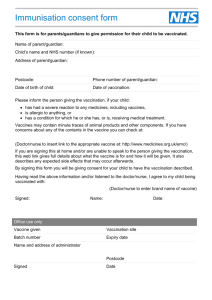

SCHOOL OF MEDICINE AND HEALTH SCIENCES UPTAKE OF COVID-19 VACCINES: EXPERIENCES OF HEALTH CARE WORKERS AT PETAUKE DISTRICT HOSPITAL BY DEAN FRED LUPUPA MWENYA BSPH19114548 BSc PUBLIC HEALTH SUPERVISOR: DR LYDIA HANGULU A research Dissertation submitted to the University of Lusaka in partial fulfilment of the requirements of a Degree in Bachelor of Science in Public Health DECLARATION/APPROVAL Student declaration I, Dean Fred Lupupa Mwenya, Student Number: BSPH19114548, School of Health Sciences, University of Lusaka, hereby declare that my proposal is entirely unique to me and has not been submitted to, or been considered for certification by, any other university or institution. All sources used herein have been dully acknowledged and cited using the current Harvard System and in compliance with anti-plagiarism standards. Date: 8th November, 2022 Signature: Supervisor approval I...Dr Lydia Hangulu... I hereby attest that I have read and assessed this project proposal. In my capacity as the University supervisor, I hereby acknowledge that this proposal has been submitted for evaluation with my approval. Signature Date: 10th November, 2022 ii DEDICATION I wish to dedicate this research to my Dad, Mr Fred Kelvin Mwenya, my forever hero. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost all gratitude goes to Almighty God for being my source of inspiration and direction throughout my time spent pursuing this Program. I would also like to extend my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Dr Hangulu for your valuable and timely guidance during the development of this research. Further, I extend my gratitude to all the lecturers who carried me through all the years at University of Lusaka, in particular Mrs Musonda Mubanga, our research “coach”, kudos to you Madam. My appreciation also goes to all the participants who offered their valuable time and input by participating in this study. Lastly, my appreciation goes to my fellow students, with whom we started this course, “our study posse”, Sylvana Mulikita, Victoria Kaunda, Ngoza Phiri, Genaroza, Pauline and Ilukena. iv ABSTRACT Background: Health-Care workers (HCWs) are among the people who are most at risk of contracting COVID-19 because of their occupational exposure. Healthcare workers may comprise of cadres such as medical doctors, laboratory technicians, etc. HCWs are expected to be the first to embrace the COVID-19 vaccine since they are at very high risk due to their high occupational exposure to patients on a daily basis—deaths of Health Care Workers due to COVID-19 have been recorded. However, there is an apparent apathy for Health Care Workers taking the vaccine, and so this study aimed to outline the experiences of Health Care Workers at Petauke District on the uptake of COVID-19 vaccines. This is expected to provoke a thought and behavioural change as the knowledge gained is availed to the relevant authorities. Methodology: This was a qualitative case study design whose study site was Petauke District Hospital in Petauke District of Eastern Province. The population comprised of 30 Health Care Workers (6 from ART Department, 2 from Laboratory, 2 from Dental Department and 20 from Out Patient Department). Purposive sampling was used to select the participants using a researcher administered structured interview guide adapted from the World Health Organisation. The data was examined using thematic analysis. The steps that the researcher followed in thematic analysis are familiarizing the data, generating initial codes, defining and naming interpretive codes for the entire data set into themes, identifying patterns across all data to derive themes for the data set, defining and naming themes, and concluding analysis. Results: Most of the HCWs expressed concerns of getting COVID-19, they expressed having negative feelings, such as fear, anxiety. Fear was the major feeling expressed; that is fear of getting the virus since they work in close contact with patients who may be infected, fear of dying from the virus, fear of it being severe and fear of passing it on to relatives, friends and patients. However, on a positive note, some participants advocated for all people to get vaccinated which would help lessen the spread of the virus. In addition, The HCWs had experience hearing negative information from various sources, such as the community, social media such as on Facebook, bloggers, etc. This negative information was mostly in form of myths, which led to some HCW being nervous about getting the vaccine. On a positive note, when asked about the safety of the vaccines the emerging themes were that the vaccines are safe as they are a good option from preventing COVID-19, reducing the severity of the cases when infected and reducing the number of new cases. Conclusions: The uptake of the COVID-19 vaccines was determined to be high, 28 (93%) of the Health Care Workers (HCWs) were vaccinated with only 2 not being vaccinated. A comparable study conducted in Uganda (Katonsa et al., 2021) found that more than 70% of people accepted the vaccine. However, this confidence needs to be maintained by ongoing, focused public health education and HCWs sensitization seminars. v Table of Contents DECLARATION/APPROVAL ..............................................................................................ii DEDICATION........................................................................................................................ iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................... iv ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................................. v LIST OF ACRONYMS .......................................................................................................... ix LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................... x LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................ xi CHAPTER ONE ...................................................................................................................... 1 1.0 Background/Introduction .......................................................................................... 1 1.1 Statement of the problem ........................................................................................... 4 1.2 Justification of the study ............................................................................................ 4 1.3 General research objective ........................................................................................ 5 1.4 Specific research objectives ....................................................................................... 5 1.5 Research questions ..................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER TWO ..................................................................................................................... 6 2.0 Literature review ........................................................................................................ 6 2.0.1 Origins of COVID-19 .............................................................................................. 6 2.0.2 Global, Regional and National Coverage of Covid-19 ......................................... 7 2.0.3 Global, Regional and National impact of Covid-19 .............................................. 9 2.0.4 How the world is fighting against COVID-19 ..................................................... 10 2.0.4.1 Maintaining physical Distance. ......................................................................... 11 2.0.4.2. Contact Tracing ................................................................................................. 11 2.0.4.3 Getting Tested ..................................................................................................... 11 2.0.4.4 Surge Capacity in Hospitals............................................................................... 11 2.0.4.5 Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Supply ................................................. 12 2.0.4.6 Clear Communication ........................................................................................ 12 2.0.4.7 Quick and Decisive Action ................................................................................. 12 2.0.5 The COVID-19 Vaccines ....................................................................................... 13 2.0.6 “For” or “Against” getting the COVID-19 Vaccine ........................................... 14 2.1 Theoretical Framework ........................................................................................... 16 2.2 Conceptual framework............................................................................................. 18 .................................................................................................................................................. 18 CHAPTER THREE ............................................................................................................... 22 Methodology .................................................................................................................... 22 vi 3.1 Study Approach ........................................................................................................ 22 3.2 Study design .............................................................................................................. 22 3.3 Study population/Target population ....................................................................... 22 3.4 Sample size, sampling procedures ........................................................................... 23 3.5 Data collection methods ........................................................................................... 24 3.6 Data analysis ............................................................................................................. 24 3.7 Ethical considerations .............................................................................................. 24 CHAPTER FOUR .................................................................................................................. 26 4.0 Results ............................................................................................................................... 26 4.1 Socio-demographic details of the participants ....................................................... 26 4.2 What are the experiences of Health Care Workers that have been vaccinated and those that have not been vaccinated on the uptake of COVID-19 Vaccines at Petauke District Hospital? ............................................................................................. 26 4.2.1. Tell me about your concerns about acquiring COVID-19. ............................... 27 4.2.2 What are your thoughts on the COVID-19 vaccine?— Have you heard something which makes you nervous?— Where did you get this information? ....... 28 4.2.3 What are your opinions on the vaccine's safety and newness of the vaccines? 29 4.2.4 How much do you trust the health care person who will administer the vaccine?............................................................................................................................ 30 4.3 What are the reasons why some healthcare workers have not been vaccinated yet at Petauke District Hospital..................................................................................... 31 4.4 What are some of the experiences from the Health Care Workers that can promote the increase in the uptake of COVID-19 vaccines at Petauke District Hospital. ........................................................................................................................... 32 4.4.1 What would make getting a COVID-19 vaccination easier for you if it was recommended and available? ........................................................................................ 33 CHAPTER FIVE ................................................................................................................... 34 5.0 Discussion .................................................................................................................. 34 5.1 Limitations ............................................................................................................... 36 CHAPTER SIX ...................................................................................................................... 37 6.0 Conclusion and Recommendations ......................................................................... 37 6.1 Recommendations ..................................................................................................... 37 REFERENCES ....................................................................................................................... 39 APPENDICES ........................................................................................................................ 49 Appendix 1: Data collection tool: Qualitative Interview Guide ................................ 49 Appendix III: Consent Form ......................................................................................... 52 Appendix IV: Work plan ............................................................................................... 53 vii Appendix V: Budget ....................................................................................................... 54 Appendix VI: UNILUS Letter ....................................................................................... 55 Appendix VII: NHRA Approval Letter........................................................................ 57 viii LIST OF ACRONYMS CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 Corana Virus Disease 2019 DNA Deoxyribonucleic Acid ELISA Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay HCW Health-Care workers PCR Polymerase Chain Reaction SARS Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome SARS-CoV-2 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 WHO World Health Organization EUL Emergency Use Listing PPE Personal Protective Equipment PTSD Post Traumatic Stress Disorder OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development UNICEF United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund ix LIST OF TABLES Table 2.0.1 COVID-19 Myths vs COVID-19 Facts Table 4.1 Socio-demographic details of the participants x LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1.0 Confirmed COVID-19 Cases in Zambia (Daily) Figure 2.0.1 Global and Regional Coverage of COVID-19 Figure 2.0.2 District level distribution of COVID-19 cases in Zambia as of 17/07/ 2020 Figure 2.2.1 Conceptual Framework Figure 4.1 Word Cloud: HCW’s concerns about getting COVID-19 (Source: NVIVO version 10) Figure 4.2 Word Cloud: HCWs’ thoughts about the COVID-19 Vaccines (Source: NVIVO version 10) Figure 4.3 Word Cloud: HCWs’ opinions on the safety of the COVID-19 Vaccines (Source: NVIVO version 10) Figure 4.4 Word Cloud: HCWs’ trust of the HCW giving the COVID-19 Vaccines (Source: NVIVO version 10) Figure 4.4 Word Cloud: HCWs’ Experiences COVID-19 Vaccines Uptake (Source: NVIVO version 10) xi CHAPTER ONE 1.0 Background/Introduction Late in December 2019, China reported a viral pneumonia outbreak in Wuhan, Hubei Province, which quickly expanded to neighbouring locations (Pan, et. al., 2020; Ai, 2020). COVID-19 caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a global concern and has become a substantial health hazard since the number of infected people and affected nations has increased quickly, (Cheng and Shan, 2020). COVID-19 was named as a pandemic by the World Health Organization on 11th March, 2020, with over 68 million cases registered worldwide as of December 8, with over 1.5 million deaths reported and over 47 million recoveries in 218 countries across the globe (Cheng and Shan, 2020). The very first incidences of COVID-19 in Zambia were in a husband and wife who visited Europe, France to be specific and were exposed to port-of-entry observation and subsequent remote monitoring of passengers with a history of foreign travel for a fortnight (14 days) after arrival. They were pinpointed as having probable cases on 18th March, 2020, after developing symptoms throughout the 14-day surveillance period and were tested for COVID-19 (CDC, 2020). The second case was that of a local businessman who had visited Pakistan. Initially, the majority of cases were linked to international travel or the travellers’ household contacts. Infections among overland travellers, notably truck drivers going across the Tanzanian border, became a source of worry as a result (CDC, 2020). From the first reported case, to date (2022) there has been an upward and downward trend in COVID-19 cases and subsequent deaths as Figure 1.0 shows. 1 Figure 1: Confirmed COVID-19 Cases in Zambia (Daily) (source: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus/country/zambia) Accessed on 25/02/2022. Health-Care workers (HCWs) are among the people who are most at risk of contracting the disease because of their occupational exposure (Sebetian, et. al., 2021). Healthcare workers may comprise of cadres such as medical doctors, laboratory technicians, etc. This may also include Non-medical support staff such as financial workers, human resource workers, cleaners, Community Based workers and others (Sebetian, et. al., 2021). Previous outbreaks of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), took a toll on HCWs. During the SARS epidemic in 2002, WHO recorded 8098 cases and 774 (9.6%) fatalities, with HCWs accounting for 1707 (21%) of the cases. Furthermore, Singapore revealed that healthcare workers were responsible for 41% of the 238 probable SARS cases (Sebetian, et. al., 2021). With the ongoing COVID-19 epidemic, occupational contact among HCWs is one of the major risk factors for getting COVID-19for HCWs (Sebetian, et. al., 2021). At a local scale, Fwoloshi, et al., (2020) conducted a cross-sectional survey in 20 health centres in 6 districts in order to determine COVID-19 prevalence among Zambian HCWs in the month of July 2020. Participants got examined for the presence of the COVID-19 virus and antibodies 2 using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, respectively (ELISA). For each test, estimates of prevalence and 95 percent confidence intervals (CIs) were computed independently, adjusted for health facility clustering, and a composite measure for individuals who had PCR and ELISA was done. (Fwoloshi, et al., 2020). From their study, there were 660 HCWs in total, out of which 450 (68.2%) submitted a nasopharyngeal swab for PCR and 575 (87.1%) supplying a blood sample for ELISA. Sixtysix percent of those who took part were female, with a median age of 31.5 years (interquartile range, 26.2-39.8). The combined measure's total prevalence was 9.3 percent (95 percent CI, 3.8 percent -14.7 percent ). COVID-19 PCR positivity was 6.6 percent (95 percent confidence interval: 2.0 percent-11.1 percent), while ELISA positivity was 2.2 percent (95 percent CI, .5 percent -3.9 percent )Fwoloshi, et. al, 2020). During a phase of community transmission in Zambia, Fwoloshi et al. (2020) concluded that COVID-19 prevalence among HCWs was identical to a population-based estimate (10.6 percent). Even though key interventions like social distancing, isolation, and quarantine are helpful in preventing COVID-19 from spreading, symptomatic individuals are treated with remdesevir, supplemental oxygen, anticoagulants, etc. (Kashif, et. al., 2021). The only long-term therapy for SARS-CoV-2 is vaccination. Several vaccines have been developed, including Moderna Inc.'s mRNA-based vaccine, CanSino Biologics' non-replicating vector-based vaccine, Novavax's, Covigenix VAX-001, and COVIGEN, protein subunit vaccine, and many more (Kashif, et. al., 2021). However, in many places, getting people to take a COVID-19 immunization is difficult (Kashif, et. al., 2021). “Vietnam (98%), China (91 %), India (91%), South Korea (87%) and Denmark (87%), had the highest COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rates in the general population, while Paraguay (51%), France (44 %), Lebanon (44%), Croatia (41%), Serbia (38%), and had the lowest” (Shmidt, et al., 2021). HCWs, who play a critical role in decreasing the pandemic's burden by modelling preventive behaviour and giving immunizations, have also reported high levels of hesitation around the world (Shmidt, et al., 2021). Zambia got 228,000 doses of COVID-19 vaccines on 12th April, 2021 as its first batch of vaccines. The COVID-19 vaccination campaign was launched 2 days later by Minister of Health Dr. Jonas Chanda. The objective was to vaccinate 8.4 million persons aged 18 and up 3 (CDC, 2021). Because of the severe difficulty of vaccine hesitancy, which is not unique to Zambia, only 142,000 individuals had been vaccinated with dose 1 of the COVID-19 vaccine on July 5, 2021, and only 23,000 people were fully vaccinated (CDC, 2021). According to Reuters (2022), Zambia has provided at least 2,822,009 doses of COVID vaccinations as of February 27, 2022. If each individual requires two doses, that would be enough to vaccinate 7.9% of the country's population. This proportion is still quite low, given the country's population of about 18.4 million people as of mid-2020, 44 percent of whom were under the age of 15 (Demographic dividend, 2020). 1.1 Statement of the problem The COVID-19 virus or coronavirus, since its being discovered in China, quickly spread to other countries of which Zambia has not been spared. Many deaths have so far been recorded globally and locally. As of 8th December, 2020, way above 68 million cases of COVID-19 were documented globally, with over 1.5 million patients dying. This led to companies moving in quickly to make Covid vaccines which were not available to developing countries, but, thankfully are now available even in Zambia. However, the speed at which these vaccines were developed and approved for use, plus some other prevailing myths has also brought about apathy towards people getting vaccinated (CDC, 2021). Health workers are expected to be the first to embrace the COVID-19 vaccine since they are at very high risk due to their high occupational exposure to patients on a daily basis—deaths of Health Care Workers due to COVID-19 have been recorded (WHO, 2021). However, there is an apparent apathy for Health Care Workers taking the vaccine, and so this study aimed to outline the experiences of Health Care Workers at Petauke District on the uptake of COVID19 vaccines. This is expected to provoke a thought and behavioural change as the knowledge gained is availed to the relevant authorities. 1.2 Justification of the study Health Care Workers are considered as frontline staff in the health sector which increases their occupational exposure and risk of infection to infectious diseases such as COVID-19. In light of this they are expected to embrace positive preventive measure such as the current vaccinations going on in the country against COVID-19 and also be the carriers of a positive 4 message for all who are in their care to follow suit. This research, is therefore aimed at exposing the outstanding perceptions against the COVID-19 Vaccination amongst Health Care Workers which may promote the creation of targeted messages and trainings for Health Care Workers concerning the importance of getting vaccinated against COVID-19. This in turn may trickle down to the general public who are even more apathetic to getting the COVID-19 Vaccine. 1.3 General research objective To outline the experiences of Health Care Workers at Petauke District on the uptake of COVID-19 vaccines. 1.4 Specific research objectives 1) To explore the experiences of Health Care Workers that have been vaccinated and those that have not been vaccinated on the uptake of COVID-19 Vaccines at Petauke District Hospital. 2) To understand the reasons why some healthcare workers have not been vaccinated yet at Petauke District Hospital. 3) To discover some experiences from the Health Care Workers that can promote the increase in the uptake of COVID-19 vaccines at Petauke District Hospital. 1.5 Research questions 1) What are the experiences of Health Care Workers that have been vaccinated and those that have not been vaccinated on the uptake of COVID-19 Vaccines at Petauke District Hospital. 2) What are the reasons why some healthcare workers have not been vaccinated yet at Petauke District Hospital. 3) What are some of the experiences from the Health Care Workers that can promote the increase in the uptake of COVID-19 vaccines at Petauke District Hospital. 5 CHAPTER TWO 2.0 Literature review This chapter presents a review of the literature that is relevant to this study. 2.0.1 Origins of COVID-19 Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), according to Adhikari et al. (2020), is a highly infectious illness triggered by the SARS-CoV-2 virus that can cause fever, breathing difficulty, lung infection and pneumonia. According to Adhikari et al. (2020), these viruses are common in animals all over the world, but just a few cases have been documented in humans. On the other hand, according to WHO (2021), the Huanan marketplace in Wuhan was the original and large epicenter of SARS-CoV-2 infection, as inferred from epidemiological data. In December 2019, 55 percent of cases were exposed to the Huanan or other Wuhan markets, with these instances being more widespread in the early part of the month (WHO, 2021). As to whether SARS-CoV-2 could have escaped from a laboratory, Holmes et al., (2021) refute this claim, claiming that no epidemic has ever been caused by a laboratory novel virus, and no evidence exists that the WIV—or some other laboratory—was operating on SARSCoV-2, or another virus similar enough to be the progenitor, before the COVID-19 pandemic. Viral genomic sequencing without cell culture, which had been regularly conducted at the WIV, poses a minor risk, because viruses are inactivated during RNA extraction, according to Holmes et al., (2021). In their report, CRS (2021) put forward four (4) possible origins of the COVID-19Virus, some of which are in agreement with the preceding assertions. (1) An intermediate host species infected by an animal reservoir carrier (the animal in which the virus lives, develops, and multiplies) conveyed the virus to humans, according to a "likely-to-very-likely" scenario. No intermediate hosts, however, have been discovered (CRS, 2021). (2) Direct zoonotic spillover, a "possible-to-likely" mechanism for SARS-CoV-2 transmission out of an animal reservoir host to a person. Several studies have demonstrated substantial genetic similarities between SARS-CoV-2 and coronaviruses identified in some bat species prevalent in China and elsewhere in South Asia, making bats a plausible reservoir host (CRS, 2021). 6 (3) Infection via cold/food-chain items, a "possible" idea that persons got SARS-CoV-2 after coming into touch with infected food, which might include frozen, imported foods. SARSCoV-2 has been found in frozen foods, their packaging, and cold-chain goods (CRS, 2021). (4) An "very implausible" possibility is that SARS-CoV-2 was accidently infected and transmitted by laboratory employees while investigating coronaviruses in bats. The WHO study said that the possibility of the virus being purposefully disseminated was ruled out by several scientists. In the end, the researchers were unable to pinpoint the origins of SARSCoV-2 and urged that more research be conducted. In addition, the panel recommended for frequent administrative and internal evaluations of high-level biosafety facilities throughout the world to address what they described as a data shortage (CRS, 2021). 2.0.2 Global, Regional and National Coverage of Covid-19 According to WHO (2022), “Globally, as of 7:33pm CET, 18th March, 2022, there have been 464,809,377 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 6,062,536 deaths, reported to WHO”. Figure 2.1 shows the breakdown of the total global confirmed cases of COVID-19 by region; “Europe: 191, 842,819; Americas: 149,435,827; South-East Asia: 56, 667,275; Western Pacific: 36,865,816; Eastern Mediterranean: 21, 478, 988; and Africa: 8,517, 888” (WHO, 2022). Figure 2.0.1 Global and Regional Coverage of COVID-19 (Source: WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard, Accessed: 18th March, 2022) 7 The COVID-19 pandemic spread across Africa on 14th February, 2020, according to Kaseje, Dong, and Gardner (2020). The first confirmed case was recorded in Egypt. Kaseje (2020) goes on to say that the majority of the cases detected in Africa during the early manifestation of the pandemic were claimed to have come from three places: the USA, Europe, and China. Africa had reached 200,000 cases by mid-June, with Egypt, South Africa, Ghana, Algeria and Nigeria, accounting for 70% of the total (Dong and Gardner, 2020). With respect to Zambia Simulundu, et al., (2020) reported that on March 18, 2020, the first two instances of COVID-19 were imported from France. According to Osakwe (2021), Zambia had showed minimal cases and fatalities in the first 6 months of 2020, but this increased dramatically after 6 months of the year 2020, with the amount of cases soaring from 1,594 just at the close of June 2020 to 20,727 by the conclusion of the year. By 6th April, 2021, the total cases had moved to 89, 009, continuing the upward trend. He went on to say that the number of fatalities had followed a similar increasing trajectory, moving from 24 at the close of June 2020 to 1,222 on 6th April, 2021. (Osakwe, 2021). Science-direct (2020) took the liberty of summarizing the COVID-19 Coverage in Zambia as at 17th July, 2020 using figure 2.2 Figure. 2.0.2 District level distribution of COVID-19 cases in Zambia as of 17/07/ 2020 (Modified from the Ministry of Health daily reports). (Source: 8 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2468227621001319; Accessed: 15th March, 2022). 2.0.3 Global, Regional and National impact of Covid-19 Beyond the physical and human tragedy of COVID-19, the OECD (2020) regrets that it is now widely acknowledged that the epidemic produced the most devastating economic catastrophe since World War II. Disturbed global supply chains, decreased demand for imported products and services, a reduction in international tourism, a decrease in business travel, and most commonly a mix of these, according to the OECD (2020). Small and Medium Enterprises have been seriously affected by the virus's containment measures (OECD, 2020). Altena et al., (2020) agrees with the OECD (2020) that the global spread of the virus is a significant global health catastrophes in history (one of such), with huge socioeconomic consequences. Whereas the health effects are directly linked to the spread of the disease, according to Altena et al. (2020), the economic effects are mostly a result of the preventative actions which were undertaken by the individual governments to try and bring it to a stop. Most nations had implemented partial or total economic lockdowns and border closures to prevent the spread, which led to the temporary suspension of schools, companies, and social services, etc (Altena et al., 2020). However, Altena et al., (2020) laments that these policies have caused serious losses for economies of Africa, specifically in terms of lost productivity and internal and external trade. These policies imposed substantial strain on virtually all of many countries' essential growthenhancing industries, as well as their total revenue (Altena et al., 2020). Health Care Workers (HCWs) around the globe are the most concerned, according to WHO (2021), because the pandemic has increased the risk of occupational exposure to a new super fast spreading disease and necessitated the adaptation of responsibilities and roles for a wide variety of tasks and professional fields. Furthermore, the pandemic caused several diseases and fatalities among HCWs and their families. Mixed analysis methods identify a range of 80 000 to 180 000 deaths worldwide, with a central population-based estimate of 115 500 deaths, based on the International Labour Organization's estimated total of 135 million HCWs engaged in human health and social activities and WHO monitoring data on all deaths reported to be due to COVID-19 (WHO, 2021). Those working or contracted in the health-care sector suffer many 9 dangers that influence their physical, emotional, and social well-being, making it one of the most severely affected by the epidemic. HCWs have been shown to have a greater risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection than the overall population (WHO, 2021). Stress, worry and sadness, alcohol use, eating challenges, starvation, and not being able to predict the future are some of the initial mental health problems linked to the COVID-19 pandemic, according to Altena et al., (2020). On the other side, Wu and McGoogan (2019) discovered traumatic events associated with the death of peers and relatives, job pressures, social status, and COVID-19 symptoms. Anxiety, despair, sleeplessness, or other societal issues such as an increase in violence against gender (GBV) during the lockdown might increase the need for short-term mental health care (Altena et al., 2020). Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), sleeplessness, generalized anxiety disorder, and terror are all likely outcomes of a worldwide epidemic that has infected about 10 million individuals and killed more than half a million (Altena et al., 2020). COVID-19 has had a detrimental influence on the Zambian economy, according to Tembo (n.d.), owing to the loss of job, money, and in some cases, business. However, Tembo (n.d.) predicts that the pandemic will derail the progress made during the Vienina Programme of Action for LLDCs' Mid-Term Review for the decade 2014-2024. Furthermore, Osakwe (2021) claims that the COVID-19 problem has had a particularly devastating impact on the mining and tourist industries, with major declines in foreign exchange profits leading to a steep devaluation of the local currency (Kwacha). These innovations have had tangible economic effects. According to the World Bank (2020), Zambia’s poverty rate soared from 58.6% in 2019 to 60.5% in 2020, implying that 706 900 more individuals fell into poverty in 2020. 2.0.4 How the world is fighting against COVID-19 Gavi (2020) summarises the global fight against COVID-19 in 7 distinct ways outlined below; however, at the time of their article, COVID-19vaccines must have not yet been developed or approved as they do not include them. In view of this, COVID-19 vaccines are presented separately in section 1.6. 10 2.0.4.1 Maintaining physical Distance. Physical separation has been one of the most common techniques adopted across the world, from recommending people to keep a distance of 1-2 meters from strangers and cancelling major gatherings, to closing bars, shops, etc, and requesting people to remain at home. Mounting evidence exists that such policies are effective and have led to the preventing of countless deaths. However, they must be used in combination alongside other sanitation and hygiene procedures including disinfection and handwashing. Others, on the other hand, say that lockdowns are only a technique of buying time until additional measures can be scaled up (Gavi, 2020). 2.0.4.2. Contact Tracing Contact tracing is a method of tracking down COVID-19 instances in communities by tracking down persons who had contact with a person sick with COVID-19 (Gavi, 2020). It's a strategy that has been employed in epidemic response for many years: it enabled the eradication smallpox in the 1970s, and it was recently utilized in the Congo DR in reaction to the Ebola virus, when located contacts were vaccinated with the latest Ebola vaccine (Gavi, 2020). Many of the nations that have fared well against COVID-19 have engaged in contact tracing from the beginning, with the goal of controlling the spread. Smartphone applications are being used in certain countries to inform people who most likely had been exposed to COVID-19 (Gavi, 2020). 2.0.4.3 Getting Tested A comprehensive testing capability is required for an approach like contact tracing. Even persons who were not exhibiting symptoms were subjected to open public testing in South Korea as early as February. Germany quickly followed suit, with laboratories in the country having the ability to do 160,000 tests every week as early as March 20. These nations acquired a precise picture of the level of viral transmission in their populations thanks to broad testing, as well as more accurately identify people who could have been exposed and make sure that they were isolated (Gavi, 2020). 2.0.4.4 Surge Capacity in Hospitals Many of the nations that enacted tight lockdown measures, like as the United Kingdom, did so because they were concerned of the possibility that their healthcare system would never be able to handle the fast increasing number of cases. Many nations, on the other hand, as a result of 11 the SARS pandemic which happened in 2003, had already incorporated surge capacity in their healthcare systems Following the SARS outbreak, Singapore increased isolation capability in all healthcare facilities and even constructed an isolation facility with a bed capacity of 330 persons, which served as a buffer after COVID-19 struck (Gavi, 2020). 2.0.4.5 Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Supply The World Health Organization (WHO) issued a warning in March that scarcity of PPE, such as gowns, masks, and gloves, constituted a serious threat to the Health workers’ safety worldwide. They anticipated that equipment manufacture would need to grow by 40%. (Gavi, 2020). While governments focused on expanding the capacity of healthcare by adding more ventilators and beds, few nations paid adequate focus on safeguarding the staff who are the health system's most precious primary resource. Singapore, and other countries who maintained stocks of PPE in their outbreak readiness infrastructure, were able to avert the virus from spreading through healthcare (Gavi, 2020). 2.0.4.6 Clear Communication Countries like New Zealand have been singled out for clearly communicating the hazards presented by COVID-19 and the reasons for the response to the public. Jacinda Ardern, the Prime Minister of New Zealand, was lauded for her concise but courteous comments on reaction measures, urging the public to "unite against COVID-19." It's a different from the pictures of conflict and anti-virus ads that some countries have used (Gavi, 2020). While war analogies may appear appealing, they have been widely criticized for instilling fear and fostering an inward-looking response to the infection. Simple protective tactics such as hand cleanliness and mask use might potentially have a significant influence on transmission, especially in settings where physical separation is difficult (Gavi, 2020). 2.0.4.7 Quick and Decisive Action "The worst blunder is not to move," Dr Michael Ryan remarked during a WHO COVID-19 briefing on emergency response. Countries that quickly deployed control mechanisms, such as lockdown or swiftly improving their capacity to contact trace and test, appeared to be doing the best (Gavi, 2020). Other nations throughout the world, such as Japan, Switzerland, New Zealand, and Germany stood out for their clear plan and clear messaging from the outset due to strong political leadership (Gavi, 2020). 12 On a local scale (in Zambia), According to Osakwe (2021), the government imposed a number of restrictions on March 14, 2020, in order to prevent COVID-19 from spreading and limiting its negative on the Zambian citizens. These measures included the suspension of tourist visas, a ban on non-essential foreign travel, masking up, the suspension of some transportation services across the border, and more. However, even though such measures were needed to contain COVID-19 and avert a public health calamity, they came at a macroeconomic cost in the short and long term, according to Osakwe (2021). 2.0.5 The COVID-19 Vaccines According to WHO (2022), the first major immunization campaign began in early December 2020. If the news of COVID-19's global spread dominated 2020, 2021 was focused on ending the pandemic through vaccine distribution, and as a result, as of January 12th, 2022, the following vaccines had received EUL (The WHO Emergency Use Listing process establishes whether a product can be recommended for use based on all available data on safety and efficacy, as well as its suitability in low- and middle-income countries):The Pfizer/BioNTech Comirnaty vaccine, 31 December 2020. o The SII/COVISHIELD and AstraZeneca/AZD1222 vaccines, 16 February 2021. o The Janssen/Ad26.COV 2.S vaccine developed by Johnson & Johnson, 12 March 2021. o The Moderna COVID-19vaccine (mRNA 1273), 30 April 2021. o The Sinopharm COVID-19vaccine, 7 May 2021. o The Sinovac-CoronaVac vaccine, 1 June 2021. o The Bharat Biotech BBV152 COVAXIN vaccine, 3 November 2021. o The Covovax (NVX-CoV2373) vaccine, 17 December 2021. o The Nuvaxovid (NVX-CoV2373) vaccine, 20 December 2021 Locally, the Viper Group (2022) reported that as of 25th March, 2022, 4 Vaccines were approved for Use in Zambia; which are (1) Pfizer, (2) AstraZeneca, (3) Sinopharm and, (4) Janssen (Johnson & Johnson). In terms of vaccines, WHO (2022) announced that 10,925,055,390 vaccines have been supplied globally as of 17th March, 2022. Dr. Jonas Chanda, the Honourable Minister of Health, formally introduced the COVID-19 immunization on April 14, 2021 in Lusaka, at the University 13 Teaching Hospital (WHO-Africa, 2021). 228,000 doses of COVID-19 vaccines arrived in Zambia as the first shipment from the COVAX facility, a global initiative consisting of the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI), the World Health Organization (WHO), Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), working to ensure equitable distribution of COVID-19 vaccines (WHO-Africa, 2021). According to Zulu, et al. (2022), the Zambian Ministry of Health claimed that 21.6 percent of persons were completely vaccinated as of February 21, 2022. They counter that, while vaccination doses are gradually increasing in the country, with 6.2 million doses arriving as of February 11, fewer than half of those doses have reached people's hands. Only 2.77 million pills have been distributed by February 23. Only 7.2 percent of persons have received a vaccination by December 31, 2021, compared to a target of 40% (Zulu, et., 2022). 2.0.6 “For” or “Against” getting the COVID-19 Vaccine CDC, (2022) outlines some key benefits below, to getting the COVID-19 vaccine: Getting a COVID-19 vaccine narrows the chances of getting the virus COVID-19. Vaccines can also assist in the prevention of major disease and death. All precautions have been taken to guarantee that vaccinations for persons aged 5 and up are effective and safe: Even if a person has already been vaccinated, he or she should have another dose for further protection. Vaccination against COVID-19 is a safer strategy to establish immunity: Getting the COVID-19 vaccine is a better option that guarantees immunity than getting sick with the virus. COVID-19 immunization protects a person by eliciting an antibody response without requiring the individual to get ill. COVID-19 vaccines are suitable for Children and Adults: While COVID-19 vaccines were developed quickly, all steps have been taken to ensure their safety and effectiveness. A growing body of evidence shows that the benefits of COVID-19 vaccination outweigh the known and potential risks. COVID-19 vaccinations work well: COVID 19 vaccinations are effective and can reduce your risk of contracting and transmitting the COVID-19 virus. Even if children and adults contract COVID-19, COVID-19 immunizations can help them avoid major disease and death. 14 However, CDC (2022) describe the implications for not getting the COVID-19 as: COVID-19 infection can have catastrophic consequences: COVID-19 infection can cause serious sickness or death, especially in youngsters, and it is impossible to determine who will have moderate or severe symptoms. COVID-19 infection can lead to issues with long-term health. Even people who exhibit no symptoms when first infected may acquire these long-term health problems. Persons infected with COVID-19 may spread it to others, such as friends and members of the family not eligible for vaccination and those who are at a higher risk of getting COVID-19. Despite the above mentioned benefits of getting the COVID-19 Vaccine, Leggett, (2022) provides 7 reasons as to why people shun the COVID-19 vaccines; (1) "Its not been there long enough; (2) People contract COVID-19 after receiving the vaccination." (3) If the vaccination is so effective, why is it that we require a booster? (4) I've previously had COVID-19, therefore I'm protected; (5) I'm concerned about vaccination adverse effects; (6) The great majority of those who had COVID-19 have survived. I'm ready to accept the risk (7) It's all up to me. If I become sick, I'm only harming myself." (Legget, 2022). Dunning (2021) further adds to Leggetts (2022), that others aren't as enthusiastic. Some people are afraid of vaccinations because they believe they were rushed or ‘,test-runs’, and they may have heard bogus claims that immunizations cause infertility or include a microchip (Dunning, 2021). To put it all into proper perspective CDC (2021) provides “Myths” that people have concerning the COVID-19 vaccine and “facts” that contradict the myths, summarised in Table 2.1 1 MYTHS COVID-19 vaccinations contain hazardous chemicals. FACTS Almost all of the constituents of COVID-19 vaccines – fats, sugars, and salts – are also found in numerous meals. 15 2 3 4 5 The immunity I obtain from becoming infected with COVID-19 is greater than the immunity I get through immunization against COVID-19. Variants are caused by COVID-19 vaccinations. Vaccination is the cause of all occurrences documented to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). The mRNA vaccine isn't actually a vaccination. 6 Microchips are included in COVID-19 vaccinations. 7 COVID-19 vaccination can make you magnetic. COVID-19 vaccinations have the potential to modify my DNA. 9 COVID-19 vaccines have the potential to make me ill. 10 My fertility will be affected by the COVID19 vaccination. 8 COVID-19 vaccines are safer and more trustworthy option to establish COVID19 immunity than being infected with COVID-19. COVID-19 vaccines don’t induce variations of the COVID-19 virus. COVID-19 vaccinations, on the other hand, can assist in preventing the development of new variants. Even if it is unclear if a vaccination caused the condition, anybody can report it to VAERS. As a result, VAERS data alone cannot indicate whether a COVID-19 vaccine caused the reported adverse event. Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna mRNA vaccines function differently than other forms of vaccinations, but they nonetheless cause an immunological reaction in your body. Microchips are not present in COVID19 vaccinations. Vaccines are designed to protect you from disease and are not given to track your movements. COVID-19 immunization does not turn you magnetic, as well as at the injection site, which is generally your arm. COVID-19 vaccinations have no effect on or interaction with your DNA. With COVID-19, the vaccination cannot make you sick. There is currently no proof that any vaccination, including the COVID-19 vaccine, causes reproductive difficulties in either women or men. Table 2.0.1 COVID-19 Myths vs COVID-19 Facts (Adapted from CDC https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/facts.html,) 2.1 Theoretical Framework 16 The theoretical framework for studying the uptake of COVID-19 vaccines among healthcare workers can be informed by the Health Belief Model (HBM) (Rosenstock, 1974). The HBM posits that an individual's beliefs about health and disease, as well as their perception of the benefits and barriers to a particular health behaviour, influence their decision to engage in that behaviour. In the context of COVID-19 vaccination, healthcare workers' beliefs and perceptions can be shaped by several factors, including their level of knowledge about the vaccine, their trust in the safety and efficacy of the vaccine, their attitudes towards vaccination, and their social and cultural background (Bish et al., 2011). The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991) can also provide insight into the factors that influence healthcare workers' decision to get vaccinated. TPB posits that an individual's attitude towards a behaviour, their perceived subjective norms (i.e., the perceived social pressure to perform the behaviour), and their perceived behavioural control (i.e., the perceived ability to perform the behaviour) influence their intention to engage in that behaviour. In the context of COVID-19 vaccination, healthcare workers' intention to get vaccinated can be influenced by their personal beliefs and attitudes towards vaccination, as well as the norms and expectations of their colleagues and the wider healthcare community (Kaptein et al., 2021). Finally, the Social Ecological Model (SEM) (Sallis et al., 2008) can help to understand the broader social and environmental factors that influence healthcare workers' decision to get vaccinated. SEM posits that an individual's behaviour is influenced by factors at multiple levels, including individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and policy levels. In the context of COVID-19 vaccination, healthcare workers' decision to get vaccinated can be influenced by factors such as the availability and accessibility of the vaccine, the support and encouragement of their colleagues and supervisors, and the policies and regulations surrounding vaccination in their workplace and community. Overall, the Health Belief Model, Theory of Planned Behaviour, and Social Ecological Model provide a comprehensive framework for understanding the factors that influence healthcare workers' decision to get vaccinated against COVID-19. By considering the individual, interpersonal, and broader social and environmental factors that shape vaccine uptake, healthcare organizations and policymakers can develop more effective strategies for promoting COVID-19 vaccination among healthcare workers. 17 2.2 Conceptual framework Figure 2.2.1 shows the conceptual framework that relates to the study at hand. Figure 2.2.1 Conceptual Framework (Source: Akther and Nur, 2022) 2.2.1 Belief in conspiracy theories and COVID-19 vaccination A conspiracy belief is the unwarranted assumption of a conspiracy when other explanations are more likely (Brotherton, et al., 2013). There is increasing evidence that BC can have detrimental effects on attitudes and conduct. (Jolley, et al. 2020). Conspiracy theories have long focused on the safety and effectiveness of vaccines, despite the fact that they are the most effective means of preventing infectious illnesses. The main claim in these theories is that major pharmaceutical firms and/or governments hide vaccine information in order to benefit themselves. (Kata, 2009; Jolley and Douglas, 2017). Conspiracy beliefs against vaccinations decrease vaccination plans. (Hornsey et al., 2018). Rumours about delays in the COVID-19 vaccine's creation or that the only people who will receive free vaccines are those who back the current administration could breed mistrust between government stakeholders and the general public. Any regulation relating to vaccinations may be impacted by this. Online rumours and conspiracy theories that are not always supported by empirical proof are 18 frequently increased by health-related information. (Lavorgna, et al., 2018). Online platform users who look for health information run the risk of being exposed to false information that could jeopardise public health. (Waszak, et al., 2018). People who were exposed to information about the COVID-19 vaccine on social media were more likely to be misled and vaccinehesitant, according to Stecula et al. (2020). 2.2.1.1 Impact of conspiracy beliefs on subjective norms As a result of how strongly people are influenced by what they perceive to be societal standards, conspiracy theories are common and can have detrimental effects. (Cookson, et al, 2021). Social influence is the process by which views and actions are influenced by perceptions of what other people believe and do. (Cialdini and Trost, 1998). Social standards serve as a behavioural guide by delineating tacitly what is and is not appropriate in a particular situation (Cialdini and Trost, 1998). Social standards are jointly agreed-upon guidelines for social behaviour, according to Sherif (1936). Stronger group identification increases the likelihood that a person will behave in line with group standards. (Terry and Hogg, 1996). Thus, perceived standards of conspiracy belief may affect personal BC, particularly if individuals believe that organisations with which they firmly associate support conspiracies. (Terry and Hogg, 1996; Jolley, et ., 2019). It is believed that BC, in specific anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs, is more prevalent than it actually is. (Cookson et al., 2021). This is important because, given the detrimental social and health effects of harbouring conspiracy beliefs, especially anti-vaccine conspiracy theories, the overestimation of in-group conspiracy beliefs may result in unjustified social pressure to also support conspiracy beliefs. (Jolley and Douglas, 2019). 2.2.1.2 Impact of conspiracy beliefs on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance Conspiracy ideas and rumours may increase people's anxiety about vaccines. (Islam et al., 2021). Uptake of vaccines has traditionally been affected by unfavourable claims about vaccine effectiveness. There have long been claims that vaccination drives are being used for political gain, and these stories have had an impact on vaccination drives in some nations. (Bhattacharjee and Dotto, 2020). There is a persistent myth that key stages of clinical trials for vaccine development were skipped because drug firms refused to pay volunteers for unfavourable side effects they encountered. Rumours about the COVID-19 vaccine being a messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine that could alter people's Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA), turning them into genetically edited humans, or induce cancers and infertility are the most 19 pervasive. According to some assertions, the COVID-19 vaccine was designed to decrease the world's population. There was a report in Bangladesh that China intended to use Bangladeshi residents as test subjects for a vaccine study. (Islam et al., 2021). 2.2.2. Awareness The degree to which a target populace is informed about an innovation and has developed a general understanding of what it involves is known as awareness. (Dinev and Hu, 2007). The innovation diffusion theory, which claims that awareness, attitude development, choice, execution, and confirmation are all parts of the decision-making process for embracing new technologies, is where the idea of awareness first surfaced. (Rodgers, 1995). It is additionally described as a person's active involvement and elevated curiosity in key problems. (Bickford, 2002; Greene and Kamimura, 2003). People are either unaware of or afraid of the present vaccination program, according to one survey. (Suresh, et al., 2021). In many nations, vaccine reluctance and false information are significant barriers to coverage and population immunisation. (Lane et al., 2017; Larson et al., 2014). Awareness can have positive impact on the vaccine acceptance. In addition to one's mindset towards behaviour, one's social group's behavioural standards have a significant impact on one's desire to behave in a particular way. (Ajzen, 1998). The development of a social network of organisations that vehemently support policies and programmes to lessen such issues is guided by the process of raising problem consciousness. (Biglan and Taylor, 2000). Raising community standards about COVID-19 through the COVID-19 vaccine and increasing knowledge among different socioeconomic groups and communities affects immunisation through the COVID-19 vaccine. 2.2.3. Perceived Usefulness (PU). PU is a measure of how much people believe using a system would enhance their ability to accomplish their jobs. (Davis, 1989). The degree to which a person contemplates using something that offers more advantages is what matters. (Davis, 1989). Attitude can be predicted by PU. (Davis, 1989). Users can adopt an optimistic outlook because there are many advantages to a specific action. According to Islam et al (2021), the majority of subjects had a favourable opinion of vaccination due to its value in preventing the COVID-19 illness. Acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine can be predicted by perceived advantages, such as the vaccine's high efficacy in avoiding serious illness and its consequences, as well as the risk of contracting the illness or spreading it to others. A vaccination certificate may be necessary for recent grads to 20 apply for new jobs, higher education, and to continue their present studies and daily activities. A positive mindset towards accepting vaccines and the COVID-19 vaccine is fostered by the vaccine's utility. Therefore, we hypothesise that 2.2.4 Perceived ease of use (PE). PE is a person's anticipation of how simple the intended method will be to comprehend, acquire, and employ. (Chun and Lu, 2004). The acceptance of an invention will be hampered by the system's complexity. (Rodgers, 1995). The operation of a system can be made simpler so that a user can adopt a good mindset towards purpose and conduct. PE and mindset and understanding go hand in hand. (Davis, 1989; Taylor and Todd, 1995; Ramayah et al., 2004). Convenience in vaccination refers to how simple it is to get the vaccine, taking into account elements like accessibility, cost, and actual availability. (MacDonald, 2015). It is crucial to take vaccine accessibility and cost into account when examining vaccine approval. The adoption of the COVID-19 vaccine will rise if it is more easily and widely accessible. 2.2.5 Subjective Norms A person's view of the societal pressure to engage in or abstain from a goal action is known as a subjective standard. (MacDonald, 2015). While desire to obey reflects how much a person wants to abide by the intentions of the referent other, normative views reflect how a person perceives the impact of opinion among reference groups. (Shmueli, 2021). As a result, people frequently behave in accordance with how they believe others should behave, and those near to them may have an impact on their desire to behave in a particular way. Self-efficacy and subjective standards are important indicators of COVID-19 vaccination intention. (Shmueli, 2021). Subjective standards include how peers and family members reacted to the vaccination, which may be especially important to healthcare professionals. People who have a positive attitude towards the COVID-19 immunisation would advocate for it among their friends, family, and neighbours. 21 CHAPTER THREE Methodology 3.1 Study Approach This was a qualitative study design which is an investigation process of understanding that investigates a social or human problem and is based on distinct methods of inquiry; the researcher establishes a complex, holistic picture, analyses words, reports detailed views of informants, and carries out the study in a natural setting (Creswell, 2009). 3.2 Study design The researcher used a case study design to investigate the uniqueness and complexity of a case while also learning about its activities and conditions (Stake, 1995). The main aspects of case studies are summarized by Yin (2017). To begin with, case studies investigate "a contemporary phenomenon in depth and within its real-life context, especially when the distinctions between phenomenon and context are blurred" (Yin, 2017). The case should be portrayed as a bounded system with clearly defined and delimited limits, despite the fact that the phenomenon and its setting are intertwined (Merriam and Tisdell, 2015). Second, case studies draw on a variety of sources and types of data to meet the full scope of a study issue (Yin, 2017). A case study is ideal for addressing "why," "how," and "what" issues, according to Yin (2014). (among question series: "who," "what," "where," "how," and "why"). For a variety of research topics and challenges, a case study appears to be a viable technique. Because the bounded system is the most significant condition, every research situation where the bounded system is key is a case study candidate. A case study, for instance, in the study of a single organization, community, or program, might be a separate research subject. Case studies are commonly used in evaluations, such as external reviews. This technique gives respondents the freedom to express themselves and use whichever language they like. 3.3 Study population/Target population A population may be described as a collection of people, things, or things from whom samples are obtained for measurement (Kombo and Tromp, 2005). The study population was Health Care Workers of Petauke District Hospital. This study was conducted at Petauke District Hospital. Petauke District Hospital is a 121-bed capacity government health facility located along the on boma road off Great East Road on the way to Chipata, the Provincial headquarters for Eastern Province. It is 420km from the country’s capital city - Lusaka and 190 kilometres from Chipata. Petauke District Hospital is a first referral health facility serving largely the 22 district population of 256,533 for 2020. The site was selected because of its size as a district hospital and also because it has high levels of exposure due to the high patient flow. 3.4 Sample size, sampling procedures Purposive sampling is a non-probability sampling approach in which the items chosen for the sample are chosen based on the researcher's judgment. Researchers typically believe that by using sound judgment, they would be able to get a representative sample while keeping costs down (Kombo and Tromp, 2005). To create the sample, people who do not fulfil a specified profile are excluded, in this case, those that work in departments where there is least exposure to patients, non-consenting HCW’s and support staff or non-clinical staff will also be excluded. A sample is a portion of the population studied in order to derive conclusions about the entire population. For example, according to Kothari (2004), as long as the sample is wellrepresented, the sample's results may be used to make generalizations about the entire population. Sandelowski, (1995) asserts that in general, qualitative research sample sizes really shouldn't be so small that saturation is impossible to attain. In addition the sample size must not be too huge that thorough, case-oriented analysis becomes problematic (Sandelowski,1995). When homogenous samples are chosen in qualitative research, Kuzel (1992) indicates that 6-8 data sources or sampling units are sometimes adequate, and that 12-20 data sources are generally required. According to Morse (1994), qualitative researchers should utilize at least six individuals in investigations aimed at understanding the core of experience. For ethnographies and grounded theory research, Morse (1994) advises 30-50 interviews and/or observations. With the preceding in mind, the sample consisted of 6 HCWs from the ART Department, 20 HCWs from Out Patient Department, 2 lab personnel and 2 HCWs from Dental Department, the total sample size coming to 30 respondents. The respective departments have been selected because they have high risk of exposure to COVID-19 due to having consistent contact with patients or Recipients of Care. 23 3.5 Data collection methods The systematic process of obtaining and analyzing measuring information on selected variables in relation to the research questions, test hypotheses, and assess results is known as data collection (Syed, 2016). Information will be gathered through semi-structured interviews. Many researchers favour interviews that are semi-structured since questions may be prepared in advance, which portrays the interviewer as being well-prepared and capable during the interview. During interviews that are semi-structured, informants are also given the opportunity to express themselves in their very own terms. Semi-structured interviews can yield qualitative data that is both trustworthy and comparable (Syed, 2016). Between the interviewer and the responders, a formal interview is held. The interviewer prepares an interview guide and uses it. This is a list of topics and questions that must be presented in a certain order during the presentation. When the interviewee agrees, the interviewer might deviate from the guide and explore topic trajectories in the talk that aren't necessarily related to the advice (Syed, 2016). Due to the COVID-19 situation, the researcher used google forms to administer the interview via phone calls. This will be less expensive and faster to perform than face-to-face interviews and involves fewer resources. When you just have one chance to interview someone, semistructured interviewing is the ideal option (Bernard, 1988). 3.6 Data analysis The data was examined using thematic analysis. The most fundamental approach for assessing qualitative data is thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Analysis of themes, is a method for discovering patterns and themes of meaning within a dataset with respect to a study topic (Braun and Clarke, 2013). NVivo will be used to import the material from each interview. The theme analysis will be conducted using NVivo, a computer assisted qualitative analysis software (CAQDAS) tool. The steps that the researcher followed in thematic analysis, according to Braun and Clarke (2013), are familiarizing the data, generating initial codes, defining and naming interpretive codes for the entire data set into themes, identifying patterns across all data to derive themes for the data set, defining and naming themes, and concluding analysis. 3.7 Ethical considerations With the present study, there are certain ethical considerations. All participants are requested to give their written consent to participate in the research by signing a Consent form and reading the information page. The purpose is to reassure interviewees that they can opt out of the 24 research at any moment and for any reason. Furthermore, interviewees will be informed about the study's objectives, and they will be assured that their replies will be kept private and used only for academic reasons and the specific research. Interviewees will not be assaulted or abused in any manner during the study, both physically and psychologically. In addition prior to conducting the research, permission will be sought from the University of Lusaka Research Committee (UNILUSREC) and National Health Research Authority (NHRA). 25 CHAPTER FOUR 4.0 Results This chapter presents the results of the study as is obtaining on the ground. 4.1 Socio-demographic details of the participants The participants comprised of 30 Health Care Workers (HCW) from 4 departments, that is; 6 from the ART Department, 2 from Laboratory, 2 from the Dental Department and 20 from Out Patient Department (OPD). The lowest age was 19 years, highest age was 41, mean age was 26 and median age was 25. Of the 30 participants, only 2 were not vaccinated against COVID19 at the time of the interviews. N=30 Lowest Age: 19 Highest Age: 41 Mean Age: 26 Median Age: 25 Vaccinated against COVID-19 Sex Male Female Total Yes No Total Job Title Nurse Clinical Officer Medical Doctor Dental Therapist 10 0 0 0 14 3 1 2 24 3 1 2 22 3 1 2 2 0 0 0 24 3 1 2 ART Department Dental Department Laboratory Out Patient Department (OPD) 0 0 0 10 6 2 2 10 6 2 2 20 6 2 2 18 0 0 0 2 6 2 2 20 Department Table 4.1 Socio-demographic details of the participants 4.2 What are the experiences of Health Care Workers that have been vaccinated and those that have not been vaccinated on the uptake of COVID-19 Vaccines at Petauke District Hospital? In order to capture the HCW experiences on the uptake were asked some questions (as they appear hereon after). The responses were imported into NVIVO qualitative analysis software version 10. Thematic analysis was then done, after coding, in which the emerging themes were best summarised using word clouds. A Word Cloud is a collection or cluster of words depicted in different sizes. The bigger and bolder the word appears, the more often it is selected/voted 26 for by an audience member. Word Clouds are a powerful way to visualise what your audience really thinks about a topic. Word clouds are a great way to visualize qualitative data you have — interviews, quotes, etc (McNaught and Lan, 2010). 4.2.1. Tell me about your concerns about acquiring COVID-19. Figure 4.1 Word Cloud: HCW’s concerns about getting COVID-19 (Source: NVIVO version 10) When asked about their concerns on getting COVID-19, most of them expressed concerns, as seen in the word cloud (figure 4.1), furthermore, most expressed having negative feelings, such as fear, anxiety. Fear was the major feeling expressed; that is fear of getting the virus since they work in close contact with patients who may be infected, fear of dying from the virus, fear of it being severe and fear of passing it on to relatives, friends and patients. However, on a positive note, some participants advocated for all people to get vaccinated which would help lessen the spread of the virus. 27 HCW24 (Nurse): “I have concerns, what if I die, or what if it will be very severe.” HCW16 (Clinical Officer_Vaccinated): “My concern is my life can be at risk I might lose my life and also affect people around me.” HCW 20 (Medical Doctor_Vaccinated): “That I might get it since I work in a high risk area and am exposed to the virus daily.” HCW 22 (Nurse_Vaccinated): “I am not fearful of getting the virus because I have been vaccinated and medications exist for treatment.” HCW 26 (Nurse_Not vaccinated): “I have mixed feelings, such as fear or anxiety because I don't know much about how the virus reacts in the body.” 4.2.2 What are your thoughts on the COVID-19 vaccine?— Have you heard something which makes you nervous?— Where did you get this information? When asked about their thoughts of the COVID-19 Vaccines and whether they had heard anything about it which made them nervous, and the source of such information; the participants expressed different experiences, as shown in figure 4.2. The emerging themes were that of negative information being heard in various sources, such as the community, social media such as on Facebook, bloggers, etc. This negative information was mostly in form of myths, which led to some HCW being nervous about getting the vaccine. HCW 14 (Nurse_Vaccinated): “I was nervous before I got my first dose of these vaccines, but after experiencing it now I don't have any thoughts.” HCW 27 (Nurse_Not vaccinated): “I think the vaccines are not good, because we have different bodies, others react while others don't react. From social media (Facebook and opera mini and from church) that we should not get vaccinated because the vaccines are not good for the body.” 28 Figure 4.2 Word Cloud: HCWs’ thoughts about the COVID-19 Vaccines (Source: NVIVO version 10) 4.2.3 What are your opinions on the vaccine's safety and newness of the vaccines? When asked about the safety of the vaccines the emerging theme as seen in figure 4.3, was that the vaccines are safe as they are a good option from preventing COVID-19, reducing the severity of the cases when infected and reducing the number of new cases. HCW 30 (Nurse_Vaccinated): “Yes they are safe even though there has been many myths surrounding that.” HCW 13 (Nurse_Vaccinated): “I think they should continue being given [the vaccines] because just after the coming of vaccines the number of cases reduced together with the deaths.” 29 Figure 4.3 Word Cloud: HCWs’ opinions on the safety of the COVID-19 Vaccines (Source: NVIVO version 10) 4.2.4 How much do you trust the health care person who will administer the vaccine? Lastly on experiences, the HCW were asked, before being vaccinated whether they trusted the HCW giving the COVID-19 vaccine. The emerging theme as seen in figure 4.4 was that of trust, although, others had some doubts and for some the trust levels were not 100%. However, the HCW not vaccinated expressed complete mistrust of the HCW who would administer the vaccine. HCW 30 (Nurse_Vaccinated): “I trusted the person 100% percent because of the way I was welcomed and how the health care worker explained.” HCW 29 (Nurse_Vaccinated): “I trusted the health care worker 75% because I was not given ICE on the benefits and side effects so I had some fear.” HCW 27 (Nurse_Not vaccinated): “I don't trust them, because I feel they add something to the vaccine.” 30 Figure 4.4 Word Cloud: HCWs’ trust of the HCW giving the COVID-19 Vaccines (Source: NVIVO version 10) 4.3 What are the reasons why some healthcare workers have not been vaccinated yet at Petauke District Hospital. In order to drill down to the reasons why the HCWs are not vaccinated, their responses on some key questions were extracted, since those not vaccinated were only 2 HCW out of the total of 30 HCW. 4.3.1 What are your thoughts on the COVID-19 vaccine?— Have you heard something which makes you nervous?— Where did you get this information? HCW 26 (Nurse_Not Vaccinated): “I have mixed feelings because of what people say, that the virus is being introduced in your body that will kill me slowly—from people or friends.” HCW 27 (Nurse_Not Vaccinated): “I think the vaccines are not good, because we have different bodies, others react while others don't react.—From social media 31 (Facebook and opera mini and from church) that we should not get vaccinated because the vaccines are not good for the body.” 4.3.2 What are your opinions on the vaccine's safety and newness of the vaccines? HCW 26 (Nurse_Not Vaccinated): “I don't know.” HCW 27: “Yes they are safe but I still have some doubts.” 4.3.3 Have you considered being vaccinated against COVID-19? What decision did you make? (Skip if already vaccinated). HCW 26 (Nurse_Not Vaccinated): “Yes, I have considered it, but I don't know where to get it.” HCW 27 (Nurse_Not Vaccinated): “No I have not thought about getting vaccinated. I have decided not to get vaccinated.” 4.3.4 How much do you trust the health care person who will administer the vaccine? HCW 26 (Nurse_Not Vaccinated): “I trust the health care worker 50%, because most of the health workers don't follow the rules of masking up, so they can transmit the virus to me.” HCW 27 (Nurse_Not Vaccinated): “I don't trust them, because I feel they add something to the vaccine.” Emerging themes from the responses as reasons for not being vaccinated are; fear/mixed feelings/doubts/mistrust induced by wrong information from friends, the community, church and social media platforms such as Facebook and Opera Mini News feeds. In addition, HCW appear to have insufficient knowledge on the benefits on how the vaccines work and how they are designed to work in any person. Lack of trust of fellow HCW administering the vaccine is also presented as a reason for not getting vaccinated. 4.4 What are some of the experiences from the Health Care Workers that can promote the increase in the uptake of COVID-19 vaccines at Petauke District Hospital. Figure 4.4, summarises, the experiences of the HCWs on the uptake on COVID-19 vaccines. The most emerging positive theme was that all but 2 HCWs were vaccinated, and gave positive feedback on their experiences. 32 Figure 4.4 Word Cloud: HCWs’ Experiences COVID-19 Vaccines Uptake (Source: NVIVO version 10) 4.4.1 What would make getting a COVID-19 vaccination easier for you if it was recommended and available? HCW 26 (Nurse_Not vaccinated): “If I am told where the vaccine is given from and being given more information on the vaccine.” HCW 27 (Nurse_Not vaccinated): “I need proper information on the vaccines for example from the World Health Organisation.” As for the HCW who were not vaccinated, when asked about their final decision whether they will get the vaccine or not (enablers); a need for more information to be given to them on the vaccines was expressed. 33 CHAPTER FIVE 5.0 Discussion HCWs are an essential component of every health system in the world (WHO, 2016). The COVID-19 pandemic's disastrous impact on healthcare delivery has brought attention back to the crucial role that HCWs play in all health systems (WHO, 2020). In the fight against the pandemic, HCW safety is of utmost importance. The results showed that amongst the experiences of the HCWs, when asked about concerns on getting the COVID-19 virus, the emerging themes where those of HCWs having negative feelings such as fear, nervousness and anxiety at the thought of getting the virus, passing it on to their friends and relatives, of getting severe forms of the virus or of dying from the virus. These findings resonate with the various reports on COVID-19 infections and mortality among frontline healthcare workers (HCW) (Erden and Lucey, 2021). For instance, the WHO African Regional Office estimated that in 2020, the virus infected about 10,000 healthcare workers in Africa (AFRO/WHO, 2020). Similar to this, the WHO Pan American Regional Office (PAHO) estimated that as of September 2020, 2500 HCWs had died from COVID-19 and 570 000 had been infected (PAHO/WHO, 2020). Such reports of death from the virus can indeed cause such negative feelings to linger among the HCWs. When asked about their thoughts of the COVID-19 Vaccines and whether they had heard anything about it which made them nervous, and the source of such information; The emerging themes were that of negative information being heard in various sources, such as the community, social media such as on Facebook, bloggers, etc. This negative information was mostly in form of myths. These findings tally with those of Kitonsa et al., (2021) and Valliers et al., 2021, in their studies in which many of their participants also claimed to have heard negative things about the COVID-19 vaccine from various sources. Negative information concerning the COVID-19 vaccine was particularly prevalent through social interactions and social media. It is noteworthy that more than three-quarters of respondents said they had received unfavourable information via chatting apps. The placement of factual vaccine information can be directed by this knowledge of the precise social media platforms spreading harmful information. Given the link between exposure to unfavourable information and vaccination motivation, this is particularly significant. It relates to whether the responder would advocate for the vaccination of loved ones (Kitonsa et al., 2021; Valliers et al., 2021). 34 Because of their training in science and medicine, most survey participants agreed that the vaccine was necessary and safe. These findings were consistent with those of Raude et al. (2016), who asserted that HCWs had a positive attitude toward vaccinations, because of their constant contact with patients and the need to safeguard themselves against the risk of infection. Emerging themes from the responses as reasons for not being vaccinated are; fear/mixed feelings/doubts/mistrust induced by wrong information from friends, the community, church and social media platforms such as Facebook and Opera Mini News feeds. In addition, HCWs appear to have insufficient knowledge on the benefits on how the vaccines work and how they are designed to work in any person. Lack of trust of fellow HCW administering the vaccine is also presented as a reason for not getting vaccinated. These findings tally somewhat with the findings of Murphey et al., (2021) who stated that indecisive people are a group that can change their minds if they obtain more information about the effectiveness of the vaccine, its safety, and the fact that, if vaccinated, it protects both themselves and those who may have wanted but could not be vaccinated against disease (Murphey et al., 2021). In terms of overall experiences of HCWs on the uptake of the COVID-19 Vaccines, this study discovered a very high acceptance and vaccination rate of 93% (that is 28 HCWs vaccinated and only 2 not vaccinated), which is in contrast to the low acceptance seen in studies conducted among HWs in Nigeria, Ghana, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Saudi Arabia before the vaccine was available (Agyekum et al. 2021; Ekwebene at al, 2021; Qattan et al., 2020; Nri-Ezedian et al., 2021; Nzaji et al., 2020). This strong acceptability can be linked to the vaccine's accessibility in the country and the initial phase's emphasis on immunizing HCWs (Odekunle and Odekunle, 2021). Prior to the vaccine's introduction in Zambia, successful vaccination deployments in highly developed countries may have also contributed to this high acceptability. According to a study by Viswanath et al. (2021), those who believed that they were more likely to contract COVID19 and that the consequences would probably be severe were more likely to accept the vaccinations that were offered to them and the others in their care. According to the health belief model, people's preparedness to take action was influenced by their views of the advantages of attempting to prevent sickness as well as their beliefs about their susceptibility to it. It's possible that being on the front lines of the COVID-19 battle and witnessing firsthand the catastrophic effects of the virus enhanced people's desire to receive vaccinations. (Viswanath et al, 2021). 35 5.1 Limitations This study has some limitations. First, the sample size is relatively small only 30 HCWs. Second, the study was a qualitative case study and therefore causality cannot be established. Third, this study used convenience-sampling technique, which is a non-probability sampling technique, thus limiting the extent to which the results can be generalized to the population of health care workers in Zambia. Fourth, it was conducted in a single Health center, however, this hospital is a university facility that is composed of all key departments. A large number of substantial number of HCWs work there and numerous residents gravitate for treatment to it. Future research should be quantitative in order to establish causal relationship between uptake of vaccines and possible barriers or factors. In addition it should be carried out at more than one health facility in Zambia. 36 CHAPTER SIX 6.0 Conclusion and Recommendations The uptake of the COVID-19 vaccines was determined to be high, 28 (93%) of the Health Care Workers (HCWs) were vaccinated with only 2 not being vaccinated. A comparable study conducted in Uganda (Katonsa et al., 2021) found that more than 70% of people accepted the vaccine. However, this confidence needs to be maintained by ongoing, focused public health education and HCWs sensitization seminars. In order to ensure that COVID-19 vaccine rollout interventions for the global south are implemented successfully and effectively, these countryspecific contexts should serve as a guidance. The results have introduced baseline empirical evidence on the need for additional follow-up mixed methods studies to fully understand experiences and reasons for vaccine acceptance and hesitancy among HCWs, even though the findings reported in this paper are exploratory and may not be entirely conclusive. HCWs are a valuable resource for the general public in terms of health information and validation, and their opinions on the COVID-19 vaccine are essential in swaying public opinion about vaccinations in general. Additionally, continuous engagement with HCWs by health managers and policy experts throughout the value chain on vaccine trials and deployment will promote trust and confidence which will likely trickle down to the general population through advocacy by HCWs on public health benefits of vaccination. Finally, there is the need for effective stakeholder engagements towards championing vaccinations uptake as a public health intervention. Government agencies, Civil Society Organizations (CSOs), health professional groups should lead in mobilizing resources for these campaigns. 6.1 Recommendations The following are some recommendations. 1. Continued communication with HCWs about vaccines and deployment by health managers and policy experts along the entire value chain will foster trust and confidence, which will probably filter down to the general populace through HCW advocacy on the public health benefits of vaccination. 2. There’s a necessity for effective stakeholder engagements to promote vaccine uptake as a public health intervention is the final requirement. Governmental organizations, civil society organizations (CSOs), and associations of health professionals should take the initiative in raising money for these campaigns. 37 3. The use of more validated and verified sources and critical evaluation of health information before making public health decisions should be taught to healthcare professionals in more depth. 4. In order to find and equip local champions for vaccination uptake, the Ministry of Health (MoH) and its implementing agents should work with religious organizations and their leadership. 38 REFERENCES Adhikari, S., Meng, S., Wu, YJ. et al (2020). Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: a scoping review. Infect Dis Poverty 9, 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249020-00646-x (Accessed 15/03/2022). African Regional Office (AFRO)/World Health Organization (WHO/OMS).Over 10,000 Health Workers in Africa Infected with COVID-19. 2020 (cited2020 Jul 23); 2020. https:// www. afro. who. int/ news/ over-10-000-healthwork ers-africa-infec ted-covid-19. Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H, Zhan C, Chen C, Lv W, Tao Q, Sun Z, Xia L. (2020), Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a report of 1014 cases. Radiology. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020200642, (Accessed 15/03/2022). Ajzen I, Fishbein M. (1980), Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviour. Ajzen I. (1998), Models of human social behaviour and their application to health psychology. Psychol Health.1998; 13(4):735–739. Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational behaviour and human decision processes, 50(2), 179-211. Akther T, Nur T (2022) A model of factors influencing COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: A synthesis of the theory of reasoned action, conspiracy theory belief, awareness, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use. PLOS ONE 17(1): e0261869. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261869 Altena, E.; Baglioni, C.; Espie, C.A.; Ellis, J.; Gavriloff, D.; Holzinger, B.; Schlarb, A.; Frase, L.; Jernelöv, S.; Riemann, D. (2020), Dealing with sleep problems during home confinement due to the COVID-19outbreak: Practical recommendations from a task force of the European CBT-I Academy. J. Sleep Res. 2020, 29, e13052. Bernard, H. Russell (Harvey Russell), (1940), -Research methods in cultural anthropology. Bhattacharjee S, Dotto C. (2020), First draft case study: Understanding the impact of polio vaccine disinformation in Pakistan. First Draft. 2020, United States. 39 Bickford D, Reynolds N. Activism and service-learning: Reframing volunteerism as acts of dissent. Pedagogy.2002; 2(2):229–252. Biglan A, Taylor T. (2000), Why have we been more successful in reducing tobacco use than violent crime?. Am J Community Psychol. 2000; 28(3):269–302. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005155903801 PMID:10945118 Bish, A., Yardley, L., Nicoll, A., Michie, S. (2011). Factors associated with uptake of vaccination against pandemic influenza: a systematic review. Vaccine, 29(38), 6472-6484. Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa, (Accessed 17/03/2022). Brotherton R, French C, Pickering A. (2013), Measuring belief in conspiracy theories: The generic conspiracist beliefs scale. Front Psychol. 2013; 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00279 PMID: 23734136 CDC (2020), First 100 Persons with COVID-19 — Zambia, March 18–April 28, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6942a5.htm (Accessed 17/03/2022). CDC, (2021), Getting Vaccines and Getting People Vaccinated, https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/stories/2021/taking-on-covid-19-in-zambia.html (Accessed 17/03/2022). CDC, (2021), Myths and Facts about COVID-19 Vaccines, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/facts.html (Accessed on: 17/03/2022). CDC, (2022), Benefits of Getting a COVID-19 Vaccine, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/vaccinebenefits.html#:~:text=Getting%20vaccinated%20against%20COVID%2D19,ages%205%20y ears%20and%20older. (Accessed on: 17/03/2022). Chan S, Lu M. Understanding internet banking adoption and use behavior. Journal of Global Information Management. 2004; 12(3):21–43. Cheng ZJ, Shan J. (2020), 2019 Novel coronavirus: where we are and what we know. Infection. 2020;48:155–63. Cialdini R, Trost M. (1998), Social influence: Social norms, conformity and compliance. 40 Cookson D, Jolley D, Dempsey R, Povey R. (2021) “If they believe, then so shall I”: Perceived beliefs of the ingroup predict conspiracy theory belief. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2021; 24(5):759–782. Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 3rd ed,, Sage Publishers, .Los Angeles. CRS (2021), Origins of the COVID-19Pandemic, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11822 (Accessed on 15/03/2022) Davis F, Bagozzi R, Warshaw P. (1989), User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Manage Sci. 1989; 35(8):982–1003. Davis F. (1989), Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly. 1989; 13(3):319. Demographic Dividend, (2021), Zambia Trends, https://demographicdividend.org/zambia/, (Accessed 17/03/2022). Dinev T, Hu Q. (2007), The centrality of awareness in the formation of user behavioural intention toward protective information technologies. J Assoc Inf Syst. 2007; 8(7):386–408. Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. (2020) An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20 (5):533–4 Available from: https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd402994234 67b48e9ecf6. pmid:32087114 (Accessed 17/03/2022). Dunning, D., (2021), Why people don't want the COVID-19vaccine: Hesitancy vs. resistance, https://lsa.umich.edu/psych/news-events/all-news/faculty-news/why-people-don-t-want-thecovid-19-vaccine--hesitancy-vs--resist.html (Accessed 17/03/2022). Ekwebene OC, Obidile VC, Azubuike PC, Nnamani CP, Dankano NE, Egbuniwe MC. COVID-19 (2021), vaccine knowledge and acceptability among healthcare providers in Nigeria. Int J Trop Dis Heal.2021:51–60. Erdem H, Lucey DR. (2021), Healthcare worker infections and deaths due to COVID-19: a survey from 37 nations and a call for WHO to post national data on their website. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;102:239. 41 Eri Y, Ramayah T. (2005), Using TAM to explain intention to shop online among university students, IEEE International Conference on Management OF Innovation and Technology. Fwoloshi, S. et al., (2020), Prevalence of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Among Healthcare Workers-Zambia, July 2020, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33784382/, (Accessed 15/03/2022). GAVI, (2020), Seven things countries have done right in the fight against COVID-19, https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/seven-things-countries-have-done-right-fight-againstcovid-19 (Accessed 17/03/2022). Greene S, Kamimura M. Ties that bind: Enhanced social awareness development through interactions with diverse peers. 2003;. In Annual Meeting of the association for the study of higher education (pp.213–228). Holmes, E., Stephen A. Goldstein, Angela L. Rasmussen, David L. Robertson, et al., (2021), The origins of SARS-CoV-2: A critical review, Elsevier Inc, Sydney. Hornsey M, Harris E, Fielding K. (2018), The psychological roots of anti-vaccination attitudes: A 24-nation investigation. Health Psychol. 2018; 37(4):307–315. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000586 PMID:29389158 https://www.novanthealth.org/healthy-headlines/7-reasons-people-dont-get-vaccinatedagainst-covid-19 (Accessed 17/03/2022). Islam M, Kamal A, Kabir A, (2021) ,Southern D, Khan S, Hasan S et al. COVID-19 vaccine rumours and conspiracy theories: The need for cognitive inoculation against misinformation to improve vaccine adherence. PLoS ONE. 2021; 16(5):e0251605. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251605 PMID: 33979412 Islam M, Siddique A, Akter R, Tasnim R, Sujan M. (2021), Knowledge, attitudes and perceptions toward COVID-19 vaccinations: a cross sectional community survey in MedRxiv, Bangladesh. Jolley D, Douglas K, Leite A, Schrader T. Belief in conspiracy theories and intentions to engage in everyday crime. Br J Soc Psychol. 2019; 58(3):534–549. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12311 PMID:30659628 Jolley D, Douglas K. (2013), The social consequences of conspiracism: Exposure to conspiracy theories decreases intentions to engage in politics and to reduce one’s carbon 42 footprint. Br J Psychol. 2013;105(1):35–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12018 PMID: 24387095 PLOS ONE A model of factors influencing the Covid-19 vaccine acceptance Jolley D, Douglas K. (2017), Prevention is better than cure: Addressing anti-vaccine conspiracy theories. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2017; 47(8):459–469. Jolley D, Paterson J. Pylons ablaze: Examining the role of 5G COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and support for violence. Br J Soc Psychol. 2020; 59(3):628–640. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12394 PMID:32564418 Kabamba Nzaji M, Kabamba Ngombe L, Ngoie Mwamba G, et al. (2020), Acceptability of vaccination against COVID-19 among healthcare workers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Pragmatic Obs Res. 2020;11:103–109. Kaptein, F., Staalduinen, A. A. V., Luyten, J. (2021). COVID-19 vaccination intentions of Belgian health care workers: A large cross-sectional survey. Vaccine, 39(7), 1146-1154. Kaseje N. (2020) Why Sub-Saharan Africa needs a unique response to COVID-19. The World Economic Forum; 2020 [cited 2020 Nov 26]. Available from: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/03/why-sub-saharan-africa-needs-a-unique-responseto-covid-19/. (Accessed 17/03/2022). Kashif, M., et al., (2021), Perception, Willingness, Barriers, and Hesitancy Towards COVID19 Vaccine in Pakistan: Comparison Between Healthcare Workers and General Population, Cureus 13(10): e19106. doi:10.7759/cureus.19106. Kata A. (2010), A postmodern Pandora’s box: Anti-vaccination misinformation on the Internet. Vaccine. 2010; 28(7):1709–1716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.12.022 PMID: 20045099 Kitonsa J, Kamacooko O, Bahemuka UM, Kibengo F, Kakande A, Wajja A, Ruzagira E. (2020), Willingness to participate in COVID-19 vaccine trials; a survey among a population of healthcare workers in Uganda. PloS one. 2021;16(5):e0251992. Kombo, K.D. and Tromp, L.A.D. (2006) Proposal and Thesis Writing: An Introduction. Paulines Publishers, Nairobi, Kenya. Kothari, C.R. (2004) Research Methodology: Methods and Techniques. 2nd Edition, New Age International Publishers, New Delhi. 43 Kuzel, A. J. (1992). Sampling in qualitative inquiry. In B.F. Crabtree & W.L. Miller (eds.), Doing qualitative research. Research Methods for Primary Care. Vol.3, 31-44, Sage, Newbury Park, CA. Lane S, MacDonald N, Marti M, Dumolard L. Vaccine hesitancy around the globe: Analysis of three years of WHO/UNICEF Joint Reporting Form data-2015–2017. Vaccine. 2018; 36(26):3861–3867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.03.063 PMID: 29605516 Larson H, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith D, Paterson P. (2014), Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: A systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine. 2014; 32(19):2150–2159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081 PMID:24598724 Lavorgna L, De Stefano M, Sparaco M, Moccia M, Abbadessa G, Montella P et al. (2018), Fake news, influencers and health-related professional participation on the Web: A pilot study on a social-network of people with Multiple Sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018; 25:175–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard. 2018.07.046 PMID: 30096683 Leggett, P., (2022), 7-reasons-people-dont-get-vaccinated-against-covid-19, https://www.novanthealth.org/healthy-headlines/7-reasons-people-dont-get-vaccinatedagainst-covid-19 (Accessed 17/03/2022). MacDonald N. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015; 33(34):4161–4164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036 PMID: 25896383 Martin Wiredu Agyekum, Grace Frempong Afrifa-Anane, Frank Kyei-Arthur, Bright Addo, "Acceptability of COVID-19 Vaccination among Health Care Workers in Ghana", Advances in Public Health, vol. 2021, Article ID 9998176, 8 pages, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9998176 Mathieson K. (1991), Predicting user intentions: comparing the technology acceptance model with the theory of planned behaviour. Information Systems Research. 1991; 2(3):173–191. McNaught, C., & Lam, P. (2010). Using Wordle as a supplementary research tool. Qualitative Report, 15(3), 630-643. Merriam, S. B., Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation (4th ed.), Jossey Bass, San Francisco, CA. 44 Morse, J.M. (1994). Designing funded qualitative research. In N.K. Denzin & Murphy, J.; Vallières, F.; Bentall, R.P.; Shevlin, M.; McBride, O.; Hartman, T.K.; McKay, R.; Bennett, K.; Mason, L.; Gibson-Miller, J.; et al. Psychological characteristics associated with COVID19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Ireland and the United Kingdom. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 29. Nri-Ezedia CA, Okechukwu C, Ogochukwu OC, et al. Predictors of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) vaccine acceptance among Nigerian medical doctors. SSRN Electron J. 2021. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3820535. Odekunle FF, Odekunle RO. The impact of the US president’s emergency plan for AIDS relief (PEPFAR) HIV and AIDS program on the Nigerian health system. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;25:143. Osakwe, N.P. (2021), COVID-19and the Challenge of Developing Productive Capacities in Zambia, UNCTAD, https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ser-rp-2021d6_en.pdf, (Accessed 15/03/2022). Pan F, Ye T, Sun P, Gui S, Liang B, Li L, Zheng D, Wang J, Hesketh RL, Yang L. Time course of lung changes on chest CT during recovery from 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID19) pneumonia. Radiology. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020200370 (Accessed 15/03/2022). PanAmerican Health Organization (PAHO)/World Health Organization (WHO). COVID-19 has Infected Some 570.000 Health Workers and Killed 2,500 in the Americas. 2020 (cited 2020 Sep 27). https:// www. paho. org/en/ news/2-9-2020-covid-19-has-infected-some570000-health-workers and killed-2500-americas-paho. Piaget J. (1975), The equilibrium of cognitive structures. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261869 January 12, 2022 18 / 20 Qattan AMN, Alshareef N, Alsharqi O, Al Rahahleh N, Chirwa GC,Al-Hanawi MK. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among healthcare workers in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Front Med.2021;8:644300. 45 Ramayah T, Nasurdin A, Noor M, Sin Q. (2004), The Relationships between belief, attitude, subjective norm, and behavior toward infant food formula selection: The views of the Malaysian mothers. Gadjah Mada Int J Bus. 2004; 6(3):405. Raude J, Fressard L, Gautier A, Pulcini C, Peretti-Watel P, Verger P. Opening the “Vaccine Hesitancy” black box: how trust in institutions affects French GPs’ vaccination practices. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2016;15(7):937–48. https:// doi. org/ 10. 1080/ 14760 584. 2016. 11840 92. Rogers E. (1995), Diffusion of Innovations: Modifications of a model for telecommunications. Die diffusion von innovationen in der telekommunikation. Springer. 1995:25–38. Rosenstock, I. M. (1974). Historical origins of the health belief model. Health education monographs, 2(4), 328-335. Sallis, J. F., Owen, N., Fisher, E. B. (2008). Ecological models of health behaviour. In Health behaviour and health education: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 465-485). JosseyBass. Sandelowski, M. (1995). Focus on quantitative methods: Sample sizes, in qualitative research. Research in Nursing and Health, 18, 179-183. Schmidt T, Cloete A, Davids A, Makola L, Zondi N, Jantjies M: Myths, misconceptions, othering and stigmatizing responses to Covid-19 in South Africa: a rapid qualitative assessment. PLoS One. 2020, 15:e0244420. 10.1371/journal.pone.0244420 Sebetian, G. et al., (2021), COVID-19 infection among healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study in southwest Iran, Virology Journal volume 18, Article number: 58 Sherif M. (1936), The psychology of social norms. Shmueli L. Predicting intention to receive COVID-19 vaccine among the general population using the health belief model and the theory of planned behavior model. BMC Public Health. 2021; 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10816-7 PMID: 33902501 Simulundu, E., Mupeta, F., Chanda-Kapata et al. (2020), First COVID-19case in Zambia — Comparative phylogenomic analyses of SARS-CoV-2 detected in African countries, Elsevier Ltd, (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). (Accessed 15/03/2022). 46 Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research. SAGE Publications. Stecula D, Kuru O, Hall Jamieson K. How trust in experts and media use affect acceptance of common anti-vaccination claims. Harv Kennedy Sch Misinformation Rev. 2020; 1(1). Suresh A, Konwarh R, Singh A, Tiwari A. (2021), Public awareness and acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine: An online cross-sectional survey, conducted in the first phase of vaccination drive in India. 2021. https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-324238/v1. Syed Muhammad Sajjad Kabir (2016), Methods of Data Collection, Curtin University, Bangladesh. Taylor S, Todd P. (1995), Understanding information technology usage: A test of competing models. Information Systems Research. 1995; 6(2):144–176. Tembo, I, (n.d.), Covid-19 Impacts, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/29296Ms._Irene_Tembo_Webinar _part_2.pdf (Accessed 19/03/2022). Terry D, Hogg M. Group Norms and the Attitude-Behaviour Relationship: A Role for Group Identification. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1996; 22(8):776–793. Viper Group (2022), COVID-19Vaccine Tracker-Zambia, https://covid19.trackvaccines.org/country/zambia/ (Accessed 27/03/2022). Viswanath K, Bekalu M, Dhawan D, Pinnamaneni R, Lang J, McLoud R. Individual and social determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1–10. Waszak P, Kasprzycka-Waszak W, Kubanek A. (2018), The spread of medical fake news in social media—The pilot quantitative study. Health Policy Technol. 2018; 7(2):115–118. WHO (2021), The impact of COVID-19 on health and care workers: a closer look at deaths, WHO, Geneva. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/345300/WHO-HWFWorkingPaper-2021.1-eng.pdf (Accessed 19/03/2022). World Bank (2020). Accelerating Digital Transformation in Zambia: Digital Economy Diagnostic Report, World Bank, Washington, DC. World Health Organization (WHO). Global strategy on human resources for health: workforce 2030. ISBN 978 92 4 151113 1, Geneva; 2016.32. World Health Organization 47 (WO). Pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic: Interim Report, 27th August, 2020. Geneva; 2020. World Health Organization, (2022), WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard, 2021. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (Accessed 19/03/2022). Wu, Z.; McGoogan, J.M. (2019) Characteristics of and important lessons from the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: design and methods. Calif, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks. Zulu, A., Janoch, E., Selva, M,. (2022), Roadblocks at the last mile: What’s slowing down vaccines in Zambiahttps://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/CARE-ZambiaVaccine-Case-Study-Feb-23-2022.pdf (Accessed 19/03/2022). 48 APPENDICES Appendix 1: Data collection tool: Qualitative Interview Guide Interview Guide Adapted for this study using the WHO Structured Interview Guide. Construct General Health worker Please tell me about yourself. Age, sex, other details Tell me about your responsibilities/designation. Feelings and thoughts COVID-19 risk perception – self Tell me about your concerns about acquiring COVID-19. — What makes you feel like that? — Do you believe it's likely? — Do you believe it would be severe? HCW’s Perceived risk to patients What are your thoughts on the possibility of giving COVID-19 to your patients? COVID-19 related stigma (social pressures) What is the typical treatment of a health care professional in the community? - - Has there been any difference in how you've been treated since the COVID19 pandemic? What are your thoughts on the COVID-19 vaccine? — Have you heard something which makes you nervous? — Where did you get this information? — Have you heard something which makes you optimistic about the vaccines under development? What are your thoughts on the COVID-19 vaccine(s)? Vaccine information for COVID-19 Confidence in COVID-19 vaccine Rationale — Warm-up question — Introduces the interviewer to the circumstances of the participant. — Gain a better understanding of the participant's perceived danger from COVID-19 (the disease, not the vaccination) — This will connect in with a subsequent inquiry regarding taking the COVID-19 vaccine. — Determine the HCW's perception of the danger of infecting others. — Allows for probing for the presence/experience of stigma, which is related to the vaccination question below. — Inquires about their knowledge of the vaccination - this allows to probe for good or negative information. — Elicits participant trust in the vaccination; probing questions will cover a variety of topics, including 49 — What are the impressions of each vaccination if numerous vaccines are available? Return to the perceived COVID-19 danger and its importance. — Importance of safeguarding others — Harmony with spiritual or religious convictions (inquire for all COVID-19 vaccines in stock) — What are your opinions on the vaccine's safety? (Ask for all available COVID-19 vaccinations) — Newness of the vaccines — Opinions as to whether it works (inquire for all COVID19 vaccines in stock) Motivators Intention to get the COVID-19 vaccine Have you considered being vaccinated against COVID-19? What decision did you make? (Why?) ….. Continue to the next question (combine) Getting the COVID19 vaccine – decision making process Explain how you plan to or have decided to receive a COVID-19 vaccination. Probe: — Was anybody else engaged in the decision-making process? With whom did you discuss it? — Is that anything your boss/supervisor requires? Getting the COVID19 vaccine – whether it is safe to see friends and family (if you've previously received the vaccination) Has getting vaccinated against COVID-19 altered your life? (If you haven't had the vaccination yet) How do you believe obtaining the COVID-19 vaccine will affect your life? Examine: — Consult with family and friends — Making an appearance in public safety, significance, and so on. — Discovers their objectives and choices regarding the vaccination. The "why" inquiry could be an excellent spot to triangulate their replies because it may be repeated of the questions answered previously. — Addresses decision autonomy as well as the decision-making process in general, with the goal of determining what kind of social processes are involved. — This covers the survey item, but it's been broadened to investigate for other ways a COVID-19 vaccination may affect people. 50 Stigma around the COVID-19 vaccine (If they said yes to the previous question about stigma): Do you believe the COVID-19 vaccination will or has assisted with the stigma we discussed earlier? Why? This is only significant if the participant mentioned any type of stigma in the previous question. If they don't claim having faced or heard of it happening, don't inquire. COVID-19 vaccine — Social norms that are descriptive — Family norms — Religious leader norms — Workplace standards What do you think other people will do if a COVID-19 vaccination is suggested by health care workers? — Relatives and friends — What do religious or community leaders advise? — What do you expect your coworkers to do? — Is this true for all COVID-19 vaccinations or does it depend on which vaccine is advised if more than one vaccine is available? — Finds out what they think the social norms will be for COVID-19 immunization uptake. Have you ever gotten an adult vaccine? Have you ever had a health care professional prescribe one to you? So, how about your boss? — Begin with previous general vaccination experiences, including, if available, historical service satisfaction. Practical Considerations Have you ever gone to get vaccines The COVID-19 vaccine – — Vaccines available on-site access — General vaccination – where to receive (If you were previously immunized as an adult): What did you think was nice about what transpired in the health center when you got the vaccine? Was there anything you didn't like? What do you believe you could do differently next time? Can you tell me how you would go about getting a COVID-19 vaccine? Begin with the basics. Probe: — Would you have to seek for permission? — Request a narrative outlining how they may obtain the vaccination, including costs, lost workdays, transportation, and any required permits. — Also discuss how they believe they can get the vaccination more easily. 51 vaccinations — Vaccination availability — General vaccination – cost — Vaccines in general – customer satisfaction — Vaccines in general — service quality — Would you or did you go grab it? (Does the hospital have the vaccine?) — How did/would you get there? — Would you have to complete it on your own time (rather than during your shift)? — Will there be / was there a cost to you (not just for the vaccination, but also for things like transportation)? — How much do you trust the health care person who will administer the vaccine? - Closing remarks What would make getting a COVID-19 vaccination easier for you if it was recommended and available? Is there anything else on your Allow for unanticipated mind? discoveries or expansion on previously stated ideas. Appendix III: Consent Form STUDY TITLE: UPTAKE OF COVID-19 VACCINES: EXPERIENCES OF HEALTH CARE WORKERS AT PETAUKE DISTRICT HOSPITAL I consent to take part in a study project directed by DEAN FRED LUPUPA MWENYA, a University of Lusaka Leopards Hill Campus 4th Year BSC Public Health Student. The goal of this paper is to spell out the conditions of my involvement in the project by way of an interview. 1. The researcher has given me enough information on this study endeavour. The goal of my involvement in this research as an interviewee has been stated to me and is clear. 2. I am involved in this study as an interviewee on an entirely optional basis. I have not been no coerced to engage in, either explicitly or implicitly. 3. Being interviewed by the lead researcher is part of the participation. The interview should last about 20 minutes. During the interview, I enable the researcher to take written notes. I may also agree to the interview being recorded (audio). 52 4. I clearly retain the right to refuse to respond to any question I don’t feel like answering. I can withdraw from the interview if I am made uncomfortable in any way during the interview. 5. I have been given express assurances that the researcher would not identify me by name or function in any reports based on material acquired from this interview if I want it, and that my confidentiality as a participant in this study will be protected. In all situations, further uses of records and data will be governed by the University of Lusaka's regular data usage regulations. 6. I have received confirmation that this research study has been evaluated and authorized by the University of Lusaka Ethics Committee. 7. I have read and comprehended all of the points and statements on this form. I have gotten sufficient answers to all of my questions, and by signing this form, I voluntarily agree to participate in this study. 8. I was provided a copy of this consent form, which was signed by the interviewer. ____________________________ Participant’s Signature: ________________________ Date: ____________________________ Researcher’s Signature: ________________________ Date: Appendix IV: Work plan TASKS Feb- Mar- Apri22 22 22 Proposal development and completion Ethical approval Data collection Data analysis Report writing Final report submission May22 Jun22 Jul- Aug22 22 Sep22 Oct22 Nov22 Dec22 53 Appendix V: Budget ITEMS PLAIN PAPER WRITING PADS PENS PRINTING PHOTOCOPYING TALKTIME TRANSPORT MISCELLANEOUS TOTAL COST (ZMK) K100 K120 K30 K350 K150 K250 K500 K300 K1800 54 Appendix VI: UNILUS Letter 55 56 Appendix VII: NHRA Approval Letter 57