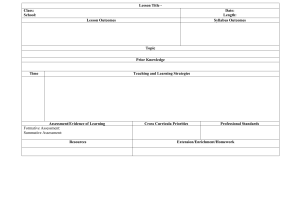

Educational Assessment ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/heda20 Developing a Formative Assessment Protocol to Examine Formative Assessment Practices in the Philippines Louie Cagasan , Esther Care , Pamela Robertson & Rebekah Luo To cite this article: Louie Cagasan , Esther Care , Pamela Robertson & Rebekah Luo (2020): Developing a Formative Assessment Protocol to Examine Formative Assessment Practices in the Philippines, Educational Assessment, DOI: 10.1080/10627197.2020.1766960 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10627197.2020.1766960 Published online: 24 May 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 82 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=heda20 EDUCATIONAL ASSESSMENT https://doi.org/10.1080/10627197.2020.1766960 Developing a Formative Assessment Protocol to Examine Formative Assessment Practices in the Philippines Louie Cagasana, Esther Careb, Pamela Robertsonc, and Rebekah Luoc a University of the Philippines, Quezon City, Philippines; bThe Brookings Institution, Washington, USA; cUniversity of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia ABSTRACT This paper explores ways of capturing teachers’ formative assessment behaviors in Philippine classrooms through an observation tool. Early versions of the tool were structured using the ‘Elicit-Student responseRecognize-Use’ ESRU model. To account for the practices observed in the classroom, the observation tool was resituated to focus on Elicit (E) and Use (U) components. Both cultural and physical factors that characterize the Philippine classroom were considered to help ensure that the observation tool would reflect current practices in classrooms. Data from the tool are envisioned to inform the Philippines’ Department of Education as they embark on the development of teacher competencies in formative assessment. The final version of the tool captures the basic practices in a reliable way. The tool provides a model of increasing competency in formative assessment implementation that can be used to design teacher training modules and for professional development. Introduction The Philippine government embarked on the implementation of a major education reform in the school year 2013. In addition to adding a compulsory pre-Grade 1 year, two final years in the secondary school education system were added, leading to a K – 12, or 13-year education sequence, similar to many countries worldwide. Aligned with this reform has been a reevaluation of assessment practices within Philippine classrooms, with an increased focus on teachers’ use of formative assessment to inform their instructional practices. As part of a program of research to monitor the implementation of these reforms, there was a need to identify current formative assessment practices of a large number of teachers through classroom observations. However, no existing observation tools appropriate to the purpose were found. This paper describes the development of a tool to capture classroom formative assessment practices for use in the Philippines. The paper discusses factors that influence the implementation of formative assessment in Philippine classrooms, as well as the practical considerations of in situ coding teacher practices within a classroom context. Data collected with the tool demonstrate the sequence of increasingly sophisticated formative assessment practices that are demonstrated by teachers in Philippine classrooms. Formative assessment Black and Wiliam (2010) defined assessment as “all activities undertaken by teachers … that provide information to be used as feedback to modify teaching and learning activities” (p. 82). The main purpose is to improve teaching and learning – two interdependent processes. A practice is considered formative assessment if “evidence about student achievement is elicited, interpreted, and CONTACT Esther Care ECare@brookings.edu © 2020 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC The Brookings Institution, Washington, USA 2 L. CAGASAN ET AL. used by teachers, learners, or their peers, to make decisions about the next steps in instruction that are likely to be better, or better founded than the decisions they would have taken in the absence of the evidence that was elicited” (Black & Wiliam, 2009, p. 9). In this definition, instruction is closely linked to the intentional collection of evidence and appropriate use of this information to improve teaching. Several researchers have described the variety of formative assessment practices in terms of its formal and informal nature. For example, Yorke (2003) describes formal formative assessment as something that is undertaken in the context of the curriculum, and constitutes assessment tasks embedded in the curriculum; that is, students are expected to complete a task, and the teacher is expected to assess and provide feedback to the student. Informal formative assessment happens in a spontaneous manner such that as the students take an active role in the learning process, and the teacher responsively and proactively provides feedback to help them move toward the learning goal. Ruiz-Primo and Furtak (2007) take the position that formative assessment can be seen on a continuum from informal to formal approaches, mirroring the same perspective taken on competencies in higher education (Blomeke, Gustafsson, & Shavelson, 2015). They distinguish between formal and informal formative assessment by looking at the processes involved. They describe the formal as an Initiation-Response-Evaluation/Feedback (IRE/F) cycle. With the intention of obtaining evidence of student learning, the teacher initiates activities that have the capacity to demonstrate what the students can do, say, make, or write. The teacher then takes time to interpret the collected information and develops an action plan for the next lesson. They propose that the informal focusses on the conversation level. The process involves an ‘Elicit-Student response-Recognize-Use’ (ESRU) cycle, where the teacher elicits (E) information, the student (S) responds, then the teacher recognizes (R) the student’s response and uses (U) the information to inform teaching strategies. Within the classroom, incomplete cycles (e.g. ES, ESR) are possible; one example would be discussion ending with the student response, at which point the teacher would proceed to elicit information again. Where a cycle is completed, it is assumed that formative assessment has been implemented with the teacher having guided the student toward the learning goal. For the model to be implemented, teachers must be able to modify the lesson as necessary in real time. There are several differences between formal and informal formative assessments, as summarized in Table 1. The formal approach requires teachers to collect all the information before making a decision, and thence to make changes in the next lesson. The approach follows a planned structure of events at the class level considering the time available and curriculum coverage. The informal approach emphasizes the feature of making on-the-spot adjustments to lessons as a result of the teacher identifying challenges to students proceeding through the learning experience. This approach is focused on the student–teacher conversation level, and emphasizes the flexible nature of assessment and giving of “just in time” feedback. Although the notion of formative assessment is broad and can be described in many ways, the formal-informal conceptualization is a useful structure within which to describe classroom practice. In turn, this helps to establish what factors influence teachers’ use of the notion. Both collection and use of information from the students, as well as the links with available time and curriculum coverage, need to be taken into consideration. This is an important issue to consider in the context of classrooms that is subject to the pressures of congested curricula, large class sizes, and inadequate Table 1. Differences between formal and informal formative assessment. Difference Formal Assessment Task Identified prior to the lesson proper Timing of Modification Level and Structure Make changes in subsequent lessons Informal Spontaneous and arise depending on the conversations On-the-spot adjustments of the lesson Planned structure of events at class level; considers time and curriculum Student-teacher conversation level; gives of “just in time” feedback EDUCATIONAL ASSESSMENT 3 physical spaces. There are also cultural considerations when implementing formative assessment models or practices that are developed in and for the Western culture. The education context in the Philippines In the 2008–09 school year in the Philippines, SEAMEO-INNOTECH (2012) reported that 32% of elementary public schools were multigrade; that is, where different grade levels are combined in the one class. Classrooms with more heterogeneous populations than those which contain just one age range pose a particular set of challenges for teachers. In particular, they need to have strategies to identify very diverse functional levels of their students in order to provide groups within the class with capacity-appropriate materials and interventions. A more recent survey of 7,952 multigrade schools was undertaken by DepEd in 2011. The majority of these schools serve students in remote and disadvantaged areas. Overall, the academic achievement of these schools is lower than nonmultigrade, and the resources and facilities less. Although a considerable proportion of these schools (37%) had teacher-student ratios of 1:30, around 17% were at 1:40, and 17% at 1:50 – all with combined classes. Around 60% of teachers surveyed had less than five years’ experience. The timetabling is such that all students receive instruction in the same subject at the same time. For example, students across three grade levels would receive instruction in Mathematics simultaneously. This situation, across such a large proportion of schools, highlights both the need and challenges inherent in the need, for teachers to use formative assessment as an individualized pedagogical strategy. Notwithstanding that 82% of surveyed teachers indicated that they used formative assessment, compared with 65% indicating that they used summative assessment; the types of assessment reported suggest confusion over the meaning of the question: 94% of teachers identified paper and pencil tests as the most frequent form of assessment, as opposed to activity-based tests (70%) and inquiry approaches (28%). The use of such strategies is somewhat inconsistent with understandings of what a comprehensive use of formative assessment strategies implies. It may have been that teacher understandings of the nature of formative assessment were not well informed (Griffin, Care, Cagasan, Vista, & Nava, 2016), accounting for these anomalous findings. Regardless, the large number of students in multi-grade schools in the Philippines requires that methods for implementation of assessment policy are made explicit for these schools. Bailey and Heritage (2008) point out that teachers need access to several competencies in order to implement the formative assessment. These include content knowledge, understanding of metacognition, pedagogical knowledge, understanding of student prior knowledge, and literacy in the assessment. The challenge implied by these requisite competencies for a large proportion of relatively inexperienced teachers in multigrade classrooms, as well as in single-grade classrooms, is complex. Griffin et al. (2016) recorded practices observed in mainstream single-grade Philippine classrooms and found few indications of formative assessment practices. Teachers followed fairly invariant classroom teaching sequences dictated by lesson plans and demonstrated little flexibility in adapting lessons according to student progress. Information about student learning was not widely used to inform instruction; instead, teachers responded to perceived pressure to cover the curriculum. These observations were recorded in single-grade classrooms where the range of student learning experiences is more homogeneous than in multigrade classrooms. Where there is greater heterogeneity in classrooms, it can be presumed that more flexibility and individualized instruction practices are required, so to the degree that multigrade teachers are not provided with training specific to this context and may be implementing the same practices as in single-grade classes; these results are concerning. This state of play needs to be placed in the context of typical challenges to implementation of formative assessment noted by Krumsvik and Ludvigsen (2013) which include high numbers of students in classes, time pressures brought about by dense curricula, lack of interactivity due to teacher classroom management, and resourcing. Winstone and Millward (2012) address the issue of the viability of formative assessment in large classes, although in the higher education sector. They 4 L. CAGASAN ET AL. provided examples of activities they used in large classes such as the use of a short quiz and additional learning tasks. The examples amounted to recall of learning, as well as active learning strategies rather than the provision of formative feedback, highlighting the point that it is difficult to implement such practices in large classes even when explicitly attempting to do so. Large classes that accommodate up to 60 students are common in the Philippines and China (Watkins, 2008; DepEd Order #40, s. 2008). Watkins (2008) points out the paucity of research with large class sizes. Clarke et al. (2006) identify large class size as a constraint to teaching and learning, and identify existing classroom practices in the Philippines as a response to this constraint. They hypothesize however that the limited repertoire of teachers’ alternative strategies is the real hindrance to student competence. Formative assessment and culture In classroom dialogs, there are three stakeholders involved. These are the learner, the co-learner or peer, and the teacher. These individuals interact with each other and play different roles in “identifying where the learners are in their learning,” “where they are going,” and “how to get there” (Wiliam & Thompson, 2008). Table 2 displays these aspects of formative assessment. Although this model of formative assessment looks modest, in the context of the culture in which a classroom operates, implementation of strategies may not be straightforward. Hofstede (1986) proposed four cultural factors that influence teaching and learning. These include: Individualism-collectivism This concept pertains to the degree of cohesiveness and identity of individuals in a society. On the individualist pole, the focus is more on personal interest and individuals are loosely tied with the people around them. On the collectivist pole, the focus is on the group. Power distance This concept refers to perceptions around equality-inequality and power. With large power distance, less powerful people are considered less equal, and there are presumptions of different behaviors being appropriate for those at different levels of power. With small power distance, there is a greater presumption of equality, with consequences for what behaviors are acceptable within a group or society. Uncertainty avoidance This concept centers on ways of handling ambiguous situations. Individuals with high uncertainty avoidance will prefer structured and predictable conditions that are commonly manifested by strict adherence to rules and guidelines. Those low in this cultural value will be more accepting of ambiguity and more comfortable with less structure. Masculinity This concept pertains to a characterization of culture as subject to two competing social roles, which are commonly associated with the two biological sexes. Culture characterized as masculine is Table 2. Aspects of formative assessment, derived from Wiliam and Thompson (2008). Where the learner is going Teacher Clarifies and shares learning intentions and criteria for success Peer Understands learning intentions and criteria for success Learner Understands learning intentions and criteria for success Where the learner is right now How to get there Engineers effective discussions, tasks and Provides feedback that activities that elicit evidence of learning moves learners forward Activates students as learning resources for one another Activates students as ownersof their own learning EDUCATIONAL ASSESSMENT 5 described as competitive and assertive, while feminine is viewed as more caring and valuing of interpersonal relations. Teacher/student and student/student interactions may vary depending on the level of these cultural dimensions. Table 3 plots possible differences in terms of consequence for classroom interactions against cultural dimensions. The table contents are re-structured and adapted from Hofstede (1986) and Wiliam and Thompson (2008) to demonstrate the possible interactions dependent on cultural context. It is evident that culture may well interact with formative assessment practices. In the world of summative assessment with its examinations and classroom tests, the cultural impact may not be evident – notwithstanding claims in some countries that they are self-consciously examinationoriented (Berry, 2011). In the world of formative assessment, differences across countries, as well as across classrooms, become more evident. Al-Wassia, Hamed, Al-Wassia, Alafari, and Jamjoom (2015) point out that formative assessment drives student learning and teacher instruction, but that there is little published about its use in developing countries. In their study of attitudes toward formative assessment among teachers and students in a medical faculty, they identified four categories of challenges to formative assessment implementation – political and strategic, economic and resources, social and religious, and technical/ development. They found that 33% of faculty and 43% of students believed that there were social and religious challenges to the practice. The questionnaire items contributing most to this finding addressed power differences that meant students would not be able to debate issues with faculty. There were also concerns that the interaction between opposite-sex students and faculty was counter to religious rules. Apart from these concerns, issues of teacher pedagogical expertise were raised. Berry (2011) discussed the difficulties faced when attempting to implement formative assessment in an examination culture, making the claim that the Chinese history dating back to the 11th century Table 3. Differences in classroom interaction. Actors in Formative Assessment Teacher Peer Learner Individualist/Small Power Distance/Low Uncertainty Avoidance Societies Collectivist/Large Power Distance/High Uncertainty Avoidance Societies T1. Teacher should respect the independence of his/ her students. B T2. Students are allowed to contradict or criticize teacher. B T3. Teacher expects students to initiate communication B T4. Teachers are allowed to say “I don’t know”. C T5. Teachers interpret intellectual disagreement as a stimulating exercise.C P1. Stress on impersonal “truth” which can in principle be obtained from any competent person. B L1. Students may speak up spontaneously in the class. B L2. Individuals will speak up in large groups. A L3. Teacher expects students to find their own paths. T1. Teacher merits the respect of his/her students. B T2. Teacher is never contradicted nor publicly criticized. B T3. Students expect teacher to initiate communication. B T4. Teachers are expected to have all the answers. C T5. Teachers interpret intellectual disagreement as personal disloyalty. C B B L4. Students expect to learn how to learn. A L5. Students feel comfortable in unstructured learning situations: vague objectives, broad assignments, not timetables. C Environment/ A1. Confrontation in learning situations can be Assumptions/ salutary; conflicts can be brought into the open. A A2. Face-consciousness is weak. Values A3. Effectiveness of learning related to amount of two-way communication in class. B P1. Stress on personal “wisdom” which is transferred in the relationship with a particular teacher (guru). B L1. Students speak up in class only when invited by the teacher. B L2. Individuals will only speak up in small groups. A L3. Students expect teacher to outline paths to follow. L4. Students expect to learn how to do. A L5. Students feel comfortable in structured learning situations: precise objectives, detailed assignments, strict timetables. C A1. Formal harmony in learning situations should be maintained at all times. A A2. Neither the teacher nor any student should ever be made to lose face. A A3. Effectiveness of learning related to excellence of the teacher. B Adapted from Hofstede’s (1986) cultural dimensions A = Collectivism-Individualism, B = Power Distance, and C = Uncertainty Avoidance 6 L. CAGASAN ET AL. established a perception that summative assessments are the natural means of establishing future pathways, and that the influence of the British in Hong Kong was aligned with this perception. Attempts in the last decade of the 20th century to implement assessment for learning met with resistance from parents due to this historical and cultural context. The government renewed these efforts from 2001 onward but continued to find schools, parents, and students skeptical about school-based assessment and assessment for learning approaches. Brown, Kennedy, Fok, Chan, and Yu (2009) analyzed Hong Kong teacher data to show that the teachers saw the use of assessment for learning primarily as accountability measures, maintaining strong support for an examinations culture. Brown et al. suggest that these findings mirror the Confucian values long established in Chinese societies, with teachers responding to parents’ requirements that students are continually challenged. Evidence for such challenge includes the regular summative assessment. The degree to which the resistance to formative assessment in Hong Kong is associated with culture is highlighted by Carless (2005) who notes that assessment has historically been seen as measurement, rather than as an aid to learning. Assessment, learning, and teaching have been seen as quite independent aspects of education. Of interest in exploring the degree to which assessment practices might be associated with historical practices rather than primarily cultural values, Ratnam-Lim and Tan (2015) describe the “meritocracy” principle underpinning the Singaporean system. They propose that an examinationsbased assessment approach has had primacy due to the perception that this ensures fairness in progression. This view represents a socio-cultural, rather than cultural, perspective on difficulties experienced in introducing formative assessment into the education system, notwithstanding the support for this from the government authorities. Ghazarian and Youhne (2015) also focus on the implications of the Confucian tradition for assessment in the Korean classroom. They implicitly adopt the perspective that formative assessment practices go counter to traditions of respect and obedience, and draw attention to the concept of power distance. In cultures where small differences in power are assumed between teachers and students, there is an implicit assumption that formative assessment will be more acceptable. In much of the literature, there appears to be an equating of discussion between teacher and student within the teaching and learning process with lack of respect. Whether this assumption is reasonable does not appear to have been contested. Reflecting characterizations of teacher–student interaction styles across cultures, Liem, Nair, Bernardo, and Prasetya (2008) note clear differences in classroom interaction between the Indonesian and Australian higher education contexts. They refer to the early work of Hofstede (1986) and the collectivist–individualist dichotomy as well as power distance. Liem et al. hypothesized that Australian, Filipino, Singaporean, and Indonesian students would endorse these two dimensions differently, and of relevance to this study, that Filipinos – together with Singaporeans and Indonesians – would prove more deferential to teachers and be more collaborative with peers than Australians. Liem et al. were interested in the actual values that might account for the hypothesized dimension differences and studied how the former might impact on classroom social interactions of Year 10 students in schools in Sydney, Singapore, Manila, and Jakarta. Although most differences across the groups were consistent with the collectivist–individualist dichotomy, there were some exceptions for classroom social interactions. For example, Filipino and Singaporean students showed a higher tendency to conform to their classmates than Australians. These different perspectives on barriers to implementation of formative assessment in several Asian cultures present a complex picture of the factors that might impact on how the assessment practices can be implemented in classrooms. Cultural issues may be more pivotal for the implementation of informal rather than formal formative assessment strategies. For example, a common medium for informal formative assessment is through discussions inside the classroom. This may function effectively in individualistic societies with weak power distance due to the perception that students and teachers are equal participants in the process, notwithstanding that they have different roles. Depending on individual school and teacher, of course, there tends to be a culture in which EDUCATIONAL ASSESSMENT 7 students can discuss and ask a wide range of questions of their teachers, and where initiative is encouraged. However, in collectivist societies with large power distance, students may hesitate to converse with the teacher due to conventions associated with formal respect, and based on the inequality of power. This may restrict discussion and favor teacher-directed dialogs. Citing the work of Carless (2011), Black (2015) proposed that it is difficult to establish oral dialogs when students are expected to be passive and obedient. Rationale for this study As discussed above, Griffin et al. (2016) were able to identify very few formative assessment practices in mainstream single grade classrooms in the Philippines. However, that study relied on lesson narratives from 61 classrooms, which were qualitative descriptions of the flow of the class, to analyze and identify the extent and nature of formative assessment practices in the classroom. That method of investigation is unrealistic if the goal is to assess or “measure” formative assessment practice at a larger scale. A more efficient method is needed. The aim of this study was to develop an observation instrument that: ● ● ● ● can be used at a large scale without the need for video recording; can provide a reliable measure of formative assessment practice; requires minimum training of observers; takes into account cultural considerations relevant to the Philippine classrooms. Method Tool development Phase 1 An observation tool was developed to enable in situ coding of informal formative assessment practice within classrooms. The initial intent was to develop a tool based on the ESRU cycles of RuizPrimo and Furtak (2007) who used assessment conversations as an approach to explore teachers’ questioning practices in the context of scientific inquiry teaching in the United States. They described assessment conversations as consisting of four-step cycles, where the teacher elicits (E) a question, the student responds (S), the teacher recognizes (R) the student response, and then uses (U) the information collected to improve student learning. The aim of the tool was to capture the frequencies of both complete and incomplete cycles of these four components and, where possible, the nature of the ESRU components such as the types of eliciting (E) techniques or student responses (S). Given that the Philippines is perceived as having large power distance (Hofstede, 1986), examples of these teacher-orchestrated ‘elicit’ (E) and ‘student response’ (S) are that: a teacher would ask the student to read visuals posted on the board; then students would read it as instructed; or, a teacher would tell a student to stand up, read an item from a set of questions posted on the board, and ask the student to provide the correct answer. Questioning followed by class response is another common pattern and was therefore included in the coding system. Clarke, Xu, and Wan (2013) would call this student action a choral response, which is also common in Shanghai and Seoul. The tool consisted of a template and a series of codes to be used during a lesson to record the nature of verbal interactions between the teacher and students. Preliminary checking of the tool was undertaken using a video of class sessions. This was also informed by back-checking against the observation data collected in Griffin et al. (2016). Video footage was used for observer training. The template and codes were then piloted in a range of classrooms in public schools in metropolitan Manila. Eight lessons were observed in both Mathematics and English classes in Grades 2, 5, and 8. All lessons were recorded simultaneously by two observers to allow for the identification of codes or 8 L. CAGASAN ET AL. behaviors that defied reliable coding. For example, where a particular coding was systematically not mirrored across two observers, this would indicate a problem with distinguishing the particular behavior or with interpreting it within the coding system. The research team identified several issues with this initial version of the observation tool. First, it was too challenging for observers to make certain coding decisions on the spot. This led to a low observer agreement. Second, the parameters and definitions of the ESRU components were insufficient to enable reliable recording and coding. The overlapping ESRU components and coding categories, in particular, warranted a major overhaul to the tool. Third, the data collected using the ESRU tool required a substantial amount of post-observation decoding and analysis. This would not be suitable for use at large scale. Phase 2 Tool development was re-situated, acknowledging the learnings from the Phase 1 observations and the need for an instrument that can be used at large scale. As specified in DepEd Order Number 8 (2015), formative assessment is described as a process that involves “teachers using evidence about what learners know and can do to inform and improve their teaching” (p. 2). Formative assessment can occur at any time during the teaching and learning process, and involves providing students with feedback. The two main ideas about formative assessment that are consistently mentioned in the literature and in DepEd Order Number 8 are that information about student learning is elicited and is used by teachers, peers, or learners themselves. Consequently, the focus of the observation tool development was narrowed to how teachers elicit behavior and use the elicited information to inform and improve student learning. The observation tool, the Classroom Observation of Formative Assessment (COFA) was developed to focus on Elicit (E) and Use (U) components. The two main capabilities are ‘elicit evidence of student learning to determine what students know and can do’ and ‘use evidence of student learning to move toward the learning goal.’ Figure 1 shows the COFA. COFA consists of seven statements of indicative behaviors, each focusing on an aspect that is representative of either eliciting or using informal formative assessment. Associated with each indicative behavior is a set of practices. Using COFA, observers can indicate whether the indicative behaviors are present during the class. When a particular type of formative assessment behavior is Figure 1. Classroom observation of formative assessment (COFA). EDUCATIONAL ASSESSMENT 9 observed during a lesson, observers are required to indicate the presence of this practice using a ‘✔’ symbol in the third column. Observers were not required to make counts of each behavior, only to indicate whether it was observed during the lesson. In the last column of the tool, observers can note down evidence for their ratings or examples of practices. Note that these notes were not included in any subsequent analysis. Capability 1: elicit evidence of student learning This capability is comprised of three indicative behaviors (Figure 1). (1) Teacher elicits response/s from individuals to determine what student/s know and can do (focus on depth of evidence gathered) (2) Teacher elicits response/s from the class to determine what student/s know and can do (focus on the generality of evidence gathered) (3) Teacher uses techniques to elicit student responses (focus on flexibility of techniques) The first two Indicative Behaviors are derived from the Griffin et al. (2016) and Phase 1 classroom observations. For both behaviors, a distinction is made between two types of student data: the individual and the class. Indicative Behavior 1.1 is divided into three practices that are distinguished according to the purpose of the data collection – matching student answer against the correct response, identifying the method or process used, and understanding the student mental model. Indicative Behavior 1.2 can be classified as a context-based factor as this may be particular to Philippine setting. Its practices involve collecting data from the class; however, inferences about student learning cannot be linked back to the individual students. It is a more general gauge of the class as a whole. An example of this would be the entire class responding in unison to the question of the teacher. The second practice includes strategies that elicit student data from the entire class but with information being able to be linked back to individual students. One common note in the observations is the use of “drill boards” (small whiteboard or illustration board) on which the students write their answers to teacher’s question. Students raise their boards so that the teacher can scan across the responses from all students. Indicative Behavior 1.3 under the Elicit component centers on the variation on the method and flexibility. The first practice involves teachers having planned the eliciting method (or assessment tasks) and maintaining this plan. The second practice entails teachers making adjustments and using different eliciting techniques depending on the situation. These were identified through a comparison of the teacher’s lesson plan and what was actually implemented in the lesson. Capability 2: use evidence of student learning This capability is comprised of four indicative behaviors (Figure 1). (1) (2) (3) (4) Teacher gives feedback based on student response Teacher uses the information to inform instructional decisions Peer gives feedback Students self-assess (at group or individual level) Indicative Behavior 2.1 has four practices associated with it that range from acknowledging that the response is correct/incorrect through to giving feedback focused on supporting students to evaluate their own process (see Figure 1, practices 2.1.1 to 2.1.4). This Indicative Behavior combines aspects of the Recognize and Use components of the ESRU model and the practices that describe quality in feedback are consistent with those discussed by Hattie and Timperley (2007). Indicative Behavior 2.2 captures how the needs of the students are addressed. The first practice (2.2.1) indicates that the teacher is able to acknowledge the gap between the lesson and student level, but the teacher is not able to address it fully. The second practice (2.2.2) shows that the subsequent 10 L. CAGASAN ET AL. teaching actions are matched with the level at which students are operating. During a lesson, observers made ratings based on teachers’ use of information from students in retaining or modifying the lesson plan to match students’ level. Lesson plans were supplied to the researchers so that any deviations from the plan could be identified. It is important to note observers’ ratings reflect what occurred within a lesson and not across lessons. The last two Indicative Behaviors (“peer gives feedback” and “students self-assess”) are supported by the DepEd policy documentation and formative assessment literature. Field trial A field trial was conducted to evaluate the properties of COFA. In particular, the aim of the trial was to check the reliability of the tool and its ability to capture the range of formative assessment practices present in Philippine classrooms. Participants Participants for the field trial involved two groups, the observers and teachers. The observers were five individuals, all of whom had a background in education and/or research. Observers were provided with a three-hour training session which consisted of a brief explanation of the study and the tool, a session of trying out the instrument using a video, and a post discussion of the entire experience that involves quality and assurance checking to standardize coding procedures. The observed teachers (N = 28) taught at Grades 2, 5 and 8, in DepEd schools in National Capital Region and Northern Mindanao. Lesson observations were then undertaken of English and Mathematics lessons, as shown in Table 4. Each lesson was coded by two observers. One (constant) observer was present during all lessons (N = 28) and an additional observer for each lesson was one from the pool of four trained observers. The constant observer was involved in the development of the tool and thus was most familiar with the tool and observation process. He was present at all classroom observations and was paired with another observer to help explore inter-rater reliability. Analysis Twenty-eight classes were each rated by two observers. The rationale for having two observers was to undertake a comparison of the ratings and establish the inter-rater reliability. The percent of times the two observers agreed on the identification of a practice as present or absent was calculated. Guttman analysis (Griffin, Robertson, & Hutchinson, 2014; Guttman,1950) was used to determine the suitability of COFA to measure the formative assessment construct. The benefit of a Guttman analysis is that it can identify (i) the ability of an item to discriminate between participants with different levels of abilities; and (ii) the ordering of items based on their difficulty. The information indicates how well the items go together and may provide evidence on how the items represent the degree of sophistication or behavioral manifestation of the construct. Guttman analysis can be applied to datasets that are too small for item response theory to be applied. The hypothesis was that some practices would represent more sophisticated or expert practices than others. A Guttman chart is produced based on the presence–absence data from each observer. First, a table of ratings is created where the rows represent each observed lesson, and the columns are each practice. A total across the columns for each row provides a score which indicates the number of observed practices. A column total provides a score that represents the number of times a particular practice was observed. The table Table 4. Lesson observations for field trial. Lesson Observations Math English Total Grade 2 6 5 11 Grade 5 5 6 11 Grade 8 3 3 6 Total 14 14 28 EDUCATIONAL ASSESSMENT 11 can be sorted both by rows and by columns so that the rows are ordered, with the lessons involving the most proficient formative assessment practices appearing at the top of the chart and the lessons involving the least proficient formative assessment practices appearing at the bottom of the chart. Similarly, the columns are ordered so that the practices that are observed in the most lessons, which are interpreted as easiest to achieve, appear at the left of the chart and those that are observed in fewest lessons, which are interpreted as most difficult to achieve, appear at the right. The order of the columns and the totals for each indicate whether the relative difficulties of practices observed were suitable to capture the range of practices present within the sample of lessons observed. It allows the suitability of the tool to assess the range of proficiencies within the sample to be established. The pattern of ones and zeros within the chart provides a visual representation which indicates qualitatively the degree to which the items go together and how the items represent the construct. Results Inter-rater consistency In terms of observer agreement with the constant or master observer, there was agreement on the presence-absence of each one 90% of occasions. Across four observer pairs, the spread of agreement was from 78% to 96% as shown in Table 5. Guttman chart A Guttman chart was produced based on presence-absence data as shown in Figure 2. This was created by collapsing the data from the two observers. In the Guttman chart, a formative assessment practice is marked as present or “1” if both observers noted it; the same consistency criterion applies for practices not observed or “0”. When observers do not agree, a practice is coded as “0”. The top two rows of Figure 2 show the cases with the most proficient formative assessment practice. The first Mathematics teacher (case C01) scored a total of 12 out of 15. Presence of ‘1ʹ in all the columns except 1.2.2, 2.3.1, and 2.4.1 means that this teacher displayed all of the other 12 practices, but was not observed identifying individual student responses from whole-class responses, nor was any selfassessment or peer assessment observed for this lesson. At the bottom of the Guttman chart, four English teachers (case C25 to C28) scored 5 out of 15 as can be seen by the number of 1’s in those rows. The observations of these teachers resulted in the fewest formative assessment practices observed. The Guttman chart also identifies the easiest practices in the instrument as these are present in all observed lessons (i.e., a 1 on 1.1.1 and 2.1.1), whereas the most difficult practices were not observed in any of the lessons (i.e., 2.3.1 and 2.4.1). This order gives insights on the possible levels of sophistication. The spread of coded behaviors between these extremes also provides preliminary evidence that the instrument was suitable for capturing the range of formative assessment teacher actions observed in all 28 lessons. The frequency of demonstration of practices is indicative of the ease or difficulty of the practices relative to the other practices within the instrument. Only one practice does not fit well with the Table 5. Inter-rater consistency. Coders A and B A and C A and D A and E TOTAL N observations 18 6 2 2 28 Presence–absence data are based on 13 individual judgments. Proportion of Agreement 0.92 0.78 0.96 0.92 0.90 12 L. CAGASAN ET AL. Figure 2. Guttman chart based on presence-absence data. pattern. Indicative Behavior 1.2.2 “Teacher can identify individual responses from all class members” has an irregular pattern across the Guttman chart, signifying that teachers who generally scored higher on the tool as a whole did not exhibit this behavior more frequently than teachers who had a lower overall score. For example, a teacher who had an overall score of 11 did not exhibit behavior 1.2.2, but several teachers who scored 6 overall did. This can indicate that the behavior is not part of the same construct as the other behaviors that the description is poorly worded, or that there were difficulties in collecting accurate data. The final point of interest from the Guttman chart is the spread of difficulties from each of the capabilities being assessed, eliciting, and using evidence, with practices from each of the capabilities being mixed across the chart. This shows that the use of more sophisticated methods of eliciting and using evidence develop together. In contrast, unobserved Indicative Behaviors (2.3 and 2.4) were within the capability related to the use of evidence, indicating that these are the skills least likely to be developed by teachers. Note that these two practices are related to self and peer assessments which are influenced by culture and context, and may sometimes lie beyond teacher control. EDUCATIONAL ASSESSMENT 13 The sample for these data contained both English and Mathematics lessons. The ordering of the rows in the chart shows the relative sophistication of formative assessment behaviors that were observed. Those rows closer to the top of the chart are for lessons in which more sophisticated formative assessment practices were present and vice versa. It can be seen from the distribution of subjects from top to the bottom of the chart, that the lower and middle sections of the chart contain a mixture of both Mathematics and English lessons. However, the top of the chart contains mainly Mathematics lessons. This may indicate that Mathematics lessons provide greater opportunity for demonstration of sophisticated practices than lessons in other subjects; that the instrument is not as good at capturing sophisticated practices within English lessons; or that of the sample of teachers observed, the Mathematics teachers happened to be more sophisticated in their use of strategies. Further investigation is required to determine the cause of this finding. Levels of formative assessment practice Based on consistent patterns in the Guttman chart, these practices can be summarized into four levels of formative assessment. The increasing sophistication of strategies is displayed in Table 6. The levels of practice were determined by analyzing how the items go together quantitatively and qualitatively. Divisions between the levels are generally determined by the changes in the patterns within the chart in Figure 2 and a significant jump in total score from one practice to another (see bottom row of Figure 2). For example, the sharp change in the number of lessons in which the higher level practices were observed determined the placement of the cutpoint between those levels. Most of the classes observed were operating in Levels 1 and 2. There were isolated cases observed where teachers demonstrate awareness of students not progressing in alignment with the prescribed curriculum and consequently adapt their actual teaching (Level 3). No teacher was observed implementing practices at Level 4. Although the tool is based on the “elicit” and “use” components, sophisticated forms of eliciting would involve using student evidence, and having an understanding of the mental model of the student. The asking of good questions needs to target the student perspective. The four levels capture Table 6. Levels of formative assessment practices and sequence of strategies. Characterization of set of strategies Strategies from most to least frequently observed Level 1: Teaches at class level and attends only to prescribed lesson delivery; provides direction at times for the students to complete tasks Teacher elicits responses to match a pre-conceived “correct” response. Data collected can only be interpreted at class level (e.g. chants, self-report quiz totals) Teacher has main mode/s of eliciting responses Teacher indicates if response is correct/incorrect Teacher gives information specific to the task or product Level 2: Acknowledges discrepancies between intended lesson Teacher attempts to bridge or partially bridges the gap and student responses; provides additional information to between the lesson and the student level students Teacher elicits responses to identify the method or process used by the student/s Level 3: Acknowledges and responds to student progress; Teacher is flexible and adapts modes to the situation adjusts teaching strategies and provides feedback about Teacher matches lesson with elicited evidence of student level process and conceptual understanding to address identified Teacher gives feedback about the main process used to discrepancy between the intended lesson and student understand/perform the task responses Teacher elicits responses to identify the mental model/ conceptual understanding of the student/s Level 4: Teaches students how to become evaluators of their Teacher gives feedback focused at supporting the student to own learning processes and to support the evaluation evaluate their own process processes of peers Teacher provides opportunities for students to give each other feedback (beyond just correcting responses or giving marks) Teacher provides opportunities for students to assess themselves (beyond just correcting responses or giving marks) The item, “Teacher can identify individual responses from all class members” is omitted from this analysis due to its poor fit. 14 L. CAGASAN ET AL. Table 7. Possible teacher response based on the FA levels. FA Scenario 1: Student gives an incorrect Levels response Level 1 Teacher says to the student incorrect; gives details related to the problem; and calls another student to answer. Level 2 Teacher calls another student then reminds the class about the concept behind the task; at times the teacher would try to identify the process used by the student. Teacher probes further to understand the level at which the student is operating and tries to address the misconceptions. Level 3 Scenario 2: No student answers the question Scenario 3: Student gives an incomplete response Teacher answers the question; gives Teacher calls another student to more information about it; and moves complete the response; gives clues to the next task. on how to answer it; then moves to the next task. Teacher answers the question and Teacher calls another student and reminds the students how to get to explains the things the student the right answer missed in the process. Teacher changes the question and tries to understand the reason why students can’t answer it. After that the teacher addresses the identified gap. Teacher keeps the conversation going and tries to identify why the student couldn’t give the complete answer. The teacher then addresses any misconception. and describe the increasing sophistication of formative assessment practice. The notable source of variation across the four levels of formative assessment practice is the degree to which student data are used to inform instruction. To give a snapshot of the specific use of student data across the levels in the event of incorrect, incomplete, or null student response, three scenarios are displayed in Table 7. These scenarios provide an illustration of the specific actions of teachers operating across the first three levels of formative assessment practices. No teachers were observed at Level 4 competence which therefore remains hypothesized. Discussion The purpose of the observation tool is to obtain information about patterns of practice which can be used to inform teacher and system in the context of improving pedagogical practices. The initial versions of the instrument were strictly based on the Elicit-Student Response-Recognize-Use (ESRU) model and had conversation patterns as the unit of analysis. However, the Phase 1 pilot of the tool identified some challenges and the need to better take into account the realities of classroom practice. COFA captures the general picture of the eliciting techniques and the use of studentgenerated data. It provides information about the range of practices that teachers are employing. Although it lacks detail of the specific Eliciting-Using techniques, the particular functioning level signals where teachers need support. This research identified four levels of increasing competence in formative assessment practices. This provides a framework for teachers to evaluate their current practice and determine where they should be heading. The progression gives them a means to calibrate their pedagogy and philosophy as each level reflects a more sophisticated understanding of how teaching and learning should happen. The observed teachers for this study are mostly assessed to be in Levels 1 and 2. This can be explained in part by the cultural context as characterized by its particular power distance, and focus on the group rather than the individual. Beyond this perspective, it is reasonable to assume that the pressure of curriculum delivery and large class sizes make it difficult to respond to individual student need. Policy implementation: formal and informal formative assessment Filipino teachers are more familiar with conceptualizations of formative assessment as a formal process. For example, if they note a need for change in instruction, this is more likely to be implemented in the next class. The stimulus for moving onto the next topic is the completion of a short quiz at the end of each class. Although DepEd has issued an order at the policy level that EDUCATIONAL ASSESSMENT 15 formative assessment must be implemented in the classrooms, implementation of that policy is challenging. It is important that there are rich descriptions of what these expected formative assessment practices look like and professional development/other support for teachers in order to make changes to classroom practices. In particular, all forms of assessment are typically seen as formal, so to shift teachers’ perception of formative assessment to its identity as an instructional strategy is challenging. The observation tool together with its levels of formative assessment practice offers a structure that could be used to guide teachers to elicit information from the students and use this information to help the students move toward the learning goal. Training documentation or video exemplars could be developed to provide guidelines on how to implement informal formative assessment strategies, with examples of different techniques for eliciting and use of student responses. Such guidelines need to be developed in the context of diverse learners (particularly for multigrade) and large class sizes. There are noteworthy Elicit patterns observed in the observations data. Although it is anecdotally observed that students rarely ask questions of their teachers, COFA’s design does not allow for systematic collection of Student response data. However, as seen in the Guttman chart, the capacity of teachers to identify individual student responses is anomalous. This may be an artifact either of the capabilities of the teachers observed or of the reluctance of students to initiate responses that could be acted on by the teachers. Hence, the issue may be a function both of teacher capability and student “opportunity.” Power distance is a possible explanation for the latter with students occupying a lower status role than the teacher in the Philippine classroom. The consequence of this is that the student does not see it as appropriate to question the teacher, which limits the opportunities for the teacher to provide the students with more insight into what is being learnt. There are two issues that arise from the findings. One of these is cultural and the other physical. First, educators need to identify methods to engage students in the classroom which are not in conflict with the culture; this means that structures within which both teachers and students feel safe need to be instituted so that students can ask questions and express opinions. Current classroom structures are clearly defined but do not permit much individualization. The solution lies in teachers’ hands through their encouragement of student initiative. It is important for teachers to engineer environments that facilitate open communication and activate students to be responsible agents of their learning. Without this step, teachers are less likely to be able to collect the information they need to address student needs. Second, the size of classes needs to be factored into how facilitating structures can be implemented. The use of group work may be an obvious solution, taking into consideration Liem et al.’s (2008) findings on the positive orientation toward collaboration among Filipino students. However, the facilitation of group work also needs to take into account physical space in the classroom – often at a premium in the Philippines. The tool used for data capture to describe formative assessment was developed to reflect teacher behaviors. In addition, the results reflect teacher baseline behaviors, prior to large-scale professional development activities intended to equip teachers to adopt stronger formative assessment approaches. The degree to which the tool has the capacity to capture more sophisticated behaviors than is the pattern from this small set of observations remains to be established. It is possible that the opportunity for formative assessment practices may vary according to the subjects, and even the topics, which are the focus of lessons. The slight differences between practices observed across the Mathematics and English classes found in this study need to be explored in depth with multiple observations per teacher. Although large-scale use of the tool might clarify if there are stable differences across disciplines, more at issue would be the factors that account for such differences. Such factors could include the manner in which curricula for different disciplines are written, and the style of textbooks that support the curricula. In other words, the way a subject is conceptualized, and the way support materials are designed, will set parameters around the teaching and learning environment. These parameters may circumscribe the autonomy of the teacher to adjust the teaching style. 16 L. CAGASAN ET AL. Conclusion The combination of the recent adoption of formative assessment approaches to pedagogy, cultural factors in the Philippines which influence teacher–student interactions, and large class sizes, present challenges to effective implementation of formative assessment strategies. Notwithstanding, there are clear patterns in implementation demonstrated by the use of a tool adapted to the Philippine classroom. These patterns provide a framework in which particular strategies can be seen to be sequenced from more common, and presumably easier to implement; to those which are seen less frequently, and imply more difficulty in implementation. The findings are clear in identifying a developmental sequence in these practices, and therefore provide a useful framework for the development of teacher training modules. The Classroom Observation of Formative Assessment tool provides a facility for the collection of formative assessment practices in a way that describes increasing levels of formative assessment capacity. These levels, in turn, provide a resource that can be used for the professional development of teachers in this set of instructional strategies. References Al-Wassia, R., Hamed, O., Al-Wassia, H., Alafari, R., & Jamjoom, R. (2015). Cultural challenges to implementation of formative assessment in Saudi Arabia: An exploratory study. Medical Teacher, 37(1), S9–S19. doi:10.3109/ 0142159X.2015.1006601 Bailey, A. L., & Heritage, M. (2008). Formative assessment for literacy, Grades K-6: Building reading and academic language skills across the curriculum. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage/Corwin Press. Berry, R. (2011). Assessment trends in Hong Kong: Seeking to establish formative assessment in an examination culture. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 18(2), 199–211. Black, P. (2015). Formative assessment – An optimistic but incomplete vision. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 22, 161–177. Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Accountability, 21(1), 5–31. doi:10.1007/s11092-008-9068-5 Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2010). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 92(1), 81–90. doi:10.1177/003172171009200119 Blömeke, S., Gustafsson, J., & Shavelson, R. J. (2015). Beyond dichotomies: Competence viewed as a continuum. Zeitschrift Für Psychologie, 223(1), 3–13. doi:10.1027/2151-2604/a000194 Brown, G. T. L., Kennedy, K. J., Fok, P. K., Chan, J. K. S., & Yu, W. M. (2009). Assessment for student improvement: Understanding Hong Kong teachers’ conceptions and practices of assessment. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 16(3), 347–363. Carless, D. (2005). Prospects for the implementation of assessment for learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 12(1), 39–54. Carless, D. (2011). From testing to productive student learning: Implementing formative assessment in Confucianheritage settings. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. Clarke, D. J., Shimizu, Y., Ulep, S. A., Gallos, F. L., Sethole, G., Adler, J., & Vithal, R. (2006). Cultural Diversity and the Learner’s Perspective: Attending to Voice and Context. Chapter 3-3. In F. K. S. Leung, K.-D. Graf, & F. J. LopezReal (Eds.), Mathematics Education in Different Cultural Traditions – A Comparative Study of East Asia and the West: The 13th ICMI Study (pp. 353–380). New York, USA: Springer. Clarke, D. J., Xu, L., & Wan, M. E. V. (2013). Choral response as a significant form of verbal response in Mathematics classrooms in seven countries. In A. M. Lindmeier & A. Heinze (Eds.). Proceedings of the 37th Conference of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education, Vol. 2, Kiel, Germany: PME, pp. 201–208. DepEd (2008). General Guidelines for the Opening of Classes. (DepEd Order No. 40, s. 2008). Manila, The Philippines: Department of Education, Republic of The Philippines. DepEd (2015). Policy Guidelines on Classroom Assessment for the K to 12 Basic Education Program (DepEd Order No. 8, s. 2015). Manila, The Philippines: Department of Education, Republic of the Philippines. Ghazarian, P. G., & Youhne, M. S. (2015). Exploring Intercultural Pedagogy: Evidence From International Faculty in South Korean Higher Education. Journal of Studies in International Education, 19(5), 476–490. doi:10.1177/ 1028315315596580 Griffin, P., Robertson, P., & Hutchinson, D. (2014). Modified Guttman analysis. In P. Griffin (Ed..), Assessment for Teaching. Port Melbourne, VIC, Australia: Cambridge University Press. EDUCATIONAL ASSESSMENT 17 Griffin, P., Care, E., Cagasan, L., Vista, A., & Nava, F. (2016). Formative assessment in the Philippines. In D. Laveault & L. Allal (Eds.), Assessment for Learning: Meeting the Challenge (pp. 75–92). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. Guttman, L. (1950). The Basis for Scalogram Analysis. In S. A. Stouffer, L. Guttman, E. A. Suchman, Lazarsfeld, P. F., Star, S. A., & Clausen, J. A., Measurement and Prediction (pp. 60–90). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. doi:10.3102/ 003465430298487 Hofstede, G. (1986). Cultural differences in teaching and learning. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 10 (3), 301–320. doi:10.1016/0147-1767(86)90015-5 Krumsvik, R. J., & Ludvigsen, K. (2013). Theoretical and methodological issues of formative e-assessment in plenary lectures. International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning, 8(2), 78–92. doi:10.5172/ijpl.2013.8.2.78 Liem, A. D., Nair, E., Bernardo, A. B. I., & Prasetya, P. H. (2008). The influence of culture on students’ classroom social interactions. In D. M. McInerney & A. D. Liem (Eds.), Teaching and Learning: International Best Practice (pp. 377–404). Charlotte, NC: IAP. Ratnam-Lim, C. T. L., & Tan, K. H. K. (2015). Largescale implementation of formative assessment practices in an examination-oriented culture. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 22(1), 61–78. Ruiz-Primo, M., & Furtak, E. (2007). Exploring teachers’ informal assessment practices and students’ understanding in the context of scientific inquiry. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 44(1), 57–84. doi:10.1002/tea.20163 SEAMEO-INNOTECH (2012). Profile of multigrade schools in the Philippines. Watkins, D. (2008). Western Educational Research: A basis for educational reforms in Asia? In O. Tan, D. M. McInerney, G. A. D. Liem, & A. G. Tan (Eds.), What the West can learn from the East: Asian perspectives on the psychology of learning and motivation (pp. 59–76). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing. Wiliam, D., & Thompson, M. (2008). Integrating assessment with instruction: What will it take to make it work? In C. A. Dwyer (Ed.), The future of assessment: Shaping teaching and learning (pp. 53–82). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Winstone, N., & Millward, L. (2012). Reframing perceptions of the lecture from challenges to opportunities: Embedding active learning and formative assessment into the teaching of large classes. Psychology Teaching Review, 18(2), 31–41. Yorke, M. (2003). Formative assessment in higher education: Moves towards theory and the enhancement of pedagogic practice. Higher Education, 45(4), 477–501. doi:10.1023/A:1023967026413