Eating Disorders: Practice Parameter for Children & Adolescents

advertisement

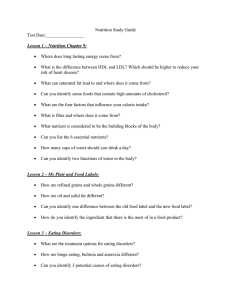

Practice Parameter Eating Disorders JAACAP 2015 Aims • Reviews evidence-based practices for evaluation and treatment of eating disorders in children and adolescents • Includes adult studies • Specifically: anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), bingeeating disorder (BED), and avoidant-restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) • Not: feeding problems in infancy, pica, rumination, purging, obesity Methods • Pubmed, Cochrane, and PsycINFO keyword search 1985-2011 • Book chapters and their bibliographies • Colleague-recommended source materials • English-only • 91 publications from search + 19 recent (2012-13) publications Anorexia nervosa: presentation and course • 2 subtypes: restricting type and binge-purge type • As of DSM-5, amenorrhea is no longer required • Level of severity (mild to extreme) based on age and gender norms according to BMI %iles (usually < 10 %ile) • In children and adolescents, self-report is unreliable due to lack of insight and underdeveloped ability to verbalize abstract thoughts • Need to focus on observed behaviors (often from parent report) • Restricting type more common than binge-purge • Death is most often secondary to complications of starvation (50%) or suicide (50%) Anorexia nervosa: epidemiology, etiology, and risk factors • In US, 0.3-0.7% prevalence in teenage girls, with increasing incidence through 20th century • Less certainty about prevalence among males • Peak incidence ages 14-18 • 30-75% heritability (increases post-puberty) • Temperament and personality risks: perfectionistic, cognitive rigidity • Ballet, gymnastics, wrestling, modeling • “Westernization:” increasing emphasis on a thin ideal has increased rates of AN worldwide Anorexia nervosa: DDx and comorbidity • DDx: ARFID, chronic infection, thyroid disease, Addison’s disease, IBD, connective tissue disorders, CF, PUD, celiac, other GI disease, DM, malignancy • 55.2% comorbidity with at least one other psychiatric illness • Lots of overlap with OCD • Anxiety disorders usually present before and persist longer Bulimia nervosa: presentation and course • • • • • • • • Severity based on frequency of compensatory behaviors Often normal or high normal weight for age Accompanied by internalizing problems (secrecy, shame, guilt) M>F: overexercise and steroid use Lack of control may be a better marker than amount of calories consumed Again, rely on reported behaviors rather than self-report Fluctuating course 5-10 years after treatment, 50% are symptom-free, 50% continue to exhibit symptoms Bulimia nervosa: epidemiology, etiology, and risk factors • Increasing in urban areas and in Westernizing countries • 1-2% adolescent females and 0.5% adolescent males • 1:10 to 1:3 male-to-female ratio • BN rarely diagnoses in children and adolescents, but older patients pinpoint adolescent onset • 60-83% heritability • Trauma, impulsive traits, perfectionism • Wrestling, gymnastics, diving, and long-distance running • Homosexuality > heterosexuality Bulimia nervosa: DDx and comorbidity • DDx: other eating disorders, MDD, CNS tumors, Kleine-Levin syndrome, Kluber-Bucy syndrome, and GI pathologies • 88% psychiatric comorbidity rate: mood disorders, anxiety, substance use disorders, and personality disorders, suicidal ideation and behaviors Binge eating disorder • Episodes need to occur at least once a week for at least 3 months • Though in children and adolescents, a lower frequency threshold can be considered, since younger patients may not have independent access to food • May be the most common: 2.3% female adolescents and 2.6% males • Typical onset in late adolescence or early adulthood • DDx: night eating syndrome, nocturnal sleep-related eating disorder, CNS tumors, Kleine-Levin syndrome, Kluver-Bucy syndrome, PraderWilli, and GI pathology • Comorbidities: depression, anxiety, PTSD, impulse control disorders, substance use disorders, and personality disorders ARFID • Presenting concerns include highly selective eating, neophobia (fear of new things), sensory issues, fear of swallowing or choking, specific fear-triggering events, and general lack of interest in eating or low appetite • Epidemiology unknown • Risk factors: comorbid autism, anxiety, depression, neglect, abuse, developmental delays • DDx: AN Other categories • “Other specified feeding or eating disorders” • Atypical AN, purging disorder, night eating syndrome • “Unspecified feeding and eating disorder” when clinician does not specify the reason the patient fails to meet criteria for a more specific diagnosis • Female triad syndrome: • Low dietary energy availability, amenorrhea, and low bone density Practice Parameter levels of evidence • Clinical Standard (CS). Rigorous empirical evidence • Clinical Guideline (CG). Strong empirical evidence (fewer metaanalyses and systematic reviews) • Clinical Option (CO). Emerging evidence lacking strong evidence or consensus • Not Endorsed (NE). Known to be ineffective or contraindicated. 1: Screen everyone (CS) • Preteens and adolescents should be asked about eating patterns and body dissatisfaction, and growth should be monitored • Screening instruments: EDE-Q, EDI, EAT, KEDS, ChEDE-Q, EDI-C, CHEAT 2: Positive screen -> further evaluation and workup (CS) • Diagnostic evaluation including diet history (registered dieticians may be helpful) and other ED behaviors (weight and label checking), metrics (percentage of weight loss, rate of weight loss), psychiatric and medical comorbidities, and collateral information from caretakers • Eating Disorder Examination: valid 12 years and up; child version available • EDE-Q: self-reported questionnaire, reliable in adolescents • Labs: CBC, BMP, transaminases, TSH, Ca, Mg, Phos, protein, albumin, ESR, amylase, B12, lipids, FSH, estradiol, pregnancy test • Other workup: EKG, DEXA (with amenorrhea lasting >6 months, and all males with rapid weight loss) 3: Treat severe medical complications (CS) • Most reversible over time with adequate diet and restoration • Possible exceptions: growth impairment, decreased bone density, structural brain changes, infertility • Admitted patients should be monitored for refeeding syndrome • Look out for parotid swelling, dorsal hand callouses (Russell’s sign), dental enamel erosion, fluid and electrolyte disturbances, orthostatic hypotension and syncope, esophageal tears, gastric rupture • Clinical need for NG feeding not substantiated 4: Inpatient programs should be considered only when outpatient interventions have been unsuccessful or are unavailable (CG) • No evidence that hospitalization is more effective than outpatient treatment • No comparisons between residential and partial programs • When clinical necessity for inpatient emerges, recommendations for short length of stay, using lowest level of care, involvement of family in programming, and using experienced staff 5: Involve a multidisciplinary team (CS) • Psychotherapist, pediatrician, dietician, child psychiatrist (may be dual therapist-med provider) • Nutritional counseling is not recommended as a sole treatment 6: Outpatient psychosocial interventions are first-line (CS) • AN: Family-based therapy is superior to individual therapies, though individual therapies can be offered and are effective when FBT is unavailable • BN: Limited studies show mixed results comparing CBT and FBT; FBT again superior to individual therapies • BED: adult studies demonstrate that CBT, IPT, and DBT are effective • Too few studies in adolescents • ARFID: no studies; still, start with behavior plans, CBT, and family interventions 7: Reserve medications for comorbid conditions and refractory cases (CG) • AN: adult studies of pharmacotherapy (SSRIs, atypical antipsychotics) have not been encouraging • No adolescent studies • BN: some promise for antidepressants (fluoxetine at higher doses) in adults in reducing binge/purge urges • CBT superior to meds • Combination best in the case of BN + depression • Starved patients have lower available serotonin; SSRI effectiveness is limited Table 1 Fin Thank you!