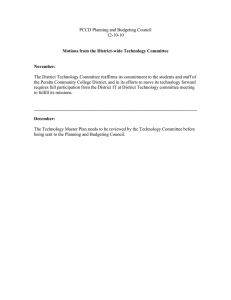

JCAF-21-1_20549.qxd 10/13/09 4:22 PM Page 65 ticl e u at r e ar fe Planning and Budgeting—Easing the Pain, Maximizing the Gain Norman L. Frause, Rick Brenner, Paul E. Juras, Carl L. Moravitz, Steven P. Schreck, and Alan J. Stratton L ike managers in many organizations, you may be feeling “pains” when working with your organization’s planning and budgeting process. Consider the following: • • • • improve the planning and budgeting process. We have embarked on an indepth, comprehensive study to analyze why these conditions exist, and we are providing recommendations for improvements to min© 2009 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. imize the overall frustration with the planning and budgeting You are not alone. These are process. The end result is a the issues that we have been wiki, which provides discussion researching for the past few material and recommendations years as an interest group in the to Consortium of Advanced Manminimize some of the “pains” agement-International (CAM-I). involved in developing your CAM-I is an international conbudget, regardless of whether sortium of manufacturing and your process results in a singleservice companies, government or multiple-year budget. Wikiorganizations, consultancies, wiki is a Hawaiian word that and academic and professional means quick. Wiki Web sites let bodies that cooperate in a preusers make additions or edit any competitive environment to page of the site. They often have a solve management problems common vocabulary and consider and critical business issues that themselves a “wiki” community. are common to the group. Our interest group is made up of PROCESS subject-matter experts representing a cross-section of these The work we have done various types of organizations, focuses on several broad all sharing a common goal to areas, but the overall goal In many organizations, one frequent outcome of the planning and budgeting process is widespread frustration. This article explains why some of these pains exist and how to resolve them. Instead of publishing a white paper or book with our material, we chose a wiki due to its technical capability of being able to interact with other interested parties to comment on our findings. Are you experiencing long cycle times, running many iterations, and ending up with outdated assumptions and inaccurate data by the time your budget is approved? Is your process too complex, planning at a low general ledger account level yet having to roll up the budget within a complex/multilayered organizational structure? Are your planning and budgeting tools obsolete, causing inaccurate data and many hours of overtime for your Finance Department? Does the budgeting system leave you struggling to deal with changing economic conditions? © 2009 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI 10.1002/jcaf.20549 65 JCAF-21-1_20549.qxd 10/13/09 4:22 PM Page 66 66 The Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance / November/December 2009 of improved planning and budgeting directly focuses on Exhibit 1 eliminating, reassigning, reengineering, and streamlining existing processes used for planning, Ten Pain Points budget, and overall resource management. We noted that 1. It takes too long. improvements should center on 2. It does not help me run my business. tackling such issues as: • • • • • • • 3. 4. 5. 6. integration into management processes, timeliness, flexibility, relevance, responsiveness, transparency, and ability to be easily understood. Trying to narrow down process components of such improvement was difficult, but our work centered on planning and budgeting concerns highlighted in a 2001 IBM presentation of results from a survey of people involved with planning and budgeting. The presentation, in part, dealt with a general discontent with the flow of planning and budgeting activities in organizations, which came to be known as common pains. The “ten pain points” listed in Exhibit 1 provide the focal point for drilling down to root causes and developing core best practices to apply to those causes. We used these ten pain points as the jumping-off point for exploration of process improvement opportunities. The group quickly found that improving capacity and core capabilities involves multiple steps affecting people, process, and technology. Exploration and discussion of those multiple steps allowed broader understanding of the improved processes and best practices that might allow organizations to DOI 10.1002/jcaf 7. 8. 9. 10. It is out of date before it is even finished. There is too much game playing. There are too many iterations. It is cast in stone, although business conditions are always changing. It involves too many people. It includes allocations that I cannot control. By the time it is done, I do not recognize my numbers. It does not match the objectives to which I am held accountable. better define linkages between these three crucial elements of business. Our exploration noted that process improvement does not erase political and policy concerns that are inherently part of any planning and budgeting process. Instead, efforts are needed to highlight the steps taken to shift the focus of discussion to those areas of improvement that one has control over, while acknowledging inherently political features that drive effects on decision making and resources. One of the most difficult parts of the planning and budgeting arena is the area of process mechanics—what does it take to keep things working well, while also being important to the real-life work of my organization? Delving into such concerns reveals such issues as: • Data Access and Standardization: There is no single data source accessible by all people and staff for data input, management, and analysis. Because each unit • • maintains a unique data set for its organization, reconciliation among and between unit information sources is difficult and time-consuming. Process Standardization on Guidelines and Formats: There is often a general lack of standardization in many processes across an organization. In many cases, standard procedures are available but are not known or followed. Nonstandardization results in multiple requests for the same information in differing formats, creating significant frustration throughout organizations that really do want to comply with requests. Review and Approval Process: The review and approval steps in most organizations and processes—many of which are in budget and planning—can be extensive, with much back-and-forth between different levels of the organization. Because these are many times done © 2009 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. JCAF-21-1_20549.qxd 10/13/09 4:22 PM Page 67 The Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance / November/December 2009 manually, a lot of time is spent on the low-value components of these steps. REENGINEERING AND NEW TECHNOLOGY OFTEN NEEDED An important lesson learned through our investigation was that organizations must first reengineer business processes to enhance productivity and efficiency. Companies that have developed new budget, planning, and/or performance management systems have learned that it is best to first make changes to their processes before trying to install a new system. Technology can play a significant role in organizational improvements. If new or improved processes are to be implemented, technology can be a significant change driver. Technology, however, is not a complete answer in and of itself. Technology should be viewed as a process enabler, leading to better performance by all levels of an organization. Business users should lead the effort to develop the specifications needed to use technology in their functional roles. Only then can individuals truly benefit to the fullest extent from the addition of technology in the workplace. Unfortunately, organizations often turn first to technology before fixing broken processes, which in the long run may suboptimize the ultimate benefit of technology investments, so it means not achieving the streamlining and cost savings necessary. Information and the need to make timely decisions may be risk antagonists. A clearer choice among alternatives may © 2009 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. require a great deal more data and analysis, and while technology investments may support additional data collection and analysis, they can delay decision making while they are made more robust. More information incurs costs, and those costs must be weighed against the desirability of having certainty in the ultimate choice. The stopping rule for each step of decision making is determined either by the action-forcing ability of an inflexible schedule or a judgment about the marginal benefits of the following: • • • obtaining and using more information; reducing uncertainty; and pursuing additional communication efforts. Companies that have developed new budget, planning, and/or performance management systems have learned that it is best to first make changes to their processes before trying to install a new system. One potential benefit of technology, however, is the ability to integrate more variables into the planning and budgeting process. Our attempt to forecast events and their impact makes it possible to react affirmatively to them before valuable resources are wasted. These added variables may relate to the risk factors an organization faces. RISK Planning and budgeting exists not to manage risk but to help an organization reach its 67 targets. But there’s always some risk that unforeseen events may hinder an organization’s ability to meet its targets. The question is whether the planning and budgeting process fails to explicitly recognize what those risks are, and how those risks might impede achieving a specific objective or the organization’s overall target. The past is fixed; the future is yet unwritten. What is certain is that change will come. Most organizations operate in an ever-changing environment and with operations that have both controllable and uncontrollable factors. A clear understanding of these factors and the influence they have on the organization will not only dictate how relevant the budget can be to begin with, but also how frequently budget assumptions will need to be updated or changed. If most factors are easy to forecast and will only change within an acceptable tolerance level, “across-the-board” restrictions in spending, even in the absence of flexible forecasting tools, may be an acceptable approach for managing the budget in the short term. Undoubtedly, this will not be the case for most organizations, so “across-the-board” and general restrictions in spending should be done in concert with a robust forecasting process that allows for analysis and scenario testing of assumptions with the current or baseline budget. To assume that the events and their impact can be known and locked down into a planning and budgeting document is folly, but failing to plan because of uncertainty is an even greater folly. Examples of such unforeseen events include: DOI 10.1002/jcaf JCAF-21-1_20549.qxd 10/13/09 4:22 PM Page 68 68 The Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance / November/December 2009 • • • • • reorganizations; catastrophic events (e.g., changes in the economy, political unrest, or war); mergers or acquisitions; changes in leadership (e.g., a new CEO or top executive); and acts of nature (e.g., Hurricane Katrina or a blizzard). The planning and budget process, through improved communications and systemic business operating guidelines in periods of emergency, can help organizations better navigate through such events. FOUR STEPS FOR ADDRESSING UNFORESEEN RISKS The budgeting process needs a mechanism to more effectively address unforeseen risks. We propose that a four-step process described in Exhibit 2 be adopted as part of the planning and budgeting process. Events are not the only risk factors; assumptions are also a point of vulnerability. Plans and budgets are forward-looking, which means that the assumptions will always be questionable but necessary. In fact, no other management process likely has as much dependence on assumptions as does the planning and budgeting process. Some major categories of assumptions include: • • • • • • • organization, competition, regulatory, the economy, customers, suppliers, and processes. Assumptions in the planning and budgeting process are essential simply because regardless of how good someone’s crystal ball may be, the nature of forecasting always leaves something to the unknown. A major factor in the accuracy of assumptions turns out to be time, which is driven in part by the time required for the planning process. Organizations that take several months to establish their budgets (three, six, nine, or even more) may find that assumptions originally submitted with planning guidelines become obsolete by the time the planning process is Exhibit 2 Four Risk-Related Principles for Planning and Budgeting Basic risk-related principles that should be incorporated into the planning and budgeting process include: 1. Identifying the significant risks that might threaten the achievement of the strategies and objectives; 2. Assessing the identified risks in terms of dollar impact and the related likelihood the event will occur; 3. Deciding what action to take in response to the risks, ranging from full mitigation to acceptance as is; and 4. Explicitly incorporating those decisions into the formal budget. DOI 10.1002/jcaf complete. Some assumptions may be trivial and not worth the effort to subject to risk assessment. The criteria for such assessment should be driven by the strength of, and reliance on, key assumptions, and their impact on alternative decision choices. Critical assumptions, however, should be periodically reevaluated and updated in order to remain in sync with current business conditions and other budget decisions before the budget is approved. Whenever there are clearly defined goals and objectives, there is some likelihood that events will occur that would impact the organization’s ability to achieve them. So, broadly defined, risk includes any event or action that could adversely affect an organization’s ability to achieve its business objectives or successfully execute its strategy. The ability of an organization to adapt to its changing environment is critical to ensuring optimal effectiveness over time. The underlying objective is that the planning and budgeting process should accommodate reprioritization for unforeseen events via existing budget mitigations and shifting resources from less critical elements. As we shall see in the next section, effective communication is important within any organization. For now, it is enough to recognize that planning and budgeting decisions have impact on the organization when they are either shared or communicated in some way. As decisions are made, there will be people who disagree with the decision. While there are some people who do not like disagreement, disagreement is an essential part of the process that brings out risks, benefits, costs, and other information. © 2009 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. JCAF-21-1_20549.qxd 10/13/09 4:22 PM Page 69 The Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance / November/December 2009 ACCOUNTABILITY One of the objectives of the planning and budgeting process is to establish goals and objectives for the organization. Once these are defined, individuals can be held accountable to the defined performance standards/ measures. As previously noted, effective communication is critical, as it can make a standard relevant to the individual who is accountable. Standards— particularly performance measures—that the individual cannot relate to will (at best) be ignored or (at worst) create dysfunctional behavior. Establishing accountability goes beyond determining who is accountable; it also addresses the standards that are used for determining that accountability. To gain buy-in, managers must ensure that those held accountable have input into objectives and related performance targets. Such involvement promotes understanding of the expectations and provides a sense of ownership. While there is little doubt that establishing clearly defined objectives and accountability for the planning and budgeting process is a key element to a successful planning and budgeting process, there are some suggestions to be followed focused primarily on the development and management of standards. Some key factors to consider are: • Buy-in: Include participants and stakeholders in establishing standards that dictate both the objectives and accountability to help ensure buy-in to the process and results. © 2009 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. • • • Constant Standards: Seek standards that can remain mostly constant across several important dimensions. (An example dimension is time; because business operations are dynamic, organizations must set an appropriate time horizon.) Clarity: While the standards should be clear, they should not be rigid, for having standards that are flexible and/or dynamic enough to allow for variations in the business environment will extend the life of the results. Flexibility: A common complaint is that the budget is “cast in stone” despite significant changes in the operating climate. Such a Establishing accountability goes beyond determining who is accountable; it also addresses the standards that are used for determining that accountability. complaint usually indicates that either the time horizon is too long for the organization’s climate or that appropriate update procedures and schedules need to be added to the process timeline to ensure accurate assumptions and estimates. Standards do not require that amounts be in absolute terms. Standards may consist of rates or ratios that are fixed but then are applied to dynamic bases, ones that are either internal or external. Appropriate usage of fixed rates against dynamic bases may be a valueadded answer to the “cast in stone” complaint. 69 Accountability is a valued principle for assessing an organization’s effectiveness, efficiency, and success, and it is a good lead-in to a final discussion on integration of planning and budget with performance, a measure of true accountability. COMMUNICATION Effective communication is important within any organization, and the planning and budgeting process can serve as a tool to facilitate communication. The planning and budgeting process is an essential part of the overall organizational communication process, as it provides context and a process to make and communicate decisions and promotes alignment throughout the entire organization. There should be twoway communications between strategy development teams and the planning and budgeting process early on since it could impact people, facilities, capital equipment, and other resource items required by the planning and budgeting process. For companies doing business with the government that may require them to submit a Cost Accounting Standards Board (CASB) disclosure statement, the process of getting annual accounting changes reviewed and approved can take a considerable amount of time. This impacts the alignment of the accounting structure that must be in place before assigning resources within any cost modeling process and can prolong the cycle time of the planning process. It is through the planning and budgeting process that organizational units communicate their desired plans/initiatives and the DOI 10.1002/jcaf JCAF-21-1_20549.qxd 10/13/09 4:22 PM Page 70 70 The Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance / November/December 2009 resources required to accomplish them. As budget requests go up the chain for review/ approval, upper management can consider these priorities relative to those from other organizational units. Funding decisions are then communicated back down the chain to communicate the priorities for the organization as a whole. This also communicates the organization’s priorities to external stakeholders. To facilitate the communication, both internally and externally, the process and underlying information must be transparent so all involved understand the decisions made. The process must provide visibility to both the decision process and decision basis. The communication of processes and steps taken to arrive at a substantive decision can be just as important as the final decision, providing participants and subordinates a fuller awareness of additional information, or considerations that the decision maker had to address in making final determinations on resources and policy. If the process is robust, participants will gain trust in the process and its results. In contrast, if the process is not sufficiently transparent, there is greater likelihood of bad decisions or that decisions will not be made at all, or that decisions once made will not be accepted by those who must implement them. Key assumptions related to the overall strategy of the company should be included in the planning guidelines and communicated to all participants in the planning process. As noted DOI 10.1002/jcaf earlier, assumptions should span all operational facets of the business, but, more importantly, management must help ensure that a common set of assumptions is used if it is to allow them to work harmoniously throughout the planning and budgeting process. To ensure this commonality, some communication mechanism is necessary. One solution is to implement a planning directive via a recognized authority for shared assumptions. This directive would communicate, before each budget/plan iteration, major guidelines, common The communication of processes and steps taken to arrive at a substantive decision can be just as important as the final decision, providing participants and subordinates a fuller awareness of additional information, or considerations that the decision maker had to address in making final determinations on resources and policy. assumptions to be incorporated, central overhead/planning rates that are to be commonly used, and elements that should be included or excluded by all. This will not only help communication, but also ensure the elements are treated consistently across the planning and budgeting system. The final step is the robust communication of decisions. As decisions are made, there will be people who disagree with the decision. If there is sufficient visibility, they should at least appreciate and respect the basis for the decision. Also, the choice expressed in the decision should be clear—not subject to varying interpretations by others in the organization or its stakeholders more broadly. In this way, future decisions can be focused on relevant issues of concern and can be made by relevant participants. The negative aspect of robustly communicating decisions, however, is that they can be perceived as being “cast in stone” either when they should not be or are, in fact, not meant to stifle discussion but to shape it. Throughout this process, significant visibility is gained as operational and financial data, relationships, and results are integrated with each other. The financial and operational views represent specialized viewpoints into the same data, relationships, and results. These differing views of events drive what appear to be two different languages: operating and financial. While each of the different languages has its distinct purpose, they also drive some dysfunctional behaviors when each “speaker” fails to recognize the other’s purpose and distinctive features. For example, when operational personnel fail to recognize and appreciate the financial consequences of their processes, the entire business suffers. Similarly, financial measures that cannot be translated into operational terms should be discarded or discontinued. A purely financial plan or budget cannot attain the desired degree of visibility or transparency, so an effective planning and budgeting process will have to provide translation © 2009 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. JCAF-21-1_20549.qxd 10/13/09 4:22 PM Page 71 The Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance / November/December 2009 between operational and financial languages. Measures must be relevant on both sides of the “language” barrier. We must also address when there is a disconnect between financial players and operational players in the budget process. Both views/parties must be partnered for validation, feasibility, and communication, which, in turn, can promote accountability. INTEGRATING PERFORMANCE WITH PLANNING AND BUDGETING A final, but important piece to improving business processes is the step taken to integrate performance into improvement efforts. Although the focus of most of the CAM-I Planning and Budget interest group research has been on the core business processes surrounding budget management and budget building, we have understood the critical importance of ensuring that performance and the measurement of results are part of the overall effort. Today’s philosophy of performance-based management starts with a systematic approach to performance improvement. It requires an ongoing process of establishing strategic performance objectives; measuring performance; collecting, analyzing, reviewing, and reporting performance data; and using that data to drive performance improvement. In the performance-based management process, the first step is to identify an organization’s strategic goals and performance objectives. This step also involves the establishment of performance measures based © 2009 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. on and linked to the outcomes of the strategic planning phase. Following that, the next steps are to do the work; collect performance data (i.e., measurements); and analyze, review, and use that data to drive performance improvement (i.e., make changes and corrections and/or “fine tune” organizational operations). Lastly, management reports the data and makes necessary changes or corrections. Then, the process starts over again. Organizations regularly collect timely and credible performance information— including information from its program partners and contractors—and use that information to manage the programs and Performance management essentially uses performance information to manage and improve performance and to demonstrate what has been accomplished. 71 Our study noted the pursuit of systematic uses of performance planning, budgeting, and financial information as essential to achieving a more results-oriented and accountable organization and, therefore, recommends that this be a valued part of any effort to improve business processes. Performance-based budgeting— the integration of planning and budgeting with performance results—is just one component of an organization’s total performance management that brings together people, processes, and technology to leverage decision making and resource management. However, it is a major link to overall performance management success. Pursuing a systematic use of performance planning, budgeting, and financial information is essential to achieving a more results-oriented and accountable government. WHAT YOU CAN DO improve its performance. For instance, this could include adjusting program priorities, making resource allocations, or taking other appropriate management actions. Performance management essentially uses performance information to manage and improve performance and to demonstrate what has been accomplished. Performance measurement, in simplest terms, is the comparison of actual levels of performance to pre-established target levels of performance. Moreover, performance measurement is a critical component of performance-based management. We have actually implemented some of our recommendations, and they are proving to be successful. We are providing a forum through our wiki for you to help build on our research to make this body of information even more robust and to help communicate our findings to your peers and business partners, whether private industry or government agencies. We are also providing you with the opportunity to comment on and/or to add to our research and recommendations. For access to our wiki, please send an e-mail to nancyt@cam-i.org with Wiki in the subject line. We welcome your participation. DOI 10.1002/jcaf JCAF-21-1_20549.qxd 72 10/13/09 4:22 PM Page 72 The Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance / November/December 2009 Norman L. Frause is a business manager supporting desktop systems in the Boeing Company’s Computing and Network Operations group in Seattle. He can be reached at Norman.L.Frause@Boeing.com. Rick Brenner is a senior manager for Grant Thornton LLP in Alexandria, Virginia. He can be reached at Rick.Brenner@gt.com. Paul E. Juras is a professor of accountancy at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. He can be reached at Juras@wfu.edu. Carl L. Moravitz is a senior managing consultant for IBM’s Global Business Services in Alexandria, Virginia. He can be reached at moravitz@us.ibm.com. Steven P. Schreck is a finance manager for the Boeing Company in Seattle. He can be reached at steven.p.schreck@boeing.com. Alan J. Stratton is with Stratton & Associates in Tigard, Oregon. He can be reached at stratton.aj@gmail.com. DOI 10.1002/jcaf © 2009 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.