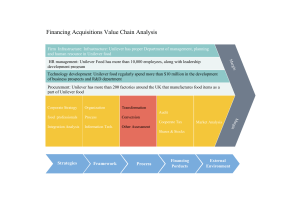

The hair of the dog that bit you: successful market strategies in post-crisis South-East Asia Usha C.V. Haley Associate Professor, Department of Management, Stokely Management Center, University of Tennessee-Knoxville, USA Keywords Multinationals, Local economy, Marketing strategy, Market entry, South-East Asia Introduction South-East Asia, comprising the ten members of the Association of South-East Abstract Nations (ASEAN) ± Brunei, Cambodia, In the wake of post-crisis SouthIndonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, East Asia's declining growth and declining per capita income, local Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam ± appears to be recovering after the companies are restructuring their operations and re-evaluating their financial and economic crisis that engulfed strategies along with the region in 1997 (The Economist, 2000a). The multinational companies (MNCs). hardest-hit countries are demonstrating This article explores the winning some recovery: in 1999, Malaysia, Thailand market-expansion strategies of two companies in South-East and the Philippines exhibited moderate Asia's changed business growth at 5.4 percent, 4.0 percent and 3.2 environments ± the MNC, Unilever percent, respectively. In 1999, Indonesia's in Indonesia; and the local growth performance at 0.23 percent also company, Asia Commercial Bank (ACB) in Vietnam. The first section appeared positive but slow (Asian identifies how Asian post-crisis Development Bank, 2000). business environments have The South-East Asian economies' changed. The next section recoveries seem tangible but not broadexplores the back-to-basics market strategy followed by the based. Recoveries in the financial markets foreign MNC, Unilever. The have preceded recoveries in the real sector. ensuing section sketches the Also, in early 2000, per capita incomes have deliberate strategy of normal yet to return to their pre-crisis days in operations and transparency followed by the local ACB in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam. Based on these case Thailand. When comparing per capita studies, the final section makes some recommendations for MNCs income levels in local constant prices with pre-crisis levels, for all countries, except and local companies considering market-expansion in post-crisis Thailand, 1977 provided the most recent peak Asia. in gross domestic product (GDP) per capita incomes. In Thailand, 1996 provided the peak. The Philippines has the shortest way to go and may regain or exceed its previous peak by the end of 2000. Malaysia may take another two years and Indonesia and Thailand may take even longer (Asian Development Bank, 2000). For all the ASEAN countries, GDP per capita seems well below what would have been achieved if growth had continued unabated. Given the changes in market conditions, local companies are restructuring their operations and reevaluating their strategies Marketing Intelligence & Planning 18/5 [2000] 236±246 # MCB University Press [ISSN 0263-4503] [ 236 ] The research register for this journal is available at http://www.mcbup.com/research_registers/mkt.asp along with multinational companies (MNCs) (Haley, 2000a). For example, Indonesia, once home to more than 240 banks, will probably retain fewer than five. The Philippines lost a national airline; now the country is struggling to resuscitate it. Yet, increased market openness and other structural and regulatory changes in the wake of the crisis have created a new set of opportunities for companies. This article analyzes some of the strategies espoused by companies that appear to be following successful marketexpansion strategies in the new South-East Asia's economic, social and political environments; it also proposes some reasons for these successful strategies. The first section identifies how South-East Asian post-crisis business environments have changed. The next section explores the back-to-basics market-expansion strategy followed by the foreign MNC, Unilever. The ensuing section sketches the deliberate strategy of normal operations and transparency followed by the local ACB in Vietnam. Based on these case studies, the final section makes some recommendations for MNCs and local companies operating in post-crisis South-East Asia. Forces that change markets The countries of South-East Asia, with a population of 500 million and a combined GDP of US$700 billion (The Economist, 2000a), have extremely diverse political systems and markets (Haley, 2000b). Table I indicates the GDP and population of the ASEAN economies. Its largely young population, with large numbers of well-educated and hardworking people, helped to make SouthEast Asia one of the fastest growing regions in the world. Yet recent environmental The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at http://www.emerald-library.com Usha C.V. Haley The hair of the dog that bit you: successful market strategies in post-crisis South-East Asia Marketing Intelligence & Planning 18/5 [2000] 236±246 Table I GDP per head in South-East Asia for 1999 Country Brunei Cambodia Indonesia Laos Malaysia Myanmar Philippines Singapore Thailand Vietnam Population, million GDP per head, US$ 0.3 11.4 209.3 5.0 21.9 45.1 74.5 3.5 60.8 78.7 16,168 252 747 258 3,730 85 1,010 25,500 2,040 350 Source: Economist Intelligence Unit changes have forced MNCs operating in South-East Asia to re-examine their markets. The stark revelation of rampant corruption, collusion and nepotism (korupsi, kolusi and nepotisme in Bahasa Malay or the now widely-accepted South-East Asian lexicon, KKN), are forcing re-evaluations of not just authoritarian governments but also companies that collude with them. Backman (1999) argued that the damage wrought on each Asian country appeared in direct proportion to the amount of cronyism and corruption, the paucity of the legal structures and corporate accountability, and the general lack of ethics. Table II indicates the results of a 1998 survey that ranked 85 countries on corruption ± Indonesia and Vietnam ranked among the lowest. Another survey conducted in 1999 by the Political and Economic Risk Consultancy (PERC) in Singapore on Table II Perceptions of corruption in Asia, survey released September 1998 Country Rank (of 85 countries) Score (10 = very clean, 0 = very corrupt) 80 29 55 7 61 74 2.0 5.3 3.3 9.1 3.0 2.5 11 52 16 66 25 4 71 43 29 8.7 3.5 7.8 2.9 5.8 9.4 2.7 4.2 5.3 ASEAN Indonesia Malaysia Philippines Singapore Thailand Vietnam Other Australia China Hong Kong India Japan New Zealand Pakistan South Korea Taiwan Source: Transparency International corruption and transparency of 800 regional businessmen (on a scale where 0 = best and 10 = worst) revealed that they perceived Indonesia as the most corrupt country in ASEAN (corruption = 9.91, transparency = 8.00); and, Vietnam as the least transparent country in ASEAN (corruption = 8.50; transparency = 9.50). Intermediate countries included Malaysia (corruption = 7.50; transparency = 6.50), Philippines (corruption = 6.71; transparency = 6.29), Singapore (corruption = 1.55; transparency = 4.55). and Thailand (corruption = 7.57, transparency = 7.29). Recent growth figures (outlined in the introduction) indicate that the decade of despondency that many predicted seems unlikely to materialize; but, business as usual is not occurring. The Asian crisis seems to have irrevocably altered South-East Asian markets for companies. Mr Goh Chok Tong, the Prime Minister of Singapore, has argued that the Asian crisis: speeded up the opening of the Asian economies, forced Asians to acknowledge good corporate governance, made the region concentrate on its real competitive strengths and provided a hard lesson about globalization (The Economist, 2000b). Although Goh did not elaborate on it, the crisis is also forcing a withdrawal of governments (including Singapore's) from key economic sectors such as finance, insurance, banking and telecommunications (Haley, 2000b). These changes in business environments have drawn corresponding changes in companies' strategies. An Andersen Consulting survey of more than 70 MNCs operating in Asia found that the financial crisis has ``shifted the shoreline'' of market dynamics in the region, prompting companies to revamp their business strategies and to pursue aggressively opportunities for expansion in new markets (Burrell, 1999). For MNCs, the Asian markets' new strategic dynamics identified in the Anderson Consulting survey (Burrell, 1999) included: building market share while competitors were weak; rationalizing to diversify local market risks and to build critical mass; exploiting market liberalization and foreign investment rules; and adopting new technologies to gain competitive advantages and to create more efficient production and distribution networks. In the wake of financial reforms brought about by gross mismanagement and corruption (Haley, 2000c), some local companies are also parlaying their transparency in operations as a managerial technology to garner legitimacy and [ 237 ] Usha C.V. Haley The hair of the dog that bit you: successful market strategies in post-crisis South-East Asia Marketing Intelligence & Planning 18/5 [2000] 236±246 symbolic as well as substantive benefits from stakeholders. The next two sections explore the winning strategies of two companies in South-East Asia's changed environment ± the MNC, Unilever, in Indonesia; and the local Asia Commercial Bank (ACB) in Vietnam. Unilever in Indonesia The sprawling archipelago of Indonesia, home to 203.7 million, mostly Muslim people, probably suffered the most from the region's financial crisis. Both foreigners and locals perceive the country as extremely corrupt, and reeking of cronyism (see Table I). In 1998, the economy contracted by nearly 14 percent and inflation at one point soared to more than 80 percent (Haley, 2000c). Figure 1 indicates some key market data for Indonesia. In Indonesia, the urban middle class appears badly hurt by the crisis and riots have taken place over cooking staples such as oil (see Haley, 2000b). Consequently, Unilever is shifting its sights from urban malls to tinroofed shops such as those lining Mesuji, a small one-lane village in Indonesia, five hours by bus from the nearest city. Tiny sachets of Unilever NV's Sunsilk and Clear shampoos dangle from shops' eaves. At 250 rupiah (3.3 US cents) apiece, Unilever has aimed the single-use packets towards poorer consumers that cannot spend their weekly wages on frill-size bottles. In one open-air stall, a blue-and-yellow bunting advertised Unilever's new, mini-size Lifebuoy soap. The motto, in Indonesian, read: ``With a price you can afford'' (Karp, 1998). Unilever is building market share in Indonesia with its aggressive strategy for inexpensive, miniature products. Unilever's secret: it sells affordable products available everywhere. This strategy has worked for Unilever in rural developing markets such as Africa and India for decades. In implementing this strategy, Unilever is applying lessons from developed markets when economies sink: consumers need to make their purchases in tiny quantities, and distribution networks spring up to sell loose cigarettes or single eggs. In contrast, Unilever's rival, US consumer-goods giant, Procter & Gamble Co. (P&G), has continued to stock the expensive frill-size bottles, even in Mesuji, with adverse results. ``A half-dozen dusty bottles of P&G's Pantene, at 5,000 rupiah each, have been sitting untouched on a back shelf for more than two months'', said shopkeeper Sukaini (McDermott and Warner, 1998). [ 238 ] Unilever started operating in Thailand in 1932 and in India and in the islands that now form Indonesia a year later. The explosion of supermarkets and shopping malls in SouthEast Asia distracted many MNCs including Unilever from their traditional main market, the rural majority. Ralph Kugler, chairman of Unilever Thai Holdings Ltd said: We were all too much focused on that urban middle class. We saw Bangkok and thought the rest of Thailand and Asia was just like it. To really get to Asian consumers, we must leave the cities (McDermott and Warner, 1998). Since the Asian economic crisis hit, Unilever has been getting back to basics. Its aim now includes making high-quality goods affordable to poor people, earning a tiny margin on broad-based sales and building a consumer base that will stay loyal as it grows more affluent. Simultaneously, the company includes modern markets and marketing in its strategic endeavors. East Asia President Andre Van Heemstra, said: We now span 1,000 years of retailing evolution, from global customers like supermarkets to distributors on foot selling a single bar of soap at a time (McDermott and Warner, 1998). Unilever is following a systematic pricecutting strategy in South-East Asia particularly, and Asia generally. For example, to slash packaging costs in Indonesia, Unilever sells Sunsilk shampoo in plastic bags instead of bottles with expensive four-color printing; it has also introduced bulk containers of its Blue Band margarine, Sariwangi tea and Sunlight laundry detergent so customers can buy the amounts they can afford. Similarly, from the Vietnamese Mekong Delta to metropolitan Manila, Unilever has stretched its usually exclusive distribution networks to reach villages like Mesuji, seeking to obviate wholesalers and the commissions they add to products' retail prices. Sleepy villages like Mesuji's, once considered backwaters off the marketing tracks, now offer welcome stability to Unilever. The collapse in Indonesia's economy and currency have sent the nation's average annual per capita income plunging to an estimated US $260 in late 1998 from US $1,000 in late 1997. Yet even as riots rip Jakarta, Mesuji has changed little. Prices have risen, but the village's basic economies have remained roughly the same: people have become poor, but not much poorer than before the crisis; and some people have actually become richer. For example, while gasoline prices have more than doubled since the crisis, farmers get paid in dollars for their harvest. With the rupiah now worth Usha C.V. Haley The hair of the dog that bit you: successful market strategies in post-crisis South-East Asia Marketing Intelligence & Planning 18/5 [2000] 236±246 just a quarter of its value a year ago, those dollars stretch farther for the farmers, increasing their earnings and purchasing power substantially in Mesuji. Unilever's sales have steadily increased in Indonesia since the economic crisis, fueled by an aggressive campaign to expand reach. Unilever's distributor for the district including Mesuji indicated that in the first half of 1998, sales more than doubled from a year ago. Because of raging inflation that in October hit 79 percent, the MNC doubled the price of its premium-brand Lux soap, but per unit sales volume rose for some products as Figure 1 Key market indicators for Indonesia [ 239 ] Usha C.V. Haley The hair of the dog that bit you: successful market strategies in post-crisis South-East Asia Figure 1 Marketing Intelligence & Planning 18/5 [2000] 236±246 well. In July 1998 the distributor delivered 312 cartons a week of Rinso laundry detergent, three times his average from the previous year. He also doubled to 408 the number of small stores, sidewalk stalls and corner shops his sales people covered. Across Indonesia, such independent but exclusive distributors sent national sales manager Hanafiah Djajawinata detailed data from the [ 240 ] 290,000 retail outlets (or half of Indonesia's total outlets) that they visited each week ± four times their range in 1985 and about six times what analysts estimate constitutes the reach of other MNCs such as PepsiCo Inc. and Nestle, SA (McDermott and Warner, 1998). At Unilever's headquarters in Jakarta, Hanafiah could locate every new outlet ± and Usha C.V. Haley The hair of the dog that bit you: successful market strategies in post-crisis South-East Asia Marketing Intelligence & Planning 18/5 [2000] 236±246 every prospective one ± on hundreds of pages of multicolored transparencies held in a set of giant ring binders. The transparencies slipped over a map of the country, with each sheet marking different types of retail outlets; together they accounted for every supermarket and farmer's market in the nation. The sales data fed to headquarters helped Unilever with its difficult logistics task. Distribution became particularly challenging in 1998 as Indonesia's economic crisis spawned riots directed in part against the Chinese minority who control most of the country's logistics and retail industries (Haley et al., 1998). Unilever's 265 mostly Chinese distributors did not escape the riots. Several fled their homes and two saw their warehouses torched. But, unlike other MNCs, Unilever backed their Chinese distributors and retailers. The MNC paid for hotel rooms and lent them money to restock Unilever's products. Consequently, Unilever retained all its distributors in the country, increased their loyalty and dependence on Unilever, and kept their products available for the masses. In South-East Asia, Unilever has extended its strategic model from India, where its subsidiary Hindustan Lever forms one of the country's biggest and best-known MNCs. India includes some of the world's biggest cities, but Unilever approaches the country as one giant rural market. It uses small, cheap packaging, lots of bright signs and numerous distributors driving, cycling and walking through the subcontinent selling Unilever's products (Jordan, 1999). Hindustan Lever makes India's best-selling face lotion ``Fair & Lovely'' so pervasive that men advertise for ``Fair & Lovely'' brides. Hanafiah, Unilever's national sales manager in Indonesia, said: In the past we never looked to India as an example because we thought they were backward. Now India is an inspiration to me (McDermott and Warner, 1998). Unilever's increased market share in Indonesia is proving profitable. Profits at PT Unilever Indonesia, listed on the Jakarta exchange, rose 55 percent in the first half of 1998 on sales growth of 54 percent ± although its rupiah earnings' growth appeared negligible when translated into dollars. However, some signs indicate that Unilever's striving for market share may have reached the point of diminishing returns: for Unilever, each additional new outlet now seems harder to find and to reach and some executives have started worrying about the incremental costs of expansion. Foreign competitors, particularly P&G, also appear at Unilever's heels. ``I'm very worried'' about P&G's own expansion campaign, said Hanafiah. They're not only good now in the supermarkets, but they're getting better in the traditional markets (McDermott and Warner, 1998). P&G's shampoo sells for only 50 rupiah more in Indonesia than Unilever's. Local competitors are also surfacing at the pricing spectrum's lower end. For example, consumers in Mesuji can purchase packets of Tancho, a locally-made powdered shampoo for 50 rupiah each. To compete with the local competitors on price, Unilever shrunk its sachets to six milliliters from seven milliliters. Unilever's strategic evolution in Asia will have to incorporate some of these tradeoffs between price, volume, perceived quality and increased market share. The next section examines a local company's marketexpansion strategy in Vietnam. Asia Commercial Bank in Vietnam Vietnam is among the newest members of ASEAN and one of the few communist states in the world. With a population of 76.5 million mostly young and largely educated people, Vietnam seemed to have escaped the Asian crisis with about 5 percent annual growth. In reality, Doi Moi, or economic renovation, the policy started by the Vietnamese government over a decade ago, appears to have stalled (Haley, 2000d). FDI, seen by the Vietnamese as contributing to its development, has notably dropped off (Haley, 2000d). As the PERC survey revealed, regional businessmen see Vietnam as one of the least transparent countries in the world. Figure 2 indicates some key market data for Vietnam. Banking in Vietnam generally appears opaque. Freewheeling entrepreneurs with little interest in bookkeeping manage the typical Vietnamese bank with private shareholders, or ``joint-stock'' banks. Conversely, communist party members with connections manage most governmentowned banks. Among Vietnam's beleaguered financial institutions, ACB appears an exception: it makes a healthy profit. ACB's secret: it constitutes a relatively transparent company in a country where few exist. Transparent bookkeeping, qualified staff and strict lending policies form innovative ways of doing business in Vietnam. ACB constitutes one of the very few joint-stock banks with a clean bill of health from an independent auditor, Ernst & Young. The bank follows strict guidelines for lending. Its [ 241 ] Usha C.V. Haley The hair of the dog that bit you: successful market strategies in post-crisis South-East Asia Marketing Intelligence & Planning 18/5 [2000] 236±246 management team has financial training and business experience. By contrast, few of the country's 52 joint-stock banks release earnings reports; many hide their shareholders' names. While ACB voluntarily submitted to independent audits since 1995 ± well ahead of foreign shareholders' Figure 2 Key market indicators for Vietnam [ 242 ] involvement at the end of 1996 ± other jointstock banks began audits only in 1998, by government decree. Indeed, ACB, forms one of just two Vietnamese banks to have foreign shareholders. Relative transparency ± standard in most other countries, but nearly nonexistent in Usha C.V. Haley The hair of the dog that bit you: successful market strategies in post-crisis South-East Asia Figure 2 Marketing Intelligence & Planning 18/5 [2000] 236±246 Vietnam ± has earned ACB a flood of praise from the business media and other key external stakeholders. In 1997, an international finance magazine called ACB the best bank in Vietnam and Western Union named it ``agent of the year.'' Even the State Bank of Vietnam labeled ACB the ``safest and most effective'' private bank in the country ± a rare tribute from the central bank to a private institution. With steady profit growth, despite a tough business environment, and with its rivals struggling, this private bank ± less than half the size of Vietnam's state-owned banks ± has the potential to become one of Vietnam's leading financial institutions, according to foreign investors and banking experts. The Mekong Project Development Facility, one of the International Finance Corporation's [ 243 ] Usha C.V. Haley The hair of the dog that bit you: successful market strategies in post-crisis South-East Asia Marketing Intelligence & Planning 18/5 [2000] 236±246 [ 244 ] investing arms, is negotiating long-term lending deals with the bank. ACB constitutes one of very few Vietnamese banks that has the capital base ± the biggest among private banks ± as well as the credit facilities and balance sheet necessary for long-term project financing, according to Thomas Davenport, manager of the Mekong Project (Marshall, 1998). Strict loan guidelines have helped ACB to avoid some financial pitfalls. Loan decisions at many other Vietnamese banks often involve little or no due diligence. As a result, bad debts among private banks hover around 20 percent after the economic crisis. ACB's audited annual report for 1997, revealed only about 4.8 percent of its loans as overdue ± one reason bank rating agency Thomson BankWatch considered ACB one of the best banks in Vietnam. On a peeling wall of ACB's threadbare Hanoi branch, a large bulletin board reminds tellers of the bank's stringent lending rules. Loan applicants must provide financial statements, credit history and properly valued collateral. Often, in Vietnam's private banks, connections to the banks' directors suffice to secure loans. These credit controls severely limit the number of ACB's customers; but, other Vietnamese bankers blame widespread lending to friends and relatives for the unpaid letters of credit plaguing local banks since the crisis (Haley, 2000d). In 1997, by contrast, ACB earned 11 billion dong in international settlement fees, or 23 percent of the bank's profits before taxes. ACB's letters of credit get paid on time as light export manufacturers of sea products and plastics, that generate a steady flow of foreign currency, constitute the majority of ACB's trade finance customers (Marshall, 1998). ACB's net profits are growing, according to the few audits available in this sector. The bank earned 28.9 billion dong ($2.1 million) in net profits for 1997, up 4.7 percent from 27.6 billion dong in 1996. Profits before taxes grew 30 percent to 48.5 billion dong in 1997 from 37.2 billion dong a year earlier, and the bank's shareholders predicted profits before taxes would rise an additional 20 percent to 30 percent in 1998. By contrast, net profits shrank by more than half at Vietnam Export & Import Commercial Joint-Stock Bank (or Eximbank), and by more than a third at Vietnam Maritime Commercial Stock Bank (one of the better joint-stock banks). Even the strongest foreign and foreign-invested banks are just holding steady, and many local banks are selling assets to pay outstanding debts rather than building their businesses. ACB's operations have also drawn praise and investment from key internal stakeholders. In Vietnam's post-crisis financial environment, ACB's profit growth, while small, ``is very impressive,'' said Mark Whitehead, chief representative of Jardine Pacific (Vietnam), one of ACB's shareholders (Marshall, 1998). Jardine holds a 7 percent stake in the bank; LG Group of South Korea and two foreign-investment funds hold the remaining 19 percent of the bank's foreign equity. ACB's transparency primarily attracted Hong Kong-based Jardine. When Lam Ho ang Loc, ACB's director of operations, flew to London for a lunch meeting with Jardine three years ago to solicit investment, Loc was ``very open about bad debt,'' Whitehead recalled. While the bank does not openly espouse transparency as bank policy, Davenport and other foreign investors credit Loc for the bank's honesty. A devout Buddhist, Loc chose people with similar values to work under him (Marshall, 1998). Yet, in churning, government-dominated Vietnam, ACB faces many external uncertainties. The central government has yet to determine how to handle an estimated $137 million in overdue loans at joint-stock banks. A government plan to merge failing joint-stock banks with healthy ones may force ACB to acquire debt-ridden competitors, a move that could reduce its capital ± now at $25.4 million. Internally, ACB's 1997 annual report showed some signs of very rapid expansion in its loan portfolio. In 1997, outstanding loans topped one trillion dong, 62 percent higher than in 1996, suggesting that shortterm loans were turning into longer-term, higher-risk ones. Loans nearly doubled in that year. In 1997, ACB also diversified into loans for state-owned enterprises ± bigger loans to customers notorious for not repaying on time. Yet, net profits from a 74 percent increase in loans in 1997 rose a mere 4.7 percent. Huynh Quang Tuan, ACB's Hanoi branch manager, said: That percentage is not meaningful. Loans rose only $4 million compared with 1996 ± not such a sharp rise, considering the bank opened in 1993 and was building a loan portfolio from scratch. Credit activities, the bank's core business, constituted about 65 percent of its profit before tax in 1997 (Marshall, 1998). With 26 percent of its equity in registered capital ± the cash injected by shareholders ± ACB has better cover than many Western banks. If, for example, all the bank's borrowers defaulted, the bank would have enough capital to write off almost half of them. ACB's foreign shareholders provided this hefty increase in capital early last year, enabling the bank to expand more quickly. Usha C.V. Haley The hair of the dog that bit you: successful market strategies in post-crisis South-East Asia Marketing Intelligence & Planning 18/5 [2000] 236±246 For the next two years, ACB intends to decrease its lending activities. Instead, the bank plans to plow more capital into expanding its services and improving infrastructure. The bank already has become the first Vietnamese member of Visa and Mastercard, and one of Western Union's first Vietnamese agents. It also plans to become one of the first securities companies in Vietnam. Vietnam's much-delayed stock market cannot offer a source of much profit for many years after it opens, but ACB aims to diversify in Vietnam's shallow and undeveloped financial market. ACB also is investing in computerization ± aspiring by 2000 to connect branches electronically in a move that will enable the bank to monitor activities from its head office. It is also increasing staff training on everything from treasury management to securities dealing. Unusual for Vietnam ± 377 out of its 576 employees in 1997 had university and postgraduate degrees. According to Tuan, ``we are only good because we know we are still bad. We are not professional yet'' (Marshall, 1998). The next section analyzes patterns in successful corporate strategies in post-crisis South-East Asia and makes some recommendations. Recommendations This article has extrapolated on two Asian companies' diverse successful strategies in the post-crisis environment. The MNC, Unilever has sought to expand market share through a return-to-basics strategy, followed by other MNCs. For example, ABN Amro Bank, another Dutch giant, recently opened four branches in remote Indonesian provinces but avoided urban areas where other foreign banks were closing branches. Ford Motor Co. is building open-air dealerships in rural Thailand; Ford constructs these dealerships cheaply, and rice and sugar-cane farmers, potential customers who would feel awkward in Bangkok's posh, air-conditioned showrooms, feel comfortable in them. Similarly, for the first time, advertising giant Ogilvy & Mather's Thai office sent senior creative executives into northern provinces to talk to rural consumers about purchasing decisions. The Anderson Consulting survey of more than 70 MNCs (Burrell, 1999) also found that rapid responses appear the key to success for companies seeking to exploit these openings, with major MNCs such as GE Capital, Unilever, British Telecom and Coca-Cola already investing billions of dollars in the region. As Haley et al. (1998) argued, MNCs often freeze when operating under Asian business environments' uncertain conditions; yet, MNCs need to respond quickly to key strategic opportunities to succeed in South-East Asia and the successful MNCs do. Alan Salter, Andersen Consulting's managing partner for strategy in the Asia-Pacific region echoed this observation: Those who recognize the shift in the shoreline and have the boldness to act will find the opportunities are enormous (Burrell, 1999). Consequently, those MNCs that identify in a timely fashion the pent-up demand for affordable consumer goods or transparency will likely score formidable strategic hits in some of the ASEAN countries, especially those that perceive these products as being in short-supply. As the Anderson survey indicated (Burrell, 1999), the toppling of competitors has created new opportunities for MNCs to expand in Asia. Openings exist for MNCs that can act rapidly and make decisions with little information that headquarters' strategists would consider valid. Yet, as Haley et al. (1998) contended, MNCs from developed countries often balk at making strategic decisions with softer information and what they consider insufficient analysis. Clearly the MNCs that do act, such as Unilever, create winning strategies in the new postcrisis environment. In contrast, the local company, ACB, has sought to establish legitimacy and to enhance reputation through adopting transparent policies and more-accepted Western management techniques, including management information systems. Haley (1991) indicated how companies seek to establish legitimacy with key stakeholders through symbolic behaviors. In Asia, legitimacy and professionalization have become key issues for local companies, especially those wishing to attract foreign investors. Michael Backman (1999) called insufficient transparency, the Asian disease ± and successful Asian companies present stakeholders with images of combating that disease. Backman (1999) argued that whenever a single family or network dominates a web of public and private companies, opportunities surface for offbalance-sheet guarantees and asset-shifting, resulting in a loss of confidence from major investors, especially foreign investors. Foreign investors' confidence has become a major point of contention in cash-starved, post-crisis South-East Asia and particularly in Vietnam that eyes FDI as a source of development funds (Haley and Haley, 2000). CP Group of Thailand, one of the most [ 245 ] Usha C.V. Haley The hair of the dog that bit you: successful market strategies in post-crisis South-East Asia Marketing Intelligence & Planning 18/5 [2000] 236±246 successful local, network companies, is suffering from such a loss of foreign investors' confidence with foreign brokerage houses recommending against purchasing its stock, despite CP's new debt-control policies and controlled expansion (Biers et al., 1999). However, without ACB's transparent structure, investors cannot feel comfortable with or gauge the extent of CP's restructuring or reforms. ACB's Tuan hinted in the previous section that transparency and Western-style operations may often fall short of Western standards in Vietnam and other Asian countries; consequently, one can assume that in these countries, their symbolic values for foreign investors may equal or exceed their substantive benefits. Table II indicated perceptions of corruption in various Asian countries: transparency as a means to establish reputation and to assure foreign investors probably symbolically assumes more importance in countries with higher perceived corruption such as Vietnam. Consequently, local companies that follow deliberate strategies to appear professionalized may appeal more to foreign investors in these countries. The countries of South-East Asia suffered a collective blow in the Asian crisis; but their innately different characteristics have generated different recovery rates and paths and should generate different marketexpansion strategies from successful MNCs and local companies. Correctly identifying windows of opportunity and timely strategies for the new markets, could yield significant competitive edges and first-mover advantages for the companies that undertake them. References Asian Development Bank (2000), Asia Recovery Report 2000, Asian Developing Bank Regional Economic Monitoring Unit, Manila, Philippines. Backman, M. (1999), Asian Eclipse: Exposing the Dark Side of Business in Asia, John Wiley, New York, NY. Biers, D., Vatikiotis, M., Tasker, R. and Daorueng, P. (1999), ``Back to school'', Far Eastern Economic Review, April 8. Burrell, S. (1999), ``Asia dances to a new beat'', Sydney Morning Herald, May 28. [ 246 ] Economist (The) (2000a), ``A survey of South-East Asia'', February 12-18. Economist (The) (2000b), ``The tigers that changed their stripes'', in ``A survey of South-east Asia'', February 12-18, pp. 3-4. Haley, G.T., Tan, C.T. and Haley, U.C.V. (1998), New Asian Emperors: The Overseas Chinese, Their Strategies and Competitive Advantages, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford/Boston, MA. Haley, U.C.V. (1991), ``Corporate contributions as managerial masques: reframing corporate contributions as strategies to influence society'', Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 28 No. 5, pp. 485-509. Haley, U.C.V. (2000a), ``Successful strategies in post-crisis Asia'', forthcoming in Richter, F.-J. (Ed.), The Asian Development Model, Macmillan, UK and St Martin's Press, USA. Haley, U.C.V. (Ed.) (2000b), Strategic Management in the Asia Pacific: Harnessing Regional and Organizational Change for Competitive Advantage, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford/ Boston, MA. Haley, U.C.V. (2000c), ``Why the Asia Pacific matters'', Haley, U.C.V. (Ed.), in Strategic Management in the Asia Pacific: Harnessing Regional and Organizational Change for Competitive Advantage, ButterworthHeinemann, Oxford/Boston, MA, pp. 3-13. Haley, U.C.V. (2000d), ``How the Asian crisis has affected Vietnam'', Haley, U.C.V. (Ed.), in Strategic Management in the Asia Pacific: Harnessing Regional and Organizational Change for Competitive Advantage, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford/Boston, MA, pp. 315-6. Haley, U.C.V. and Haley, G.T. (2000), ``When the tourists flew in: strategic implications of foreign direct investment in Vietnam's tourism industry'', Haley, U.C.V. (Ed.), in Strategic Management in the Asia Pacific: Harnessing Regional and Organizational Change for Competitive Advantage, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford/Boston, MA, pp. 298-314. Jordan, M. (1999), ``Indian toothpaste war is fought with a familiar, winning smile'', Wall Street Journal, April 15. Karp, J. (1998), ``Hindustan Lever Ltd'', Wall Street Journal, October 26. Marshall, S. (1998), ``ACB stands out in Vietnam for being a sound bank'', Wall Street Journal, December 4. McDermott, D. and Warner, F. (1998), ``Secret of Unilever's success is affordable, single-use packs'', Wall Street Journal, November 23.