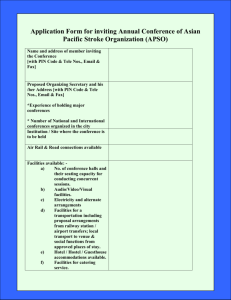

Accounting, Organizations and Society 30 (2005) 279–296 www.elsevier.com/locate/aos The construction of a social account: a case study in an overseas aid agency Brendan OÕDwyer * Department of Accountancy, Michael Smurfit Graduate School of Business, University College Dublin, Blackrock, Co. Dublin, Ireland Abstract This paper presents a case study examining the evolution of a social accounting process in an Irish overseas aid agency, the Agency for Personal Service Overseas. Much of the corporate rhetoric surrounding social accounting processes simplifies their complex nature and tends to downplay many concerns as to how they can effect ÔrealÕ organisational change and empower stakeholders. The case exposes this complexity by illuminating the contradictions, tensions and obstacles that permeated one such process. The paper contributes to the recent increase in field work in the social accounting literature, called for by Gray [Account. Orga. Soc. 27 (2002) 687], which seeks a richer, more in-depth understanding of how and why social accounting evolves within organisations. Ó 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Introduction This paper presents a case study examining a social accounting process in an Irish overseas aid agency, the Agency for Personal Service Overseas (APSO). The case examines how and why the social accounting process evolved within APSO focusing in particular on the extent of stakeholder empowerment within the process. This exposes the complexities and obstacles encountered during the stakeholder engagement and social account construction phases of the process. Several social accounting scholars contend that formal social accounting processes should enhance corporate transparency and accountability by creating ‘‘a new internal visibility of the workings of. . . organisation[s]’’ (Owen, Gray, & Bebbington, 1997, pp. 191–192) in order to empower stake* Tel.: +353-1-7168038; fax: +353-1-7168814. E-mail address: brendan.odwyer@ucd.ie (B. OÕDwyer). holders ‘‘to seek more benign organisational activity’’ (Gray, Dey, Owen, Evans, & Zadek, 1997, p. 329, see also, Adams & Harte, 2000; Bebbington, 1997; Gray, 2000, 2002; Hill, Fraser, & Cotton, 1998, 2001; Larrinaga-Gonzalez & Bebbington, 2001; OÕDwyer, 2001, 2003; Owen et al., 1997; Owen, Swift, Humphrey, & Bowerman, 2000; Owen, Swift, & Hunt, 2001; Thomson & Bebbington, 2004; Unerman & Bennett, 2004). Recent social accounting practice also purports to concern itself with accountability, transparency and stakeholder empowerment (Adams, 1999, 2002, forthcoming; Cotton, Fraser, & Hill, 2000; Dawson, 1998; Elkington, 2001; Gray, 2001, 2002; Gray et al., 1997; Kent, 2002; Owen et al., 2001; Raynard, 1998; Zadek, 2002). Despite widespread calls in the literature for richer, more in-depth and sustained examinations of the emergence of social accounting processes (Gray, 2002; Thomson & Bebbington, 2004), in particular the role and involvement of stakeholders therein, few studies of 0361-3682/$ - see front matter Ó 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2004.01.001 280 B. O’Dwyer / Accounting, Organizations and Society 30 (2005) 279–296 this nature have been conducted. Notwithstanding this lack of in-depth empirical insight, widespread suspicion has been expressed in the social accounting literature about the extent of the role played by stakeholders in these processes (Gray, 2000, 2001; Owen et al., 2001; Thomson & Bebbington, 2004). There have been suggestions that stakeholder engagement exercises often constitute little more than management control devices used by organisational managers to manage external pressures threatening key organisational objectives (Adams, 2002; Belal, 2002; Dey, 2002a; Gray, 2000, 2001; OÕDwyer, 2002; Owen et al., 2000, 2001). It has also been maintained that stakeholder empowerment can only evolve if institutional reforms enabling stakeholders to participate more directly in organisational decision making accompany these ÔnewÕ accounting processes (Adams, forthcoming; Owen et al., 1997, 2000, 2001; Owen et al., 2000; Owen et al., 2001). This paper responds to the aforementioned calls for richer, more in depth understandings of how and why social accounting processes emerge within organisations (Gray, 2002; Thomson & Bebbington, 2004). By presenting an in-depth examination of one social accounting process in action it also represents a rare attempt to empirically inform the suspicions surrounding the nature and extent of stakeholder involvement and empowerment within these processes. This examination was conducted using in-depth interviews with a broad range of participants in the process (including board members and internal and external stakeholders), internal memoranda and other documents, press releases, and observations recorded by the author while acting as a member of the audit review panel for the social account published from the process (see Appendix for further details surrounding the data collection and analysis). 1 1 Fifteen interviews were held over a fourteen month period with board members, operational managers, representatives from four of the seven stakeholder groups identified in the social accounting process, social accounting process facilitators and researchers, and members of the social accounts audit review panel. Within the case interviewees are identified as follows: B ¼ board member; M ¼ operational manager; IS ¼ internal stakeholder; ES ¼ external stakeholder. The case proceeds in a chronological fashion. Firstly, a brief outline of the nature of APSOÕs organisation is presented. The process through which social accounting was initially considered by APSO is then outlined. External pressures for greater accountability fuelling this choice are examined and conflicting/confused motivations regarding the key process objectives are exposed. An analysis of the dynamics within the stakeholder engagement process then ensues. This exposes tensions and flaws in the process involving issues such as stakeholder identification, stakeholder power, and stakeholder/management antagonism, all of which coalesce to deflate much of the initial optimism among key drivers of the process. The APSO boardÕs belated entry into the process at the account construction stage is subsequently scrutinised. Here, we observe the boardÕs assertion of authority over the social account presentation which acts to undermine the core ‘‘accountability’’ motives driving some of the internal promoters of the process. The case proceeds to examine the perceived absence of post account reflection and action by the APSO board and management in response to stakeholder concerns raised in the account. The change-resistant nature of the board, in contrast to their published commitment to accountability and change, is thereby uncovered. The case concludes with a discussion of the key findings before making some brief policy recommendations. The case setting The Agency for Personal Service Overseas (APSO) is an independent agency operating under the aegis of the Irish GovernmentÕs Department of Foreign Affairs. It is a non-profit organisation focused on human development, operating as part of IrelandÕs international co-operation programme with so-called developing countries and is funded by an annual grant-aid from IrelandÕs bilateral aid allocation. 2 The Agency was incorporated in 1974 2 Grant aid in 2001 totaled approximately €14 million. B. O’Dwyer / Accounting, Organizations and Society 30 (2005) 279–296 and until recently its mandate remained unchanged as outlined in its mission statement: The mission of APSO is to contribute to sustainable improvement in the living conditions of poor communities in developing countries by enhancing human resources, skills, and local capacities in the interests of development, peace and justice (APSO, 2000, p. 4). The Agency pursues this mission by enabling skilled people from Ireland and developing countries to transfer and share skills and knowledge and by supporting organisations and communities in developing countries to work towards self-reliance and sustainability. It provides funding and training services to Irish and international non-governmental development agencies for their personnel. APSO responds to skills needs in: education; health; administration; technical areas; and social science and agriculture. As part of its support of development outside Ireland it has become actively involved with local non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and community development initiatives. The Agency has a separate chairperson, chief executive and company secretary. An eleven member board of directors is appointed by the Irish Government Minister for Foreign Affairs. They meet approximately six times a year and serve in a voluntary capacity. The AgencyÕs head office in Dublin employs 32 individuals. The initial elevation of social accounting in APSO Perceived pressure to learn about APSO’s ‘performance’ With the instigation of a new board in 1995, there was pressure to engage in some soul searching regarding APSOÕs role and performance. It appears that the organisation (through the board) needed some reassurance as to its ‘‘performance’’ to satisfy both external (governmental) and internal (board) constituents, particularly with increased governmental funding coming on stream for IrelandÕs foreign aid pro- 281 gramme. The Minister for Foreign Affairs also wanted APSO to contribute to the development of criteria for measuring the effectiveness of the foreign aid programme. 3 One board member discerned a general ‘‘rise in requirements for accountability and transparency’’ (B1) which meant that in future APSO would have to ‘‘justify itself’’ (B1) given ‘‘question marks [which were being raised] about the viability of [APSO] placing personnel overseas to work on development projects’’ (B1). In effect, APSO was now going to have to ÔaccountÕ for its ÔperformanceÕ in some explicit manner. Given the specific nature of APSOÕs work and the difficulties inherent in measuring what it did objectively, the need for some form of qualitative, subjective ‘‘participatory’’ (ES1), and accountable assessment was widely perceived: [The Board] were looking for a way of assessing APSO on a qualitative basis because what APSO does is hard to measure. . . you can say Ôwe sent ten aid workers out to GambiaÕ but you canÕt actually measure [their impact]. . . itÕs tough to do. (IS2) The Board was finding it quite difficult to get a handle on how do we represent what the agency does, the overall quality of the agency and its work. . . Given the rise in requirements for accountability and transparency, we envisaged someone asking: is APSO any good anyway? (B2) External consultants were commissioned by the board to examine the quality assessment models available. The board publicly stated that they required a model enabling ‘‘self assessment, organisational learning and improvement’’ (APSO, 1998, p. 6). They eventually decided that the production of some form of social account would help achieve these objectives. After a tendering process, an external consultant with experience developing a 3 This information is gleaned from internal board meeting memorandums and communications between board members as well as interviews with board members and internal stakeholders. 282 B. O’Dwyer / Accounting, Organizations and Society 30 (2005) 279–296 seminal social accounting process was appointed to oversee the account production. The social accounting process adopted (as outlined in Table 1) closely followed the relatively sophisticated model adopted by Traidcraft Exchange (see Gray et al., 1997, pp. 344–347), a sister organisation of Traidcraft plc, the UK Third World Fair Trade organisation. Traidcraft plc published the first independently audited set of social accounts in 1993 and has consistently represented the ‘‘cutting-edge’’ of social accounting practice in the UK (Dey, 2000, 2002a, 2002b). This practice is built around the notion of polyvocal citizenship introduced by Gray et al. (1997). A polyvocal citizenship perspective (PCP) focuses on stakeholder dialogue ‘‘providing each of the stakeholders with a ÔvoiceÕ in the organisation’’ (Gray et al., 1997, p. 335). Stakeholder groups identify their key issues of concern and the emerging social account primarily reports their voices. A seven step process was adopted by APSO and focused on identifying key stakeholders and ascertaining their assessment as to how the organisation fulfilled its objectives 4 (see Table 1). As with Traidcraft Exchange, the process was subject to an external audit by a financial auditor. One manager and another external consultant (the Ôinternal championsÕ) were appointed to promote the process within APSO and to provide ongoing support to the social accounting consultant. The external consultant acting as an internal champion had been heavily involved in the initial search for a process to evaluate APSO and was the individual who first presented the possibility of adopting social accounting to the board. The board publicly stated that the process would enable APSO to ‘‘measure and account to its stakeholders the extent to which it ha[d] achieved its own objectives and realised its values’’ (APSO, 1998, p. 42). 4 As part of the process, the identified stakeholders were also asked to identify the criteria by which they believed APSO should be evaluated. Confused board expectations of the social accounting process While there was a definite desire among certain board members, especially the chairman, to instigate some form of evaluation process within APSO, there seems to have been little clarity of purpose internally regarding exactly what form the social account would take and how it would impact on APSOÕs ongoing operations. The internal champions sensed that some board members ‘‘didnÕt have a clear vision of what they wanted’’ (M2) and that ‘‘APSOÕs CEO was edgy about the process’’ (M1). One board member admitted that the full implications of implementing the process were not fully thought through. Indeed, in correspondence prepared by the board in response to the eventual publication of the social accounts the board complained about the process not being easily understood. I suppose, naively, at the back of my mind I had an idea that perhaps the social accounting process would be at least a step in the right direction towards some form of change, in terms of some consistency to what we were doing, also giving us an overall picture rather than a few sort of hit and miss looks at various things in different countries. (B3) Some form of evaluation or ÔaccountingÕ mechanism was deemed necessary but board control of the process was an implicit assumption among many members. It was an example of people putting forward proposals as to how to do things and somebody else not being able to think of any good reason to object. (B3) This uncertainty led to divergent expectations of social accounting among board members, many of whom already had a fractious relationship with one another due to business and development world philosophies clashing regularly at meetings. Several stakeholders (both internal and external) contended that while ‘‘one or two’’ (IS3) board members seemed committed to a process of open B. O’Dwyer / Accounting, Organizations and Society 30 (2005) 279–296 283 Table 1 Key elements of the APSO social accounting method adopted 1. Establish the value base What are the social objectives and ethical values against which APSO will measure its performance? 2. Define the stakeholders Who are the key groups of people who can influence or are influenced by APSOÕs activities? 3. Establish social performance indicators Stakeholder participation in determining the appropriate indicators for measuring APSOÕs performance is required 4. Collect the data Use of interviews, externally facilitated discussions, postal questionnaires, monitoring media responses, and independent opinion surveys 5. Write/construct the accounts The social accounts will be prepared and written by APSO. This is analogous to the practice in financial accounting 6. Submit the accounts to independent external audit A financial auditor is appointed to head the process. Will apply general auditing standards to determine if the accounts are relevant, understandable, reliable, complete, objective, timely, and consistent, and whether in his opinion, they give a true and fair view of APSOÕs ethical performance and impact on its stakeholders in the period reviewed by the accounts 7. Publication The social accounts report, including the auditorsÕ report is published and distributed to all key stakeholders Source: APSO (1998, p. 42). dialogue with stakeholders centred on contributing to some form of organisational change, most members perceived the process as a legitimation exercise focused on maintaining the status quo: I think maybe it was a core objective that we would be going through a process which would represent APSO as being a viable, healthy organisation at the end of the day. I donÕt think it was envisaged that any of the Ôwarts and allÕ would really come up. I donÕt think that was really addressed initially. . . I donÕt think it was thought about. (M1) For example, one head office staff member commented that the underlying tension surrounding the process motives meant that initially ‘‘there was not any great leadership in the process [at board level]’’ (IS4). He contended that for some board members the process was perceived as enabling the board to publicly present APSO as being committed to evolving and learning from its ÔstakeholdersÕ while in reality there was ‘‘no genuine desire to learn’’ (IS4). The maintenance of the legitimacy of APSOÕs operations in the eyes of the Department of Foreign Affairs was deemed the primary objective. I think it was seen as a positive exercise by some members, as a way of presenting APSO as. . . being a learning organisation. (B3) Discussions around the process at board level aggravated tensions between board members with business and development backgrounds. One of the internal champions felt that business members were overly focused on pushing their own experiences in commercial organisations, which she felt was highly inappropriate as they viewed the process as a crude control mechanism. For her, they were concerned with ‘‘evaluation’’ while social accounting was concerned with ‘‘accountability’’: I remember thinking, Ôthis is all very vagueÕ and nobody had any vision and they were all talking about their own organisations, going on like Ôthis is how we do evaluations, and this is how we do everything elseÕ. . . and 284 B. O’Dwyer / Accounting, Organizations and Society 30 (2005) 279–296 I remember thinking, this [social accounting] is very different, it isnÕt quite evaluation. . . they had never heard of social accounting. (M2) Internal championing of social accounting as an accountable organisational change mechanism The internal champions were much clearer about the role of social accounting. They were excited and optimistic due to their perception of its potential to bring about some ‘‘badly needed change’’ (M2) within APSO. The internal champion who had initially suggested the process to the board felt it was ‘‘philosophically’’ right for the organisation: I felt that the process could. . . [help]. . . APSO reinvent itself and stimulate thought about where we [we]re going, and what we [we]re about. . . I thought this would be a good way of seeing what needed to be done [using] a strong voice from [our] stakeholders. . . in a qualitative way. . . and it was very much that it was a qualitative methodology. . . as I come from that way of thinking. (M2) Well, I would have been quite excited and idealistic. . . I was optimistic, if you like, that this was an opportunity to present a Ôwarts and allÕ picture. (M1) a clear idea of what the stakeholders wanted. And that it was a very fair way of introducing change into the organisation. Now I would have to be honest and say that I also felt that APSO needed change. (M2) I had this vision. . . that everybody would be involved, it would be a very dynamic thing . . . that all the people in APSO with different baggage would come together in this process. . . I actually had a vision of them all working together. . . And this would be a way of involving the staff in the process of change within APSO. . . I have to be straight about that, I do see social accounting as a means of bringing about change. (M3) Whatever the tensions surrounding the motives driving the process, the subsequent publication of the reasons for selecting social accounting were unambiguous. A commitment to creating an open and accountable dialogue with all key stakeholders regarding the organisationÕs performance against its stated mission and objectives (as well as objectives to be specified by the stakeholders consulted) and the facilitation of change based on this dialogue was explicitly promoted (see Table 2). The evolution of stakeholder ‘‘dialogue’’ Several operational managers and other internal stakeholders spoke of the initial infectious energy behind the process and the impression that it was innovative given APSO was apparently expressing a commitment to learning from ‘‘people on the ground’’. Some praised the boardÕs ‘‘bravery’’ as there was an underlying sense that latent frustration among stakeholders would be allowed to leap forth into an account committed to bringing about change. This initial positive view was aided by the internal championsÕ commitment to making the process work for APSOÕs stakeholders: I felt social accounting was really going to consult with stakeholders. And then you had Stakeholder selection––denying key external ‘‘voices’’ The initial stages of the process focused on identifying APSOs key stakeholders (see Table 1). However, early in the process widespread concern emerged due to a failure to identify local communities in developing countries (or their representatives) as key stakeholders. While the engagement process involved consultation with service providers who were directly provided with assistance by APSO it deliberately excluded the ‘‘the key people in the village[s] or in the hospital[s] in developing countries’’ (M2). Hence, key stakeholders, if not the key stakeholders without a voice B. O’Dwyer / Accounting, Organizations and Society 30 (2005) 279–296 285 Table 2 The APSO boardÕs publicly expressed motives for instigating the social accounting process It focuses on the qualitative aspects of the work of the organisation It identifies and consults all the stakeholders Stakeholders define the performance indicators It is transparent It will be published All staff members will be involved––it is not for management only, every staff member is actively involved in the process It facilitates change––all are involved in learning It relates to all aspects of the organisation Source: APSO (1998, p. 6), emphasis added. prior to the instigation of the process remained unheard and were therefore denied any possibility of participating in or influencing any form of transformation in their relationship with APSO. The stakeholders identified were ÔconvenientÕ, there was no attempt to address the concerns of the people on the ground in Africa, those being taught in various areas, the Africans themselves. (ES1) They [the local communities in Central Africa] are who we are trying to empower to build their organisations and build their capacities and make them sustainable so. . . they should be the main stakeholder. (IS4) One operational manager was incensed with what she perceived as a ‘‘quality brainwash’’ (IS2) which overtook the process focusing on the voices of various agencies and NGOs while appearing to have little concern for the voices of the local people she felt APSO was supposed to serve. I remember saying to a lot of quality people initially, Ôhow do you get the voice of the person on the north bank in the river Gambia. . . where do the people in the village come into the scene. . . the people who actually benefit from the work of APSO? (IS2) When the board became aware of this, some members were alarmed and expressed their reservations to the social accounting consultant. The board were. . . concerned that we must get to the key stakeholders at the end of the day and the key stakeholder is the person in the developing country. (B2) This issue caused severe tension between the board and the consultant with the latter writing to the board seeking to reassure them by indicating that as APSO did not have a ‘‘direct’’ accountability relationship with local people on the ground in developing nations they did not need to consult them. Effectively, he argued against identifying the final recipients of APSOs services as stakeholders. The board remained unconvinced but resisted interfering in the consultantÕs work for fear, according to one board member, of being perceived as attempting to dictate the ongoing consultative process. A flawed ‘dialogue’––power relations, mistrust and cursory ‘consultation’ The ensuing dialogue with identified stakeholders was severely criticised by those involved. For many, APSOÕs ‘‘unremitting power’’ over its stakeholders operating in developing countries rendered the pursuit of an open, critically focused dialogue impossible. It was repeatedly highlighted by interviewees that as most of APSOÕs key stakeholders were totally dependent on APSO for assistance and resources they were unlikely to engage in a process where they might criticise and potentially alienate ‘‘the only hand that feeds them’’ (IS1). Hence, the process was accused of failing to ‘‘deal adequately with the power asymmetries involved’’ (ES1): 286 B. O’Dwyer / Accounting, Organizations and Society 30 (2005) 279–296 A number of sending agencies are absolutely dependent on APSO for funding, they are not going to say something thatÕs going to cut off their nose to spite their face. . . Also, the beneficiaries, including the local organisations,. . . even if they had question marks about the usefulness of the skills of the development workers being recruited they will not complain as they depend on them. (ES3) There is that power relationship between the funder and the funded and the extent to which people feel that they can criticise is severely compromised. . . overseas partners will [therefore] tell you what you want to hear. (ES2) Furthermore, there was widespread resistance to engagement by internal stakeholders. An antagonistic relationship pervaded between certain head office staff and APSO management and there was ‘‘a lot of distrust [of management]’’ (IS5). Many head office staff complained of an embedded management myopia prior to the inception of the social accounting process and they openly questioned the publicised motives surrounding it. Hence, they had little faith in the process as a means of instigating change and felt that there was little to be gained from their participation. This severely restricted the potential for open dialogue with these stakeholders with just ‘‘over 50 per cent of the head office staff respond[ing]’’ (M2) to questionnaires issued: There was a cynicism among staff regarding the actions of management in APSO and their motivation for the process. . . the response rate was very low. (M2) One senior staff member was particularly animated. He castigated in rather intemperate language what he saw as the dubious motives for the process. For him, it was merely aimed at political constituencies in the Irish government who had the power to change APSOÕs remit and smacked of a cynical legitimation exercise concerned with preventing as opposed to facilitating change. This absence of trust destroyed any possibility of a ‘‘constructive’’ interchange between the consultant and internal champions, who were perceived as representing the board, and head office staff. The capacity of the consultative process to encourage meaningful dialogue between the organisation and its stakeholders was continually criticised by the stakeholders interviewed. Many felt the dialogue was restricted by primarily exploring perceptions as to how APSO fulfilled its mission and objectives, however defined. One external stakeholder felt this ‘‘tend[ed] to limit the potential for exploring new ideas’’ (ES2) as problems stakeholders may have been interested in discussing could not be considered. There was a perception among some stakeholders that the consultant ‘‘rushed’’ the consultations and produced ‘‘homogenised’’ questions which were often totally inappropriate for different stakeholder groups, particularly given the cultural differences encountered. Many stakeholders did not feel ‘‘involved’’ enough in the process: If the process was a vibrant dynamic process it would have involved the stakeholders on a more long term basis. . . not just one consultation and one questionnaire that you filled out in twenty minutes. . . they [stakeholders] should be involved and have a right to poke their noses in as to where the results were going and what was being done. . . I saw it as a dynamic process that didnÕt just happen and then end. (M2) Several stakeholders complained they had little opportunity to engage in dialogue with each other. It was widely claimed that stakeholders needed to learn from each other across the organisation as opposed to merely enabling the board to learn from them and then isolate them. The information flows were only going one way, from the stakeholders to the board, with little apparent prospect of a two-way dialogue emerging: Ideally social audit 5 should be about the organisation learning and organisational learning means throughout. . . For that to 5 Note that many interviewees referred to the social accounting process as ‘‘social audit’’. B. O’Dwyer / Accounting, Organizations and Society 30 (2005) 279–296 happen I think you would need to have some of the relevant people at different levels meeting with their relevant stakeholders for their level. . . staff people not only management level. (IS2) The production and management of the social account The production of the initial social account was undertaken in a hurried manner under pressure from the board. They began to feel alienated from the process especially when they realised that the consultant had not identified them as stakeholders. Immediately, they changed from a passive observer of the stakeholder engagement process, evidenced in their earlier reluctance to interfere when concerned about stakeholder identification, to an active participant in the social account production. Asserting board authority over the social account The board began to take a more active critical role in the process prior to the preparation of the first account draft. While one board member felt that ‘‘the symbolism of the board not getting involved initially was important for the process in general’’ (B1), this hesitancy gave way to concerns that they were left without a voice in the ongoing dialogue. Many board members could ‘‘not get [their] head[s] around why they werenÕt considered a stakeholder. . . they wrestled with this over and over again and could not figure out what role they had within [the process]’’ (B2). Some felt their involvement was crucial in order to provide a balance to the perspectives being considered. There was a general view that they had ceded too much control to the consultant and the internal champions: We were not getting enough information. . . [and] as we got information there was a sense Ôsurely all of this is about balance and where is the balance?Õ The board can be an element in the balance. . . it might have been given a voice as just another stakeholder and that might have had a balancing element. (B3) 287 The consultant was summoned to formally address the board to reassure them of the progress of the process and in particular to explain to them why they had a non-participatory role in the initial stakeholder dialogue. He reminded them of the model they had formally approved and claimed they could not interfere with its implementation without threatening its credibility: I think they [the board] were more or less beaten into submission in the end. . . it added to the confusion the board had regarding the process and what to do about it. (M1) Eventually, in order to alleviate the festering concern, a board subcommittee was formed to receive and comment on the initial account draft: It was a bit late in the staged process that was being worked through that the board decided to set up a committee to receive the output of the exercise. . . there was some concern about the apparent sidelining of the board in the process. . . you were being told there was a model and an approach and you couldnÕt start affecting the methodology. (B2) Seeking to influence the social account The board subcommittee put ‘‘pressure. . . on to deliver an early draft of the accounts’’ (M1) and this created further tensions between the board and the consultant and internal champions. A draft was ‘‘poorly prepared. . . under duress’’ (M2) and submitted but ‘‘most [board members] found [the content] totally confusing’’ (B2). The nature of the initial draft surprised and shocked many board members. There was significant unease with the subjective nature of the reported perspectives despite this being a key reason for initially selecting the process. It was widely perceived that ‘‘. . . the agenda appeared to have been too big’’ (B2). Some board members had met other international aid body leaders at conferences and these individuals had expressed concern that APSO risked ‘‘being torn to shreds’’ (B1). 288 B. O’Dwyer / Accounting, Organizations and Society 30 (2005) 279–296 The board had expected to get more feedback on the impact of what we [APSO] are doing and the objective impact of what we are doing rather than peopleÕs impressions on what was happening. (B2) The overly negative nature of the perspectives caused particular unease. APSO came in for heavy criticism from some stakeholder groups. Many board members were not prepared for the sheer extent of this exposure of stakeholder concern. Their published desire for a ‘‘warts and all’’ report did not anticipate such open hostility: The Board had not fully considered the possibility of what the process might throw up. . . There was quite a bit of shock [among the board] in the social audit process in that there was a lot of negativity coming back at them. . . [For example,] there was a fair amount of frustration among development workers. (B3) The board subcommittee felt compelled to force their way into the process in order to influence the nature of the reporting of stakeholder voices. They met the consultant and internal champions and demanded that the social account be re-written: They threw it [the draft] back at us and said Ôthis is a load of garbageÕ. . . They were perfectly right. . . it was a complete mish mash of statistics and figures. (M1) Underpinning their anxiety was the consultantÕs reminder that by committing to the complete process, they had consented to the account being published externally. Some members were extremely reluctant about ‘‘sign[ing] off’’ on the account and a heated debate ensued. Many were worried that ‘‘somebody whose interests l[ay] elsewhere c[ould] manipulate th[e] information and use it for whatever reason’’ (B2). The internal champions felt betrayed by this turn of events: A few things popped up regarding whether the document should be published or not, whether it should be internalised which defeated the whole process in my view. (M1) Perceived manipulation and control of the social account The boardÕs interference became common knowledge among certain internal and external stakeholders and they felt aggrieved. One stakeholder claimed that ‘‘management put their own spin on the results [of the dialogue]’’ (IS5) and accused them of suppressing some of the more critical perspectives. 6 This perception alienated many stakeholders and further highlighted the mistrust of management that persisted among some stakeholder groups: A first draft of the social accounts came out and then a second draft. . . there was quite a strong degree of dissatisfaction that it had been sanitised from draft 1 to draft 2. (ES2) Management probably controlled the wording. . . looked for negative stuff and then downplayed it to an extent. . . major critics were only cursorily addressed. (ES1) The boardÕs attempt to wrest control of the account escalated during the audit review process instigated prior to account publication. One external stakeholder claimed that the audit review panel was carefully selected so that the process of approving the final account could proceed without any major challenges. Another claimed she was deliberately dropped from the audit review panel. She was extremely angry and insisted that this was a deliberate way of excluding a critical voice from the process as she might raise serious questions about its integrity and refuse to ‘‘rubber stamp [the report]’’. Much to my surprise and to many othersÕ surprise. . . I was removed from the process. I was 6 Correspondence examined indicates that one chapter of the initial draft of the social accounts was excluded from the final draft on the advice of the board as they deemed it to be more akin to advisory data to the board on APSOÕs information systems. B. O’Dwyer / Accounting, Organizations and Society 30 (2005) 279–296 one of two trained social auditors in the country. . . it was extraordinary. (ES5) Other audit review panel members were also unhappy with the boardÕs evident control over the process at this final stage. The focus on process detail as opposed to more substantive issues surrounding the findings at the audit review panel meeting troubled some members. Furthermore, others expressed surprise and suspicion at being called into the process at such a late stage. Indeed, the external auditor referred to this in his subsequent management letter to the board. It was fairly obvious there was some board agenda surrounding the [audit review] process. (ES3) It was initially suggested at the review panel meeting that the external auditorÕs report be addressed to the board (i.e. not the identified stakeholders). Some members of the review panel (including the author of this paper) strongly objected to this given the purported objective of the process was for the board to account to the stakeholders and not vice versa: At the external review panel meeting. . . as far as I can remember, initially our report was going to be addressed to the board. I said Ôlisten you might as well forget the whole process if you are going to do this because it is a report. . . to the stakeholdersÕ. (ES6) It was evident at this stage that the external consultant was now almost exclusively acting on the instructions of the board subcommittee and the board had taken effective control of the account presentation. The black hole––substantive feedback deficiency Feedback to stakeholders post account publication was crucial if any change in how APSO dealt with its identified stakeholders, which management publicly claimed the process was about, was to ensue. While they did wrest control of the account, 289 the board still allowed many negative perspectives to be reported. The role of the external auditor in ensuring this occurred was crucial. However, there was a widely perceived absence of board commitment to embedding a two-way dialogue with stakeholders regarding potential changes that could arise from acting on the account content. Repeated reference was made by both internal and external stakeholders to the stakeholder perspectives disappearing into a ‘‘black hole’’ never to emerge for substantive consideration or further consultation which might facilitate some challenges to the status quo in APSO. One staff member claimed the ‘‘board were very defensive and did not take the accounts very seriously at all’’ while ‘‘they were taken more seriously by staff’’ (IS2) and other stakeholders who had contributed as they were keen for some form of change. Several stakeholders claimed they learned little about how APSO proposed to instigate change on their behalf and felt this reflected an ‘‘accountability deficiency’’ (IS4) in the process. The results could have brought about change through [continuing] dialogue but they werenÕt really taken on board, they were taken on board superficially. It didnÕt challenge enough. (ES2) While the idea is good, while it is adventurous, while it is representative of a forward thinking organisation concerned with stakeholders, without ongoing dialogue it doesnÕt actually change anything. People can say they have done something but actually nothing happens. (IS2) Certainly from how I thought about it [social accounting] from when I set out. . . it failed. And that would be one of my big questions about social accounting, is that you can actually go through the process, because I have now gone through it, and it hasnÕt challenged. (M2) The aforementioned mutual mistrust between many staff members and management was seen to 290 B. O’Dwyer / Accounting, Organizations and Society 30 (2005) 279–296 have influenced this poverty of managerial feedback. Several interviewees felt the ‘‘embedded’’ communication difficulties within APSO were reflected in the lack of substantive feedback. For the board, publishing the account seemed to have constituted the key ÔeventÕ as opposed to responding to its contents on an ongoing basis. [There was] very poor communication in APSO anyway and the accounts came out and there was a lack of feedback and a lack of reaction which made staff even more angry and more cynical. (M1) It hasnÕt made this organisation a better organisation. . . and issues, for example, around internal communication, around staff appraisal have not changed, so I would be quite disillusioned [with the process]. (IS4) When challenged in their interviews, some board members conceded that feedback could have been better given ‘‘it was unsystematic [and] a little bit haphazard’’ (B2). However, one member insisted that ‘‘feedback was not ignored’’ (B1) and that efforts were made to address some concerns addressed in the accounts. Given a commitment had been made to undertaking the process a second time he claimed there was a sense that ‘‘weÕd better make sure that something [i]s done in the meantime’’ (B1). 7 A whole range of changes did take place. . . we looked at all the systems, how people are handled from the time we recruit them to the time we finish up with them, all those systems were reviewed and we went back on them again to see to what extent the change was implemented. (B1) 7 APSO undertook a much more focused and ‘‘cost-effective’’ process three years later. A social account was produced in draft form but this has never been published. External strategic reviews by consultants and a new strategic plan superseded its contents. Another board member commented that while the process ‘‘alert[ed] the board to the need for responding to feedback’’ (B3), acting on this was problematic given the nature of the method chosen. This was a constant refrain among board members when discussing the perceived absence of feedback. There was a sense that while they wanted to measure the qualitative nature of APSOÕs performance the data produced was perceived as too ‘‘soft’’ to act upon: The [social accounting] methodology hasnÕt moved on as far as I can see, so we found it difficult to get a handle on what we should be doing as a result of this [process] that will improve the system. . . Nobody [wa]s ever asked Ôokay you donÕt like that but what do you want to be different or what are you prepared to do differently? (B1) ItÕs easier for business with its more narrow focus to instigate a process such as this. . . the process doesnÕt suit APSOÕs objectives. (B2) The demolition of the initial internal championsÕ optimism was now apparently complete: At the end of the day, social accounting is only as good as the organisation thatÕs using it. Because in fact APSO didnÕt change because of social accounting. All APSOÕs bad ways and bad habits, and lack of systems and structures and organisation and all of that are all the same as they were in the beginning. And it didnÕt do any of the things that I wanted it to. To be blunt it didnÕt challenge, it didnÕt bring about change and it didnÕt rattle. Now that is partly to do with the methodology, partly the board, and the consultant. (M2) Discussion and conclusions This paper presents a case study of the evolution of a social accounting process in an Irish overseas aid agency, the Agency for Personal B. O’Dwyer / Accounting, Organizations and Society 30 (2005) 279–296 Service Overseas (APSO). The case examines how and why a social accounting process evolved within APSO. It specifically responds to calls for richer, more in-depth understandings of how and why social accounting processes evolve within organisations (Gray, 2002; Thomson & Bebbington, 2004). Much of the corporate rhetoric surrounding social accounting processes simplifies their complex nature and tends to downplay many concerns as to how they can achieve ÔrealÕ organisational change on behalf of stakeholders (see Owen et al., 2001). The case exposes this complexity by illuminating the contradictions, tensions and obstacles that permeated one such process. In doing so, it provides rare empirical support for the suspicions expressed in the social accounting literature regarding the nature and extent of stakeholder involvement and empowerment within these processes (Belal, 2002; Dey, 2000, 2002a; Owen et al., 2001; Owen et al., 2001; Thomson & Bebbington, 2004; Unerman & Bennett, 2004). The core of the case illuminates a systematic process of stakeholder silencing by a powerful APSO board whose agenda for the process differed significantly from those of its promoters. This prevented the process empowering key stakeholders to institute substantive organisational change. A coalition of factors emerged in the case to support this conclusion. For example, conflicting and confused perceptions of the process objectives among board members prevailed with most exhibiting little concern to empower stakeholders. The nature of the stakeholder identification and consultation process was fundamentally flawed and deliberately excluded key stakeholder voices. There was an absence of firm board commitment to acting on stakeholder concerns evidenced in their resistant response to the emergence of critical stakeholder voices in the initial social account draft. More fundamentally, the extent of APSOs power, through the board, over its key stakeholders denied the possibility of any comprehensive discussion of APSOÕs impact on these stakeholders. Finally, the absence of any governance mechanisms designed to empower key stakeholders post account publication indicated scant regard for acting on those voices that were represented in the account. 291 Extreme power relations between key stakeholders and the APSO organisation negated the potential for stakeholder empowerment. The boardÕs attempt to control the account presentation contradicted their initial concern, expressed to the consultant, to hear the voices of key developing world stakeholders. This expression of unease did not, however, imply a commitment to acting in response to these voices. Given the extent of the power APSO held over these stakeholders the board could easily have ignored their concerns. Furthermore, given this power relationship, it is debatable whether the stakeholder voices would have provided any substantial evidence of stakeholder desire for change. For example, stakeholders in developing countries who were consulted were totally reliant on APSO for assistance and, moreover, had no formal avenues through which they could attempt to influence APSOÕs governance and executive decision making. Hence, even if critical viewpoints were expressed there was no formal mechanism through which these voices could be empowered. Owen et al. (1997) and Owen et al. (2001) have alluded to this absence of supporting institutional mechanisms to empower stakeholder voices more generally in social accounting practice and the evidence here supports their perception of the need for institutional supports for stakeholders in these processes. In this instance, the board was able to downplay critical stakeholder voices in the account and rationalise this internally by blaming flaws in the social accounting methodology they had approved. Once the board assumed control of the account, key stakeholders (and the internal champions and consultant) were powerless to resist. These findings provide some support for the suspicions of Owen et al. (2001) regarding the oft promoted ease with which stakeholder engagement mechanisms can provide mutual stakeholder/organisational benefits (see also, Belal, 2002; Dey, 2000, 2002a; Gray, 2000, 2001; Thomson & Bebbington, 2004). Owen et al. (2001) suggested that the power organisational interests are able to bring to stakeholder engagement exercises often implies they inevitably come to control the dialogue agenda (see also, Thomson & Bebbington, 292 B. O’Dwyer / Accounting, Organizations and Society 30 (2005) 279–296 2004). They bemoan the absence of any consideration of this dimension in the promotion of social accounting practice. In this case, the absence of any two-way exchange between APSO and its stakeholders and the power relationships involved ensured that the dialogue (as well as the reporting of the dialogue) was controlled by management. If stakeholder empowerment is to be a key feature of these processes, then this case indicates how vital consideration of this power dimension is to the design and implementation of ÔtrulyÕ accountable processes. Stakeholder/management mistrust and, in some cases, antagonism also emerged to disrupt the process. Stakeholder resistance to engagement was fuelled by embedded mistrust of the board and management among head office staff and many development workers. For them, the process was always vulnerable to board/managerial influence. Its publicised ÔaccountabilityÕ motives contrasted with their experience of persistent communication difficulties with APSO management. This suspicion was heightened when word of the board subcommitteeÕs influence on the final account became common knowledge. The contrast between the published objectives and the boardÕs eventual active resistance to substantive change instigated by the process further fuelled these concerns and illuminates a resistance to empowering stakeholder voices. Owen et al. (2001) and Gray (2001) have consistently questioned whether organisations are willing to accept the degree of ÔhurtÕ necessary to produce ÔtrulyÕ accountable social accounts. In this process, there was little openness to ÔhurtÕ and an account was produced that appears to have had little significance for the lives of many stakeholders despite its publicly stated commitment to transparency, accountability and stakeholder engendered change. This case demonstrates that unless some formal empowerment of stakeholder groups is permitted, organisational managers can easily emasculate social accounting processes and displace a purported commitment to accountability with effective control of stakeholder voices. In order to compel management to commit to acting on key stakeholder voices mechanisms by which these voices can be incorporated into corporate decision making need to evolve (see, Owen et al., 1997; Owen et al., 2001). Many of the key stakeholders in APSOÕs process had no formal mechanism through which they could be ensured their voice would influence decisions impacting directly on their lives. The ÔaccountÕ of their voices, where this was obtained, was also open to manipulation if it disturbed the status quo. The power the board possessed to undermine the delegated authority of the consultant, the internal champions and the internal audit review panel members was subject to no countervailing force. Not only were the stakeholders unable to ensure their voices were heard, the perceived absence of feedback indicates a lack of willingness on the part of APSO management to embed the stakeholder engagement process on an ongoing basis. This case, albeit related to one specific setting, provides critical evidence of how a conception of social accounting can be emasculated by management and designed to serve organisational as opposed to broad stakeholder interests. It indicates that there is an urgent need for further sustained critical examinations of the operation of these processes, especially in the corporate world, in order to assess the degree to which they actually facilitate stakeholder empowerment. These studies should shed more light on widespread claims to accountability and indicate how practice should evolve in order to challenge rather than conceal organisational impacts on stakeholder groups. Research of this nature can contribute to the development of social accounting processes which begin to reflect democratic dialogues between organisations and stakeholders focused on empowering stakeholders to bring about some form of stakeholder induced organisational change. Acknowledgements The assistance of Mike Greally, Programme Manager, APSO was invaluable throughout the data collection phase of this study. I would like to express my extreme gratitude to him for this. I would also like to acknowledge the invaluable comments of Amanda Ball, Jan Bebbington, Rebecca Boden, Colin Dey, Linda English, Rob Gray, B. O’Dwyer / Accounting, Organizations and Society 30 (2005) 279–296 Richard Laughlin, Hugh McBride, Dave Owen, Ian Thomson, Carol Tilt, Jeffrey Unerman and the anonymous reviewers for Accounting, Organizations and Society. Comments from participants at a research seminar in The Management Centre, KingÕs College, University of London, the 2002 Critical Perspectives on Accounting conference, New York, the 2002 Irish Accounting and Finance Association conference, Galway, the 2002 Financial Reporting and Business Communication conference, Cardiff, and the 2002 International Congress on Social and Environmental Accounting, Dundee are also greatly appreciated. The financial assistance of the Irish Accountancy Educational Trust is warmly acknowledged. Appendix Research method The case was constructed using a number of evidential sources. These included: in-depth interviews; internal memoranda and other documents; press releases; publicly available information and documents on APSOÕs mission and strategic objectives; media reporting on the social accounting process in APSO and on APSO generally; and observations recorded by the author while acting as a member of the audit review panel for the social account published from the process. In-depth interviews Fifteen interviews, primarily of an in-depth nature, were held over a fourteen month period commencing in September 2000. Chiefly for logistical reasons, five of these interviews were held by telephone. This was mainly as some of the interviewees worked on overseas assignments for APSO in Central America and Africa and this was the only available means of directly communicating with them. Time constraints for certain other interviewees also made phone interviews most efficient from their perspective. Interviewees were selected from a broad range of constituencies associated with the social accounting process in APSO. These encompassed board members, 293 operational managers, representatives from four of the seven stakeholder groups identified in the social accounting process, social accounting process facilitators and researchers, and members of the social account audit review panel. 8 I had hoped to interview members of all stakeholder groups but this did not prove possible, hence, there was an element of expediency in the selection of stakeholder groups. However, I was very conscious that I needed to interview external stakeholders and different stakeholders within specific stakeholder groups, which I successfully achieved. A semi-structured interview approach was taken using broad open-ended questions in order to encourage the interviewees to participate in a loosely guided conversation (Maykut & Morehouse, 1994). This approach empowers interviewees, enabling them to speak in their own ‘‘voices’’ therefore increasing their propensity to ‘‘tell stories’’ and provide narrative accounts (Llewellyn, 2001). The interview guide focused in particular on obtaining perspectives on how and why social accounting had evolved in APSO (Lillis, 1999) in order to discover what was in and on the intervieweesÕ minds regarding the evolution of the process (Patton, 1990). While this imposed some structure on each interview, I was conscious to ensure that it was the intervieweesÕ perspectives I was gaining and therefore the interview guide was not used in an overly constraining manner (Patton, 1990). Interviews lasted from between one and two and a half hours. 9 A number of interviewees also provided follow up feedback subsequent to their interviews and this enabled clarification of some of the issues discussed. 10 Elements of this follow up included detailed written reflections on the social 8 The author was also a member of this panel. On some occasions I had to reassure interviewees that I was not working for anyone on a consultancy basis and that this was merely an independently minded academic enquiry. 10 During each face to face interview detailed notes were taken, and immediately after these interviews reflections on each interview were recorded on tape and subsequently written up. These reflections dealt in particular with the intervieweeÕs demeanour throughout the interview, covering issues such as rapport established, reaction to probing, apparent conviction in responses, inconsistencies in responses and general attitude to the research issue under study. 9 294 B. O’Dwyer / Accounting, Organizations and Society 30 (2005) 279–296 accounting process submitted to the author by participants in the process. Other sources of evidence The interview data was supplemented with additional evidential sources. Internal documentation reflecting the boardÕs response to the process as it evolved was also examined. This included, inter alia, correspondence reflecting the initial board consultations with the social accounting consultant; the boardÕs responses to various drafts of the social accounts; and the external auditorÕs management letter. Strategic planning documents, annual reports, the organisationÕs web site, submissions to the Irish GovernmentÕs Department of Foreign Affairs and draft social accounts subsequent to those emanating from the process examined here were also studied. Newspaper articles relating to APSO throughout the process were also collected and content analysed (see, for example, Holsti, 1969; Krippendorff, 1980; Weber, 1985) to obtain some sense of how the organisation was perceived externally. Evidence analysis Nine of the ten face to face interviews were recorded by tape and subsequently transcribed 11 (Jones, 1985). During all the unrecorded interviews detailed notes were taken throughout and were written up immediately after these interviews. Furthermore, immediate reflections and key issues from these interviews were also recorded on tape. The analysis of the evidence collected was primarily qualitative and iterative and constituted a continuous process throughout the study (see OÕDwyer, 2004). For example, during the interview collection phase ongoing analysis was aided by: extensive notes taken during and immediately after interviews; tape-recorded reflections on interviews; listening to interview tapes while travelling; and the recording of an inner dialogue reflecting on the interviews in a separate journal 11 One interviewee was very reluctant to be tape-recorded. (often termed a ‘‘theoretical memo’’) 12 (Baxter & Chua, 1998; Parker & Roffey, 1997). This, in effect, provided a provisional running record of analysis and interpretation prior to any formal evidence processing and interpretation (see, for example, Miles & Huberman, 1994; Tesch, 1990). After ten interviews had been conducted, the interview transcripts, notes and documentation collected were examined and re-examined in-depth over a two month period. As a result of this iterative process, they were coded into broad substantive themes encompassing a ÔstoryÕ or ‘‘thick description’’ (Denzin, 1994, p. 505; see also, King, 1998, 1999) of the evolution of the social accounting process. 13 Contrasting perspectives were highlighted and where necessary confirmation of perspectives was requested from participants in order to ensure that it was the perspectives of those being studied which were being presented (Atkinson & Shaffir, 1998). Subsequently, five more interviews were undertaken and extra documentation was collected over an extended period. After the passage of approximately three months, these interviews were formally analysed in conjunction with a second analysis of the initial ten interviews. This time gap allowed for some further reflection on the nature of the interpretation of the evidence collected. New themes and ‘‘competing interpretations’’ emerged within the overall ‘‘story’’ (Ahrens & Dent, 1998; Silverman, 2000). The case constructed from this analysis tells the ÔstoryÕ of the evolution of the process. References Adams, C. A. (1999). The nature and processes of corporate reporting on ethical issues. London: CIMA. Adams, C. A. (2002). Internal organisational factors influencing corporate social and ethical reporting: beyond current 12 In a sense, this involved ‘‘living’’ with the data, noting insights as they arose in my mind and constantly freeing my mind to be open to various themes emanating throughout the process. These notes effectively became my ‘‘memory’’ (Baxter & Chua, 1998) and also included insights challenging any preconceptions I may have held. 13 These substantive or ‘‘macro’’ themes brought together individual or ‘‘micro’’ themes identified during the analysis. B. O’Dwyer / Accounting, Organizations and Society 30 (2005) 279–296 theorising. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 15(2), 223–250. Adams, C. A. (forthcoming). The reporting-performance portrayal gap at ICI. ABACUS. Adams, C. A., & Harte, G. (2000). Making discrimination visible: the potential for social accounting. Accounting Forum, 24(1), 56–79. Agency for Personal Service Overseas (APSO) (1998). APSO Social Accounts report 1996. Dublin: APSO. Agency for Personal Service Overseas (APSO) (2000). APSO annual report. Dublin: APSO. Ahrens, T., & Dent, J. F. (1998). Accounting and organizations: realizing the richness of field research. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 10, 1–39. Atkinson, A. A., & Shaffir, E. (1998). Standards for field research in management accounting. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 10, 1–39. Baxter, J. A., & Chua, W. F. (1998). Doing field research: practice and meta-theory in counterpoint. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 10, 69–87. Bebbington, J. (1997). Engagement, education and sustainability: a review essay on environmental accounting. Accounting Auditing and Accountability Journal, 10(3), 365–381. Belal, A. R. (2002). Stakeholder accountability or stakeholder management?: A review of UK firmsÕ social and ethical accounting, auditing and reporting (SEAAR) practices. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 9(1), 8–25. Cotton, P., Fraser, I. A., & Hill, W. Y. (2000). The social audit agenda - primary health care in a stakeholder society. International Journal of Auditing, 4(1), 3–28. Dawson, E. (1998). The relevance of social audit for Oxfam GB. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(13), 1457–1469. Denzin, N. K. (1994). The art and politics of interpretation. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage. Dey, C. R. (2000). Bookkeeping and ethnography at Traidcraft plc: a review of an experiment in social accounting. Social and Environmental Accounting Journal, 20(1), 16–19. Dey, C. R. (2002a). Social accounting at Traidcraft plc: an ethnographic study of a struggle for the meaning of fair trade. Paper presented at the Social and Environmental Accounting Congress, University of Dundee, September. Dey, C. R. (2002b). Social accounting and the critical project: a note on the use of ethnography as an active research methodology. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 15(1), 106–121. Elkington, J. (2001). The Chrysalis economy: how citizen CEOs and corporations can fuse values and value creation. Oxford: Capstone. Gray, R. H. (2000). Current developments and trends in social and environmental auditing, reporting and attestation: a review and comment. International Journal of Auditing, 4(3), 247–268. Gray, R. H. (2001). Thirty years of social accounting, reporting and auditing: What (if anything) have we learnt? Business Ethics: A European Review, 10(1), 9–15. 295 Gray, R. H. (2002). The social accounting project and accounting organizations and society: privileging engagement, imagination, new accountings and pragmatism over critique? Accounting Organizations and Society, 27(7), 687– 708. Gray, R. H., Dey, C., Owen, D. L., Evans, R., & Zadek, S. (1997). Struggling with the praxis of social accounting: stakeholders, accountability, audits and procedures. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 10(3), 325–364. Hill, W. Y., Fraser, I. A., & Cotton, P. (1998). PatientsÕ voices, rights and responsibilities: on implementing social audit in primary health care. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(13), 1481–1497. Hill, W. Y., Fraser, I. A., & Cotton, P. (2001). On patientsÕ interests and accountability: reflecting on some dilemmas in social audit in primary health care. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 12, 453–469. Holsti, O. R. (1969). Content analysis for the social sciences and the humanities. USA: Addison Wesley. Jones, S. (1985). The analysis of depth interviews. In R. Walker (Ed.), Applied qualitative research. Aldershot: Gower. Kent, T. (2002). Conference report: business for social responsibility conference, 5–8 November 2002. Ethical Corporation Magazine. Online Version, http://www.ethicalcorp. com/ printtemplate.asp?idnum ¼ 451, Accessed 9 January 2003. King, N. (1998). Template analysis. In G. Symon & C. Cassell (Eds.), Qualitative methods and analysis in organizational research: a practical guide. London: Sage. King, N. (1999). The qualitative research interview. In C. Cassell & G. Symon (Eds.), Qualitative methods in organizational research: a practical guide. London: Sage. Krippendorff, K. (1980). Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Larrinaga-Gonzalez, C., & Bebbington, J. (2001). Accounting change or institutional appropriation?––A case study of the implementation of environmental accounting. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 12(3), 269–292. Lillis, A. M. (1999). A framework for the analysis of interview data from multiple field sites. Accounting and Finance, 39, 79–105. Llewellyn, S. (2001). ÔTwo-way windowsÕ: clinicians as medical managers. Organization Studies, 22(4), 593–623. Maykut, R., & Morehouse, R. (1994). Beginning qualitative research: a philosophical and practical guide. London: The Falmer Press. Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis. Beverly Hills, California: Sage. OÕDwyer, B. (2001). The legitimacy of accountantsÕ participation in social and ethical accounting, auditing and reporting. Business Ethics: A European Review, 10(1), 27–39. OÕDwyer, B. (2002). Managerial perceptions of corporate social disclosure: an Irish story. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 15(3), 406–436. OÕDwyer, B. (2003). Conceptions of corporate social responsibility: the nature of managerial capture. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 16(4), 523–557. 296 B. O’Dwyer / Accounting, Organizations and Society 30 (2005) 279–296 OÕDwyer, B. (2004). Qualitative data analysis: illuminating a process for transforming a ÔmessyÕ but ÔattractiveÕ nuisance. In C. Humphrey & W. Lee (Eds.), A real life guide to accounting research: A behind the scenes view of using qualitative research methods. Amsterdam: Elsevier. Owen, D. L., Gray, R. H., & Bebbington, J. (1997). Green accounting: cosmetic irrelevance or radical agenda for change? Asia Pacific Journal of Accounting, 4(2), 175–198. Owen, D. L., Swift, T. A., Humphrey, C., & Bowerman, M. (2000). The new social audits: accountability, managerial capture or the agenda of social champions? European Accounting Review, 9(1), 81–98. Owen, D. L., Swift, T. A., & Hunt, K. (2001). Questioning the role of stakeholder engagement in social and ethical accounting, auditing and reporting. Accounting Forum, 25(3), 264–282. Parker, L. D., & Roffey, B. H. (1997). Methodological themes: back to the drawing board: revisiting grounded theory and the everyday accountantÕs and managerÕs reality. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 10(2), 212–247. Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Beverly Hills, California: Sage. Raynard, P. (1998). Coming together: a review of contemporary approaches to social accounting, auditing and reporting in non-profit organisations. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(13), 1471–1479. Silverman, D. (2000). Doing qualitative research: a practical handbook. London: Sage. Tesch, R. (1990). Qualitative research: analysis types and software tools. Basingstoke, Hampshire: The Falmer Press. Thomson, I., & Bebbington, J. (2004). Social and environmental reporting in the UK: a pedagogic evaluation. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, forthcoming. Unerman, J., & Bennett, M. (2004). Increased stakeholder dialogue and the internet: towards greater corporate accountability or reinforcing capitalist hegemony? Accounting, Organizations and Society, in press, doi:10.1016/j.aos. 2003.10.009. Weber, R. P. (1985). Basic content analysis. USA: Sage. Zadek, S. (2002). Comment; the business case for non-financial reporting. Ethical Corporation Magazine. Online Version, http://www.ethicalcorp.com/printtemplate.asp?idnum ¼ 431, accessed 9 January 2003.