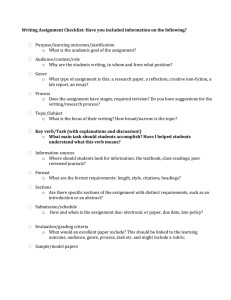

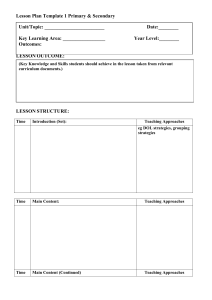

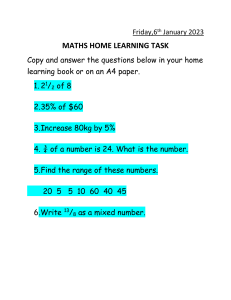

ALMI UoM_DoL_2023 Unit 1 Introduction to Academic Style This lesson focuses on providing you with a foundation for effective written communication in English in your current academic settings by introducing you to ‘academic style’, ‘academic writing’, ‘the writing process’, ‘genres’, and ‘word order and sentence structures’. Intended Learning Outcomes: Upon successful completion of this lesson, the students should be able to: identify academic style and its key characteristics describe how academic style is different from general writing identify the six steps of the academic writing process idenitfy key elements of an academic text apply the word order formula and construct meaningful sentences Lesson 1: What is Academic Style? Producing written work as part of a university exam, essay, dissertation or another form of assignment requires an approach to organization, structure, voice, and use of language that differs from other forms of writing and communication. Academic style is a broad term which encompasses both linguistic and non-linguistic features displayed in writing (also in speech) for an academic community. The term ‘linguistic’ refers to the language used while the term ‘nonlinguistic features’ includes organization, formatting, tone, and point-of view of a piece of writing. This is the style used in academic communities such as universities, colleges, and schools; academic publications such as textbooks, study guides, and research papers; and genres of academic writing such as assignments, reports, and dissertations. Academic style, thereby, is a skill every student should achieve fluency in. Academic writing is the style of writing that no one is born with but can be mastered. Understanding more about the conventions of your discipline and the specific features and conventions of academic writing can help you develop confidence and make improvements to your written work. Academic writing is part of a complex process of finding, analyzing and evaluating information, planning, structuring, editing and proofreading your work, and reflecting on feedback that underpins written assessment at university. On a more important note, undergraduates usually presume that their writing is judged primarily on its grammatical correctness. Ideas, evidence, and arguments matter more than the mechanics of grammar and punctuation; however, many of the rules of formal writing exist to promote clarity and precision which writers much achieve in order to effectively convey ideas, evidence, and arguments. Task 1: Quickly think of some examples of different genres of writing that you are required to produce at university as opposed to genres of general writing that are out there in your everyday society. Compare and contrast the two. 1 ALMI UoM_DoL_2023 Task 2: Watch this video on an introduction to academic writing by the Writing Centre, National University of Science and Technology, MISIS. The video is structured in four parts: What is academic English? What is academic writing? What are the characteristics of academic writing? and Why is academic writing important? Watch the video to a) note down the key details in all four sections and b) note down any academic writing keywords, so that you will be ready for the subsequent steps of this lesson (Tip: Keywords are the terms that capture the essence of a subject topic). What is academic English? Fig 1.1 Considerations in Academic Writing (Swales & Feak, 2004) What are the features of academic writing? What is academic writing? Why is academic writing important? Keywords 2 ALMI UoM_DoL_2023 Lesson 2: The Academic Writing Process Adapted from Marshall, 2017 Academic writing is best thought of as a process. While this process may not be identical in every academic context, it is adopted worldwide. The following are the six stages that many academic writers go through to produce effective academic papers: Stage 1: Understand your audience, genre, and purpose Before you start organizing your ideas for a writing task, you need to consider your audience, genre, and purpose. If you consider these three factors, it will help you engage critically with your topic and write in an appropriate style. Audience: Your audience is the person or people who will read your writing. At university, this includes your lecturers who have expert knowledge of your subject and who expect you to write in a certain way. The first step of stage 1 is to ask yourself two questions: - Who is my audience? - What are the expectations of my audience? Genre: Genre refers to different text types, for example, a summary, a lab report, a reflective report, or a structured essay. Each type of text follows different genre conventions or rules about the organization and style of writing. Before writing, you need to ask yourself the following questions: - What kind of text am I writing? - What are the genre conventions of this text type? Purpose: The purpose is your reason for writing. Are you taking lecture notes? Is the essay a first draft? Are you writing an assignment for a grade? In each case, you need to think about the following questions: - Why am I writing? - Should I take risks or play safe? Stage 2: Understand your topic, focus, and task There are two common types of writing assignments: open assignments, in which you can choose your own question to write on, and closed questions that are assigned by a lecturer. In either case, you need to keep your writing in focus and on task. You can do this by breaking questions down into these three components: Topic: The topic is the general subject that you are writing about. You should not write too much about the general topic; simply mention it briefly in the introduction of your writing product. Focus: The focus is the specified aspect, or aspects, of the topic that you will write about. Most of what you write in the paper should be about the specific focus. 3 ALMI UoM_DoL_2023 Task: The task is what you have to do, for example, analyze, compare, or summarize. Again, most of what you write in the paper should follow the specific task. Task 3: Work with a partner to revisit an assignment you have received in any of your content courses. Analyse the questions based on the Stage 1 and Stage 2 of the writing process. Fill in the diagram below. Assignment: Assignment: Discuss answers with the class. 4 ALMI UoM_DoL_2023 Stage 3: Gather information and ideas The next stage is to begin the process of gathering information. This is usually done in one of two ways: (a) searching for information online or in books and then adding your own ideas, or (b) gathering ideas from your existing knowledge and then searching for information online or in books. A) Searching for information online: Do a keyword search in a general or an academic search engine using these strategies: I) Use combinations of keywords from the assignment question: Ex: EMI students, academic writing, English, difficulties, support II) Use combinations of synonyms of the keywords: Ex: EMI / English as a Medium of Instruction, university writing, academic essays III) Use quotation marks to narrow the focus: Ex: "academic writing support"; "academic writing support for EMI students" IV. Assess the reliability of the sources: Make sure the information you select is from recognized academic journals or other reliable sources. B) Gathering ideas from existing knowledge: You can gather ideas from your existing knowledge before, during, or after your search for sources; three common strategies are free-writing, concept maps, and linear notes. I) Free-writing: Write as many ideas as you can about the question. You can do this in any form or style. The main aim is to generate ideas. II) Concept maps: Gather ideas with a concept map, fill bubbles with different ideas, link the bubble with arrows, or lines, add more bubbles as needed, and describe the relationship between each group of ideas. III) Linear notes: Gather ideas with notes written in a line-by-line format, list categories, and take notes under headings and subheadings. Stage 4: Form an outline The fourth stage is to organize your information and ideas into a coherent outline ordered logically. Different types of written answers or papers require different structures, for example, the way you compare two elements is different from writing about a problem and a solution. You can then keep your outline as a focus to guide your writing. Stage 5: Write the paper sections This is the stage to start writing your paper. Most written work requires an introduction, several main body paragraphs (based on the outline), and a conclusion; include a reference list if you have brought others' ideas into 5 ALMI UoM_DoL_2023 your work. Consider your writing as "drafts" through a series of which you will finalize your writing. As you write, remember to keep your writing in focus and on task. Stage 6: Review and edit your work Remember to edit your work as you write and after you have finished writing. You should edit for the following: content (did you answer the question?); accuracy of grammar, vocabulary, and punctuation; and appropriate style for the genre of writing (this includes formatting). Task 5: Reflect on your current approach to writing by completing the table. At the end, discuss answers within your groupings. Task 6: (A) Given below are different types of academic texts, i.e., genres. Match them with the meanings. Notes A piece of research., either individual or group work, with the topic chosen by the students. Report The longest piece of writing (20,000+) normally done by a student, often for a higher degree, on a topic chosen by the student. Project A written record of the main points of a text or lecture, for a student’s personal use. Essay A general term for any academic essay, report, presentation or article. Thesis A description of something a student has done. Paper The most common type of written work, with the title given by the teacher, normally 1000-5000 words. 6 ALMI UoM_DoL_2023 (B) Study the extract from a research paper given below and identify the key components noticeable in any academic writing piece. The components can be found in the box below. Highlight your answers and annotate on the margins. Anatomical variation of the sympathetic trunk and aberrant rami communicantes and their clinical implications William Filion, Clare Lamb 1. Introduction The sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) is responsible for a wide array of visceral regulations which may have both physical and psychological repercussions when subjected to pathological changes. Exclusively arising from the intermediolateral nucleus of the spinal cord, sympathetic nerve fibres travel within the sympathetic trunk which extends from the base of the skull to the sacrococcygeal junction (LoDico and Leon-Casasola, 2014). The thoracic division of the sympathetic chain is composed of twelve thoracic ganglia which supply the aortic, cardiac and pulmonary plexuses while also innervating abdominal viscera via the celiac, superior and inferior mesenteric plexuses (Bankenahally and Krovvidi, 2016). The thoracic ganglia are located on the lateral side of the head or sometimes the neck of the ribs and are firmly covered by the endothoracic fascia as well as the parietal pleura. The chain and its ganglia are anterior to the intercostal ingress of posterior intercostal veins from the azygos system and posterior intercostal arteries from the thoracic aorta (Crossman and Tunstall, 2016). Every thoracic ganglion communicates with its spinal nerve which becomes the intercostal nerve and its collateral branches within the neurovascular bundle (Boaz et al., 2019). (…………………………….) 2. Materials and methods 2.1. Sample The anatomical examination undertaken as part of this study took place within the dissection room of the Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification (CAHID) at the University of Dundee. All dissection (……..) (the left side of one cadaver presenting extensive pleural plaques which altered the integrity of the sympathetic trunk was discarded). This sample of fourteen males and sixteen females was solely composed of Caucasian Scottish individuals aged between 49 and 103 years (x̅ = 76.5 years). 2.2. Protocol Anatomical exanimations were conducted following a precise protocol in order to maintain a standardized data compilation. Prior to the beginning of the dissection, all individuals were put in a standard supine position in order to reduce the influence of upper limbs arrangement on the location of elements to be recorded. On cadavers for which the thorax had been left intact, a mid-sagittal incision was made from the jugular notch of the manubrium to the xyphoid process with a 10-blade scalpel. Fig. 1. Schematic representation of the different measurements taken of sympathetic structures, when present. HeadingTitle Subtitle Phrase Clause Sentence Paragraph In-text citation Content removed Reporting verb Claim Direct quote Reference phrase Linking word Figure caption (no & label) Reference to a figure Segue/Transition Abbreviation Discuss your answers with the class. 7 ALMI UoM_DoL_2023 Word Order and Sentence Structures (Revision) Without the rules of grammar, words in a language would be placed in a random order, and that would have impacted comprehension and communication. These grammar rules vary from language to language and every language has its own ‘word order’ - the grammatical way in which words are arranged into sentences. English word order is different from that of Sinhala and Tamil, your mother languages. This simple formula can be used to learn the most common word order in English sentences: Subject What How Where When Why Verb + Object Manner Place Time Reason/Purpose Study the following sentences taken from a research paper analyzed for their word order using the formula given above. 1) All respondents had started seeing academic writing as a cognitive process. Who / Subject What / Verb + Object How / Manner 2) James elaborated on this issue in his final interview. Who / Subject What / Verb + Object When / Time 3) At the start of the year, I was thinking about structure and language in academic writing. When / Time Who / Subject What / Verb + Object 4) A good research-based assignment should use adequate resources so that the paper contains more ideas. Who / Subject What / Verb + Object Reason/Purpose Further, there may be longer sentences formed by combining multiple ideas in clauses. In such cases, both clauses should follow word order in their own rights. Look at the example sentence below: 5) A similar number of students talked about how they had developed an understanding that expectations for writing were firmly embedded within particular disciplinary cultures. Who / Subject What / Verb + Object Conjunction Who / Subject What / Verb Where / Place Task 6: [Homework] Watch the video on ‘Academic Insights – 9 top tips for improving academic writing’, and critically think about what the key points presented in the video. Compose ten meaningful sentences on academic writing. Focus on the key ideas presented in the video and follow the word order accurately. Review your work in the study groups. Hand over your work to your lecturer for feedback. 8