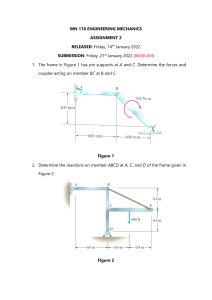

IF1203 Macroeconomics BSc Banking and International Finance BSc Accounting and Finance BSc IFRM BSc Finance Live session week 4: Fiscal policy a.chrystal@city.ac.uk Main points of the lecture • Fiscal policy is about shifting AD to stabilize real GDP….by changing G or taxes…..but governments have many other objectives! • Active fiscal fine tuning was the key policy to come out of the Keynesian revolution and was used actively up to the 1970s. • However, fiscal fine-tuning went out of fashion and fiscal policy became more about planning the size of G and then financing that over the business cycle. • The 2008/9 crisis changed all that, at least in the short-term, as fiscal stimulus packages were used to help offset the recession. (Gross tuning instead of fine tuning) • However, big deficits then became the problem and many governments embarked on spending cuts and/or tax rises. • These austerity policies are still a source of controversy. • The Covid crisis and the energy crisis have been associated with large government budget deficits and growing public debt. • BUT energy prices are falling, and fiscal deficits are shrinking, so what will policy makers do next? SRAS SRAS C A B B A C AD Output Gap Output Gap Y0 [i]. A Recessionary Output Gap Y* Real GDP Y* Y1 [ii]. An Inflationary Output Gap Demand shocks AD Real GDP SRAS SRAS C C B B A A AD AD Y0 [i]. A Recessionary Output Gap Y* Real GDP Y* Y1 [ii]. An Inflationary Output Gap Supply shocks Real GDP Fiscal policy in reality • Monetary and fiscal policies can both be used in principle to shift AD. We look at monetary policy in week 6. • BUT governments had generally abandoned use of taxes and spending for fine tuning. Labour Prime Minister Jim Callaghan said in 1976: “We used to think that you could spend your way out of recession and increase employment by cutting taxes and boosting Government spending. I tell you in all candour that that option no longer exists, and that insofar as it ever did exist, it only worked on each occasion since the war by injecting a bigger dose of inflation into the economy, followed by a higher level of unemployment as the next step. Higher inflation followed by higher unemployment.” • So, fiscal fine tuning was abandoned and interest rate policy became the main short-term adjustment tool. Though fiscal policy was used to offset major crises (eg the GFC, the Covid pandemic and the energy crisis: Gross tuning.) Why did we give up on fine tuning? • Expenditure changes are very hard to agree once plans have been announced and commitments may have been made several years ahead. • Tax rates can be changed but not much more than once a year and governments tend to make longer term commitments in their election manifesto….eg “we will not raise income tax in this parliament” • Fiscal policy is subject to several important lags: • The information lag: we do not know where we are let alone where we have been recently. • The decision lag: it takes time to interpret the data on the state of the economy and then to decide what to do about it. • The execution lag: once we have decided what to do it takes time to do it. • The implementation lag: once a policy has changed it takes a long time for the full effect to be felt. Why fine tuning with fiscal policy might not work • Time lags are variable and uncertain. • The economy is subject to changing and uncertain shocks. • With all the time lags involved, the impact of the policy change may be destabilising rather than stabilising. • By the time the impact is felt the world may have changed. • The evidence for UK in 1950s and 1960s is that, while the Government was trying to stabilise, the impact of its action was destabilising. Ideal policy timing GDP Growth Rate Time Policy works with a lag so may add to instability GDP Growth Rate Time 1900-01 1902-03 1904-05 1906-07 1908-09 1910-11 1912-13 1914-15 1916-17 1918-19 1920-21 1922-23 1924-25 1926-27 1928-29 1930-31 1932-33 1934-35 1936-37 1938-39 1940-41 1942-43 1944-45 1946-47 1948-49 1950-51 1952-53 1954-55 1956-57 1958-59 1960-61 1962-63 1964-65 1966-67 1968-69 1970-71 1972-73 1974-75 1976-77 1978-79 1980-81 1982-83 1984-85 1986-87 1988-89 1990-91 1992-93 1994-95 1996-97 1998-99 2000-01 2002-03 2004-05 2006-07 2008-09 2010-11 2012-13 2014-15 2016-17 2018-19 2020-21 2022-23 2024-25 2026-27 Total Spending and Total Revenue (as percent of GDP) 1900 to 2027 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 revenue spending Total government spending and receipts (% of GDP) 1948 to 2027 60 Public sector current receipts 55 Total managed expenditure 50 45 40 35 30 25 1948 1952 1956-57 1960-61 1964-65 1968-69 1972-73 1976-77 1980-81 1984-85 1988-89 1992-93 1996-97 2000-01 2004-05 2008-09 2012-13 2016-17 2020-21 2024-25 1900-01 1902-03 1904-05 1906-07 1908-09 1910-11 1912-13 1914-15 1916-17 1918-19 1920-21 1922-23 1924-25 1926-27 1928-29 1930-31 1932-33 1934-35 1936-37 1938-39 1940-41 1942-43 1944-45 1946-47 1948-49 1950-51 1952-53 1954-55 1956-57 1958-59 1960-61 1962-63 1964-65 1966-67 1968-69 1970-71 1972-73 1974-75 1976-77 1978-79 1980-81 1982-83 1984-85 1986-87 1988-89 1990-91 1992-93 1994-95 1996-97 1998-99 2000-01 2002-03 2004-05 2006-07 2008-09 2010-11 2012-13 2014-15 2016-17 2018-19 2020-21 2022-23 2024-25 2026-27 UK Public Sector Net Borrowing (percent of GDP) 1900 to 2027 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 -5 -10 Fiscal policy effects take time so policy makers need to forecast where the economy would be if policy did not change ■There are time lags involved in both in both fiscal and monetary policy having an impact on output and inflation. ■So policy makers have to form some kind of forecast to help them decide what needs to be done. ■Sometimes this is easy, like when a lockdown was imposed, but at other times it is hard to get the forecast right. ■Forecasts have tended to assume in the medium term that the economy will return to the previous trend. ■This has led to over-optimistic growth and productivity forecasts (especially) since the GFC. UK GDP growth: successive forecasts Fiscal: £ billion (unless otherwise stated) Economy: Percentage change on previous year (unless otherwise stated) 10 5 0 -5 -10 -15 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 June 2010 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 Successive forecasts 2018 2019 2020 2021 November 2022 2022 2023 2024 Outturn data 2025 2026-272027-28 Fiscal: £ billion (unless otherwise stated) Economy: Percentage change on previous year (unless otherwise stated) Productivity (output per hour) growth rate: Forecast and outturn. 3 2,5 2 1,5 1 0,5 0 -0,5 -1 -1,5 -2 -2,5 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 June 2010 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 Successive forecasts 2018 2019 2020 2021 November 2022 2022 2023 2024 Outturn data 2025 2026 2027 Fiscal: £ billion (unless otherwise stated) Economy: Percentage change on previous year (unless otherwise stated) Business Investment (latest Nov 2022) 20 15 10 5 0 -5 -10 -15 -20 -25 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 June 2010 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 Successive forecasts 2018 2019 2020 2021 November 2022 2022 2023 2024 2025 Outturn data 2026 2027 UK current budget deficit, % of GDP Fiscal: £ billion (unless otherwise stated) Economy: Percentage change on previous year (unless otherwise stated) 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 -2 -4 2008-09 2010-11 2012-13 June 2010 2014-15 2016-17 Successive forecasts 2018-19 2020-21 November 2022 2022-23 2024-25 Outturn data 2026-27 Some useful terminology ■The cyclically adjusted budget deficit is what the deficit would be if the economy was at potential GDP (or full employment) ■It is also called the structural budget deficit. ■The primary budget deficit is the difference between spending and receipts when the debt interest is excluded from the spending. Fiscal: £ billion (unless otherwise stated) Economy: Percentage change on previous year (unless otherwise stated) Cyclically adjusted current budget balance (percent of GDP) 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 -2 -4 2008-09 2009-10 2010-11 2011-12 2012-13 2013-14 2014-15 2015-16 2016-17 2017-18 2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22 2023-24 2023-24 2024-25 2025-26 2026-27 2027-28 June 2010 Successive forecasts November 2022 Outturn data So what is the problem with public debt? ■If the public debt gets “too large” then it may become hard to sustain. ■The interest on the debt may put a strain on the rest of the public finances….BUT for most governments interest rates have been low……until very recently. ■The outcome may depend on who holds the debt. ■Domestically held debt may be easier to manage than debt held overseas. ■Net debt is what matters not gross debt, as many governments also have large asset stocks. ■THUS how much debt is too much varies from place to place and from time to time. ■NOTE: In the UK the “National Debt” is the debt of the central government (mainly to domestic investment funds) and not the debt of the country to the rest of the world. Fiscal: £ billion (unless otherwise stated) Economy: Percentage change on previous year (unless otherwise stated) UK public sector net debt, % of GDP Successive forecasts (as of November 2022). 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 2008-09 2010-11 2012-13 June 2010 2014-15 2016-17 Successive forecasts 2018-19 2020-21 November 2022 2022-23 2024-25 Outturn data 2026-27 UK public sector debt interest, £billion Successive forecasts. Fiscal: £ billion (unless otherwise stated) Economy: Percentage change on previous year (unless otherwise stated) 160 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 2008-09 2009-10 2010-11 2011-12 2012-13 2013-14 2014-15 2015-16 2016-17 2017-18 2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22 2022-23 2023-24 2024-25 2025-26 2026-27 2027-28 June 2010 Successive forecasts November 2022 Outturn data The Debt Crisis in Greece Greece: government debt to GDP ratio, 1980-2023 Greece: 10 year government bond yield. Greece: government spending as % of GDP; 1995-2023 Greece: government budget deficit as % of GDP. 1995-2021 The UK’s self-inflicted financial crisis of September-October 2022. ■ Liz Truss become UK Prime Minister on 6th September after promising to cut taxes and stimulate economic growth. She appoints Kwasi Kwarteng as Chancellor of the Exchequer (Minister of Finance). ■8th September she announces a scheme to limit energy price rises (potentially big spending). ■23rd September Kwarteng delivers a “mini budget” with £45 billion of tax cuts…..but with no OBR assessment and having fired the head of HM Treasury. ■26th September the £ hits an all-time low against the $. ■28th September the Bank of England intervenes to stop the value of GILTS falling with up to £65 billion intervention…..the drop in gilts values was threatening solvency of major pension funds. ■29th September Truss says sticking to plans and assessment to be released on 23rd November. ■3rd October U-turn on cuts to top rate income tax. ■10th October assessment of budget brought forward to 31st October. ■11th October Bank of England announces wider intervention in bond market. ■12th October further Truss speech on “no plan to change” . ■14th October Truss sacks Kwarteng and drops corporation tax cut. ■17th October Hunt reverses most of mini-budget measures. ■20th October Truss quits as Prime Minister…….markets recover. Truss and the Markets: UK and US 30 year bond yields 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 31.12.2021 31.01.2022 28.02.2022 31.03.2022 30.04.2022 31.05.2022 UK 30yr 30.06.2022 US 30yr 31.07.2022 31.08.2022 30.09.2022 31.10.2022 £/$ Exchange Rate 1,4 1,35 1,3 1,25 1,2 1,15 1,1 1,05 1 31.12.2021 31.01.2022 28.02.2022 31.03.2022 30.04.2022 31.05.2022 30.06.2022 31.07.2022 31.08.2022 30.09.2022 31.10.2022 Governments have many aims in their actual fiscal policies: The Autumn Statement 2022 comes at a time of significant economic challenge for the UK and global economy. Putin’s illegal war in Ukraine has contributed to a surge in energy prices, driving high inflation across the world. Central banks are raising interest rates to get inflation under control, which has pushed up the cost of borrowing for families, businesses and governments. Growth is slowing and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) expects a third of the global economy to fall into recession this year or next. This comes against a backdrop of higher levels of government debt due to the economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and current energy crisis. Debt interest spending is now expected to reach a record £120.4 billion this year. These factors have contributed to a significant gap opening between the funds the government receives in revenue and its spending. The government’s priorities are stability, growth and public services. Economic stability relies on fiscal sustainability – and the Autumn Statement sets out the government’s plan to ensure that national debt falls as a proportion of the economy over the medium term. This will reduce debt servicing costs and leave more money to invest in public services; support the Bank of England’s action to control inflation; and give businesses the stability and confidence they need to invest and grow in the UK. To achieve this aim, the government has reversed nearly all the measures in the Growth Plan 2022. The Autumn Statement sets out further steps on taxation and spending, ensuring that each contributes in a broadly balanced way to repairing the public finances, while protecting the most vulnerable. The government’s approach to delivering fiscal sustainability is underpinned by fairness, with those on the highest incomes and making the highest profits paying a larger share. The Autumn Statement reduces the income tax additional rate threshold from £150,000 to £125,140, increasing taxes for those on high incomes. Income tax, National Insurance and Inheritance Tax thresholds will be maintained at their current levels for a further two years, to April 2028. The government will also reduce the Dividend Allowance and Capital Gains Tax Annual Exempt Amount. Businesses must also pay their fair share. The Autumn Statement fixes the National Insurance Secondary Threshold at £9,100 until April 2028. The government will implement the OECD Pillar 2 rules, to deliver a global minimum corporate tax rate of 15%. R&D tax credits will be reformed to ensure public money is spent effectively and best supports innovation. The Autumn Statement sets out reforms to ensure businesses in the energy sector who are making extraordinary profits contribute more. The Energy Profits Levy will be increased by 10 percentage points to 35% and extended to the end of March 2028, and a new, temporary 45% Electricity Generator Levy will be applied on the extraordinary returns being made by electricity generators. While taking these necessary steps, the government also recognises that businesses are facing significant inflationary pressures. The Autumn Statement sets out a package of targeted support to help with business rates costs worth £13.6 billion over the next 5 years. The business rates multipliers will be frozen in 2023-24, and upward transitional relief caps will provide support to ratepayers facing large bill increases following the revaluation. The relief for retail, hospitality and leisure sectors will be extended and increased, and there will be additional support provided for small businesses. The government is taking a balanced approach between revenue raising and spending restraint, whilst protecting vital public services. The Autumn Statement confirms that total departmental spending will grow in real terms at 3.7% a year on average over the current Spending Review period. Within this, departments will identify savings to manage pressures from higher inflation, supported by an Efficiency and Savings Review. To help get debt falling, for the years beyond the current Spending Review period, planned departmental resource spending will continue to grow, but slower than the economy, at 1% a year in real terms until 2027-28. Total departmental capital spending in 2024-25 will be maintained in cash terms until 2027-28, delivering £600 billion of investment over the next 5 years. This includes maintaining the government’s commitments to deliver major infrastructure projects. While delivering overall spending restraint, the government is prioritising further investment in the NHS and social care, and in schools. Supporting these two public services is the government’s priority for public spending. The Autumn Statement makes up to £8 billion of funding available for the NHS and adult social care in England in 2024-25. This includes £3.3 billion to respond to the significant pressures facing the NHS, enabling rapid action to improve emergency, elective and primary care performance, and introducing reforms to support the workforce and improve performance across the health system over the longer term. The NHS’s performance is closely tied to that of the adult social care system, so the government will also make available up to £4.7 billion in 202425 to put the adult social care system in England on a stronger financial footing and improve the quality of and access to care for many of the most vulnerable in our society. This includes £1 billion to directly support discharges from hospital into the community, to support the NHS. The Autumn Statement announces a real-terms increase in per pupil funding from that committed at Spending Review 2021. The core schools budget in England will receive £2.3 billion of additional funding in each of 2023-24 and 2024-25, enabling schools to continue to invest in high quality teaching and to target additional support to the children who need it most. The government has taken unprecedented steps to help households deal with rising living costs and the energy crisis in 2022-23. The level of spending seen this year, if sustained over time, would add further upward pressures on inflation and interest rates and risk excessively burdening future generations with higher debt. The Autumn Statement sets out steps to taper the support next year and make it more targeted to those who most need it, while also raising more through levies on energy producers. The Energy Price Guarantee (EPG) will be maintained through the winter, limiting typical energy bills to £2,500 per year. From April 2023 the EPG will rise to £3,000. With prices forecast to remain elevated throughout next year, this equates to an average of £500 support for households in 202324. On top of this, to protect the most vulnerable, in 2023-24 an additional Cost of Living Payment of £900 will be provided to households on meanstested benefits, of £300 to pensioner households, and of £150 to individuals on disability benefits. The government will also raise benefits, including working age benefits and the State Pension, in line with inflation from April 2023, ensuring they increase by over 10%. Alongside direct support, the government is setting a national ambition to reduce energy consumption by 15% by 2030, delivered through public and private investment, and a range of cost-free and low-cost steps to reduce energy demand. Economic growth is the only way to sustainably fund public services, raise living standards and level up the country. The Autumn Statement sets out measures to boost growth and productivity by investing in people, infrastructure, and innovation. These include additional support to increase labour market participation; increasing public investment in infrastructure across this Parliament; delivering planned skills reforms; and supporting R&D by increasing public funding to £20 billion in 2024-25. The government will ensure that those sectors which have the most potential for growth - such as digital, green technology and life sciences - will be supported through measures to reduce unnecessary regulation and boost innovation and growth. The Autumn Statement also announces the final Solvency II reforms, which will unlock tens of billions of pounds of investment across a range of sectors. By taking difficult decisions on tax and spending, the Autumn Statement sets out a clear and credible path to get debt falling and deliver the economic stability needed to support long-term prosperity. Mais Lecture at Bayes by Rishi Sunak in February 2022 (links on Moodle). He expressed a clear commitment to the free market economy and to a high growth and high productivity route to economic success (with low taxes). BUT it was not very clear how we get from where we are today (high taxes and slow growth….expected) to a healthy growing economy. Strategies based on education and training are fine but will take years. Tax incentives for higher business investment and innovation make sense but will not necessarily deliver the required effect (at least not quickly). Business investment has been very weak for many years and high inflation and pessimistic forecasts of slow (at best) growth make businesses cautious. This was partly a political speech to convince the Tory Party that he shares their vision of a low regulation, and low tax, free market economy. [Despite this he came second in the Tory leadership contest in summer 2022, but got to be party leader and PM after Liz Truss was forced out in October 2022.] BUT the paradox is that it is hard to unwind the high tax and high spending cycle that the pandemic and the energy crisis induced. He was very clear that cutting taxes alone will not produce the growth (and revenue) to pay for the tax cuts. Levelling up, green investment, new energy sources, health, social care, education, defence, and public investment all require high public spending, so paying for this over the next few years while cutting public debt (and taxes etc) will be a challenge.