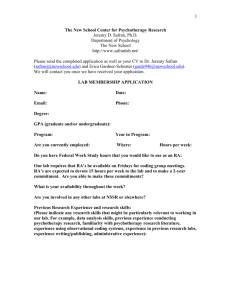

Running head: CORE PRINCIPLES OF CONDUCTING GROUP PSYCHOTHERAPY 0 Core Principles of Conducting Group Psychotherapy Michelle P. George University of Wollongong Author Note This paper was submitted to fulfil the requirements for PSYP923 on the 8th April 2020 wc 2059 CORE PRINCIPLES OF CONDUCTING GROUP PSYCHOTHERAPY 1 Core Principles of Conducting Group Psychotherapy Psychological treatments which are conducted as groups form an integral part of schoolbased mental health programmes. The three-tiered approach cites, group treatment is provided when identified groups of students require interventions which may be focussed on specific goals or risk prevention (McKenzie, Vidair, Eacott & Sauro, 2017). This paper aims to provide an outline of some core principles in conducting group psychotherapy with a focus on school psychologist practitioners. The following report is organised around principles found in the American Group Psychotherapy Association (AGPA) Practice Guidelines for Group Psychotherapy (see Appendix A) which incorporate APS standards of respect, propriety and integrity. The core principles include: Starting well; understanding therapeutic factors and therapeutic mechanisms; understanding group development and group processes; reducing adverse outcomes; and planning for the termination of the group. These principles can apply to any psychotherapy group, but some issues of concern for school psychologists will also be considered. Group therapy is a specialised form of psychotherapy, whereby several clients confront their personal problems together with the guidance of a therapist or co-therapists. (Barlow, 2008). Groups that have been organised for the purpose of psychological change come in a variety of theoretical leanings and may be targeted to specific populations. For example, psychodynamic group therapy for people with personality disorders (Kvarstein et al., 2017) and group-based cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety (Espejo et al., 2017). Despite the different theoretical leanings and goals, many of these groups share the same basic principles. In that, all psychotherapy groups aim to remedy mental disturbances and interpersonal difficulties in people. Rather than just interacting one to one with a therapist, groups provide the opportunity to interact CORE PRINCIPLES OF CONDUCTING GROUP PSYCHOTHERAPY 2 with others, so the group provides an immediate experience of testing their insights and trailing new skills (Dishion & Stormshak, 2007). Group psychotherapy uses the ‘group entity’ as an agent for change in-that interactions that take place between group members are an essential ingredient of the therapeutic process (Barlow & Burlingame, 2006). The assumption is that individual dynamics, interpersonal dynamics, and ‘group as a whole’ dynamics all work together to provide a vehicle of change (Bernard et al., 2008). The combination of these dynamics as a therapeutic mechanism is often referred to as group cohesion (Burlingame et al., 2001; Yalom & Leszcz, 2005). There is a vast body of research exploring group dynamics and the benefits of group therapy (Corey & Corey, 2016). School psychologists may be asked to provide group therapy for a target population within the school community. As part of the scientist-practitioner model, finding credible evidence that a group-based intervention is effective or at least not harmful is the first priority. For example, two Cochran reviews of group-based psychotherapy for adolescences who selfharm found that it was not supported or the evidence was of low quality (Hawton et al., 2015; Vincent, 2016). However, for people with autism spectrum disorder, social skills groups are recommended. The results of a Cochran meta-analysis found that participants in social skills groups made clinically significant gains in social competence and experienced better friendships (Reichow et al., 2012). Finally, one more Cochran review cites evidence that group‐based parenting programmes improved behaviour in children along with reducing anxiety, stress and depression in parents (Furlong et al., 2012). Peer reviewed literature will assist in deciding whether a group-based program is appropriate. Once a decision has been made to run a group for a targeted population to achieve the desired goal, the AGPA guidelines provide direction so that the intervention can be implemented efficiently and ethically. CORE PRINCIPLES OF CONDUCTING GROUP PSYCHOTHERAPY 3 School psychologists will need to navigate the ethical complexity of multiple clients (group members, teachers and the school as a whole) and proactively address issues before they arise. For example, a psychologist may be asked to provide group therapy for students at their school; in doing so, they find that teachers are not supportive of the intervention. The AGPA guidelines provide support in the first section, Starting Well: Administrative Collaboration. It suggests that psychologists gather evidence from the literature and stakeholders to provide a credible program which will be appreciated and embedded into the school context. Arranging meetings and providing information about the practicalities such as timeframe and specific goals of the intervention will help to gain support for it (Bernard et al., 2008). Before a group-based program can commence, all students will require parent or guardian consent to participate (Australian Psychological Society, 2018). Under the APS Code of Ethics, groups of people are clients (APS p. 8) and as such, are treated with respect regarding informed consent and confidentiality. However, the issue of how a practitioner will manage an individual’s privacy with the other group members is a problem encountered with group work. The AGPA recommends that group leaders pay special attention to establishing group norms around disclosure of information and confidentiality that respect the rights of everyone in the group. An agreement can take the form of a group contract or expectations which explicitly state group member rights and responsibilities (Bernard et al., 2008). Once norms have been agreed upon, the therapist needs to maintain and manage the agreement as part of setting up a therapeutic alliance at each meeting. The psychologist should be particularly mindful that the group members will have existing relationships with each other outside the group, such as classmates or friends. This adds more complexity to issues surrounding confidentiality. Goffman (1961) explored a process called ‘looping’, where inpatients had confidential information that they CORE PRINCIPLES OF CONDUCTING GROUP PSYCHOTHERAPY 4 disclosed in the therapy group fed back to them (via group members and staff) in other social contexts. Uncertainty around privacy undermines the safety of the group as a therapeutic environment and may impede participants from sharing personal information (Pepper, 2004). Special consideration around respect needs to be reinforced by the therapist and privacy is dependent on the actions of the group members. Providing group-based psychotherapy is complex and requires specific skills in group dynamics (Yalom & Leszcz, 2005). AGPA guidelines provide a framework for understanding these dynamics in the Group Development and Group Process sections. Group development theory helps the therapist plan the intervention with time limitations and provides a model for testing hypotheses around particular group behaviour (Corey & Corey, 2016). Development models also provide a predictable sequence of events that a likely to occur in all groups such as Tuckman’s (1965) Five-Stage model of forming, storming, norming, performing and adjourning (Tuckman, 1965). MacKenzie (2004), describes group developmental classification in four stages: Engagement, differentiation, interpersonal work, and termination. During engagement, participants find similarities and get to know the boundaries of the group as a place that is different to the outside world. In the differentiation stage tensions are realised and worked on before moving into the more personal issues during the interpersonal work phase. The termination phase is important for consolidation of changes made during the group. Group development stages are useful for predicting and understanding the group member’s behaviour. Knowledge of group process will assist the therapist in harnessing the therapeutic factors which belong to the group and are outside of the therapist or a particular method. For example group cohesion is assumed to be a psychological construct belonging to the group as a whole; it is considered a therapeutic mechanism akin to the therapeutic relationship (Johnson et al., 2005). CORE PRINCIPLES OF CONDUCTING GROUP PSYCHOTHERAPY 5 Cohesion is construed as something positive in the mind of the participant, it contains factors of relationship bonds and agreement on tasks and goals (Schnur & Montgomery, 2010). Fostering a cohesive environment is essential to change in group psychotherapy in the same way that therapeutic relationship is essential to individual therapy (Yalom & Leszcz, 2005). This is often seen early in the development of the group, in the “engagement” stage when everyone is cordial and working towards the same goal (MacKenzie, 2004). Group cohesion is also used as a gauge of progress that can be monitored by the therapist. Several cohesion questionnaires have been developed to be used as outcome measures for therapy, making it easier for psychologists to monitor change in the group and individuals (Gleave et al., 2017). Cohesion measures can provide valuable feedback to the program’s participants and stakeholders, they also contribute to data collection as part of the scientist-practitioner model. While conducting the group, instances will arise that seem less cohesive and more confrontational. Therapists are subjected to multiple transferences from individual group members or subgroups within the group. Personal and professional boundaries become more complicated because of the multiple relationships that exist in the group Self-refection and identifying countertransference are ways of avoiding reactions which may reflect poorly on the therapist’s conduct (Tasca et al., 2016). For example, group leaders may consciously or unconsciously collude with the group members in scapegoating (MacKenzie, 2004). Scapegoating refers to projecting unwanted self-aspects onto another person who is labelled as deviant (Moreno, 2007). A scapegoat can protect the group leader, instead of confronting the therapist directly with their frustration, the group members attack the scapegoat. The group leader needs to be aware of this and not join the group's efforts to confront or correct the person being used as a scapegoat (Moreno, 2007). CORE PRINCIPLES OF CONDUCTING GROUP PSYCHOTHERAPY 6 The AGPA’s guidelines state how the management of countertransference is more difficult in groups compared to individual therapy in the Individual Member and Leader Roles, section. It is essential to recognise if reactions emerge from the therapist's unresolved issues or if they are induced by interaction with the group. Understanding and working through scapegoating as a group phenomenon can be underpinned by a variety of theories (Finlay et al., 2016). In the context of school psychology, drawing attention to what has taken place in the group regarding scapegoating could be useful and often reflects issues such as bullying (Dixon, 2007). It is the psychologist’s responsibility to intervene so that no group member is harmed by hurtful or stigmatising exchanges (MacKenzie, 2004). For example, the therapist can keep the behaviour in-check by asking what other members think about the exchange. The therapist can then guide the discussion into a more in-depth exploration of the issues and possibly serve as a model for the group. Reducing adverse outcomes from scapegoating is yet another challenge that is unique to group work. As in individual psychotherapy, termination of the therapy sessions should be planned for in group psychotherapy. Planning for termination is essential for helping members who have had difficult or traumatic departures in the past. Group members will display various reactions to the dissolution of the group such as sadness, anxiety or abandonment. The therapist is responsible for reviewing and reinforcing the gains made during the sessions and provide a space that helps members process feelings of ambivalence during termination (Bernard et al., 2008). As the AGPA guidelines recommend, this can be done via a celebration or a ritual. Group members may say something positive about the group or another group member. Positive statements or observations can be written down for each person, anonymously, and handed out for participants to keep. By doing this, the psychologist normalises the combination of positive feelings and CORE PRINCIPLES OF CONDUCTING GROUP PSYCHOTHERAPY 7 feelings of sadness associated with ending. They will also reinforce the interpersonal gains made and provide a role model for future goodbyes (Bernard et al., 2008). This paper provides a summary of some core principles of conducting group psychotherapy and highlights a few of the issues which could be faced when providing group therapy in schools. The AGPA’s Clinical Practice Guidelines for Group Psychotherapy (2008) were designed to provide to “support for practitioners of group psychotherapy to meet the appropriate demands for evidence-based practice and provide greater accountability in the practice of contemporary psychotherapy” (Bernard et al., 2008, p 456). The core principles include making thorough preparation before the group commences with consideration to evidence-based practice, obtaining consent from multiple clients. Establishing group norms are core to managing confidentiality and establishing a group climate of safety. The core principle of cohesion is vital as a therapeutic mechanism of change; it is also a means to measure progress which informs the scientist-practitioner. Reducing adverse events and facilitating a supportive ending to the sessions are crucial to conducting group psychotherapy. Although the task of conducting group psychotherapy is complex and fraught with challenges, there is a high demand for group-based services as they are an effective form of therapy for a variety of conditions (Blackmore et al., 2012; Burlingame, 2018; Reavley, Bassilios, Ryan, Schlichthorst, Nicholas, 2015). CORE PRINCIPLES OF CONDUCTING GROUP PSYCHOTHERAPY 8 Important References *** Yalom, I. D., & Leszcz, M. C. (2005). The theory and practice of group psychotherapy (5th edition). This book is like the bible of group-therapy. The original work was published in 1967 and the most recent edition 2005, it is amazing that it contains the same core concepts and is still relevant for student’s learning group psychotherapy today. Almost every article on group Psychotherapy cites the work of Yalom. This work is elegantly written and easy to follow with footnotes, including additional clarification and supporting research. **Bernard, H., Burlingame, G., Flores, P., Greene, L., Joyce, A., Kobos, J. C., Leszcz, M., Semands, R., Piper, W., Mceneaney, A., & Feirman, D. (2008). Clinical practice guidelines for group psychotherapy. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 58(4), 455–542. This paper was authored by the Science to Service Task Force of the American Group Psychotherapy Association, chaired by Drs. Kobos and Leszcz. It provides practitioners with clear and concise information regarding the core principles of group psychotherapy as well as guidelines for handling issues that arise in group settings regardless of the theoretical orientation of the intervention. The principles are relevant to diverse client populations in a variety of treatment settings, including schools. These guidelines were due to be reviewed in 2015; however, a more recent edition could not be found. * MacKenzie, K. R. (2004). The alliance in time-limited group psychotherapy. This chapter in The Therapeutic Alliance in brief Psychotherapy provides some valuable insights for therapists from MacKenzie who has contributed a vast amount of research in the field of group psychology. Again, the literature seems old; however, no recent contributions provide a clearer or more concise explanation of the concepts in group psychotherapy. This chapter gives the CORE PRINCIPLES OF CONDUCTING GROUP PSYCHOTHERAPY 9 practitioner a guide to the basic principles of group therapy and includes a copy of the Group Climate Questionnaire for therapists to use. References Australian Psychological Society. (2018). The framework for effective delivery of school psychology services: a practice guide for psychologists and school leaders APS Professional Practice. March. https://www.psychology.org.au/getmedia/249a7a14-c43e4add-aa6b-decfea6e810d/Framework-schools-psychologists-leaders.pdf Barlow, S. H. (2008). Group psychotherapy specialty practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 39(2), 240–244. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.39.2.240 Barlow, S. H., & Burlingame, G. M. (2006). Essential theory, processes, and procedures for successful group psychotherapy: Group cohesion as exemplar. In Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02729053 Bernard, H., Burlingame, G., Flores, P., Greene, L., Joyce, A., Kobos, J. C., Leszcz, M., Semands, R. R. M., Piper, W. E., Mceneaney, A. M. S., & Feirman, D. (2008). Clinical practice guidelines for group psychotherapy. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 58(4), 455–542. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijgp.2008.58.4.455 Blackmore, C., Tantam, D., Parry, G., & Chambers, E. (2012). Report on a Systematic Review of the Efficacy and Clinical Effectiveness of Group Analysis and Analytic/Dynamic Group Psychotherapy. Group Analysis, 45(1), 46–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0533316411424356 Burlingame, G. M. (2018). Cohesion in Group Therapy: A Meta-Analysis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 384–398. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000173 CORE PRINCIPLES OF CONDUCTING GROUP PSYCHOTHERAPY 10 Burlingame, G. M., Fuhriman, A., & Johnson, J. E. (2001). Cohesion in group psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 38(4), 373–379. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.38.4.373 Corey, G., & Corey, M. (2016). Group psychotherapy. In R. Norcross, J.C, VandenBos, G. R., Freedheim, D. K. and Krishnamurthy (Ed.), APA Handbook of Clinical Psychology: Applications and Methods (pp. 289–306). American Psychological Association. Crowe, T. P., & Grenyer, B. F. S. (2008). Is therapist alliance or whole group cohesion more influential in group psychotherapy outcomes ? Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 15, 239–246. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.583 Dishion, T. J., & Stormshak, E. A. (2007). Child and Adolescent Intervention Groups. In Intervening in children’s lives: An ecological, family-centered approach to mental health care. (pp. 201–215). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11485012 Dixon, R. (2007). Scapegoating: Another Step Towards Understanding the Processes Generating Bullying in Groups? Journal of School Violence, 6(4), 81–103. http://10.0.5.20/J202v06n04_05 Espejo, E. P., Gorlick, A., & Castriotta, N. (2017). Changes in threat-related cognitions and experiential avoidance in group-based transdiagnostic CBT for anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 46, 65–71. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.06.006 Finlay, L. D., Abernethy, A., & Scott, G. (2016). Scapegoating in Group Therapy: Insights from Girard’s Mimetic Theory. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 66(2), 188–204. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00207284.2015.1106174 Furlong, M., McGilloway, S., Bywater, T., Hutchings, J., Smith, S. M., & Donnelly, M. (2012). Behavioural and cognitive‐behavioural group‐based parenting programmes for early‐onset CORE PRINCIPLES OF CONDUCTING GROUP PSYCHOTHERAPY 11 conduct problems in children aged 3 to 12 years. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008225.pub2 Gleave, R. L., Burlingame, G. M., Beecher, M. E., Griner, D., Hansen, K., & Jenkins, S. A. (2017). Feedback-informed group treatment: Application of the OQ–45 and Group Questionnaire. Feedback-Informed Treatment in Clinical Practice: Reaching for Excellence., 141–166. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000039-008 Hawton, K., Witt, K. G., Taylor Salisbury, T. L., Arensman, E., Gunnell, D., Townsend, E., van Heeringen, K., & Hazell, P. (2015). Interventions for self-harm in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 12. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012013 Johnson, J. E., Burlingame, G. M., Olsen, J. A., Davies, D. R., & Gleave, R. L. (2005). Group climate, cohesion, alliance, and empathy in group psychotherapy: Multilevel structural equation models. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(3), 310–321. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.3.310 Kvarstein, E. H., Nordviste, O., Dragland, L., & Wilberg, T. (2017). Outpatient psychodynamic group psychotherapy – outcomes related to personality disorder, severity, age and gender. Personality and Mental Health, 11(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmh.1352 MacKenzie, K. R. (2004). The alliance in time-limited group psychotherapy. In J. Safran, J. and Muran (Ed.), The therapeutic alliance in brief psychotherapy. (pp. 193–215). https://doi.org/10.1037/10306-008 Moreno, J. K. (2007). Scapegoating in group psychotherapy. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 57(1), 93–104. Pepper, R. S. (2004). Confidentiality and dual relationships in group psychotherapy. CORE PRINCIPLES OF CONDUCTING GROUP PSYCHOTHERAPY 12 International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 54(1), 103–114. Reavley, N., Bassilios, B., Ryan, S., Schlichthorst, M., Nicholas, A. (2015). Interventions to Build Resilience Among Young People: A literature review, Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, Melbourne. Reichow, B., Steiner, A. M., & Volkmar, F. (2012). Social skills groups for people aged 6 to 21 with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 7. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008511.pub2 Schnur, J. B., & Montgomery, G. H. (2010). A systematic review of therapeutic alliance, group cohesion, empathy, and goal consensus/collaboration in psychotherapeutic interventions in cancer: Uncommon factors? Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 238–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.005 Tasca, G. A., Mcquaid, N., & Balfour, L. (2016). Complex contexts and relationships affect clinical decisions in group therapy. Psychotherapy, 53(3), 314–319. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000071 Tuckman, B. W. (1965). Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63(6), 384–399. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0022100 Vincent, E. C. (2016). Can either dialectical behavior therapy or group‐based psychotherapy reduce self‐harm behaviors in adolescents? Cochrane Clinical Answers. https://doi.org/10.1002/cca.1251 Yalom, I. D., & Leszcz, M. C. (2005). The theory and practice of group psychotherapy. CORE PRINCIPLES OF CONDUCTING GROUP PSYCHOTHERAPY Apendix A The AGPA Practice Guidelines for Group Psychotherapy 1. Creating successful therapy groups i. Starting well—Client referrals ii. Starting well—Administrative collaboration 2. Therapeutic factors and therapeutic mechanisms i. Mechanisms of change in group psychotherapy ii. The therapeutic factors iii. Cohesion—A core mechanism of change iv. Relationship of cohesion to other therapeutic factors v. Evidence-based principles related to group cohesion: Group structure, verbal interaction, emotional climate vi. Assessment of therapeutic mechanisms in clinical practice 3. Selection of clients i. Inclusion criteria ii. Exclusion criteria iii. Premature termination iv. Patient Selection Instruments v. Composition of therapy groups 4. Preparation and pre-group training i. Objectives of preparation: Establish the therapeutic alliance, reduce patient anxiety, provide information, consensus on treatment goals 13 CORE PRINCIPLES OF CONDUCTING GROUP PSYCHOTHERAPY ii. Methods and procedures iii. Impact and benefits 5. Group development i. Models of group development and assumptions ii. Developmental stages 6. Group process i. The group as a social system ii. Work, therapeutic and anti-therapeutic processes iii. The group as a whole iv. Splits and subgroups v. The pair or couple vi. The individual member and leader roles 7. Therapist interventions i. Executive function ii. Caring iii. Emotional stimulation iv. Meaning attribution v. Fostering client self-awareness vi. Establishing group norms vii. Therapist transparency and use of self 8. Reducing adverse outcomes and the ethical practice of group psychotherapy i. Professional ethics ii. Group pressures 14 CORE PRINCIPLES OF CONDUCTING GROUP PSYCHOTHERAPY iii. Record keeping iv. Confidentiality, boundaries and informed consent v. Dual relationships vi. Preventing adverse outcomes by monitoring treatment progress 9. Concurrent therapies i. Concurrent group and individual therapy ii. Combining group therapy and pharmacotherapy iii. Twelve step groups 10. Termination of group psychotherapy i. Unique aspects of termination in group therapy ii. Time-limited groups iii. Open-ended groups iv. Premature termination v. Ending therapy with personal satisfaction vi. A dilemma of the open-ended group vii. Ending rituals viii. Therapist departures 15