Quality Management for Organizational Excellence Intro to Total Quality ( PDFDrive )

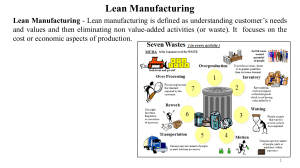

advertisement