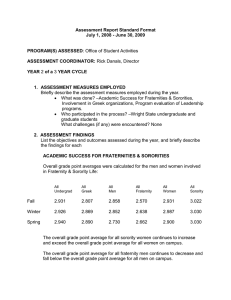

AP Language Unit 5: Community, Identity, Morality Dec 5 – Dec 21 Dec 5 337 Home at Last Dinaw Mengestu Dinaw Mengestu, born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in 1978, immigrated to the United States in 1980. He received a BA from Georgetown University and an MFA from Columbia University. His first novel, TheBeautifulThingsThatHeavenBears (2007), was named a NewYorkTimes notable Book. He published his second novel, HowtoReadtheAir, in 2010, the year he was also named one of the New Yorker’s “20 under 40” Writers to Watch. Mengestu was the Lannan visiting Writer at Georgetown University in 2007. After having spent a number of years in new york, he currently lives with his wife and son in Paris. The following essay was included in BrooklynWasMine (2008), a collection of essays about living in Brooklyn, New York. A t twenty-one I moved to Brooklyn hoping that it would be the last move I would ever make—that it would, with the gradual accumulation of time, memory, and possessions, become that place I instinctively reverted back to when asked, “So, where are you from?” I was born in Ethiopia like my parents and their parents before them, but it would be a lie to say I was from Ethiopia, having left the country when I was only two years old following a military coup and civil war, losing in the process the language and any direct memory of the family and culture I had been born into. I simply am Ethiopian, without the necessary “from” that serves as the final assurance of our identity and origin. Since leaving Addis Ababa in 1980, I’ve lived in Peoria, Illinois; in a suburb of Chicago; and then finally, before moving to Brooklyn, in Washington, D.C., the de facto capital of the Ethiopian immigrant. Others, I know, have moved much more often and across much greater distances. I’ve only known a few people, however, that have grown up with the oddly permanent feeling of having lost and abandoned a home that you never, in fact, really knew, a feeling that has nothing to do with apartments, houses, or miles, but rather the sense that no matter how far you travel, or how long you stay still, there is no place that you can always return to, no place where you fully belong. My parents, for all that they had given up by leaving Ethiopia, at least had the certainty that they had come from some place. They knew the country’s language and culture, had met outside of coffee shops along Addis’s main boulevard in the early days of their relationship, and as a result, regardless of how mangled by violence Ethiopia later became, it was irrevocably and ultimately theirs. Growing up, one of my father’s favorite sayings was, “Remember, you are Ethiopian,” even though, of course, there was nothing for me to remember apart from the bits of nostalgia and culture my parents had imparted. What remained had less to do with the idea that I was from Ethiopia and more to do with the fact that I was not from America. 1 338 I can’t say when exactly I first became aware of that feeling—that I was always going to and never from — but surely I must have felt it during those first years in Peoria, with my parents, sister, and me always sitting on the edge of whatever context we were now supposed to be a part of, whether it was the all-white Southern Baptist Church we went to every weekend, or the nearly all-white Catholic schools my sister and I attended first in Peoria and then again in Chicago at my parents’ insistence. By that point my father, haunted by the death of his brother during the revolution and the ensuing loss of the country he had always assumed he would live and die in, had taken to long evening walks that he eventually let me accompany him on. Back then he had a habit of sometimes whispering his brother’s name as he walked (“Shibrew,” he would mutter) or whistling the tunes of Amharic songs that I had never known. He always walked with both hands firmly clasped behind his back, as if his grief, transformed into something real and physical, could be grasped and secured in the palms of his hands. That was where I first learned what it meant to lose and be alone. The lesson would be reinforced over the years whenever I caught sight of my mother sitting by herself on a Sunday afternoon, staring silently out of our living room’s picture window, recalling, perhaps, her father who had died after she left, or her mother, four sisters, and one brother in Ethiopia — or else recalling nothing at all because there was no one to visit her, no one to call or see. We had been stripped bare here in America, our lives confined to small towns and urban suburbs. We had sacrificed precisely those things that can never be compensated for or repaid—parents, siblings, culture, a memory to a place that dates back more than half a generation. It’s easy to see now how even as a family we were isolated from one another — my parents tied and lost to their past; my sister and I irrevocably assimilated. For years we were strangers even among ourselves. (REFUGEES) By the time I arrived in Brooklyn I had little interest in where I actually landed. I had just graduated college and had had enough of the fights and arguments about not being “black” enough, as well as the earlier fights in high school hallways and street corners that were fought for simply being black. Now it was enough, I wanted to believe, to simply be, to say I was in Brooklyn and Brooklyn was home. It wasn’t until after I had signed the lease on my apartment that I even learned the name of the neighborhood I had moved into: Kensington, a distinctly regal name at a price that I could afford; it was perfect, in other words, for an eager and poor writer with inflated ambitions and no sense of where he belonged. After less than a month of living in Kensington I had covered almost all of the 5 neighborhood’s streets, deliberately committing their layouts and routines to memory in a first attempt at assimilation. There was an obvious and deliberate echo to my walks, a self-conscious reenactment of my father’s routine that I adopted to stave off some of my own emptiness. It wasn’t just that I didn’t have any deep personal relationships here, it was that I had chosen this city as the place 339 to redefine, to ground, to secure my place in the world. If I could bind myself to Kensington physically, if I could memorize and mentally reproduce in accurate detail the various shades of the houses on a particular block, then I could stake my own claim to it, and in doing so, no one could tell me who I was or that I didn’t belong. On my early-morning walks to the F train I passed in succession a Latin American restaurant and grocery store, a Chinese fish market, a Halal butcher shop, followed by a series of Pakistani and Bangladeshi takeout restaurants. This cluster of restaurants on the corner of Church and McDonald, I later learned, sold five-dollar plates of lamb and chicken biryani in portions large enough to hold me over for a day, and in more financially desperate times, two days. Similarly, I learned that the butcher and fish shop delivery trucks arrived on most days just as I was making my way to the train. If I had time, I found it hard not to stand and stare at the refrigerated trucks with their calf and sheep carcasses dangling from hooks, or at the tanks of newly arrived bass and catfish flapping around in a shallow pool of water just deep enough to keep them alive. 2 It didn’t take long for me to develop a fierce loyalty to Kensington, to think of the neighborhood and my place in it as emblematic of a grander immigrant narrative. In response to that loyalty, I promised to host a “Kensington night” for the handful of new friends that I eventually made in the city, an evening that would have been comprised of five-dollar lamb biryani followed by two-dollar Budweisers at Denny’s, the neighborhood’s only full-fledged bar — a defunct Irish pub complete with terribly dim lighting and wooden booths. I never hosted a Kensington night, however, no doubt in part because I had established my own private relationship to the neighborhood, one that could never be shared with others in a single evening of cheap South Asian food and beer. I knew the hours of the call of the muezzin that rang from the mosque a block away from my apartment. I heard it in my bedroom every morning, afternoon, and evening, and if I was writing when it called out, I learned that it was better to simply stop and admire it. My landlord’s father, an old gray-haired Chinese immigrant who spoke no English, gradually smiled at me as I came and went, just as I learned to say hello, as politely as possible, in Mandarin every time I saw him. The men behind the counters of the Bangladeshi takeout places now knew me by sight. A few, on occasion, slipped an extra dollop of vegetables or rice into my to-go container, perhaps because they worried that I wasn’t eating enough. One in particular, who was roughly my age, spoke little English, and smiled wholeheartedly whenever I came in, gave me presweetened tea and free bread, a gesture that I took to be an acknowledgment that, at least for him, I had earned my own, albeit marginal, place here. And so instead of sitting with friends in a brightly lit fluorescent restaurant with cafeteria-style service, I found myself night after night quietly walking around the neighborhood in between sporadic fits of writing. Kensington was no more beautiful by night than by day, and perhaps this very absence of grandeur allowed me to feel more at ease wandering its streets at night. The haphazard 340 gathering of immigrants in Kensington had turned it into a place that even someone like me, haunted and conscious of race and identity at every turn, could slip and blend into. Inevitably on my way home I returned to the corner of Church and McDonald with its glut of identical restaurants. On warm nights, I had found it was the perfect spot to stand and admire not only what Kensington had become with the most recent wave of migration, but what any close-knit community — whether its people came here one hundred years ago from Europe or a decade ago from Africa, Asia, or the Caribbean — has provided throughout Brooklyn’s history: a second home. There, on that corner, made up of five competing South Asian restaurants of roughly equal quality, dozens of Pakistani and Bangladeshi men gathered one night after another to drink chai out of paper cups. The men stood there talking for hours, huddled in factions built in part, I imagine, around restaurant loyalties. Some nights I sat in one of the restaurants and watched from a corner table with a book in hand as an artificial prop. A few of the men always stared, curious no doubt as to what I was doing there. Even though I lived in Kensington, when it came to evening gatherings like this, I was the foreigner and tourist. On other nights I ordered my own cup of tea and stood a few feet away on the edge of the sidewalk, near the subway entrance or at the bus stop, and silently stared. I had seen communal scenes like this before, especially while living in Washington, D.C., where there always seemed to be a cluster of Ethiopians, my age or older, gathered together outside coffee shops and bars all over the city, talking in Amharic with an ease and fluency that I admired and envied. They told jokes that didn’t require explanation and debated arguments that were decades in the making. All of this was coupled with the familiarity and comfort of speaking in our native tongue. At any given moment, they could have told you without hesitancy where they were from. And so I had watched, hardly understanding a word, hoping somehow that the simple act of association and observation was enough to draw me into the fold. Here, then, was a similar scene, this one played out on a Brooklyn corner with 10 a culture and history different from the one I had been born into, but familiar to me nonetheless. The men on 3 that corner in Kensington, just like the people I had known throughout my life, were immigrants in the most complete sense of the word — their loyalties still firmly attached to the countries they had left one, five, or twenty years earlier. If there was one thing I admired most about them, it was that they had succeeded, at least partly, in re-creating in Brooklyn some of what they had lost when they left their countries of origin. Unlike the solitary and private walks my father and I took, each of us buried deep in thoughts that had nowhere to go, this nightly gathering of Pakistani and Bangladeshi men was a makeshift reenactment of home. Farther down the road from where they stood were the few remaining remnants of the neighborhood’s older Jewish community—one synagogue, a kosher deli — proof, if one was ever needed, that Brooklyn is always reinventing itself, that there is room here for us all. 341 While the men stood outside on the corner, their numbers gradually increasing until they spilled out into the street as they talked loudly among themselves, I once again played my own familiar role of quiet, jealous observer and secret admirer. I have no idea what those men talked about, if they discussed politics, sex, or petty complaints about work. It never mattered anyway. The substance of the conversation belonged to them, and I couldn’t have cared less. What I had wanted and found in them, what I admired and adored about Kensington, was the assertion that we can rebuild and remake ourselves and our communities over and over again, in no small part because there have always been corners in Brooklyn to do so on. I stood on that corner night after night for the most obvious of reasons — to be reminded of a way of life that persists regardless of context; to feel, however foolishly, that I too was attached to something. Monday homework exercise: Where do you truly feel at home? (I don’t mean your house/apartment, I mean which city/town/village neighbourhood. Identify where you would say ‘you are from’ and write 200 words describing it to me please.) Exploring the Text 1. Dinaw Mengestu opens the essay with a paragraph of commentary before he provides a more chronological account of his early life. What is the effect on you as a reader? What do you know about the narrator from this paragraph? How do you interpret the final sentence? 2. How does the form of the following sentence, taken from paragraph 2, reinforce its meaning? I’ve only known a few people, however, that have grown up with the oddly permanent feeling of having lost and abandoned a home that you never, in fact, really knew, a feeling that has nothing to do with apartments, houses, or miles, but rather the sense that no matter how far you travel, or how long you stay still, there is no place that you can always return to, no place where you fully belong. 3. One of the themes that Mengestu develops in this essay is isolation. What are the different ways that isolation manifests itself in different people and settings in the communities he describes? 4. What does Mengestu do to make his “first attempt at assimilation” (para.5)? How does his new, chosen identity as a “poor writer with inflated ambitions” (para. 4) contribute to this attempt? 4 5. What does he mean when he writes that he begins to think of himself as “emblematic of a grander immigrant narrative” (para. 7)? 6. What are the qualities about Kensington, Brooklyn, that appeal to Mengestu and draw him in? In what ways does he interact with his neighborhood? In what ways has Brooklyn served as “a second home” (para. 9) to different groups over the years, as explained in this essay? Mengestu describes himself in various ways: for example, “haunted and conscious of race and identity at every turn” (para. 8), “foreigner and tourist” (para. 9), “quiet, jealous observer” (para. 7. 8. 11). Who is he by the end of the essay — one of 342 these, a combination of them, or something else entirely? Consider what he means by the qualifying phrase “however foolishly” in the final line of the essay. 9. According to this essay, how does Mengestu define “community”? What does the concept mean to him? Is it the same as “home”? Tuesday Homework: Read and answer questions in Blue Dec 7 Facebook Friendonomics Scott Brown Scott Brown (b.1976) became NewYork magazine’s theater critic in the fall of 2010. After graduating from Harvard, he was a senior writer for Entertainment Weekly and a columnist for Wired magazine, where the following essay appeared in 2008. He is the co-author (with Anthony King) of the offBroadway comedy Gutenberg!TheMusical! H ey, want to be my friend? It’s more than possible; it’s probable. Hell, we may already be friends — I haven’t checked my email in a few minutes. And once we are, we will be, as they say, 4-eva. A perusal of my Facebook Friend roster reveals that I, a medium-social individual of only middling lifetime popularity, have never lost a friend. They’re all there: elementary school friends, high school friends, college friends, work friends, friends of friends, friends of exgirlfriends — the constellation of familiar faces crowds my Friendbox like medals on Mussolini’s chest. 5 I’m Friend-rich—at least onscreen. I’ve never lost touch with anyone, it seems. What I’ve lost is the right to lose touch. This says less about my innate lovability, I think, than about the current inflated state of Friendonomics. Think of it as the Long Tail of Friendship — in the age of queue-able social priorities, Twitterable status updates, and amaranthine cloud memory, keeping friends requires almost no effort at all. We have achieved Infinite Friendspace, which means we need never drift from old pals nor feel the poignant tug of passive friend-loss. It also means that even the flimsiest of attachments — the chance convention buddy, the cube-mate from the ’90s, the bar-napkin hookup — will be preserved, in perpetuity, under the flattering, flattening banner of “Friend.” (Sure, you can rank and categorize them to your heart’s content, but who’d be callous enough to actually categorize a hookup under “Hookup”?) HOMOGENIZATION. Poin-yent It has been argued that this Infinite Friendspace is an unalloyed good. But while this plays nicely into our sentimental ideal of lifelong friendship, it’s having at least three catastrophic effects. First, it encourages hoarding. 6 We squirrel away Friends the way our grandparents used to save nickels — obsessively, desperately, 343 as if we’ll run out of them some day. (Of course, they lived through the Depression. And we lived through — what, exactly? Middle school? 90210? The Electric Slide?) Humans are natural pack rats, and given the chance we’ll stockpile anything of nominal value. Friends are the currency of the socially networked world; therefore, it follows that more equals better. But the more Friends you have, the less they’re worth—and, more to the point, the less human they are. People become mere collectibles, like Garbage Pail Kids. And call me a buzz kill, but I don’t want to be anyone’s Potty Scotty. Most gravely, we’ve lost our right to lose touch. “A friend may well 5 be reckoned the masterpiece of Nature,” Emerson wrote, not bothering to add, “and like most things natural, friendship is biodegradable.” We scrawl “Friends Forever” in yearbooks, but we quietly realize, 7 with relief, that some bonds are meant to be shed, like snakeskin or a Showtime subscription. It’s nature’s way of allowing you to change, adapt, evolve, or devolve as you wish — and freeing you from the exhaustion of multifront friend maintenance. Fine, you can “Remove Friend,” but what kind of monster actually does that? Deletion is scary — and, we’re told, unnecessary in the Petabyte Age. That’s what made good old-fashioned losing touch so wonderful—friendships, like long-forgotten photos and mixtapes, would distort and slowly whistle into oblivion, quite naturally, nothing personal. It was sweet and sad and, though you’d rarely admit it, necessary. And maybe that’s the answer: A Facebook app we’ll call the Fade Utility. Untended Friends would gradually display a sepia cast on the picture, a blurring of the neglected profile — perhaps a coffee stain might appear on it or an unrelated phone number or grocery list. The individual’s status updates might fade and get smaller. The user may then choose to notice and reach out to the person in some meaningful way — no pokes! Or they might pretend not to notice. Without making a choice, they could simply let that person go. Would that really be so awful? I realize that I may lose a few Friends by saying this. I invite them to remove me. Though I think they’ll find it harder than they imagine. I’ve never lost a Friend, you see, and I’m starting to worry I never will. 8 9 Exploring the Text 1. What is Brown’s main point? Is he arguing against Facebook and social networks in general? What are the major points of his argument? Do you find one particularly strong or weak? Explain. 2. Where does Brown address the counterargument? Do you think that he fleshes it out sufficiently or glosses over it? 3. Brown proposes one solution to the problem he defines: “A Facebook app we’ll call the Fade Utility” (para. 6). Is he serious? Does his facetious or sarcastic tone undermine his argument? 4. How does Brown use humor to make his point? Analyze two specific examples. How would you characterize the humor? Is it gentle ribbing, stinging sarcasm, or bitter irony? 5. Explain why you agree or disagree with the following assertion that Brown makes: “Friends are the currency of the socially networked world; therefore, it follows that more equals better. But the more Friends you have, the less they’re worth — and, more to the point, the less human they are. People become mere collectibles . . .” (para. 3). Homework for Wednesday night: Answer question 5 in a paragraph of about 150 words. Send me a screenshot of your work before our next class please. Dec 9 Small Change Why the Revolution Will Not Be Tweeted Malcolm Gladwell Author of four best-selling books, Malcolm Gladwell (b. 1963) grew up in Ontario, Canada, the son of an English university professor father and a Jamaican therapist mother. He has been a staff writer with the NewYorker magazine since 1996, and in 2005 he was named one of Time magazine’s 100 Most Influential People. His books include The Tipping Point: How Little Things Make a Big Difference (2000), Blink: The Powerof Thinking without Thinking (2005), and Outliers:The Story of Success (2008). Gladwell’s What the Dog Saw (2009) is a compilation of articles published in the NewYorker. His writing often explores the implications of research in the social sciences and psychology. The following article, which appeared in the NewYorker in 2010, compares the intricate network of activists who brought about the civil rights movement with the social media networks that have sprung up on the Internet. A t four-thirty in the afternoon on Monday, February 1, 1960, four college students sat down at the lunch counter at the Woolworth’s in downtown Greensboro, North Carolina. They were freshmen at North Carolina A. & T., a black college a mile or so away. 345 “I’d like a cup of 10 coffee, please,” one of the four, Ezell Blair, said to the waitress. “We don’t serve Negroes here,” she replied. The Woolworth’s lunch counter was a long L-shaped bar that could seat sixty-six people, with a standup snack bar at one end. The seats were for whites. The snack bar was for blacks. Another employee, a black woman who worked at the steam table, approached the students and tried to warn them away. “You’re acting stupid, ignorant!” she said. They didn’t move. Around five-thirty, the front doors to the store were locked. The four still didn’t move. Finally, they left by a side door. Outside, a small crowd had gathered, including a photographer from the Greensboro Record. “I’ll be back tomorrow with A. & T. College,” one of the students said. By next morning, the protest had grown to twenty-seven men and four 5 women, most from the same dormitory as the original four. The men were dressed in suits and ties. The students had brought their schoolwork, and studied as they sat at the counter. On Wednesday, students from Greensboro’s “Negro” secondary school, Dudley High, joined in, and the number of protesters swelled to eighty. By Thursday, the protesters numbered three hundred, including three white women, from the Greensboro campus of the University of North Carolina. By Saturday, the sit-in had reached six hundred. People spilled out onto the street. White teenagers waved Confederate flags. Someone threw a firecracker. At noon, the A. & T. football team arrived. “Here comes the wrecking crew,” one of the white students shouted. By the following Monday, sit-ins had spread to Winston-Salem, twenty-five miles away, and Durham, fifty miles away. The day after that, students at Fayetteville State Teachers College and at Johnson C. Smith College, in Charlotte, joined in, followed on Wednesday by students at St. Augustine’s College and Shaw University, in Raleigh. On Thursday and Friday, the protest crossed state lines, surfacing in Hampton and Portsmouth, Virginia, in Rock Hill, South Carolina, and in Chattanooga, Tennessee. By the end of the month, there were sit-ins throughout the South, as far west as Texas. “I asked every student I met what the first day of the sitdowns had been like on his campus,” the political theorist Michael Walzer wrote in Dissent. “The answer was always the same: ‘It was like a fever. Everyone wanted to go.’ ” Some seventy thousand students eventually took part. Thousands were arrested and untold thousands more radicalized. These events in the early sixties became a civil-rights war that engulfed the South for the rest of the decade — and it happened without e-mail, texting, Facebook, or Twitter. The world, we are told, is in the midst of a revolution. The new tools of social media have reinvented social activism. With Facebook and Twitter and the like, the traditional relationship between political authority and popular will has been upended, making it easier for the powerless to collaborate, coö rdinate, and give voice to their concerns. When ten thousand protesters took to the streets in Moldova in the spring of 2009 to protest against their country’s Communist 346 government, the action was dubbed the Twitter Revolution, because of the means by which the demonstrators had been brought together. A few months after that, when student protests rocked Tehran, the State Department took the unusual step of asking Twitter to suspend scheduled maintenance of its Web site, because the Administration didn’t want such a critical organizing tool out of service at the height of the demonstrations. “Without Twitter the people of Iran would not have felt empowered and confident to stand up for freedom and democracy,” Mark Pfeifle, a former national-security adviser, later wrote, calling for Twitter to be nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. Where activists were once defined by their causes, they are now defined by their tools. Facebook warriors go online to push for change. “You are the best hope for us all,” James K. Glassman, a former senior State Department official, told a crowd of cyber activists at a recent conference sponsored by Facebook, A. T. & T., Howcast, MTV, and 11 Google. Sites like Facebook, Glassman said, “give the U.S. a significant competitive advantage over terrorists. Some time ago, I said that Al Qaeda was ‘eating our lunch on the Internet.’ That is no longer the case. Al Qaeda is stuck in Web 1.0. The Internet is now about interactivity and conversation.” These are strong, and puzzling, claims. Why does it matter who is eating whose lunch on the Internet? Are people who log on to their Facebook page really the best hope for us all? As for Moldova’s so-called Twitter Revolution, Evgeny Morozov, a scholar at Stanford who has been the most persistent of digital evangelism’s critics, points out that Twitter has scant internal significance in Moldova, a country where very few Twitter accounts exist. Nor does it seem to have been a revolution, not least because the protests — as Anne Applebaum suggested in the Washington Post — may well have been a bit of stagecraft cooked up by the government. (In a country paranoid about Romanian revanchism, the protesters flew a Romanian flag over the Parliament building.) In the Iranian case, meanwhile, the people tweeting about the demonstrations were almost all in the West. “It is time to get Twitter’s role in the events in Iran right,” Golnaz Esfandiari wrote, this past summer, in Foreign Policy. “Simply put: There was no Twitter Revolution inside Iran.” The cadre of prominent bloggers, like Andrew Sullivan, who championed the role of social media in Iran, Esfandiari continued, misunderstood the situation. “Western journalists who couldn’t reach — or didn’t bother reaching?—people on the ground in Iran simply scrolled through the English-language tweets post with tag #iranelection,” she wrote. “Through it all, no one seemed to wonder why people trying to coordinate protests in Iran would be writing in any language other than Farsi.” Some of this grandiosity is to be expected. Innovators tend to be solipsists. They often want to cram every stray fact and experience into their new model. As the historian Robert Darnton has written, “The marvels of communication technology in the present have produced a false consciousness about the past — even a sense that communication has no history, or had nothing of importance to consider before the days of television and the Internet.” But there is something 347 else at work here, in the outsized enthusiasm for social media. Fifty years after one of the most extraordinary episodes of social upheaval in American history, we seem to have forgotten what activism is. Greensboro in the early nineteen-sixties was the kind of place where racial insub10 ordination was routinely met with violence. The four students who first sat down at the lunch counter were terrified. “I suppose if anyone had come up behind me and yelled ‘Boo,’ I think I would have fallen off my seat,” one of them said later. On the first day, the store manager notified the police chief, who immediately sent two officers to the store. On the third day, a gang of white toughs showed up at the lunch counter and stood ostentatiously behind the protesters, ominously muttering epithets such as “burr-head nigger.” A local Ku Klux Klan leader made an appearance. On Saturday, as tensions grew, someone called in a bomb threat, and the entire store had to be evacuated. The dangers were even clearer in the Mississippi Freedom Summer Project of 1964, another of the sentinel campaigns of the civil-rights movement. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee recruited hundreds of Northern, largely white unpaid volunteers to run Freedom Schools, register black voters, and raise civil-rights awareness in the Deep South. “No one should go anywhere alone, but certainly not in an automobile and certainly not at night,” they were instructed. Within days of arriving in Mississippi, three volunteers—Michael Schwerner, James Chaney, and Andrew Goodman — were kidnapped and killed, and, during the rest of the summer, thirty-seven black churches were set on fire and dozens of safe houses were bombed; volunteers were beaten, shot at, arrested, and trailed by pickup trucks full of armed men. A 12 quarter of those in the program dropped out. Activism that challenges the status quo — that attacks deeply rooted problems — is not for the faint of heart. What makes people capable of this kind of activism? The Stanford sociologist Doug McAdam compared the Freedom Summer dropouts with the participants who stayed, and discovered that the key difference wasn’t, as might be expected, ideological fervor. “All of the applicants — participants and withdrawals alike—emerge as highly committed, articulate supporters of the goals and values of the summer program,” he concluded. What mattered more was an applicant’s degree of personal connection to the civil-rights movement. All the volunteers were required to provide a list of personal contacts — the people they wanted kept apprised of their activities—and participants were far more likely than dropouts to have close friends who were also going to Mississippi. High-risk activism, McAdam concluded, is a “strong-tie” phenomenon. This pattern shows up again and again. One study of the Red Brigades, the Italian terrorist group of the nineteen-seventies, found that seventy per cent of recruits had at least one good friend already in the organization. The same is true of the men who joined the mujahideen in Afghanistan. Even revolutionary 348 actions that look spontaneous, like the demonstrations in East Germany that led to the fall of the Berlin Wall, are, at core, strong-tie phenomena. The opposition movement in East Germany consisted of several hundred groups, each with roughly a dozen members. Each group was in limited contact with the others: at the time, only thirteen per cent of East Germans even had a phone. All they knew was that on Monday nights, outside St. Nicholas Church in downtown Leipzig, people gathered to voice their anger at the state. And the primary determinant of who showed up was “critical friends” — the more friends you had who were critical of the regime, the more likely you were to join the protest. So one crucial fact about the four freshmen at the Greensboro lunch counter — David Richmond, Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair, and Joseph McNeil — was their relationship with one another. McNeil was a roommate of Blair’s in A. & T.’s Scott Hall dormitory. Richmond roomed with McCain one floor up, and Blair, Richmond, and McCain had all gone to Dudley High School. The four would smuggle beer into the dorm and talk late into the night in Blair and McNeil’s room. They would all have remembered the murder of Emmett Till in 1955, the Montgomery bus boycott that same year, and the showdown in Little Rock in 1957. It was McNeil who brought up the idea of a sit-in at Woolworth’s. They’d discussed it for nearly a month. Then McNeil came into the dorm room and asked the others if they were ready. There was a pause, and McCain said, in a way that works only with people who talk late into the night with one another, “Are you guys chicken or not?” Ezell Blair worked up the courage the next day to ask for a cup of coffee because he was flanked by his roommate and two good friends from high school. The kind of activism associated with social media isn’t like this at all. The plat15 forms of social media are built around weak ties. Twitter is a way of following (or being followed by) people you may never have met. Facebook is a tool for efficiently managing your acquaintances, for keeping up with the people you would not otherwise be able to stay in touch with. That’s why you can have a thousand “friends” on Facebook, as you never could in real life. This is in many ways a wonderful thing. There is strength in weak ties, as the sociologist Mark Granovetter has observed. Our acquaintances—not our friends — are our greatest source of new ideas and information. The Internet lets us exploit the power of these kinds of distant connections with marvelous efficiency. It’s terrific at the diffusion of innovation, interdisciplinary collaboration, seamlessly matching up buyers and sellers, and the logistical functions of the dating world. But weak ties seldom lead to high-risk activism. 13 In a new book called The Dragonfly Effect: Quick, Effective, and Powerful Ways to Use Social Media to Drive Social Change, the business consultant Andy Smith and the Stanford Business School professor Jennifer Aaker tell the story of Sameer Bhatia, a young Silicon Valley entrepreneur who came down with acute myelogenous leukemia. It’s a perfect illustration of social media’s strengths. Bhatia needed a bone-marrow transplant, but he could not find a match among his relatives and friends. The odds were best with a donor of his ethnicity, and there were few South Asians in the national bone-marrow database. So Bhatia’s business partner sent out an e-mail explaining Bhatia’s plight to more than four hundred of their acquaintances, who forwarded the e-mail to their personal contacts; Facebook pages and YouTube videos were devoted to the Help Sameer campaign. Eventually, nearly twenty-five thousand new people were registered in the bone-marrow database, and Bhatia found a match. But how did the campaign get so many people to sign up? By not asking too much of them. That’s the only way you can get someone you don’t really know to do something on your behalf. You can get thousands of people to sign up for a donor registry, because doing so is pretty easy. You have to send in a cheek swab and—in the highly unlikely event that your bone marrow is a good match for someone in need—spend a few hours at the hospital. Donating bone marrow isn’t a trivial matter. But it doesn’t involve financial or personal risk; it doesn’t mean spending a summer being chased by armed men in pickup trucks. It doesn’t require that you confront socially entrenched norms and practices. In fact, it’s the kind of commitment that will bring only social acknowledgment and praise. The evangelists of social media don’t understand this distinction; they seem to believe that a Facebook friend is the same as a real friend and that signing up for a donor registry in Silicon Valley today is activism in the same sense as sitting at a segregated lunch counter in Greensboro in 1960. “Social networks are particularly effective at increasing motivation,” Aaker and Smith write. But that’s not true. Social networks are effective at increasing participation — by lessening the level of motivation that participation requires. The Facebook page of the Save Darfur Coalition has 1,282,339 members, who have donated an average of nine cents apiece. The next biggest Darfur charity on Facebook has 22,073 members, who have donated an average of thirty-five cents. Help Save Darfur has 2,797 members, who have given, on average, fifteen cents. A spokesperson for the Save Darfur Coalition told Newsweek, “We wouldn’t necessarily gauge someone’s value to the advocacy movement based on what they’ve given. This is a powerful mechanism to engage this critical population. They inform their community, attend events, volunteer. It’s not something you can measure by looking at a ledger.” In other words, Facebook activism succeeds not by motivating people to make a real sacrifice but by motivating them to do the things that people do when they are not motivated enough to make a real sacrifice. We are a long way from the lunch counters of Greensboro. The students who joined the sit-ins across the South during the winter of 1960 20 described the movement as a “fever.” But the civil-rights movement was more like a military campaign than like a contagion. In the late nineteen-fifties, there had 350 been sixteen sit-ins in various cities throughout the South, fifteen of which were formally organized by civil-rights organizations like the N.A.A.C.P. and CORE. Possible locations for activism were scouted. Plans were drawn up. Movement activists held training sessions and retreats for would-be protesters. The Greensboro Four were a product of this groundwork: all were members of the N.A.A.C.P. Youth Council. They had close ties with the head of the local N.A.A.C.P. chapter. They had been briefed on the earlier wave of sit-ins in Durham, and had been part of a series of movement meetings in activist churches. When the sit-in movement spread from Greensboro throughout the South, it did not spread indiscriminately. It spread to those cities which had preexisting “movement centers”—a core of dedicated and trained activists ready to turn the “fever” into action. 14 The civil-rights movement was high-risk activism. It was also, crucially, strategic activism: a challenge to the establishment mounted with precision and discipline. The N.A.A.C.P. was a centralized organization, run from New York according to highly formalized operating procedures. At the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Martin Luther King, Jr., was the unquestioned authority. At the center of the movement was the black church, which had, as Aldon D. Morris points out in his superb 1984 study, The Origins of the Civil Rights Movement, a carefully demarcated division of labor, with various standing committees and disciplined groups. “Each group was task-oriented and coordinated its activities through authority structures,” Morris writes. “Individuals were held accountable for their assigned duties, and important conflicts were resolved by the minister, who usually exercised ultimate authority over the congregation.” This is the second crucial distinction between traditional activism and its online variant: social media are not about this kind of hierarchical organization. Facebook and the like are tools for building networks, which are the opposite, in structure and character, of hierarchies. Unlike hierarchies, with their rules and procedures, networks aren’t controlled by a single central authority. Decisions are made through consensus, and the ties that bind people to the group are loose. This structure makes networks enormously resilient and adaptable in lowrisk situations. Wikipedia is a perfect example. It doesn’t have an editor, sitting in New York, who directs and corrects each entry. The effort of putting together each entry is self-organized. If every entry in Wikipedia were to be erased tomorrow, the content would swiftly be restored, because that’s what happens when a network of thousands spontaneously devote their time to a task. There are many things, though, that networks don’t do well. Car companies sensibly use a network to organize their hundreds of suppliers, but not to design their cars. No one believes that the articulation of a coherent design philosophy is best handled by a sprawling, leaderless organizational system. Because networks don’t have a centralized leadership structure and clear lines of authority, they have real difficulty reaching consensus and setting goals. They can’t think strategically; they are chronically prone to conflict and error. How do you make difficult choices about tactics or strategy or philosophical direction when everyone has an equal say? 351The Palestine Liberation Organization originated as a network, and the 25 internationalrelations scholars Mette Eilstrup-Sangiovanni and Calvert Jones argue in a recent essay in International Security that this is why it ran into such trouble as it grew: “Structural features typical of networks—the absence of central authority, the unchecked autonomy of rival groups, and the inability to arbitrate quarrels through formal mechanisms — made the P.L.O. excessively vulnerable to outside manipulation and internal strife.” In Germany in the nineteen-seventies, they go on, “the far more unified and successful left-wing terrorists tended to organize hierarchically, with professional management and clear divisions of labor. They were concentrated geographically in universities, where they could establish central leadership, trust, and camaraderie through regular, face-to-face meetings.” They seldom betrayed their comrades in arms during police interrogations. Their counterparts on the right were organized as decentralized networks, and had no such discipline. These groups were regularly infiltrated, and members, once arrested, easily gave up their comrades. Similarly, Al Qaeda was most dangerous when it was a unified hierarchy. Now that it has dissipated into a network, it has proved far less effective. The drawbacks of networks scarcely matter if the network isn’t interested in systemic change — if it just wants to frighten or humiliate or make a splash — or if it doesn’t need to think strategically. But if you’re taking on a powerful and organized establishment you have to be a 15 hierarchy. The Montgomery bus boycott required the participation of tens of thousands of people who depended on public transit to get to and from work each day. It lasted a year. In order to persuade those people to stay true to the cause, the boycott’s organizers tasked each local black church with maintaining morale, and put together a free alternative private carpool service, with forty-eight dispatchers and forty-two pickup stations. Even the White Citizens Council, King later said, conceded that the carpool system moved with “military precision.” By the time King came to Birmingham, for the climactic showdown with Police Commissioner Eugene (Bull) Connor, he had a budget of a million dollars, and a hundred full-time staff members on the ground, divided into operational units. The operation itself was divided into steadily escalating phases, mapped out in advance. Support was maintained through consecutive mass meetings rotating from church to church around the city. Boycotts and sit-ins and nonviolent confrontations — which were the weapons of choice for the civil-rights movement — are high-risk strategies. They leave little room for conflict and error. The moment even one protester deviates from the script and responds to provocation, the moral legitimacy of the entire protest is compromised. Enthusiasts for social media would no doubt have us believe that King’s task in Birmingham would have been made infinitely easier had he been able to communicate with his followers through Facebook, and contented himself with tweets from a Birmingham jail. But networks are messy: think of the ceaseless pattern of correction and revision, amendment and debate, that characterizes Wikipedia. If Martin Luther King, Jr., had tried to do a wiki-boycott in 352 Montgomery, he would have been steamrollered by the white power structure. And of what use would a digital communication tool be in a town where ninety-eight per cent of the black community could be reached every Sunday morning at church? The things that King needed in Birmingham—discipline and strategy — were things that online social media cannot provide. The bible of the social-media movement is Clay Shirky’s Here Comes Everybody. Shirky, who teaches at New York University, sets out to demonstrate the organizing power of the Internet, and he begins with the story of Evan, who worked on Wall Street, and his friend Ivanna, after she left her smart phone, an expensive Sidekick, on the back seat of a New York City taxicab. The telephone company transferred the data on Ivanna’s lost phone to a new phone, whereupon she and Evan discovered that the Sidekick was now in the hands of a teen-ager from Queens, who was using it to take photographs of herself and her friends. When Evan e-mailed the teen-ager, Sasha, asking for the phone back, she 30 replied that his “white ass” didn’t deserve to have it back. Miffed, he set up a Web page with her picture and a description of what had happened. He forwarded the link to his friends, and they forwarded it to their friends. Someone found the MySpace page of Sasha’s boyfriend, and a link to it found its way onto the site. Someone found her address online and took a video of her home while driving by; Evan posted the video on the site. The story was picked up by the news filter Digg. Evan was now up to ten e-mails a minute. He created a bulletin board for his readers to share their stories, but it crashed under the weight of responses. Evan and Ivanna went to the police, but the police filed the report under “lost,” rather than “stolen,” which essentially closed the case. “By this point millions of readers were watching,” Shirky writes, “and dozens of mainstream news outlets had covered the story.” Bowing to the pressure, the N.Y.P.D. reclassified the item as “stolen.” Sasha was arrested, and Evan got his friend’s Sidekick back. Shirky’s argument is that this is the kind of thing that could never have happened in the preInternet age—and he’s right. Evan could never have tracked down Sasha. The story of the Sidekick would never have been publicized. An army of people could never have been assembled to wage this fight. The police wouldn’t have bowed to the pressure of a lone person who had misplaced something as trivial as a cell phone. The story, to Shirky, illustrates “the ease and speed with which a group can be mobilized for the right kind of cause” in the Internet age. 16 Shirky considers this model of activism an upgrade. But it is simply a form of organizing which favors the weak-tie connections that give us access to information over the strong-tie connections that help us persevere in the face of danger. It shifts our energies from organizations that promote strategic and disciplined activity and toward those which promote resilience and adaptability. It makes it easier for activists to express themselves, and harder for that expression to have any impact. The instruments of social media are well suited to making the existing social order more efficient. They are not a natural enemy of the status quo. If you are of the opinion that all the world needs is a little buffing around the edges, this should not trouble you. But if you think that there are still lunch counters out there that need integrating, it ought to give you pause. Shirky ends his story of the Sidekick by asking, portentously, “What happens next?” — no doubt imagining future waves of digital protesters. But he has already answered the question. What happens next is more of the same. A networked, weak-tie world is good at things like helping Wall Streeters get phones back from teen-age girls. Viva la revolució n. Dec 12 Exploring the Text 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Most of Malcolm Gladwell’s readers are familiar with the lunch counter event at Woolworth’s in Greensboro, North Carolina, that catalyzed the civil rights movement. Why, then, does he begin by retelling it and providing such detail in the opening section? How does this serve as a foundation for the argument he develops? Consider both what he tells and how he tells it. What does he mean when he writes, “Where activists were once defined by their causes, they are now defined by their tools” (para. 7)? Do you agree or disagree with this idea? Explain why. What is the key point Gladwell makes in the paragraph beginning, “Some of this grandiosity is to be expected” (para. 9)? How does he connect his statement “Innovators tend to be solipsists” with the assertion that ends the paragraph, that “we seem to have forgotten what activism is.” HowdoesGladwelldefine“high-riskactivism”(paras.11–12)?Whydoeshebelieve that activism based on today’s social media cannot qualify as “high risk”? Consider the contrast between “weak ties” and “strong ties” as part of your definition. What is the purpose of the example of Sameer Bhatia, who found a bone marrow donor through social networking (para. 17)? Do you find it persuasive, or is it too exceptional? What is the distinction between increasing motivation and increasing participation that Gladwell makes (para. 19)? Why is this distinction important to his argument? Throughout this essay, Gladwell relies heavily on expert testimony. He cites scholars and researchers as well as business analysts and State Department officials and security advisors. Choose two examples, and discuss how Gladwell uses one to support his argument and the other to examine a counterargument. In order to make his argument against the belief that the “new tools of social media have reinvented social activism” (para. 7), Gladwell must delineate precisely the central qualities of social activism. What are they? Refer to specific passages in the text to support your analysis. Gladwell does not entirely discount the power of social media. What benefits or positive impacts does he grant to social media? Do you find his term “digital evangelism” (para. 8) a critical description, a particularly apt one, or simply a colorful one? Why? 10. Gladwell uses many examples from fairly recent history, such as the fall of the Berlin Wall and protests in Moldova and Tehran, yet he repeatedly returns to the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Why? Does doing so strengthen his argument by adding coherence and depth, or weaken it by over-relying on a single example? Explain your viewpoint. 11. At key junctures in the essay, Gladwell makes sharp personal comments. In fact, his ending “Viva la revolució n” could be read as downright sarcastic. What others do you notice? Do these editorial comments add vitality and voice to the essay, or do they undercut the argument with a mocking tone? Explain your response. 17 12. Choose one of the following assertions that Gladwell makes, and challenge it by referring to an example of social activism in the United States or abroad during the past five years: “Our acquaintances—not our friends—are our greatest source of new ideas and information” (para. 16). Networks “can’t think strategically; they are chronically prone to conflict and error” (para. 24). “The things that King needed in Birmingham—discipline and strategy—were things that online social media cannot provide” (para. 28). “The instruments of social media are well suited to making the existing social order more efficient. They are not a natural enemy of the status quo” (para. 32). 18 Dec 12 Child of the Americas Aurora Levins Morales Daughter of a Puerto Rican mother and a Jewish father, Aurora Levins Morales (b.1954) lived in Puerto Rico until she was thirteen, when her family moved to Chicago. She received her undergraduate degree from Franconia University in new Hampshire and her MA and PhD from the Union Institute in Ohio. An activist and writer, Morales currently divides her time between the San Francisco Bay Area and Minneapolis. In the poem that follows, she celebrates her mixed heritage. I am a child of the Americas, a light-skinned mestiza of the Caribbean, a child of many diaspora, born into this continent at a crossroads. I am a U.S. Puerto Rican Jew, a product of the ghettos of New York I have never known. 5 An immigrant and the daughter and granddaughter of immigrants. I speak English with passion: it’s the tongue of my consciousness, a flashing knife blade of crystal, my tool, my craft. I am Caribeñ a, island grown. Spanish is in my flesh, ripples from my tongue, lodges in my hips: 10 the language of garlic and mangoes, the singing in my poetry, the flying gestures of my hands. I am of Latino america, rooted in the history of my continent: I speak from that body. I am not africa. Africa is in me, but I cannot return. 15 I am not tai ́na. Tai ́no is in me, but there is no way back. I am not european. Europe lives in me, but I have no home there. I am new. History made me. My first language was spanglish. I was born at the crossroads and I am whole. 20 Exploring the Text 1. 2. 3. 4. How does the speaker describe herself ? What characteristics does she emphasize? Why does Aurora Levins Morales introduce those characteristics in the order that she does? That is, why does she choose not to open with her Jewish or African heritage, for instance? How do you interpret the line “Europe lives in me, but I have no home there” (l. 17)? What is the tone of the poem? Is the speaker defiant, hopeful, angry, confused, ambivalent, proud? Cite specific words and phrases to support your response. Proud/defiant: claims her identity straight away ‘a US Puerto Rican Jew’ and sure of her sense of place: ‘rooted in the history of my continent’, with a lot of proud self-confidence : ‘I am new…and I am whole’. 5. Which of the following descriptions of the United States do you think the speaker would prefer: melting pot, salad bowl, mosaic? Why? To which community or communities would the speaker say she belongs? 19 Melting pot; the idea that different elements can blend together to create something new, like her being the product of different cultures and ethnicities, but being a unique individual nonetheless. You could guess some of her parts without knowing her perhaps, but many would be hidden (hence melting pot rather than salad bowl). I think that ironically, she would avoid identifying specifically with this community or that, and rather is proud to embrace her membership as product of the Americas. I feel that she avoids just thinking ‘I am Jewish’ or ‘I am Puerto Rican’ because while she is both of those things, she is not JUST those things. 6. What is the argument that Morales makes? That people cannot simply be labelled and dismissed as a member of this or that group. That each person may be infinitely more complex than stereotypes may suggest, and that the synthesis of many contributing elements is what can make every person truly special. HOMEWORK: Finish the 6 questions and send me a screenshot. Find a partner for the video project. Groups of three are OK. We will discuss in class tomorrow. 20 Dec 13 – Activism Task – Some common causes to fight for: - Animal Rights - Women’s rights - Racial Equality - Indigenous Rights - Migration Rights - Union rights - Sexuality rights - Environmental issues - Human Rights See task document: Tuesday class: We will watch some famous activist videos. I will ask you: 1) What is the cause they are promoting? 2) What is the message for the audience? 3) Which aspect of the video makes it effective? 21 Dec 14 Freedom from Want [Wednesday class p21-26] Norman Rockwell Norman Rockwell (1894 –1978) was a popular American painter and illustrator best known for his depictions of everyday life and positive American values. His first cover for the Saturday Evening Post appeared in 1916, and over three hundred followed during the next forty-seven years. In the early 1960s, he began working for Look magazine, where he turned to more political concerns such as civil rights and space exploration. In 1977, Rockwell received the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal. The 1943 painting shown on the following page appeared in the SaturdayEvening Post as part of Rockwell’s Four Freedoms series. These illustrations depict the “four essential human freedoms” delineated in President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Message to Congress on January 6, 1941: freedom of speech and expression, freedom of every person to worship God in his own way, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. The Thanksgiving scene shows Rockwell’s interpretation of freedom from want, which, in Roosevelt’s words, “means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants—everywhere in the world.” This painting appeared in the magazine with the headline, “Ours…if we fight for it” As a side note from me, Rockwell was the most quintessentially American illustrator of the 1950s, a decade many Americans still recall very nostalgically even if they were not alive then. When Trump supporters (“Make America Great Again”) are asked to identify WHEN America used to be great, many of them point to the 1950s. [At this time America was the richest nation on Earth, had just helped win WW2, was dominant within the Cold War, and had not yet experienced loss in Vietnam. America led the world in music, film, pop culture, science, and business.] Rockwell’s idealized representations of American society embodied the American Dream notion that modern America was founded on. However, a widespread failure to achieve this happiness he portrays could also be said to be at the root of the current discontent in American society. 22 23 24 - 25 Exploring the Text Below What is the perspective of the viewer? Where are the participants in the painting looking? Why? How does the painting embody the descriptors Roosevelt used—“healthy” and “peacetime”? In the 1940s, who would likely have felt included in the world shown in this painting? Who might have felt excluded? Was Rockwell successful in depicting Roosevelt’s vision of “economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants — everywhere in the world”? Explain. 26 Dec 14 The Last Thanksgiving [Compare to Rockwell]. Roz Chast Roz Chast (b.1954) grew up in Brooklyn, the child of two schoolteachers, and received a BFA from the Rhode Island School of Design, where she studied graphic design and painting. After she graduated, as she says on her Web site, she “reverted to type and began drawing cartoons once again.” More than a thousand of her cartoons have been published in the NewYorker magazine since 1978. A collection of twenty-five years of her work was published in Theories of Everything (2006). This cartoon appeared as the cover of the NewYorker in 2010. 27 Wednesday Homework: Exploring the Text [Answer the three questions below please.] 1. Clearly, Chast’s imaginary dinner guests are quite different from those in Rockwell’s painting. Yet in what ways does Chast’s depiction of Thanksgiving reflect the same American values that Rockwell’s does? 2. What do you think is Chast’s purpose in this cartoon? Is it simply to amuse? To ridicule? To provoke reflection? Explain. 3. What is Chast’s argument in this cartoon? Is Chast making a point about Thanksgiving in general or the nature of community in the twenty-first century in particular? Or both? Cite specific details in the cartoon to support your response. 28 4. The Individual’s Responsibility to the Community Each of the following texts presents a view of the individual’s responsibility to the community. Sources 1. Peter Singer, from The Singer Solution to World Poverty 2. Zapiro (Jonathan Shapiro), World Economic Forum (cartoon) 3. Christian Science Monitor Editorial Board, Warren Buffett, Bill Gates, and the Billionaire Challenge Dec 15 1. from The Singer Solution to World Poverty Peter Singer In the following selection first published in the New York Times Magazine in 1999, bioethicist Peter Singer argues for the individual’s responsibility to the world community. In the Brazilian film Central Station, Dora is a retired schoolteacher who makes ends meet by sitting at the station writing letters for illiterate people. Suddenly she has an opportunity to pocket $1,000. All she has to do is persuade a homeless 9-year-old boy to follow her to an address she has been given. (She is told he will be adopted by wealthy foreigners.) She delivers the boy, gets the money, spends some of it on a television set and settles down to enjoy her new acquisition. Her neighbor spoils the fun, however, by telling her that the boy was too old to be adopted — he will be killed and his organs sold for transplantation. Perhaps Dora knew this all along, but after her neighbor’s plain speaking, she spends a troubled night. In the morning Dora resolves to take the boy back. Suppose Dora had told her neighbor that it is a tough world, other people have nice new TV’s too, and if selling the kid is the only way she can get one, well, he was only a street kid. She would then have become, in the eyes of the audience, a monster. She redeems herself only by being prepared to bear considerable risks to save the boy. At the end of the movie, in cinemas in the affluent nations of the world, people who would have been quick to condemn Dora if she had not rescued the boy go home to places far more comfortable than her apartment. In fact, the average family in the United States spends almost one-third of its income on things that are no more necessary to them than Dora’s new TV was to her. Going out to nice restaurants, buying new clothes because the old ones are no longer stylish, vacationing at beach resorts—so much of our income is spent on things not essential to the preservation of our lives and health. Donated to one of a number 370 of charitable agencies, that money could mean the difference between life and death for children in need. All of which raises a question: In the end, what is the ethical distinction between a Brazilian who sells a homeless child to organ peddlers and an American who already has a TV and upgrades to a better one — knowing that the money could be donated to an organization that would use it to save the lives of kids in need? Of course, there are several differences between the two situations that could 5 support different moral judgments about them. For one thing, to be able to consign a child to death when he is 29 standing right in front of you takes a chilling kind of heartlessness; it is much easier to ignore an appeal for money to help children you will never meet. Yet for a utilitarian philosopher like myself — that is, one who judges whether acts are right or wrong by their consequences — if the upshot of the American’s failure to donate the money is that one more kid dies on the streets of a Brazilian city, then it is, in some sense, just as bad as selling the kid to the organ peddlers. But one doesn’t need to embrace my utilitarian ethic to see that, at the very least, there is a troubling incongruity in being so quick to condemn Dora for taking the child to the organ peddlers while, at the same time, not regarding the American consumer’s behavior as raising a serious moral issue. In his 1996 book, Living High and Letting Die, the New York University philosopher Peter Unger presented an ingenious series of imaginary examples designed to probe our intuitions about whether it is wrong to live well without giving substantial amounts of money to help people who are hungry, malnourished or dying from easily treatable illnesses like diarrhea. Here’s my paraphrase of one of these examples: Bob is close to retirement. He has invested most of his savings in a very rare and valuable old car, a Bugatti, which he has not been able to insure. The Bugatti is his pride and joy. In addition to the pleasure he gets from driving and caring for his car, Bob knows that its rising market value means that he will always be able to sell it and live comfortably after retirement. One day when Bob is out for a drive, he parks the Bugatti near the end of a railway siding and goes for a walk up the track. As he does so, he sees that a runaway train, with no one aboard, is running down the railway track. Looking farther down the track, he sees the small figure of a child very likely to be killed by the runaway train. He can’t stop the train and the child is too far away to warn of the danger, but he can throw a switch that will divert the train down the siding where his Bugatti is parked. Then nobody will be killed — but the train will destroy his Bugatti. Thinking of his joy in owning the car and the financial security it represents, Bob decides not to throw the switch. The child is killed. For many years to come, Bob enjoys owning his Bugatti and the financial security it represents. Bob’s conduct, most of us will immediately respond, was gravely wrong. Unger agrees. But then he reminds us that we, too, have opportunities to save the 371 lives of children. We can give to organizations like UNICEF or Oxfam America. How much would we have to give one of these organizations to have a high probability of saving the life of a child threatened by easily preventable diseases? (I do not believe that children are more worth saving than adults, but since no one can argue that children have brought their poverty on themselves, focusing on them simplifies the issues.) Unger called up some experts and used the information they provided to offer some plausible estimates that include the cost of raising money, administrative expenses and the cost of delivering aid where it is most needed. By his calculation, $200 in donations would help a sickly 2-year-old transform into a healthy 6-yearold — offering safe passage through childhood’s most dangerous years. To show how practical philosophical argument can be, Unger even tells his readers that they can easily donate funds by using their credit card and calling one of these toll-free numbers: (800) 367-5437 for Unicef; (800) 693-2687 for Oxfam America. Now you, too, have the information you need to save a child’s life. How should you judge yourself if you don’t do it? Think again about Bob and his Bugatti. Unlike Dora, Bob did not have to look into the eyes of the child he was sacrificing for his own material comfort. The child was a complete stranger to him and too far away to relate to in an intimate, personal way. Unlike Dora, too, he did not mislead the child or initiate the chain of events imperiling him. In all these respects, Bob’s situation resembles that of people able but unwilling to donate to overseas aid and differs from Dora’s situation. 30 If you still think that it was very wrong of Bob not to throw the switch that 10 would have diverted the train and saved the child’s life, then it is hard to see how you could deny that it is also very wrong not to send money to one of the organizations listed above. Unless, that is, there is some morally important difference between the two situations that I have overlooked. Is it the practical uncertainties about whether aid will really reach the people who need it? Nobody who knows the world of overseas aid can doubt that such uncertainties exist. But Unger’s figure of $200 to save a child’s life was reached after he had made conservative assumptions about the proportion of the money donated that will actually reach its target. One genuine difference between Bob and those who can afford to donate to overseas aid organizations but don’t is that only Bob can save the child on the tracks, whereas there are hundreds of millions of people who can give $200 to overseas aid organizations. The problem is that most of them aren’t doing it. Does this mean that it is all right for you not to do it? Suppose that there were more owners of priceless vintage cars — Carol, Dave, Emma, Fred and so on, down to Ziggy — all in exactly the same situation as Bob, with their own siding and their own switch, all sacrificing the child in order to preserve their own cherished car. Would that make it all right for Bob to do the same? To answer this question affirmatively is to endorse follow-the-crowd ethics — the kind of ethics that led many Germans to look away when the Nazi 372 atrocities were being committed. We do not excuse them because others were behaving no better. We seem to lack a sound basis for drawing a clear moral line between Bob’s situation and that of any reader of this article with $200 to spare who does not donate it to an overseas aid agency. These readers seem to be acting at least as badly as Bob was acting when he chose to let the runaway train hurtle toward the unsuspecting child. In the light of this conclusion, I trust that many readers will reach for the phone and donate that $200. Perhaps you should do it before reading further. Now that you have distinguished yourself morally from people who put their 15 vintage cars ahead of a child’s life, how about treating yourself and your partner to dinner at your favorite restaurant? But wait. The money you will spend at the restaurant could also help save the lives of children overseas! True, you weren’t planning to blow $200 tonight, but if you were to give up dining out just for one month, you would easily save that amount. And what is one month’s dining out, compared to a child’s life? There’s the rub. Since there are a lot of desperately needy children in the world, there will always be another child whose life you could save for another $200. Are you therefore obliged to keep giving until you have nothing left? At what point can you stop? Hypothetical examples can easily become farcical. Consider Bob. How far past losing the Bugatti should he go? Imagine that Bob had got his foot stuck in the track of the siding, and if he diverted the train, then before it rammed the car it would also amputate his big toe. Should he still throw the switch? What if it would amputate his foot? His entire leg? As absurd as the Bugatti scenario gets when pushed to extremes, the point it raises is a serious one: only when the sacrifices become very significant indeed would most people be prepared to say that Bob does nothing wrong when he decides not to throw the switch. Of course, most people could be wrong; we can’t decide moral issues by taking opinion polls. But consider for yourself the level of sacrifice that you would demand of Bob, and then think about how much money you would have to give away in order to make a sacrifice that is roughly equal to that. It’s almost certainly much, much more than $200. For most middle-class Americans, it could easily be more like $200,000. 31 Isn’t it counterproductive to ask people to do so much? Don’t we run the risk that many will shrug their shoulders and say that morality, so conceived, is fine for saints but not for them? I accept that we are unlikely to see, in the near or even medium-term future, a world in which it is normal for wealthy Americans to give the bulk of their wealth to strangers. When it comes to praising or blaming people for what they do, we tend to use a standard that is relative to some conception of normal behavior. Comfortably off Americans who give, say, 10 percent of their income to overseas aid organizations are so far ahead of most of their equally comfortable fellow citizens that I wouldn’t go out of my way to chastise them for not doing more. Nevertheless, they should be doing much more, and they are in no position to criticize Bob for failing to make the much greater sacrifice of his Bugatti. At this point various objections may crop up. Someone may say: “If every citizen living in the affluent nations contributed his or her share I wouldn’t have to make such a drastic sacrifice, because long before such levels were reached, the resources would have been there to save the lives of all those children dying from lack of food or medical care. So why should I give more than my fair share?” Another, related, objection is that the Government ought to increase its overseas aid allocations, since that would spread the burden more equitably across all taxpayers. Yet the question of how much we ought to give is a matter to be decided in 20 the real world — and that, sadly, is a world in which we know that most people do not, and in the immediate future will not, give substantial amounts to overseas aid agencies. We know, too, that at least in the next year, the United States Government is not going to meet even the very modest United Nations–recommended target of 0.7 percent of gross national product; at the moment it lags far below that, at 0.09 percent, not even half of Japan’s 0.22 percent or a tenth of Denmark’s 0.97 percent. Thus, we know that the money we can give beyond that theoretical “fair share” is still going to save lives that would otherwise be lost. While the idea that no one need do more than his or her fair share is a powerful one, should it prevail if we know that others are not doing their fair share and that children will die preventable deaths unless we do more than our fair share? That would be taking fairness too far. Thus, this ground for limiting how much we ought to give also fails. In the world as it is now, I can see no escape from the conclusion that each one of us with wealth surplus to his or her essential needs should be giving most of it to help people suffering from poverty so dire as to be life-threatening. That’s right: I’m saying that you shouldn’t buy that new car, take that cruise, redecorate the house or get that pricey new suit. After all, a $1,000 suit could save five children’s lives. So how does my philosophy break down in dollars and cents? An American household with an income of $50,000 spends around $30,000 annually on necessities, according to the Conference Board, a nonprofit economic research organization. Therefore, for a household bringing in $50,000 a year, donations to help the world’s poor should be as close as possible to $20,000. The $30,000 required for necessities holds for higher incomes as well. So a household making $100,000 could cut a yearly check for $70,000. Again, the formula is simple: whatever money you’re spending on luxuries, not necessities, should be given away. Now, evolutionary psychologists tell us that human nature just isn’t sufficiently altruistic to make it plausible that many people will sacrifice so much for strangers. On the facts of human nature, they might be right, but they would be wrong to draw a moral conclusion from those facts. If it is the case that we ought 374 to do things that, predictably, most of us won’t do, then let’s face that fact headon. Then, if we value the life of a child more than going to fancy restaurants, the next time we dine out we will know that we could have done something better with our money. If that makes living a morally decent life extremely arduous, well, then that is 32 the way things are. If we don’t do it, then we should at least know that we are failing to live a morally decent life — not because it is good to wallow in guilt but because knowing where we should be going is the first step toward heading in that direction. When Bob first grasped the dilemma that faced him as he stood by that railway switch, he must have thought how extraordinarily unlucky he was to be placed in a situation in which he must choose between the life of an innocent child and the sacrifice of most of his savings. But he was not unlucky at all. We are all in that situation. Questions 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Peter Singer opens his essay by describing a situation from a movie, yet it could be argued that seeing movies is, in fact, a luxury that one advocating his position should forgo. To what extent does this interpretation undermine Singer’s argument? The example of Bob and his Bugatti is hypothetical. Is this a rhetorical strategy that strengthens or weakens Singer’s argument? Explain your response. Note the places where Singer addresses the counter-argument. Where does he concede, and where does he refute? When does Singer use the pronoun we? When does he use you? How does this shift reflect and contribute to appeals to ethos and pathos? This selection appeared in the New York Times Magazine (1999). What does that fact tell you about the audience to whom Singer is appealing? To what extent do you think he is effective in reaching them? Dec 19 2. World Economic Forum Zapiro The following cartoon by South African cartoonist zapiro (Jonathan Shapiro) takes as its context the World Economic Forum, a meeting of international leaders from business, industry, government, and academia who meet annually in Davos, Switzerland, to explore solutions to a wide range of global economic issues. 375 Questions 1. 2. How are the participants—both the two entering the room and those already inside — depicted? Consider appearance and activity. What does the setting illustrated resemble? Does it seem to be, for instance, a lecture hall? 33 3. What is a one-sentence summary of the argument that the cartoonist is making? Dec 20 3. Warren Buffett, Bill Gates, and the Billionaire Challenge Christian Science Monitor Editorial Board This 2010 article from the Christian Science Monitor describes the proposal of two superwealthy philanthropists to their billionaire counterparts. America’s super-wealthy are being hit up hard for their money on two fronts this year — for charity and for higher taxes. At the least, these new appeals may serve as a reminder for everyone in how best to give back to society. One front is a gentle arm-twisting campaign by Warren Buffett and Bill Gates to persuade fellow billionaires to commit half of their wealth to good causes. In just a few short weeks, the two men have won over 38 of those listed on the Forbes 400 list of wealthiest Americans to make that pledge. 376 About half of those asked have so far said yes, often saying they see their giving as an investment in society. Their names range from New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg to eBay founder Pierre Omidyar. In all, they have a combined net worth of more than $200 billion. But money for charity isn’t the main point. As Mr. Buffett, head of Berkshire Hathaway investments, said:“At its core, the Giving Pledge is about asking wealthy families to have important conversations about their wealth and how it will be used.” Such family and peer pressure certainly has its uses if they encourage generosity. The BuffettGates campaign in particular may also help create useful publicity for a broad political discussion about government tax rates. In coming weeks, Congress will decide whether to eliminate the Bush-era tax cuts for families earning more than $250,000—the other proposal to wrest money for the public good away from the rich. High-profile philanthropy by this large number of super-rich is indeed a rare display of heartfelt concern about others. It sets an example for those of more modest means to make more donations. “By giving, we inspire others to give of themselves, whether their money or their time,” says New York’s mayor, who earned his wealth publishing financial news. The Giving Pledge campaign may also help dampen the harsh rhetoric of class warfare in the coming fight over the Bush tax cuts. The willingness of both rich and poor to pay taxes—“the price of civilization,” as Justice Learned Hand called them — is critical to a functioning government. But the debate on Capitol Hill mostly centers on data and arguments from economists about the effects of tax rates on private investments and the budget deficit, or the tax burdens on each income group. Economics is not really a science, however, so it’s hard for either side to win those debates. Rather, the setting of tax rates is a democratic exercise, even though for many Americans the paying of taxes seems coercive — like an IRS agent citing jail time if you don’t pay up. That’s why each elected official must give voice to their constituents’ willingness to be taxed, just as Buffett and Mr. Gates have quietly drawn out the rich to say how much they would give to charity. 34 Sen. Barbara Boxer (D) of California is one lawmaker who says the rich are 10 ready to pony up more in taxes. “Those people who are making that kind of money, they’ve told me that they feel fine contributing to this country,” she says. Such statements are far better than the usual practice of demonizing the wealthy. But then Jon Kyl (R) of Arizona makes an opposing point by highlighting a wealthy smallbusiness man, Craig Fritsche, the owner of Tart Lumber in Virginia. “Do we need to raise taxes on people who create the jobs in our country?” asks Mr. Kyl. Congress sets the priorities for both government spending and taxes. Lawmakers must reflect the will of voters to contribute to the wider community, but 377 also persuade them to be taxed more — or on different types of income — when that is needed. It is the type of task that Gates and Buffett have learned well as they continue to hold private dinners with more billionaires to ask them to make the Giving Pledge. “We hope to come back in six months and surprise you more,” Buffett said, “or at least surprise ourselves.” Questions 1. 2. 3. What is the “Giving Pledge” proposed by Bill Gates and Warren Buffett to the Forbes 400 wealthiest Americans? Why do Gates and Buffett assert that “money for charity isn’t the main point” (para. 4) of their proposal? Why do they believe that their approach is better than imposing higher taxes on those earning the highest incomes? 35 Dec 21 Synthesis: Incorporating Sources into a Revision Following are two versions of an essay. The first is a draft that student Martin Copeland wrote in response to this prompt: Explain why you believe that fraternities 大学联谊会, sororities [联谊会], or both do or do not build community or provide a positive community environment for their members. The second essay is Martin’s revision after he researched the topic of fraternities and sororities further. Using the questions following each version of the essay, discuss specific ways in which the second is an improvement over the first, and suggest ways for further improvement. Draft From the outside, it is very difficult to tell exactly what fraternities and sororities do or don’t do for their members. What an outsider can do, however, is give an honest opinion of his or her perception of fraternities and sororities, which I feel, is very valuable to the organizations. It can allow members to understand how their organizations are perceived, what are the misconceptions, and why they may or may not be attracting new members. Having established my outside perspective, I believe that the general idea and philosophy of fraternities and sororities is to provide a positive community environment for their members, and that in their purest form, fraternities and sororities can do just that. Unfortunately, most fraternities and sororities are not in their “purest form,” and have been corrupted by wayward members so that now, they do not provide a positive community environment for their members. It is important to understand the language of “positive community environment.” Were the question only concerned with providing a community environment for their members, my answer would have been an enthusiastic “yes.” Fraternities and sororities are perhaps the closest groups on college campuses. On many campuses, they live, study, and party together. The “rush” process alone is enough to bring several wannabe members together as one cohesive unit. Often, within fraternities and sororities, students make lifetime friends and professional contacts; they build a support system away from home that for many students is the ship that keeps them afloat in the vast ocean that is college. The problem, however, lies in the fact that the question included the word “positive.” For all of the great things fraternities and sororities do for their members, much of it, though pleasurable, does not seem positive. We have all heard stories of fraternities and sororities placing their pledges in compromising and even dangerous situations all for the sake of brotherhood or sisterhood. Such stories are more frequent than these organizations would have the general public believe. The process that pledges have to endure to make it to the positive community environment can often humiliate them, bringing them down to the point that they feel that walking away from such a group would make the person less than the others. Admittedly, that brings into question the self-esteem of the pledge, but it also makes me question why an overwhelming number of students with self-esteem issues are drawn to fraternities and sororities. Instead of being uplifting societies focused on the growth and maturity of its members, the community environment can often become a crutch, which is anything but positive. SORE-OR-IT-EASE In essence, my argument is not that fraternities and sororities are bad, because without more specific definition of the terms analyzed, of course bad examples will run rampant. My argument, however, is that as a whole, it seems that fraternities and sororities have departed from their true purposes; they have lost touch with the principles and values upon which they were founded. Finding those principles again and rebuilding their lost legacies would be an amazing step toward becoming truly positive community environments, and it would take work from all such groups in order to fix the way outsiders perceive the groups as a whole. [535] Questions 1. 2. 3. The student has written in the first person, using both I and we. Is that decision appropriate or inappropriate for this assignment and topic? Why? What effect does the figurative language (“the ship that keeps them afloat,”para.3) have on you as a reader? What attempts does Martin make to develop a balanced tone and perspective? Give examples 36 HOMEWORK FOR DECEMBER 21 (WEDNESDAY): 1) Finish your videos and post on manageBac (with the marking sheet as well) by Thursday midday. 2) Rewrite your education essay if needed by Saturday. 3) Make sure you have sent the 8 homework tasks by tomorrow please: 1 2 Megestu article Home paragrap h Dec 6 Faceboo k4 Question s Dec 7 3 Faceboo k article q5 Dec 8 4 Gladwel l work Q1-4 5 Gladwel l work Q5-10 6 7 8 Morale s Poem Dec 13 Chast poem question s Dec 14 Singer article Question s Dec 19 37 DEC 22 Revision After writing the draft, Martin did some reading and research on the topic. The following revision shows his expanded view and use of sources. Fraternities and Sororities Martin Copeland From the outside, it is very difficult to tell exactly what fraternities and sororities do or don’t do for their members. What an outsider can do, however, is give an honest opinion of his or her perception to members to help them understand how their organizations are perceived, what the misconceptions are, and why they may have difficulty attracting new members. The general idea and philosophy of fraternities and sororities is to provide a positive community environment for their members, and in their purest form, they can do just that. Unfortunately, most fraternities and sororities are not in their “purest form” and have been corrupted 损坏 by what might be a minority of highly visible members. It is important to understand the language of “positive community environment.” Were the question concerned only with sororities and fraternities providing a community environment for their members, my answer would have been an enthusiastic yes. Fraternities and sororities are perhaps the closest groups on college campuses. On many campuses, they live, study, and party together. The “rush” process alone is enough to bring several wannabe members together as one cohesive unit. Often, within fraternities and sororities, students make lifetime friends and professional contacts. In his explanation of why he is proud to be part of a fraternity, Douglas Luetjen points out that “all but eight U.S. presidents since 1856 have been regular or honorary members of a college fraternity. And . . . 85% of the Fortune 500 executives are fraternity members.” Furthermore, in a sorority or a fraternity, students can build a support system away from home that for many is the ship that keeps them afloat in the vast ocean that is college. Anne Remington begins her article for Parent Times, an online magazine from the University of Iowa, with a story about a freshman who felt that no one remembered her birthday until her Alpha Chi Omega sisters began singing to her: “And in that instance, she knew she had found a new ‘home.’ ” Remington continues to describe Greek-letter organizations that appeal to specific minorities and that provide a “sense of belonging” for many students who are away from home for the first time. The problem, however, lies in the fact that the question included the word “positive.” For all of the great things fraternities and sororities do for their members, much of it, though pleasurable, does not always seem positive. We have all heard stories of fraternities and sororities placing their pledges in compromising and even dangerous situations all for the sake of brotherhood or sisterhood. Such stories are more frequent than these organizations would have the general public believe. The process that pledges have to endure to make it to the positive community environment can often humiliate them, bringing them down to the point that they feel that walking away from such a group would make them less than the others. A major problem with fraternities and sororities is drinking and the negative behaviors that accompany it. According to a study at the University of Washington, 85% of those living in Greek houses drank at least one to two times per week, 37% three to four times (Baer et al.). Another national study reported that sorority members are nearly twice as likely to become binge drinkers 酗酒者 than their non-sorority counterparts, and 75% of fraternity members were self-described binge drinkers (Wechsler). This study also reported higher incidences of missed classes and unprotected sex among fraternity and sorority members. In essence, my argument is not that fraternities and sororities are necessarily a negative community environment, but they do promote negative and potentially dangerous behaviors. As a whole, it seems that too many fraternities and sororities have become “organized saloons” 有组织的沙龙 (Cross) and departed from the principles and values upon which they were founded: “scholarship, relationships, leadership, and service” (Remington). Finding those principles again and rebuilding their lost legacies 失去的遗产 will be a step toward becoming truly positive community environments, though it will take the work of many individuals to change the way outsiders perceive fraternities and sororities. [674] Works Cited Baer, J.S., D. R. Kivlahan, and G.A. Marlatt. “High-Risk Drinking across the Transition from High School to College.” Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 19.1 (1995): 54–61. 38 Cross, Charles R. “Why I’m Proud I’m Not a Greek.” Columns: University of Washington Alumni Magazine September 2001: XX. Web. 6 Mar. 2004. <http://www.washington.edu/ alumni/columns/sept01/greekdebate1.html>. Luetjen, Douglas A. “Why I’m Proud I’m a Greek.” Columns: University of Washington Alumni Magazine September 2001: XX. Web. 6 Mar. 2004. <http://www.washington.edu/ alumni/columns/sept01/greekdebate1.html>. Remington, Anne. “It’s All Greek to Me.” Parent Times Online Winter 2004–2005: n. pag. U of Iowa. Web. 15 Mar. 2004. <http://www.uiowa.edu/~ptimes/issues04-05/ winter04-05/greek.html>. Wechsler, Henry. Binge Drinking on American College Campuses: A New Look at an Old Problem. Harvard School of Public Health (1995). Web. 20 Mar. 2004. <http:// www.hsph.harvard.edu/cas/Documents/monograph_2000/cas_mono_2000.pdf>. Questions 1. 2. 3. 4. Cite three changes Martin has made, and discuss their effect. The revised essay is written primarily in the third person. Is this point of view more effective? Why or why not? Do the sources Martin has chosen help to balance his argument, or do they favor one viewpoint? Do the sources give Martin’s voice more authority? If so, explain how. If you do not think so, explain why not. Did he cite his sources properly? How does that affect his authority? Homework to-do list for the Christmas Break: 1) Any missing homework tasks from this unit. (Deadline: today) 2) Your video (Deadline: today) 3) Rewriting education essay. (Deadline: Saturday) 4) Holiday homework MCQ Tests (See documents in WeCom) (Deadline: Wednesday 28th Dec) Take a screen shot of your answer page and send to me please. 39 383 Parallel Structures Sentences or parts of a sentence are parallel when structures within them take the same form. Parallelism is important at the level of the word, the phrase, and the clause. Words Why should we live with such hurry and waste of life? — Henry David Thoreau In this sentence, the words hurry and waste, both nouns, follow the preposition with; hurry and waste are parallel. In eternity there is indeed something true and sublime. — Henry David Thoreau In this sentence, the words true and sublime, both adjectives, modify the pronoun something; true and sublime are parallel. Phrases Men esteem truth remote, in the outskirts of the system behind the farthest star, before Adam and after the last man. — Henry David Thoreau To modify the adjective remote in this first sentence, Thoreau uses parallel prepositional phrases: in the outskirts, before the farthest star, before Adam, and after the last man. More difficult because there is no zeitgeist to read, no template to follow, no mask to wear. — Anna Quindlen And in the preceding sentence, Anna Quindlen uses three parallel nouns each preceded by no and each followed by an infinitive: no zeitgeist to read, no template to follow, and no mask to wear. clauses “Where I Lived, and What I Lived For” — Title of an essay by Henry David Thoreau 40 The title of Thoreau’s essay consists of two parallel dependent, or subordinate, clauses; one begins with where, and the other begins with what. [W]e perceive that only great and worthy things have any permanent and absolute existence, that petty fears and petty pleasures are but the shadow of the reality. — Henry David Thoreau The preceding example contains two parallel dependent clauses, each beginning with that and functioning as an object of the verb perceive. If we are really dying, let us hear the rattle in our throats and feel cold in the extremities; if we are alive, let us go about our business. — Henry David Thoreau This example begins with a dependent clause (If . . . dying) followed by an independent, or main, clause (let . . . extremities); then, after the semicolon, Thoreau presents another dependentindependent construction, parallel to the first. lack of Parallelism To fully appreciate the power of the parallelism created by Thoreau and Quindlen in the preceding examples, consider what happens when supposedly equal elements of a sentence do not follow the same grammatical or syntactical form— that is, when they are not parallel with each other. Why should we live with such hurry and to waste life? This version of Thoreau’s sentence tries to modify the verb should live by coordinating a prepositional phrase, with such hurry, with an infinitive phrase, to waste life. The two phrases are not parallel with each other, and as a result, the sentence lacks balance and force. Parallelism can be tricky when the elements — words, phrases, or clauses — are separated by modifiers or other syntactical elements. The following sentence may not at first glance seem to lack parallelism: It [the process of friendships fading] was sweet and sad and, though you’d rarely admit it, a necessity. 386 When you analyze carefully, you notice that sweet and sad are adjectives, and necessity is a noun. Notice that in the actual sentence that Scott Brown wrote in “Friendonomics,” he makes all three words parallel adjectives: It was sweet and sad, and though you’d rarely admit it, necessary. — Scott Brown The fact that all three are adjectives underscores the unity in the qualities Brown argues is the natural ebb and flow of friendships fading: it’s sweet and sad and also necessary. 41 Parallelism is often at its most effective at the level of the clause, but, again, it may be difficult to keep track. Let’s use an example from Malcolm Gladwell. Here it is without parallel structure: In other words, Facebook activism succeeds not by motivating people to make a real sacrifice but when people are motivated to do things even though they are not motivated enough to make a real sacrifice. That sentence makes sense—once you’ve untangled all the motivations!—but the emphasis Gladwell intends is on the not: people are not motivated by x but by y. In the sentence that actually appears in his essay, he repeats the phrase by motivating and thus uses parallel structure to emphasize the contrast: In other words, Facebook activism succeeds not by motivating people to make a real sacrifice but by motivating them to do the things that people do when they are not motivated enough to make a real sacrifice. — Malcolm Gladwell Rhetorical and Stylistic Strategy Looking first at the parallel sentences at the beginning of this lesson and then at the rewrites that lack parallelism, you can see that writers use parallelism on the level of the word, phrase, or clause as a rhetorical and stylistic device to emphasize ideas, to contrast ideas, or to connect ideas. Following are the names, definitions, and examples of specific types of parallelism: anaphora: Repetition of a word or phrase at the beginning of successive phrases, clauses, or lines. But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate-filled policemen curse, kick, and even kill your black brothers and sisters; . . . when you are forever 387 fighting a degenerating sense of “nobodiness” — then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait. — Martin Luther King Jr. In this example, form follows function. Just as King is saying that African Americans have had to endure unjust treatment as they waited for full civil rights, this series of parallel clauses makes the reader wait — and wait — for the main point in the independent clause. antimetabole: Repetition of words in reverse order. We do not ride on the railroad; it rides upon us. — Henry David Thoreau Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country. — John F. Kennedy 42 The example above from President Kennedy is, perhaps, his most famous quote. Part of what makes this quote so “quotable” is that the repetition inherent in antimetabole makes it dramatic and easy to remember. Because the pattern of the two clauses is so similar, the listener only needs to remember one pattern. Because that sentence pattern is repeated, it gives the listener two chances to understand the entire sentence and places extra emphasis on the second part. It is almost as if Kennedy is repeating a point for emphasis. Keep an eye out for antimetabole in modern political soundbites. antithesis: Opposition, or contrast, of ideas or words in a parallel construction. [F]reedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed. — Martin Luther King Jr. One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws. — Martin Luther King Jr. That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind. — Neil Armstrong In all three of these examples, the parallel structure creates a clear comparison between two things in order to emphasize the difference between them. Given by the oppressor is contrasted in meaning and in placement with demanded by the oppressed. Notice also how the parallel prepositional phrases by the oppressor and by the oppressed call attention to the tension between oppressor and oppressed. zeugma: Use of two different words in a grammatically similar way that produces different, often incongruous, meanings. Someone sent me a T-shirt not long ago that read “Well-Behaved Women Don’t Make History.” They don’t make good lawyers, either, or doctors or businesswomen. — Anna Quindlen zeugma: Use of two different words in a grammatically similar way that produces different, often incongruous, meanings. Someone sent me a T-shirt not long ago that read “Well-Behaved Women Don’t Make History.” They don’t make good lawyers, either, or doctors or businesswomen. — Anna Quindlen You are free to execute your laws and your citizens as you see fit. — Star Trek: The Next Generation 388 In this example, the zeugma is created when the verb make takes many different nouns as its direct object: history, but also, lawyers, doctors, and businesswomen. While all of these words are nouns, they do not have the same meanings — history is not an occupation, while all the other nouns are. There is a consistency in the pattern, but an inconsistency in the meaning of the words. Quindlen exploits the ironic inconsistency of the zeugma to draw a connection 43 between two things that her audience might not otherwise think of as connected: activists who fought for women’s rights, and women today who are trying to build their careers. • ExERCISE 1 • Identify the parallel structure in words, phrases, or clauses in each of the following sentences. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. “A penny saved is a penny earned.” (Benjamin Franklin) Was this act the work of a genius or a lunatic? This situation is a problem not only for the students but also for the teachers. Heather learned to work fast, ask few questions, and generally keep a low profile. After you finish your homework and before you check your email, please do your chores. • ExERCISE 2 • Correct the faulty parallelism in the following sentences. 1. My new exercise program and going on a strict diet will help me lose the weight I gained over the holidays. 2. As part of his accounting business, Rick has private clients, does some pro bono work, and corporations. 3. Try not to focus on the mistakes that you’ve made; what you’ve learned from them should be your focus instead. 4. A new job is likely to cause a person anxiety and working extra hours to make a good impression. 5. A competent physician will assess a patient’s physical symptoms, and mental attitude will also be considered. 389 • ExERCISE 3 • The following paragraph is from Toni Morrison’s Nobel Lecture, delivered in 1993 when she won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Find examples of parallel structure; identify whether the construction is a word, clause, or phrase; and explain its effect. The systematic looting of language can be recognized by the tendency of its users to forgo its nuanced, complex, mid-wifery properties for menace and subjugation. Oppressive language does more than represent violence; it is violence; does more than represent the limits of knowledge; it limits knowledge. Whether it is obscuring state language or the faux-language of mindless media; whether it is the proud but calcified language of the academy or the commodity driven language of science; whether it is the malign language of law-without-ethics, or language designed for the estrangement of minorities, hiding its racist plunder in its literary cheek — it must be rejected, altered and exposed. It is the language that drinks blood, laps vulnerabilities, tucks its fascist boots under crinolines of respectability and patriotism as it moves relentlessly toward the bottom line and the bottomed-out mind. Sexist language, racist language, theistic language— all are typical of the policing languages of mastery, and cannot, do not permit new knowledge or encourage the mutual exchange of ideas. 44 • ExERCISE 4 • Each of the following sentences is an example of parallelism. Identify the type of parallelism, explain its effect, and then model a sentence of your own on the example. 1. To spend too much time in studies is sloth; to use them too much for ornament is affectation; to make judgment wholly by their rules is the humour of a scholar. — Francis Bacon 2. Alas, art is long, and life is short. — Benjamin Franklin 3. Flowers are as common here . . . as people are in London. — Oscar Wilde 4. Where justice is denied, where poverty is enforced, where ignorance prevails, and where any one class is made to feel that society is in an organized conspiracy to oppress, rob, and degrade them, neither persons nor property will be safe. — Frederick Douglass 5. He carried a strobe light and the responsibility for the lives of his men. — Tim O’Brien Community Now that you have examined a number of texts that focus on community, explore this topic yourself by synthesizing your own ideas and the readings. You might want to do more research or use readings from other classes as you write. 1. Cell phones, e-mail, social networking sites, blogs, and other electronic communication have made our world smaller and increased the pace at which we live life. Have these inventions also given us a new sense of community or opened up communities that would otherwise be closed to us? Have they lowered or expanded our standards of what community means? 2. Write about the discussion that might ensue among several of the writers you have studied in this chapter if they were to focus on the following question: What are the characteristics of a productive and successful community at the start of the twenty-first century? 3. Examine a community that is organized around shared values but not geographic proximity. What holds that community together? What do members gain from it? Why does it continue? 4. The author Kurt Vonnegut Jr. wrote, “What should young people do with their lives today? Many things, obviously. But the most daring thing is to create stable communities in which the terrible disease of loneliness can be cured.” Write a speech that you would deliver to a group of your peers (identify which group) that uses Vonnegut’s idea as your main point and recommends ways to “create stable communities.” 45