Effective Instruction in Turnaround Schools: State Innovations

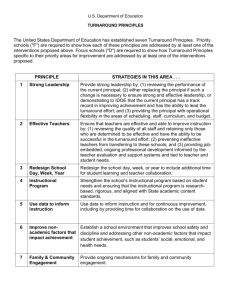

advertisement