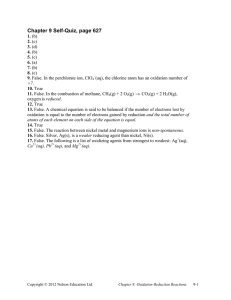

Is Black Pad still an issue for ENIG George Milad Uyemura International Corporation Southington CT Over the past ten years composite coatings of electroless nickel-phosphorous and immersion gold have become established as the preferred solderable surface finish for high reliability applications involving complex circuit designs. Commonly referred to as ENIG, the electroless nickel immersion gold finish has gained market share due to its versatility in a wide range of component assembly methods including solder fusing, wave soldering, and wire bonding and the ease with which it transitioned to lead free assembly. The ENIG finish provides a highly solderable flat surface that does not tarnish nor discolor. It has a long shelf life and the precious metal topcoat provides excellent electrical continuity. The nickel serves as a barrier against copper diffusion and prevents copper contamination of the solder during wave soldering and rework operations. About 8 years ago a major OEM brought to the attention of the industry a low level of inter connect failures, when ENIG was used as the surface finish. The failure mode is associated with a poorly formed joint at the solder/nickel interface. When the suspect joint is stressed, the connection is easily broken leaving an open circuit, with dark corroded nickel, commonly referred to as “BlackPad” Initially it was thought that the cause was the formation of Au/Sn intermetallic, It is now well understood that gold is not part of the intermetallic which is strictly Ni/Sn. Another initial thought was that phosphorous enrichment at the solder joint interface caused the Black Pad. A phosphorous rich layer is a natural component of the Ni/Sn solder joint. Subsequent investigations have shown that excessive nickel corrosion during the immersion gold deposition causes this condition, now commonly referred to as “black nickel” or “black pad”. The immersion reaction by which the gold displaces the nickel is a displacement or corrosion reaction that does not produce black pad or soldering defects. So what is excessive corrosion of the nickel and how does it occur? Fig 1 shows a 5000X SEM micrograph of a corroded nickel surface after gold stripping. An irregular topography with distinct crevices between the domains is where corrosion initiates and may cause black pad. . Fig. 2 shows a 5000X SEM micrograph of a non-corroded nickel surface after gold stripping. The nickel deposit exhibits an even topography. This nickel deposit will never produce a black pad. Irregular topography can be caused by a contaminated incoming copper surface or inadequate pre-treatment in the front end of the ENIG line, in addition the nickel bath itself could create the irregularity during the course of deposition. The nickel bath is constantly plated and replenished, this operation must be controlled to ensure the desired outcome. A compromised deposit will occur from by-product build up, if the bath is operated beyond its recommended bath life. Another cause is a higher than normal FIG 1 FIG 2 SEM of Ni Corrosion SEM of Ni Surface deposition rate resulting from high temperature and/or pH, operating outside the recommended range. A well controlled nickel bath is the key to the elimination of the defect. Since the “black pad” occurs during the gold deposition step, what is the role of the gold bath if any in creating the defect? Ideally for every one atom of nickel metal oxidized to nickel ion, two gold atom are reduced to gold metal. The nickel released into the gold bath over time should follow the stoichometry of the chemical reaction. If the amount of nickel produced exceeds the calculated value, the immersion gold bath is labeled “aggressive”. Aggressive gold bath are more prone to producing “black pad” from a compromised nickel surface. The best choice of an immersion gold bath is one where the nickel exchange with the gold is closest to ideal. Not all gold baths are created equal. Over time two major developments in ENIG deposition have occurred. The first is the awareness of the suppliers and manufacturers of the criticality of the process control in the ENIG line. Shops that implement process control and are iso-9000 certified stay clear of this problem. Buyer beware, you get what you pay for. The second major development is the IPC-4552 ENIG specification. The document specifies minimum 2 uins (presently in revision to lower the spec limits) of immersion gold, contrary to previous beliefs that more gold is better for solderability. It is now clear, to all, that the gold is only there to protect the nickel until it is soldered to. Minimizing the dwell time in the gold bath to meet the specification has gone a long way in virtually eliminating the occurrence of “Black Pad”. A revised specification IPC-4552 Rev A is complete and in final draft; it will specifies the gold thickness at a minimum of 1.6 uins and a maximum of 4.0 uins. The final specification is expected to be out by the end of 2016. In spite of all this understanding of the defect, the term “Black Pad” is buzzing around in the industry. Any soldering defect that involves ENIG is first labeled “Black Pad” and them maybe it is objectively investigated. Most of the alarms with this label, turn out false after a thorough investigation is conducted. Like any other chemical process in manufacturing of PCB, if the process is not controlled and run to vendor specification the results lead to defective product. Immersion silver, can form “champagne voids”, it can corrode and it also tarnishes. Immersion tin forms intermetalic Cu/Sn sitting on the shelf, and may also form whiskers. OSP’s were shown to corrode in specific environments. Clearly the world is moving on with all of these surface finishes and they work, and work well. In today’s sophisticated electronic manufacture process control is the only ticket to continuous success. F i g u r e