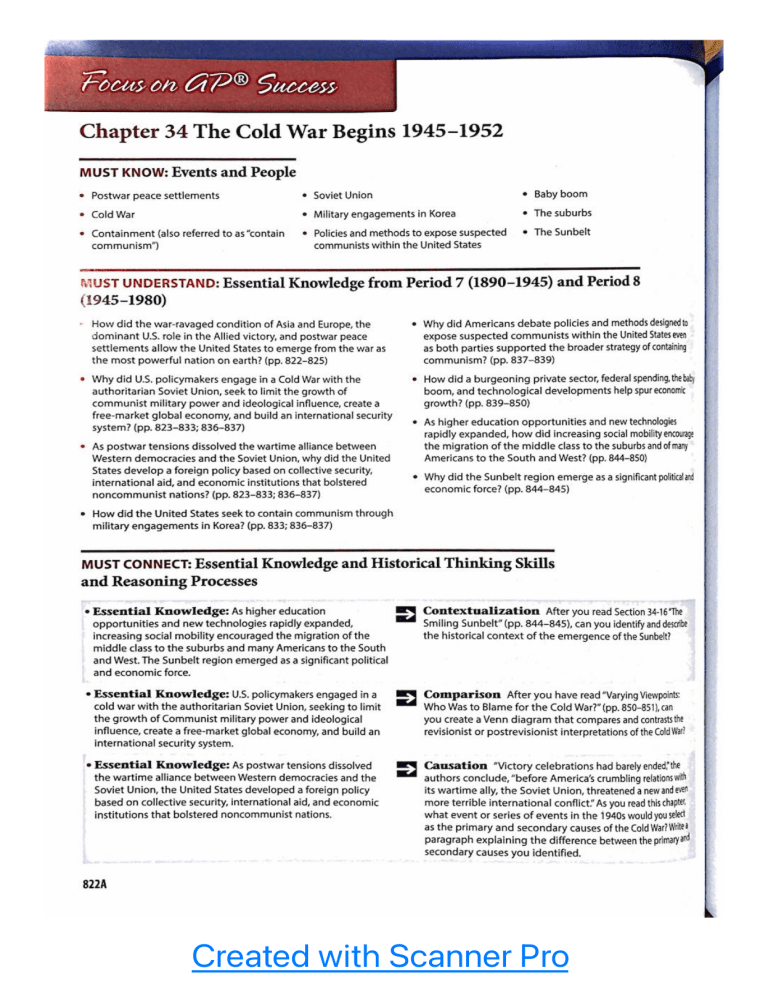

Focuson ap Success Chapter 34 The Cold War Begins 1945-1952 MUST KNOW: Events and People • Postwar peace settlements Soviet Union • Baby boom • Cold War Military engagements in Korea • The suburbs Policies and methods to expose suspected • The Sunbelt • Containment (also referred to as "contain communists within the United States communism") NUSTUNDERSTAND: Essential Knowledge from Period 7 (1890-1945) and Period 8 (1945-1980) Why did Americans debate policies and methodsdesignedto expose suspected communists within the UnitedStateseven as both parties supported the broader strategy ofcontaining How did the war-ravaged condition of Asia and Europe, the dominant U.S. role in the Allied victory, and postwar peace settlements allow the United States to emerge from the war as the most powerful nation on earth? (pp. 822-825) • Why did U.S. policymakers communism? (pp. 837-839) How did a engage in a Cold War with the authoritarian Soviet Union, seek to limit the growth of communist military power and ideological in uence, create a free-market global economy, and build an international security system? (pp. 823-833; 836-837) burgeoning private sector, federal spending,thebaby boom, and technological developments help spureconomic growth? (pp. 839-850) • As higher education opportunities and newtechnologies rapidly expanded, how did increasing social mobilityencouage the migration of the middle class to the suburbs and ofmany • As postwar tensions dissolved the wartime alliance between Western democracies and the Soviet Union, why did the United States develop a foreign policy based on collective security, international aid, and economic institutions that bolstered Americans to the South and West?(pp.844-850) • Why did the Sunbelt region emerge as a signi cantpolitical and economic force? (pp. 844-845) noncommunist nations? (pp.823-833; 836-837) • How did the United States seek to contain communism through military engagements in Korea? (pp. 833; 836-837) MUSTCONNECT:Essential Knowledge and Historical Thinking Skills and Reasoning Processes • Essential Knowledge: As higher education opportunities and new technologies rapidly expanded, S Contextualization AfteryoureadSection 34-16"The Smiling Sunbelt" (pp. 844-845), can you identify anddescribe increasing social mobility encouraged the migration of the middle class to the suburbs and many Americans to the South the historical context of the emergence oftheSunbelt? and West. The Sunbelt region emerged as a signi cant political and economic force. • Essential Knowledge: U.S. policymakers engaged in a S cold war with the authoritarian Soviet Union, seeking to limit the growth of Communist military power and ideological Comparison Afteryouhave read"Varying Viewpoints: Who Was to Blame for the Cold War?" (pp.850-851),can you create a Venn diagram that compares andcontraststhe in uence, create a free-market global economy, and build an revisionist or postrevisionist interpretations of theColdWar? international security system. •Essential Knowledge: Aspostwartensionsdissolved the wartime alliance between Western democracies and the Soviet Union, the United States developed a foreign policy based on collective security, international aid, and economic institutions that bolstered noncommunist nations. A Causation "Victorycelebrationshadbarely endedthe authors conclude, "before America's crumbling relationswith its wartime ally, the Soviet Union, secondary causes you identi ed. 822A fi fl fl fi fi Created with Scanner Pro fl threatened a newandeven more terrible international con ict" As you read thischaptet what event or series of events in the 1940s would youselect as the primary and secondary causes of the ColdWar?Witea paragraph explaining the difference between theprimaryand Created with Scanner Pro Created with Scanner Pro ou m Created with Scanner Pro i: cter,NYC The Granger Callecta Created with Scanner Pro iliii Created with Scanner Pro alrc ery WaterSndsGty inat Created with Scanner Pro Created with Scanner Pro 830 CHAPTER 34 The Cold War Congeals The Cold War Begins, 1945-1952 831 -nsive alliance at Brussels. They then invited the tinited States to join them. The proposal confronted nited States with a historic decision. America had teionally avolded entangling alliances,especially peacetime (if the Cold War could be considered eacetime). Yet American participation in the emerg coalition could serve many purposes: it would NAESEAIPLANS/ LLIN strengthen the policy of containing the Soviet Union: it would provide a framework for the reintegration o Germany into the European family; and it would reassure jittery Europeans that a traditionally İsolationist Uncle Sam was not about to abandon them to the marauding Russian bearor to a resurgent and domineering Germany. NNNTH ATLANTIC The Truman administration decided to join the 34.6 The Marshalt Plan Turns Enemies European pact, called the North into Friends The poster in this 1950 photograph in Berlin reads, "Berlin Rebuit with Help trom the Marshall Plan." Organization (NATO), granting it a transatlantic character. With white-tie pageantry, the NATO treaty wassigned in Washington on April 4, 1949. The twelve original signatories pledged to regard an attack on The Soviet menace spurred the uni cation of the armed services as well as the creation of a huge new national security apparatus. Congress in 1947 passed the National Security Act, creating the Department of Defense. The department was to be housed in the sprawling Pentagon building on the banks of the Potomac and to be headed by a new cabinet of cer, the sec- retary of defense. Under the secretary, but without cabinet status, were the civilian secretaries of the navy, the army (replacing the old secretary of war), and the air force (a recognition of the rising importance of airpower). The uniformed heads of each service were brought together as the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The National Security Act also es- tablished the National Security Council (NSC) to advise the president on secu- rity matters and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to coordinate the government's foreign fact gathering. The "Voice of America," authorized by Congress in 1948, began bearming American The Soviet threat was forcing the democracies of Western Europe into an unforeseen degree of unity. In 1948 Britain, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg signed a path-breaking treaty of PA351 of selected young men fromn nineteen to twenty- ve years of age. The forbidding presence of the Selective Service System shaped millions of young people's educational, marital, and career plans in the following quarter-century. One shoe at a time, a war-weary America was reluctantly returning to a war footing. Treaty one as an attack on all and promised to respond with "armed force" if necessary. Despite last-ditch howls from immovable isolationists, the Senate approved the treaty on July 21, 1949, by a vote of 82 to 13. Membership was boosted to fourteen in 1952 with the inclusion of Greece and Turkey, to fteen in 1955 with the 34.8 Reaching Across the Atlantic in Peacetime, 1948 When the United States joined with theVWestern European powers in the North Atlantic Alliance, soon addition of West Germany. Soviet aggression. The NATO pact was epochal. It marked a dramatic departure from American diplomatic convention, a gigantic boost for European uni cation, and a signi - cant step in the militarization of the Cold War. NATO becamethe cornerstone of all Cold War American policy toward Europe. With good reason pundits summed up NATO'S threefold purpose: "to keep the Russians out, the Germans down, and the Americans in." 34-8 Reconstructionand Revolution in Asia O5OPONA M... 5A3bl radio broadcastsbehind the iron curtain. In the same year, Congress resurrected the military draft, providing for the conscription Atlantic 34.7 The View from Russia American views of Russian ggression in the earty Cold War years were matched by Russian foars of American expansion. This Russian cartoon proclaims Bases" (1t rhymes in both Russian and English!), whicn sldcapitalbe looselytranslated as "Words and WarPreparaticon. red olve iststoogein the soldier's hip pocket is brandishing a wi sting branchinwhichisnestedatinyatomicbomb.He 5 t toan "Peace," "Defense and "Disarmament while stanaingned inthe over-sizesidearm burnished with a dollar sign, a moueoldier is wad of cash in the soldier's front pocket. Meanwhile planting an American base in Greece, a NATO member. U.S. bomber bases in Britain, Spain, France, and Italy are also show Reconstruction in Japan was simpler than in Germany, primarily because it was largely a one-man and onearmy show, The occupying American army, under the Supreme Allied commander, ve-star general Douglas MacArthur, sat in the driver's seat. In the teeth of vioent protests from Soviet of cials, MacArthur went nhexibly ahead with his program for the democrazation of Japan. Following the pattern in Germany, OpJapanese "war criminals" were tried in Tokyo from 946 to 1948, Eighteen of them were sentenced to prison terms, and seven were hanged. General MacArthur, as a kind of Yankee mikado, oyed stunning success.TheJapanesecooperated to dstonishing degree. They saw that good behavior andthe adoption of democracywouldspeed the end ne occupation-as it did. A MacArthur-dictated to be called the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, it overcame its historic isolationism in the wake of wars. By 1955 former enemy West Germany would be admitted to NATO to help defend Western Europe against constitution was adopted in 1946. It renounced militarism, provided for women's equality, and introduced Western-style democratic government-paving the way for a phenomenal economic recovery that within a few decades made Japan one of the world's mightiest industrial powers. Ironically, as with the U.S.- supported recovery of Western European economies, Japan's postwar ascendance eventually helped to end America's honeymoon as the unchallenged global economic kingpin. Despite such ironies, Japan proved an uncontestable postwar success story for American policymakers. The opposite was true in China, where a bitter civil war had raged for years between Nationalists and communists. Washington had halfheartedly supported the Nationalist government of Generalissimo Jiang Jieshi in his struggle with the communists under Mao Zedong (Mao Tse-tung). But ineptitude and corruption within the generalissimo's regime gradually corroded the con dence of his people. Communist armies Swept south, and late in 1949 Jiang was forced to ee with the remnants of his once-powerful force to the last-hope island of Formosa (Taiwan). The collapse of Nationalist China was a depressing defeat for America and its allies in the Cold War--the worst to date. At one fell swoop, nearly one-fourth of fl fi fi fi fi fi fi fi fi fi Created with Scanner Pro 832 CHAPTER 34 The Cold War Begins, 1945-1952 the world's population--some 500 million people was swept into the communist camp. The so-called fall of China became a bitterly partisan issue in the United States. Republicans, seeking out those who had "lost China," assailed President Truman and his bristly mustached secretary of state, Dean Acheson. They insisted that Denmocratic agencies, wormy with communists, had deliberately withheld aid from Jiang Jieshi (Chiang Kai-shek) to trip him into his fall. More bad news came in September 1949 when President Truman shocked the nation by announcing that the Soviets had exploded an atomic bomb- approximately three years earlier than many experts had thought possible. American strategists since 1945 had counted on keeping the Soviets in line by threats of a one-sided aerial attack with nuclear weapons. But atomic bombing was now a game that To outpace Alomic scientist Edward Condon (1902-1074 as carly as 1946-three years before the Sovietemd exploded their own atomic bomb--that Americome con dence in their nuclear monopoly was a dangern. delusion that could unleash vicious accusations and scapegoating: l Thelawsofnature,someseemtothink. areoursexclusively. . . Having createdan ai feusoicion and distrust, there will bepersons among us who think our nations can know nothing except what is learned by espionage. So, when other countries make atom bombs. these persons will cry 'treason' at our scientists, for they will nd it inconceivable that another country could make a bomb in any other way.) two could play. the Soviets in nuclear weaponry, Truman ordered the development of the "H-bomb" (hydrogen bomb)-a city-smashing thermonuclear weapon that was a thousand times more powerful than the atomic bomb. J. Robert Oppenheimer, for- mer scienti c director of the Manhattan Project and current chair of the Atomic Energy Commission, led a group of scientists in opposition to the program to design thermonuclear weapons on the grounds that it approached genocide. Albert Einstein, the physicist whose theories had helped give birth to the atomic age, declared that "annihilation of any life on earth has been brought within the range of technical possibilities. But Einstein and Oppenheimer, the nation's two most famous scientists, could not dissuade Truman, anxious over communist threats in East Asia, from proceeding with the H-bomb. The United States exploded its rst hydrogen device on a South Paci c atoll in 1952. Not to be outdone, the Soviets countered with their rst H-bomb explosion in 1953.The nuclear arms race had entered a perilously competitive Cvcle, spurred on by massive state support for defenserelated scienti c research in both countries (see "Makors of America: Scientists and Engineers," Section 34-9. po, 834-835). It was only constrained by the recognition that a truly hot Cold War would leave no world ior the communists to communize or thedemocracies to democratize. Peace through mutual terror brought a shaky stability to the superpower standoff. t 34-9TheKoreanVolcano Erupts Korea, the Land of the Morning Calm, heralded a new and more disturbing phase of the Cold War-a shoot- ing phase-in June 1950. When Japan collapsed in 1945, Soviet troops had accepted the Japanese surrender north of the thirty-eighth parallel on the Korean peninsula, and American troops had done likewise South of that line. Both superpowers professed to want the reuni cation and independence of Korea, a Japanese colony since 1910. But, as in Germany, each helped to set up rival regimes above and below the parallel. By 1949, when the Soviets and Americans had both withdrawn their forces, the entire peninsula was a bristling armed camp, with two hostile regimes eyeing each other suspiciously. The explosion came on June 25, 1950. Spearheaded by Soviet-made tanks, North Korean army columns rumbled across the thirty-eighth parallel. Caught at-footed, the South Korean forces were shoved back southward to a dan- gerously tiny defensive area around Pusan, their weary backs to the sea. President Truman sprang quickly into the breach. The invasion seemed to provide devastating proof of a fundamental premise in the "containment doctrine" that shaped Washington's foreign policy: even a slight relaxation of America's guard was an invitation to communist aggression somewhere. 34.9 The Hydrogen Bomb This test blast at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall lslands in 1954 was so powerful that one Japanese sherman was killed and all twenty-two of his crewmates were seriously injured by radioactive ash that fell on their vessel some eighty miles away. Fishing boats a thousand miles from Bikini later brought in radioactively contaminated catches. The Korean invasion prompted a massive expansİon of the American military. A few months before, Truman's National Security Council had İssued its famous National Security Council Memoran- dum Number 68 (NSC-68), recommending that the United States quadruple its defense spending. Ignored at rst because it seemed politically imposSible to Implement, NSC-68 got a new lease on life Trom the Korean crisis. "Korea saved us," Secretary Of State Acheson later commented. Truman now orđered a massive military buildup, well beyond what Was necessary for Korea. Soon the United States had 3.5 million men under arms and was spending SSO bilon per year on the defense budget-some 13 percent of the GNP. NSC-68 was a key document of the Cold War period, not only because it marked a major step in the militarization of American foreign policy, but also because it vividly re ected the sense of almost limitless possibility that pervaded postwar American society. NSC-68 rested on the assumption that the enormous American economy could bear without strain the huge costs of a gigantic program. Said one NSC-68 planner, fi fi fi fi fi fl fi fi fi fi fi fi fi fl fi rearmament "There was practically nothing the country could not do if it wanted to do it." Truman took full advantage of a temporary Soviet absence from the United Nations Security Council on June 25, 1950, to obtain a unanimous condemnation of North Korea as an aggressor. (Why the Soviets were absent remains controversial. Scholars once believed that the Soviets were just as surprised as the Americans by the attack. It now appears that Stalin had given his reluctant approval to North Korea's strike plan but believed that the ghting would be brief and that the United States would take little interest in it.) The Security Council also called upon all U.N. members, including the United States, to "render every assistance" to restore peace. Two days later, without consulting Congress, Truman ordered American air and naval units to support South Korea. Before the week was out, he also ordered General MacArthur's Japan-based occupation Douglas troops into action alongside the beleaguered South Koreans. So began the ill-fated Korean War. Of cially, the United States was simply participating in a U.N. "police action." Participating nations, including Great Britain, Canada, and the Philippines, did make signi cant troop contributions. But the United States provided 88 percent of the U.N. contingents, and General MacArthur, U.N. commander of the entire operation, took his orders from Washington, not from the Security Council. 34-10 The MilitarySeesawin Korea Rather than ght his way out of the southern Pusan perimeter, MacArthur launched a daring amphibious landing behind the enemy's lines at Inchon. This bold gamble on September 15, 1950, succeeded brilliantly; within two weeks the North Koreans had scrambled back behind the "sanctuary" of the thirty-eighth parallel. Truman's avowed intention was to restore South Korea to its former borders, but the pursuing South Koreans had already crossed the thirty-eighth parallel, and there seemed little point in permitting the North Koreans to regroup and come again. The U.N. General Assembly tacitly authorized a crossing by MacArthur, whom President Truman ordered northward, provided Created with Scanner Pro fi 833 The Cold War in Asia Scientistsand Engineers sbatomicparticles and space-bound satelites do not respect politicalboundaries. Disease-carrying viuses spread across the gobe. Radio waves and Internet communications reach every comer of planet Earth. At rst glance science, technology, and medicine appear to be quintessentially international phenomena. Scientists often pride themselves on the universal validity of scientilic knowledge and the transnational character of scienti c networks. In a world marked by political divisions, science evidently knows no bOunds. But a closer look reveals that national context does inuence the character of scienti c enterprise. American scienitistshave repeatedly made Signi cant contributions to the lite of the nation. They, in turn, have been shaped by its unique historical circumstances-especially America's intensifying concerns about national security in the twentieth century. Once marginal players in global intellectual lite, American scientists now stand at the forefront of worldwide scienti c advancement. In many ways the rise of American science has kept pace with the arrival of the United States as a world power. Nowherewas this trend more evident than in the story of "Big Science." The unusual demands of America's national security state during VWorldWar lIl and the Cold War required vast scient c investments. The result was Big Science, or multidisciplinary research enterprises of unparalleled size, SCope,and cost. Big Science and Big Technology meant big bucks, big machines, and big teans of sclentists and engineers. The close link between government and science was not new--precedents stretched as far back as the founding of the Natonal Academy of Sciences during the Civil War. But the depression-era Tennossoe Valley Authority (TVA) and the wartime Manhattan Project ushered in ventures of colossal scale and ambition. As the head of the TVA Wrote in 1944, "There is almost nothing, however fantastic, that (given competant organization) a team of engineers, scientists, and administrators cannot do today." Cold War competition with the Soviets translaled into huge government investmonts in physics, chomistry, and aerospace. The equation was simple: national security depended on technological superiority, which entailod costly facities for scienti c rosearch and ambitious efforts to recruit and traln sciontists. In the 1950s dofense projects employed two-thirds of the nation's scientists and engineers. Laboratories, roactors, accelorators, and observatories proliferatod. Aftor the Soviets launched the world's rst art cial satolite (Sputnik ) in 1957, thointermational space raca bocame Amorica's top scienti c priority. To land astronauts on the moon, the National Aoronautics and Space Acministration (NASA) spent a whopping $25.4 billion over elevon yoars on Projoct Apollo. Another massive aorospace mission, President Reagan's controvorsial Strategic Dofenso Initiativo (or "Star Wars"), consumed somewhere betwoon $32 blion and $71 bilion between 1984 and 1994. In America's burgooning "research universitios, the fedoral govornment found willing partners in the pronotion & 34.11 A Scientist Working in Her Lab This medical school professor researching pancreatic regeneration was part of the surge of women pursuing scienti c careers, particularly in the blological sciences. By 2004 as many women as men enrolled in medical schools, and minority enrollment climbed as well, In that year 7 percent of entering medical students were Latino, and 6.5 percent were African American. 34.10 Launching Apollo 11 NASA ight directors monitor the launch of the Apollo 11 lunar landing mission from the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, Texas in July 1969. of the scienti c enterprise. University-employed scientists. largely paid by government grants, concentrated on basic research, accounting for over 75 percent of theestimated $51.9 bilion spent on basic science in 2008. Meanwhile, private industry spent additional billions on applied re- search and product development. For consumers of air bags, smart phones, and other high-tech gadgets, these investments yielded rich rewards as innovative technologies dramatically improved the quality of life. Over the course of the twentieth century, American corporations spearheaded a global revolution In communications and information technology, American Telephone and Telegraph (AT8T) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) attended the birth of telephones, radio, and television. Apple, International Business Machines ((BM), and Microsoft helped put personal computers on evory desk. Government and industry scientists together invented the Internet. Twentioth-century advances in medical scienco and technology have also revolutionlzed American Ives. ThankstoOnew drugs, devices, and methods of ment, the average life expoctancy in tho United States loapt trom 473 yoars in 1900 to 78.7 yoars in 2011. In the rst hai of the twentioth century, physiclans discovered hormones and vitamins, introduced penicilin and other antlbioteS, bene ts, including new diagnoses for genetic defects, innovative therapies, and untold commercial applications. Coordinated by the Department of Energy and the National Institutes of Health, the project engaged thousands of scientists in universities and laboratories across the nation and around the globe. To achieve such innovation, Big Science typicatly demands complex teans of scientists, engineers, and technicians. When traditional channels of recruitment came up short, scienti c institutions increasingly recruited toreigners, women, and minorities (see Figure 34.1). Immigrants and exiles played key roles in the development of the atomic bomb and Cold War weaponry. Long relegated to junior positions as assistants and technicians, women and minorities have recently made signi cant gains in the "white man's world" of science. Yet severe imbalances persist, not only in academic science and engineering but in the high-tech companies that have become some of the world's most powerful enterprises in the early twenty- rst century. In 2010 women represented 31 percent of employed doctoral scientists and engineers in the United States, African Americans 3 percent, and Hispanics 4 percent, while the foreign-born accounted for 44 percent. After dominating the world of basic and applied research from the 1960s through the 1990s, American scientists began winning fewer prizes and patents and publishing fewer scienti c papers than their peers in Europe and Asia. Experts predicted that current school-age Americans would not be able to meet the rising dernand for scienti c expertise. Moreover, fewer foreigners are arriving to ll the gap, as immigration laws becomne more restrictive and international competition for their labor heats up in places like Brazl, China, and India. For the United States to retain preeminence in science, it must continue to welcome all talent to the eld. That means attracting both foreign-born scientists and a more diverse pool of young American students whose brainpower helped make the nation a scienti c colossus. Percent 1980 30 1990 2000 2 2010 20 1 10 and oxporimented wlth Insulin therapy tor diabotesa radiation therapy for ancer. More recently. cuttin edge medical science has nurtured in-vito ortilizatic eloped respirators, artiticial hoarts, and other meda devicos; and largaly containod the AIDS epidormic.hs Much of the optimism for future medical breakuhich centers on the $3 billion Hunan Genome Project, whicn Completod its mapping and soquencing of all the genetc material in the human body in 2003. Deemed ntless grall"'ofgenomlcs research, the project pron fermale Black Latino Foreign born FIQUR 34.1 Demographic Pro le of Women, Minorities, and the Foreign- in NonacademlcSclence andEngineeringOccupations,1980-2010 Source:Sclence and Engineering Indicators, 2002 and 2014 834 835 fi fi fi fi fi fi fi fi fi fi fi fi fi fi fi fl fi fi fi fl fi fi fi fi fi Created with Scanner Pro fi fi fi ingbackdown thepeninsula.The ghtine eel. CHINA into a frostbitten stalemate on the icy terraiWsank the thirty-eighth parallel. An imperiousMacArthur, humiliated by thisrou NORTH KOREA yongyang pressed for drastic ,Pyongyang 38"N 38N SOUTH KOREA $OUTH KOREA Pusan 1297 o Pusan 1257 Noth Korean atack Norh Koreanattack Nov. 25, 1950 USA July27, 1953usSa MANCHUPIA ANCHRk CHINA CHINA KOREA NORTH "Pyongjan P'yongangKOREA 38'N 38*N inchon block- concept of a "limited war" and insisted that "there is no substitute for victory. Truman bravely resisted calls for nuclear escalatlon When MacArthur began to criticize the president's policies publicly, Truman had no choice but to remove the insubordinate general from command-which Pusan 4130E 125 -Chneecountetatack + MacArthuratack - Amsice lne etory heldby Jsouth Koeanforces Tentoy hedby JNorth Koean forces 0 100 "imbecile," a "Judas," and an appeaser of communism. This domestic response to the Truman-MacArthur conlict offered just a hint of the depth of popular passions coursing through the Cold War at home. 34-11 The Cold War Home Front As never before, international events deeply shaped American political and economic developments at home in the years after World War II. The solidifying Cold War with Russia fueled domestic political conict and drew new boundaries for acceptable political opinion. Meanwhile, the postwar economic order that the United States helped to forge, combined with Cold War spending and investment, lald the foundations for a Long Boom that transformed the next several decades. the country over A new anti-red chase accelerated within America's relations froze. Many nervous citizens feared that communist spies, paid with Moscow gold, were undermining the government and treacherously misdirecting foreign policy. In 1947 Truman launched a massive "loyalty" program. The attorney general drew up a list of ninety supposedly disloyal organizations, none of which was given the opportunity to prove its innocence. The Loyalty Review Board investigated more than 3 millon federal employees, some 3000 of whom either resigned or were dismissed, none under formal indictment. Individual states likewise became intensely securityConscious. Loyalty oaths in increasing numbers were demanded of employees, especially teachers. The gnawing question for many earnest Americans was, Could the natlon continue to enjoy traditlonal freedoms-especlally freedom of speech, freedon of thought, and the right of political dissent-in a Cold War climate? KOREA Pusan 200 K Front MAP 34.3 The Shifting Front in Korea EFLRING AOrMACARTHUR, that there was no armed intervention by the Chinese In 1949 eleven or Soviets (see Map 34.3). communists were brought before a New York jury for violating the Smith Act of 1940, the The Americans thus raised the stakes in Korea, ist peacetime antisedition law since 1798, Convicted of advocating the overthrow of the American govern- and in so doing quickened the fears of another poten- tial player in this dangerous game. The Chinese had publicly warned that they would not sit idly by and watch hostile troops approach the strateglc Yalu River boundary between Korea and China, But MacArthur pooh-poohed all predictions of an effective intervention by the Chínese and reportedly boasted that he would "have the boys home by Christmas." MION PyDL1e OPINIC ment by force, the defendants were sent to prison. The Upreme Court upheld their convictions in Dennis v. United States (1951). The House of Representatives in ablished the House Un-American 34.12 Truman Takes the Heat 837 he did on April 1, 1951. In July, truce discussions eean in a rude eld tent near the ring line but were almost inmediately snagged on the issue of prisoner exchange. Talks dragged on unproductively for neatly (wo years while men continued to die. Meanwhile, MacArthur, a legend in his own mind, returned to an uproarious American welcome, whereas in many circles Truman was condemned as a "pig." an borders as U.S,-Soviet SOUTH 3OUTH KOREA 35N He favore Chinese and their supply lines. But Washington poli cymakers, with anxious eyes on Moscow, refusedto enlarge the already costly con ict. The chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff declared that a wider clashin Asia would be "the wrong war, at the wrong place,at the wrong time, and with the wrong enemy."Europe. not Asia, was the administration's rst concern: and the USSR, not China, loomed as the more sinister foe. Two- sted General MacArthur felt that he was being asked to ght with one hand tied behind his back. He sneered at the 40N AORTH Seoul retaliation. ade of the Chinese coast and bombardment of nese bases in Manchuria. He even suggested that th United States use nuclear weapons on the advancine Seou 1938 had Activities Committee (HUAC) to investigate "subversion." In 34.13 Richard Nixon, Red-hunter Congressman Nixon examines the micro lm that gured as important evidence in Alger Hiss's conviction for perjury in 1950. 1948 committee member Richard M. Nixon, a rising GOP star and ambitious red-catcher, led the chase after Alger Hiss, a prominent ex-New Dealer and a distinguished member of the "eastern establishment." Accused of being a communist agent in the 1930s, Hiss demanded the right to defend himself. He dramatically met his chlef accuser before HUAC in August 1948. Hiss denied everything but was caught in embarrassing falsehoods, convicted of perjury in 1950, and sentenced to ve years in prison. The stunning success of the Soviet scientists in developing an atomic bomb was attributed by many to clever communist sples who stole American secrets. Notorlous among those who had allegedly leaked atomic data to Moscow were two American citizens, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. They were convicted in 1951 of espionage and sent to the electric chair in 1953--the only people in American history ever executed in peacetimne for espionage. Though declassied evidence has subsequently strengthened the case against the Rosenbergs, at the time they enjoyed the support of many Americans who believed their claims of innocence. Their sensational trial and electrocution, combined with sympathy for their two orphaned Created with Scanner Pro fi fi fl MANCHLKa NORTH KOREA Truman versus MacArthur MacArthur erred badly. In November 1950tensof thousands of Chinese "volunteers" fell upon histashly overextended lines and hurled the U. Sept 14, 1950 USsa USSR CHINA fi fi TheCold War Begins, 1945-1952 CHAPTER 34 lune 25, 1950 fl fi fi fi 836 833 The Cold War Begins, 1945-1952 CHAPTER 34 children, began to sour some sober citizens on the excesses of the red-hunters. Was America really riddled with Soviet spies? Soviet agents did in ltate certain government agencies, though without severely damaging consequences, and espionage may have helped the Soviets to develop an atomic bomb somewhat sooner than they would have otherwise. Truman's loyalty program thus had a basis in reality. But for many ordinary TheScourgeofMcCarthyism Some Republicans sharply criticized Joseph McCowt Maine's Senator Margaret Chase Smith, for exam declared, reoroachedMcCarthy in front of ahugenational l1 don't want to see the RepublicanPartyride to political victory on the Four Horsemen of Calumny-Fear, Ignorance, Bigotry andSmear )) Americans, the hunt for communists was not just about fending off the military threat of the Soviet Union. Unsettling dangers lurked closer to home. While men like Nixon and Senator Joseph McCarthy led the scarch for communists in Washington, conservative politicians at the state and local levels discovered that all manner of social changes-including increased sexual freedom and agitation for civil rights-could conveniently be tarred with a red brush. Anticommunist crusaders ran sacked school libraries for "subversive" textbooks and drove debtors, drinkers, and homosexuals, all alleged to be security risks, from their jobs. Some Americans, including President Truman, realized that the red hunt was turning into a witch hunt. In 1950 Truman vetoed the McCarran Internal Security Bill, which among other provisions authorized the president to arrest and detain suspicious people during an "internal security emergency." Critics protested that the bill smacked of police-state, concentration-camp tactics. But the congressional guardians of the Republic's liberties enacted the bill over Truman's veto. The demagogic politics of anticommunism found its most dangerous practitioner in Joseph R. McCarthy, an obstreperous Republican senator from Wisconsin. Elected to the Senate on the basis of a trumped-up war-hero record, the swaggering senator crashed into the limelight in February 1950 when he CcusedSec- of StateDeanAcheson of knowinglyemplovine 205 Communist party members. Pressed to ealthe names, MCCarthy later conceded that there were only 57 genuine communists and in the end failed to ider tify even one. Some of McCarthy's Republica colleagues nevertheless realized the partisan usefulnes Menace The Wisconsin senator (standing) often made a mesmerizing spectacle out of his investigations into the allegedly wide-ranging domestic Communist conspiracy. But his recklessness got the better of him during the nationally televised ArmyMcCarthy hearings in 1954, where army counsel Joseph Welch (seated) proved a sympathetic and effective antagonist. wcvision audience for threatening to slander a young lawyer on Welch's staf: Until this moment, Senator, I think I never really gauged your cruelty or your recklessness Little didI dream you could be so cruel as to do aninjury to that lad.... I t were in mypowerto forgive you for your reckless cruelty, I would do so.I like to think that I am a gentleman, but your forgiveness will have to come from someone other than me....Have you nodecency,sir, at long last? Have you left no senseof decency?) of this kind of attack on the Democratic administra. tion. Ohio's Senator John Bricker reportedly said,"Ioe you're a dirty s.o.b, but there are times when you've got to have an s.o.b. around, and this is one ofthem McCarthy's rhetoric grew bolder and hisaccusations spread more wildly over the next severalyears. He saw the red hand of Moscow everywhere. The Democrats, he charged, "bent to whispered pleasfrom the lips of traitors." Incredibly, he even denounced General George Marshall, former army chief of staf and ex-secretary of state, as "part of a conspiracy so immense and an infamy so black as to dwarf any pre. vious venture in the history of man." became known as McCarthy--and what McCarthyism- ourished in the seething ColdWar atmosphere of suspicion and fear. The senator was neither the rst nor the most effective red-hunter, but he was surely the most ruthless, and he did the most damage to American traditions of fair play and free COMHLNST PATYORANIZAIKNUSA K 9n0 34.14McCarthy Mapsa ln a moment ofhigh drama during the Army-McCarthy hearings,attorneyJoseph Wlch (18g0-196o) speech. The careers of countless of cials, writers, and actors were ruined after "Low-Blow Joe" had "named" them, often unfairly, as communists or communist sympathizers. Politicians trembled in the face of such onslaughts, especially when opinion polls showed that a majority of the American people approved of McCarthy's crusade. At the peak of his powers McCarthy effectively controlled personnel policy at the State Department. One baleful result was severe damage to the morale and effectiveness of the professional foreign service. In particular, McCarthyite purges deprived the government of a number of Asian specialists who might have counseled a wiser course in Vietnam in the fateful decade that followed. McCarthy's antics also damaged America's international reputation for fair and open democracy at a moment when it was important to keep Western Europe on the United States' side. McCarthy nally bent the bow too far when he attacked the U.S. Army. The embattled military men fought back in thirty- ve days of televised hearings in the spring of 1954. Up to 20 million Americans at a time watched the Army-McCarthy hcarings in fascination while a boorish, surly McCarthy publicly cut his own throat by parading his essential meanness and Irresponsibility. A few months later, the Senate formally condemned him for "conduct unbecoming a member." Three years later, unwept and unsung, McCarthy died of chronic alcoholisn. But "McCarthyism" has passed Into the English language as a label for the dangerous Torces of unfalrness and fear that a democratic society can unleash at its peril. Beyond ghts over security and civil liberties, the Cold War shaped American culture in complex and profound ways. Many Americans interpreted the contict between the capitalist West and the communist-dnd of cially secular--East in religious terms. Truman found support for casting the Cold War as a battle be- tween good and evil from theologians like the in uential liberal Protestant clergyman Reinhold Niebuhr (1892-197 1). A vocal enemy of fascism, communism, and paci sm in the 1940s and 1950s, Niebuhr divided the world into two polarized camps: the "children of light" and the "children of darkness." For Niebuhr, Christian justice, including force if necessary, required a "realist" response to fl fi fl fi fi fi fl fi fi fi fi fi "children of darkness" like Hitler and Stalin. But Niebuhr's realisn also emphasized the dangers of fallibility and the limits of power, in contrast to the more crusading spirit of conservative Christian anticommunists. The postwar decades saw an emphasis on religious belief of any kind as a distinguishing feature of the "American Way." to be defended against atheistic communism. Congress's decision to insert the words "under God" into the Pledge of Allegiance in 1954 epitomized this Cold War impulse. The Cold War in uenced domestic politics and society in still other ways. Radical voices in institutions ranging from unions and universities to churches and civic organizations were muzzled. Amnong those voices were sorme of the most forceful advocates for racial justice in the United States. Even moderate agitators for civil rights were often slandered as communists and fellow travelers. But at the same timne, competition with the Soviets for international support, like the earlier Allied ght against fascism during World War II, placed pressure on the United States to live up to its own stated democratic ideals. This created new political opportunities and rhetorical tools for advocates to press civil rights claims. An early example of the new international politics of civil rights came in 1948, when President Truman issued his landmark Executive Order 9981, desegregating the armed forces. 34-12 PostwarEconomicAnxieties The communist menace was not the only specter haunting Americans after World War 1. Economic uncertainty also loomed over the new peace. The decade of the 1930s had left deep scars. Joblessness and insecurity had pushed up the suicide rate and dampened the marriage rate. Babies went unborn as pinched budgets and sagging self-esteem wrought a sexual depression in American bedrooms, The war had banished the blight of depression, but would the respite last? Grim-faced observers were warning that the war had only temporarily lifted the pall of economic stagnation and that peace would bring the return of hard times. Homeward-bound GIs, so the gloomy pre- dictions ran, would step out of the arny's chow lines and back into the breadlines of the unemnployed. Created with Scanner Pro fi 839 C20 CHAPTSR Economic Uncertainty and Poitical Tensions The Cod WarBegins, 1945-1952 The faltering economy in the tnitial postwaryears threatened to con rm the worst predictions of the đoomsayers who foresaw another Great Depression. Real gross national product (GNP) slumped sickeningly in 1946 and 1947fromn its wartime peak. With the removal of wartime price controls, prices levitated by 33 percent in 1946-1947. An epidemic of strikes Swept the country. During 1946 alone some 4.6 million laborers laid down their tools, fearful that soon they could barely afford the autos and other consumer goods their war-commandeered factories twould soon manufacture. The growing muscle of organized labor deeply annoyed many conservatives. They had their revenge against labor's New Deal gains in 1947, when a Re- publican-controlled Congress (the rst in fourteen years)passed the Taft-Hartley Act over President Truman's vigorous veto. Labor leaders condemned the Taft-Hartley Act as a "slave-labor law." It outlawed the "closed (all-union) shop, made unions liable for damages that resulted from jurisdictional disputes among themselses, and required union leaders to take a non- communist oath. Taft-Hartley was only one of several obstacles that slowed the growth of organized labor in the years after World War lI. In the headydays of the New Deal, unions hadspread swiftly in the North, especially in huge manufacturing industries like steel and automobiles. But labor'spostwar efforts to organize in the historically antiunion regions of the South and West proved frustrating. TheCIO's Operation Dixi, aimed at unionizing southern textile workers and steelworkers, failed miserably in 1948 to overcome white workers' lingering fears of racial mixing. Anticommunist purges removed from labor's ranks some of its most active organizers. And most importantly, workers in the rapidly rowing Ser. vícesector of the economy proved much moro if cuh wanize than the thousands of assemb to ne w ers who in the 193Oshad poured into the unions. Organized labor played a sionie andt:in shaping the onomic and political order in theUnited States for several decades after World War IL. But the number of organized private-sector workers WO in the1950sand then begin a long, slowdecline id peal th persistedinto the twenty- rst century. Democratic administration meanwhile took somesteps to forestall an economic downturn. Ir war factories and other government intalla Ilations Sold to privatebusinesses at re-sale prices. It secured p of the Employment Act of 1946. kingPassage i it gov. ernment policy "to promote maximum employment production, and purchasing power." The actcreated three-member Council of Economic Adviser to pro vide the president with the data and the rec tions to make that policy a reality. Most dramatic was the passage of the Service. men's Readjustment Act of 1944-better known a : sthe GI Bill of Rights, or the GI Bill. Enacted partly Out of fear that the employment markets would never be able to absorb 15 million returning veterans at war's end, the GI Bill tided ex-soldiers over as members of the "52-20 Club (S20 a week for up to 52 weeks) and made generous provisions for sending the for- mer soldiers to school. In the postwar decade,some 8 million veterans advanced their education atUncde Sam's expense. The majority attended technical and vocational schools, but colleges and universities were crowded to the blackboards as more than 2 million ex-Gls stormed the halls of higher learning. Thetotal eventually spent for education was some $14.5 billion taxpayer dollars--$2 billion more than the MarDlan. The act also enabled theVeterans Administion (VA) to guarantee about Sl6 billion in loans for terans to buy homes, farms, and small busin raising educational levels and stimulating the con- ction industry, the GI Bill powerfully nurtured he robust and long-lived economic expansion that entually took hold in the late 1940s and profoundly shaped the postwar era. DEM 34-13 Democratic Divisions in 1948 Attacking high prices and "High-Tax Harry" Truman. he Republicans had won control of Congress in the ANDRCACY congressional elections of 1946. Their prospects had seldom looked rosier as they gathered in Philadelphia to choose their 1948 presidential candidate. They noisily renominated warmed-over New York governor Thomas E. Dewey, still as debonair as if he had stepped out of a bandbox. Also gathering in Philadelphia, DemoCratic politicos looked without enthusiasm on their hand-medown president and sang. "I'm Just Mild About Harry." But a "dump Truman" movement collapsed when war hero Dwight D. Eisenhower refused to be drafted. The peppery president, unwanted but undaunted, was then chosen in the face of vehement opposition by southern delegates, alienated by his strong stand in favor of civil rights for blacks, especially his desegrega- tion of the military. Truman's nomination split the party wide-open. Embittered southern Democrats from thirteen states, like their re-eating forebears of 1860, met in their oWn convention, in Birmingham, Alabama, with Confederate ags brashly in evidence. Amid scenes of heated de ance, these "Dixiecrats" nominated Governor J. Strom Thurmond of South Carolina on a States' Rights party ticket. To add to the confusion within Democratic ranks, former vice president Henry A. Wallace threw his hat into the ring. Having parted company with the adnminIstration over its get-tough-with-Russia policy, he was nominated by the new Progressive party34.15 Going to College on the GI Bil Financed by the federal government, thousands of Wortd War ll veterans crowded into college classrooms in the late 1940s. Universities struggled to house these older students, many of whom already had families. Pennsylvania State College resorted to setting up hundreds of trailers. veritable menagerie of disgruntled former New Dealers, starryeyed paci sts, well-meaning liberals, and communisttronters. Wallace, a vigorous though perhaps unrealistic liberal, assailed Uncle Sam's "dollar imperialism" from the stump. Considered by some the "Pied Piper of the Politburo," he took a Soviet-friendly line that earned hin drenchings with rotten eggs in hostile cities. But to is supporters, Wallace raised the only hopeful voice in the deepening gloom of the Cold War. With the Democrats ruptured three ways and the Republican congressional victory of 1946 just past, Dewey'sVictory seemed assured. Cold, sımug, and overcontident, he con ned himself to dispensing soothing-syrup 34.16 The Harried Piano Player, 1948 Besieged by the left and right wings of his own party, and by a host of domestic and foreign problems, Truman was a long shot for reelection in 1948. But the scrappy president surprised his legions of critics by handily defeating his opponent, Thomas E. Dewey. trivialities like "Our future lies before us." The seemingly doomed Truman ("to err is Truman," his critics mocked) had to rely on his gut ghter" instincts and folksy personality. Traveling the country by train to deliver some three hundred "give 'em hell" speeches, he lashed out at the Taft-Hartley "slave-labor law and the "do-nothing" RepublicanCongress, while whipping up support for his program of civil rights, improved labor bene ts, and health insurance. On election night the Chicago Tribune ran off an early edition with the headline "DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN." But in the morning, it turned out that "President" Dewey had embarrassingly managed to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory. Truman had swept to a stunning triumph, to the complete bewilderment of politicians, pollsters, prophets, and pundits. Even though Thurmond took away 39 electoral votes in the Deep South, Trumnan won 303 electoral votes, primarily from the South, Midwest, and West, besting Dewey's largely Eastern-based 189 total. To make the victory sweeter, the Democrats regained control of Congress as well, thanks especially to support from Republican-wary farmers, workers, and African Americans. Elected in his oWn right, Trumnan outlined a Sweeping Fair Deal program in his 1949 message to Congress. It called for improved housing, full employment, national health insurance, a higher minimum wage, better farm price supports, new TVAS, an fi fi fi fi fl fi fi fi fi fi fi Created with Scanner Pro fi 841 8A2 CTER 34 The CodWarBegirs, 1945-1952 0seC As Truman's Fair Deal was rebuffed by a hor continued their march into the work place in the Congress,critics like the conserative New DEWEY DETEATS TRARMA York Dai Neusgioatedthat theodiousNew Dealwas hoy vanquished: (l TheNewDeal is kaput like the Thirty Yere War or the BlackPlague or other disasters... (lts demise] is like corming out of the darkness into sunlight. Like feeling clean again after a long timeinthemuck.) 34.17 That Ain't the Way I Heard It! Truman wins. extension of Social Security, and increased aid to developinz countries. But most of the Fair Deal fell vic- Americans, some 6 percent of the world's peonle enjoying about 40 percent of the planet's wealth. Nothing loomed larger in the history of thepostWorld War II era than this fantastic eruption of afu. ence. It did not enrich all Americans, and it did not touch all people evenly, but it transformed the livesof a majority of citizens and molded the agenda of politic housing in the Housing Act of 1949, and extending Americans the con dence to exercise unprecedented international leadership in the Cold War era. 199 +14 TheLongEconomicBoom, 1950-1970 Gross national product began to clinmb haltingly in 1948. Then, bezinning about 1950, the American economy surzed onto a dazzling path of sustained zrowth that was to last virtually uninterrupted for two decades. America's economic performance became the envy of the world. National income nearly doubled in the 1950% and almost doubled again in the 19605, shooting through the trillion-dollar mark in 1973. families owned their own cars and washing machlnes and nearly 90 percent owned a television set-a ga0 get invented in the 1920s but virtually unknown un tll the late 1940s. In another revolution of swecping consequernces,almost 60 percent of Amerlcan families OWned their own homes by 1960, compared with less In his inaugural address in January 1949, President Harry S. Truman (ı884-197a) said, ll Communismisbasedon the belief that man is 50 weak and inadequate that he is unable to govern himself, and therefore requires the rule of strong masters.... Democracyisbased on the conviction that man has the moral and intellectual capacity, as well as the inalienable right, to govern himself with reason and justice,) than 40 percent in the 1920s. Of all the bene claries of postwar orosperlty, ever, urban of ces and shops provided a bonanz employment for female workers. The greatmajoority of to women, new jobs created in the postwar era went yOut as the service sector of the economy dramaticaly grew the old industrial and manufacturn sectors. wotk Womenaccounted or a quarter of theAmerie nearlyhalf force at the end of World War Il and for Women fi fi fi fi fi fi fi fl fi fi fi fi fi 93 81 51 522 81.7 418 4.9 1980 134.0 252.7 299.3 199 2721 200 294.5 616:1 200 661.023 188 S693.498 20.1 201 196 677.856 2013 19:2 183 633,446 2014 12:2 603457 201 589,659 201 593372 154 602.783 14.8 2017, est 160 400 500 600 32 31 159 652570 2018, est 4.3 20.7 705557 2012 4.0 20.2 200 201 4.0 20.0 551.3 300 3.0 16.5 495.3 200 3.7 17.9 200 100 5.2 23.9 2007 0 6.4 26.7 700 800 0 10 3. 20 30 40 50 60 0 12 Percentage FIGURE 34.2 National Defenso Budget, 1940-2018* Gross national product (GNP) was used before 1960, It includes income from overseas Investment and excludes pro ts generated in the United States but accruing to foreign accounts. Gross domestic product (GDP), used thereafter, excludes overseas pro ts owed to American accounts but includes ie value of all items originating in the United States, regardless of the destination of the Prots, Until recent years those factors made for negligible differences in the calculation of national and domestlc product, but most economists now prefer the latter approach. Urces: Statistical Abstract of the United States,2014, from US Of ce of Management and Budget vongressional Budget Of cel, Budget of the United Slates Government, Historical Tables, annual, ps//www.whitehouse.gov/omb/historical-tables/ ve decades later. Yet even aas Created with Scanner Pro fi PERCENTAGE OF GNP/GDP 322 Blions of dollars (unadyusted for in ation) onereapedgreater rewards than women. More t the labor pool 1970 industries such as aerospace, plastics, 175 196048.1 1985 tíal inproverments to many Americans' lives. high-technology 1950 137 vast new welfare programs, like Medicare; and it gave As the gusher of postwar prosperity poured forth its riches, Americans drank deeply from the gildedgoblet. Millions of depression-pinched souls sought to makeup for the sufferings of the 1930s. They determined to"get theirs" while the getting was good. A people who had once considered a chicken in every pot the standard of comfort and security now hungered for two cars in every garage, swimming pools in their backyards,vacation homes, and gas-guzzling recreational vehicles. The size of the "middle class," de ned as households carning between $3000 and S10,000 a year, doubled from pre-Great Depression days and included 60 percent of the American people by the mid-1950s. By the end of that decade, the vast majority of American economic upturn of 1950 was fueled by massive appropriations for the Korean War, and defense spending accounted for some 10 percent of the GNP throughout the ensuingdecade.Pentagon dollars primed the pumps of PERCENTAGE OF FEDERAL BUDGET OUTLAYS in raising the minimum wage, providing for public old-açe insurance to many more bene ciaries through the Social Security Act of 1950. Short-term legislative of a "permanent war economy" (see Figure 34.2). The 34-15 The Roots ofPostwarProsperity outhern Dernocrats. The only major successes came cbstacles to reform, howevet, paled against seismic shifts in the domestic economy that brought substan- the 1950s and 1960s rested on the underpinnings of colossal military budgets, leading some critics to speak What propelled this unprecedented economic explosion?World War II itself provideda powerful stimulus. While other countries had been ravaged by years of ohting, the United States had used the war crisis to and society for at least two generations. Prosperity underwrote social mobility; it paved the way for theeventual success of the civil rights movement; it funded tin toconzressionalopposition from Republicans and re up its smokeless factories and rebuild its depression-plagued economy. Invigorated by battle, America had almost effortlessly come to dominate the ruined global landscape of the postwar period. Ominously, much of the glittering prosperity of O40s and 1950s, popular culture glori ed the tradiinnal feminine roles of homemaker and mother. The lash between the prescriptive demands of suburban ousewifery and the realities of employment eventually sparked a feminist revolt in the 1960s. 1940}16 843 ava Shared Post-War FProsperity 3 4 5 6 Percentage 7 8 9 10 fi an to rupture in the 1970s, it signaled theb be. of the end of the postwar golden age (see Finning on p. 1001). 'Also contributing to the vigor of the postwarecon. omy were some momentous changes in the nation's basic economic structure. Conspicuous was he erating shift of the work force out of agriculture whi achieved productivity gains virtually unmatck b any other economic sector. The family farm became an antique artifact as consolidation nearly pro duced giant agribusinesses able to employ costly ma chinery. Thanks largely to mechanization and to rich new fertilizers--as well as to government subsidies and price supports-one farmworker by the centurv' end could produce food for over fty people, compared with about fteen people in the 1940s.Farmers whose forebears had busted sod with oxen or horses now plowed their elds in air-conditioned tractorcabs, listening on their stereophonic radios to weather fore. in productivity. In the two decades after the outbreak casts or the latest Chicago tions. Once the mighty backbone of the agricultural produce nearly twice as much in an hour's labor as commodities market quota- Republic, and still some 15 percent of the labor force at the end of World 2 percent of working War II, farmers Americans made up a slim by the turn of the twenty- rst century-yet they fed much of theworld. 4-16 TheSmilingSunbelt nearly double that of the old industrial zones of Northeast (the "Frostbelt"). In the 1950s ifornia and sisters from one another. One sign of stresswasthephenomenalpopularity oI tiaccounted for one- fth of the entirenation'spop- rose as its 34-17 TheRush to the Suburbs In all regions America's modern migrants--if they were white- ed from the cities to the burgeoning new suburbs in the initial postwar decades (see "Mak- eight Americans. The Sunbelt was a new frontier for Americans afWorld War II. Modern pioneers came in search of iobs, a better climate, and lower taxes. Jobs they found ers of America: The Suburbanites," pp. 846-847). While other industrial countries struggled to rebuild their war-ravaged cities, government policies in the United Statesencouraged movement away from urban in abundance, especially in the California electronics industry, in the aerospace complexes in Florida and Texas,and in the huge military installations that pow- centers. Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and Veterans Administration (VA) home-loan guarantees made it more economically attractive to own a home in the suburbs than to rent an apartment in the city. Tax deductions for interest payments on home mortgages provided additional nancial incentive. And government-built highways that sped commuters erful southern congressional representatives secured for their districts (see Map 34.4). A Niagara of federal dollars accounted for much of the Sunbelt's prosperity, though, ironically, southern and western politicians led the cry against government spending. By the early twenty- rst century, states in the South and West were annually receiving some $444 billion more in federal funds than those in the Northeast and Midwest. A new economic war between the states seemed to be shaping up. Northeasterners and their allies from the hard-hit heavyindustry region of the Ohio Valley (the "Rustbelt") tried to rally political support with the sarcasticslogan "The North shall rise again." These dramatic shifts of population and wealth further broke the historic grip of the North on the nation's political life. Everyelected occupant of the White House from 1964 to 2008 hailed from the Sunbelt, and from suburban homes to city jobs further facilitated this mass migration. By 1960 one in every four Americans dwelt in suburbia, and a half-century later, more than half the nation's population did. The construction industry boomed in the 1950s and 1960s to satisfy this demand. Pioneered by innovators like the Levitt brothers, whose rst Levittown sprouted on New York's Long Island in the 1940s, builders revolutionized the techniques of home construction. Erecting hundreds or even thousands of dwellings in a single project, specialized crews working from standardized plans laid foundations, while M MN 4% ID 1846 MI T NE 449 sort of 68 hooks O DE W KY so% KS on child-rearing, especlally Dr. Benjamin Sp TN iing lished in 1945, It instructed millions of pare the ensuingdecades in the kind of homelywisdom thatwasonce transmitted naturally ron sondships to parent. In uld postwar neighborhood o hard to sustain. Mobllity could exact human cost in loneliness and isolatlon. Especiallystriking was the growth of tne crescen! unbelta fteen-state area stretching in a smiling trom Virginia through Florida and Texas ation aat population fr 450 WI WY e The CommonSenseBook of Baby and ChildCare. intensive, phenomenally productive big business by the twenty- rst century-and sounded the death knell for many small-scale family farms. representation population grew. lation grOwth and by 1963 had outdistanced New York as the most populous state-a position it still holds in the earlydecades of the twenty- rst century, with more than 38 million people, or more than one out of every tance divided parents from chlldren, and brotte 34.18 Agribusiness Expensive machinery of the sort shown here made most of American agriculture a capital- the region's congressional 845 The convulsive economic changes of the post-1945period shook and shifted the American people,ampli fying the population redistribution set in motion by World War II. As immigrants and westward-trekking pioneers, Americans had always been a people on tne move, but they were astonishingly footlo0se in the postwar years. For some three decades after 1945, residences an average of 30 million people changed every year. Familles especially felt the strain, as OK AT g 034 MS 260% AL GA 1 A States growing faster than national rateof 16659%, 1950-2016 Statesgro slower e of1665%, than nationalrateof1665%. 1950- MAP 34.4 Distribution of Population Increase, 1950-2016 States with gures higher than 166.5 percent were growing faster than the national average between 1950 and 2016. Note that much of the growth was in the "Sunbelt," a loose geographical concept, as some Deep South states had very litle population growth, whereas the mountain and Paci c states were booming. and California. This region increased its Created with Scanner Pro fi fl virtually doubled the average American's standardof living in the postwar quarter-century., WVhenthe link between productivity gains and income growth of the Korean War, productivity increased at an average rate of more than 3 percent per year. Gains in productivity were also enhanced by the rising educational level of the work force. By 1970 nearly 90 percent of the school-age population was enrolled in educational institutions--a dramatic contrast with the opening years of the century, when only half of this age group had attended school. Better educated and better equipped, American workers in 1970 could they had in 1950. Productivity was the key to prosperity. Rising productivity in the 1950s and 1960s fi fi fi in their homes, and engineered a sixfold increase in the country's electricity-generating capacity between 1945 and 1970. Spidery grids of electrical cables carried the pent-up power of oil, gas, coal, and falling water to activate the tools of workers on the factory oor. With the forces of nature increasingly harnessed in their hands, workers chalked up spectacular gains fi fi fl fi their consumption of inexpensive and seemingly inexhaustible oil in the quarter-century after the war. Anticipating a limitless future of low-cost fuels, they ung out endless ribbons of highways, installed air-conditioning fi fi Middle East and kept prices low. Americans doubled fl fl of nature was the key to unleashing economic growth. Cheap ernergy also fed the economic boom. American and European companies controlled the ow of abundant petroleumn from the sandy expanses of the fi fl TheRise of the Sunbelt The Cold War Begins, 1945-1952 reigned supreme over all foreign competitors. The Cold War military budget also nanced much scienti c research and development ("R and D"-hence the name of one of the most famous "think tanks," the Rand Corporation). More than ever before, unlocking the secrets fi fi CHAPTER 34 and electronics--areas in which the United States fi fi 844 The Suburbanites 34.20 Aerial View of the On-ramps to a Typical New Interstate Highway, 1950s rages evckemore vvd heprosoenityof the ea rar araphotographsof sprawing SLCUts Neet ows cf pCk-aike tracthousses,each with 2reny andlawnandhere and here abackyardSwim- irç poO,came SymcozeTecapacityof theeconomy 0ehe te Arencandream"tomalionsoffamilles. nardyyrew. Wel-off city dwellers ing neighbortioocS hadSrrtarzan teter patrs to leaty outyng neighborhoods since Te rireteerth certury But atter 1945 the steady ow tecame a starrcede Thebaby boorn, new highways, gov ermert garrtses for mortgagelending. and favorable t poicesalmade suburbia blossorn. Who were the Americans racing to the new postwar Stuts? Wa veteransled the way in the late 1940s, aided Dy Veterans Adrninistration mortgages that featured tiny Gwn pamerts and low interest rates. The general public Sn tlowed. TheFecderalHousing Adrrinistration (FHA) fered inaured rortgages with low down payments and 2 to 3 percErt irterest rates on thirty year loans. With deals Sko this, t was hardy surprising that Arnerican farnilies focked irto "Leittons," bult by Wiliam and Alfred Levitt, suburban families constantly "on the go culture sorang up with new destinations, like drive-th rants and drive-in movies. Roadside shopping resta: edgedoutdowntownsas places to shop. Mean ters new interstate highway system enabled breadue, the ve fartherand farther from their jobs and still comSo work daily. woI burbanites continued to depend on cities for iobs. though by the 1980s the suburbs themselves wer becoming "edge cities" and important sites of empl ment. Wherever they worked, suburbanites turned the backs on the city and its problems. They fought to main. tain their communities as secluded retreats, independer municipalities with their own taxes, schools, and zonina restrictions designed to keep out public housing and the poor. Even the naming of towns and streets re ected a pastoral ideal. Poplar Terrace and Mountainview Drive were popular street names; East Paterson, New Jersey and other sirnilarcutburtban developrnents. Pecple f at kindsfoundtheirway tosuburbia,heading tor raicgtotoods that varied frorm the posth to the plain. Yet tor al this dversity, the overvternig majority of suburbantos wore vhito ard rmiddo- class. Foaring that the presence was rernamed Elmwood Park in 1973. With a mnajority of Americans iving in suburbs by the 1980s, cities lost ther political clout and much of the tax base that supported crucial public services. As local television news bearmed out stories of "urban crisis" into suburban iving rooms, the economic and social divides between city and suburtb yawned even wider. ye Middie-class African Americans began to move to the suburbs in substantial numbers by the 1980s, but even that migration failed to alter dramatically the racial divide of metropolitan America. Black suburbanites settled in towns like Rolling Oaks outside Miami or Brook Glen near Atlanta-black middle-class towns in white-majority counties. Meanwhile, new immigrants from across the globe turned suburbs from California to Michigan into self-segregated "ethnoburbs." By the beginning of the twenty- rst century, suburbia as a whole was more racially and economically diverse than at midcentury. But old patterns of residential segregation endured, and economic inequality increasingly separated older and poorer "inner-ring" suburbs from newer more middleclass ones. f minoriteswoulddepresspropertyvalues, white homeomors tornetines violently intirmidated prosp0ctive black tuors. rd sorno unscrupulous roaltors ongagod in "Uiok tusting-noving in on0 or two black farnilios, and tajng up the rormaining propor tios of panickod whites vho lod and sold at distrossod pricos. As a rosult, postwar Anerican motropolitan aroas bocarno evor moro starkly wrgatod Only 347 of the 120,000 units of housing built in metropolitan Ptiladelphia botwoon 1946 and 1953 woro open to tlwks ito in tho suburbs brought both opportunity and conformity, Mon tondod to vork in eithor whito-collar jobs or uppor leol blue-collar positions such as forormen. Wornen UAally orked in the homo, 50 much so that suburbia camo to synbolizo the domoslic con nomont that fominists in the 1900s and 1970s docriod in tholr campaign for Women's rights. The houso itsolf bocano more important than over as postwar suburbanitos bult their loisuro lives around telovision, horno inprOVOmont projocts, and barb0cues on the patio, Tho contor of family ifo shittod to the fonced-in backyard, as noighborly city habits of visiting on the front stoop,gatbbingon the sidowalk,and strolling to local storos disappearod. Institutions that had thrived as socal centers in the city-churches, women's clubs, tatemal onganizaions, and tavorns--had a tougher time attracting patrons in tho privalized world of postwar suburbia. The sububa woro a boon to the automobile, as parents junped behind the wheel to shuttle childron, groceri0s, and golf clubs to and fro, Tho second car, once an unhoard-of kuxury, became a practical "necessity for 846 34.19 Drive-in Los Angelcs, Angeles. the th Motherand Modelot A Café re in in Los Model ot All Suburbias 34.21 Buyers Line Up for a Levittown Home, 1951 Mass construction technigues and a New Deal-inspired revolution in home mortgage nancing made rst-tirne honeownere out ot milions of Americans in the post-Worid War l years, fi fi fi fi fl fl Created with Scanner Pro Created with Scanner Pro tyetvef eBheent Created with Scanner Pro