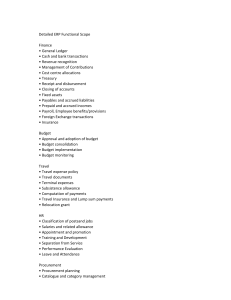

Industrial Marketing Management 34 (2005) 681 – 694 Supplier involvement in new product development in the food industry Wendy van der Valk *, Finn Wynstra 1 Erasmus Research Institute of Management, RSM Erasmus University, Netherlands PO Box 1738 – 3000 DR Rotterdam, Netherlands Received 30 April 2004; received in revised form 26 April 2005; accepted 11 May 2005 Abstract Purchasing and supplier involvement as one possible explanatory factor of product development success has been gathering growing attention from both managers and researchers. This paper presents the results of a Dutch benchmark study into supplier involvement in product development, and discusses the topic more specifically in the context of the food industry. Regarding supplier involvement, this industry has not been studied intensively, although its specific characteristics make continuous development of new products imperative and the amount of outsourcing of production and development has increased substantially. The benchmark was conducted by means of an existing framework which has not yet been applied to the food industry. The food company in the benchmark study performs consistently better than companies from other industries. At the same time, the results of a similar case study carried out at a Scandinavian food company show contradictory results. By comparing the Dutch and the Scandinavian case, we illustrate that our analytical framework can explain these different results in terms of the underlying processes and pre-conditions, thereby validating its application to the food industry. D 2005 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 1. A contingency-based approach to supplier involvement in product development In an ever-increasing competitive environment, suppliers can contribute to product development in several ways. Involving suppliers in product development is supposed to have a positive effect on development time, development and product cost and product quality (McGinnis & Vallopra, 1999; Ragatz, Handfield, & Petersen, 2002). However, this turns out not to be true for all situations (Birou, 1994; Hartley, Zirger, & Kamath, 1997). Therefore, some authors argue that the way supplier involvement in product development is managed is crucial in explaining the amount of success of this involvement (Clark, 1989; Ragatz, Handfield, & Scannell, 1997; Wynstra, 1998). At the same time, literature in the area of product innovation as well as supplier involvement demonstrates that researchers increasingly adopt thoughts from contin* Corresponding author. Tel.: +31 0 10 408 16 36. E-mail addresses: wvalk@rsm.nl (W. van der Valk), fwynstra@rsm.nl (F. Wynstra). 1 Tel.: +31 0 10 408 19 90. 0019-8501/$ - see front matter D 2005 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2005.05.009 gency theory to address the topic (Souder, Sherman, & Davies-Cooper, 1998). Contingency theory tries to understand and explain phenomena and organizational issues from a situational point of view. Applying this to the topic of supplier involvement in new product development, this means that determining the way suppliers should be involved in product development requires an analysis of the specific contextual factors at hand. For example, one of the contingencies studied in the literature on supplier involvement in product development regards the degree of innovativeness—or the technological and market uncertainty—of the overall new product development project. Eisenhardt and Tabrizi (1995), for example, found that supplier involvement accelerated product development time, but only in mature market segments and when the product development effort was well defined. Ragatz et al. (2002) finds evidence that increased technological uncertainty has a negative impact on cost results, but this effect is partly mediated through the use of effective integrative strategies. In other words, higher degrees of technological uncertainty increase the need for project-related supplier management activities. 682 W. van der Valk, F. Wynstra / Industrial Marketing Management 34 (2005) 681 – 694 In line with this reasoning, a contingency-based framework for analyzing processes related to purchasing and supplier involvement in product development has been developed in prior research (Van Echtelt, Wynstra, Van Weele & Duysters, 2004; Wynstra, van Weele, & Axelsson, 1999). This framework posits that in order to be successful, the involvement of suppliers needs to be embedded in the wider context of bringing a purchasing perspective to the development process. Such a perspective looks at the availability and suitability of external resources (i.e., the knowledge and skills of suppliers) for integration in the development process under conditions of timely availability and appropriate or optimal costs and quality of the input items (parts, materials etc.) embodying those resources. This integration of purchasing and product development processes and considerations is sometimes referred to as Integrated Product Development and Sourcing (IPDS) (Van Echtelt, Wynstra, & van Weele, 2004; Wynstra, van Weele, & Weggeman, 2001). Traditionally, most research on supplier involvement in product development has been situated in large-scale assembly industries, like the electronics and automotive sectors. Little is known about supplier involvement in the food industry. Yet, this industry has increasingly been relying on suppliers for carrying out production and development activities. Hence, it would be interesting to investigate to what extent an analysis framework for studying supplier involvement—which originally is mainly based on research in assembly industries—would also hold for the food industry, and whether there are any particular features and challenges in managing supplier involvement in this sector. The results of such a study would help in further strengthening the external validity of the analysis framework. In the remainder of this paper, we first discuss some specific characteristics of the food industry and its product development process, after which the analysis framework is presented in more detail. Subsequently, we discuss the results of a Dutch benchmark study where we compared eight different development projects from four different manufacturing companies, one of which is from the food industry. This is followed by a detailed discussion of the two Dutch food development projects and a comparison with two projects at a Scandinavian food company. The paper ends with a discussion of the conclusions and implications, specifically focusing on the applicability of our analytical framework to supplier involvement in product development in the food industry. 2. Product development and supplier involvement in the food industry The food industry is composed of very diverse firms processing various ingredients to in any way produce food products in solid (crisps, quick meal solutions) or liquid form (soup, beverages). The food industry is well known for its large variety of products, which vary in size, packaging, flavour, et cetera. Most of these products are sold through retailers to large numbers of consumers throughout the world, and margins are relatively low. For the larger part, the industry in Europe exists of small to medium sized enterprises, supplying local or specialist niche markets (Hingley & Lindgreen, 2004; Traill & Grunert, 1997). Large companies and multinational enterprises complete the industry. Whereas large food companies supply a limited range of national brands and processed foods and increasingly produce private-label products for national retailers (Verhoef, Nijssen, & Sloot, 2002), multinationals are additionally engaged in exports or other multinational activities. As a result of increased consumer awareness, consumers impose more and more demands on food companies (Weston & Chiu, 1996). Consumers have more money to spend, but also expect higher product quality in terms of freshness, storage life, et cetera. There is a growing interest in convenience products due to changes in lifestyle (going out more, working longer hours, women working in addition to men or instead). The market situation is one of consumer pull; consumer buying patterns direct product development. In addition to that, retailers buy and assign shelf space based on consumer buying patterns; since shelf space gives retailers strong bargaining power when negotiating with food companies, the power in the supply network is also largely in hands of the retailers (Hingley & Hollingsworth, 2003). Another trend is the continuous growth of retail chains, whereby the retailers increase their power over food companies even further. More and more retailers switch to operating under the flag of an established brand name (e.g., ICA or Albert Heijn), and more and more chains go together in consortiums like Ahold or Carrefour. Food companies need to position their products well in relation to their competitors in order to get in favour with the retailers and with the consumer. These trends and specific characteristics of the food industry bring growing pressure upon food companies. In their struggle to obtain shelf space in supermarkets, food companies must know which products to offer to the final consumer, as to initiate a customer-pull situation at the retailers. This means that much attention has to be given to researching consumer wishes on the one hand and developments in supplier offerings on the other. The latter can bring about ideas for new food products, after which the consumer has to be convinced that he or she wants or needs that product. The continuing changes in consumer buying patterns also require speedy development from food companies; what consumers buy today will probably not be bought tomorrow. Retailers practically force food companies to either innovate, or loose shelf space to the competitor that does. New developments need to take place in rapid succession. However, very few of the newly launched products are successful in terms of acceptance by the market. Rudolph W. van der Valk, F. Wynstra / Industrial Marketing Management 34 (2005) 681 – 694 (1995) estimates that during 1993, well over 8000 new products were introduced to US retail markets, some 80% to 90% of which failed within one year, resulting in missed sales targets, lost revenues and delayed profits in addition to wasted development resources. Few food companies are able to meet these increased demands by themselves. Even though the industry’s situation in terms of number of suppliers and complexity of the product is different from that faced by automotive and electronics assembly firms, the food industry still has to cope with issues like for example capacity, functionality and quality (hygiene aspects that are imposed by legislation) of production equipment and the Finterfaces_ between combinations of ingredients that either Fmix_ or Fdon_t mix_. This makes product innovation in this industry quite complex. External resources are therefore necessary to keep up with the high pace of innovation needed. Suppliers of ingredients, machines and packaging materials can make a valuable contribution to efficient and effective product development, by bringing in expert knowledge in all kinds of relevant areas. Increasingly, food companies make use for example of ‘‘co-packers’’, external suppliers that make a ready final product, to satisfy their production – and sometimes even product development –needs. In general, many food companies have become more reliant on external suppliers and this has led to an increasing focus on purchasing and supply management in general (Anderson & Woolley, 2002). The IPDS framework may provide us with a tool to analyse manufacturer – supplier collaboration in product development in the food industry in a way that systematically combines attention to strategic and operational processes, while explicitly studying the context of such collaboration in terms of contingencies affecting the appropriate extent and form of these processes and the pre-conditions for carrying them out. 3. Results, processes and pre-conditions of supplier involvement The framework is an adaptation of two respective models by Wynstra et al. (2000, 1999) and Monczka, Handfield, and Scannell (2000) and is structured according to an input – throughput –output logic. Fig. 1 provides a schematic representation of the framework. Inputs are the starting conditions in terms of the organizational structure and capabilities of both the customer and the supplier. A distinction is made between drivers and enablers. Drivers are factors that drive a company towards a specific form and extent of IPDS processes. These factors can be internal as well as external to the company and may exist on three different levels of analysis: the business unit level, the project level and the level of the individual buyer – supplier relationship. Enablers are the conditions, whose presence can help a company to organize the required IPDS processes. These enablers can be present internally or 683 externally to the buying organization or in the specific relationship between buyer and supplier. Throughputs are the project-related processes to set-up and manage supplier involvement in product development from a buying firm perspective. Strategic Management Processes use a more long-term horizon of preparing and developing a supply base in selected technological areas, while Operational Management Processes are more shortterm focused, within the context of a specific project and specific supplier involvement. Outputs are the (potential) short-term and long-term results of involving suppliers in product development. Examples of short-term effects are reduced development time and cost, reduced product cost and increased product quality. The framework makes an explicit distinction between overall project results and the results of the collaboration with a specific supplier within that project, as the two may not always be fully correlated due to external influences. Examples of long-term effects are access to critical supplier technologies, better/increased alignment of technology roadmaps and more efficient and effective collaboration (Wynstra et al., 2001). The core of the framework consists of the strategic and operational management processes (Van Echtelt, Wynstra, van Weele, et al., 2004 and Van Echtelt, Wynstra, van Weele, Duysters, et al., 2004). The Strategic Management arena contains seven processes that together provide longterm, strategic direction and support for adopting supplier involvement in individual development projects. These processes also contribute to building up a willing and capable supplier base to meet the current and future technology and capability needs. The Operational Management arena contains nine processes that are aimed at planning, managing and evaluating the actual collaborations in terms of their intermediate and final development performance in a development project. The success of involving suppliers in product development as a strategy depends on the firm’s ability to capture both short-term and long-term benefits. If companies spend most of their time on operational management in development projects, they will fail to Fleverage_ the effect of planning and preparing such involvement through strategic management activities. Also, they will not be sufficiently positioned to capture possible long-term technology and learning benefits that may spin off from individual projects. Long-term collaboration benefits can only be captured if a company can build long-term relationships with key suppliers, where it builds learning routines and ensures that the capability sets of both parties are still aligned and are still useful for new joint projects. To obtain such benefits, companies need a set of strategic decision-making processes that help to create this alignment. Having established explicit and extensive strategies, a company obviously still needs a set of operational management processes to identify the right partners and the appropriate level of supplier involvement for the various 684 Conditions Management Processes Strategic Business Unit Enablers Enablers Drivers Strategic Business Unit Drivers Periodically evaluating guidelines and supplier base performance Determining in outsourcing technologies and NPD activities 7 Motivating suppliers to develop specific knowledge or products 6 Exploiting existing supplier skills and (technical) capabilities 1. BU Size 2. Supplier Dependence 3. R&D Dependence 4. Manufacturing Type 1 Strategic Management Arena 5 Formulating and communicating guidelines /procedures for managing supplier involvement 2 Long-term collaboration results • 3 Monitoring supplier markets and current suppliers for relevant developments 4 Pre-selecting suppliers for future involvement in NPD Short-term Project Results • Final Product Quality • Final Product Cost • Final Product Development Costs • Final Product Time-to-Market Time Operational Project Enablers 1.Cross-functional orientation purchasing and R&D (Team 2. Human Resource Qualities (Team) Operational Project Drivers 1.Degree of Project Innovation More efficient/effective future collaboration Access to suppliers’ Technology roadmap alignment • • Evaluating/feeding back supplier development performance 9 Evaluating part designs Coordinating development activities with suppliers 1 Operational Project Management Arena 7 6 Designing communication interface with suppliers Short term collaboration results Suggesting alternative technologies, components, and suppliers 2 8 - Determining desired Project-specific develop or buy solutions 3 Selecting suppliers for involvement in development project 4 5 Determining extent and moment of supplier involvement Determining operational targets and work package Fig. 1. IPDS-framework (Van Echtelt, Wynstra, Van Weele, et al., 2004). • • • • Part technical performance Part cost Part development cost Part development lead time W. van der Valk, F. Wynstra / Industrial Marketing Management 34 (2005) 681 – 694 1.Cross-functional orientation purchasing and R&D (Org.) 2. Human Resource Qualities (Org.) Results W. van der Valk, F. Wynstra / Industrial Marketing Management 34 (2005) 681 – 694 suppliers in a specific project, using the support from the strategic directions and guidelines. The two arenas are both distinct and interrelated, as the interplay between short-term project interests and long-term strategic interests are managed in these arenas. For a more detailed discussion of the respective processes, we refer to Van Echtelt, Wynstra, van Weele, et al. (2004 and Van Echtelt, Wynstra, Van Weele, Duysters, et al., 2004). The ability for and necessity of carrying out these different processes—and the most effective way of carrying them out—depends on the enabling and driving factors. As for the managerial processes, the framework distinguishes between a strategic, organizational level and an operational, project level. The most important enablers, both at the organizational and project level, are the quality of the human resources and cross-functional orientation of the purchasing and R & D functions, two of the functions most closely involved in supplier involvement in product development (Van Echtelt, Wynstra, Van Weele, Duysters, et al., 2004; Wynstra, Axelsson, & Van Weele, 2000). The driving factors for the two levels differ. At the strategic, organizational level, they include firm size, supplier and R & D dependence, and the type of manufacturing process used (Wynstra et al., 2000). The larger the firm, the more it relies on suppliers (high degree of deverticalisation), the more it relies on R & D and product innovation for creating competitive advantage, and when it uses (large-scale) assembly production, the more important managing supplier involvement in product development becomes. At the project level, the main driving factor is the degree of project innovation, as discussed earlier (Van Echtelt, Wynstra, Van Weele, Duysters, et al., 2004). 4. Benchmarking supplier involvement practices While the previous versions of the model have been developed on the basis of case studies at more than 20 firms, across 6 different industries (Wynstra, 1998), the IPDS framework in its current form has not yet been broadly applied beyond the context of an office automation manufacturer, where the framework was used to analyze several case studies in terms of the way suppliers have been involved in product development and the amount of success associated with the involvement (Van Echtelt, Wynstra, Van Weele, et al., 2004). Since the development of the framework took place within the context of a technically complex firm (e.g., high number of components, different technologies, and/or interactions between components/technologies), it is interesting to investigate the applicability of this framework in other companies and other industries. Hence, a benchmark study was set-up in order to investigate the applicability of the framework in contexts different from the one in which it was developed. This benchmark study should provide us with insights into the 685 usefulness of the framework for understanding and explaining new product development success or failure in relation to the various contingency factors. Furthermore, the results of the benchmark study should distinguish high-performing companies from low-performing ones. As it turned out, the food company in the sample performed better than did the other companies. An additional case study was carried out in Scandinavia, showing contradictory results. The framework will be used for explaining differences between these two companies. 4.1. The benchmark study Eight product development projects submitted by four Dutch companies were studied by means of the IPDS framework (Van der Valk, 2003; Van Echtelt, Wynstra, Van Weele, Duysters, et al., 2004). The methodological approach used in this benchmark study can be found in Appendix A. Because of confidentiality, the names of all companies involved in this study have been disguised. AIS is a large Analytical Instrumentation and Software supplier offering X-ray analytical equipment for both industrial and scientific applications and for the semiconductor market. The first project concerned the development of a novel system for analyzing samples using a newly developed detection technology. Four key suppliers were involved developing the detector system, a high voltage generator, a metal casing and mechatronics assembly, and an embedded software board. The second project involved increasing the capacity of an existing system for sample analyses. The key supplier in this project was involved in the development of the Fchanger_ module (a mechanical construction combined with operating software). ETS (Entrance Technology Specialist), the world market leader in the area of revolving doors and security products for the high-end market (e.g., shopping centers, airports), contributed a development project for a high-speed safetygate. One of the two key suppliers supplied a sensor system with control box; the other provided the steel construction. The second project concerned the development of two types of a high-capacity glass revolving door (one with a stainlesssteel center column and three compartments in the revolving door, the other with a steel center column and four compartments). Both center columns were developed by one supplier. FPC (Food Producing Company) is a large multi-national producer of food products. The first project concerned a carbonated soda beverage that was developed and filled in collaboration with a Spanish subsidiary of a Dutch filling firm. The second project concerned a new flavor for fruitflavored sprinkles, in which a co-pack supplier was involved for development of the flavor and production of the sprinkles. Finally, MHA is a developer and Manufacturer of personal care products and Home Appliances (e.g., shavers, coffee machines and vacuum cleaners). The first project concerned the development of a fragrance module for a vacuum cleaner for the high-end market. A consultancy 686 W. van der Valk, F. Wynstra / Industrial Marketing Management 34 (2005) 681 – 694 Table 1 Overall scores in the benchmark study on drivers*, enablers*, processes** and results*** Companies Projects Operational Strategic Operational business project project unit enablers^ drivers^ drivers^^ Strategic Operational Strategic Short-term Long-term Short-term business collaboration management management collaboration project results results results processes processes^ unit enablers^^ AIS 3.0 1.0 3.0 1.0 3.0 2.3 ETS FPC MHA Spectrometer (SM) Sample-changer (SC) Speed gate (SG) Revolving door (RD) Carbonated soda drink (SD) fruit sprinkles (FS) Vacuum cleaner (VC) Coffee machine (CM) 1.0 3.0 2.0 3.0 1.6 3.0 2.3 2.3 2.0 2.0 1.5 2.7 2.7 2.7 2.7 1.5 2.6 2.3 2.9 2.7 2.1 2.0 3.8 4.0 2.7 2.8 2.9 2.1 4.3 3.6 1.6 2.0 2.1 2.0 2.3 1.3 2.3 2.0 1.8 2.3 1.7 1.3 1.8 1.3 2.3 2.0 2.3 2.0 2.0 2.5 2.0 2.0 2.5 2.3 *: Scale: 1—low; 2—medium; 3—high. **: Scale: 1—Absent: the process is not carried out; 2—Reactive: the process is carried out in an ad hoc way, as a result of occurring events; 3—Pro-active: the process is carried out following an implicit structure or set of activities; 4—Systematic: as in Fpro-active_, but supported by systems, procedures and guidelines; 5—Intelligent: as in Fsystematic_, but able to critically review the processes in the light of the situation and to adapt (incidentally or more permanently) when necessary. ***: Scale 1—below target; 2—on target; 3—above target. ^: Informants: project leader and project purchaser. ^^: Informants: R & D manager/director and Purchasing manager/director. agency specialized in the fragrance market was involved in the development of the fragrance and of the cylinder containing the fragrance. The second project involves the redesign of a boiler for a follow-up version of a highly successful and innovative crème coffee machine. A European supplier of heating elements for kettles and coffee machines worked on the redesign of the boiler. Table 1 contains the overall results for all companies participating in this benchmark research project. 4.2. Results Below, we provide a more detailed analysis of the two food development projects of FPC, but at this point we first make a comparison between the four companies and their projects. Regarding the short-term project results, the MHA’s Vacuum Cleaner project performs best, closely followed by FPC’s Soda Drink project and AIS_ Sample Changer project. The Spectrometer project (AIS) has the lowest score in terms of shortterm project results, and also the Revolving Door project (ETS) scores below the targets set by the companies in advance of the project.2 Taking into account the collaboration results (both short-and long-term), again the Vacuum Cleaner project (MHA) and the Soda Drink project (FPC) score high (above target), whereas the other two projects submitted by these firms score on target overall. AIS’ Sample Changer project scores low in terms of long-term collaboration results. Both high-performing projects show high scores on the both the strategic and the operational management processes. MHA’s strategic management processes are considered to be pro-active to systematic; their operational management processes are charac2 Informants were asked to give their opinion on whether the targets originally set by the companies were not met, met or exceeded, with respect to the various short-term project and collaboration results and long-term collaboration results (see Fig. 1). terized as being proactive/reactive. FPC’s strategic management processes are considered to be systematic/intelligent, whereas their operational management processes are characterized as being proactive to systematic. Finally, the drivers for MHA are medium/high, whereas for FPC they are high. This would imply that FPC has to put somewhat more effort into the management processes than MHA, to achieve the same results — which they do. On the other hand, both types of management processes are facilitated because of the presence of medium/high enablers in both companies, both at the strategic and at the project level. We now take a closer look at these enablers and drivers, also for the other projects, to illustrate the general logic of our framework. 4.3. Drivers and enablers Looking in more detail at the development projects submitted by FPC and MHA, we can see in the table that the drivers for the two second projects are considered to be low/ medium. In that sense, the second projects can be considered to be less complex than the first projects, particularly because they are considered to be less innovative. Interestingly enough, this does not result in lower scores on the management processes; neither did it bring about better results. For the management processes, the explanation lies in the fact that these companies do not distinguish between more complex and less complex projects. At FPC, the fact that no distinction is made with regard to variation in product complexity is in fact a conscious decision. They prefer to adopt a uniform approach to all product development projects, in order to ensure that everyone involved in the project knows what is expected from him/her and works in a consistent manner towards project success. This finding seems somewhat contradictory to some of the previous research on the impact of project innovative- W. van der Valk, F. Wynstra / Industrial Marketing Management 34 (2005) 681 – 694 ness, which states that more innovative projects require more intensive supplier management in order to succeed (Ragatz et al., 2002). However, this does not imply that our analysis framework is wrong: although the framework allows for segmentation of highly and less innovative projects, the case results reflect the companies’ approaches to these different types of projects. Possibly, the distinction between highly and less innovative projects is not that important when it comes to product development in the food industry. This would imply that the framework looks somewhat different for this industry. The efficiency of development projects might be further increased if food companies would distinguish between these two types of projects. More research is necessary to clarify this observation. The projects submitted by AIS differ in terms of project results: results are on or above target for the Sample Changer project (except for the long-term collaboration results), but below target for the Spectrometer project. The management processes, however, score nearly the same for AIS as for MHA. An explanation for the remaining differences in project results can be found in the scores on drivers and enablers. The strategic drivers at AIS, and thus the context of the Spectrometer project, score higher than at MHA. At the operational level, the enablers in the Spectrometer project score lower than in the Vacuum Cleaner and the Coffee Machine project. Thus, the driving conditions under which the Spectrometer project was carried out were more challenging than the conditions for the Vacuum Cleaner and Coffee Machine projects, whereas the enabling conditions were less facilitating/supportive for the Spectrometer project than for the Vacuum Cleaner and Coffee Machine projects. As a result, the management processes in the Spectrometer project would have required more attention than in the Vacuum Cleaner/Coffee Machine projects in order to achieve the same results as in those projects. Vice versa, if the driving conditions are less challenging, companies could decide to spend less energy on creating the right enabling conditions, or create very supportive enabling conditions and focus less attention on the management processes. In conclusion: companies need to understand the driving conditions, as to design the enabling factors and the processes in a way that mitigates the risks associated with the drivers. Overall, we could conclude that particularly the food company excels in their approach to product development projects. In the following section, we will elaborate more on product development in the food company. Furthermore, we will contrast the results of the Dutch food company with the results of two development projects submitted by a Scandinavian food company. The results of the Scandinavian food development projects differ from those of the Dutch food development projects. By contrasting the four projects, we will demonstrate how 687 the framework can be used to understand which elements are critical for successful supplier involvement and how these are interrelated. 5. Comparing four food development projects Parallel to the benchmark study carried out in the Netherlands, an additional case study according to a similar format 3 was carried out at BCG, a leading supplier of Branded Consumer Goods to the Nordic grocery market (beverages, chemicals, detergents, food, and apparel) (Fällene, 2003). BCG’s food business is leading in the development, manufacturing and marketing of various product groups, including pizzas/pies, pickled vegetables, seafood and processed potatoes. Two divisions of BCG each submitted one project for the study: division A (seafood) submitted the development of a fish spread in combination with a new packaging. Two packaging suppliers were involved for design and production of the packaging, respectively. Furthermore, a number of ingredient suppliers were involved. Division B (pizza, pickled vegetables, potato products, et cetera) submitted a newly developed concept in the area of take-away sandwiches, involving a machine that can put together a sandwich at a customer’s order. One supplier was involved in the development of the machine: during the project, this supplier was replaced by a new supplier. Furthermore, a spice expert company was involved to develop a new meat flavor. An overview of the interviewees for these two case studies can be found in Appendix B. An overview of the overall results for the two Scandinavian and the two Dutch food projects can be found in Table 2. 5.1. Results of the Dutch development projects The first project concerned a slightly carbonated readyto-drink soda in PET bottles of 33 cl. The drink was developed and filled in collaboration with a Spanish subsidiary of a Dutch filling company. The project was highly innovative, since the method of preparation in combination with the packaging material and the manufacturing technology was new for FPC. The project was realized from scratch within a time period of five months, and is now sold through retail outlets at gas stations. The fruit-flavored sprinkles project concerns a line extension. The project was conducted with the assistance of a former sister organization of FPC and is considered to be less innovative than FPC’s other project. FPC regarded this project as an outsourcing project (more arm’s length) and thus dealt with it accordingly. The former sister 3 In the Scandinavian studies, the analysis was carried out from the buying firm’s perspective only. 688 W. van der Valk, F. Wynstra / Industrial Marketing Management 34 (2005) 681 – 694 Table 2 Overall scores of the Scandinavian and the Dutch food development projects on drivers*, enablers*, processes** and results*** Companies Projects Operational Strategic Operational Strategic Operational Strategic Short-term Short-term Long-term business project business unit management management collaboration project project collaboration unit enablers^ drivers^ enablers^^ processes^ processes results results^ results^^ drivers ^^ BCG 3.0 2.8 2.0 2.0 2.8 2.6 1.8 1.5 1.5 3.0 2.6 2.5 2.5 2.9 2.9 2.0 1.5 2.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.8 4.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.0 2.0 2.0 FPC Fish spread (FS) (division A) Take-away sandwich (TS) (division B) Carbonated soda drink (SD) Fruit sprinkles (FS) 1.0 3.0 4.0 *: Scale: 1—low; 2—medium; 3—high. **: Scale: 1—Absent: the process is not carried out; 2—Reactive: the process is carried out in an ad hoc way, as a result of occurring events; 3—Pro-active: the process is carried out following an implicit structure or set of activities; 4—Systematic: as in Fpro-active_, but supported by systems, procedures and guidelines; 5—Intelligent: as in Fsystematic_, but able to critically review the processes in the light of the situation and to adapt (incidentally or more permanently) when necessary. ***: Scale 1—below target; 2—on target; 3—above target. ^: Informants: project leader and project purchaser. ^^: Informants: R & D manager/director and Purchasing manager/director. organization owns the production line for the original version of the fruit-flavored sprinkles. The detailed results of the two development projects of FPC, and those of BCG, can be found in Table 3. These results will be discussed in detail hereafter. We can conclude that for both projects, results are on target. The Soda Drink project even exceeded the desired time-to-market. The collaboration results with the individual suppliers are directly in line with the project results. Furthermore, the long-term collaboration results are on target, and even exceed target with regard to roadmap alignment in the area of technology for drinks for the Soda Drink project. Looking back on the benchmark study, we can see that, in comparison to the other companies, both the strategic and the operational processes are well developed at FPC. Not only were they the only company in the sample to have developed and communicated guidelines and policies with regard to supplier involvement (SMP2); also they are the only company to pay attention to evaluation processes, both within the project and at the strategic level. Every project is concluded with an eye-opener meeting, in which FPC and the suppliers can mirror their own and each other’s performance. These meetings are fostered by the fact that FPC tries to create a very open relationship with their suppliers, thereby cultivating a learning environment. This has resulted in a lot of relevant insights, which can be used to further improve the processes. Where necessary and useful, these insights are fed back to strategic management, who can then decide whether and how to adapt the existing guidelines and policies. Through this step, the loops are closed. Getting these processes right has taken FPC years and this is continuing still. Clearly, this pays off. Additionally, the project and business unit enablers score high. Particularly at FPC, the position that the purchasing discipline has obtained in the organization is an important organizational enabler. Furthermore, FPC has a company culture in which employees feel it is a privilege to work on a development project. The atmosphere within the project team and the company as a whole is very positive and enthusiastic, which results in more effective collaboration— also externally. When comparing the two projects, the scores on the processes, enablers and drivers are not very different for the two projects, except for the degree of project innovation. The Soda Drink project is highly innovative, whereas the Fruit Sprinkles project is less innovative. However, FPC employs the same approach when it comes to creating conditions (operational project enablers) and carrying out the management processes. FPC deliberately chooses not to differentiate between different types of products, as to obtain standardization in the way of working and in the mindsets of people. Finally, one could argue that all the efforts put into the enablers and the processes in fact do not fully pay off, considering the fact that the project and collaboration results are all on target. This of course depends on the way targets are set. FPC themselves claim that they do generally set high expectations, and thus that an Fon target_ score actually represents high performance from the side of the suppliers.4 We conclude that the efforts invested in obtaining the right inputs and in carrying out the processes to the right extent have resulted in high supplier performance in product development. This contributes to successful project out- 4 One could argue that, given this observation, measuring performance Fcompared to target_ is not a reliable method for comparing projects across different companies. However, as this is a very common method for measuring results, even in quantitative (survey) studies, we decide to use the measurement anyway, and account for any possible differences in the Fstringency_ of target setting as we do here, to further explain possible variances, based on the in-depth interviews (see also Appendix A). Note also that we use two informants for assessing each result dimension, further contributing to our construct validity. 689 W. van der Valk, F. Wynstra / Industrial Marketing Management 34 (2005) 681 – 694 Table 3 Detailed results of the Scandinavian and Dutch food development projects on drivers*, enablers*, processes** and results*** Project Company FPC BCG Soda Fruit Fish Take-away drink (SD) sprinkles (FS) spread (FS) sandwich (TS) Product quality Product cost Development cost Time-to-market Short-term collaboration Part technical performance Part cost results^ Part development cost Part development time Long-term collaboration Alignment of technology roadmaps Improved access to supplier’s knowledge results^^ More effective and efficient future collaboration Strategic management Determining technology in-outsourcing policy Formulating and communicating guidelines for managing processes^^ supplier involvement Monitoring markets and current suppliers for relevant developments Pre-selecting suppliers for involvement in future NPD Exploiting existing suppliers’ skills and (technical) capabilities Motivating suppliers for developing skills or products Periodically evaluating guidelines and supplier base performance Operational management Determining desired develop and buy solutions processes^ Suggesting alternative technologies/components/suppliers Selecting suppliers for involvement in a project Determining extent and timing of involvement Determining development operational targets and work package Designing communication interface Coordinating suppliers’ development activities Evaluating part designs Evaluating supplier development performance Strategic BU enablers^^ Cross-functional organization Human resource quality organization Operational project Cross-functional orientation team enablers^ Human resource quality team Strategic BU drivers^^ BU Size Supplier dependence R & D dependence Manufacturing complexity Technological uncertainty Operational project drivers^ Degree of project innovation Short-term project results^ 2.0 2.0 2.0 3.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 3.0 3.0 2.0 2.0 5.0 5.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 5.0 5.0 2.0 2.0 1.0 1.0 2.0+ 2.0+ 1.5+ 1.5+ 1.0+ 2.0+ 1.5+ 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 1.0 1.0 2.0+ 2.0+ 2.0+ 2.0+ 2.0+ 2.0+ 2.0+ 2.0 2.0 4.0 4.0 2.0 3.0 4.0 3.0 4.0 5.0 4.0 4.0 3.0 4.0 4.0 5.0 4.0 3.0 5.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 4.0 3.0 4.0 5.0 4.0 3.0 3.0 4.0 4.0 5.0 4.0 4.0 5.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 1.0 3.0 3.0 2.0 4.0 2.0 4.0 4.0 2.0 3.0 2.0 3.0 4.0 1.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 2.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 4.0 3.0 3.0 4.0 3.0 2.0 3.0 2.0 3.0 4.0 2.0 2.0 3.0 2.0 3.0 3.0 2.0 2.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 Note: The scores for strategic management processes, strategic enablers and strategic drivers are the same for the two projects at FPC, as they are carried out within the same business unit. As the two projects at BCG occurred in different divisions, also the strategic processes etc. differ for the two projects. *: Scale: 1—low; 2—medium; 3—high. **: Scale: 1—Absent: the process is not carried out; 2—Reactive: the process is carried out in an ad hoc way, as a result of occurring events; 3—Pro-active: the process is carried out following an implicit structure or set of activities; 4—Systematic: as in Fpro-active_, but supported by systems, procedures and guidelines; 5—Intelligent: as in Fsystematic_, but able to critically review the processes in the light of the situation and to adapt (incidentally or more permanently) when necessary.***: Scale 1—below target; 2—on target; 3—above target. ^: Informants: project leader and project purchaser. ^^: Informants: R & D manager/director and Purchasing manager/director. +: This project included more than one supplier, and the scores refer to averages for these suppliers. comes in the form of products that conform to the predefined targets. 5.2. Results of the Scandinavian development projects In the first project submitted by division A (hereafter referred to as BCGA), a fish-spread was developed in combination with a new packaging. The development of the fish-spread was new to the firm, since its durability (shelflife) was much shorter than for their other products. This short durability at the same time caused the need for the new packaging. The product was released in 2003 (some six months later than planned) and is selling better than expected. Two suppliers were involved for the design and the production of the packaging, respectively. Additionally, some ingredient suppliers were involved. 690 W. van der Valk, F. Wynstra / Industrial Marketing Management 34 (2005) 681 – 694 The second project, submitted by division B (BCGB), concerns the development of a machine that can put together and serve a food product (for example: a sandwich) on customer-order. The project was not yet finished at the time of the study. This was the division’s first experience with closely involving suppliers in product development. Starting out with a supplier that was technically highly skilled, but not too experienced in the food industry, they had to replace the supplier by a known supplier that was experienced in the food industry. A spice expert company developed a new meat taste, to be put on the sandwich. Regarding Table 2, we can see that in both projects the desired product quality and product cost were achieved eventually, but that the development cost was much higher than targeted and the time-to-market was much longer. These project results cannot be directly traced back to the supplier results, since the suppliers have scored better with regard to development cost and development time than the project as a whole. It is important to notice though, that the scores for the short-term and long-term collaboration results are averages for the various suppliers involved in each project. Thus, some of the suppliers will have scored on target, whereas some others will have scored below target. For example, in the Take-away Sandwich project, the first machine supplier has contributed to the low scores on development time and development cost. The fact that the supplier had to be replaced caused a delay and brought about additional costs. Furthermore, the fact that the targets in the Fish Spread project were set quite low due to the level of perceived risk marginalizes the collaboration results. However, in the Take-away Sandwich project, the development of the machine has provided BCG with knowledge they did not have access to before (long-term collaboration effect). The division even discussed future developments and market trends with some of the involved suppliers. As this is the first project with intensive supplier involvement, the division has had some valuable learning experiences with regard to collaboration. Moreover, also BCG contributed to low performance with regard to the results. The scores on the management processes also demonstrate this. Both the strategic and the operational management processes are carried out reactively to proactively, with a few exceptions for some operational management processes that are considered to be intelligent. For example, in the Fish Spread project, the development of the packaging was complicated due to frequent changes at BCGA. This can be traced back to low scores on management processes. For example, the fact that ‘‘determining the desired develop-or-buy solutions’’ has not been carried out properly will have contributed to the frequent changes at BCG. The drivers score relatively high, thereby putting higher demands on the extent to which the processes are carried out. The lack of high-scoring enablers makes it all the more necessary to perform well on the processes. For example, the interfaces between the different suppliers complicated the development project: the collaboration between the two packaging suppliers sometimes was difficult due to the differences in company culture and working methods. We conclude that there seems to be room for improvement in both of BCG’s divisions. BCG does not have a predetermined frame for supplier involvement present in the organization; as a result, many of the activities that would normally be carried out in advance of projects now have to be carried out within projects. This ad hoc behavior causes various problems, which eventually result in deviations from the targets. When comparing the two companies with regard to how they approach and conduct product development activities, the differences are striking. FPC has invested a lot of effort into its management processes (both strategic and operational) and in the creation of proper development conditions, paying off in good project results. BCG on the other hand, seems to perform much more ad hoc, lacking a clear structure for involving supplier involvement in product development. The absence of a strategic perspective on supplier involvement in product development results in problems (delays, misunderstandings, mistakes, et cetera) within the individual development projects. It is interesting to note that the difference between BCG and FPC in terms of managing supplier involvement is especially large regarding the strategic processes. Consequently, BCG’s project results are not as good as those of FPC. It seems that creating suitable product development conditions and actively carrying out the relevant management processes is a requirement for successful product development.5 6. Conclusions and implications The case studies and their analyses demonstrate that the previously developed IPDS framework can usefully be applied for describing, analyzing and partly explaining failures and successes in product development in various industries; also in the food industry. Our studies find that both strategic and operational processes have an impact on development results. We also find that enablers at the business unit and project level have an impact on the possibilities of effectively and efficiently carrying out these processes. Finally, the case studies support the notion that strategic driving factors, such as company size, have an impact on the required form and extent of the strategic and operational management processes. The case studies provide little support, however, for the received notion that the degree of project innovation has an impact on the necessary 5 Bear in mind that by successful product development we mean projects of which the outputs meet or exceed pre-determined targets. Whether the project is also successful in terms of market variables as sales, market share and profitability is outside the scope of the framework. W. van der Valk, F. Wynstra / Industrial Marketing Management 34 (2005) 681 – 694 691 intensity of supplier management. This issue seems to require further research. There is a tendency among food companies to outsource the development of products as a whole to one contractor (co-packer), which subcontracts other parties when necessary. This may be compared to the use of Electronic Manufacturing Service contractors in the electronics industry. One could question whether food companies have to manage suppliers differently in order to be successful. The results of the case studies so far demonstrate that food companies go through the same cycle, as do companies in other industries. In this study, particularly the food development projects of FPC scored very well. Often, product development in the food industry is thought to be less complex, since the final product is often less complex in terms of the number of Fbuilding blocks’, as a result of which the number of suppliers is relatively small. The contribution of the individual suppliers and the coordination of these suppliers are therefore less substantial in the food than in the traditional manufacturing industry. However, this does not mean that product development in the food industry is easier than in other industries. From the case studies we can conclude that also in the food industry, complex projects come about: FPC had to make quite a lot of efforts to obtain the desired results. divide them into several sections. They also take into account the particular activities and skills required for each project. This Fstage-gate_-like model is comprehensive and deals with food in an informative way. The IPDS framework is also a generic framework, which can be adjusted as to fit the characteristics of food companies. Given the fact that the framework deals specifically with supplier involvement, we believe that our framework is a useful enhancement to the existing body of knowledge. The IPDS framework provides a comprehensive approach to product development issues in the Fextended firm_, which can definitely be transferred to the specifics of the food industry. The framework puts special emphasis on work in advance of any specific project, e.g., creating the right conditions to foster idea generation and realization (enablers) and doing thorough preliminary work on a more strategic level (developing guidelines, making the make-orbuy decision explicit, (supply) market research, et cetera). Our framework ultimately provides a kind of improvement model, enabling organizations to pinpoint the weaknesses in their product development projects and to in advance identify potential risks and improvement actions to mitigate these risks. This can make the difference between failure and success. 6.1. Contributions Thusfar, we have limited ourselves to identifying critical decision-making activities and conditions primarily from a customer perspective. However, supplier involvement is not a process that can be unilaterally managed by the customer. Additional and complementary perspectives have not explicitly been used in this study such as network and interaction approaches (Håkansson, 1987; Von Corswant & Tunälv, 2002). Still, the framework – and in particular, the processes it encompasses – are originally based on four basic underlying processes that signal a Fmeaningful_ managerial involvement of the customer (Wynstra, Weggeman, & van Weele, 2003). These processes (prioritization, mobilization, co-ordination and timing) are derived from a resource-based view of product development, and are in particular based on the work of Bonaccorsi (1992) and Håkansson and Eriksson (1993). Nevertheless, a useful extension of our framework would be to consider a set of analogous processes, enablers and drivers, but then from the perspective of the supplier. Combined with the current, customer-focused framework this could result in a more complete, dyadic framework. Furthermore, we have not focused in-depth on the change processes in these companies that allow buyer and supplier to improve their collaboration in product development. This means that defining and examining the change processes could be a next possible extension. Further investigation is also needed into the appropriate informal and formal mechanisms that enable effective learning across different departments and with suppliers in the context of stronger supplier involvement in product development. In the current Apart from its relevance per se, it may be useful to consider the framework’s relations to other product development related models developed and/or applied to the food industry. Traill and Grunert (1997) have evaluated the ideas of six new product development (NPD) theorists and their associates. Some of these theories have been developed with particular reference to the food industry and the development of new food products. These ideas are contrasted with non-food specific theorists, who are interested in the management of new products and who have recognized the important role that NPD plays in any business. Traill and Grunert (1997) found that there is little consensus as to the right and wrong way to manage the process of product development. They therefore advocate that an organization should not be tied to one particular model, but should take on board the basic fundamentals of a food-based model (theory) and adapt and amend it to their particular situations as and when they develop new food products. Existing models for product development in the food industry are quite similar to the traditional stage-gate models used in the context of manufacturing companies; these models are slightly adapted to enhance the fit of the model to the specifics of the food industry. For example, Graf and Saguy (1991) propose, somewhat arbitrarily, to divide a typical project into five steps and then proceed to 6.2. Limitations 692 W. van der Valk, F. Wynstra / Industrial Marketing Management 34 (2005) 681 – 694 study we observed that one of the potential benefits of starting to involve suppliers in product development is the potential for learning, making future collaborations less resource-consuming and more effective. Still, many companies make the same mistakes over and over again. We therefore argue that visible evaluation processes need to be in place at different organizational levels to allow learning experiences to be passed on. The main finding of the current study, however, is that there is initial support for the claim that our analytical framework regarding the results, processes and pre-conditions of supplier involvement in product development is also applicable in the food industry. As such, our study, which we believe to be the first one to explicitly address supplier involvement in this industry, suggests that potentially useful lessons may be learned not only from, but also by this industry by comparing its practices with those applied in other industries. The differences between industries in this respect are usually smaller than expected. Acknowledgement The authors wish to acknowledge the support from Sara Fällene and Ferrie van Echtelt in executing the field work, and the useful comments by the reviewers and participants at the 2004 Annual IMP Conference. Appendix A. Methodology In the benchmark study, data was collected by means of questionnaires and extensive semi-structured interviews. Based on preliminary research, two complementary questionnaires were designed and extensively pre-tested. The first, strategic questionnaire, dealt with long-term collaboration results, strategic management processes and strategic/ business unit drivers and enablers, and was sent to the companies’ purchasing managers and R & D/development managers. The second, operational questionnaire dealt with the short-term project and collaboration results, operational processes and project drivers and enablers, and was sent to the people directly involved in the product development project under study, e.g., the project leader and the project purchaser. At the same time, a case protocol was developed for carrying out face-to-face interviews with all people that answered the questionnaire. During the interview, the project history, the management processes and project’s conditions were discussed in more detail. Additionally, representatives of the suppliers involved were interviewed. The person representing the commercial interface and the person involved in the technical development were interviewed, to add to our understanding of the project and its results. The interviews were recorded and were transcribed, after which they were returned to the interviewees for verifica- tion. The transcripts were also discussed within the research team, as to enhance the validity of the findings. The questionnaires’ scores were used as a starting point for assigning scores to the project’s processes, enablers and drivers; in case of discrepancies between different informants, the follow-up interviews were used for clarification. In case the data from the questionnaires was inconsistent with the data from the interviews, a follow-up took place with the case company, after which a final decision was made after carefully considering all data. Likert scales were used to score the processes, enablers and drivers, which enabled cross-case comparison. For the management processes, a five-point Likert scale, adapted from an existing scale for assessing organizational maturity of suppliers (Praat & Krebbekx, 2000), was used to assess the degree of active and systematic execution of the processes. The scale has the following labels: 1— Absent: the process is not carried out; 2—Reactive: the process is carried out in an ad hoc way, as a result of occurring events; 3—Pro-active: the process is carried out following an implicit structure or set of activities; 4— Systematic: as in ‘‘pro-active’’, but supported by systems, procedures and guidelines; 5—Intelligent: as in ‘‘systematic’’ but able to critically review the processes in the light of the project and to adapt (incidentally or more permanently) when necessary. The drivers and enablers were scored on a three-point Likert scale. For both inputs, the labels were defined as: 1— Low; 2—Medium; and 3—High. Finally, the outputs were also scored on a three-point Likert scale: 1—Below target; 2—On target; and 3—Above target. Overall, we adopted the following methods to ensure the validity of the case studies (based on Yin, 2003): n Construct validity (‘‘establishment of correct operational measures for the concepts being studied’’): : Triangulation of questionnaire and interview data : Triangulation of multiple informants: different internal representatives, supplier representatives : All informants received draft versions of the interview report for comments : Draft versions of the complete case report were verified with at least one key informant from each buying firm : Three research team members gave input during data collection and analysis n Internal validity (‘‘establishing causal relationships whereby certain conditions are shown to lead to other conditions, as distinguished from spurious relationships’’): : Use of theoretical model / analysis framework n External validity (‘‘establishing a domain in which the study’s findings can be generalized’’): : Theoretical sampling of cases at two levels of analysis: strategic (firm) and operational (project) level n Reliability (‘‘demonstrating that the operations of a study can be repeated with the same results’’): : Development of questionnaire : Development of case protocol W. van der Valk, F. Wynstra / Industrial Marketing Management 34 (2005) 681 – 694 693 Appendix B . Overview of interviewees BCG Project Both Functions Internal interviews Project leader Project purchaser R & D director Purchasing director FPC Project Carbonated soda drink Both Internal interviews Supplier interviews Internal interviews Functions Project Marketing/project leader Project purchaser Technical engineer Fruit-flavoured sprinkles Functions Internal interviews Supplier interviews Development/project leader Project purchaser Product developer New business development manager Europe European purchasing manager co-pack References Anderson, J., & Woolley, M. (2002). Towards strategic sourcing: The Unilever experience. Business Strategy Review, 13(2), 65 – 73. Birou, L. M. (1994). The role of the buyer – supplier linkage in an integrated product development environment. Unpublished doctoral thesis. Michigan State University. Bonaccorsi, A. (1992). A framework for integrating technology and procurement strategy. Conference proceedings of the 8th IMP conference (pp. 33 – 41). Lyon. Clark, K. B. (1989). Project scope and project performance: The effects of parts strategy and supplier involvement on product development. Management Science, 35(10), 1247 – 1263. Eisenhardt, K. M., & Tabrizi, B. N. (1995). Accelerating adaptive processes: Product innovation in the global computer industry. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40, 84 – 110. Fällene, S. A. (2003). Supplier involvement in product development. Unpublished Master thesis Linköping University (research carried out at Department of Technology Management Technische Universiteit Eindhoven). Graf, E., & Saguy, I. (Eds.) (1991). New product development: From concept to the market place. New York, NY’ Van Nostrand Reinhold (AVI). Håkansson H. (Ed.) (1987). Industrial technological development. London’ Croom Helm. Håkansson, H., & Eriksson, A. K. (1993). Getting innovations out of supplier networks. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing, 1(3), 3 – 34. Hartley, J. L., Zirger, B. J., & Kamath, R. R. (1997). Managing the buyer – supplier interface for on-time performance in product development. Journal of Operations Management, 15(1), 57 – 70. Hingley, M., & Hollingsworth, A. (2003). Competitiveness and power relationships: Where now for the UK food supply chain? Conference proceedings of the 19th Annual IMP Conference Lugano, Switzerland. Hingley, M., & Lindgreen, M. (2004). Supplier – Retailer relationships in the UK fresh produce supply chain. Conference proceedings of the 20th Annual IMP Conference Copenhagen, Denmark. McGinnis, M. A., & Vallopra, R. (1999). Purchasing and supplier involvement: Issues and insights regarding new products success. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 35(3), 4 – 15. Monczka, R. M., Handfield, R. B., & Scannell, T. V. (2000). Product development: Strategies for supplier integration. Milwaukee’ ASQ Quality Press. Praat, H., & Krebbekx, J. (2000). De nationale t and u agenda: Branche roadmaps voor de toeleveringsindustrie. Berenschot Press Conference ESEF (in Dutch). Ragatz, G. L., Handfield, R. B., & Petersen, K. J. (2002). Benefits associated with supplier integration into product development under conditions of technology uncertainty. Journal of Business Research, 55(5), 389 – 400. Ragatz, G. L., Handfield, R. B., & Scanell, T. V. (1997). Success factors for integrating suppliers into product development. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 14(3), 190 – 203. Rudolph, M. (1995). The food production development process. British Food Journal, 97(3), 3 – 11. Souder, W. E., Sherman, J. D., & Davies-Cooper, R. (1998). Environmental uncertainty, organisational integration and product development effectiveness: A test of contingency theory. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 15, 520 – 533. Traill, B., & Grunert, K. G. (1997). Product and process innovation in the food industry. Netherlands’ Blackie Academic and Professional. Van der Valk, W. (2003). Diagnosing supplier involvement in product development: Study on how to identify opportunities for improving supplier involvement. Unpublished Master thesis. Department of Technology Management, Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. Van Echtelt, F., Wynstra, F., & van Weele, A. J. (2004). Critical processes and conditions for managing supplier involvement in new product development. Internal working paper, Eindhoven Centre for Innovation Studies, Department of Technology Management. Netherlands’ Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. Van Echtelt, F., Wynstra, F., Van Weele, A. J., & Duysters, G. M. (2004, April). Critical processes for managing supplier involvement in new product development: An in-depth multiple-case study. ECIS working paper 04.07, Eindhoven Centre for Innovation Studies, Department of Technology Management. Netherlands’ Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. 694 W. van der Valk, F. Wynstra / Industrial Marketing Management 34 (2005) 681 – 694 Verhoef, P. C., Nijssen, E. J., & Sloot, L. M. (2002). Strategic reactions of national brand manufacturers towards private labels: An empirical study in the Netherlands. European Journal of Marketing, 36(11/12), 1309. Von Corswant, F., & Tunälv, C. (2002). Coordinating customers and proactive suppliers: A case study of supplier collaboration in product development. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 19(3/4), 249 – 261. Weston, J. F., & Chiu, S. (1996). Growth strategies in the food industry. Business Economics, 31(1), 21. Wynstra, F., 1998. Purchasing Involvement in Product Development, doctoral thesis. Eindhoven University of Technology Eindhoven Centre for Innovation Studies Eindhoven. 320 pp. Wynstra, F., Weggeman, M., & van Weele, A. J. (2003). Exploring purchasing integration in product development. Industrial Marketing Management, 32(1), 69 – 83. Wynstra, J. Y. F., Axelsson, B., & Van Weele, A. J. (2000). Driving and enabling factors for purchasing involvement in product development. European Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 6(2), 129 – 141. Wynstra, J. Y. F., van Weele, A. J., & Axelsson, B. (1999). Purchasing involvement in product development: A framework. European Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 5(3 – 4), 129 – 141. Wynstra, J. Y. F., van Weele, A. J., & Weggeman, M. (2001). Managing supplier involvement in product development: Three critical issues. European Management Journal, 19(2), 157 – 167. Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd edition). Thousand Oaks’ Sage Publications.