International Journal of Industrial Organization 67 (2019) 102532

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

International Journal of Industrial Organization

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijio

Pay-for-delay patent settlement, generic entry and welfareR

Yucheng Ding a, Xin Zhao b,∗

a

b

Economics and Management School, Wuhan University, China

School of International Trade and Economics, University of International Business and Economics, China

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 22 May 2018

Revised 27 August 2019

Accepted 4 September 2019

Available online 13 September 2019

JEL classification:

I18

I11

K21

Keywords:

Pay-for-delay settlement

Generic entry

Pharmaceutical competition

Innovation

a b s t r a c t

“Pay-for-delay” settlement (P4D), in which the brand patentee reversely pays the generic

infringer to delay market entry, is typically criticized for blocking competition but is often

excused for its potential to maintain innovation. We present a game-theoretic model to

show that when the generic firm’s entry decision is endogenized, P4D can actually increase

ex post competition under certain conditions. We further explore the impact of P4D on ex

ante innovation and find that the brand’s innovation incentive may increase or decrease,

depending on the generic firm’s entry cost and other factors. Our findings contribute to the

ongoing P4D debate by identifying conditions under which (1) P4D can improve consumer

surplus and (2) the trade-off between competition and innovation can be reconciled.

© 2019 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Balancing innovation and competition is a challenging goal for policy makers worldwide. The issue has been highlighted

by the recent debate over “pay-for-delay” settlement (P4D), which involves the brand patentee reversely paying the generic

infringer to delay pre-expiration entry. On the one hand, P4D blocks competition and is thus opposed by antitrust authorities in both the United States and the European Union.1 On the other hand, industry observers are concerned that generic

entry reduces effective patent life and suggest that allowing P4D may help to maintain innovation incentives and benefit

consumers in the long run (Grabowski and Kyle, 2007; Higgins and Graham, 2009). Antitrust and intellectual property policies come into conflict in the case of P4D, and its complexity has given rise to inconsistent judicial findings regarding its

legality.2 In reality, P4D arises not only in the multi-trillion dollar pharmaceutical industry but can occur in any market

R

We thank the editor Armin Schmutzler and three anonymous referees for very helpful suggestions. We also thank Yongmin Chen, Jianpei Li, Marius

Schwartz, Tianle Zhang and participants in The 9th Biennial Conference in Hong Kong and The 2017 China Meeting of the Econometric Society for their

helpful comments. Xin Zhao acknowledges funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71704024). Yucheng Ding acknowledges funding

from the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities. All errors are ours.

∗

Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: yucheng.ding@colorado.edu (Y. Ding), xin.zhao@uibe.edu.cn (X. Zhao).

1

Since 2001, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has filed a number of lawsuits to stop P4D, which is estimated to cost consumers $3.5 billion annually

(FTC, 2010). The European Commission (EC), for another example, fined Johnson & Johnson and Novartis approximately $20 million in 2013 after detecting

their intention to delay the market entry of a generic version of the painkiller fentanyl.

2

The rulings range from per se illegal (in the Sixth Circuit 2003) to almost per se legal (in the Second Circuit 2006) to something in between with a Rule

of Reason test (in the Federal 2008, Eleventh Circuit 2005, and Supreme Court 2013 (FTC v. Actavis, Inc., 133 S. Ct. 2223, 2227 (2013)).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijindorg.2019.102532

0167-7187/© 2019 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

2

Y. Ding and X. Zhao / International Journal of Industrial Organization 67 (2019) 102532

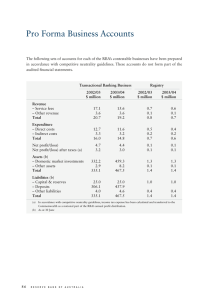

Fig. 1. Share of new molecules experiencing Paragraph IV challenges by year: 1995–2013. 1 Medicare Modernization Act requires the disclosure of P4D

2 Appellate courts overrule the FTC and declare that P4D is not inherently anti-competitive.

3 The Supreme Court subjects

to the FTC for antitrust review.

P4D to the scrutiny of rule-of-reason in Actavis v. FTC, and the EC rules P4D per se illegal in the case of Lundbecks drug citalopram. Sources: IMS Health

National Sales Perspectives, Food and Drug Administration data, McCaughan (2017) and Grabowski et al. (2016).Note: A generic challenge via Paragraph

IV occurs prior to patent expiration and involves a Paragraph IV certification claiming that the patent is invalid or non-infringed by the marketing of the

generic product. See Section 2 for details. Paragraph IV is not essential to the model, and our analysis applies to reverse payment settlements not only in

the U.S. but also in Europe.

where the patent holder would have greater market power if the entrant were excluded (Elhauge and Krueger, 2012), and

its effects are definitely worth exploring.

To examine the overall effects of P4D, we borrow the classic framework from Bebchuk (1984) and establish a gametheoretic model to characterize the firms’ competition and innovation strategies. In contrast to the traditional approach,

we treat the generic firm’s entry decision as endogenous. The possibility that P4D induces more generic entry is often

overlooked but is supported by recent evidence. Fig. 1 displays the share of new molecules experiencing generic challenges

between 1995 and 2013. The number rises as the legal landscape becomes more P4D-friendly and falls if the opposite is

true. For example, in 2003, when pharmaceutical firms were required to disclose P4D to the FTC, the share of new molecules

facing challenges began to decline after 8 years of growth. Around 2005, with multiple courts having declared that P4D does

not violate antitrust rules, we observe an immediate increase in the share of drugs being challenged.3 The decline in 2013

also coincides with the Supreme Court and the EC’s decision to subject P4D to antitrust scrutiny. The co-movement of the

prevalence of generic challenges and the legality of P4D provides supportive evidence of endogenous generic entry.

In this paper, we endogenize the generic firm’s entry decision and obtain three key findings. First, P4D may actually increase competition. When P4D is allowed, the generic firm expects higher profit and is more likely to initiate pre-expiration

entry. We further assume that there is information asymmetry between the brand and the generic firm such that they

sometimes fail to reach an agreement despite having incentives to settle and collude. As a result, part of the induced challenges becomes effective entry and increases competition. Moreover, we find that P4D is more likely to improve competition

when the entry cost is at an intermediate level. Otherwise, P4D is either insufficient (when the entry cost is too high) or

unnecessary (when the entry cost is low) to encourage generic entry and thus either exerts no influence or purely creates

collusion that suppresses competition.

Second, P4D has a heterogeneous effect on the brand-name firm’s innovation incentive, defined as the premium of a

high-quality patent over a low-quality patent. The effect also depends substantially on the entry cost. When the entry cost

is at intermediate level, P4D increases innovation. This is because, in this region, the entry-inducing effect of P4D is relatively

weak, and thus, P4D can only induce entry and reduce profit if the patent quality is low, while it has no impact if the patent

quality is high. In other words, P4D raises the relative attractiveness of a high-quality patent. When the entry cost is low,

P4D decreases innovation. The reason is that the entry-inducing effect of P4D is strong enough to offset both patents’ ability

to foreclose entry and therefore disproportionately reduces the value of a high-quality patent.

Finally, P4D might increase or decrease consumer surplus. When the entry cost is at intermediate level, P4D simultaneously enhances competition and innovation. The two seemingly contradictory goals can be aligned. When the entry cost is

relatively low, ex ante innovation is weighed against ex post competition, and the impact of P4D on consumer surplus then

further depends on the brand-name firm’s innovation cost. When the entry cost is sufficiently low, P4D reduces both competition and innovation and ultimately consumer surplus. In addition, there is sufficient variation in the entry cost based

3

The 11th circuit concluded that P4D did not violate antitrust law in Schering-Plough Corp v. FTC and Actavis v. FTC. A district court arrived at similar

result in Actavis v. FTC.

Y. Ding and X. Zhao / International Journal of Industrial Organization 67 (2019) 102532

3

on estimates from the literature. The average entry cost is $5 million, with a range from $250,0 0 0 to $20 million, and the

expected profit of a generic challenge is $5.5 million (Morton, 1999; Hemphill and Sampat, 2013). Given the numbers, we

believe that the fraction of potential entrants prevented by entry costs is non-negligible, and allowing P4D to induce entry

is meaningful not only theoretically but practically.

Literature review

First, this paper is closely related to the economic literature on antitrust implications of patent settlements with reverse

payment. While most scholars believe that patent settlement with reverse payments is anti-competitive (Janis et al., 2003;

Elhauge and Krueger, 2012; Edlin et al., 2013; Drake et al., 2014), some argue that P4D can be pro-competitive through

saved litigation costs (Elhauge and Krueger, 2012) or reduced business risks (Yu and Chatterji, 2011). Two papers informally

discuss the conditions under which P4D can be pro-competitive. Willig and Bigelow (2004) speculate that P4D can improve

welfare even if the reverse payment exceeds the litigation cost. Padilla and Meunier (2016) suggest that P4D may have

pro-competitive effect when multiple generic entrants exist or there is information asymmetry. In 2013, the Supreme Court

promulgated the “Actavis Inference” in FTC v. Actavis, Inc. Various papers discuss how to interpret this inference. For example,

Edlin et al. (2015) propose a simple rule to evaluate whether P4D is anti-competitive. They believe that the settlement

should be illegal if the branded firm has paid the generic firm a large amount of cash or something else of value, which

is much higher than the litigation cost, and the generic firm agrees to deter entry. Harris et al. (2014) argue that the P4D

judgment is complex and that the simple rule in Edlin et al. (2015) may exclude some pro-competitive P4D settlements.

Our main contribution is to highlight the importance of endogenous entry in evaluating the competitive effect of P4D.

Recent studies have begun to lend empirical support for the existence of endogenous entry (Jacobo-Rubio et al., 2017) and

consider theoretically the entry-inducing effect of P4D.4 For instance, Böhme et al. (2017) exploit the positive effects of inducing more generic challenges to justify the longer collusion caused by P4D. We contribute by further incorporating innovation and examining how entry-inducing effects influence the tradeoff between ex post competition and ex ante innovation.

These considerations allow us to establish a more complete set of welfare determinants and more effectively differentiate

welfare-improving P4D from others.5

Second, this paper deepens our understanding of the impact of P4D on innovation incentives. The common belief is that

P4D promotes innovation, although some scholars argue that P4D undermines the optimal innovation incentives because

it endows the brand with supracompetitive profits (Elhauge and Krueger, 2012). Our model shows that the impact of P4D

on innovation is heterogeneous and suggests that the observed inconsistency can be explained by the entry-inducing effect

of P4D. Specifically, in cases in which P4D induces entry, the supracompetitive profits suggested by Elhauge and Krueger

(2012) are not in fact guaranteed. Given that a high-quality patent is more capable of deterring generic entry, P4D increases

the value of high-quality patents and promotes innovation. P4D reduces innovation in other cases in which P4D does not

induce entry, and the supracompetitive profits are secured.

Recently, several theoretical papers examine why and when P4D settlements occur. Bokhari et al. (2017) find that allowing the branded firm to issue its authentic generic drugs will reinforce P4D deals in equilibrium. Palikot and Pietola

(2017) discover that patent strength matters: cases with patents that are too strong or too weak are most likely to be

settled. Both papers investigate P4D with multiple generic entrants and involve a settlement externality. In Section 6, we

also propose a simple sequential entry model and discuss how the pressure to settle with later generic challengers breaks

down the settlement between the branded firm and early challengers. However, the key insight of our paper is that generic

challenges are endogenous and that the legality of P4D may influence this incentive, which is not addressed in previous

theoretical papers.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 provides the institutional background. Section 3 establishes

a benchmark model to study the effect of P4D on ex post competition. Section 4 examines the impact of P4D on ex ante

innovation incentives. Section 5 studies the welfare implications of P4D, combining ex post competition and ex ante innovation. Section 6 conducts several extensions and robustness checks. Section 7 summarizes and discusses our findings. All

proofs are relegated to the Appendix.

2. Background

2.1. Generic entry and the Hatch–Waxman Act

The Hatch–Waxman Act of 1984 plays an important role in catalyzing generic entry prior to patent expiry. It exempted

the generic entrant from conducting various large-scale human trials associated with the approval process for an entirely

new medicine. Instead, the generic entrant only needs to demonstrate the bio-equivalence of its product to the original

counterpart in its filing of an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).6 The

4

Dickey and Rubinfeld (2012) show that allowing P4D may increase the generic firm’s innovation incentive and induces more challenges, which is similar

to our paper. However, we formally model this idea and also consider the branded firm’s innovation decision.

5

The welfare refers to consumer surplus throughout the paper.

6

Bio-equivalence is defined by the FDA as “the absence of a significant difference in the rate and extent to which the active ingredient or active moiety

in pharmaceutical equivalents or pharmaceutical alternatives becomes available at the site of drug action when administered at the same molar dose under

similar conditions in an appropriately designed study.”

4

Y. Ding and X. Zhao / International Journal of Industrial Organization 67 (2019) 102532

Fig. 2. Timing of a typical generic challenge via Paragraph IV.

test for bio-equivalence is typically done by “measuring the time it takes for a generic drug to reach the bloodstream in 24

to 36 healthy volunteers” and “determining the generic drug’s rate of absorption” (FDA).

In addition, the FDA provides the patent information on original drugs in the Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic

Equivalence Evaluations (commonly known as the Orange Book). By studying the Orange Book on the FDA’s website, the

generic firm can identify the New Drug Application (NDA) of the original drug and determine whether to claim that the

patent is invalid or non-infringed via a Paragraph IV certification.7 If the generic firm succeeds in the Paragraph IV challenge,

it can enter the market prior to patent expiration. By the end of the 20 0 0s, Paragraph IV challenges accounted for more than

40% of generic entry (Higgins and Graham, 2009; Berndt et al., 2007).

Under the ANDA process, the generic challenge still incurs costs. The costs comprise all kinds of payments for assessing

the market, filing the application, and most important, determining how to make the drug while evading the branded firm’s

patent portfolio (Hemphill, 2009). The entry cost ranges from $250,0 0 0 to $20 million, with an average of $5 million (Tang,

2013; Morton, 1999). Although much less than in a regular NDA, the costs associated with ANDA are non-negligible and

present substantial variations in the industry.

2.2. Generic challenge and P4D settlement

Fig. 2 demonstrates the timing of a typical generic challenge via Paragraph IV. First, the generic firm G files an ANDA.

Upon receiving a notice of Paragraph IV certification, the branded firm B has the right to initiate an infringement suit against

the challenger within 45 days. If sued, G cannot market its product unless the court decides that the patent is invalid or

non-infringed. Before the court announces its ruling, B and G sometimes reach a settlement agreement in which G abandons

the patent challenge in exchange for financial compensation from B. All the above usually occurs before the patent expires.

Several points are worth noting about the generic challenge process. First, although firms share most knowledge in the

public sphere, there might exist information asymmetry between the branded and generic firms.8 A brand-name manufacturer often has a better understanding of the validity or enforceability of its own patent. For example, the branded firm’s

private knowledge of the homologues, isomers, and hydrates involved in the process of making the product helps it better

solve the controversy regarding the non-obviousness of the patent. Of course, the generic entrant might also possess some

private information that helps it assess its odds of winning in the patent litigation. For instance, the ANDA is kept confidential before the generic firm challenges the patent. However, after filing the Paragraph IV certification, the generic firm

should include a description of the product, which must be sufficiently detailed to allow the brand patentee to determine

whether to sue. Therefore, the branded firm is more likely to have an information advantage in patent litigation.

Asymmetric information helps to explain why P4D is not always reached despite having the potential to secure tremendous profits for both parties. As shown in Fig. 3, the fraction of generic challenges that end up with P4D is not high as expected and particularly low between 2004 and 2009. One possible explanation is that the information asymmetry between

the two parties on their likelihood of prevailing in court prevents them from reaching an agreement on the settlement.

Following Bebchuk (1984), we model the information asymmetry and generate results that are consistent with the observed

variations in the outcomes of generic challenges.

Another important institutional feature is that entry might involve multiple generic challengers. Recently, the average

number of Paragraph IV challengers per molecule per year has been 4.6 (Grabowski et al., 2016). Upon an initial court

ruling in favor of the generic, the FDA may approve the ANDA, and other firms that file Paragraph IV certifications can enter

the market. The subsequent generic entry may not be immediate, because the first successful generic challenger is entitled

to a 180-day marketing exclusivity period under certain circumstances.

7

The other three types of certification are associated with post-expiration generic entry, according to 21 USC Section 355(j)(2)(A)(vii). “An ANDA shall

contain] a certification, in the opinion of the applicant and to the best of his knowledge, with respect to each patent which claims the listed drug or which claims

a use for such listed drug for which the applicant is seeking approval(I) that such patent information has not been filed,(II) that such patent has expired,(III) of

the date on which such patent will expire, or(IV) that such patent is invalid or will not be infringed by the manufacture, use, or sale of the new drug for which

the application is submitted”.

8

The public information includes the description of the patent in the Orange Book and the estimated success rate of generic challenges. For example,

the success rate is approximately 48% among the patent cases litigated in district court decisions during the period 20 0 0–2012 (Grabowski et al., 2014).

Y. Ding and X. Zhao / International Journal of Industrial Organization 67 (2019) 102532

5

Fig. 3. Number of Paragraph IV patent filings and P4D agreement by fiscal year: 2004–2014.

Note: Bureau of Competition (FTC, 2015).

3. The benchmark model

Assume that we have a brand patentee B and a potential generic challenger G. To challenge the patent, G has to pay a

fixed entry cost cg > 0. We follow Lemley and Shapiro (2005) and assume that the branded firm has a probabilistic patent. If

patent litigation occurs, G’s probability of winning the lawsuit is denoted by p, which follows a publicly known distribution

F(p) with p ∈ [0, 1]. Before G challenges, both firms know the distribution F(p) but not the value of p.

If G challenges, the firms’ strategies and payoffs vary with the permissibility of P4D. If P4D is banned, B has two options:

accommodate entry or sue for patent infringement. In the first case, G enters immediately, resulting in a duopoly. Without

loss of generality, we assume that the two firms share the market equally and their joint profits are less than the monopoly

profit, i.e., π d < 12 π m . If suing, B loses with probability p. Then, two firms compete with each other, and each earns π d . With

probability 1 − p, B wins and operates as a monopoly. Regardless of the judicial decisions, each party bears a litigation cost k.

If P4D is permitted, G can ask for a take-it-or-leave-it settlement offer of amount s.9 B then has three options: accommodate

entry, sue or accept the settlement. When B accepts s, G would in exchange stay out of the market. If B rejects s, it then

chooses between suing and accommodating entry, and the game proceeds as if P4D is forbidden at the beginning.10

j

Without any generic challenge, the payoff of G is normalized to 0 and that of B to the monopoly level. We use πn to

represent the gross profit of firm n if B takes action j, where n ∈ {B, G} and j ∈ {Sue(C), Settle(S), Accommodate Entry(AE)}. For

example, πGC represents the generic firm’s profit when the branded firm decides to sue. The generic compares the expected

profit and the entry cost when making entry decisions. Consumer surplus in the monopoly (duopoly) market is denoted as

CSm (CSd ). In line with the standard assumption, consumer surplus is higher in a duopoly market: CSd > CSm . We illustrate

the game tree in Fig. 4.

We investigate this framework under two information structures, symmetric information and asymmetric information.

Recall that before G challenges, both firms know only the distribution F(p). In the symmetric case, once G pays cg , both firms

learn the value of p. Thus, the information is complete and symmetric after G challenges. In the asymmetric information

case, only one party observes the value of p and gains an information advantage. In the main analysis, we assume that B

has the information advantage, which is in line with our argument in Section 2. In Section 6, we discuss the other case in

which G has information advantage and show that main conclusions also hold there.

We will show that information asymmetry is a key assumption to derive our main results. We also make some assumptions that simply the analysis:

9

This implies that G has full bargaining power in the negotiation. However, this is merely a simplification of the bargaining process and is not critical

to our results. In the robustness section, we will discuss another case in which B initiates the take-it-or-leave-it offer.

10

In practice, two firms can reach a settlement with a payment up to the litigation cost even if P4D is forbidden. This non-P4D settlement is not

considered in the current model, but including it would not qualitatively change our results for the following reasons. First, in a non-P4D settlement, the

generic firm will demand a payment that equals the litigation cost. This is because in our framework, the generic firm has full bargaining power, and the

brand-name firm would be willing to pay the litigation cost. Second, if the litigation cost is lower than the generic firm’s expected profit from litigation,

then the non-P4D settlement is strictly dominated by litigation. Thus, the equilibrium of the game is the same as in the main analysis. Third, even if the

non-P4D settlement is reached when P4D is banned, once P4D settlement is allowed, the equilibrium settlement would be higher than the litigation cost

and provide stronger incentives for the generic firm to enter. Thus, the main mechanism remains the same.

6

Y. Ding and X. Zhao / International Journal of Industrial Organization 67 (2019) 102532

Fig. 4. Game tree.

A1. f(p) has an increasing hazard rate, i.e.,

π m −π d

f ( p)

1−F ( p)

is increasing.

A2. 2 f (0 ) ≥ k.

A1 and A2 ensure the existence of a unique optimal settlement under asymmetric information. A1 is easily satisfied if

the probability density function f(p) is well behaved. A2 holds naturally when the litigation cost k is low compared to the

difference between the monopoly and duopoly profit.

3.1. Symmetric information

We first discuss the equilibrium when P4D is prohibited. Whether B sues or accommodates entry depends on p. If B

sues, its expected return is [ pπ d + (1 − p)π m − k]. If B accommodates entry, it has duopoly profit π d . The threshold pd that

makes B indifferent between the two options is given by the below equation.

pd π d + (1 − pd )π m − k = π d

or equival entl y

pd = 1 −

k

(1)

πm − πd

Given B’s strategy, G enters if its expected gross profit exceeds the entry cost.

πGC = [1 − F ( pd )]π d +

0

pd

( pπ d − k )dF ( p) ≥ cg

If P4D is permitted, G can initiate a settlement s as a take-it-or-leave-it offer. Since G has full bargaining power, it can

extract all surplus from not challenging. If G does not challenge, B earns a monopoly profit π m . If G challenges, the value of

the outside option for B is

Max pπ d + (1 − p)π m − k, π d

Thus, the optimal s∗ and G’s expected gross profit are given as follows.

s∗ =

p(π m − π d ) + k, if p ≤ pd

π m − π d,

if p > pd

πGS (s∗ ) = [1 − F ( pd )](π m − π d ) +

(2)

0

pd

[ p(π m − π d ) + k]dF ( p)

Proposition 1. Under symmetric information, P4D raises the generic firm’s expected profit, i.e.,πGS > πGC .11 All generic challengers

are settled with, and consumer surplus is lower with P4D than without P4D for cg < πGC and remains the same if cg ≥ πGC .

11

For convenience, we use πGS to denote the profit that is maximized at the optimal settlement amount s∗ , πGS (s∗ ).

Y. Ding and X. Zhao / International Journal of Industrial Organization 67 (2019) 102532

7

Intuitively, G can initiate a settlement as an extra option with P4D. By (2), G can obtain higher expected profit through

settlement than litigation, as settlement increases total profit and G has bargaining power. Thus, P4D raises G’s profit. Specifically, when cg ∈ [πGC , πGS ), P4D encourages generic challenges that would not otherwise be initiated without P4D. However, these challenges never translate into real competition, as they are all settled under symmetric information. When

cg ∈ [0, πGC ), consumer surplus strictly decreases, because the settlement eliminates market competition, which may occur

as a result of litigation if P4D is forbidden. For cg ∈ [πGC , +∞ ), consumer surplus remains the same, as only B operates with

or without P4D. Note that B’s profit is unaffected by P4D, since G asks for a settlement that leaves B exactly the same profit

as under litigation.

3.2. Asymmetric information

Under asymmetric information, the branded firm has an information advantage. When P4D is prohibited, since B learns

p and decides whether to sue or accommodate entry, the game is the same as that under symmetric information. If P4D

is permitted, G would not demand more than B’s loss from accommodating entry, i.e., π m − π d . As long as s ≤ π m − π d , B

never accommodates entry. If the reverse payment is less than the expected loss from litigation, or equivalently p > p(s) as

defined in Eq. (3), B agrees to settle. Otherwise, B rejects the offer and sues.

p > p( s ) =

s−k

(3)

πm − πd

Given B’s best response, G selects s to maximize its expected profit as follows.

max

s

πGS = [1 − F ( p(s ))]s +

p(s )

0

( pπ d − k )dF ( p)

Proposition 2. Under asymmetric information, the generic firm’s profit is higher when P4D is permitted. The generic firm always

demands a unique optimal s∗ ∈ (k, π m − π d ]. The branded firm settles if p ≥ p(s∗ ) ∈ (0, pd ] and litigates otherwise. Permitting

P4D increases consumer surplus and decreases the branded firm’s profit if cg ∈ (πGC , πGS ], while it decreases consumer surplus and

increases the branded firm’s profit if cg ∈ (0, πGC ]. P4D has no impact if cg ∈ (πGS , +∞ ).

Under asymmetric information, P4D raises G’s post-challenge profit and facilitates entry. However, asymmetric information leads to unreached settlements, which means that the induced challenge might become real competition and improve

consumer surplus.

With moderate entry costs, P4D may increase competition and consumer surplus by inducing generic entry. Specifically,

when cg ∈ (πGC , πGS ], G challenges only if P4D is available.12 Without P4D, the market remains a monopoly for certain; however, if P4D is permitted, there is a chance that the market shifts from monopoly to duopoly through unsettled litigations.

However, for a low entry cost, i.e., cg ∈ (0, πGC ], the expected payoff from litigation can cover the entry cost with or without

P4D. Therefore, introducing P4D is detrimental because it attracts no additional challengers but purely stifles ex post competition. When cg ∈ (πGS , +∞ ), the entry cost is high enough to prevent all generic entry. Therefore, P4D exerts no influence

on firms’ behavior or welfare.

In terms of B’s profit, note that having settlement as an additional option may be disadvantageous for B. This is essentially

a commitment issue: when P4D is banned, B can commit to suing if a generic firm challenges and p is not too high. This

threat is strong enough to prevent high-cost generic firms from challenging. However, if P4D is allowed, B has an incentive

to apply a “soft” strategy by accepting the settlement. The incumbent’s inability to commit to suing ultimately attracts more

potential competitors and endangers its monopoly position. However, if cg is low and G enters without P4D, reverse payment

induces collusion, which is strictly beneficial for B under asymmetric information.

4. Innovation incentives

In this section, we continue to consider the entry-inducing effect and further examine how P4D influences the branded

firm’s ex ante innovation incentives. In Sections 4 and 5, we primarily focus on the asymmetric information case and leave

the discussion of the symmetric information case for the end of Section 5.

Assume that there are two types of patents: high-quality (H) and low-quality (L) patents. B can obtain L at zero cost or

H for an innovation cost cb > 0.13 Suppose that H and L give rise to the same profit margin and differ only in their effect

on generic entry.14 We use the differential value of H and L to characterize the innovation incentive. In addition, we assume

For instance, if F(p) ∼ U[0, 1], π d = 1, π m = 4, and k=0.3, then G challenges if cg is between 0.235 and 0.876.

In our model, patent quality can be interpreted as patent height and/or patent breadth. Patent height places a restriction on improving the product

and patent breadth on copying the product (van Dijk, 1996). Along either dimension, a high-quality patent is less likely to be invalidated and more likely

to be infringed.

14

Here, we assume that H and L are associated with the same profit given the same market structure, which enables us to focus on the patent litigation

process. Alternatively, we could assume that H yields a higher profit and different market structures generate different profit margins. However, assuming

differential profit margins would produce the same qualitative results but require tedious discussions that depend on how firms compete with one another.

For instance, we can assume that H yields a direct profit premium for all market structures in addition to its litigation advantage. This does not affect

12

13

8

Y. Ding and X. Zhao / International Journal of Industrial Organization 67 (2019) 102532

m > C Sm and C Sd > C Sd .15 Later, we

that H yields higher consumer surplus than L given the same market structure, i.e., C SH

L

H

L

will modify this assumption and disentangle the two dimensions of a patent H: consumer surplus is greater and the patent

is legally stronger. Furthermore, we assume that fL (p) likelihood ratio dominates fH (p) since low-quality patents are easier to

attack.

f ( p)

A3. Monotone Likelihood Ratio (MLR): f L ( p) increases with p.

A3 implies the following inequalities:

FH ( p) ≥ FL ( p) and

H

f L ( p)

FL ( p)

1 − FL ( p)

≥

≥

1 − FH ( p)

f H ( p)

FH ( p)

∀p

(4)

A3 is a sufficient condition for first-order stochastic dominance but ensures more tractable comparative statics.16 The main

purpose of A3 is to guarantee that s∗L > s∗H , where s∗i is the optimal settlement if P4D is permitted and B chooses patent i.

Our analysis from now on is based on A1–A3.

We first derive B’s choice of patent quality. B would prefer H if the differential value of H and L is greater than the

innovation cost. The value of H varies with G’s optimal strategies, which in turn rely on the availability of P4D. The rest

of this section is organized as follows. First, we examine the firms’ competition strategies and payoffs in four distinctive

scenarios (with or without P4D and with H or L). Next, we study how the branded firm’s differential payoff from H and L

varies with the introduction of P4D. If the difference widens, we contend that P4D enhances innovation.

We first discuss firms’ strategies when P4D is forbidden. In this situation, G’s expected profit if the branded firm has

patent i is

πGiC = [1 − Fi ( pd )]π d +

pd

0

( pπ d − k )dFi ( p).

C > π C , which divides c into three segments.17

G’s profit is higher with L, i.e., πGL

g

GH

C , +∞ ), the entry cost is sufficiently high to block any generic challenge. By our assumption, B’s monopoly

(i) If cg ∈ (πGL

C = π C = π m . The firm has no incentive to invest in patent

profit is the same for a high- or low-quality patent: πBH

BL

quality at all.

C

C

(ii) If cg ∈ (πGH , πGL ], G enters only if B holds patent L. B’s corresponding profits are:

C

πBH

= π m,

C

πBL

= [1 − FL ( pd )]π d +

pd

[ pπ d + (1 − p)π m − k]dFL ( p).

0

C − πC .

B chooses to acquire H as long as the cost of innovation is no greater than the resulting profit increase, i.e. cb ≤ πBH

BL

C ], G always enters, and B’s profits are:

(iii) If cg ∈ (0, πGH

C

πBH

= [1 − FH ( pd )]π d +

C

πBL

= [1 − FL ( pd )]π d +

pd

0

pd

0

[ pπ d + (1 − p)π m − k]dFH ( p),

[ pπ d + (1 − p)π m − k]dFL ( p).

C ≥ π C . Although in cases (ii) and (iii), the branded firm’s expected profit associated with H is higher

By A3, we have πBH

BL

than that with L, their difference is smaller in case (iii).

Next, we investigate the branded firm’s choice of patent quality when P4D is allowed. As in the previous discussion, we

analyze how P4D changes G’s entry decision and then back out B’s innovation incentives. G’s expected profit if the branded

firm has patent i is

πGiS = (1 − Fi [ p(s∗i )] )s∗i +

p(s∗ )

i

0

( pπ d − k )dFi ( p).

Lemma 1. With P4D, the generic firm demands a higher settlement and earns higher ex post profits when patent quality is low,

S > πS .

i.e., s∗L > s∗H and πGL

GH

The intuition of Lemma 1 is straightforward. A low-quality patent is easier to be invalidated or “invented around”. This

means that through settlement, the generic challenger deserves a higher payment in exchange for abandoning the attempt.

our qualitative results. Our current model requires only reduced-form profits and has the advantage of deriving the most general results with the least

calculation burden.

15

The subscript i ∈ {H, L} is adopted to indicate the type of patent. For example, CSHm is the consumer surplus under monopoly if patent H is chosen, and

fL (p) is the probability density function of p when a type-L patent is chosen. H yields higher consumer surplus than L in duopoly regardless of the generic

product quality, because the generic product quality cannot be lower if the branded firm chooses a high-quality patent than a low-quality patent.

16

The MLR assumption is widely used in the economic literature on incomplete information, including auction and mechanism design, for instance, in

Athey (2002), Lebrun (1998) and Maskin and Riley (20 0 0).

p

17

C

C

− πGH

= 0 d [FH ( p) − FL ( p)]d p ≥ 0. The inequality is implied by A3.

Integrating by parts, we have πGL

Y. Ding and X. Zhao / International Journal of Industrial Organization 67 (2019) 102532

9

Fig. 5. Innovation incentive: with and without P4D.

In addition, the generic challenger enjoys a better litigation position. Both channels contribute to a higher expected generic

firm profit when patent quality is low.

The two cut-off profits again divide cg into 3 segments, as in the case in which P4D is banned.

S , +∞ ), G never enters, which implies that B earns the monopoly profit regardless and has no incentive to

(i’) If cg ∈ (πGL

innovate.

S , π S ], G enters only if it encounters a low-quality patent. B’s profits with H and L are:

(ii’) If cg ∈ (πGH

GL

S

πBH

= πm

S

πBL

= (π m − s∗L )(1 − FL [ p(s∗L )] ) +

p(s∗ )

L

0

[ pπ d + (1 − p)π m − k]dFL ( p)

Patent H is obviously more valuable, as it secures the monopoly position for B.

S ], G always enters. The corresponding profits of B are:

(iii’) If cg ∈ (0, πGH

p(s∗ )

H

S

πBH

= (π m − s∗H )(1 − FH [ p(s∗H )] ) +

S

πBL

= (π m − s∗L )(1 − FL [ p(s∗L )] ) +

0

0

p(s∗L )

[ pπ d + (1 − p)π m − k]dFH ( p)

[ pπ d + (1 − p)π m − k]dFL ( p)

Patent H is more profitable for two reasons. First, it grants B a higher probability of winning the lawsuit. Second, it

forces G to ask for a lower s in the settlement.

S ], the branded firm earns a higher profit with a high-quality patent than with a low-quality patent

Lemma 2. If cg ∈ (0, πGH

S > πS .

when P4D is permitted, i.e. πBH

BL

Thus far, we have derived the branded firm’s profits for a high- and a low-quality patent, respectively. Our next task is

to study how the innovation incentive is affected by allowing P4D. Fig. 5 depicts the incentive with and without P4D, which

depends on the entry cost. The red (blue) line indicates the premium of patent H with (without) P4D. We can compare

the branded firm’s incentive to innovate from the heights of the lines. B is more (less) willing to innovate with P4D if the

red line lies above (below) the blue line or when the entry cost is relatively high (low).18 Proposition 3 summarizes the

relationship between P4D and innovation and how it varies with the entry cost.

C , π S ] ). P4D decreases innovation

Proposition 3. P4D increases the innovation incentive for intermediate entry costs (cg ∈ (πGL

GL

C , π C ]. For a low entry cost c ∈ (0, π C ], P4D deters innovation if and only if

incentives as the entry cost falls to cg ∈ (πGH

g

GL

GH

p

pd

S ), P4D has no effect.

[1 − FH ( p)]dp ≤ p(ds∗ ) [1 − FL ( p)]dp. When the entry cost is too high (cg > πGL

p(s∗ )

H

L

The intuition is as follows. For an intermediate entry cost, P4D stimulates innovation by raising the value of patent H

relative to L. Without P4D, the branded firm has no incentive to attain H since L is strong enough to deter entry. However, if

P4D is permitted, G will challenge L for certain but may or may not challenge H. Depending on whether G challenges H, we

C , π S ] into (π C , π S ] and (π S , π S ].19 In the first case, G challenges and H promises B a better

divide the range cg ∈ (πGL

GL

GL

GH

GH

GL

18

C

], the blue line is above the red line if and only if

For cg ∈ (0, πGH

The sign of π

Appendix B.

19

S

GH

−π

C

GL

pd

p(s∗H )

[1 − FH ( p)]d p ≤

pd

p(s∗L )

[1 − FL ( p)]d p. We discuss this condition in detail later.

S

C

S

C

is undetermined without further assumptions. Here, we assume πGH

> πGL

and defer the discussion with πGH

≤ πGL

to

10

Y. Ding and X. Zhao / International Journal of Industrial Organization 67 (2019) 102532

Fig. 6. The effect of P4D on consumer surplus.

position in the patent infringement lawsuit. In the second case, G does not challenge, and H can foreclose generic entry and

completely avoid the potential loss from litigation. Thus, P4D provides an even stronger incentive to innovate in the second

case, as shown in Fig. 5.

C , π C ], in contrast, P4D discourages innovation. H can deter entry if P4D is forbidden but loses this ability

When cg ∈ (πGH

GL

once P4D is allowed. It is equivalent to say that the value of H decreases as P4D becomes available. Meanwhile, the profit

associated with L is unaffected by P4D. Hence, B’s innovation incentive is reduced by P4D. Most previous literature finds

that P4D will boost the branded firm’s innovation, as it extends the effective patent life. However, we find that the opposite

result might hold when the entry cost is low, since P4D devalues a high-quality patent.

C ], P4D decreases the innovation incentive if pd [1 − F ( p)]dp ≤ pd [1 − F ( p)]dp. The impact of P4D

When cg ∈ (0, πGH

H

L

p(s∗ )

p(s∗ )

H

L

S − π S ) − (π C − π C ), which can also be interpreted as the comparison of the incremenon the innovation incentive is (πBH

BL

BH

BL

S − π C ) − (π S − π C ). In our model, the incremental value of

tal value of settlement for the two types of patents, i.e., (πBH

BH

BL

BL

settlement is positive for both H and L because B has private information on p, but which one is higher depends on the

pd

pd

specific distributions of p. If p(s∗ ) [1 − FH ( p)]dp ≤ p(s∗ ) [1 − FL ( p)]dp, the information rent of H is smaller than that of L,

H

L

which implies that B has a lower innovation incentive if P4D is allowed.

5. Welfare analysis with ex ante innovation

In this section, we investigate the overall impact of P4D on consumer surplus, combining ex post competition and ex ante

innovation. On the one hand, when the entry cost is relatively high, P4D benefits consumers by raising both competition and

innovation. On the other hand, if the entry cost is low, P4D decreases consumer surplus, as both competition and innovation

decline. Proposition 4 and Fig. 6(a) provide a complete description of the findings.

C , π S ) and decreases consumer surplus if

Proposition 4. P4D increases consumer surplus if a generic firm’s entry cost cg ∈ (πGL

GL

pd

pd

C

C

C

cg ∈ (0, πGH ] and p(s∗ ) [1 − FH ( p)]dp ≤ p(s∗ ) [1 − FL ( p)]dp. For cg ∈ (πGH , πGL ], the result is mixed. When the entry cost is too

H

S ), P4D has no effect.

high (cg > πGL

L

In previous sections, we have shown that consumer surplus increases if either ex post competition is intensified or

C , π S ], P4D improves consumer surplus partially because it

the branded firm obtains a higher quality patent. If cg ∈ (πGL

GL

induces generic entry and raises ex post competition and partially because the induced entry cultivates ex ante innoC ], the entry cost is too low to prevent any generic entry, suggesting no new challengers generated

vation. If cg ∈ (0, πGH

by P4D. Therefore, P4D purely reduces competition from existing challengers and jeopardizes consumer surplus. Moreover,

Proposition 3 suggests that P4D also discourages innovation and further introduces inefficiency in this range.20

C , π C ], the result is mixed and depends on the cost of innovation, c . If the innovation cost is

When cg falls within (πGH

b

GL

S − π S ), P4D improves consumer surplus because it induces generic challenges. However, for a high innovation

low (cb < πBH

BL

20

If

pd

p(s∗H )

[1 − FH ( p)]d p ≤

pd

p(s∗L )

[1 − FL ( p)]d p does not hold, P4D decreases consumer surplus with a sufficiently high or low innovation cost. However, the

C

C

S

S

− πBL

, πBH

− πBL

].

welfare implication of P4D is indeterminate without further assumptions when the innovation cost cb ∈ (πBH

Y. Ding and X. Zhao / International Journal of Industrial Organization 67 (2019) 102532

11

C − π C ), the branded firm never innovates and P4D cannot induce entry, which implies consumer surplus decost (cb > πBH

BL

creases with the permission of P4D. Finally, for intermediate innovation costs, the effect is ambiguous, as we are comparing

the welfare of a monopoly market with high-quality patents and a duopoly market with low-quality patents.

Proposition 4 illustrates the specific range in which P4D improves or deteriorates consumer surplus, which depends on

the entry cost. Next, we analyze how the critical thresholds of the entry cost are influenced by important market indicators

such as the monopoly and the duopoly profit. Our findings are summarized in Corollary 1.

S −π C )

∂ (πGL

GL

> 0,

∂π m

S −π C )

C

∂ (πGL

∂π

m

d

GL

< 0 ). The range in which P4D may deteriorate consumer surplus decreases with π and increases with π ( ∂πGL

m < 0,

∂π d

C

∂πGL

> 0 ).

∂π d

Corollary 1. The range in which P4D promotes consumer surplus increases with π m and decreases with π d (

Corollary 1 implies that P4D is more likely to enhance consumer surplus when the duopoly profit π d is low and the

monopoly profit π m is high.21 The intuition is straightforward. If π d is low, the expected profit of G may not be high

enough, and P4D is needed to induce generic entry. If π m is high, B is more aggressive in litigation, which reduces G’s profit

without P4D. Meanwhile, B is willing to accept a higher settlement to avoid the threat of losing its monopoly position,

which increases G’s profit with P4D. In contrast, with high π d and low π m , G has sufficient incentives to challenge without

P4D, and the gain from settlement is small. This finding may shed light on the antitrust judgment of P4D. If the ex post

competition is not severe and the generic firm’s duopoly profit is relatively large, P4D is more likely to be detrimental.

However, if the targeted branded firm earns a substantial monopoly profit and the ex post competition is intensive, the

antitrust division may need to consider the positive effect of P4D.

At the end of this section, we simply present the impact of P4D under symmetric information and compare it with the

results under asymmetric information. B’s innovation incentive under complete information is similar to that in Fig. 5. The

overall welfare effect is depicted in Fig. 6(b). Compared to Fig. 6(a), the area in which P4D benefits consumer surplus shrinks

since P4D no longer increases ex post competition. Therefore, the only reason that consumer surplus rises with P4D is that

B pursues patent H to preempt generic challenges, which occurs when the entry cost is moderate and the innovation cost

C ], P4D reduces consumer surplus for certain, as both innovation and competition decrease.

is low. When cg ∈ (0, πGL

6. Robustness and extension

In the discussion above, we have shown that when the generic firm demands a take-it-or-leave-it offer under asymmetric

information, P4D may increase ex post competition and has a heterogeneous effect on ex ante innovation because generic

entry is endogenous. In this section, we show that our main results remain valid after relaxing some assumptions. In particular, we first extend the single generic entry model to a multiple-entry framework. It can be shown that with multiple

entrants, similar results are obtained even with perfect information. Then, we study the case in which the branded firm

initiates the settlement offer, which is a robustness check of the bargaining process in the benchmark model. Finally, we

discuss the model with different assumptions on patent quality and demonstrate the welfare effect of P4D.

6.1. Multiple entrants

In reality, there is usually more than one potential generic firm targeting the branded drug. Thus, we extend the twoplayer model to a multiple-entry framework. There are two potential entrants, G1 and G2 , with identical entry cost cg that

may challenge B sequentially. As in the benchmark model with symmetric information, the challenger draws p, which is

observed by both parties, from F(p) once it pays the fixed cost. The realization of p is independent between the two generic

firms. If B chooses to sue a generic firm, then the court’s decision is binding for both generic firms, which means that both

G1 and G2 enter (stay out) if B loses (wins) in one of the litigations against G1 or G2 .22 In line with the benchmark model,

if the patent is invalid, all three firms earn equal triopoly profits π t , and π m > 2π d > 3π t . In addition, it is assumed that the

litigation cost k = 0 in this extension.23 Given this simplification, B never chooses to accommodate entry.

Proposition 5. If π m − 2π t > (π m − π d )E ( p), there exists p∗ such that B settles with G1 if and only if p ≥ p∗ . Allowing P4D

raises G1 ’s expected profit and facilitates entry. In addition, G2 must challenge if G1 chooses to do so.24

21

Corollary 1 also suggests some testable implications. One possible test is to simulate the effect of P4D on consumer surplus and assess whether there

is (1) a positive relationship between the effect and the monopoly profit and (2) a negative relationship between consumer surplus and duopoly profit.

Another possible test is that conditioning on other factors, the expected return from a challenge increases with the duopoly profit and decreases with the

monopoly profit.

22

The litigation can be interpreted as whether the original patent is valid. If the court supports B, then the patent is valid, and other generic firms will

not challenge again.

23

This assumption guarantees that G’s gross profit is always positive when p is close to zero. The qualitative results hold even if we remove this simplification.

24

As long as P4D may facilitate generic entry, the impact of P4D on innovation incentives and consumer surplus would be similar to that in the main

framework. Therefore, we skip the discussion in Section 6 if not necessary.

12

Y. Ding and X. Zhao / International Journal of Industrial Organization 67 (2019) 102532

Fig. 7. Two patents yield the same consumer surplus.

This proposition suggests that our main results for P4D can hold through a slightly different mechanism. While in the

main analysis, it is the asymmetric information that prevents the firms from reaching a settlement, in the case of multiple

entrants, it is the settlement externality. G2 imposes a settlement externality on B and G1 . B anticipates a large settlement

demand from G2 if it reaches a P4D with G1 . This settlement shrinks the mutual benefit zone of bargaining between B and

G1 and may break down the negotiation even with perfect information. Therefore, it is possible that ex post competition is

enhanced with P4D.25

6.2. Alternative bargaining process

In contrast to the benchmark framework, the assumption here is that once G enters, B can initiate a take-it-or-leave-it

offer s. If G accepts the offer, it will give up the challenge. Otherwise, B will sue G. In addition, we assume G is the party that

knows the true value of p after it pays cg . The reason that we switch the information advantage is to simplify the model,

because the settlement offer becomes a signal of p if B has an advantage.26 To ensure that there is a unique solution, we

assume that p follows a uniform distribution from [0,1].

In this reversed bargaining process, we anticipate similar results to those in the benchmark model. First, with P4D, the

generic firm has an additional option of accepting s, which is beneficial when G draws a low p. Thus, the information

advantage raises the generic firm’s expected profit when P4D is permitted. Moreover, a strong generic firm rejects the

settlement, as the optimal s is based on the distribution F(p). Hence, P4D does not eliminate all challenges. The following

proposition summarizes these findings.

m

d

Proposition 6. When the branded firm initiates the settlement s, if 3π d > π m , there exists a s∗ = π d −π m such that the generic

firm settles if p ≤

s∗ +k

πd

3π −π

and litigates otherwise. The generic firm’s profit rises if P4D is permitted.

6.3. Patent quality

In the main model, we assume that patent H is both profit-enhancing for the branded firm and socially desirable for

consumers. In reality, these two dimensions may not be perfectly correlated. For instance, the branded firm may adopt the

ever-greening patent strategy by acquiring supplementary patents that are not welfare-enhancing. It is also possible that

some patents yield better health outcomes but do not provide legal advantages for the branded firm. Next, we remove

the original assumption regarding patent H and study two alternative scenarios. In the first, patent H only makes B legally

stronger but does not increase consumer surplus. In the second, patent H raises consumer surplus but is not beneficial for

B. Intuitively, compared to the previous results, the welfare-enhancing range of P4D is likely to shrink in both scenarios, as

P4D may improve innovation and competition when patent H has both advantages.

The first scenario is captured by Fig. 7. There are two major differences compared to Fig. 6(a), as patent H does not

S , π S ] and c ∈ (0, π S − π S ], allowing P4D does not increase welfare, since B innovates to

improve welfare. When cg ∈ (πGH

b

GL

BH

BL

25

Note that without P4D, G2 does not challenge if G1 stays out. Therefore, if P4D can induces G1 ’s entry, it also weakly increases G2 ’s challenge.

Now, the generic firm’s rejection becomes a signal of p. Therefore, we assume that B never accommodates entry to rule out the signaling issue in this

extension. If B can choose to accommodate entry, there would be a cap on s1 , such that B always litigates if a s1 higher than this upper bound is rejected,

which should yield a similar qualitative result.

26

Y. Ding and X. Zhao / International Journal of Industrial Organization 67 (2019) 102532

13

C , π C ] and c ∈ (π S − π S , π C − π C ], permitting

foreclose G’s challenge and sustain its monopoly position. When cg ∈ (πGH

b

GL

BH

BL

BH

BL

P4D strictly deteriorates welfare, compared to an undetermined impact in Fig. 6(a). This is because P4D dampens ex post

competition in this area.

The second scenario is straightforward, as the branded firm has no incentive to innovate. Hence, the impact of P4D on

welfare is the same as that described in Proposition 2.

7. Discussion

In the model, we endogenize generic entry and systematically analyze the effects of P4D on competition and innovation. We have three main findings. First, P4D has the potential to increase competition and benefit consumers even without

considering ex ante innovation. Second, permitting settlement has heterogeneous effect on a branded firm’s innovation incentive, depending on the generic firm’s entry cost and the branded firm’s innovation cost. Finally, the standard conflict

between competition and innovation may be reconciled, as under certain conditions, P4D increases both ex post competition and ex ante innovation. Promoting competition and innovation are often thought to be contradictory because enhanced competition automatically leads to decreased profit associated with the brand’s patent (Higgins and Graham, 2009;

Grabowski and Kyle, 2007; Branstetter et al., 2014; Hemphill and Sampat, 2012). However, as shown in the model, profit

would decrease even more if the branded firm chooses not to innovate. As a result, P4D may promote innovation even if it

stimulates competition.

The findings in this paper also have some policy implications. The first relates to the optimal ruling of the settlement

with reverse payment. Categorical illegality, categorical legality, or a simple comparison between the reverse payment and

the litigation cost is insufficient. A more appropriate antitrust judgment should be case-by-case and account for the generic

firm’s entry cost, the profitability, the distribution of patent strength, and sometimes the innovation cost. Sources of these

estimates include the filings by the involved pharmaceutical firms and historical statistics from the industry. Of course,

accurately measuring these variables is difficult. The model at least provides guidance to detect the conditional under which

P4Ds are most likely to increase or decrease consumer surplus.

The second implication pertains to the necessity of inducing generic entry. In this paper, we focus on the market for

small-molecule drugs, but the findings can be applied to biologics. Similar to the Hatch–Waxman Act of 1984, the Biologics

Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) was signed into law in 2010 to balance innovation and accessibility (Lu, 2014).

As the innovation cost is significantly higher for the follow-on biologics (FTC, 2009), we believe that facilitating entry is even

more important for biologics, and using P4D to induce entry might be necessary.

Finally, we discuss using P4D and 180-day exclusivity to subsidize the generic firm and induce entry. As a “one size fits

all” policy, 180-day exclusivity may overprotect generic firms with low entry costs or fail to provide sufficient incentives for

drugs with high entry costs. On the other hand, P4D is more flexible, as the ruling can be adjusted case-by-case. In cases

in which P4D improves welfare, policy makers may be more tolerant. While in other cases, policy makers would rather

prohibit P4D and consider using other measures, including market exclusivity, to attract generic entry.

Our model has limitations and can be extended in several ways. First, we simplified the bargaining process to derive our

main results. It would be interesting to extend the model by adopting a more realistic bargaining framework that allows signaling in the settlement. Second, to investigate the role of sequential entry, we assume the presence of two generic entrants

under perfect information. It would be interesting to further explore the case with N entrants and imperfect information,

where information externality among generic firms might emerge.

Appendix A

Proof of Proposition 2. We prove results regarding the impact of P4D on G’s and B’s profit and leave the discussion of

welfare impact in the main article.

First, for G’s profit, since there is a one-to-one mapping from s to p(s), we can instead maximize πGS by targeting a proper

threshold p∗ . The first-order condition yields

(π m − 2π d ) p∗ + 2k =

1 − F ( p∗ ) m

( π − π d ).

f ( p∗ )

By A1, there is at most one solution of this equation, which ensures uniqueness. From A2, the optimal p∗ > 0, and thus,

there must be an interior solution. Clearly, if p∗ = 1, the left-hand side is greater than the right-hand side. If the solution is

higher than pd , p∗ = pd because the upper bound of s is π m − π d .

We then list G’s expected payoff with and without P4D and sign their difference.

14

Y. Ding and X. Zhao / International Journal of Industrial Organization 67 (2019) 102532

πGS = [1 − F ( p∗ )]s∗ +

p∗

0

πGC = [1 − F ( pd )]π d +

( pπ d − k )dF ( p)

pd

0

( pπ d − k )dF ( p)

If G demands s = π m − π d (makes p(s ) = pd ), πGS > πGC . In equilibrium, G may demand a different s∗ , which must give G a

higher expected profit by the definition of s∗ . Therefore, P4D raises the generic firm’s profit.

We address B’s profit change in three segments.

(a) cg ∈ (0, πGC ]

According to the previous discussion, G always enters. B’s profits associated with litigation and settlement are πBC and

S

πB , respectively.

πBC = [1 − F ( pd )]π d +

pd

0

[ pπ d + (1 − p)π m − k]dF ( p)

πBS = [1 − F ( p∗ )](π m − s∗ ) +

p∗

0

[ pπ d + (1 − p)π m − k]dF ( p)

πBS − πBC = [1 − F ( pd )](π m − π d − s∗ ) + [F ( pd ) − F ( p∗ )](π m − s∗ )

−

≥

pd

p∗

pd

p∗

[ pπ d + (1 − p)π m − k]dF ( p)

[(π m − s∗ ) − ( pπ d + (1 − p)π m − k )]dF ( p)

≥0

The first inequality is because s∗ ≤ π m − π d . The second is inferred by the definition of s∗ .

(b) cg ∈ (πGC , πGS ]

Without P4D, G does not enter, and B enjoys the monopoly profit π m . With P4D, B’s corresponding profit πBS is clearly

less than π m .

(c) cg ∈ (πGS , +∞ )

With or without P4D, no generic firm enters, and B earns monopoly profit. Proof of Lemma 1. By the first-order condition in Proposition 2, we have

(π m − 2π d ) p∗i + 2k =

1 − Fi ( p∗i ) m

(π − π d ), i ∈ {H, L}.

fi ( p∗i )

The LHS of this equation is strictly increasing with p, while the RHS is decreasing with p by A1. Eq. (4) implies

1−FH ( p)

.

f H ( p)

Therefore,

p(s∗L )

≥

p(s∗H )

and

By the definition of s∗L , it must be

S

πGL

(s∗H ) = s∗H (1 − FL [ p(s∗H )] ) +

s∗L

≥ s∗H .

S ( s∗ )

that πGL

L

p(s∗ )

H

0

1−FL ( p)

f L ( p)

≥

S (s∗ ), where

≥ πGL

H

( pπ d − k )dFL ( p).

S (s∗ ) > π S (s∗ ), as

Moreover, given the same settlement, G’s profit is higher from challenging patent L, i.e., πGL

H

GH H

S

S

πGL

(s∗H ) − πGH

(s∗H ) = s∗H (FH [ p(s∗H )] − FL [ p(s∗H )] ) +

=

p(s∗ )

H

0

p(s∗ )

H

0

( pπ d − k )[ fL ( p) − fH ( p)]dp

( pπ d − k − s∗H )[ fL ( p) − fH ( p)]dp

= (FH [ p(s∗H )] − FL [ p(s∗H )] )(s∗H − p(s∗H )π d + k ) + π d

p(s∗ )

H

0

[FH ( p) − FL ( p)]dp > 0.

S ( s∗ ) > π S ( s∗ ).

The last inequality follows from the definition of p(s∗H ) and the fact that FH (p) ≥ FL (p). Therefore, πGL

L

GH H

Proof of Lemma 2. First, we show that if G demands s∗L rather than s∗H when challenging patent H’s owner, B would be

better off since s∗L ≥ s∗H .

S

S

πBH

(s∗H ) − πBH

(s∗L ) = (π m − s∗L )[FH ( p(s∗L )) − FH ( p(s∗H ))] + (s∗L − s∗H )[1 − FH ( p(s∗H ))]

−

p(s∗ )

L

p(s∗H )

[ pπ d + (1 − p)π m − k]dFH ( p)

Y. Ding and X. Zhao / International Journal of Industrial Organization 67 (2019) 102532

15

≥ (π m − s∗L )[FH ( p(s∗L )) − FH ( p(s∗H ))] + (s∗L − s∗H )[1 − FH ( p(s∗H ))]

− (π m − s∗H )[FH ( p(s∗L )) − FH ( p(s∗H ))]

= (s∗L − s∗H )[1 − FH ( p(s∗L ))] > 0

Then, we prove that if G fixes its demand s∗L , B earns a higher profit with patent H than with patent L.

S

S

πBH

(s∗L ) − πBL

(s∗L ) = (π m − s∗L )[FL ( p(s∗L )) − FH ( p(s∗L ))] +

= (π m − π d )

p(s∗ )

L

0

Proof of Proposition 3. For cg >

C ].

on the case in which cg ∈ (0, πGH

0

the proof is straightforward and is discussed in the main article. In this part, we focus

S

C

πBH

− πBH

= (π m − s∗H )[1 − FH ( p(s∗H ))] − [1 − FH ( pd )]π d −

= (π m − π d )[1 −

pd

p(s∗H )

pd

p(s∗H )

pd

p(s∗H )

[ pπ d + (1 − p)π m − k]dFH ( p)

FH ( p)dp] − s∗H

= (π m − π d )[(1 − p(s∗H )) −

= (π m − π d )

[ pπ d + (1 − p)π m − k][ fH ( p) − fL ( p)]dp

[FH ( p) − FL ( p)]dp ≥ 0

S − π S > 0.

Combining these two inequalities, we have πBH

BL

C ,

πGH

p(s∗ )

L

pd

p(s∗H )

FH ( p)dp − (1 − pd )]

[1 − FH ( p)]dp

Similarly,

S

C

πBL

− πBL

= (π m − π d )

pd

p(s∗L )

[1 − FL ( p)]dp

S − π C ≤ π S − π C iff

Therefore, πBH

BH

BL

BL

pd

p(s∗H )

[1 − FH ( p)]dp ≤

Proof of Corollary 1. First, we prove that

pd

p(s∗L )

[1 − FL ( p)]dp.

C

∂πGL

∂π C

> 0 and ∂πGL

m < 0.

∂π d

pd

C

∂πGL

∂ pd

= [1 − FL ( pd )] +

p fL ( p)dp + fL ( pd )[( pd − 1 )π d − k]

d

∂π

∂π d

0

Since

∂ pd

= − m k d 2 < 0 and

∂π d

(π −π )

( pd − 1 )π d − k < 0, we have

C

∂πGL

> 0.

∂π d

C

∂πGL

∂ pd

= fL ( pd )[( pd − 1 )π d − k]

∂π m

∂π m

∂π C

∂p

d

Since ∂π m

= m k d 2 > 0, we have ∂πGL

m < 0.

(π −π )

Next, we show that

S −π C )

S −π C )

∂ (πGL

∂ (πGL

GL

GL

> 0 and

< 0.

∂π m

∂π d

S

C

S

C

∂ (πGL

− πGL

) ∂πGL

∂πGL

=

−

∂π m

∂π m ∂π m

S is a function of both p(s∗ ) and π m , by the Envelope Theorem,

Since πGL

L

S

S

S

∂πGL

( p(s∗L ); π m ) ∂πGL

( p(s∗L ); π m ) ∂ p(s∗L ) ∂πGL

( p(s∗L ); π m )

=

+

∂π m

∂ p(s∗L )

∂π m

∂π m

∗

∗

= 0 + p(sL )[1 − FL ( p(sL ))] > 0

∂π C

∂ (π S −π C )

GL

GL

Combining this with ∂πGL

> 0.

m < 0, we have

∂π m

Similarly, by applying the Envelope Theorem, it can be derived that

pd

S

C

∂ (πGL

− πGL

)

∂ pd

∗

∗

d

=

−

p

(

s

)

[1

−

F

(

p

(

s

))

]

−

[1

−

F

(

p

)

]

−

f

(

p

)

[

(

p

−

1

)

π

−

k

]

−

pdFL ( p) < 0

L

L

L

d

d

d

L

L

∂π d

∂π d

p(s∗L )

16

Y. Ding and X. Zhao / International Journal of Industrial Organization 67 (2019) 102532

Proof of Proposition 5. When P4D is forbidden, G1 challenges if its expected profit exceeds cg ,

πGC1 =

0

1

pπ t dF ( p) > cg .

If G1 wins, G2 pays cg and enters the market. Otherwise, if G1 loses or decides not to challenge, G2 will stay out of the

market given that G1 and G2 ’s challenge decisions are symmetric. If G1 challenges, B’s ex post profit is

πBC = (1 − p)π m + pπ t .

If P4D is permitted, we solve the game by backward induction. If G1 does not challenge, there is no ex post competition

since G2 either reaches a P4D settlement with B or gives up challenging. If G1 challenges and B litigates, G2 ’s choice is the

same as above. When B and G1 reach a settlement s1 , which is a sunk cost for B when it faces G2 ’s challenge, the optimal

settlement s∗2 is

s∗2 = p(π m − π d ),

and G2 challenges if

πGS2 = E (s∗2 ) =

1

0

p(π m − π d )dF ( p) > cg .

We continue to analyze the game between B and G1 . At this point, we assume that G2 must challenge if G1 challenges,

which will be proved later. B’s profit is given as follows.

πB =

m

π − s1 − E (s∗2 ), if settled with G1

(1 − p)π m + pπ t , if sue

The maximum settlement s∗1 that B is willing to accept is

s∗1 = p(π m − π t ) − E (s∗2 ).

s∗1 also represents the maximum that G1 can obtain from P4D. In equilibrium, if G1 earns a higher profit from litigation

(e.g., πGC1 = pπ t > s∗1 ), P4D cannot be reached.

We then prove there is a unique p∗ such that s∗1 ≥ πGC1 iff p ≥ p∗ . Both s∗1 and πGC1 are linear functions of p. The slope of

s∗1 ( p) is π m − π t , while the slope of πGC1 ( p) is π t . Thus, s∗1 ( p) increases faster with p. Since s∗1 (0 ) = −E (s∗2 ) < 0 = πGC1 (0 ),

our argument holds as long as s∗1 (1 ) > πGC1 (1 ), which requires π m − 2π t > (π m − π d )E ( p). Given that s∗1 ≥ πGC1 for p ≥ p∗ ,

P4D raises expected profit for G1 .

Finally, we illustrate that G2 has a greater incentive to challenge than does G1 . The main reason is that G2 can obtain a

higher expected settlement than G1 .

E (πGS2 ) = E (s∗2 ) =

E (πGS1 ) =

E (πGS2 ) − E (πGS1 ) =

p∗

0

−

1

0

p(π m − π d )dF ( p)

pπ t dF ( p) +

0

1

1

p∗

[ p(π m − π t ) − E (s∗2 )]dF ( p)

p(π m − π d )dF ( p) −

p∗

0

0

1

[ p(π m − π t ) − E (s∗2 )]dF ( p)

[ pπ t − p(π m − π t ) + E (s∗2 )]dF ( p)

= ( π m − 2π d + π t )E ( p ) − ( π m − 2π t )

−π

Since s∗1 ( p∗ ) = πGC1 ( p∗ ), we have p∗ = ππm −2

E ( p). Thus,

πt

m

E (πGS2 ) − E (πGS1 ) = (π m − 2π t )[

As

p∗

0

( p∗ − p)dF ( p)

d

π m − 2π d + π t ∗

p −

πm − πd

0

p∗

( p∗ − p)dF ( p)]

∂ 2 [E (πGS2 )−E (πGS1 )]

= − f ( p∗ ) < 0, the profit difference is a concave function of p∗ . Hence, the minimizer of this difference

∂ ( p∗ )2

is either p∗ = 0 or p∗ = 1. At both points, the profit difference is 0, which means that E (πGS2 ) > E (πGS1 ) and G2 always

challenges given that G1 challenges. Proof of Proposition 6. The generic firm accepts the settlement iff p ≤ p (s ) = s+dk . Therefore, B’s expected profit can be

π

expressed as follows.

πBS = (π m − s )F [ p (s )] +

1

p (s )

[ pπ d + (1 − p)π m − k]dF ( p)

m

d

The first-order condition indicates that s∗ = π d −π m and p (s∗ ) =

ment increases G’s profit when p ≤ p

(s∗ ),

3π −π

2k

.

3π d −π m

Clearly, G’s expected profit is higher, since settle-

while G’s profit remains the same when p > p (s∗ ).

Y. Ding and X. Zhao / International Journal of Industrial Organization 67 (2019) 102532

17

S

C

Fig. 8. The effect of P4D on consumer surplus: when πGH

≤ πGL

.

Appendix B

S ≤ π C . Despite the slight differences from Fig. 6(a) in the main

Fig. 8 illustrates the welfare effects of P4D when πGH

GL

analysis, Fig. 8 reveals a general pattern that is similar and intuitive.

S ] and c ≥ π C , the analysis is the same as in the main model.

(i) For cg ∈ (0, πGH

g

GL

S , π C ], for the low innovation cost area (c ∈ (0, π S − π S ]), welfare is unaffected by P4D because the

(ii) If cg ∈ (πGH

b

GL

BH

BL

branded firm always chooses a high-quality patent that forecloses the generic firm with or without settlement. For

a moderate innovation cost, B innovates and forecloses entry with P4D, whereas it does not innovate and G enters

without P4D. Hence, the influence on consumer surplus is ambiguous, as we are trading-off product quality and

market competition. For a high innovation cost, P4D does not increase innovation or induce entry, which decreases

welfare.

C ] and pd [1 − F ( p)]dp > pd [1 − F ( p)]dp, as in the main analysis, the welfare implication is also amIf cg ∈ (0, πGH

H

L

p(s∗ )

p(s∗ )

H

biguous for a moderate innovation cost.

L

References

Athey, S., 2002. Monotone comparative statics under uncertainty. Q. J. Econ. 117 (1), 187–223.

Bebchuk, L.A., 1984. Litigation and settlement under imperfect information. RAND J. Econ. 15 (3), 404–415.

Berndt, E.R., Mortimer, R., Bhattacharjya, A., Parece, A., Tuttle, E., 2007. Authorized generic drugs, price competition, and consumers welfare. Health Affairs

26 (3), 790–799.

Böhme, E., Frank, J.S., Kerber, W., 2017. Optimal incentives for patent challenges in the pharmaceutical industry. Working Paper. MAGKS Joint Discussion

Paper Series in Economics.

Bokhari, F.A., Mariuzzo, F., Polanski, A., 2017. Entry limiting agreements for pharmaceuticals: pay-for-delay and authorized generic deals. Working Paper.

Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2626508.

Branstetter, L., Chatterjee, C., Higgins, M.J., 2014. Starving (or fattening) the golden goose? Generic entry and the incentives for early-stage pharmaceutical

innovation. NBER Working Paper No. 20532. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Dickey, B.M., Rubinfeld, D.L., 2012. Would the per se illegal treatment of reverse payment settlements inhibit generic drug investment? J. Compet. Law

Econ. 8 (3), 615–625.

Drake, K.M., Starr, M.A., McGuire, T., 2014. Do “Reverse Payment” settlements of brand-generic patent disputes in the pharmaceutical industry constitute an

anticompetitive pay for delay? NBER Working Paper No.20292. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Edlin, A., Hemphill, S., Hovenkamp, H., Shapiro, C., 2015. The actavis inference: Theory and practice. Rutgers Univ. Law Rev. 67, 585.

Edlin, A.S., Hemphill, C.S., Hovenkamp, H.J., Shapiro, C., 2013. Activating Actavis. Antitrust Magazine. Fall.

Elhauge, E., Krueger, A., 2012. Solving the patent settlement puzzle. Tex. Law Rev. 91, 283.

FTC, 2009. Emerging health care issues: Follow-on biologic drug competition: a federal trade commission report. Commission Report. https:

//www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/emerging- health- care- issues- follow- biologic- drug- competition- federal- trade- commission- report/

p083901biologicsreport.pdf.

FTC, 2010. An FTC Staff Study, January 2010, https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/pay-delay- how- drug- company- pay- offs- costconsumers- billions- federal- trade- commission- staff- study/100112payfordelayrpt.pdf.

FTC, 2015. Overview of agreements filed in FY 2015 a report by the bureau of competition. https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/

agreements- filed- federal- trade- commission- under- medicare- prescription- drug- improvement- modernization/overview_of_fy_2015_mma_agreements_

0.pdf.

Grabowski, H., Long, G., Mortimer, R., 2014. Recent trends in brand-name and generic drug competition. J. Med. Econ. 17 (3), 207–214.