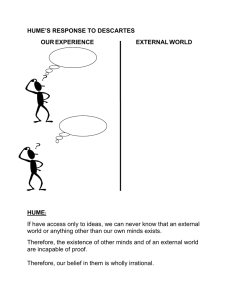

Ancient Philosophy - Classical antiquity - Started with Thales in the mid-6th century; but made Homer the true originator - Ended when the Christian emperor Justinian banned the teaching of pagan philosophy at Athens - Only Aristotle made contributions to the philosophical vocabulary of the ancient world - Product of Greece and Southern Italy, Sicily, western Asia, Egypt - Greek remained lingua franca Sixth & Fifth Centuries - Presocratic philosophy - Earliest practitioners: Thales, Anaximander, Anaximenes came from Miletus - Concerned with the origin and regularities of the physical world and the place of the human soul within it - Acknowledged that Socrates was the first philosopher to shift the focus away from the natural world to human values - Shifted to Sophists: fundamentals of political and social success with moral issues Fourth Century - Plato and Aristotle; dominant philosophies of the western tradition - Includes seminal studies by Plato and logic by Aristotle Hellenistic Philosophy - 4th century; search for universal understanding (biological and historical research) - Self-contained discipline - - - Alexandria became the new center of scientific, literary, and historical research 3 main parts of philosophy: ● Physics- speculative discipline ● Logic- epistemological ● Ethics- ultimate focus Dominant creeds: Stoicism, Epicureanism, Scepticism, Pyrrhonism Imperial Era - Final phase of ancient philosophy - gradually eclipsed by the revival of doctrinal Platonism, based on the close study of Plato’s texts - produced many powerfully original thinkers, of whom the greatest is Plotinus. Schools and Movement - normally started as an informal grouping of philosophers with a shared set of interests and commitments Resembled the structure of religious sects; birthing Christianity which became a serious rival to pagan philosophy Survival - knowledge of them depends on secondary reports of their words and ideas from other writers - strictly a ‘fragment’ is a verbatim quotation, while indirect reports are called ‘testimonia’ Medieval Philosophy - Philosophy of Western Europe - Christian thinkers left an enduring legacy of Platonistic metaphysical and theological speculation - medieval thinkers assimilated Aristotelian material and assimilated it into a unified philosophical system - Christianity; greatest thinkers of the period were highly trained theologians - enterprise of philosophical theology is one of medieval philosophy’s greatest achievements. - Disputation allows medieval philosophers to gather together relevant passages and arguments scattered throughout the authoritative literature and to adjudicate their competing claims in a systematic way - This provoked the hostilities of the Renaissance humanists whose attacks brought the period of medieval philosophy to an end Historical and Geographical Boundaries from the Latin expression medium aevum (the middle age) Beginnings - associated with the collapse of Roman civilization. Boethius, a Roman patrician, wanted to translate into Latin and write Latin commentaries on all the works of Plato and Aristotle - philosophers in the West depended on Boethius for what little access they had to the primary texts of Greek philosophy. - left subsequent generations of medieval thinkers without direct - - knowledge of most of Aristotle’s thought Medieval philosophy was therefore significantly shaped by what was lost to it and by the Latin language and Christianity Medieval philosophy, therefore, took root in an intellectual world sustained by the Church and permeated with Christianity’s texts and ideas. Historical Development the influx into the West of a large and previously unknown body of philosophical material newly translated into Latin from Greek and Arabic sources - emergence and growth of the great medieval universities. - Recovered texts of ancient greek philosophy Doctrinal Characteristics - Metaphysics: reality can be divided into substances and accidents. - Psychology and epistemology: nature of human beings in terms of the metaphysics of form and matter, identifying the human rational soul, the seat of the capacities specific to human beings, with form - Ethics: objectivist theory of value, a eudaimonistic account of the human good and a focus on the virtues as central to moral evaluation - Logic and language: - Natural philosophy: a complete account of reality must include an account of the fundamental constituents and principles of the natural realm. Modern Philosophy refers to an especially vibrant period in Western European philosophy spanning the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Most historians see the period as beginning with the 1641 publication, in Paris, of Rene Descartes' Meditationes de Prima Philosophiae (Meditations on First Philosophy), and ending with the mature work of the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, published in the 1780s. The philosophers of the period faced one of the greatest intellectual challenges in history: reconciling the tenets of traditional Aristotlean philosophy and the Christian religion with the radical scientific developments that followed in the wake of Copernicus and Galileo (and the succeeding Newtonian revolution). Established ways of thinking about the mind, the body and God were directly threatened by a new mechanistic picture of the universe where mathematically-characterizable natural laws governed the motion of life-less particles without the intervention of anything non-physical. In response, the philosophers (many of whom were participants in the scientific developments) invented and refined a startling variety of views concerning humans' relation to the universe. In so doing, they defined most of the basic terms in which succeeding generations would approach philosophical problems. The following article focuses on three central topics (skepticism, God, and the relation between mind and body) discussed in the philosophical systems of six major figures in the Modern period: Descartes, Spinoza, Locke, Leibniz, Berkeley and Hume. While these thinkers are typically seen as the most influential (and often, though not always, the most original) of their time, the list is nevertheless a sampling (especially notable omissions include Hobbes and Malebranche). Further details on the philosophers (including biographical details) can be found in the individual articles. ------------------------------------------------------Descartes The French philosopher Rene Descartes was a devout Catholic, a pioneering mathematician (he is credited with inventing algebraic geometry) and one of the most influential philosophers in history. His presentation of skeptical worries and the relation between the mind and body not only set the course for the rest of the Moderns, but are still the starting points for many contemporary discussions. Skepticism Descartes begins his Meditations by noting the worry that he may have many undetected false opinions, and that these falsities might cause his scientific proceedings to be built on unfirm foundations. This was not mere speculation on Descartes' part; he had had first-hand experience of Scholastic philosophy during his education, and had been shocked at the number of learned people who clearly believed a number of false things. The make sure that he would not someday be subject to a similar reproach, Descartes conceived of a simple yet powerful method for 'cleaning out' his beliefs: he would find the possible grounds for doubt he could, use those grounds to dissuade himself of as many beliefs as possible, and then only re-form beliefs that survived the most stringent examinations. It is worth emphasizing that Descartes saw skepticism as playing merely an ancillary role in this project - despite the misleading phrase 'Cartesian Skepticism' that is often found in other philosophers, Descartes never embraced skepticism as his final position. Descartes considered three increasingly strong grounds for doubt that could serve in his project. The first was that his senses were capable of being deceived, and that many of his beliefs were based on the deliverences of his senses. The second ground for doubt was the compatibility of all of his sensory experience with a deceptive dreaming experience, and the apparent impossibility of telling the difference. Both of those grounds, however, struck Descartes as insufficiently strong to throw into doubt as many beliefs as Descartes believed should be. We only find our senses to be deceptive under certain conditions (e.g., poor lighting). Though the possibility of dreaming might threaten our knowledge of the external world, it appears not to threaten certain pieces of general knowledge we possess (e.g. arithmetical knowledge). In light of this, Descartes presented his third and final ground for doubt: the possibility that he was being systematically deceived by an all-powerful being. God One of the things Descartes thought was least susceptible to even the strongest skeptical doubt was the presence in his mind of an idea of God as an infinite, perfect being. Descartes took the mere existence of this idea to provide the foundation for a proof of God's existence. In brief, Descartes saw no way that such a pure, non-sensory idea of something unlike anything else in our experience could have its source in anything less than God. This is often referred to as the 'trademark argument.' Descartes was also a proponent of the so-called 'ontological argument' for God's existence. As presented by Descartes, the argument states that the idea of God has a necessary connection to the idea of existence, in just the way that the idea of mountains has a necessary connection to the idea of low terrain (if all land were at the same altitude, there would be no mountains). So, Descartes claimed, just as it is impossible for us to conceive of a mountain without there being any low terrain, it is impossible for us to conceive of existence without there being a God. For Descartes, the proofs of God's existence played an absolutely indispensible role in his larger project, for, having established that he was created by an all-powerful yet benevolent (and so non-deceiving) God, Descartes could then place a great deal of trust in his cognitive faculties. One of the clearest examples of this appears in his discussion of the mind and body. Mind and body Descartes argued that the mind and body must be distinct substances, and so must be capable of existing independently of each others (this being implicit for him in the definition of 'substance'). Because he could clearly conceive of either his mind or his body existing without the other, and he had concluded that his ability to conceive was reliable (since it was produced by God), Descartes concluded that they must in fact be able to exist one without the other. ------------------------------------------------------Spinoza The Jewish philosopher Baruch Spinoza was regarded as one of the foremost experts on Descartes' philosophy in his day, yet presented a highly systematic philosophy that departed radically from Descartes on many points. His most important work was the Ethics, published posthumously in 1677. So extreme was much of Spinoza's thought, that the term 'Spinozist' became nearly synonymous with 'heretic' for the century after his death. Nevertheless, many of Spinoza's ideas bear a striking resemblance to much contemporary thought, and he is sometimes seen as one of the great advancers of the modern age. Skepticism Unlike Descartes, Spinoza believed that skepticism played no useful role in developing a solid philosophy; rather, it indicated that thought had not begun with the appropriate first principles. Spinoza thought that our senses give us confused and inadequate knowledge of the world, and so generate doubt, but that ideas of reason were self-evident. So for Spinoza, certain conclusions about the nature of the world could be reached simply by sustained application of intellectual ideas, beginning the idea of God. God One of Spinoza's most striking positions is this pantheism. Whereas Descartes believed that the universe contained many extended substances (i.e., many bodies) and many thinking substances (i.e., many minds), Spinoza believed that there was only one substance, which was both a thinking and an extended thing. This substance was God. All finite creatures were merely modifications of general properties of God. For instance, our minds are merely modifications of God's property (or 'attribute') of thought. In other words, our minds simply are ideas belonging to God. Mind and body Both the mind and body are modifications of God, according to Spinoza, yet they are modifications of two different attributes: thought and extension. Yet they bear a very close relation: the object of the mind (i.e., what it is that the idea represents) just is the physical body. Because of this, the two are 'parallel', in that every feature or change of one is matched by a corresponding change in the other. Further, Spinoza appears to hold that the mind and body are, at base, one and the same modification of God, manifested in two different ways. This underlying identity would then explain their parallelism. One of the advantages of this view (which has a striking resemblance to contemporary 'dual aspect' views of the mind and body) is that there is no need to explain how it is that the mind and body stand in causal relations - this being one of the chief objections to Descartes' view of them as distinct substances. Much of Spinoza's notoriety came from his denial of the immortality of the soul (or mind). Given the intimate relation he posited as holding between the mind and body, he was committed to the claim that the destruction of the body was inevitably accompanied by the destruction of the soul. Yet Spinoza believed that, in a certain sense, the mind did continue to exist, but only as an abstract essence in the mind of God, devoid of any specific features of its earlier personality. ------------------------------------------------------Locke The British philosopher John Locke published his monolithic Essay Concerning Human Understanding in 1689. Though his worked carried echoes of the work of Thomas Hobbes, Locke is generally seen as the first real proponent of what became known as 'British Empiricism.' His work is marked by an inclination to trust empirical evidence over the abstract reasonings, and so marks one of the earliest sustained attempts at developing a discipline of psychology. Skepticism Unlike Descartes or Spinoza, Leibniz did not believe that it is possible for us to attain perfect certainly about the existence of the external world or the reliability of our senses. He held that our senses did provide us with a weak sort of knowledge of the existence of external bodies, but did not see this as on par with the sort of knowledge we have of God's existence, or our own. This acknowledgment of our limitations nevertheless came with an appeal to the benevolence of God, albeit one of a somewhat different form than that presented by Descartes. Locke asserted that, as finite beings, we should recognize that God had merely given us cognitive powers sufficient to our tasks on earth, and that it was a mistake to attempt to try and stretch those powers beyond their natural boundaries. Locke, following Descartes, was impressed by the new mathematical approach to physics, and believed that the only properties truly in bodies are the properties describable in geometry (specifically, extension and motion). He termed these 'primary qualities.' Other properties (termed 'secondary qualities'), such as colors and sounds, merely reduce to the capacity of objects to produce ideas of colors and sounds in us via their primary qualities. But whereas our ideas of the mathematical properties resemble the properties in the objects that produce them, the same isn't true for our ideas of secondary qualities. Given this, it would appear that Locke would follow Descartes in claiming that minds must be distinct substances from bodies. While he does believe that that is the most probably position, however, Locke did not want to rule out the possibility that some physical objects were capable of thought. Unlike Descartes, Locke did not believe that our understanding of the nature of minds and bodies was sufficient to establish that result. God Locke denied that all humans have an innate idea of God, but he did believe that it was possible to demonstrate the existence of God merely on the basis of our own existence. In abbreviated form, his reasoning was that the existence of finite, thinking beings requires some causal explanation, and that the only sort of being capable of producing those beings (along with the rest of the universe) would be a thinking, eternal, maximally powerful being i.e., God. ------------------------------------------------------Leibniz The German philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz was one of the intellectual powerhouses of his day, not only developing a highly systematic philosophy, but also making pioneering developments in nearly every academic discipline (he invented a form of calculus simultaneously with Newton). Unlike the other Moderns, Leibniz never published a definitive statement of his views, though influential publications include the New System of Nature (1695) and the Theodicy of 1710. Mind and Body God Leibniz, like Descartes, accepted a version of the ontological argument for God's existence. Yet he also put forth a much more original (and controversial) argument. According to Leibniz, the best metaphysical picture of the universe was one in which infinitely many unextended, non-interacting, thinking substances (monads) existed with perceptual states that accurately represented (albeit in a confused way) the nature of all other monads in the universe. These states unfolded without any outside influence (so that monads are sometimes charicatured as wind-up toys). The only possible explanation for such a universe, Leibniz claimed, was an all-powerful, all-knowing God who instituted such a pre-established harmony at creation. According to Leibniz, God is best understood in terms of his infinite intellect and his will. God's intellect contains ideas of everything that is possible, so that God understands every possible way the world could be. Indeed, for something to be possible, for Leibniz, simply amounts to God having some idea of it. The only rule governing God's ideas was the 'principle of non-contradiction,' so that God conceived of everything possible, and all impossible things involved some contradiction. God's will, on the other hand, was characterized best by the 'principle of sufficient reason,' according to which everything actual (i.e., everything created by God) had a reason for its existence. Given this, Leibniz asserted that the only possible conclusion was that God had created the best of all possible worlds, since there could be no sufficient reason for him to do otherwise. Mind and body Leibniz believed that the universe must consist of substances, but that substances must be simple. All extended (physical) things, however, are capable of being broken down into parts, and so cannot be simple. In light of this, Leibniz concluded that the universe can, at bottom, only consist of non-physical substances with no spatial dimensions whatsoever. These, however, must be minds (the only type of things we can conceive besides bodies). The only properties minds have, however, are perceptions, so that on Leibniz's picture, the universe is exhaustively constituted by minds and their perceptions. This is often described as a form of idealism. Leibniz, like Spinoza, had been worried by how two distinct substances could interact (especially substances as distinct as the mind and body described by Descartes). This led Leibniz to the position mentioned above, according to which all substances operate in a non-interacting pre-established harmony. ------------------------------------------------------Berkeley George Berkeley was an Irish Bishop, theologian and philosopher who was both inspired by the philosophical advancements of Locke and Descartes, yet also worried that aspects of their philosophy were fueling the atheistic sentiments of the day. In his Principles of Human Knowledge (1710) and Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous (1713), he presented a bold theocentric philosophy that aimed to both change the direction of philosophy and re-establish the authority of common sense. Skepticism Berkeley believed that the central cause of skepticism was the belief that we do not perceive objects directly, but only by means of ideas. Once this belief is in place, however, we quickly come to realize that we are stuck behind a 'veil' of ideas, and so have no connection to reality. This same belief in objects that exist independently of our ideas, he thought, naturally led people to doubt the existence of God, since the operations of the universe were appearing to be entirely explicable simply by appeal to physical laws. Berkeley believed that these views rested on a straightforward philosophical mistake: the belief in the existence of 'material substance.' Mind and body Berkeley shared Locke's view that all of our knowledge must be based in our sensory experience. He also believed that all of our experience involves nothing more than the perception of ideas. According to such a view, the only notion we can possible have of the objects that make up the world is then one of objects as being collections of ideas. Not only did Berkeley think there was no motivation for positing any 'substance' 'behind' the ideas (as Locke explicitly had), but the very notion was incoherent; the only notions we have of existence come from experience, and our experience is only of perceiving things (such as our own minds) or perceived things (ideas), yet material substance, by definition, would be neither. Therefore, saying that material substance exists amounts to saying that something that neither perceives nor is perceived either perceives or is perceived. Given such a picture, it is a mistake to ask about how minds and bodies causally interact, unless this is a question about minds having ideas. Berkeley believed that there was nothing mysterious about how minds could generate ideas (something we do every day in our imagination), so he believed that this avoided Descartes' problem. God Most of our ideas, however, aren't ones that we make in our imagination. Berkeley noted that the ideas we create are faint, fleeting, and often inconsistent (consider our non-sensical daydreams). Yet we constantly find in our minds ideas that are vivid, lasting, intricate, and consistent. Because the only way we can understand ideas to be generated involves their being generated by a mind, and more powerful minds generate better ideas, Berkeley believed we could conclude that most of the ideas in our minds were created by some other, much more powerful mind - namely, God. Berkeley believed that such a picture would have very positive influences on people's faith. For, according to his picture, God is in near-constant causal communication with our minds, so that we cannot imagine that any of our actions or thoughts escape God's notice. ------------------------------------------------------Hume David Hume spent most of his life in his native Scotland, outside of several trips to France, where he enjoyed wild popularity. His first and most substantial philosophical work was the Treatise of Human Nature (published in 1739 and 1740). When that work failed to gain popularity, Hume reworked portions of it into the Enquire Concerning Human Understanding (1748) and the Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals (1751). Hume was widely regarded (probably accurately) as an atheist and (less accurately) as a radical skeptic, and the subtlties of his work were often overlooked. Today he is regarded by many as one of the most sophisticated and insightful philosophers in history. Skepticism Perhaps Hume's most famous argument concerns a certain type of inference known today as 'inductive inference.' In an inductive inference, one draws some conclusion about some unknown fact (e.g., whether the sun will rise tomorrow) on the basis of known facts (e.g., that the sun has always risen in the past). Hume looked closely into the nature of such inference, and concluded that they must involve some step that does not involve reason. 'Reason' as Hume saw it, was our capacity to engage in certain, demonstrative reasoning on the basis of the principle of contradiction. Yet there is no contradiction in the possibility that the sun might not rise tomorrow, despite it's having always done so in the past. The natural response to this worry is to appeal to something like the uniformity of nature (the view that things tend to operate the same way at different times across all of nature). For, if we assumed that nature was uniform, then it would be a contradiction if unobserved instances didn't resemble observed instances. But, Hume asked, how could such a principle of uniformity be known? Not directly by reason, since there is nothing contradictory in the idea of a non-uniform nature. The alternative would be that the uniformity is known by inductive inference. That, however, would require circular reasoning, since it had already been established that inductive inference could only proceed via reason if it assumed the uniformity of nature. Hume went on to conclude that our inductive inferences must therefore make use of some entirely different capacity. This capacity, Hume claimed, was that of custom, or our psychological tendency to come to form expectations on the basis of past experience. Exactly the same capacity is manifested in all other animals (consider the way that one trains a dog), so one of Hume's conclusions was that philosophers had been deluded in putting themselves, as rational creatures, above the rest of nature. Hume went on to claim that the exact same capacity is at the core of our concept of causation and our belief that objects continue to exist when we no longer perceive them. God Hume was thoroughly unimpressed by a priori proofs for God's existence (such as the ontological argument, or Leibniz's argument from pre-established harmony), yet he believed that empirical arguments such as Locke's required careful scrutiny. In the Enquiry, Hume presents a critique of arguments such as Locke's that infer properties of the cause of the universe (e.g., intelligence, benevolence) simply from properties of the effect (the universe). It clear, Hume claims, that in normal causal reasoning, one should not attribute any properties to an unobserved cause beyond those that were strictly necessary for bringing about the observed effect (consider someone concluding that aliens had visited earth after finding a twisted piece of metal in the woods). Yet this appears to be exactly what the Lockean argument is doing. In his posthumous Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, Hume subjected such arguments to even further scrutiny. Of particular note (and of particular relevance to contemporary debates) is his regress worries concerning arguments from design. If, Hume argued, one is entitled to infer that the universe must have some sophisticated, intelligent cause because of its complexity, and one infers that such a cause must exist, then one must further be entitled to assume that that intelligent cause (being at least as complex as its creation) must likewise have some distinct cause. If one insists that such a being would need no cause, however, then it would appear that one had no basis for inferring the universe must also have a cause.