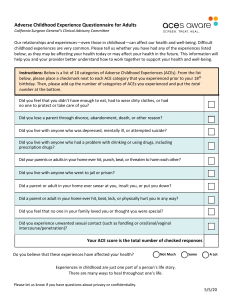

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2022 Being Black & Blue: Sex as a Moderator Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Depressive Symptoms Among Black Emerging Adults Wynta C. Alexander CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit you? Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/1025 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: AcademicWorks@cuny.edu Running head: SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS Being Black & Blue: Sex as a Moderator Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Depressive Symptoms Among Black Emerging Adults Wynta Alexander June, 2022 Submitted to the Department of Psychology of The City College of New York in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in General Psychology SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS Acknowledgments I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Dr. Adriana Espinosa for your consistent guidance, support, and valuable feedback throughout my graduate studies. This endeavor of researching and writing my thesis, would not be possible without your mentorship. Additionally, I would like to thank my committee members, Dr. Sarah O’ Neill and Dr. Adeyinka Akinsulure – Smith, for their valuable remarks on this thesis. Lastly, I would like to thank my mother, Tahela for her unwavering love, wisdom, and emotional support. I would not be the woman I am today, without you. ii SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS iii Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………….….......ii Table of Contents………………………………………………………………...………..….…iii List of Tables…………..……………………………………….…………………….….…...….iv List of Figures……………………………………………….……………………………..….....v Abstract……………………………………………………………….……………………..…..vi Introduction…………………………………………………………….………………….….….1 Methods……………………………………………………………………...………….…… .…7 a. Participants/Procedure………………………………………..……………….…..………… ..7 b. Measures……………………………………………………………………….…..………. …8 c. Data Analysis………………………………………………………………………................ 10 Results………………………………………………………………………………….………..10 Discussion…………………………………………………………………..……………………12 References………………...……………………………………………………………………...19 Appendix A; Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Questionnaire (Felitti et al., 1998) …………………………………………………………………………………………………....35 Appendix B; Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-R 10) (Andresen et al. 1994)………………………………………………………………………………………….36 SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS iv List of Tables Table 1. Participants’ Characteristics by Ethnicity …………………………………………….31 Table 2. Distribution of Adverse Childhood Experiences by Sex……………………………......32 Table 3. Hierarchical Regressions for Total ACEs and Sex Predicting Depressive Symptoms....33 SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS List of Figures Figure 1. ACEs pyramid………………………………………………………………….…….4 Figure 2. Moderation Model Including Depressive Symptoms, ACEs and Sex……………...34 v SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS vi Abstract Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) have been linked to adult mental health consequences (e.g., depressive symptoms). Black people are disproportionately affected by ACEs, and factors related to ethnic subgroups and/or sex may produce differential depressive outcomes. The current study examined the moderating role of sex in the association between adverse childhood experiences and depression symptoms using a life course of health approach among a sample of Black emerging adults. Participants (n = 159) of the current study were Black (e.g., African – American) and Black Caribbean (e.g., Jamaican) undergraduate students (18 – 59 years old; 72.3% female) attending a large, public northeastern college in the United States, who took part of a broader study aiming to understand factors influencing mental health outcomes in adulthood. Participants self – reported their sociodemographic information, their early childhood adversity (Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Questionnaire), and their depressive symptoms within the past week (Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-R 10). Significant sex differences in type of ACEs were found such that females were more likely to report sexual abuse and emotional neglect compared to males. ACEs were moderately positively correlated with depressive symptoms. Significant differences were not observed between Black and Caribbean Black students’ depressive scores. No sex x total number of ACEs interaction was found. Clinical implications for college based and culturally – sensitive interventions are discussed. SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 1 Sex as a Moderator Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Depressive Symptoms Among Black Emerging Adults Black individuals constitute the third largest racial/ethnic group in the United States (U.S.) (Cunningham et al. 2017), accounting for 12.4% of the US population (Census, 2020). At the same time research within the last two decades, indicates that 10.4% of African-American and 12.9% of Afro-Caribbean people met criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD) and have a higher rate of chronicity than White adults (Williams et al., 2007). It is estimated that by age 18, twenty percent of American youth will have had at minimum one depressive episode with majority of these adolescents being African-American or Black (Freeny et al. 2021). Black people are disproportionately exposed to multiple psychosocial stressors over the life course, which are salient risk factors for severe depression or MDD in the long run (Lincoln et al. 2011). In particular, Black people are disproportionately affected by differing forms of adverse events, such as physical and sexual abuse, before the age of 18. National studies have indicated that one in three Black youth are exposed to multiple adverse events before the age of 18 years compared to one in five White youth (Sacks & Murphey, 2018; Woods-Jaeger et al. 2021). Other research indicates that the rate of adverse experiences during childhood among Black youth is approximately 33% higher than that among White counterparts (Slopen et al., 2016). These early forms of childhood trauma occur during a formative period in which the brain has increased sensitivity to external stimuli (D'Orazio, 2016, Williams, 2020), and they have been linked to the development of severe depression in adulthood (Freeny et al., 2021). As the incidence of major depressive disorder significantly increases during adolescence and peaks in emerging adulthood (Mondi, Reynolds, & Ou, 2017), the latter period constitutes a focal point for investigation. SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 2 Depression is a leading cause for disease and death among Black people in the United States (Adams et al. 2021). Namely, suicide is currently the third leading cause of death for Black American adolescent and young adult males (Goodwill, Taylor, Watkins, 2021). Further, from 1991 – 2017, depression related actions such as suicide attempts among Black people have increased at a faster rate than any other racial/ethnic group (Rabinowitz et al. 2021). Previous studies show a higher persistence rate and impairment associated with depression for Black people in contrast to White people (Lincoln & Chae., 2012). Furthermore, while prior studies targeting the Black population, typically combine African Americans and Black Caribbeans together, lumping these ethnic subgroups together is not helpful as there are differences between them related to protective factors for depressive symptoms (Molina & James, 2016). In contrast with African – Americans, Black Caribbeans customarily belong to a higher socioeconomic status and are more likely to be immigrants to the United States which are protective factors against mental disorders (Molina & James, 2016, Robinson et al. 2022). Moreover, there are distinctions between these two ethnic subgroups related to depressive outcomes (Robinson et al. 2022). For example, Taylor et al. (2015) found for African – Americans, sense of attachment and belonging (subjective closeness) among family and non – kin associates were negatively associated with depressive symptoms and psychological distress, whereas for Black Caribbeans, in addition to subjective closeness; prevalence of family contact is more consequential for this subgroup in relation to depressive symptomology. This finding may be due to Black Caribbeans having more transnational family arrangements (Basch, 2001; Foner, 2005) compared to African – Americans. SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 3 Historically, and contemporary, Black Americans face institutionalized discrimination which subjects them to disadvantages such as poor living conditions and greater stress and adversity due to marginalized social rank which may put Black people at higher risk for depression compared to other racial groups (Keyes, Barnes, & Bates, 2011). Additionally, while studies have shown sex differences in the types of childhood trauma experienced (Melton-Fant, 2019), no study to date has investigated the differential impact of these experiences on depressive symptoms between Black male and female individuals. This information is critical for enhancing our comprehension of the differential consequences of adverse experiences in childhood on depressive symptomology among Black people. This study employs a life course approach to health perspective which highlights the significance of examining the impact of a multitude of risk factors within one’s sociocultural context at the differing stages of development (Halley Grigsby et al. 2014; Jones et al. 2019; Espinosa et al. 2021) to investigate the impact of childhood adversity on depressive symptoms at the intersection of sex among Black emerging adults. Life Course Approach to Health A life course approach to health perspective (Elder, 1985) provides a multilevel developmental approach that considers the factors that impact an individual’s health, beginning with experiences in early childhood. A life course approach to health perspective explains that experiences that occur early in life significantly affect future life outcomes (Elder et al. 2003, Umberson et al. 2014, Fothergill et al. 2016) and provides a theoretical framework for understanding the influence of adverse experiences in childhood (ACEs) on depression symptoms and risk of MDD in the long run. According to this framework, adverse experiences in SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 4 childhood can have a more extensive impact on the brain than later experiences because they induce toxic stress, which becomes chronic and can disrupt the development of the child’s brain (Jones & Pierce, 2021; Sciaraffa et al. 2018; Tottenham, 2018; Tsehay, Necho, & Mekonnen, 2020; Williams, 2020). These disruptions in brain development are exacerbated by the accumulation of these adverse experiences, thus leading to cognitive (Evan-Chase, 2014; Williams,2020) and emotional impairments over time which may predispose the individual to depression symptoms in emerging adulthood and MDD in late adulthood (Schalinski et al. 2016). Figure 1 depicts the described pathways linking adverse experiences to depression from early childhood to late adulthood. MDD Depressive Middle/Late Adulthood Emerging Adulthood Symptoms Social, Emotional and Cognitive Impairment Disrupted Neurodevelopment Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Figure 1. ACEs pyramid. Figure adapted from Felitti, et al., 1998. Adolescence Childhood SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 5 Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) among Black youth Adverse experiences in childhood (ACE) are recognized as a salient public health concern in the U.S. as national studies indicate that 66% of adults reported experiencing at least one ACE and 25% of adults reported experiencing three or more ACEs (Hampton – Anderson et al., 2021). Studies also have demonstrated that ACEs are particularly prevalent in low-income minority populations (Goldstein et al.2019). Beginning with the seminal study of ACEs, racial differences were found, with 62% of Black children experiencing at minimum one ACE compared to 51.3% of White children and 57.1% of Hispanic children (Felitti et al. 1998). Maguire – Jack, Lanier, & Lombardi (2020) found that compared to White children, Black children were more likely to have higher exposure to specific types of ACEs such as parental incarceration, and were more likely to experience all types of ACEs except for parental drug use and mental illness. Additionally, while examining individual ACEs, Freeny (2021) observed that physical abuse was the most prevalent ACE in a sample of African-American adolescents. Further, findings indicate that Black youth presented with a higher frequency of ACEs with 34% of Black children having experienced two or more ACEs compared to 22% of Hispanic children and 14% White children (Maguire – Jack, Lanier, & Lombardi, 2020). Likewise, Goldstein et al. (2021) found the rate at which Black youth experienced at minimum 2 ACEs (33%) was elevated compared to White and Hispanic children (20% and 26%, respectively). Similarly, Lee & Chen (2017) observed in their sample, Black people had the highest prevalence of ACEs. Sacks & Murphey (2018) findings further indicated youth of differing races/ethnicities do not experience ACEs similarly with 61% of Black children experienced at least one ACE in juxtaposition to 40% of White children, 51% of Hispanic children, and 23% of Asian children. SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 6 Consequently, ACEs can further exacerbate mental health consequences like depressive symptoms starting as early as childhood in Black people. For example, Black youth exposed to ACEs were found significantly more likely to have higher major depressive scores than their non – Black peers (Elkins et al. 2019). Additionally, Freeney et al. (2021) found a positive correlation between exposure to four or more ACEs and a higher probability of depression specifically among African – American adolescents. These findings suggest depressive symptomology may be an early outcome of ACEs exposed Black youth and if the inception of depression occurs during childhood, the risk of becoming clinically depressed in adulthood is likely (O'Grady and Metz 1987; Freeny et al. 2021). Sex differences in Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Prior research has found sex differences in the type of ACEs reported, whereby being female can be a risk factor for some types of ACEs (Espinosa et al. 2021, Espinosa et al. 2017; Linton and Gutierrez 2020; Llabre et al. 2017). For example, Grisby et al (2020) found that females were more likely than males to report childhood sexual abuse and domestic abuse. Fang et al. (2016) found that males were more likely to report childhood physical abuse than females. Likewise, in a low-income Black sample, Giovanelli & Reynolds (2021) found that 3% of females reported sexual abuse compared to 0.6% of males and 21% of females reported domestic violence in comparison to 19.3% of men. However, in a Hispanic emerging adult sample, Espinosa et al (2021) found that females were more likely to report physical and emotional abuse than males. These findings suggest the need for more research on sex differences on ACEs and whether these differentially explain the risk for MDD in the long run. The existing evidence suggests that there are sex differences on the impact of ACEs on mental health, with females who experience childhood trauma more likely to report internalizing disorders such as major SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 7 depressive disorder and men more likely to report externalizing disorders (e.g., substance abuse use, alcohol use) (Cavanaugh CE, Petras H, & Martins SS, 2015; Grisby et al. 2020). Similarly, Haahr-Pedersen et al (2020) findings demonstrated ACE – exposed females having significantly higher levels of depression and lower levels of psychological well – being compared to ACE – exposed males. Current Study The current study examines the moderating role of sex in the association between adverse childhood experiences and depression symptoms among a sample of Black emerging adults. Hypotheses. The following hypotheses are explored: H1: Male and female young adults will differ in the type of childhood adverse experiences reported. H2: Higher adverse experiences in childhood will significantly relate to higher symptoms of depression. H3: Sex will moderate the relation between adverse childhood experiences and symptoms of depression, such that the relation will be stronger in magnitude for females than for males. METHODS Participants & Procedure Participants for the current study were undergraduate students from The City College of New York (CCNY), who took part of a broader study aiming to understand factors influencing mental health outcomes among emerging adults. We conducted study recruitment using an online subject pool implemented by the Department of Psychology at CCNY. Participants were presented with online informed consent forms at the start of the study which emphasized how SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 8 participation is voluntary and their answers are completely anonymous. Then, participants completed a 90-minute online survey assessing factors related to mental health outcomes. Data collection took place from January 2021 to March 2022. These dates of data collection occurred during the COVID 19 pandemic and may had an impact on recruitment. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the City College of New York. All participants received course credit for their participation. Eligibility criteria for the current study’s sample included participants being at minimum 18 years of age, were able to read English, and identified as either Black and/or Caribbean Black. A total of 159 college students were included in the current study. The majority was predominantly female (72.3%) and Black (59.7%). Participants ranged from 18 to 59 years of age with the mean age being 21.1 years old (SD = 5.6). Regarding immigration status, 25.2% of participants were first - generation immigrants, 50.3% were second – generation immigrants, 22.6% were non – immigrants, and 1.9% identified as other. Measures Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). ACEs were measured using the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Questionnaire (Felitti et al., 1998), a 10-item tool used to measure childhood trauma. The questionnaire assesses 10 types of adversities an individual experienced before the age of 18 years. Five of the items are personal to the individual being assessed: physical abuse, verbal abuse, sexual abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect. Five items are related to other family members: a parent who’s an alcoholic, a mother who’s a victim of domestic violence, a family member in jail, a family member diagnosed with a mental illness, and the loss of a parent through divorce, death, or abandonment. Responses are dichotomous (yes/no), with ‘yes’ equating to a score of ‘1’ and ‘no’ SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 9 equating to a score of ‘0’. The total sum is an individual’s ACE score, with higher scores equating to more ACEs. In the original ACEs study, Felitti et al (1998) reported a Cronbach’s alpha = .88. Among this sample, the total value for Cronbach’s alpha was α = .57. However, the ACEs measure is not required to be internally consistent (Cleary, 1981; Llabre et al, 2017; Espinosa et al. 2021). Depressive Symptoms. Depressive symptoms were evaluated by the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-R 10), a 10-item Likert scale questionnaire assessing depressive symptoms in the past week (Andresen et al. 1994). It includes three items on depressed affect, five items on somatic symptoms, and two on positive affect. Options for each item range from “rarely or none of the time” (score of 0) to “all of the time” (score of 3). Scoring is reversed for items 5 and 8, which are positive affect statements. Total scores can range from 0 to 30 with a score of 10 and higher suggesting greater severity of depressive symptoms a score of 10 or greater was considered as screening positive for depressive symptoms (Andresen et al. 1994). In an ethnic minority sample, (González et al. 2017) reported Cronbach’s alphas α ≥ .70. In this sample, the value for Cronbach’s alpha was α = .83. Sociodemographic information. Participants self - reported their biological sex as either Male or Female which was coded as Male = 1 and Female = 0. For the current study, we coded race/ethnicity as Black (e.g. African – American) as 0 and Caribbean Black (e.g. Jamaican, Belizean, Trinidadian, etc.) as 1. Participants also stated their age (in years). Immigration status was coded for first generation immigrants (born outside the United States) as 1, second generation immigrants (born in United States or came to the United States as a child with at least one parent born outside the United States) as 2, non – immigrant (both participant and both SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 10 parents were born inside the United States) as 3, and other was coded as 4. Participants reported financial deprivation during childhood which explored sources of household spending and ability to pay bills as measured by 9 items using a Likert scale ranging from 1 – 5 with higher scores representing greater financial stress from the Financial Stress Questionnaire, (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1994). Data Analysis Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 28 (IBM). Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) were performed to characterize the sample. To test H1, we ran chi square tests of independence on each ACE type by sex. Then, an independent samples t – test was ran to compare the average of cumulative ACEs by sex and effect size. To test H2, Pearson correlations assessed the relation between total number of ACEs and symptoms of depression. To test H3, we assessed the moderating role of sex in the relation between ACEs and depression symptoms by way of a 2-step hierarchical regression. The first step included age, ACEs, a binary indicator for race/ethnicity and a binary indicator for sex. The second step added the interaction between sex and was conducted adjusting for age. As a second step, the interaction between sex and ACEs. If significant, we will probe the interaction using a simple slopes test. RESULTS Descriptive Statistics As reflected in Table 2, the mean ACE score was 2.15 (SD = 1.75), with 78% of the sample reporting 3 or less ACEs which signify a slightly lower prevalence of ACEs compared to 80.8% of the Black population in the original ACE who reported 3 or less ACEs (Felitti et al. 1998). SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 11 The average depressive symptom score on the CES-D-R 10 was 11.03 (SD = 5.93) with 53.5% (n = 85) scoring 10 and higher; which is considered as screening positive for depressive symptoms (Andresen et al. 1994; Risser et al. 2010; Bouvier et al. 2019). This percentage is high compared to the Black sample in the initial introduction of the CES – D 10 at 26% (Andresen et al. 1994) and more recently, Bouvier et al. (2019)’s young adult Black population at 18.5%. The percentage of males scoring 10 and higher was 38.5 % (n = 17) compared to females at 59% (n = 68). Hypothesis 1: Differences in ACEs Between Males and Females Table 2 indicates the proportion of each participant by sex that had experienced a specific type of ACE as well as the total amount of ACEs. The total number of ACEs were not significantly associated with sex t(157) = 2.1, p = .076, despite females (M = 2.3, SD = 1.8) attaining higher scores than males (M = 1.7, SD = 1.5). Chi-square tests revealed there were important sex differences in the type of ACE reported as hypothesized (H1). In particular, females were significantly more likely to report sexual abuse and emotional neglect compared to males. Due to the issue of one report of sexual abuse among males in this sample, we ran a Fisher’s exact test of independence (p = .009). Hypothesis 2: Correlation Between ACEs and Depression Pearson correlations indicated that the total number of ACEs (TotalACE) and total number of depressive symptoms (TotalD) had a statistically significant linear relation (r=.44, p < .001). This relation indicates that higher ACEs are related to higher symptoms of depression. Hypothesis 3: Moderation Analysis SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 12 Block 1 in the hierarchical regression produced an R Square value of .25, indicating that age, sex, ethnicity, and total number of ACEs account for 24.9% of the variance in depression symptoms. When the interaction between sex and ACEs were added in Block 2, the value for R Square increased to .251, thus accounting for the 25.1% of the variance in depressive symptom scores. The change in R2 for block 2 was .002, demonstrating virtually no relationship between these variables. While Block 1 was found to be statistically significant, the inclusion of the interaction for sex and ACEs in block 2 did not account for a statistically significantly increased amount of variance in depressive symptoms, thus a moderating effect is absent as depicted by the slopes of the lines (Figure 2). DISCUSSION The current study aimed to investigate the relation between depressive symptoms and adverse childhood experiences with sex as a moderating variable in a sample of Black emerging adults. It was hypothesized male and female young adults differ in the type of childhood adverse experiences reported, that higher adverse experiences in childhood significantly relate to higher symptoms of depression, and that sex moderates the relation between adverse childhood experiences and symptoms of depression. As hypothesized, our results indicated significant sex differences in type of ACEs reported such that females were more likely to report sexual abuse and emotional neglect compared to males. The reporting of sexual abuse in this sample is harmonious with previous research findings that women are more likely to report sexual abuse. For example, in a racially diverse sample, 14.89% of females reported sexual abuse compared to 6.21% of males (Lee & Chen, 2017). Similarly, Alcalá, Tomiyama, & von Ehrenstein (2017) found 16.6% of females reported sexual abuse compared to 7.1% of males. Although these differences in the experiences SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 13 do not differentially inform depressive symptoms among the current study’s sample, they can have additional implications for mental health outcomes in general as females tend to have different mental health outcomes from men, which may be a result of the differential adverse traumas experienced. Namely, research has shown high trauma exposed girls have higher parahippocampal volume than compared to high trauma exposed boys which puts them at greater risk for developing emotional disorders due to the association region of traumatic memory processing (Badura-Brack et al. 2020). This is significant, as emotional impairment has been linked to depression symptoms and, later MDD (Schalinski et al. 2016) which may make ACE exposed females more vulnerable due to being at higher risk of emotional disorders. The results from the bivariate analysis revealed that the ACEs were moderately positively correlated with depressive symptoms. This finding is in agreement with our second hypothesis and indicates that higher categorical types of ACEs experienced, regardless of the type, are related to higher symptoms of depression among Black young adults. This finding is in accord with prior research regarding the link between ACEs and depression as well as H2. Considering the COVID – 19 pandemic, 42.1% of participants reported scores of 10 and higher before March 2020 compared to 55% of participants who reported a CES - D 10 score of 10 or higher after the pandemic was underway. This finding suggests that factors related to COVID 19 may had further exacerbated feelings of depression among emerging adults. For example, in a large public US college sample, 21.5% of students reported depressive symptoms before the pandemic and increased to 31.7%, four months after the pandemic started, with being Black and female as risk factors of increases in depression (Fruehwirth, Biswas, & Perreira, 2021). In line with understanding how early experiences impact later life through the lends of the life course of health theoretical framework, a consequence of ACEs was found to be depicted SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 14 in the form of depressive symptomology among the current study’s sample. Further, considering age as a factor, the participants that fell in the emerging adulthood range of 18 – 29 years of age (Arnett, 2000, 2011), reported a score of 10 or greater on the CES – D 10 (n = 80). For many, depressive symptoms persist or materialize in emerging adulthood (Reed – Fitzke 2019). A history of childhood adversity is a formidable risk factor for depression in emerging adulthood which can leave one vulnerable to emotional distress (e.g., MDD) across the lifespan (Cohen, 2019). One reason why depressive symptoms may manifest later in life is due to the socio -cultural factor of a young person’s unwillingness to seek help for family – based stressors due to stigma against mental health services. Additionally, factors such as the lack of trust in medical institutions rooted in a history of racial discrimination and inadequate quality of healthcare, especially for African American youth, may discourage them from seeking help from providers (Forster et al. 2019) which further exacerbate mental health outcomes. Further, African – Americans tend to have more risk factors for depression (e.g., less financial resources) compared to Caribbean Black people and are more likely to report depression than other ethnic groups (Robinson et al. 2022). However, findings from this study showed no significant observed differences between these two ethnic subgroups. One explanation for this, may be due to the adequacy of funds available during childhood being fairly even between both subgroups. Another reason for no observed differences may be attributed to immigration status of the participants. While previous literature argue Caribbean Black people are more likely to be first – generation (Robinson et al. 2022), the current sample’s Caribbean Black people were mainly comprised of second – generation individuals. This is significant to note, as similarly to Black people, they may also experience relevant cultural factors from childhood that may put them at SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 15 greater risk for depressive symptoms, such as perceived discrimination. To this point, research has shown Black Caribbeans whose parents were born outside the United States report fewer depressive symptoms than those who parents were born within the United States (Robinson et al. 2022). Lastly, moderation analysis indicated that although females experienced different ACEs than males, said differences did not influence how ACEs relate to symptoms of depression. However, in previous studies, findings reflect sex differences in type of ACE experienced have clinical implications. For instance, a recent study that examined substance use in emerging adulthood, showed females had a higher count of ACEs compared to males and the type of ACE had a differential impact on substance use (Espinosa et al. 2021). Cultural norms related to masculinity and femininity may be one reason why sex did not moderate the relation between ACEs and symptoms of depression in our sample. Cultural expectations may cause reporting biases that affect rates of psychopathology between males and females (White & Kaffman, 2019). All too often, Black men are raised to “man up” and not reflect and/or share their emotions. Another reason why sex did not moderate the relation between ACES and symptoms of depression in this sample may be due to the how the questions in the CES – D 10 are presented. Depressive symptoms among the Black population may be reported differently than our traditional understanding of reporting this mental health outcome as illustrated in the DSM – 5 (Walton & Payne, 2016). Contrary to past studies, recent research has shown Black men from low socioeconomic backgrounds experience depressive symptoms at rates similar to or higher than those reported by White men & women (Kogan et al. 2017). Typical assessments of depression may had led to under – reporting among this population of men. When characteristics SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 16 of anger and frustration are operationalized as depressive symptoms for men, rates of depression typically increase (Kogan et al. 2017). CONTRIBUTIONS Strengths of the current study include the use the investigation of an under-researched population. The current study contributes to the limited literature examining the relationship between childhood adversity and depressive symptoms among a Black population. Particularly, we sought to investigate the impact of childhood adversity on depressive symptoms at the intersection of sex among Black emerging adults. Studies that do address depressive symptoms in the Black population, mainly discuss these symptoms without making a distinction between sex (Walton & Payne, 2016). Thus, the need to increase awareness that sex differences matter regarding consequences of ACEs on differential mental health consequences is imperative. LIMITATIONS As stated previously, data collection occurred during an unexpected multi - year global public health crisis, COVID – 19, which may have an impact on depressive symptomology among our sample. Additionally, the current student included a sample of only college students and further, a higher percentage of females compared to males, thus the generalizability of our findings across other universities and institutions may be limited. Another limitation is that all survey measures used were dependent on self – report of the participant and may have been influenced by selective disclosure or withholding of information. Lastly, due to the cross – sectional nature of our data, we are unable to infer a causal relationship between total number of ACEs and total number of depressive symptoms. CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 17 Limitations notwithstanding, the current study’s findings provide several implications for future research and application. Considering that a college education can alleviate outcomes from early life adversity (Grisby et al. 2020), academic institutions like CCNY can play a vital aspect in developing and administering resources related to trauma – focused interventions. For example, incorporating mindfulness techniques with ACE – exposed students can involve observing the present moment, describing personal experiences in the present moment, acting with awareness by being conscious of one own’s personal thoughts and emotions in the present time, nonjudgement in comprehending a personal experience and not placing judgment, and non – reactivity, as in taking time to accept personal experiences and emotions surrounding them as they are and not making rash decisions regarding these experiences and emotions (Roche et al., 2019) to manage varying emotions including negative ones. Further, many interventions created to improve mindfulness capabilities have been shown to be constructive in reducing psychological distress (e.g., depression) and improving resilience among college students (Anderson, Gardner, & Hunt, 2021). While the evidence indicates the need for ACE – focused interventions in college settings, culturally focused interventions that address the needs of both Black and Caribbean Black individuals are additionally essential. One component that should be incorporated in culturally sensitive ACE prevention interventions for Black people should include spirituality, as it is significant in the Black community and is a source of hope and healing and provides a sense of community (Freeny et al. 2020). Further, among emerging adults, high spirituality has been found to be associated with less depression compared to those with low spirituality (Barton and Miller, 2015). Within this intervention, constructs can include meaning – focused mediation, reading scriptures, and other similar activities. Similarly Caribbean Black people hold spirituality SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 18 in high regard however their practices tend to incorporate West African supernatural entities such as Orishas (Taylor et al. 2009). CONCLUSION While there is an abundance of literature on the negative outcomes of ACEs and sex differences on depressive symptoms, the relationship between these two factors are often not studied together. Further, the current study contributes to the existing body of literature examining depressive symptomology, ACE exposure and sex differences among emerging adults. Using a life course of health framework, the current study underscores the impact of the differential ACEs reported by sex as well as the positive correlation between number of ACEs reported and number of depressive symptoms experienced. Our findings reinforce the need for culturally sensitive and college setting-based interventions targeting Black and Caribbean Black people in an effort to better address ACEs and existing sex differences, and the association between them on depressive outcomes. SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS References Adams, L.B., Baxter, S.L.K., Lightfoot, A.F. et al. Refining Black men’s depression measurement using participatory approaches: a concept mapping study. BMC Public Health 21, 1194 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11137-5 Alcalá, H. E., Tomiyama, A. J., & von Ehrenstein, O. S. (2017). Gender Differences in the Association between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Cancer. Women's health issues : official publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women's Health, 27(6), 625–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2017.06.002 Anderson, J. C., Gardner, A. J., & Hunt, B. P. (2021). Drinking Behavior Among College Students: Interventions to Increase Mindfulness and Social Capital. Journal of Social, Behavioral & Health Sciences, 15(1), 76–86. https://doi-org.ccnyproxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.5590/JSBHS.2021.15.1.05 Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003066X.55.5.469 Badura-Brack, A. S., Mills, M. S., Embury, C. M., Khanna, M. M., Earl, A. K., Stephen, J. M., Yu-Ping Wang, Calhoun, V. D., & Wilson, T. W. (2020). Hippocampal and parahippocampal volumes vary by sex and traumatic life events in children. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience, 45(4), 288–297. https://doi-org.ccnyproxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1503/jpn.190013 19 SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 20 Bailey, R. K., Patel, M., Barker, N. C., Ali, S., & Jabeen, S. (2011). Major depressive disorder in the African American population. Journal of the National Medical Association, 103(7), 548–557. https://doi-org.ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1016/S0027-9684(15)303801 Barton, Y. A., & Miller, L. (2015). Spirituality and positive psychology go hand in hand: an investigation of multiple empirically derived profiles and related protective benefits. Journal of religion and health, 54(3), 829–843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943015-0045-2 Bureau, U. S. C. (2022, June 10). 2020 census illuminates racial and ethnic composition of the country. Census.gov. Retrieved July 19, 2022, from https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/improved-race-ethnicity-measures-revealunited-states-population-much-more-multiracial.html#:~:text=to%20self%2Didentify.,Black%20or%20African%20American%20Population,million%20and%2012.6%25%20in %202010. Cohen, J. R., Thomsen, K. N., Racioppi, A., Ballespi, S., Sheinbaum, T., Kwapil, T. R., & Barrantes-Vidal, N. (2019). Emerging Adulthood and Prospective Depression: A Simultaneous Test of Cumulative Risk Theories. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 48(7), 1353–1364. https://doi-org.ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1007/s10964-019-01017-y Cunningham, T. J., Croft, J. B., Liu, Y., Lu, H., Eke, P. I., & Giles, W. H. (2017). Vital Signs: Racial Disparities in Age-Specific Mortality Among Blacks or African Americans United States, 1999-2015. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 66(17), 444– 456. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6617e1 SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 21 D'Orazio, S. J. (2016). "Assessing the Impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences on Brain Development." Inquiries Journal, 8(07). Retrieved from http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=1429 Dorvil, S. R., Milkie Vu, Haardorfer, R., Windle, M., & Berg, C. J. (2020). Experiences of Adverse Childhood Events and Racial Discrimination in Relation to Depressive Symptoms in College Students. College Student Journal, 54(3), 295–308. Elder, G.H., Johnson, M.K., Crosnoe, R. (2003). The Emergence and Development of Life Course Theory. In: Mortimer, J.T., Shanahan, M.J. (eds) Handbook of the Life Course. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-306-48247-2_1 Elkins, J., Miller, K. M., Briggs, H. E., Kim, I., Mowbray, O., & Orellana, E. R. (2019). Associations between Adverse Childhood Experiences, Major Depressive Episode and Chronic Physical Health in Adolescents: Moderation of Race/Ethnicity. Social Work in Public Health, 34(5), 444–456. https://doi-org.ccnyproxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1080/19371918.2019.1617216 Espinosa, A., Bonner, M., & Alexander, W. (2021). The Differential Contribution of Adverse Childhood Experiences and Perceived Discrimination on Substance Use among Hispanic Emerging Adults. Journal of psychoactive drugs, 53(5), 422–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2021.1986242 Forster, M., Rogers, C. J., Benjamin, S. M., Grigsby, T., Lust, K., & Eisenberg, M. E. (2019). Adverse Childhood Experiences, Ethnicity, and Substance Use among College Students: SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 22 Findings from a Two-State Sample. Substance Use & Misuse, 54(14), 2368–2379. https://doi-org.ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1080/10826084.2019.1650772 Fothergill, K., Ensminger, M. E., Doherty, E. E., Juon, H. S., & Green, K. M. (2016). Pathways from Early Childhood Adversity to Later Adult Drug Use and Psychological Distress: A Prospective Study of a Cohort of African Americans. Journal of health and social behavior, 57(2), 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146516646808 Freeny, J., Peskin, M., Schick, V., Cuccaro, P., Addy, R., Morgan, R., Lopez, K. K., & JohnsonBaker, K. (2021). Adverse Childhood Experiences, Depression, Resilience, & Spirituality in African-American Adolescents. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 14(2), 209– 221. https://doi-org.ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1007/s40653-020-00335-9 Fruehwirth, J. C., Biswas, S., & Perreira, K. M. (2021). The Covid-19 pandemic and mental health of first-year college students: Examining the effect of Covid-19 stressors using longitudinal data. PLoS ONE, 16(3). https://doi-org.ccnyproxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1371/journal.pone.0247999 Giovanelli, A., & Reynolds, A. J. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences in a low-income black cohort: The importance of context. Preventive Medicine: An International Journal Devoted to Practice and Theory, 148. https://doi-org.ccnyproxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106557 Goldstein, E., Topitzes, J., Miller-Cribbs, J., & Brown, R. L. (2021). Influence of race/ethnicity and income on the link between adverse childhood experiences and child flourishing. Pediatric Research, 89(6), 1861–1869. https://doi-org.ccnyproxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1038/s41390-020-01188-6 SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 23 González, P., Nuñez, A., Merz, E., Brintz, C., Weitzman, O., Navas, E. L., Camacho, A., Buelna, C., Penedo, F. J., Wassertheil-Smoller, S., Perreira, K., Isasi, C. R., Choca, J., Talavera, G. A., & Gallo, L. C. (2017). Measurement properties of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D 10): Findings from HCHS/SOL. Psychological Assessment, 29(4), 372–381. https://doi-org.ccnyproxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1037/pas0000330 Goodwill, J. R., Taylor, R. J., & Watkins, D. C. (2021). Everyday discrimination, depressive symptoms, and suicide ideation among African American men. Archives of Suicide Research, 25(1), 74–93. https://doi-org.ccnyproxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1080/13811118.2019.1660287 Grigsby, T. J., Rogers, C. J., Albers, L. D., Benjamin, S. M., Lust, K., Eisenberg, M. E., & Forster, M. (2020). Adverse Childhood Experiences and Health Indicators in a Young Adult, College Student Sample: Differences by Gender. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 27(6), 660–667. https://doi-org.ccnyproxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1007/s12529-020-09913-5 Haahr-Pedersen, I., Perera, C., Hyland, P., Vallières, F., Murphy, D., Hansen, M., Spitz, P., Hansen, P., & Cloitre, M. (2020). Females have more complex patterns of childhood adversity: implications for mental, social, and emotional outcomes in adulthood. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1–11. https://doi-org.ccnyproxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1080/20008198.2019.1708618 Hampton-Anderson, J. N., Carter, S., Fani, N., Gillespie, C. F., Henry, T. L., Holmes, E., Lamis, D. A., LoParo, D., Maples-Keller, J. L., Powers, A., Sonu, S., & Kaslow, N. J. (2021). SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 24 Adverse childhood experiences in African Americans: Framework, practice, and policy. American Psychologist, 76(2), 314–325. https://doi-org.ccnyproxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1037/amp0000767 Jones, M. K., Hill-Jarrett, T. G., Latimer, K., Reynolds, A., Garrett, N., Harris, I., Joseph, S., & Jones, A. (2021). The Role of Coping in the Relationship Between Endorsement of the Strong Black Woman Schema and Depressive Symptoms Among Black Women. Journal of Black Psychology, 47(7), 578–592. https://doi-org.ccnyproxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1177/00957984211021229 Jones, M. S., & Pierce, H. (2021). Early Exposure to Adverse Childhood Experiences and Youth Delinquent Behavior in Fragile Families. Youth & Society, 53(5), 841–867. https://doiorg.ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1177/0044118X20908759 Karatekin, C. (2018). Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), Stress and Mental Health in College Students. Stress & Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 34(1), 36–45. https://doi-org.ccnyproxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1002/smi.2761 Keyes, K. M., Barnes, D. M., & Bates, L. M. (2011). Stress, coping, and depression: Testing a new hypothesis in a prospectively studied general population sample of U.S.-born Whites and Blacks. Social Science & Medicine, 72(5), 650–659. https://doi-org.ccnyproxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.12.005 Kogan, S. M., Cho, J., Oshri, A., & MacKillop, J. (2017). The influence of substance use on depressive symptoms among young adult black men: The sensitizing effect of early SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 25 adversity. The American Journal on Addictions, 26(4), 400–406. https://doi-org.ccnyproxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1111/ajad.12555 Lee, R. D., & Chen, J. (2017). Adverse childhood experiences, mental health, and excessive alcohol use: Examination of race/ethnicity and sex differences. Child abuse & neglect, 69, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.04.004 Lincoln, K. D., & Chae, D. H. (2012). Emotional support, negative interaction and major depressive disorder among African Americans and Caribbean blacks: Findings from the national survey of American life. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology: The International Journal for Research in Social and Genetic Epidemiology and Mental Health Services, 47(3), 361–372. https://doi-org.ccnyproxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1007/s00127-011-0347-y Maguire-Jack, K., Lanier, P., & Lombardi, B. (2020). Investigating racial differences in clusters of adverse childhood experiences. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 90(1), 106–114. https://doi-org.ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1037/ort0000405 Marshall, K., Witting, A. B., Sandberg, J. G., & Bean, R. (2020). We Shall Overcome: The Association Between Family of Origin Adversity, Coming to Terms, and Relationship Quality in African Americans. Contemporary Family Therapy: An International Journal, 42(3), 305–317. https://doi-org.ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1007/s10591-02009542-w Melton-Fant, C. (2019). Childhood adversity among Black children: The role of supportive neighborhoods. Children & Youth Services Review, 105, N.PAG. https://doi-org.ccnyproxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104419 SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 26 Molina, K. M., & James, D. (2016). Discrimination, internalized racism, and depression: A comparative study of African American and Afro-Caribbean adults in the US. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 19(4), 439– 461. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430216641304 Obuobi-Donkor, G., Nkire, N., & Agyapong, V. (2021). Prevalence of Major Depressive Disorder and Correlates of Thoughts of Death, Suicidal Behaviour, and Death by Suicide in the Geriatric Population-A General Review of Literature. Behavioral sciences (Basel, Switzerland), 11(11), 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11110142 Poole, J. C., Dobson, K. S., & Pusch, D. (2017). Childhood adversity and adult depression: The protective role of psychological resilience. Child Abuse & Neglect, 64, 89–100. https://doi-org.ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.12.012 Rabinowitz, J. A., Jin, J., Kahn, G., Kuo, S.-C., Campos, A., Renteria, M., Benke, K., Wilcox, H., Ialongo, N. S., Maher, B. S., Kertes, D., Eaton, W., Uhl, G., Wagner, B. M., & Cohen, D. (2021). Genetic propensity for risky behavior and depression and risk of lifetime suicide attempt among urban African Americans in adolescence and young adulthood. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics, 186B: 456– 468. https://doi-org.ccnyproxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1002/ajmg.b.32866 Robinson, M. A., Kim, I., Mowbray, O., & Disney, L. (2022). African Americans, Caribbean Blacks and Depression: Which Biopsychosocial Factors Should Social Workers Focus On? Results from the National Survey of American Life (NSAL). Community mental health journal, 58(2), 366–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-021-00833-6 SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 27 Rose, T., McDonald, A., Von Mach, T., Witherspoon, D. P., & Lambert, S. (2019). Patterns of Social Connectedness and Psychosocial Wellbeing among African American and Caribbean Black Adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(11), 2271–2291. https://doi-org.ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1007/s10964-019-01135-7 Santolaya Prego de Oliver, J., Muñoz-Navarro, R., González-Blanch, C., Llorca-Mestre, A., Malonda, E., Medrano, L., Ruiz-Rodríguez, P., Moriana, J. A., & Cano-Vindel, A. (2020). Disability and perceived stress in primary care patients with major depression. Psicothema, 32(2), 167–175. https://doi-org.ccny proxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.7334/psicothema2019.319 Schalinski, I., Teicher, M. H., Nischk, D., Hinderer, E., Müller, O., & Rockstroh, B. (2016). Type and timing of adverse childhood experiences differentially affect severity of PTSD, dissociative and depressive symptoms in adult inpatients. BMC Psychiatry, 16, 1–15. https://doi-org.ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1186/s12888-016-1004-5 Sciaraffa, M. A., Zeanah, P. D., & Zeanah, C. H. (2018). Understanding and Promoting Resilience in the Context of Adverse Childhood Experiences. Early Childhood Education Journal, 46(3), 343–353 Seaton, E. K., & Carter, R. (2020). Pubertal timing as a moderator between general discrimination experiences and self-esteem among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 26(3), 390–398. https://doi-org.ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1037/cdp0000305 Slopen, N., Shonkoff, J. P., Albert, M. A., Yoshikawa, H., Jacobs, A., Stoltz, R., & Williams, D. R. (2016). Racial disparities in child adversity in the U. S.: Interactions with family SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 28 immigration history and income. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 50(1), 47– 56. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.06.013 Stern, K. R., & Thayer, Z. M. (2019). Adversity in childhood and young adulthood predicts young adult depression. International Journal of Public Health, 64(7), 1069–1074. https://doi-org.ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1007/s00038-019-01273-6 Sternthal, M., Slopen, N., Williams, D.R. “Racial Disparities in Health: How Much Does Stress Really Matter?” Du Bois Review, 2011; 8(1): 95-113. Taylor, R. J., Chatters, L. M., & Jackson, J. S. (2009). Correlates of Spirituality among African Americans and Caribbean Blacks in the United States: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. The Journal of black psychology, 35(3), 317–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798408329947 Taylor, R. J., Chae, D. H., Lincoln, K. D., & Chatters, L. M. (2015). Extended family and friendship support networks are both protective and risk factors for major depressive disorder and depressive symptoms among African-Americans and black Caribbeans. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 203(2), 132–140. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000249 Tsehay, M., Necho, M., & Mekonnen, W. (2020). The role of adverse childhood experience on depression symptom, prevalence, and severity among school going adolescents. Depression Research and Treatment, 2020, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/5951792 Thompson, M. P., Kingree, J. B., & Lamis, D. (2019). Associations of adverse childhood experiences and suicidal behaviors in adulthood in a U.S. nationally representative sample. SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 29 Child: Care, Health & Development, 45(1), 121–128. https://doi-org.ccnyproxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1111/cch.12617 Tottenham, N. (2018). The fundamental role of early environments to developing an emotionally healthy brain. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 5(1), 98–103. https://doi-org.ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1177/2372732217745098 Walton, Q. L., & Payne, J. S. (2016). Missing the mark: Cultural expressions of depressive symptoms among African-American women and men. Social Work in Mental Health, 14(6), 637–657. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2015.1133470 Wang, X., Gao, L., Yang, J., Zhao, F., & Wang, P. (2020). Parental Phubbing and Adolescents’ Depressive Symptoms: Self-Esteem and Perceived Social Support as Moderators. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 49(2), 427–437. https://doi-org.ccnyproxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1007/s10964-019-01185-x White, J. D., & Kaffman, A. (2019). The Moderating Effects of Sex on Consequences of Childhood Maltreatment: From Clinical Studies to Animal Models. Frontiers in neuroscience, 13, 1082. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.01082 Williams, A. (2020). Early Childhood Trauma Impact on Adolescent Brain Development, Decision Making Abilities, and Delinquent Behaviors: Policy Implications for Juveniles Tried in Adult Court Systems. Juvenile & Family Court Journal, 71(1), 5–17. https://doiorg.ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1111/jfcj.12157 Williams, D. R., González, H. M., Neighbors, H., Nesse, R., Abelson, J. M., Sweetman, J., & Jackson, J. S. (2007). Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: results from the National Survey SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 30 of American Life. Archives of general psychiatry, 64(3), 305–315. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305 Woods-Jaeger, B., Briggs, E. C., Gaylord-Harden, N., Cho, B., & Lemon, E. (2021). Translating cultural assets research into action to mitigate adverse childhood experience–related health disparities among African American youth. American Psychologist, 76(2), 326– 336 https://doi-org.ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/10.1037/amp0000779 SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 31 Table 1. Participants’ Characteristics by Ethnicity Variable Sex Male Female Immigration Status First - Generation Second - Generation Non - Immigrant Other Age Range 18 - 29 30 + Financial Distress Depressive Symptoms Black = 95 (59.7%) Caribbean Black = 64 (40.3%) n, % 27 (16.9%) 68 (42.7%) 17 (10.7%) 47 (29.5%) 22 (13.8%) 41 (25.8%) 30 (18.9%) 2 (0.01%) 18 (11.3%) 39 (24.5%) 6 (0.04%) 1 (0.01%) 84 (52.8%) 11 (0.07%) 21.48 (6.69) 10.78 (5.81) 62 (39%) 2 (0.01%) 21.95 (6.13) 11.39 (6.12) n, % n, % (M, SD) (M, SD) SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 32 Table 2. Distribution of Adverse Childhood Experiences by Sex Variable Type of ACEs Verbal Abuse Physical Abuse Sexual Abuse Emotional Neglect Physical Neglect Parent Divorced/Separated Witness Domestic Violence Household Member with SA Household Member with MI Household Member in Prison Cumulative ACEs Total Male Female χ2 p φ 61(38.4) 51(32.1) 20(17.4) 52(32.7) 1(0.6) 70(44) 12(7.5) 22(13.8) 38(23.9) 14(8.8) 2.15 (1.75) 13(29.5) 13(29.5) 1(2.3) 8(18.2) 0(0) 19(43.2) 4(9.1) 6(13.6) 9(20.5) 1(2.3) 1.68 (1.49) 48(41.7) 38(33) 21(13.2) 44(38.3) 1(0.9) 51(44.3) 8(7) 16(13.9) 29(25.2) 13(11.3) 2.33 (1.81) 2.00 0.18 6.35 5.83 0.39 0.02 0.21 0.00 0.40 3.23 0.16 0.67 0.01 0.02 0.54 0.90 0.65 0.96 0.53 0.07 .076 0.11 0.03 0.2 0.19 0.05 0.01 0.04 0.00 0.05 0.14 (n, %) M, (SD) Note: Table presents descriptive information for the sample. Independent samples t – tests and χ2 tests of independence compared type of ACE with sex of participants. SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 33 Table 3. Hierarchical Regressions for Total ACEs and Sex Predicting Depressive Symptoms Variable B SE t p R² R²adj delta R² Constant 12.963 1.8 7.199 0.001 0.249 0.229 0.249 Age (in years) -0.219 0.075 -2.94 0.004 Ethnicity 0.008 0.855 0.01 0.992 Sex -1.501 0.935 -1.604 0.111 ACEs 1.448 0.24 6.03 0.001 Sex X ACEs -0.401 0.598 -0.671 0.503 0.251 0.227 0.002 Block 1 Summary: F = 12.754, df (4,154), p < .05 Block 2 Summary: F = 10.257, df (1,153), p = .503 SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS Figure 2. Moderation Model Including Depressive Symptoms, ACEs and Sex Note: The interaction between sex and total number of ACEs as predictor of depressive symptoms was not significant. 34 SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS 35 Appendix A. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Questionnaire (Felitti et al., 1998) SEX AS A MODERATOR BETWEEN ACES AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS Appendix B. Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-R 10), (Andresen et al. 1994) 36