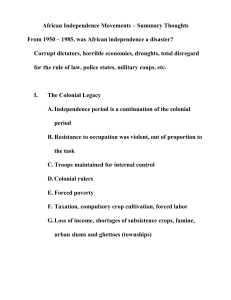

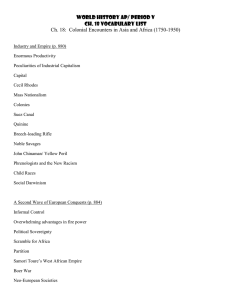

POLITICAL DECOLONISATION OF AFRICA after WWII Decolonisation: Decolonisation in this context refers to the process by which peoples in the global south gained independence from the colonial powers. Summary & context: The attitude of most of the colonial powers towards retaining political control of their colonies changed in the decades after WWII. A new world order with the USA and the USSR as the new superpowers developed after WWII, which favoured decolonisation. Subjected to various pressures after WWII, several colonial powers started thinking of granting independence but aimed to do so at a pace of their own choosing. The development of a more militant African nationalism during and after WWII hastened the independence process in Africa, as did pressure from the new superpowers and international organisations. Factors external to Africa: As a result of WWII, the colonial powers’ authority was shaken. Independence in Asia: - Britain, the Netherlands and eventually France were forced to give up their colonies in Asia. Britain, for example, was ultimately compelled in the period 1946-1951 to allow India, Pakistan, Burma and Ceylon to secure independence. - Once the process of decolonisation began, it gained its own momentum. It was initially India’s independence in 1947 that served as an inspiration to other colonised nations. - During the war, the European colonial powers were defeated by the Japanese in the Far East. The myth of their supposed invincibility/ superiority was thus destroyed. Cost of maintaining their colonies became expensive. - after WWII colonial powers had to focus on restoring their own economies. Colonial powers realised that the expense – financially and militarily – of maintaining their colonies was too great. Colonial policy shift after WWII: Colonial powers understood the need for decolonisation BUT wanted to control the pace…. - ‘Britain believed it would take some time since she felt she still had to train the nationalists in the business of running a modern state.’ (Afigbo, Anyandele, Gavin, Omer-Cooper, & Palmer, pp. 38-39) So, Britain, for example, envisaged that their colonies could be prepared for independence over the next fifty to a hundred years. - France: The French attempted to stall the granting of independence by offering financial aid for a slower process, or alternatively immediate independence without aid. Guinea was the only country who opted for immediate independence. - Other colonial powers like Portugal regarded their colonies as overseas provinces and would not even consider granting them independence at that time. Their colonies were among the last to receive independence, with Mozambique and Angola only securing independence in 1975. Zimbabwean independence was only secured in 1980, and South West Africa in 1990. Britain, for example, still retains control over several small islands. - Some colonial powers started to grant independence after WWII, but at a pace that would ensure that they remained in economic control of their former colonies. European attitudes changed post-Holocaust: - Racial superiority of Europeans – unacceptable! After WWII, the international community was made aware of the crimes committed by the Nazis in their attempts to assert the supremacy of what they claimed was the ‘Aryan master race’. There was worldwide horror at the genocide perpetrated by the Nazis in Europe. As a result, international opinion turned against colonialism as well as it too was premised on the supposed ‘racial superiority’ of Europeans. - It was increasingly believed that all peoples should have the right to rule themselves particularly in light of the horrific impact of Nazi notions of ‘racial supremacy’ as evident in the Holocaust perpetrated by the Nazis in Europe. ‘In the course of their conflict with Hitler, the Allied Powers had framed their propaganda in such a way as to rouse peoples in different parts of the world against Germany.’ (Afigbo, Anyandele, Gavin, Omer-Cooper, & Palmer) The Atlantic Charter: - In 1941, during WWII, President Roosevelt (USA)and Prime Minister Churchill (Britain) adopted the Atlantic Charter. It included the promise to respect the rights of all people to choose the form of government under which they lived. - Was welcomed by colonial nationalists as they believed it to mean that at the end of the war they would be granted, self-government and independence. - Americans gave much encouragement to colonial nationalists by openly attacking imperialism and supporting the demands of oppressed peoples for justice and self-government. - The Soviet Union campaigned openly for colonial independence at the UN. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights - equal rights for all. The United Nations Charter - Emphasised the rights of all nations to govern themselves. The UNO created forums for negotiation to take place and promoted the ideals of self-rule, thus contributing to the pressure on colonial powers to decolonise. - At the UNO, newly independent Asian countries lobbied for self-rule for all, pressuring the colonial powers to grant independence to their African colonies as well. Pressure from the new superpowers – the USA and the USSR: - Britain and France were no longer the dominant powers after WWII. This role was taken by the USA and the USSR who were anti-colonial rule as they wanted to benefit from the African territories securing their independence. Firstly, they needed support from African countries at the UNO during their Cold War rivalry. Secondly, the USA and the USSR had their own plans to exploit African resources economically, so they insisted on political decolonisation. - Britain and France thus started to grant independence in the decades after WWII, but at a pace that would – they believed – ensure they remained in economic control of their former colonies. They tried to placate independence demands through belatedly introducing reforms, improved access to education and some financial support. The growth of militant African Nationalism after WWII Philosophy and origins: - African nationalism was the assertion of African claims and African rights to self-rule in opposition to European control and authority. - It grew in response to long-standing and grievances against European control and authority, exacerbated by their treatment post-war. - Uhuru, the Swahili word for independence, came to represent the aims of African nationalists who wanted independence from European control. - African nationalists worked to overcome ethnic divisions and pride which obstructed the unity needed to compel the colonial powers to grant them independence - African nationalism brought together different ethnic groups, different social classes and men and women. - African nationalism grew from the associations that were formed in protest at the social and working conditions under which Africans were forced to live by their European colonisers. Rise of African Nationalism: - Summary of points from page 1 and 2 – Atlantic Charter; UN Charter; UN declaration of HR; military defeat of European powers by Japan; decolonisation in Asia. - Large numbers of African soldiers from colonies in Africa served in the Allied armies during WWII. They served alongside their colonial ‘masters’ and were part of an ostensible fight to ‘make the world safe for democracy’ against the tyranny of the Nazis. Many former servicemen questioned why the benefits of democracy did not similarly apply to them as Africans. They had fought for freedom from Hitler and the Nazis’ tyranny and were reluctant to remain unfree under colonial rule after the war. Those who had served battled to secure paid employment once back from the war front. They were aggrieved by the failure of the colonial powers to assist and support them. Subsequently, they played leading roles in the independence movements in their countries. They expected to be rewarded with independence for their role in defeating Hitler and the Nazis. They had fought for freedom and resisted remaining unfree and under colonial control after WWII. They claimed the Atlantic Charter signified that they too should secure liberation after WWII. Pan Africanism: - The idea that all Africans should be united. - Pan Africanism gained momentum inside Africa during and after WWII. - The Pan-Africanist movement, which aimed to rid Africa of colonial rule through united African action, grew at this time. It planned to restore pride in Africa and to unite different ethnic groupings in their fight for freedom while bridging class and regional differences too. - While it started amongst people in the African diaspora – outside of Africa – it took root in Africa itself. WEB du Bois and Marcus Garvey were two of the men who inspired the growth of Pan Africanism, and there were significantly inspirational women Pan Africanists both overseas and within the continent as well such as Shirley Graham du Bois. - Garvey called for ‘Africa for the Africans’, claiming also that all Africans share a common heritage. - Du Bois organised a series of pan Africanist conferences where Africans in the diaspora could meet to exchange ideas and mobilise for change. Pan-African conference 1945 (England) - Calls were made for a more militant stand through ‘Positive Action’ against the ongoing colonial rule in Africa. - The conference demanded an end to colonialism and the union of independent African states. - It called on all social classes to unite to achieve this. - It supported the use of strikes, boycotts and other forms of more militant action to compel the colonial powers to grant their independence. Pan-African Bandung Conference 1955 Indonesia - 23 Asian and African countries formed the Non-Aligned Bloc (i.e. neither aligned to the USA or the USSR in the Cold War). - They condemned colonialism in all its forms. - This clear show of solidarity further encouraged African nationalists in their struggle for independence. Ethiopia – occupied during WWII – regained its independence, inspiring the belief in other African territories that they too could secure their independence. Growth of African nationalist movements: - Urbanisation enhanced education opportunities for Africans in the cities. - African nationalism was encouraged by the impact of urbanisation which escalated during WWII. Urbanisation brought together different social and ethnic groups, men, women and the youth. They supported the growth of mass nationalist movements across the continent. - The urbanised middle class started demanding power themselves, while the urbanised working class became more militant as they were exposed to new ideas and methods, such as the strike. - The urbanised youth became decidedly impatient in their demands for change. They challenged the slow pace of change under the colonial powers. - Education increased the demands for freedom amongst the educated youth. Africans sent by mission schools to secure tertiary education in Europe and the USA were exposed to the ideals of democracy and self-determination there. Several among this highly educated elite returned home to lead independence movements. African nationalism intensified the pace of change, so that most African territories secured independence by the early 1960s. This excluded the Portuguese colonies in Africa, and the racist regimes in Rhodesia and South Africa. - - - -