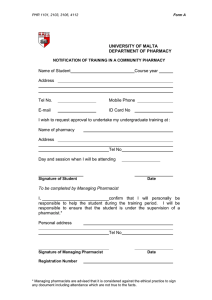

DEPARTMENT OF LIFELONG LEARNING Student Name: Natasha D Silva Student Number: C00290843 Subject Name: Medical Device Technology: Design, Development and Testing Lecturer Name: John Byrne Assignment No: CA02 Total word count: 1,600 DECLARATION I declare that all material in this submission e.g. thesis/essay/project/assignment is entirely my/our own work except where duly acknowledged. I have cited the sources of all quotations, paraphrases, summaries of information, tables, diagrams or other material; including software and other electronic media in which intellectual property rights may reside. I have provided a complete bibliography of all works and sources used in the preparation of this submission. I understand that failure to comply with the Institute’s regulations governing plagiarism constitutes a serious offence. Student Name: (Printed) Natasha D Silva Student Number(s): C00290843 Programme Title & Year: Medical Device Regulatory Affairs Module : Medical Device Technology: Design, Development and Testing Signature(s): Natasha D Silva Date: 04/04/2023 Note: a) An individual declaration is required by each student for joint projects. b) Where projects are submitted electronically, students are required to type their name under signature. c) The Institute regulations on plagiarism are set out in Section 10 of Examination and Assessment Regulations published each year in the Student Handbook. Risk Scenario and its Mitigation Introduction The goal of risk management in the healthcare industry is to identify, monitor, evaluate, reduce, and avoid risks to patients. It entails a complicated network of clinical and administrative systems, processes, procedures, and reporting structures. Every year, about 98,000 individuals (about the seating capacity of the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum) die from medical mistakes while hospitalized (Institute of Medicine, 2000). Medical care today is fraught with risk. Although the healthcare system is made up of numerous individual participants, collaboration is the key to achieving its final objectives of patient care and safety. When medical mistakes occur, even if they are caused by an individual's actions, the organization must take the proper next steps to recognize, learn from, and enhance the prevention of such events. This places more emphasis on systemic policy changes than on individual actions (McGowan, et al. 2022). Patient harm has long been attributed to medication-related mistakes, which can include incorrect dosage, incorrect administration, and giving patients drugs to which, they have a known intolerance. As an additional measure to prevent medication-related errors, many hospitals have increased the accessibility and visibility of pharmacists. This includes 24-hour pharmacist phone consultations, pharmacist review and sign-off on all medication orders, and physical presence of a clinical pharmacist in higher risk medical settings, such as intensive care and emergency medicine (McGowan, et al. 2022). Instead of placing blame on individuals for human errors, healthcare professionals and patients need to be protected by a multi-faceted system and culture of protection. Incident A patient safety incident is a situation or occurrence that might have caused unneeded harm to a patient or did. The word "unnecessary" is used in this definition to acknowledge the fact that mistakes, infractions, patient abuse, and purposefully unsafe acts happen in the healthcare industry and are unnecessary incidents. A mistake is when a planned action is not carried out as meant or when the wrong plan is used (Runciman et al., 2009). A mistake is when a planned action is not carried out as meant or when the wrong plan is used. Errors can appear when the incorrect thing is done (commission) or when the right thing is not done (omission), depending on whether they occur during the planning or execution phase (Runciman et al., 2009). Wilson's disease, a genetic condition in which a person cannot correctly metabolize and excrete copper, was identified in a 12-year-old female patient. Initially, there was a nine-month delay during which the child was diagnosed with a liver disease. The need for therapy from a pediatric hepatologist caused an additional delay. However, the pediatric hepatologist recommended a 30day supply of the chelating agent Penicillamine, a drug that binds with copper and aids the body in excreting it, as well as Zinc Acetate and Vitamin B6 when the patient was finally diagnosed. Three refills were recorded for each prescription (Healthcare Providers Service Organization, n.d.). The pharmacist was a contract employee hired by a national network of pharmacies. Only a few days had passed since she started working for the drugstore when the patient's electronic medication was transmitted to the store. She filled in the wrong order, which was for a 30-day quantity of penicillin 250 mg) BID (twice a day) instead of penicillamine BID. The pharmacist was not working at the drugstore when the patient picked up their Penicillamine prescription because she had only been employed temporarily. The pharmacy continued to complete the order for penicillin instead of penicillamine over the subsequent nine months, compounding the pharmacist's mistake. The patient's hepatologist raised the patient's dose from BID to TID (three times a day) at one time during the nine-month course of treatment because the patient's serum liver enzymes and copper levels in her urine were not getting better. The patient was taken to a nearby emergency room (ED) by her mother during month eight of taking the wrong medicine due to a two-day history of a rash with little relief from taking an over the counter (OTC) antihistamine. The child's hepatologist was contacted by the ED doctor, who concluded that Wilson's disease or an allergic response to Penicillamine were not probable causes of the child's rash. The patient should start taking a steroid dose pack, increase the antihistamine dosage, and follow up with the pediatric hepatologist in two days, both parties concurred. Despite the ED labeling her prescription as Penicillin 250 mg TID rather than Penicillamine, the medication error was still not discovered at the follow-up visit. A few weeks later, the mother brought the patient to a separate ED because her rash was getting worse, she had a fever, and she was experiencing new joint discomfort. The kid was decided to be admitted for potential Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia Systemic Symptoms (DRESS) condition during the ED appointment. A hospital pharmacist eventually found the prescription mistake after the patient was admitted (Healthcare Providers Service Organization, n.d.). Root Cause Analysis A technique or methodology known as root cause analysis (RCA) is used to examine an incident to help identify health system failures that might not be immediately obvious at initial review (Singh, et al. 2021). An RCA's goal is to pinpoint system flaws that caused or enabled the incident to occur and to make suggestions for steps that should be taken to stop or lessen the likelihood of a repeat of the same incident. Since this medication error falls under the previously mentioned description of a patient safety incident, an RCA was performed. The RCA team was appointed (Singh, et al. 2021). A root cause analysis takes place to investigate: -what happened during the treatment which caused harm to a patient -why did the incident take place -how can the incident be avoided in the future Figure 1: Ishikawa Fish Bone Analysis Data was taken from medical records, pharmacy records and interviews were held with the concerned parties such as the patient's mother, the initial pharmacist, the pediatric hepatologist and the doctor from the first emergency department visit. A fishbone diagram was used to identify the potential causes of the medical error. -Human factors: The initial pharmacist must have been inexperienced, distracted or fatigued. This could also be the case for the personnel in the pharmacy who continued to dispense the drug, the pediatric hepatologist and the ED doctor. - Communication breakdowns: There could have been a miscommunication between the various personnel involved such as the initial pharmacist and the pharmacists who continue to dispense the drug or in between the pediatric hepatologist and the first ED doctor. - Systemic issues: the medication ordering or dispensing process may be confusing or prone to errors. Especially in this case both the drugs sound alike. The pharmacy or the hospital at which the pediatric hepatologist worked did not have effective medication safety protocols in place. Resolutions: - When entering a drug purchase into the pharmacy computer, abide by pharmacy procedures and use only authorized Sig codes or mnemonics (Healthcare Providers Service Organization, n.d.). - Never presume that names with similar sounds are interchangeable. One of the main contributors to pharmacy mistakes is names with similar sounds. Sound-alike drugs should be distinguished from one another and plainly labeled, including with the use of obvious warning labels. - For added safety, make sure that all medications are examined before being filled, ideally by a different pharmacist. Each prescription must be compared to the original order when it is filled by a single pharmacist, who must also ensure that the right medication, dosage, and quantity are given to patients, and that the label, patient directions, and any applicable warnings are accurate (Healthcare Providers Service Organization, n.d.). - Do thorough study on the uses, side effects, and risks of any new medications before dispensing them. - Make sure that each pharmacy computer is set up to provide up-to-date, thorough drug research that is updated immediately or otherwise delivered on a regular basis for each pharmacy employee. - Once the drug has been thoroughly studied and understood, it is important to explain the patient's clinical history, diagnosis, and drug usage to make sure the medication given is suitable for the desired clinical effect. - Any computerized warning override should be treated as an incident, and you should routinely review all overrides to look for system errors, formulary gaps, insufficient or incorrect Sig codes, practitioner ordering issues, and competency problems with pharmacists and pharmacy technicians. - Regarding any queries about the recommended medication, such as contraindications and interactions, speak with the prescribing practitioner and, if necessary, seek advice from the supervising pharmacist or pharmacy director (Healthcare Providers Service Organization, n.d.). Conclusion Root cause analysis can be used to find factors within the process that may make it more difficult to provide high-quality patient treatment when identifying medical errors becomes challenging or complex due to numerous underlying factors (Singh, et al. 2021). Given that most medical errors are preventable, conducting a thorough root cause analysis can increase patient safety and help healthcare companies set an example for others. Understanding the "Why" behind the cause of a medical error and identifying potential future strategies to mitigate it and improve patient outcomes require the collaboration of all healthcare team members and clinicians involved in patient care (Singh, et al. 2021). References Healthcare Providers Service Organization (n.d.). Case Study: Wrong Drug Repeatedly Dispensed over nine-month Period Leads to Hospital Admission. [online] www.hpso.com. Available at: https://www.hpso.com/Resources/Legal-and-Ethical-Issues/Wrong-drugrepeatedly-dispensed-over-nine-month-pe [Accessed 4 Apr. 2023]. Institute of Medicine (2000). To Err Is Human. [online] Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.17226/9728. McGowan, J., Wojahn, A. and Nicolini, J.R. (2022). Risk Management Event Evaluation and Responsibilities. [online] PubMed. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559326/ [Accessed 3 Apr. 2023]. Runciman, W., Hibbert, P., Thomson, R., Van Der Schaaf, T., Sherman, H. and Lewalle, P. (2009). Towards an International Classification for Patient Safety: key concepts and terms. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 21(1), pp.18–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzn057. Singh, G., Patel, R.H. and Boster, J. (2021). Root Cause Analysis and Medical Error Prevention. [online] PubMed. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK570638/ [Accessed 4 Apr. 2023].