EFL Textbook Cultural Content & Student Attitudes in China

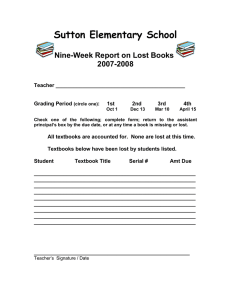

advertisement