (Vārāṇasī: Bharatiya Publishing House 1975), and Mark Siderits, Buddhism as philosophy: An introduction (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett, 2007). David Burton, Buddhism, Knowledge, and Liberation (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004) contains a detailed analysis of the mutual relationship among the eight steps of the Noble Eightfold Path. O. H. de A. Wijesekra, The Three Signata (Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society, 1960), contains an excellent analysis of aniccā, dukkha, and anatt ā. For the Buddha’s life, enlightenment, and causation, see A. K. Warder, Indian Buddhism (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1970), Chapters 3–5. 134 Part V THE ANCIENT DAR Ś ANAS The Mīmāṃsā Darśana The Sāṁ khya Darśana The Yoga Darśana The Vaiśeṣika Darśana The Nyāya Darśana 8 THE M Ī M ĀṂ S Ā DAR Ś A NA I Introduction Originating in the attempt to understand and systematize the ritualistic part of the Vedas, i.e., the “brāhma ṇas,” the M īmāṃsā retained its position (which it had in antiquity) as the champion of the Vedic orthodoxy. As a philosophy, it developed into an analytical hermeneutical school, focusing primarily on a theory of action, especially the supersensuous nature of ritualistic actions and experiences, and a theory of the interpretation of the Vedic texts. In some respects, it remained an analytic philosophy (āṇvīk ṣik ī ), and, in other respects, it was a spiritualistic philosophy. Etymologically “mīm āṃsā” means “solution of a problem by critical examination,” “refection,” and “critical investigation”; it represents a school or tradition of inquiry or investigation into the meanings of Vedic texts. The Vedas, the foundational texts of Indian philosophy, have been classifed into karma k āṇḍa (the ritualistic portion emphasizing actions) and jñāna k āṇḍa (the portion of knowledge). M īmāṃsā focuses on the earlier portion of the Vedas, viz., karma k āṇḍa, i.e., on liturgy, the ritualistic actions; so, it is also known as “P ū rva M īmāṃsā” (p ūrva = previous) or Karma M īmāṃsā. Vedanta investigates the later portion, viz., jñāna k āṇḍa, i.e., the portion emphasizing the knowledge of the ātman and the brahman with its focus on Oneness, the central concern of the Upaniṣadic seers. So, Vedānta is also known as “Uttara M īm āṃsā” (Uttara = posterior or higher investigation). Eventually, P ū rva M īmāṃsā came to be known simply as “M īmāṃsā,” and the “Uttara M īmāṃsā” simply as Vedānta. Jaimini’s s ūtras, known as M īm āṃsās ūtras (400 BCE), is the basic text of this school. Śabara (CE 200) wrote a commentary (bh āṣya) on it. Two important commentaries on Śabara’s bh āṣya are: Kumārila’s Ślokavārtika (SLV) and Prabhā kara’s B ṛhat ῑ. Kumārila and Prabhā kara (nicknamed “Guru”) are the founders of the two schools of M īmāṃsā and the schools are named after them, viz., Bhāṭṭ a M īmāṃsā and Prābhā kara M īmāṃsā respectively. According to many accounts, Prabhā kara was a student of Kumārila and disagreed with him on many important points. Ma ṇḍ ana Miśra, the author of several important works on M īmāṃsā, was Kumārila’s student. Eventually, Śa ṃ kara initiated Ma ṇḍ ana into Advaita Vedānta. 137 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS Murāri Miśra is the third commentator of Jaimini. Murāri’s works are not available, and a few that are available are not in print. Other important expository works of this school are: Śāstrad īpik ā (SD) of Pārthasārathi Miśra (thirteenth to fourteenth CE), M īm āṃsānyāyaprak āśa of Apadeva (thirteenth CE) and Arthsa ṇgraha of Laug āṣksi Bhā skara (sixteenth CE). The central theme of M ī m āṃ s ā is dharma (at the very outset Jaimini informs his readers, “now begins an inquiry into dharma”),1 and the hermeneutics of the Vedas. What followed were attempts to defne dharma. Dharma is that which is indicated by the sentences of certain forms, i.e., “should-sentences,” known as “codan ā.” These sentences refer to the relevant Vedic discourse assuming the form “one should perform such and such actions.” The goal of M ī m āṃ s ā is to lead us to a precise determination of the Vedic discourse, in order that practitioners may lead a life of dharma. The school is also known as Dharma M īm āṃs ā. It focuses upon the Fundamental Postulates 1 Dharma is the governing force of the universe. 2 There are six pram āṇas: Pratyak ṣa (perception), anum āna (inference), śabda (testimony), upam āna (comparison), arth āpatti (postulation), and anupalabdhi (non-cognition). Prabhā kara does not accept anupalabdhi. 3 There are innumerable real souls, atoms, and substances. 4 The Vedas are eternal and authorless. 5 The soul is an eternal substance; consciousness is not an essential quality of the soul. 6 All knowledge is inherently valid. 7 Error: a b Prabhā kara’s hold there is no false or invalid knowledge. One does not perceive the silver; one simply remembers it (akhyāti). Bhāṭṭ as error consists in relating two existent but separate things in the subject–predicate relation. Error is due to wrong relationship (vipar ītakhyāti). 8 The relation between a word and its meaning is “natural,” and “eternal,” i.e., it is not brought about by any human agency. 9 Ap ūrva, i.e., unperceived potency, is a necessary causal link between the ritualistic actions done and their fruits. 10 Actions done with a desire to reap the fruits cause repeated births. 11 Liberation is a state of freedom from pain and desires. 138 THE MĪMĀṂSĀ DARŚANA rules for interpreting scriptures as a body of injunctions rather than as religious statements about god, soul, and the world. Its goal was (a) to supply a philosophical justifcation of the beliefs underlying numerous rituals; (b) to interpret very complex and subtle ritualistic injunctions to maintain order in the universe, and (c) to promote the personal well-being of the person performing the ritual. Not having any theoretic use of the idea of god, M ī m āṃ s ā explains the Vedic deities as posits implied by the performance of rituals and concerns itself with the motivation for such actions, e.g., the promised “other-worldly” consequences and their place in the ethical life of a community. The Vedic texts are exceedingly obscure and replete with apparent inconsistencies. To resolve these inconsistencies, M ī m āṃ s ā classifed various texts, formulated the rules of interpretation, and focused its energy on bringing out the precise meanings of words and sentences. It went on to develop a rich philosophy not only of language but also of action. Ultimately it developed into an analytical-cum-hermeneutical philosophical dar śana. In expounding such a system as P ū rva-M īmāṃsā, it is imperative that we separate the ritualistic aspects of this school from the strictly philosophical ones. The key philosophical ideas include the M īmāṃsā theory of knowledge, truth, and language. On all these counts, M īmāṃsā commentators made important contributions thereby providing the impetus for further discussions. In this chapter, I will primarily focus on M īmāṃsā epistemology. I will discuss key epistemological conceptions highlighting, where necessary, the differences between the Bhāṭṭ a and the Prābhā kara schools. There are fve additional sections: (II) The Nature and the Sources of Knowledge, (III) The Self-Validity of Knowledge, (IV) Error or the Falsity of Knowledge, (V) The Theory of the Meaning of Words and Sentences, and (VI) Self, Dharma, Karma, and Mok ṣa. II The Nature and the Sources of Knowledge In the feld of epistemology, M īmāṃsā made signifcant contributions.2 M īmāṃsā, like most schools of Indian philosophy, recognized both immediate and mediate knowledge. According to Kumārila, pram ā is a valid cognition that presents an object previously unknown, not contradicted by subsequent knowledge, and not generated by a defective condition. The object of immediate knowledge must be existent, and when such an object is related to a sense organ (internal or external), there arises an immediate knowledge of it. A pram āṇa is the effcient cause of a cognition. Kumārila, like Advaita Vedānta and unlike Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika, recognizes six pram āṇas: Pratyak ṣa (perception), anum āna (inference), upam āna (comparison), śabda (testimony), arth āpatti (postulation), and anupalabdhi (non-cognition or absence). Prabhā kara accepts 139 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS only the frst fve; he rejects non-cognition as an independent knowable category.3 Absence, argues Prabhā kara, is not a positive entity; it is known through inference. When I do not see an elephant in a room, from my non-perception of the elephant in the room I infer that there is no elephant in the room. So, there is no need of anupalabdhi to establish the cognition of absence. Of the six pram āṇas, the M īmāṃsā argues that perception is immediate and the remaining fve are mediate.4 Pratyak ṣa (Perception) Perception is a cognition produced by the contact of the sense organ with the mind, of the mind with the sense organ, and the sense organ with the object.5 Both Kumārila and Prabhā kara admit two stages of perception.6 When there is a contact of the sense organ with the object, initially we have a bare awareness of it; we know that the object is, but we do not know what it is. In this cognition, neither the genus nor the differentia is presented to consciousness. This primary immediate knowledge is nirvikalpaka perception.7 At the next stage, i.e., the stage of savikalpaka perception, we come to know the object in light of our past experiences, understand it as belonging to a class, possessing certain qualities, and having a name. It is expressed in such judgments as “this is a chair,” “this is a table,” etc.8 Anum āna (Inference) Etymologically “anum āna” means the knowledge that “follows another knowledge.” M īmāṃsā defnes inference as the knowledge in which one term of the relationship—which is not perceived—is known through the knowledge of the other term that is invariably related to the frst term. In other words, in an inference, based on what is perceived we are led to the knowledge of what is not perceived because the perceived and the inferred have a permanent, unfailing relationship.9 The Bhāṭṭ as defne invariable concomitance (vyāpti) as a “natural relation,” and “natural” here means being free from any limiting conditions. In the inferential knowledge the “hill is fery,” we observe cases where smoke and fre are present together, and cases where they are not so present and arrive at a general principle that governs all cases. Unlike the Naiyā ikas who argue that an inferential argument has fve members, both Kumārila and Prabhā kara hold that an inferential argument has three members. Both make a distinction between the inference for oneself and inference for others. However, there is an important difference between Prabhā kara and Kumārila: Prabhā kara argues that the inference of fre on a hill does not present anything previously unknown, because the inference “the hill is fery” is already included in the major premise “all cases of smoke are cases of fre.” Kumārila argues that the previous unknownness or novelty is an essential feature of inference, because though we know that smoke is invariably related to fre, this hill as possessing the fre was not known earlier.10 140 THE MĪMĀṂSĀ DARŚANA Upam āna (Comparison)11 Knowledge from comparison arises when upon perceiving an object that is present before me, which is like an object that I have perceived in the past, I come to know that the remembered object is like the perceived one.12 This is knowledge by similarity. I see an animal gavaya that is like my cow and say “my cow is similar to this gavaya.” Knowledge obtained through comparison cannot be reduced to perception, inference, and testimony; it is not perception, because the object “my cow” is not perceived now; it is not an inference because the knowledge is not derived from a vyāpti or universal concomitance; and fnally, it is not knowledge by testimony because the knowledge does not arise from the testimony of another person. Śabda (Testimony) Among the pram āṇas, M īmāṁsakas discuss śabda in detail because of their interest in the authority of the Vedas.13 This is the knowledge that arises from the testimony of a reliable person; it may be of two kinds: Personal (non-Vedic) and impersonal (Vedic). The frst denotes either the heard or the written testimony of a person, the second the authority of the Vedas. The former testimony is reliable except when it is known from an unreliable person. The Vedic śabda again may be of two types: They may either provide information regarding the existence of objects, or give injunctions regarding the performance of some actions, sacrifcial rites, and rituals. The Vedic śabda produces a cognition of an object that does not have any contact with the sense organs; the cognition arises based on the śabda alone. Kumārila accepts both personal and impersonal śabda, but Prabhā kara does not accept the authority of the non-Vedic śabda. M īmāṃsakas were primarily interested in dharma, because it is dharma (ethical force, power) that controls and governs the universe and the agent. Their primary goal was to determine the nature of dharma; specifcally, dharma as taught by the Vedic injunctive sentences. They took existential statements regarding immortality, god, soul, etc., of the Vedas to be subsidiary to the injunctions. The injunctions are valid in themselves; they do not derive their validity from any other source. For M īmāṃsakas, the value and the sole use of the Vedas lie in giving directions for performing rituals, the remaining parts of the Vedas are of no value.14 The Vedas, like words, are eternal.15 They do not have either personal or divine origin.16 The question is: Are not the Vedas composed of non-eternal words? The M īmāṃsakas in response state that words are not really the perceived sounds; they rather are uncaused and partless letters. For example, a letter, say, “s,” is uttered by many individuals at different times and in many ways. The sound differs, but we recognize the letter to be the same. Words as letters are eternal entities, and the relation between words and their meaning is natural. I will discuss some of these issues in Section V of this chapter. 141 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS Arth āpatti (Postulation or Presumption)17 Arth āpatti is “the presumption of something not seen on the ground that a fact already perceived or heard would not be possible without that presumption….”18 In postulation, one presumes an unperceived fact which alone can explain a fact.19 A man fasts during the day but still gains weight and becomes fat. There is an apparent contradiction between his increasing fatness and his fasting, barring some medical explanations. To reconcile the contradiction, we say that the man must be eating at night. Knowledge obtained from arth āpatti cannot be reduced to perception, inference, and comparison; it is not perception since we do not see the person eating at night; the knowledge is not derived based on an invariable relation between fatness and eating; and it is not obtained from the testimony of a person. Anupalabdhi (Non-perception)20 Non-perception is the immediate cognition of the non-existence of an object. The question is: How do I know the non-existence, say, of an elephant in my room? It cannot be perceived in the manner I perceive an object that I see before me. The Bhāṭṭ as, like the Advaitins, argue that the non-existence of an elephant in the room is known from the absence of its cognition, that is, from the non-perception of the elephant. This non-existence cannot be known by inference, because if we already had the knowledge of an invariable relation between the non-perception and non-existence, i.e., if we had already known that the non-perception of an object implies its non-existence, then we would be begging the question and there would be no need to prove the non-existence by inference. We cannot explain the elephant’s non-existence by comparison or testimony as the knowledge of the similarity or the words of a reliable person. Therefore, we must recognize non-perception (anupalabdhi) as an independent pram āṇa. As is obvious from the above paragraphs, M īmāṃsā, like most schools of Indian philosophy, developed its conceptions of pram ā and pram āṇas. However, they were the frst to develop a theory of the intrinsicality and extrinsicality of knowledge, which I will discuss next. III The Self-Validity of Knowledge The M īmāṃsakas, like the Advaita Vedāntins, argue that all knowledge is intrinsically valid because validity arises from the very conditions that cause it.21 On the M īmāṃsā theory, knowledge is about its object and it is true of its object; so, it is pram ā. Whenever adequate conditions for the arising of a specifc knowledge exist, the knowledge arises without any doubt or disbelief in it. For example, in the daylight when our eyes meet an object, we have a visual perception of it. Based on the universal concomitance, we infer fre upon perceiving smoke. When one hears a meaningful sentence from one’s 142 THE MĪMĀṂSĀ DARŚANA friend, knowledge arises from testimony. In our daily lives, we act on such knowledge without worrying about its truth and falsity, and the fact that it leads to successful activity testifes that such a cognition is true. The invalidity of a cognition is arrived at by external means, especially by appealing to subsequent cognitions. When the conditions are defective—e.g., when the eyes are jaundiced, or there is a lack of light—no such knowledge arises. Invalidity or falsity thus arises from subsequent experiences or some other data. When a cognition arises, its validity “immediately arises” and cannot be doubted.22 Thus, to say that a cognition is not true of its object is absurd. A cognition does not need any special or additional excellence in the cause for it to be true. If the cause of a cognition does not produce it, then no additional factor added to the cause can produce it. Thus, once the cause of a cognition produces the cognition, this cognition by its very defnition will let the knower be cognizant of its object and therefore true. As knowledge is already true, any further determination of the absence of any defect in the causal conditions cannot make the original cognition true. Determination of the absence of any defect only strengthens the certainty of truth. In this chain of argument, the emphasis is on the proper object of a cognition. The object of a cognition is only that which is manifested in that cognition and not something else. What is not manifested in a cognition cannot be the object of that cognition. So, the M īmāṃsakas argue that the validity of cognition (a) arises from the very conditions that generate it, not from any extrinsic conditions, and (b) it is believed to be true as soon as it arises; it does not require any additional verifcation by other pram āṇas, say, an inference.23 These two aspects taken together constitute the M īmāṃsā theory of intrinsic validity, i.e., cognitions are valid in themselves and do not need further proof to validate them. In other words, in the context of the truth or the validity of cognitions, the question is: Is the truth of a cognition intrinsic or extrinsic to the cognition?24 Most Indian philosophers raised the same question about falsity. Those who answer this question in the affrmative, e.g., M īmāṃsā and Advaita Vedānta, are known as the svataḥ prām āṇyavādins, the upholders of the theory of the intrinsicality of truth. Those who answer this question in the negative, e.g., the Naiyāyikas, are known as the parataḥ prām āṇyavādins, the upholder of the theory of the extrinsicality of truth. Two important questions arise in this context: First, do the conditions which produce a cognition also make it true? Second, is it the case that when a cognition is known to me, it is also at the same time known to be true?25 This doctrine of the intrinsic validity of all knowledge is one of the most important doctrines of the M īmāṃsā school. In concrete terms, to say that a cognition is intrinsically valid because its validity arises from those very causes from which the cognition itself arises and not from any extraneous conditions and it is known to be valid as soon as it arises,26 amounts to saying truth is self-evident and whenever any knowledge arises, it carries with it an assurance, a sort of “guarantee” about its truth, and retains its validity until it 143 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS is shown to be otherwise, say, on account of some defective conditions or from a subsequent cognition that contradicts the initial cognition. A person suffering from jaundice sees a white shirt as yellow, and implicitly believes that it is yellow. The judgment, in this case, is mistaken which is learned subsequently, by inference, or another compelling evidence. Though both Prabhā kara and Kumārila subscribe to the view that cognitions are intrinsically valid, there is an important difference between the two and the difference concerns the question: How is a cognition cognized?27 Prabhā kara holds that a cognition is perceived directly along with the object and the knowing self (articulated in the sentence “I know this pitcher”). Prabhā kara accepts tripuṭῑvṛtti, i.e., the three-fold presentation. Each cognition has three factors, the “I” (the subject or the knower), the known (the object), and the knowledge itself. In the cognition, “I know the pitcher”—the “I,” the pitcher, and the awareness—all three are at once presented (tripuṭῑpratyak ṣavāda), and each is perceived in its own way: The “I” is cognized as the “I” (not as the object), the pitcher as the object, and the cognition as a cognition (i.e., as neither the subject nor the object). According to Prabhā kara, when we know, we also know that we know; the knowledge is self-revealing. Kumārila argues that knowledge by itself cannot be the object of itself. He argues that cognition is known by inference from a new property called “knownness” that is produced in the object when it is known. For Kumārila, knowledge is a process, an activity of the self. This process generates a property known as manifestedness in the object. A cognition is not perceived directly; it is inferred from the manifestedness ( jñ ātat ā) that is produced in the object. His theory is known as jñ ātat āvāda. Kumārila denies self-luminosity to knowledge. The question is: Is the pram ātva of a cognition apprehended svataḥ or parataḥ? Before proceeding, let me pause for a moment to further clarify what is meant by “svataḥ,” in svataḥ pram ātva of knowledge. “Svataḥ” means “by oneself.” To say that the truth of a cognition is apprehended “svataḥ” is to say that a cognition apprehends its own truth. But “sva” may mean “by a cognition which apprehends the cognition itself.” In that case “svataḥ pram ātva” would mean that the truth of a cognition is cognized by a cognition which apprehends that cognition. Thus, to say that pram ātva is svataḥ may mean either of the two things: It may mean either that the pram ātva is apprehended by the cognition to which it belongs or the pram ātva is apprehended by the cognition which apprehends the cognition whose pram ātva it is. So, the pram ātva is svataḥ if it is either sva-grāhya (what is apprehended by the cognition whose truth it is, and sva is the original cognition whose truth is under consideration) or svagrāhakagrāhya (that in which the truth is apprehended by a second cognition which apprehends the frst cognition). Against the second view, i.e., the truth is apprehended by a cognition of the cognition whose truth is under consideration, various objections may be raised. It may be asked: What is this cognition of the original cognition (anuvyavasāya)? Is it introspection of the frst cognition? Does it amount to 144 THE MĪMĀṂSĀ DARŚANA saying that the anuvyavasāya, which apprehends the frst cognition, also apprehends that cognition’s pram ātva? It is said in response (the view of the Naiyāyikas and Murāri Miśra, who represents the third school of M īmāṃsā) that since the introspection of the original vyavasāya is a cognition of that cognition, it also apprehends that cognition’s truth. Kumārila, however, does not accept this as a viable alternative. On Kumārila’s view, knowledge is supersensible and it is inferred. It cannot be an object of introspection. A cognition on his view is known only by an inference which uses knownness as a reason. However, no matter whether the truth of a cognition is cognized by a mental perception, or anuvyavasāya, or inferred on the ground of the knownness of the object that serves as a mark, truth is not apprehended by the cognition to which that truth belongs. Against the M īmāṁsakas, the following objection may be raised: Irrespective of whether a cognition (vyavasāya) is apprehended in anuvyavasāya or in an inference with jñ ātat ā as the mark, the vyavasāya is apprehended only qua cognition, but not qua true cognition. In response, Prabhā kara points out that if we regard knowledge to be always sva-sa ṃvedana, i.e., that knowledge always apprehends itself, then we can also say that knowledge while knowing itself also knows its truth. In other words, if knowledge is self-knowing or svasa ṃvedana, then it would also know its own truth. Again, it may be asked: Given that according to Prabhā kara, a cognition is self-knowing, i.e., it knows its own truth, then the error would also be similarly known thereby making falsity also svataḥ? When considering this objection against the Prabhā kara view, we should bear in mind that Prabhā kara does not regard error to be svataḥ. Hence, the question: If knowledge is self-evident, what accounts for the arising of the so-called error? How do the M īmāṃsakas make sense of the alleged falsity of a knowledge? IV Error or the Falsity of Knowledge If all cognitions by nature are valid, how do errors arise? Given that every knowledge is true, argues Prabhā kara, nothing false ever appears in any erroneous cognition. In an erroneous cognition, one thing is taken to be the other. In the supposed erroneous cognition, i.e., “this is a piece of silver,” one thing (e.g., a shell) is seen to be another (e.g., a piece of silver). The question arises: What is the object in this alleged false cognition? It cannot be the shell, because the shell is not manifested in it. There is a cognition assuming the form “this is a piece of silver,” though there is no silver before the perceiver. This false cognition is contradicted by a later cognition of the form “this is not a piece of silver, but a shell”; this later cognition sublates the earlier cognition and proves it to be false. The falsity here is due to the presence of defects, possibly the distance, the defective visual organ, the lapse of memory, etc. So, error is one of omission, not of commission. But, what then, is the status of the cognition “this is a piece of silver” when there is no silver present there? Prabhā kara argues that the cognition 145 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS “this is a piece of silver,” really consists of two cognitions: (1) Perceptual and (2) recollection.28 The “this” expresses a perception and the “silver” expresses a remembered thing. Each is a valid cognition; something is perceived as “this” and a past cognition of a silver is remembered. There is nothing false about the two cognitions. There is, however, a failure to distinguish between the two, not falsely taking the one to be the other. This non-distinction results in the perceiver’s attempt to seize the silver. So, error is an erroneous or incomplete cognition. This view is known as akhyātivāda29 which means “no (false or invalid) cognition”; one does not perceive the silver, rather one simply remembers it. Error, therefore, is non-apprehension and not misapprehension. The Bhāṭṭ as reject this theory.30 Kumārila Bhāṭṭ a points out that simple non-discrimination cannot explain error, because no one can deny that the false object appears before us. Error is mis-apprehension, not a simple nonapprehension; there is a positive confusion of one thing with another, between a perception (“this”) and a remembered (“silver”). So, error is wrong apprehension of one thing as another, which it is not. When we perceive silver in a shell and make the judgment that “this is a piece of silver,” both the subject and the predicate are real. Silver exists, say, in a department store, however, in this instance we bring the existing shell under the class of silver, and error consists in relating these two real and separate existents in the subject–predicate relation. Error is due to the wrong relationship. These errors make us behave wrongly; so, the Bhāṭṭ as call their theory “vipar ītakhyāti-vāda” or the view that an error is the opposite of the right behavior. To sum up: The Prābhā kara school holds that every knowledge is ipso facto valid, and that there is no such thing as error. The Bhāṭṭ as, on the other hand, concede that error may affect relationships, but the objects perceived in themselves are free from error. Both, however, agree that error affects our activities rather than knowledge. Against the Prabhā kara theory, opponents argue that the failure to comprehend the distinction between the two is inadequate to account for erroneous cognitions. Error is not a simple absence of knowledge; it is not a simple failure to comprehend the distinction between the two because if that were the case, the error would occur in the dreamless sleep state as well. The opponents argue that our actual experience testifes to the fact that in an erroneous cognition we initially have a cognition assuming the form “this is a piece of silver,” which is sublated by “this is a shell, not a piece of silver.” Furthermore, if an erroneous cognition were simply negative (i.e., the non-comprehension of the difference between the two), it could not bring about a positive practical reaction, such as withdrawing in fear, for example, in the snake–rope illusion, or proceeding to seize the silver in the case of the shell-silver illusion. Thus, it does not make sense to say that an erroneous cognition is the failure to distinguish between the “this” and the “silver.” Before proceeding further, let us take a moment to assess what precisely is non-discrimination? The notion of non-discrimination or the non-cognition 146 THE MĪMĀṂSĀ DARŚANA of the distinction between the remembered and the perceived is logically opaque.31 The proposition that a table is distinct from a chair signifes that the negation of each obtains in the locus of the other. Distinction is a reciprocal negation (anonyābh āva). Therefore, along with the manifestation of the cognition and its objects, distinction also becomes manifest, the distinction being nothing more than the correlates themselves. It is incoherent to argue that, although the distincts are cognized, the distinction itself is not. The Prabhākara argues that in an erroneous perceiving of the shell as “this is a piece of silver,” perception and recollection respectively of “this” and “silver” are not known to be different. Opponents argue that this is inconsistent with his own admission that a distinction between one unit of knowledge and another is found in the very nature of knowledge, and that knowledge is self-revealing. With respect to the cognitions and their contents, differences are necessarily cognized along with the revelation of the nature of cognitions as well as their contents. Additionally, we must remember that non-discrimination is not a necessary condition for the occurrence of an erroneous cognition. So, the opponents argue that Prabhā kara cannot explain the precise nature of non-discrimination. Additionally, the experience of an illusion shows that it is neither negative nondiscrimination nor a cognition of two experiences. Positive identifcation, as well as the non-knowledge of the difference, can account for a positive activity. Never, indeed, does there arise activity based on the mere non-comprehension of the difference. In fact, as Vācaspati, the author of Bh āmat ī, held both the verbal usage and activity are based upon the comprehension and not merely on the non-comprehension of the difference.32 If it is argued that there would be activity by the mere non-comprehension of the difference, then at the time of the cognition, say, of a pitcher, for example, if there is non-comprehension of the difference from the gem, then there would exist the possibility of activity with a desire to obtain the gem. The silver in the shell-silver example is perceptual. It is not a case of simple recollection. Without the cognition of the identity between the silver with the “this” element before us, there would not be any activity toward it by merely recalling silver. Therefore, the M īmāṃsā view of error cannot be accepted. Most of us experience illusion at some time in our lives, and different factors account for it. When we perceive a shell as a piece of silver, we soon realize that our perception was wrong, and it is sublated. So, questions arise: What is falsity in a false perception? What is the referent of falsity? Does it refer to the apprehension or content apprehended in an erroneous cognition? Perhaps, it is accurate to say that in an erroneous cognition the focus is on the content apprehended than on the apprehension itself. Upon correction, the rectifcation occurs signifying the rejection of the content. All discussions in erroneous perceptions concern the nature and the status of content misperceived. In other words. different theories of error differ about the nature and the status of content rather than subjective apprehension. 147 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS V Theory of the Meaning of Words and Sentences To preserve the integrity of their thesis that the Vedic texts speak of the word as eternal,33 the M īmāṃsakas argue that the words and their meanings are eternal. Kumārila argues that the relationship between the word and meaning is not created, not even by God; the relationship is eternal and inborn.34 In response to the objection that how can the word be eternal, when it is not always present, it ceases and requires human efforts to produce it again, Kumārila argues that human efforts manifest already existing word.35 The word remains present eternally; non-hearing of a spoken word does not imply its destruction; it rather implies its non-perception. To express the meaning, a word, which is a simple aggregate of syllables, is arranged in a certain order. Whereas a syllable is eternal, its sound and form are non-eternal, and its manifestation is a momentary event. Each manifestation leaves an impression on the listener’s mind. The last syllable (of a word) together with its impression and all earlier impressions, make the cognition of a word possible. A word does not denote specifc things that come into existence and pass away; it rather denotes the universal that underlies these things. In other words, the word “cow” does not mean an “individual cow,” but the universal “cowness,” the common feature of all individual cows. However, such sentences as “bring a cow” refer to an individual cow not by virtue of the meaning of the word “cow,” but because of its being invariably associated with the universal feature “cowness.”36 In their theory of word meanings, the M īmāṃsakas differ from the Naiyāyikas. The Naiyāyikas argue that the word “cow” means “an individual cow qualifed by the universal cowness.” The M īmāṃsakas rejects this view. They hold that an individual and its universal features are not ontologically different entities; they are related by a sort of identity (t ād ātmya) by virtue of which when the universal is meant, the individual is also comprehended and co-conveyed. The relation between a word and its meaning is “natural,” and “eternal,” i.e., it is not brought about by any human agency. It is “apauru ṣeya” (authorless). The beginning of the relation is comprehended through listening to the conversations of the elders. A word and its meaning arise together. A word’s principal denotative power is to convey the primary meaning. When the primary meaning is not suitable, one resorts to a secondary meaning or lak ṣa ṇā which, however, must be related to the primary meaning. In a well-known example, the expression “Ga ṇgāyām gho ṣa” (“the village on the river Ganges”) calls for the secondary meaning, namely, “the village on the bank of the Ganges river.” The Meaning of a Sentence A sentence is a group of words satisfying two requirements: (i) The group must have a common purpose and meaning and (ii) the constituent words must 148 THE MĪMĀṂSĀ DARŚANA require each other or arouse in the hearer the expectation of the other. MS in this context uses the Sanskrit concept “ek ārthatva” which means “having an identical artha.” “Artha” may mean either “meaning” or “purpose”; i.e., the unity of the purpose and the meaning go together. The primary purpose of a sentence, according to M īmāṃsā, is an action (kriyā), and other components fulfll the purpose of specifying the object, the agent, the means, and the end of the action. All component meanings revolve around an action. Besides the unity of purpose, meaning, and expectancy (āk āṅk ṣā), the M īmāṃsakas recognize two additional conditions for the constitution of a sentence: Proximity (sannidhi) and appropriateness ( yog yat ā). The component words and their comprehensions must have spatial and temporal proximity. Words uttered or written at remotely distant places and times obviously do not constitute a sentence. “Appropriateness” requires that the component meanings must be compatible. Words sequence in such sentences as “this stone is virtuous” or “sprinkle the grass with fre,” satisfy the frst two requirements, but fail the last test since the concepts of “sprinkling” and “fre” are not compatible, just as “virtue” is not compatible with “stone.” Obviously, appropriateness here is semantical, not simply syntactical. The M īmāṃsakas next discuss the question: How does the cognition of a sentence arise? Which comes frst: Word meaning or sentence meaning? In other words, is sentence meaning apprehended prior to the apprehension of word meaning? On this question, the two schools of M īmāṃsā differ, the Bhāṭṭ as (i.e., the followers of Kumārila Bhaṭṭ a) side with the Advaitins, and the Prābhā karas (the followers of Prabhā kara) oppose them. The Bhāṭṭ a theory is known as “abhihit ānvayavāda” and that of the Prābhā karas as “anvit ābhidh ānavāda.” The Bhāṭṭ as (and the Advaitins) hold that words alone have the inherent capacity to signify their senses, which, in turn, give rise to the sense of a sentence. Words cease to function after indicating their senses. Because the relation of the sense of words is based on words, the Bhāṭṭ as contend that words have the capacity to connote the knowledge of their senses; words convey individual meanings but when joined together, because of congruity, they convey sentence meaning. They urge that “the plea of direct denotation of related meaning as a single act is a hoax.”37 Sentential meaning is apprehended, not from component words, but from word meanings by a process of secondary meaning or lak ṣa ṇā. On the Bhāṭṭ a theory, a sentential meaning is apprehended by the following process: 1 2 3 each word conveys its own meaning by its primary power (śakti), known as abhidh ā or the designative power; these meanings connect by such factors as expectancy, proximity, and appropriateness; and these meanings by a secondary signifcation or lak ṣa ṇā generate a comprehension of sentential meaning as a related entity. This secondary meaning is produced not by component words but by word-meanings. 149 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS The second theory, i.e., the theory of the Pr ābhā karas, holds that the relation among word meanings is the sense of a sentence, and this relation is conveyed by words themselves.38 So, sentential meaning is the meaning of component words taken together. Words do not designate unrelated objects or meanings, but objects as related to each other (anvita). A word is a “pram āṇa” because it designates a related structure which constitutes sentential meaning. Word meaning is related to other meanings in general, while a sentential meaning is the relatedness of other meanings in a specifc manner. Otherwise, there is no difference between word meanings and sentential meanings. In short, both schools accept that on hearing a word, there is the knowledge of its meaning (pad ārtha). The difference between the two theories rests on the question, whether a word designates a pure unrelated object or an object as related to others in general. The Bhāṭṭ a school subscribes to the former position, the Prābhā kara school to the latter. Let me elaborate. Prabhā kara holds that the pad ārtha, i.e., the knowledge of its meaning, is what is meant by a word and it is related to other pad ārthas meant by other words. Hence, the theory is called “anvit ābhidh ānavāda,” i.e., words mean the relatedness to other meant entities in general and sentence means the specifc relatedness to other meanings. The followers of Kumārila, however, hold that the meaning of a word, unrelated to other word-meanings, is what is intended by a word. Pure word-meanings, by virtue of expectancy (āk āṅk ṣā), proximity (sannidhi), and appropriateness ( yog yat ā) get related to other meanings. This is how a sentential meaning is constituted, which, however, is not a pad ārtha. The meaning of a sentence is not a pad ārtha, i.e., the knowledge of its meaning. According to Prabhā kara, words themselves have the inherent capacity to convey their individual meanings, that is, the construed sense of a sentence; words themselves make the sense of sentence known. Upon hearing someone utter words in sequence, one immediately understands the meaning of the sentence that the words express. According to Prabhā kara, the meaning of a word is like a kadamba fower; it consists of infnite little buds. Word meaning then refers to sentential meaning. According to the Bhāṭṭ a theory, a word designates only its own pure meaning. Words alone have the inherent capacity to signify their senses, which, in turn, give rise to the sense of the sentence; words cease to function after indicating their senses. In other words, a word initially signifes its own meaning, then the words in a sentence are put together to construe the sentential sense. Potter concisely explains the difference between the two theories. The two M īmāṃsā theories are primarily theories about the process by which we come to understand the meaning of a sentence…. Prābhā kara’s principle is: understanding of sentence meaning frst, word-meanings later; Kumārila’s is: understanding of word meanings frst, sentence-meaning later.39 150 THE MĪMĀṂSĀ DARŚANA Meaning of the Injunctive Sentences Injunctions or vidhis occupy a central position in M īmāṃsā ethics. In the sentence, “svargakāmo yajeta,” i.e., the performance of sacrifce is enjoined for a person who desires svarga (heaven), the injunctive suffx (i.e., the vidhiliñ in the Sanskrit grammar) conveys that the act leads to the desired object, the act is within the capacity of the person concerned, and fnally, the act does not lead to any adverse consequence. This three-fold meaning constitutes i ṣtasādhanatā prompting the execution of the act.40 About the sentences prescribing an action (vidhivākyas), e.g., “one who aspires to go to heaven should perform (the) sacrifce,” the two schools of M īmāṃsā differ. On the Bhāṭṭ a theory, “you should offer sacrifce,” means that the recommended action is a means for the attainment of the desired result (i ṣtasādhanatājñāna). This knowledge leads the agent to perform the action. But the Prābhā kara school does not consider i ṣtasādhanatā to be the import of the injunctive suffx. The suffx conveys “k ārya,” i.e., the task to be performed which is the import of the sentence. They argue that the injunctive words themselves incite the person (who desires to go to heaven) to perform the action that is recommended. The important step in this process is the realization that this course of action is a duty to be done. The frst view seems closer to the consequentialist variety of the Western ethical theory and the second view comes close to the deontological theory which privileges the sense of duty over the likely consequences. VI Self, Karma, and Liberation Like the Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika, the M ī māṃ s ā regards the self as distinct from the body, the senses, and the mind. The soul is an eternal, infnite substance having the capacity for consciousness; intelligence, will, and effort are its natural attributes. Consciousness is not an essential quality of the soul; it is an adventitious quality. It arises when certain conditions are present. In the dreamless sleep state, the soul does not possess consciousness, because such factors as the relation of the sense organ to the object are absent. For the Bhāṭṭ as, the soul is both unconscious and conscious; it is unconscious as the substratum of consciousness, but it is also the object of self-consciousness. For the Pr ābhā karas, the soul is non-intelligent, the substratum of knowledge, pleasure, and pain, etc. The self is an agent, the enjoyer, and omnipresent, but not sentient. The two schools of M īmāṃsā differ regarding such questions as: How is the soul known? According to the Bhāṭṭ a school, we know it as the object of the “I”; it is not known when the object is known. The Prābhā kara school, on the other hand, argues that the self is known when an object is known; it is revealed in the very act of knowing as the subject of the knowledge under consideration. Both the Bhāṭṭ as and the Prābhā karas subscribe to the doctrine of the multiplicity of souls; there are as many souls as there are individual 151 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS beings. The soul survives death so that it can reap the consequences of the actions performed. The Vedas enjoin that dharma should be performed.41 Following the Vedas, the M īmāṃsakas emphasize the performance of dharma or moral duties to gain moral excellence and divide karmas into (i) obligatory (nitya), (ii) optional (k āmya), and (iii) prohibited. Obligatory karmas must be done because their violation results in demerits, though their performance does not lead to any merit. Optional karmas may be done; however, their non-performance does not lead to demerit. The performance of prohibited karmas leads to demerit. Obligatory karmas again are of two kinds: Those that must be performed daily (daily prayer in the morning and the evening), and those that are performed on special occasions (one should take a bath during the eclipse). Optional karmas are done with a desire to get fruits; e.g., he who wishes to go to heaven should perform certain sacrifces. Finally, there are also expiatory actions to ward off the evil effects of the prohibited karmas. An aspirant in the search of liberation must go beyond both merit and demerit. Obligatory actions are performed following the guidance of the Vedas. Actions must be done without any desire for the results of the actions. For Kumārila, actions are not an end in themselves; they must be performed to realize the fnal goal by overcoming the past and the future accumulated karmas. The M īmāṃsakas theory of śakti has important implications for their theory of ritualistic actions. They argue that the actions performed in this life, generate ap ūrva or unperceived potency which remains and bears fruits in the future. The Sanskrit term “ap ūrva” in common parlance signifes something that is “unique,” “one of a kind,” “exceptional,” “special”; it is something unforeseen, unprecedented, new, not seen before, etc. Both Kumārila and Prabhā kara accept ap ūrva, unperceived potency. Apūrva • • • • Ap ūrva is unseen potency; it is the link between the act and its fruit. Actions performed here produce an unseen potency (ap ūrva) which yields fruits. It is an epistemic apparatus that transcends the temporal distance and provides a causal link between performed acts and their consequences. Whereas Kumārila argues that ap ūrva resides in the soul of the sacrifcer, the performer of Vedic rites, Prabhā kara holds that it resides in actions. The term “ap ūrva” does not appear in Jaimini’s MS. Śabara in his commentary on Jaimini’s MS construes “codana” as “ap ūrva”42; “the performative component of an injunction, that validates all religious actions.” In the absence of 152 THE MĪMĀṂSĀ DARŚANA ap ūrva, such an injunction would be of no value, given that at the conclusion of the sacrifce, it can only be preserved in terms of the results, i.e., in terms of some force, unseen potency, which operates till the result is actually effected. Ap ūrva provides a necessary causal link between the ritualistic actions done and their fruits. Kumārila holds that it is produced in the soul of the sacrifcer and lasts till it begins to bear fruits in the future. Such injunctive statements as “svargak āmo yajeta” cannot be satisfactorily explained unless we accept ap ūrva as the connecting link between the ritualistic actions and the heaven. Halbfass argues: Sacrifcial ‘ap ūrvic’ causality seems to operate within a fnite welldefned set of conditions a kind of closed system, in which it seems to be secure from outside interference: in bringing about its assigned result…. Ap ūrva is a conceptual device designed to keep off or circumvent empirically oriented criticism of the effcacy of sacrifces, to establish a causal nexus not subject to the criterion of direct, observable sequence.43 Śabara argues that this concept provides an answer to the question of how an action, e.g., a ritualistic sacrifce, performed here and now bears fruits later, say, in the heaven. Prabhā kara does not agree that ap ūrva is in the soul, because the soul on account of its omnipresence is inactive. Ap ūrva resides in the act or the effort that produces it. The act perishes after it is done, but ap ūrva—that resides in the act which the suffx “liñ” or k ārya in the Vedic injunction conveys—lasts till the production of the fruit. The effort or the exertion produces in the agent a k ārya or the result, technically called “niyoga,” which provides the incentive to the agent to act. It is important to remember here that ap ūrva is the result, the fnal purpose, of an action; it is different from the action itself. It refers to the invisible force, the invisible results of works which accrue to the doer, the performer of a sacrifce. Both the Naiyāyikas and the Prābhā karas agree that a word has the power (śakti) to arouse experience of its meaning. However, according to the Prābhā karas, this power belongs to words, whereas according to the Naiyāyikas, the power belongs to god’s desire. Only because of god’s desire does a word has the power to connote what it means. The power does not reside in a word. The Prābhā karas recognize that a word itself has the power to signify what it means. When a word’s power (śakti) is known, it generates an agreement with other meanings. For the Naiyāyikas, a word’s śakti remains unknown, and yet generates the agreement with other meanings. On the Naiyāyika account, the memory of the pad ārtha caused by a word generates the knowledge of the meaning of a sentence, a thesis which the M īmāṃsakas do not accept. The deities occupy a secondary place in the M īmāṃsā system. The primary aim of the M īmāṃsakas is to persuade people to practice Vedic injunctions, and not to teach them about god and the deities. 153 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS In the early M īmāṃsā, the attainment of the heaven as the state of bliss was the summum bonum of life; however, eventually the M īmāṃsā commentators, like other Indian commentators, replaced heaven with liberation (apavarga) from bondage.44 They came to believe that actions done with a desire to get fruits cause repeated births. The disinterested performance of actions, without any desire for the results, exhaust accumulated karmas. A person, free from karmas, is not reborn; liberation thus stops rebirth by destroying the accumulated karmas. Past karmas should be exhausted without any residue. Obligatory and compulsory acts should be performed, and the non-performance of these acts would create demerit and result in suffering. Liberation is a state free from all kinds of painful experiences; it is a state in which the soul returns to its intrinsic nature, freedom from pain and suffering. Kumārila and his followers subscribe to jñ ānakarmasamuccaya, i.e., both knowledge and action lead to liberation. Prabhā kara advocates actions as supreme and takes knowledge as the means to liberation. For the M ī m āṃ sakas, the Vedas are self-revealed; God did not author them. The Ny āya and the Ved ā nta, on the other hand, hold that the Veda’s are God’s creations. The M ī m āṃ sakas argue that if the Vedas are taken to be human-authored, then the names of the authors would have been known to us. The Vedas are handed down to us from time immemorial in the form in which we fnd them today. Kum ā rila holds that the meaning of the words of the Vedic texts is comprehended in the same way as the words in the popular language. Let us take the famous Upani ṣ adic mah āv ākya “tat tvam asi.” The difference in their theory of meaning accounts for the differing interpretations of “tat” and “tvam” in “tat tvam asi.” In anvit ābhidh ānavāda, these words convey the cognitions of their primary meanings—the cognition whose nature is memory. In abhihit ānvayavāda, the terms “tat” and “tvam” convey the cognitions of their primary meanings, like memory. Accordingly, sentence-generatedness does not exist in “tat tvam asi”: The knowledge simply arises from the individual word meanings. In other words, word meanings, not a sentence, cause a verbal cognition. Therefore, the cognition arising from “tat tvam asi” is not mediate in nature. The analog offered for this mode of interpretation of the Upaniṣadic text provides one with the phenomenological clue for understanding the sense of immediacy attached to a cognition arising through language. The analog “you are the tenth man” gives rise to a cognition that is perceptual in nature. I will discuss some of these issues in Chapter 14 of this work. VII Concluding Remarks It is especially in their conceptions of knowledge, truth, and action that the M īmāṃsakas left an indelible mark on Indian philosophy. MS and their commentators initiated a discussion of such issues as the sources of knowledge, the relation between knowledge and truth, the intrinsicality or extrinsicality of 154 THE MĪMĀṂSĀ DARŚANA knowledge, and successful practice, etc. Subsequent schools of Indian philosophy further developed the ideas of M īmāṃsā. The Indian philosophers of all persuasion struggled with these issues, interpreted, and reinterpreted them, and, in so doing, further refned these ideas. The following points are worth noting. 1 2 3 4 The M īmāṃsā theory of knowledge infuenced other schools of Indian philosophies; these schools developed the initial insights of the M īmāṃsakas. The M īmāṃsakas were the frst to develop the theory of svataḥ prām āṇya and the Advaitins followed their lead. The M īmāṃsakas made the important distinction between the nirvikalpaka and the savikalpaka perception, as the two stages in the development of perceptual knowledge. In general, Advaita Vedānta accepted the Bhāṭṭ a view of knowledge and thus preserved for posterity the M īmāṃsā view which otherwise would have been relegated to antiquity. Most Vedic systems accept the distinction between the nirvikalpaka and the savikalpaka perception. The M īmāṃsakas started a way of understanding moral practices which continues in the Hindu tradition and found its most famous expression in the Bhagavad G īt ā’s doctrine of karma yoga. The M īmāṃsakas offered one of the frst attempts to systematize the Vedic texts, especially the karma k āṇda of the Vedas. It taught how best to interpret the Vedic injunctions regarding sacrifcial acts and raised many interesting philosophical questions about how to interpret them. They did so without invoking the ideas of deities or god, which for the M īmāṃsakas remained rather posits and not realities. Thus, a Vedic sacrifcial religion was acknowledged without invoking the idea of god as the creator of the universe; “god” was a theoretical posit. Thus, it is not surprising that the Vedāntins regarded M īmāṃsakas as their close kin. Connected with it were the general questions regarding the relation between knowledge and action, and of course the relation between the earlier and the later parts of the Vedas. The M īmāṃsā’s overall contribution to Indian thought is immeasurable. Study Questions 1. Explain the six pram āṇas of the M īmāṃsā school. 2. Comment on the following: M īmāṃsakas argue (i) that the validity of knowledge arises from the very conditions that generate it, not from any extrinsic conditions, and (ii) knowledge is believed to be true as soon as it arises; it does not require additional verifcation by any other pram āṇa, say, an inference. 155 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS a. b. In light of the above quote, explain the M īmāṃsā theory of the self-validity of knowledge. How is a cognition cognized according to M īmāṃsā? What are some of the differences between the Prābhā kara and the Bhaṭṭ a schools on this issue? 3. Critically discuss the M īmāṃsā theory of the meaning of words and sentences. Bring into your discussion important points at issue between the abhihit ānvayavāda and the anvit ābhidh ānavāda theories. Which account seems more plausible, and why? 4. Discuss the Prābhā kara theory of akhyāti. Compare and contrast the two theories of error you have studied in this chapter. Which one do you fnd more persuasive, and why? 5. How does one attain mok ṣa in M īmāṃsā? Suggested Readings For a thematic study of P ūrva-M īm āṃsā, see Ganganath Jha, P ūrva-M īm āṃsā in Its Sources (Benares: Benares Hindu University, 1942); for an excellent discussion of the Bhāṭṭ a theory of knowledge, see Govardan P. Bhatt’s Epistemolog y of the Bh āṭṭa School of P ūrva-M īm āṃsā (Benares: Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series, 1962); for translations, see Kumarila’s Ślokavārtika. Translated by Ganganath Jha (Delhi: Sri Satguru Publications, 1983); see Appendix C of this work for translations of selected aphorisms from Jaimini’s M īm āṃsās ūtras. For a concise and insightful general introduction to various aspects of M īm āṁsā, see A. B. Keith, Karma M īm āṃsā (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1921). 156 9 THE SĀṀK H YA DAR Ś A NA I Introduction Of all the Indian systems of philosophy, Sāṁ khya is perhaps the most ancient; it is also the most respected in antiquity. Historical antecedents of this school are found in the Upaniṣads. The school is famous for its metaphysical dualism between two principles, viz., prak ṛti and puru ṣa, the theory of causation that the effect pre-exists in the material cause and the theory of the evolution of prak ṛti into the manifest world, which includes in its fold the cognitive, the psychological, and the ethical components of human experiences. The desire to know arises to overcome suffering and to attain mok ṣa (liberation, kaivalya), so the stated goal of Sāṁ khya is “soteriological.” The non-discrimination between the unmanifest and the manifest is bondage, and the knowledge of the discrimination between the two is liberation. Such discriminative knowledge is required to reach the goal, which can be achieved not by rituals but by reason and by meditation through the techniques of its sister school, Yoga. The term “Sāṁkhya” is an adaptation from the word “saṅkhya,” and depending on the context, it may mean “number,” “count,” “enumerate,” “rational enumeration,” etc. The school enumerates and rationally examines categories or principles to enable individuals to gain the right knowledge, end their pain and suffering, and achieve liberation. Tradition regards Kapila, a mythical sage, to be the founder of this school. The exact dates of Kapila are unclear; however, one fnds many Kapilas in the history of Indian literature. A Kapila appears in the Ṛg Veda1 and in the Svetāśvatara Upaniṣad, a theistic Upaniṣad,2 which possibly suggests that Sāṁkhya school might have had a distinct theistic tendency and that its origin might predate this work. The epic Mahābhārata mentions Sāṁkhya-Yoga, a school taught by Kapila, a sage, who lived before the sixth century BCE. Book Twelve of the epic Mahābhārata is replete with the proto-Sāṁkhya texts, and recognizes three Sāṁkhya scholars, viz., Kapila, Āsuri, and Pañcaśikha. The Mahābhārata refers to three Sāṁkhya doctrines: Those who accepted twenty-four, twenty-fve, or twenty-six principles, and the last one was theistic. The infuential Bhagavad G ītā is overwhelmingly Sāṁkhya. This school has been a major infuence on the Ayurveda, the Hindu medical formulas, and practices. Īśvarak ṛṣṇa’s S āṁkhyak ārik ā (SK) is the most authoritative and the earliest work available for this school. Īśvarak ṛṣṇa in SK acknowledges that he is laying 157 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS down the teachings of Kapila as taught by Āsuri and Pañcaśikha. He also claims that he has expounded the main doctrines of Sa ṣṭitantra (Doctrine of Sixty Conceptions) in his SK. The main developments of this school occurred in the period extending from the frst century CE to the eleventh century CE. The most important commentary on SK is Gauḍ apāda’s Sa ṁkhyak ārik ābh āṣya. Other important commentaries on SK are Yuktid īpīka and Vācaspati’s S āṁkhyatattvakaumud ī. The S āṁkhyapravacanas ūtra (SPS) is the second most important work of Sāṁ khya after SK. Several commentators wrote commentaries on it; I will mention only two: Anirruddha’s S āṁkhyas ūtravṛtti and Vijñānabhik ṣu’s S āṁkhyapravacanabh āṣya. At the outset, SK declares that the pursuit of happiness is the basic need of all human beings, and there is a need to know the means of counteracting the three-fold suffering. Liberation (kaivalya) comes from the knowledge of the distinction between prak ṛti and puru ṣa. Thus, the three pillars of this system are: Prak ṛti, puru ṣa, and the theory of evolution, the primary focus of this chapter. My exposition in this chapter is primarily based on SK, and I will begin my analysis with the frst pillar, i.e., prak ṛti. Fundamental Postulates 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 There are two primary, mutually irreducible, indestructible principles, viz., prak ṛti (objective principle) and puru ṣa (subjective principle); both are ultimately real. According to the traditional interpretation, prak ṛti is constituted of the three gu ṇas: Sattva (“light,” “luminous,”), rajas (“exciting,” energy), and tamas (“heavy,” “sloth”). On this interpretation, prak ṛti is material; likewise, the three guṇas are also material. Puru ṣa, the principle of consciousness or subjectivity, exists independently of prak ṛti; it is the basic presupposition of experience. There are many puru ṣas; they are qualitatively alike but quantitatively distinct. The effect pre-exists in the material cause; in causation, there is a “real transformation” of the form. Everything in the universe is derived from prak ṛti. When the gu ṇas are in equilibrium, prak ṛti remains unmanifest. When the equilibrium is disturbed, prak ṛti becomes manifest. Bondage is due to non-discrimination between puru ṣa and prak ṛti. The state of kaivalya (liberation), a state of “isolation” or “aloneness,” achieved by the right knowledge between prak ṛti and puru ṣa, is the result of rational thinking. Kaivalya signifes the dissolution of the manifest prak ṛti into an unmanifest state. 158 T H E SĀ Ṁ K H YA D A R ŚA NA II Prakṛti and the Guṇas The S āṁ khya school attempts to provide an intelligible account of our experiences in the world. Our everyday experiences consist of the experiencer and the experienced, the subject, and the object. The subject and the object, puru ṣa, and prak ṛti, are distinct; one cannot be reduced to the other. The S āṁ khya metaphysics is thus based on the bi-polar nature of our daily experiences. We experience a plurality of objects. How do these objects come about? What is the ultimate cause of these objects? The causes are always fner and subtler than the effects. Thus, there must be a cause, some fnest and the subtlest stuff or principle that underlies the entire world of objects. Such a cause is prak ṛti; it is the frst uncaused cause of all objects, gross and subtle. Prak ṛti is imperceptible because it is extremely fne and too subtle to be perceived; its existence is known by inference. Sāṁ khya adduces fve arguments for its existence.3 Arguments for the Existence of Prakṛti 1 2 3 4 5 There must be an unlimited cause of all limited things; there must be a universal or general source of pleasure, pain, and indifference; the primary source of all activity must be a potential cause; the manifested world of effects must have an unmanifested cause; and there must be an unmanifest terminal of the cosmic dissolution. Sāṁ khya conception of prak ṛti is based on the theory that changes in the world are caused; they are not chance occurrences. This theory of causality is known as “satk āryavāda” or the theory that the effect (k ārya) is existent (sat) in the cause prior to its production. The question is: Is the effect something new or different from its cause? The Sāṁ khya school argues that the effect is nothing new because what did not exist could not arise; origination is really a transformation of the cause. Obviously, “cause” here means the “material cause.” Nothing new ever comes into being, only a new form is manifested; the material remains the same. As yogurt is produced from milk, or oil from the oilseeds, or jewelry from a lump of gold, a new form is imparted to the pre-existent stuff. No new stuff ever comes into being. This variety of satk āryavāda, i.e., the theory that the effect is a real transformation of the cause, is known as pari ṇāmavāda (literally, “real-transformation-theory”).4 In support of its theory that the effect is only a manifestation of the cause, Sāṁ khya provides fve arguments.5 159 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS Arguments for Causation 1 2 3 4 5 Something existent cannot arise from the non-existent6; being invariably connected with it, the effect is only a manifestation of the material cause; there is a determinate order obtaining between a cause and its effect so that everything cannot arise from everything; only that cause can produce an effect of which it is capable so that the effect must be potentially present in the cause; and because like is produced from like. The frst argument, one of the axioms of much of Indian thought, may be expressed as follows: “What is, is, and what is not, is not.” In other words, what is, cannot become non-existent, and what is non-existent can never come into being. The G ītā, emphatically declares, “Of the non-existent, there is no coming to be; of the existent, there is no ceasing to be.”7 Given this axiom, it was imperative that philosophers fnd a plausible explanation of change leaving aside the common-sense view that things come to be and cease to be. Platonists gave one explanation while arguing that the forms, the universals, are eternal, and the particulars exemplify the forms that are appearances. Sāṁkhya does not recognize universals as entities; thus, a Platonic like solution was not an available option. So, the school argues that the effect pre-exists in the cause; a non-existent entity cannot be made existent by any operation unless it was already present in the cause. The second argument points to a necessary and invariable relation between cause and effect; a cause cannot produce an effect with which it has no relation. In other words, a cause cannot enter into a relationship with what is not real. Thus, a material cause can only produce an effect with which it is causally related. Therefore, the effect must exist in the cause prior to its production. The next three arguments are close to the Aristotelian notion of potentiality and actuality; certain causes produce certain effects. One can make yogurt only from milk; one can get mustard oil only from mustard seeds, not from other grains. There exists a determinate order between a cause and effect because that alone which potentiality contains yogurt can be the cause of yogurt, and that alone which potentiality contains oil can be the cause of oil; it is not the case that just anything can be the cause of anything. The effect is another state of the cause. Causation is a process of making explicit what was already there implicitly. The cloth is contained in the thread, the oil in the mustard seeds. The thrust of all these arguments is that the effect pre-exists in the material cause; if it were not the case that the effect pre-existed in the cause, one could get any effect from any cause, which would deny the relation of causality altogether. Before proceeding further, let me underscore two points about the above conception of causality: (1) Between the two modes of causality, the effcient and the material, the latter is more fundamental because it is the latter that enters 160 T H E SĀ Ṁ K H YA D A R ŚA NA into the cause and produces the effect; and (2) the cause and the effect are the unmanifest/manifest, the undeveloped/developed states of prak ṛti. Given this conception of causality, it is not surprising that Sāṁ khya philosophers argue that all worldly things are produced from an eternal, original prak ṛti. There have been since antiquity, two accounts of original prak ṛti from which objects of the world emerge: One is atomism, the view that the original stuff really consists of infnitely small elements called “param āṇus.” The Vaiśeṣika school of Indian philosophy developed this position.8 The second account held that the original stuff is a homogeneous mass with no internal differentiation, and that the things of the world arise by a process of progressive differentiation; Sāṁ khya represents this view. The process of evolution (emergence of the twenty-four principles) explains the arising of all worldly things, which I will discuss a little later. For the present, it is important to emphasize that all worldly things include material objects, living beings, the mind, human bodies with their sensory structure, objects of thinking, feeling, and willing. Prak ṛti and its evolutes are possible objects of knowledge; puru ṣa (pure consciousness) alone is not included in the list. Guṇas • • • • • • The term “gu ṇa,” means “strand,” “quality,” “constituent,” “energy-felds.” There are three gu ṇas: Sattva, rajas, and tamas. Sattva represents harmony, goodness, dynamic equilibrium, purity, creativity, peacefulness, virtue, etc. Rajas stands for activity, turbulence, passion, egoism, self-interest, movement, individuation, etc. Tamas signifes restrain, dullness, inertia, darkness, impurity, negativity, disorder, ignorance, violence, sloth, etc. Everything in the world consists of the three gu ṇas in different proportions; they account for the variety that we see in this world. The concept of “gu ṇa” has played an important role in almost all schools of Indian philosophy. It is diffcult to give a one-word translation of this term and capture its meaning. It has been used in a variety of senses in Indian philosophical schools. Depending on the context, it may mean “strand,” “excellence,” “quality,” “a functional principle,” “tendency of something,” “component or constituent,” “energy-feld” “force,” “secondary” (not primary), etc. Sāṁ khya gu ṇas are not Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika qualities; they are “metaphysical reals,” and act as “operational forces,” better yet “operational agents”9 to transform unmanifested or undifferentiated prak ṛti into manifested or differentiated phenomenal world. Let me elaborate. 161 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS Given the importance of the guṇas, there are several interpretations about their nature, the category they belong to, and their relationship to prak ṛti. Since puru ṣa is “pure” consciousness, scholars usually translate prak ṛti as “nature” or “matter” (presumably to contrast puru ṣa with prak ṛti) and likewise take its three guṇas to be “material” in nature. The issue of whether the guṇas are material is quite different from the question to which ontological category they belong, i.e., whether they are objects or substances in the sense in which the philosophers use the term, or properties, or substances in the everyday sense in which water is a substance. Space limitations imposed here do not allow me to discuss these issues in detail. In what follows, I will explore the nature of the guṇas vis-à-vis prak ṛti and in the process discuss such questions as: Are the guṇas constituents or parts of prak ṛti? Why Sāṁ khya needs guṇas? Are the guṇas qualities? Sāṁ khya school maintains that before the world comes into being, prak ṛti is an equilibrium of the three gu ṇas, viz., sattva, rajas, and tamas,10 and these three “make up” the eternal prak ṛti.11 Scholars usually argue that the gu ṇas are “constituents” or “subtle substances” or “indivisible atoms” of prak ṛti. Sharma, for example, holds that prak ṛti is the “unity” of the three gu ṇas and “they are the constituents” of prak ṛti.12 Radhakrishnan states, “The term ‘gu ṇa’ may be translated as ‘attribute’ or ‘quality,’ but technically they are not qualities distinguishable from substance; they are constituents rather than qualities.”13 Hiriyanna maintains that the gu ṇas are “a component factor” or “a constituent” of prak ṛti. These three constituents “though essentially distinct in nature, are conceived as interdependent, so they can never be separated from each other.”14 Dasgupta, argues that the gu ṇas are “substantive entities or subtle substances and not abstract qualities.”15 He further notes: Prak ṛti is the “sum-total of the gu ṇas.”16 For Feuerstein the gu ṇas are “actual entities”; they are not “merely qualities or properties,” as they are the “ultimate building-blocks of the material and mental phenomena in their entirety.” Feuerstein, however, goes a step further and argues that they are “the indivisible atoms of everything there is, with the exception of the Self (puru ṣa), which is nir-gu ṇa. The gu ṇas underlie every appearance and are the world-ground in its noumenal character.”17 The use of such terms as “component” or “constituent” creates the misleading impression that the gu ṇas are “ingredients,” or “features,” or “items” or “parts,” of prak ṛti; nothing could be further from the truth. SK makes a distinction between the evolved (manifest) and the unevolved (unmanifest), and declares that whereas the manifest is caused, non-eternal, and with parts, etc., the unmanifest ( prak ṛti) is the reverse of these.18 Prak ṛti is indivisible and partless; it is not composed of parts.19 Thus, the gu ṇas cannot be the “parts,” or the “constituents,” of prak ṛti. Given that prak ṛti does not have parts, it cannot also be the unity of the gu ṇas; the relationship between the two is not that of a whole and its parts. The whole acts as a container for the parts. For example, a chariot is a whole that contains wheels, axles, poles, etc., as its parts. Or, an automobile has a transmission, clutches, engine, etc., as its parts. Prak ṛti is not the whole that contains the gu ṇas as its parts, so prak ṛti is not the sum-total 162 T H E SĀ Ṁ K H YA D A R ŚA NA of the gu ṇas. In fact, prak ṛti is not different from the gu ṇas. As Mahadeva, in his S āṃkhyavṛttisāras ūtra says: Prak ṛti is not the “substratum” of the gu ṇas,20 and sattva, etc., are not the “properties” of prak ṛti, “because they are the form thereof.”21 Vṛtti and bh āṣya on s ūtra 39 further declare that the relationship between the two is that of identity and that the gu ṇas are the essences of prak ṛti. The gu ṇas in themselves are prak ṛti. Gu ṇas are prak ṛti and prak ṛti is gu ṇas; prak ṛti does not have sattva, rajas, and tamas; it is sattva, rajas, and tamas.22 The manifest, on the other hand, has the three gu ṇas, which, according to SK, are respectively “pleasure, pain, and indifference,” and their “purposes” (artha) are to “shine forth, actuate, and restrain”; “they are mutually subjugative, supportive, generative, and collaborative.”23 Sattva is “light and illuminating” (prak āśa); and, as prak āśa has no weight (gurutva), sattva also does not possess weight. The rajas is “exciting and mobile.” The tamas is “heavy and enveloping” (āvarakatva). The gu ṇas function for the purpose of puru ṣa, i.e., the emancipation of puru ṣa, like a lamp whose single purpose is to give light (just like oil, wick, and fame in a lamp work together).24 Sāṃ khya needs gu ṇas. One may ask why. SK replies that the gu ṇas are needed to transform the unmanifest into the manifold world of phenomena. The unmanifest prak ṛti is the frst cause and it operates through the three gu ṇas, by blending and modifcation on account of the differences resulting from the predominance of one or the other gu ṇa.25 Prak ṛti manifests itself through these “operational-forces” or “operational agents.”26 gu ṇas. The three gu ṇas are needed to preserve the integrity of prak ṛti’s essential nature and make transformation possible. The term “sattva,” literally means “beingness.” The earliest attempt to give “satya” a metaphysical meaning occurs in BU, 27 where sa + ti + yam, the three syllables constituting the word, are interpreted as meaning the real, the unreal, and the real respectively, signifying that unreality is enclosed on both sides by reality. The term “sat” in its ontological sense means “being,” “existing,” “occurring,” “enduring,” etc. However, in the philosophical context, while retaining its ontological meanings, it also has the valuational meaning of true, right, good, etc. The two senses taken together signify the idea of the true being, the essence. Prak ṛti as sattva is existence. Of the remaining two gu ṇas, while rajas is dynamic, mobile, expansive, and makes transformation possible, tamas is inertia, limited, and restrains. These metaphysical agents or forces of prak ṛti work together to unfold the different effects of creation. They compete, dominate, combine, produce (in the sense of modifying each other) in order to create the world. Sattva is progress, rajas provides impetus to move, and tamas resists activity. When one guṇa is brought into play for some purpose, it subjugates the other two; one depends on the other two; they mutually support, cooperate, and combine with each other, just like a lamp, wick (tamas), and fame (rajas), cooperate to give light. Prakṛti functions in accord with the guṇas. As water is one but is found in different forms, as sweet, bitter, cold, hot, etc.28; similarly, the ratio of the guṇas explains the variations that we see in the world. The manifest world is an interplay of these guṇas. It is diffcult to conceive 163 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS of any existent in the world that does not possess these gu ṇas to some degree. All physical and mental phenomena; in fact, all things in the world, represent these guṇas in different proportions. Indeed, all human individuals, by their very nature, are one of these three kinds. In some, sattva predominates; in others, rajas; and in still others, tamas. Leaving aside the Hindu conception of the personality types, but also food (and drink), is of three types contingent upon the proportion of the guṇas. One cannot determine precisely the proportion of each guṇa in the manifested world; nonetheless, the guṇa theory provides a powerful explanation of the physical, the psychological, and the moral aspects of the worldly manifestation. In short, the guṇas pervade all physical and mental phenomena; they explain personality types, psychological types of moods, actions of gravity, etc. A cursory glance at the above description makes it obvious that the guṇas are not “the indivisible atoms,” nor are they objects, like the atoms of the nineteenthcentury chemistry. They are not qualities or properties in the Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika sense of the term. The Vaiśeṣika’s guṇas are static, non-eternal, and cannot exist by themselves. They reside in a substance; they are ontologically different from a substance, and, by defnition, a guṇa cannot possess another guṇa. The Sāṃ khya gu ṇas and prak ṛti are ontologically non-different. The gu ṇas are not static; they themselves possess qualities. As we saw, each of the three gu ṇas is described in terms of the qualities it especially promotes, and they can be mixed. Whether in the original state of equilibrium or in the evolved state of disequilibrium in the world, the gu ṇas are for-another in the sense that they by a specifc teleology internal to prak ṛti exist for the purpose of self, i.e., to serve his purpose. They are each—even in the state of equilibrium with-others, i.e., when each gu ṇa is with other gu ṇas in a “mixing” in different proportions— struggling to increase itself and dominate over the other two. Each thus is in a state of motion; even the tamas—which promotes sleep, stupor, and rest— struggles to overpower the other two. Thus, in a narrow sense, the movement or energy, the dynamis, is caused and promoted by the rajas. In a broader sense, the sense in which prak ṛti is always in motion, each of the three gu ṇas, internally as well as in relation to the other two, is constantly changing. But how does the disequilibrium begin leading to the emergence of the world? To understand the system here, we must frst direct our attention to the second pillar, puru ṣa, pure consciousness. III Puruṣa Puru ṣa is the second ultimate reality admitted by this school; it is the principle of consciousness. Not reducible to prak ṛti, puru ṣa stands apart. This brings me to the second axiom of Sāṁ khya: The Principle of the Irreducibility of Consciousness to what is not conscious, i.e., to prak ṛti. Prak ṛti and its evolutes are the possible objects of knowledge. The Sāṁ khya lists the following as the properties of puru ṣa: It is gu ṇa-less; eternal; inactive; eternally free; not involved, i.e., a witness (sāk ṣin)29; indifferent to pleasure and pain; beyond the three gu ṇas; the seer of all that is seen; and the subject for which all worldly things exist. 164 T H E SĀ Ṁ K H YA D A R ŚA NA Sāṁ khya adduces fve proofs for the existence of puru ṣa.30 Proofs for the Existence of Puru ṣa 1 2 3 4 5 All composite things exist to serve the purpose of a being, and that being is puru ṣa. All objects of knowledge are composed of the three gu ṇas which implies that there is a subject which is not an object of experience, and that is puru ṣa. The experiences need to be co-ordinated; the consciousness that enables prak ṛti to co-ordinate these is puru ṣa. Prak ṛti being non-intelligent cannot by itself experience its products; there must be an intelligent experiencer, and that is puru ṣa. Because there is activity toward fnal release; so, puru ṣa must exist. Prak ṛti being non-intelligent cannot enjoy its own products; puru ṣa is the intelligent subject, who experiences the products. Furthermore, prak ṛti cannot manifest by itself. Puru ṣa is the principle of manifestation, self-manifesting as well as manifesting the other. Puru ṣa is beyond the three gu ṇas; it is uncaused, eternal, a passive witness, and the basic presupposition of all knowledge. It transcends time and space, a pure subject that can never become an object. Prak ṛti functions for the sake of the release (kaivalya) of puru ṣa. To sum up: The contrast between puru ṣa and prak ṛti is as follows: Prak ṛti is the object, puru ṣa is the subject; Prak ṛti is enjoyed; puru ṣa enjoys and suffers; Prak ṛti is active, puru ṣa is not. Prak ṛti is sattva, rajas, and tamas, puru ṣa is beyond them; and Puru ṣa is intelligent, prak ṛti is subject to the interplay of the three gu ṇas. There are, however, on the Sa ṁ khya view, many puru ṣas. Manyness of puru ṣas is asserted on the following grounds: 1 2 3 because of the diversity of births, deaths, and faculties; because of the actions or functions at different times; and because of the differences in the proportions of the three gu ṇas. Thus, the manyness of puru ṣas—as opposed to the Vedāntic thesis that the Self is one—is established on the ground that birth and death, bondage, and liberation, vary from person to person and occur at different times. Additionally, the behavior of different persons also varies and if there was only one self, these variations could not be accounted for. Each body is associated with a I-sense (aha ṁk āra). Sāṁ khya advocates a dualism between prak ṛti and puru ṣa, a dualism that is unlike the Cartesian dualism between matter and mind. In Sāṁ khya dualism prak ṛti is always there. In Cartesian dualism, on the other hand, res cogitans 165 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS (puru ṣa) and res extensa (prak ṛti) are separate, and it is only when res cogitans and res extensa meet that they come to know each other. Pure, undifferentiated prak ṛti evolves into the experienced world. Evolution, however, depends upon some relation between the two principles. But these two, prak ṛti and puru ṣa, are diametrically opposed to each other, so their being together is not intelligible. Additionally, their being together is not enough, because they are always together. Therefore, a relation closer than “being together” is required for prak ṛti to evolve, for its equilibrium to stir, for its original homogeneity to start breaking up. But how can two things, so different, conjoin? Sāṁ khya literature calls it “sa ṁyoga,” which means “conjunction.” But conjunction holds good between two material substances, e.g., a book and my desk. How can there be a contact between a partless, inactive puru ṣa, and (original) prak ṛti that has no internal differentiation? Sāṁ khya replies to this question using various metaphors. Prak ṛti and puru ṣa enter into a relationship “like the relationship between a lame man and a blind man” (in a well-known story). Puru ṣa can see but cannot act (it knows but has no agency); prak ṛti can act but does not know (where to go and on which path).31 When together, puru ṣa knows the way toward the goal it aims at, prak ṛti walks along the path shown. In the story, the lame man climbs on the shoulder of the blind man, and the two together follow the path to reach the goal. But what is this goal? The SK states that puru ṣa must accomplish two goals: “In order to see and in order to reach the state of alone-ness.”32 Puru ṣa can see (can refect images), but prior to the emergence of the world and its infnite concrete objects, puru ṣa has nothing to see (refect). Puru ṣa needs to be a concrete subjectivity. Through this process of increasing concretization, puru ṣa aims at attaining the fnal liberation. The goal seems to be only of puru ṣa; it alone can entertain a goal and determine the path appropriate for this goal; prak ṛti, being active, seems to be led along this path, and toward the goal. When the goal is reached, i.e., when puru ṣa becomes free, their provisional co-operation ends; puru ṣa is eternally free, i.e., alone, and prak ṛti returns to, or rather, relapses into its original state of pure undifferentiated homogeneity. All along the way, nothing happens to puru ṣa. As prak ṛti becomes differentiated, the world with its objects is created (note that Sāṁ khya works use the word “sarga,”33 meaning creation although there is no creator), puru ṣa gets attached and tied to the world; there is a mistaken appearance of puru ṣa as beingin-the-world. Upon seeing this world, puru ṣa becomes free, so writes Gauḍ apāda in his commentary on this k ārik ā. But “seeing,” in this context, is to be understood as “experiencing” or “activity.” Gauḍ apāda elucidates it with the help of another metaphor to further expound the blame man and the lame man metaphor: Just as from the union of a man and a woman a child is born,34 so from the union of puru ṣa and prak ṛti arises creation, and I should add, through the world so created liberation. But is not puru ṣa eternally free, at least, that is what we were told earlier? And, if that is the case, why should it now strive for liberation? I will visit this question at the end of this chapter. 166 T H E SĀ Ṁ K H YA D A R ŚA NA IV Process of Evolution (or Creation) S āṁ khya is basically a monistic cosmology insofar as it derives all evolutes from prak ṛti. The earliest reference to the S āṁ khya variety of progression series, one fnds in the Ka ṭha Upani ṣad, where the order of the series is: (1) Puru ṣa, (2) the unmanifest, (3) the great ātman, (4) the buddhi (intellect-will), (5) the manas (mind), (6) the objects (of the senses), and (7) the senses. 35 The G īt ā mentions twenty four S āṁ khya tattvas (principles): The fve gross or the great elements, the I-sense, intellect-will, prak ṛti, the fve organs of action (karmendriya), the fve cognitive organs, the mind (manas), and the fve objects of the senses.36 Sāṁ khya argues that from the undifferentiated prak ṛti, the world emerges in the following order: Mahat (great or buddhi) → aha ṃk āra (ego-sense, I-sense) → manas (mind) → buddhīndriyas (fve sense organs) → karmendriya (fve organs of action) → tanm ātras (the fve subtle elements) → mah ābh ūtas (fve great or gross elements) Together with the original prak ṛti and puru ṣa, there are twenty-fve tattvas or philosophical truths.37 Knowing these twenty-fve tattvas (in their precise nature) is to gain wisdom that brings about liberation, at least that is what S āṁ khya promises. These tattvas are not empirical facts, but each category is composed of empirical facts. For a clear understanding of the Sāṁ khya theory of evolution, it is essential to understand not only the distinct function of these tattvas, but also to grasp clearly the order of their appearance in the process of evolution.38 The Samkhya Evolutionary Schemata (SK 25, 26, and 27) 1. Purusa 2. Prakṛti 3. Mahat (or buddhi ) 4. Ahaṃkāra Cognitive organs 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Eye Ear Smelling Tasting Touching Action organs 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. Cognitive and Action organ Speech Hand Foot Anus Genital 15. Mind Subtle Elements 16. Sound 17. Touchable 18. Smell 19. Form 20. Taste 5 to 15 consist of sattva guṇa 16 to 20 consist of tamas guṇa 167 Great or Gross Elements 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. Ether Wind Earth Fire Water THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS Let us briefy review these principles and their distinct functions. The frst evolute is mahat, also called “buddhi” or intellect. Buddhi arises on account of the preponderance of the sattva gu ṇa, and its natural function is to manifest itself and other objects. In its original state, it possesses such attributes as knowledge, detachment, power, and excellence; however, when vitiated by tamas, it possesses contrary to the above virtues. In its psychological aspect, the buddhi is intellect-will, and its special functions are ascertainment and decision. Puru ṣa is in direct contact with the buddhi, through which it becomes aware of the activities of prak ṛti. Buddhi, as the discriminative faculty, distinguishes between itself and puru ṣa, and makes liberation possible.39 The second evolute is the I-sense, the “I,” or the ego; there are many egos.40 It is on account of the feeling of the “I” and the “mine” that the puru ṣa takes itself to be an agent as having desires and as striving to achieve certain ends, e.g., enlightenment. The I-sense is of three kinds: It is sāttvika when sattva predominates; it is rājasika when rajas predominates, and t āmasika when tamas predominates. From the frst (sāttvika) arise the eleven organs, namely, the fve cognitive organs, the fve organs of action (karmendriya), and the mind (manas). From the third (i.e., t āmasika) arise the fve subtle elements (tanm ātras). The second (viz., rājasika) is concerned with both, the frst and the third, and supplies the energy needed for sattva and tamas to produce their products. The senses of sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch are the fve cognitive senses. These perceive the physical qualities of color, sound, smell, taste, and touch respectively. The organs of actions are in the mouth, hands, feet, anus, and the genital respectively. The mind (manas), the primary organ, partakes of the nature of both the organs of knowledge and action; it is a member of the psychic triad, the other two members being the mahat and the aha ṁk āra. The manas, though a subtle substance, is made up of parts; so, it can come into contact with several objects simultaneously. The mind synthesizes the sense data and transforms them into determinate perceptions. In short, evolution is a play of twenty-fve principles including puru ṣa, in which prak ṛti is number one, and the fve gross elements the last. The precise interpretation of this chain of creation is a matter of great interest for the Indian philosophers. I will provide an explanation that I fnd appealing. When Sāṁ khya speaks of the “world,” it understands by the word “the totality of human experience.” Experience (bhoga) includes enjoyment, as well as its opposite, i.e., suffering. Sāṁ khya in its theory of evolution gives an account of how pure consciousness (puru ṣa), becomes an enjoyer-sufferer. The question arises: How does pure consciousness become an empirical ego, an enjoyersufferer as well as an empirical cognizer and agent? First, a richly differentiated world of objects with varying proportions of the gu ṇas is required, which is possible only if there are the gross elements or atoms. Gross elements of Sāṁ khya are concretizations of pure sensory data, color, touch, sound, etc., the correlates of the fve sense organs of knowledge and fve sense organs of action. We thereby have all the contents needed for the 168 T H E SĀ Ṁ K H YA D A R ŚA NA empirical ego’s awareness. These are unifed in an “I”-sense. The different “I”-senses, however, are particularizations of the mahat, also known as “buddhi” or intelligence. This story retraces the chain from the evolved to the antecedent conditions. The Sāṁ khya account given above inverts this sequence as the order of creation and answers an old question, asked in the Upaniṣads: How does the one become the many? In response, Sāṁ khya says, “by progressive differentiation and concretization.” It is worth remembering, puru ṣa is independent of prak ṛti; it does not arise from prak ṛti. Prak ṛti and puru ṣa are original principles. As prak ṛti becomes progressively differentiated, “consciousness” ( puru ṣa) is somehow refected in the constituted chain. While puru ṣa appears to become differentiated, it really does not. The relationship between puru ṣa and prak ṛti is like that between jewel and fower. When the jewel stands alone without the fower, the color of the fower is no longer there.41 Another Sāṁ khya metaphor is that of the red rose and the pure crystal. The rose sits behind the crystal, not touching it, but to the eye-level observer in front of the crystal, it appears to be embedded in the crystal.42 The ego becomes “ego-consciousness,” which is not an additional process but occurs because of the “proximity” of the two. Thus, there is a certain phenomenality in this differentiation of puru ṣa as ego-consciousness, sensory-consciousness, body-consciousness, etc. Pure puru ṣa appears to be an empirical person. He appears to experience both pleasure and pain, which seemingly “entangle” him. The bound self—now seemingly a-being-in-the-world, for whom the world is inextricably involved in enjoyment/suffering structure—is brought under the concept of “dukkha” or pain. He then wants to be free from this pain. “Pain” arises from the preponderance of the rajas, the active unsatisfed energy, so to speak. However, cessation of pain comes about through both the knowledge of the true natures of prak ṛti and puru ṣa and requires an excess and predominance of sattva over rajas and tamas. A long and arduous intellectual process aided by yoga culminates in the puru ṣa’s clear and distinct knowledge of its own nature as distinguished from all “natural” or mundane elements with which he had so long identifed himself. The puru ṣa then, is “alone”; he is not in-the-world and also not with-others, which explains why liberation is described as “kaivalya.” All enjoyment and suffering ceases along with its content, i.e., the world. In Sāṁ khya terminology, the manifest world returns to its original home, namely, the undifferentiated prak ṛti. Undoubtedly, there would be innumerable questions about this account. I will here mention and respond to some of them. First, puru ṣa as free is said to be lonely; he is by himself. There is no intersubjectivity, no being-with-other egos. Intersubjectivity is empirical. Pure subjectivity is “aloneness.” Secondly, this tying of the experienced world to puru ṣa seems to make the world subjective-relative, as though each person, each ego, has his own world. With his liberation, his world would cease to be. What about the other subjects and egos? They would still be “bound,” so “in their own world.” This 169 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS asymmetrical distribution of liberation and bondage is one of the premises from which the manyness of puru ṣas—a cornerstone of the system—was in the frst place inferred. The above objection seems plausible. It is indeed true that Sāṁ khya writers did recognize jagadvaicitrya, i.e., many different worlds, each a correlate of one puru ṣa. However, they did not quite realize that they must account for the possibility of one world being “constructed” out of it. It is worth remembering that the original unmanifested prak ṛti is common to all selves, and remains, even after the liberation of one, where and how it was. It is the manifest prak ṛti which dissolves. But how does prak ṛti cease to undergo manifestation, if one self attains liberation? The Sāṁ khya, in reply, uses another metaphor: Just as a dancer dances for the entertainment of the spectator(s) and, when the spectator is satisfed, etc., ceases to dance, the same is true here. Prak ṛti “shows her manifest forms” until the puru ṣa no longer has the desire to see.43 It is important to note that Sāṁ khya uses metaphors: We have had several along the way, the metaphor of the lame man and the blind, the sexual “coupling” of a man and a woman producing a child, jewel and the fower, a rose and the crystal, and fnally, the spectator and the dancer. Can metaphors be substitutes for philosophical argumentation? Can we say, in defense of Sāṁ khya, that philosophical arguments may be either logicalanalytical or poetic-metaphorical? The Sāṁ khya no doubt uses standard Indian logic’s inferences to prove the existence of many worlds of prak ṛti and the manyness of puru ṣas. But when it comes to speaking and making sense of the ultimate relationships (which are yet not empirical relations), metaphors are needed to illuminate rather than to convince the skeptics. They show the possibility of such a relation, not a logical possibility, but an intelligible possibility. Besides, metaphors are deeply embedded in the structure of language and thinking, and if Martin Heidegger is right in saying that original thinking is poetic, then through its metaphors, Sāṁ khya is making its thinking intelligible, if not actual. We have a rhetoric, which has not yet become logic, which is not to suggest that the Sāṁ khya did not have a theory of knowledge, which I will discuss next. V Sāṁkhya Epistemology Sāṁ khya, like the rest of the Indian systems, developed its own theory of knowledge with a theory of inferential knowledge subordinated to it. Knowledge of objects is obtained in the context of a relational structure obtaining within the world; however, without some special relation to puru ṣa, the self would not be a knower and have the mode of awareness “I know.” The faculty of buddhi makes this mode of awareness possible. It is transcendent and shining because of the preponderance of the sattva gu ṇa and creates the impression as if it were puru ṣa. Thus, puru ṣa is refected in it, a refection which is falsely taken to be an experience of puru ṣa assuming the form “I know.” The commentator 170 T H E SĀ Ṁ K H YA D A R ŚA NA Vijñānabhik ṣu with his Vedāntic bias takes this refection to be the result of the superimposition of the buddhi-state on puru ṣa, a false ascription. Puru ṣa now takes the buddhi-state, a mundane transformation, to be its own. This “taking it to be” is not a real content but an appearing to be which, according to some scholars, is “somewhat mythical.”44 Yoga, Vedānta, and Buddhism also subscribe to the doctrine of the close connection between the cognitive process and the buddhi as its instrument, though Buddhism uses the term “citta” for buddhi.45 The infuence of Sāṁ khya on these systems regarding the cognitive process is indelible. In the Nyāya system, buddhi is deprived of this special role, because the word “buddhi” is used synonymously with “knowledge,” and “experience,” and “manas” and the sense-organs are taken to be its instruments.46 There are three kinds of valid cognitions: Perception, inference, and testimony (śabda).47 The objects are determined, “measured,” by the pram āṇas (which are like “measures”) in the same way as in a measuring balance, a thing is measured. I have already discussed the three cognate terms, “pram āṇa,” “pram ā” and “prameya,”48 and I will revisit them again as we proceed in our investigation. For the present, I will provide a quick explanation of the three pram āṇas, viz., perception, inference, and testimony in Sāṁ khya.49 Perception is through the sense organs each having its own specifc object. Perception is the direct cognition of an object when any sense comes in contact with it. SK defnes perceptions as “determination by judgment (adhyavasāya) of each object through its appropriate sense organs.”50 The defnition suggests that perception does not merely receive a sensory datum, but also involves an interpretation, a judgment, founded upon such a datum. When an object, say, a chair, meets the eyes, it is synthesized by the mind. Buddhi then becomes modifed in the shape of the chair. Buddhi, being an unconscious material principle cannot by itself know the chair; however, on account of the preponderance of the sattva gu ṇa, puru ṣa is refected in it. With this refection, the buddhi’s unconscious modifcation becomes illumined as the perception of the object, in this case, a chair. Inference or anum āna is the process by which what is not being perceived is determined.51 SK divides inference into three kinds: P ūrvavat, i.e., that which infers from a mark (li ṇga or the middle term), śe ṣavat, i.e., that which infers from an effect to the cause, and sām ānyatodṛṣṭa, i.e., that which brings together many singular judgments under a universal. In the frst case, p ūrvavat, i.e., “like what has been before,” one infers based on past experiences (hence this name). It is based on the observed uniformity of concomitance between two things, e.g., one sees dark clouds and infers that rain is to follow. The second, i.e., śe ṣavat, proves something to be true by eliminating all other available alternatives; for example, one infers that sound must be a quality because it cannot be a substance, an action, a relation, or anything else. The third, i.e., sām ānyatodṛṣṭa inference, is based on the similarity between the middle term with the facts that are uniformly related to it. The question is: How do we know that we have sense organs? It would not make sense to say 171 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS that perception testifes to the existence of sense organs, because we perceive objects via sense organs. The Sāṁ khya argues that the following inference proves the existence of sense organs: All actions require some means or instrument. The perception of color, etc., is an action. Therefore, there must be some means of perception. Here we infer the existence of sense organs based on the act of perception, not because we have observed the sense organs and the means to be invariably connected. The Sāṁ khya school subscribes to the fve-membered inference of Nyāya.52 What is neither perceived nor inferred. (i.e., not capable of determination by either) is known by the “words of a competent authority” (śabda) by which is primarily meant the infallible words of the sages and śruti. The extremely supersensible objects such as “after-life,” “karma,” and “dharma,” are established by śabda. Things may not be perceived owing to various reasons: Extreme distance (Caitra and Maitra, two persons, are not perceived being at distant places now), extreme nearness (the eye may not see owing to extreme closeness to the object), non-reception of sensations by sense organs (e.g., a blind person does not see since his visual sense organ does not receive visual sensations), subtleness (smoke and vapor are not seen owing to their rarefed natures), lack of attention (attending to one thing exclusively, one does not see things nearby owing to inattention), being over-powered (stars in the sky are not seen during the day, the eyes being overwhelmed by sun-rays), and an aggregate of homogeneous things (one grain of rice is not discriminated after it is thrown into a heap of rice).53 Among the reasons, extreme subtlety is responsible for our not perceiving prak ṛti and puru ṣa. For example, atoms are not perceived because they are extremely subtle (fneness) and are inferred as causes from their effects; similarly, original unmanifest prak ṛti is inferred from such experienced entities as buddhi and ego-sense as their cause on the bases of similarity and difference. The effect must be like the cause in some respects but different in other respects, as children are both like and unlike their parents, on the basis of the fact that they are both vir ūpa and sar ūpa.54 Further inferences are used to prove that these effects must have been previously existent in the cause. VI Concluding Remarks Sāṁ khya is a grand intellectual accomplishment by way of incorporating all aspects of human experiences in their variety as well as in their commonalities within one conceptual framework. There is an overpowering tendency to take recourse to a monism, with materialism55 at the one end and monistic idealism at the other. Sāṁ khya skillfully avoids these extremes, ending up with a 172 T H E SĀ Ṁ K H YA D A R ŚA NA dualism, not a provisional dualism, but a fnal, further irreducible dualism. Such a dualism, the G īt ā also incorporates into its monistic framework, albeit a provisional dualism to be overcome ultimately. In Sāṁ khya, this dualism between prak ṛti and puru ṣa continues even when the world dissolves, i.e., in the state of mok ṣa (kaivalya), experience ceases to be, prak ṛti returns to its quiescent state of equilibrium, and puru ṣa remains what it was originally, unbound, and eternally free. To render its dualism intelligible, Sāṁ khya needed some sort of relationship—other than the simple difference between prak ṛti and puru ṣa. Accordingly, Sāṁ khya in its later development modifes this total otherness somewhat and informs us that prak ṛti is for the purpose of puru ṣa. This concession—namely, that prak ṛti, despite its total difference from puru ṣa, exists for the sake of puru ṣa, for satisfying the goal of puru ṣa, that puru ṣa by “seeing” prak ṛti comes to its own satisfaction and prak ṛti returns to its quiescent state— opens a Pandora’s box. If prak ṛti is totally other than puru ṣa, how can it yet be for the sake of puru ṣa? Does not this “being for” militate against the autonomy of prak ṛti? The idealists use this separation to make the case that Sāṁ khya is only a stepping-stone for Advaita Vedānta; thus, in the long run, prak ṛti is only a “posit” of puru ṣa, that puru ṣa sets up its own opposite, its own other, to achieve a goal. But, even for the Advaita school, what could this goal be? For both the Sāṁ khya and the Advaita schools, it is freedom, no doubt; however, how could freedom serve as a goal if puru ṣa is eternally free? One answer, which the Sāṁ khya offers, is to strive after freedom, puru ṣa must get entangled with prak ṛti, i.e., it must be “bound” and in chains. So, we have a strange circularity: Puru ṣa gests imprisoned to become free, though it is eternally free (nitya m ūkta). From this charge of circularity, neither Sāṁ khya nor the Advaitins have any escape save by subscribing to the theory that really there is no creation, no imprisonment, no chain, no escape from it, except in the sense of removing an “illusion.” The Sāṁ khya realism, however, rebels against such a position. Must we, at least, concede that Sāṁ khya realism is slightly softened by prak ṛti’s “being for puru ṣa,” though not abandoned? How does all this hang together? Clearly by admitting a sort of “unconscious teleology,” “a purposiveness but no purpose,”56 a purposiveness built into prak ṛti and manifested in its ordered development, and the sequence “naturally” geared towards that purpose, and a purposiveness built into puru ṣa whose for being, its raison d'être, is to achieve kaivalya and the return of prak ṛti to its quiescent state. Notice that this is the only system of Indian thought that has a teleology built into it. This teleology combined with the autonomy of prak ṛti also saves the Sāṁ khya school from materialism or gross naturalism. Prak ṛti, though unconscious, is not matter. It is acit, but consists not of atoms whirling about, but of the so-called “gu ṇas.” The gu ṇas are not full-blown personal agents or fullblown emotions, but they may be shaped after such agents or emotions. The most vivid way we experience causation is through making things happen as agents, or as being moved to act by our emotions. The descriptions of the gu ṇas 173 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS as operational agents bring together a conception of intellectual, ethical, and psychological, attributes (and propensities), as well as physical characteristics in a curious manner. The gu ṇas are neither material nor mental. According to one etymology, the “gu ṇas” are so-called because they serve a twofold purpose: They appear to bind puru ṣa and also serve (in the case of “sattva”) the purpose of both bondage and freedom. This is another consequence of the purposiveness without purpose. Sāṁ khya usually has been construed as a variety of naturalism, implying the belief that everything arises from natural causes and properties, which either rules out or slights the belief in the supernatural. If “naturalism” is taken to be the thesis that the mind is reducible to natural processes, then Sāṁ khya may be said to be “naturalism.”57 However, manifested nature is not all of reality. There stands opposed to it, irreducible to it the principle of subjectivity, i.e., consciousness (puru ṣa), the basic presupposition of any experience, which limits the systems “naturalism” (perhaps, a better characterization for Sāṁ khya than “materialism”). Critics have taken Sāṁ khya to task for their conception of the gu ṇas. Śa ṃkara, for example, argues that the qualities represented can only belong to a “spirit,” not to the unconscious prak ṛti or nature. The Sāṁ khya cryptic admission of “being for the other,” of prak ṛti’s “being-for-puru ṣa” determines this feature, even of the gu ṇas, which are prone to accentuate or refect certain qualities in puru ṣa; they stimulate tendencies and appropriate dispositions. “Prak ṛti” thus is not to be understood naturalistically; it is misleading to construe it as purely physicalistically or materialistically. Puru ṣa has no qualities; it is pure consciousness plain and simple. Finally, the state of liberation as “alone-ness,” implies a total negation of inter-subjectivity which is not a very attractive goal no doubt, yet it is the original ontological state of puru ṣa. But we are also informed that there are many puru ṣas. Manyness (of puru ṣas) implies that they are mutually different, and this difference seems to be built into the domain of puru ṣa. Is puru ṣa’s oneness consistent with its manyness? The Advaitic account eventually comes to terms with the utter inexplicability of individuation by coming to regard the many as but a product of avidyā, ignorance. The many is said to be the līl ā, i.e., the sport of the One, the brahman; in saying this, the Advaitins emphasize that the brahman could not have any purpose in creating the Many. On the Advaita logic, the differences are false, a mere appearance. In Sāṁ khya, any distinguishing feature of one person from another becomes a product of prak ṛti and so an empirical feature deriving from the body-mind complex. When puru ṣa is considered by itself in its purity, whence its differentiating feature? The Sāṁ khya arguments for manyness are double-edged. The determinate order of bondage and liberation, for example, the order, namely, that my bondage persists even when you are liberated, is tentatively persuasive. But recall that bondage and liberation are conditions of the empirical persons, not of pure puru ṣa. Yet the Sāṁ khya intuition that there is a manyness of puru ṣas is undeniable, and the diffculty reappears from the other side as well: A monist 174 T H E SĀ Ṁ K H YA D A R ŚA NA must explain how does even the phenomenon of manyness, of distinct puru ṣas, appear at all? I concede Sāṁ khya its fundamental intuitions. The system is a daring attempt to accommodate them with great skill no doubt but how successfully? I will let my readers answer this question. I do not wish to treat them as a mere stepping-stone to the non-dualism of Advaita Vedānta. Study Questions 1. Explain the Sāṁ khya theory of prak ṛti and the three gu ṇas. 2. Discuss the fve arguments that Sāṁ khya provides to prove that the effect pre-exists in the cause. Sāṁ khya school argues that “the effect is nothing new, because what did not exist could not arise; origination is really a transformation of the material cause. Nothing new ever comes into being, only a new form is manifested; the material remains the same.” Do you fnd the Sāṁ khya position plausible? Give reasons for your answer. 3. Discuss the Sāṁ khya arguments to prove the existence of puru ṣa and the multiplicity of puru ṣas. Do you fnd these arguments convincing? Substantiate your position with rational arguments. 4. Discuss the Sāṁ khya theory of evolution. Analyze the distinct function of each of the twenty-fve principles. 5. Sāṁ khya describes the state of liberation as “alone-ness.” Do you fnd it appealing? Why should one pursue it? Critically explain the Sāṁ khya conceptions of bondage and liberation. Suggested Readings For a useful introduction, see Gerald James Larson, Classical S āṃkhya: An Interpretation of Its History and Meaning (Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass, 1998). Also, see Gerald James Larson and Ram Shankar Bhattacarya (eds.), S āṃkhya: A Dualist Tradition (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1987). To date, this is the most comprehensive work in English on this school; it not only includes the historical development, summaries of major texts, and thinkers of the school, but also an analysis of the important concepts and conceptual distinctions. The S āṃkhya Philosophy, Nandalal Sinha (tr.), Sacred Books of the Hindus (New York: AMS Press, 1974), Vol. 11, contains translations of S āṁkhyapravacanas ūtra Anirruddha’s S āṁkhyas ūtravṛtti and Vijñānabhik ṣu’s S āṁkhyapravacanabh āṣya, and more. Mike Burley, Classical S āṃkhya and Yoga – An Indian Metaphysics of Experience (New York: Routledge, 2012), provides a unique interpretation of the Sāṃ khya school. 175 10 THE YOGA DAR Ś A NA I Introduction “Yoga” is a general term associated with a variety of physical, mental, and spiritual practices or disciplines that originated in ancient India. These practices are used for the realization of the highest goal of life. The roots of yogic practice, however, are traced to the Dravidian culture of pre-Aryan India. Some scholars argue that the Indus Valley civilization practiced a form of meditational yoga. The archaeological excavation of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro has uncovered this non-Aryan origin of yoga practice. Several fascinating seals picture a male person sitting in a “lotus position,” typical of the later India’s meditational yoga. An unusual stone bust in a yogic posture provides additional testimony of the practice of yoga in pre-Aryan India. It is obvious that yoga has been practiced in India since well before recorded history; it is an integral part of the Indian culture and philosophies. There has been a very ancient tradition of the practice of yoga in Aryan India: The Ṛg Veda, some of the early Upaniṣads, the epic Mah ābh ārata, C āṇakya’s Artha śāstra, and the early Buddhist writings provide eloquent testimony to the practice of yoga in India. It is an important component of the spiritual practice of the Indian ascetics of all varieties, and most Indian philosophical systems recognize the importance of practicing yoga in some form or the other. Yoga is one of the six āstika darśanas of Indian philosophy. It is diffcult to ascertain precisely when Yoga became a school of Indian philosophy. Yoga, as a philosophical system, i.e., as a darśana along with the other Indian darśanas, however, goes back to Patañjali’s Yoga S ūtras, the foundational and the most important work of this school. Leaving aside Yoga S ūtras, several works have been credited to Patañjali. A person named Patañjali also authored Mah ābh āṣya, an ancient work on the Sanskrit grammar and linguistics based on the A ṣṭādhyāyī of Pāṇ ini. It is doubtful that the same Patañjali authored both works. However, there is no doubt that Patañjali’s Yoga S ūtras is the frst systematic work on Yoga darśana. Vyā sa’s commentary on Yoga S ūtras entitled Yogabh āṣya, Vācaspati Misra’s Tattvavai śāradi, Bhojarāja’s Yogas ūtravṛtti, and Vijñānabhik ṣu’s Yogavārtika and Yogasārasa ṅgraha are also useful sources of the Yoga school. 176 T H E YOGA DA R ŚA NA Fundamental Postulates 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 The aim of yoga is cittavṛttinirodha, i.e., “the cessation of the modifcations of the citta.”1 There are two primary, indestructible principles: Prak ṛti and puru ṣa. There are fve kinds of mental modifcations or cittavṛttis: Pram āṇa (right cognition), viparyaya (wrong cognition or error), vikalpa (imagination), nidrā (sleep), and sm ṛti (memory). The fve defects (kle śas) opposed to the practice of yoga are ignorance, ego, desire, aversion, and clinging to life. Puru ṣa, though eternally free, when refected in the citta, becomes a jīva. There are fve levels of citta (cittabh ūmi). These are: K ṣipta or constantly moving, m ūdha or fxed on one object and without the freedom to move on to another, vik ṣipta or distracted, ek āgra or onepointed, and niruddha or restrained. Patañjali rejects the heavenly worlds promised by the Vedic texts as rewards of the ritualistic performances. Patañjali does not regard Īśvara as the creator of the universe; Īśvara is only a special kind of puru ṣa. Īśvara is the model of the highest perfection and knowledge. The etymology of the word “yoga” is derived from the root “yuj,” meaning “to connect,” “to unite” two things, i.e., yoking the higher self with the lower self. Though the overall metaphysical and epistemological theses of the Indian darśanas vary considerably, the underlying idea—that the senses, passions, desires, etc., lead individual beings astray, and the practice of yoga is the best way for self-purifcation by calming the senses—remains the same. If one’s mind and body are impure and restless, one cannot really comprehend spiritual matters. Yoga lays down a practical path for self-realization, i.e., the realization of the self as pure consciousness. It has become common to couple Sāṁ khya and Yoga together. Sāṁ khya explicitly accepts yoga as the practical means to the realization of mok ṣa (kaivalya), and the Yoga school subscribes to the theoretical framework of the Sāṁ khya school. Patañjali was a brilliant compiler of the fundamental ideas of yoga, and in that compilation exhibited his undeniable philosophical and systematic thinking. Today, while the works on yoga abound in all Western languages, it is worthwhile to review the Yoga S ūtras, which is the classic text on the theme of yoga and has stood the test of time. For all practical purposes, the Yoga S ūtras accept the metaphysics and epistemology of Sāṁ khya: The Yoga school, like Sāṁ khya, accepts two primary, indestructible principles, prak ṛti (objective 177 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS principle) and puru ṣa (pure consciousness); three pram āṇas: Perception, inference, and testimony, but adds the requirements, the steps, the parts, of the discipline to enable the aspirant to progressively achieve the goal of mok ṣa. The study of yoga is an important means to get to know a major component of Indian life and culture. Given that metaphysics, epistemology, and the theory of evolution, have already been discussed in the Sāṁ khya chapter, this chapter will focus on Yoga Psychology, Ethics, and God. II Yoga Psychology In the S āṁ khya-Yoga school, the j īva or the individual self is of the nature of consciousness (cit); it is free from the limitations of the body, the senses, and the modifcations of the mind. Knowledge, as we know, is a product of prak ṛti; it is ascribed to the self ( puru ṣa) falsely. Puru ṣa—the word Yoga Sūtras frequently uses for the self—by mistake takes the mind to be the knower. All cognitive functions and the resulting cognitive products belong to citta, a product of prak ṛti. The goal of the practice of yoga is to empty the thought process of phenomenality, to gain knowledge of the true self, by distinguishing it from prak ṛti. Patañjali defnes “yoga” as “cittavṛttinirodha,”2 which means “the cessation of the modifcations of the citta.”3 So, before proceeding further, let us ascertain what is meant by “citta.” In Buddhist literature, “citta” is usually translated as “mind.”4 On the Yoga view, however, citta is a comprehensive designation that includes among other things, manas or mind, “ahaṁkara” or “the I-sense,” and the “buddhi” or “intellect,” which assist the self to acquire the knowledge of the world. “Manas” in the narrow sense, receives and organizes sensations; “ahaṁkāra” is the source of self-awareness, self-identity, and self-conceit, and relates sensory objects to the ego; “buddhi,” produces knowledge of the object, and makes judgments and discrimination possible. Manas, ahaṁkāra, and buddhi, have the three guṇas5— sattva, rajas, and tamas—in different proportions. The knowledge that brings about liberation puts an end to the incessant modifcations of the mind (cittavṛttis). In ordinary parlance, a cittavṛtti is a mental modifcation (cognitive mode) of the mind which is in a constant process of change or fow. If citta is an ocean, then the cittavṛttis are its waves. In the Western philosophical vocabulary, we can say that citta is constantly outward-directed; its intentionality is in a process of change, which is the cause of suffering or dukkha. Patañjali defnes yoga as a cessation of the changing intentionality of citta. When the activities of the body, the senses, and the mind are under control, the modifcations of the citta are suppressed, suffering ceases, the self discriminates itself from the mindbody complex and returns to its true nature as pure consciousness. Patañjali, after defning “yoga,” discusses vṛttis (mental modifcations).6 The fve cittavṛttis or cognitive mental modifcations or modes are: Pram āṇa (right cognition), viparyaya (wrong cognition or error), vikalpa (imagination), nidrā (sleep), and sm ṛti (memory).7 178 T H E YOGA DA R ŚA NA Cittavṛttis (Cognitive Mental Modes) 1 2 3 4 5 Pram āṇas (means of right cognition) Viparyaya (misconception, not seeing things as they really are) Vikalpa (imagination) Nidrā (sleep, lack of cognitive mode, dreams, etc.) Smṛti (recollection of past experiences) The pram āṇas are the ways of arriving at the right cognitions. As stated earlier, the Yoga school accepts three pram āṇas: Sense perception, inference, and verbal testimony.8 In an external perception, there is a contact between the senses and the object, and the mind is transformed into the shape of the object. The citta—being extremely clear on account of the preponderance of the sattva gu ṇa and being closest to the puru ṣa—catches the refection of puru ṣa and becomes conscious so to speak. In sense perceptions, we apprehend the generic as well as the specifc characters of an external object through the sense organs. Sense perception is a vṛtti which apprehends the specifc and the generic nature of an external object Thus, in perceiving a cow, we not only know that the animal is a cow but also that she is white in color. The mind receives an impression, consciousness is refected in it, resulting in consciousness seeing its own refection as containing the form of the object (see the fgure given below). It therefore appears as if the self knows the object. Mind Object Consciousness or Puru˜a Impression: the form of the object Reflection in the light of consciousnes In inference, the object is mediately known through the perception of another object with which it has the relation of universal co-presence. By inference, one knows the generic nature of objects.9 Verbal testimony is the way one comes to know an object (which one does not himself perceive or infer) based on the verbal reports of a trustworthy speaker who has known the object. The speaker must be free from defects, such as illusion, deceit, laziness, etc., and must also be compassionate. It is also 179 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS the source of our knowledge of the super-sensuous entities. The most important kind of such knowledge is that which we derive from the “heard texts” (śrutis). Of the three means of right knowledge in the Yoga system, perception is the most important. The Yoga S ūtras do not appeal to any śruti, but rather to the direct experiences of the yogin, i.e., of the person who has achieved the goal of practicing yoga. This shows the empiricistic trend of the school. It is not surprising that some yoga commentaries recognize different kinds of perception, including yogic perceptions. The second vṛtti is “misconception” (viparyaya). It consists in taking something to be what it is not10; it is misconstrual of reality. Taking a rope to be a snake is an example of wrong knowledge; it is a cognitive error. It includes doubt as well as uncertain knowledge. The three additional vṛttis, imagination or vikalpa, sleep or nidrā, and memory or smṛti, are unique to Yoga; other systems of Indian philosophy do not recognize them as vṛttis. Imagination or vikalpa is a verbal idea caused by words corresponding to which there is no real object. In the words of K. C. Bhattacharya, it is “implied in the consciousness of a content that is not real, and is still verbally meant.”11 Thus, when one thinks of “hare’s horn” or of “a barren woman’s son,” there is a meant content, which though unreal, is presented to understanding. Yoga philosophy recognizes many such vikalpas or imaginative entities. For example, when one says, “Rahu’s head,” it creates the impression that there is a distinction between Rahu and his head, whereas the fact of the matter is that Rahu is only a head. Similarly, the expression “consciousness belongs to puru ṣa,” implies that there are two separate entities consciousness and puru ṣa, but, in fact, consciousness and puru ṣa are identical. In nidrā,12 there is a preponderance of the tamas gu ṇa, and the resulting cessation of waking and dream experiences. It stands for the absence of any cognition; however, it is a vṛtti because after waking up a person says, “I slept soundly and did not know anything.” Thus, “sleep,” in this context, refers to the deep sleep state. Yoga is unique in regarding sleep to be a vṛtti and comes close to Advaita Vedānta in this regard. Both agree that in sleep, even in the deep sleep state, there is consciousness because recollection upon waking up testifes to its existence.13 The last vṛtti is memory defned as “holding on” or “not slipping away” or “retention” of the objects of the other four vṛttis.14 K. C. Bhattacharya takes thinking (cint ā) to be the second level of memory (i.e., the memory of memory) and contemplation or dhyāna (which is a series of memories) to be the third level.15 Sam ādhi, at which one arrives as a result of the cessation of vṛttis, is not a memory, but an intuition of the object. For Yoga, as we will see shortly, sam ādhi is of various grades. Puru ṣa, though eternally free, when refected in the citta, becomes a jīva, an ego, goes through pleasurable and painful experiences, takes himself to be an agent, enjoyer, etc., and subjects himself to various kinds of affictions, which 180 T H E YOGA DA R ŚA NA are either harmful or opposed to the practice of yoga or not so opposed.16 The vṛttis that are opposed to the practice of yoga are really made so by the fve defects (kle śas): Ignorance, ego, desire, aversion, and clinging to life.17 Ignorance or avidyā is the root cause of the fve defects.18 Ignorance results in taking the pure, blissful, self to be the non-self, which is non-eternal, painful, unclean, and impure.19 Non-self in this context includes body, mind, all material possessions, which an ignorant person takes to be one’s self.20 Egoism (asmit ā) is the consciousness of the seeming identity of the self and the buddhi, i.e., of the seer and the instrument of seeing. It is taking the buddhi or the intellect as the true self.21 In reality, the self is unchanging while intellect is always changing. Raga or attachment arises, holds Patañjali, from the experience of happiness, i.e., from the memory of past experiences of happiness.22 This memory gives rise to the desire to re-live that experience. In the same way, aversion arises from the experiences of pain.23 Clinging to life is on account of the fear of death which is common to almost all living beings; it is found in the ignorant as well as in the wise individuals. This fear is due to the experience of death in a previous life and for the Yoga school, it proves the existence of a previous life. The desire assumes the form “let me be.”24 The continually changing cognitive modes can be restrained by practice (abhyāsa) and detachment (vairag ya).25 Continuous effort is needed. When these fve detriments are “burnt,” citta is dissolved into the original prakrti. The vṛttis of citta, the cognitive modifcations, can be eliminated by meditation. If the detriments remain, there are cognitive modifcations and there is suffering. Thus, suffering characterizes existence; the aim of yoga is to get rid of suffering. The Yoga S ūtras closeness to Buddhism is nowhere clearer than on this point. III Yoga Ethics Five Levels of Citta It should be obvious to the readers that the aim of yoga is to prevent identifcation of puru ṣa with mental modifcations by arresting or suppressing modifcations of the citta. The citta, constituted of the three gu ṇas, i.e., sattva, rajas, and tamas in different proportions, determines the different levels or conditions of citta. There are fve levels of citta (cittabh ūmi), viz., k ṣipta or constantly moving, mūdha or fxed on one object and without the freedom to move on to another, vik ṣipta or distracted, ek āgra or one-pointed, and niruddha or restrained. In the buddhi at any state, there is a fow into the form of self-identity, except this self-identity is not always explicitly manifest. When it is explicit, there is sam ādhi. Yoga philosophy emphasizes practical discipline with an emphasis on meditation, mind control, and repeated practice. The goal is to arrest mental modifcations with an effort that gives rise to different levels of citta. 181 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS At the frst level, i.e., the k ṣipta level, the citta is under the sway of rajas. It is restless and agitated; it wanders from one object to another without any rest. The citta focuses on sense objects, and the goal is sense-gratifcation. The citta jumps from one object to another. We may call it the “wandering” level of citta. At the second level, i.e., m ūdha level, the effort to control the citta does not help, because the citta is under the sway of tamas. It is drawn to vices, sleep, inertia, lack of motivation, and so on. It is not interested in the practice of yoga. This is the “ignorant” level of citta. At the third level, i.e., the vik ṣipta level, the citta is not under the infuence of sattva though it has a touch of rajas in it. This level has the capacity of manifesting all objects, virtues, knowledge, etc., with the ability to concentrate on an object, though such a concentration is temporary. In other words, the arrest of mental modifcations and avidyā, etc., is temporary. This is the “unsteady” level of citta. At the fourth level, i.e., ek āgra or one-pointed level, the citta is not under the infuence of sattva; rajas and tamas are subdued. The beginning of the prolonged concentration characterizes this level. At this level, mental modifcations are restrained, though only partially.26 This is the “focused” level of citta. The fourth level is preparatory to the next and the last level, viz., “niruddha,” where all mental modifcations including the mental concentration that characterizes the ek āgra level cease to exist. In niruddha, citta is calm and peaceful and returns to its original state. This is the “restrained” level of citta. The last two levels take one to sam ādhi, the transcending of the fve levels. These form an integral part of the a ṣṭāṇga yoga (the discipline of “eight-limbed yoga”); they are conducive to higher awareness. It is important to remember that the last two stages are conducive to mok ṣa because both manifest the maximum of the sattva gu ṇa. In the ek āgra or the one-pointed consciousness, buddhi attains explicit consciousness of selfidentity. The mind focuses on the object of meditation, the meditator and the object of meditation are fused together—though the consciousness of the object of meditation persists. In fact, it is samprajñ āta sam ādhi27 or the trance of meditation because in this state the mind establishes itself permanently in the object; it has a clear and distinct consciousness of the object and assumes the form of the object. The niruddha is asamprajñ āta sam ādhi, the culmination of the process, the yoga in the strict sense.28 The vṛttis are restrained, though latent impressions persist. It is not easy to attain a state of niruddha. The path that helps one attain the highest is “asṭāṅga yoga,” which I will discuss next. The Eight Limbs (A ṣṭāṇga Yoga) Patañjali’s yoga is eight-limbed (asṭāṅga).29 The a ṅgas or limbs are: (1) yama or control, (2) niyama or regulation, (3) āsana or bodily posture, (4) prāṇāyāma or regulation of breath, (5) pratyāhara or withdrawal or removal of the senses, (6) dh āra ṇā or concentration, (7) dhyāna or meditation and (8) sam ādhi or absorption. 182 T H E YOGA DA R ŚA NA It is important to underscore the fact that detachment and abhyāsa or practice are the most important components of any yogic practice. Detachment is freedom from craving—again, a Buddhist-sounding idea—of sensory objects. One must cultivate detachment from two kinds of objects: The objects seen in the world and the objects heard about in the scriptures (e.g., pleasure in the heaven). Patañjali rejects the heavenly worlds promised by the Vedic texts as rewards of the ritualistic performances. A yogin must have no attachment to either. Complete detachment is attained when the yogin knows the true nature of puru ṣa and does not desire anything material, i.e., anything constituted of the three gu ṇas. The fnal goal is not attained all at once as it is possible to attain prolonged contemplation and relapse back into pain and suffering due to past tendencies and impressions. The practice of yoga with care and undivided attention is of the utmost importance. Vṛttis leave behind sa ṃsk āras that lie dormant in the citta, manifest under appropriate conditions, generate karmas, and perpetuate the cycle of birth and death. Once all sa ṃsk āras are destroyed, pure consciousness is revealed; however, it requires a long and arduous training to attain the cessation of all the modifcations of the citta and attain the highest. An aspirant in the initial stages of the discipline is required to practice different postures, different kinds of regulations, e.g., regulations pertaining to breath, which form the foundation on which to erect an effective practice. For the purifcation of the citta, Patañjali presents the discipline of A ṣṭāṇga Yoga or “the Eight Limbs.” A ṣṭāṇga Yoga (The Eight Limbs) 1 Yama Restraints of body, mind, and speech 2 Niyama Regulations pertaining to good conduct 3 Āsana Bodily postures 4 Prāṇāyāma Regulation of breath (inhaling and exhaling) 5 Pratyāhara Detachment of mind from the external world 6 Dh āra ṇā Concentration of mind on an object (internal or external) 7 Dhyāna Continued meditation or concentration on an object 8 Sam ādhi Absorption or self-realization Yama30 and niyama,31 i.e., the frst two of the eight a ṅgas or limbs, are the needed preliminaries to any ethical and religious disciplines. The Yoga S ūtras prescribe fve yamas or ethical rules: (1) Non-injury in thought, deed or speech (ahi ṃsā or non-violence), (2) truth-telling (satya ṃ), (3) non-stealing (asteya), (4) celibacy (brahmacarya), and (5) non-possession (aparigraha). Patañjali regards these fve as “the great vows” that hold good universally at all places, times, circumstances, and for all classes of humans.32 Of these fve, ahi ṃsā, coming as it does frst on the list, is the most important. When one is established in non-violence, he has no enemy and is no one’s enemy. In giving importance 183 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS to non-violence, the Yoga S ūtras seem to have assimilated the moral doctrine of Jainism. Although the extreme version of non-violence found in Jainism does not exist in the Yoga school, killing living beings and consequently meateating is absolutely prohibited for a yogi in the Yoga S ūtras. The remaining four yamas are geared toward it; for example, truth-telling signifes telling the truth that is useful to others as well as practice truth-telling in speech and deeds. The practice of these restraints not only prevents the arising of karmas but also contributes to the development of positive sa ṃsk āras. Whereas the yamas are restraints, the niyamas are positive and refer to places, times, and classes. They prescribe the cultivation of good habits. The niyamas are also fve in number: Sauca or cleanliness (both natural and spiritual), purifcation of the body by washing it, and purifcation of the mind involved in cultivating such positive thoughts and emotions as friendliness, kindness, etc.; santo ṣa or contentment (being content with what one has without too much trouble), tapas or asceticism (enduring cold and heat), sv ādhyāya or the study of religious scriptures (the study of religious books with uniform regularity), and Īśvara-pra ṇidh āna or contemplation of and surrender to Īśvara (God). The difference between the two practices, yama and niyama, i.e., between morality and religious practice, may be stated in the words of K. C. Bhattacharya thus: “Morality is universal as the negative externality of spirituality, religious practice is its positive particularity and internality, while super-religious yoga is its transcendent individual reality.”33 The next three steps constitute a process of spiritualizing the body. The disciples of ethical and religious practice have already prepared the ground and now the body so trained must be subjected to a direct spiritualization. One begins with āsana, the right posture, which is rather a spiritual pose of the body, “steady and pleasant” to be achieved by relaxation and by absorption in the infnite. Āsana spontaneously leads to the regulation of breath freely in accordance with the cosmic rhythm. There are many kinds of āsanas and these āsanas effectively keep the body free from all sorts of diseases, thereby keeping under check the factors that disturb citta and make it restless. Prescriptions regarding the body are important because they secure the health of the body and make it ft for prolonged concentration.34 Prāṇāyāma35 means breath regulation regarding the inhalation and exhalation. Here, the Yoga S ūtras prescribe suspension of breathing either after inhalation or before exhalation or retention of the breath for as long as one can hold it. It must be practiced under the guidance of a person who has expertise in it. Such exercises strengthen the heart and help one control his mind insofar as it is conducive to the steadiness of the body and mind. The longer the suspension of breath, the longer would be the state of concentration. The goal of pratyāhara36 is to cut the mind off from the external world. When sense organs are effectively controlled by the mind, then it is not disturbed by sounds, sights, etc. This state, though not impossible, is very diffcult to attain; it requires a resolute will and constant practice. 184 T H E YOGA DA R ŚA NA Now that the body is refned and spiritualized, the next three steps in the practice of yoga, which are constitutive of yoga proper, follow. Whereas the frst fve limbs are external in the sense that they are merely preparatory to the discipline of yoga, the last three are internal in the sense that they are constitutive of yoga. The last three—dh āra ṇā, dhyāna, and sam ādhi—involve “bodiless willing,” or rather spiritual willing. These three, when performed together, are known as “sa ṃyama”; they lead to insight.37 The sixth and the seventh, i.e., dh āra ṇā and dhyāna, are preparatory to the eighth, i.e., sam ādhi. In dh āra ṇā, one fxes the mind on a real position in space. An imagined object is placed in a position in space and is willingly visualized as being there. It is crucial to developing the ability to keep one’s attention fxed on one specifc object because it is the test of the ftness of the mind and signals that one is ready to enter the next higher stage, dhyāna, which is the contemplation of the object without any disturbance. The sense of remembering becomes an uninterrupted stream of willing and imagining. This series merges into an effortless sam ādhi, subjectivity completely withdraws itself so that the object alone shines. In the words of Yoga S ūtras, “sam ādhi occurs when the dhyāna shines as the object alone, and the mind is devoid of its own subjectivity.”38 The mind does not wander around any longer; it becomes one-pointed or ek āgra. Sam ādhi or concentration is the fnal step in the practice of yoga. In sam ādhi, all mental modifcations cease and there is no association with the external world; they become one. The Yoga school here makes a distinction between two kinds of sam ādhis: Samprajñ āta sam ādhi and asamprajñ āta sam ādhi. In samprajñ āta sam ādhi, the consciousness of the object is there; in asamprajñ āta sam ādhi, it is transcended. In samprajñ āta sam ādhi, the consciousness of puru ṣa fows through the natural mind; it has an objective support to focus upon. This sam ādhi has two substages: Savitarka and savich āra. In savitarka, citta’s focus is on a gross material object, e.g., the image of a deity, etc. In savich āra the gross object is replaced by its subtle equivalent, e.g., the tanm ātras. “Subtle” means “what is not perceptible by the senses.” To put it differently, in savitarka, the presented object predominates; in savich āra, the act of presentation predominates. In savitarka, the body comes to the forefront and the mind is fnitized; in savich āra the body drops out from consciousness and the act of apprehension becomes the focus, the pure self is grasped, there being no object. This self-knowledge gives rise to two additional forms of sam ādhi: S ānanda sam ādhi and sāsmit ā sam ādhi. In the former, there is the absorption in the sheer bliss of self-knowledge, and in the latter, the mere “I” awareness, the pure subject, rather than the subjective act, becomes the exclusive focus. Irrespective of how one classifes the four stages of samprajñ āta sam ādhi, the point that Yoga is trying to make is as follows: Samprajñ āta sam ādhi is ek āgra; in it, the focus is on the object of meditation and the object of meditation and meditation are fused, though the consciousness of the object remains. Asamprajñ āta sam ādhi is niruddha, and there is no consciousness of the object. 185 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS All mental modifcations cease to exist, and the self realizes its own essence as pure consciousness. One attains mok ṣa, the state of freedom from all suffering. Before concluding this section, I will make a few remarks about the bodymind relationship and the ordering of sam ādhis in the Yoga school. One wonders: What is the relation between body and mind in yoga? Yogic practice, to a large measure—both externally and internally—is bodily, physiological, breathing. This practice is supposed to have a wholesome infuence on the mind. Likewise, the mental practice of abhyāsa, vairāg ya, and dhyāna, is supposed to bring the body under the control of the mind; they mutually infuence each other. Given that both body and mind are the products of prak ṛti and are products of the varying proportions of the three gu ṇas—one can say that both are “natural,” and that neither is spiritual. To be “natural” is not to be construed as being “material.”39 Sāṁ khya and Yoga, which share a common metaphysics, are to be sure, not purely “materialistic.” Both may be said to be “naturalistic”; however, in both, prak ṛti is meant for the purpose of puru ṣa. Thus, in both, prak ṛti is ordered to serve the interests of puru ṣa. It would, therefore, be wrong to ascribe to yoga a mind-body identity theory. In prak ṛti, as in the body, there is a preponderance of the rajas and tamas, though sattva is not entirely lacking. In mind or buddhi, sattva predominates, thereby making it possible for the buddhi to know and to will or not to will, thereby making yogic practice possible. Thus, the body is “spiritualized” through cleanliness, āsana or posture, prāṇāyāma or breath control, and pratyāh āra or merging of the sense organs in the mind. Likewise, through the purely mental operation of dhyāna, the body is freed from the rajas and the tamas gu ṇas, it becomes shining and lustrous. Both make pure knowledge possible through the buddhi’s perfection. To sum up: The relationship between body and mind is complex; they cooperate and mutually infuence each other. IV Īśvara or God The Sāṁ khya, as is well known, has no place for Īśvara in its metaphysics. The world has no creator; it evolves spontaneously from prak ṛti, and, from a teleological perspective geared to the purposes of the puru ṣa. The Yoga school, on the other hand, accepts the existence of God on both the theoretical and practical grounds. It provides two arguments to prove the existence of God: (1) The Vedas and the Upaniṣads declare that there is a God, a supreme self. So, God exists because the foundational texts testify to its existence. (2) The law of continuity talks about the degrees, a lower limit, and the upper limit of things that we see in the world. Likewise, there are degrees of power and knowledge. Thus, there must be a being who possesses perfect power and knowledge, and that being is God. The Yoga S ūtras, however, introduce Īśvara in the context of the discussion of the practice of yoga. There are, to my knowledge, at least four contexts in which Īśvara appears. Devotion to Īśvara is an alternate route to sam ādhi.40 Commentators construe it as devotion to Īśvara is the best and the quickest way 186 T H E YOGA DA R ŚA NA to attain sam ādhi. The nature of Īśvara is explained as follows: He is a special puru ṣa, uncontaminated by the detriments to the practice of yoga, karma, the fruition of the karma, and by the sa ṁsk āras, or dispositions left by the karmas.41 The Yoga S ūtras also assert that Īśvara’s omniscience is unsurpassed.42 Much controversy surrounds the sense in which there are degrees of omniscience. The Yoga S ūtras argue that Īśvara is the teacher of the earlier generations and that he is not limited by time.43 The former statement means that he is the teacher of all teachers; the latter, that time belonging as it does to prak ṛti does not limit his being through devotion to him. The yogi comes to know his own true self or puru ṣa. Some of these themes are repeated in other chapters as well. The above makes it obvious that Patañjali accepts the existence of God, though his interest in God is only practical. From the theoretical-metaphysical perspective, he abides by the Sāṁ khya doctrines. He does not regard Īśvara as the creator of the universe; God is only a special kind of puru ṣa. God is the model of the highest perfection and knowledge. He is a perfect being, allpervading, omnipotent, omniscient, free from all defects. He does not bestow rewards or punishments and has nothing to do with the bondage and liberation of individual souls. The goal of human life is not union with God but rather the separation of prak ṛti from puru ṣa. V Concluding Remarks It should be clear that the practice of yoga is an active process of willing. Spiritual activity, in this system, construed as willing, is the goal if one wishes to attain freedom. The will, however, is the “will to not will,” i.e., the will to nivṛtti, not to pravṛtti.44 In Sāṁ khya, the willing is a process of knowing, while in the Yoga system, it is a process of willing to free oneself from the natural will to pleasure or enjoyment. Here we see an interesting difference between Yoga and Vedānta and Vaiṣnava theism. Vedānta, especially Advaita Vedānta, aims at knowledge, and Vaiṣnavism understands spiritual life as one of feeling; Yoga focuses on a life of willing not to will. One is struck by the Yoga S ūtras similarity with the Buddhist teachings. The Yoga S ūtras emphasize that worldly existence, especially existence in the body, is characterized by suffering, which is an important feature of Indian philosophies, especially of Buddhism. Yoga S ūtras categorically affrm that life is permeated by suffering,45 which includes the arising of pain when the pleasure passes away. The cause of suffering is also explained: The seer and that which is seen, i.e., the spirit and the material objects, are confused with one another.46 More specifcally, buddhi, a product of prak ṛti, is confused with puru ṣa. The knowable objects are constituted of the three gu ṇas and exist for the sake of puru ṣa’s purpose. Puru ṣa is the seer; it is pure consciousness. Suffering is overcome when the union of the buddhi and prak ṛti is dissolved, and puru ṣa is seen for what it is. Yoga, of course, is the means to accomplish this. Ignorance or avidyā is the cause of the seeming union of the puru ṣa and prak ṛti. This avidyā is destroyed by the true knowledge of the distinction between the two.47 187 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS But there is an important point of difference between the two: For the Buddha, a self is a union of fve impermanent skandhas; there is no substantial self; Yoga takes the unchanging eternal self to be changing natural processes. Patañjali’s main criticism of Buddhism concerns the doctrine of momentariness (k ṣanikavāda). Patañjali defends a realism regarding the existence of external objects in the world; they are not mental constructions.48 Like the Sarvā stivādins, he asserts that the past and the future exist in reality, the object and the mind are different,49 and the object is dependent neither on a single mind nor on many minds. What is self-luminous is not the mind; the mind is only an object. Only puru ṣa is self-illuminating. In view of the contemporary interest in the relation of yoga to Edmund Husserl’s thinking, I will highlight a few relevant points. First, both phenomenology and yoga seek to be descriptive sciences of experiences of different levels and types. Both avoid philosophy in the sense of system-building by speculative arguments. This alone creates the presumption that the two must be alike in many important respects; however, it must be noted that phenomenology restricts itself to perceptual and scientifc experiences, besides moral, aesthetic, and social; the Yoga school, however, goes beyond these and ascends to supernormal experiences. The central concern of phenomenology is the internal structure of experience. Ordinarily, this structure is construed as consciousness’ directedness to an object outside of it. But phenomenology brackets the object outside of consciousness, and consequently, is left with the object as belonging to the internal structure, i.e., the “meaning” or the “noema” of the experience. The method of epoch ē thus makes it possible for phenomenology to study descriptively the internal structure of all experiences. Yoga’s attitude towards intentionality is quite different; its goal is to restrain the outward movement of mental modifcations. Intentionality is thereby progressively conquered, and the self as pure consciousness comes to the forefront. In this respect, Yoga and Vedānta schools differ from phenomenology. They begin with empirical consciousness, and through a series of moves aim at reaching pure non-intentional consciousness. These systems of Indian philosophy do not take intentionality to be the defning feature of consciousness, which is self-luminous. What Yoga proceeds to decipher by the method of refective focusing, phenomenology proceeds to bring to light by the method of epoch ē. The yoga of Patañjali does not deny the world; its goal is to restrain the movement of the mental states toward the world. Phenomenology does the same thing by a method of refection and epoch ē. The yogin exclusively focuses upon an object, shutting off all other objects from its view. This is very close to the method of epoch ē; it is attained by a voluntary move. The phenomenologist, as is well known, proceeds through a series of epoch ē, the psychological, the phenomenological, and the transcendental, the last being the primary. A yogin goes through different stages of sam ādhi; he initially focuses on the gross object, then on the subtle constituents of that object, its essential structures, 188 T H E YOGA DA R ŚA NA leading to the focusing on the act of consciousness and the pure subject to the complete exclusion of any object, and fnally, on the pure non-objective selfluminosity of consciousness and reaching omniscience in the end. Another central theme of the Yoga school—which is of phenomenological signifcance—is the gradual spiritualization of the body, beginning with the appropriately relaxed and effortless posture and breath-control up until one reaches the complete indistinguishability of bodily and pure buddhi’s subjectivity. The body, initially perceived as sinful and dirty, becomes an effective means of willing not to will with cleansing, contentment, and ethical-religious practices. Phenomenology continues to focus on meanings (noemata), ideal contents of experience; Yoga, on the other hand, at some point in its progressive journey totally overcomes all verbal reference and meaning, language drops out, making it possible for the self-luminous consciousness to recede behind the object so that the epistemic gap between the object in itself and the perceived content, i.e., the perspectival character of perception is overcome. The object stands luminously in its totality, refected as it is in consciousness. Phenomenology has no inkling of this grasp of the total object and the consequent omniscience. Descriptive phenomenology becomes, in the Yoga school, a transformative phenomenology. The long, almost immemorial, practice of yoga, independent of and prior to the philosophical systems, has resulted in the concepts, possibilities, and achievements of yoga practice being sedimented in the Indian life-world so that not so much faith as recalling the possibilities actualized in the past that looms large before the Indian mind. Philosophy has tried to systematize the experiences whose memory is preserved in śrutis, epics, and poetry. Yoga has become a part of the Indian psyche. Also, every philosophical darśana with the exception of C ārvā ka has accepted the possibility of yoga in some form or the other. However, there is always room for further critical examination of actual achievements coupled with the hopes for the possibilities that always lie in such expectations. Study Questions 1. Explain the meaning of “yoga.” Discuss Patañjali’s defnition of “yoga” as “cittavṛttinirodha.” 2. What is a vṛtti (mental modifcation)? Explain the fve mental modifcations (cittavṛttis) elaborated in Patañjali’s Yoga S ūtras. 3. Critically discuss the fve affictions (kle śas) that are opposed to the practice of yoga. 4. Explain the fve levels of citta (cittabh ūmis) and the role the three gu ṇas play in these levels. 5. Elaborate on the eight limbs (a ṣṭāṇga) of Patañjali’s yoga. Do you agree with Patañjali’s yoga techniques for overcoming ignorance and attaining enlightenment? Argue for your position. 189 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS 6. Discuss the status of God in the Yoga school. Patañjali does not regard Īśvara as the creator of the universe; God is only a special kind of puru ṣa. Do you fnd this conception plausible? Give reasons for your answer. 7. Explain the Yoga concept of “citta.” How does it differ from the Buddhist concept of “citta”? Discuss some of the similarities and differences between the Yoga and the Buddhist philosophies. Which makes more sense to you, and why? 8. Comment on the following: “What Yoga proceeds to decipher by the method of refective focusing, phenomenology proceeds to bring to light by the method of epoch ē.” Do you agree that in the Yoga school, descriptive phenomenology becomes a transformative phenomenology? Argue pro or con. Suggested Readings For an excellent introduction, insightful translation, and commentary based on original sources, see Edwin F. Bryant, The Yoga S ūtras of Patañjali: A New Edition (New York: North Point Press, 2009); Gerald James Larson and Ram Shankar Bhattacarya (eds.), The Encyclopaedia of Indian Philosophies: Yoga: India’s Philosophy of Meditation (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 2011), to date, is the most comprehensive work on this school; it not only includes historical development, summaries of major texts and thinkers of the school, but also an analysis of the important concepts, and conceptual distinctions; and G. Feuerstein, The Philosophy of Classical Yoga (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1980) details key concepts of Yoga S ūtras and his The Yoga Tradition: Its History, Literature, Philosophy and Practice (Prescott, AZ: Hohm Press 1998) provides a thorough overview of the history, philosophy, and practice the Yoga school. It also includes translations of twenty Yoga works. 190 11 THE VA I Ś E Ṣ IK A DAR Ś A NA I Introduction The origin of the Vaiśeṣika school is uncertain; it is a very ancient school, most probably pre-Buddhist. Ka ṇā da or Ulū ka systematized the Vai śe ṣikas ūtras (VS), the only extant ancient text, which ante-dates most of the extant s ūtras.1 VS is the frst systematic work of this school. Not much is known about Ka ṇā da, and it is diffcult to ascertain with certainty when exactly he compiled it. The date of the VS ranges from somewhere between 200 BCE to the beginning of the CE, though it is very likely that some of the Vai śeṣika doctrines were formulated much earlier. Other important works of this school are Udayana’s Kira ṇāval ī and Lak ṣa ṇāval ī, and Vallabhā chā ry ā’s Nyāya L īl āvat ī. Pra śastapā da’s Pad ārthadharmasa ṅgraha provides an excellent exposition of the Vai śeṣika philosophy. The system embodies a naturalism which, since the beginnings of Indian thought, has opposed the mainstream non-naturalistic component of Indian thought. The school owes its name to recognizing the category of vi śe ṣa (particularity) as a necessary feature to account for the particulars of the world, e.g., atoms and souls, which are eternal. It accounts for and preserves “particularity,” despite recognizing many individuals. The objects which we experience in our everyday lives have parts and are non-eternal. As stated earlier, in the Indian thought one fnds two naturalistic theories of the origin of the empirical world. On one view, the world is a product of the ordered evolution from an original undifferentiated prak ṛti, the one becoming many, while on another, the world arises out of the atoms combining together in various ways which, in a limited sense, is many becoming the one. The Sāṁ khya represents the frst view and the Vaiśeṣika the second. Both schools, besides their naturalistic proclivities, propound a theory of the irreducibility of the self, argue for the plurality of selves, and recognize karma-rebirth-mok ṣa (kaivalya in Sāṁ khya). Vaiśeṣika represents a system of realism: It asserts the reality of objects independently of our perception of it. The Vaiśeṣika’s primary concern is ontology; it focuses on the enumeration of the ultimate constituents of the universe 191 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS and subordinates epistemology or the theory of knowledge and logic to ontology. It is pluralistic; in ontology, it reduces all things in the world or beyond to a minimum, i.e., to further irreducible kinds. On the Vaiśeṣika theory, the world in all its variety and complexity is constituted out of these irreducible entities. In this sense, it represents a grand intellectual adventure of ancient Indian mind. It is not surprising thus that the ideas of the Vaiśeṣika remain the basis of the Hindu physical sciences,2 just as the Sāṁ khya remains the basis of the Hindu medical science. The Vaiśeṣika and the Ny āya together form a conjoint system called “Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika.” Both subscribe to the view that the goal of human life is enlightenment, absolute cessation of pain and suffering. Both systems, however, differ on the number of the pram āṇas they accept; whereas the Nyāya accepts perception, inference, comparison, and verbal testimony, the Vaiśeṣika recognizes only two: Perception and inference. Again, whereas the Ny āya accepts sixteen categories ( pad ārthas), the Vai śeṣika recognizes only seven. The Nyāya takes over the Vaiśeṣika ontology and defends it from the opponent’s attacks using the canons of logical reasoning. I will discuss the pram āṇas, the conceptions of the self, bondage, and liberation, in the chapter on Nyāya and primarily focus on the ontological categories, i.e., pad ārthas, in this chapter. Fundamental Postulates 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 The Vaiśeṣika divides the ultimate constituents of the universe into seven categories (pad ārthas): Dravya (substance), gu ṇa (quality), karma (action), sām ānya (universal), vi śe ṣa (particularity), samavāya (inherence), and abh āva (negation). There are nine substances: Earth, water, fre, air, ether, time, space, soul, and manas (mind). First fve are material, and the last four are immaterial. Simple and eternal atoms constitute the fundamental structure of universe. There are twenty-four gu ṇas. These are color, taste, smell, touch, sound, number, size or magnitude, distinctness, conjunction, disjunction, remoteness, nearness, cognition, pleasure, pain, desire, hatred, effort, heaviness, fuidity, viscosity, dispositions, dharma, and adharma. Souls are eternal. Perception and inference are the only two pram āṇas. The goal of human life is mok ṣa, which is absolute cessation of pain and suffering. 192 T H E VA I Ś E Ṣ I K A D A R Ś A N A II The Pad ārthas (Categories) Pad ārthas are “categories” of the Vaiśeṣika school. Etymologically, “pad ārtha” means “the meaning or the referent” (artha) of words (pada). So, by “pad ārtha,” the Vaiśeṣika means “all reals” or “all objects that belong to the world.” It is an object that can be thought of as well as named.3 If this etymology is scrupulously followed, then it would imply that any meaning of a word is a pad ārtha which however is not the case. The word “pitcher” signifes a pitcher, but a “pitcher” is not a pad ārtha. Likewise, “red” means “the color red,” but red is not a pad ārtha; it is a quality. In the context of metaphysics, a “pad ārtha” signifes the general class under which referents of words fall, a class that is not included in any other class. Pad ārthas are the highest genera of entities. One generally compares the Vaiśeṣika categories to the categories of Aristotle and Kant. Whereas Aristotle’s list is a haphazard group of very general predicates of things, the Kantian list is systematic; it is drawn from the logical forms of judgment and traced to the forms of the faculty of “understanding,” and so is subjective in origin. The origin of the Vaiśeṣika list is not known. There is no principled deduction, though later commentators defend the list by critiquing it, suggesting additions and subtractions to demonstrate that the list is almost complete. All objects that the words denote are of two kinds: Bh āva and abh āva, being and non-being respectively. Being includes all positive realities, e.g., physical objects, minds, souls, etc., and non-being includes non-existence. There are six kinds of positive realities and one negative pad ārtha. Thus, the Vaiśeṣika list (which appears to have evolved slowly) has seven categories: (1) Dravya (substance), (2) gu ṇa (quality), (3) karma (action), (4) sām ānya (universal), (5) vi śe ṣa (particularity), (6) samavāya (inherence), and (7) abh āva (negation).4 These seven categories will be the primary focus of this chapter. Dravya (Substance) “Dravya” is usually translated as “substance.” But this translation does not quite capture the meaning of “dravya” of the Vai śeṣika school. The Aristotelian or the Kantian “substance” has the sense of permanence amid changes; the Vai śeṣika dravya cannot be so construed. Defnitionally, it is the locus of qualities and actions (i.e., of the next two pad ārthas). A gu ṇa or quality and an action can only be in a dravya. A quality does not foat around by itself. Any quality, say, “red,” proximately resides, e.g., in a red fower. A dravya is the locus (āśraya) not only of qualities but also of actions. 5 Such universal entities as “redness” reside in red, and the latter in a red object. In fact, either proximately or mediately all entities belonging to all different categories mentioned above reside in a dravya. Thus, in the Vaiseṣika ontology, dravya occupies a prominent place. The recognition of its primacy captures our naive realistic intuitions that things in the world have an important place in our picture of the world. It 193 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS also captures an important feature of the Sanskrit as well as of the IndoEuropean languages that nouns occupy a prominent place in a sentence.6 In the Sanskrit sentence, “aya ṃ ghataḥ” (“this is a pitcher”), a substance is in the predicate place. Besides, a Sanskrit sentence does not always conform to the subject-predicate pattern. Again, it is worth remembering that Aristotelian, Kantian, and Lockean, notions of substance as a permanent substratum underlying changes do not exist in the Vaiśeṣika school. For these reasons, it seems more advisable to render “dravya” simply as “thing,” the German word “Ding.” Of all the categories, dravya is the most important, for there is a sense in which the remaining categories—or, rather, the instances of all of them—can only be in a “dravya.” Anticipating our exposition of the other categories, we can say, such entities as a quality, an action, a universal, the relation of inherence, particularity, and a negation (or absence) can have their being only in a thing. Let me give an example. Consider a thing like a brown pitcher I see before me: Given that the pitcher is brown, it has the quality brown; when the pitcher moves, it becomes the locus of an action; it is the locus of the universal “pitcherness”; a universal is common to all instances of a particular class, and it is the particularity of the individual instance of the universal that differentiates one pitcher from other pitchers; the brown color that inheres in the pitcher instantiates the universal “brownness”; and it is also the locus of negation or absence as in “the pitcher is not a glass.” Thus, the entire set of Vaiśeṣika categories may be regarded as an elaborate ontological analysis of the thing we are familiar with: In this case, a “pitcher.” Everything in the world is reducible to nine dravyas or things, viz., earth, water, fre, air, ether, space, time, soul, and manas (mind).7 The frst fve are material, and the last four non-material substances; atoms of these nine substances are eternal. Each of the frst fve substances possesses a unique quality, which makes the substance what it is.8 Smell is the unique quality of earth, taste of water, color of fre, touch of air, and sound of ether. To say that each of these substances possesses a unique quality does not amount to saying that it does not possess other qualities, but rather that the unique quality of a substance is what distinguishes it from other substances. The frst four are knowable by outer perception. The substances of earth, water, fre, and air are eternal and non-eternal. The atoms of these four substances are partless and eternal. As partless, they are neither produced nor destroyed. All other objects made by the combination of atoms are non-eternal; they are subject to origination as well as destruction. Earth, water, fre, and air atoms combine to form composite objects; at frst, two atoms combine to form a dyad, a combination of three is a “triad,” etc. In this evolutionary process, there is no talk of the frst creation of the world, because the process of creation and destruction of the world is beginningless. Destruction precedes each creation, and creation follows each destruction. Atoms lack motion, and the will of God imparts motion to atoms. It is obvious that the Vaiśeṣika atomism is different from the Greek atomism on several key points; here, I will note only two. First, the Vaiśeṣika 194 T H E VA I Ś E Ṣ I K A D A R Ś A N A atoms differ in both quantity and quality, whereas the Greek atoms differ only in quantity; they are devoid of qualities. So, they are qualitatively alike, but distinct quantitatively and numerically. According to Leucippus and Democritus, there are an infnite number of indivisible units called “atoms.” These atoms are imperceptible; they differ in size and shape, but have no quality save those of solidity and impenetrability. Consequently, observed differences in the qualities of objects are due to the differences in the number and confguration of their constituent atoms. Second, whereas the Vaiśeṣika atoms lack motion and need an agent to set them in motion, the Greek atoms do not need an agent to set them in motion. The Greek atoms exist in a state of constant motion. Greek atomism by making motion inherent in atoms seeks to explain the evolution of the world in purely mechanical terms. The ffth substance is ether. It is the substratum of the quality of sound. It is one, because there is no difference in its distinguishing mark, i.e., sound.9 Ether, having the largest dimension, is all pervasive and indivisible. 10 It is non-perceptible; we infer the existence of ether from the perception of the quality of sound. Ether is the medium through which sounds travel and reach the senses. Space and time, like ether and atoms, are imperceptible, eternal, and all-pervading substances;11 we infer the existence of space and time. We infer the existence of space from our cognitions of locations, directions, “there,” “here,” “east,” “west” etc.; we infer time from our cognitions of temporal modes: The past, the present, and the future. Space and time are partless and indivisible; however, we speak of them as having parts and divisions.12 The eighth dravya, namely, soul, is the “substratum of knowledge.”13 It is an eternal, all-pervading, conscious substance, but consciousness is not an essential quality of the soul. It acquires consciousness when it associates with a body. There are two kinds of souls: The individual soul and the supreme soul. Whereas the individual souls, being different in different bodies, are many, the supreme soul (God) is one; it is the creator of the world. The existence of the supreme soul as the creator of the world is known by inference. Individual souls are known by internal perceptions. Such statements as “I am happy,” “I am sad” testify to the existence of individual souls. The “I” directly refers to my soul, and what is being perceived is not the pure soul, but the soul as qualifed by the quality of happiness or pain.14 If a thing is not perceived, it is because all the conditions of its perception are not satisfed. Even very small things, e.g., atoms, though not perceivable by us, are objects of a special perception to a yogi in yogaja pratyak ṣa.15 The fnal dravya is “manas” without which nothing would be known. Manas, the inner sense, is unperceivable, being atomic in size. Our experiences testify to the existence of the mind. In deep sleep, the manas is not in contact with the sense organ and the sense organs are not in contact with the object; as a result, we do not perceive anything, which demonstrates that the active attention of some sense organ is necessary for a cognition to arise. Manas is atomic, partless, and eternal.16 195 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS The Vaiśeṣika argues that if the manas were not of an atomic size, there would be simultaneous contact of its different parts with many senses leading to many different perceptions at the same time, which, however, is not the case. It is through the manas that we directly perceive internal objects, e.g., cognitions, pleasure, pain, etc. Manas is also involved in the perception of external objects. For example, the contact of the sense organs with the object is a necessary but not a suffcient condition to produce a perceptual cognition; a contact between the manas and the sense organ is required. So, manas cannot directly perceive external objects; it acts as a link between external objects and the self.17 It is important to note that many Indian schools, e.g., the Buddhists and the Sāṁ khya, do not accord primary ontological status to “dravya.” They reject things as a conglomeration of qualities, and then move on to regard each quality as a constantly changing process. For Vaiśeṣika, such a position runs contrary to our everyday realistic intuitions. To perceive a quality is to perceive it as belonging to a thing. One never simply sees a color, but always sees a colored thing. The dravya therefore, according to Vaiśeṣika, is not a Lockean unperceived substratum nor unperceivable “I know not what,” but something we perceive along with its qualities. The Vaiśeṣika claims this list to be complete, and, by way of disputations with other schools that add to or subtract from the list, undertakes to defend this list. The great medieval Naiyāyika Raghunāth Śiroma ṇī, for example, reduced the three, viz., ether, space, and time, to God’s nature. He also did not regard manas to be a separate dravya—thereby reducing all dravyas to fve. It is worth noting that with this classifcation of dravya into nine, we are moving away from the ontological and coming a step, as it were, closer to the ontic discourse (using Heidegger’s terminology). While this sub-classifcatory scheme is ambiguously perched between the ontological scheme of the seven categories and the innumerable things of the world, the task of philosophy is to connect the two. No Western philosopher (including Aristotle and Kant) has provided such a sub-classifcation. Guṇa (Quality) The Vaiśeṣikas consider the “gu ṇas” to be qualities, which do not exist independently of a substance in which they inhere. Qualities can be conceived, thought, and named. They are static, non-eternal, and cannot exist by themselves. Additionally, they are not simply things; they are always qualifed as being such and such. Yet the two, dravyas and gu ṇas, though inseparable, are ontologically different. The thesis—that a thing and its qualities being inseparable must be non-different—is rejected on the basis that (a) the color of a pitcher resides in the pitcher, while the pitcher has its being in its constituent parts each of which does not have that color, and (b) if we take them to be non-different, then it would give rise to such statements as “this color is a pitcher,” which is absurd. 196 T H E VA I Ś E Ṣ I K A D A R Ś A N A Since, on the Vaiśeṣika theory, qualities reside in a substance, by defnition, a quality cannot itself possess another quality. What qualifes, and so belongs to this piece of paper, in “this paper is red” is red, but not redness. A quality belongs to a substance. There is no universal gu ṇa (gu ṇaness), nor a universal substance (substanceness). A gu ṇa cannot move from one place to another, a substance can and does, which explains why a knowledge, being a gu ṇa of the self, is not an action. It also does not have parts, though produced by the causes. A substance alone has parts. A quality, then, we can say, in itself is qualityless (nirgu ṇa), actionless (ni ṣkriya), and partless (niravayava). But qualities belong to partless substances, e.g., self. It is worth remembering here that in the Vaiśeṣika system, substances and qualities are ontologically different entities. Unlike substances, qualities are always dependent; they are in substances. An action and a quality are two different aspects of a substance—the former its changing aspects and the latter its unchanging aspects.18 Ka ṇāda lists twenty-four gu ṇas. These are (1) color, (2) taste, (3) smell, (4) touch, (5) sound, (6) number, (7) size or magnitude, (8) distinctness, (9) conjunction, (10) disjunction, (11) remoteness, (12) nearness, (13) cognition, (14) pleasure, (15) pain, (16) desire, (17) hatred, (18) effort, (19) heaviness, (20) fuidity, (21) viscosity, (22) dispositions, (23) dharma, and (24) adharma.19 In this list of qualities, some are important than others: Such qualities of the self as pleasure, pain, desire, hatred, effort, dharma, adharma, and dispositions (sa ṃsk āra) are more important than the others. I will detail these little later. I will begin with brief remarks about the nature of twenty-four qualities. In the list of twenty-four qualities, 20 some belong to material substances, some others to immaterial substances, and still others to both material and immaterial substances, which provides a rationale for the list of twenty-four. For example, color, taste, smell, touch, and fuidity reside in material substances; cognition, pleasure, pain, desire, hatred, and dispositions reside only in non-material substances; and number, size or magnitude, distinctness, conjunction, disjunction, heaviness, fuidity and viscosity reside in both material and non-material substances. Again, some qualities are cognized by one outer sense, e.g., color, taste, smell, touch, and sound; some are cognized by two senses (the visual and the tactual), e.g., number, size or magnitude, distinctness, conjunction, disjunction, remoteness, nearness, fuidity, and viscosity. An important Vaiśeṣika doctrine is that number is a quality of substances. All things whatsoever can be counted. It is defned as the uncommon cause of “counting.” Number really inheres in, or belongs to, more than one thing held together by a special act of mind—thus, to a collection or a set. Since number is a gu ṇa of substances, and since a gu ṇa cannot belong to other gu ṇas, number does not belong to qualities. Such modern logicians as Raghunātha Śiroma ṇ i reject this thesis on the ground that one can also count three qualities, so number can belong to qualities as well. It is also worth noting that since number belongs to collections or sets, and since mathematicians of that time did not have the idea of a unit set, the Vaiśeṣikas regard numbers to begin with the number “two”; the “one” was not a number. 197 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS Parim āṇa, translated variously as “quantity,” “size,” “magnitude,” etc., is either atomic or large, either short or long, and either eternal or non-eternal. Non-eternal size is due to either number, or the size of component parts, or decay.21 P ṛthaktva or distinctness (separateness) is the cause of determinations like “this is different from that.”22 The judgment “a jar is not a glass” is about the mutual difference of the two, but the judgment “this is other than that” is about their being separate. One could say this is a distinction without difference. An important gu ṇa is conjunction or contact (sa ṃyoga) when two things which were not in contact come into contact (such as my two palms when they are made to touch each other), and a contact arises between them.23 Anna ṃbhaṭṭ a defnes sa ṃyoga as a contact between two things that were initially apart. Accordingly, no contact exists between entities that are all-pervasive and have never been apart from each other.24 It is important to remember that the system admits only one genuine relation i.e., inherence or samavāya, listed as an additional category. The opposite of contact is disjunction or separation (vibh āga). Two conjoined things may be separated, such as when my two palms held in contact are made separate.25 Otherness (and its opposite) denotes farness (and nearness), both in space and in time.26 So, they can be translated as well into “remoteness” (and “nearness”). When construed temporally, they signify earlier and later.27 Heaviness (gurutva) is defned as the special cause of “falling down.” It exists in two substances viz., in the earth and water, and belongs to the whole as well as to the parts. It is the cause of the falling of bodies. Fluidity or dravyatva is self-explanatory; it is the cause of the fowing, for example, of water, milk, and so on. Heaviness and fuidity are perceptible by two sense organs.28 Viscosity exclusively belongs to water; it is the cause of the different particles of matter sticking together to form the shape of a lump or a ball. Farness, nearness, heaviness, fuidity, and viscosity are generic qualities, to name only a few.29 I will now turn my attention to the qualities of the self. Pleasure (sukha) and pain (dukkha) arise in the self because of knowledge— specifcally, on account of the contact between the self, sense organs, objects, and the mind (manas). Pleasure and pain are two different qualities of the self—the one not reducible to the absence of the other—both are positive qualities and different from knowledge. The object of pleasure is what is desired and favorable, whereas the object of pain is not desired and unfavorable. We want pleasurable experiences to continue and wish painful experiences to end. Various kinds of pleasure and pain are distinguished: Those that are caused by memory (of the objects of the past), by imagination (of the objects of the future) and, in the case of persons who have attained knowledge of the truth (without any objects). Pain arises from the objects or experiences contrary to what the experiencer desires; otherwise stated, pain is that which a person does not desire and wishes it to end after it arises. Desire arises by the thought of the enjoyment of objects, contrary conditions give rise to jealousy. Both may also arise from strong dispositions or 198 T H E VA I Ś E Ṣ I K A D A R Ś A N A habitualities, produced by the objects that are dear, by the objects that cause pain, and from appropriate adṛṣṭa or “unseen” potencies that have arisen in the self. A fourth kind of desire (and its opposite) arises from the intrinsic nature of the natural kinds to which an animal belongs: Thus, humans desire food, other animals desire grass or plants to eat, etc. Later authors classify desires into those whose objects are the intended results of actions, those whose objects are the means to reach the results, and those whose objects are actions themselves. Dve ṣa (hatred or jealousy) is what burns inside, causes constant remembrance of the object, or the means for reaching it, and the thought of accomplishing it, causes the needed effort and produces such qualities in the self as dharma and adharma. Hatred is either simple anger or produces such deformations in the bodily expressions as vices, anger, impatience, and unforgiving feelings do. Prayatna or effort appears last among the qualities of the self, often described as “enthusiasm” (utsāha) to do something which we all immediately experience within ourselves. The efforts caused by desire are “pravṛtti,” those caused by hatred are “nivṛtti”; both pravṛtti and nivṛtti are different from the efforts (e.g., breathing and other intra-bodily process) that are necessary to sustain life. Two unseen (adṛṣṭa) qualities accruing to the soul are dharma and adharma, in the sense of moral virtue and its opposite respectively. Given that Ka ṇāda at the outset explains “dharma” testifes to its importance for the Vaiśeṣika school.30 He states that everything else, i.e., all other entities, are for the purpose of leading up to “dharma.” He further explains “dharma” as that which leads to fourishing (abhyudaya) in life and the highest goal in the next; the proof of “dharma,” we are informed, exists in the Vedas.31 Dharma is brought about by the performance of actions which are recommended; in itself, it is a gu ṇa of the self. It is one of the specifc qualities of the self, i.e., it cannot accrue to anything else. It is not a gu ṇa of the buddhi (like in Sāṁ khya); it can only exist in a self. It is created by the conjunction of the self with the inner sense, appropriate resolutions, and performance of recommended actions. Adharma is its opposite. Both dharma and adharma are known by a common name “adṛṣṭa” or “unseen”—a word often used in the Vaiśeṣika works, but not in the Gautama’s Nyāyas ūtras or any other Nyāya commentary. Sa ṃsk āras or dispositions (of the past experiences) is a special quality of the self, which is introduced as the cause of memory and recognition. It is this disposition that is either awakened or strengthened (or weakened) by appropriate conditions. Without positing such an unseen quality in the self, a past cognition (long since gone out of existence) could not be remembered. Habit strengthens dispositions, a special effort (e.g., to experience unseen entities) may cause especially powerful dispositions. The Vaiśeṣika recognizes three varieties of sa ṃsk āra: (1) Speed (vega) that keeps things in motion, (2) mental impressions (bh āvan ā) that helps us to remember and recognize, and (3) elasticity (sthitisth āpakatva) which helps a thing move to regain the equilibrium when it is disturbed, e.g., a string of rubber. It is worth noting that these dispositions do 199 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS not belong to the self alone; they also belong to other things as well. It is not entirely clear why the Vaiśeṣika brings dispositions accruing to the self under the same genus as velocity of moving material things and elasticity. A moving thing has the momentum in it to move. An elastic thing, when stretched, has the power, tendency, or built-in disposition to contract. Thus, one could argue that elasticity and momentum are not ordinary qualities, but rather dispositions to behave in certain ways. Karma (Action) The next category is karma or action. Unlike the usages of “karma” in other systems, karma signifes the movement of a thing from one place to another. It is different from the voluntary actions done with subjective desires to do as well as effort, which is one of the gu ṇas. Karma is simple displacement of positions in space, and it is with the help of karma that one thing reaches another place. It therefore does not belong to quality, which does not move. While quality is a passive attribute, karma is dynamic. The Vaiśeṣika recognizes fve kinds of action: Throwing upward, throwing downward, contraction, expansion, and movement.32 Among substances, all-pervasive ones cannot possess motion; thus, the self, being all-pervasive, cannot move and cannot act. With “substance,” “quality,” and “action,” we have circumscribed the basic core of the world according to Vaiśeṣika. The world at its core consists of qualities and particular objects in motion. But these three by themselves do not suffce to yield a complete ontology. We need: 1 2 3 4 some feature that substances, qualities, and actions have in common; an account of the incurable particularity or uniqueness of things; a basic relation that ties these entities together; and some category that accounts for the pluralistic realism of the system. Considering the above, let us now turn to the next four categories that form the outer layer of the categorical structure of the world in this system. S ām ānya (Universal) For the Nyāya-Vaiśeṣikas, universals, variously called “sām ānya” or “ jāti,” are entities which though one and eternal inhere in many. A universal, for example, “pitcherness,” is eternal (nitya), and inheres in many particular instances (aneka samveta).33 Pitcherness, they argue, is present in all pitchers, and it would persist even if all pitchers were to be destroyed. When there is only one instance of a thing, its distinguishing feature is not a universal, for example, ether. Nyāya-Vaiśeṣikas hold that the universals are real entities, which are not dependent upon the human mind. They advocate a realism regarding universals, which many realists in the Western world embraced beginning with 200 T H E VA I Ś E Ṣ I K A D A R Ś A N A Plato. However, more akin to Aristotle, the Vaiśeṣika took universals to be natural kinds such as “cowness” and “redness.” Particulars instantiating a universal come and go, but neither a particular coming into being nor its going out of existence makes any difference to the being of a universal in which they inhere. The manifestation or the lack of manifestation does not affect the being of a universal, because its being is eternal. Universals account for an infnite number of particulars that are alike, though otherwise different. Universals belong to substances as well as to qualities and actions, as do cowness, redness, and falling-ness respectively. If the instantiating particular is perceived, then the instantiated universal is also perceived, and it is perceived by the same sense organ as the particular. If a specifc sweet thing, e.g., sugar, is apprehended by taste, then sweetness is also apprehended by taste. It is because of the universal that we designate different instantiations of one particular by the same name; however, unlike many Western realists, the Vaiśeṣika does not believe that the universal “cowness” is the meaning of the word “cow.” The Vaiśeṣika argues that if that were the case, then the sentence “bring a cow” would mean “bring cowness,” which is absurd; it rather means a particular that is characterized by the appropriate universal, i.e., a cow characterized by cowness in this case. The Vaiśeṣika distinguished between three orders of universals: The parā or the highest, the aparā or the lowest, and the parāparā or the middle. Satt ā or existence is the highest, and belongs to all substances, qualities, and actions, “cowness” is of the lowest order belonging only to cows, while “substanceness” is of the middle rank belonging as it does to all the substances.34 Later commentators, led by such Naiyāyikas as Uddyotakara and Udayana, introduced “ jātibādhakas,” i.e., “the features which rule out the being of a universal.” Of the various defects discussed, I will discuss only one that is known as sāṅkarya.35 Such a defect exists when two mutually exclusive characteristics are present in the same substratum. For example, the characteristic of being an element is common to the fve elements—earth, water, fre, air, and ether; and the character of moving is present in earth, water, fre, air, and mind. Thus, both (element-ness and moving-ness) have earth, water, fre, and air in common. However, the character of being an element applies only to ether and not to mind, and the character of moving-ness applies to mind and not to ether. Therefore, if the “element-ness” is taken to be a universal, it will also apply to the four elements (earth, water, fre, and air which have moving-ness); the element-ness will coincide with moving-ness and will also apply to mind, and moving-ness will also apply to ether. That is why characteristics with partially overlapping denotations are not logical universals. Finally, if there is only one instance of a kind, adding an appropriate suffx to its name does not name a universal. Space being one, space-ness (āk āśatva) is not a universal. Space-ness, therefore, is merely a distinguishing characteristic (upādhi), and not a logical universal. Finally, universals also cannot belong to a universal: “Cowness-ness” is not a universal. There are many such cases where an abstract noun does not designate a universal. 201 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS Before proceeding further, let me underscore an important distinction, i.e., the distinction between a jāti and a upādhi, which plays a very important role in the Vaiśeṣika ontology.36 It clearly brings out the Vaiśeṣika conception of universals as a real, eternal, natural class essences existing in the objective world. A universal is a simple pad ārtha and it cannot be analyzed into other attributes, properties, components, and so on, which explains why a general term, for example, “horse,” stands for a universal, but a term like “black horse” does not. “A black horse” represents a complex of properties and does not imply the existence of an additional ontologically distinct entity over and above the blackness. In other words, the property of being a black horse is not over and above the blackness, and, therefore, is not reducible to it. The Advaitins reject the Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika category of universal. Apart from the brahman, nothing is eternal for them. Such universals as “pitcherness,” “cowness,” etc., they argue, are the sum-total of the characteristics of a pitcher, cow, etc., which distinguishes them from other objects.37 The universals of the pitchers, tables, etc., are not created afresh each time the pitchers, tables, etc., are created; likewise, the universals of the cows, etc., are not created afresh each time the cows, etc., are born. Individual substances, qualities, and actions are created and born; their universal essences, however, are not created and born. Believing that only particulars are real, and that they too come and go, the Buddhists held that there is no universal, and that all classifcations are introduced by language. The idea of a “universal” or “sameness” arises because of their being known by the same name. Only the name is general, which does not stand for any positive class essence. We call a class of animals “horse,” not because it possesses a common essence called “horseness,” but because they are different from all other animals that are not horses. Accordingly, the Buddhists argue that there is no such thing as a universal or a class concept; there are only particular objects of experience. Eventually, this account developed into the apoha theory, which held that the word “horseness” means “not-being-anon-horse.” A particular horse therefore means a not-non-horse. There is no real universal, a universal is simply a name with a negative connotation. The Buddhist apoha theory is a sort of nominalism. The Nyāya-Vaiśeṣikas subscribe to realism; they hold that both, particulars and universals, are independently real. They argue that without real universals, the world would consist of numberless transient particulars; it would not be the ordered distinct totality it is, and the use of language to describe the world would not be possible. So, they totally reject the Buddhist position that particulars alone are real. Vi śe ṣa (Particularity)38 Things are experienced not only as being alike; they are also perceived as being different. Even when they share the same qualities, they are distinct, e.g., though all cows have cowness, one cow is different from another cow. Vi śe ṣa is an entity, again a real entity, which accounts for this ultimate distinctness of 202 T H E VA I Ś E Ṣ I K A D A R Ś A N A individuals. The use of such indexicals as “this” or “that” does not explain individuality, but presupposes it. Therefore, we need a new category to explain individuality of entities. The Vaiśeṣika argues that a quality (or gu ṇa) of an individual thing cannot explain vi śe ṣa or particularity. Two things may have all the same qualities, e.g., twins, but they still are distinct. Could each one’s distinctness be due to the stuff it is made of, its “matter” (a position which Aristotle held)? But then, we are led to ask, what distinguishes the stuff of the one from the stuff of the other identical twin? We may ask, what distinguishes one atom from another? The Vaiśeṣika answers as follows: Each, otherwise non-distinguishable partless particular, possesses its own particularity; it is a real entity. The particularity of the wholes is accounted for by the particularities of its parts, but when we come to further partless entities the same explanation will not work; we have to stop somewhere in order to avoid an infnite regress and recognize a new real feature, its own particularity, only for individuals that do not possess parts. Each atom (also each soul) has its own particularity. Therefore, the Vaiśeṣikas argue that particularity is the unique individuality of the eternal substances, e.g., space, time, ether, minds, souls, and atoms of earth, water, fre, and air.39 It is important to remember that “particularity” is not a universal feature of distinct particulars. Ordinary objects of the world, for example, pitchers, tables, and chairs, are constituted of parts, and so do not require particularity to explain them. Particularity is needed to explain the differences among the partless eternal substances. The particularity of an atom or of a soul is not perceived; it is inferred. Furthermore, to regard particularity as a universal would be self-contradictory, it would contradict the very sense of “particularity.” Samavāya (Inherence) The one genuine relation which the Vaiśeṣika recognizes and admits as a distinct category is samavāya, often translated as “inherence.” Etymologically, “samavāya” means “the act of coming together closely”; it therefore denotes a kind of “intimate union” between two things that are thereby rendered inseparable in such a way that they cannot be separated without themselves being destroyed. Anna ṃbhaṭṭ a defnes samavāya as “a permanent connection existing between two things that are found inseparable.”40 By virtue of this relation, such different things as substance and its qualities (e.g., a fower and its color red), a particular and the universal it instantiates (e.g., a cow and cowness), a substance and its action (a body and its motion), a whole and its parts (e.g., a cloth and the threads constituting it) become unifed and represent an inseparable whole (ayutasiddha). Samavāya is an eternal relation. Excepting the case of a whole and its constituent parts, the relation holds good between entities belonging to two different categories. It also holds good between an ultimate, partless, particular and its particularity. In the case of a blue fower, the fower is inseparable from its blue color; one could as well say that blue particular is 203 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS inseparable from the fower whose blue it is. In the case of a cow and its cowness, the cow will die but when the cow is dead and no more, cowness will be there instantiated in other cows. There is a one-sided inseparability between the terms among whom this relation holds good. Thus, this relation is the same no matter what its relata are; it thus behaves like a universal. Śa ṃ kara rejects the relation of samavāya. He argues that if the relation of samavāya is needed to unite two different objects, then samavāya itself, being different from both of them, would need another samavāya, and so on ad infnitum.41 The Vaiśeṣikas argue that one cannot ask how the relation of inherence is related to the terms. Positing another relation between a relatum and the relation would only lead to an infnite regress, so it is more economical to recognize inherence to be a self-relating relation, and, in that sense, it is a genuine relation. Conjunction, by contrast, is not a self-relating relation. Additionally, it is a quality and is related to the conjuncts by inherence. Inherence is not conjunction: (1) because the members of this relationship are inseparably connected; (2) because this relationship is not caused by the action of any one of the members related; (3) because it is not found to end with the disjunction of the members; and (4) it is found subsisting only between the container and the contained.42 Inherence is a sort of ontological glue, which makes it possible for the entities to be unifed, despite the categorical multiplicity. But it glues entities from different categories within limits; it does not weld all things in the world into one large thing, rather unifes different entities that constitute one thing such as a white cow or a blue fower. We perceive the relation when we perceive the relata, as in the case of the blue color and a substance fower; we do not perceive the relation obtaining between an atom and its atomic size. Abh āva (Negation or Non-existence)43 Because all knowledge points to an object that is necessarily real and independent, the knowledge of negation implies its existence apart from that knowledge. In other words, the absence of an object is different from the knowledge of its absence. The Naiy āyikas maintain that negation (abh āva) is always of a real negation in a real locus. There is no such thing as pure or bare negation. Both presence and absence are objective facts. Since Vaiśeṣika is a pluralist and a realist, it admits many different reals, each different from the other. Of such fnite things as this blue fower, it holds good that if it is here and now, it is not, at the same time, there and now; if it is blue, it is also not red. The Vaiśeṣika therefore, for a complete theory or description of the world, needs only one more type of entity, besides those discussed so far, namely, “negation.” The judgments “A is not B,” “A is not in B,” and “A does not 204 T H E VA I Ś E Ṣ I K A D A R Ś A N A possess B-ness” affrm real negations, and these must articulate reality quite independently of any subjective point of view. Negation, according to the Vaiśeṣika, is an objectively real constituent of the world. Now, as the above examples demonstrate, “negation” is of many different kinds,44 and we can here lay down a broad typology of them in the fgure given below, and under each heading I will give within brackets the appropriate linguistic articulation for it. Negation 1. Absence (“A is not in B”) 3. Prior nonexistence (“A will be”) 2. Mutual non-existence) (“A is not B”) 4. Consequent non-existence (“A is no more”) 5. Absolute non-existence (“A is not here now”) Concrete Examples 1 2 3 4 5 There is no jar on the foor. A pitcher is not a jar. The pitcher is not yet made; it is not but will be. The pitcher is destroyed; it was but is no more. There is no elephant in this room. Let me elaborate these fve negations. In #1, there is the absence or non-existence of something in something else, e.g., “S is not in P.” It is the absence of a connection between two entities; its opposite is their connection. It is of three kinds: Antecedent non-existence, consequent or subsequent non-existence, and absolute non-existence. Antecedent or prior non-existence (#3) is the non-existence of a thing prior to its production, e.g., the non-existence of the house in the bricks, the nonexistence of a pitcher in the clay, the non-existence of a ring in a nugget of gold, etc. Anna ṁbhaṭṭ a defnes prāgabh āva as that “which is without a beginning” (an ādi) but “has an end” (santa); it “exists before the production of an effect.”45 This non-existence has no beginning but has an end, because as soon as the house is built the non-existence of the house in the bricks, pitcher in the clay, a ring in a nugget of gold, comes to an end. Subsequent or consequent non-existence (#4) is the non-existence of a thing on account of its destruction. A house after it is built may be demolished. It has a beginning but no end.46 The non-existence of the house begins when it is 205 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS demolished or burned; however, this non-existence cannot be ended because one cannot bring the same house into existence. Absolute non-existence (#5) is the non-existence of a connection between two things for all times—the past, the present, and the future. Anna ṁbhaṭṭ a explains absolute existence (atyant ābh āva) as that absence “which abides through the three modes of time” (traik ālika) and “the facthood of whose negatum” ( pratiyogit ā) is specifed (avachinna) by a “relation” (sa ṁsarga); e.g., “There is no pot [pitcher] on the ground.”47 It neither has a beginning nor an end. In other words, it is both beginningless and endless. For example, there is absence of horns in a hare for all times—the past, the present, and the future. Finally, the mutual non-existence (#2) is the non-existence of one thing as another, e.g., “S is not P.” Two objects, which are different from each other, mutually exclude each other. The mutual non-existence, like absolute nonexistence, is also beginningless and endless. However, there is an important difference between the two. Whereas in the absolute non-existence there are actual material objects, e.g., hare and horn and a negation of the relationship between the two, mutual non-existence is only a logical negation between two things that may not be actual. For example, “a red river is not a blue river” is true, though there is no red and no blue river.48 Those schools of Indian philosophy that accept abh āva or non-existence differ regarding the question of its apprehension. How is abh āva or non-existence apprehended? According to the Bhāṭṭ as and the Advaitins, non-perception is the source of our knowledge of absence. In other words, the absence of knowledge causes the knowledge of absence. When all conditions of perception are present, but the object is not perceived, the absence of perception produces the perception of absence. In entering a room in the full day light, when there is the absence of the perception of an elephant, we perceive the absence of an elephant in the room. The Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika, however, argues that the absence of an elephant in the room means that the room is characterized by the adjective “absenceness,” which is related to the room by the relation of vi śe ṣa ṇat ā, i.e., adjectivity, a kind of svar ūpa sambandha, in which the nature of abh āva or absence itself is the “term” as well as the “relation.” In other words, “absenceness” is the distinguishing characteristic as well as the relation of characterization. In short, the sense organ, i.e., eyes, perceives the room as well as the “absenceness” of the object in the room. To sum up, negation or absence or non-existence as a category includes both negative entities and various types of negations. Acceptance of abh āva as a separate category recognizes the importance of this category for both metaphysics and epistemology. III Concluding Reflections We have now come to the end of our exposition of the Vaiśeṣika pad ārthas. It is close to the Aristotelian and the Kantian lists, but it is more comprehensive 206 T H E VA I Ś E Ṣ I K A D A R Ś A N A and systematic. It provides the basis for a comprehensive description of the world, but not a list of categories used by modern science. In its conception of the pad ārthas, the Vaiśeṣika provides an enumeration of reals without any attempt to synthesize them. It includes not only such categories as substance, quality, and action, but also such formal categories as identity, difference, and abh āva, and such relational categories as conjunction, inherence, etc. One wonders how the Vaiśeṣika arrived at its list of pad ārthas. Why, for example, causality does not appear in the list? There is no reason to accept the list of Vaiśeṣika pad ārthas as absolute; however, it does provide a good starting point to begin a dialogue regarding the conceptions that underlie this list as well as the reasons for its non-acceptance by those systems which do not accept it. Finally, it is important to note that the Vaiśeṣika pad ārthas are not simply theoretical concepts; they reinforce the close connection between the theory and practice in Indian thought. The very frst s ūtra that lists the pad ārthas includes ātm ā in that list, and emphatically declares that knowledge of these pad ārthas helps to gain mok ṣa. Ātm ā is to be known in its purity as distinguished from other substances. Study Questions 1. Explain the Vaiśeṣika conception of dravya. Of the seven categories, why is dravya the most important? 2. Explain the Vaiśeṣika theory of atoms. What are some of the differences between the Vaiśeṣika and the Greek theories of atoms? 3. Explain the Vaiśeṣika category of karma or action. How does the Vaiśeṣika conception of karma differ from the conception of karma as understood in Indian philosophy? 4. Explain the Vaiśeṣika theory of abh āva. Does it make sense to admit abh āva (negation or non-existence) as an independent category? Give reasons for your answer. 5. Explain the categories of sām ānya, vi śe ṣa, and samavāya. What purpose do they serve in the Vaiśeṣika system? Is it possible to do away with one of these three without jeopardizing the integrity of the Vaiśeṣika pluralistic realism? Suggested Readings For the Vaiśeṣika metaphysics, see Wilhelm Halbfass, On Being and What There Is: Classical Vai śe ṣika and the History of Indian Ontolog y (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992); Pradyot Kumar Mukhopadhyaya, Indian Realism: A Rigorous Descriptive Metaphysics (Calcutta: K.P. Bagchi, 1984). For English translations, see Nyāya-Vai śe ṣika, Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies. Edited by Karl H. Potter (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass 1977), Vol. 2. This work translates some important texts, introduces early philosophers 207 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS of this school, and makes readers familiar with the important concepts and the conceptual distinctions. For an excellent exposition of Vaiśeṣika philosophy, see Praśastapāda’s Pad ārthadharmasa ṅgraha. Translated by Sir Ganganatha Jha (Delhi: Chaukhambha Orientalia, 1982). For a concise introduction to Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika’s central epistemological and ontological principles, see Tarka-Sa ṃgraha of Anna ṃbha ṭṭa with D īpīk ā and Govardhana’s Nyāya-Bodhinī (cited as TSDNB), edited with critical explanatory notes by Yashwant Vasudev Athalye, Bombay Sanskrit and Prakrit Series, No. 55 (Bombay: R. N. Dandekar, l963); The Elements of Indian Logic and Epistemolog y, based on a portion of Tarka-Sa ṃgraha of Anna ṃbha ṭṭa with D īpīka (cited as TS), with translation and explanatory notes by Chandrodaya Bhattacharyya (Calcutta: Modern Book Agency Publishers, 1962). The last two works are based on Tarka-Sa ṃgraha of Anna ṃbha ṭṭa; however, the frst work contains many Sanskrit words in the notes which might pose problems for readers not familiar with Sanskrit. 208 12 THE N YĀYA DAR Ś A NA I Introduction The Nyāya school most likely had its origin in its attempt to formulate canons of argument for use in debates, which pervaded the Indian philosophical scene for a long time. The Nyāya derives its name from “nyāya,” meaning the rules of logical thinking and the means of determining the right thing. Though originally identifed as a system of logic, i.e., laying down the rules of logical argumentation, Nyāya also became renowned as “ānvῑk ṣik ῑ ” (the science of critical examination), blossomed into a systematic school, and found its legitimate place among the six Vedic systems of philosophy. The school is also known as “tarka śāstra” (the treatise of reasoning), “vādavidyā” (the science of debate), “hetuvidyā” (the science of causes), etc. It found a close ally in the Vaiśeṣika school. The Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika systems, despite some minor differences, share a common ontology and epistemology; the Vaiśeṣika developed and detailed ontology (discussed in the last chapter), and the Nyāya advanced epistemology. In this chapter, I will primarily focus on the Nyāya epistemology. Gautama frst systematized Nyāya in the Nyāyas ūtras (NS) in 250–450 CE. This text belongs to the post-Buddhistic period. Nyāya begins with Gautama’s NS and Vātsyāyana’s commentary (Nyāyabh āṣya, ffth century CE) on it; Udyotakara explained and commented on it in his Nyāyavārttika (seventh century CE). Vācaspati (ninth century CE) commented on Nyāyavārttika in his Nyāyavārttikat ῑk ā. Other important works of this school are Udayana’s (tenth century CE) Nyāyavārttikat ātparyapari śuddhi and Kusum āñjalῑ, and Jayanta’s Nyāyamañjar ῑ (tenth century CE). These works elaborate and develop the ideas contained in NS and defend the doctrines against the hostile attacks. Thus, we can say that the ancient Nyāya (prāchῑna Nyāya) developed out of the Gautama’s NS. By the time of Udayana, the foundation of the school of modern Nyāya, technically called “Navya-Nyāya” (Neo-Nyāya), was laid because of the efforts of Ga ṅgeśa, the author of Tattvacint āma ṇi. The most renowned logician of this school was Raghunāth Śiroma ṇ i, and another famous exponent was Gadādhara (seventeenth century). The most important difference between the old Nyāya and the Neo-Nyāya may be expressed as follows: The Neo-Nyāya discussed relational facts as the Nyāya did; however, to express the contents more adequately, the school 209 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS developed a new terminology and style. What the Naiyāyikas expressed in a simple language, the Neo-Naiyāyikas expanded into more sophisticated expressions using such technical jargons as avacchedakat ā (the property of being the limitor), vi ṣayat ā (the property of being the object), prak ārat ā (the property of being a qualifer), and sa ṃsargat ā (the property of being a relation). I will explain it with the help of an example. Whereas the old Nyāya would say “the book is on the table,” the neo Nyāya would express the same as “the book is being qualifed by the qualifer bookness,” state the relation of “being on the table as the relation of conjunction,” and determine the table as qualifed by “tableness.” It is important to note that this was only the beginning of the sophistication. Such authors as Gadādhara excelled in this sophisticated discourse. Thus, beginning with Ga ṅgeśa in the eleventh century in Mithila, Neo-Nyāya had its high period in Navadeep, Bengal, where a galaxy of logicians fourished. In this chapter, however, I will focus on the ancient Nyāya. As stated earlier, the frst systematizer of the ancient Nyāya (henceforth, referred to as Nyāya) was Gautama, also known as “Ak ṣapāda,” who lived in Mithila. He not only systematized the already existing logical thought, but also used the occasion to respond to the Buddhist challenges. Vātsyāyana, Fundamental Postulates 1 Knowledge consists in the manifestation of objects. Knowledge, like the light of a lamp, reveals objects around it. 2 True cognition (pram ā) reveals the object as it is. 3 There are four means (pram āṇas) of true cognition: Perception, inference, comparison, and verbal testimony. 4 Perception is a true cognition produced by sense object contact. 5 Inference is the knowledge that arises after (anu) another knowledge. 6 Comparison or analogy is the knowledge of a relation between a word and the referent of the word. 7 Verbal testimony from an authoritative source is a reliable source of knowledge. 8 There are three untrue (false) cognitions (apram ā): Doubt, error, and hypothetical reasoning. 9 There is a distinction between the nature of truth and the test (criterion) of truth. Truth and how one comes to know it are different issues. 10 Bondage is due to the ignorance of reality. 11 Knowledge of the distinction between the self and the not-self is essential to attain mok ṣa. 210 T H E N YĀYA D A R Ś A N A the author of the principal commentary (bh āṣya) on NS (NSBh), possibly belonged to the fourth century CE. Subsequent commentators did the same; they not only explicated the intentions of the bh āṣya but also defended the Nyāya against opponent’s criticisms. One may say that the Nyāya developed from the time of the Gautama up to the time of Śa ṃ kara (eighth century CE). At the outset in his NS, Gautama names sixteen entities (pad ārthas) by knowing which one can attain the highest good.1 The sixteen entities are (1) pram āṇas or the means of right cognition, (2) prameya or the object of right cognition, (3) sam śaya or doubt, (4) prayojana or purpose, (5) dṛṣṭānta or example (required in inference), (6) siddh ānta or conclusion, (7) avayava or components of an inference, (8) tarka or counterfactual argument, (9) nir ṇaya or ascertainment of the truth, (10) vāda or analytic consideration, (11) jalpa or wrangling, (12) vita ṇḍā or debate, (13) hetvābh āsas or fallacies of the hetu, (14) chala or pseudo replies, (15) jāti or futile arguments, and (16) nigrahasth āna or the place of defeat. The last eight are pseudo-logical arguments. Gautama concludes the s ūtra by noting that a proper knowledge of these entities leads to the highest good. It is not an exaggeration to say that the Nyāya is an elaboration of these sixteen philosophical topics. In this chapter, I will primarily focus on the Nyāya theory of pram āṇas, i.e., the causes of true cognition (pram ā k āra ṇam) and the means of the justifcation of true cognition. As a causal theory, the theory of pram āṇas is subsumed under its ontology, because the theory explains how a certain gu ṇa or property called “knowledge” arises in a certain entity called “self.” As a theory of justifcation, however, the pram āṇas provide not only norms of justifcation for the theory of knowledge, but also justifcation for its ontological theory. Thus, from one perspective, epistemology falls under ontology, but from another, ontology is dependent upon the norms of epistemology. Given that the pram āṇas appear frst on the list of the pad ārthas, I will begin with the Nyāya epistemology. II The Nyāya Theory of Knowledge Pramāṇas (Sources of Valid Knowledge or True Cognition) Vātsyāyana, at the outset of his bh āṣya on the NS, states: The pram āṇas are the most effective means of right cognition. When a thing is known by the pram āṇas, it has the power to arouse fruitful and successful response. In the absence of a pram āṇa, there is neither cognition of a thing nor fruitful response, except when a thing has been cognized. It is only after a knower or the cognizer has apprehended a thing by pram āṇa, he either wants to acquire it or shun it. His practical effort, as qualifed by his desire to acquire or shun the 211 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS thing, is activity (pravṛtti). When a cognizer undertakes the activity after having the desire to acquire or shun it, and by that activity in fact acquires it or shuns it, his activity becomes successful, which constitutes the power of that activity.2 A pram āṇa, in other words, is an unerring concomitant of an object. By the success of a fruitful response is meant the response which leads to success. But a pram āṇa does not directly lead to a successful practice. It leads to success via the true cognition of the object. After the practice is successful, the fact that the pram āṇa has truly grasped the object is ascertained by inference. The point is that no cognition without being true can generate a response which reaches the object. Since a pram āṇa correctly apprehends its object, the knower, the object of knowledge, the knowledge itself, all three become the invariable accompaniments of the object because without a pram āṇa there is no determination of the object. The knower responds because of the desire to possess the object or the hatred to shun it. Pram āṇa is that by which a cognizer knows the object and the object that is known is prameya.3 In other words, pram āṇa is the instrumental cause of a cognition, and prameya is the object cognized. The knowledge of the object is pramiti. Since these four invariably accompany the object, with these four the nature of truth (tattva) is exhausted. But what is this tattva? It is the being of what it is, and the non-being of what it is not. Vātsyāyana proceeds to argue that when the being of an existent thing is cognized, at the same time, the non-being of what it is not is also apprehended. Like a lamp, a cognition manifests what is there, but at the same time, it also manifests what is not there. The intention is to assert that the absence is cognized in much the same way as the presence of a real entity. As a result, though Gautama does not mention it, absence is as much a pad ārtha as a positive entity, whatever is determined by a pram āṇa is a pad ārtha. The above paragraphs briefy, though pointedly, articulate the nature of the cognitive process, its relation to being and non-being of things, the relation of knowledge to the object, the means of knowing, the object known, and the practical response which follows one’s cognition. The means of knowing or pram āṇas are four: Perception, inference, comparison, and verbal knowledge or testimony.4 I will begin with perception. Perception (Pratyak ṣa) The word “perception” applies to both a form of true cognition (pram ā) and the method or the pram āṇa of acquiring true cognition. Here, we are concerned with the perception as a pram āṇa. For the Naiyāyikas, perception is a cognition that is produced ( janya) from the contact of a sense organ with an object; it is not itself linguistic, is not erroneous, and is well ascertained.5 The self, the mind, the sense organs, the objects, and specifc contacts between them are necessary for the perception 212 T H E N YĀYA D A R Ś A N A to occur. The contacts take place in a succession: The self comes in contact with the mind or the manas, the manas with the sense organ concerned, and the sense organ with the object. This operation produces a cognition of the sort “this pitcher is blue.” All knowledge is revelation of objects, and the contact of the senses with an object is not metaphorical, but literal. For the Naiyāyikas, sense contact with the object is the primary and indispensable condition of all knowledge. They further maintain that the senses can be in contact not only with their objects, qualities, and universals, but also with their negation. All perceptual knowledge can be expressed in the form of a judgment, a subject with something predicated of it. A percept, such as a cow, really stands for a judgment. “A cow,” for example, “means an object possessing the characteristic of cowness.” In cases of perceptual illusions, the sense comes in contact with the real object; however, because of the presence of certain external factors, it is associated with the wrong characteristics, and the object is misapprehended. In other words, what is present in the mind appears as the object in front of us. The Nyāya defnition of perception as a form of valid knowledge that originates and is caused by sense stimulation follows the etymological meaning of the term “pratyak ṣa.” Etymologically, “pratyak ṣa” is a combination of “prati” (to, near, before) and “ak ṣa” (sense organ), meaning “present before the eyes or any other sense organs”; it signifes direct or immediate knowledge. Gautama considers the term “object” to signify both physical objects (e.g., table, chair, pitcher) and internal objects (e.g., pleasure and pain).6 So, perception is a cognition that is always of an object. Cognitions of substances like tables and chairs are “external perceptions,” and of pleasure and pain are “internal perceptions.” Gautama further adds that perception is not impregnated by words (avyapade śa) and defnite (vyavasāyātmaka). When we try to come to grips with the Nyāya defnition of perception, we begin to see that the defnition applies only to perceptions which are “ janya,” i.e., “produced”; these perceptions arise and pass away. This defnition of perception does not include divine or yogic perceptions which do not require contact of the sense organs and the objects. The Naiyāyikas were aware of this diffculty; so, the later Naiyāyikas attempt to make the concept of “contact” more precise by making a distinction among different kinds of contacts, and articulate the defnition of perception in terms of direct and immediate cognition which does not require sense-object contact. Ga ṅgeśa, for example, defnes perception in a more general sense to include both human and divine perceptions. It is a cognition that is not caused by another cognition.7 This defnition applies to God’s perception which is not caused, as well as to human perceptions, which are not caused by any prior knowledge but by sense object contact. To understand the Nyāya theory of perception, it is essential that we have a clear conception of what the Naiyāyikas mean by “contact.” On the Naiyāyika account, contact is a function of a sense organ through which it enters into a specifc relation with its appropriate object giving rise to the perception of 213 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS that object. This contact between the sense organs and the objects may be of various kinds. The Naiyāyikas, following the commentator Uddyotakara, distinguish among six kinds of contacts8 between a sense organ and an object. Six Ordinary Contacts 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sa ṁyoga (conjunction): A direct contact of the eyes with the object, say, a pitcher in the kitchen in full sight. Sa ṁyukta samav āya (inherence in what is conjoined): An indirect contact of sense organ with its object through the mediation of a third term that is related to both, e.g., when my eyes come in contact with the color of the pitcher through the pitcher in full sight. Sa ṁyukta samaveta samavāya (inherence in what is inseparably related to what is conjoined): A still more indirect contact with the mediation of two terms that are related, e.g., in perceiving a pitcher in the kitchen, I also perceive “colorness” which inheres in the color of the pitcher; there is a contact of the eyes with the “colorness” with the mediation of “pitcher” and “color,” i.e., conjunction with the pitcher and the second kind of contact with the color. Samav āya (inherence): When I hear a sound, the sound inheres in the ear (according to Vai śeṣika ontology), so the sense organ of hearing is in contact with the sound in the relation of samav āya. Samaveta samavāya (the relation of inherence in that which inheres): The contact between the sense and its object via a third term that is inseparably related to both, e.g., in the auditory perception of soundness, the ear is in contact with the “soundness” because it inheres in the sound, which, in turn, inheres as a quality in the ear. Vi śe ṣaṇa vi śe ṣaya bh āva (qualifer-qualifed relation): Here the sense is in contact with the object insofar as the object is a qualifcation of the other term connected with the sense—for example, when I see the absence of a pitcher on the foor. The Naiyāyikas explain the perception of non-existence and the relation of inherence with the help of this contact. When I see the absence of an elephant on the foor of my room, the visual sense organ has a conjunction with the foor, but the absence is in the relation of viśeṣaṇatā with the foor. The Naiyāyikas, in addition to the six ordinary contacts, recognize three extraordinary or alaukika contacts. Cases of perception that cannot be explained in terms of ordinary contact between the object and any of the sense organs are termed extra-empirical perceptions (alaukika pratyṣakas). They are sām ānyalak ṣan ā pratyak ṣa (perception of universals), jñ ānalak ṣa ṇā pratyāsatti (perception by complex association or complication), and yogaja (intuitive perception). 214 T H E N YĀYA D A R Ś A N A The Naiyāyikas argue that when we perceive an object, we perceive not only the object presented to the sense but also the universal that inheres in it. For example, when I perceive a cow, I not only perceive the cow but also perceive the “universal cowness” that inheres in it. In this instance the contact between the sense organ and the cowness is not direct. The cowness is cognized mediately, through the perception of at least one cow, by recollection; this is perception of universals by extra-empirical contact. The second kind of extraordinary contact takes place when upon perceiving a piece of velvet, I also see its softness though I am not touching it. The color of the velvet and its softness are associated in such a way that when I see one of them in an ordinary contact, I also see the other in an extraordinary manner. Here the knowledge of the one, i.e., the texture of the piece of the cloth, serves as the medium through which the softness is visually perceived. It is that in which one percept gives rise to another, as when one perceives a piece of sandal-wood at a distance, one at once knows that it is fragrant. Here the fragrance could be perceived neither by the eye, nor by the nose as the sandal piece was at a distance; it is therefore apprehended by a kind of extraordinary perception.9 This process corresponds to what has been articulated as perception through complex association in Western psychology. Yogaja or intuitive perception refers to the concentration of mind through which a yog ī sees things that are beyond the scope of ordinary sense perception. Persons may develop abilities with the yogic practices to perceive events yet to occur, or things at a great distance, or things like atoms, which are too minute to be ordinarily perceived. This kind of extraordinary contact is possible only for persons adept in yoga. The Naiyāyikas argue that a perceptual cognition takes place in two stages. At frst with the contact of the sense organ with the object, there arises what is known as indeterminate or non-conceptual (nirvikalpaka) cognition, and the cognition that arises after it is determinate or conceptual (savikalpaka) cognition.10 Most systems of Indian philosophy recognize this succession: First, the nirvikalpaka or the non-conceptual perception, and then the savikalpaka or the conceptual perception. However, the systems differed as to the precise nature of the non-conceptual perception. On the Nyāya view, all the components of a conceptual perception are known in the non-conceptual, but only without being related to each other. In effect, a non-conceptual perception is cognition of a bunch of unrelated entities (e.g., “this” and “thisness,” “ jar” and “ jarness,” “blue” and “blueness”), but these entities are related into one complex structure in a conceptual perception. The non-conceptual is a perceptual cognition, but there is no cognition of this cognition; consequently, I do not know immediately that I had a non-conceptual perception. Only its having occurred is known by inference after the occurrence of the conceptual perception. In other words, the perceptual cognition “this pitcher is blue” 215 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS would not have occurred unless I had previously apprehended such elements as “this,” “thisness,” “pitcher,” “pitcherness,” “blue,” and “blueness” separately. Thus, non-conceptual is the prior knowledge of a thing and its constituents as unrelated entities; it is known through inference from the conceptual perception. Inference (Anum āna) Inference or anum āna is the primary concern of Nyāya, which is subsumed under logic in the Western sense. It is important to remember that in the Indian discourse the domain of logic is part of the theory of knowledge or the pram āṇa theory. The Indian theories discuss inference as a pram āṇa, i.e., as a mode of knowing and not merely as a theory of valid thinking. Gautama notes that inference as a means of knowing is grounded in perception.11 It is the knowledge that arises after (anu) another knowledge. Vātsyāyana focuses on the etymology of anum āna (anu = after and mana = measuring) and states that anumāna is measurement after something;12 it is that cognition which presupposes some other cognition. It is mediate and indirect and arises through the knowledge of the mark or liṅga. Consider the case of seeing smoke on a distant hill. Upon seeing the smoke on a hill, one infers that there is fre on the hill. In this case, the smoke serves as the mark of the fre. Anna ṃbhaṭṭa notes that anumāna or inference is the instrument of the inferential cognition (anumiti).13 Two aspects of the Nyāya theory of inference are worth noting: The inference for oneself (svārth ānuma āna) and the inference for others (parārth ānum āna).14 The frst provides a psychological account of the process. Let me provide an illustrative example. Earlier in his life, a person, say, Bina, had acquired the knowledge “wherever there is smoke, there is fre.” Now upon seeing a column of smoke on a hill, Bina remembers what she had learnt previously, viz., that fre always accompanies the smoke, and concludes that the hill is fery. This last perception (whose cognitive structure is more complex than the initial perception of smoke) would produce, in any rational mind, the inferential cognition “there is fre on the hill.” So far, the account given is entirely psychological, i.e., a description of the mental process which culminates in an inferential cognition. Clearly, the process is not a logical structure; it gives the story of a causal chain of how a cognition causes another whose fnal member is the inferential cognition. However, in the second aspect of the theory, for the purposes of convincing the other (parārth ānum āna), one can transform the story into a logical structure, somewhat like a syllogism with the well-known fve-membered structure,15 which is represented as follows: 1 there is fre on the hill (the proposition to be proved or pratijñ ā), 2 because there is smoke (states the reason or hetu), 216 T H E N YĀYA D A R Ś A N A 3 wherever there is smoke, there is fre (vyāpti), 4 as in the case of the kitchen (example or drṣṭānta), 5 there is fre on the hill (conclusion or nigamana). The frst step is the assertion to be proved; the second gives the reason; the third illustrates the invariable concomitance (e.g., of smoke and fre); the fourth expresses “this too is like that,” which in this context means that “this hill too is like a kitchen because it possesses smoke which is invariably concomitant with fre”; and the ffth is the conclusion in which the initial assertion is established as proved. Of the above Nyāya construction of the fve-membered inference, two important features must be remembered. First, the frst premise states the conclusion, not as proved, but the assertion to be proved. Second, the fourth premise provides an example, which illustrates the vyāpti or the universal concomitance between the middle term or hetu (smoke) and the major term (fre) to be proved or sādhya. The example rules out the possibility of using such universal propositions as “all men are immortal,” which are formally valid but materially unsound. It is required that both the parties to the dispute agree about the example to be used. In short, the inference requires both; it must be formally valid and materially true. Those familiar with Western logic will easily recognize that the Nyāya sādhya, pak ṣa, and hetu resemble the major term, the minor term, and the middle term respectively of the Aristotelian syllogism. In the example under consideration (“this hill has fre, because there is smoke on the hill”), one could say that the “hill” is the minor term, “fre” the major term, and “smoke,” the middle, borrowing the technical vocabulary of the Aristotelian syllogism. It might be argued that the frst and the ffth premise of the Nyāya inference is the same; thus, the frst of them can be dispensed with, and the fourth premise is a mere repetition or application of the hetu, and so it is superfuous; so, there would remain only three propositions. So, it is not surprising that many modern scholars tend to reduce the fve-membered Nyāya anum āna to a three-membered syllogism. Such a reduction, however, is misleading. It is also misleading to suggest that there is one-to-one correspondence between the Nyāya sādhya, pak ṣa, and hetu and Aristotle’s major, minor, and middle term respectively. Let me elaborate. It is important to remember in this context that whereas Indian logic deals with entities, the Aristotelian logic deals with terms. In the Aristotelian logic, the validity of a syllogism depends on the extension of the minor term. Let me give an illustrative example. All human beings are mortal. Socrates is a human being. Therefore, Socrates is mortal. 217 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS We can see from the above example that in the Aristotelian logic one fnds three propositions, and the extension of the minor term “Socrates” is subsumed by the middle term “human being” and the extension of the middle term by that of the major term “mortal.” In the Nyāya anum āna one fnds fve steps. A jñ āna (cognition or knowledge) for Nyāya is an event, an occurrence, and the fve steps of the inference are descriptions of jñ ānas which one undergoes in the process of inference. If the frst four cognitions of the inferential process occur, the ffth one will follow. The Aristotelian syllogism concerns the formal principles of the validity of an argument, the Nyāya inference seeks both the formal validity and the material truth. An example, acceptable to both the proponent and the opponent in the fourth premise, assures the material truth within the logical structure of an inference. In addition, Western logic, especially in the modern form, completely separates logic from psychology, which does not exist in Indian logic. Thus, there are important differences between the Aristotelian syllogism and the Nyāya inference. If we keep these differences in mind, we can still call the Nyāya terms by their Aristotelian counterparts for easy reference. Finally, the Nyāya’s conception of inference clearly demonstrates the close connection between the psychological process of inferring and the logical structure of inference. In Western logical theories, particularly during the last century, psychologism in logic has been severely criticized by such thinkers as Frege and Husserl. The conception of pure logic as an ideal structure of rationality above the temporal process of one’s mental life does not appear among the concerns of the Indian mind. The psychological process is also logical; however, it must be cast into a form that is suited for intersubjective communication. Scholars raise various questions regarding the nature of inference and the methods of establishing vyāpti. In this introductory exposition, it is not possible to discuss them all. However, to give my readers a favor of the kinds of questions raised and discussed, I will briefy review two classifcations of inference: The frst deals with the nature of inference, and the second deals with the method of establishing vyāpti. Gautama makes a distinction among three kinds of inference—p ūrvavat, that which infers from a cause (li ṇga) to the effect; śe ṣavat, that which infers from an effect to the cause; and sām ānyatodṛṣṭa, that which brings together several singular judgments under a universal.16 The frst two are based on causation and the last one is based on simple coexistence. In the frst case, viz., p ūrvavat, i.e., “like what has been before,” one infers based on past experience (hence this name): One sees dark clouds and infers rain that is to follow. In the second case, viz., śe ṣavat, i.e., “like what follows,” one infers the cause from the effect: One tastes a little water in the sea as salty and infers that the entire sea water is so. In the third, viz., sām ānyatodṛṣṭa, we infer the one from the other not on account of any causal relation but because they are uniformly related in our 218 T H E N YĀYA D A R Ś A N A experience. One observes a person, Caitra by name, now to be at a place, and sometime later sees the same person at a different place and infers that Caitra must have moved from one place to another. Seeing the sun in the eastern horizon in the morning and the sun in the western horizon in the evening, one infers the movement of the sun from the east to the west. On seeing some mango trees bloom, one infers all mango trees to be blooming. The third inference is the same as an inductive generalization or bringing individuals perceived under a general concept that also applies to unperceived individuals. Another way of classifying inference is based on the nature and different methods of establishing vyāpti. These are keval ānvayi, kevalavyatireki, and anvayavyatireki.17 In the frst, the middle term is positively related to the major term, and the vyāpti is arrived at through the method of agreement in presence; there is no instance of their agreement in absence. For example: All knowable objects are nameable. The pitcher is knowable. Therefore, the pitcher is nameable. This inference corresponds to Mill’s Method of Agreement. In this inference the universal premise “all knowable objects are nameable” is arrived at by an enumeration of the positive instances of agreement between “knowable” and “nameable.” In the second, the middle term is negatively related to the major term, and the vyāpti is arrived at through the method of agreement in absence, there being no instance of their agreement in presence. For example: What is not-different from other elements has no smell. The earth has smell. Therefore, the earth is different from other elements. Here smell is the differentia of “earth.” In this inference, the smell is coextensive with earth, and there is no instance of the middle term “smell” with any term except the minor term, i.e., earth. In the third, the middle term is both positively and negatively related to the major term. For example: All smoky things have fre. This hill has smoke. Therefore, this hill has fre. And 219 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS No non-fery thing has smoke. This hill has smoke. Therefore, this hill is not non-fery, i.e., this hill has fre. In this inference, vyāpti is based on a universal relation between the presence and the absence of the middle and the major terms. Comparison or Analogy (Upam āna) Let us now turn to the third pram āṇa, i.e., upam āna. Etymologically, the word “upam āna” is derived from “upa” meaning “similarity” and “m āna” meaning “cognition”; so, upam āna is “knowledge by similarity.”18 Upam āna gives us knowledge of something based on similarity with an object which was already known. So, upam āna is the instrument of resulting knowledge (upamiti).19 As a pram āṇa, it is the means of proving or making known what is to be known based on similarity with an object that is already well known. Consider an example in which a person has never seen a gavaya and does not know what it looks like, but he has heard from his friend that a gavaya looks like a cow. Later, he sees an animal much like but not quite a cow. He then remembers what his friend told him: Namely, that a gavaya looks like a cow. The person then realizes that the name gavaya is associated with this particular object. Thus, in upam āna, based on similarity with an object which is already known, e.g., “as the cow, so the gavaya,” we have the knowledge that the animal known as “gavaya” is just like the cow. Such analogies are of immense value and provide useful practical knowledge.20 Of the nine systems of Indian philosophy, M ī māṁ sakas and Advaita Ved ā nta schools recognize upam āna as a separate pram āṇa, but the C ā rv ā kas, Jainas, S āṁ khya, and Vai śeṣika include it in one of the three pram āṇas, viz., perception, inference, and testimony. For example, the Jainas reduce it to recognition, the Buddhists to perception and testimony, and the S āṁ khya and the Vai śeṣika schools to inference. The Naiy āyikas argue that we cannot obtain the knowledge gained by upam āna from either perception or inference. The process of the knowledge by similarity consists of the following steps: 1 2 3 I have not seen the animal known as gavaya before; I have heard that there is such an animal and that animal looks like a cow; and I have already seen a cow and known what a cow looks like. When these conditions are met, and when I see an animal that I have never seen before, I notice the similarity of this animal with a cow; I then recollect that a gavaya resembles a cow and arrive at the judgment “this is a gavaya.” Knowledge by comparison always assumes the form “as…so,” which is used to express similarity, e.g., “as the cow, so the gavaya.”21 Inference never 220 T H E N YĀYA D A R Ś A N A assumes a similar form, e.g., “as the smoke, so the fre”;22 so, it is not inferential knowledge. Therefore, upam āna must be accorded the status of an independent pram āṇa. Verbal Testimony (Śabda) Śabda is “verbal knowledge,” derived from words and sentences. Śabda as a pram āṇa, i.e., as a source of valid cognition, refers to the authoritative verbal testimony (āptavākya), the sentences uttered by a trustworthy person (āpta). Such a person knows the truth,23 speaks the truth, and truth completely accords with the object as it exists in reality ( yath ārtha).24 So, a person is āpta, when the words uttered by him truly represent the nature of the object ( yath ārtha śābdabodhah), and a verbal testimony (śābdabodhah) is truth ( yath ārtha) when it represents the thing as it is. It is not enough that the testimony is reliable, but it is important that one clearly understand the meaning of the sentence uttered by an āpta person. A sentence is a collection of words which has the power to convey its meaning. To acquire knowledge from a reliable testimony, one must understand the meanings of the words. A word or pada is a collection of syllables or var ṇas. Here a collection signifes “being the object of a cognition.”25 Such a sentence, when uttered by a person who knows, is a pram āṇa (means of true cognition). Therefore, śabda as a source of valid cognition consists in understanding the meaning of words uttered by an āpta (trustworthy) person. Thus, we have (1) written or spoken testimony of a trustworthy person, (2) understanding of the meaning of the words uttered by such a person, and (3) verbal knowledge of the objects under consideration. To be intelligible, a sentence must meet certain conditions.26 These are “āk āṅk ṣā” or expectation or mutual implication, “yog yat ā” or ftness or suitability, “sannidhi” or nearness or proximity, and “t ātparya” or intention.27 A mere random group of words does not make a sentence, because they are not related by “āk ānk ṣā” or expectation. The words “cow, horse, man” do not form a sentence, because the words do not arouse expectations. The words must be related in such a manner that they need each other to make sense. Thus, “the knowledge of the connected meaning (of a sentence in which it occurs) is what constitutes (its) expectancy.”28 The second condition outlines the ftness of the words to convey the meaning and not contradict each other; it “is the absence of incompatibility of sense.”29 If someone says, “sprinkle the grass with fre,” we do not have a sentence, for the word “sprinkle” arouses an expectation which “fre” is not appropriate or ft to fulfll. “Proximity is the utterance of words without (inordinate) delay.”30 Again, even if the words are appropriate, they must be uttered in quick succession. Uttering words at long intervals do not constitute a sentence. Thus, the words “bring --------a----------glass--------of---------water” do not make a sentence. The point that is being made is as follows: The utterances must be close 221 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS enough to constitute a sentence. The words—when they arouse expectations, are appropriate, and are uttered in quick succession—constitute a sentence. For example, “I am going to King of Prussia Mall to shop for a dress.” Finally, the Naiyāyikas maintain that the intention of the speaker is “t ātparya.”31 To know the desire of the speaker is crucial to an understanding of the import of a sentence; the intention of the speaker is especially relevant, where various literal meanings are possible (as in “bring saindhava,” the word “saindhava” means both “horse” and “salt”). It is important to know what the speaker intends. If a man is eating dinner, he wants salt, not a horse. The Naiyāyikas interpretation of t ātparya is different from the Advaitin interpretation. The Advaitins defne t ātparya “as the competency to generate a cognition.”32 The sentence “there is a pitcher in the house” has the capacity to produce a cognition of the relation between the pitcher and the house, and not a cognition of the relation between the house and a piece of cloth. Hence, “that” in the defnition signifes the relation between the pitcher and the house and not between, say, the cloth and the house. Śabda as a pram āṇa, argue the Naiyāyikas, is of two kinds: Human or ordinary (laukika) and divine or extraordinary (alaukika).33 Laukika testimony is the word of a reliable human person and the alaukika is divine testimony, the words of the Vedas, i.e., God’s utterances. Human testimony is fallible, but the divine testimony is infallible. In sum, śabda or word is an important pram āṇa. It is the means we use to come to know about things, simply by hearing sentences uttered by a competent speaker. We learn about physics, about history, by listening to the lectures of competent physicists or historians respectively. We learn about contemporary events by reading reliable reports. This kind of knowing occupies a central place in Indian epistemologies—partly because it is by this means that we learn about what we ought to do, or how we ought to lead our lives, about dharma and adharma, from the Vedic discourses, to name a few. This kind of knowing is at times criticized as being dogmatic acceptance of the authority, but this hasty criticism fails to recognize its ubiquitous indispensability for our knowledge of the world. Just imagine what a small fragment of the world we would be restricted to, if we relied exclusively upon perception and inference. In refecting on the relative strength and weaknesses of the different pram āṇas, we see that the Naiyāyikas regard perception to be stronger than inference. Vātsyāyana in his bh āṣya34 recognizes that all the pram āṇas ultimately rest on perception: Inference is that knowledge which is preceded by perception (tatp ūrvaka ṁ);35 upam āna is based on the perception of similarities between two objects; and śabda depends on perception insofar as it involves visual or auditory perception of written or spoken words. With regard to the supersensible entities, inference is stronger than perception, and śabda is stronger than inference, śabda is the strongest in cases of what ought to be done. It is worth noting that the Naiyāyikas believe that the same object can be known by perception, inference, and śabda (pram āṇasa ṁplava). The Buddhists, in contrast, believe that to the specifc types of objects, there correspond specifc 222 T H E N YĀYA D A R Ś A N A pram āṇas (pram āṇavyavasth ā). In general, the Vedic philosophers believed in pram āṇasa ṁplava, i.e., the thesis that the same object is knowable by different pram āṇas, e.g., by perception, inference, and by śabda. The Nature of Knowledge We have examined the four pram āṇas that the Nyāya recognizes. Now we will turn our attention to the general nature of “knowledge.” Knowledge is known as “anubh ūti” or “ jñ āna.” According to Nyāya, “consciousness” and “knowledge” are synonyms36; not so, however, in other Indian systems of philosophy. Nyāya also differs from the spiritual (ādhyātmika) philosophies in regarding consciousness as a quality (gu ṇa) produced in a self (ātman) only when the self is embodied and there is appropriate contact of the sense organs with the object. Without a functioning body, there is no consciousness; there is no consciousness in the state of deep dreamless sleep. However, despite the dependence on the bodily functions, consciousness does not exhibit characteristics that are uniquely its own. Like a beam of light, it “shows up” or manifests whatever it falls on. It is also intrinsically of-an-object, there being no objectless consciousness. Knowledge is not an action, to know is not to act. Given that it arises in the self when certain conditions are fulflled, knowledge is not an essential quality of the self. However, only an embodied self can know. Contrary to the position of the spiritual philosophies—the Sāṃ khya-Yoga, the Buddhists, and the Vedānta—the Nyāya does not regard consciousness as self-manifesting. It only manifests its object. Since it is not its own object, it cannot manifest itself. It is manifested, known, made aware of, only by another subsequent, knowledge. Thus, we have a knowledge K1 whose object is O1. K1 manifests O1. After K1 has occurred, there may follow an introspective knowledge of K1. Let us call it K 2; K1 is then manifested to the self. K1 has the form “this is a jar.” K 2 would have the form “I know that this is a jar.”37 Knowledge or cognition is of two kinds: Those that are “valid” ( pram ā) and those that are not (apram ā). Valid knowledge or cognition (pram ā) is of four kinds, depending upon the causal process by which a knowledge arises, which we have already discussed. Invalid knowledge or cognition is of three kinds: Error, doubt, and hypothetical argument.38 Invalid knowledge Error Perceiving a rope as a snake and a shell as silver are instances of errors. To explain the erroneous cognition of silver, the Naiyāyikas postulate a relation 223 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS of identity between the object before us and the remote silver. They argue that the relation of inherence that exists between the “silver” and the “silverness” is also apprehended in the “this” and the “silverness.” The silver perceived in a jewelry store sometime in the past is perceived through jñ ānalak ṣa ṇasannikarṣa (perception by complex association or complication), one of the extra-empirical contacts recognized by the Naiyāyikas. Thus, the shell is mistaken for silver. Falsity consists in associating silver with the shell where it does not exist. Neither of them is unreal. The goal of the Nyāya theory is to demonstrate that error, like truth, has an objective referent. It is neither the Mādhyamika asatkhyāti, i.e., the perception of nonexistence,39 nor the M īm āṃsā akhyāti, i.e., wrong perception.40 All knowledge claims, irrespective of whether true or false, are referential. It is only the false prediction of “that” as “what” (i.e., silver) which is subsequently corrected, but never the “that” itself. Doubt Doubt, being uncertain knowledge, cannot be pram ā. Gautama in NS defnes doubt as follows: “Doubt is a wavering judgment about the nature of an object which is due to the cognition of common qualities present in many objects, or of qualities not present in any of the objects, from conficting views, and lack of uniformity in apprehension and non-apprehension.”41 In other words, doubt is that wavering judgment in which the certainty about the specifc character of any object is lacking, and the mind vacillates between mutually contradictory descriptions of the same thing, each of which is possible.42 A thing is known in general terms, but there is no apprehension of its specifc nature. The Nyāya literature discusses the ways and conditions under which doubts occur; there are different alternatives available but no discernment of any specifc mark or characteristic to decide among the conficting alternatives resulting in a doubt assuming the form, “is this a man or a tree (“sth āṇuraya ṃpuru ṣo vā”)?” Doubt precedes the exercise of nyāya, that is, of the different means of knowing to ascertain the nature of a thing and remove doubt. It is arguable that doubt and the effort to remove the doubt are rational activities, though Mohanty argues that the Nyāya sa ṃśaya is a perceptual doubt, whereas the Cartesian doubt is an intellectual doubt.43 However, here one must not lose sight of the fact that the resolution of doubt involves seeing things more clearly and differentiating them from other objects; the resolution of doubt is a rational activity. Tarka (Hypothetical Argument) Tarka in NS is a kind of indirect proof to ascertain the true nature of a thing.44 It is a kind of hypothetical argument, which is an indirect way of justifying a conclusion. It demonstrates that the presumed hypothesis to prove the conclusion leads to absurdity.45 Tarka, an intellectual cognition, produced by desire assumes the following form: “If smoke could exist in a locus which does not 224 T H E N YĀYA D A R Ś A N A have fire, then smoke could not be caused by fire.” The question is: Whether any absurdity would result if one accepts the given conclusion or rejects it as false. This kind of argument removes any doubt in the vyāpti, e.g., “wherever there is smoke, there is fire,” and, as a result, strengthens the inference that proves the presence of fire upon perceiving smoke. Let me again use the standard example employed in most Sanskrit texts to explain tarka: In looking through the bay window of my house, I see smoke coming out of the house across the street and say that the house across the street is on fre. A friend sitting next to me argues that there is no fre; there is only smoke; in response, I advance a tarka: “if there could be smoke without there being fre, then one could produce smoke without fre, which is absurd.”46 It is important to remember in this context that tarka does not give rise to true knowledge, i.e., it is not a pram āṇa, because one of its premises, the assumption of the contradictory of the conclusion, is false. It confrms a pram āṇa; it is an aid to pram āṇa. This process of indirect proof in the Nyāya roughly corresponds to reductio ad absurdum of Western logic. A knowledge is valid or pram ā when it arises by an appropriate pram āṇa and agrees with its object. A pram āṇa is thus both the proper cause of a valid cognition and its justifcation. This unique combination of a causal theory and a justifcation theory of knowledge is almost unique in the history of philosophy. Nyāya Theory of Truth To discuss the theory of truth in Nyāya, I will begin, following Kant, by distinguishing between the nominal meaning of the “truth” and the real, universally valid criterion of truth. The Naiyāyikas, unlike Advaitins, accept the nominal meaning of truth, i.e., if a thing is such and such, to know it as being such and such is true. If a thing has the property of p, to know that it is p is true and to know that it is not-p would be false.47 However, as soon as we ask how to determine the truth of a cognition, philosophers give different answers. According to some, the criterion of truth is the ability to give rise to successful practice.48 The Naiyāyikas argue that whereas a true cognition corresponds to its object and leads to successful activity, a false cognition does not correspond to its object and leads to failure and disappointment. Suppose you are baking a bread and need salt; you see a white powdered substance before you, and prior to putting it in the batter, you take a pinch of it, put it in your mouth, and upon tasting, realize that it is salt. On another occasion, while looking for salt when you are baking a cake, you fnd out that the white substance you see before you is not salt, but sugar. The Naiyāyikas argue that whereas the truth and the falsity of a cognition depends on the correspondence and non-correspondence to facts respectively, the test of its truth and falsity consists in inference from success and failure of our daily activities in relation to the object sought. 225 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS A true cognition gives rise to a successful activity, a false cognition to failure and disappointment. Regarding the question whether truth (also falsity) of a cognition is svataḥ or intrinsic to the cognition or extrinsic, i.e., parataḥ, the Naiyāyikas hold that both the truth and the falsity are extrinsic or parata ḥ. In other words, when a knowledge arises from the causal conditions which produce it, it is not eo ipso true, nor it is from the very beginning known to be true (or false as the case may be). Truth needs a special causal condition for it to arise, i.e., some special excellence in the generating conditions, just as falsity is produced by some special defect in them. In other words, when the Naiyāyikas state that the truth and the falsity are extrinsic, they mean that the cognitions are not self-manifesting and that the properties that produce the cognitions are different from the factors that are responsible for producing the truth and the falsity of the cognitions. When a cognition comes into being, it simply manifests its object, but not itself (as stated earlier), so it does not know its own truth or falsity. It is only subsequently that the knower infers based on the success (or failure) of the action whether his knowledge was true (or false). Thus, according to the Nyāya, practical success (or failure) is the criterion of truth (or falsity). A cognition is true when it corresponds to the nature of its object; it is false, when it does not. The Advaitins, however, maintain that both truth and falsity are intrinsic.49 III Nyāya Pad ārthas (Categories) As stated earlier, Gautama mentions sixteen pad ārthas.50 They are (1) pram āṇas (means of true cognition), (2) prameya (object of cognition), (3) sa ṃśaya (doubt), (4) prayojana (the objective or purpose), (5) dṛṣṭānta (familiar example), (6) siddh ānta (conclusive view), (7) avayava (member), (8) nir ṇaya (ascertainment), (9) vāda (discussion, controversy), (10) jalpa (rejoinder or wrangling), (11) vita ṇḍā (cavil, quibbling, mere criticism without having own position), (12) tarka (hypothetical argument), (13) hetvābh āsa (fallacy of the hetu or the middle term), (14) chala (misleading interpretation, a kind of equivocation), (15) jāti (legitimate objection, futile argument), and (16) nigrahasth āna (defciency, the ground of defeat).51 Gautama accords the sixteen categories equal status; at a minimum the categories provide a conceptual framework within which the Naiyāyikas philosophical discourse took place. Of the sixteen categories, I have already discussed pram āṇas (means of true cognition, #1), doubt, (#3), and tarka (#12) in the previous section. I will, in this section, review the remaining thirteen pad ārthas, and begin with #2. 2 At the outset of his NS, Gautama informs his readers that pram āṇa is the instrument and prameyas are the objects of right cognition.52 Both pram āṇa and prameya are k āraka words, i.e., the words that express noun functions and conform to the nature of nouns. Their function is contingent upon the circumstances. For example, in the Gautama’s list self is numbered as 226 T H E N YĀYA D A R Ś A N A one of the prameyas because it is not only an object of cognition, but also a cognizer.53 Gautama in his NS lists twelve prameyas.54 These are (1) the self (ātm ā), (2) the body, (3) the senses, (4) the objects of the senses, (5) cognition (buddhi) or apprehension, (6) mind (manas) or the inner sense, (7) activity (pravṛtti), (8) defects, (9) rebirth after death (pretyabh āva) which is the result of our good or bad actions, (10) fruition, (11) pain, and (12) release. The omniscient self is the seer, the enjoyer and the experiencer of all things. The body is the place of its enjoyment and suffering, and the sense organs are the instruments for enjoyment and suffering. Enjoyment and suffering are cognitions (of pleasure and pain). The inner sense or manas is that by which can know all objects. Cognition (buddhi), knowledge ( jñ āna) and apprehension (upalabdhi) are synonymous. Action ( prav ṛtti) causes pleasure and pain; so, do the do ṣas (defects), namely, passion, envy, and attachment. The self had previous bodies than this one, and will occupy other bodies after this one, until the achievement of “mok ṣa.” This beginningless succession of birth and death is rebirth. Experiences of pleasure and pain, along with their instruments, i.e., the body, the sense organs, etc., are the ‘fruit’ ( phala). “Pain” is inseparably connected with “pleasure.” To achieve mok ṣa or apavarga, one should realize that all happiness is pain—which will result in detachment, and, eventually freedom. 55 4 Prayojana56 or purpose or an end-in-view is the object for which we act: Either to desire it or to shun it. In other words, there is some goal, which we think we should reach or shun, and this determination or purpose leads to an application of nyāya. The primary purpose is the attainment of happiness and the removal of dukkha; however, everything that leads to the realization of the primary purpose can also function as a secondary or subsidiary purpose. 5 D ṛṣṭānta or familiar example represents an undisputed fact that illustrates a general rule.57 It is that entity regarding which there is an agreement between both parties, i.e., between ordinary persons and critical thinkers. In other words, the ordinary persons and the critical thinkers using logic must agree regarding something, and only such an agreed entity that can be used as an example. In other words, when one argues that the hill must be fery because it is smoky, the kitchen may be an example of that in which one sees smoke accompanied by fre. Example thus is a very important and necessary part of the Nyāya reasoning; it is a component of the Nyāya fve-membered syllogism discussed earlier. 6 Siddh ānta or the conclusive view is the doctrine which belongs to a śāstra or a discipline or a science.58 Conclusion is the defnite ascertainment of an entity. It is accepted as true in a tradition or school. Gautama divides it into four kinds59: 227 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS 7 8 9 10 11 • sarvatantra siddh ānta (all-accepted conclusive view), not disputed by any school, is that which is accepted by all parties, including one’s own school; • pratitantra siddh ānta (conclusive view of one of the schools) is that which is established only by one of the schools and its allies; • adhikara ṇa siddh ānta (ground conclusive view) is the support or the ground doctrine on which we establish the property of a given thing; however, frst, we must establish another property of it. For example, the Naiyāyikas argue for the omniscience of the creator by frst establishing that an agent initially makes a binary combination of the atoms possible; and • abhyupagama siddh ānta (presumed conclusive view) is the provisional acceptance of a conclusion of the other. For example, when the opponent, in this case the M īmāṃsakas, establish that sound is a substance, the Naiyāyikas respond as follows: “We are not going to challenge this thesis; however, for the sake of discussion let us take the thesis—either sound is eternal or non-eternal—for granted.” The hope is that the idea of the substantiality of sound will eventually be refuted if both alternatives (eternal and non-eternal) are set aside. Such a provisional acceptance of a conclusion of another party is called “abhyupagama siddh ānta,” which clearly has the structure of a hypothetical argument of the form “if S then either p or not-p,” but if both alternatives, p and not-p, are shown not to apply, then the hypothesized premise must be wrong. Avayava means “member” or “premise.” A syllogism consists of fve members or premises. I have already discussed members in the context of the fve members of an inference. Nir ṇaya is the ascertainment of the truth attained by pram āṇas (means of true cognition) and tarka (hypothetical argument).60 It represents the removal of all preceding doubts, after an examination of the views for or against a doctrine. Vāda stands for analytic consideration to ascertain the truth.61 Similar to nir ṇaya, it also proceeds with the help of pram āṇas and tarka and uses arguments which are stated formally in the form of a fve-membered syllogism. The goal is not to refute any established theory but rather to arrive at the truth. In vāda, each of the parties involved in a discussion—the proponent as well as the opponent—attempts to establish his own position and refute the position of the other. Jalpa is wrangling in which both parties involved aim to defeat each other, but there is no attempt to ascertain the truth.62 Given that the goal is to defeat others, it involves the use of invalid arguments and reasons. (Lawyers usually use such arguments.) Vita ṇḍā is a kind of debate in which the proponent does not aim to establish his own position, but simply aims to refute the position of the others.63 Thus, whereas in jalpa each party’s goal is to establish his/her 228 T H E N YĀYA D A R Ś A N A 13 14 15 16 respective position and to gain victory over the other, in vita ṇḍā, each party tries to win by simply refuting the position of the other. It roughly approximates “sophistry” of Western logic. Hetvābh āsas: Gautama defnes “hetvābh āsas” as a “fallacious probans” because they do not possess all the characteristics of true probans, but they seem suffciently similar to probans (hetu or middle term).64 Hetvābh āsa is not a defective hetu (middle term), but rather a “seeming” or a “pseudo” hetu. The existence of a hetvābh āsa prevents an inference from taking place. Let me give an illustrative example: The inference “the hill has smoke because it has fre” is fallacious because the relationship between the hetu (smoke) and the sādhya (major term, fre) is not invariable. That is, though the hetu fre is present wherever smoke (sādhya) is present, it is also present where smoke is absent. In other words, the hetu fre is present both in a similar and in a contrary instance: There is fre on the hill which possesses smoke (a similar instance); and it is also present in a red-hot iron, which lacks smoke (a contrary instance). Given that the hetu is present in a contrary instance, it lacks invariable concomitance with the sādhya fre. So, the hetu impedes the emergence of the right cognition of vyāpti, the invariable concomitance.65 This is the fallacy of “common” (sādh āra ṇa) hetu in the sense that it is common to both a similar and a contrary instance. Thus, in an inferential process hetvābh āsas do not bear so much upon the form or the structure of the inference as upon the possibility of the resulting cognitions, which once obtained stops the inferential process. In chala one of the parties to a dispute—after failing to give a good argument against his opponent—advances irrelevant or pseudo replies.66 Here one tries to contradict another person’s argument by giving an unfair reply. The respondent contradicts a statement by taking it in a sense other than the one the speaker intended. In other words, when a person, say, X, cannot respond to a fairly strong argument that Y provides, X may contradict Y’s statement by taking it in a sense that was not intended. For example, Y may say “nava-kambala” meaning that the boy has a new blanket, and X unfairly objects and points out that the boy has nine blankets, because the compound “nava-kambala” is ambiguous. Jāti stands for all those futile arguments advanced by one party against the other, which instead of destroying the opponent’s position really contradicts the position of the one who advances those arguments.67 It consists in advancing a futile argument based on similarity or dissimilarity between things. For example, in trying to meet the argument “sound, being an effect, is non-eternal, like a jar,” the opponent may argue that the sound is eternal like sky because “sound shares with the sky the property of being incorporeal.” This is jāti. The Naiyāyikas enumerate twenty-four jātis. Nigrahasth āna 68 is the last entity in the Gautama’s list. “Nigraha” means “defeat” and “sth āna” means “place,” so that it leads to the fnal defeat of the proponent or the opponent. It includes different kinds of arguments 229 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS resulting in the fnal defeat of one of the parties. Gautama in the second chapter of the NS lists twenty-two such arguments. This list of the entities (it must be clear that these are entities in a highly abstract sense) shows what really occurs between the parties of a dispute, beginning with doubt and ending with ascertainment of truth, defeat of one of the parties and the victory of the other. Such an argumentative tradition, since ancient times, was an integral part of the rational discourse of Indian philosophers. It must also be evident that the concept of reason implicit in these discussions makes reason inseparable from proper, precise, goal-oriented use of language and the intersubjective discourse. IV Self, Bondage, and Liberation In the chapter on the Upaniṣads, we saw that it takes cit or consciousness to be the same as ātman. For the Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika school, however, ātman includes both the fnite individual selves (and souls) and the infnite soul, i.e., God. It is worth repeating that in the list of prameyas (discussed in the previous section) ātm ā appears frst, and the list also includes the body, the sense organs, the objects (of these senses), intellect (buddhi), mind (manas), action, (pravṛtti), defects (do ṣa), the succession of birth and death (pretyabh āva), fruits (phala), suffering (dukkha), and release (mok ṣa). Vātsyāyana states that the self is the seer, the enjoyer, and the experiencer of all things and the body is the locus of activity, senses, and object.69 The goal of any activity is to promote what is good and shun what is not conducive to good. Activity does not belong to inanimate objects; it can only belong to a fnite body. Similarly, body is the locus of the sense organs, and in so asserting, NSBh is emphasizing not the object per se, but pleasure and pain they produce. In other words, pleasure and pain belong to the self when limited by a body. After this list of entities, the next s ūtra proceeds to inform us how the “self” (or ātman) is known.70 We are informed that the self is too “subtle”; it cannot be perceived by any of the senses. Such judgments as “I am happy,” “I am sad” do not provide any knowledge of the true nature of the self. Thus, the question arises: How is the self known? The Naiyāyikas argue that the self is inferred from the qualities of pleasure, pain, desire, hatred, effort, and consciousness. These six are the specifc qualities of the self and they belong only to the self. Of these six, desire, effort, and consciousness belong to both fnite selves and the infnite self, i.e., God; hatred and pain belong only to the fnite selves; and the sixth, namely, happiness, belongs to both the fnite individuals and God, though God’s happiness is eternal, while the happiness of fnite individuals is non-eternal. The Naiyāyikas take great pains to demonstrate that consciousness is a quality neither of the body, nor of the sense organs, nor of an action; it is rather a quality of the self, which exists independently, and is different from the body, 230 T H E N YĀYA D A R Ś A N A the senses, mind, and consciousness. The self, on their theory, is eternal; it is neither produced nor destroyed. Though consciousness is a quality of the self, it nevertheless is not an essential quality of the self, which explains why in deep sleep or coma one does not possess consciousness; so, the self may exist without consciousness. The self, however, can have consciousness under suitable conditions, which arises in a self when the appropriate causal conditions are present, i.e., when the self comes in contact with the mind, the mind with the senses, and the senses with external objects. (These contacts are needed in all kinds of cognition, including testimony and inference.) In other words, the self, though eternal, is by itself unconscious, and so is not different from such material objects as table and chair, except for the fact that the self alone can have consciousness. In the state of liberation, the soul is released from all pain and suffering. In this state the soul does not have any connection with the body. So long as the soul is associated with a body and the senses, it is not possible for it to attain liberation. If the body and the sense organs are there, there would be contact with the undesirable objects giving rise to the feelings of pleasure and pain. Once the association between the body and the soul is severed, the soul would have neither pleasurable nor painful experiences. Liberation is the cessation of pain; it is absolute freedom from pain. It is the summum bonum, the supreme good, in which the soul is free from fear, decay, change, death, and rebirth; it is bliss forever. True knowledge of the distinction between the self and the not self is essential to attain liberation. To gain this knowledge, one must hear (śrava ṇa) the great sayings of the scriptures about the self, establish it by manana (refective thinking), and meditate on the self (nididhyāsana) following yogic techniques and practices. When one realizes that the self is distinct from the body, one ceases to be attracted by material things, one is no longer under the infuence of desires and passions that prompt an individual to undertake wrong actions and steer them in the wrong direction. One’s past karmas are exhausted, the connection with the body ceases, there is no pain, and that is mok ṣa. V Concluding Remarks So far, I have given a quick sketch of the Nyāya epistemology and ontology. The school provides a conceptualization of our ordinary concept of the world as consisting of many things. Perhaps, this pluralism, we can safely say, is based on the way the Naiyāyikas use the category of difference. I will highlight important features of the Nyāya logic before concluding this chapter. 1 Western formal logic ever since Aristotle has concerned itself with laying down the principles of formal validity, such that a perfectly valid syllogism may have false premises and a false conclusion. However, to my knowledge, from the beginning, Indian logic never entertained this 231 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS 2 freedom of formal thinking from all constraints of material truth. The Indian syllogism, if I may call it “syllogism,” is not simply concerned with the formal validity of an inference, but also with the material truth of the premises. They introduce, besides the middle, the major, and the minor terms of the Aristotelian syllogism, a fourth term, d ṛṣṭānta, i.e., example, and accordingly a premise, which is “existential instantiation” (EI). This requirement rules out the possibility of considering only formal validity to the utter exclusion of material truth. These innovations and their consequences make the Naiy āyika theory of inference a part of the theory of knowledge; it becomes a theory of how based on the present perception and past experiences we can extend our knowledge to new cases. The idea of mere thinking as distinguished from knowing did not play an important role. Indian logicians did not develop purely symbolic logic independent of content in its logical analysis. Even Nyāya, in its later phase, i.e., in the Navya-Nyāya tradition, during the time of Ga ṅgeśa, elaborated language to accurately express the premises of a syllogism. However, they applied the tools and the technique to propositions and objects from every domain, for example, perception, religion, aesthetics, and law. To elaborate further, I will consider the simplest case of a perceptual datum, a physical object having a sensory quality, for example, color. Let me choose for my example, a blue jar in front of me. I normally describe it by saying that “this jar is blue.” The Navya-Nyāya believed that it is necessary to make use of certain special techniques to describe this object accurately. The purpose was to fnd an exact expression which is true of this and only this object and did not extend to other objects not intended. An ontological analysis of the blue jar would yield such entities as substance, a color, and the relation between the two. Navya-Nyāya focused not on the ontological analysis but on the cognition “this jar is blue.” In this analysis, there are two guides: The linguistic articulation, and my inner perception or experience of that outer perception. An analysis of cognition reveals that all the components of the cognition are not articulated; there are unarticulated cognitive contents. There are on the Navya-Nyāya account three kinds of cognitive contents: Those which function as the substantives or qualifcandum; those which function as predicates, sometimes called “qualifers” (vi ṣayat ā); and those which function as relations. On the Navya-Nyāya theory, the word “this” which articulates a content does not articulate what points to another content, namely “thisness.” So, the content “this” functions as qualifed by “thisness,” but “thisness” is not an expressed content, because if it were so, then it would point to another unexpressed content, riding on its back as it were, such as “thisness.” Likewise, the content “ jar” is qualifed by the content “ jarness” (gha ṭatva), though it is not linguistically articulated. The same characterizes “blue.” So, in this cognition “this” is qualifed by “thisness,” pitcher by “pitcherness,” and blue by “blueness,” 232 T H E N YĀYA D A R Ś A N A which is discerned when we understand the language or the meaning of the words. Accordingly, we have three complex contents: a b c 3 4 “this “qualifed by “thisness,” “pitcher” qualifed by “pitcherness,” and “blue” qualifed by “blueness.” The entire expression “this pitcher is blue” articulates not these three complex contents, but a unitary content in which these three appear in a certain order by a chain of epistemic, not ontological, relations. Like all relations, though not articulated, we must posit them to account for the unity of meaning. The Navya-Nyāya here introduces many such relations among cognitive contents, and they go on expanding and positing these appropriate epistemic relations. The entire complex content and the appropriate relations belong to a cognition which belongs to a self. The Navya-Nyāya uses this technique to analyze inferential cognitions, and cognitions derived from language alone. Entering into more complexities, the system uses more effectively negations and negative descriptions to exclude what was not intended rather than to positively describe what was intended. There is no need to detail for beginning students of Indian logic the complexities of the Navya-Nyāya technical language; however, the above will give students a favor of the Navya-Nyāya technique and highlight an important difference with the Western symbolic logic. The Naiyāyikas also inform us that we perceive universals under appropriate conditions. Shall we then say that the Nyāya position is still an unmitigated empiricism? It is also worth remembering that the notion of sensory contacts goes far beyond perceiving universals. In an instance of extraordinary perception that “the snow is cold,” the Naiyāyikas hold that one visually perceives that snow is cold. The Naiyāyikas do not stop here. They further argue that I perceive not only the snow, but also the snowness present in it, and, that in such a perceptual cognition, I also see all other individuals in whom the same universal is present. So, the Naiyāyika account of perception is not empirical in the strictly Humean sense. Does the knowledge gained, say, in an inference, go beyond the sensory input? In an inference, for example, one sees a column of smoke on a distant hill, remembers the generalization having seen their co-presence in his own kitchen, recognizes that the present perceived smoke falls under the generalization, and infers that there is fre on that hill. The questions worth refecting are: In this sequence of cognitive events, which steps are necessitated causally by the preceding sensory inputs? Alternately, is there a step where cognition goes beyond the data in the causal chain? A review of the fve constituents of the inference reveals “wherever there is smoke there is fre.” It is a new realization of the cognitive process as it goes beyond the data and anticipates possible future experiences. 233 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS Another cognitive step, which is not a mere causal sequence, is the application (nigamana) of that generalization to the present case. The point is: It is at these crevices the Naiyāyikas go beyond the purely empiricist understanding of cognition. The above discussion informs us that in Indian thought the logical and the real do not constitute two different worlds; they are mixed together in such a manner that the logical, though arising out of the real, creates the semblance that it is a separate structure. There is no stand-alone rationality, i.e., no rationality independent of or detached from the empirical, and no empirical that does not exhibit a logical structure. Study Questions 1. Explain the nature of knowledge according to Nyāya. 2. Explain the distinction between pram ā and apram ā. Critically discuss the three kinds of apram ā. 3. Defne perception. Outline the distinction between the non-conceptual and the conceptual perception. 4. Explain the fve constituents of the Nyāya inference. How does the Nyāya account differ from the Aristotelian syllogism? Do you think that the two premises of the Nyāya inference are superfuous? Give reasons for your answer. 5. Explain the Nyāya theory of extrinsic validity and invalidity. How does the Nyāya account differ from the Advaita account? 6. Explain the Nyāya conception of the self, bondage, and liberation. Does it make sense to say that consciousness is an accidental quality of the self? Substantiate your position with rational arguments. 7. The sample case given below concerns the darśanas you have studied in this part of the book. Read the following sample case, and answer questions given below. A Sample Case: Appeal of Three Brothers to the Fourth Brother not to Squander his Inheritance Donald (an atheist, hedonist), Dylan (a follower of M īmāṃsā), Robert (a follower of Sāṃ khya -Yoga doctrines), and Avi (a follower of Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika) are four brothers. Their grandmother died and left them a large sum of money. They are having a discussion regarding how best to spend their inheritance. Donald would like to throw big parties, buy beer for his friends, and waste his entire fortune. Dylan, Robert, and Avi would like to donate a portion of their inheritance to charity, designate some funds for scholarships for minorities, pay long-standing debts, etc. They believe that Donald should be concerned not about this life only, but about his afterlives. So, the brothers begin educating Donald about their own beliefs and practices, i.e., about karma, rebirth, and 234 T H E N YĀYA D A R Ś A N A mok ṣa (liberation, the state of positive bliss). Donald, being a hedonist and materialist, is strongly opposed to the beliefs and practices of his three brothers. Donald (Atheist and Hedonist Perspective) I am a hedonist; I do not believe in the existence of any god or afterlife. There is no higher goal than pleasure, and there is no better object to be pursued than desire. All of you believe in the immortality of the soul, but how do you know that there is a soul, and it is immortal? How do you know that there is afterlife? All of you believe in mok ṣa, but you cannot agree upon how to achieve it? Theses you are asserting are ambiguous, and, at times, contradictory. He addresses all three brothers and asks them to elaborate the following theses. Dylan (Follower of Mīm āṃsā Perspective) • • You perform all sorts of ritualistic actions to go to heaven, to exhaust accumulated karmas. Therefore, actions are not done without any desire for the results of the actions. Ap ūrva–the invisible force, the invisible results of works which accrue to the doer, the performer of a sacrifce–is a fgment of imagination. To claim that actions performed now produce an “unseen potency” (ap ūrva) which yields fruits in the future is meaningless. Robert (Follower of S āṃkhya Perspective) • • • You tell me that prak ṛti (the objective principle) is totally autonomous; however, though prak ṛti is totally other than puru ṣa, it is also “for the sake of puru ṣa.” Does not this “being for” work against the autonomy of prak ṛti? It is not plausible to claim that puru ṣa is eternally free, but to strive after freedom, it gets entangled with prak ṛti. Liberation as “alone-ness,” a total lack of inter-subjectivity, is not appealing. Why would any person fnd “alone-ness” appealing? Why would you ask me to pursue it? Avi (Follower of Nyāya Perspective) • • • • You tell me that the self, though eternal, by itself is unconscious. I am baffed by the Nyāya thesis that consciousness is not an essential quality of the self. If consciousness is not an essential quality of the self, then the self is not different from such material objects as tables, chairs, etc. When the self’s connection with the body ceases, and one’s past karmas are exhausted, mok ṣa, the summum bonum—which is bliss forever—is realized. The concept of “karma” is a fction of imagination. I do not believe in rebirth, and my bliss is enjoying life on this earth. 235 THE ANCIENT DARŚANAS In your answer, try to alleviate Donald’s concerns and answer his questions. You are free to formulate your answer in any manner you wish; however; your goal is to persuade Donald not to squander away his inheritance. It is important that you include in your answer a discussion of key philosophical concepts, viz., M īmāṃsā ap ūrva, Sāṁ khya liberation as “alone-ness,” and the Nyāya conception of the self as eternal, etc. Suggested Readings For Nyāya perception, see B. K. Matilal, Perception (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986). For logic and inference, see B. K. Matilal, The Character of Logic in India (Albany: SUNY Press 1998); Kisor Kumar Chakrabarti, Classical Indian Philosophy of Mind: The Nyāya Dualist Tradition (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1999). For English translations, see Sir Ganganatha Jha (tr.), The Nyāya-S ūtras of Gautama (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1999), Vols. 1–4; Karl H. Potter (ed.), Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies, Nyāya-Vai śe ṣika (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1977), Vol. 2. Potter’s volume translates some important texts, introduces basic conceptual distinctions, and introduces early philosophers of this school. For a concise introduction to Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika’s central epistemological and ontological principles, see Tarka-Sa ṃgraha of Anna ṃbha ṭṭa with D īpīk ā and Govardhana’s Nyāya-Bodhinī (TSDNB), edited with critical explanatory notes by Yashwant Vasudev Athalye, Bombay Sanskrit and Prakrit Series, No. 55 (Bombay: R. N. Dandekar, l963); The Elements of Indian Logic and Epistemolog y, based on a portion of Tarka-Sa ṃgraha of Anna ṃbha ṭṭa with D īpīka (TS), with translation and explanatory notes by Chandrodaya Bhattacharyya (Calcutta: Modern Book Agency Publishers, 1962), §7. The last two works are based on Tarka-Sa ṃgraha of Anna ṃbha ṭṭa; however, the frst version contains many Sanskrit words in the notes which might pose problems for a beginner. Students interested in Navya-Nyāya may consult Stephen Phillips, Epistemolog y in Classical India: The Knowledge Sources of the Nyāya School (New York: Routledge, 2012). 236 Part VI SYSTEMS WITH GLOBAL IMPACT I The Buddhist Schools II The Vedānta Darśana 1 Advaita Vedānta 2 Viśiṣṭādvaita 13 THE BUDDHIST SCHOOLS I Introduction After the death of the Buddha, Buddhist monks began debating the details of his teachings and practices, and, as a result of their inability to reach consensus, the basic ethical-philosophical teachings of the Buddha went through a long process of development. We may think of this as three turns of the dharma wheel, each turn spanning a period of 500 years. Four Buddhist Councils convened—the frst, shortly after the death of the Buddha, and the fourth, in the frst or the second century CE—to formulate the Discipline of the Order, to debate controversial points, and to clarify and compose doctrines. Initially, followers of the Buddha were divided into two groups: Sthavirāvdins (followers of the Doctrine of the Elders) and the Mahā sāṁghikas (non-professional representatives of the Great Assembly). As the controversy over interpreting the Buddha’s doctrines continued, Sthavirāvdins and Mahā sāṁghikas were further divided into more new schools, the most important of which became known as the Sarvā stivādins, i.e., followers of the doctrine that “all is real.” In fact, the task of the Fourth Council was to arrange and systematize the doctrines of the Sarvā stivādins. However, owing to doctrinal differences, Buddhist schools continued to proliferate, giving rise to as many as thirty schools in India, China, Tibet, and Japan. The history of the origins and development of these divergent sects is too diffcult to trace here. For our purposes, it is enough to note that these schools were broadly divided into two branches: The Ther āvāda, also known as Hīnayāna (“Lesser Vehicle”) school, as it was somewhat pejoratively called by the emerging second branch, i.e., the Mahāyāna (“Greater Vehicle”) school. The Buddha’s refusal to answer metaphysical questions—Is there a God? Is soul the same as body? Are the soul and the body different? Is the universe eternal? Is the universe non-eternal? Is there a God?—created a lot of confusion and dissension among his followers. Some held that the Buddha’s refusal to address these questions implied a denial of the existence of God, reality, and the means of knowing it; some took it to be a sign of empiricism, an approach to talking about reality that relies upon the observable world only; others found in this silence grounds for idealism, the position that reality is a mental construct. 239 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T The Sarvā stivādins argued for the reality of all things;1 they took both the mental and the non-mental to be real. Regarding how we know of the external world’s existence, the two sub-schools of Sarvā stivāda—the Vaibhāṣika and the Sautrāntika—were divided. While the Vaibhāṣikas held that we directly perceive the external world, the Sautrāntikas denied this, arguing that we do not directly perceive external objects but only infer their existence. In contrast, the Mādhyamikas argued that there is no reality at all, neither mental nor non-mental; all is void (śūnya). The Yog ācārins described reality as a process of mental construction. Thus, we have four main schools of Buddhism, which in chronological order are the Vaibhāṣika, Sautrāntika, Mādhyamika, and Yog ācāra. These four schools are usually correlated with a familiar, though misleading, distinction2 between the two phases of the Buddhist religious schools mentioned above, the Hīnayāna and the Mahāyāna. It is traditionally maintained that the Vaibhāṣikas and the Sautrāntikas belong to the Hīnayāna branch, while the Mādhyamika and the Yog ācāra belong to the Mahāyāna branch. In any event, these four schools have much philosophical importance, and, in such a short exposition as this, it is diffcult to do justice to them. So, without going into the details of the Buddhist hermeneutic, in this chapter, I will discuss the basic doctrines of these four schools. II The Vaibhāṣika School of Buddhism The Abhidharma forms the foundation of this school of Buddhism. This school is called “Vaibhāṣika” because it follows the commentary Vibhāṣā on Abhidharma Jñānaprasthāna. The term “abhidharma” literally means “with regard to the doctrine.” In time, however, Abhidharma teachers began systematizing their teachings and came to be known as the “superior” (abhi) “doctrine” (dharma), i.e., the study of the dharmas. This work also includes a comprehensive description of the Buddhist doctrines, ranging from cosmology and the theories of perception to the issues surrounding moral problems, the virtues to be cultivated to attain nirvāṇa, yogic practices, and the meaning and the signifcance of rebirth. Originating primarily in Kāśhmīr, some of the principal teachers of the Vaibhāṣika school were Dharmatrāta, Ghoṣaka, Vasumitra, and Buddhadeva.3 The Vaibhāṣikas were realists (dharmas do not depend on consciousness), pluralists (dharmas are distinct and irreducible), and nominalists (universals are mere concepts). The characteristic doctrines of this school are discussed in this essay. The Vaibhāṣikas hold that we directly perceive the external objects. This is like the direct, common-sense realism of Western philosophy, according to which the color that I perceive is itself the color of the object in front of me. My mind directly knows the external world. We infer fre upon seeing the smoke because in the past we have perceived smoke and fre together. One 240 THE BUDDHIST SCHOOLS Fundamental Postulates 1 Everything exists, mental and physical; this includes the three dimensions of time. 2 We directly perceive the external world. 3 Reality is a series of instantaneous events. (“To exist is to be causally effcacious.”) 4 The inner self consists of a series of changing particulars. 5 There is no permanent substance or universal (sām ānya) instantiated in particulars. 6 Basic substantial constituents called “dharmas” are real. 7 Seventy-fve dharmas are mentioned in Abhidharmakośa. 8 Phenomenal existence is constituted by seventy-two dharmas, which are conditioned by ignorance and which result in suffering. 9 There are three unconditioned dharmas that are not subject to deflements. 10 There is a real transformation of the conditioned into the unconditioned through the experience of insight. who has never perceived a fre would not be able to infer fre upon seeing smoke coming out of a building. The world is real; it exists independently of our knowledge and perception of it. There is no distinction between the world as it is and as it appears to us. One of the most important doctrines of the Vaibhāṣikas is k ṣanikavāda (momentariness), the thesis that everything real is instantaneous. Both mind and matter are momentary. Becoming is real; there is neither being nor non-being. Before proceeding, let us pause, and recall the early theory of momentariness. Early Buddhist texts analyze the process of change in terms of arising and passing away. All compounded (conditioned) things are said to come into existence and immediately pass out of existence. This traditional theory does not assert duration, nor a static phase between the arising and the cessation of existence. This doctrine of momentariness has been interpreted in different ways by different sects of the Buddhist tradition. Some extend this process of change to three stages: Origination, passing away or dissolution, and decay or “change of what exists.” The Vaibhāṣika school extends the process to four stages—they construe “decay or change of what exists” as signifying two distinguishable moments: Existence (duration) and decay. The main premise of the Vaibhāṣika doctrine of momentariness is that to exist is to be causally efficacious. Everything real arises, produces its effects, passes away, and is replaced by its successor. Any alleged permanent substance cannot be causally effcacious, because what is permanent will never arise to produce its effects, nor pass away and be replaced by 241 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T something else. Insofar as substances are defned as permanent and unchanging, then they cannot exist. Reality is a series of instantaneous events; there is no permanent substance, just as there is no universal (sām ānya) instantiated in a class of particulars. There is only similarity between momentary events, but—mistaking similarity for identity—we regard similar particulars as possessing an identical feature in common. The illusion is sustained when we give particulars the same name (“ jar,” “tree,” “river”). The identity of a name together with the resemblance among particulars creates the illusion of real universals. Not only the external world but also the alleged inner self consists of a series of changing particulars. The self, Vaibhāṣikas hold, is not a substance; it consists of fve different, interconnected, dynamic series of material bodily changes, thoughts, feelings (vedan ā), volitions and forces (sa ṁsk āras), and events of consciousness (vijñ āna). These fve series, like fve ropes, are intertwined in a complicated manner, creating the illusion of an identical inner self. There is no lasting, underlying substance; the series is held together by causality. The Vaibhāṣikas accept the reality of the basic substantial constituents called dharmas.4 In Buddhism, the term usually refers to the teachings of the Buddha; however, in the abhidharma context, a dharma denotes the basic, most primary constituent present in experience. An element that cannot be further analyzed is a real existent and has its own self-nature (svabh āva); it exists “in and of itself.” A physical object such as a chair, however, is an aggregate of impermanent, momentary, duration-less dharmas. Citta • • • • The term citta is derived from the Sanskrit verb root cit, meaning “to think,” and is generally translated as “mind” or “thought.” Caitta refers to the content of thought (that which is thought). In early Buddhist literature, citta was used synonymously with manas (mind) and vijñ āna (consciousness), and it played a central role in Abhidharma psychological analysis. Cittam ātra (“mind only”) is one of the important concepts of the Yog ācāra school. Yogācārins explain citta in terms of an ālaya-vijñ āna or “storehouse consciousness.” Sarvā stivādins classify citta as one of their seventy-fve dharmas. Abhidharmakośa discusses seventy-fve dharmas divided into conditioned (“sa ṁsk ṛta,” literally, “co-operating”) and unconditioned (“asa ṁsk ṛta,” literally, “non-co-operating”) dharmas.5 The conditioned dharmas arise and perish, but the unconditioned, such as empty space, are eternal. Conditioned dharmas are classifed into fve groups: Form (r ūpa), mind (citta), mental faculties, forces not 242 THE BUDDHIST SCHOOLS concomitant with the mind, and unconditioned dharmas. Of these, form (r ūpa) includes eleven dharmas: Five sense organs, fve sense objects, and unmanifested matter; mind (citta) includes forty-six mental functions and fourteen forces which are not concomitant with the mind. There are three unconditioned dharmas: Nirvāṇa, empty space (āk āśa), and meditative emptiness of consciousness (apratisa ṃkhyānirodha). In short, dharmas refer to such elements as mind, matter, reality, and ideas; they refer in general to the basic factors or elements of experience. It is not feasible to go into an analysis of the Sarvā stivādin’s seventy-fve dharmas here. For our purposes, it would suffce to note that the conditioned dharmas constitute phenomenal existence; they are subject to the law of causality, and in their fow, they co-operate and perpetuate phenomenality. The unconditioned dharmas, however, are not subject to the causal law. Dharmas are also classifed into the morally bad and good, the impure and pure. In this sense, the same dharmas are infuenced by ignorance or wisdom (prajñ ā). Unconditioned dharmas are pure in the sense that they are free from deflements (kle śas), which cause body and mind to suffer. Greed, hatred, delusion, pride, wrong view, doubts, sloth, and distractions are the eight deflements, which corrupt any dharma to which they get attached. Conditioned elements, when defled, taint each other; for example, lust may taint wisdom, or an object of cognition which arouses passion. Buddhist writers classifed deflements into one hundred and eight, and proclivities into ninety-eight. The Vaibhāṣikas hold that the Buddha’s saying “all are impermanent” refers only to the conditioned dharmas, but not to the unconditioned dharmas. There is a real transformation of the conditioned into unconditioned through insight. The dharmas conditioned by ignorance cause pain and sorrow, and the same dharmas—when separated and suppressed by ethical-spiritual discipline and knowledge—become nirvāṇa and apratisa ṃkhyānirodha (cessation without a residue). Space (āk āśa), however, neither obstructs nor is obstructed; it is empty. Thus, these dharmas combine in different ways and account for the phenomenal existence and the world process. In keeping with the Sarvā stivādins belief in the existence of everything (sarva asti), the mental as well as the non-mental, and citing the Buddha’s assertion that the past, the present, and the future exist, the Vaibhāṣikas argue that not only the present but the past and the future are also real. They admit six categories of reality: The past, the future, the just arising, the cessation with a residue (pratisa ṃkhyānirodha), the cessation without a residue (apratisa ṃkhyānirodha), and space (āk āśa). For the existence of the past and the future, they advance the argument that there cannot be any knowledge, if there is no “objective support” (ālambana); since there does arise knowledge of the past and the future ālambana, the past and the future must therefore exist. There is an important philosophical problem with the above position inasmuch as the Vaibhāṣikas tried to combine two seemingly incompatible positions: On the one hand, they accept that nothing is eternal, that all reality is momentary; on the other hand, they make every moment eternal, inasmuch 243 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T as each dharma, the past and the future, like the present, is or exists. When the Vaibhāṣikas were asked how they could hold both that an object exists in three points of time, and that nothing endures, different Vaibhāṣikas gave different answers. Among these, four are worth noting.6 Vaibh āṣika Buddhist Views of Momentary Existence • • • • Dharmatrāta advanced the thesis of differences in forms (bhāvas): An entity, as it passes from the present to the past, remains the same substance (dravya); only its form (bhava) changes. For example, gold may be fashioned into different forms of jewelry, but the substance remains gold. Ghoṣaka held that what changes is characteristic or aspect (lak ṣa ṇa), e.g., a person is attached to a woman, but gradually becomes non-attached to her. Vasumitra contended that it is state or position (avasth ā) that changes, not the substance. This is analogous to the value of the numeral “0” contingent upon its placement in a numerical expression (e.g., the hundreds or thousands place). Buddhadeva held it is the relations that change depending on the context, not substance. For example, the same woman may be a daughter in relation to one person, a wife in relation to another, etc. The frst view looks like the Sāṃ khya position. The three temporal positions are related to three different relations in terms of causal effcacy: When there is no effcacy, the entity is not yet; when it is causally active, the entity is present; when there is no causal activity, the entity is past. If we never perceive external objects, as the Sautrāntikas argue, then we would not be able to infer them simply from their form (āk āra). The Vaibhāṣikas’ minute analytical listing of entities bears testimony to their remarkable powers of subtle observation, faithful articulation, and openness to new metaphysical thinking. In this school, ontological and valuational judgments are inseparably linked; every element of reality is either good or evil; the theory of causality is as much about values as it is ontology. The Vaibhāṣikas’ maintained that conditioned and unconditioned dharmas are totally different. There are two levels of reality, sa ṃsāra (empirical realm) and nirvāṇa (beyond empirical, truth)—neither is “unreal.” This dualism between the two levels of reality became a matter of great controversy among Buddhist schools. The Mādhyamikas argued against the Vaibhāṣika position, holding that sa ṃsāra and nirvāṇa are the two sides of the same coin. The Sautrāntikas accepted only the reality of sa ṃsāra but no separate reality of nirvāṇa, which on their view is a mere negation and not a positive entity. 244 THE BUDDHIST SCHOOLS The Yog ācāras held that sa ṃsāra is not real, only nirvāṇa is. Thus, it is not an exaggeration to say that the Vaibhāṣikas laid the foundation for the subsequent discussion of many philosophical issues among Buddhists and nonBuddhists alike. III The Sautrāntika School of Buddhism “Sautrāntika” literally means “those who accept the authority of the s ūtras.” Specifcally, they accept the Vinaya and the Sutta pi ṭakas as containing the Buddha’s words. The founder of this school is taken to be Kumāralāta of Tak ṣaśila. The main literature of this school seems to have been lost. Our knowledge of the Sautrāntika doctrines is derived from what the followers of other schools say about them in the process of refuting them. Many of the Sautrāntika doctrines are known to us from the Abhidharmakośa of Vasubandhu, who prior to converting to Mahāyāna was a Sautrāntika. The Abhidharma texts take Kumāralāta, Dharmatrāta, Buddhadeva, and Śrelāta to be the “Four Sons” of the Sautrāntika. Although they are said to belong to the Hīnayāna school, Sautrāntikas are often considered as marking the beginnings of Mahāyāna. The Sautrāntikas were realists, pluralists, k ṣanikavādins, and nominalists. Fundamental Postulates of Sautrāntika 1 2 3 4 5 6 Both the mental and the non-mental are real. The present is real, but the past and future are not. Conditioned or composite dharmas are not real. There are no static moments. We do not directly perceive objects, as both objects and consciousness are impermanent; we directly cognize a momentary impression or representation of an object and infer the existence of the object on that basis. The theory of “substance” or “own-nature” (svabhava) is just the rejected theory of ātman by another name. The Sautrāntikas accept the reality of both mental objects or phenomena— such as pleasure and pain—and the non-mental, including tangible external objects.7 The object of consciousness is different from, and exists apart from, consciousness itself. As for our knowledge of external objects, we do not perceive them directly, but infer their existence from our perceptions. In the cognition of an object, the mind receives a copy or impression of that object, and consciousness infers the existence of the object from this copy. This account is known as “representationalism” or “the copy theory of ideas,” and it “resembles” Western Lockean representationalism.8 245 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T The Sautrāntikas reject the reality of past and future, because their acceptance would mean regarding the past or the future as present, which would be logically inconsistent. The Sautrāntikas affrm a process theory of existence, in which every dharma is momentary, arising and immediately perishing. A dharma’s being is its process; there is no substance called “arising.” Perishing, being an absence, is not produced—it is ahetuka (without cause). Only being is causally produced, not non-being. Therefore, while a dharma’s being is caused, once it arises, it then perishes of itself. Life is not a substance; it is a special ability (sāmrthya) which lasts for a defnite period. When a dharma arises, four conditioned entities (ana-lak ṣanas) co-arise with it: Arising-arising, existence-existence, decay-decay, and noneternity-noneternity. All conditioned entities have the marks of non-being becoming being and being becoming non-being. The Sautrāntikas reject the existence of conditioned or composite dharmas—these elements are not real. The very existence of the dharmas consists in their process, “stream,” or pravāha. There is no origin, existence, or perishing. Regarding the three unconditioned dharmas asserted by the Vaibhāṣikas, the Sautrāntikas argue that āk āśa (empty space) is nothing but the absence of anything tangible. Nirvāṇa is not a positive entity; it is mere absence. It is neither caused nor an effect. The same characterizes “cessation without wisdom”—it too is a negative entity. The Sautrāntikas departed from the Vaibhāṣikas on several points: The reality of the past and the future, the reality of the unconditioned or incomposite dharmas (āk āśa, nirvāṇa), and whether the external world is directly perceived or inferred. The frst of these disagreements is the most important. The Vaibhāṣikas hold that the past, present, and future are equally real, because a real present cannot be the effect of an unreal past, nor the cause of an unreal future; so, the past and the future are contained in the present, which explains why they hold that the present has duration, and that in the absence of duration, the present could not be causally effcacious to the arising of succeeding moments. The Sautrāntikas, however, argue that there is no causal relation between successive moments; each moment is replaced by the succeeding one. There is no causal relation between the preceding and the succeeding moment, the latter simply depends on the former. It is worth noting that though both the Vaibhāṣikas and the Sautrāntikas subscribe to momentariness, their understanding of “moment” (ksa ṇa) differs— for the Vaibhāṣikas, it is the last indivisible segment of time, while for the Sautrāntikas, it is the time it takes for a dharma to arise before perishing in the next moment. The Sautrāntikas argue that if this arising lasted for another moment, it would need another cause; however, the same cause cannot produce a new effect, given that it has already produced its effect. Consequently, the doctrine of momentariness (k ṣanikavāda) is transformed into a philosophy of process, because it does not make sense to say that every instant—even when it is gone and has not yet been—exists eternally. Additionally, the Sautr āntikas argue that their conception is closer to the Buddha’s doctrine of Dependent 246 THE BUDDHIST SCHOOLS Origination, as it distinguishes between conditioning and causing. In the twelvelink chain of the Dependent Origination, each link is both conditioned and that which conditions, but one link does not cause the other link. Finally, they argue that to attribute duration to instants is to assign them a sort of permanency which goes against the doctrine of Dependent Origination. Thus, arising and perishing are not two different processes, but rather a single continuous process. The second major point of difference between the Sautrāntikas and the Vaibhāṣikas concerns the reality of simple unconditional dharmas, namely, āk āśa and nirvāṇa. The Sautrāntikas reject that these two are unconditioned dharmas. They do not agree that empty space is real. It is not a positive reality; there is an absence of any tangible object. Likewise, nirvāṇa, which the Buddhist aspirant aims to attain, is a mere cessation comparable to the extinguishing of a lamp. If existence is dukkha (the First Noble Truth) and nirvāṇa is the nirodha satya, or the cessation of duhkha (the Third Noble Truth), then this amounts to the cessation of existence, so that a person after attaining nirvāṇa ceases to exist. There is simply a blank nothingness. It is to be noticed that many Western readers of Buddhism have wondered whether nirv āṇa is not simply an extinction of dukkha. Only the Sautr ā ntikas held such a view; no other school subscribed to this position. Even Nā g ā rjuna, in asserting that nirv āṇa is śūnya, did not affrm the Sautr ā ntika position. As we will see shortly, śūnyat ā, for Nā g ā rjuna, is not of the nature of simple negation. The third point of difference concerns our knowledge of the external world. The Sautrāntika position is that—while real objects exist outside the mind— they are not directly perceived, but inferred based on our momentary, fashing cognition of the form or impression that the object leaves behind. The Sautrāntika philosophy therefore came to be known as the theory of the inferability of external objects (B āhyānumeyavāda). Our perceptions of external objects depend not simply on mind, but on four conditions: Causes as a condition (hetupratyayat ā), an equal and immediately antecedent condition (samanantarapratyayat ā), an object as condition (ālambanapratyayat ā), and a predominating infuence as a condition (adhipatipratyayat ā).9 The object must be there to impart its form to consciousness; the mind must be able to receive the object’s form or impression, which includes sensory consciousness (tactile, visual, etc.). Auxiliary conditions in the environment (such as light) combine with the conditions of the object and the mind to facilitate perception of the object. When the object’s form is generated in our mind, what the mind perceives not that object, but a copy of the object in our own consciousness. In many ways, the Sautrāntikas and the Vaibhāṣikas laid the foundations for the emergence of subsequent schools that developed within the fold of Buddhism. According to Sautrāntikas, the existence of the external world is inferred, and this inference is subject to the constraints of our internal representations. Western writers have compared the Sautr āntika’s position to 247 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T Lockean representationalism, contrasted with the direct naive realism of the Vaibhāṣikas. We will shortly see that Vasubandhu rejects the Sautrāntika’s position, holding instead that consciousness apprehends only its own ākāra or form. The issue becomes whether this form of consciousness is derived from the supposed external object as the Sautrāntikas take it to be, or it is derived from the supposed ālaya vijñāna (storehouse consciousness) that the Vijñānavāda school asserts. The Sautrāntika’s position not only engendered the Vijñānavāda view that consciousness alone is real, but also the Mādhyamika dialectic that there is no origination or cessation, no coming-to-be or going-out, that everything is śūnya. IV The Mādhyamika School of Buddhism The Mādhyamikas follow the madhyama pratipad, or the Middle Path, of the Buddha. In his frst sermon, the Buddha illustrated this path by ruling out the behavioral extremes of self-indulgence and self-mortifcation. In Sanskrit lexicons, one of the words used for the Buddha is “advayavādin,” or “the one who asserts not-two.” What does this signify? The Mādhyamikas take “nottwo” to mean that one should avoid all extreme assertions: Of being and nonbeing, of self and non-self, of substance and process—in general, all dualistic affrmations—as well as extreme dispositions and behaviors, such as selfindulgence and self-mortifcation. Nāgārjuna is generally considered to be the founder of the Mādhyamika school. It is not an exaggeration to say that Nāgārjuna is the most important Buddhist philosopher after the historical Buddha himself, and one of the India’s innovative, enigmatic, and thought-provoking philosophers. Nāgārjuna lived 500 years after the Buddha’s death, during the transitional era of Buddhism when scholar-monks began debating Buddhist teachings and practices among themselves, as well as with non-Buddhist schools. Tradition maintains that Nāgārjuna was born in 50 CE to a brahmin family in Andhra Pradesh, South India. Many legends surround his name. According to some accounts, Nāgārjuna initially studied the Vedas and other important Hindu texts, but eventually converted to Buddhism. Numerous works have been attributed to Nāgārjuna. These works include public lectures and letters to numerous kings, in addition to metaphysical and epistemological treatises that form the foundation of the Mādhyamika school. But there is no doubt that his most important works are Mūlamadhyamakakārikā (MMK) with his own commentary and Vigrahavyāvartanī (VVT). One of the most important texts belonging to this era was Prajñ āpāramit ā, which literally means “transcendent insight or wisdom,” but usually translated as “Perfection of Wisdom.” The principal theme of this work is the notion of śūnyat ā (emptiness, voidness). Nāgārjuna analyzes this notion and develops its ramifcations systematically and clearly. Though Prajñ āpāramit ā has been commented upon by both the Mādhyamika and Yog ācāra schools of Mahāyāna Buddhism, in time it came to be used synonymously with the teachings of Nāgārjuna. 248 THE BUDDHIST SCHOOLS Fundamental Postulates 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Metaphysical theories proposed by divergent schools of thought, including Buddhism, are conceptual constructions; they are evidently incoherent and illogical. All things, ideas, and events are empty (śūnya); they have no essence or immutable defning property. Things can never be adequately explained either in terms of themselves or in terms of their relations to other things. All thinking presupposes the categories of “identity” and “difference,” but these categories are incoherent and have no referent. No entity or thing arises from itself, from not-itself, from both itself and not-itself, or from neither itself nor not-itself. Language is tautological; it is self-referential. Emptiness of concepts and theories does not entail the emptiness of reality. There are two levels of truth or reality: The conventional (sa ṃsāra) and the ultimate (nirvāṇa); higher truth is grasped in prajñ ā (direct intuition). The Buddha had refused to answer any metaphysical questions and characterized his teaching as the Middle Way; Nāgārjuna, puzzled by the Buddha’s silence and seeking some rationale behind it, took this silence to mean that reality could not be articulated by any of the commonly held metaphysical positions, e.g., the thesis of permanence and change, substance and causality, etc. Accordingly, Nāgārjuna rejected all such metaphysical positions and called his philosophy “Madhyamaka,” indicating a navigation away from theoretical extremes. In my discussion of the Mādhyamika school in this chapter, I draw mainly from the Mūlam ādhyamakak ārik ā, or Fundamental Verses on the Middle Way. It contains 448 verses divided into 27 chapters. The terse and the dense nature of these verses continue to generate signifcant philosophical dialogue up to this day. The central theses of this work revolve around the notions of śūnyat ā (emptiness) and niḥsvabh āvat ā (lack of inherent essence or absence of the essence of things). Nāgārjuna rejects the Vaibhāṣika doctrine of the dharmas and argues that all dharmas are foundationless. No dharma has svabh āva; that is, no dharma has its own self-nature, being, or essence. Nāgārjuna holds that things have no essence of their own, no immutable defning property; rather, all dharmas are dependent on one another. Collectively, these ideas form Nāgārjuna’s famous thesis of śūnyat ā (emptiness). It is important to remember here that Nāgārjuna 249 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T Śūnyat ā • • • • • Śūnyat ā is the noun form derived from the Sanskrit adjective śūnya: “empty, void, zero, nothing”; hence, it is usually translated as “emptiness” or “voidness.” Śūnyat ā is a complex Buddhist concept, which has been used in a variety of senses depending on its doctrinal context, referring variously to an ontological feature of reality, a meditative experience, or a phenomenological analysis of experience. In Therāvāda, “śūnyat ā” often refers to the non-self (the union of fve aggregates). In Mahāyāna, “śūnyat ā” refers to a lack of essence or intrinsic essence (svabh āva). Nāgārjuna equates emptiness with Dependent Origination. Given that according to the Buddha, all experienced phenomena (dharmas) are “dependently arisen,” Nāgārjuna argues that such phenomena are empty (śūnya). As phenomena are experienced, they are not non-existent; they do not possess any permanent and eternal substance. is rejecting not only the philosophical thesis that things have their own essence (such as cowness belonging to all cows) but also the brahman-ātman of the Upaniṣads, the puru ṣa and the prak ṛti of Sāṃ khya, and the nine substances (dravyas) of the Vaiśeṣika. Svabh āva • • • • • The term “svabh āva” literally means “own-being.” It means intrinsic nature, essential nature, or the essence of living beings. It is variously used as “essence,” “own-nature,” “self-nature,” “intrinsic existence,” “own-being,” “inherent existence” “essence,” “nature,” etc. The svabh āva of a thing does not change; it neither comes to be nor ceases to be. The concept of “svabh āva” plays an important role in Hindu and Buddhist traditions alike. 250 THE BUDDHIST SCHOOLS Rejection of svabh āva amounts to rejecting the identity of a substance, the presence of a universal in particulars, and any thesis which posits unchanging essences of things. In rejecting svabh āva, Nāgārjuna rejects all metaphysical positions advocated by his predecessors, the Buddhist and the non-Buddhist alike. Taking the Buddha’s doctrine of prat ītyasamutpāda (Dependent Origination) as his point of departure, Nāgārjuna uses a method known as prasa ṇga— very similar to reductio ad absurdum—to demonstrate that all perspectives about reality involve self-contradiction.10 Prasaṇga or Reductio ad Absurdum Prasa ṇga (reductio ad absurdum) is a method of analysis that exposes the inherent self-contradiction of any perspective to demonstrate its absurdity. The analysis consists in demonstrating that the proponent’s theses lead to absurdity even when one uses the same rules and principles that the proponent himself had used. It is reductio ad absurdum to the core.11 Let us examine how Nāgārjuna uses this method to accomplish his goals.12 Nāgārjuna begins by noting that there are two possible predications about an object A: “A is” and “A is not.” The conjunction and the negation of the conjunction give rise to yet two more possibilities: “A both is and is not” and “A neither is nor is not.” This is the catu ṣkoti or quadrilemma, also known as four-cornered negation. Nāgārjuna analyzes these four alternatives and, by drawing out the implications of each, demonstrates that it is impossible to erect any sound rational metaphysics. For example, with respect to causation, these four possibilities translate into: (1) A thing arises out of itself, (2) a thing arises out of not-itself, (3) a thing arises out of both itself and not-itself, and (4) a thing arises neither out of itself nor out of not-itself.13 Nāgārjuna argues that on the frst alternative (the Sāṃ khya view) cause and effect become identical; their identity points to their non-difference. Thus, any talk about their being causally related is superfuous. On the second alternative (the Nyāya view), cause and effect become entirely different, and, accordingly, there can be no common ground between the two to make the relation of causality possible. Thus, the second alternative is equally meaningless. He further argues that since the frst and the second possibilities are meaningless, the two remaining possibilities that arise out of the conjunction and the negation of the conjunction are equally meaningless. The point that Nāgārjuna was trying to make is as follows: Things arise neither at random, nor from a unique cause, nor from a variety of causes. An entity is neither identical with its causes nor different from them, nor both identical and different from them. Nāgārjuna further argues that both the opposing views outlined above—that the effect is contained in the cause prior to its creation and so is not a new creation, and that the effect is totally different from its cause and so is a new creation—presuppose the svabh āva of events identifed as cause or effect. However, if an event has a nature of its own, then it will always have that nature; it will never change. When events have 251 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T a nature of their own or are ascribed eternal essences, they are either totally identical or totally different. Qualifcations of the sort “some” or “partially” (i.e., saying that events are partially identical or partially different) are not permissible, as svabhava would (by defnition) be free from conditions; thus, it cannot be said to be caused in as much as being caused implies conditions, and, therefore, it cannot be brought into existence. In short, we have two aspects of a causal relation that are not compatible with each other. One of these aspects is that causation involves Dependent Origination; the other is that each cause and effect has an eternal essence of its own which is not capable of origination. If we choose the latter, there is no Dependent Origination; if we choose the former, neither the cause nor the effect could have an eternal essence. If neither of the two has an eternal essence or self-nature, then everything becomes conditional. Nāgārjuna argues that, when causes and effects are taken to be absolutes, they lead to absurdities; they are not self-existent entities that exist independently and unconditionally. Causal relations do not imply temporal sequence but rather mutual dependence in the sense that a cause is not a cause but for the effect, and the latter not an effect but for the cause. Such conditioned entities as causes and effects do not have essential nature of their own; they are śūnya. They are relational concepts. They exist relatively and dependently, and if or when taken to exist independently and unconditionally, these concepts generate absurdities. Śūnyat ā (Emptiness) and the Levels of the Truth Nāgārjuna employs his causal theory ruthlessly, demonstrating that not only concepts and doctrines of rival schools (regarding permanence, a substantial self, etc.) but also central doctrines of Buddhism—momentariness, karma, skandhas, and even the very idea of Tath āgata—contain inherent selfcontradictions. If there is no causality, he argues, then there is no change either, because change requires that one thing become another, which is logically impossible. The concept of time as consisting of the past, present, and future articulates this problem. That which is present cannot become past, and that which is future cannot become present, because in either case a thing would become what it is not, which is unintelligible. Nāgārjuna argues that for a thing to be permanent, it must remain the same amid changes; however, it has been demonstrated that a being cannot change, nor can it cease to be. Consequently, the defnition of permanence is inapplicable to anything whatsoever. In effect, both permanence and change are metaphysical concepts that Nāgārjuna severely criticizes. It is worth noting that though Nāgārjuna’s rejection of change and causal origination seems to bring him near the Advaita position, the Advaitin still maintains that things have an eternal essence, ātman-brahman, while Nāgārjuna’s radical thesis of essence-less or emptiness remains far removed from the Advaitin essentialism.14 Every concept, argues Nāgārjuna, acquires meaning only when contrasted with its complement; in that sense, every concept implies its own negation. 252 THE BUDDHIST SCHOOLS Nāgārjuna rejects the metaphysical categories of substance and attribute, whole and part, knowledge and object, universal and particular, self and not-self, the pram āṇas and the prameyas, bondage and liberation. These metaphysical concepts come in pairs and are mutually dependent; the reality of each is conditioned by the other, so they exist relatively insofar as the members of each pair depend upon the other. If a substance is that which underlies attributes, then the two concepts substance and attribute are dependent upon each other; any defnition of substance in terms of attributes must be circular inasmuch as an attribute is what characterizes a substance. Likewise, if a whole consists of parts, then a part is a part only insofar as it belongs to a whole; both concepts go together. Notice that in critiquing the concepts of whole and part, Nāgārjuna is critiquing the distinction between conditioned and unconditioned dharmas, which was one of the central concerns of the early Buddhists. The same sort of mutual dependence affects the concept of “vijñ āna” (cognition/knowledge) used by both Hindu and Buddhist philosophers. If an object is that which is manifested by a cognition, and a cognition is that which manifests its object, then there cannot be one without the other, and any defnition would be applicable to both together and not to each one separately. In so asserting, Nāgārjuna is effectively critiquing the Buddhist use of the word “vijñ āna” and the fourfold conditions that give rise to it, especially the ālambanapratyayat ā (an object as condition). Following the method outlined above, Nāgārjuna examines various metaphysical theories that existed in Indian thought during that time—such as the Vaiśeṣika theory that a material object consists of simple atoms, the Sāṃ khya theory that material objects arise out of simple undifferentiated stuff called prak ṛti, and the early Buddhist theory that reality is a process or series of instantaneous events—and shows that in each of these cases, the concepts employed (e.g., whole and part, simple and composite, permanence and change, undifferentiated and differentiated) imply their opposites, and to the extent they do, the thesis cannot be coherently formulated. Nāgārjuna argues that since the concept of an object, such as a chair or a frying pan, is empty, then it follows that the cognized object itself (the chair or pan) is also empty, devoid of self-nature. In such a scheme, it does not make sense to argue whether things like chairs or frying pans exist or not. Ascribing existence to things is only a matter of pragmatic usefulness, not of ontological reality. Accordingly, Nāgārjuna concludes that since no entity can be characterized as having its own essence—that is, being simple, permanent, instantaneous, a whole or a part—such entities are śūnya. Divergent theories of reality are, he says, conceptual constructions (vikalpa) grounded in divergent perspectives. It is worth remembering in this context that Nāgārjuna’s argument for the emptiness of concepts and theories about reality does not entail the emptiness of reality itself. Rather, Nāgārjuna’s thought implies that there are two different levels of truth: The conventional truth (samvṛti) and the noumenal or transcendental truth (param ārtha satt ā).15 For example, in view of his radical 253 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T critique, the concept of śūnyat ā itself may be said to undergo two levels of transformation, as applied to the phenomenal and noumenal worlds, and so understood from the conventional point of view as lacking self-nature or any substantial reality of its own, or from the transcendent standpoint as signifying the incoherence of all conceptual systems. In the phenomenal realm, there is no absolute truth; truth is always relative to a conceptual system. The phenomenal world only has a pragmatic or conventional (samvṛtti) reality. Conventional truth, however, is not the only kind of truth; there is also the param ārthasatya, higher or absolute truth. According to Buddhist teachings, conventional truth of the world pertains only to the phenomenal, or pragmatic, or conventional level.16 However, from the viewpoint of absolute truth, the manifold world of names and forms is simply an appearance. Absolute reality transcends the perceptual-conceptual framework of language; it is unconditional and devoid of plurality. It is nirvāṇa. Such a truth is realized by intuitive wisdom (prajñ ā). It is non-dual and contentless. It is beyond language, logic, and sense perception. It is important to remember that knowledge of noumenal entities such as nirvāṇa and Tath āgata is yet a lower level prajñ ā; at a higher level, even such noumenal entities as these must be dissolved into experiences. In other words, ontology is constantly being transcended by a series of negations, which may be represented as follows: 1 2 3 4 Say, P is a conventional truth. Not-P is a higher truth than P (as negation is always higher than an affrmation). The next higher truth is P and not-P. This may again be denied: It is not the case that P and not-P. Thus, every affrmation can be negated, leading to a higher level of affrmation, which again can be negated. In this context, we must remember that, when Nāgārjuna argues that a thing cannot arise from itself, from what is other than it, nor can it arise from both, nor from neither, his thinking is following a certain logical pattern, a method of analysis. In order for philosophical thinking to be radical, it must avoid falling into the trap of ontology. For this purpose, negation is always at our disposal, given that there is a corresponding affrmation. But negation itself must not be taken in the ontological sense similar to Nyāya negation (abh āva), because that negation again can be negated.17 Again, a similarity with Śa ṃ kara may be noticed: Śa ṃ kara also held that negation is higher than affrmation so that statements like “neti, neti,” of the Upaniṣads state the higher truth than the corresponding affrmation, e.g., “sarvam khalu idam brahm ā” (“all this is the brahman”). However, I must add here that Nāgārjuna’s thinking is more radical than that of Śa ṃ kara, because the negation of P itself must be negated. Since, according to Nāgārjuna, dukkha and sa ṃsāra are conventional truths, their cessation becomes noumenal truth. But the noumenal truth must also be 254 THE BUDDHIST SCHOOLS negated such that we are not stuck with ontology. If there is no sa ṃsāra, there is no nirodha; when there is a real pitcher, one can destroy it by a real process and then speak of the absence of a pitcher. The idea that nirvāṇa is a real cessation of sa ṃsāra implies that sa ṃsāra itself is a real entity, but if sa ṃsāra is śūnya, then the nirodha satya (the Third Noble Truth) and the m ārga satya (the truth of the path, i.e., the Fourth Noble Truth) must also be śūnya. Nāgārjuna’s epistemological method leads him to argue that sa ṃsāra (phenomenal conditioned reality) is not different from nirvāṇa; they are the same.18 In other words, nirvāṇa and sa ṃsāra are not two ontologically distinct levels, but one reality viewed from two different perspectives. The distinction between the two, like all else, is relative. The same reality is phenomenal when viewed conditionally; it is nirvāṇa when viewed unconditionally. Accordingly, nirvāṇa is not something that is to be attained, but something to be realized. It is realized through the right comprehension of the sa ṃsāra in which the plurality of names and forms is manifested. Everything is nirvāṇa; it is śūnya. Thus, śūnya is an experience which cannot be linguistically and conceptually communicated, it is quiescent; it is devoid of conceptual construction, and it is non-dual. Nāgārjuna further argues that no element of existence manifests without conditions. Therefore, there is no non-empty element,19 and whatever is conditionally emergent is empty. Thus, there is a three-way relation between conditioned emergence, emptiness, and verbal convention. Nāgārjuna regards this relation as none other than the Middle Way: Conditioned emergence is emptiness; emptiness and the conventional world are not two distinct ontological levels. To say that a thing is conditionally emergent is to say that it is empty. Conversely, to say that it is empty is another way of saying that it emerges conditionally. What language articulates is the so-called conventional world, which is empty. Nāgārjuna did wrestle with the question as to how words like śūnya and nirvāṇa could verbally articulate what is incapable of being expressed. He accepted the paradox involved to be unavoidable. Utilizing the Buddha’s theory of “Dependent Origination” (prat ītyasamutpāda), Nāgārjuna thus demonstrates the futility of metaphysical speculations. His method of dealing with such metaphysics is referred to as the “Middle Way” (madhyama pratipad), by which he avoids the substantialism of the Sarvā stivādins as well as the nominalism of the Sautrāntikas. There have been endless questions and answers about the nature and validity of N ā g ā rjuna’s thinking. In his Vigrahavy āvartan ī (the End of Disputes), his work of seventy verses with auto-commentary in prose, N ā g ā rjuna unequivocally states that he has no thesis ( pratijña) to prove, a point that would become the focus of debate for later M ā dhyamika philosophers. In this work, N ā g ā rjuna responds to a set of specifc objections raised by Buddhist and non-Buddhist opponents against his philosophy. For example, in response to the objection that if all words are empty, then his arguments are also empty, N ā g ā rjuna responds that the doctrine of emptiness neither means non-existence nor a denial of the world; rather, it explains why the world happens at all. 255 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T Opponents argue that Nāgārjuna’s critical dialectic is destructive, that his position is nihilist, and that his entire system is foundationless if emptiness is not real. Nāgārjuna was not a nihilist. The two-level schema which recognizes the importance of conventional knowledge allowed him to defend himself against the charge of nihilism. The highest truth, he holds, is inexpressible, and it is not to be attained through speculative reason (tarka). Rejection of all concepts and views is the competence of reason to grasp reality. The real is “transcendent to thought; it is non-dual (śūnya), free from the duality of ‘is’ and ‘not-is.’”20 In reading Nāgārjuna, it is important to keep in mind that he was neither a thorough-going skeptic nor a nihilist. T. R. V. Murti refers to Mādhyamika dialectic as “spiritual ju-jutsu,” adding that Mādhyamika “does not have a thesis of his own.”21 However, it seems that to interpret Nāgārjuna as aiming only at destruction is to miss the real signifcance of his philosophy. It is indeed true that Nāgārjuna demonstrates that one could expose self-contradictions in an opponent’s metaphysical arguments without making any claims about what in fact exists, if one uses the rules accepted by the opposing party. Contrary to Murti’s contention, this should not be taken to imply that Nāgārjuna did not have a thesis of his own; rather, through his dialectical method, Nāgārjuna rejects the pretensions of reason to know reality. Nāgārjuna uses reason to transcend reason. Just as one uses a nail to remove another nail from one’s foot, and just as one destroys the poison of a disease by using that poison itself in the medicine, so Nāgārjuna uses logic to destroy logic and to be free from its clutches. His mode of argumentation does not demonstrate the total inadequacy of reason, because he himself uses reason to demonstrate self-contradictions involved in the opponent’s arguments. He instead shows that everything is conditional in the phenomenal world, that reality transcends both refutation and non-refutation, both affrmation and negation, and hence it cannot be captured by discursive reasoning. Śūnyat ā is neither a substance nor an entity. It is not real; it is not an ontological support nor a cosmological principle. Emptiness is also empty; if it were real, then things would not be empty. Śūnyat ā (emptiness, voidness) is defnitionally equivalent to Dependent Origination,22 insofar as nothing exists absolutely and independently. All existents are devoid of svabh āva (own-nature), such that everything exists conditionally and relatively. That which comes at the end and marks the penultimate point of wisdom is that śūnyat ā itself is śūnya—emptiness itself is empty. This is to ward off any misconception that the Mādhyamika thesis is nihilism, or a conception of being as nothingness. Nāgārjuna’s position, if he has a position, is very different from this. He warns us against reifying śūnyat ā into an entity. Hence the culmination of wisdom is the knowledge that emptiness itself is empty. Reality can only be captured by rising to a higher level of truth, which is the level of prajñ ā.23 Thus, in making these assertions, Nāgārjuna indeed provides his readers with some theses of his own, in which case we cannot but ask, can he do so consistently? Readers may also ask: Given that the Buddhist tradition considered Nāgārjuna to be 256 THE BUDDHIST SCHOOLS second in rank, next to the Gautama Buddha himself, to what extent he did justice to the teaching of the historical Buddha? I will let my readers decide how best to answer these questions. V The Yogācāra School of Buddhism An important school of Indian Mahāyāna Buddhism established approximately two centuries after Nāgārjuna was Yogācāra (“practice of yoga”). The school is so-called because it recommends the practice of yoga to attain freedom (nirvāṇa) from the phenomenal world. The school is also known as Vijñānavāda, which derives from the school’s explicitly stated position that vijñāna (consciousness) is the only reality. Notwithstanding its name, the primary emphases of this school are philosophical and psychological. The Buddhist tradition venerates Asa ṅga and Vasubandhu, on some accounts said to be brothers, as the co-founders of this school, though many important Yogācāra works, such as the Yogācārabhūmi and Saṁdhinirmocanasūtra, predate them. Tradition maintains that Asaṅga’s teacher, Maitreya, was not a historical person but a boddhisattva. Asaṅga’s important works are Aryade śanāvikhyāpana, an abridged Yogācārabhūmi that deals with the seventeen stages of yoga practice based on Maitreya’s teachings; Abhidharmasamuccaya, a brief explanation of the elements constituting phenomenal existence from the Yogācāra perspective; and Mahāyānasaṁgraha, a comprehensive work on Yogācāra doctrines and practices. According to Parmārtha’s biography of Vasubandhu, Asaṅga was initially an adherent of Hīnayāna Buddhism (the so-called “lesser vehicle,”) but later converted to Mahāyāna (the “greater vehicle”). Thus, it is not surprising that Asaṅga’s works are characterized by a detailed analysis of psychological phenomena that he inherited from the Abhidharma literature of the Hīnayāna schools. It is Vasubandhu, however, who is regarded as the most famous philosopher of this school. In my discussion of Yogācāra, I will primarily draw from his works. Vasubandhu was born in Puruṣapura (today known as Peshawar) in the state of Gāndhāra in northwest India. Takasuku places Vasubandhu’s life between 420 and 500 CE. Paramārtha wrote his biography sometime between 468 and 568 CE. Although Vasubandhu began as a Sarvāstivādin, he converted to Mahāyāna Buddhism under the infuence of Asaṅga. Two important works of Vasubandhu of this phase are Viṁśatikā or the Twenty Verses with his own commentary, and Triṁśikā or the Thirty Verses with commentary by Sthiramati. Majority of the arguments discussed below are drawn from these two works. Gāndhāra in those days was heavily dominated by the Vaibhāṣika Buddhism, so it is not surprising that Vasubandhu’s early writings were infuenced by this school. During these early years, Vasubandhu supported himself by delivering public lectures on Buddhism during the day and putting that day’s lecture in a condensed verse form in the evening. In time, he composed over 600 verses. He collected these verses into the Abhidharmakośa, which became one of the most important books of the Buddhist tradition. He also wrote a commentary on this work.24 257 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T Fundamental Postulates 1 Consciousness is the only reality. 2 Consciousness is the basic presupposition of any experience; whatever we experience or think about occurs within our consciousness. 3 Both subjectivity and objectivity are manifestations of the same consciousness. 4 There is no proof that external objects exist. 5 All constituents of experiences can be arranged and systematized. 6 Karma is collective and consciousness is intersubjective. 7 Consciousness undergoes three stratifcations. 8 Every individual has eight types of consciousness, but enlightenment requires reversal of their basis, and that consciousness is “turned” into unmediated cognition. 9 There are three realms: The imagined, the empirical, and the absolute. 10 The third realm is free from the subject-object distinction; it cannot be conceptually and linguistically articulated. 11 Practice of yoga is necessary to attain freedom (nirvāṇa) from the phenomenal world. 12 Repeated meditative practices remove past residual impressions, and when all deflements and conceptual constructions are purifed, one is enlightened. In Abhidharmakośa, which is the most important work of the early phase of his career, Vasubandhu describes the views of the different schools of early Buddhist philosophy along with his own position. He arranges and systematizes all the dharmas recognized in the early Buddhist philosophy. Vasubandhu denies the existence of the external world—“vijñaptim ātra” (“cognition only”) is the central concept of the Yog ācāra school. The concept has been variously translated as “appearance only,” “representations only,” “impressions only,” “consciousness only,” “mind only,” etc. The last two are the standard translations, implying that it is a sort of idealism. Vasubandhu takes mind (citta) to be connected to the mental qualities (caitta), i.e., perception and what is being perceived. Mind and mental qualities belong together; there is no external object that is outside and independent of the citta and its correlate caitta. Whether this thesis is an idealism in the sense prevalent in Western philosophy is debatable, and I will not enter into that controversy here. However, it is important to note that Vasubandhu is not asserting merely a theoretical thesis, but rather a thesis that would contribute to the attainment of nirvāṇa. Precisely how, we will see soon. 258 THE BUDDHIST SCHOOLS Cognitions, argues Vasubandhu, arise without depending on the supposed object of cognition. In Vi ṁśatik ā (Twenty Verses), he defends Yog ācāra from objections raised by realists who believe in the existence of an external world; in Tri ṁśik ā (Thirty Verses), he develops the vijñaptim ātra thesis further. Vasubandhu opens Vi ṁśatik ā with the following thesis: “Everything is consciousness only (vijñaptim ātra), because there is the appearance of the non-existent objects, just as a person with a cataract sees hairs, moons, which do not really exist.”25 Vasubandhu next anticipates an objection on behalf of a proponent for the existence of the external world: If we assume for the sake of argument that external objects do not exist, how would we account for their spatial and temporal determinations, the indetermination of various perceiving streams of consciousness, and the fruitful activity which results from their knowledge?26 That is, if cognitions arise without there being any external sense objects, how is it that an object is only perceived at a particular place and at a particular time? Why is it that all persons, and not only one person, can perceive an object only in particular circumstances—e.g., why is it the case that my yellow-perception occurs only when I look there and then, but not anywhere at any time? Why are perceptions of objects not restricted to one stream of consciousness (say, mine)? Why can the same perception not occur in another stream of consciousness as well (say, yours)? And how is it that fruitful activity is possible? If such things as food, water, poison, etc., are merely seen in a dream, if they are merely mental constructions devoid of effcacy, then would not it imply that the real food and real water also cannot satisfy hunger and thirst respectively? Since there is a correspondence between one’s experience and the external objects of that experience, argues the opponent, external objects must exist. Vasubandhu disposes off the above objections by using the argument that in dreams, consciousness creates its own content; it does not need an external object, and the spatio-temporal determinations in dreams and waking experiences are alike. Let me elaborate. Cognitions, asserts Vasubandhu, arise without depending on the putative object. In response to the objection that in the absence of external objects we shall not be able to account for spatio-temporal determinations of cognitions—that is, if there were no real objects corresponding to the idea of objects, then surely objects would arise anywhere and at any time, like in a dream—Vasubandhu argues that external objects are perceived in dreams and hallucinations, though none is actually present. Even in dreams, one perceives such things as a tree, a cup of tea, or a family member as existing in a place and at a particular time, but not in all places and always. Moreover, those persons who, because of their bad deeds, go to hell see the same river of pus, etc. Thus, dreams are as determinate as waking experiences. The roaring of a tiger in a dream may cause real fear to disturb one’s sleep; similarly, an erotic dream may result in a man’s discharging his semen. In dreams and in hell, the four factors outlined by the opponent obtain, although there are no external objects. Thus, based on certain experiences resulting in certain 259 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T other experiences, one cannot conclude that objects corresponding to those experiences, in fact, exist.27 Conversely, he argues that perceptions do not justify the existence of external objects. He defnes perception as an awareness that arises from the very object by which that awareness is specifed. It is indeed true that an awareness of X, if veridical, is caused by X; but X, in this context, is not an external object but rather the percept or object-form (ālambana pratyaya) which “foats” in that very awareness. The mind constructs its own objects. Residual impressions of past experiences generate ideas in the mind, and these ideas are called “objects.” How we see, to a large extent, is determined by previous experiences, and our experiences are intersubjective. Anticipating the question as to how an intersubjective world is possible in the absence of external objects, Vasubandhu refers to the illusory experience of hell shared by persons with a common karmic heritage. Vasubandhu concludes the Twenty Verses by noting that my knowledge of my citta and my knowledge of the cittas of others is not like the knowledge of objects, and concedes that the limitless depths of the series of “cognition-only” cannot be comprehended by a person like him, only the Buddha can comprehend the truth fully.28 Another objection is that we know that the Buddha spoke of sense fields, twelve gateways29 of the subjective and the objective components of our experiences. It is asked: Why did the Buddha teach about sense felds and sense objects if there are no such physical things? Vasubandhu replies that both subjectivity and dharma arise from the store-house consciousness. Perception (for example, impression, arising from a seed) gives rise to an apparent object, say, a color.30 Additionally, the Buddha’s discourses about sense felds are not to be taken literally but obliquely, namely, as intended to lead the hearer toward selflessness. Citta is a series of continuous transformations brought about by appropriate causal conditions. The Buddha’s goal was to discipline laypersons and prepare their minds to believe that there is no substantial self. The six consciousnesses (visual, tactile, etc.) are produced instantaneously by appropriate causal conditions. Appearances arise and perish, without there being any material object outside of consciousness. In this series, there is no unity of a pudgala (person), neither the subject of consciousness nor the object; all events are “without a substantial self.”31 To disprove the possibility of external objects, Vasubandhu’s Vim śatik ā also attacks the Indian theories of atomism held by the Vaibhāṣika and the Vaiśeṣika schools. Vasubandhu’s clever and complex mereological arguments are as follows. He starts with the assertion that for anything to serve as a sensory object, it must be either indivisible and without parts, or indivisible and composed of many parts. Neither of these options would work. If it is the former, it cannot be perceived, since atoms are too minute to be perceived. If it is the latter, we can never perceive all the parts and the sides simultaneously.32 It is asked: Is not perception the most basic pram āṇa by which the existence of objects is established? If the object of perception does not exist, how can it serve as a pram āṇa? Does not memory arise from the perceived object? 260 THE BUDDHIST SCHOOLS Vasubandhu argues that direct perception arises as a momentary event, followed by a mental consciousness (by which time the perception has perished), followed by a memory—but at no stage there is an experience of an external object. Memory is the memory of the perception, but not of the supposed object of perception. In this regard, perception is like a dream.33 Our previous experiences, to a large extent, shape how we see things. In response to the question of how an intersubjective world is possible in the absence of external objects, Vasubandhu refers to the illusory experience of hell shared by persons with a common karmic heritage. When two individuals, X and Y, are looking at the same tree from their family room window, their experiences are very similar, if not the same, because they both share the “same” karma that has matured. In fact, there are two tree-contents: The tree that X perceives and the tree that Y perceives; there is no external tree that exists independently of its being perceived. In other words, there is a no one-to-one correspondence between images and the external objects. Consciousness is the basic presupposition of any experience; no experience can occur without consciousness. This gives a brief synopsis of how Vasubandhu explains our everyday experiences, the inter-subjective world, and the distinction between true and false belief. At times, residual forces (vāsan ās) cause internal modifcations in a consciousness, and, as a result, the object-content is manifested. States of consciousness alone are real; objects are wrongly superimposed on consciousness. Thus, the external world is nothing more than the projection of consciousness.34 Such followers of Yog ācāra as Dignāga use the doctrine of momentariness to argue against the existence of external objects. Given that objects are momentary, duration-less, instantaneous events, they cannot be the cause of consciousness, because for them to serve as the cause of our consciousness, there must be a time lapse between the arising of an object and our consciousness of it. Moreover, both the object of consciousness and the consciousness of the object are experienced simultaneously. So, Dignāga concludes that the object of cognition is the object internally cognized by introspection and appearing to us “as though it were external”; and “that there is no difference between the patch of blue and the sensation of blue.”35 The above amounts to arguing that the alleged external objects depend on consciousness both epistemologically and ontologically; nothing is real except consciousness. Given that no experience can occur without consciousness, forms of subjectivity as well as objectivity are manifestations of the same consciousness. The external objects, which are generally taken to possess objective reality, are nothing but states of consciousness. Vasubandhu explains that consciousness consists of a series of momentary events, giving rise to the awareness of various objects of the senses and the mind. In Tri ṁśik ā (the Thirty Verses), Vasubandhu informs his readers that while the uses of the terms dharmas (constituent elements) and ātman (self) are manifold, both terms simply refer to the transformations of consciousness, which 261 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T undergoes three stratifcations.36 The frst stratifcation is the ālaya-vijñ āna (store-consciousness). The term ālaya-vijñ āna etymologically means “receptacle consciousness”; it is the repository of all v āsan ās (traces of past experiences). Good and bad actions generate bījas (seeds), and these bījas are stored in the ālayaconsciousness. This is the realm of potentiality; it is often compared to the ocean whose surface water is disturbed by the winds, giving rise to constantly changing waves. 37 The earliest use of this term is found in the Sa ṁdhinirmocana S ūtra, a Yog ā c ā rin work that predates both Asa ṅ ga and Vasubandhu. The ffth chapter of this work explains ālaya-vijñ āna as the consciousness which possesses “all the seeds”; future experiential forms grow from these seeds. In itself, the ālaya-vijñ āna is not a static entity; it changes instantaneously. The La ṅk āvat āra-Sutra describes it as follows: “As the waves in their variety are constantly stirred in the ocean, so in the ālaya is produced the variety of what is known as the vijñ ānas.”38 Vasubandhu clarifes the concept further. He argues that the ālaya-vijñ āna is the realm of potentiality; it is the root consciousness. Accumulated karmic traces lie dormant in the ālaya-vijñ āna; when a person performs actions, vāsan ās (habitual residual traces) of these actions are left in the form of seeds in the unconscious and the ālaya-vijñ āna stores them. Seeds are habitualities that are sedimented in the life of an ego. It is important to note that the wind of activity, with which the ālaya-vijñ āna is often compared, is not something external to it. The ālaya-vijñ āna carries within it the traces of all past experiences; it includes within its fold not only experiences of clinging and grasping of what is unperceived, but it is also associated with experiential phenomena such as conception, knowledge, feeling, and volition. The ālaya-vijñ āna is the foundation of experience; individual consciousness grows out of it. The seeds of vāsan ās (habitual residual traces) that have attained maturity germinate in it. These seeds, however, continue to create agitation within the ālaya and manifest under suitable conditions. Accordingly, the ālaya-vijñ āna is both that, which is the causally transformed consciousness (hetu-pari ṇāma-vijñ āna) and the effect of such transformed consciousness ( phala pari ṇāma-vijñ āna). The ālaya-vijñ āna, the individual unconscious, continues from birth to birth. It serves as the basis of both the unconscious and the conscious. Once all past seeds stored in it manifest themselves, no ālaya-vijñ āna remains. The ending of an individual ālaya-vijñ āna may mean either the end of one’s present life, or the attainment of enlightenment—contingent upon how the individual ālayavijñ āna has been exhausted. If an individual does not attain nirvāṇa, the traces of the deeds will create a new ālaya-vijñ āna, and keep one involved in phenomenal existence (sa ṃsāra). The second stratifcation of consciousness is the manovijñ āna (thoughtconsciousness). It is the transformation of potentialities into actual thoughts.39 It is characterized by self-regard, attachment to the self, self-love, and the sense of “I am.” As a thinking consciousness, it mistakes the ālaya-vijñ āna to be the self and creates a false sense of “I.” Sthiramati, in his commentary, refers 262 THE BUDDHIST SCHOOLS to this as the “defled consciousness.” It is generally taken to be associated with the four types of deflements: Perception of the self, confusion about the self, self-pride, and self-love. 40 The third stratifcation is the pravṛtti-vijñ āna, comprised of six active, sensebased consciousnesses which are produced through visual, auditory, olfactory, gustatory, tactile, and cognitive mind (internal perceptions of sukha, dukkha, and so on). The pravṛtti-vijñ āna manifests in the content of various mental states and alleged external objects.41 Manas • • • • Manas is usually translated as “mind.” In the early Buddhist tradition, manas was included among twelve sense felds (āyatanas) comprised of six base-object pairs; on this account, the mind-organ is one of the six bases, corresponding to its object, thought. Like any other sense organ, mind can be restrained, developed, and trained. The Buddha often talks with his disciples about the value of controlling the six faculties. It played an important role in the Abhidharma analysis of early Buddhist psychologists and philosophers. In Mahāyāna, and especially in the Yog ācāra school, manas wore an additional hat as one of the eight consciousnesses that received and disposed of data from the prior six consciousnesses. It became the pivot around which their conception of the ego or I-consciousness revolved. Manas was taken to be an evolute of the eighth consciousness, which is known as the ālaya-vijñ āna. In this account, the seventh consciousness represents the surface of the mind, and the ālaya-vijñ āna serves as the basis of all other mind activity. In this context, it is important to remember that Vijñānavādins are using manas in two different senses. The mano-vijñ āna of the second stratifcation is quite different from the manas-consciousness of the third stratifcation. The mano-vijñ āna owes its origin to the ālaya-vijñ āna, which constitutes its object as well as the basis of its operation and function; it organizes the data presented to it by the six sense-consciousnesses and mistakenly takes ālaya-vijñ āna to be an object, and mis-construes it as an independent self. Manas-consciousness, in the third stratifcation, is used as an inner sense organ, the sense in which it is usually taken by Advaita, Nyāya, etc. Manas receives and disposes of the data received from the other consciousness. Thus, “whereas mano-vijñ āna divides the world into a web of objects, manas polarizes this world around a false-discriminated ego or self. Manas develops attachments and aversions to the ‘things’ which the mano-vijñ āna isolates.”42 263 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T The three transformations, in reverse order, are sensory representation, self-awareness (as well as self-attachment and self-feeling), and the storehouse consciousness where the experiences at the other two levels deposit their traces as the seeds which need to be actualized under appropriate conditions. Whereas the ālaya-vijñ āna is latent, the mano-vijñ āna and the six sense-based consciousnesses are manifest. Between the ālaya-vijñ āna and the seven manifest consciousnesses, there exists a reciprocal dependence. The process of evolution takes place as follows: Seeds are deposited in the ālaya-vijñ āna and ripen there, resulting in the evolution frst of the mano-vijñ āna and then the six-fold pravṛtti-vijñ āna, leading thereby to good, bad, or indifferent behavior. As a result, the vāsan ās are accumulated and stored in the ālaya-vijñ āna and serve as the basis for the continuous, cyclic evolution of the mano-vijñ āna and the six-fold pravṛtti-vijñ āna. The ālaya-vijñ āna changes from moment to moment; vijñ āna of one moment is replaced by the vijñ āna of the next moment, resulting in the formation of a stream of successive moments of consciousness. The self or ego is a complex form of this stream of consciousness, and alleged external objects are simply images that appear in the stream. The transformation of consciousness is without any beginning and it continues to fow until the stored seeds are rooted out and one attains enlightenment. Besides these transformations of vijñ āna, there is nothing else. Everything else is imagined (vikalpa); it has no reality. Hence, the thesis of vijñapti-only. Citta is one, undifferentiated being, but conceptually divided into the subject and the object. In reality, there is neither. The object of vikalpa is asat; vikalpa arises without a real object. These stratifcations of consciousness create the mistaken belief that there are real objects such as trees and frying pans that exist independently of consciousness. Vasubandhu outlines how each of these stratifcations can be overcome and how perfect wisdom can be attained. The state of perfect wisdom is pure—it has no object, no passions; it is a state of peace and joy. It is important to remember that Vasubandhu distinguishes among three natures or realms.43 The frst is that which is imagined (parikalpita) but appears to be real; it only has subjective being (prajñaptisat). The second is the empirical realm (paratantra) or the realm of causality (prat ītyasamutpāda), which accounts for our mistaking impermanence for permanence; the dependent has both subjective and objective beings. The third is the absolute or perfect realm (parini ṣpanna), which is the ultimate truth of all events and the true nature of things (dharmat ā); it is free from the subject-object distinction. This absolute realm is tath āt ā (suchness or thatness), that is, a nature which cannot be conceptually or linguistically articulated, which is not a universal shared by many particulars, and which is uniquely each event’s own nature. It is nirvāṇa. Repeated meditative practices remove past residual impressions, and when all deflements and conceptual constructions are purifed, one is enlightened. The tath āt ā alone is pure vastu sat (real existence). 264 THE BUDDHIST SCHOOLS All three are simultaneously ni ḥsvabh āva (without own-nature).44 The frst is lak ṣa ṇa-ni ḥsvabh āvat ā, or empty by defnition. The second is utpattini ḥsvabh āvat ā, or empty in the sense of Dependent Origination. The third alone is really empty, param ārtaha-ni ḥsvabh āva. Vasubandhu concludes by noting that when consciousness does not apprehend any object, it is situated in consciousness-only.45 This is trans-worldly consciousness. What happens is “resolution at its basis” (āśraya-parāv ṛtti); it is called the dharmak āya of the Buddha.46 VI Concluding Remarks The basic thesis of Yog ācāra is that consciousness alone is. It is sāk āra, that is, it has a form of its own (and there is no formless consciousness); the form of consciousness really passes as its object or ālambana. Consciousness of yellow and consciousness of blue differ, not merely in the objects, which are yellow and blue respectively, but in the consciousnesses themselves—they really are different: One is the consciousness of blue, the other is the consciousness of yellow. To the ordinary mind, the ālambana, the object, seems to be out there in the world. They argue that the so-called ālambana that appears in a consciousness is nothing, but the form of the consciousness and it is given along with the self-manifestation (svasa ṃvedana) of that consciousness. This is the basic thesis, but this thesis has given rise to both internal and external problems. Internal problems concern the relation of this thesis to the Buddha’s own teaching, and to the nature of the Buddha-consciousness—the consciousness of the enlightened one, irrespective of whether one is talking about the arhat or the boddhisattva. The external problems concern the relation of this thesis to the ordinary point of view, which is committed to subject-object dualism. Ordinarily, the objects that we perceive have determinate places in space, and we consider our particular perceptions to be caused by those supposed external objects. But if there is no external object, why is it that our perception in an instance is of this place and not of another place? Vasubandhu replies to such objections by citing the case of dreams, in which we also perceive things at determinate places there and not here. If the objects of dream consciousness could have such determancies, so also could the seeming objects of our perceptions—even if there is no real object outside. This is a diffcult argument and requires a careful development, considering the question whether the analogy drawn between waking and dreaming holds good. It would be instructive to consider in this context Descartes’ so-called dream argument. Whereas Descartes asks how we can distinguish waking from dreaming, Vasubandhu says that the waking experience and the dream experience are so alike that representations in both have determinate positions without there being an external object. Dream representations arise without there being an external object; similarly, ordinary waking perceptions could be law-governed without the causal infuence of supposed external 265 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T objects. In both cases, we have intentionalities—or consciousness as being of something—which cannot be reduced to causality. One way of preserving the intentional relation without bringing in causality is to appeal to a coherence among different minds, or to the intentionalities belonging to the same mind. Another example Vasubandhu gives in his defense seems to appeal to such a coherence: How is it, he asks, that the evil spirits who suffer in the boiling caldrons of hell have those representations even though there is no such hell? In this case, he seems to argue that it is because of their common, shared representations that the appearance of something being there arises. But be that as it may, Vasubandhu holds that the representations are of something or the other, and this something or the other really belongs to the structure of those representations, so that only the representations exist. The data of our experiences do not require us to posit anything other than our representations. Vasubandhu also discusses our perceptions of other minds. In his thinking, other minds have a different metaphysical status from material objects. The material objects that appear, as we saw, are forms of consciousness, but other minds are independent realities. He therefore concedes that when I experience other minds—for example, if I perceive that another person is in pain—I am not simply experiencing an intentional object, but also having an experience that transcends it. Nevertheless, my experience of other minds is intentional and has a content that the other person is in pain, even though I do not experience that pain directly. In contrast, when the Buddha knows other minds, he directly experiences what they experience, including their pain. The contrast between the experience of a person, which is intentional, and the experience of the Buddha, which is non-intentional, causes Vasubandhu’s exposition of many problems. Perhaps the distinction between the representational consciousness of persons and the direct pure consciousness of the enlightened one may provide further insights. Nirvāṇa brings about a complete reversal of consciousness, in which the ālaya-vijñ āna is dissolved, so that the intentional consciousness—whose object-directedness was being determined by the ālaya—sheds its intentionality and becomes pure non-intentional knowledge. This is the knowledge of the Buddha; it is both vijñapti and not-vijñapti, both mind and not-mind. Whether Vijñānavāda can be called an idealism in the Western sense is diffcult to decide, because for that purpose we need to determine what is meant by “idealism.” There is no need to determine that here, but it is rather important to clearly understand the concept of “vijñ āna” and the associated vocabulary Vasubandhu uses in the context of Indian philosophical rhetoric. For a long time, the Vaibhāṣika discussions continued to determine the status of vastu sat and prajñapti sat. For Vaibhāṣikas everything is vastu sat, consisting of real dharmas; even nirvāṇa is conceived as a vastu, a positive entity. The Sautrāntikas deny to nirvāṇa this status, asserting that only the present dharma is vastu sat; the others are absences. For the Mādhyamika, everything is śūnya (empty); there is no vastu sat. For the Vijñānavāda, the positive entities that we 266 THE BUDDHIST SCHOOLS perceive as things of the world are only prajñaptisat or jñ āna of the enlightened one, that is, nirvāṇa is vastu sat. The truth of vijñapti or intentional consciousness is śūnyat ā, but the nature of intentional consciousness as śūnyat ā is realized only in enlightenment; it is also called tath āt ā or suchness,47 which is seen as the truth of everything, including intentional consciousness. This explains why the Buddha-consciousness, although non-representational and hence non-mental, is yet also mental, because it knows the truth of mental consciousness. This explains why the Buddha-consciousness is treated within the Yog ācāra school, as we fnd in Asa ṅga, as being embodied, although one has to distinguish between the three bodies of the Buddha: Dharma k āya (the body of truth), sambhoga k āya (the body of communication), and nirm āṇa k āya (physical body).48 The body, though a hindrance to the functioning of consciousness in the case of ordinary persons, still functions through its medium such that the visual consciousness functions through the eyes, the tactual consciousness through the skin, and so on. The Buddha could not possibly have taught without having a body, so he freely assumes a body which, in his case, is not a negation nor a limitation on his consciousness, but a freely used medium for showing his infnite compassion for others. Note that with the idea of the tath āt ā or suchness which is the essence of all beings, Asa ṅ ga and indeed all Yog ā c ā ras come to a position which is very near the Ved ā ntic doctrine, i.e., ātman is the essence of all things. Study Questions 1. Explain the key philosophical conceptions of the Vaibhāṣika school. What are some of the differences between the Vaibhāṣikas and the Sautrāntikas? 2. The theory of momentariness (k ṣanikavāda) plays a central role in the Buddhist schools. The four schools of Buddhism you have studied in this chapter subscribe to the doctrine of momentariness. Discuss each account and the differences among them. Is there any way to reconcile the differences? Which account seems more defensible to you, and why? 3. Explain Nāgārjuna’s notions of śūnyat ā (emptiness) and niḥsvabh āvat ā (lack of inherent essence or absence of the essence of things). What are their strengths and weaknesses? 4. Vasubandhu denies the existence of the external world and argues for “vijñaptim ātra” (“cognition only”). Critically evaluate Vasubandhu’s arguments against the existence of external objects. 5. Opponents argue, “Nāgārjuna’s critical dialectic is destructive, that his position is nihilist, and that his entire system is foundationless if emptiness if not real.” Do you agree with this assessment? Argue for or against. Give reasons for your position. 6. Do you think that the ideal of arhat diminishes the value and importance of nirvāṇa as a goal of Buddhism? Defend or criticize the claim. 267 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T Suggested Readings J. Takakusu, The Essentials of Buddhist Philosophy (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1978) and Yamakami Sogen, Systems of Buddhistic Thought (Varanasi: Bhartiya Publishing house, 1979) contain helpful discussions of the four schools of Buddhism. David J. Kalupahana, A History of Buddhist Philosophy: Continuities and Discontinuities (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1994) contains concise chapters on Abhidhamma and Nāgārjuna. Mark Siderits, Buddhism as Philosophy: An Introduction (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett, 2007) provides a thought-provoking discussion of Yog ācāra and Madhyamaka. For translations of Vasubandhu’s works, see S. Anacker, Seven Works of Vasubandhu (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1984); Thomas Kochumuttom, A Buddhist Doctrine of Experience: A New Translation and Interpretation of the Works of Vasubandhu the Yogācārin (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1982); and Thomas E. Wood, Mind Only: A Philosophical and Doctrinal Analysis of the Vijñanavāda (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1994). For translations of MMK, see Kenneth Inada, Mūlamadhyamakak ārik ā, Bibliotheca Indo-Buddhica Series, No. 127 (Delhi: Sri Satguru Publication, 1993); David J. Kalupahana, Mūlamadhyamakak ārik ā of Nāgārjuna (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1991). 268 14 THE VEDĀ N TA DAR Ś A NA I Introduction Of all the systems of Indian philosophy, Vedānta has been the most infuential. This system differentiated itself into many sub-schools, each having a well-argued philosophical position and a strong religious following. The term “Vedānta” (i.e., “Veda” + “anta”) literally means “the end of the Vedas.” “Veda,” derived from the root “vid,” means “knowledge”; “anta” has two meanings: The fnal place reached as a result of the effort, and the goal toward which all effort is to be directed, i.e., the Upaniṣads, which themselves are often referred to as “Vedānta.” Accordingly, “Vedānta” refers to the doctrines set forth in the part of the Vedic corpus known as the Upaniṣads, one of the three bases of the Vedānta school. The Upaniṣads, you might recall, are replete with ambiguities, inconsistencies, and contradictions; they do not contain a systematic and logical development of ideas. Several commentators made attempts to systematize the teachings of the Upaniṣads; Bādarāya ṇa in his Ved āntas ūtras (aphorisms of Vedānta) or Brahmas ūtras (aphorisms about brahman) made one such attempt. These aphorisms constitute the second basis of the Vedānta schools. The Bhagavad-G īt ā, a chapter of the great epic Mah ābh ārata, probably added much later, constitutes the third basis. The Vedānta school received its formal expression in the Ved āntas ūtras. The term “s ūtra” literally means “thread,” and is related to the verb “to sew.” It refers to a short aphoristic sentence, and collectively to a text consisting of such statements. It is diffcult to date the Ved āntas ūtras. However, given that these s ūtras contain a refutation of most of the schools of Indian philosophy, which date from 500 to 200 BCE, the Ved āntas ūtras could not have been composed earlier than 200 BCE. S ūtras usually do not consist of more than two or three words. Brevity and terseness characterize these sutras. The laconic contents of these s ūtras have given rise to divergent interpretations within different schools of Vedānta. The interpretations differ regarding the nature of the brahman, relation between the brahman and the world, the self, and mok ṣa. One’s interpretation of the Vedānta doctrines may be substantiated as much by independent 269 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T reasoning as by citing and interpreting sentences from its three bases. One is a founder of a new sub-school if one has substantiated the interpretations of the doctrines by suitably commenting upon these foundational texts, in the technical jargon, by writing bh āṣyas (commentaries) on them. The two better known schools of Vedānta are Advaita Vedānta (nondualism) of Śaṃ kara and Rāmānuja’s Viśiṣtādvaita (qualifed non-dualism). Besides these two, there are several sub-schools, e.g., those of Madhva, Bhāskara, Vallabha, and Nimbārka. Each of these commentators earned the honorifc title of “Ācārya” (though today, it has lost its past signifcance). These schools may be grouped under two basic headings: Non-dualistic and theistic. In this chapter I will discuss two schools of Vedānta: Śaṃ kara’s non-dualistic (Advaita) Vedānta and Rāmānuja’s theism or qualifed non-dualism (Viśiṣṭādvaita). II Advaita Vedānta Advaita Ved ā nta, the non-dualistic school of Ved ā nta, has been and continues to be the most widely known system of Indian philosophy in the East and the West alike. Śa ṃ kara was the founder (primary explicator) of this school. He was born in K ā ladi, a village in the southern Indian state of Kerala, India, in 788 CE, into a Brahmin family known for its learning. His parents named him “Śa ṃ kara” meaning the “giver of prosperity.” We do not know much about his father; he died very young. His mother played an important role in shaping his life. Śa ṃ kara left home at an early age in the search of truth and a guru (teacher). When he reached a Śaivite sanctuary along Narmada river in north-central India, guru Govinda accepted him as his pupil. He studied the Vedas, the Upani ṣads, and the Brahmas ūtras with him. There is no record of how long he stayed with Govinda; however, there is no doubt that Śa ṃ kara received most of his training under the guidance of Govinda and attained the highest knowledge at a very early age. He traveled across India debating with opponents and reforming aberrant practices. His biographies vary signifcantly in terms of the journeys he took, pilgrimages, and monastic orders he established all over India. He died at the early age of thirty-two. Śa ṃ kara was not only a philosopher but also a mystic, a saint, and a poet. An enormous amount of work has been attributed to him. His achievements are remarkable, and the short span of his life makes his contributions more remarkable. Some of his important works are Bhagavadag īt ābh āṣya (BGBh), Brahmas ūtrabh āṣya (BSBh), Upade śasāhasr ī (Upade śa), B ṛhad āra ṇyakopanisadbh āṣya (BUBh), and Chandog yopani ṣadbh āṣya (CUBh). In the Advaita tradition, immediately following Śa ṃ kara, three lines of interpretation developed: 1 The frst school originated with Sureśvara (800 CE) and his pupil Sarvajñātma Muni (900 CE). Sureśvara was one of the direct disciples 270 T H E V E DĀ N TA D A R ŚA NA of Śa ṃ kara. His important works are Nai ṣkarmyasiddhi (NS), Tattir īyopanisadbh āṣyavārtika (TUBV), and B ṛhad āra ṇyakopani ṣadbh āṣyavārtika (BUBV). Sarvajñātma Muni was the author of Sa ṃk ṣepa śār īraka (SS). The second school originated in the writings of Padmapāda (820 CE), Śa ṃ kara’s closest disciple. He wrote Pañcapādik ā (PP), an exposition of Śa ṃ kara’s commentary on the frst four aphorisms of Brahmas ūtras (BS). Prak āśātman (1000 or 1100 CE?) wrote a commentary on PP entitled Pañcapādik āvivara ṇa (PPV). It is the basis of the Vivara ṇa school, and the school is named after it. The third school is associated with Vācaspatimiśra (840 CE). He developed in considerable detail and subtlety the views of Ma ṇḍ ana Miśra, a contemporary of Śa ṃ kara, and his interpretation came to be known as the Bhāmat ī tradition. Vācaspati’s commentary on Śa ṃ kara’s Brahmas ūtras, from which this school receives its name, is known as Bh āmat ī (the lustrous). In this chapter, I will primarily draw from Śa ṃ kara’s BSBh, and my analysis will be from the Vivara ṇa perspective. 2 3 Śa ṃ kara, according to a well-known legend, was asked to summarize his po- sition in one verse. He summarized it in one-half of a verse, which runs as follows: (1) The brahman is the truth, (2) the world is false, and (3) the fnite individual is none other than the brahman (“brahma satya ṃ, jagan mithyā, jīvo brahmaiva n āparaḥ”).1 His major works reiterate this philosophy in different ways. To have a clear understanding of Śa ṃ kara’s philosophy, it is essential that we understand the meaning and ramifcations of these three assertions. I will begin with the frst. Fundamental Postulates 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 The brahman, the only reality, is non-dual (advaita). The brahman is both the effcient and the material cause of the world. The world, a creation of (m āyā), is false; it is empirically real. The self and the brahman are non-different. There are six sources of true cognition (pram āṇas): Pratyak ṣa (perception), anum āna (inference), śabda (testimony), upam āna (comparison), arth āpatti (postulation or presumption), and anupalabdhi (non-cognition). Realization of the brahman (mok ṣa) is the goal of human life. To realize the brahman or mok ṣa, one must follow the path of knowledge ( jñ āna-yoga). Mok ṣa is the realization of one’s true nature. 271 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T Metaphysics The Brahman is the Truth The brahman, argues Śa ṃ kara, is the highest transcendental truth. It alone is. It is that state of being where all subject/object distinction is obliterated. It is pure consciousness that is timeless, unconditioned, undifferentiated, without beginning, and without end. The brahman is the most important metaphysical concept of Advaita Vedānta. Initially the word “brahman” meant “prayer” or “speech,” and eventually it came to signify two allied meanings: “the greatest” and “the root of all things.” Etymologically, “brahman” has two constituents: The verbal root √bṛh, meaning “to grow,” “the great,” “to burst forth,” and the suffx “matup,” signifying everything grows from the brahman. The brahman has been described positively as well as negatively in the Upaniṣads.2 Positively, the brahman has been described as “the real, the knowledge, and the infnite,”3 “all this is verily the brahman, let it be worshipped as tajjal ān,” etc.,4 and negatively, it has been described as “not gross, not subtle, not short, not long, not red, not adhesive, without shadow, without darkness, without air, without space, without attachment, without taste, without smell, without eyes….”5 Śa ṃ kara takes the negative statements to be higher than the affrmative ones, because negation becomes signifcant only after an affrmation has been made (which is then negated). It is a lower level of understanding to regard brahman as omnipresent, such that everything whatsoever is brahman. But it is only after one has made such a statement, that one can proceed to negate what has already been affrmed and say, “none of this is the brahman.” “This” refers to any possible object. The brahman transcends the world of objects (material things) and fnite individuals. Manyness, plurality, and differences are all appearances. In fact, the two brahmans are one. The teachings of Advaita affrm one simple truth: There is one reality, although it is known by different names. Nirgu ṇa and sagu ṇa brahman refer to the same reality; they have the same referent, though the senses differ (very much like the Fregean analysis of the “morning star” and “evening star”).6 The brahman is one without any second; it does not admit of any real change nor of any difference. Śa ṃ kara’s non-dualism denies all differences external as well as internal in the brahman. Other schools of Indian philosophy recognize some sort of difference to be real: For example, the Nyāya-Vaiśeṣikas recognize a real difference between consciousness and its object, not to speak of the plurality of conscious selves and of objects; the Buddhists of the Vijñānavāda school take consciousness or cognitions alone to be real, but recognize internal difference among the arisings and the perishings of momentary cognitions; the Sāṃ khya recognizes both prak ṛti and puru ṣa as reals and an external difference among many selves; and R āmānuja’s qualifed non-dualism (as we will see a little later 272 T H E V E DĀ N TA D A R ŚA NA in this chapter) asserts an internal difference between cit and acit, within the unity of one being, i.e., the brahman. Śa ṃ kara’s non-dualism denies all external as well as internal differences in the brahman. Indian philosophers usually recognize three types of distinctions: (1) Sajāt īya (difference between an individual cow and other cows), (2) vijātiīya (difference between a cow and a horse), and svagata (the difference between the parts of a whole (difference between one leg of a chair and other legs)). For Śa ṃ kara, reality being one and differenceless neither admits of negation nor of antecedent negation nor of negation after destruction; thus, it is beginningless, endless, eternal, and without any qualitative determination. Such being the nature of the brahman, the world consisting of different things as well as different types of things (conscious selves and non-conscious nature) is simply an appearance. Sagu ṇa brahman has been variously described, viz., as satya ṃ (truth), jñ ānam (knowledge), as anantam (infnite) and sat (existence), cit (existence), and ānanda (existence), consciousness, and bliss), etc. Sagu ṇa brahman is the brahman about which something can be said; it is the brahman as interpreted and affrmed by the mind from a limited, empirical standpoint. That the brahman is pure consciousness does not imply that consciousness is an essential quality of the brahman, for that would amount to introducing an internal distinction within the brahman, i.e., the distinction between a substance and its qualities. The brahman is not a substance, substance being an objective category. Likewise, when the Upaniṣads say that the brahman is satya ṃ (truth), jñ ānam (knowledge), and anantam (infnite),7 the intention is not to imply that these are the qualities of the brahman, for that would amount to introducing an internal difference in the brahman’s nature. The Advaitins therefore construe such sentences of the Upaniṣads to mean three different ways in which, undifferentiated nature of the one, the brahman is being articulated. These words serve to differentiate the brahman from their opposite qualities. To say that the brahman is the truth, negates that the brahman is untruth, etc. No positive determination of the brahman is possible. This is very similar to Spinoza’s assertion that every determination implies negation: Omnis determinatio est negatio. As the Upaniṣads reiterate, the best way to describe the brahman is by saying that it is “not-this,” “not-this.”8 Via negativa orients the mind of the aspirants toward qualityless (nirgu ṇa) brahman. Nothing can be affrmed about it. Śa ṃ kara himself notes, “the reality is without an internal difference. …it is unthinkable; the thought can be brought to it via negation of what can be thought.”9 Nothing can be affrmed about the nirgu ṇa brahman. What then is the criterion of “reality” that the Advaitin applies to reach this ontological position? Sublation (B ādha) Śa ṃ kara uses “bādha,” which, in the context of his ontology, has been con- strued as “cancellation” or “negation” or “contradiction.” Sublation is a mental process of correcting and rectifying errors of judgment. In this process one 273 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T disvalues—more as a psychological necessity than from a purely logical point of view—a previously held object or content of consciousness on account of its being contradicted by a new experience. However, not all corrections and rectifcations fall under sublation. Suppose in an experiment I start with a hypothesis X believing that it would work in an experiment A. Further investigation reveals that it would not, and I arrive at the conclusion that X will not work for the experiment A. Rectifcation has occurred; this, however, is not sublation. It not only requires the rejection of an object, or a content of consciousness, but also that such rectifcation must occur in light of a new judgment to which belief is attached and which replaces the initial judgment. In other words, for sublation to occur in the above example, hypothesis X, on account of a, b, c, must be replaced by, say, Y, which is more valuable, and to which belief is attached. So, bādha not only requires the rejection of an object or a content of consciousness, but also that such rectifcations occur in light of new judgments to which belief is attached, and which replaces the initial judgment.10 Sublation • • • • • • Sublation is a mental process of correcting and rectifying errors of judgment. It is an axio-noetic process. It involves ordering of experiences. A distinction between subject and object, consciousness and the content of consciousness, experience and experienced is necessary for sublation to occur. Plurality of objects is necessary for sublation. Anything that is in principle sublatable is of lesser value than that with which it is sublated. Sublation presupposes subject-object dichotomy, because it is the subject who sublates the object. It requires rejection, turning away from an object or content of consciousness in favor of something to which more value is attached. In his commentary on Brahmas ūtras,11 Śa ṃ kara uses the criterion of sublation to arrive at three levels of existence: Reality or absolute existence (pāram ārthika satt ā), empirical-practical (vyavah ārika satt ā), and illusory (prātibh āsika satt ā). Reality or absolute existence is that which in principle cannot be sublated or canceled by any experience, because no experience can deny or disvalue it. Reality is non-dual; it is the level of pure being. The act of cancellation presupposes a distinction between the experiencer and the experienced. It involves a plurality of objects because cancellation juxtaposes one object or content of consciousness against another incompatible object or content of consciousness and judges the frst to be of lesser value. Thus, cancellation requires rejection, 274 T H E V E DĀ N TA D A R ŚA NA turning away from an object or content of consciousness in favor of something to which belief, more value, is attached. The brahman has no dichotomy within it; it is pure oneness and cannot be denied by any lower order of being. Therefore, no other object or content of consciousness can replace it. Brahman cancels everything while remaining uncancellable by any experience whatsoever. “Consciousness is not,” argue the Advaitins, is not a possible determination, for such a negation must itself be an act of consciousness, consciousness negating itself, which would be a self-contradiction. Given that consciousness does not admit the possibility of its being negated or canceled, it is the only reality. Thus, the brahman or consciousness belongs to the highest level of being. Empirical-practical consists of those contents of experience that can only be canceled by reality. This is the level of empirical existents. It includes our experiences of the world of names and forms, multiplicity of empirical objects, other fnite individuals; in short, all subject-object distinctions that are governed by the law of causation. Most of us live at this level, die at this level, and are reborn at this level. At this level of experience, we take the world and God to be separately real, and attribute to God all the qualities that are generally associated with “God” in theism. God in this sense is sagu ṇa brahman, the creator, maintainer, and destroyer of the world. He is an object of worship. Illusory existent consists of those contents of experience that can be canceled by reality or by the empirical existents. Illusions, hallucinations, dreams, etc., belong to this level. An illusory existent is different from an empirical existent insofar as it fails to fulfll the criteria of empirical truth. For example, a thirsty traveler passing through a desert runs to a spot to quench his thirst. However, upon reaching that spot he discovers that there is no water and that his perception of water was really a mirage. The illusion of water ends when the traveler, in light of new experience, discovers that it was a mirage. The illusory existent, i.e., the experience of mirage, is canceled by another empirical experience. In short, all objects in principle can be negated. If X is an object, then the determination “X is not” is possible. It cannot therefore be ultimately real. The objects that belong to the empirical level can be canceled; therefore, they are not real, better-yet, false, which leads me to the second assertion mentioned above. The World is False (Mithyā) Let us now discuss what Śa ṃ kara meant by his assertion that the world is “mithyā.” “Jagat” is usually translated as the “world,” the realm of birth and death; it is where suffering is manifested. The standard English translation of the word “mithyā” is “false.” So, it makes sense to say that Śa ṃ kara is asserting the falsity of the world. However, what does Śa ṃ kara mean by “falsity”? What is entailed in his assertion? What is the relationship between the brahman and the false world? Why, or who, creates this false world? A clear understanding of the logical and ontological distinction between the false and the unreal is essential for a proper understanding of the Advaita school. 275 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T Reality, Empirical-Practical, and Unreality Reality • • • • Reality or absolute existence transcends all distinctions, oppositions, qualifcations, relations. It is that which in principle cannot be canceled by any experience. There is nothing higher than the experience of reality. It is the experience that sublates everything else. Empirical-Practical • • • • • • • Contents of empirical-practical level are in principle sublatable. It is the realm of appearance. Distinctions, oppositions, qualifcations, relations, and illusions characterize this level. The world is real from an empirical-practical standpoint; it is not a fgment of one’s imagination. To say that “X is false” does not mean that X has no reality. False is an object of experience; it is empirically real. There is a kind of temporality about it insofar as it is transcended, for example, the rope-snake. False is not unreal; it is grounded in reality. It is sublatable by the experience of reality. Unreality • • • • Unreality is non-being. Unreal does not have any objective counterpart. It neither can nor cannot be sublated. The concept of the “unreal” in Advaita is self-contradictory, for example, the son of a barren woman. Adhyāsa (Superimposition) To understand what is entailed in Śa ṃ kara’s assertion that the world is false, one must frst understand two crucial Advaita concepts, viz., “adhyāsa” (superimposition) and “m āyā” (ignorance). These concepts lie at the basis of Advaita metaphysics and epistemology and would go a long way in helping us to come to grips with the status of the world in Śa ṃ kara’s philosophy. Superimposition refers to a simple, everyday experience in which one thing appears as another. It is an erroneous cognition, an illusory appearance; it is a cognition of “that” 276 T H E V E DĀ N TA D A R ŚA NA in what is “not-that.” In superimposition, one apprehends a thing to be other than what it is. Śa ṃ kara explains it thus: Adhyāsa is one thing appearing as another, or rather “in one thing another appears,” where the latter is “like something seen before” and the appearing is “like memory.”12 Most of us would agree that in everyday experiences we frequently perceive one thing as another or wrongly ascribe the properties of one thing to another. These are the cases of erroneous perception, and the mechanism that underlies it is called “adhyāsa” or “superimposition,” which in Advaita metaphysics includes not only an experience of perceptual illusion but also what occurs in the metaphysical situation when the brahman appears as the world, ātman as fnite individuals, etc. In a superimposition, something functions as the locus, the underlying substratum, and another entity is projected on it. The projected entity is false, and the substratum alone is real. Upon correction of the error, the projected entity is canceled, and the substratum is revealed as real. Adhyāsa (Superimposition) Superimposition is an erroneous cognition; it is wrong identifcation. It is: • • • the mixing of the real and the false; seeing a thing in a locus where it does not exist; and perceiving the attributes of one thing in another locus, etc. Let me provide two illustrative examples: (1) The perception of a rope as a snake, and (2) the perception of a crystal vase as red on account of the red fower placed near it. In the frst case, one apprehends a thing to be other than what it is; in the second, one falsely attributes the qualities of one thing on another. The two examples given above concern things existent in the world. Advaita Vedānta however affrms a more fundamental superimposition, i.e., the superimposition of the world upon the brahman, which creates the sense that the world is real. Just as in a rope-snake superimposition, a rope is experienced as a snake; similarly, under the superimposition of names and forms, the brahman, the only reality, is experienced as the world. Thus, the Advaitins talk of superimposition not only regarding specifc experiences within the world of appearance but also about the ontologically false status of the world in general. Such superimpositions as a rope appearing as a snake begin and end in time; these experiences are private because when I am misperceiving a rope as a snake, you are not. But the superimposition of the world on the brahman does not have any beginning; they are public insofar as most of us make the mistake of taking the world to be real, which it is not. Thus, when Śa ṃ kara 277 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T asserts the falsity of the world, he is not asserting that the world is illusory like snake-rope. The world is empirically real prior to the brahman-knowledge. With the dawn of the brahman-knowledge, the world betrays its falsity. The brahman is self-illuminating; it alone always is. The Advaitins argue that our everyday experiences of superimposition assume various forms. Some superimpositions are that of identity (t ād ātmya)13 as articulated in judgments like “I am this” (uttered pointing to my body), “I am a human.” Here the superimposition is of the body on the self. Again, there are superimpositions of properties and substantives. There is the superimposition of the properties of the body on the self, e.g., “I am fat,” “I am thin”; of such mental states as desires, doubt, pleasure, pain, e.g., “I am happy,” “I am virtuous”; and of the properties of the sense organs on the self, e.g., “I am blind,” “I am deaf.” When a shell (on the beach) appears as silver, or a rope as a snake, one substantive is superimposed upon another. The thrust of Śa ṃ kara’s arguments is as follows: Superimposition assumes the form not only of the “I” but also of the “mine.” The former is the superimposition of the substance (dharmī ), the latter of the attribute (dharma). The reciprocal superimposition of the self and the not-self, and of the properties of the one on the other, results in the bondage of the empirical self. In other words, all appearances—the world appearance as well as the appearance of individuals—are due to superimposition (of one thing upon another). The above discussion makes it obvious that superimposition plays a crucial role in Śa ṃ kara’s philosophy; thus, it is not surprising that Śa ṃ kara begins his commentary on the Brahmas ūtras with superimposition. Before concluding this section, I would like to underscore two points: (1) Irrespective of the sense of adhyāsa under consideration, it is important to remember that superimposition is not possible without a substratum. Padmapāda brings out this point clearly, when he defnes adhyāsa as “the manifestation of the nature of something in another (thing) which is not of that nature,”14 and argues that “superimposition without a substratum cannot even be conceived, let alone experienced.”15 (2) When other schools of Indian philosophy speak of the false identifcation, they talk of the false identifcation between the two reals, the Advaita account of the false identifcation involves mutual identifcation of the real and the nonreal, of the self and the not-self and their attributes. As a result, the self becomes entangled in the world of becoming (sa ṃsāra). At this point, one may ask: Why do we superimpose? Śa ṃ kara argues that superimposition is due to ignorance (m āyā or avidyā); each superimposition is the result of the previous superimposition and gives rise to the succeeding one; in other words, superimposition is beginningless; it is the same as avidyā or ignorance, which I will discuss next. Māyā or Avidyā Śa ṃ kara uses this concept to establish his central thesis that the brahman is the only reality, and the multiplicity of names and forms (n āma-r ūpa) is only an 278 T H E V E DĀ N TA D A R ŚA NA appearance. Etymologically, the term “m āyā” is derived from the root √m ā, meaning “measuring.” With the concept of “m āyā,” Śa ṃ kara measures out the world, so to speak; or the world is what is measurable. The term “m āyā” occurs in the Ṛg Veda, where it has been used as the creative power of the deities. With this power, various deities, for example, Indra and Agni, like a magician, assume many forms.16 The concept of “m āyā” does not occur in the Upaniṣads in a fully developed form, though the idea was not entirely foreign to the seers of the Upaniṣads. Yajñavalkya, for example, states that there is duality “as it were,”17 meaning that the multiplicity of names and forms is not real; it is a creation of m āyā. In the later Upaniṣads, e.g., Śvet ā, m āyā is used in the sense of illusion, and the Lord is said to be m āyin.18 The Advaitins use it to explain the appearance of the world. Māyā is usually translated as “illusion.” This translation, however, does not capture the full import of the concept. Rather than trying to give one-word translation, I will clarify it by setting forth its ontological, epistemological, and psychological meanings. Ontologically, m āyā is the creative power of the brahman which creates the variety and multiplicity of the phenomenal world and makes us believe that it is real. Epistemologically, m āyā is our ignorance (avidyā) as to the difference between reality and appearance. Māyā disappears at the dawn of the brahman-knowledge. Ignorance obscures pure consciousness and makes all empirical distinctions appear. Thus, epistemologically, the distinctions between the subject who knows, the object known, and the resulting knowledge are due to ignorance. From a psychological point of view, m āyā is our tendency to regard the appearance as real, and vice versa. The empirical world is not real; however, our inclination is to believe that it is real. Another term used for ignorance is avidyā, which Śa ṃ kara uses more frequently than “m āyā.” For him avidyā is the same as adhyāsa; it is a kind of psychic deflement, a “natural” propensity to err,19 the seed of the whole world,20 and it generates attachments from a psychological perspective.21 Māyā occurs less frequently than either avidyā or n āma-r ūpa; it is used in the sense of falsity, deception, and magical power.22 Avidyā has generally been given precedence over m āyā in the matters of bondage and freedom; avidyā is the cause of a person’s bondage. In his writings, Śa ṃ kara does not make a distinction between m āyā and avidyā; he uses them interchangeably. For Śa ṃ kara m āyā is avidyā. In one of the passages, in response to the p ūrvapak ṣin’s objection that there is a confict between the Advaita thesis that God is the creator, sustainer, etc., of the world, and the thesis that the brahman is the only reality, Śa ṃ kara argues that the qualities of omniscience, etc., are attributed to the brahman to make the world appearance possible.23 Māyā and avidyā are not different; however, from the lower perspective, m āyā is a fgment of imagination (avidyākalpita). Thus, both m āyā and Īśvara are avidyākalpita. There are many ways of distinguishing the two; we, however, would settle for the simplest: Māyā is cosmic, root ignorance of the “world-experience,” 279 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T while avidyā is individual ignorance. Upon attaining the brahman-knowledge, avidyā disappears; however, m āyā still continues, because it creates the appearance of the world. The point to remember is as follows: Ignorance not only conceals (āvara ṇa) the real nature of the brahman but makes it appear as something else. In other words, fnite individual selves on account of ignorance not only do not see the brahman as the brahman but also see it as something else, i.e., as the phenomenal world (vik ṣepa). For the Advaitins, ignorance is not a mere absence of knowledge, but is rather a positive entity (bh āvapad ārtha), although the negative prefx of the term “avidyā” (“a” = “not” + vidyā = “knowledge”) creates the misleading impression that it is a negative entity, a mere absence of knowledge. The Advaitins advance the following argument for the positivity of ignorance: I have a direct awareness of my ignorance. Such sentences as “I am ignorant of X” provide a testimony about its positive nature. How is such a direct awareness of my ignorance of something possible? If the “ignorance of X” were the same as “the absence of the knowledge of X,” then the latter absence could be perceived (within me) if and only if I knew the counter-positive of this absence, which is the “knowledge of X.” In other words, for me to perceive the absence of an elephant in my living room, I must have the knowledge of an elephant. But if I have the knowledge (of X or the elephant), then I would not be ignorant (of X or the elephant), and I would not have the knowledge that “I am ignorant of X.” This diffculty, argue the Advaitins, can only be avoided if ignorance is a positive entity, and this positive entity conceals X.24 The Advaitins further hold that ignorance is not only a positive entity; it is also beginningless because when one says, “I am ignorant,” it does not make sense to ask them when they began to be ignorant. Though beginningless, ignorance does have an end. Irrespective of whether ignorance is taken to be positive wrong knowledge or lack of knowledge or doubt, it is destroyed by right knowledge.25 These three are similar insofar as they conceal the real nature of the brahman and are dispelled by the knowledge of the brahman. One reality appears as many because of ignorance. To substantiate his basic thesis of non-dualism, Śa ṃkara uses the contrast between the empirical and the real to demonstrate the apparent character of the world, as well as to make the Upaniṣadic use of the “sagu ṇa brahman/God” intelligible. Thus, when the Advaita commentators emphasize that the false is indescribable, they mean that it is neither real (sat) nor unreal (asat). False is that which is experienced but subsequently canceled. Given that it is experienced as being there, it cannot be unreal, because what is unreal (e.g., hare’s horn, square circle) is non-being. Unreal objects do not exist. They do not have any objective counterpart, so they can never become an object of experience. A false entity has an objective counterpart, so it is experienced, though sublated subsequently, i.e., negated in the very same locus where it was experienced. Therefore, the world is neither sat or real, nor asat or unreal. Advaita philosophers usually give the example of the experience of an illusory object—e.g., when one mistakes a rope for a snake in a dim light—to 280 T H E V E DĀ N TA D A R ŚA NA explain falsity. What does one see in such an illusory experience? One is neither perceiving a mental state, nor what does not exist, nor the rope that actually exists there, one in fact sees a snake out there in front of the perceiver, and this seeing—before the correction of the illusion—is hardly distinguishable from the veridical perception of a snake. However, when a person’s illusion is corrected, he does not see the snake any longer, and says “it was not a snake; it is a rope.” In this illusory experience, one remembers the qualities of a snake, and superimposes them on a rope. The superimposed is mithyā, that on which it is superimposed is real. In other words, the rope one mistakes to be a snake is a real rope—albeit only empirically real. Thus, when Śa ṃ kara argues that the empirical world is false, he is not saying that it is non-existent or unreal (non-being). The world is different from both the real (brahman) and the unreal (non-being). It is not real because it is sublatable. It is not unreal because unlike the unreal objects the world appears to us, it is not non-being. The objects of the world, though not ultimately real, possess a different order of reality; they are empirically real. This explains why Śa ṃ kara describes the world as different from the real, the unreal, and the illusory existence (snakerope illusions, mirage, etc.). It is the real that appears, and so every appearance has its foundation in reality. One does not experience a mirage in one’s living room, but only under certain empirical conditions. In this context, it is important to remember that falsity characterizes both the illusory objects and the empirically real objects; they are given (dṛśyatva). The distinction between the “illusory” and the “empirically real” is based on purely practical considerations; the distinction that the illusory alone is false (mithyā) is itself false (mithyātvamithyātva).26 Śā str ī in his commentary uses mithyātva (falsity) and sublatability (bādhitatvā) synonymously. He gives the following three meanings of mithyātva: 1 2 3 that which does not exist in the three divisions of time—past, present, and future; that which is removable by knowledge; and that which is identical with the object of sublation. Mithyātva (falsity) causes sublatability, which means that mithyātva and sublation are the same, because the instrumental suffx in “mithyātvena bādhitatvāt” conveys the sense of identity.27 Madhusūdana, in his Advaitasiddhi, gives fve defnitions of mithyātva. The thrust of the fve defnitions is that mithyā and its own absolute negation share the same locus.28 In this section, I have tried to emphasize the distinction between the false and the unreal. I do realize that it is diffcult to translate the term “mithyā” into English, because there is no word in the English language that exactly captures the connotation of “mithyā.” No matter how one translates it, one must not lose sight of the logical and ontological distinction between mithyā and unreal (asat), which is very crucial for a proper understanding of the Advaita school. The world in Advaita is not unreal. 281 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T Real, False, and Unreal Revisited Reality • • • • Reality was real, is real, and forever will remain real. It is unsublatable in the three divisions of time. It is non-dual. It is timeless, undifferentiated, unconditioned, non-duality. False (Empirical-Practical) • • • • • False is neither real nor unreal. False is sublatable. False is empirically real, was empirically real, and forever will remain empirically real. False functions in duality and multiplicity. False is indescribable. Unreal • • • Unreality was unreal, is unreal, and will forever remain unreal. Unreality is non-being. It neither can nor cannot be sublated by any experience. Theory of Causality Given that the world is false, the question arises, what precisely is the relationship between the brahman and the world? In what sense, if any, is the brahman creator of the world? There are two main theories of causality in Indian philosophy. The NyāyaVaiśeṣika asatk āryavāda holds that the effect is non-existent in the cause prior to its production, so that the effect is a new entity, a new beginning. The Sāṃ khya defends the opposite point of view, namely, satk āryavāda, or the view that the effect is already there in the cause, that there is no new beginning, and that the effect is a transformation of the material cause.29 The Advaita Vedānta rejects the Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika view on the ground that what is non-being can never come into being, that sat (being) cannot arise out of asat (non-being)—that if it could, then anything would arise out of anything. The Advaita subscribes to the Sāṃ khya view that the effect pre-exists in the 282 T H E V E DĀ N TA D A R ŚA NA cause, that nothing new can ever come into being. Though Śa ṃ kara subscribes to the Sāṃ khya theory of causation that the effect pre-exists in the material cause prior to production to explain the relation, he replaces the Sāṃ khya’s real transformation theory (pari ṇāmavāda) by effect being only a seeming, an apparent modifcation theory (vivartavāda) of the cause; there is no new production, nothing new arises, there is only a seeming production and destruction. The cause and the effect, argues Śa ṃ kara, are non-different. The cause, i.e., the brahman, possesses many powers. An ocean, which is one, has different modifcations in the form of waves, foam, ripples, etc., but in reality these modifcations are not different from the ocean; similarly, one brahman assumes many forms, which are non-different from the brahman. 30 For Śa ṃ kara, non-difference (ananya) of the cause and the effect means that “the effect is none other than the cause.” 31 For example, when a gold ring is made out of gold, it assumes a circular form (effect). Here, the form changes, but the gold still retains its essential nature, i.e., the basic nature of being gold. Thus, the effect, i.e., the ring, insofar as it shares this essential nature with its own cause, is not other than its cause (gold). Likewise, the brahman, in its creative aspect (known as Īśvara, the lord, the sagu ṇa brahman), is both the material and the effcient cause of the world. 32 Reality is unchanging, and all change is apparent. Only in this sense the brahman is the cause of this world. Śa ṃ kara’s theory of causation raises many questions and concerns. In his refutation of Sāṃ khya conception that non-sentient ( ja ḍa) prak ṛti is the cause of the world, Śa ṃ kara categorically declares that the cetana (sentient) brahman, and not acetana prakrti, is the cause of the universe.33 However, he also maintains that the effect is non-different from its cause.34 Opponents argue that if the effect is non-different from its cause, how can an insentient world have sentient brahman as its cause? Its cause can only be another insentient entity. An examination of the meaning of the concepts “ ja ḍa” and “ananya” would clarify the situation. Given that Sāṃ khya is a dualistic school of Indian philosophy, based on the bipolar nature of experience, it postulates two diametrically opposed principles: Prak ṛti and puru ṣa. Prak ṛti is insentient, meaning it “lacks sentiency” ( ja ḍa); sentiency characterizes puru ṣa. For Śa ṃ kara’s Advaita, “ ja ḍa” means “non-manifestation” of sentiency, but not “lack” of sentiency. Thus, Śa ṃ kara argues that the world’s being insentient does not pose any problem for his system, and the cetana (sentient) brahman can be the material and the effcient cause of the world. Again, Śa ṃ kara argues that in asserting cause is non-different from the effect, he is not asserting that cause and effect are identical; effect (the world), though non-different from the cause (the brahman), is not identical with it. In other words, though the effect is of the nature of the cause, the cause is not of the nature of the effect.35 I will again use the earlier example of a ring made of gold. Śa ṃ kara argues that the change of form (change into a circular ring) 283 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T does not affect the integrity of gold. The effect (the ring), insofar as it shares this essential nature with its cause, is none other than its cause (gold). There are characteristics of the effect (ring) that do not belong to its cause (gold), e.g., the circularity of the ring (effect). Characteristics of a ring (as a ring) are never the characteristics of the gold (as gold). Likewise, though the world, as an effect of the brahman, is none other than the brahman, the world still can have its own features that do not characterize the brahman, and those features do not affect the integrity of the brahman. Śa ṃ kara devotes the entire frst chapter of his BSBh to establish that prak ṛti as the cause of the world is based neither on śruti (scripture) nor on yukti (reason). Many post-Śa ṃ kara schools also subscribe to the view that the insentient world has an insentient cause; they maintain that the brahman serves as the ground of the insentient m āyā, the actual material cause of the world. For Śa ṃ kara, however, there is only non-manifestation of sentiency. Hence, the argument is that, though the effect is of the nature of the cause, the cause is not of the nature of the effect. Thus, though the brahman creates the appearance of the world, the brahman remains unaffected by the world appearance. Śa ṃ kara uses the analogy of a magician and his tricks to further explain this point. When a magician makes one thing appear as another, spectators are deceived by it; however, the magician himself is not deceived by it. Similarly, the brahman is that great magician who conjures up the world appearance, makes the multiplicity of names and forms appear, and deceives us. However, the brahman is not deceived by these tricks. The world is not unreal; it is an appearance of the brahman, and it has no reality apart from the brahman. 36 Finite individual beings are deceived by this appearance; they mistake appearance for reality. If the question is asked: Why create at all? Śa ṃ kara would respond by saying that it is “līl ā,” i.e., the divine play;37 it proceeds from the nature of the brahman. As kings engage in acts without any motive, without any purpose; similarly, the brahman projects the world appearance without any motive, without any purpose or necessity. It is like a children’s play, an activity flled with fun, and this activity does not jeopardize the brahman’s oneness. There is no “why” of creation. Epistemological appearance comes frst. Avidyā exists prior to both the individual self and God. This, however, does not mean that avidyā is temporally prior to the individual self and God, because the relationship is beginningless; temporality is not an issue here. When viewed logically, we must have a conception of avidyā prior to arriving at the conceptions of God and the individual self. Ontologically, the brahman comes frst. Once ignorance is destroyed by the knowledge of the real, the individual self is no longer subject to ignorance. Hence, the next question is: What is the relationship between the individual self and the brahman? How does a fnite individual dispel ignorance and see the brahman as brahman? This brings me to the last part of the Śa ṃ kara’s assertion, i.e., the non-difference between the empirical individual and the brahman. 284 T H E V E DĀ N TA D A R ŚA NA The Finite Individual and the Brahman are Non-different In his BSBh, Śa ṃ kara categorically asserts that the fnite individual appears to be different from the ātman on account of the limiting adjuncts (upādhis). He, however, is non-different from the ātman, because it is the ātman who has entered in all bodies as jīvātm ā. Thus, we may call the jīva a mere refection of the ātman.38 Hence, the question is: What is the nature of this ātman of which the jīva is a refection? Ātman The Advaitins explain the nature of the ātman as follows. 1 2 3 4 5 6 The ātman is pure consciousness; it is self-luminous.39 Following the Upaniṣads, Śa ṃ kara argues that it is on account of the light of the ātman that an individual self sits, goes out, walks, etc. It is the light that illuminates everything. Given that ātman is not an object,40 none of the predicates that hold good of objects can be ascribed to it. Being radically different from objects in general, consciousness and (any) object cannot form an intelligible unity of the sort “consciousness-of-an-object.” Ātman or pure consciousness is neither in space nor in time. It is not born; it does not die.41 Not being temporal, and not being an object of any sort, the ātman by its very nature cannot be an object of any signifcant negation. For Advaita Vedānta, the expression “the ātman is not” is meaningless, a possible selfcontradiction, while “the ātman is” is a tautology, because the very negation of the ātman, as in the statement “the ātman is not,” testifes to the existence of the ātman. Whereas Descartes restricts the argument to doubt (“that I am doubting cannot be doubted”), the Advaitin argument is: “the act of negating consciousness is an act of consciousness, and so is incoherent.” Ātman is self-established.42 A consequence of this last thesis is that the self is eternal, having no beginning (that is to say, has no antecedent-negation), and no end (has no subsequent negation). To sum up, consciousness in Advaita is self-luminous, eternal, beginningless, undifferentiated, non-spatial, non-temporal, and non-intentional. One all-pervasive “spirit,” the ātman, appears as if it is divided in many centers of fnite consciousness, but that appearance is due to many psycho-physical complexes, i.e., mind-body, ego-sense, and buddhi which create the misleading impression that each psycho-physical organism contains a distinct consciousness. In truth, however, as the Upaniṣads say “I am he” which is how the wise man expresses his experience of the non-difference from the brahman (the “I” refers to the fnite jīva consciousness and “he” refers to the brahman consciousness). 285 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T J īva The goal of Advaita Vedānta, however, is to not simply understand the ātman but to know it, to realize it. So, the questions arose: How does ātman relate to the psycho-physical organism, or what we call “I”? How can one realize the true self, or the identity between the ātman and the brahman? The initial inquiry takes place in this context. Thus, the very question “who am I?” points to a kind of awareness of incompleteness and a desire to know more. Given that the brahman defes all characterizations and descriptions, it seemed entirely appropriate to the seers to begin with the self. So, the nature of the self became the focus of their investigation. The jīva, argues the Advaitin, is a combination of two heterogeneous principles: Ātman, pure consciousness, and matter, mind-body organism. So, an individual self is neither pure spirit nor matter but a blend of the two. It is reality as the ātman, or the soul is its essence and it is appearance or false as it is conditioned, fnite, and relative. The frst one, the essence, the ātman, is shared by all human beings; it is common to me, to you, and to her. The matter, the mind-body organism, is a set of contingent features which provide the description, whether I am a male or a female, whether I am a philosopher or a scientist, whether I am white or black, middle class or rich, etc. The wrong identifcation (adhyāsa) between the self and the not-self is the basis of our empirical existence. Just as in a snake-rope illusion, the snake is superimposed upon the rope (the rope is the immediate datum of experience, the snake is an object of past experience, and illusion arises when the qualities of a snake, which was perceived in the past, are superimposed on “this,” i.e., a given rope); similarly, fnitude and change that do not belong to the ātman, but are mistakenly superimposed upon it due to ignorance. The ātman, the innermost self of a person, is pure formless, undifferentiated consciousness. It cannot be canceled by any other experience. The ātman and the brahman are not two different ontological entities, but two different names for the same reality; the underlying self of the individual is the brahman (tat tvam asi or “thou art that” or “you are that”). The Advaita writers take recourse to two ways of describing the appearance of this difference. On the frst account, the one brahman appears as many jīvas in the same way as one moon appears to be many when refected in many different pools of water. The one consciousness is refected in many ego-buddhi complexes. On the second account, the situation is analogous to that between the one infnite space and the many fnite spaces, the latter arising from the former because of the many dividers (such as the walls of a room). The two accounts are known as theory of refection and the theory of limitation respectively. They use two different metaphors to understand the metaphysical situation of the one appearing as many. Though everything is brahman, and there is no other reality than the brahman, it is known by different names. In the brahman-experience, subject and object coalesce into each other. In this experience one realizes that the brahman, the unchanging reality, which underlies 286 T H E V E DĀ N TA D A R ŚA NA the external world of names and forms, is also the reality that underlies the internal world of change and appearances. Śa ṃ kara repeatedly affrms that the brahman and the ātman are one. Upon attaining the knowledge of reality (mok ṣa), ignorance disappears, the subject-object distinctions are obliterated, the distinction between the self and non-self vanishes, and one experiences the brahman as pure being, consciousness, and bliss. Hence, the question is: How does one attain this knowledge of non-difference? The Brahman-Knowledge or Mok ṣa The goal of Advaita Vedānta is to teach the non-difference of the ātman and the brahman, and to realize the state of highest knowledge. Such knowledge of non-difference dispels ignorance and “brings about” mok ṣa or freedom. Mok ṣa, argues Śa ṃ kara, is attained through jñ āna yoga, the path of knowledge. Like most Vedic systems, but more so than others, the Advaita Vedānta depends upon the Vedas and the Upaniṣads to substantiate its position and shows that jñ āna yoga leads to self-realization. Traditionally, in Hinduism, as we shall see in the chapter on the Bhagavad-G īt ā, three paths have been discussed: The paths of action, knowledge, and devotion. It is customary to hold that all three yogas, when pursued properly, lead to the same end, namely, mok ṣa (self-realization). Śa ṃ kara, however, argues that mok ṣa is the knowledge of the identity between the brahman and ātman. Karma (action) and bhakti (devotion), at most, can “bring about” the purifcation of the mind but cannot “bring about” fnal liberating knowledge. Thus, devotion to God, leading an ethical life, or surrendering one’s actions to God, no doubt useful, cannot lead to the realization of the brahman, which is the fnal goal of human endeavors. For Śa ṃ kara, the study of the Vedāntic texts is necessary to destroy ignorance. However, prior to pursuing such a study, one should prepare one’s mind to comprehend the deeper meaning of these texts. He discusses four qualifcations that make one ft to study the Vedāntic texts by channeling the mind in the proper direction: (1) One must be able to distinguish between appearance and reality, i.e., between the world and the brahman; (2) one must give up desires for pleasure and enjoyment, i.e., renounce all worldly desires; (3) one must develop qualities such as detachment, patience, and powers of concentration; and (4) one must have a strong desire to attain mok ṣa.43 After the mind is prepared, the aspirant goes to a guru (teacher) to study the Vedāntic texts. The Advaitins recommend a three-step process: Śrava ṇa (“hearing” that really consists of studying the Vedānta texts under a competent teacher), manana (refective thinking, i.e., thinking in order to remove all doubts about the Advaita theses as well as advancing one’s own arguments in support of these theses), and nididhyāsana (contemplative meditation which strengthens the beliefs reached through the frst two stages and culminates in the “intuitive” experience of one’s non-difference with the brahman). With the constant meditation on the great saying of the Upaniṣads, “thou art the 287 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T brahman,” one realizes that he is the brahman. The fnal liberating knowledge (of the form “I am brahman”) is an “intuitive” knowledge arising from the verbal instruction (of the form “you are that”). One has the immediate experience of the brahman; the person realizes that he/she is non-different from the brahman. The Advaitins call it “an immediate knowledge arising from the verbal instruction”—analogous to a wise man’s verbal instruction—“you are the tenth man.”44 The last cognition destroys the primal ignorance and the original nature of the self is revealed. This state is known as the state of jivanmukti, freedom in this life. Mok ṣa thus is not something that one looks forward to after death. It is a stage of perfection attained here; it is freedom while one is still alive. At death, such a person attains videhamukti, the absolute freedom from the cycle of birth and rebirth, a state of equanimity, serenity, and bliss. It is worth noting that mok ṣa “brings about” freedom only in a very Pickwickian sense. In truth, nothing happens, nothing changes; no perfection is really “brought about.” The attainment of mok ṣa is not a new production; it is the realization of something that was always there. The self is brahman, and the mok ṣa is already an accomplished reality. Once the ignorance which had been covering the true nature of the self is destroyed, the perfection that resides eternally in the self becomes known, and the eternally free nature of the self is manifested. In other words, mok ṣa is coming to realize one’s essence, which was forgotten during the embodied existence. It is the realization of one’s potentialities as a human being; it is the highest realization. A liberated person is an ideal of society, and his life worth emulating. After realizing mok ṣa, a liberated person helps others to realize mok ṣa. In other words, the liberated life is not a life of inactivity as some might assume. Scholars often argue that in a philosophy in which the brahman is the only reality, the world an appearance, all distinctions between truth and falsehood become meaningless. Such an argument is based on a misunderstanding of the Advaita position; it stems from a confusion between the real and the empirical. Prior to realizing mok ṣa, a person is responsible for his actions; he reaps the consequences of his actions and is subject to ethical judgments. In other words, from an empirical standpoint, distinctions between true and false are not only meaningful but also very important. It is only when mok ṣa is attained that everything is seen to be a product of ignorance. Good actions take one toward the brahman realization, and bad ones away from this goal. The brahman is not an object of knowledge (it is not like Hegel’s absolute coming to know itself); the brahman simply is. It is the highest knowledge. Advaita Epistemology Pram āṇas (Means of True Cognition) I will begin with the pram āṇas. My analysis in this chapter is primarily based on Ved ānta Paribh āṣā (VP),45 one of the most well-known Advaita epistemology 288 T H E V E DĀ N TA D A R ŚA NA texts, which offers its readers an analysis not only of the important issues surrounding the Advaita epistemology but also of the important ontological problems. Like all other systems, the Advaita Vedānta also developed a theory of knowledge. A true cognition is pram ā (true or valid cognition). A pram ā that excludes memory is a cognition which is not contradicted by any other cognition and has for its content an entity that is not already known. There are two types of pram ā: The pram ā that excludes memory and the pram ā that includes it. The former is the knowledge of an object that is neither contradicted nor previously known, and the latter is the knowledge of an object that is not contradicted by any other object of cognition. Non-contradiction is common to both defnitions. In the erroneous perception “this is silver,” the knowledge of silver continues to be true until the object of cognition (i.e., silver) is not contradicted by another object of cognition (i.e., shell). This implies that the knowledge of silver as silver must be true until it is not known that it is a piece of shell. The second characteristic of pram ā is novelty or previous unknownness. This characteristic excludes memory from the ambit of knowledge and raises the question of the status of persistent knowledge. When I look at a chair continuously, my experience of the frst moment of course is knowledge, but what about my experience of the subsequent moments? Is it knowledge? Notwithstanding different answers, most schools hold that one’s experience of subsequent moments is knowledge. The Advaitins, however, hold that such questions do not arise in their epistemology because for them a cognition is true until it is sublated by another cognition. The judgment “the table is” remains the same if it is not sublated, making the questions regarding reproduction, subsequent moments, etc., moot. Now, an opponent of the Advaita Ved ā nta may raise the following objection: For the Advaitin, an object, say, a pitcher (indeed, any material object), is just false. If that is so, how can its knowledge be a valid knowledge? The Advaitin’s reply to this question is as follows: Until the brahman is realized, the knowledge of a pitcher remains true. The word “uncontradicted,” when used to characterize the knowledge of a pitcher, means “uncontradicted prior to brahman-cognition.” A pram āṇa is the specifc cause of a pram ā.46 Ved ā nta Paribh āṣā discusses pram āṇas in its attempt to provide an answer to the basic epistemological question: How do we know? The Advaitins look to pram āṇas for removing doubts that may have arisen. They accept four pram āṇas that the Naiy āyikas do and add additional two to the list. Thus, the six pram āṇas that the Advaitins recognize are perception, inference, comparison, verbal testimony, postulation or presumption, and non-perception. Of these, perception is the most basic and of special importance; inference, comparison, and postulation are three non-perceptual pram āṇas; non-perception apprehends non-existence; and verbal testimony is a pram āṇa for sensuous as well as super-sensuous objects. 289 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T Pratyak ṣa (Perception) The term “pratyak ṣa,” derived from the roots “prati” (to, before, near) and ak ṣa (sense organ) or ak ṣi (eye), etymologically signifes what is “present to or before the eyes or any other sense organ.” It refers to sense-perception as a means of immediate or direct knowledge of an object. Broadly speaking, the Advaitins make a distinction between two kinds of perceptions: External and internal. Perception by any of the fve sensory organs (sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell) is external, and the perceptions of pleasure, pain, love, hate, etc., are internal. The Advaitins argue that perception is immediate consciousness.47 However, for them, sense-perception is not the only means of immediate cognition: The immediacy of cognition does not depend on its being caused by sense organs. God, for example, has no senses, but those who believe in God believe that they have immediate knowledge of things. The theory of perception that the Advaitins develop is a kind of identity theory: In a perceptual cognition, the inner sense goes out through the visual sense organ (in the case of visual perception) and assumes the form of the object out there. This modifcation is known as “vṛtti.”48 In reviewing Advaita literature, one fnds different translations of the term “vṛtti.” Śā str ī, for example, translates it as “psychosis.”49 Such a translation, however, having pejorative psychological connotations, is misleading. Vṛtti is an epistemic process or act. Let me elaborate. Briefy, a vṛtti is a mental modifcation that after assuming the form of the object enters the inner sense (antaḥkara ṇa), a passive instrument illumined by the sāk ṣin (witness-consciousness).50 The inner sense effects the connection between the vṛtti and pure consciousness. In other words, as we will see shortly, the perceptual process assumes the following form: The object is presented, the vṛtti goes out, assumes the form of the object, and transports it to the inner sense, which presents the vṛtti to the sāk ṣin, which, in turn, illumines it. It contains the following fve steps. 1 2 3 4 5 The inner sense meets the organ of vision, reaches out to the object, and becomes one with it. The mental mode removes the veil of ignorance that had been hiding the object from the perceiver. The consciousness underlying the object, being manifested because of the removal of the veil of ignorance, reveals the object. The mind effects an identity between the consciousness conditioned by the object and the consciousness conditioned by the subject. As a result, the cognizer perceives the object. The Advaitins explain the process with the help of an analogy: Just as the water of a tank, having come out of an aperture, enters a number of felds through channels assuming like those [felds] a 290 T H E V E DĀ N TA D A R ŚA NA quadrangular or any other form, so also the inner sense, which is characterized by light, goes out [of the body] through the door [sense] of sight, and so on, and [after] reaching the location of the object, say, a pitcher, is modifed in the form of the objects like a pitcher. This modifcation [of the inner sense] is called a “mental mode” (vṛtti). In the case of an inferential cognition, and so on, however, there is no going out of the inner sense to the location of fre, because fre, and so on [other inferred objects], are not in contact with the sense of sight, and so on [other sense organs].51 The point that the Ved ānta Paribh āṣā is trying to make is as follows: Just as the water of a tank goes out through a hole, enters into a feld, and assumes the form of the feld, rectangular or some other shape; similarly, the mind, the inner sense, which is luminous, goes out through the eye, etc., and takes on the form of the object. In the perception of a pitcher, for example, the mental mode and the pitcher occupy the same space. When one perceives a pitcher and says, “this is a pitcher,” the mental mode or vṛtti having the form of the pitcher, the consciousness limited by the pitcher and consciousness limited by that mental mode become non-different. This is how the pitcher is perceived. One consciousness becomes threefold depending upon the limiting condition. The object-consciousness is the consciousness limited by the object (vi ṣaya), e.g., a pitcher. Pram āṇa consciousness is the consciousness limited by the mental modifcation. The subject- consciousness (pram āt ṛ) is the consciousness limited by the inner sense. In perception, an identity between these three is accomplished. Accordingly, pure consciousness, from an empirical point of view, becomes threefold: The object-consciousness, the means-of-cognition consciousness, and the cognizer-consciousness. From the perspective of pure consciousness, these divisions are only apparent and not real; the plurality of objects is only apparently independent of the subject, but not truly independent. It is worth noting that the Advaitins do not regard “being caused by sense organs” (as opposed to Nyāya) a defning property of perception. Perceptuality, as applied to a cognition, is made possible by a cognition on account of the identity of consciousness limited by the pram āṇas and the consciousness limited by the object. The Advaita theory of identity is a corollary of its metaphysics: Only brahman or pure consciousness is real; it is all pervading, undifferentiated consciousness. Pure consciousness is also pure existence or being, and assertions made about the latter are equally applicable to the former. Just as a claypitcher does not have any independent existence apart from the clay; similarly, the objects do not have any independent existence apart from the pure consciousness, their source. In other words, these objects, though empirically real, are not real in themselves. The same can be asserted about the pure consciousness in a cognitive relation, which involves such elements as subject, object, and their relation. These elements are real insofar as they refer to pure 291 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T consciousness but are not real in themselves. The Advaitins reiterate that as identical with pure consciousness, these three terms of a cognitive relation refer to the same reality. Perception is of two kinds: Savikalpaka (determinate) and nirvikalpaka (indeterminate).52 The former apprehends relatedness of a substantive and its qualifying attribute. This occurs in the cognition “I know the pitcher.” The latter is that knowledge which does not apprehend such relatedness, as in the case of such identity statements, “this is that Devadatta” or “thou art that” or “you are that.” It is worth noting that the identity statement “thou art that” is not a tautology and cannot be expressed as x = x.53 In logic, most contemporary philosophers hold a tautology is a sentence that is true solely by virtue of its formal structure. Some people reserve the word “tautology” simply for logical truths, or, possibly, for the subset of logical truths of propositional logic. Others use the word in a broader sense, such that not only logical truths but also analytic propositions, i.e., the propositions which are reducible to logical truths, defnitionally would be considered tautologies. One must be very careful to understand the sense in which “thou art that” is an identity statement; it is not a tautology because what is meant by the ātman for the individual is different from what is meant by the brahman for the individual. “Thou art that” is very similar to such statements as “this is that Devadatta.” When I perceive Devadatta for the second time and report to my friend “this is that Devadatta” I saw yesterday, I do not mean to suggest that the two places and the times are identical. When I saw Devadatta yesterday he was in a school, and today I see him in the King of Prussia Mall. He was happy yesterday, and he is in pain today. The identity is the identity of “person” devoid of all accidental qualifcations. The same characterizes “thou art that,” where the individual self as pure consciousness is identical with the brahman, the pure consciousness. To sum up, the immediacy of knowledge does not depend on its arising from the senses, but rather on the object that is presented. The immediacy of the object presented to consciousness makes possible for knowledge to be perceptual. Although the phenomenal world rests on a distinction between cognition and content, no such distinction exists in the immediate consciousness of the brahman. Pure consciousness accordingly is the criterion of the perceptibility of objects. Since the cognizer-consciousness and the objectconsciousness, e.g., a pitcher, share the same consciousness, in the perception of a pitcher, the pitcher becomes “immediate.” Perception thus is of utmost importance, because the knowledge obtained is immediate, which is different from the non-perceptual knowledge obtained by inference, comparison, and postulation. Anum āna (Inference) The next pram āṇa is inference (anum āna), which is the special cause of an inferential cognition or anumiti, literally, “the consequent knowledge” (from anu = 292 T H E V E DĀ N TA D A R ŚA NA after, and miti = knowledge). Here the Advaitins draw our attention to the fact that an inferential cognition is caused by the knowledge of an invariable concomitance purely as the knowledge of the invariable concomitance. Ved ānta Paribh āṣā defnes anumiti as the cognition that is produced by the knowledge of vyāpti qu ā the knowledge of vyāpti (vyāpti being the invariable relation between what is inferred and the reason). The “qu ā …” is inserted to avoid the defnition being too wide by applying to the unintended case of mental, secondary, reception of the knowledge of vyāpti. Vyāpti is the relation of having the same locus belonging to the sādhya in all the loci of hetu.54 I will illustrate this point with the help of an example typical of Indian philosophers, including Advaita. Whatever is smoky is fery, e.g., a kitchen, The hill is smoky, Therefore, the hill is fery. [There are three terms: Hetu (the middle term, smoky), sādhya (the major term, kitchen), and pak ṣa (the minor term, hill).]55 Here the vyāpti is “wherever there is smoke, there is fre,” i.e., wherever there is hetu, there is sādhya. The sādhya, in other words, is present in all those places where the hetu is present. Vyāpti, in other words, is “having the same locus” between a sādhya which is present in all the loci of the hetu. The Ved ānta Paribh āṣā adds that vyāpti between the fre and the smoke exists when the fre co-exists in all the cases of the smoke and is never known not to accompany the smoke. This universal relation must have been cognized on a previous occasion and must be cognized, or better yet re-cognized, in this instance (the hill) for inferential knowledge to occur. Cognition of a universal relation, though necessary, is not a suffcient condition of the inferential knowledge. However, the cognition as well as the re-cognition of a universal relation together constitute the necessary as well as suffcient conditions. According to the Naiyāyikas, we frst see smoke on the hill, then remember that wherever there is smoke, there is fre as in our kitchen; consequently, there is smoke on the hill, which is a mark of fre, and we conclude that there must be fre on the hill. We shall see where the Advaitin account differs from the Nyāya account. For the Naiyāyikas, the parāmarśa, i.e., the cognition of the hetu for the third time, is the instrumental cause of inferential knowledge.56 The Advaita rejects this theory and refuses to consider parāmarśa in any sense to be the cause of an inferential cognition. The cognition of the invariable concomitance is an instrument only with respect to the knowledge of fre, and not with respect to the knowledge of the hill. Hence, the knowledge “this hill has fre” could not have been inferred regarding the hill. The knowledge in the case of the hill is an instance of perception. The Advaitins, like the Naiyāyikas, classify inference into inference for one-self (svārtha) and for another (parārtha). Whereas the Naiyāyikas recognize a valid inference for another to have fve members,57 the Advaita Vedānta 293 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T recognizes only three members. The three members that suffce are the proposition to be established (known as pratijñ ā), the reason (hetu), and the example (i.e., ud āhara ṇa). In a concrete case, it is enough to argue that the hill has fre, because of smoke, as in the kitchen. The Advaita logicians then proceed to prove one of their central theses, i.e., the empirical reality of the world, by an appropriate inference. The inference58 runs as follows: Everything other than the brahman is false Because it is other than the brahman Whatever is other than the brahman is false, e.g., the shell-silver. An appropriate defnition of falsity would be: “something being the counterpositive of the absolute non-existence in whatever is supposed to be the substratum.” Another way of proving the falsity of whatever consists of parts is this: “A cloth is a counter-positive of the absolute nonexistence abiding in the threads, because it is a cloth, as is the case with any other cloth.” The falsity of all things is the property of being the counter-positive of absence in all things appearing as its locus. The Advaitin obviously refuses to accept the Nyāya thesis that the whole resides in its parts in the relation of samavāya (inherence).59 Upam āna (Comparison) Knowledge obtained from comparison (upam āna) is derived from the judgments of similarity, i.e., a remembered object is like a perceived one. Judgments based on comparison are of the kind “Y is like X,” where X is immediately perceived, and Y is an object perceived on a previous occasion which becomes the content of consciousness in the form of memory.60 The Advaitins consider a typical instance of comparison given by Indian philosophers. A person has a gau (domestic cow), knows what it looks like, and has the capacity to apply its features to other cows. Upon running into a gavaya (a wild cow) in a forest he says, “this wild cow resembles my domestic cow.” Then, he concludes, “my cow resembles this wild cow.” This knowledge of the similarity of my domestic cow with the wild cow seen in the forest is “upamiti.” Its proximate cause is upam āna, the knowledge of the likeness with a cow which exists in a wild cow. The Advaitins emphasize that this knowledge is neither perception nor memory. It is not perception, because of the two cows under consideration only one is perceived; it is not memory, because my domestic cow, which was perceived in the past, is now recollected, and not its similarity to the wild cow that is now being perceived in the forest. So, a person gains a new or better knowledge not about the wild cow, but about my domestic cow. The similarity attaches to the domestic cow; it is similarity with a wild cow. In other words, this similarity is not perceived, because when one knows this similarity, there is no sense contact with the domestic cow. Nor is this knowledge based on an 294 T H E V E DĀ N TA D A R ŚA NA inference, because the similarity of a cow with a wild cow cannot be the mark or the hetu of the likeness of the wild cow in a cow. To put it differently, inference requires a universal premise; no such premise is needed in the knowledge by similarity. Thus, comparison, argue the Advaitins, deserves the status of a separate pram āṇa. Śabda (Verbal Testimony) For the Advaitins, verbal testimony “is a means of valid knowledge in which the relation among the meanings of the words that is the object of its intention is not contradicted by another pram āṇa.”61 They further argue that a sentence is the unit of a verbal testimony. In other words, a sentence signifes more than the constituent words that compose it. To grasp the signifcance of a sentence, one must know not only the meanings of the constituent words but also the relation among the meanings of the words conjoined syntactically. The apprehension of this relation is the verbal cognition, and, if it is not contradicted, it is valid. Four causes produce the cognition of a sentence: Expectancy (āk ānk ṣā), appropriateness or competency ( yog yāta), contiguity (āsatti), and the knowledge of intention (t ātparya).62 Expectancy is the capacity of the meanings of the words to become objects of enquiry about each other.63 Hearing about action gives rise to the expectation about something connected with the action, the agent, or the instrument of action. For example, the sentence “get the umbrella” gives rise to a cognition. However, if the words “umbrella” and “get” are uttered separately, there would be no cognition. If only the word “umbrella” is uttered, the question would arise what to do with the umbrella? If only “get” is uttered, the question would arise, “get what”? In other words, for a cognition to arise, both “umbrella” and “get” are required. Competency or appropriateness64 is the non-contradiction of the intended relation desired to be set up in a combination of ideas. A sentence like “sprinkle fre on the grass to moisten it” lacks appropriateness, as fre can neither be sprinkled nor can it moisten anything. By “contiguity” is meant that the meanings of the words are to be presented without interval.65 Thus, the words must be uttered without a long temporal interval between them. “The door” requires to be preceded without a long interval by the verb “close” to close the door. Words, argues the Advaitin, have primary as well as secondary meanings.66 Primary meaning is something that is directly meant by a word. A word in its primary meaning signifes a universal and not the particular in which it inheres. For example, the word “cow” stands for “cowness.” A universal, in other words, is not an entity that stands over and above the individuals; rather, it refers to the essential characteristics that are common to all members of that class. Thus, whereas the universals or class characteristics constitute the primary meaning of the words, the individuals constitute 295 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T their secondary meanings. In other words, though the word “cow” primarily means “cowness,” it may by implication signify those individual cows as possessing universal cowness. To suppose that the word has the power to designate infnite number of individual cows would be to violate the principle of economy. Individual cows are meant by a secondary power of designation or implication (lak ṣa ṇa).67 A secondary meaning is something that is implied by a word. If the primary meanings of the words of a sentence do not adequately explain the import, then one looks for the implied meanings. Lak ṣa ṇa or secondary designation is of two kinds: Bare implication and a secondary designation that depends upon another lak ṣa ṇa, i.e., implication by the implied. Bare implication functions when the secondary meaning itself is related to the primary meaning. For example, this occurs in “the village on the Ganges,” which secondarily means “the village on the bank of the river.” The second kind of implication occurs when there is no direct relation to express the primary meaning. For example, the primary meaning of the word “dvireph ā,” i.e., “having two rephas” is “having two r’s,” but secondarily it means a “bee.” A similar secondary designation occurs when one says, “a human like a lion,” where not lion but lion’s courage and strength characterize the human concerned. Secondary meanings are of three kinds68: In the frst, jahallak ṣa ṇa, the primary meaning is dropped in favor of a secondary meaning. For example, when after learning that a person is about to dine with his enemy, you tell him “go and take poison.” The intention here is not to ask the person to take poison but to make the point that dining with an enemy is “like taking poison.” In the second, the primary meaning is there but the secondary meaning comes into play. In the sentence “white cloth,” “white” includes “the property of whiteness” and by implication denotes the substance that the white color characterizes. Thus, there is a cognition not only of the expressed sense but also of the implied sense. This is “ajahatlak ṣa ṇa.” In the third, a part of the original primary meaning is dropped, but another part is retained. When seeing a person “Devadatta,” one says, “this is that Devadatta,” “this” and “that” are taken to be the purport, and the meanings in terms of spatio-temporal locations are dropped. Only the identity between the “this” and the “that” Devadatta is asserted leaving aside the differences. This is “ jahatajahatlak ṣa ṇa.” Very often, the principle of seeking a secondary meaning is employed to harmonize scriptural statements with one’s own philosophical position. For example, in construing the meaning of the sentence “you are that” or “thou art that,” the primary meanings of “you” or “thou” as “individual consciousness,” and “that” as the “pure consciousness” are set aside, and they are used in their secondary meanings: The consciousness that underlies pure consciousness is the same consciousness that underlies the individual consciousness, thereby declaring that the text affrms the identity between the individual and the non-dual pure consciousness. 296 T H E V E DĀ N TA D A R ŚA NA Tātparya or intention is the capacity to produce cognition of a specifc thing.69 The question becomes important when there is doubt as to whether a sentence means this or something else. In such cases, i.e., when a word has more than one meaning, the context helps us to determine the intention of the speaker. For example, what does “saindhavam-anaya” mean? Does it mean “bring a horse” or “bring some salt”? Generally, context helps us to decide. In the case of the Vedic sentences, reasoning aided by the principles of interpretation is required. In all identity texts, the content is the capacity of a sentence to convey a meaning, not simply the senses of the words. If this is not accepted, there would be the danger that the word senses might be construed as the sense of the sentence-generated cognition, and if that happens, unintended relations may become the content of such a cognition. Arth āpatti (Presumption or Postulation) The Advaita Vedā nta recognizes a unique mode of argument as a pram āṇa called “postulation.” The argument is somewhat like what is known as the “transcendental argument” in Western philosophy. The knowledge obtained from postulation (arth āpatti) involves assuming or postulating a fact to make another fact intelligible. Supposing there is a fact p. If you say p is possible only if q, then you establish the validity of q. To take an example, let p be “Devadatta is growing fat even when he does not eat during the day.” One must assume that, barring physiological problems, he eats at night, because there is no way of reconciling fasting and the gaining of weight. Therefore, Devadatta eats at night. In short, in arth āpatti, one assumes a fact without which a thing cannot be explained. The knowledge of the thing to be explained is the instrument and the knowledge of the explanatory fact is the result.70 There are two kinds of presumption: Postulation from what is seen (dṛṣṭārth āpatti) and postulation from what is heard or known by testimony (śrut ārth āpatti). In the frst, one supposes a fact to explain a perceived fact. For example, in a shell-silver illusion, when the judgment “this is not silver but a shell” negates the initial judgment “this is silver,” we assume that the seen silver must be illusory. The second involves the postulation of an implied meaning of a sentence either heard or read, when the direct meaning is incomplete. For example, “one who knows ātman overcomes all suffering.” This can be true only if suffering destroyed by knowledge has the status of falsity. Only falsity is negated by another knowledge. In other words, the validity of this judgment is possible only if we assume that grief is false. The second is of two kinds: Abhidh āna (the supposition of a verbal expression) and abhihita (supposition of a thing meant). In abhidh āna, on hearing the part of a sentence, there is the supposition of a verbal expression, for example, when the master of the house simply says “dvāram,” i.e., the door, the servant has to supply “close.” The abhihita occurs when what is heard has no consistent 297 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T meaning, so that the hearer supposes some other thing, e.g., upon hearing, “one who desires heaven should perform jyoti ṣṭoma sacrifce,” it is assumed that sacrifce must give rise to some unseen result.71 Anupalabdhi (Non-Apprehension) Non-perception is another pram āṇa that the Advaita recognizes; it is the specifc way we perceive absences. It yields knowledge of an absence, where an object would be immediately perceived if it were there. Judgments based on anupalabdhi are of the sort “there is no X in the room,” where X is an object which would have been perceived if it were there.72 To put it differently, if a pitcher were on my desk, I would have seen it in a well-lit room. The resulting knowledge of the nonexistence is perceptual; nevertheless, its instrumental cause, viz., non-apprehension, is a distinct means of knowing. The knowledge derived from anupalabdhi has the following features: Such a knowledge has for its object something non-existent, immediate, and it cannot be produced by any other pram āṇa. Every instance of non-perception, however, does not prove its non-existence. A person does not see a chair in a dark room, which by no means proves that the chair is not there. Hence, nonperception occurs under appropriate conditions. It is important to remember that the six pram āṇas of the Advaitins have limited applicability. By demonstrating the insuffciency and the relative nature of the six pram āṇas, the Advaitins pave the way for their transcendence to the brahman, the highest knowledge, the truth. Two Forms of Knowledge and the Theory of Intrinsic Validity There are two forms of knowledge: The higher knowledge ( parāvidyā) and the lower knowledge (aparāvidyā). The frst is the knowledge of the absolute; it is sui generis. It is attained all at once, immediately, intuitively. The second is the knowledge of the empirical world of names and forms, where the pram āṇas (means of true cognition) are operative. All pram āṇas hold sway as “ultimate” until the brahman is realized, because when the brahman is realized nothing remains to be known. Each of the six pram āṇas has its own sphere of operation. They do not contradict each other. They are “true” only in the phenomenal world, but none of the pram āṇas are ultimately “true.” The Advaitin doctrine of the intrinsic validity of knowledge supports and further explains what the Advaitins mean by this equivocation. The Advaitins argue that: 1 2 the function of knowledge is to manifest the object as it is; within dream, a cognition may lead to successful practice about the dream object; and 298 T H E V E DĀ N TA D A R ŚA NA 3 knowledge is true so long it is not contradicted by a subsequent experience. In the strict sense, only uncontradicted experience is ultimately true; however, the Advaita at the same time holds that no empirical knowledge satisfes both. Only the knowledge of brahman does. Any empirical cognition is in principle falsifable, but so long it is not falsifed, it is taken to be true by the cognizer. Thus, it is not the truth, rather the falsity that happens to a cognition. The last sentence raises the following questions: Is the truth of a cognition apprehended intrinsically or extrinsically? Is the falsity of a cognition apprehended intrinsically or extrinsically? Advaita subscribes to the theory of extrinsic (parataḥ) invalidity, but to the theory of intrinsic validity (svataḥ), because the validity arises from the very conditions that produce it. The Advaita Vedānta theory of the intrinsic validity consists of the following theses: 1 2 3 every cognition, as it were, is eo ipso, taken by the cognizer to be true independently of any test; there is indeed no criterion of truth; and there is a criterion of falsity. Before proceeding further, let us pause briefy, and discuss what is meant by the words “svataḥ (intrinsic)” and “parataḥ (extrinsic).” Let C1 be the cognition under consideration, and for my limited purposes here, my question may be reformulated as follows: Is it the case that the same cognition, which apprehends C1, also apprehends the truth or falsity of C1? If cognition C2 apprehends C1, if C2 also apprehends the truth or falsity of C1, then the truth of C1 will be intrinsic. If, however, C2 apprehends C1 without at the same time apprehending it as true or false, and if a later cognition determines the truth or falsity of C1, then the truth or falsity will be extrinsic. Thus, there are four combinations of possible answers, and these four combinations represent the position adopted by the Indian thinkers. For the Naiyāyikas, both truth and falsity are extrinsic. For them, knowing is a temporal act directed toward an object. It is a property of the self and is expressed in such judgments as “this is a desk.” Here, the desk is the object of knowledge, and a cognition reveals only the object. It does not reveal either the cognizer or the cognition itself. This primary cognition (vyavasāya), they argue, is revealed by a second introspective awareness of the form “I know the desk,” or “I have the knowledge of the desk.” The second cognition or the cognition of the primary cognition is “anuvyavasāya.” Whereas the object of the primary cognition is the desk, the direct object of the second cognition is the primary cognition. To put it differently, when C2, apprehends C1 in a refective introspection, C1 is not apprehended either as true or as false. One needs a subsequent verifcatory confrming evidence for determining its truth or disconfrming evidence for determining it as false. So, both truth and falsity are extrinsic. 299 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T The Advaitin conception in this regard is quite different from the Naiyāyika conception. For the Advaitins, a cognition is an event in time. One does not and cannot determine the truth of a cognition by applying any criteria, because such an application itself would be the case of a cognition whose truths itself would have to be determined by another cognition, and this process will go on ad infinitum. So, the Advaitins defend another combination of the possibilities; the truth is intrinsic to a cognition, but the falsity is extrinsic, i.e., a cognition is apprehended immediately as true prior to the subsequent confrmation or disconfrmation; however, later experience might prove it to be false. The Advaitin argue that when I apprehend an object, the object undoubtedly is revealed; however, the object is not the only thing that is revealed. It is accompanied by an apprehension of apprehension. When I say this is a desk, I not only know the desk but also know that I know this is a desk. The two apprehensions occur simultaneously. “This is a desk” is an instance of perception; however, the perception itself is apprehended by the witness-consciousness. The above makes it obvious that the real questions are not “what is truth” or “what is falsity”? The real question is: “when is a cognition apprehended to be a true or false?” The Naiyāyika account provides an interesting possibility. When by introspection I come to apprehend a cognition that has just occurred in me, for example, when I perceive a snake, I am not perceiving it as either true or false. I am refectively perceiving that I have a perceptual cognition. Or, take the Advaitin counterclaim, to know that I have a cognition, is eo ipso to know that I have a true cognition. This determination of truth continues until it is sublated by a contradictory disconfrming evidence, so that on the Advaitin theory, the truth is intrinsic, whereas the falsity is extrinsic. The concern, then, is not with the truth as such, but with the truth determination. The same characterizes falsity. Western epistemologists, I suspect, will reject such questions as being psychological in nature, and of no philosophical import. The above makes it clear that in the Indian theories of truth, a theory of falsity plays an important role. In Advaita Vedānta, the theory of falsity is central to their metaphysical and epistemological projects so much so that they defne falsity frst, and then proceed to defne the truth. Let us see how this works, and why such a move is necessary for the Advaitins. The Advaitins do not accept what Kant calls the nominal meaning of truth, viz., that a true cognition knows its object precisely as it is, not because some true cognitions are true without satisfying it, but because what they call “false” cognitions also satisfy it. Let me explain it with the help of an example used to explain an illusory cognition. In a snake-rope illusory cognition, I see a rope as a snake. On the Advaita view the object which this cognition apprehends is not the rope but a snake; so, the property of being a snake which the cognition ascribes to its object truly belongs to it. If the opponent argues that the object of this cognition is really a rope, the Advaitin will question the opponent’s defnition of “being an object.” If the object is that which a cognition manifests or shows, then it is the snake which is the object, and not what is not 300 T H E V E DĀ N TA D A R ŚA NA manifested in that cognition. If a rope can be the object of that cognition, even when it is not manifested, then anything can be the object of any cognition. The opponent may say in response that the object of this cognition is simply “this”; the Advaitin would agree and argue that the cognition manifests “this” as a snake, and one really does see a snake. The subsequent cognition, the so-called correction, shows that this is really a rope and not a snake. It means that the object of the new cognition is a rope; it does not prove that in the earlier cognition the defning truth was not present. Thus, the Advaitins conclude that the agreement with the nature of the object cannot serve as a defnition of the truth. It may be asked: Is the truth the ability to generate successful practical response? The Advaitins answer this question in the negative and argue that even a cognition that is false in the ordinary sense may lead to successful practice. Let me give an illustrative example: In a dream one feels thirsty, sees the water at a distance, walks up to the water, drinks it, which quenches his thirst. Upon waking up from the sleep, he realizes that it was a dream, and his cognition of water false. The Advaitins argue that though his cognition of water within his dream led to the quenching of his thirst in the context of the dream, and gave rise to a successful activity, his cognition of water was false. So, the defnition of truth as the ability to generate successful practical response cannot be accepted. The Advaitins in this regard differ not only from the Naiyāyikas but also from the Prabhā kara M īmāṃsakas. Prabhā kara M īmāṃsakas, like the Advaitins, subscribe to the theory of the intrinsic validity of knowledge. The M īmāṃsakas, however, prove the intrinsic validity of knowledge by showing that there are no false cognitions (akhyāti), that every knowledge reveals its own object, and that the so-called erroneous cognition is really a case of nondistinction between two different cognitions: Perception (“this”) and recollection (“snake”). Each one of these by itself is true, but owing to the nondistinction between them, one mistakes the memory for a perception, and identifes the object of the memory with the object of perception. The Advaitin does not accept akhyāti strategy; because he believes that the perception of a snake is really a perception not a memory, and what we perceive is not a rope mistaken for a snake, but a snake produced there by the perceiver’s ignorance having the property “snakeness.” The Advaitins therefore follow another strategy. They argue that every cognition manifests its own object and not the object of another cognition. From this it follows that every cognition arises with its own claim to truth. But the claim to truth is not an additional property of a cognition; it is intrinsic to it. To know is to have a true cognition, and no additional criterion of truth is required. However, on the Advaita view, every empirical cognition may, at some time or other, be contradicted. Such contradictions show that the claim of the frst cognition to be true cannot be sustained and the cognition is now known to be false. The consequence is that falsity has a criterion, but truth does not. Some Advaitins use this to arrive at a defnition of truth—“a cognition is true as long as it is 301 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T not known to be false.” This feature is constitutive of knowledge claims, the claim to truth is not an additional claim over and above the claim to know. But this claim is contradicted; it is taken back and one takes the earlier cognition to be false. On the Advaita view then the truth is intrinsic to knowledge; falsity, however, is extrinsic. There are genuine false cognitions in which one thing appears to be what it is not. The object of the erroneous cognition, an object that is contradicted, is indescribable either as sat or asat. Only the brahman experience is uncontradicted. Thus, the lack of uncontradictedness while securing the validity of the pram āṇas leads to the thesis that none of the knowledge gained by the pram āṇas is ultimately true. All knowledge gained through pram āṇas may be contradicted by an insight, an “intuitive” experience, that is qualitatively superior, the highest knowledge ( parā vidyā), which dispels ignorance. The claim—knowledge gained through the pram āṇas may be contradicted by an intuitive insight—might seem strange to the readers. Therefore, before concluding this section, let me make a few remarks about the concept of “intuition” vis-à-vis pram āṇas in Advaita Vedānta. Intuition To capture the concept of “intuition” in Advaita Vedānta, one will have to contend not with one but with four senses of this concept. To begin with, the Sanskrit “aparok ṣajñ āna” is usually translated as “intuition”; it stands for a knowledge, which is immediate, i.e., a knowledge not mediated by conceptual thinking, as well as for a “knowledge by identity” in which the familiar distinction between the subject and the object is overcome. 1 We have already seen in the discussion of perception (pratyak ṣa) that it is the knowledge, within the reach of everyone, i.e., within the bounds of ordinary experience, which gives some inkling of what an intuitive knowledge by identity must look like. The perceived thing stands before me when I perceive it; I am in touch with it as it were; in Kant’s language, it is “given” to me, and I do not go through a conceptual process of thinking to reach it, though it is not unmediated. A mental process occurs, and the perceptual cognition is the result of that process (Leistung or an “accomplishment” in Husserl’s language). Ved ānta Paribh āṣā describes this process as the “going out” of the inner sense, assuming the form of the object, and achieving an identifcation with the object. In the cognitive process pertaining to the perception of an external object, the object is cognized via its association with the subject-consciousness. A modifcation of the inner sense (antaḥkara ṇavṛtti) effects such an association. The result is a cognition founded upon an identification, but not on an identity brought by a “going out” and assuming the form of the object. So, in the strict sense, the cognition is not immediate, though it seems immediate. Instrumentality of the inner sense is required to establish its connection 302 T H E V E DĀ N TA D A R ŚA NA 2 3 with the object. Hence, its intuitional character is a pretense. Concepts are not involved; the language has no role to play, the non-conceptuality is not yet immediacy. Perception’s ability to result in a cognitive accomplishment is because the v ṛtti or mental modifcation itself is known immediately without the intervention of another process. An object, say, a pitcher, is perceived through the v ṛtti (mental mode), but the v ṛtti itself is known without the mediation of another such v ṛtti if we are to avoid infnite regress. This indeed is the case. The v ṛtti is immediately present to pure consciousness as it occurs. Here there is immediacy, no mediacy (neither by another v ṛtti nor by any kind of conceptual thinking), no process is involved. But it is not a knowledge by identity; the pure consciousness and v ṛtti are not one nor can they taken to be one. The Advaitins call it “sāk ṣī-pratyak ṣa” or “witness-perception,” i.e., the immediate perception of mental modifcation.73 The witness-consciousness does nothing; it manifests the other. In this case, it manifests non-actionally (i.e., by doing nothing) whatever other comes before it. But this other is not an external object (which the witness-consciousness cannot without mediation manifest) but an other which is inner or mental. The manifestation of the v ṛtti is not an accomplishment, for its very nature a present to witness-consciousness. This cognition, if we call it “intuition,” is immediate, but it is not the result of a process by which the otherness is overcome; the otherness remains. The Advaita Vedānta entertains the possibility of working toward another experience which may be called “intuition.” In this case, one begins with “hearing” (śrava ṇa) the texts of the Upaniṣads (taught by a qualifed instructor), then one refects (manana) on the truths learnt, and, fnally, contemplates (nididhyāsana) on them. This contemplation culminates in an intuitive realization of those truths which amount to intuitively knowing who he is, what is the nature of his self, and experiencing the identity of the ātman and the brahman. With this, the fnal veil of ignorance is removed, and the self, eternally self-luminous, shines in its own light. The question may be asked: Is this intuition, i.e., the knowledge of the identity of the self and the brahman mediated by a mental mode? In fact, the Advaitins speak of it as the fnal mental modifcation. It is mediated by an impartite vṛtti (akha ṇd āk āravṛtti);74 so, it is not immediate and falls short of being an intuition in the strictest sense. But the question remains: Is the culminating stage, in which the self shines by its own light, an intuition? Again, it is not my knowledge, not knowledge by the subject who has reached this point. Who, then, is intuiting? And, what does one intuit? The pure self is not an object of knowledge. It is eternally self-luminous, and is so now, only the veil of ignorance is lifted. Again, strictly speaking, it is not an intuition by some knower. In other words, it is not as if a knower intuitively knows something other than itself. 303 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T 4 Let us leave aside the process of progressing toward a goal for the time being, it is worth remembering that consciousness is ever self-luminous (svaya ṃprak āśa). It apprehends itself by identity, without being an object of any cognition. We may at best call this aspect of consciousness an intuition of its own nature, immediately and as identical with itself. Consciousness precisely is this intuition of itself. This alone, of all the four cases, is intuition in the strongest sense: Intuition always by itself, of itself and always. I hope the above discussion provides my readers some insights into the role of intuition vis-à-vis pram āṇas, which belong to the domain of avidyā. The pram āṇas are not self-luminous, but they leave us at the door of the self-luminous consciousness, so to speak. They are important as they help us understand as well as transcend empiricality and lead us to an immediate understanding of the self by destroying avidyā, but in the process of destroying avidyā, they destroy themselves. Only the self-luminous consciousness remains, which was always there. To sum up, logic and intuitive experience are inseparably intertwined; they are two aspects of the same cognitive process. The pram āṇas as a system of logic, whose fnal basis is “consciousness,” is the “witness” and the “ judge” of all cognitive claims. The pram āṇas lead to an intuitive experience, where they have completely fulflled their role and cease to be. Reason, in other words, is transcended by an intuitive experience, which is the goal of all rational thinking. Thus, the standard Western dichotomy between reason and intuition collapses and both (reason and intuition) together form an integrated process of acquisition, validation, and justifcation of knowledge. Concluding Ref lections Before concluding this section on Advaita, I would make a few remarks about the relation between knowledge and ignorance in Advaita Vedānta. The two, knowledge and ignorance (as the Upaniṣads repeatedly assert), are opposed to each other.75 Śa ṃ kara, following the Upaniṣads, also reiterates that the two are opposed to each other as light and darkness. Knowledge removes ignorance. Knowledge is intrinsically desirable; ignorance and its consequences are what we in fact desire. Though the opposition between knowledge and ignorance, certifed by ordinary experience, is a well-established doctrine of Vedānta philosophy (also Buddhism), the Upaniṣads sometime surprise us by bringing them together in a manner that goes against the verdict of experience and seems counter-intuitive. For example, the Īśā text states, “Those who worship avidyā enter into darkness and those who are engaged in vidyā enter into still greater darkness … Those who know both vidyā and avidyā together overcome death by avidyā and reach immortality by vidyā.”76 Clearly this text emphasizes the necessity of knowing both vidyā and avidyā for attaining 304 T H E V E DĀ N TA D A R ŚA NA immortality through knowledge. What, then, does this text signify? These verses reinforce the dichotomy between work and knowledge and assert that those who pursue one to the exclusion of the other remain ignorant. Śa ṃ kara in his interpretation of the above states that “avidyā” in this context means action, i.e., the performance of the Vedic rituals and “vidyā” signifes knowledge and thought of the deities.77 The performance of rites and meditation on the deities helps one attain immortality, which is not mok ṣa or becoming identical with the brahman. Clearly these meanings are one-sided, so the question arises: Is there any other way of reconciling the text with the commonly acceptable meanings of the words? One way is to recall Plato’s thesis in the Republic: when the prisoner comes out of the cave and sees the light, his eyes are blinded and dazzled. It is imperative that he sees both the original and the copies, so that he may begin to see the truth. In other words, knowledge of the one must be combined with the knowledge of the many. Performing the ritualistic actions with the vision shrouded by ignorance may lead one to pass from this world to the higher worlds, which is not mok ṣa. Likewise, mere knowledge of the one to the utter exclusion of the experience of the world is not yet the highest knowledge. One must know both ignorance as ignorance and knowledge as knowledge. Is the Īśā saying something like Plato? I leave this question for the readers to pursue. It is possible to suggest that there are different levels of avidyā, and that to attain vidyā, one must go through the lower levels to reach the highest. In that case, one may want to maintain that avidyā is the pathway to mok ṣa or vidyā, even if the path lies within the domain of avidyā. Thus, the initial opposition between vidyā and avidyā is softened, because all entry into knowledge must be through ignorance. But, at the same time, there is a “leap,” a “ jump” from the one domain to the other, a total transcendence, a discontinuity. III Viśiṣtādvaita After Śa ṃ kara, the name that is most famous among philosophers of the Vedānta school is that of R āmānuja. Born 200 years after Śa ṃ kara, R āmānuja takes issue with Śa ṃ kara’s conceptions of the brahman, the status of the world, avidyā, and argues that both the brahman and the world rooted in the brahman are real, and in knowing the brahman we move from the partial to the complete. Using the principles of dharmabh ūtajñ āna or attributive consciousness, apṛthaksiddhi or inseparability, and sām ān ādhikar ṇya or the principle of coordination, R āmānuja establishes his own version of non-dualism called “Viśiṣt ādvaita” or “qualifed non-dualism.” R āmānuja remains one of the most infuential interpreters of a theistic variety of Vedānta. As a young man, he stayed in the company of such poet saints as Yamunā, Mahāpurāṇā s, and Goṣṭhipū r ṇa who exercised a profound infuence on him. These poet saints of South India were known as “Ālvārs.” The term “ālvar” etymologically means “one who has attained a mystic intuitive 305 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T knowledge of God.” These poet saints upheld a theistic interpretation of the Upaniṣads, the interpretation that shaped R āmānuja’s philosophical outlook. R āmānuja worshipped the god Viṣṇu and had many Viṣṇu temples and ma ṭhas built. The catholic spirit of his religion made it possible for him to acquire many devoted scholars, who carried on his religion and philosophy for centuries to come. R āmānuja died in 1137. R āmānuja’s philosophy is a creative and constructive effort to systematize the teachings of the Upaniṣads, the G īt ā, and the Brahmas ūtras. One of R āmānuja’s primary contributions lies in reconciling the extremes of monism and theism, while providing a formidable challenge to Śa ṃ kara’s Advaita Vedānta. If for Śa ṃ kara reality or the brahman is pure consciousness, pure existence, and pure bliss, on which individual consciousness (“I” and “mine”), the world, etc., are superimposed due to ignorance, R āmānuja takes brahman to be the God of religion, an all-inclusive being. R āmānuja, like Śa ṃ kara, believes that brahman is the only reality. But whereas Śa ṃ kara’s non-dualism takes the world and the God to be appearances, R āmānuja’s non-dualism takes them to be real, and in so believing satisfes the religious yearning of fnite individuals for a supreme person. Fundamental Postulates 1 There is no distinction between the nirgu ṇa and the sagu ṇa brahman or Īśvara (God). The brahman is the same as the god of theism. 2 Īśvara or brahman is existence, consciousness, bliss, knowledge, and truth. 3 The world rooted in the brahman is as real as the brahman. 4 Both matter and selves are eternal. 5 The brahman is identity-in-difference. 6 The brahman contains parts. The brahman is an organic unity of cit (conscious) and acit (unconscious). 7 Souls and matter, though real, are dependent on the brahman. 8 Ignorance is the root cause of our bondage. 9 Freedom from ignorance is possible through devotion. 10 Mok ṣa is sought through work and knowledge. 11 Constant meditation on God as the dearest object of love is required. 12 Mok ṣa is attained by God’s mercy. R āmānuja begins by asking the basic Upaniṣadic question: “what is that by knowing which everything else is known?”78 The answer is: The “brahman.” The brahman is knowable; he is realizable. Let us see what R āmānuja has to say about this important concept. 306 T H E V E DĀ N TA D A R ŚA NA Brahman At the outset of his philosophy, R āmānuja informs us that all knowledge necessarily involves discrimination and differentiation; it is impossible to know an object in its undifferentiated form.79 Knowledge is the affrmation of reality and every negation presupposes affrmation. The knowable is known as characterized in some form or the other by some specifc attributes. R āmānuja refuses to divorce the manifold from the one; his unity contains within itself the diversity. Since knowledge always involves distinctions, both pure identity and pure difference are not real. He concurs with Śa ṃ kara that the brahman is real. Being the all-inclusive totality of beings, the brahman is the whole which contains two parts: Consciousness or cit and matter or acit. Thus, the brahman is cit-acit-granthī, “a knot of consciousness and matter.” Both fnite centers of consciousness and the material nature, belonging to the brahman, are in it, and as belonging to the brahman, they are ultimately real. The brahman is an organic unity characterized by difference. R āmānuja recognizes as real three factors: The brahman or God, soul, and matter. Though equally real, the last two are completely dependent on the frst.80 In this metaphysical theory, the category of substance (dravya) predominates. One substance, which is a part of another, functions as the latter’s qualifying attribute. The human individual consists of two substances: A body and the soul. The two, being parts of a whole, are inseparably connected with each other.81 Perhaps, the most original aspect of R āmānuja’s philosophy is the rejection of the principle that to be real means to be independent. Though the soul and matter in themselves are substances, in relation to brahman they are his attributes. They are brahman’s body; he is their soul. R āmānuja’s notion of apṛthaksiddhi or inseparability explains this relation.82 This relation of inseparability obtains between a substance and its qualities; it may also be found between two substances. Just as qualities are real and cannot exist apart from the substances in which they subsist; similarly, matter and soul are parts of the brahman and cannot exist without the brahman. The soul of a human being, though different from his body, controls and guides his body; likewise, the brahman, though different from the matter and souls, directs and sustains them. To put it differently, the brahman is like a person and the various selves and material objects constitute his body. Thus, R āmānuja’s brahman is not an unqualifed identity; it is identity-in-difference, an organic unity, or better yet, an organic union in which one part predominates and controls the other part.83 The part and the whole then become a prototype of the large ontological relation. Body and soul are related with this sort of inseparability as much in the case of human individuals as in the case of the brahman. Just as knowledge is substance-attribute, similarly the self (cit) is itself a substance as well as a quality of the being or the brahman. The negative way of indicating the relation emphasizes the identity of being and its attributes, and at the same time retains the conception of relation in the integrity of being by rejecting absolute oneness (identity) which one fnds in the Advaita Vedānta of 307 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T Śa ṃ kara. Thus, as the logical subject, the cit is a mode (prak āra) of the brahman, but as an ethical subject, it is a monad which has its own intrinsic nature. Thus, whereas for Śa ṃ kara, the brahman as pure intelligence is devoid of any distinctions, pure identity without any difference (nirgu ṇa), R āmānuja’s brahman is identity-in-difference. When the Upaniṣads describe the brahman as devoid of qualities, they mean that the brahman does not have any negative qualities, not that it does not have any qualities whatsoever. It possesses many characteristics (sagu ṇa). Existence, consciousness, bliss, knowledge, and truth are some of his attributes. These attributes are responsible for his determinate nature. The brahman, for R āmānuja, is not different from the personal God of theism. But it includes all differences between conscious individuals and the material world. The fundamental principle of thinking then becomes identity-in-difference rather than pure identity. Everything is real, but only as included in the one reality; the totality is the supreme person, the puru ṣottama, who is all-knowing, all-powerful, blissful, and infnite. However, when considered as independent of, and falling outside of the totality, all differences are mere appearances. The Brahman and the World R āmānuja argues that the brahman is real and the world rooted in the brahman is also real. He takes the Upaniṣadic account of creation literally: The omnipotent God creates the world out of himself. During dissolution, God remains as the cause with subtle matter and unembodied souls forming his body. This is the causal state of the brahman. The entire universe remains in a latent and undifferentiated state. God’s will impels this undifferentiated subtle matter to be transformed into gross and unembodied souls into embodied ones according to their karmas. This is the effect state of the brahman. Creation, for R āmānuja, actually takes place, and the world is as real as the brahman itself. Accordingly, R āmānuja holds that such Upaniṣadic texts as “there is no multiplicity here” (“neha n ān ā asti kiñcana”) do not really deny the multiplicity of objects, of names and forms, but rather assert that these objects do not have any existence apart from the brahman. It is indeed true, concedes R āmānuja, that some Upaniṣadic texts articulate the brahman as wielder of a magical power (m āyā); however, m āyā, argues R āmānuja, is a unique power of God by which God creates the wonderful world of objects. He vehemently criticizes Śa ṃ kara’s theory of the falsity of the world as a creation of m āyā. The created world of the brahman, for R āmānuja, is as wonderful as the brahman itself. There is, according to R āmānuja, no object which is neither sat nor asat (as Śa ṃ kara argues). All things are real or sat. Knowledge corresponds to its object. The existent alone is cognized (satkhyāti). Even when I mistake a rope for a snake, what I see is real (not the Naiyāyika’s elsewhere-existent thing). Because of darkness, etc., I do not perceive everything that is there. The longish shape, size, color, etc., that I see are all there, but the fbrous texture, etc., 308 T H E V E DĀ N TA D A R ŚA NA I do not see. R āmānuja uses the doctrine of quintuplication to substantiate his theory, which holds that from a metaphysical perspective everything involves everything. Some particles of silver are present in the shell. When the shell is mistaken for silver, silver is there in a miniscule form. Not all illusions, however, can be explained in this manner. A person’s perception of a white conch as yellow requires a different explanation. How do we account for the yellowness of the conch in such cases? R āmānuja maintains that a person with a jaundiced eye, perceiving a white conch as yellow, transmits to the conch the yellowness of the bile through the rays of the eyes, and as a result the new color is imposed on the conch and its natural whiteness is obscured. Hence, there is no subjective element in error. Things perceived in dreams are created by God for the dreamers so that they may enjoy fruits of their past actions. So, knowledge is of the given, and agreement extends from the “what” (exists) to the “that” (knowledge corresponding to the content of a real object). Error is only partial knowledge. A corollary of this thesis is that knowledge implies both the subject and the object.84 It is the subject that knows the object with the help of its essential attributes (dharmabh ūtajñ āna).85 All knowledge is characterized by attributes, and there is no knowledge devoid of attributes.86 Hence, R āmānuja’s theory is known as satkhyātivāda, which literally means “sat (existence) alone is cognized.” Applied to the relation between the brahman and the world, we can say, the world is real, but only a part of the totality that is the brahman. Error consists in mistaking the part to be an autonomous whole. Thus, correction of error is not a total negation (as Śa ṃ kara argues), but with additional knowledge, one knows more about that yonder objects than he did originally. R āmānuja rejects Śa ṃ kara’s theory of causality that only the cause is real, and all effects are false appearances. R āmānuja’s own theory comes rather close to Sāṁ khya satk āryavāda that there is a real causation, the effect being a real transformation of the cause. Finite individual souls and material nature are real transformations, so that even in the causal state, the brahman contains matter and souls within it. R āmānuja distinguishes between the body of the brahman and his soul on the analogy of fnite individuals. The body of the brahman consists of matter and fnite souls, and his soul is his infnite, all-knowing consciousness. The brahman thus is both the material and the effcient cause of the world and continues to be “the inner controller” of what he creates. There is no contradiction in saying that the same thing is both the material and effcient cause. The potter’s wheel, e.g., is the effcient cause of a pitcher, and the material cause of its own form and qualities. As both cit and acit, the brahman is the material cause, while as idea and will, he is the effcient cause. Finally, we must note that for R āmānuja, time is real, and is directly perceived as a quality of all perceived entities. Time is eternal in the sense that it is never destroyed. If someone were to ask, “how does the one contain the many?” R āmānuja in response would put forth the grammatical principle of sām ān ādhikar ṇya or the principle of coordination. With the help of this principle, R āmānuja rejects 309 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T the concepts of bheda (difference) and abheda (non-difference) and institutes the concept of vi śe ṣa (predication). Following this principle, R āmānuja argues that in all instances of predication what is predicated is not a bare identity but a substance that is characterized by different attributes. To explain this, let me turn to R āmānuja’s interpretation of the classic Upaniṣadic text, “So ‘yam Devadatta,” i.e., “this is that Devadatta,” which, for R āmānuja, is not an identity judgment as it is for Śa ṃ kara. R āmānuja argues that the words in a sentence with different meanings can denote the same thing. For example, Devadatta of the past and the Devadatta of the present cannot be entirely identical, because the person seen at the present and the person seen in the past are different, have different meanings, yet both refer to the same person. Similarly, unity and diversity, the one and the many, can co-exist and can be reconciled in a synthetic unity. Thus, with the help of this rule, R āmānuja, on the one hand, rejects the principle of abstract bare identity and, on the other hand, institutes a principle of differentiation at the very center of identity. There is no need to deny the many; the many characterize the one. The Self, Bondage, and Liberation On R ā mā nuja’s theory, each individual self ( j īva) is a substantial reality, and a substance can serve as a quality of the whole of which it is a part. For example, a stick (da ṇḍa) is a substance, a thing; it also qualifes the person who carries it, and he is called a “da ṇḍin.” To the question, then, whether the individual selves have their own substantive being or are merely adjectival, R ā mā nuja’s says they are “both.” A fnite substance depends on the infnite whole, i.e., the brahman, and the brahman is qualifed by both cit and acit (citacitvi śi ṣta). Human beings, according to R āmānuja, have a real body as well as a soul. Given that the body is made of matter, it is fnite. The soul, however, exists eternally, though it is also a part of God. It is subtle, which allows it to penetrate unconscious substances. Consciousness is not an essence, but an eternal quality of the soul. The sense of “I” is not missing in the waking, dreaming, and dreamless sleep states. Waking up from deep sleep, one says “I slept well,” “I did not know anything,” which implies that one did not know any object. The soul remains conscious of itself as “I am” in all states. R āmānuja argues that the Bhagavad G īt ā also holds that God is a person, the supreme person, God refers to himself as an “I.” Both the individual souls and God are embodied. A brief review of R āmānuja’s concept of “body” or “śar īra” would provide further insights and help my readers understand this complicated sense of embodiment. Whereas the Naiyāyikas defne “body” as the locus or the support (āśraya) of effort, sense, and enjoyment, R āmānuja defnes “body” in terms of “subservience to the spirit.” The body depends on the will of the spirit for its movement. There never was or will be a time in which this relation between the body and the 310 T H E V E DĀ N TA D A R ŚA NA soul did not exist. It is a necessary relation of “inseparability.” Even before creation God’s body existed but only in its original state, i.e., prak ṛti, the stuff that undergoes change. Apart from his body, God is unchanging. Thus, God’s being has both a spiritual and a material part, though prak ṛti originally, i.e., prior to the world creation, as belonging to God’s body, was pure (“pure” in the sense of being only of the sattva quality). In sa ṃsāra (the embodied existence), the soul wrongly identifes itself with the body on account of karmas (past deeds) and ignorance. Though the soul is infnitely small, it illumines every part of the body in which it is housed. Accordingly, R ā mā nuja distinguishes between two meanings of the “I”: In one sense, the “I” means the aha ṁk āra or egoism, which is to be overcome and conquered, while, in another sense, the “I” means “the knower.” The knower self refers to himself as the “I” with a soul. There are innumerable individual souls; they are qualitatively alike but differ in number. In this respect, R ā mā nuja’s conception of the individual soul corresponds to that of Leibniz, who advocates a qualitative monism and quantitative pluralism of monads.87 Mok ṣa, according to R āmānuja, cannot be brought about by mere knowledge. Work, knowledge, and devotion to God are needed to attain freedom from ignorance, karma, and embodied existence. “Work,” R āmānuja holds, means different rites and rituals prescribed in the Vedas according to one’s caste and situation in life. These duties must be performed without any desire for the rewards. Disinterested performance of one’s duties is the key here. Such a performance destroys the accumulative effects of actions. The study of the M īmāṁsā texts (i.e., the texts that explain how the rites and ceremonies should be performed) is necessary to ensure the right performance of duties. Accordingly, R āmānuja makes the study of M īmāṁsā a necessary prerequisite to the study of Vedānta. The study of the M īmāṁsā texts and the correct performance of one’s duties lead one to realize that sacrifcial rites and rituals do not lead to freedom from one’s embodied existence; hence, the necessity of the knowledge of Vedānta, which aids in developing one’s intellectual convictions about the nature of God, the external world, and one’s own self. Such a knowledge reveals to the seeker of wisdom that God is the creator, sustainer, and destroyer of the world, and that the soul is a part of God and is controlled by him. Study and refection further reveal to the aspirant that neither the correct performance of one’s duties nor an intellectual knowledge of the real nature of God can lead to freedom from embodiment. Such a freedom can only be attained by the free, loving grace of God. Accordingly, one should dedicate oneself to the service of God. R āmānuja, in short, unlike Śa ṃ kara, maintains that the path of devotion leads one to freedom. Knowledge, combined with bhakti, can destroy ignorance, but mok ṣa, in the long run, is brought about not by the individuals’ own efforts but by God’s grace (dayā). One needs to give up a false sense of independence, i.e., pride, and seek his mercy by completely surrendering himself to God, which is “prapatti.” 311 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T Thus, what brings about mok ṣa is not the aspirant’s self-surrender, but God’s own infnite compassion for the devotee. The followers of R āmānuja differ as to the extent of activity and passivity involved in the process. Some emphasize more initiative on the part of the aspirant, others more passivity. Some prefer to use the analogy of a monkey’s little one who actively clings to the mother’s body: Still others prefer the analogy of the kitten’s complete passivity such that the mother cat just picks him up at the neck. In any case, the steps in the process are: (1) Knowledge of God’s infnitely perfect nature, (2) constant meditation (dhyāna) on him, (3) resulting in uninterrupted thought of God culminating in immediately experiencing him, (4) one’s completely surrendering oneself to him, (5) leading to God’s infnite mercy that destroys one’s karma, ignorance, and bondage. To sum up, the path of devotion, for R āmānuja, involves constant meditation, prayer, and devotion to God. Meditation on God as the object of love accompanied by the performance of daily rites and rituals removes one’s ignorance and destroys past karmas. The soul is liberated; it is not reborn. It shines in its pristine purity. Unlike Śa ṃ kara, the soul according to R āmānuja does not become identical with God; it becomes similar to God. Mok ṣa is a state in which the individual self becomes pure and perfected and enjoys God’s fellowship eternally. The last vestige of egoism is removed. But all this, i.e., the highest goal, cannot be achieved simply by one’s own effort, or even by knowledge alone. R āmānuja rejects the notion of complete identity between the brahman or God and fnite selves. Individual selves are fnite and cannot be identical to God in every respect. God not only pervades but controls the entire universe. As the existence of a part is inseparable from the whole, and that of a quality is inseparable from the substance in which it inheres; similarly, the existence of a fnite self is inseparable from God. Accordingly, his interpretation of the Upani ṣadic statement “you are that” is very different from that of Śa ṃ kara. For Śa ṃ kara, the relation between “that” and “you” is one of complete identity. R ā mā nuja, however, maintains that in the Upaniṣadic statement under consideration, “that” refers to God, the omniscient, omnipotent, all-loving, creator of the world, and “you” refers to God existing in the form of I-consciousness, the fnite human consciousness. The identity in this context should be construed to mean an identity between God with certain qualifcations and the individual soul with certain other qualifcations. To put it differently, God and fnite selves are the same substance, although they possess different qualities, which explains the name of the system Vi śiṣt ā dvaita, i.e., “qualifed identity” or “identity with certain qualifcations.” Thus, whereas in the non-dualistic Ved ā nta of Śa ṃ kara liberation is realization of the non-difference between the brahman and the liberated self, in the qualifed non-dualistic Vedānta of R āmānuja, the liberated self lives in eternal communion with God. Before concluding this chapter, I will briefy sum up the important differences between Śa ṃ kara and R āmānuja. 312 T H E V E DĀ N TA D A R ŚA NA IV Śaṃkara and R ām ānuja Interpretation of the Upaniṣadic Texts We already know that there are two descriptions of the brahman in the Upaniṣads: The positive and the negative. To recapitulate, we fnd the texts that describe the brahman as being the origin and the sustainer of all beings and as that into which they all return. The Upaniṣads also assert “none of this is the brahman.” These texts throughout the centuries have posed problems for commentators and they have tried to reconcile these seemingly inconsistent statements. For Śa ṃ kara, affrmative sentences are only provisional, only to be denied eventually, because the negative sentences state the higher truth, articulated as brahman is none of these. The world and the fnite individuals are not real; the brahman alone is real. R āmānuja argues what is negated is the presumed autonomous reality of fnite things, but all of them have their reality as parts of one all-comprehensive totality, i.e., brahman. The Brahman as Indeterminate and Determinate The brahman, for Śa ṃ kara, timeless, unconditioned, undifferentiated, is that about which nothing can be affrmed. The brahman is nirgu ṇa; it does not possess any qualities. It is indeterminate. It is that state of being where all subject/object distinction is obliterated. The brahman defes all positive determinations. Sagu ṇa brahman is the brahman as interpreted and affrmed from a limited, empirical standpoint. It is described as saccid ānanda, i.e., as existence (sat), consciousness (cit), and bliss (ānanda). Descriptions belong to the perceptual-conceptual realm of human experiences and, hence, limited in scope. According to R āmānuja, the brahman is sagu ṇa; it is not a distinctionless reality. R āmānuja argues that when Upaniṣads describe the brahman as devoid of qualities, they mean that the brahman does not have any negative qualities, not that it does not have any qualities whatsoever. It possesses a number of good qualities (sagu ṇa). These attributes are responsible for its determinate nature. The brahman, for R āmānuja, is not different from the personal God of theism. The brahman is an organic unity, a unity which is characterized by diversity. R āmānuja recognizes as real three factors: The brahman or God, soul, and matter. Though equally real, the last two are absolutely dependent on the frst. Consciousness as Self-Manifesting vs. Intentional On Śa ṃ kara’s theory, pure consciousness is self-manifesting, and it is not a possible object of any pram āṇa. In other words, consciousness is non-intentional. R āmānuja considers this to be totally mistaken. Consciousness is always of an object, and it is self-manifesting only when it is directed toward an object. When I apprehend a thing in perception now, then only, i.e., at that very moment, my perceptual consciousness manifests itself to me. Subsequently, i.e., 313 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T at other moments, that consciousness does not manifest itself to me, nor does it ever manifest itself to other selves. So, on Rāmānuja’s theory, consciousness manifests itself to its own subject; at the moment, it also manifests an object. Śaṃkara’s self-manifesting pure consciousness is a fgment of imagination. In modern Western philosophical language, Rāmānuja ties intentionality and refexivity to consciousness. Without intentionality, consciousness cannot be refexive. Brahman as Sat, Cit, and Ānanda Śa ṃ kara regards brahman as pure bliss. Its nature is bliss or ānanda, just as it is also pure knowledge. R āmānuja argues that “bliss” and “knowledge” are qualities of the brahman. It is absurd to take them to be identical with the brahman. If that were the case, such texts as “brahman is sat, cit, and ānanda” would be tautologies, and the words “sat,” “cit,” and “ānanda” synonymous. A string of synonymous words does not make a sentence. Each of the constituent terms must stand for a quality belonging to the brahman. Brahman is a qualifed whole which contains within its being the world and fnite selves. Status of Avidyā or Ignorance For Śa ṃ kara, the silver and the snake that appear in illusory perceptions are neither real (sat) nor unreal (asat), but indescribable either as sat or asat. This new category of entity is presented in experience but is subsequently negated in the same locus in which it was presented. Such an object is called “mithyā” or false. Ignorance is beginningless having two functions: Concealment of the real and the projection of the mithyā upon it. The world and the fnite things are mithyā in this sense. R āmānuja launches a severe critique of the Śa ṃ kara’s theory of error (and of the associated theory of ignorance). Of the various objections that R āmānuja raises against Śa ṃ kara’s account, I will mention only four. 1 2 R āmānuja asks: What is the locus or āśraya of ignorance? To put it differently, where does ignorance reside? It cannot reside in the fnite individual, because the individual self is a product of ignorance. The brahman cannot be its locus either, because the brahman is of the nature of knowledge, which destroys ignorance. Ignorance and knowledge being contradictories cannot have the same locus. Thus, it is impossible to determine the locus of ignorance. Ignorance, argues Śa ṃ kara, veils the self-luminous brahman. R āmānuja asks: what is meant by the “concealment of luminosity”? It may mean either the obstruction in the origination of the luminosity or the destruction of the luminosity. R āmānuja argues that the luminosity is not produced, so the question of its obstruction does not arise. Thus, the concealment of luminosity can only mean the destruction of the brahman’s luminosity, which would amount to the destruction of its essential nature. 314 T H E V E DĀ N TA D A R ŚA NA 3 4 R āmānuja argues that the Advaita self-luminous consciousness becomes conscious of the world of objects on account of some defect, i.e., avidyā. What is the exact nature of avidyā as an imperfection or defect in cit? Is this defect real or not real? Śa ṃ kara argues that it is not real; it explains our errors. It explains not only such illusions as rope-snake but also the appearance of the world. If it is said that the brahman itself may be regarded as having the defect, then there would be no need of postulating avidyā, because then the brahman itself would be regarded as the cause of the world, but in that case, there could not be any release for the fnite individual, because the brahman being eternal, its defect would also be eternal. R āmānuja states that it is impossible to defne ignorance. Śa ṃ kara argues that ignorance is indescribable, because it is neither sat, nor asat, nor both sat and asat at the same time. R āmānuja argues that “sat” and “asat” are contradictories; there is no third possibility. Thus, to say that the false object is neither sat nor asat is to violate a basic principle of logic. R āmānuja concludes that ignorance cannot be defned. V Concluding Remarks The above discussion will give my readers an idea of the kinds of objections R āmā nuja raised against Śa ṃ kara’s theory of ignorance. The followers of Śa ṃ kara have systematically refuted these objections to substantiate their own theory of ignorance. Irrespective of which account one fnds plausible, there is no doubt that R ā mā nuja’s critique of Śa ṃ kara has left its indelible mark on the Advaita philosophy. R ā mā nuja avoids both monism and dualism and provides his followers with a spiritual experience of the brahman or God that harmonizes the demands of reason and immediate experience, philosophy, and religion. Traditionally, a person must belong to one of the three higher castes to pursue the path of mok ṣa. R ā mā nuja recognized that irrespective of caste and rank, one may follow the spiritual path to attain union with God. This accommodating spirit made it possible for Viśi ṣt ā dvaita to acquire many followers and make it popular in India through the ages. It uplifted the lower castes, and therein lies one of its most important contributions. Study Questions 1. Explain clearly the Advaita conception of the brahman. Discuss the differences between the nirgu ṇa and the sagu ṇa brahman. 2. Discuss superimposition. What is the signifcance of this notion for Śa ṃ kara’s philosophy? 3. Discuss the levels of reality in Advaita Vedānta. What is m āyā? Discuss the three senses of m āyā. Can the Advaitin analysis of the relation between the brahman and the world be vindicated? 315 S Y ST E M S W I T H GL OB A L I M PAC T 4. Śa ṃ kara argues that the fnite self and the brahman are non-different. Critically discuss this thesis. Does it make sense to you? Give reasons for your position. How does one attain mok ṣa in Advaita Vedānta? 5. Discuss the six sources of knowledge in Advaita Vedānta. 6. Discuss R āmānuja’s conception of the brahman. What are some of the differences between the Śa ṃ kara and R āmānuja’s conceptions of the brahman? 7. Compare and contrast the status of the world in Advaita and Viśiṣṭādvaita philosophies. 8. How does one attain mok ṣa in Viśiṣṭādvaita? Outline the important differences between the Advaita and the Viśiṣṭādvaita conceptions of mok ṣa. 9. Read the passage carefully, and answer the questions asked. Conversation between Larry (Follower of Nāgārjuna’s Mādhyamika Buddhism) and Sajjan (Follower of Śaṃkara’s Advaita Vedānta) Suppose Larry argues, “I also believe that there are different levels of truth, e.g., the conventional (sa ṃsāra) and the transcendental truth (param ārtha satt ā). Like you, I also believe that phenomena that are experienced are not permanent; dukkha and sa ṃsāra are conventional truths, and their cessation is the noumenal truth. For us, nirvāṇa and sa ṃsāra are not two ontologically distinct levels, but one reality viewed from two different perspectives; for you, the world is empirically real grounded in the reality of the brahman. Finally, I like an Advaitin, believe that that negation is higher than affrmation, and believe that that higher truth is grasped in prajñ ā (direct intuition). I am therefore a good Advaitin as well as a good Mādhyamakan.” • • • Discuss some of the important differences between Nāgārjuna and Śa ṃ kara. Do you fnd Larry’s arguments convincing? If yes, why yes? If not, why not? Which philosophy appeals to you more, Nāgārjuna or Śa ṃ kara? Give reasons for your answer. Suggested Readings For translations of the Ved ānta S ūtras from the Advaita perspective, see George Thibaut (tr.), The Ved ānta-S ūtras with the Commentary of Śa ṅkarācārya, Vols. 34 & 38 of the Sacred Books of the East (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1890, 1896); Eliot A. Deutsch, Advaita Ved ānta: A Philosophical Reconstruction (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1968) is an excellent introduction available on Advaita; for Advaita epistemology, see Swāmī Mādhavānanda (tr.), Ved ānta Paribh āṣā (Mayavati: Advaita Ashrama, 1983). 316 T H E V E DĀ N TA D A R ŚA NA For translations of the Ved ānta S ūtras from the Viśiṣṭādvaita perspective, see George Thibaut (tr.), The Ved ānta-S ūtras with the Commentary of R ām ānuja, Sacred Books of the East (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1904), Vol. 48; John Carman, The Theolog y of R ām ānuja: An Essay in Interreligious Understanding (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1974), is best available introduction on R āmānuja; for epistemology, see K. C. Varadachari, R ām ānuja’s Theory of Knowledge (Triupati: Devasthanama Press, 1943). 317 Part VII THE BHAGAVAD G Ī TĀ 15 THE BH AGAVA D G Ī T Ā I Introduction The Bhagavad G īt ā has acquired a place of incomparable honor in the religious and philosophical literatures of India. It is not an exaggeration to say that it is one of the most well-known and widely read Hindu texts. The fact that Śa ṃ kara and R āmānuja, two important classical commentators of the Vedānta school, regarded the G īt ā as one of the three primary sources of the Vedānta tradition offers eloquent testimony to its importance. Scholars are not unanimous regarding the dates of the G īt ā. Tradition, however, maintains that it was authored somewhere between the third and the frst centuries BCE, and is taken to be a part of the epic Mah ābh ārata. Given that it contains numerous references to the views of the Buddha, it is safe to say that the G īt ā is post-Buddhistic. It expresses the quintessence of the Vedas and the Upaniṣads. Many classical and modern scholars in the East and the West alike have translated and commented on it: Wilhelm von Humbolt characterizes it as the most beautiful and truly philosophical poem; Mahatma Gandhi calls it the guide and solace of his life; and the poet T. S. Eliot considered it one of the two most important philosophical poems in world literature, the other being Dante’s Divine Comedy. Thus, it is not surprising that the G īt ā has been translated into all the major languages of the world, and there are close to one hundred translations of it in English. One of the G īt ā’s unique features, as a philosophical poem, is that it is set in the background of a battlefeld on which one of the India’s fercest internecine battles was fought. Philosophical discourses are given in academies or āśramas, but the G īt ā was delivered by its teacher on the battlefeld on the eve of the commencement of the battle. The pupil to whom the discourse was delivered was not a student, not a contemplative mind inquiring into the truth of things, but rather the warrior who had already earned the fame of the country’s greatest archer. The occasion for this discourse was not a theoretical inquiry of the pupil, but rather Arjuna’s state of practical indecision at which he had arrived. Should he fght in the battle and kill an innumerable number of people including the members of his own family and friends? This 321 T H E B H AG AVA D G Ī TĀ most unusual occasion provides the point of departure for an abstruse philosophical discourse. It is therefore not surprising that despite numerous metaphysical and religious chapters in the G īt ā, for many readers, for example, for Mahatma Gandhi, the central teaching of this very complex text lies in what it teaches about karma yoga, the path of action. In the sixth century BCE, Gautama Buddha in his Noble Eightfold Path had already popularized the idea of a path. However, about the same time, Hinduism also had developed its own notion of alternate paths. Here, it is more important to recall the Hindu conception of the four goals of life, viz., (1) artha or material wealth and well-being, (2) k āma or erotic pleasure, (3) dharma or the pursuit of virtuous (ethical) life, and (4) mok ṣa or the ideal of freedom from the chains of karma and rebirth. These four goals were not ends which one ought to pursue, but rather ends which human beings in fact do pursue. There was possibly a hierarchical order among them; though there was no universal agreement about this hierarchy, they all agreed that mok ṣa is the highest and the ultimate good. The problematic aspect of the Bhagavad G īt ā is the relation between dharma and mok ṣa. The text of the G īt ā does not take up the other two of the four goals; let me therefore focus on the goals of dharma and mok ṣa to explain the paths discussed in the Bhagavad G īt ā. While the meaning of the word “dharma” is notoriously varied,1 for my present purposes, it would suffce to note that it stands for all those virtues and duties which determine a person’s relationship to himself/herself, to other persons, to society, to the gods, and to the universe as a whole. Our sources of the knowledge of dharma are the scriptures and the tradition. The world of dharma, therefore, is enormously complex, differentiated, and structured. Taking into view the ancient Hindu belief, which the G īt ā also articulates, all human beings are divided into four var ṇas 2 depending on a person’s aptitudes and abilities. These are the brahmins, i.e., priests and scholars; the k ṣatriyas or the warriors; the vai śyas, i.e., the businesspersons, farmers, and tradesmen; and the śūdras or those who serve the other three. Each var ṇa has a set of duties attached to it. The brahmins personify spiritual and intellectual wisdom which includes forgiveness, self-control, serenity, uprightness, etc.; the k ṣatriyas enforce the rules, and represent heroism, fortitude, political leadership; the vai śyas, the traders and the merchants, represent practical intelligence, adaptive skills; and the śudras serve the above three var ṇas. Dharma includes both virtues and duties of the members of each var ṇa, and those virtues and duties that are obligatory on each human being. Thus, it is the duty of a warrior to fght for a noble cause as against the forces of evil. The context of the Bhagavad G īt ā is constituted precisely by the relationship between the two parts of the world of dharma, viz., the dharma belonging to the specifc var ṇas and the dharma that is common to all human beings. The teaching on the face of it is intended to resolve a perceived contradiction between the two. I will quickly recapitulate this context. 322 T H E B H AG AVA D G Ī TĀ II The Historical Context and the Setting of the G ītā The very frst chapter of the G īt ā depicts Arjuna as a hero caught between the mandates of social code and the obligations to his family and friends. It describes the two armies on the eve of the battle; Arjuna is sitting on his chariot and K ṛṣṇa is acting as his charioteer. Arjuna sees his teachers, friends, uncles, etc., standing on the opposite side. He is overwhelmed and horror stricken with the thought of killing his friends and relatives. Arjuna’s dilemma is as follows: He belongs to the k ṣatriya var ṇa (warrior var ṇa), which dictates that he fghts in an impending righteous battle. His svadharma (dharma specifc to his var ṇa) requires that he fght, but his familial duties (dharmas) and obligations require that he protect his family members—creating a terrible confict. He is confused and not sure as to what he should do. He lays down his arms in frustration; he does not want to win the battle at the cost of killing his own friends, relatives, and teachers. However, if he does fght, he is sure to kill the members of his own family, including some of his teachers, who are lined up on the other side. So, he refuses to fght, and turns to his charioteer, his counselor, K ṛṣṇa (Arjuna was not aware of K ṛṣṇa’s real identity at the time that his charioteer is incarnation of the Lord Viṣṇu in human form) and informs him that he has decided not to fght. In Arjuna’s words3: I do not wish to kill them, though they are prepared to slay us, K ṛṣṇa …. (I.35) The sins of men who destroy the family, create disorder in society that undermines the eternal laws of caste and family duty. (I.43) The faw of pity afficts my entire being, and conficting sacred duties have bewildered my reason; I ask you to tell me decisively—which is better? I am your student, teach me for I have come to you [for instruction]. (II.7) Arjuna’s dilemma arises because the world of dharma is not a coherent whole; it is internally inconsistent. Hegel had drawn attention to a similar contradiction within the Greek ethos, whose resolution led to the rise of the modern world. Another person who saw a contradiction within the ethical was Kierkeggard, who discusses how Abraham’s sense of duty reached its limit when he was called upon by God to sacrifce his own son. Like Abraham, Arjuna was also confused and confounded and he was overtaken by fear and trembling. 323 T H E B H AG AVA D G Ī TĀ In order to understand K ṛṣṇa’s intervention at this point, one must remember that the two paths, viz., the path of action and that of knowledge, had already been advanced as paths to mok ṣa. There was a dichotomy between the path of action promoted by the Vedic religion (in which action was understood in the narrow sense of the ritualistic action, and involvement in the world and the community) and the path of knowledge which was Advaitic in inspiration (renunciation of worldly roles and duties). Arjuna had two solutions open to him to resolve this impossible situation: Either give up all obligations to the ideal of doing one’s duty and lead a life of action (pravṛtti) or live like a hermit and lead the life of a renunciant (nivṛtti). Not that Arjuna was inclined to follow the path of renunciation, but K ṛṣṇa took the opportunity to inform Arjuna that the path of renunciation was not meant for him, and that the adherence to this path would be wrong for him. The proponents of the path of knowledge “opposed” the path of action, because action is always performed with a desire for the results. According to a common psychological theory supported by most Indian philosophers with slight modifcations, it is the desire to achieve certain benefcial results and avoid certain unwelcome results so that one is motivated to do something. Such a desire leads to effort, and the effort, if successful, ends in the performance of action and the desired result follows. Often, possibly in all cases, whatever else may be desired, two consequences are intended: (1) Happiness or sukha, and (2) avoidance of unhappiness or dukkha. Some of these consequences may be achieved in this life, whereas some others in the future lives. Again, one might argue, as Gautama Buddha did, that even these results are necessarily relative, because happiness may be counted as unhappiness or pain when contrasted with possible but not achieved greater happiness or when happiness passes away. Thus, both happiness and pain are transitory, and in this sense reducible to pain. Hindu thinking did not follow this reduction of happiness to pain, but rather recognized, better yet emphasized, that the desire for happiness which motivates a life of action, be it this-worldly or the other-worldly, may lead to the promised heaven but not to release from the bondage of karma and rebirth. Desire perpetuates bondage. Thus, it seems that the path of action, the sort of the path advocated by Vedic ritualism, cannot be conducive to the attainment of mok ṣa. It is at this point that the G īt ā’s most famous and the original contribution to the Hindu thought lies. It lies in the thesis that the path of action can be an effective means to mok ṣa, only if actions are performed for duty without being motivated by desire, i.e., when actions are desireless. I will detail the concept of “desireless actions” (ni ṣk āma karmas) in the fourth section of this chapter. However, it is crucial to remember here that Arjuna was undecided about his duty as a warrior, not about attaining mok ṣa; the thematic of mok ṣa was introduced by K ṛṣṇa. Thus, while responding to Arjuna’s queries, K ṛṣṇa completely transforms Arjuna’s refusal to fght to the goal of mok ṣa and recommends that if Arjuna is to strive after mok ṣa, he should follow the path of the 324 T H E B H AG AVA D G Ī TĀ desireless action. In other words, in response to Arjuna’s query why he should fght, K ṛṣṇa very quickly moves to the question of “how” he should fght, i.e., with what attitude he should fght. This transformation of the problem, viz., Arjuna’s indecision into another problem, i.e., what is the best path to mok ṣa, is affected by K ṛṣṇa in several clever moves. K ṛṣṇa begins with why Arjuna should fght and gives many arguments to Arjuna in his attempt to persuade him to fght. He reminds Arjuna (1) that the ātman is immortal and (2) that he belongs to the warrior var ṇa, and it his duty to fght, and in the process K ṛṣṇa also appeals to his sense of self-esteem on various levels, emphasizing that if he gives up fghting, his friends and neighbors will look upon him as being a coward, and posterity will blame him for having shirked his duty. Let us listen to K ṛṣṇa. III Why Arjuna Should Fight? Arjuna begins (II.11ff.) with why Arjuna should fght. K ṛṣṇa initially helps Arjuna to resolve his dilemma from two standpoints: The unqualifed and the qualifed. From the unqualifed standpoint, K ṛṣṇa reminds Arjuna that the self is immortal, the body is going to be destroyed sooner or later; so, it is futile to mourn over the bodies killed in a battle. The soul, however, is immortal; it transcends birth and death. Let us listen to K ṛṣṇa: The Soul is Immortal He who believes that this self is a slayer, and he who believes that it is slain, both fail to understand; the self neither slays nor is slain. (II.19) The self is neither born, nor does it die, nor having been can it ever cease to be. It is unborn, eternal, permanent, and primeval, it is not slain when the body is slain. (II.20) The self that dwells in all beings is immortal in them all, O Arjuna, for the death of what cannot die, do not mourn. (II.30) K ṛṣṇa continues and informs Arjuna that just as a person abandons old clothes and wears the new ones; similarly, selves abandon old bodies and take up the new ones. No weapon can pierce this self; fre cannot burn it; water cannot drench it; and air cannot dry it. This self is eternal, unmoving, present in everything, unmanifested, unthinkable; so, Arjuna should not mourn death. For the one who is born, death is a certainty, and the dead for sure will be reborn. Arjuna should not mourn for what cannot be otherwise. Thus, 325 T H E B H AG AVA D G Ī TĀ continuing his understanding of the nature of the soul, K ṛṣṇa asks Arjuna not to grieve for the possible death of his opponents. You belong to the Warrior Var ṇa: It is your Duty to Fight From the qualifed perspective standpoint, K ṛṣṇa reminds Arjuna that since he (Arjuna) belongs to the warrior var ṇa, it is his duty to fght. In K ṛṣṇa’s words: [C]onsidering your own (sva = one’s own being or nature) duty as a soldier, you must not falter, there exists no greater good for a warrior than a battle of duty. (II.31) If you do not fght this righteous battle, then you will abandon your duty and will incur sin. (II.33) The great warriors will think that you fed from the battle on account of fear, and those who hold you in high esteem will despise you. (II.35) Many unspeakable words will be spoken by your enemies slandering your manhood, what could be more painful than this? (II.36) In short, K ṛṣṇa points out that all amicable means of settlement have failed, moral and spiritual values are at stake; thus, to establish truth and righteousness and restore the moral balance of society, it is the dharma of a soldier to fght in a righteous battle. In the G īt ā, “duty” (dharma) is taken in a broad sense in the context of its philosophical and religious foundations. Thus, doing his dharma, i.e., fghting in the battle, is the only right thing to do for Arjuna. K ṛṣṇa also argues that no one can completely give up a life of action, and that even if a person shuts off his outside senses, his mind will still be active and in that case his claim to have given up action would be a lie. Additionally, if action is unavoidable, then it is better to aim at renunciation while engaged in action, than the total renunciation of action. So, the question arose how could one act, do his duties, play his social roles, and yet be free within? K ṛṣṇa’s answer is to free oneself from the attachments to the “fruits of one’s actions,” while at the same time doing one’s duty. In short, though initially, K ṛṣṇa gives arguments to Arjuna to persuade him why he ought to fght, very soon in the second canto, K ṛṣṇa changes his tune and explains how Arjuna 326 T H E B H AG AVA D G Ī TĀ ought to fght, i.e., with what spirit Arjuna should to fght, and with this begins the teaching of karma yoga, the subject of the next section, and the focus of this chapter. IV How Arjuna ought to Fight? Karma Yoga (the Path of Action) K ṛṣṇa tells Arjuna to do his duty with a spirit of detachment without any desire to receive any benefts for himself. How Arjuna Ought to Fight? Action alone should be your concern never its fruits; the fruits of actions should not be your motive, nor attachment to inaction. (II.47) Perform action that is necessary; it (action) is more powerful than inaction…. (III.8) Therefore, always perform without attachment, any action that must be done, for in performing action with detachment, one achieves the highest. (III.19) Abandoning all attachments to the fruits of action, ever content, independent, he does not act [does not accumulate karmas] even when engaged in action. (IV.20) A karma yogi whose mind is disciplined, whose mind and senses are under control, who unites himself with the self of all, he is not contaminated though he works. (V.7) Treating pleasure and pain, gain and loss, success and defeat alike (sama), get ready to fght, you will not incur any sin [does not accumulate karmas]. (II.38) The verses translated above express the crux of the path of action outlined in the G īt ā. In terms of action, K ṛṣṇa asks Arjuna to perform actions without any desire for the fruits of the action for himself. It is this inner freedom from 327 T H E B H AG AVA D G Ī TĀ attachment, freedom from the desire for the fruits of actions, which in the fnal analysis is what matters, because giving up of actions is neither possible nor desirable. Hence, the well-known advice is: You have the obligation and the right to perform the recommended action, but you do not have the right either to enjoy or to bemoan the fruits thereof.4 In reading and re-reading the G īt ā for over fve decades, I am not sure how to understand this moral principle? K ṛṣṇ a repeatedly emphasizes that actions must be done from a sense of dharma without any desire to gain benefts. Desires and passions can lead a person astray, prompt a person to perform selfsh actions, while the performance of dharma without any attachment to its consequences purifes the self and leads to mok ṣa. It has been held by some scholars (e.g., German philosopher Hegel) that it is not possible to perform actions without any desire for the consequences of the actions. Is K ṛṣṇ a simply giving an impossible advice violating the principle that “ought” implies “can?” What is the meaning of “phala” (consequences)? K ṛṣṇa repeatedly asks Arjuna to remain non-attached (to consequences), exhorts him to perform his dharma, and asserts that the performance of duty without desires leads to mok ṣa. There are ample examples of this in Indian history. For example, kings Janaka and A ś vapati achieved mok ṣa by performing actions without any desire for results; such actions are inspiring and set an example for others to emulate. In giving this advice to Arjuna, K ṛṣṇ a also gives Arjuna his own example and informs him that he engages in action for the good of humankind (lokasa ṃgraha)—that if he did not engage in desireless actions, human beings may follow him and become renunciants, which would create confusion among humankind. So, Arjuna should do his duty in the spirit of rendering it as an offer to the “highest lord,” without any desire to receive the benefts for himself, without a sense of “I,” “mine,” “hate,” “ jealousy,” “pleasure and pain,” etc. K ṛṣṇ a even goes a step further and informs Arjuna that it is more important to do the duties of one’s own var ṇa, no matter how imperfectly done, than the superior performance of the duty of another var ṇa. Better to perform one’s own duty though void of merit, than the superior performance of the duties of another. Better to die while doing one’s own duty, perilous is the duty of other human beings. (III.35) He reiterates this point when he says: Better to do one’s own duty though devoid of merit, than to do another’s well performed. a person does not incur sin [accumulate any karmas] by doing the duty prescribed by one’s own nature. (XVIII.47) 328 T H E B H AG AVA D G Ī TĀ Let me sum up the main points of K ṛṣṇa’s discourse so far: 1 2 3 You should do your duty for the sake of duty without any attachment to its consequences for yourself. You may do your duty in the spirit of lokasa ṃgraha. It is better to perform your own dharma imperfectly than the dharma of another well-performed. I will briefy comment on these three. First, the G īt ā’s thesis of doing duty for duty’s sake has had many followers, Gandhi being the most notable among them. This thesis, however, has given rise to numerous problems. An important question arises: How to understand the principle of doing your duty for duty’s sake? The question is: Is it possible to eliminate the desire for consequences while performing actions? Consider the case of a physician or a surgeon who treats a patient. Should he not desire that his treatment cure the patient? Is the G īt ā asserting that the surgeon should do his duty of treating his patient without any consideration of the likely results that might follow from his treatment of the patient? Alternately, is the G īt ā asserting that the surgeon’s efforts should be directed toward curing the patient? Would the second alternative amount to saying that the surgeon is interested in the consequences? Is it not rather the case that a doctor or a physician’s indifference to what his treatment yields would give rise to the judgment that the doctor does not care? I would suggest both replies are intended by the G īt ā. The frst is a straightforward reply which makes a distinction between the consequences for the patient irrespective of whether he is cured or not, and the consequences for the doctor himself. By “fruits,” the G īt ā and the Indian psychology of action generally mean the latter, as is borne out by the verse II.38 quoted above. In other words, the G īt ā recommends that the physician should not be motivated by the likely consequences for herself (viz., whether he suffers fnancial loss, makes proft, or whether he receives praise or blame for his success or failure as the case may be). This is true inner freedom, non-attachment, but he should not be indifferent to whether her treatment cures the patient or hurts him. For a responsible agent the latter concern is important, while the concern about his own fortune is not. The second answer is a little more diffcult, not exactly stated in the G īt ā but may nevertheless be taken to be not only compatible with the teachings of the G īt ā but needed for it to hold good. This reply would require asking what constitutes the identity of an action? How far the identity of an action extends? In the example under consideration, the identity of an action extends up to curing the patient, but not to money, fame, and fortune, i.e., “external goods” in the language of Alasdair MacIntyre.5 In other words, curing the patient is a constituent of what a surgeon is supposed to do, and these constituents are 329 T H E B H AG AVA D G Ī TĀ not the “consequences” that the G īt ā has in mind. K ṛṣṇa recommends that the surgeon should not be interested in the external goods for himself, e.g., money, pleasure and pain, success and defeat. One should not be attached to these feelings because their pull over the human mind is very strong. Arjuna is asked to his duty with “evenness,” “sameness,” (sama ḥ).6 “Samatvam” in the G īt ā means “inner poise,” “balanced indifference,” “equality,” “sameness,” “equanimity,” etc. It is used to signify mastery over one’s self, the conquering of anger, pride, ambition, etc. The importance of samatvam is emphasized early in the G īt ā and is reiterated often throughout the text. The objection that I raised earlier and which I am trying to answer has an unwarranted assumption or presupposition: Namely, that an agent’s performing an action or doing something is always and necessarily motivated by the desire for his/her own pleasure and avoidance of his/her own possible pain. If this were the case, then, of course, it would be psychologically impossible to exclude that motivation and still be an agent. The psychological theory of action is questionable and may indeed be wrong. It is certainly necessary in undertaking any action to aim at a result, but that result need not be one’s own pleasure, proft, or gain; one may simply wish to cure one’s patient, and not entertain the thought of earning praise or making some fnancial gain. The G īt ā therefore is not violating the principle “ought implies can.” Again, one may raise the issue: Does working for lokasa ṃgraha contradict the themes that the agent should do his duty for the sake of duty and not for any consequence for himself/herself ? K ṛṣṇ a argues that a karma yogin does not aim at his/her own success or failure; he aims at the good of humankind (of the community), not his own good or beneft. The larger the goal one entertains, the lesser would be his concern for his own fortune and fame. An action has the following constituents: agent → motivation → action → consequence → for oneself or for another. K ṛṣṇ a asks Arjuna to perform desireless actions, i.e., the agent must not be motivated by the thought of beneftting himself; the thought of consequences for the others (the patient, the community, humankind, etc.) should be the motive. Thus, “desireless action” means “without any desire for the fruits of the action” for the agent of the action. Finally, how are we to construe the concept of “svadharma”? A traditional construal holds that a person’s svadharma is determined by his var ṇa. If he is a k ṣatriya, his svadharma is to fght for a righteous cause. But such a construal takes away from the G īt ā the universality of its message and makes it relative to the Hindu var ṇa-bound duty. On my interpretation of the G īt ā, the actions of human beings must be motivated by the welfare of the society, that society as a whole functions the best when each person knows his/her “place” and works to reach his/her own potential and for the good of the entire society. I would prefer to say that svadharma signifes that each person has his/her 330 T H E B H AG AVA D G Ī TĀ “station in society and the duties attached to it.” In that case, svadharma would mean the individual’s own dharma, something along the line of Bradley’s notion of “my station and its duties.” One may wonder, why K ṛṣṇ a found it necessary to emphasize repeatedly that inactivity is wrong, that action is better than inaction. A review of the social climate of India during those days would help us to understand K ṛṣṇ a’s repeated insistence that action is better than inaction. The doctrine of karma, “as you sow, so shall you reap,” dominated the Indian social scene. People began believing, it is better not to act than to act. To put it differently, not acting would amount to not accumulating any karmas. Consequently, it became prevalent that the true goal of life, i.e., mok ṣa, can be attained by renouncing an active life altogether, by becoming a hermit, by dropping out. In short, there were two ideals prevalent during those days: Niv ṛtti and prav ṛtti. There were those who believed that renouncing worldly life is a way to pursue the higher life (niv ṛtti). Again, there were those who did not wish to pursue a higher life and undertook all recommended actions with a view to attaining rewards without any worries about accumulating karmas ( prav ṛtti). K ṛṣṇ a informs Arjuna that by abandoning his duty, i.e., by inaction, the true goal of life cannot be realized. One accumulates karmas not only by “wrong” actions, but also by not doing what one should do. There is no need for Arjuna to abandon activity, rather he should abandon the attitudes that cause attachments and result in the accumulation of karmas. Our desires, the sense of the “I” and the “mine,” greed, pleasure, fear, hate, etc., bind us to this world. If we do our duties simply because scriptures require us to do so, or because God wishes us to do so, and without any desire to gain any benefts for ourselves, then no karmas are generated by such acts. In so informing Arjuna, K ṛṣṇ a preserves the spirit of renunciation and demonstrates that one can lead a life of activity without accumulating karmas. Thus, karma yoga is a Golden Mean between the two extremes of prav ṛtti and niv ṛtti. It does not ask one to renounce actions, but rather to renounce the attachments to the actions that bind one to the world and perpetuate the cycle of birth and death. In the G īt ā, karma yoga is advanced as an effective means for attaining mok ṣa. Even if it is hard to achieve the practice of karma yoga, it is not for that reason impossible provided it is rightly understood and the aspirant clearly comprehends what is entailed in the practice of karma yoga. He must not only act knowing that actions done with attachment bring bondage, but also have the right knowledge, i.e., he must understand the distinction between the lower and the higher self, and that all actions are performed by the lower nature which is merely an expression of the gu ṇas. K ṛṣṇ a then proceeds to ground his theory in a large metaphysical theory of the self and its distinction from prak ṛti. So, I will now turn to this aspect of K ṛṣṇa’s teaching. 331 T H E B H AG AVA D G Ī TĀ Path of Knowledge ( Jñāna Yoga) Path of Knowledge ( Jñāna Marga) Such contacts (contact of the senses with their objects) do not trouble who is wise, O K ṛṣṇa, who remains equal in pain and pleasure, becomes ft to attain immortality (self-realization). (II.15) All actions are done by the gu ṇas of prak ṛti; but deluded by egoism the self thinks, “I am the doer.” (III.27) Just as a faming fre reduces wood to ashes, O Arjuna; so, the fre of knowledge, turns all actions to ashes. (IV.37) And so, always think of me, while fghting, with your mind and intellect set on me, you will come to me, without any doubt. (VIII.7) The G īt ā, in its colophon, after each chapter, calls itself a “yoga śāstra.” K ṛṣṇa invokes Arjuna to achieve “yoga,” “to become a yogi,” “you be a yogin.”7 Who is a “yogi” in the context of the G īt ā? Very early in the G īt ā, K ṛṣṇa identifes yoga with samatvam (evenness or sameness). A yogi has a sense of equality between success and failure, an attitude of sameness regarding all pairs of opposites (dvandva). K ṛṣṇa tells Arjuna that a person who sees the path of renunciation and the path of unselfsh work the same is ft to attain immortality.8 He further points out that samatvam obtained through the buddhi-yoga ( yoga of intellect) fnds expression in an aspirant’s voluntary resolution to devote himself to ni ṣk āma karma.9 The essence of buddhi is determination (vyavasāya); it is not simply intellect but intellect-will and encompasses within its fold both intellect and decisions.10 It enables a person to achieve resolve and correct misconceptions about karma, self, etc. Disciplined by intellect, one [karma yogi] renounces both good and evil; so, strive for yoga; yoga is “karme ṣu kau ṣala,” i.e., it is excellence in action. (II.50) 332 T H E B H AG AVA D G Ī TĀ Thus, karma yoga is not only ni ṣk āma karma, but also buddhi-yoga. K ṛṣṇa does not stop here. Basing his theory on the classical Sāṃ khya school of Indian philosophy, K ṛṣṇa forges an inner connection between the path of action and the path of knowledge. The idea of the path of knowledge in the G īt ā refers to the Sāṃ khya idea that mok ṣa (S āṃkhya “kaivalya”) is brought about by the knowledge of the distinction between prak ṛti and puru ṣa. On the Sāṃ khya theory, which the G īt ā accepts, prak ṛti—from which the entire empirical universe including the human body, mind, intelligence, and sense organs all evolve—consists of the three gu ṇas, viz., sattva, rajas, and tamas.11 Sattva stands for those qualities that correspond to moral goodness, purity, and what is conducive to the rise of the knowledge of the truth. Rajas stands for such qualities as spiritedness, energy, and activity, and tamas stands for stupor and inaction. The gu ṇas are not only ever-changing, but they also mutually cooperate and confict with each other. Puru ṣa or pure consciousness, independent of prak ṛti, is a disinterested spectator, a mere witness. However, puru ṣa, though one, becomes many empirical selves by virtue of not distinguishing itself from prak ṛti. This nondistinction from prak ṛti and the consequent confusion is the source of bondage just as the knowledge of the distinction between puru ṣa and prak ṛti is freedom. Using the conception of the gu ṇas, K ṛṣṇa makes the following points: 1 2 3 All actions are performed by the gu ṇa-self; You are not a true agent; and Agency belongs to the empirical person rather than to the pure self. The idea is that once I know that my true self is neither the agent nor the enjoyer of the fruits (of action), I will no longer be attached to those fruits (of actions), and I will be able to follow the path of karma yoga. Thus, the possibility of the path of action lies in the possibility of knowing the true nature of the self as distinguished from the empirical person, a product of prak ṛti. The gu ṇas are agents of everything; they run the wheel of prak ṛti. The self is not affected by their operations, because it has transcended the gu ṇas; it is indifferent to pleasure and pain, and stone and gold are equal for it.12 Knowledge allows a person to perform actions without any desire for the fruits of the actions. K ṛṣṇa says, “One who is able to turn his mind inwards and fnds contentment in the self is the person who loses interest in actions and is able to perform actions without any desire for the results of the actions.”13 To emphasize the importance of knowledge, the G īt ā distinguishes between dravya yajña (material sacrifce) and jñ āna yajña (knowledge sacrifce).14 The latter is superior to the former, i.e., dravya yajña, in which a thing (i.e., ghee or molten butter) is sacrifced in fre. In this kind of sacrifce, the self is still construed as an agent; it gradually purifes the self, geared toward “purifcation of the citta (mind),” and when that is done, it leads to jñ āna yajña in which the self 333 T H E B H AG AVA D G Ī TĀ is taken to be the imperishable, not-doer of any action. “The action” we are told “fnds fulfllment” in knowledge.15 Thus, once I have the knowledge that my true self is neither the agent nor the enjoyer of the fruits (of action), I will no longer be attached to those fruits of (actions), and I will be able to follow the path of karma yoga. It also clearly demonstrates that the paths of knowledge and action go together. Thus, the possibility of the path of action lies in the possibility of knowing the true nature of the self as distinguished from the empirical person who is a product of the prak ṛti. However, there is a serious conceptual diffculty in this solution. The diffculty surrounds the systematic ambiguity of the frst-person pronoun “I.” It stands both for pure self ( puru ṣa) and for empirical self (namely, Bina Gupta). If empirical self is the agent and the enjoyer, and the knower, then it is Bina Gupta who possesses all these properties. The pure self is neither the agent nor the enjoyer. If it is not an agent, enjoyer, etc., can Bina Gupta be a disinterested agent at all when her pure self is not even an agent and her empirical self is always an interested agent? A solution to this question requires that even the pure self has some sort of agency which is not motivated by the gu ṇas, but rather a kind of free agency. The S āṃ khya metaphysics does not leave any room for it, because on the S āṃ khya theory, the pure self is only a disinterested spectator, a witness; there is no pure willing. Within the framework of the G īt ā, the problem can be resolved even without invoking the notion of pure willing, by appealing to another path, viz., the path of bhakti or devotion. Path of Devotion (Bhakti Yoga) “Bhakti” means “devotion,” “love,” etc., and signifes an intense relationship with which one approaches the divine. It is the loving worship of a specifc chosen deity, and in the G īt ā, it refers to K ṛṣṇa. K ṛṣṇa tells Arjuna to perform all actions as an offering to him, in the spirit of worship to him.16 He further adds that a jīva is saved by keeping in mind that K ṛṣṇa is the highest lord (parame śvara), and that human beings who are focused on his cosmic form, whose hearts are devoted to him, and who spend days and nights in this state are the best yogis. Such devotees (bhaktas) worship him as the highest, their minds are entirely preoccupied with him, and he saves these bhaktas from the ocean of sa ṃsāra. K ṛṣṇa emphatically declares that those who do not worship him cannot attain mok ṣa; he asks Arjuna to focus his mind and intellect on him, surrender all his actions to him,17 and that if he is able to do it, there is no doubt that after death, Arjuna would obtain an existence in K ṛṣṇa. In short, K ṛṣṇa demands single-minded devotion to him.18 He, however, does not stop at this; he goes a step further and asserts that the worship of other Hindu deities is wrong, and that those who worship other deities do not have the right knowledge. By worshipping other gods, one does not receive 334 T H E B H AG AVA D G Ī TĀ Path of Devotion (Bhakti Yoga) Whoever dies remembering me, when freed from the body, at the time of death enters my being, there is no doubt of this. (VIII.5) …worship me with single-mindedly, knowing me as the origin of all beings (IX.13) Focus your mind on me alone, and place your intellect on me; then you will dwell in me of this there is no doubt (XII:8) If you cannot concentrate your thought steadily on me, then seek to reach me, O’ Winner of wealth (Arjuna), by the repeated practice of yoga. (XII:9) By performing all actions, taking refuge in me, one attains, through my grace, the eternal, unchanging abode (XVIII:56) If your thoughts are focused on me, you will be by my grace transcend all diffculties; but if, because of ego, you do not listen to me, you will be lost. (XVIII:58) any benefts, though one might wrongly believe that he is receiving benefts. Infuenced by the three gu ṇas, this world does not realize that I (K ṛṣṇa) transcend the gu ṇas, and that I am eternal and imperishable.19 We are informed that the ignorant do not take refuge in him;20 they do not completely understand his highest, immutable, unchanging nature.21 In fact, any beneft a worshipper receives comes from K ṛṣṇa. K ṛṣṇa gives birth to all;22 devotion to K ṛṣṇa brings its own rewards. Those who take refuge in K ṛṣṇa attain the highest 23 and the worship of other gods takes one deeper and deeper in the world of ignorance, the realm of rebirth. Again, those who follow the Vedas do not attain mok ṣa. At places, the G īt ā even asserts that other deities are ignorant of the knowledge of K ṛṣṇa, which in the fnal analysis leads to liberation.24 335 T H E B H AG AVA D G Ī TĀ The G īt ā also articulates the nature of a true devotee or bhakta. A true devotee has no jealousy for any living being; he is friendly toward all, and is free from the sense of “I” and “mine,” free from attachments to pleasure and pain, and his mind is always focused on K ṛṣṇa.25 Such a person is K ṛṣṇa’s dearest devotee. Only by working for K ṛṣṇa, Arjuna will gradually purify his mind and attain mok ṣa. If Arjuna is not able to set his thoughts steadily on K ṛṣṇa, then he should seek to reach him by the practice of yoga.26 K ṛṣṇa recommends “abhyāsa-yoga,” i.e., repeated practice of fxing the mind on K ṛṣṇa; however, if Arjuna is not able to do that then he should dedicate all his actions to K ṛṣṇa. Thus, in the transition from knowledge to devotion, one has moved to grounding ethics in religion. It is obvious, in the G īt ā, though K ṛṣṇa seems to begin by saying that the path of action is the most appropriate for Arjuna, he quickly proceeds to show that following this path, one takes recourse to the metaphysical knowledge of the distinction between puru ṣa and prak ṛti, but eventually moves on to the religious attitude of devotion and surrender to the will of god who stands behind and rules over both prak ṛti and fnite selves. The three paths in that case belong together. V Are There Three Paths in the G ītā ? The question is: What is the central teaching of the G īt ā? Of the three paths, which one is primary? Is it karma yoga (path of action), or jñ āna yoga (path of knowledge), or bhakti yoga (path of devotion)? Reading the text closely impresses upon the reader the very intricate way the three paths are made to depend upon each other. On my interpretation, the G īt ā does not favor one path over the other; the three paths together make the G īt ā’s teaching a whole. Each adds to the other two; they are interdependent.27 To understand the relationship that exists among these three paths, one must keep in mind that the two paths, those of action and knowledge ( jñ āna), had already been advanced as two paths to spiritual freedom in Hinduism. The Vedic religion focused on the path of action (“action” in the narrow sense of “ritualistic actions”) as undertaking all obligations in the world, while the path of knowledge, inspired by the Upaniṣads, focused on the renunciation of worldly roles and duties. One of the K ṛṣṇa’s achievements in the G īt ā lies in breaking down the opposition between these two paths. At the same time, another path, perhaps more recent in origin, called “K ṛṣṇa Vasudeva cult,” had already made its appearance. K ṛṣṇa adds this path, i.e., the path of devotion, to the other two paths. These disciplines do not contradict each other; rather, they are interdependent. This interdependence of the three yogas has been reiterated throughout the text.28 For example, K ṛṣṇa tells Arjuna that knowledge consists in attaining attitudes appropriate to further actions without any attachment to results; it consists in removing one’s attention from the lower self and focusing on the higher self. Knowledge allows a person to perform actions without any 336 T H E B H AG AVA D G Ī TĀ desire for the fruits of the actions, which shows that the paths of knowledge and action go together. K ṛṣṇa says, “One, who is able to turn his mind inward and fnd contentment in the self, is a person who is able to perform actions without any desire for the results of the actions.”29 Thus, action and knowledge are not opposed to each other; rather the former is not possible without the latter. In order to act without any desire for the results of the actions, one must have the right attitude. This attitude comes by way of an understanding that all actions are performed by the empirical self and that the real self is not an actor in the true sense of the term. K ṛṣṇa says that actions are all done by the lower self; however, because of the deluded I-sense, the self thinks “I am the doer.”30 Arjuna’s dilemma (whether to fght or not to fght) results from ignorance; he should cut off all doubts “with the sword of knowledge” and resort to yoga.31 Devotion to K ṛṣṇa also helps an aspirant realize that the lower self is the doer of actions, because devotion is an important aspect of action32 and is related to knowledge. Knowledge and action along with devotion are called “worship.”33 When K ṛṣṇa at the end of the fourth chapter exhorts Arjuna to do his duty, and Arjuna cannot muster the courage to do so, K ṛṣṇa suggests that Arjuna should use meditation to gain victory over his desires and passions, i.e., his lower self. K ṛṣṇa states, “Fixing your mind on me ( jñ āna), devoted to me (bhakti), sacrifce to me (karma), come to me do not grieve and I shall release you of all papas (sins).”34 This teaching occurs in other chapters as well.35 K ṛṣṇa asks Arjuna to control his senses, mind, and understanding and to perform actions in worship with knowing K ṛṣṇa;36 he asks Arjuna to surrender all actions to K ṛṣṇa, fx his mind on K ṛṣṇa, without any desires, etc.37; he refers to seeing the self, seeing K ṛṣṇa, practicing yoga, and seeing pleasure and pain to be the same.38 Thus, non-attached actions are to be accompanied by meditation in order to gain knowledge of the distinction between the empirical self and the supreme self. K ṛṣṇa says, “He—who, treats alike pleasure and pain, is given to contemplation with frm resolve without any sense of ownership and attachments, is dedicated to me—is dear to me.”39 He further informs Arjuna that others with the oblation of knowledge worship him (K ṛṣṇa) as the one as well as the many, because they see everything in him;40 and, he, who knows his manifested power and his mastery, is united with him, without a doubt, by unwavering devotion.41 Thus, devotion must be accompanied with both knowledge and action. In a true yogi one fnds a harmonious assimilation of these three paths. He is said to be higher than the one who practices tapas, who has knowledge, and who performs action in the true spirit. “Such a yogi is called integrated ( yukta) to whom clods of earth, stones, gold are the same.”42 He personifes samatvam; he is free from ignorance, self-conceit, desire, anger, and rebirth; he does not grieve, he does not desire, and becomes one with the supreme.43 With that sameness, a yogi attains joy, peace, and unity of vision, i.e., he sees the sameself abiding in all beings and all beings in the self.44 In short, the practice of karma yoga, in the long run, involves knowledge and bhakti, just as the practice 337 T H E B H AG AVA D G Ī TĀ of jñ āna yoga also involves the practice of selfess action and the whole-hearted devotion. Likewise, a true and dedicated devotee needs to perform selfess action and eventually to know the brahman; the three paths come together. Irrespective of the discipline ( yoga) one uses as a starting point consistent with his own nature, the goal is to become disciplined, which is having sameness and evenness of the mind (samatvam). It is important to remember here that in the G īt ā, the goal and whatever means is used to attain that goal form a continuum, signifying the interdependence of the goal and its means. This interdependence, as shown above, is found in the disciplines of action, knowledge, and devotion. Thus, it is not surprising that K ṛṣṇa repeatedly affrms the importance of yoga: Arjuna is asked to be “yogasthaḥ,” i.e., fxed or established in the intellect,45 and “buddhi yukto,” i.e., yoked or exercised through the intellect,46 etc., in order to do his duty skillfully—and this skill has been articulated as samatvam. In summary, the G īt ā does not speak of three mutually exclusive paths to spiritual freedom, one may begin with any of these paths; however, the path that leads to the attainment of mok ṣa includes actions without any desire for the results of the actions for the agent, knowledge of the distinction between the lower and the higher self, and the single-minded devotion to the higher self. Though the path with which one starts one’s journey depends upon one’s psychological make-up (in Arjuna’s case, it is karma yoga), the aspirant must go through the other two before reaching the goal. Śr ī Aurobindo, a contemporary Vedāntin, calls the integration of these seemingly different paths “the Integral Yoga.” The three paths are unifed based on the conception of highest reality as the highest brahman or the highest puru ṣa (puru ṣottama) which the G īt ā develops. In this conception, Sāṃ khya and Vedānta are unifed. The Sāṃ khya, as is well known, admits two principles: Puru ṣa and prak ṛti. The puru ṣas are many, i.e., these are many individual selves; prak ṛti is one. The Vedānta recognizes the highest Being to be brahman or pure consciousness and synthesizes these two ancient philosophies. The unity of the G īt ā may be represented by the fgure given below. Puru˜ottama (the highest self) Prak˛ti as nature consisting of three gu˝as (k˜etra) Brahman as one being (k˜etrajña) Many finite selves as changing selves (k˜ara) Pure self as unchanging self (ak˜ara) 338 T H E B H AG AVA D G Ī TĀ It is unfortunate that commentators emphasize one path at the expense of the other two. Tilak and Gandhi, for example, emphasized the path of action. Śa ṃ kara emphasized the path of knowledge at the expense of the other two, while such theistic commentators as the modern-day Prabhupapda emphasizes the path of devotion. K ṛṣṇa’s actual sayings are ambiguous. He at times praises the path of action, at other times the path of knowledge, and still other times the path of devotion. In the long run however, K ṛṣṇa draws attention to their interdependence, although depending on the aptitudes and the abilities of the aspirant, one may begin either as a person of action like Arjuna, or as a metaphysical thinker, or as a religious devotee; however, whichever path one suits to begin with, if the G īt ā’s argument is correct, the other two would show up along the way, all leading to the same goal. The context of K ṛṣṇa’s discourse, which is that of the battlefeld, and the nature of the particular pupil with whom he chooses to discourse, a warrior by profession is neither a philosopher nor an individual given to religious sentimentality, necessitate that an initial privilege is soon counterbalanced by a large metaphysical discourse incorporating both Sāṃ khya and Vedānta, and a religious discourse at whose center lies the idea of devotion to a personal deity, viz., K ṛṣṇa himself. Thus, ethics, metaphysics, and religion are brought together. VI Concluding Reflections In conclusion, a comparison with Kant is almost inevitable. The above analysis of the conception of duty in the G īt ā leaves no doubt whatsoever that it affords duty an important place. The notion of duty as the right course of action is repeated throughout the text. In recent years, many comparative studies on the G īt ā have appeared, making the G īt ā a gospel of duty, or consequentialism, or both. So, rather than making the G īt ā a duty ethics or a consequentialist treatise, in this section, I will do something different. In modern Western philosophy, no other philosopher than Kant has tried to tie the three, viz., ethics, metaphysics, and religion together, and at the same time has tried to keep them apart. In this section, I will make a few comparative remarks in light of the G īt ā’s ethical, metaphysical, and religious arguments. Simply as a moral theory, the G īt ā’s idea of non-attached actions, performance of one’s duty without considering its likely consequences for the doer, almost resonates Kantian account of duty for duty’s sake. However, the Kantian account is embedded in a rationalism, in a theory of reason, which is hard to fnd in the G īt ā. To be precise, a theory that the source of the moral law is the pure practical reason deeply installed within every human being is lacking in the G īt ā. The lawgiver for Kant is not an authority outside of the human heart; it is none other than the human reason itself. In the G īt ā, K ṛṣṇa who identifes himself as a human incarnation of the brahman-ātman never suggests that he is the lawgiver. Also, reason as a grand faculty with its theoretical-practical divide is not available in the G īt ā. The moral laws in the Hindu tradition are 339 T H E B H AG AVA D G Ī TĀ given neither by god nor by reason, but by, and announced in, the heard texts whose origins are timeless. Again, Kant does something, which the G īt ā does not. Any ethical philosophy must confront the question: What is the standard of morality? How does one recognize, i.e., by what criterion, an “ought” to be a true ethical imperative? Kant directly confronts this question and answers it in terms of his principle of the universalizability without contradiction.47 The G īt ā does not offer any such formal principle of duty; it simply provides a principle not concerning the content of duty (what ought I to do? what is my duty?), but an answer to the question how, in what spirit, one needs to do one’s duty, so that one progresses toward mok ṣa. The content of morality is gathered from the tradition; it is not identifed by the principles of rationality. How do Kant and the G īt ā ground ethics in metaphysics? Or do they? The Kantian moral principles being a priori are free from the power of natural inclinations, thus setting up, or rather conforming to, an already available opposition between the spirit and the nature in the form of the opposition between reason as pure practical will and nature as interests and inclinations. One may ask: Is this opposition not a restatement of the Sāṃ khya opposition between puru ṣa and prak ṛti? The Sāṃ khya places, and so does K ṛṣṇa, buddhi (the only human faculty, which one can claim to be an equivalent of the reason of the rationalists) not in the heart of puru ṣa but as an evolutionary product of prak ṛti. But, does not Kant also do the same at other places when he asks what is the purpose of prak ṛti in making reason the highest faculty of the humans? Kant, in the true Christian spirit, sees the struggle between inclinations and reason as an almost unending progression, so that the human pure will never reaches the level of the Holy Will, requiring him to see the need for other lives in the pursuit of that moral ideal, whereas the G īt ā originating at the other end in a tradition that believes in rebirth moves to the possibility of achieving moral perfection here on earth, in this life. But Kant gives us something which seems to solve the problem mentioned earlier, viz., how can the pure self be a disinterested agent when it is not an agent at all? I suggest that we need a doctrine of pure will in the very heart of puru ṣa (a Kantian expectation that the self in its metaphysical essence is pure willing), and not merely a pure spectator. From metaphysics, let me quickly move on to religion. Kant, though making morality autonomous, brought in God by the back door. On the one hand, he made the moral law the essence of religion within the bounds of reason; on the other hand, he brought in God to allocate rewards to morality conjoining synthetically, morality with happiness.48 The G īt ā does not promise any such conjunction. Recall that in the epic Mah ābāhrata, to which the G īt ā belongs, even K ṛṣṇa suffers for his own actions, so that no one, not even God, can escape the power of the law of karma. The G īt ā introduces religion more directly and not by the back door. The practice of dharma, with the purpose of going to heaven, brings one back to rebirth within the clutches of the law of karma. One needs to practice dharma with non-attachment to the consequences 340 T H E B H AG AVA D G Ī TĀ if one wishes to attain mok ṣa, but that non-attachment is more readily possible by cultivating a religious attitude in the spirit of self-surrender to the will of God. This kind of religious grounding of morality is lacking within Kantian rationalism. Thus, if one has his Kantian prejudices in moral philosophy, they help him identify some Kantian concepts in the texts, and, at the same time, make him realize how these concepts are embedded in a very different intellectual tradition. Eventually, in the end, the conception of the reason of the Enlightenment of Europe comes to contrast a conception of tradition in the guise of a long and hoary textual tradition, dharma śāstra, as the guarantor of dharma into whose density reason cannot penetrate. Study Questions 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. What is yoga? What are the duties of a person belonging to the warrior var ṇa? Describe the setting in which the G īt ā was composed? Discuss the distinction between pravṛtti and nivṛtti? “Removing all attachments to the fruits of action, ever content, independent—such a person even if engaged in action, does not do anything whatever” (Git ā, IV.20). a. b. Explain the meaning and signifcance of the above passage. Do you think that the doctrine of karma yoga has any relevance for the culture you live in today? If it does, discuss some of the strongest objections to the doctrine and why they do not constitute good reasons for rejecting the doctrine. If it does not, discuss some of the strongest reasons for accepting the doctrine and why they do not constitute good reasons for the acceptance of the doctrine. 6. Explain the paths of knowledge and the path of devotion discussed in the G īt ā. 7. Examine the concept of “lokasa ṃgraha.” Is lokasa ṃgraha an altruistic act? Is it a benevolent act? An egoistic act? Give reasons for your answer. 8. Discuss the relationship among the paths of karma yoga (path of action), bhakti yoga (path of devotion), and jñ āna yoga (path of knowledge) in the Gita. Do these paths contradict one another, or is there a way in which the three can be synthesized? Give reasons for your answer. 9. Read the following sample case carefully and answers questions given below. Case of Donating Money to Help San Diego Fire Victims You have just fnished reading the Bhagavad G īt ā. In this text, when Arjuna refuses to fght, K ṛṣṇa uses various arguments exhorting him to fght, and, in 341 T H E B H AG AVA D G Ī TĀ the process, develops a philosophy of life. Some of the arguments he advances are given below. K ṛṣṇa says: • • • • Arjuna belongs to the warrior caste and it is his duty to fght; duty should be performed without any desire for the fruits (ni ṣk āma karma, desireless action); activity is better than inactivity; and by doing duty without any desire, one attains the highest good, i.e., mok ṣa. Three friends, John, Bina, and Claudio, decide to donate money to help San Diego fre victims. John believes that it his duty to do so, but he does it because he needs a tax break. Bina believes that duty should be performed without any desire for the fruits (ni ṣk āma karma, “desireless action”) and she acts simply for the sake of duty. Claudio believes that it his duty to help, but he also desires to please his fre-fghter son, which in turn gives Claudio pleasure and self-satisfaction. 1 2 In all three cases, San Diego fre victims received help. Desire and duty motivated John and Claudio’s actions. Bina performed her action without any desire for the fruits. In the language of the G īt ā, Bina’s action was a desireless action (ni ṣk ā ma karma). In other words, though duty accompanied John and Claudio’s actions, desirelessness did not. The questions to consider are: Are their actions moral? Are their actions, right? To put it differently, what is the criterion of morality according to the G īt ā ? What makes an action right in the Gita? Duty or desirelessness? Would you say that according to the doctrine of ni ṣk ā ma karma there are right actions which are not moral? What would the G īt ā ’s response be to these questions? What is your response? Be specifc in your response and provide rational arguments to substantiate your position. When I examine my life, I see that there are times when I can make a separation between the actions that I perform and the possible results of my actions. I do X without desiring consequences that might ensue from X. Irrespective of the motive of my action, when the dust settles, I will get a tax break (in the above example of donating money to fre victims). Is my action really “desireless”? Likewise, K ṛṣṇ a advises Arjuna to fght. Fighting is an intentional act; K ṛṣṇ a is persuading Arjuna to fght to correct a wrong, to recover the lost kingdom. He is advised to fght without receiving any benefts, i.e., Arjuna is supposed to fght without the thought of recovering the lost kingdom. Given the circumstances, is it possible to separate the action from the consequences? Do you see any contradiction here? Substantiate your position with rational arguments. 342 T H E B H AG AVA D G Ī TĀ Suggested Readings For an easily readable translation, see Barbara Miller, The Bhagavad G īt ā (Canada: Random House, Bantam Classics, 1986); for consequentialism and deontology debate, see Sandeep Sreekumar, “An Analysis of Consequentialism and Deontology in the Normative Ethics of the Bhagavadg īt ā,” Journal of Indian Philosophy, Vol. 40, 2012, pp. 277–315; S. S. Chakravarti, “Consequentialism and the G īt ā,” Evam, Vol. 3, No. 1 & 2, 2002. http:// www.svabhinava.org/Hindu Civilization/SitansuChakravarti/Consequentialism.pdf. For karma yoga, see Simon Brodbeck, “Calling Krsna’s Bluff: Nonattached Action in the Bhagavadg īt ā,” Journal of Indian Philosophy, Vol. 32, 2004, pp. 81–103. For the G īt ā as Virtue ethics, see Bina Gupta, “Bhagavad G īt ā as Duty and Virtue Ethics: Some Refections,” The Journal of Religious Ethics, 2006, Vol. 34, pp. 373–395. Roopen Majithia, “The Bhagavad G īt ā’s Ethical Syncretism,” Comparative Philosophy, Vol. 6, 2015, pp. 56– 79, seeks to reconcile tensions in the Indian tradition, and Robert Minor in “The G īt ā’s Way as the Only Way,” Philosophy East and West, Vol. 30, No. 3, July 1980 articulates three paths of the G īt ā as G īt ā Yoga. 343 Part VIII MODERN INDIAN THOUGHT 16 MODER N IN DI A N THOUGHT I Introduction The classical philosophical systems had reached their high point by the time British rule in India began. The Sanskrit pundits continued to instruct students in the classical systems, and no new major innovation seemed to be in the offing. These Sanskrit scholars applied themselves to the school of Navya-Nyāya (new logic); outstanding scholars devoted themselves to teaching and writing about this school. However, no major works were published, though “private papers,” known as “kroḍapatra,” continued to accumulate.1 Students used them to defend their own positions as well as to criticize those of their opponents. Lineage of such students traced back their ancestry to great pundits, and it is diffcult to ascertain with accuracy which, if any, philosophical innovations were achieved. In the nineteenth century, with the spread of English education, scholars well versed in Western philosophy and the English language appeared on the Indian philosophical scene. Some of these scholars learned Sanskrit and read original Sanskrit texts of the classical past, but still wrote in English, comparing Indian philosophies to Western philosophies. As a result, a discipline called “comparative philosophy” was born. The political, social, and economic effects of the British rule on India were profound. Tension between the forces of tradition—through which the Indian culture had grown—and the forces of modernity had increased. The Hindu intellectuals found themselves in an ambiguous situation; there was an awareness of the sense of responsibility to its own culture as well as a sense of distance from it. They studied, absorbed, and understood the Western social and political concepts, and seized this opportunity to demonstrate that Indian philosophy is as great as any other philosophies. As a result, there arose a wide spectrum of social reformers, philosophers, political leaders, religious innovators, and cultural critics, e.g., Vivekananda, Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Aurobindo, Tilak, K. C. Bhattacharyya (KCB), Tagore, Seal, Halder, and Gandhi. Some of these fgures were not professional philosophers, but they were educated, literate, and action-oriented public fgures, and their ideas were of great signifcance even for academic philosophy. 347 MODERN INDIA N THOUGHT The fact that Tagore, a poet and a non-academic fgure, was elected to be the President of the frst Indian Philosophical Congress in 1925 testifes to the importance and impact of these individuals in India. In this chapter, it is not possible to discuss all these individuals and their contributions. I will focus only on two important individuals of the preindependence era: KCB and Śr ī Aurobindo; the latter, like KCB, was not a professional philosopher, but both individuals infuenced the modern minds at many different levels and in many ways. They brought to the forefront the fact that modern Hindu intelligentsia, while professing loyalty to its own tradition, transformed the Hindu tradition—perhaps, partly under the infuence of Western thinking and partly to meet social and political challenges of the day. These individuals re-read, re-understood, and re-interpreted the Vedānta school, and infuenced not only the philosophical but also the religious, political, and social thinking of Hindu minds. Thus, it is safe to say that Vedanta, especially Advaita Vedānta, has played an important role in the self-understanding of the modern Hindu intelligentsia. K. C. Bhattacharyya (KCB) It is not an exaggeration to say that KCB is one of the leading contemporary Indian philosophers. Though all of KCB’s published works are contained in two volumes of Studies in Philosophy,2 one can say that the pages of these two volumes are flled with the original ideas on many topics spanning the entire range of Indian and Western philosophy. KCB had carefully studied ancient Indian philosophical schools, e.g., Advaita Vedānta, Sāṃ khya-Yoga, and Jainism. He was also well versed in classical German philosophies, especially of Kant and Hegel. In his philosophy, one fnds an assimilation of both Eastern and Western philosophies. The goal of his philosophy was neither to espouse a specifc philosophical perspective nor to provide a defense of a particular darśana of Indian philosophy. One marvels at his understanding of philosophers Indian and Western alike, as well as at the originality of his thought-provoking ideas. Kalidas Bhattacharyya,3 the youngest son of KCB, divides his father’s philosophy into three phases. The frst stage extends from 1914 to 1918, during which he published three papers: “Some Aspects of Negation,” “The Place of the Indefnite in Logic,” and “The Defnition of Relation as a Category of Existence.”4 The second extends from 1925 to 1934,5 during which he published fve papers titled “Śa ṃ kara’s Doctrine of Māyā,” “Knowledge and Truth,” “Correction of Error as a Logical Process,” “Fact and the Thought of the Fact,” and “The False and the Subjective,” and his monograph entitled The Subject as Freedom. The third, the shortest of the three stages, lasted a little more than a year (1939), during which he published three papers: “The Concept of Philosophy,” “The Absolute and its Alternative Forms,” and “The Concept of Value.”6 348 MODERN INDIA N THOUGHT In this brief chapter on KCB’s philosophy, it is not possible to do justice to all the issues that his philosophy raises. I will focus on the concept of the “absolute” in KCB’s philosophy. Limiting this chapter to the concept of the absolute makes sense for many reasons; however, I will name only a few. KCB discusses this concept in two of his articles, viz., “The Concept of Philosophy” and “The Absolute and its Alternative Forms.” These articles appeared in the third and the fnal phase, the richest and the most profound phase of his writings; they refect the culmination of his philosophical thinking. Second, KCB’s concept of the three absolutes is strikingly original; it is a unique contribution to the philosophical thought the world over. Third, the search for the absolute has been the primary concern of Indian philosophy from the Upaniṣads (600–300 BCE) to the neo-Vedānta of the twentieth century via the classical Vedānta of Śa ṃ kara and R āmānuja. By focusing on this concept, we would get a better understanding of the development of the concept of “absolute” in the entire spectrum of Indian philosophy. Finally, the discussion of this concept not only shows how KCB’s philosophy fts into Indian philosophy historically but also demonstrates the progress of his philosophy through three phases insofar as KCB discusses the absolute as “indefnite” (the frst phase), as “freedom” (the second phase), and as “alternation” (the third phase). The Absolute as Indefinite Those of us who are familiar with KCB’s philosophy know well that he was infuenced by Jaina logic. KCB’s conception of the absolute as indefnite follows his interpretation of the Jaina theory of anek āntavāda. In his article, “The Jaina Theory of Anek ānta,” KCB shows that neither the category of “identity” nor of “difference” is basic to philosophy, and that the alternation of the two is more satisfactory. At the outset, KCB informs his readers, “The Jaina theory of anek ānta or the manifoldness of truth is a form of realism which not only asserts a plurality of truths but also takes each truth to be an indetermination of alternative truths.”7 He further adds that the purpose of his paper is “to discuss the conception of a plurality of determinate truths to which ordinary realism appears to be committed and to show the necessity of an indeterministic extension such as is presented by the Jaina logic …”8 KCB analyzes the defnite and the indefnite, and, from the contrast between the two, deduces the seven modes of truth. To say that from one perspective a determinate existent X is, and from another perspective is not, does not imply that X is X and it is not Y. It rather means that an existent X, as an existent universal, is distinct from itself as a particular. Accordingly, every mode of truth is a determinate truth as well as an indetermination of other possibilities or alternative modes of truth. These modes of truth, argues KCB, are not merely many truths but “alternative truths.”9 From one perspective X is existent; from another perspective X is non-existent; however, when X is viewed as existent and non-existent simultaneously it becomes indescribable 349 MODERN INDIA N THOUGHT (avaktavya); there exists an “undifferenced togetherness” between the two, which KCB calls “indefnite.” Each mode of truth, as an alternative to others, is objective. KCB applies the above conception of the defnite and indefnite to the concept of the “brahman.” The Upaniṣads, as we know, identify a single, comprehensive, fundamental principle by knowing which everything else in this world becomes known.10 This fundamental principle, brahman or absolute, defes all characterizations. BU categorically asserts that there is no other or better description of the brahman than neti, neti (“not this,” “not this”).11 In the classical non-dualist Vedānta of Śa ṃ kara, the brahman or the absolute is that state where all subject/object distinction is obliterated. The brahman simply is. KCB takes for his point of departure this consciousness that transcends both the subjective and the objective. Since this principle cannot be defned in terms of either the objective or its correlate, i.e., the subjective, he calls it the “indefnite.” In other words, both the subjective and the objective belong to the realm of the defnite and that which transcends both is the indefnite. Every defnite content of experience, holds KCB, implies an indefnite out of which it is carved. The indefnite points to a primary distinction between the defnite and the indefnite, the known and the unknown: “the indefnite is not and is indefnite at once.”12 To put it differently, “the indefnite and the defnite are and are not one.” The line between the defnite and the indefnite is itself indefnable; the defnite, being a mode of the indefnite, embodies the indefnite. KCB does not discuss the question whether absolute exists; he rather attempts to understand it. Paradoxically, it is that which cannot be understood; it is indefnite (not comprehensible) and defnite (somehow comprehensible) at once. KCB was aware that this logical absolute as indefnite cannot be an object of one’s experiences; that for it to be the basis of objects, it must be understood as the subject of our experiences. So, it is not surprising that he does not rest satisfed with the logical absolute, and eventually takes a psychological approach in which the absolute as indefnite is construed as the absolute as subject or freedom. The Absolute as Subject or Freedom The most comprehensive statement of the absolute as freedom is analyzed in the monograph The Subject as Freedom, which was written long before KCB wrote the articles “The Concept of Philosophy” and “The Alternative Forms of the Absolute.” In this work, KCB begins with an analysis of the distinction between the object and the subject. “Object” is what is meant by the “subject”; the “subject” is other than the object. When one knows an object, one becomes aware of the meaning of the term “object.” Thus, the word “this” symbolizes the object. When one uses the word “this” to signify a specifc object, others also use “this” to denote the same particular object. Thus, the pronoun “this” has a general meaning, and both the speaker and the hearer use it to refer to an object. The subject, however, is not meant; it has no universally accepted 350 MODERN INDIA N THOUGHT meaning. When Bina uses “I,” she uses it to refer to Bina, but when Sonya uses “I,” she uses it to refer to Sonya, not to Bina. The word “I,” argues KCB, symbolizes the subject, so he prefers the word “I” to both “you” and “he.” The distinction between these two symbols “this” and “I” throws light on the important distinction between the subjective and the objective. The point that KCB is trying to make is as follows: The subject is not a meant entity. The word “this” symbolizes an object and has a generality about it. However, the same does not characterize the word “I” which is neither singular nor general; it is rather both singular and general. “I” takes on generality as far as each speaker uses it though in the singular, because each speaker uses it only for himself or herself. Thus, though the subject sometimes may be spoken of as an object, it is not meant as an object. In other words, when the subject is understood through the word “I,” it is not known as the meaning of the word. It is possible to objectify the subject, but the objectifcation cannot be a determinant of the subject. When one refers to the subject as the object, the subject does not become the object. Moreover, the reality of what is meant can always be doubted. In KCB’s words: “… the object is not known with the same assurance as the subject that cannot be said to be meant. There may be such a thing as an illusory object….”13 After articulating subjectivity as an awareness of the subject’s distinction from the object, KCB distinguishes among the three stages of subjectivity. In the frst stage, the self identifes itself with the body; in the second, the self identifes with images and thoughts; and in the third, initially there is a feeling of freedom from all actual and possible thoughts, which is followed by an awareness of the subject as “I” in introspection, eventually leading one beyond introspection to complete subjectivity or freedom. The different stages of subjectivity are reached progressively: The denial of the preceding gives rise to the succeeding stage until there is nothing left to deny. At each stage there is an inner “demand” to go beyond that stage. It is important to note that the introspection of the subject as the “I” is the realization of the free nature of the subject, where one has an awareness of the subject’s freedom. However, this awareness must be denied to make way for complete freedom. KCB here is making an important distinction between the “subject as free” and “subject as freedom”; the former being the introspective stage of subjectivity, and the latter the ultimate stage, the ideal, the subject’s ultimate goal. In this context, one might ask why to assume this subjective attitude. Even if we assume that it does lead to freedom, can one not make a similar case for the objective attitude? He discusses some of these issues in his articles “The Concept of the Absolute and Its Alternative Forms” and “The Concept of Philosophy.” The Absolute as Alternation At the outset of his paper on the absolute as alternation, KCB informs his readers that philosophy begins in refective consciousness, i.e., an awareness 351 MODERN INDIA N THOUGHT of the relationship between refective consciousness and its content.14 Refective consciousness and its content imply each other, and he takes this relation of “implicational dualism” as the starting point to discuss his concept of “alternative absolutes.” Using the Kantian distinction between the “forms of consciousness” (which KCB never questions), he argues that consciousness functions diversely, better yet alternately, as knowing, willing, and feeling. The implicational dualism, i.e., the relation between consciousness and content, is different in each case. In knowing, the content is not constituted by consciousness; in willing, it is constituted by consciousness; and, in feeling, the content constitutes a sort of unity with consciousness. In each attitude, the dualism of the content and consciousness can be overcome; consequently, each has its own formulation of the absolute. There are three absolutes corresponding to the three forms of consciousness: Knowing, willing, and feeling, in KCB’s words, “truth, value, and reality (or freedom).”15 In knowing, the content is freed from consciousness and the absolute is truth. In willing, consciousness is freed from content and the absolute is freedom. In feeling, there is a consciousness of unity and the absolute is value. The Absolute, when freed from this trifold implicational dualism, by its very nature is understood in a triple way. Let us examine it further. The Absolute as Truth In knowing, the object of knowledge stands as independent of the act of knowing. The content is “unconstituted by consciousness.” “It may, accordingly, be (loosely) called a known no-content. It is explicitly known as what known content is not.”16 The act of knowing rather discovers the object. The known content need not be known, which explains why KCB even asserts that to know an object is to know “a timeless truth.” “The object may be temporal but that it is in time is not itself a temporal fact.”17 So, according to KCB, the realist’s defnition of knowledge is valid, but what is claimed to be known may not really be known in the realist’s sense of the term. Space limitation does not permit me to examine in detail how the process of knowing leads to the absolute as truth, because that would necessitate an indepth study of the issues discussed in his article “The Concept of Philosophy.” For our purposes, the following will suffce. In this article, KCB argues that the task of philosophy is the justifcation of beliefs by a “higher kind of knowledge” which can be arrived at by analyzing speech and thinking. Speech and thinking admit of grades. As a result, we get the grades of thought and the grades of thinking corresponding to each other pointing to the grades of the theoretic consciousness.18 The belief that “the absolute is” is implied in the theoretic consciousness of “I am not.” The denial of “I” is possible because of our belief in the absolute. By “thought,” KCB means all forms of theoretic consciousness involving the understanding of a speakable. Philosophy presents beliefs that are speakable; 352 MODERN INDIA N THOUGHT they are expressions of the theoretic consciousness, and, as understanding of the speakable they consist of the four grades of thought: Empirical, contemplative or pure objective, spiritual, and transcendental. In empirical thought, the content refers to an object perceived or imagined to be perceived. Such reference constitutes a part of the meaning of its content. Pure objective thought involves reference to an object but not necessarily to a perceived object. Subjective or spiritual thought does not involve any reference to an object. It is therefore purely subjective. Transcendental thought is the consciousness of a content that is neither subjective nor objective. It refers neither to things, nor to universals, nor to individuals, but rather to the absolute truth. Science deals with the content of empirical thought which KCB calls “ fact.” The other three thoughts have contents which are either self-evident, objective contents, or truth or reality. In science, the content, according to KCB, is literally speakable. In pure objective attitude of philosophy, contents “demand” to be known, but are not actually known. Here we get metaphysics or philosophy of an object. The third level of thinking is the philosophy of the subject, and, in the fourth and the fnal kind, we have the philosophy of the truth. The distinction among the various grades of theoretic consciousness is of utmost importance since KCB’s philosophy is concerned not with the frst but with the last three grades of theoretic consciousness. The last three stages are, in fact, not entirely different from each other, and, according to KCB, one stage necessarily leads to the next. The absolute is reached through a series of denials. Each earlier stage is negated, and each negation leads to the formation of the beliefs contained within the next higher stage. Whereas the spiritual reality is symbolized as “I” and expressed literally as self, truth is symbolized as “not I,” and is, therefore, not reality, not to be enjoyed, and not literally expressible. For KCB, truth is “self-revealing, what is true being spoken as what the speaking I is not.”19 Consequently, it is not identical with the self as Advaita Vedānta maintains but is defnable as what the self is not. The last stage is beyond negation since the theoretic denial of the self in the form “I am not” leaves one remainder. What remains to make such self-denial possible is the absolute. As an undeniable being, the absolute is truth. The absolute does not have anything outside from which to be distinguished. Truth is the absolute, but the absolute is not the only truth. It can be distinguished from alternative forms of itself. As undeniable being it may be truth, or as the limit of all transcending negating processes it may be freedom, or as their indeterminate togetherness, it may be value. Absolute as Reality (or Freedom) The second is the absolute of willing. In this absolute, the content is constituted by willing. Willing is active; it is constructive. In the absence of willing this absolute is nothing; it is understood as a negation of being. Willing in fact is willing of itself which is its denial. When a will is satisfed, it is superseded, and, in that sense, denied. 353 MODERN INDIA N THOUGHT The process of willing, which leads to the absolute as freedom, is analyzed in the work The Subject as Freedom, which I have already discussed. In this work, no clear distinction has been made between the knowing and the willing, resulting in the impression that the absolute as freedom is also the absolute as truth. In “The Concept of Philosophy,” as has been explained earlier, the pursuit moves from empirical fact to self-subsistent object, from objectivity to subjectivity, and from subjectivity to the truth. Thus, the individual self is transcended in favor of truth, and the absolute object is more fundamental than facts or universals. In the work, The Subject as Freedom, the individual self is transcended in favor of the subject, the “I,” which in turn is transcended in favor of freedom itself. The Absolute as Value The third is the absolute of feeling and the matter is quite different in the case of feeling. The beautiful object appears as beautiful in feeling, and “shines as a self-subsistent something,” distinct from its knowable parts. In other words, there is a unity free from the duality of content and consciousness. It is a content “that is indefinitely other than consciousness” or consciousness “that is indefinitely other than content.” The term “indefinitely,” for KCB, signifies that the absolute of feeling is indifferent to both being and non-being, and accordingly, the absolute is transcendent. Value is the unity of the felt content and its feeling. It is different from its knowable relations and its relation to its parts. This is how KCB suggested we should understand the being of value. Felt content, though not definite in itself, is understood “as though it were a unity.”20 Reflection demands such a unity. The realist position that the value is objective and the idealist position that the value is subjective are not preferable and their alternation is stopped when the unity becomes definite. “The unity of felt content and feeling may be understood as content that is indefinitely other than consciousness or as consciousness that is indefinitely other than the content.”21 Value as such is unity which is the indetermination of content and consciousness and not identity. This relation defines the absolute of feeling. Concluding Ref lections KCB’s thesis of the triple absolutes is indeed unique, interesting, and thought-provoking. The absolute of knowing is truth, the absolute of willing is freedom, and the absolute of feeling is value. The triple absolute is the prototype of the three subjective functions, which are mixed in our everyday experiences. However, each experience can be purifed of the accretions of the other functions and can become pure or absolute. Absolute knowing is the apprehension purged of all non-cognitive elements; it is the apprehension of the object-in-itself. Absolute willing is willing purged of all objective elements. Absolute feeling is feeling purged of all cognitive and volitional 354 MODERN INDIA N THOUGHT elements. Each absolute is a pure experience, i.e., positively an actualization of the unique nature of each function, and negatively, a lack of confusion or mixture with other functions. For KCB, the absolute is the alternation of these three functions. There are three alternative Absolutes, which cannot be synthesized into one. KCB’s conception of the absolutes is a corollary of his logic of alternation that he advocates. It is a logic of choice, commitment, and co-existence. In our everyday discourse we are presented with alternatives, and we must choose not because one alternative is correct and the other false, but because we must choose, and having chosen, we must abide by our choice. KCB rejects inclusive disjunction (either-or, perhaps both) and accepts exclusive disjunction (either-or, but not both). X may be true, Y may be true; however, the conjunction of X and Y is not true. Alternation, so important in practice, is equally important in theory. With the logic of alternation, KCB rejects philosophies that claim that their philosophy is the only true philosophy. For him, there are different paths that lead to different goals, and each goal, in itself, is absolute. No absolute is superior to any other; the ways of the absolute diverge, but one is not preferable to the other. When one is accepted, the others are automatically rejected. These are genuine alternatives. The absolute is an alternative of truth, freedom, or value. To sum up, KCB provides three possibilities of encountering an Absolute: The absolute as positive being or truth, or the non-being as freedom, or “their positive indetermination” or value. In K. C. KCB’s reading of the tradition, the Advaita Vedānta takes the absolute as positive truth; the Buddhism of the Mādhyamika school takes the absolute as non-being or freedom; and the Hegelian Absolute is the identity of truth and freedom or value. Thus, there are three irreducible Absolutes.22 It would be interesting to compare the three Absolutes as they are presented in “The Concept of Philosophy” (CP) with the three Absolutes of “The Concept of the Absolute and Its Alternate Forms” (AAF). CP AAF Knowledge Advaita being Truth Willing Feeling Mādhyamika non-being Hegelian synthesis Freedom Value It is strange that KCB reads Hegelian absolute as value. In his interpretation of the Hegelian absolute as value, KCB seems to misconstrue Hegel for whom the science of the absolute is logic. Before concluding this section, I would raise some questions about three crucial concepts found in KCB writings in the hope that these questions might provide impetus for further research and dialogue on these important concepts, viz., “demand,” “denial,” and “alternation.”23 355 MODERN INDIA N THOUGHT 1 2 3 The concept of “demand” frequently appears in KCB’s writings. He informs his readers that philosophy begins in refective consciousness in which there exists a distinction between content and consciousness, and a “demand” for the “supra-refective consciousness,” i.e., a consciousness in which the distinction between the content and the consciousness is clearly visible. One wonders what this demand is. What kind of a consciousness is it? Is this consciousness not conscious of either a known or a willed or a felt content? KCB speaks of the grades of thought and the corresponding grades of speakables and argues that the ascent from the lower to the higher, from the less perfect to the more perfect, is possible because it is possible to deny the lower. Each ascent is based on a series of denials. For example, objects are denied because of our belief in the subject, and the denial of the subject or the self is possible because of our belief in the absolute. All of us would agree that the denial of facts is possible; however, only particular facts can be denied. One fact may be denied in favor of another, yet how does one deny all facts? The ascent to the fnal stage is diffcult to grasp in the absence of some philosophical position, e.g., Advaita Vedānta. I can possibly deny my ego only if I concede the reality of a non-subjective awareness that provides the basis for such a denial. How does one move from one attitude of thought to the other? KCB explains the mutual relation between truth, freedom, and value as alternation. He uses the term “reality” to mean “freedom” and concludes his discussion of the alternative absolutes in the following words: … it appears to be meaningless to speak of truth as a value, of value as real, or of reality as true while we can signifcantly speak of value as not false, of reality as not valueless and of truth as not unreal, although we cannot positively assert value to be truth, reality to be value and truth to be reality. Each of them is absolute and they cannot be spoken of as one or many. In one direction their identity and difference are alike meaningless and in another direction their identity is intelligible though not assertable. Truth is unrelated to value, value to reality and reality to truth, while value may be truth, reality value and truth reality. The absolute may be regarded in this sense as an alternation of truth, value, and reality.24 In what sense is KCB using the concept of alternation? He informs his readers that truth, freedom, and value are not simply alternative descriptions of the Absolute. Is it simply epistemic? It does not appear to be so. Is alternation constitutive of the Absolute? If so, is it whether the absolute is one or triple? It is not clear how the absolute, though of the alternative nature in the sense of “either-or,” can at the same time remain as the Absolute. These questions notwithstanding, KCB’s conception of “alternation” is unique; it is an original contribution to philosophy. He has made a genuine attempt to show that absolutism is not incompatible with pluralism. His 356 MODERN INDIA N THOUGHT philosophy goes a long way toward removing the popular Western misconception that Indian philosophy is only mystical, intuitive, and practical. II Śrī Aurobindo In the concluding paragraph of his magnum opus, The Life Divine, Śr ī Aurobindo presents his spiritual vision in the following words: If there is an evolution in material Nature and if it is an evolution of being with consciousness and life as its two key-terms and powers, this fullness of being, fullness of consciousness, fullness of life must be the goal of development towards which we are tending and which will manifest at an early or later stage of our destiny. The self, the spirit, the reality that is disclosing itself out of the frst inconscience of life and matter, would evolve its complete truth of being and consciousness in that life and matter. It would return to itself—or, if its end as an individual is to return into its Absolute, it could make that return also, —not through a frustration of life but through a spiritual completeness of itself in life.25 Though the above quotation begins with a hypothetical, the preceding 946 pages of The Life Divine seek to demonstrate that the claims made in the above paragraph are indeed true. Śr ī Aurobindo’s philosophy, taken as a whole, is Vedā ntic. Śr ī Aurobindo, drawing on the resources of the Vedas and the Upaniṣadic texts, asserts that the ultimate reality is brahman; it is existence-consciousness-bliss. An important part of this metaphysics is the account of evolution that he provides in his Life Divine. When compared to Western thought, evolution has not played a signifcant role in Indian thought, though its traces are found in the Vedas and the Upaniṣads; it, however, occurs more systematically in the Sāṃ khya system. Śr ī Aurobindo gave evolution the place it was due. Indeed, Śr ī Aurobindo’s theory of evolution is key to understanding his entire philosophy. The goal of his theory of evolution is to show that the evolutionary structure of the world process is due to the creative force inherent in the reality. Aurobindo rejects Śa ṃ kara’s m āyāvāda, i.e., the falsity of the world, and develops a metaphysical position called “Integral Advaita.” The world and the fnite individuals are not false, but they rather are manifestations of the brahman and are real. The brahman is both transcendent and immanent in the world, and fnite individuals are self-manifestations of the brahman by its own infnite creative energy. He subscribes to a theory of emergent evolution in which evolution presupposes a prior involution. Matter, argues Aurobindo, develops through the stages of life, mind, and many other levels of consciousness just because the spirit had descended into matter and remained in it potentially. This is a form of the classical satk āryavāda (the effect pre-exists in the material cause), which allows for the emergence of new qualitative changes. 357 MODERN INDIA N THOUGHT Any evolutionary philosophy must confront the following questions. 1 2 3 “Evolution” is a word which usually assumes the phenomena without explaining them. How to explain them? Can reality augment itself? What is the relation between evolution and the Absolute? • Is absolutism consistent with change? • Even if it is, is it consistent with the ordered and the progressive change? • Progress implies new creation: Does that imply that there is some want in the Absolute? • Does the absolute itself evolve? Or, alternately, does it contain evolution within itself? There is no doubt that Śr ī Aurobindo was aware of most, possibly all, of these questions, and formulates both his conception of the absolute spirit and the theory of evolution accordingly. In this chapter my discussion will revolve around the following question: Is a doctrine of evolution consistent with the thesis that the brahman alone is real? There are such philosophers as Whitehead and Charles Hartshorne who hold that God evolves, progressively becomes more perfect, as he was less perfect in the beginning. Śrī Aurobindo being a Vedāntin would not subscribe to such a thesis. The brahman is perfect, yet it goes through the evolutionary process. Why, and how? Can Aurobindo’s position—the brahman though one becomes many—be justifed from a philosophical standpoint? To answer these questions meaningfully, I will frst lay down an exposition of his metaphysical position. Aurobindo’s Conception of the Absolute In the very opening chapter of The Life Divine, Śr ī Aurobindo reveals the task of his philosophy as well as the unique character of his own spiritual experience. He notes that “all problems of existence are essentially problems of harmony.”26 The title of this chapter, “The Human Aspiration,” clearly informs us that Aurobindo perceived humanity as a phase of evolution attempting to seek harmony within itself and in its relation to other levels of existence. He concedes that the history of Eastern and Western philosophy testifes to the diffculties entailed in realizing such a harmony, though the interpretations of disharmony vary in the East and the West. He refers to this disharmony as “the refusal of the ascetic” and “the denial of the materialist,” and identifes the ascetic with the spiritualist who takes the matter to be illusory and the materialist with the one who takes the spirit to be illusory. He argues that both positions are extreme and one-sided. Throughout his writings, Śr ī Aurobindo provides a variety of reasons to demonstrate that both matter and spirit are equally real, because matter is also brahman: Both are real constituents of saccid ānanda, the divine reality. 358 MODERN INDIA N THOUGHT The conception of matter and spirit as equally real goes a long way toward explaining Śr ī Aurobindo’s conception of the world. “If One is pre-eminently real, ‘the others,’ the Many are not unreal.”27 The world is neither a fgment of one’s mind nor a deceptive play of m āyā. Śr ī Aurobindo’s realistic streak would not allow him to surrender the reality of the world to the deceptive play of m āyā, the theory accepted by Śa ṃ kara. Not unlike many of the older critics of Śa ṃ kara, Śr ī Aurobindo asks: Is the m āyā real or “unreal”? If it is real, there is a dualism between the brahman and m āyā. If it is an appearance, then we may ask: What is the nature of this apparent reality? Who perceives m āyā? If it is the brahman, there is an obvious absurdity. If it is the jīva, we ask, isn’t jīva itself “unreal” and due to m āyā, in which case we would have an infnite regress? For Aurobindo, “m āyā” means nothing more than the freedom of the brahman from the circumstances through which he expresses himself. Māyā is “not a blunder and a fall, but a purposeful descent, not a curse, but a divine opportunity.”28 Saccid ānanda, as an infnite being, consciousness, and bliss, creates the universe, and unfolds itself into many. Spirit’s involvement in the matter, its manifestation in the grades of consciousness is the signifcance of evolution. Evolution is the unfolding of consciousness in matter until the former becomes explicit, open, and perceptible. And, the act of transformation from the matter to the spirit is the reverse of involution—it is reunion, an evolution. Let me elaborate it further. The Nature of Creation: Involution and Evolution As energy, consciousness is not merely self-manifesting, but is capable of self-contraction and self-expansion, descent and ascent. Accordingly, in his theory of involution/evolution, Aurobindo argues that nature evolves on several levels because the brahman (saccid ānanda: Sat or existent being, cit or consciousness-force, and ānanda or bliss) has already involved itself at each level. From a logical perspective, prior to evolution there is involution through which the brahman seeks its own manifestation in the multilevel world. The order of involution is as follows: Existence Consciousness-force Bliss Supermind Mind Psyche Life Mind After plunging into the farthest limit, i.e., the lowest form, consciousness turns around to climb the steps it had descended earlier. Evolution, the inverse of 359 MODERN INDIA N THOUGHT involution, is a conscious movement. Thus, evolution presupposes involution; in fact, evolution is possible because involution has already occurred. Thus, the order of the evolutionary process is as follows: Matter Life Psyche Mind Supermind Bliss Consciousness-Force Existence The frst four in the order of evolution constitute the lower hemisphere and the last four the upper hemisphere. Evolution from the lower to the higher, i.e., from matter to spirit, is possible because each level contains within it the potentiality to attain a higher status. The uniqueness of Śr ī Aurobindo’s theory of evolution lies in its triple processes of widening, heightening, and integration. Widening signifes extension of scope (incorporation of co-existent forms and the development and growth toward higher forms); heightening leads to the ascent from the lower to the higher grade; and integration means that the ascent from the lower to the higher is not simply the rejection of the lower but rather the transformation of the lower to the higher. In other words, when life emerges out of matter, it signifes not only an ascent to a higher grade but also a transformation of matter. The same characterizes the next two, i.e., the psyche and the mind. Thus, the life, psyche, and mind modify matter, and, in turn, are modifed by it. This, however, is not enough, because mind is essentially characterized by ignorance and error. Aurobindo was aware that fnite intellect has its limits and so it is not able to grasp the integral view of reality. In Aurobindo’s words, “The intellect is incapable of knowing the supreme truth, it can only range about seeking for truth, and catching fragmentary representations of it, not the thing itself.”29 Additionally, mind, for Aurobindo, “is not a faculty of knowledge…it is a faculty for the seeking of knowledge … [it] is that which does not know, which tries to know and never knows except as in a glass darkly.”30 A creative consciousness is needed which is able to see unity as well as diversity, and is able to apprehend all relations in their totality. He terms this power of divine creative consciousness the “Supermind.” Thus, mind is only a transitional term which points beyond itself to its perfection, its destiny, the Supermind, which, in Aurobindo’s words, is “a power of Conscious-Force expressive of real being, born out of real being, and partaking of its nature and neither a child of the Void nor a weaver of fctions. It is conscious Reality 360 MODERN INDIA N THOUGHT throwing itself into mutable forms of its own imperishable and immutable substance.”31 It is culmination or the consummation of mind. The difference between the Supermind and the mind is the difference in their way of looking at reality. The Supermind has an integral outlook; it achieves a unitary picture of reality, but the mind by its very nature has a piecemeal picture. The Supermind is the link that connects the two horizons, the lower and the higher. Without the instrumentality of the Supermind, there would be neither the descent of the supramental consciousness into the mind nor the ascent to the supramental consciousness. There is continuity of growth between the mind and the Supermind as we pass through different levels of consciousness. Aurobindo refers to these levels using such terms as the “higher mind,” the “illumined mind,” the “intuition,” and the “overmind.” A Western reader is at a loss in his attempt to understand this kind of speculation. It is diffcult for him to agree with Aurobindo that the crisis of modern civilization reveals an essential weakness in the power of the human mind which can only be resolved by the emergence of something higher. Aurobindo gives us a truly teleological approach to the understanding of the nature of mind. The ascent to the Supermind is achieved through a triple transformation: The psychic, the spiritual, and the supramental. The psychic change is the removal of the veil which hides our psyche or soul; the spiritual change gives us an abiding sense of the infnite, the experience of the true nature of the self, the Īśvara, and the divine; and the supramental transformation signifes a transformation into knowledge and the emergence of gnostic being, a divinized spirit, a perfect individual who personifes integration within and without. It views everything from the perspective of the saccid ānanda and follows the command of the will of the spirit in which the laws of freedom replace the empirical laws. It does not amount to rejecting the world, but rather recognizing that matter is also brahman. It is a full life—a life of perfect freedom. The gnostic being is the return of the spirit to itself; it is the summit of evolution. Thus, the spirit is not only the source of creation but also the fnal end of realization. A divine perfection of the human being is Aurobindo’s aim. Aurobindo articulates spiritual experience in terms of an evolution of individual in relation to the absolute being, the brahman. It is at once an experience of the spiritual reality in itself, and as it manifests itself in the creative it becomes manifested in the universe. An individual contains within himself various powers of consciousness that are capable of an unlimited awareness and knowledge. These higher powers of consciousness must emerge, develop, and reach completion through an individual’s mental, vital, and physical being for the spiritual evolution to be fulflled. Descent is a necessary condition of evolution. It is an original force in the universe. In fact, ascent and integration are possible because of the descent of the consciousness. 361 MODERN INDIA N THOUGHT Concluding Ref lections From the One to the One via the Many Śr ī Aurobindo made no secret of the fact that he is the frst and the foremost a Vedāntin; thus, it is not surprising that he made the One being, the starting point of the origin, nature, and the end of the universe. For a Vedāntin the problem of the One and the Many is not, as for a scholastic philosopher, how to relate the two in an intelligible fashion, but rather how to make the Many appear out of the One. Aurobindo, on the one hand, maintains that the being or the brahman is pure existence, eternal, indefnable, and, on the other hand, attributes becoming to it. Can we rationally attribute becoming to being while maintaining that it is pure existence, etc.? Is Śr ī Aurobindo’s thesis plausible from a philosophical standpoint? Śr ī Aurobindo attempts to reconcile the two by affrming that the Many pre-exists in the One and makes the becoming the inherent power of the One. The One and the Many co-exist eternally. In response to the questions “why does the world arise?” and “why evolution?” Śr ī Aurobindo holds that creation is the sportive activity of the brahman. The brahman is self-suffcient; he does not create the world out of any desire or lack. The world for Śr ī Aurobindo is in a perpetual movement; it is the result of the delight of the brahman. Śr ī Aurobindo identifes the brahman with delight. To substantiate his metaphysics, Śr ī Aurobindo reinterprets the Śa ṃ kara’s concepts of līl ā and m āyā and establishes a positive relationship between his spiritual experience and metaphysics. He explains līl ā on the model of the rare moments of human life when one experience joy at its maximum; each person must discover the joy of delight in one’s own creation and self-manifestation. The Advaitic account eventually comes to terms with the utter inexplicability of individuation by coming to regard the many as but a product of avidyā, ignorance. The Many is the līl ā, i.e., the sport of the One; in saying this, the Advaitins emphasize that the One could not have any purpose in creating the Many. Thus, by excluding all elements of purpose from the question about the Many, the question may be modifed to become an interrogation into the “how” of the Many, rather than the “why” of the Many. The One in Advaita does not give its being to the Many; it is that which is there in the Many, indivisible and yet as if divided. Thus, the Advaitin has no choice but to conclude that the One is the only reality, and the Many is a false appearance of the One. The One and the Many belong to two different levels which are ultimately incommensurable. With his concept of “delight,” Śr ī Aurobindo provides a response to the Advaita conception that the world is m āyā or simply an appearance. The world, for Śr ī Aurobindo, is not an appearance but rather a manifestation of creative energy, the play, the joy of the brahman; it is real. The play begins with the involution, i.e., when the divine plunges into matter, inconscience, etc., and it continues in evolution until the mind evolves into Supermind. Thus, the entire theory of evolution falls into the general theory of the delight of brahman; 362 MODERN INDIA N THOUGHT it is there “only for the delight of the unfolding, the progressive execution, the objectless seried self-revelation.”32 This, in short, is the scheme and the direction of the play. Śr ī Aurobindo recognizes three aspects of the divine: The transcendental, the cosmic, and the individual. The transcendent aspect means that though the divine permeates the world, it is not exhausted by the world; the cosmic aspect signifes the reality of the world because it is the self-manifestation of the brahman; and the individual aspect is the awareness of ānanda in each individual. By emphasizing these three aspects individually and collectively, Śr ī Aurobindo offers a solution to the problem of being and becoming, the One and the Many. In Śr ī Aurobindo words: It can be said of it that it would not be the infnite Oneness if it were not capable of an infnite multiplicity; but that does not mean that the One is plural or can be limited or described as the sum of the Many: on the contrary, it can be the infnite Many because it exceeds all limitation or description by multiplicity and exceeds at the same time all limitation by fnite conceptual oneness.33 He was well aware that the fnite makes an opposition between the Infnite and the fnite and associates fniteness with the plurality and infnity with oneness; but in the logic of the Infnite there is no such opposition and the eternity of the Many in the One is a thing that is perfectly natural and possible. The absolute, the unconditioned, infnite spirit, the pure unity of being is also the creative energy which is the source of the conditioned many. There are two poises of the brahman, which Aurobindo compares to the “two poises of being,” “like the stillness of reservoir and the coursing of the channels which fow from it.”34 He observes: When we perceive Its deployment of the conscious energy of Its being in the universal action, we speak of It as the mobile active Brahman; when we perceive Its simultaneous reservation of the conscious energy of its being, kept from the action, we speak of it as the immobile passive Brahman,—Saguna and Nirguna….35 Thus, the reality of the world is the result of the creative or dynamic aspect of the brahman. The delight functions not only on the level of the divine, but also in the physical world as far as the brahman in itself is pure ānanda or bliss, and it also bestows bliss on those who become united with it. Thus, with the help of the concept of “delight,” Śr ī Aurobindo explains the relationship that exists between the human and the divine creativity. All creation, holds Śr ī Aurobindo, is self-manifestation out of delight and by the cit-śakti or the inherent conscious force, and the goal of evolution is the emergence of the superman, i.e., a form of conscious being who is superior to the human in all respects. It is with the emergence of human that the 363 MODERN INDIA N THOUGHT evolutionary process fnds its true goal. Up until this time, it seemed as though the emergence of any form of being—inorganic or organic—was determined by the initial, given conditions. But now human being is able consciously to guide the evolutionary process, there is a reversal of natural evolution. Human beings can entertain a goal and consciously pursue it. The individual, besides the transcendental and the universal, now becomes the means of evolutionary change. Here Śr ī Aurobindo’s conception of yoga makes an appearance. Yoga becomes the process by which the individual brings about the transformation of the universal. Integral emergence becomes the goal of evolution. Two processes go on simultaneously: The evolution of the outward nature and the evolution of the inner being. It is only through this double evolution that comprehensive change is possible. The evolution of nature becomes the evolution of consciousness. Instead of a mechanical gradual and rigid process, evolution becomes conscious, supple, fexible, and constantly dramatic, leading to the evolution of the spiritual man. Śr ī Aurobindo became widely known for providing an account of evolution which explains what evolution has been as well as predicting where it is heading toward. The last is the emergence of a higher form of consciousness, the supramental consciousness, in the human body. A human being is destined to grow into a superman. This is both the nisus of the evolutionary process and the goal of human spirituality. Thus, in his writings, Aurobindo attempts to preserve not only the Upaniṣadic thesis of the unity of the brahman but also the reality of the world. Whereas his Vedāntic predecessors, e.g., Śa ṃ kara and R āmānuja, tried to exclude subordinate One and Many, Aurobindo placed the many and the becoming in the very heart of the brahman, the Absolute. One, for him, was the basis as well as the source of the Many, basis not in the sense of simply being the support of the Many, but rather in the sense of being the essence of the Many. Study Questions 1. Discuss KCB’s concepts of “demand,” “denial,” and “alternation.” Discuss the signifcance of these concepts for his philosophy. 2. Discuss KCB’s alternative absolutes. According to him truth, freedom, and value are not simply alternative descriptions of the Absolute. Is his concept of “alternation” epistemic? Is it constitutive of the Absolute? If so, does it make sense to talk of triple absolutes? 3. Comment on the following: “The absolute for KCB, though of the alternative nature in the sense of ‘either-or,’ can at the same time remain as the Absolute.” Include in your answer a discussion of the KCB’s Absolute as Truth, Freedom, and Value. 4. Critically discuss Śr ī Aurobindo’s theory of evolution. What are the strengths and weaknesses of his theory? 364 MODERN INDIA N THOUGHT 5. Discuss Śr ī Aurobindo’s conception of the Absolute. Is a doctrine of evolution consistent with the thesis that the brahman alone is real? The brahman is perfect, yet it goes through the evolutionary process. Why, and how? 6. Can Aurobindo’s position—that the brahman, though one, becomes many—be justifed from a philosophical standpoint? Give reasons for his position. 7. Discuss Śr ī Aurobindo’s concept of the brahman and m āyā. Discuss some of the similarities and differences between Śr ī Aurobindo and Śa ṃ kara. Which position makes more sense to you, and why? Suggested Readings For an insightful discussion of KCB’s philosophy, readers may wish to read Kalidas Bhattacharyya, The Fundamentals of K. C. Bhattacharyya’s Philosophy (Calcutta: Saraswat Library, 1975). K. C. Bhattacharyya’s Studies in Philosophy, edited by Gopinath Bhattacharyya (Calcutta: Motilal Banarsidass, 1983), includes all the published and selected unpublished works of KCB. I have used this edition. Some of Śr ī Aurobindo’s important works are The Life Divine (New York: Dutton, 1951), Isha Upani ṣad (Calcutta: Arya Publishing Co., 1924), and The Riddle of This World (Calcutta: Arya Publishing Co., 1933). For a concise discussion of KCB’s conception of the absolute, see Bina Gupta’s “Alternative Forms of the Absolute: Truth, Freedom, and Value in K. C. Bhattacharyya,” International Philosophical Quarterly, Vol. 20, No. 3, September 1980, pp. 291–306; Steven Caplan, “Revisiting K. C. Bhattacharyya’s Concept of the Absolute and It’s Alternative Forms: A Holographic Model for Simultaneous Illumination,” Asian Philosophy, Vol. 14, No. 2, July 2000, pp. 99–115; and G. B Burch, Search for the Absolute in Neo Vedanta: K. C. Bhattacharyya (Honolulu: The University Press of Hawaii, 1976). 365 Part IX TRANSLATIONS OF SELECTED TEXTS1 Appendix A THE FOUN DATIONS The Vedas The Upaniṣads T HE FOU N DAT IONS The Vedas I The Ṛg Veda Hymn to Puru ṣa (X.90) 1 The Puru ṣa has a thousand heads, a thousand eyes, and a thousand feet. He pervades the universe on all sides and remains beyond the breadth of ten fngers. 2 All is this Puru ṣa: All that has been and all that is yet to be. The lord of immortality which becomes greater still by (sacrifcial) food. 3 Such is his glory, but he (Puru ṣa) is still greater. All creatures are onefourth of him; three-fourths are (the world of) the immortal in heaven. 4 The Puru ṣa went up with three-fourths of his nature, one-fourth remained here. From this (one-fourth), he then spread himself over into those things that eat and those that do not eat (i.e., animate as well inanimate). 5 Virāj (the female counterpart of the Puru ṣa, the male principle) was born out of him; from Virāj was born Puru ṣa again. As soon as he was born, he spreads beyond the world, behind, and before. 6 When gods prepared the sacrifce … the spring became the ghee (clarifed butter) for it, the autumn the sacred gift, and the summer the frewood. 12 [When they divided the Puru ṣa] … the brahman was his mouth, out of his two arms were the king (rājanya) made, his thighs became the vai śya, from his feet was the śudra born. 13 The moon was born from his mind; from his eyes the sun; from his mouth Indra and Agni; and from his breath, Vāyu (wind) was born. 14 From his navel came mid-air; from his head, the sky; from his feet, the earth, and the regions from his ear. They thus formed the worlds. 16 With the sacrifce, the deities sacrifced the sacrifce. The mighty ones attained the heights of heaven, the place where the ancient gods dwell. Hymn to Creation (X.129) 1 2 3 The non-being there was not, nor was there being at that time; there existed neither the air nor the sky beyond. What covered them? From where and in whose protection? And was there deep impenetrable water? Death there existed not nor deathlessness then. There was no sign of night or day. That One breathed without wind through its self-nature. Nothing else existed beyond that. At frst, there was darkness hidden by darkness; all this was an unillumined ocean. That (which) creative principle (thing) covered by the emptiness; that One was born by the power of heat. 369 T R A NSL AT IONS OF SEL ECTED TE XTS 4 5 6 7 From the primal offspring of thought, there developed desire in the beginning. Searching in their hearts through wisdom, the poets found the connection of the being in the non-being. Their severing line was stretched across: What was there below (it)? What was there above it? There were seed-bearers and powerful beings! (There was) fertile power below and potency above. Who really knows? Who can here proclaim it? From where was it born, and whence came this creation? The gods are later than the creation of this (world). So, then who does know whence it came to be (into being)? No one knows whence this creation came into being, whether it was created or not created—he who is its overseer in the highest heaven, he only knows—or, maybe, he does not know. II The Atharva Veda X.7.7–X.8.13 Hymns to Support (Puru ṣa and Prajāpati of the Ṛg Veda) X.7.7 Oh, wise man, tell me who of all is the all-pervading God, supported by whom all the worlds were frmly established by Prajāpati? X.7.8 How far did God enter within the whole universe, created by the all-pervading God, having all the forms? What part did he leave unpenetrated? X.8.13 The God Prajāpati resides within the soul. Himself unseen, he manifests himself in various shapes. With one half of his being, he produced the entire universe. How can we know of the other half? X.8.43–44 Hymns to Ātman or Soul as the Supreme One X.8.43 Men having knowledge of the brahman know God, the Lord of the soul, within the nine-door12 lotus fower and enclosed within three bonds.3 370 T HE FOU N DAT IONS X.8.44 Desireless, powerful, immortal, self-existent, who is satisfed with the delight that is his nature, lacking nothing—he is free from the fear of death who knows this ātman, which is powerful, undecaying (remains young). Hymn to Time (XIX.53)4 1 Just as a horse with seven-roped reins carries a chariot, similarly an unaging, omnipresent, all-potent deity who has thousand-fold powers of vigilance—indestructible and the Almighty—has as his wheels the entire world.… 2 Time carries along seven wheels: Seven are its centerpieces and immortality is its axle. The same time, revealing all these worlds moves as the primeval deity. 3 A flled jar has been placed upon Time. We, on the earth, see him in different ways. He illuminates all these worlds. They call him Time; he pervades the entire vast sky. 4 He alone brought together worlds (beings); it alone encompassed them. Through their father, he became their son. There is therefore no other higher majesty. 5 Time created these heavenly spheres, also these terrestrial spheres. Driven by time, what has been and what will be, and all that moves on will stand apart. 6 Time produced the very existence of creation: The sun shines in Time; creation fnds its existence in Time alone; the eyes can see only due to Time. 7 The mind, the vital breath, and the named, are placed in Time; in time all beings enjoy themselves at the very approach of Time. 8 Within Time is fervor, within Time is the greatest, in Time is the sacred truth established. Time is the lord of all; he who was the lord of all living beings (Prajāpati). 9 Sent by him, created by him, and on him, it was established; having become the sacred word, the same Time supports the highest (the brahman). 10 Time created all creatures. He created Hira ṇyagarbha (the Lord of all beings) at frst, the source of all creation. The self-existent Kaśyapa (an ancient Sage) was born from Time; heat was born from Time. 371 T R A NSL AT IONS OF SEL ECTED TE XTS The Upaniṣads I The Taittr īyā Upaniṣad Investigations about the Brahman III.1.1–6 I I I .1.1 Bh ṛgu, the son of Varu ṇa, came to his father, and said, “Sir, teach me about the brahman.” He replied, “It is food, life, sight, hearing, mind, and speech.” He said further, “It is that from which all these beings arise, that by which, after being born, they are sustained, that in which, when departing, they enter. Know him, that is the brahman.” He (Varu ṇa) performed austerities. Having performed it [he (Varu ṇa) received the wisdom.] I I I .1. 2 He learned that food is the brahman. It is from food that all these beings are born, it is from food that after being born they live, and when departing they return to it. After having learned this, he again approached his father, Varu ṇa, and said to him, “Teach me the brahman.” Varu ṇa said to him, “Seek to know the brahman through austerity, the brahman is austerity.” He (Bh ṛgu) performed austerities. Having performed austerity [he, Varu ṇa, received the wisdom]. I I I .1. 3 He learned that life is the brahman, that it is from life that all beings are born, that from life after being born they live, and when departing they return into it. After having learned this, he again approached his father, Varu ṇa, and said to him, “Teach me the brahman.” Varu ṇa said to him, “Seek to know the brahman through austerity, the brahman is austerity.” He (Bh ṛgu) performed austerities. Having performed austerity [he, Bh ṛgu, received the wisdom]. I I I .1.4 He learned that the mind is the brahman. From the mind indeed arise all these beings, being born they live by the mind, and, when departing, they enter into the mind. Having known this, he (Bh ṛgu) again approached his father Varu ṇa, and said, “Teach me the brahman.” To him (Varu ṇa) said, “Seek to know the brahman through austerity, the brahman is austerity.” 372 T HE FOU N DAT IONS He (Bh ṛgu) performed austerities. Having performed austerity [he, Bh ṛgu, received the wisdom]. I I I .1. 5 He learned that intellect is the brahman, from intellect indeed all these beings arise, being born they live by the intellect, and when departing they enter into the intellect. Having known this, he (Bh ṛgu) again approached his father Varu ṇa, and said, “Teach me the brahman.” To him (Bhr ṛgu), he (Varu ṇa) said, “Seek to know the brahman through austerity, the brahman is austerity.” He (Bh ṛgu) performed austerities. Having performed austerity [he, Bh ṛgu, received the wisdom]. I I I .1.6 He learned that bliss is the brahman, from bliss indeed all these beings arise, being born they live by bliss, and when departing they enter into bliss. This wisdom taught by Bh ṛgu and Varu ṇa is established in the highest heaven. One who knows this becomes well-established. He becomes the possessor of food and eats food. He becomes great in offspring, in cattle, in the luster of his wisdom of the brahman, and great in his fame. II B ṛhad āraṇyaka Upaniṣad II.1.1–20 II.1.1 There lived one (conceited) Bā lā ki of the Gārgya clan. He went to Ajātaśatru of K ā sī and told him, “I will tell you about the brahman.” Ajātaśatru said, “I will give you one thousand cows for this favor.” … II.1.2 The Gārgya (i.e., Bālāki) said, “The person in the yonder sun, I worship him as the brahman.” Ajātaśatru said, “Do not speak to me about him. I worship him as surpassing all beings, as their head and their king. One who worships him this way surpasses all beings; he will become the head and the king of all beings.” II.1.3–13 [Bā lā ki and Ajātaśatru exchange the same pattern of conversation with regard to the person in the moon, in lightning, in space, in the wind, in the fre, in the waters, in a mirror, in the sounds, the person here in the quarters of heavens, the person in a shadow, and the person in the body (ātman).] 373 T R A NSL AT IONS OF SEL ECTED TE XTS II.1.14 (Finally) Ajātaśatru said, “Is that all?” Gārgya said, “That is all.” Ajātaśatru said, “With all this, it (the brahman) is not known.” Gārgya said, “Allow me to be your pupil.” II.1.15 Ajātaśatru said “This is indeed contrary to practice that a brahmin should come to a k ṣatr īya expecting the latter to teach him about the brahman. However, I will impart this knowledge to you clearly.” He took him (Bā lā ki) by hand, rose, and they together approached a person who was asleep. They call him with the names “Great, white-robed, shining, Soma.” The person did not wake up. He (Ajātaśatru) woke him up by pressing him with his hands. He then woke up. II.1.16 16. Ajātaśatru said, “When this person fell asleep—this person who is full of intellect—where was it, and from where did he come back.” This Gārgya did not know. II.1.17 Ajātaśatru said, when this one (being) fell asleep, this person who is full of intelligence restrains by his intelligence, the intelligence of the sense-organs, rests in the space within the heart. He is said to be asleep when he restrains the senses. Then the breath, the speech, the eye, the ear [all these sense organs are restrained], the mind is restrained. II.1.18 As in a dream, he wanders; these are his worlds. He becomes, as it were, a great king or a great brāhma ṇa. He assumes states, high and low, as it were. As a great king, along with his people, moves about in his country according to his desire, so in a dream, along with his sense organs, he wanders about in his own body according to his desire, as he pleases. II.1.19 When he falls soundly asleep, and knows nothing, he—after coming through the 72,000 channels which extend from the heart to the pericardium, he rests in the pericardium. Just as a young man or a great king or a great brāhma ṇa rests after having reached the height of bliss, so he now rests. 374 T HE FOU N DAT IONS II.1.20 From this self, all vital breaths, all worlds, all divinities, and all beings emerge, just as a spider moves along the thread and as particles of fre come from the fre. The secret meaning of self is that it is ‘the Truth of the Truth.’ The life breaths are the truth; the self is their Truth. III Ch āndogya Upani ṣad The Nature of the Ātman (Indra-Prajāpati Dialogue) VIII.7.1–4 V I I I .7. 1 The self that is free from all sin, free from old age, death, grief, hunger, and thirst, the self whose desire is real, whose thought is real, that is the self you should try to seek, that is the self you should desire to know. He who has thus found out and who knows that self, he reaches all the worlds and all desires. Thus, said Prajāpati. V I I I .7. 2 Both the gods and the demons heard it. They said, “we seek that self, by seeking which one reaches all the worlds, and also all desires.” From the gods, Indra went to him, Virocana from the demons. The two approached Prajāpati, with fuel in hand. V I I I .7. 3 Then, for thirty-two years, the two lived there (with Prajāpati) the life of discipline of “aspirant of Brahm ā.” Then, he (Prajāpati) said to them, “Desiring what have you been living (this life of austerity)?” Then, the two (Indra and Virocana) said, “The self which is free from evil, old age, death, sorrow, hunger, and thirst, who desires the truth, who thinks of the truth, he (that self) should be sought, he should be understood. He who knows that self, reaches all the worlds and all his desires are fulflled.” That is declared to be your words, Sir. We are living [this life of discipline] desiring (to know) him (that self).” V I I I .7. 4 Prajāpati said to them (Indra and Virocana), “The self is the person that is seen in the eye. That is the immortal, the fearless (self), that is the brahman.” 375 T R A NSL AT IONS OF SEL ECTED TE XTS They asked, “But, Sir, who is the person that is seen in water and in a mirror?” He (Prajāpati) replied, “He is the same that is seen in all these.” VIII.8.1–3 V I I I . 8 .1 Look at yourself in a bowl of water and let me know if you do not see anything about yourselves.” The two looked at themselves in a bowl of water. The Prajāpati asked the two, “What do you see?” Then, the two said, “Oh, divine Sir, we see the self, (we see) a picture (of ourselves) up to the hair and nails.” V III.8.2 (As requested by Prajāpati, the two put on their best attire, and looked into the bowl of water.) “What do you see?” asked Prajāpati VIII.8.3 The two said, “Oh, divine Sir, we see ourselves dressed up in the best clothes.…” Prajāpati said, “That is the self, the immortal, the fearless, the brahman.” The two of them left with a heart full of tranquility. VIII.9.1–3 V I I I . 9.1 [Indra even before he reached the gods, understood the danger of Prajāpati’s teaching. So, he decides to return to Prajāpati.] V I I I.9.2 Indra returned with fuel in his hands … he asked, “If the body is well-adorned, the self is, well-dressed if the body is, blind if the body is blind, lame if the body is so, lame when the body is lame. This self perishes as soon as the body does. I do not see any worth in it.” V I I I.9. 3 Prajāpati said, “I will explain this further, after you live with me for additional thirty-two years.” So, did Indra. To him, then, he (Prajāpati) said. 376 T HE FOU N DAT IONS VIII.10.1–2, 4 V I I I .10.1 He (Prajāpati) said, “He who wanders about freely in a dream, is the self, the immortal, the fearless, the brahman.” Indra returned with a quiet heart. Then, but before reaching the gods, he saw problem in it. When the body is blind, the self is not blind, if the body is lame, the self is not so, it does not suffer from the defects of the body. V I I I .10. 2 This self is not killed when the body is killed, it is not lame if the body is so, yet it is as they kill him; as it were they undressed him; he experiences, as it were, unpleasantness, he even weeps as it were. I do not see any merit in this. V I I I .10. 3 [So, he decides to return to Prajāpati again.] Prajāpati said, “Live with me for an additional thirty-two years, then I will explain it further.” He (Indra) lived with him (Prajāpati) for another thirty-two years. To him, then he (Prajāpati) said. VIII.11.1–3; VIII.12.1 V I I I . 11 . 1 When a person is asleep, whole and tranquil, and does not know any dream, that is the self, the immortal, the fearless, the brahman. Indra went away with a peaceful heart. But even before reaching the gods, he saw this problem. This self does not know himself as “I am he,” nor does he know the things (around him). He appears to have been annihilated. I do not fnd any merit in it. V I I I . 11 . 2 [Again, he (Indra) returned, with fuel in his hand.] V I I I . 11 . 3 [Indra lived with Prajāpati for fve more years which amounted to one hundred and one years in all … so do people say, Indra lived with Prajāpati for one hundred and one years, the disciplined life of a seeker after sacred knowledge.] 377 T R A NSL AT IONS OF SEL ECTED TE XTS V I I I .12 .1 (Finally, Prajāpati said to Indra) Oh, Indra, this body is truly mortal. It is bound by death. Yet, it is the seat of the self which is deathless and bodiless. The embodied self is subject to pleasure and pain. There is no escape from pleasure and pain for the embodied. But they do not touch the one who is bodiless. The Brahman–Ātman Identity Thesis (Śvetaketu–Uddālaka Dialogue) VI.1.3–5, VI.8.7, VI.10.1–3, VI.13.1–3 V I .1. 3 – 5 (Uddā laka asked his son, do you know that) “by which the unheard becomes heard, the unperceivable becomes perceived, and the unknowable becomes known?” Respected sir, how can there be such a teaching? Uddā laka: “Just as by knowing one lump of clay all that is made of clay is known, the differences being only a name arising from speech, reality being only clay. Just as by knowing a nugget of gold all that is made of gold is known, the differences being only a name arising from speech, reality being only gold …” (Śvetaketu replies,) “Respected sir, I did not know this, for if they (my teachers) had known it, why would not they tell me so? Please tell me.…” V I . 8 .7 (The Uddā laka said,) “That which is the essence of all things, the world has that for its self. That is the truth, that is the self, you are that (Śvetaketu). Please teach me further.” Uddā laka said, “So be it, Oh! dear.” V I .10.1– 3 The eastern rivers fow to the east, the western to the west. They move from sea to sea, and merge into the sea and become the sea itself and do not know “I am this river,” “I am that river,” In the same manner, “all human beings here, though they come from one Being, do not know that they have come from one Being … That which is the essence of all things, the world has it for its self. That is the truth, that is the self, you are that” (Śvetaketu). Please teach me further. Uddā laka said, “So be it, Oh! dear.” VI.13.1–3 V I .13.1 “Put this lump of salt in water and come to me next morning” (the teacher said). The student did so. 378 T HE FOU N DAT IONS The teacher said, “Please bring here the salt you put in water last evening.” The student looked for it and did not fnd it since it had dissolved. V I .13. 2 He (the teacher) said, “take a sip of this water from this end. (Tell me) how does it taste.” “Salty,” (said the student). “Take a sip from the middle other end (and tell me) how is it.” “Salty,” (said the student). “Take a sip from the other end (and tell me) how is it.” “Salty,” (said the student). “Throw it away, and then come to me,” (said the teacher). He (the student) did so and said, “it is always the same.” Then he (the teacher) said, “My dear, you do not see pure Being, (but) it is indeed here.” V I .13. 3 “That which the entire world has as its subtle essence is its self. That is the truth. That is the self. you are that, Śvetaketu.” (the teacher said) …. 379 Appendix B THE NON-VEDIC SYSTEMS The Cārvāka Darśana The Jaina Darśana The Bauddha Darśana T H E N O N -V E D I C S Y S T E M S The Cārvāka Darśana I From the Play Prabodahcandrodayam1 Great Nescience: The doctrines of Lok āyata as a science are known to all everywhere, perception is the only (means of) true knowledge; earth, water, fre, and wind are the only realities; wealth and desire are the only two goals of human life. The elements are what form consciousness. There is not after-life, for death is one’s salvation. Vācaspati composed this work in accordance with our intentions, offered it to Cārvā ka. C ārvā ka, through his disciples and their disciples, multiplied the work among his disciples and their disciples. (Enter C ārvā ka and his disciple) C ārvā ka: My dear child, you know that the science of punishment (or politics) alone is science (vidyā); vārta is included within it. The three Vedas, Ṛg, Yajur, and S āma, are mere words of the cunning. In talking about the heaven, there is no special merit. See— If the person offering a sacrifce reaches heaven after the destruction of the doer, actions, and instrumental entities, then there would be many fruits in a tree that is burnt by a forest-fre. And— If heaven is attained by the animal that is sacrifced in a sacrifce, then why does not the sacrifcer slaughter his own father? And— Disciple: C ārvā ka: Furthermore, if śrāddha takes place in order to bring about the satisfaction of the dead ones, then pouring oil in a lamp which has gone off ought to increase its fame anew, which is absurd. Oh, preceptor, if food and drink were the highest goal for persons, then why do they abandon worldly pleasures and take to very diffcult penances …, take food only every sixth evening, and bear pain, etc. The ignorants prefer to abandon worldly pleasures in order to enjoy the pleasures promised in the śāstras composed by deceitful persons. Their bearing of all sufferings is due to nothing, but 381 T R A NSL AT IONS OF SEL ECTED TE XTS false hope promised by deceitful persons; they do not enjoy any of the happiness that is promised. Does one satisfy one’s hunger by eating the sweets that one conjures up in one’s mind? The dopes that are duped by cults contrived by crooks are satisfed with cakes from no man’s land! But how can fools’ restrictions—alms, fasting, rites of contrition, and mortifcation under the sun— compare with the tight embrace of a woman with large eyes, whose breasts are pressed by intertwined arms? The Disciple: Oh, teacher, the authors of the śāstras say that worldly pleasures should be abandoned since they involve suffering. Cārvā ka (laughing): This game is indeed played with the feeble minded by men who are really beasts. They say that you should throw away pleasures because they are mixed with pain. What person—who seeks his own good—throws away white and tender grains of rice just because they are covered with chaff? The Great Nescience: Yes, indeed, after a long time, I hear these well-reasoned words which give pleasure to my ears. Hey! Cārvā ka, you are my dear friend! C ārvā ka (looking around): It is His Majesty, the Nescience! (C ārvā ka goes closer to Great Nescience) Victory unto His Majesty! This C ārvā ka salutes you! II Cārvāka Refutation of Inference2 Refutation of the Naiyāyika View of Inference Now inference will be examined. What, however, is inference? “Inference is preceded by that [perception]” (Nyāya S ūtra, I.1.5). How? This is how: one apprehends, in the kitchen, through the operation of the eyes, etc., the relation between fre and smoke. This gives rise to a sa ṃsk āra, residual impressions [in the mind]; afterwards, at a later time one apprehends for the second time the mark [or smoke], after which the universal relation between them is remembered, after which there is a consideration [of the hill] as related to smoke. This causes the inference of fre [on the hill] from the mark [the smoke]. 382 T H E N O N -V E D I C S Y S T E M S If one is absent, the other is also absent, for the one precedes the other. Without the cause, the effect is not seen to have occurred. Perception is said to be the cause; in its absence, how can there be any possibility of inference? If this were possible, then it would be an example of an event being produced when there is no cause. If perception is absent, so it is said, “it is impossible to apprehend an invariable relation.” There is reason why the invariable relation cannot be proved. Is it the apprehension of a relation between two universals, or a relation between two particulars, or a relation between a universal and a particular? If it be the apprehension of a relation between two universals, that cannot be accepted because a universal is not possible [has not been demonstrated]. That a universal is not possible has already been established. Nor can it be a relation [of vyāpti] between a universal and a bare particular, for a universal is impossible [undemonstrated]. Nor is it [i.e., vyāpti] a relation between two bare particulars, for the particular fres and particular smokes are infnitely many. As we have already shown, the many particulars do not possess any common element. Even if that were possible, the infnity of particulars would still be there. If the numberlessness disappeared, then particulars would not exist. If there are no particulars, then, tell me, between whom would the relation of invariable succession be apprehended? … It may be argued that the relation of invariable succession could be apprehended in the case of a few particulars that are present at that time, but not in the case of all particulars. Then, only those particulars may function as having the relation so that one of them establishes the other. But the relation cannot obtain in the case of all particulars if there is a relation between one pair of objects, it cannot be the basis of inference with regard to another pair. That would be an unreasonable extension. If there is a visual contact between Devadatta’s eye and a jar, this would not produce knowledge of water, etc. A contact gives rise to a cognition of an object only with reference to a determinate time and place [and not at other times and places]. Refutation of an Inference whose Hetu is (based on the fact of) “Being an Effect” Because of what follows, there cannot be knowledge of what is to be inferred, for it is impossible that smoke is an effect. It cannot be considered as an effect, because the cessation of its existence is not apprehended. It cannot be said that it is that which is apprehended by perception, then (the question arises) does this perception arise by being directly perceived, or does it arise by being denied? If it is said that the cessation of smoke is directly perceived, then is smoke the object of that perception, or is it something else, or is it nothing? If the perception has smoke for its object, then this perception can establish only the existence of smoke and not its negation. 383 T R A NSL AT IONS OF SEL ECTED TE XTS If the perception is of something else, then it cannot deny the existence of smoke, since something else is its object. If it has nothing for its object, then it would be like a person who is dumb, blind, and deaf. (i.e., it cannot affrm or deny anything). 384 T H E N O N -V E D I C S Y S T E M S The Jaina Darśana I The Doctrine of Syadvāda3 XXIII. When it is integrated, an entity is without modifcations. When it is differentiated, this same entity is without substance. You brought to light the doctrine of seven modes which is expressed by means of two kinds of statements. This doctrine is intelligible to the most intelligent people. When one desires to speak of a single entity—self, pitcher, etc., —having the form of substance only, without any reference to modifcation even if they are present, it is called “without modifcations.” It has the form of pure substance. In such expressions as “this soul,” “this pitcher,” only the form of substance is acknowledged, because of non-separateness of it and the modifcations. “Differentiated” means described with distinctions on account of its capacity for different forms. The same entity then is described as non-substance, without any underlying reference to the underlying substance. This is the sense.… Thus, although an entity consists of both substance and modifcations, it has a substance-form when the substance standpoint is taken to be primary; it has a modifcation form when the emphasis on the modifcation standpoint is primary and the substance standpoint is subordinate; it has the form of both when both standpoints are emphasized.… What are these seven modes and what are these kinds of statements? When about a single entity, e.g., the soul, an enquiry concerning modifcations, existence, etc., without contradiction … a statement is made one by one with the word “somehow” in seven ways, it is called the “seven-mode doctrine.” It can be expressed as follows: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 There is a perspective from which everything exists. (Affrmation) There is a perspective from which everything does not exist. (Negation) There is a perspective from which everything exists and there is a perspective from which everything does not exist. (Affrmation and negation successively) There is a perspective from which everything is indescribable. (Simultaneous affrmation and negation) There is a perspective from which everything exists and is indescribable. (Affrmation and simultaneous affrmation and negation) There is a perspective from which everything does not exist, and there is a perspective from which it is indescribable. (Negation and simultaneous affrmation and negation) There is a perspective from which everything does exit, does not exit, and is indescribable. (Affrmation, negation, and simultaneous affrmation and negation).… 385 T R A NSL AT IONS OF SEL ECTED TE XTS We have said that the complex nature of an entity is intelligible to highly intelligent individuals.… The absolutist who is highly unintelligent, points out the contradiction in affrming the contradictory modifcations.… XXIV. When non-existence is assigned to different aspects of an entity, it is not contradictory of existence in that entity. (Similarly) existence and indescribability are not contradictories. The unintelligent absolutists have not recognized this and are afraid of contradiction. XXV. One and the same thing is eternal and non-eternal. Somehow it is of similar as well as dissimilar forms. Somehow it is both describable and indescribable, existent and non-existent. XXVIII. With the words “it certainly exists, it exists, and somehow it exists,” an entity is defned from false standpoints, by standpoints and by pram āṇas. 386 T H E N ON -V E DIC S Y S T E M S The Bauddha Darśana I The Teachings of the Buddha to Five Ascetics4 The Middle Way and the Four Noble Truths There are two extremes, O recluses, which he who has gone forth ought not to follow. The habitual practice, on the one hand, of those things whose attraction depends upon the pleasures of sense, and especially of sensuality (a practice low and pagan, fit only for the worldly-minded, unworthy, of no abiding profit); and the habitual practice, on the other hand, of self-mortification (a practice painful, unworthy, and equally of no abiding profit). There is a Middle Way, O recluses, avoiding these two extremes, discovered by the Tathāgata—a path which opens the eyes and bestows understanding, which leads to peace of mind, to the higher wisdom to full enlightenment, to Nirvaṇa. And which is that Middle Way? Verily, it is the Noble Eightfold Path. That is to say: Right Views (free from superstition or delusion)— Right Aspirations (high, and worthy of the intelligent, worthy man)— Right Speech (kindly, open, truthful)— Right Conduct (peaceful, honest, pure)— Right Livelihood (bringing hurt or danger to no living thing)— Right Effort (in self-training and in self-control)— Right Mindfulness (the active, watchful mind)— Right Rapture (in deep meditation on the realities of life). Now this, O recluses, is the noble truth concerning suffering. Birth is painful and so is old age; disease is painful and so is death. Union with the unpleasant is painful, painful is separation from the pleasant; and any craving that is unsatisfied, that too is painful. In brief, the five aggregates which spring from attachment (the conditions of individuality and its cause), they are painful. Now this, O recluses, is the noble truth concerning the origin of suffering. Verily, it originates in that craving thirst which causes the renewal of becomings, is accompanied by sensual delight, and seeks satisfaction now here, … that is to say, the craving for the gratification of the passions, or the craving for a future life, or the craving for success in this present life (the lust of the flesh, the lust of life, or the pride of life). Now this, O recluses, is the noble truth concerning the destruction of suffering. 387 T R A NSL AT IONS OF SEL ECTED TE XTS Verily, it is the destruction, in which no craving remains over, of this very thirst; the laying aside of, the getting rid of, the being free from, the harbouring no longer of, this thirst. And this, O recluses, is the noble truth concerning the way which leads to the destruction of suffering. Verily, it is this Noble Eightfold Path.… [The Buddha repeats the Noble Eightfold path quoted above.] Then with regard to each of the Four Truths, the Teacher declared that it was not among the doctrines handed down; but that there arose within him the eye frstly to see it, then to know that he would understand it, and thirdly, to know that he had grasped it; there arose within him the knowledge (of its nature), the understanding (of its cause), the wisdom (to guide in the path of tranquility), and the light (to dispel darkness from it). And he said: So long, O recluses, as my knowledge and insight were not quite clear regarding each of these four noble truths in this triple order, in this twelve-fold manner—so long I knew that I had not attained to the full insight of that wisdom which is unsurpassed in the heavens or on earth, among the whole race of recluses and Brahmins, gods or men. But now I have attained it. This knowledge and insight have arisen within me. Immovable is the emancipation of my heart. This is my last existence. There will be no rebirth for me. Thus, spoke the Blessed One. The fve ascetics glad at heart, exalted the words of the Blessed One. II There is No Soul (Saṃyutta-Nikāya, iii.66)5 The body, monks, is soulless. If the body, monks, were the soul, this body would not be subject to sickness, and it would be possible in the case of the body to say, “let my body b