1. General principles of asepsis and antiseptics

Asepsis = no putrefaction

In Western Europe and USA „asepsis“ and „antisepsis“ are synonyms.

The fundamental components of aseptic procedures:

- the environment (the operating room)

- the patient

- the participants in the operation

- the instruments and other materials used

In Eastern Europe there is a difference in the basic meaning of „asepsis“ and „antisepsis“:

Asepsis (Sterilization)

• Where?: In the environment and on the surface of surgical instruments and materials

• How?: In general, by using the laws of Physics

• Why?: Prevention of surgical infection

Antisepsis (Desinfection)

• Where?: In the human body and on the skin surface (patient and participants)

• How?: In general, by using Chemical Substances

• Why?: Prevention of/ Treatment of surgical infection

Asepsis- aseptic agents and methods

- Asepsis is the practice to reduce or eliminate contaminants (e.g. bacteria, viruses, fungi and

parasites) from entering the operative field in surgery to prevent infection

- aseptic procedures concerning the environment, the surgical instruments and materials

Methods:

Steam:

- more effective than dry heat

- high temperature steam - under pressure - duration:

• 115°C - 0,5 atm. - 1 hours

• 120°C - 1,0 atm. - 45min

• 134°C - 2,0 atm. - 30 min

- heat-sensitive tape as an evidence

- steam is mainly used for sterilization of surgical cotton equipment - garments, sheets, bandagematerials, etc.

- less often used for surgical metal instruments

Steam autoclaving

- chemical indicators can be found on medical package and these change colour once the correct

conditions have been met

- color change indicates that the object inside the package has been autoclaved sufficiently

Page 1 of 269

Dry Heat

- air heated up to 160-200°C

- because dry heat can dull sharp instruments and needles, these items should not be sterilized at

temperatures higher than 180°C

- duration: 45-60min

- dry heat is mainly used for sterilization of surgical metal instruments

- devices for that type of sterilization are usually placed in the operation theatre

Gas

- most effective method of gas chemical sterilization is the use of ethylen oxide gas (ETO)

- ETO gas-sterilization period range from 3-7 hours

- used for equipment made of plastics or other polymers - surgical gloves, nasogastric tubes,

catheters, etc.

Different type of rays, etc.

- ultra-violet, infra-red rays, gamma ray sterilization

- used in plants and factories, producing single-use medical equipment - suture materials,

syringes, needles, catheters, tubes, etc.

Aseptic procedures concerning environment

- the traffic in the operation theatre must be limited

- the operation rooms should be equiped with air filters

- positive pressure ventilation

- laminar flow

- regular cleansing or floors, walls, windows, tables, etc. with antibacterial agents

- different operation rooms for „clean“ and „contaminated“ surgical procedures

Antisepsis = against putrefaction

Antisepsis- antiseptic agents and methods

- antisepsis is the prevention or/and treatment of infections by inhibiting or arresting the growth

and multiplication of germs (infectious agents)

- antiseptic procedures are concerning the patient’s preparation for operation and the surgeon’s

preparation for operation

- disinfectants includes several oxidants, halogens or halogen-releasing agents, alcohols,

aldehydes, organic acids, phenols, cationic surfactants and heavy metals

- disinfectants act by the denaturation of proteins, inhibition of enzymes or a dehydration

Antiseptic agents for the disinfection of rooms:

- surface (floor) disinfection employs aldehydes combined with cationic surfactants and oxidants

or, more rarely, acidic or alkalizing agents

- room disinfection: room air and surfaces can be disinfected by spraying or vaporizing of

aldehydes, provided that germs are freely accessible

- cetridine forte

- deconex

Page 2 of 269

Antiseptic procedures concerning environment

- the traffic in the operation theatre must be limited

- the operation rooms should be equiped with air filters

- positive pressure ventilation

- laminar flow

- regular cleansing or floors, walls, windows, tables, etc. with antibacterial agents

- different operation rooms for „clean“ and „contaminated“ surgical procedures

Antiseptic agents for disinfection of the skin or for local use (wound)

- jod-benzinum - 1% iodine solution in light benzin

- jodum/iodine/ -1%-5%-20% - alcoholic solution - tincture of iodine

- ethanol (alcohol) - 70% and 96%

- hydrogen dioxide - 3%

- iodophor compounds (povidone iodine = braunol = jodasept)

- chlorhexidine (hibitane, hibiscrub)

- antibiotics

Antiseptic procedures concerning the patient’s preparation for operation

- antibacterial shower on the night before or the day of operation

- mechanical bowel preparation

- antibiotics - in cases of current infection

- hair clipping of surgical field (the area of the planned operation)

- skin preparation in the area of the procedure with betadine or chlorhexadine

- covering the body of the patient with sterile sheets

Antiseptic procedures concerning the surgeon’s preparation for operation

- covering hair and wearing face masks

- the hands and the arms to the elbow are scrubbed

- the purpose of surgical hand scrub:

• remove dirt from nails, hands and forearms

• reduce resident and transient flora levels

• prevent fast re-growth of bacteria

- essential property of antimicrobial agent used for surgical hand scrub - antimicrobial agents

must have persistent action (also in moist environment) to inhibit bacterial growth

2. Antibiotic therapy and prophylactics in the treatment of surgical patients

Antibiotics - substances produced by microorganisms to suppress the growth of other

microorganisms

Antimicrobial agents - encompasses agents synthesized in laboratory and natural antibiotics

produced by some microorganisms (antimicrobial agent has a broader meaning than antibiotics)

Mechanisms of antimicrobial action

• bactericidal agent -> organisms are killed

• bacteriostatic agent -> organisms stop growing

• both effective as chemotherapeutic antimicrobial drugs

Page 3 of 269

Classification according to the point in the cellular biochemical pathways at which the agent

exerts its primary mechanism of action (5 major groups):

1. Inhibition of synthesis and damage to the cell wall:

- penicillins

- cephalosporins

- monobactams

- carbapenems

- bacitracin

- vancomycin

- cycloserine

2. Inhibition of synthesis or damage to the cytoplasmic membrane

- polymyxins

- polyene antifungals

3. Modification in synthesis or metabolism of nucleic acids:

- quinolones

- rifampin

- nitrofurantoins

- nitroimidazoles

4. Inhibition or modification of protein synthesis

- aminoglucosides

- tetracyclines

- chloramphenicol

- erytromycin

- clindamycin

- spectinomycin

5. Modification in energy metabolism (folic acid metabolism):

- sulfonamids

- trimethoprim

- dapsone

- isoniazid

Drug selection - factors:

1. Identification of the microorganism

• determine the possible pathogen in the infection site (wound exudates, sputum, urine, CSF,

blood,…)

• gram stain - the fastest, simplest and most inexpensive way

• other methods: agglutination, immunoelectrophoresis, direct immunofluorescence techniques

• in cases impossible to obtain a specimen - previous knowledge and experience (emperic

antimicrobial therapy)

2. Antimicrobial susceptibility of the microorganism (disk diffusion method, 18-48 hrs)

3. Bactericidal versus bacteriostatic (bacteriostatic often adequate in uncomplicated infection)

Page 4 of 269

4. Host status (age, renal and hepatic function, allergies, pregnancies, anatomical site of

infection,…)

General principles of antibiotic therapy

• goal is to achieve antibiotic levels at the site of infection that exceed the minimun inhibitory

concentration for the pathogens present

• for mild infections, mostly oral antibiotics are given

• for severe surgical infections, the most initial antibiotic therapy is given intravenously, because

the systemic response to this infection makes the gastrointestinal absorption of antibiotics

unpredictable; also in intra-abdominal infections, the GI function is often directly impaired

• Why is the patient failing to improve? (if obvious improvement not seen)

- initial operative procedure was not adequate

- initial procedure was adequate but a complication has occured

- a superinfection has developed at a new site

- the drug choice is correct but not enough has been given

- another or different drug is needed

• in surgical infections there is no specific duration of antibiotic treatment that is known to be ideal

• antibiotics generally support local host defense until the local response is sufficient to limit further

infection

• for deep-seated or poorly localized infections, longer treatment may be needed (3-5 days in

uncomplicated ones)

• a reliable guideline is to continue antibiotics until the patient has shown obvious clinical

improvement based on clinical examination and has had a normal temperature for 48 hours or

longer (signs of improvement include improve mental status, return of bowel function, resolution

of tachycardia, spontaneous diuresis)

Pharmacological description of an antimicrobial agent

I. Route of administration - oral, intramuscular, intravenous; local - spray, ointment, powder,

solution

II. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics (absorption, peak serum concentration, metabolism,

excretion)

III. Interval of administration

IV. Toxicity and side effects

V. Prophylaxis with antimicrobial agents (recommended for operations with a high risk of postoperative wound infection; or with low risk of infection, but significant consequences if infection

occurs; administered i.v. directly before operation, single dose mostly sufficient)

VI. Antimicrobial combination of 2 or 3 agents (may result in indifference, syngergism and

antagonism)

- to treat life-threatening infection

- to treat polymicrobial infection

- to prevent emergence of resistant bacteria

- to use a lower dose of one of the antibacterial drugs

- the enhance the antibacterial activity

Page 5 of 269

VII. Bacterial resistance mechanisms

- either intrinsic or acquired

- intrinsic is an inherently resistance to a specific antibiotic

- acquired resistance is due to a change in genetic composition

- molecular mechanisms by which bacteria acquire resistance:

a) decreased intracellular concentration of antibiotics, either by decreas influx or

decreased efflux (e.g. pseudomonas to beta-lactams)

b) neutralization by inactivating enzymes

- most common for antibiotic resistance

- affects all beta-lactam antibiotics

- e.g. beta-lactamases from gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria)

c) alteration of the target at which the antibiotic will act (e.g. pneumococcus to penicillin)

d) complete elimination of the target at which the antibiotic will act

Penicillins

• broadly divided into those that are stable against staphylococcal penicillinase and all others

• antistaphylococcal penicillinsa are active against methicillin-susceptible staphylococcal species,

reduced activity against streptococcal species, no activity against gram-negative rods or

anaerobic bacteria

• remaining penicillins are readily hydrolyzed by staphylococcal penicillinase -> unreliable for

treating staph infections

• all have excellent activity against other gram-positive bacteria except enterococci (variably

resistant)

Cephalosporins

• largest and most frequent used group

• commonly divided into three generations, but there are also important differences between

memebers in each generation

• first generation has excellent activity against methicillin-susceptivel staphylococci and all

streptococcal species

• no cephalosporin in any generation has reliable activity against enterococci, many even seem to

encourage enterococcal overgrowth

• only important difference between members of first generation is the half life: cefazolin has

longer half-life and ca be given every 8 hours rather than every 4 to 6

• second generation cephalosporins have expanded gram-negative activity compared to first

generation, but still lack activity against many gram-negative rods

• 2nd G not reliable for treatment for empirical treatment of hospital-acquired infections with gramnegative rods

• most important distiction within 2nd G is between antibiotics with good acitivty against anaerobes

(cefoxitin and cefotetan) and those without anaerobic activity (cefamandole, cefuroxime,

ceforanide and cefonicid); within each group are antibiotics with rel. short half life ( cefamandole

and cefoxitin) and with rel. long half life (cefuroxime, cefotetan, ceforanide and cefonicid)

• third genereration cephalosporins have greatly expanded activity against gram-negative rods

Page 6 of 269

Sulfonamides

• sulfonamide is the basis of several group of drugs

• original antibacterial sulfonamides are synthetic antimicrobial drugs that contain sulfonamide

group

• allergies to sulfonamides are common (3%)

• because sulfonamides displace bilirubin from albumin, kernicterus (brain damage due to excess

bilirubin) is an important potential side effect

• Antimicrobial sulfonamides:

- short-acting: sulfacetamide, sulfadiazine, sulfadimidine, sulfafurazole, sulfisomidine

- intermediate-acting: sulfadoxine, sulfamethoxazole, sulfamoxole, sulfanitran

- long-acting: sulfadimethoxine, sulfamethoxypyridazine, sulfametoxydiazine

- ultra-long acting: sulfametopyrazine

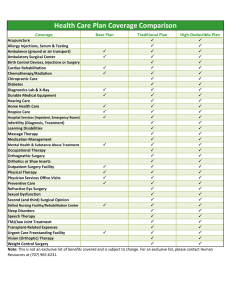

Examples of prophylactic antibiotic selection for various operations

Operation

Standard selection

Penicillin Allergy

MRSA colonization

Breast

Cefazolin

Vancomycin

Vancomycin

Cardiac surgery

Cefazolin/vancomycin

Vancomycin/gentamicin

Cefazolin/vancomycin

Hernia

Cefazolin

Gentamicin/Clindamycin

Vancomycin/gentamicin

Neurosurgery

Cefazolin

Vancomycin

Vancomycin

Plastic surgery

Cefazolin

Vancomycin

Vancomycin

Renal transplantation

Cefazolin

Vancomycin

Vancomycin

Soft tissue

Cefazolin

Vancomycin (foreign

body)

Clindamycin (no foreign

body)

Thoracotomy or

laparotomy

Cefazolin

Vancomycin

Vancomycin

Bariatric surgery

Cefazolin/metronidazole

Vancomycin/

metronidazole

Vancomycin/

metronidazole

Biliary (elective)

Cefazolin

Clindamycin/gentamicin

Cefazolin

Biliary (emergency)

Ceftriaxone

Gentamicin

Colorectal surgery

Cefazolin/metronidazole

Clindamycin/gentamicin

Cefazolin

Gynecology

Cefoxitin or cefazolin/

metronidazole

Clindamycin/gentamicin

Cefoxitin or cefazolin/

metronidazole

Urology (no entry into

urinary tract or

intestine)

Cefazolin

Clindamycin

Cefazolin

Urology (entry into

urinary tract or

intestine)

Cefoxitin

Clindamycin/gentamicin

Cefoxitin

Clean

Clean-contaminated

Page 7 of 269

Operation

Standard selection

Penicillin Allergy

Ceftriaxone/

metronidazole

Clindamycin/gentamicin

MRSA colonization

Contaminated or dirty

Gastrointestinal

(emergency)

3. Perioperative Period. Preparation of the patient for surgical treatment

Preoperative visit

- enables to patient to meet the anesthesiologist and (operating) doctor and to discuss the

procedures and possible worries

- the anesthesiologist may explain in simple term how the patient will be cared for during and

after anesthesia, as well as the ways for postoperative pain relief

- the (operating) doctor can explain the possible risks and complications of the procedure

- at last informed consent is taken

History

- should establish the patient’s surgical problem and the presence of any concurrent disease

- history of previous anesthesia, complications or any problems

- diseases of respiratory and cardiovascular systems

- a history of allergies

- familiy history of hereditary conditions associated with anesthetic problems (porphyria,

malignant hyperthermia, hemophilia, etc.)

- pregnancy — the presence of pregnancy is a contraindication for elective surgery

- a history of jaundice, particularly viral hepatitis or HIV infection

- a medication history — present therapy or drug intolerances (complete history is essential

because many drugs interact with anesthetics or anesthetic techniques)

Physical examination

- a full physical examination should be undertaken and documented in the case records

- the anesthesiologist pays particular attention to the assessment of the ease of tracheal

intubation

• the patient should be inspected for loose teeth, protruding upper incisors or dentures

• the extent of mouth opening and the degree of cervical spine flexion are also very important

• the anatomy of the face and neck of the patient should be evaluated too

• a difficult orotracheal intubation may be predicted by the inability to visualize certain

pharyngeal structures

Malampati classification

Page 8 of 269

Laboratory and other investigations — Guidelines for laboratory testing

a) Urine analysis — every patient

b) Hemoglobin concentration

• all menstruating women

• all patients over 50 years of age

• before major surgery or when significant blood loss is expected

• history of blood loss, pallor

c) Creatinine and serum electrolytes

• history of diarrhea, vomiting, metabolic disease or diabetes

• renal or hepatic disease

• patients receiving medications with diuretics, digoxin, steroids, antihypertensives

• all patients over 60 years of age

d) Liver function test

• hepatic disease

• abnormal nutritional state or metabolic disease

• history of large intake of alcohol

e) Blood sugar concentration

• all patients receiving steroids

• all patients who have diabetes or vascular disease

• all patients over 40 years of age

f)

Coagulation tests

• history of bleeding or bleeding disorders

• patients receiving anticoagulant therapy

• all patients with liver disease

g) Chest X-ray

• history or findings of cardiopulmonary disease

• all patients with malignant disease or echinococcosis

• before thoracic surgery

• all patients over 60 years of age

h) Electrocardiogram

• cardiovascular disease

• all patients with hypertension

• all patients over 40 years of age

Risk assessment

- Anesthetic risk is difficult to ascertain precisely, because it is influenced by a combination of

factors

- the ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologist) grading system is a useful and easy way for risk

assessment:

• Class 1 — a normal healthy patient

• Class 2 — a patient with mild systemic disease

• Class 3 — a patient with severe systemic disease

• Class 4 — a patient with severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life

• Class 5 — a moribund patient who is not expected to survive without the operation

• Class 6 — a declred brain-dead patient whose organs are being removed for donor

purposes

If the surgery is an emergeny, the physical status classification is followed by „E“

Page 9 of 269

Premedication

- refers to the administration of drugs in the period 1-2 hours before the induction of anesthesia

- the primary reasons for premedicating patients are:

• to relieve anxiety

• to induce sedation and anterograde amnesia

• to promote hemodynamic stability

• to minimize the chances of aspiration of acid gastric contents

• to provide analgesia and enhance the hypnotic effect of general anesthetics

• to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting

• to control oral secretions

• to control infection

- Drugs used for premedication are benzodiazepines, neuroleptics, opioid analgesics,

anticholinergic drugs, alpha2-adrenergic agonists, H2-receptor agonists

- Antibiotics are given sometimes in the immediate preinduction period for infection control in

particular patients

- Usually one or two drugs, rarely more are prescribed for premedication

4. Trauma. Traumatism. General principles and treatment

Trauma

Etiology

- physical - mechanical (compression and traction), electrical, thermal (high and low temperature),

radioactive, etc.

- chemical

- biological (bites and stings)

Pathogenesis

Effects of traumatic factor on the human body depends on:

- the type of traumatic factor - size, weight, shape, structure, physical status, chemical

structure, bacterial contamination, etc.

- anatomical and physiological status of tissues and organs being damaged

- pathological condition

Every trauma may cause necrosis, vascular and neural disorders and permanent damage of

normal structure and function of regeneration is not complete and sufficient

Clinical signs

- specific - typical for every kind of trauma

- common - can be general (different degrees, from non to life-threatening (shock)) and local,

which always presents pain, hemorrhage, lymphorrhea, infection, loss of function

- according to the integrity of covering tissues, trauma my be blunt or wounds

Page 10 of 269

Blunt trauma

- Blunt-force trauma is that trauma not caused by instruments, objects or implements with

cutting edges; but can have margins and angles

- The nature of the force applied may include blows (impacts), traction, torsion and oblique or

shearing forces

- Blunt-force trauma may have a number of outcomes:

• no injury

• tenderness

• pain

• reddening (erythema)

• swelling (oedema)

• bruising (contusion)

• abrasions (grazes)

• lacerations

• fractures

- Blunt impact injuries can be describes (in terms of force applied) as being weak (e.g. a ‚gentle‘

slap on the face), weak/moderate, moderate, moderate/severe or severe (e.g. a full punch as

hard as possible)

- The more forceful the impact the more likely that visible marks will be evident

- Tenderness is pain or discomfort experienced on palpation by another of an area of injury

- Both pain and tenderness are subjective findings and are thus dependent on (1) the pain

threshold of the individual and (2) their truthfulness

- The other features of blunt-force injury are visible effects of contact

- Reddening describes increased blood flow to areas that have been subject to trauma, but not

to the extent that the underlying blood vessels are disrupted

- Reddening must be distinguished from red bruises by its ability to blanch from finger pressure

Mechanism of blund trauma

1) Hit (impact)

2) Compression

3) Extension

4) Friction

Any injury should be described in detail according to:

- its location (anatomical posture of the body)

- its type, size, color (dating of bruises)

- signs of healing, signs of treatment (sutures)

- concomitant injuries in deeper soft tissues

Classification of blunt trauma

1) Abrasions

2) Contusions - Bruises

3) Lacerations

4) Bone fractures

5) Internal Organ injuries

Contusion (bruises)

Any mechanical trauma caused by a blow, resulting in hemorrhage beneath unbroken skin.

Clinical signs are pain, hemorrhage (subcutaneous or submucosal), local swelling and loss of

function.

Types of hemorrhage in contusion:

- hematoma - a localized mass of extra-vasated blood that is relatively or completely

confined within an organ or tissue

- petechiae - small hemorrhagic spots, of pinpoint or pinhead size

- ecchymosis - larger than 3 mm in diameter

- suffusion - a superficial hematoma

- suggilation - submucosal hemorrhage

Page 11 of 269

Morell-Lavallee’s syndrome

- specific type of blunt trauma in which the traumatic agent hits the skin in a tangential direction

- this causes rupture of the connection between the skin and subcutaneous fat tissue on one hand

and the underlying fascia on the other -> a cavity filled with lymph (and blood) appears

- local clinical signs are swelling, decreased local temperature, paleness, loss of sensitivty, later

necrotic skin

- treatment include pncture and evacuation of fluid and compressive bandage

Blunt crush of a limb

- the traumatic factor (e.g. a heavy object, vehicle) causes compression and traction on the skin

and all underlying tissues and structures

- skin integrity is preserved, but nerves, blood an lymph vessels, muscles and junctions are

ruptured and bones are fractured

- pain and blood loss result in shock

- possible complication is crush syndrome in which develops shock and acute renal failure

- clinical signs are shock, local physical symptoms - pain, paleness and/ or multiple hematomas,

decreased local temperature, total loss of sensitivity and function, bone fractures, …

Rupture

- break of any organ or soft tissues

- common are ruptures of msucles, tendons and nerves

- clinical signs of muscle rupture include pain, hematoma, loss of function, a furrow can be seen

and palpated; treatment - immobilization and suture

- rupture of a tendon - signs and treatment are similar to those of a muscular rupture and the only

difference is in the location

- clinical signs of a nerve rupture are motor disturbances (loss of ability of active motion) and

sensory disturbances (loss of sensitivity); suture is obligatory for basic nerves

Joint injuries

- Classified as sprain of a joint, subluxation and luxation/dislocation

- Joints that are commonly injured are the shoulder, interphalangeal joints, metacarpophalangeal

joint of thum, the elbow, hip and ankle

Sprain of a joint

- results from a motion greater than normal and develops a partial or complete rupture of the

capsule and ligaments, but without dislocation or fracture

- clinical signs are pain, swelling, loss of function, subcutaneous hematoma

- treatment include immobilization, compressive bandage of the joint, physiotherapy and

nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs

Page 12 of 269

Luxation (dislocation)

- It is a disarrangement of the normal relation of the bones entering into the formation of a joint

- The articular surfaces of opposing bones completely (luxation) or incompletely (subluxation) and

persistently separate

- It can be congenital, acquired or traumatic, pathologic (direct and indirect trauma, acute and

recurrent, simple and complicated; complicated by means of: a fracture accompanies the

luxation, an open luxation, nerve/vessel rupture)

- The pathological changes include luxation, rupture of a capsule, ligaments, tendons (st),

hemarthrosis and hematoma

Clinical features:

- pain, swelling and tenderness

- loss of function; active and passive motion are limited in dislocation

- loss of normal joint contour

- fixed position and spring-like resistance

- relative elongation or shortening of the limb

- neurologic injury (sometimes) — the incidence is much higher with dislocations than with

fractures

Diagnosis:

- the examination should include adequate evaluation of the joint involved, mechanism of injury,

previous injury to affected joint, remainder of the affected limb, neurovascular status, overlying

skin/soft tissues, associated injuries

- x-ray — obligatory for establishing diagnosis and before treatment

Treatment:

- anesthesia (analgesia)

- reduction - conservative or surgical (open reduction)

• a manipulation to place the bones into the proper relationship

• early/rapid reduction of the joint to: relieve/prevent ischaemic damage to the overlying soft

tissues (e.g. skin), avoid traction/ischaemic damage to nerves, prevent/relieve external

pressure effects on vascular structures, limit damage to articular cartilage

- immobilization: post-reduction, the joint should be adequately immobilized or stabilized for long

enough to allow soft tissues to heal

- physiotherapy/rehabilitation: early and appropriate joint and soft-tissue rehabilitation should be

performed to protect joint surfaces, minimize risk of recurrences, prevent post traumatic

stiffness, regain range of movement and power, regain function of affected joint or limb

Fracture

Fracture is a break in the continuity of a bone or cartilage

Classification:

1. Degree

- greenstick (one cortex is broken while the other remains intact)

- fissured fracture

- complete fracture

Page 13 of 269

2. Congenital (intrauterine) and acquired

- acquired - traumatic or pathological (produced by less force required to break a normal bone,

at the site of preexisting disease)

3. According to mechanism of fracture (direct and indirect force)

4. Closed (simple) and open (compound) fracture (in open fracture bone protrudes through the

skin)

5. According to fracture line and displacement: Linear (hair-line) fracture without deformities

(transverse, oblique and spiral) and displaced fracture with deformity of the limb (angulation,

rotation, apposition loss, overriding, impaction, distraction)

6. Multiple fracture

Healing process:

There are two types of fracture healing - primary and secondary.

Primary is a direct attempt by the cortex to re-establish itself thereby restoring mechanical

continuity.

Secondary healing can be categorized in three broad phases:

I. Inflammatory phase (hematoma and granulation tissue formation)

II. Reperative phase (fibrocartilaginous callus and bony callus fromation)

III. Remodelling phase

Fracture healing is affected by local and general factors

Local factors:

- blood supply to the fracture area

- type of bone involved and location of fracture within a particular bone

- interposition of soft tissue between fracture ends

- whether the fracture is open or closed and presence of infection within the fracture site

- gap between fracture ends

General factors:

- patient’s age

- patient’s nutritional status

- various metabolic factors

Clinical signs

- pain, swelling and tenderness

- loss of function (pain and loss of structural integrity of the limb cause loss of function)

- deformity - change in length, angulation, rotation and displacement

- attitude - the position of the fractured limb is sometimes diagnostic; the patient with a fractured

clavicle usually supports the limb and rotates his head to the affected side

- abnormal mobility and crepitus - these signs should not be sought deliberately because pain and

injury may result

Page 14 of 269

Treatment

- treatment of shock if present

- anesthesia (analgesia)

- reduction - closed (conservative) or open (surgical) with osteosynthesis

• the fracture must be restored to a normal anatomical position

• muscle spasm should be relieved with traction, analgesics, and muscle relaxants

• bones must be in apposition, properly aligned and in linear and rotatory directions, and set to

proper length

- immobilization

- physiotherapy and early rehabilitation

Abdominal trauma

- can be classified as blunt and penetrating

- penetrating trauma can be uncomplicated and complicated with damage of a hollow (peritonitis)

and/or parenchymatous (hemorrhage) organ

- the initial evaluation of a trauma patient (abdominal or other trauma) consists of rapid primary

survey aimed at identifying and treating immediately life-threatening problems - airways,

breathing, circulation, disability, exposure

- the primary goal in treatment is the identification and control of hemorrhage

- next step is the rapid examination to determine the presence and severity of neurologic injury

- level of consciousness measured by the Glasgow Coma scale score, pupillary response and

movement of extremities are evaluated and recorded

- based on motor responsiveness, verbal performance and eye opening to appropriate stimuli,

Glasgow Coma Scale was designed and should be used to assess the deoth and duration of

coma and impaired consciousness

Severe head injury - score 8 or less

Moderate head injury - score 9 to 12

Mild head injury - score 13 to 15

- the final step is to completely undress the patient and perform a rapid head-to-toe examination

to identify any injuries to the back, abdomen, perineum, or other areas not easily seen in the

supine, clothed position

Page 15 of 269

Management of a patient with an acute abdominal injury:

I. History

II. Examination

- inspection: abrasions, contusions, lacerations

- palpation: guarding, rebound tenderness

- percussion: tympanic (gastric dilatation), dull (haemoperitoneum)

- auscultation - loss of bowel sounds

- perineal examination - blood at urethral meatus, scrotal heamatoma, pelvic fracture

- exploration of the wound - to determine depth

- Nasogastric tube — reduces the risk of aspiration and decompresses stomach acids

- Urinary catheter — if urinary tract injury is suspected, only catheterise after performing

urethrography, cystography

- Evaluation of free intraperitoneal fluid — ultrasonography (US), computertomography (CT)

Indications for laparatomy

- penetrating injury traversing the peritoneal cavity or associated with hypotension

- blunt trauma with positive US or CT scan —> free intraperitoneal fluid

- blunt trauma with haemodynamic instability despite fluid resuscitation

- peritonitis

- x-ray —> free air or retroperitoneal air

Thoracic trauma

The most common life threatening chest injuries:

a) Tension pneumothorax

• airflow is unidirectional on inspiration but cannot escape during expiration due to a one-way

valve

• clinical features include: chest pain, air hunger, shock, neck vein distention, cyanosis,

deviated trachea (opposite side), reduced breath sounds

• x-ray: loss of lung markings of ipsilateral side is commonly seen

• immediate decompression by inserting a large bore needle into the second intercostal space

in the mid-clavicular line

• definitive treatment requires a chest drain

b) Open pneumothorax

• chest wall injury causes direct communication between pleural cavity and external

environment causing a pneumothorax

• immediate management inlcudes closing of the defect with sterile dressing that overlaps the

wound edges thus providing a flutter type valve effect followed by chest drain insertion

c) Flail chest

• segment of chest wall loses bony continuity with rest of the thoracic cage associated with

multiple rib fractures

• there are paradoxical movements of the chest

• management include analgesia, ventilation, intubation and chest drain

Page 16 of 269

d) Massive hemothorax

• loss of more than 1500ml of blood into the chest cavity or intercostal drain

• signs of massive hemothorax include absence of breath sounds and dullness to percussion

on the ipsilateral side and signs of hypovolemic shock

• management is resuscitation and operative hemostasis

e) Cardiac tamponade

• accumulation of pericardial fluid —> geart cannot fill —> pumping stops

• clinical signs are: venous pressure elevation, drop in the arterial pressure and muffled heart

sounds, low voltage ECG

• immediate pericardiocentesis is required

• all patients who have a positive pericardiocentesis (recovery of non-clotting blood) due to

trauma, require open thoracotomy

5. Local anesthesia

Local anesthesia

- Local anesthetics are a group of drugs which reversibly inhibit impulse generation in nerves and

other excitable membranes that utilize sodium channels as the primary means of AP generation

- Produce transient loss of sensory, motor and autonomic functions in a discrete portion of the

body

- Mode of action: local anesthetics bind to sodium channels, preventing membrane

depolarization —> block the propagation of the action potential

- Chemical structure: consist of a lipophilic group (usually a benzene ring), a hydrophilic group

(usually a tertiary amine), bound by an ester or amide linkage

- Potency: correlates with lipid solubility

- Onset of action: depends on the concentration of the local anesthetic and the pKa of the drug

- Duration of action: associated with protein binding, the tissue perfusion at the site of injection

and the type of linkage (ester or amide)

- Metabolism and excretion:

• ester local anesthetics are metabolized by pseudocholine esterase and excreted in the urine;

• amide local anesthetics are metabolized in the liver;

• very little drug is excreted unchanged by the kidneys

- Toxicity: rapid absorption of the anesthetic from the site of administration into the bloodstream

or unintentional intravascular injection raises the concentration of the drug in the blood over

safe limitis —> local anesthetics have their major toxic effects in the brain and myocardium

- Allergy: true hypersensitivity reactions to local anesthetics are quite uncommon (esters are

more likely to induce allergic reaction because they are a derivate of p-aminobenzoic acid (a

known allergen)

Drug classification

- commonly used LA can be classified as esters or amides (according to chemistry)

- they have an aromatic portion, an intermediate chain and an amine portion

- the aromatic portion determines lipophilic properties, the amine portion is hydrophilic

- esters are mostly hydrolyzes in plasma by pseudocholinesterase

- amides are destroyed mainly in the liver

a) Esters of benzoic acid

• cocaini hydrochlorium - pulv.

b) Esters of para-amino benzoic acid (PABA)

• Procaini hydrochlorium - amp. Chlorprocaine

• Benzocaine (Anaesthesium) - pulv.

Page 17 of 269

• Anaesthesol (Benzocaine + Procaine + Levomenthol)

• Tetracini hydrochlorium (Dicain)

• Proxymetacaine (Alcaine)

• Oxybuprocaine (novesine)

c)

Amides

• Lidocain - amp.

• Orofar - oromucosal spray 30ml

• Propipocaine (anaesthesie) spray

• Bupivacaine (Marcaine) - amp.

• Mepivacaine hydrochlorde (Mepivastesin) • Ultracain D-S (Articain + Epinephrine)

• Mesocain - gel

• Mesosept - spray

• Prilocaine

According to clinical use:

- can be applied by different ways: infiltration of the tissue (infiltration anesthesia), injection next

to the nerve branch (conduction anesthesia of the nerve, spinal anaesthesia of segmental

dorsal roots), or by application to the surface of skin or mucosa (surface anesthesia)

- LA are used mainly on mucous membranes in nose, mouth, tracheobronchial tree, and urethra

(topical anesthesia)

Local infiltration

- Lidocaine 0.5%-2% is often used but it is also effective in more dilute solutions

- the effect is prolonged if it is given in adrenaline solution, up to 1 in 200 000, which causes

vasoconstriction and also reduces bleeding

- no more than 3mg/kg body weight should be used, except when given with adrenaline, in

which case up to 7mg/kg body weight may be given

- Lidocaine anaesthesia lasts up to 90 min; may be extended by adding 0.5% lidocaine solution

Technique

- first, a bleb is raised in normal skin a short distance away (appr. 1 cm) —> the needle is

inserted and anaesthetic is gently injected as the tender area is approached

- initially the solution is infiltrated superficially to produce a wheal along the line of the proposed

incision

- if the exposure is deepened, infiltration is taken progressively deeper to create a field block

- the injection is given slowly to avoid pain caused by hydrostatic pressure

- each time the needle is in a new area, aspiration is performed to guard against intravenous

injection

- it is often advised to inject deeper progressively as the operation proceeds rather than attempt

a complete field block at the beginning

- the amount of anaesthetic agent used should be checked constantly to ensure the maximum

amount has not been exceeded

- patient should be asked to report pain or untoward symptoms and signs

- sufficient time (5min for lidocaine) should be allowed for the anaesthetic to act before starting

the operation

Regional anesthesia

- used when it is desirable that the patient remain conscious during the operation

- it is used most often for the surgery of the lower abdomen or the extremities

Adventages of regional anesthesia

- anesthesizing only the part of the body where surgery is being performed

- the patient remain conscious with preserved reflexes

- lung function is less affected

- suitable for one day surgery

- thromboembolic complications may be less

- low drug toxicity

- relatively inexpensive

Page 18 of 269

Spinal and epidural blocks

- spinal anesthesia is achieved by injecting a local anesthetic into the lumbar subarachnoid

space —> blocks the spinal nerve roots and doral root ganglia

- epidural anesthesia is accomplished by injecting a local anesthetic into the epidural space

- spinal and epidural anesthesia are widely used for surgery of the lower abdomen, perineum and

lower extremities

- spinal anesthesia offers better motor blockade, rapid onset of the block and is relatively easy to

perform

- complications associated with spinal and epidural anesthesia includes headache, severe

hypotension, urinary retention, meningitis, epidural hematoma and nerve injury

Peripheral nerve blocks

- the anesthetic is injected near a specific nerve or bundle of nerves to block sensations of pain

from a specific area of the body

- Nerve blocks usually last longer than local anesthesia

- They are most commonly used for surgery on the arms and hands, the legs and feet, or the

face

- Positioning of the needle during a nerve block may result in touching the nerve to be blocked

with the tip of the needle —> When this occurs, you may experience a sharp sensation like an

electrical shock in the part of the body supplied by the nerve (Be sure to let your

anesthesiologist know if you feel such a sensation)

6. Wounds — types. Surgical treatment. Primary and secondary suture.

Wound - Definition:

Wound is damage of the integrity of covering tissues (skin and mucous membranes) caused by

mechanical factors. The morphologic component, the functional disturbances and the healing

process determine the clinical chracateristics of every wound.

Classifaction of wounds by morphology:

1. Incised wound

2. Chopped wound

3. Contused wound

4. Lacerated (avulsed) wound

5. Lacerated-contused wound

6. Puncture (stab) wound

7. Bite wound

8. Gun-shot wound

9. Combined wound

- wounds can be penetrating and non-penetrating

- penetrating wounds: when there is a penetration into body cavities (cranial cavity, the peritoneal

cavity, the pleural cavity, the pericardium, the articular cavity)

- the penetrating wounds can be uncomplicated and complicated (when wounds penetrate into an

organ from the respective body cavity)

- wounds also divided according to the presence of bacterial contamination:

• clean wounds - bacterial contamination < 100 000 bacteria/gram tissue

• contaminated wounds - infection develops which can be:

- aerobic purulent - wound suppuration, sepsis and other infectious complications

- anaerobic, clostridial - tetanus, clostridial myonecrosis

Page 19 of 269

Clincal signs of wounds

1. General clinical signs

- not obligatory

- in some cases massive hemorrhage may lead to shock

- in cases of wound infection the body temperature and pulse rate are increased

- develop symptoms of toxicity - headache, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, etc.

- if there are complications, general symptoms may be result of the complication itself, e.g.

pneumothorax, hemothorax, peritonitis, hemoperitoneum, etc.

2. Local clinical signs

- two subgroups - specific and nonspecific

- specific - characteristic description of different types of wounds

- nonspecific - pain, hemorrhage, lymphorrhage, wound contamination, signs of inflammation

Diagnosis of wounds (through an assessment of the general condition of the patient and the local

status)

- cardiovascular system

- respiratory system

- CNS

- study of local clinical signs of the wound

- study of the limb for neural and/or vascular disturbances

- laboratory tests - Hb, RBC, WBC, etc.

- Instrumental investigations: X-rays of thoray, cranium; CT; US of the abdomen; vulnerography

The wound healing

- depends on many internal and extrernal factors (location, regional arterial blood supply,

presence of co-existing diseases like anemia, diabetes mellitus, hypoproteinemia,

hypovitaminosis, arterial occlusive diseases)

- reparations - replacement of highly differentiated tissues with connective tissue and scar

formation (e.g. parenchymatous organs and brain)

- regeneration - restoring pf specific tissue

- pathophysiologic reactions of organism to trauma include four main phases (overlapping)

I. Inflammation - 1hr to 3 days

II. Granulation - 1 day to 1 (2) weeks

III. Epithelialization - 1 day to 1 week

IV. Firboplasia - 3 day to 1 month

Inflammation phase

• three main processes: necrosis, hemostasis, inflammation

• necrosis of wound egdes and surrounding tissue due to traumatic factor (directly) and disturbed

blood circulation (indirectly)

• hemostasis preceds and initiates inflammation with the ensuing release of chemotactic factors

from the wound site

• inflammation starts as an aseptic process - vasodilation, neutrophils, monocytes and plasma

proteins enter the wound to destroy bacteria, foreign bodies and necrotic tissue

Page 20 of 269

• Monocytes differentiate into macrophages - consume tissue and bacterial debris, are crucial in

process of tissue repair by secreting multiple peptide growth factors with subsequent activation of

fibroblasts, endothelial and epithelial cells

Proliferative phase

• mainly fibroblast activty with the production of collagen and ground substance

(glycosaminoglycans and proteoglycans), growth of new blood vessels as capillary loops and the

re-epithelialization of the wound surface

• fibroblasts require Vit C to produce collagen

• wound tissue formed in the early part of this phase is called granulation tissue

• in latter part, there is an increase in the tensile strength of wound due to increased collagen

(type III)

• epithelialization of wound stops the risk of further contamination and moisture loss

Remodelling phase

• maturation of collagen (type I replacing type III until 4:1 ratio is achieved)

• decreased wound vascularity and wound contraction due to fibroblast and myofibroblast activity

• final outcome of wound healing is white scar formation

Healing by first (primary) intention

• usually in all wounds which are not contaminated, withouth necrosis and anatomical location and

size allow the skin continuity to be restored

• process lasts 6-8 days

• wound is surgically closed by reconstruction of the skin continuity

Healing by second intention

• after wound debrisement and preparation, the wound is left open to achieve sufficient granulation

for spontaneous closure

• caused by infection, excessive trauma, tissue loss, imprecise approximation of tissue and

bacterial contamination

Healing by third intention

• in case of large and deep wound with forming of hollow scars under the skin levels

Treatment of wounds

- The goals of treatment are:

• preventing infection

• acceleration of wound healing

• forming of thin, tiny and regular shaped scar

- treatment of wounds begins with giving first aid

- the main goals are to stop bleeding, to immobilize the patient for patient’s transportation and to

dress the wound, to give the patient tetanus toxoid, human tetanus immune globulin and gas

gangrene antiserum

Page 21 of 269

Surgical operation is performed in the following sequence:

- shaving of the hair widely around the wound

- immediate wound toilet of the skin around the wound with antiseptics (e.g. 20% Hibitan,

Hibiscrub, Decidin, Braunol, Decosept, etc.)

- in case of large injury and massive contamination, pour on plenty of clean water when you toilet

a wound

- local infiltration anaesthesia or general aneaesthesia

- use a scalpel to cut away 0.5 - 1cm of skin margins in healthy tissue

-

remove all necrotic tissue, hematoma and foreign bodies

preserve unaffected blood vessels and nerve trunks

reconstruction of vessels, tendons and nerves are made by specialists in short time

pass a ligature for the bleeding vessels

make a wound toilet with 3% H2O2 several times

Depending on the type of wound, there are different types of wound closure techniques:

- Immediate primary suture —> it is used immediately after wound toilet for fresh and noncontaminated wounds

- Delayed primary suture —> if there is opportunity for development of infection, but at the

moment of admission, there are no signs of infection

• put interrupted monofilament sutures without knot tying them

• if there are no signs of infection and fresh granulation is fromed 3-5 days later, knot the

sutures

- Temporary suture —> if the wound is large and contaminated and there is necessity of a

secondary toilet and sutures, put temporary sutures at the key points, at a larger distance from

one another

- Early secondary suture (2 weeks after injury) —> if granulation tissue is grown, there are no

signs of infection and the edges are soft, put a few interrupted sutures

- Late secondary suture (20-28 days after injury) —> when the infection is overcome, make

secondary wound toilet, excise the granulation, mobilize the wound edges and bring them

together with sutures

Types of wounds

Vulnus scissum

- incised wound

- caused by sharp-edged objects like a knife, scalpel, parts of glass etc.

- wounds have smooth edges and walls, acute angles, clean bottom, abundant bleeding from cut

vessels and marked tenderness

- there are usually no conditions for developing infection -> heal by primary intention

- example: surgical wound

Page 22 of 269

Vulnus contusum

- contused wound

- caused by blow with heavy, solid object

- irregular shape and rough edges

- there is a zone of edge’s necrosis and zone of local stupor aroun the edges

- edges are with light blue color, cold and insensitive due to refley spasm and thrombosis of blood

vessels and damage of the nerves

- edges and walls are undermined

- crushed tissues in the bottom of the wound

- hemorrhages in the form of ecchymosis and suffisions around the wound

- most severe contused wounds are caused when vehicle run over the body, or during

compression from heavy objects (crushed wounds)

- good condition to develop infection due to massive tissue necrosis, presence of blot clots and

opportunity of development of secondary necrosis

Vulnus laceratum

- lacerated wound (zerfetzt, zerfleischt)

- edges are rough, with light bleeding and zone of edge’s necrosis

- bleeding is more abundant than bleeding caused by contused wounds

Vulnus lacerocontusum

- lacerated-contused wound

- wound has signs of the two others

- traumatic factor causes compression and traction, which leads to massive damage of tissues

- example: detachement of the epicranial epineurosis (scalp) or detachment of the whole limb

(arrachement), which usually leads to hemorrhagic shock

- good conditions to develope infection

Vulnus conquassatum

- crushing wound

- injury caused by an object that causes compression of the body

- often following a natural disaster or after some form of trauma from a deliberate attack

- common concerns after an injury of this type are rhabdomyolysis (condition in which damaged

skeletal striated muscle breaks down rapidly) and crush syndrome (medical condition

characterized by major shock and renal failure)

Vulnus caesum

- chopped wound

- caused by heavy sharp-edged object, e.g. axes, hatches, swords, sable, etc.

- signs of incised and contused wounds

- signs of sabred wound are regular shape, minimal zone of local stupor, the bleeding usually is

light (in some cases abundant)

- danger of developing an infection

Page 23 of 269

Vulnus punctum

- puncture wound

- caused by an injury with knife or dagger

- similar to incised wound (smooth edges, shape - imprint of the transverse section of the sharp

object, usually abundant bleeding from cut blood vessels)

- if wound caused by injury with stake or similar objects, the wound is similar to stab-contusedlacerated wound, usually with light bleeding due to crushed vessels and their thrombosis

- opportunity for infection development is good due to lack of oxygen access in wound and

presence of foreign objects in it

Vulnus morsum

- bite wound

- bites from insects (e insectibus), animals (e animalibus), snakes and other reptiles (serpentibus)

- insect bite: dot shaped, sting in the center of wound, toxic insect’s products are introduced

causing redness and swelling, allergic reaction could be developed (especially in face and eye

lid region)

- tick bites could cause Lyme disease

- snake bites: two dots on the skin with purple colour, clinical signs are headache and vomiting,

the heart rate is accelerated, soft and shock develops; paralysis of breath and cardiac arrest

later developed due to neuro-toxicity of the poison

- mammal bites: infected lacerated-contused wounds, development of specific infections like

rabies, tetanus, glanders, etc. possible

Vulnus sclopetarium

- gun-shot wound

- big group of wounds with different pathomorphological characteristics

- bullet wounds are similar to stab wounds

- blast and missile’s wounds are similar to lacerated-contused wounds

- morphology structure of wound has three zones:

• zone of destruction -> the wound channel

• zone of immediately traumatic necrosis -> layer of necrotic tissues, which surround the wound

channel

• zone of molecular concussion (local stupor) -> layer of this zone, near the wound channel will

undergo secondary necrosis, the other part will repair

Wound management according to the WHO

Surgical wounds can be classified as follows:

- Clean

- Clean contaminated: a wound involving normal but colonized tissue

- Contaminated: a wound containing foreign or infected material

- Infected: a wound with pus present

- Close clean wounds immediately to allow healing by primary intention

- Do not close contaminated and infected wounds, but leave them open to

- heal by secondary intention

Page 24 of 269

- In treating clean contaminated wounds and clean wounds that are more than six hours old,

manage with surgical toilet, leave open and then close 48 hours later (This is delayed primary

closure)

Factors that affect wound healing and the potential for infection

• Patient:

- Age

- Underlying illnesses or disease: consider anemia, diabetes or immunocompromised

- Effect of the injury on healing (e.g. devascularization)

• Wound:

- Organ or tissue injured

- Extent of injury

- Nature of injury (for example, a laceration will be a less complicated wound than a crush injury)

- Contamination or infection

- Time between injury and treatment (sooner is better)

• Local factors:

- Haemostasis and debridement

- Timing of closure

Wound: Primary repair

- Primary closure requires that clean tissue is approximated without tension.

- Injudicious closure of a contaminated wound will promote infection and delay healing.

- Essential suturing techniques include:

• Interrupted simple

• Continuous simple

• Vertical mattress

• Horizontal mattress

• Intradermal

• Staples are an expensive, but rapid, alternative to sutures for skin closure

- The aim with all techniques is to approximate the wound edges without gaps or tension

- The size of the suture “bite” and the interval between bites should be equal in length and

proportional to the thickness of tissue being approximated

- As suture is a foreign body, use the minimal size and amount of suture material required to close

the wound

- Leave skin sutures in place for 5 days; leave the sutures in longer if healing is expected to be

slow due to the blood supply of a particular location or the patient’s condition

- If appearance is important and suture marks unacceptable, as in the face, remove sutures as

early as 3 days — In this case, re-enforce the wound withskin tapes

- Close deep wounds in layers, using absorbable sutures for the deep layers

- Place a latex drain in deep oozing wounds to prevent haematoma formation

Page 25 of 269

Wound: Delayed primary closure

- Irrigate clean contaminated wounds; then pack them open with damp saline gauze

- Close the wounds with sutures at 2 days

- These sutures can be placed at the time of wound irrigationor at the time of wound closure

Wound: Secondary healing

To promote healing by secondary intention, perform wound toilet and surgical debridement.

1. Surgical wound toilet involves:

- Cleaning the skin with antiseptics

- Irrigation of wounds with saline

- Surgical debridement of all dead tissue and foreign matter (Dead tissue does not bleed when cut)

2. Wound debridement involves:

- Gentle handling of tissues minimizes bleeding

- Control residual bleeding with compression, ligation or cautery

- Dead or devitalized muscle is dark in color, soft, easily damaged and does not contract when

pinched

- During debridement, excise only a very thin margin of skin from the wound edge

- Systematically perform wound toilet and surgical debridement, initially to the superficial layers of

-

tissues and subsequently to the deeper layers

After scrubbing the skin with soap and irrigating the wound with saline, prep the skin with

antiseptic

Do not use antiseptics within the wound

Debride the wound meticulously to remove any loose foreign material such as dirt, grass, wood,

glass or clothing

With a scalpel or dissecting scissors, remove all adherent foreign material along with a thin

margin of underlying tissue and then irrigate the wound again

Continue the cycle of surgical debridement and saline irrigation until the wound is completely

clean

Leave the wound open after debridement to allow healing by secondary intention

Pack it lightly with damp saline gauze and cover the packed wound with a dry dressing

Change the packing and dressing daily or more often if the outer dressing becomes damp with

blood or other body fluids

Large defects will require closure with flaps or skin grafts but may be initially managed with

saline packing

Page 26 of 269

7. Thermal injuries. Burns. Treatment. Chemical and radiation burns

Thermal trauma

• different kind of injuries to the body under action of high and low temperature

• classification of thermal trauma due to temperature:

• high temperature:

- Heat stroke (hyperthermia): surrounding temperature is very high and damages normal

thermoregulating process; clinical symptoms: headaches, elevated body temperature,

pulsating sound in ears, vomiting, dizziness

- Sun exposure (insolatio): excessive exposure to sunlight, clinical symptoms: dizziness,

loss of memory, tachycardia, tachypnea, death and coma may take place if not treated

immediately

- Obredanne syndrome: hyperthermia in operated patients, mainly in newborns and

pediatric age, in early hours after operation, sudden and fast increase in temperature,

reaches up to 41-42°C; Treatment includes: cooling methods, medication, intravenous

infusions, electrolyte solutions

- Burns: Tissue injury from flames, burning fumes and gases, hot fluids, hard objects and

voltage supply

• low temperature:

- general cooling - hypothermia

- freezing - cogelatio

Burns

• measured as a percentage of the total body area (affected rule of „nines“)

- Head and neck - 9%

- Upper extremity - 9%

- Anterior torso (thorax and abdomen) - 2 x 9% = 18%

- Back and lumbar region - 2 x 9% =18%

- Lower extremity with gluteal region - 2 x 9% = 18%

- Anus and perineum - 1%

• only second and third degree burn areas are added together to measure total body burn area

• While first degree burns are painful, the skin integrity is intact and it is able to do its job with fluid

and temperature maintenance

• If more than 15%-20% of the body is involved in a burn, significant fluid may be lost

—> shock may occur if inadequate fluid is not provided intravenously

• As the percentage of burn surface area increases, the risk of death increases as well:

• Patients with burns involving less than 20% of their body should do well

• those with burns involving greater than 50% have a significant mortality risk

• burn location is important: if burn involves face, nose, mouth or neck there is a risk that there will

be enough inflammation and swelling to obstruct the airway and cause breathing problems

Page 27 of 269

Burn classification

Based on the depth of injury to dermis and underlying structures:

- first-degree burn (superficial):

• redness (hyperemia) and edema of skin

• symptoms disappear once the skin cells are shed

• usually heal within three to six days

• mostly treated with home care (soak wound in cool water for five minutes or longer, take

pain relief, apply aloe vera or cream to soothe the skin, use an antibiotic ointment)

• don’t use ice, can make damage worse

• never apply cotton balls, can increase risk of infection

- second-degree (partial thickness):

• bullosa and blisters are seen on skin surface

• some blisters pop open, causing a wet appearance

• frequent bandaging to prevent infection

• some take longer than 3 weeks to heal, most heal within 2-3 weeks

• emergency treatment if burns affect face, hands, buttocks, groin, feet

- third A degree: distribution of necrosis on whole epidermis and part of dermis

- third B degree: total necrosis of all the skin in burned region

- fourth-degree: involves underlying subcutaneous tissue

Degree of burns

Depth of tissue damage

Symptoms

Healing process

1st degree

• Healing within 3–6

• Superficial layers of the • Pain

(superficial burn)

epidermis

days without scarring

• Erythema

• Swelling

• The burn wound

blanches on

applying

pressure and

refills rapidly

2n

2a

(superficial

de partialgr thickness

ee burn)

d

2b (deep

partialthickness

burn)

• Epidermis and upper

layers of the dermis;

dermal appendages

(hair follicles, sweat,

and sebaceous glands)

are spared

•

•

•

•

Pain

• Healing within 1–3

Erythema

weeks with

Vesicles/bullae

hypopigmentation/

The burn wound

hyperpigmentation

blanches on

but without scarring

applying

pressure and

refills slowly.

• Deeper layers of the

dermis

• Minimal pain

• Healing takes 3

weeks or longer and

• Mottled skin

with red and/or

results in scar

white patches

formation

• Vesicles/bullae

• The burn wound

does not

blanch on

applying

pressure.

Page 28 of 269

3rd degree (full

thickness burn)

• Epidermis, dermis, and

subcutaneous tissue

• No pain

• The burn does not

heal by itself

• Tissue necrosis

with black,

white, or gray

leather-like skin

(eschar)

• No vesicles/

bullae

• The burn wound

does not

blanch on

applying

pressure

4th degree

• Deeper structures

(muscles, fat, fascia,

and bones

• Charred tissue

• The tissue is dead

and requires

amputation

Phases of burn injuries:

• 1st phase: Phase of thermal shock - from start to 72 hours; plasmorrhea in region of burns and

outside them which leads to sudden decreased plasma volume, hemoconcentration and

oligoanuria

• 2nd phase: Phase of toxicoinfection - betw. 3-15th days, temperature period starts with septic

temperatures and inflammatory degenartive changes of body organs

• 3rd phase: Phase of healing - 15-28th day, imporved general condition, normal temperature,

decreased inflammatory process, necrotic skin is changed with fresh granulated tissue,

epithelialization of wound edges

• 4th phase: Phase of early cachexia - after 28th day, only in 3rd and 4th degree burns

• 5th phase: Phase of complications from burns - functional dysfunction of body organs, progress

of contractions, keloids and other morphological changes are complications of burns

- airway injury must be suspected with facial burns, singed nasal hairs, carbonaceous sputum and

tachypnea

- progressive hoarseness is a sign of impending airway obstruction

Clinical features

- Clinical features of shock (e.g., hypotension, poor urine output)

- Clinical features of ARDS (e.g., dyspnea)

- Inhalation injury should be suspected when any of the following are present:

• History of being trapped in a confined space

• Facial burns, singed eyebrows and/or nose hair, evidence of soot on the face or in the

airway

• Stridor, dysphonia

• Extensive burns

- In case of circumferential burns around limbs → compartment syndrome: clinical features of

acute limb ischemia (e.g., weak/absent pulse, paresthesia, pallor in the affected limb)

- In case of circumferential burns around abdomen → abdominal compartment syndrome:

impaired function of nearly every organ system (e.g., oliguria, acute pulmonary

decompensation, hypoperfusion) and signs of increased intraabdominal pressure (jugular

venous distension, hypotension, tachycardia)

Page 29 of 269

Treatment of Burns

Managing of a burned patient

• airway control

• breathing and ventilation

• circulation

• disability- neurological status

• exposure with environmental control

• fluid resuscitation

Treatment of burns is specific for each phase of the disease and is local and general

Local treatment:

• includes cleaning by physiological serum

• small damaged tissue is cleaned with forceps

• any fluid must be aspirated

• depends on type of wound, wether the dressing should be done or to be left exposed

• to remove or leave blisters is controversal

• washing burn wound with chlorhexidine solution is ideal

• for initial management of minor burns that are superficial or partial thickness, dressings with a

non-adherent material are often sufficient

• antiinflammatory and adequate pain relief must be provided

• plastic surgical method of treatment

Management based on degree

1st and 2nd-degree burns

- Irrigation

- Topical moisturizers (e.g., calamine lotion) or aloe vera-based gels: relieve symptoms of 1stdegree burns

- Consider antiseptic ointments (e.g., silver sulfadiazine, mafenide) or topical antibiotics

(bacitractin; triple antiobitic ointments are a combination of bactracin neomycin, polymyxin B)

- For periorbital or periocular burns, topical antibiotics (e.g., bacitracin, neomycin, or

erythromycin) are preferred over silver sulfadiazine, which may be irritating and cause ocular

toxicity

- Deroofing bullae/vesicles

- Dressing is indicated in partial thickness (2nd-degree) burns.

3rd and 4th-degree burns

- Early debridement of burnt, necrotic tissue

- Method of tissue coverage varies depending on the specific burn characteristics; Options

include:

• Free skin grafts (split-thickness or full-thickness)

• Flap reconstruction with free or pedicled flaps

- Topical antibiotics (e.g., silver sulfadiazine, bacitracin, neomycin)

Page 30 of 269

General treatment:

• includes intravenous infusion, analgesics, hemotransfusion, antibiotics and symptomatic

treatment

• intravenous infusion

- if more than 15-20% of the body involved in a burn, significant fluid may be lost

-> shock may occur if inadequate fluid

- the „Parkland formula“ estimates the amount of fluid required in the first few hours of care

following a burn: fluids for 24 hours = (4 x kg x % of burn) -> the first 50% given in the first

8 hours and the second 50% over the following 16 hours

- example: patient with 80kg with 25% burn -> 4 x 80kg x 25 = 8000ml fluid in first 24 hours

Electrical trauma (electrocution) divided into:

- atmospheric electricity (fluminatio)

- electrical current: (a) general damage - electrocutio (b) local burn - electrocombustio

Four stages in electrical trauma:

I. muscle spasm without loss of consciousness

II. muscle spasm with loss of consciousness

III. loss of memory and severe respiratory and hemodynamic damage

IV. clinical death

- complications occur in up to 30% of patients with high-voltage injury

- CNS effects such as cortical encephalopathy, hemiplegia, and brainstem dysfunction have been

reported up to 9 months atfer injury

- others report delayed peripheral nerve lesions characterized by demyelination with vacuolization

and reactive gliosis

Chemical burns

- caused by acids or bases

- common products causing chemical burns are: car battery acid, bleach, ammonia, denture

cleaners, teeth whitening products, pool chlorination products,…

- groups at highest risk are infants, older adults and people with disabilities —> may not be able

to handle chemicals properly

- most acids produce a coagulative necrosis by denaturing proteins, forming a coagulum

(e.g. eschar) that limits the penetration of the acid

- bases typically produce more severe injury - liquefactive necrosis

-> involves denaturing of proteins as well as saponification of fats, doesn’t limit tissue penetration

- severity of burn related to a number of factors, including the causing agent, concentration, length

of contact, physical form of agent, area/location of contact (swallowed, inhaled, open wounds or

intact skin)

- classification according to the exten of the injury and the depth of the burn itself:

• first degree burn: injury to the epidermis (superficial burn)

• second degree burn: injury to the dermis (partial thickness injury or dermal injury)

• third degree burn: injury to the subcutaneous tissue (full thickness injury)

Page 31 of 269

- common symptoms:

• blackened or dead skin, which is mainly seen in chemical burns from acid

• irritation, redness, or burning in the affected area

• numbness or pain in the affected area

• loss of vision or changes in vision if chemicals have come in contact with eyes

- longterm effect of caustic dermal burns is scarring

- esophagal and gastric burns can lead to stricture formation

Emergency departement care

- complete removal of offending agent (decontamination) — rinsing under running water for 10-20

min (first aid, even before seeking medical care; if chemical came in contact with eyes, rinse

eyes immediately for at least 20min)

- using litmus paper to measure the pH of the affected area or the irrigating solution is useful

- medication have a limited role in most chemical burns

- topical antibiotic therapy is recommended for dermal and occular burns

- pain medication is important

Radiation burns

- = damage to the skin or other biological tissue as an effect of radiation

- most common type of radiation burn is caused by exposure to UV light (e.g. sun)

- can also be caused by radiation therapy, exposure to high frequency microwaves or radio

waves, and exposure to nuclear energy

- Gamma rays can cause deep tissue gamma burns, while beta particles cause shallower beta

burns, which usually only harm the skin’s surface

- the extent of the damage is often based on the intensity of the radiation, and the amount of time

that the body is exposed to it

Specific types of radiation burns

Radiation Dermatitis

- = radiation burns caused by radiation treatment for cancer

- can be acute and chronic

- acute radiodermatitis occurs shortly following radiation therapy and may cause redness of the

skin and blistering

- chronic radiodermatitis is often dormant for a long period of time, after which carcinomas and

skin reactions develop

Fallout burns

- = radiation burns that are a result of nuclear bomb blasts

- lethal to those within a certain radius of the blast, usually a few miles (body tissues and clothing

are incinerated within milliseconds) — those farther away may experience charring of the skin

and severe internal burns

- radiation from these bombs can affect a wide area, and may cause cancers and deformities in

people that otherwise show no sign of radiation burns

- beta burns are frequently the result of exposure to radioactive fallout

- radiation from bombs has also been known to cause brain death, where the patient drops dead

days later without warning

- Sepsis and radiation sickness can also develop without warning

Page 32 of 269

Treatment

- radiation burns on the skin should be kept moisturized, clean and covered

- bathing should be done in warm water, and skin shuld be carefully patted dry, to avoid tears and

injuries

- sunlight should be avoided and patients should wear loose fitting clothing or bandages over the

affected area

8. Frostbite. Classification by degrees. Treatment

Definition:

A frostbite is a severe localized tissue injury due to freezing of interstitial and cellular spaces after

prolonged exposure to very cold temperatures.

Pathophysiology:

- Damage occurs via direct cold-induced cell death as well as delayed inflammation from

reperfusion injury

- Starts with vasoconstriction which later turns into vasodilation

- Electrolyte flux can also occur if intracellular ice crystals form

Classification:

I. First degree:

- Numbness, erythema, edema

- Possible development of white or pale plaques

- No blistering or tissue infarction

II. Second degree: