Trichinella Tissue Nematode: Life Cycle, Pathogenesis

advertisement

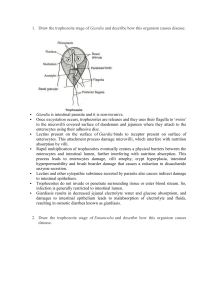

Access Provided by: Sherris Medical Microbiology, 7e Chapter 55: Tissue Nematodes TRICHINELLA TRICHINELLA SPIRALIS: PARASITOLOGY AND LIFE CYCLE Adult Trichinella live in the duodenal and jejunal mucosa of carnivores throughout the world, particularly swine, rodents, bears, canines, felines, and marine mammals. Originally thought to be members of a single species, it is now clear that arctic, temperate, and tropical strains of Trichinella demonstrate significant epidemiologic and biologic differences, and they have been reclassified into eight distinct species. Only two species, T spiralis and the arctic species T nativa, display a high level of pathogenicity for humans. This discussion focuses on the former, while highlighting the unique epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of the latter. Intestinal parasites of many flesh­eating mammals Within the host intestinal tissue, the tiny (1.5 mm) male copulates with his larger (3.5 mm) mate and, apparently spent by the effort, dies. Within 1 week, the inseminated female begins to discharge offspring. Unlike those of most nematodes, these progeny undergo intrauterine embryonation and are released as second­stage larvae. The birthing continues for the next 4 to 16 weeks, resulting in the generation of some 1500 larvae, each measuring 6 by 100 μm. From their submucosal position, the larvae find their way into the vascular system and pass from the right side of the heart through the pulmonary capillary bed to the systemic circulation, where they are distributed throughout the body. Larvae penetrating tissue other than skeletal muscle disintegrate and die. Those finding their way to striated muscle continue to grow, molt, and gradually encapsulate over a period of several weeks. Calcification of the cyst wall begins 6 to 18 months later, but the contained larvae may remain viable for 5 to 10 years (Figure 55–2). The muscles invaded most frequently are the extraocular muscles of the eye, the tongue, the deltoid, pectoral, and intercostal muscles, the diaphragm, and the gastrocnemius. If a second animal feeds on the infected flesh of the original host, the encysted larvae are freed by gastric digestion, penetrate the columnar epithelium of the intestine, and mature just above the lamina propria. This cycle is summarized in Figure 55–3. ✺ Larvae reach striated muscle and encapsulate but are still viable ✺ Eating infected flesh spreads the disease FIGURE 55–2. Trichinella spiralis larvae. A. Coiled larvae in a “squash prep” of deltoid muscle biopsy, in which a small sliver of muscle is squashed under the cover slip and examined without further fixation (image by Paul Pottinger MD). B . Coiled larva from a muscle digest. (Reproduced with permission from Connor DH, Chandler FW, Schwartz DQ, et al: Pathology of Infectious Diseases. Stamford, CT: Appleton & Lange, 1997.) Downloaded 2023­4­29 4:50 A Your IP is 196.190.249.247 TRICHINELLA, ©2023 McGraw Hill. All Rights Reserved. Terms of Use • Privacy Policy • Notice • Accessibility Page 1 / 5 FIGURE 55–2. Access Provided by: Trichinella spiralis larvae. A. Coiled larvae in a “squash prep” of deltoid muscle biopsy, in which a small sliver of muscle is squashed under the cover slip and examined without further fixation (image by Paul Pottinger MD). B . Coiled larva from a muscle digest. (Reproduced with permission from Connor DH, Chandler FW, Schwartz DQ, et al: Pathology of Infectious Diseases. Stamford, CT: Appleton & Lange, 1997.) FIGURE 55–3. Trichinosis. Trichinella spiralis larvae ingested by pig (1) eventually end up as human cysts (6). TRICHINOSIS Downloaded 2023­4­29 4:50 A Your IP is 196.190.249.247 TRICHINELLA, EPIDEMIOLOGY ©2023 McGraw Hill. All Rights Reserved. Terms of Use • Privacy Policy • Notice • Accessibility Page 2 / 5 Trichinosis, also called trichinellosis, is widespread in carnivores worldwide. Among domestic animals, swine are most frequently involved. They acquire the infection by eating dead rats or garbage containing cyst­laden scraps of uncooked meat. Human infection, in turn, results largely from the Access Provided by: TRICHINOSIS EPIDEMIOLOGY Trichinosis, also called trichinellosis, is widespread in carnivores worldwide. Among domestic animals, swine are most frequently involved. They acquire the infection by eating dead rats or garbage containing cyst­laden scraps of uncooked meat. Human infection, in turn, results largely from the consumption of improperly prepared pork products. In the United States, agricultural regulations have greatly reduced the incidence of trichinosis, and most pig­associated outbreaks have been traced to pork sausage prepared in the home or in small, unlicensed butcheries. Clusters have also followed feasts on wild pig in California and Hawaii. At present, however, the majority of human cases in the United States, particularly those in Alaska and other western states, have been attributed to consumption of wild animal meat, especially bear meat. Outbreaks among Alaskan and Canadian Inuit populations have followed the ingestion of raw T nativa­infected walrus meat. Outbreaks in Europe have involved horse meat or wild boar flesh. In other areas of the world, infection is commonly acquired from wild animals (“sylvatic sources”), including wild boar, bush pigs, and warthogs. Swine infected by eating rats or meat in garbage ✺ Human infection most often from undercooked pork or wild animals Human infections occur worldwide. In the United States, the prevalence of cysts found in the diaphragms of patients at autopsy has declined substantially. This decline has been attributed to decreased consumption of pork and pork products; federal guidelines for the commercial preparation of such foodstuffs; the widespread practice of freezing pork, which kills all but arctic strains of T nativa; and legislation requiring the thorough cooking of any meat scraps to be used as hog feed. Nevertheless, it is estimated that many Americans carry live Trichinella in their musculature and that more acquire it annually. Fortunately, the overwhelming majority has a small number of larvae and are asymptomatic. Only 5 to 15 clinically recognized cases are reported annually to federal officials. Prevalence declining as a result of meat inspection and cooking and freezing pork Human infections are usually subclinical PATHOGENESIS AND IMMUNITY The pathologic lesions of trichinosis are related almost exclusively to the presence of larvae in striated muscle, heart, and CNS. Invaded muscle cells enlarge, lose their cross­striations, and undergo basophilic degeneration. Intense inflammation surrounds the involved area, consisting of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and eosinophils. With the development of specific IgG and IgM antibodies, eosinophil­mediated destruction of circulating larvae begins, production of new larvae is slowed, and the expulsion of adult worms is hastened. A vasculitis demonstrated in some patients has been attributed to deposition of circulating immune complexes in the walls of the vessels. ✺ Larvae in striated muscle, heart, and CNS Acute inflammation with eosinophil­mediated destruction of larvae Downloaded 2023­4­29 4:50 AASPECTS Your IP is 196.190.249.247 TRICHINOSIS: CLINICAL TRICHINELLA, ©2023 McGraw Hill. All Rights Reserved. Terms of Use • Privacy Policy • Notice • Accessibility MANIFESTATIONS Page 3 / 5 One or two days after the host ingests tainted meat, the newly matured adults penetrate the intestinal mucosa, producing nausea, abdominal pain, and Access Provided by: Acute inflammation with eosinophil­mediated destruction of larvae TRICHINOSIS: CLINICAL ASPECTS MANIFESTATIONS One or two days after the host ingests tainted meat, the newly matured adults penetrate the intestinal mucosa, producing nausea, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. In mild infections, these symptoms may be overlooked, except in a careful retrospective analysis; in more serious infections, they may persist for several days and render the patient prostrate. Diarrhea persisting for a period of weeks has been characteristic of T nativa outbreaks after ingestion of walrus meat by the Inuit population of northern Canada. Larval invasion of striated muscle begins approximately 1 week later and initiates the more characteristic phase of the disease, which may last for about 6 weeks. Patients in whom 10 or fewer larvae are deposited per gram of tissue are usually asymptomatic; those with 100 or more generally develop significant disease; and those with 1000 to 5000 have a very stormy course that occasionally ends in death. Fever, muscle pain, muscle tenderness, and weakness are the most prominent manifestations of trichinosis. Patients may also display eyelid swelling, a maculopapular skin rash, and small hemorrhages beneath the conjunctiva of the eye and the nails of the digits. Hemoptysis and pulmonary consolidation are common in severe infections. If there is myocardial involvement, electrocardiographic abnormalities, tachycardia, or congestive heart failure may be seen. Central nervous system invasion is marked by encephalitis, meningitis, and polyneuritis. Delirium, psychosis, paresis, and coma can follow. Initial abdominal pain and diarrhea as adults penetrate gut wall ✺ Symptoms depend on number and extent of larval muscle invasion Severe complications include hemoptysis, heart failure, coma, and death DIAGNOSIS Trichinosis presents in a protean fashion, which can delay diagnosis and impact clinical outcomes. The most consistent laboratory abnormality is an eosinophilic leukocytosis during the second week of illness, which persists for the remainder of the clinical course. Eosinophils typically range from 15% to 50% of the white cell count, and in some patients, this may induce extensive damage to the cardiac endothelium. In severe or terminal cases, the eosinophilia may disappear altogether. Serum levels of IgE and muscle enzymes are elevated in most clinically ill patients. ✺ Eosinophilia up to 50% starting in second week There are a number of valuable serologic tests, including indirect fluorescent antibody and enzyme­linked immunosorbent assay. Significant antibody titers are generally absent before the third week of illness, but may then persist indefinitely. Biopsy of the deltoid or gastrocnemius muscles during the third week of illness often reveals encysted larvae (Figure 55–2B). Antibody usually appears after 2 weeks and then persists ✺ Muscle biopsy reveals Downloaded 2023­4­29 4:50 larvae A Your IP is 196.190.249.247 TRICHINELLA, ©2023 McGraw Hill. All Rights Reserved. Terms of Use • Privacy Policy • Notice • Accessibility TREATMENT Page 4 / 5 Access Provided by: Antibody usually appears after 2 weeks and then persists ✺ Muscle biopsy reveals larvae TREATMENT Patients with severe edema, pulmonary manifestations, myocardial involvement, or CNS disease are treated with corticosteroids. The value of specific anthelmintic therapy remains controversial. The mortality rate of symptomatic patients is 1%, rising to 10% if the CNS is involved. Mebendazole and albendazole halt the production of new larvae, but in severe infection, the destruction of tissue larvae may provoke a hazardous hypersensitivity response in the host. This may be moderated by initiating corticosteroids before treating with antihelminthics. ✺ Corticosteroids used in severe cases ✺ Antihelminthic therapy used with caution PREVENTION Control of trichinosis requires adherence to feeding regulations for pigs, and limiting contact between domestic pigs and wild animals, particularly rodents, who might be carrying Trichinella larvae in their tissues. Domestically, care should be taken to cook pork to an internal temperature of at least 76.6°C, or freeze it at −15°C for 3 weeks before cooking. Trichinella nativa in the flesh of arctic animals may survive freezing for a year or more. All strains may survive apparently adequate cooking in microwave ovens due to the variability in the internal temperatures achieved. ✺ Prevention via thorough cooking Downloaded 2023­4­29 4:50 A Your IP is 196.190.249.247 TRICHINELLA, ©2023 McGraw Hill. All Rights Reserved. Terms of Use • Privacy Policy • Notice • Accessibility Page 5 / 5