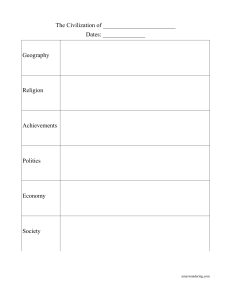

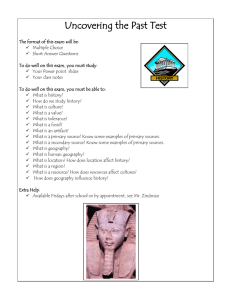

Daryl Sinclair Daryl explores the need for diverse pedagogical approaches in geography classrooms, referring to three central ideas – valuing knowledge and lived experience; presenting information precisely; and empowering students. Pedagogies for diverse classrooms: why should geography matter to me? Since the early 1900s, philosophers and educators such as John Dewey (e.g. 1938) have championed the concept of adjusting our pedagogies to address increasingly diverse classrooms. Although this is crucial in all subjects, geography finds itself occupying a special place in schools with diverse student bodies. Geography may be the only subject where a student experiences a deep enquiry into their family’s home nations, reference to areas of the world they have linguistic links with, or academic representation of identities or realities they are connected with. As geography classrooms continue to diversify culturally, linguistically, and cognitively (Shepherd, 2010), it is crucial that we adapt our pedagogical techniques accordingly. This article explores the need for diverse pedagogical approaches which empower, rather than assimilate; the goal being to support continued geographical study and success for minority students. This article will refer to three central ideas: • Valuing the knowledge and lived experience of all members of the classroom as part of the construction of knowledge. • Being precise in the presentation of information to avoid reproducing generalisations. • Empowering students to use their own knowledge to support the understanding of others. A study by the group Black Geographers (2020) found that the uptake of geography by specifically Black students was below average, while Garcia’s MA study (2018) found that all minorities were under-represented in the subject past key stage 3. Both bodies of research point to a disconnect which forms between the student and the topics presented. Many students reject the caricatures and negative stereotyping of locations they know – it is a ‘false narrative’, which they may struggle to challenge. Thus they commonly express the view that their knowledge is not valued in the construction of the class understanding of the world, and so they become disengaged. Conversely, studies of teachers across the humanities show that they fear tackling controversial topics in depth (e.g. Mills, 2013). 102 Vol 47, 3, Autumn 2022 © Teaching Geography Recent research by the OECD (Forghani-Arani et al., 2019) has confirmed that the expected increase in classroom diversity requires a shift towards increased dialogue and progressive pedagogies in the classroom. Gay (2010) states that ‘teachers’ attitudes influence students’ outcomes and can constitute obstacles for successful teaching in diverse classrooms’ (p. 52). Ladson-Billings (1995) argues that teachers’ problems in working with a diverse group of students are rooted in their belief that effective teaching is about ‘what to do’, when the real problem is rooted in ‘how we think’ (p. 30). She argues that in responsive teaching, another contemporary pedagogy targeting diverse classrooms, students’ existence must be acknowledged and their contribution valued through the pedagogy. Ladson-Billings (1995) is further supported by research conducted by Mills (2013), who confirms that the pedagogical approach of the teacher manifests itself in the students’ outcomes and the beliefs that they will go into the world with. It is clear, therefore, that a change in how we approach the construction of knowledge in geography will influence the inclusion of students, the diversity welcome in the classroom, and the outcomes for all students. Adopting pedagogies for diverse classrooms will help eradicate oppressive treatment of ‘groups’ and ‘minorities’ by recognising the value of all individuals’ contributions and the right to being viewed as both an individual and a student, thus allowing the learning environment to be inclusive of each student within each of their individual contexts. Contemporary school geography and the need for pedagogical change Figure 1 is an example of a table of data that could be used to introduce students to the country of Mali. Without further explanation, this presents the country in one dimension, and a trawl of easily accessible internet resources will also show a range of materials that deal with the issue of development uncritically, ignoring issues such as colonial exploitation, and the influences of tied aid. Such resources suggest that a country’s level of development is somehow a product of its own making, rather than the by-product of a complex globalised world. There is often no supporting guidance for teachers to ensure the narrative is engaged with criticality, and contextualised in the wider world. Geography should explicitly engage with contemporary issues through analysis of the context in which the issues came to exist and the impact they may have on the future (Lambert, 2011). The way teachers teach places can have impacts on the student’s engagement, academic success, and in part their identity formation (Andreotti, 2006; Tarozzi and Torres, 2016). Research into geography and education over the past few decades (e.g. Mills, 2013; Diallo and Maizonniaux, 2016; and Freire, 1972) Mali UK Area 1,240,190 km2 243,610 km2 Language French English Population 20.85 million 68.2 million Population density 17/km2 281/km2 Main industries Farming and agriculture, gold mining, construction and industrial manufacturing. Financial services, professional jobs (requiring a degree), technical occupations. GDP per capita US$858.92 US$40,284.64 Life expectancy 54 years 81 years N 0 km 1000 has identified the need for more progressive pedagogies which may increase the retention of minority students in geography, and their overall success. Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, 86% of people identify as White, and 14% belong to an ‘ethnic minority background’. The gender divide is 51/49 women-to-men split (House of Commons Library and ONS, 2021). How diverse are our classrooms? On a national scale, these statistics closely match and appear proportional; but the distribution of this diversity is not consistent across all schools in the UK. Communities exist together in specific places, leading to schools expressing local rather than national diversity in their student body. For example; if the statistics above were converted into ten classrooms in the UK, they would look something like Figure 2. Based on statistics from gov.uk (2021), in 2021 84.9% of all teachers in state-funded schools in England were White British. Three-quarters of teachers were women though women only accounted for two-thirds of head teachers, and there were more female than male teachers in every ethnic group. To contextualise, according to the combined 2021 censuses for England and Figure 1: Data for Mali and UK. Source: D Sinclair. Figure 2: A representation of the proportional distribution of diversity, based on gender and ethnicity, found in 10 classrooms representing the UK. Highlighting indicates an ethnic minority and each classroom comprises a principal, a classroom teacher, and 12 students. Vol 47, 3, Autumn 2022 © Teaching Geography 103 Proportional representation cannot be assumed on the classroom scale, nor can it be considered as a method to address inclusivity. However, ensuring inclusive pedagogical practices by all teachers, irrespective of their background, may provide an attainable resolution to the disengagement of diverse students in the geography classroom. What are the experiences of pedagogy in geography today? Research by Diallo and Maizonniaux (2016), and Mills (2013) suggests that teachers continue to be trained with pedagogies which target the majority and are informed by the experiences of the teacher, who statistically is most likely to be a white female. The resulting pedagogies and centring of the white experience can minimise the experiences of students from diverse backgrounds. Focusing on the geographical world through a lens which assumes a white British reader may alienate students with a global majority background while also reproducing biases and generalisations within the white student body. Moving away from generalisations and the contextual ‘majority’ can introduce more voices and perspectives into the classroom and provide opportunities for greater engagement from all students. Such engagement can lead to learning which destabilises the existing ‘norms’ and demonstrates that geography is an academic space for all students, valuing their input and respecting their identities. Teaching the ‘minority’ Popular use of the term ‘minority’ speaks to ethnic differences or labels which can be viewed or considered negatively. The term is used to denote an ethnic exception in the class; but this is not what minority means – it reflects some of the challenges of inclusively teaching a diverse class while relying on such labels. The richest students by family income in the school are a minority; the smartest high-achievers are a minority; even students with glasses may be a minority in a class. But we would not refer to them as such – we call them by their name. The term ‘minority’ may be used to identify differences which require additional work to achieve the outcomes typically reached by the majority. Students burdened with the ‘minority’ label can feel denied of the full value of their perspectives in classrooms which centre the white experience. With the shift in pedagogy suggested in this article, such as increasing critical perspectives when teaching about places and valuing diverse student voices, these differences in the achievements and learning between minorities and majorities could be reduced. What changes are occurring today? 104 Vol 47, 3, Autumn 2022 © Teaching Geography The use of appropriate pedagogies can support the education of all students, irrespective of their peers’ or teachers’ backgrounds. Groups such as Decolonising Geography empower individuals to challenge their pedagogical biases while advocating change in major organisations and exam boards. Their members include PGCE tutors, GA members, classroom teachers, school leadership and academics. Collectively, they are engaged with conference presentations, textbook reviews, and collaborative projects to support progress in the pedagogical approach to geography and the production of inclusive teaching resources. Both simultaneously, and at times as a result of the action of Decolonising Geography, organisations such as the GA and the publisher Hodder Education are engaging in diversity equity and inclusion strategies to ensure the inclusion of all students. Curriculum reviews, consultations, inviting new editors and encouraging greater contributions from previously excluded communities are beginning to bear their first fruits. These movements are in their inception but the increasing prevalence of articles and discussions about decolonising curriculums, anti-racist pedagogies, inclusive teaching, education for social justice and many others touch on the wealth of options available to teachers to consider their pedagogical approach. A brief glance over articles in TES and Teaching Geography this past year alone is testament to this (e.g. Milner et al., 2021; Sinclair and de Fonseka, 2022; Das, 2021). Though the labels may vary, progression in pedagogical approaches focused on inclusivity is clear. With a more complex and dynamic approach to teaching, students are valued and engaged as individuals. Pedagogical approaches and techniques are no longer designed for the ‘majority’ and trying to shoehorn in the ‘minority’. Strategies moving forward: support for teachers Adopting empowering language is a common means to support diverse classrooms (Anderson et al., 2021). Changes such as using ‘global majority’ rather than ‘minority’; naming specific countries and people rather than generalising as ‘Africa’, ‘poor’, or ‘developing’ (all countries are ‘developing’); and incorporating the students’ understanding into the construction of knowledge is a shift towards greater inclusivity. Pedagogies for diverse classrooms consider everyone in the classroom as a student, including the teacher, with value to add to the learning. The concept of ‘minority’ can be avoided and no single narrative will actively be centred (excluding the narrative of the subject), allowing a more inclusive pedagogical approach. If all students are considered and included in the construction of knowledge, they will all experience the same rights, agency and expectations – thus preventing the replication of generalisations or minimisation of valuable sources of knowledge. Teaching to the majority limits the outcomes for all. Conclusion As we push forward into the 2020s, there is a wealth of new pedagogies and pedagogical approaches. Web resources, blogs and journal articles on antiracist pedagogy (Sinclair and de Fonseka, 2022), culturally responsive teaching (Ladson-Billings, 1995), decolonising geography (Rackley, 2021), and international mindedness (Wright, 2022) are opportunities for teachers to provide a more inclusive space for their students. The rallying cry for inclusivity continues to echo as we see the impact it has in more and more classrooms around the world. It is important to focus on the core considerations for our students and not to get lost in the masses of names and key terms for strategies, which ultimately boil down to the points introduced at the start of this article: • Recognise and value the knowledge and experiences each of your students brings into the classroom as part of the learning process, and use them to empower students. • Avoid generalisations which are not critically engaged with and contextually explained; always seek out the specific context and people/knowledge related to the subject. • Teach for change, providing the students with skills which will serve their ability to fairly engage with the world. With these changes, we can aspire to eliminate the inequalities that are faced by students today and give every student a fighting chance to positively experience the world and develop a lifelong relationship with geography. | TG References All websites last accessed 07/07/2022. Anderson, N., Das, S., and Whittall, D. (2021) ‘Why the word ‘slum’ should not be used in geography classrooms’. Available at https://decolonisegeography.com/blog/2021/08/why-the-word-slum-should-not-be-used-in-geography-classrooms Andreotti, V. (2006) ‘Soft versus critical global citizenship education’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, 3, pp. 40–51. Black Geographers (2020) ‘Participation of Black students in geography’. Available at https://drive.google.com/file/d/117xYtq JmesJU21fUUXuFd43HwE2KHlkP/view Das, S. (2021) ‘How we can decolonise geography in schools’, TES magazine. Available at www.tes.com/magazine/teachinglearning/secondary/how-we-can-decolonise-geography-schools. Diallo, I. and Maizonniaux, C. (2016) ‘Policies and pedagogies for students of diverse backgrounds’, International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning, 11, 3, pp. 201–10, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/22040552.2016.1279526 Forghani-Arani, N., Cerna, L. and Bannon, M. (2019) ‘The Lives of Teachers in Diverse Classrooms’ OECD Education Working Paper No. 198. Available at www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=EDU/ WKP(2019)6&docLanguage=En Freire, P. (1972) Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Herder and Herder. Garcia, H. (2018) ‘Does geography have an image problem? Exploring the perceptions and attitudes of minority ethnic groups towards geography education’. Dissertation submitted for MA Geography Education, UCL Institute of Education. (unpublished) Gay, G. (2010) ‘Acting on beliefs in teacher education for cultural diversity’, Journal of Teacher Education, 61/1–2, pp. 143–52. Available at doi.org/10.1177%2F0022487109347320 Gov.uk (2021). Available at www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/workforce-and-business/workforce-diversity/schoolteacher-workforce/latest#by-ethnicity-and-role House of Commons Library Briefing (2021) Ethnic diversity in politics and public life available at: https://commonslibrary. parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn01156/ Ladson-Billings, G. (1995) ‘Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy’, American Educational Research Journal, 32, 3, pp. 465–91. Lambert, D. (2011) ‘Reframing school geography’, in Butt, G. (ed) Geography, Education and the Future. London: Continuum Press. Mills, C. (2013) ‘Developing pedagogies in pre-service teachers to cater for diversity: Challenges and ways forward in initial teacher education’, International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning, 8, 3, 219-228, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/ abs/10.5172/ijpl.2013.8.3.219 Milner, C., Robinson, H. and Garcia, H. (2021) ‘How to start a conversation about diversity in education’, Teaching Geography, 46, 2, pp. 59–60. Office for National Statistics (2021) Census data available at https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/ populationandmigration/populationestimates/bulletins/populationandhouseholdestimatesenglandandwales/census2021 Sinclair, D. and de Fonseka, A. (2022) ‘Operationalising anti-racist pedagogy in a secondary geography classroom’, Teaching Geography, 47, 2, pp. 58–60. Tarozzi, M. and Torres, C. A. (2016) Global Citizenship Education and the Crises of Multiculturalism: Comparative Perspectives. London: Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 1–22. Further reading Decolonising Geography. Available at https://decolonisegeography.com Dewey, J. (1938) Experience and Education. New York: Touchstone Books. Rackley, K. (2021) Decolonising Geography 101. Available at https://decolonisegeography.com/blog/2021/03/decolonisinggeography-101 Shepherd, J. (2010) ‘England’s schools are becoming more diverse’. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/education/ 2010/jan/20/schools-more-diverse Wright, C. (2022) International Mindedness. Available at https://www.thinkib.net/leadership/page/25142/ internationalmindedness Daryl Sinclair is the Head of Secondary and a Geography and Economics/ Politics Teacher at WABE International School, Pinneberg. Email: dsinclairwriting@ gmail.com Twitter: @dsinclair17 Vol 47, 3, Autumn 2022 © Teaching Geography 105