Intermediate Accounting: IFRS

Edition

Fourth Edition

DONALD E. KIESO PhD, CPA

Northern Illinois University DeKalb, Illinois

JERRY J. WEYGANDT PhD, CPA

University of Wisconsin—Madison Madison, Wisconsin

TERRY D. WARFIELD, PhD

University of Wisconsin—Madison Madison, Wisconsin

DEDICATED TO

Our wives, Donna, Enid, and Mary, for their love, support, and

encouragement

DIRECTOR AND VICE PRESIDENT

Michael McDonald

EXECUTIVE EDITOR

Emily Marcoux

CONTENT DEVELOPMENT EDITOR

Lindsey Myers

EDITORIAL SUPERVISORS

Terry Ann Tatro/Nicola Smith

SENIOR DEVELOPMENT AND PRODUCTION MANAGER Ed Brislin

SENIOR PRODUCTION EDITORS

Elena Saccaro/Rachel Conrad

DIRECTOR OF MARKETING

Karolina Honsa Zarychta

MARKETING MANAGER

Jenny Geiler

SENIOR DESIGNER

Wendy Lai

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Kirsten Loose

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

Natalie Munoz

COVER IMAGE

© Elymas / Shutterstock

(BACKCOVER)

© Hero Images/Getty Images

Copyright © 2020 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may

be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted

under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior

written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate percopy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923,

website www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to

the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 070305774, (201)748-6011, fax (201)748-6008, website http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

To order books or for customer service, please call 1-800-CALL WILEY (225-5945).

ISBN-13 978-1-119503682

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

DEDICATED TO

Copyright

From the Authors

About the Authors

New to This Edition

Proven Pedagogical Framework

Acknowledgments

CHAPTER 1: Financial Reporting and Accounting Standards

Global Markets

Objective of Financial Reporting

Standard-Setting Organizations

Financial Reporting Challenges

Review and Practice

Global Accounting Insights

CHAPTER 2: Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting

Conceptual Framework

Fundamental Concepts

Assumptions

Measurement, Recognition, and Disclosure Concepts

Review and Practice

Global Accounting Insights

CHAPTER 3: The Accounting Information System

Accounting Information System

Record and Summarize Basic Transactions

Identify and Prepare Adjusting Entries

Preparing Financial Statements

Financial Statements for a Merchandising Company

APPENDIX 3A: Cash-Basis Accounting versus AccrualBasis Accounting

Conversion from Cash Basis to Accrual Basis

Theoretical Weaknesses of the Cash Basis

APPENDIX 3B: Using Reversing Entries

Illustration of Reversing Entries—Accruals

Illustration of Reversing Entries—Deferrals

Summary of Reversing Entries

APPENDIX 3C: Using a Worksheet: The Accounting Cycle

Revisited

Worksheet Columns

Preparing Financial Statements from a Worksheet

Review and Practice

Global Accounting Insights

CHAPTER 4: Income Statement and Related Information

Income Statement

Content and Format of the Income Statement

Reporting Various Income Items

Accounting Changes and Errors

Related Equity Statements

Review and Practice

Global Accounting Insights

CHAPTER 5: Statement of Financial Position and Statement of

Cash Flows

Statement of Financial Position

Preparation of the Statement of Financial Position

Statement of Cash Flows

Additional Information

APPENDIX 5A: Ratio Analysis—A Reference

Using Ratios to Analyze Performance

Review and Practice

Global Accounting Insights

CHAPTER 6: Accounting and the Time Value of Money

Basic Time Value Concepts

Single-Sum Problems

Annuities (Future Value)

Annuities (Present Value)

Other Time Value of Money Issues

Review and Practice

CHAPTER 7: Cash and Receivables

Cash

Receivables

Valuation of Accounts Receivable

Notes Receivable

Other Issues Related to Receivables

APPENDIX 7A: Cash Controls

Using Bank Accounts

The Imprest Petty Cash System

Physical Protection of Cash Balances

Reconciliation of Bank Balances

Review and Practice

Global Accounting Insights

CHAPTER 8: Valuation of Inventories: A Cost-Basis Approach

Inventory Issues

Goods and Costs Included in Inventory

Which Cost Flow Assumption to Adopt?

Effect of Inventory Errors

APPENDIX 8A: LIFO Cost Flow Assumption

Last-In, First-Out (LIFO)

Inventory Valuation Methods—Summary Analysis

Review and Practice

CHAPTER 9: Inventories: Additional Valuation Issues

Lower-of-Cost-or-Net Realizable Value (LCNRV)

Valuation Bases

The Gross Profit Method of Estimating Inventory

Retail Inventory Method

Presentation and Analysis

Review and Practice

Global Accounting Insights

CHAPTER 10: Acquisition and Disposition of Property, Plant,

and Equipment

Property, Plant, and Equipment

Borrowing Costs During Construction

Valuation of Property, Plant, and Equipment

Costs Subsequent to Acquisition

Disposition of Property, Plant, and Equipment

Review and Practice

CHAPTER 11: Depreciation, Impairments, and Depletion

Depreciation—A Method of Cost Allocation

Other Depreciation Issues

Impairments

Depletion

Revaluations

Presentation and Analysis

APPENDIX 11A: Revaluation of Property, Plant, and

Equipment

Revaluation of Land

Revaluation of Depreciable Assets

Review and Practice

Global Accounting Insights

CHAPTER 12: Intangible Assets

Intangible Asset Issues

Types of Intangible Assets

Goodwill

Impairment and Presentation of Intangible Assets

Research and Development Costs

Review and Practice

Global Accounting Insights

CHAPTER 13: Current Liabilities, Provisions, and

Contingencies

Current Liabilities

Provisions

Contingencies

Presentation and Analysis

Review and Practice

CHAPTER 14: Non-Current Liabilities

Bonds Payable

Long-Term Notes Payable

Extinguishment of Non-Current Liabilities

Presentation and Analysis

Review and Practice

Global Accounting Insights

CHAPTER 15: Equity

Corporate Capital

Reacquisition of Shares

Dividend Policy

Presentation and Analysis of Equity

APPENDIX 15A: Dividend Preferences and Book Value per

Share

Dividend Preferences

Book Value per Share

Review and Practice

Global Accounting Insights

CHAPTER 16: Dilutive Securities and Earnings per Share

Dilutive Securities

Share Warrants

Share Compensation Plans

Basic Earnings per Share

Diluted Earnings per Share

APPENDIX 16A: Accounting for Share-Appreciation Rights

SARs—Share-Based Equity Awards

SARs—Share-Based Liability Awards

Share-Appreciation Rights Example

APPENDIX 16B: Comprehensive Earnings per Share

Example

Diluted Earnings Per Share

Review and Practice

Global Accounting Insights

CHAPTER 17: Investments

Debt Investments

Equity Investments

Other Reporting Issues

APPENDIX 17A: Accounting for Derivative Instruments

Defining Derivatives

Who Uses Derivatives, and Why?

Basic Principles in Accounting for Derivatives

Derivatives Used for Hedging

Other Reporting Issues

Comprehensive Hedge Accounting Example

Controversy and Concluding Remarks

APPENDIX 17B: Fair Value Disclosures

Disclosure of Fair Value Information: Financial

Instruments

Disclosure of Fair Values: Impaired Assets or

Liabilities

Conclusion

Review and Practice

Global Accounting Insights

CHAPTER 18: Revenue Recognition

Fundamentals of Revenue Recognition

The Five-Step Process Revisited

Accounting for Revenue Recognition Issues

Presentation and Disclosure

APPENDIX 18A: Long-Term Construction Contracts

Revenue Recognition over Time

APPENDIX 18B: Revenue Recognition for Franchises

Franchise Accounting

Recognition of Franchise Rights Revenue over Time

Review and Practice

CHAPTER 19: Accounting for Income Taxes

Fundamentals of Accounting for Income Taxes

Additional Issues

Accounting for Net Operating Losses

Financial Statement Presentation

APPENDIX 19A: Comprehensive Example of Interperiod

Tax Allocation

First Year—2021

Second Year—2022

APPENDIX 19B: Accounting for Net Operating Loss

Carrybacks

Loss Carryback

Review and Practice

Global Accounting Insights

CHAPTER 20: Accounting for Pensions and Postretirement

Benefits

Fundamentals of Pension Plan Accounting

Using a Pension Worksheet

Past Service Cost

Remeasurements

Reporting Pension Plans in Financial Statements

Review and Practice

Global Accounting Insights

CHAPTER 21: Accounting for Leases

The Leasing Environment

Lessee Accounting

Lessor Accounting

Special Lease Accounting Problems

Appendix 21A: Sale-Leasebacks

Accounting Issues in Sale-Leaseback Transactions

Sale-Leaseback Example

Appendix 21B: Comprehensive Example

Lease Terms: Scenario 1

Lease Terms: Scenario 2

Review and Practice

Global Accounting Insights

CHAPTER 22: Accounting Changes and Error Analysis

Accounting Changes

Changes in Accounting Estimates

Accounting Errors

Error Analysis

Review and Practice

Global Accounting Insights

CHAPTER 23: Statement of Cash Flows

The Statement of Cash Flows

Preparing the Statement of Cash Flows

Special Problems in Statement Preparation

Use of a Worksheet

Review and Practice

Global Accounting Insights

CHAPTER 24: Presentation and Disclosure in Financial

Reporting

Full Disclosure Principle

Disclosure Issues

Auditor’s and Management’s Reports

Current Reporting Issues

Appendix 24A: Basic Financial Statement Analysis

Perspective on Financial Statement Analysis

Ratio Analysis

Comparative Analysis

Percentage (Common-Size) Analysis

Appendix 24B: First-Time Adoption of IFRS

General Guidelines

Implementation Steps

Summary

Review and Practice

Global Accounting Insights

Appendix A: Specimen Financial Statements: Marks and

Spencer Group plc

Appendix B: Specimen Financial Statements: adidas AG

Appendix C: Specimen Financial Statements: Puma Group

Company Index

Subject Index

End User License Agreement

List of Tables

CHAPTER 6

Table 6.1 Future Value of 1 (Future Value of a Single

Sum)

Table 6.2 Present Value of 1 (Present Value of a Single

Sum)

Table 6.3 Future Value of an Ordinary Annuity of 1

Table 6.4 Present Value of an Ordinary Annuity of 1

Table 6.5 Present Value of an Annuity Due of 1

List of Illustrations

CHAPTER 1

ILLUSTRATION 1.3 Capital Allocation Process

ILLUSTRATION 1.4 International Standard-Setting

Structure

ILLUSTRATION 1.5 IASB Due Process

ILLUSTRATION 1.6 User Groups that Influence the

Formulation of Accounting Standards

CHAPTER 2

ILLUSTRATION 2.1 Conceptual Framework for

Financial Reporting

ILLUSTRATION 2.2 Hierarchy of Accounting Qualities

ILLUSTRATION 2.4 Fair Value Hierarchy

ILLUSTRATION 2.5 The Five Steps of Revenue

Recognition

ILLUSTRATION 2.7 Conceptual Framework for

Financial Reporting

CHAPTER 3

ILLUSTRATION 3.1 Double-Entry (Debit and Credit)

Accounting System

ILLUSTRATION 3.2 The Basic Accounting Equation

ILLUSTRATION 3.3 Expanded Equation and

Debit/Credit Rules and Effects

ILLUSTRATION 3.4 Income Statement and Equity

Relationships

ILLUSTRATION 3.5 Effects of Transactions on Equity

Accounts

ILLUSTRATION 3.6 The Accounting Cycle

ILLUSTRATION 3.8 Posting a Journal Entry

ILLUSTRATION 3.10 Investment of Cash by

Shareholders

ILLUSTRATION 3.11 Purchase of Office Equipment

ILLUSTRATION 3.12 Receipt of Cash for Future Service

ILLUSTRATION 3.13 Payment of Monthly Rent

ILLUSTRATION 3.14 Payment for Insurance

ILLUSTRATION 3.15 Purchase of Supplies on Credit

ILLUSTRATION 3.16 Signing a Contract

ILLUSTRATION 3.17 Declaration and Payment of

Dividend

ILLUSTRATION 3.18 Payment of Salaries

ILLUSTRATION 3.19 Receipt of Cash for Services

Provided

ILLUSTRATION 3.22 Adjusting Entries for Deferrals

ILLUSTRATION 3.23 Adjustment for Supplies

ILLUSTRATION 3.24 Adjustment for Insurance

ILLUSTRATION 3.25 Adjustment for Depreciation

ILLUSTRATION 3.27 Adjustment for Unearned Service

Revenue

ILLUSTRATION 3.28 Adjusting Entries for Accruals

ILLUSTRATION 3.29 Accrual Adjustment for

Receivable and Revenue Accounts

ILLUSTRATION 3.30 Formula for Computing Interest

for One Month

ILLUSTRATION 3.31 Adjustment for Interest

ILLUSTRATION 3.32 Accrued Salaries and Wages

ILLUSTRATION 3.33 Adjustment for Salaries and

Wages Expense

ILLUSTRATION 3.34 Adjustment for Bad Debt

ILLUSTRATION 3.36 Preparation of the Income

Statement and Retained Earnings Statement from the

Adj…

ILLUSTRATION 3.37 Preparation of the Statement of

Financial Position from the Adjusted Trial Balan…

ILLUSTRATION 3.39 Posting of Closing Entries

ILLUSTRATION 3A.12 Conversion of Statement of Cash

Receipts and Disbursements to Income Statement

ILLUSTRATION 3C.1 Use of a Worksheet

CHAPTER 4

ILLUSTRATION 4.7 Number of Unusual Items

Reported in a Recent Year by 500 Large Companies

CHAPTER 5

ILLUSTRATION 5.19 Cash Inflows and Outflows

CHAPTER 6

ILLUSTRATION 6.1 Simple vs. Compound Interest

ILLUSTRATION 6.6 Basic Time Diagram

ILLUSTRATION 6.13 Time Diagram to Solve for

Unknown Number of Pe…

ILLUSTRATION 6.15 Time Diagram to Solve for

Unknown Interest Rate

ILLUSTRATION 6.17 Solving for the Future Value of an

Ordinary Annuity

ILLUSTRATION 6.21 Comparison of the Future Value

of an Ordinary Annuity with an Annuity Due

ILLUSTRATION 6.22 Annuity Due Time Diagram

ILLUSTRATION 6.24 Future Value of Ordinary Annuity

Time Diagram (n = 10, i = 4%)

ILLUSTRATION 6.25 Future Value of Ordinary Annuity

Time Diagram, to Solve for Unknown Number of Pe…

ILLUSTRATION 6.26 Future Value Annuity Due Time

Diagram (n = 30, i = 9%)

ILLUSTRATION 6.28 Solving for the Present Value of

an Ordinary Annuity

ILLUSTRATION 6.31 Comparison of Present Value of

an Ordinary Annuity with an Annuity Due

ILLUSTRATION 6.33 Time Diagram to Solve for Present

Value of Lottery Payments

ILLUSTRATION 6.34 Time Diagram to Solve for

Effective-Interest Rate on Loan

ILLUSTRATION 6.35 Time Diagram for Ordinary

Annuity for a College Fund

ILLUSTRATION 6.37 Time Diagram for Present Value

of Deferred Annuity

ILLUSTRATION 6.39 Time Diagram for Present Value

of Deferred Annuity (Two-Step Process)

CHAPTER 7

ILLUSTRATION 7.4 Entries under Gross and Net

Methods of Recording Cash (Sales) Discounts

ILLUSTRATION 7.7 Time Diagram for Note Issued at

Face Value

ILLUSTRATION 7.9 Time Diagram for Zero-InterestBearing Note

ILLUSTRATION 7.11 Time Diagram for Interest-Bearing

Note

ILLUSTRATION 7.14 Basic Procedures in Factoring

ILLUSTRATION 7.17 Entries for Transfer of Receivables

—Secured Borrowing

ILLUSTRATION 7.18 Accounting for Transfers of

Receivables

ILLUSTRATION 7.19 Disclosure of Receivables

CHAPTER 8

ILLUSTRATION 8.2 Flow of Costs through

Manufacturing and Merchandising Companies

ILLUSTRATION 8.3 Inventory Cost Flow

ILLUSTRATION 8.4 Comparative Entries—Perpetual vs.

Periodic

ILLUSTRATION 8.6 Entries under Gross and Net

Methods

ILLUSTRATION 8.11 FIFO Method—Perpetual

Inventory

ILLUSTRATION 8.15 Effect of Ending Inventory Error

on Two Period

ILLUSTRATION 8A.2 LIFO Method—Perpetual

Inventory

CHAPTER 9

ILLUSTRATION 9.5 Accounting for the Reduction of

Inventory to Net Realizable Value—Perpetual Inve…

ILLUSTRATION 9.16 Application of Gross Profit

Formulas

ILLUSTRATION 9.21 Comprehensive Conventional

Retail Inventory Method Format

ILLUSTRATION 9.22 Conventional Retail Inventory

Method—Special Items Included

ILLUSTRATION 9.23 Disclosure of Inventory Methods

CHAPTER 10

ILLUSTRATION 10.1 Capitalization of Borrowing Costs

ILLUSTRATION 10.8 Accounting for Exchanges

CHAPTER 11

ILLUSTRATION 11.11 Calculation of Partial-Period

Depreciation, Two Methods

ILLUSTRATION 11.15 Impairment Test

ILLUSTRATION 11.18 Graphic of Accounting for

Impairments

ILLUSTRATION GAAP 11.1 U.S. GAAP Impairment

Measurement

CHAPTER 12

ILLUSTRATION 12.1 Research and Development Stages

ILLUSTRATION 12.6 Determination of Goodwill—

Master Valuation Approach

ILLUSTRATION 12.12 Nestlé’s Intangible Asset

Disclosures

ILLUSTRATION 12.14 Research Activities versus

Development Activities

CHAPTER 13

ILLUSTRATION 13.4 Summary of Payroll Liabilities

CHAPTER 14

ILLUSTRATION 14.1 Time Diagram for Bonds Issued at

Par

ILLUSTRATION 14.3 Time Diagram for Bonds Issued at

a Discount

ILLUSTRATION 14.5 Bond Discount and Premium

Amortization Computation

ILLUSTRATION 14.14 Time Diagram for Zero-Interest

Note

ILLUSTRATION 14.18 Time Diagram for InterestBearing Note

CHAPTER 15

ILLUSTRATION 15.3 Issuance of Shares for Patent

ILLUSTRATION 15.4 Share Issuances/Buybacks 2004–

2018

ILLUSTRATION 15.10 Cash Dividend Entries

CHAPTER 16

ILLUSTRATION 16.1 Convertible Debt Components

ILLUSTRATION 16.2 Time Diagram for Convertible

Bond

ILLUSTRATION 16.10 Compensation Elements

ILLUSTRATION 16.11 Share-Option Plan Disclosure

ILLUSTRATION 16.23 Relation between Basic and

Diluted EPS

ILLUSTRATION 16.32 Reconciliation for Basic and

Diluted EPS

ILLUSTRATION 16.33 Calculating EPS, Simple Capital

Structure

ILLUSTRATION 16.34 Calculating EPS, Complex

Capital Structure

CHAPTER 17

ILLUSTRATION 17.20 Comparison of Fair Value and

Equity Method

ILLUSTRATION 17.24 HFCS Impairment Entries

ILLUSTRATION 17.26 Impairment Entries—Increase in

Credit Risk

ILLUSTRATION 17A.7 Effect of Hedge on Cash Flows

ILLUSTRATION 17A.9 Swap Transaction

ILLUSTRATION 17A.10 Interest Rate Swap

ILLUSTRATION 17A.13 Impact on Financial Statements

of Fair Value Hedge

CHAPTER 18

ILLUSTRATION 18.1 Key Concepts of Revenue

Recognition

ILLUSTRATION 18.2 Five Steps of Revenue

Recognition

ILLUSTRATION 18B.2 Franchise Entries—Inception

and Commencement of Operations

ILLUSTRATION 18B.3 Franchise Entries—First Year of

Franchise Operations

ILLUSTRATION 18B.5 Franchise Entries—Revenue

Recognized over Time

CHAPTER 19

ILLUSTRATION 19.1 Fundamental Differences Between

Financial and Tax Reporting

ILLUSTRATION 19.6 Reversal of Temporary Difference,

Chelsea Inc.

ILLUSTRATION 19.17 Reversal of Temporary

Difference, Cunningham Inc.

ILLUSTRATION 19.18 IFRS and Tax Reporting,

Hunt Company

ILLUSTRATION 19.29 Examples of Temporary

Differences

ILLUSTRATION 19.30 Tax Effects of Originating and

Reversing Differences

ILLUSTRATION 19.31 Examples of Permanent

Differences

ILLUSTRATION 19.36 Loss Carryforward Procedure

ILLUSTRATION 19.42 Possible Sources of Taxable

Income

ILLUSTRATION 19.48 Basic Principles of the AssetLiability Method

ILLUSTRATION 19.49 Procedures for Computing and

Reporting Deferred Income Taxes

ILLUSTRATION 19A.13 Schedule of Future Taxable and

Deductible Amounts, End of 2022

ILLUSTRATION 19B.1 Loss Carryback Procedure

CHAPTER 20

ILLUSTRATION 20.1 Flow of Cash Among Pension Plan

Participants

ILLUSTRATION 20.3 Different Measures of the

Pension Obligation

ILLUSTRATION 20.5 Reporting Changes in the Pension

Obligation (Assets)

ILLUSTRATION 20.9 Basic Format of Pension

Worksheet

ILLUSTRATION 20.10 Pension Worksheet—2022

ILLUSTRATION 20.13 Pension Worksheet—2023

ILLUSTRATION 20.16 Pension Worksheet—2024

ILLUSTRATION 20.19 Partial Pension Worksheet—

2025

CHAPTER 21

ILLUSTRATION 21.12 Journal Entries—Guaranteed

Residual Value

ILLUSTRATION 21.13 Final Payments—Guaranteed and

Unguaranteed Residual Value

ILLUSTRATION 21.15 Journal Entries by Lessee

ILLUSTRATION 21.18 Lessor Classification Tests

ILLUSTRATION 21.28 Entries for Guaranteed and

Unguaranteed Residual Values—Sales-Type Lease

ILLUSTRATION 21.39 Disclosure of Leases by Lessee

ILLUSTRATION 21.41 Disclosure of Leases by Lessor

ILLUSTRATION 21A.1 Sale-Leaseback

ILLUSTRATION 21A.2 Sale-Leaseback Accounting

ILLUSTRATION 21A.4 Comparative Entries for SaleLeaseback for Lessee and Lessor

ILLUSTRATION 21B.4 Lessee/Lessor Entries for

Finance/Sales-Type Lease

ILLUSTRATION 21B.8 Lessee Entries for Finance Lease

ILLUSTRATION 21B.9 Lessor Entries for Operating

Lease

ILLUSTRATION GAAP21.5 Lessee Operating Lease

Entries

CHAPTER 22

ILLUSTRATION 22.10 Comparative Information

Related to Accounting Change (FIFO)

ILLUSTRATION 22.21 Summary of Guidelines for

Accounting Changes and Errors

ILLUSTRATION 22.29 Worksheet to Correct Income

and Statement of Financial Position Errors

ILLUSTRATION 22.30 Worksheet to Analyze Effect of

Errors in Financial Statements

CHAPTER 23

ILLUSTRATION 23.1 Classification of Typical Cash

Inflows and Outflows

ILLUSTRATION 23.5 Net Income versus Net Cash Flow

from Operating Activities

ILLUSTRATION 23.17 Adjustments Needed to

Determine Net Cash Flow from Operating Activities—

Indirect…

ILLUSTRATION 23.21 Major Classes of Cash Receipts

and Payments

ILLUSTRATION 23.38 Format of Worksheet for

Preparation of Statement of Cash Flows

ILLUSTRATION 23.39 Comparative Statement of

Financial Position, Satellite Ltd.

ILLUSTRATION 23.41 Completed Worksheet for

Preparation of Statement of Cash Flows, Satellite Ltd.

CHAPTER 24

ILLUSTRATION 24.1 Types of Financial Information

ILLUSTRATION 24.4 Time Periods for Subsequent

Events

ILLUSTRATION 24.20 Types of Economic Crime

ILLUSTRATION 24B.1 First-Time Adoption Timeline

From the Authors

Globalization is occurring rapidly. As economic and other interactions

increase among countries, capital markets must provide high-quality

financial information. A need exists for high-quality financial

reporting standards that meet this objective. Fortunately,

International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) has broad

international acceptance and is being used in some form by more than

115 countries around the world. One securities regulator noted that

IFRS is best positioned to serve as the single set of high-quality

accounting standards.

CHANGE IS THE ONLY CONSTANT

Most countries want rapid action related to the acceptance of IFRS. A

number of countries have already switched from their own version of

accounting standards to IFRS. Students and instructors need

educational materials related to IFRS in order to meet this new

challenge. Our objective in revising Intermediate Accounting, IFRS

Edition, was to continue to provide the tools needed to understand

what IFRS is and how it is applied in practice. The emphasis on fair

value, the proper accounting for financial instruments, and the new

developments related to leasing, revenue recognition, and financial

statement presentation are examined in light of current practice. In

addition, given the rapid changes taking place, we provide and discuss

the new Conceptual Framework to understand how these issues will

likely be resolved in the future.

“If this text helps you appreciate the challenges, worth, and

limitations of financial reporting, if it encourages you to evaluate

critically and understand financial accounting concepts and

practice, and if it prepares you for advanced study, professional

examinations, and the successful and ethical pursuit of your career

in accounting or business in a global economy, then we will have

attained our objectives.”

A LOOK AT GLOBAL ACCOUNTING

While IFRS has achieved broad acceptance, not all countries have

adopted it. For example, U.S. companies still follow U.S. generally

accepted accounting principles (U.S. GAAP) in preparing their

financial statements. In fact, the differences between IFRS and U.S.

GAAP may provide certain companies with a competitive advantage,

so understanding these differences may be important in analyzing

company performance. In addition, the IASB and the FASB are

working together to converge their standards as appropriate.

Accordingly, we have included a Global Accounting Insights

section at the end of selected chapters, to highlight the important

differences that remain between IFRS and U.S. GAAP, as well as the

ongoing joint convergence efforts to resolve them. As a result,

students truly gain a global accounting education by studying this text.

INTERMEDIATE ACCOUNTING WORKS

Intermediate Accounting, Seventeenth Edition (based on U.S. GAAP),

is the market-leading text in providing the tools needed to understand

what U.S. GAAP is and how it is applied in practice. With this IFRS

Fourth Edition, we strive to continue to provide the material needed

to understand this subject area using IFRS. The text is comprehensive

and up-to-date, and provides the instructor with flexibility in the

topics to cover. We also include proven pedagogical tools, designed to

help students learn more effectively and to answer the changing needs

of this course.

We are excited about Intermediate Accounting, IFRS Fourth Edition.

We believe it meets an important objective of providing useful

information to educators and students interested in learning about

IFRS. Suggestions and comments from users of this text will be

appreciated. Please feel free to e-mail any one of us at

AccountingAuthors@yahoo.com.

Donald E. Kieso

Jerry J. Weygandt

Terry D. Warfield

Somonauk, Illinois

Madison, Wisconsin

Madison, Wisconsin

About the Authors

Don Kieso

DONALD E. KIESO, PhD, CPA, received his bachelor’s degree

from Aurora University and his doctorate in accounting from the

University of Illinois. He has served as chairman of the Department

of Accountancy and is currently the KPMG Emeritus Professor of

Accountancy at Northern Illinois University. He has public

accounting experience with Price Waterhouse & Co. (San Francisco

and Chicago) and Arthur Andersen & Co. (Chicago) and research

experience with the Research Division of the American Institute of

Certified Public Accountants (New York). He has done postdoctorate work as a Visiting Scholar at the University of California

at Berkeley and is a recipient of NIU’s Teaching Excellence Award

and four Golden Apple Teaching Awards. Professor Kieso is the

author of other accounting and business books and is a member of

the American Accounting Association, the American Institute of

Certified Public Accountants, and the Illinois CPA Society. He has

served as a member of the Board of Directors of the Illinois CPA

Society, then AACSB’s Accounting Accreditation Committees, the

State of Illinois Comptroller’s Commission, as Secretary-Treasurer

of the Federation of Schools of Accountancy, and as SecretaryTreasurer of the American Accounting Association. Professor Kieso

is currently serving on the Board of Trustees and Executive

Committee of Aurora University, as a member of the Board of

Directors of Kishwaukee Community Hospital, and as Treasurer and

Director of Valley West Community Hospital. From 1989 to 1993, he

served as a charter member of the National Accounting Education

Change Commission. He is the recipient of the Outstanding

Accounting Educator Award from the Illinois CPA Society, the FSA’s

Joseph A. Silvoso Award of Merit, the NIU Foundation’s

Humanitarian Award for Service to Higher Education, a

Distinguished Service Award from the Illinois CPA Society, and in

2003 an honorary doctorate from Aurora University.

Jerry Weygandt

JERRY J. WEYGANDT, PhD, CPA, is the Arthur Andersen

Alumni Emeritus Professor of Accounting at the University of

Wisconsin—Madison. He holds a Ph.D. in accounting from the

University of Illinois. Articles by Professor Weygandt have appeared

in the Accounting Review, Journal of Accounting Research,

Accounting Horizons, Journal of Accountancy, and other academic

and professional journals. These articles have examined such

financial reporting issues as accounting for price-level adjustments,

pensions, convertible securities, stock option contracts, and interim

reports. Professor Weygandt is the author of other accounting and

financial reporting books and is a member of the American

Accounting Association, the American Institute of Certified Public

Accountants, and the Wisconsin Society of Certified Public

Accountants. He has served on numerous committees of the

American Accounting Association and as a member of the editorial

board of the Accounting Review; he also has served as President and

Secretary-Treasurer of the American Accounting Association. In

addition, he has been actively involved with the American Institute

of Certified Public Accountants and has been a member of the

Accounting Standards Executive Committee (AcSEC) of that

organization. He has served on the FASB task force that examined

the reporting issues related to accounting for income taxes and

served as a trustee of the Financial Accounting Foundation.

Professor Weygandt has received the Chancellor’s Award for

Excellence in Teaching and the Beta Gamma Sigma Dean’s Teaching

Award. He is on the board of directors of M & I Bank of Southern

Wisconsin. He is the recipient of the Wisconsin Institute of CPA’s

Outstanding Educator’s Award and the Lifetime Achievement

Award. In 2001, he received the American Accounting Association’s

Outstanding Educator Award.

Terry Warfield

TERRY D. WARFIELD, PhD, is the PwC Professor in Accounting

at the University of Wisconsin—Madison. He received a B.S. and

M.B.A. from Indiana University and a Ph.D. in accounting from the

University of Iowa. Professor Warfield’s area of expertise is

financial reporting, and prior to his academic career, he worked for

five years in the banking industry. He served as the Academic

Accounting Fellow in the Office of the Chief Accountant at the U.S.

Securities and Exchange Commission in Washington, D.C. from

1995–1996. Professor Warfield’s primary research interests concern

financial accounting standards and disclosure policies. He has

published scholarly articles in The Accounting Review, Journal of

Accounting and Economics, Research in Accounting Regulation,

and Accounting Horizons, and he has served on the editorial boards

of The Accounting Review, Accounting Horizons, and Issues in

Accounting Education. He has served as president of the Financial

Accounting and Reporting Section, the Financial Accounting

Standards Committee of the American Accounting Association

(Chair 1995–1996), and on the AAA-FASB Research Conference

Committee. He also served on the Financial Accounting Standards

Advisory Council of the Financial Accounting Standards Board and

as a trustee of the Financial Accounting Foundation. Professor

Warfield has received teaching awards at both the University of

Iowa and the University of Wisconsin, and he was named to the

Teaching Academy at the University of Wisconsin in 1995. Professor

Warfield has developed and published several case studies based on

his research for use in accounting classes. These cases have been

selected for the AICPA Professor-Practitioner Case Development

Program and have been published in Issues in Accounting

Education.

New to This Edition

Content Changes by Chapter

Chapter 1: Financial Reporting and Accounting

Standards

New opening story on the current usage of IFRS and its impact

on public companies worldwide.

New What Do the Numbers Mean? (WDNM) box on IFRS for

SMEs, which is helping IFRS to gain traction with non-public

companies.

Chapter 2: Conceptual Framework for Financial

Reporting

Updated throughout to reflect the 2018 IASB Conceptual

Framework for Financial Reporting.

Chapter 3: The Accounting Information System

New opening story on blockchain.

Chapter 4: Income Statement and Related Information

Updated WDNM box on alternative performance measures

used by companies.

Chapter 5: Statement of Financial Position and

Statement of Cash Flows

Updated discussions throughout on recent status of IASB

project on the presentation in the statement of financial

position as well as that on performance reporting.

New footnote on recent IFRS on classification of current/noncurrent assets.

Chapter 6: Accounting and the Time Value of Money

Reformatted time diagram problems for improved

understanding and visualization.

Chapter 7: Cash and Receivables

New opening story, discussing current effect of TCJA in terms

of amounts of company cash parked overseas as well as foreign

cash balance disclosures.

Updated definition and discussion of cash equivalents per

recent IFRS.

Updated discussion of sales returns and allowances per recent

IFRS, including use of Return Liability account.

New Evolving Issue on what companies should include as part

of cash and cash equivalents on the statement of financial

position, such as cryptocurrencies (now classified as intangible

assets or inventory).

New WDNM box on the pros and cons of securitizations.

Chapter 8: Valuation of Inventories: A Cost-Basis

Approach

New WDNM box on retailers using an omnichannel approach

and the impact this has on inventory levels.

Chapter 9: Inventories: Additional Valuation Issues

New WDNM box on the corporate barter method to handle

problem inventory.

Chapter 10: Acquisition and Disposition of Property,

Plant, and Equipment

Updated discussion on borrowing costs during construction per

recent IFRS.

Updated discussion on involuntary conversion per recent IFRS.

Chapter 11: Depreciation, Impairments, and Depletion

Updated opening story on how technology companies are

especially vulnerable to impairment losses.

Updated definition of depreciation per recent IFRS.

Updated per recent IFRS requirement that companies review

estimates for residual value and service life annually and revise

if needed.

Updated WDNM box on revaluation accounting to highlight

how companies use it effectively in the hospitality industry.

Chapter 12: Intangible Assets

Updated for ASB project on goodwill.

Chapter 13: Current Liabilities, Provisions, and

Contingencies

Updated opening story to include most recent IASB position

and considerations regarding liabilities, including contingent

liabilities.

New WDNM box on how SAP’s current liabilities account can

signal both good and bad news for investors.

Chapter 14: Non-Current Liabilities

New opening story discussing how total global debt as well as

bond issuances continue to increase.

New WDNM box on negative interest rates—what they are, who

issues them, and who invests in them.

New footnote on recognition that LIBOR is no longer a reliable

measure of interest rates between banks and how the Financial

Stability Board has been tasked with determining more reliable

benchmark rates.

Chapter 15: Equity

Updated opening story for most recent data indicating

continued increase in global investment opportunities.

New introduction and illustration to emphasize current

prevalence in share buybacks.

Chapter 16: Dilutive Securities and Earnings per Share

Updated opening story to include most recent information

about median CEO pay by region to indicate increased usage of

share option awards in employee pay packages.

Updated footnote 1 to provide latest information regarding

IASB’s development of a standard that will improve the

financial reporting requirements for financial instruments with

characteristics of debt and equity.

Chapter 17: Investments

New opening story on whether IFRS 9 has actually resulted in

companies reporting more decision-useful information.

Updated footnote 1 on definition of financial assets per latest

IFRS.

New WDNM box on whether the single impairment model,

based on expected credit losses, will give banks and investors in

banks a better early warning of deteriorating credit quality.

Updated table showing differences between traditional and

derivative financial instruments based on latest IFRS.

Updated WDNM box on equity method accounting per IFRS 10,

as well as updated WDNM box on derivatives market per recent

data.

Chapter 18: Revenue Recognition

Updated opening story as companies have begun to implement

the most recent revenue recognition standard, including the

continuing challenge on the amount of judgment that is still

required in determining how to report revenue transactions and

how that relates to key audit matters (KAMs).

Replaced Evolving Issue with discussion on whether the most

recent revenue recognition standard represents a convergence

with U.S. GAAP or has actually resulted in more differences.

New WDNM box on how returns can significantly affect

reported revenues for e-commerce companies.

Chapter 19: Accounting for Income Taxes

Loss carryforward and loss carrybacks updated per recent tax

law changes; loss carrybacks now discussed in a new Appendix

19B.

WDNM box on global tax rates completed updated per most

recent information as well as the OECD and G20 BEPS (Base

Erosion and Profit Sharing) initiative.

Chapter 20: Accounting for Pensions and

Postretirement Benefits

Updated opening story, for most recent information on how the

financial crisis of 2008 is still impacting companies’ pension

plans.

Updated discussion of IAS 19 (see footnote 11 as well as

“Recognition of the Net Funded Status of the Pension Plan”

section) and how it limits amount of pension asset that is

recognized (the asset ceiling).

Chapter 21: Accounting for Leases

Updated opening story as new lease accounting rules are not

expected to be implemented until 2020, a slight delay.

New illustration showing Air France’s incorporation of new

lease accounting standard into its financial statements.

Chapter 22: Accounting Changes and Error Analysis

Updated opening story based on recent IFRS 9, IFRS 15, and

IFRS 16.

Updated WDNM box on accounting change estimates to show

the 10 most common changes in accounting estimates as well

as the positive/negative impacts of these changes on income.

Chapter 23: Statement of Cash Flows

Updated chapter to include most recent IFRS on cash

equivalents, as well as IFRS on disclosures needed if beginning

and ending cash balances on the statement of cash flows do not

reconcile.

New footnote discussing IASB’s Primary Financial Statements

project regarding interest and dividends paid or received.

Chapter 24: Presentation & Disclosure in Financial

Reporting

Updated opening story to include new IFRS practice statement

related to making materiality judgments.

New discussion and example of key audit matters (KAMs).

New discussion and example of alternative performance

measures.

Improved Digital Assets

Intermediate Accounting, IFRS Fourth Edition, is completely

integrated with Wiley’s online courseware, featuring a suite of

teaching and learning resources developed under the close review of

the authors. Driven by the same basic beliefs as the text, Wiley’s

online courseware allows students to create a personalized study

plan, assess their progress along the way, and access the content

and resources needed to master the material. Features of Wiley’s

online courseware includes the following:

NEW Data Analytics: Data Analytics activities include

corresponding data sets and assignments in Wiley’s online

courseware. These resources further prepare and enhance data

analytics skills that students will need in their future

accounting careers. Intermediate Accounting, IFRS Fourth

Edition, also includes a “Data Analytics and Accounting”

module within Wiley’s online courseware that contains seven

interactive lessons with industry-validated content to prepare

students for the evolving workforce, video tutorials of realworld data analytics applications, and a case study using Excel

that allows students to manipulate and think critically about

data.

Accessible Lecture PowerPoints: PowerPoints are a

hallmark of many lectures as well as an important study tool

for students. In addition to the fully accessible Wiley’s online

courseware course, we have also improved the lecture

PowerPoints to be accessible, including high-quality alt text and

screen-reader capabilities.

Proven Pedagogical Framework

This edition continues to provide numerous key learning aids to

help you master the text material and prepare you for a successful

career in accounting.

End-of-Chapter Pedagogy

Acknowledgments

Reviewers

Azlina Ahmad

Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia

Wilfredo Baltazar

De La Salle University

Dennis Chan

University of Bunda Mulia

Christine Cheng

University of Mississippi

Peng-Chia Chiu

The Chinese University of Hong Kong

Teresa Chu

University of Macau

Antonio Dayag

University of Santo Tomas

David Dettner

Export-Import Bank of the United States

Charmaine Felder

Brandman University

Kaleed Jaarat

Middle East University

Edmund Keung

National University of Singapore

Kevin Li Chi Keung

The Open University of Hong Kong

Paul Kimmel

University of Wisconsin—Madison

H.R. Sampath Kumar

Karnataka Vidyuth Karkhane Limited

Kurniawati

University of Bunda Mulia

Raji Lakshmi

Dr. Pauls Engineering College, India

Phil Larprom

University of Toronto

Jessica Lee

Hong Kong University of Science and Technology

Vincent Leung

Macao Polytechnic Institute

Tom Linsmeier

University of Wisconsin—Madison

Hsin-Tsai Liu

National Taiwan University

Daphne Main

Loyola University—New Orleans

Kingsley Olibe

Kansas State University

Can Ozturk

Cankaya University

Hannah Pantaran

Silliman University, Philippines

Fernando Penalva

IESE Business School

Nuchjaree Pichetkun

Rajamangala University of Technology, Thanyaburi

Nuraini Sari

Binus University

Dr. Charlie Sohn

University of Macau

Nai Hui Su (Suzanne)

National Chung Hsing University

Sukarnen Suwanto

Indonesia

Professor Ting-Wong

National Chengchi University

Rita Yip

Lingnan University

Amy Zang

The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology

Stephen Zeff

Rice University

Ancillary Authors, Contributors, Proofers, and

Accuracy Checkers

Tom Bader

Madison, Wisconsin

Ellen Bartley

St. Joseph’s College

LuAnn Bean

Florida Institute of Technology

John C. Borke

University of Wisconsin—Platteville

Melodi Bunting

Edgewood College

Jack Cathey

University of North Carolina—Charlotte

Andrew Debbink

Ernst & Young—Chicago

Jim Emig

Villanova University

Larry Falcetto

Emporia State University

Coby Harmon, University of California, Santa Barbara

Kimberly Hurt

Central Community College—Hastings

Mark Kohlbeck

Florida Atlantic University

Ellen Lettenberger

Madison, Wisconsin

Steven Lifland

High Point University

Jill Misuraca

University of Tampa

Barbara Muller

Arizona State University

Yvonne Phang

Borough of Manhattan Community College

Laura Prosser

Black Hills State University

Lynn Stallworth

Appalachian State University

Alice Sineath

Benedictine University

Dick D. Wasson

Southwestern College

Irene Wiecek

University of Toronto

Annette Foo Wai Yin

National University of Singapore

Lori Grady Zaher

Bucks County Community College

Practicing Accountants and Business Executives

From the fields of corporate and public accounting, we owe thanks

to the following practitioners for their technical advice and for

consenting to interviews.

Tracy Golden

Deloitte LLP

John Gribble

PricewaterhouseCoopers (retired)

Darien Griffin

S.C. Johnson & Son

Michael Lehman

Sun Microsystems, Inc. (retired)

Michele Lippert

Evoke.com

Sue McGrath

Vision Capital Management

David Miniken

Sweeney Conrad

Robert Sack

University of Virginia

Clare Schulte

Deloitte LLP

Willie Sutton

Mutual Community Savings Bank, Durham, NC

Mary Tokar

IASB

Lynn Turner

former SEC Chief Accountant

We give special acknowledgment and thanks to Professor Jack

Cathey for his significant contributions to the development of the

Intermediate Accounting, IFRS Fourth Edition. We benefited

greatly from his IFRS expertise and his student-oriented

perspectives as an educator.

We also appreciate the exemplary support and professional

commitment given us by the development, marketing, production,

and editorial staffs of John Wiley & Sons, including the following:

Michael McDonald, Emily Marcoux, Lindsey Myers, Rachel Conrad,

Elena Saccaro, and Wendy Lai. Thanks, too, to Cathy Castle and the

staff at Lumina for their work on the text and the solutions manual.

Suggestions and comments from users of this text will be

appreciated. Please feel free to e-mail any one of us.

Donald E. Kieso

Jerry J. Weygandt

Terry D. Warfield

Somonauk, Illinois Madison, Wisconsin Madison, Wisconsin

CHAPTER 1

Financial Reporting and Accounting Standards

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

1. Describe the global financial markets and their relation to

financial reporting.

2. Explain the objective of financial reporting.

3. Identify the major policy-setting bodies and their role in the

standard-setting process.

4. Discuss the challenges facing financial reporting.

This chapter also includes numerous conceptual

discussions that are integral to the topics presented here.

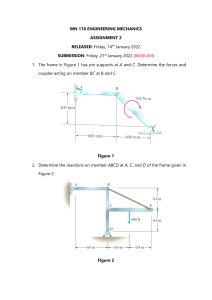

PREVIEW OF CHAPTER 1

As the following opening story indicates, countries are moving

quickly to adopt International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS).

It is estimated that over 300 of the 500 largest global companies are

using IFRS. However, the accounting profession faces many

challenges in establishing these standards, such as developing a

sound conceptual framework, use of fair value measurements,

proper consolidation of financial results, off-balance-sheet financing,

and proper accounting for leases and pensions. This chapter

discusses the international financial reporting environment and the

many factors affecting it, as follows.

Continuing Evolution of International Financial Reporting

The age of international trade and the interdependence of national

economies continue to evolve. Many of the largest companies in the

world often do more of their business in foreign lands than in their

home countries. Companies now access not only their home country

capital markets for financing, but others as well. With this globalization,

companies are recognizing the need to have one set of financial

reporting standards. For globalization of capital markets to be efficient,

what is reported for a transaction in Beijing should be reported the same

way in Paris, New York, or London.

In the past, many countries used their own sets of accounting standards

or followed standards set by larger countries, such as those used in

Europe or in the United States. That protocol has changed through the

adoption of a single set of rules, called International Financial Reporting

Standards (IFRS). As indicated in the following chart, there is broad

acceptance of IFRS around the world.

As indicated, 126 jurisdictions require the use of IFRS by all or most

public companies, with most of the remaining jurisdictions permitting

their use. Indeed, 27,000 of the 49,000 companies listed on the 88

largest securities exchanges in the world use IFRS. IFRS also has appeal

for non-public companies; since its publication, the IFRS for SMEs

(small and medium-sized entities) is required or permitted in 57

percent, or 85 of 150, profiled jurisdictions, while a further 11

jurisdictions are also considering adopting IFRS.

Changing to IFRS does not come without cost and effort. However,

academic research and studies by adopting jurisdictions provide

overwhelming evidence that the use of IFRS has brought the following

net benefits to capital markets:

IFRS was successful in creating a common accounting language for

capital markets (European Commission, 2015).

Evidence suggests that IFRS adoption was largely positive for listed

companies in Australia (Australian Accounting Standards Board,

2016).

IFRS adoption helped to reduce investment risk in domestic firms,

mitigate the “Korea discount,” and attract foreign capital via

overseas shares listing, bond issuance, or mergers and acquisitions

(Korean Accounting Standards Board, 2016).

Some companies also report benefits from being able to use IFRS in

their internal reporting. This improves their ability to compare operating

units in different jurisdictions by reducing the number of different

reporting systems. In Japan, where use of IFRS has been voluntary since

2010, business efficiency, enhanced comparability, and better

communications with international investors have been identified as the

main reasons why many Japanese companies made the choice to adopt

IFRS (Japanese Financial Services Agency). Thus, the international

financial reporting environment has and is continuing to evolve. With

these changes, it is hoped that a more effective system of reporting will

develop, which will benefit all.

Review and Practice

Go to the Review and Practice section at the end of the chapter for

a targeted summary review and practice problem with solution.

Multiple-choice questions with annotated solutions, as well as

additional exercises and practice problem with solutions, are also

available online.

Global Markets

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 1

Describe the global financial markets and their relation to financial

reporting.

World markets are increasingly intertwined. International consumers

drive Japanese cars, wear Italian shoes and Scottish woolens, drink

Brazilian coffee and Indian tea, eat Swiss chocolate bars, sit on Danish

furniture, watch U.S. movies, and use Arabian oil. The tremendous

variety and volume of both exported and imported goods indicates the

extensive involvement in international trade—for many companies, the

world is their market.

To provide some indication of the extent of globalization of economic

activity, Illustration 1.1 provides a listing of the top 20 global

companies in terms of sales.

Rank

Company

Country

Revenues ($

millions)

1 Walmart

U.S.

5,00,343

2 State Grid

China

3,48,903

3 Sinopec Group

China

3,26,953

4 China National

Petroleum

China

3,26,008

5 Royal Dutch Shell

Netherlands

3,11,870

6 Toyota Motor

Japan

2,65,172

7 Volkswagen

Germany

2,60,028

8 BP

Britain

2,44,582

9 ExxonMobil

U.S.

2,44,363

10 Berkshire Hathaway

U.S.

2,42,137

11 Apple

U.S.

2,29,234

12 Samsung Electronics

South

Korea

2,11,940

13 McKesson

U.S.

2,08,357

14 Glencore

Switzerland

2,05,476

15 UnitedHealth Group

U.S.

2,01,159

16 Daimler

Germany

1,85,235

17 CVS Health

U.S.

1,84,765

18 Amazon.com

U.S.

1,77,866

19 EXOR Group

Italy

1,61,677

20 AT&T

U.S.

1,60,546

ILLUSTRATION 1.1 Top 20 Global Companies in Terms of

Sales

Source: Data from Global Fortune 500, 2018.

www.fortune.com/global500/2018/search/?revenues=desc.

In addition, due to technological advances and less onerous regulatory

requirements, investors are able to engage in financial transactions

across national borders and to make investment, capital allocation, and

financing decisions involving many foreign companies. Also, many

investors, in attempts to diversify their portfolio risk, have invested

more heavily in international markets. As a result, an increasing number

of investors are holding securities of foreign companies. For example,

over a recent seven-year period, estimated investments in foreign equity

securities by U.S. investors doubled, from $3,422 billion to $7,844

billion (OECD, 2018).

An indication of the significance of these international investment

opportunities can be found when examining the number of foreign

registrations on various securities exchanges. As shown in Illustration

1.2, a significant number of foreign companies are found on national

exchanges.

As indicated, capital markets are increasingly integrated and companies

have greater flexibility in deciding where to raise capital. In the absence

of market integration, there can be company-specific factors that make it

cheaper to raise capital and list/trade securities in one location versus

another. With the integration of capital markets, the automatic linkage

between the location of the company and the location of the capital

market is loosening. As a result, companies have expanded choices of

where to raise capital, either equity or debt. The move toward adoption

of global accounting standards has and will continue to facilitate this

trend.

Exchange

NYSE

Market

Capitalization Total Domestic Foreign Foreign

($ millions) Listings Listings Listings

%

2,42,30,840

2,335

1,832

503

21.5

1,16,58,201

3,080

2,637

443

14.4

Japan

Exchange

Group

56,14,217

3,677

3,672

5

0.1

Euronext

44,18,229

1,239

1,087

152

12.3

Hong Kong

Exchanges

and Clearing

41,89,279

2,382

2,218

164

6.9

LSE Group

39,34,491

2,450

2,049

401

16.4

TMX Group

22,86,818

3,408

3,354

54

1.6

National

Stock

Exchange of

India Limited

21,83,847

1,945

1,944

1

0.1

Deutsche

Boerse AG

19,49,134

519

469

50

9.6

SIX Swiss

Exchange

17,11,019

274

240

34

12.4

Nasdaq

Nordic and

Baltics

14,84,297

1,029

986

43

4.2

ASX

Australian

Securities

Exchange

14,54,171

2,124

1,983

141

6.6

Korea

Exchange

14,32,601

2,221

2,200

21

0.9

Taiwan Stock

Exchange

10,46,389

948

858

90

9.5

Nasdaq

Exchange

Market

Capitalization Total Domestic Foreign Foreign

($ millions) Listings Listings Listings

%

B3 (Brasil

Bolsa Balcão)

10,45,210

330

325

5

1.5

Johannesburg

Stock

Exchange

9,77,496

349

280

69

19.8

BME Spanish

Exchanges

7,74,947

2,937

2,910

27

0.9

Singapore

Exchange

7,25,887

738

478

260

35.2

ILLUSTRATION 1.2 International Exchange Statistics

Source: Data from Market Statistics-October 2019, The WFE Statistics Team.

The World Federation of Exchanges.

Financial Statements and Financial Reporting

Accounting is the universal language of business. One noted economist

and politician indicated that the single most important innovation

shaping capital markets was the development of sound accounting

principles. The essential characteristics of accounting are (1) the

identification, measurement, and communication of financial

information about (2) economic entities to (3) interested parties.

Financial accounting is the process that culminates in the

preparation of financial reports on the enterprise for use by both

internal and external parties. Users of these financial reports include

investors, creditors, managers, unions, and government agencies. In

contrast, managerial accounting is the process of identifying,

measuring, analyzing, and communicating financial information needed

by management to plan, control, and evaluate a company’s operations.

Financial statements are the principal means through which a company

communicates its financial information to those outside the business.

These statements provide a company’s history quantified in money

terms. The financial statements most frequently provided are (1) the

statement of financial position, (2) the income statement (or statement

of comprehensive income), (3) the statement of cash flows, and (4) the

statement of changes in equity. Note disclosures are an integral part of

each financial statement.

Some financial information is better provided, or can be provided only,

by means of financial reporting other than formal financial

statements. Examples include the president’s letter or supplementary

schedules in the company annual report, prospectuses, reports filed with

government agencies, news releases, management’s forecasts, and social

or environmental impact statements. Companies may need to provide

such information because of authoritative pronouncements and

regulatory rules, or custom. Or, they may supply it because management

wishes to disclose it voluntarily.

In this textbook, we focus on the development of two types of financial

information: (1) the basic financial statements and (2) related

disclosures.

Accounting and Capital Allocation

Resources are limited. As a result, people try to conserve them and

ensure that they are used effectively. Efficient use of resources often

determines whether a business thrives. This fact places a substantial

burden on the accounting profession.

Accountants must measure performance accurately and fairly on a

timely basis, so that the right managers and companies are able to

attract investment capital. For example, relevant financial information

that faithfully represents financial results allows investors and creditors

to compare the income and assets employed by such companies as

Nokia (FIN), McDonald’s (USA), Air China Ltd. (CHN), and Toyota

Motor Company (JPN). Because these users can assess the relative

return and risks associated with investment opportunities, they channel

resources more effectively. Illustration 1.3 shows how this process of

capital allocation works.

ILLUSTRATION 1.3 Capital Allocation Process

An effective process of capital allocation is critical to a healthy economy.

It promotes productivity, encourages innovation, and provides an

efficient and liquid market for buying and selling securities and

obtaining and granting credit. Unreliable and irrelevant information

leads to poor capital allocation, which adversely affects the securities

markets.

High-Quality Standards

To facilitate efficient capital allocation, investors need relevant

information and a faithful representation of that information to enable

them to make comparisons across borders. For example, assume that

you were interested in investing in the telecommunications industry.

Four of the largest telecommunications companies in the world are

Nippon Telegraph and Telephone (JPN), Deutsche Telekom

(DEU), Telefonica (ESP and PRT), and AT&T (USA). How do you

decide in which of these telecommunications companies to invest, if

any? How do you compare, for example, a Japanese company like

Nippon Telegraph and Telephone with a German company like Deutsche

Telekom?

A single, widely accepted set of high-quality accounting standards is a

necessity to ensure adequate comparability. Investors are able to make

better investment decisions if they receive financial information from

Nippon Telegraph and Telephone that is comparable to information

from Deutsche Telekom. Globalization demands a single set of highquality international accounting standards. But how is this to be

achieved? Here are some elements:

1. Single set of high-quality accounting standards established by a

single standard-setting body.

2. Consistency in application and interpretation.

3. Common disclosures.

4. Common high-quality auditing standards and practices.

5. Common approach to regulatory review and enforcement.

6. Education and training of market participants.

7. Common delivery systems (e.g., eXtensible Business Reporting

Language—XBRL).

8. Common approach to company governance and legal frameworks

around the world.1

Fortunately, as indicated in the opening story, significant changes in the

financial reporting environment are taking place, which hopefully will

lead to a single, widely accepted set of high-quality accounting

standards. The major standard-setters of the world, coupled with

regulatory authorities, now recognize that capital formation and investor

understanding are enhanced if a single set of high-quality accounting

standards is developed.

Objective of Financial Reporting

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 2

Explain the objective of financial reporting.

What is the objective (or purpose) of financial reporting? The

objective of general-purpose financial reporting is to provide financial

information about the reporting entity that is useful to present

and potential equity investors, lenders, and other creditors in

making decisions about providing resources to the entity. Those

decisions involve buying, selling, or holding equity and debt

instruments, and providing or settling loans and other forms of credit.

[1] (See the Authoritative Literature References section near the end of

the chapter.) Information that is decision-useful to capital providers

(investors) may also be useful to other users of financial reporting who

are not investors. Let’s examine each of the elements of this objective.

General-Purpose Financial Statements

General-purpose financial statements provide financial reporting

information to a wide variety of users. For example, when Nestlé (CHE)

issues its financial statements, these statements help shareholders,

creditors, suppliers, employees, and regulators to better understand its

financial position and related performance. Nestlé’s users need this type

of information to make effective decisions. To be cost-effective in

providing this information, general-purpose financial statements are

most appropriate. In other words, general-purpose financial statements

provide, at the least cost, the most useful information possible.

Equity Investors and Creditors

The objective of financial reporting identifies investors and creditors as

the primary user group for general-purpose financial statements.

Identifying investors and creditors as the primary user group provides

an important focus of general-purpose financial reporting. For example,

when Nestlé issues its financial statements, its primary focus is on

investors and creditors because they have the most critical and

immediate need for information in financial reports. Investors and

creditors need this financial information to assess Nestlé’s ability to

generate net cash inflows and to understand management’s ability to

protect and enhance the assets of the company, which will be used to

generate future net cash inflows. As a result, the primary user groups

are not management, regulators, or some other non-investor group.

What Do the Numbers Mean?

Don’t Forget Management Stewardship

In addition to providing decision-useful information about future

cash flows, management also is accountable to investors for the

custody and safekeeping of the company’s economic resources and

for their efficient and profitable use. For example, the management

of Nestlé has the responsibility of protecting its economic resources

from unfavorable effects of economic factors, such as price changes,

and technological and social changes. Because Nestlé’s performance

in discharging its responsibilities (referred to as its stewardship

responsibilities) usually affects its ability to generate net cash

inflows, financial reporting may also provide decision-useful

information to assess management performance in this role. [2]

Entity Perspective

As part of the objective of general-purpose financial reporting, an entity

perspective is adopted. Companies are viewed as separate and distinct

from their owners (present shareholders) using this perspective. The

assets of Nestlé are viewed as assets of the company and not of a specific

creditor or shareholder. Rather, these investors have claims on Nestlé’s

assets in the form of liability or equity claims. The entity perspective is

consistent with the present business environment, where most

companies engaged in financial reporting have substance distinct from

their investors (both shareholders and creditors). Thus, the perspective

that financial reporting should be focused only on the needs of

shareholders—often referred to as the proprietary perspective—is not

considered appropriate.

Decision-Usefulness

Investors are interested in financial reporting because it provides

information that is useful for making decisions (referred to as the

decision-usefulness approach). As indicated earlier, when making

these decisions, investors are interested in assessing (1) the company’s

ability to generate net cash inflows and (2) management’s ability to

protect and enhance the capital providers’ investments. Financial

reporting should therefore help investors assess the amounts, timing,

and uncertainty of prospective cash inflows from dividends or interest,

and the proceeds from the sale, redemption, or maturity of securities or

loans. In order for investors to make these assessments, the economic

resources of an enterprise, the claims to those resources, and the

changes in them must be understood. Financial statements and related

explanations should be a primary source for determining this

information.

The emphasis on “assessing cash flow prospects” does not mean that the

cash basis is preferred over the accrual basis of accounting. Information

based on accrual accounting generally indicates more accurately a

company’s present and continuing ability to generate favorable cash

flows than does information limited to the financial effects of cash

receipts and payments.

Recall from your first accounting course the objective of accrual-basis

accounting: it ensures that a company records events that change its

financial statements in the periods in which the events occur, rather

than only in the periods in which it receives or pays cash. Using the

accrual basis to determine net income means that a company recognizes

revenues when it provides the goods or performs the services (that is,

satisfies its performance obligation) rather than when it receives cash.

Similarly, it recognizes expenses when it incurs them rather than when

it pays them. Under accrual accounting, a company generally recognizes

revenues when it makes sales or performs services. The company can

then relate the revenues to the economic environment of the period in

which they occurred. Over the long run, trends in revenues and expenses

are generally more meaningful than trends in cash receipts and

disbursements.2

Standard-Setting Organizations

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 3

Identify the major policy-setting bodies and their role in the

standard-setting process.

For many years, many nations have relied on their own standard-setting

organizations. For example, Canada has the Accounting Standards

Board, Japan has the Accounting Standards Board of Japan, Germany

has the German Accounting Standards Committee, and the United

States has the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). The

standards issued by these organizations are sometimes principles-based,

rules-based, tax-oriented, or business-based. In other words, they often

differ in concept and objective.

The main international standard-setting organization is based in

London, England, and is called the International Accounting

Standards Board (IASB). The IASB issues International Financial

Reporting Standards (IFRS), which are used on most foreign

exchanges. As indicated earlier, IFRS is presently used or permitted in

over 149 jurisdictions (similar to countries) and is rapidly gaining

acceptance in other jurisdictions as well.

IFRS has the best potential to provide a common platform on which

companies can report, resulting in financial statements investors can

use to compare financial information. As a result, our discussion focuses

on IFRS and the organization involved in developing these standards—

the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). The two

organizations that have a role in international standard-setting are the

International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO)

and the IASB.

International Organization of Securities Commissions

(IOSCO)

The International Organization of Securities Commissions

(IOSCO) is an association of organizations that regulate the world’s

securities and futures markets. Members are generally the main

financial regulator for a given country. IOSCO does not set accounting

standards. Instead, this organization is dedicated to ensuring that the

global markets can operate in an efficient and effective basis. The

member agencies (such as from France, Germany, New Zealand, and the

United States) have resolved to:

Cooperate to promote high standards of regulation in order to

maintain just, efficient, and sound markets.

Exchange information on their respective experiences in order to

promote the development of domestic markets.

Unite their efforts to establish standards and an effective

surveillance of international securities transactions.

Provide mutual assistance to promote the integrity of the markets

by a rigorous application of the standards and by effective

enforcement against offenses.

IOSCO supports the development and use of IFRS as the single set of

high-quality international standards in cross-border offerings and

listings. It recommends that its members allow multinational issuers to

use IFRS in cross-border offerings and listings, as supplemented by

reconciliation, disclosure, and interpretation where necessary to address

outstanding substantive issues at a national or regional level. (For more

information, go to the IOSCO website.)

What Do the Numbers Mean?

What About the Little Guy?

As discussed in the opening story, IFRS has gained acceptance,

especially for publicly traded companies that wish to access

international capital markets. What about non-public companies?

Well, IFRS has a financial reporting answer for these “SMEs” (small

and medium-sized entities).

The 250-page IFRS for SMEs focuses on the information needs of

lenders, creditors, and other users of SME financial statements, who

are primarily interested in information about cash flows, liquidity,

and solvency. It also takes into account the costs to SMEs and the

capabilities of SMEs to prepare financial information. While based

on the full-IFRS principles, the IFRS for SMEs is considerably less

complex. It reflects five types of simplifications from full IFRS:

1. Some full-IFRS topics are omitted because they are not relevant

to typical SMEs.

2. Some full-IFRS accounting policy options are not allowed

because a more simplified method is available to SMEs.

3. Many of the full-IFRS recognition and measurement principles

have been simplified.

4. Substantially fewer disclosures are required.

5. The full-IFRS text has been redrafted in “plain English” for

increased understandability and translation.

To date, 85 of the 150 jurisdictions whose profiles are followed by

the IASB require or permit the IFRS for SMEs. It is also currently

under consideration in a further 11 jurisdictions. So IFRS is gaining

traction with both public and non-public companies.

International Accounting Standards Board (IASB)

The standard-setting structure internationally is composed of the

following four organizations:

1. The IFRS Foundation provides oversight to the IASB, IFRS

Advisory Council, and IFRS Interpretations Committee. In this role,

it appoints members, reviews effectiveness, and helps in the

fundraising efforts for these organizations.

2. The International Accounting Standards Board (IASB)

develops, in the public interest, a single set of high-quality,

enforceable, and global international financial reporting standards

for general-purpose financial statements.3