Indian Court Case Summaries: Bail, Copyright, Juvenile Justice

advertisement

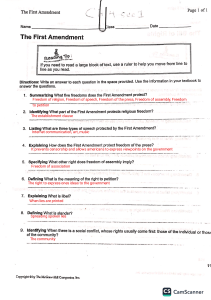

The Kerala High Court while refusing bail to two army personnel held that when the accused is an officer of the State, “leniency is not the sanction of law, instead, rigidity is the rule of law”. A single bench of Justice A. Badharudeen was hearing an anticipatory bail application where initially the offences registered against the petitioners were bailable, but subsequently, the nonbailable offence of Section 307 (Attempt to Murder) of the Indian Penal Code, was added. The petitioners requested that since two of the accused persons were army personnel, the court must take a lenient view. However, disagreeing with the said contention, the court observed that: “leniency is not the sanction of law, instead, rigidity is the rule of law." The counsel for the petitioner submitted that at the time of registering the FIR, only bailable offences were alleged and hence the accused persons were released on bail. Since, later on the offence under Section 307 of IPC was alleged, the petitioners now have the right to approach the court under Section 438 of CrPC for anticipatory bail, the petitioners argued. However, the Public Prosecutor opposed bail on the ground that Section 307 was later added based on witness statements and medical records of the hospital that showed that the victim had sustained serious injuries. Hence the police have the right to arrest, interrogate and recover weapons from the petitioners as the newly incorporated alleged offence is non-bailable. The court observed that going by the medical records and the statements of the doctor a prima facie case for Section 307 has been made out. Denying anticipatory bail to the petitioners, the court remarked that the “arrest, custodial interrogation and recovery of the weapons at the instance of the petitioner are absolutely necessary to achieve effective and fair investigation and eventful prosecution”. The court, however, made a specific note of the fact that the petitioners were free to approach the relevant jurisdictional court for bail as per the ratio in Pradeep Ram’s case. 1. One night coming back from office https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/explained-law/assam-crackdown-on-childmarriage-what-does-the-law-say-8430003/ The Delhi High Court has dismissed an application by the owner of the website, SciHub, Alexandra Elbakyan, for the dismissal of a lawsuit filed by publishing houses, Elsevier, Wiley and American Chemical Society over claims of copyright infringement and online piracy. Elbakyan had filed the application under under Order VII, Rule 11 of the Code of Civil Procedure (CPC) on the ground that the plaint did not disclose any cause of action. As such, Elbakyan contended that the suit was barred by law. Justice Sanjeev Narula dismissed the application after noting that Elbakyan had, in a written statement filed earlier, “categorically admitted that Plaintiffs are owners of copyright in subject works.” The Court also observed that Elbakyan had previously moved another application before the High Court to withdraw the said admission, which was dismissed by the Court on November 3, 2022. As such, the Court opined that the plaintiffs had discharged the initial burden under Section 55(2) (dealing with presumed ownership in cases of copyright infringement) of the Copyright Act to claim ownership towards the work. The Court further observed that a lawsuit could be rejected under Order VII, Rule 11 only if it did not disclose a cause of action. However, in the instant case, since a cause of action was made out, the said lawsuit could not be dismissed, the Court held. Therefore, it rejected Elbakyan’s application. Sci-Hub is a library website that provides free access to research papers and books. The publishing houses before the Delhi High Court had filed a copyright infringement lawsuit against Sci-Hub, and another similar website, Lib-Gen alleging that these websites were indulging in online piracy. According to the publishing houses, Sci-Hub had communicated and provided illegal access of the publishing houses’ literary works, in the form of medical journals, to the public for use and download. The website, Lib-Gen or Library Genesis was also stated to have provided access of the said works in scientific and medical fields as well as non-scientific works by unauthorized means. Sci-Hub’s owner, Elbakyan had grounded her application to dismiss this lawsuit on the claim that there was no valid copyright assignment agreement between the plaintiffs and the authors of works in respect of which copyright infringement was claimed. In this regard, Elbakyan highlighted that a valid copyright assignment agreement should spell out the royalty to be paid by the assignees to the author of the works in exchange for the “exclusive right to publish and distribute the articles.” In the absence of an agreement to pay such royalty or consideration, the agreement would be void under the Indian Contract Act, she contended through her counsel. A cursory examination of the agreements demonstrated that the Plaintiffs have not compensated the authors with any royalty or any form of consideration, the Court was told. The Court, however, opined that these were aspects to be examined during adjudication after an examination of disputed questions of facts. “There is, as discussed above, a categorical admission of Ms. Elbakyan qua copyright in favour of Plaintiffs. Therefore, the legal question urged in application, founded on the construction of the agreements, is no longer a pure question of law. Further, the dispute relating to validity of such agreements regarding adequacy or sufficiency of economic/ monetary consideration itself is a question of fact and plea advanced in the instant application, founded on provisions of Copyright Act, which would require adjudication on facts … The legality, veracity and relevancy of such agreements cannot be undertaken at this stage”, the Court said, while dismissing Elbakyan's application. Senior Advocate Amit Sibal, and advocates Sneha Jain, Snehima Jauhari, R Ramya, Surabhi Pande and Reshabh appeared for the plaintiffs. Senior Advocate Gopal Sankaranarayan, and advocates Rohan George, Shrutanjaya Bhardwaj, Shivani Vij, Akshat Agrawal, Sriya Sridhar and Nilesh Jain appeared for Alexandra Elbakyan. Advocates Vrinda Bhandari, Tanmay Singh, Abhinav Sekhri, Gautam Bhatia and Gayatri Malhotra, Rohit Sharma, Nikhil Purohit, Ashok Kumar, Jawahar Raja, Moksha Sharma, Arushi Gupta, Vaisha Sharma, M Dutta and Aditya Guha represented various intervenors. Central Government Standing Counsel Harish Vaidyanathan Shankar, and advocates Srish Kumar Mishra, Sagar Mehlawat and Alexander Mathai Paikaday represented the Union of India. Bar and bench 3 march 2023 1. The Supreme Court on Friday set aside the death sentence of a rape and murder accused who was found to be a juvenile at the time of the crime. A bench of Justices BR Gavai, Vikram Nath, and Sanjay Karol upheld the conviction but set aside the sentence based on a report Additional Sessions Judge, Manawar, District Dhar, Madhya Pradesh which categorically stated that the accused was 15 years and 4 months of age on the date of the incident, which was December 15, 2017. The Court noted that as per Juvenile Justice Act, even in case of heinous offences, a minor below 16 years of age cannot be sentenced to more than 3 years in prison. "In the present case, the appellant is held to be less than 16 years, and therefore, the maximum punishment that could be awarded is upto 3 years. The appellant has already undergone more than 5 years. His incarceration beyond 3 years would be illegal, and therefore, he would be liable to be released forthwith on this count also," the Court said. The Court, therefore, set aside the sentence. However, it upheld the conviction despite the fact that the Juvenile Justice Board (JJB) had failed to conduct an inquiry with respect to the age of the accused. The Court said that the Juvenile Justice Act intends to benefit minors only with respect to a lenient sentence so as to bring him into the mainstream of the society, and not to make the conviction ineffective. " ... a trial conducted and conviction recorded by the Sessions Court would not be held to be vitiated in law even though subsequently the person tried has been held to be a child. The intention of the legislature was to give benefit to a person who is declared to be a child on the date of the offence only with respect to its sentence part", the Court observed. Hence, if the Juvenile Justice Board (JJB) fails to conduct inquiry with respect to the age of the accused, the trial and conviction would not stand vitiated. "Having considered the statutory provisions laid down in section 9 of the 2015 Act and also section 7A of the 2000 Act which is identical to section 9 of the 2015 Act, we are of the view that merits of the conviction could be tested and the conviction which was recorded cannot be held to be vitiated in law merely because the inquiry was not conducted by JJB. It is only the question of sentence for which the provisions of the 2015 Act would be attracted and any sentence in excess of what is permissible under the 2015 Act will have to be accordingly amended as per the provisions of the 2015 Act," the Court said. Since the juvenile had already been in prison for 5 years and the maximum sentence that can be awarded as per Juvenile Justice Act of 2015 is 3 years stay in a special home, the Court ordered that he be released from custody. The bench was hearing the death-row convict's appeal against a November 2018 order of the Indore bench of the Madhya Pradesh High Court that had upheld his sentence and conviction. The accused had moved an application claiming juvenility during the pendency of the appeal before the top court. The top court called for a report from a district judge in the State, after which it was found that the boy was 15 at the time of the crime. The counsel for the appellant before the top court argued that the death sentence imposed could not have been given effect to under Section 9(2) of the 2015 Act. The said proviso says that an enquiry has to be conducted if an accused raises claim that he was a juvenile at the time of the offence. The counsel added that the boy had already undergone over five years in jail and under Section 18 of the 2015 Act, a juvenile below 16 cannot be sentence to more than three years in a correctional home. The counsel for the State government sought an ossification test to determine his current age. The top court said that the latter submission cannot be accepted at this stage as the State had not called for such a test before the trial court, and documents relating to date of birth already existed to prove his age. Further, an ossification test would only give a rough broad assessment of age with an error margin. On the aspect of the accused's sentence, the bench at the outset said, "In view of the statutory provisions and in view of the findings recorded, the appellant having been held to be a child on the date of commission of the offence, the [death] sentence imposed has to be made ineffective." It noted that the maximum sentence could not be more than three years in any case. "His incarceration beyond 3 years would be illegal, and therefore, he would be liable to be released forthwith on this count also," the judgment emphasised. However, the bench noted that nothing in Section 9 of the Act implies that a conviction recorded against a person later found to be a juvenile would also lose its effect or stall criminal proceedings. "If the conviction was also to be made ineffective then either the jurisdiction of regular Sessions Court would have been completely excluded not only under section 9 of the 2015 Act but also under section 25 of the 2015 Act, provision would have been made that on a finding being recorded that the person being tried is a child, a pending trial should also be relegated to the JJB and also that such trial would be held to be null and void." The legislative intent of the 2015 Act was not to make minors who had committed heinous crimes go scot-free, the bench made it clear. In this regard, the Court explained that the object of the 2015 Act deals with the rights and liberties of juveniles, so as to ensure that can be brought into the mainstream through a lenient sentence by lodging them in a juvenile justice board-approved home/institution. Accordingly, the Supreme Court partly allowed the appeal and set aside the death sentence. "The conviction of the appellant is upheld; however, the sentence is set aside. Further as the appellant at present would be more than 20 years old, there would be no requirement of sending him to the JJB or any other child care facility or institution. Appellant is in judicial custody. He shall be released forthwith," the Court ordered. Senior Advocate Aman Lekhi with advocates Ritwiz Rishab, Sakshi Jain, Sneha Sonam, and Rajat Mittal appeared for the appellant. Anti-death penalty body Project 39A briefed Lekhi. Deputy Advocates General Mukul Singh and Ankita Chaudhary with advocates Yashraj Singh Bundela, Sunny Choudhary, Shreyash Balaji, Sandeep Sharma, Ankita Choudhary, Abhinav Shrivastava, and Karan Bishnoi appeared for the State of Madhya Pradesh. Bar and Bench 4th march Published on : 2. 3 Mar, 2023, 2:14 pm The Karnataka High Court recently called for investigations into mobile loan apps run by Chinese companies [M/S Inditrade Fincorp Ltd v. Union of India]. Single-judge Justice M Nagaprasanna said that investigation was essential to ensure the security of India and the safety of its citizens and authorities cannot turn a blind eye to attempts by neighbouring nations to destabilize India. The Court, therefore, refused to interfere with an Enforcement Directorate (ED) probe into the workings of one such company. "The investigation would be imperative, as any effort of any neighbouring nation to destabilize this country, either economically or otherwise, by any method which would touch upon the security of the nation and safety of its citizens, cannot be turned a blind eye to, and in certain cases, certainly in the case of the petitioner, investigation cannot be stalled on this specious plea of procedural aberration as alleged by the petitioner," the Court said. Describing the modus operandi of such companies, the Court noted that Indian smartphone users are lured into getting small loans from through these apps without documentation. They are asked to download the app and grant the companies access to the contents of their smartphones. Trouble crops up when the representatives of the companies threaten to leak the contents of the borrowers' phones while seeking repayment of the loan. In some cases, repayment is sought at a rate as high as 16-20 times the EMI, the Court recorded. "It is again in public domain that several borrowers have committed suicide unable to bear the harassments of the representatives of such loan apps. The office bearers of several of these companies which control and operate such mobile loan apps are said to be entities of China or individuals from China sitting as Directors of such mobile loan apps. Therefore, it becomes necessary for an investigation, in the least to be conducted of any such company, who would operate such loan apps and has transactions with each other," the judge noted. The Court was hearing a plea filed by a company called Inditrade Fincorp challenging an order passed by the ED freezing its accounts. The petitioner company claimed to be a non-banking financial company (NBFC) which disbursed digital micro-loans under the regulation of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). The ED had frozen the company's accounts after conducting searches at Cashfree Payments and Razorpay Solutions, two of the payment gateways through which the petitioner-company operated. Before the High Court, the company contended that the search and seizure conducted by the ED, as well as the show cause notice issued by the Adjudicating Authority, were contrary to law. It was also submitted that there was no Chinese citizen involved in the company. The ED, on the other hand, alleged that the petitioner had links to Chinese apps, and was part of a "serious conspiracy" that could be unearthed only through investigation. The Court noted that as many as 15 first information reports (FIRs) were registered by the Cyber Crime Police Station at Bengaluru against several companies for their involvement in harassment and extortion of members of the public who had availed loans through mobile apps. Based on these registered cases, the ED conducted raids at the offices of Razorpay and other payment gateways, and found the names of 111 entities, of which the petitioner was one. It was found that such entities are operating in India through dummy contractors appointed on behalf of Chinese directors. Based on such information, a show cause notice was issued to the petitioner. After going through Section 17 of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, which grants the ED powers of search and seizure, the Court found that there was no procedural infirmity in the case. "The projection of procedural aberration by the petitioner would not entitle entertainment of the petition, as there is link in the money trail against the petitioner...this is enough circumstance for the Adjudicating Authority to issue a notice to the petitioner." It thus dismissed the challenge to the show cause notice as well as the freezing order Advocate Avi Singh appeared for the petitioner-company, while advocates KN Krishna Rao and Madhukar Deshpande represented the Central government and the ED respectively. 5. Maintenance is a woman's legal right in India, but accessing it is arduous Most women in India seem to want the divorce proceedings to end out of emotional and financial exhaustion, and choose to settle for whatever maintenance they get despite having a legal right to claim it. In India, ending a marriage is traumatic for most individuals. The situation becomes worse for women who must navigate settlement terms and follow up on maintenance money for their and their children’s wellbeing, adding to the complexity of the stigma of divorce. Nihala was 24 years old, with a toddler, when she decided to walk out of her marriage. “I had already suffered in a turbulent marriage and had no emotional energy to fight my ex-husband for maintenance. I just wanted out,” she says, recalling the entire ordeal. Maintenance is the allowance a spouse must pay the other spouse when they are unable to meet their monthly expenses. Maintenance also applies to children, if any, so that caregiving expenses for the child are not disproportionately borne by one parent alone. In India, maintenance can be claimed under personal laws like the Hindu Marriage Act 1955, Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act 1956, Muslim Personal Law, Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act 1986, etc. Under some personal laws like the Hindu Marriage Act, the husband is also entitled to maintenance. But these laws only permit individuals belonging to the specified religions to file for maintenance. Section 125 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) also provides for maintenance. This is a secular provision under which women of all religions can file for maintenance. “The main objective of Section 125 CrPC is to prevent the destitution of the woman after divorce. So when a woman approaches the court for maintenance, it is with a lot of hope, and one must underline that the courts have been supportive in most cases. But the effective implementation of a maintenance order always depends on the man who is supposed to pay,” says senior lawyer and human rights litigant Sandhya Raju. Though maintenance, in the broad sense, is a legal right designed to ensure that women have some financial support after a divorce, very few women are able to successfully claim this right and access the money. “My lawyers explained to me that maintenance is my legal right. I was aware of that. But my ex-husband said that if I claim maintenance, he would not give me a divorce. I was stressed about the divorce itself being prolonged, as it was affecting my child’s emotional well-being also. It was excruciating,” recalls Nihala, who hails from Kannur in Kerala, elaborates. Under the CrPC, a wife who is unable to maintain herself is legally entitled to maintenance in all scenarios. However, there are a few exceptions — if she is living with another man, if she refuses to live with the husband without any reason, if she remarries, or if the husband and wife are living separately by mutual consent. The law also provides for women in live-in relationships to claim maintenance. In Rajnesh vs Neha, the Supreme Court listed some broad guidelines with respect to maintenance — before determining the amount of maintenance to be paid, the court should assess the financial status of both parties. The SC also said the court should also evaluate their educational backgrounds, and order both parties to file an affidavit detailing their assets and liabilities. Chennai-based advocate Manoj, who deals extensively with family law cases, elaborates that the law favours maintenance for women because it takes into account what really happens in the lives of most women. “Typically, women are married off when they attain a socially accepted marriageable age. Especially women from rural and semi-urban settings may not have the opportunity to complete their education and be financially independent before marriage. In the marriage, they do all the housework and care work – which is invisible labour – for which they receive no compensation. When such a woman decides to end her marriage, she finds herself in a situation where she has nobody and nothing to rely on. This is why the husband is legally required to pay maintenance, because the woman has spent her time and labour in the marriage, building the family, with nothing else to cushion her. There has to be some support when she decides to separate,” Manoj says. Getting a court order vs getting the maintenance money Many factors contribute to why women are unable to access maintenance money even when there is a court order directing the man to pay a specific amount to his ex-wife and children. Advocate Sandhya feels that the root cause is definitely our patriarchal mindset which stigmatises divorce to such an extent that when women walk out of marriages, the society believes they deserve no aid. Shylaja (name changed), who has been married for 10 years with two children, says that her family was not in support of her decision to file for divorce. “I walked away from the marriage and lived with my parents right after the separation. But I received no support, I had to seek the help of a social support group for accommodation. And my divorce proceedings are still going on. Filing for the divorce itself has been so turbulent. It took me a year to file a petition because I did not have access to the required documents. Fighting for maintenance has been doubly hard for me given my situation,” says the 29-year-old from Chennai. Sandhya attests that the courts have been sensitive to women who seek divorce and maintenance. “Getting a maintenance order from a court is not the difficult part usually. It is getting the ex-husband to pay up that is tedious. Most women have a court order allowing maintenance, but not many actually get the money,” she says. “My ex-husband did not sign the papers for nearly two years after I decided to get a divorce, only because I asked for maintenance. Later, he agreed to pay only for my child’s expenses but said he would not pay me anything. I had to compromise because otherwise, it would only prolong the process,” says Nihala. She also feels that the restitution of conjugal rights — a legal provision where one spouse can approach the court citing that their spouse left them without cause and that their right to cohabitation is violated — is abused by men who have no intention to pay maintenance. “When I filed for maintenance, my ex filed for restitution of conjugal rights, claiming that if I lived with him he was willing to look after me. That made it look as if I was asking for a divorce for no serious reason. He knew I would not go back, so he used the law to have me run around in circles,” Nihala adds. Manoj says that procedurally, the court can pass an order for the attachment of property or salary of the ex-husband if he refuses to make payment. “If that also does not work, the court can further order civil imprisonment and have the man taken into custody for non-payment. But what usually happens is that when a man does not want to pay, he absconds. Some men also make up excuses about losing their jobs or not being paid salaries, to evade payment of maintenance,” he adds. He also notes that in situations where the ex-husband is absconding, an ex-parte divorce (divorce in the absence of one spouse) is granted by the court. This further complicates the process of getting maintenance and women then have the additional onus of tracing their absconding spouses, in which they are often unsuccessful. While looking at the legality of maintenance, alimony is one term that often seems similar. Alimony is a lump sum amount paid as a final settlement during a divorce proceeding, whereas maintenance is a monthly amount paid for the daily sustenance of a divorced woman who is unable to look after herself. “In many cases, people also use settlement as a loophole to delay payment. They insist that they are willing to pay a lump sum to their ex-wife instead of a monthly allowance and keep dragging the negotiation procedure to push the payment. What happens here is that the woman suffers, especially when she has no other income and has children to look after,” says Sandhya. Shylaja also says that women who decide to push for maintenance face a lot of gaslighting. “Everyone told me that men are bound to be problematic and that we women must compromise. They tried to water down my efforts to get a divorce and maintenance by emotionally confusing me with questions like ‘how will you survive with two kids and no other support in the absence of a husband’. These things sometimes get to us, making us doubtful about our own rights,” she says. Domestic violence and accusations of false case for money The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act (PDV), 2005 is another legislation in India that provides for maintenance. “Women who suffer domestic violence and dowry harassment are entitled to claim maintenance. But when such a case is filed, the husband immediately campaigns that the woman is making a false claim of abuse just to extort money,” says Sandhya. “There are different forms of domestic violence that women experience. When we look at Dalit women, in the case of marriage with men from other religions or dominant castes, there is caste-based violence as well. But the key problem with domestic violence is that by the time the woman files a case, there is barely any physical evidence to prove it,” observes Manoj. Both Manoj and Sandhya assert that the normalisation of violence in marriages encourages women to cover it up and suffer generationally, due to which there is no recorded evidence of the violence. “Women who seek medical attention because of domestic abuse also seldom tell doctors the real reason behind their injuries. Besides, families and society urge them to stay in the marriage. When such women finally decide to claim maintenance under the PDV Act, there is no evidence of the abuse. There are no witnesses also since these things happen in private. It then becomes easy for the husband to say that the woman is making a fake claim to extort money from him,” says Manoj. Josephine (name changed), a mother of two who has been married for seven years, says that she faced severe domestic abuse and that her husband would not provide for her and their children. “He filed for divorce, but nobody appeared from his end at the court, and consequently, the case got dismissed. I approached the court later for maintenance, but there was no representation from my husband’s side and he was not willing to accept the court notice either. I did not know his address or where he was working to make sure that he received the notice since I had moved to my parents’ place by then. So, I was not able to file for maintenance,” she says. Shaming women who claim maintenance Manoj notes that women who claim maintenance are seen as capitalising on the breakdown of their marriage. “To address the issue of shaming women who claim maintenance, we must first understand why the law provides for maintenance,” he says. Many people feel that maintenance is an ‘undue advantage’ sanctioned to women through the law to ‘loot’ their ex-husbands. Therefore, when a maintenance petition is filed, the woman is accused of wanting her exhusband’s money despite not wanting to live with him anymore. “My exhusband said ‘You don’t want me, but you want my money?’” recalls Shylaja. “Everyone accused me of wanting to access my ex’s wealth. Nobody even felt that maintenance is my right, that I would need help to raise my kids and sustain myself. The comments got so painful that at one point I thought about dropping the attempt to claim maintenance. I’m still processing my thoughts,” she says. “It is a double-edged sword in any case. If the woman has any source of income, the defence will cite that to not pay maintenance. We do not look at marriage in terms of the years spent and the labour invested in it, which deserves compensation. We think maintenance is quick, easy money that women claim so they can live off their ex-husband’s money. Even women internalise it sometimes and shame themselves, or feel reluctant to ask for maintenance, slogging every day with whatever they can manage,” says Sandhya. The attitude of shaming women who seek divorce or maintenance exists even within the judiciary, notes 31-year-old Meenakshi. “When I was in court for my divorce proceeding, I witnessed a young woman being reprimanded by the judge for even filing for a divorce. She shamed the woman for being financially independent, saying that when women earn for themselves they do not want to ‘adjust’ in marriages. It is an attitude problem,” she says, adding that she is ‘fortunate enough’ to have had the emotional support to walk out of a troubled marriage. Most women seem to want the ordeal to end, and choose to settle for whatever they can get after a divorce despite having to rebuild emotionally and financially. “I’m educated, and I can try to build a life for myself and my child even though my ex refused to pay me any money. But what about women who are not like me? Even in my case, it is my right to get maintenance but I was forced to accept a divorce without it because I just wanted the process to end. I wanted peace,” recalls Nihala. “A woman I knew, who was a domestic worker, put together everything she had and got her daughter married. The son-in-law abused her daughter and took away all her gold and money. But the woman and daughter were so traumatised and exhausted that they did not have the strength or the resources to pursue the case legally,” recalls Sandhya. In the absence of facilitating mechanisms and community support, most women just drop their claim for maintenance, accepting defeat against a system that simply fails to help them access a legal right. “I don’t have a job but I need to raise my kids, sustain myself, and fight the case in court. Whether my husband appears in court or not, if I want to file a maintenance case I need to hire a lawyer, which is a financial burden on me. So I dropped the idea of getting maintenance. I am making myself believe that I won’t get anything anyway, so I remain silent about it and focus on looking after my kids,” says Josephine. Sandhya says that financial independence is the key to ensuring that women do not get entangled in judicial red tape. “I always encourage young women to try to be financially stable before they get married. Money makes decisionmaking easier if the marriage falters. Even working women face divorce stigma, but at least while they fight the system they have something that is their own to fall back on,” she says. “It is surely unfair to put the burden of an ineffective justice system on women by suggesting that they must look out for themselves, especially those who have no privilege, but this is how we can ensure that women are better placed at this point, while we continue to interrogate and reform the system,” she adds. This reporting is made possible with support from Report for the World, an initiative of The GroundTruth Project. Supreme Court Issues Directions For Timely Release Of Prisoners After Getting Bail Anurag Tiwary 2 Feb 2023 2:38 PM The Supreme Court has issued the following guidelines on the issue of undertrial prisoners who continue to be in custody despite having been granted the benefit of bail on account of their inability to fulfill the conditions stipulated in the bail order or otherwise. “1)The Court which grants bail to an undertrial prisoner/convict would be required to send a soft copy of the bail order by e-mail to the prisoner through the Jail Superintendent on the same day or the next day. The Jail Superintendent would be required to enter the date of grant of bail in the e-prisons software [or any other software which is being used by the Prison Department]. Also Read - Supreme Court Asks Centre To Ascertain Number Of Tiger Deaths In Recent Past 2) If the accused is not released within a period of 7 days from the date of grant of bail, it would be the duty of the Superintendent of Jail to inform the Secretary, DLSA who may depute para legal volunteer or jail visiting advocate to interact with the prisoner and assist the prisoner in all ways possible for his release. 3) NIC would make attempts to create necessary fields in the e-prison software so that the date of grant of bail and date of release are entered by the Prison Department and in case the prisoner is not released within 7 days, then an automatic email can be sent to the Secretary, DLSA. Also Read - Supreme Court Refuses To Interfere With HC Order Quashing POCSO FIR Over 'Relationship' Between Man & Minor Girl 4) The Secretary, DLSA with a view to find out the economic condition of the accused, may take help of the Probation Officers or the Para Legal Volunteers to prepare a report on the socio-economic conditions of the inmate which may be placed before the concerned Court with a request to relax the condition (s) of bail/surety. 5) In cases where the undertrial or convict requests that he can furnish bail bond or sureties once released, then in an appropriate case, the Court may consider granting temporary bail for a specified period to the accused so that he can furnish bail bond or sureties. Also Read - Person Convicted For Rape-Murder Found To Be Juvenile : Supreme Court Sets Aside Death Sentence, Sustains Conviction 6) If the bail bonds are not furnished within one month from the date of grant bail, the concerned Court may suo moto take up the case and consider whether the conditions of bail require modification/ relaxation. 7) One of the reasons which delays the release of the accused/ convict is the insistence upon local surety. It is suggested that in such cases, the courts may not impose the condition of local surety.” Also Read - Spotlight On Recent Appointments To Supreme Court - Justice Sanjay Karol The above directions are part of the detailed and comprehensive suggestions submitted to court by by the three Amici Curiae viz. Advocates Gaurav Agrawal, Liz Mathew and Devansh A. Mohta, after discussion with ASG K. M. Nataraj. The bench of Justices Sanjay Kishan Kaul and Abhay S. Oka also observed in the order that the Government of India should discuss with NALSA whether it would give access to the e-prison portal on a protected basis to the Secretaries of the SLSAs and DLSAs which would facilitate better follow up with the prison authorities. ASG KM Nataraj assured the bench that granting permission wouldn't be a problem, however, he would seek instructions and get back to the court on the next date of hearing. During the last hearing, the court had issued detailed guidelines on disposing cases through plea bargaining, compounding of offences & Probation Of Offenders Act. The court posted the hearing to March. Thanking the Amicus Curiae for their hard work in assisting the court, Justice Kaul, after passing the orders said, “All of you, the Amicus, the ASG are doing more work I think to sort out this issue than could be done if the number of courts would only be hearing this issue” Case Title: In Re Policy Strategy for Grant of Bail SMW (Crl.) No. 4/2021 Citation : 2023 LiveLaw (SC) 76 Bail bond- Supreme Court issues seven directions to avoid delay in release of prisoners after getting bail Click here to read/download the order Livelaw Article 105 of Constitution: The limits to free speech in Parliament, and what Supreme Court has ruled In a letter to Rajya Sabha Chairman Jagdeep Dhankhar, Congress president Mallikarjun Kharge cited Article 105 of the Constitution that deals with the privileges and powers of parliamentarians. What is the provision and how does it protect MPs? Protesting against the expunction of parts of his speech on the motion of thanks on the President’s Address, Leader of Opposition in Rajya Sabha and Congress president Mallikarjun Kharge has argued that MPs have freedom of speech, and that he did not make any personal allegations in the House. In his letter to Rajya Sabha Chairman Jagdeep Dhankhar on Thursday (February 9), Kharge cited Article 105 of the Constitution that deals with the privileges and powers of parliamentarians. What is the provision and how does it protect MPs? What does Article 105 say? Article 105 of the Constitution deals with “powers, privileges, etc of the Houses of Parliament and of the members and committees thereof”, and has four clauses. It reads: “(1) Subject to the provisions of this Constitution and to the rules and standing orders regulating the procedure of Parliament, there shall be freedom of speech in Parliament. (2) No member of Parliament shall be liable to any proceedings in any court in respect of any thing said or any vote given by him in Parliament or any committee thereof, and no person shall be so liable in respect of the publication by or under the authority of either House of Parliament of any report, paper, votes or proceedings. (3) In other respects, the powers, privileges and immunities of each House of Parliament, and of the members and the committees of each House, shall be such as may from time to time be defined by Parliament by law, and, until so defined, shall be those of that House and of its members and committees immediately before the coming into force of section 15 of the Constitution (Forty-fourth Amendment) Act, 1978. (4) The provisions of clauses (1), (2) and (3) shall apply in relation to persons who by virtue of this Constitution have the right to speak in, and otherwise to take part in the proceedings of, a House of Parliament or any committee thereof as they apply in relation to members of Parliament.” Simply put, Members of Parliament are exempted from any legal action for any statement made or act done in the course of their duties. For example, a defamation suit cannot be filed for a statement made in the House. This immunity extends to certain non-members as well, such as the Attorney General for India or a Minister who may not be a member but speaks in the House. In cases where a Member oversteps or exceeds the contours of admissible free speech, the Speaker or the House itself will deal with it, as opposed to the court. So are there absolutely no restrictions on this privilege? There are some, indeed. For example Article 121 of the Constitution prohibits any discussion in Parliament regarding the “conduct of any Judge of the Supreme Court or of a High Court in the discharge of his duties except upon a motion for presenting an address to the President praying for the removal of the Judge..”. Also Explained |What is the Aljamea-tus-Saifiyah which PM Narendra Modi inaugurated in Mumbai? Where did the idea of this privilege of Parliament originate? The Government of India Act, 1935 first brought this provision to India, with references to the powers and privileges enjoyed by the House of Commons in Britain. An initial draft of the Constitution too contained the reference to the House of Commons, but it was subsequently dropped. However, unlike India where the Constitution is paramount, Britain follows Parliamentary supremacy. The privileges of the House of Commons is based in common law, developed over centuries through precedents. In the 17th-century case ‘R vs Elliot, Holles and Valentine’, Sir John Elliot, a member of the House of Commons was arrested for seditious words spoken in a debate and for violence against the Speaker. However, the House of Lords provided immunity to Sir John, saying that words spoken in Parliament should only be judged therein. This privilege has also been enshrined in the Bill of Rights 1689, by which the Parliament of England definitively established the principle of a constitutional monarchy. In the 1884 case of ‘Bradlaugh v. Gosset’, then Chief Justice Lord Coleridge of the House of Lords observed: “What is said or done within the walls of Parliament cannot be inquired into in a court of law.” Don't Miss |Who are the Dawoodi Bohras, and what is the excommunication petition before the Supreme Court? And what have courts in India ruled? * In the 1970 ruling in ‘Tej Kiran Jain v N Sanjiva Reddy’, the Supreme Court dismissed a plea for damages filed by the followers of the Puri Shankaracharya against parliamentarians. The judgment recalled that “in March 1969, a World Hindu Religious Conference was held at Patna. The Shankaracharya took part in it and is reported to have observed that untouchability was in harmony with the tenets of Hinduism and that no law could stand in its way, and to have walked out when the National Anthem was played.” The petitioners claimed that when the issue was debated in Parliament, uncharitable remarks were made against the seer. The petitioners argued that the MPs’ immunity “was against an alleged irregularity of procedure but not against an illegality”. However, the SC ruled that “the word “anything” in Article 105 is of the widest import and is equivalent to ‘everything’.” * Almost two decades later, in 1998, the SC in the case of ‘P V Narasimha Rao vs. State’ answered two questions on parliamentary privilege, broadly relating to questions of corruption. In 1993, Narasimha Rao was Prime Minister of a minority government at the Centre. When a vote of no-confidence was called by members of the opposition against the government, some factions of the ruling party paid Jharkhand Mukti Morcha (JMM) members to vote against the motion. The motion was defeated in the House, with 251 members supporting it and 265 members against it. Two questions came before the Supreme Court. One, whether MPs could claim immunity from prosecution before a criminal court on charges of bribery related to parliamentary proceedings, under Articles 105(1) and 105(2). Two, whether an MP is a “public servant” under the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988. A five-judge Bench of the apex court ruled that the ordinary law would not apply to the acceptance of a bribe by an MP in case of parliamentary proceedings. “Broadly interpreted, as we think it should be, Article 105(2) protects a Member of Parliament against proceedings in court that relate to, or concern, or have a connection or nexus with anything said, or a vote given, by him in Parliament,” the court said, giving a wider ambit to the protection accorded under Article 105(2). The Court rationalised this by saying it will “enable members to participate fearlessly in Parliamentary debates” and that these members need the wider protection of immunity against all civil and criminal proceedings that bear a nexus to their speech or vote. Indian Express Explained he Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Association (SCAORA) on Monday (January 23) condemned business magazine Forbes India’s decision to publish a ‘Legal Powerlist’ of the top 25 Advocates-on-Record. The SCAORA unanimously passed a resolution denouncing the list as “misleading” and “unauthorized information” after its executive committee received a complaint. SCAORA said the list was a “clear case of misrepresentation”, and undermined the interests of Supreme Court AORs. “It is resolved that SCAORA would request Hon’ble Judges to take into consideration our concern in the larger interest of legal professionals,” the resolution published on the association’s website says. What is the law on lawyers advertising their work? In India, lawyers and legal practitioners are not allowed to advertise their work. Section 49(1)(c) of the Advocates Act, 1961 empowers the Bar Council of India (BCI) to make rules with respect to “the standard of professional conduct and etiquette to be observed by advocates”. Rule 36 in Chapter II (“Standards of Professional Conduct and Etiquette”) of Part VI (“Rules Governing Advocates”) of the BCI Rules published in 1975 prohibits lawyers from advertising their work. The Rule reads: “An advocate shall not solicit work or advertise, either directly or indirectly, whether by circulars, advertisements, touts, personal communications, interviews not warranted by personal relations, furnishing or inspiring newspaper comments or producing his photographs to be published in connection with cases in which he has been engaged or concerned.” Also in Explained |Court says journalists not exempt from disclosing sources: What is the law on this? Rule 36 also requires that an advocate’s signboard or nameplate “should be of a reasonable size”. The signboard/ nameplate or stationery “should not indicate that he is or has been President or Member of a Bar Council or of any Association or that he has been associated with any person or organisation or with any particular cause or matter or that he specialises in any particular type of work or that he has been a Judge or an Advocate General”. An advocate who violates this rule can face punishment for professional or other misconduct under Section 35 of the Advocates Act. This section empowers the State Bar Council to refer the case to a disciplinary committee that can, after giving the advocate an opportunity to be heard, suspend him for some time, remove his name from the state’s roll of advocates, or reprimand him — or dismiss the complaint altogether. What is the basis for having such a rule? In a 1975 ruling, Justice Krishna Iyer of the Supreme Court in ‘Bar Council of Maharashtra vs. M V Dabholkar’ provided the rationale for this: “Law is no trade, briefs no merchandise, and so the leaven of commercial competition or procurement should not vulgarise the legal profession.” In 1995, in ‘Indian Council Of Legal Aid & Advice vs Bar Council Of India & Anr’, the SC said that “the functions of the Bar Council include the laying down of standards of professional conduct and etiquette which advocates must follow to maintain the dignity and purity of the profession.” Law, the SC said, was a “noble profession”, and those engaged in it have certain obligations in society as the practice of law has a “public utility flavour”. What changed in 2008? Following a challenge in the SC to the constitutional validity of Rule 36 in ‘VB Joshi vs Union of India’, the restrictions were somewhat relaxed. In 2008, Rule 36 was amended, and advocates were allowed to provide their names, contact details, post qualification experience, enrollment number, specialisation, and areas of practice on their websites. Also in Explained |Freedom of speech online: What are the Florida and Texas laws the US top court could hear a challenge to A proviso to Rule 36 inserted in 2008 said the rule “will not stand in the way of advocates furnishing website information as prescribed in the Schedule under intimation to and as approved by the Bar Council of India”. With the proliferation of web portals and apps offering legal services on the Internet, legal practitioners have been finding indirect and more subtle ways to advertise themselves while staying within the confines of Rule 36. Many of them post about their work on Linkedin, organise and speak at webinars and seminars, write columns for newspapers, and appear on TV programmes and debates. What is the situation in other countries? Lawyers can legally advertise their services in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and the European Union. * UK: Rule 7 of the Solicitors Code of Conduct 2007, allows lawyers in the UK and Wales to advertise their practice, business or firm as long as it’s not done in a “misleading” or “false” way. Rule 7 reads: “You are generally free to publicize your firm or practice, subject to the requirements of this rule.” * US: The American Bar Association’s Model Rules of Professional Conduct (MRPC) issued in 1908 prohibited advertising for lawyers. Ordinance 27 reiterated the prohibition by construing “soliciting” as unprofessional. However, after the US Supreme Court’s landmark 1977 decision in ‘Bates vs Arizona’, lawyers can advertise their services. Bar associations of states are free to make laws in this regard. * EU: Section 2.6 of the Council of Bars and Law Societies of the Europe Code of 2006 discusses the aspect of “Personal Publicity”. Section 2.6.1 allows a lawyer to inform the public about his services as long as the information is accurate and not misleading, respectful of confidentiality obligations and other core values of the legal profession. Personal publicity by a lawyer in any form of media is permitted to the extent it complies with the requirements of Section 2.6.1. Plea in Delhi High Court: What is the ‘Right to be Forgotten’? The 'Right to be Forgotten' is the right to remove or erase content so that it’s not accessible to the public at large. It empowers an individual to have information in the form of news, videos, or photographs deleted from internet records so it doesn't show up through search engines like Google. The Delhi High Court, on March 15, is all set to hear a doctor’s plea for enforcement of his ‘Right to be Forgotten’, which includes the removal of news articles and other incriminating content related to his “wrongful arrest” in response to a “fabricated FIR against him” which he claims is causing detriment to his life and personal liberty. What is this case? In “Dr. Ishwarprasad Gilda vs. Union of India & Others”, a practicing doctor who is a “world-renowned figure in the fight against HIV-AIDS” was accused of offenses under the Indian Penal Code, including causing death by negligence (Section 304A), cheating (Section 417) and personating a public servant (Section 170). The doctor was accused of illegally procuring medicines from abroad and administering them to HIV patients in India, who he was also accused of “mishandling”. When one of the patients, Girdhar Verma, passed away, the petitioner contends he was wrongfully arrested on April 23, 1999, and was subsequently given bail on May 11, 1999. Thereafter, relying on a trial court order from August 4, 2009, exonerating him, he reiterated that there was no evidence of him having engaged in any illegality. Thus, the doctor approached the Delhi High Court seeking directions to the respondents like Google, the Press Information Bureau, and the Press Council of India to remove all “irrelevant” news content causing “grave injury” to his reputation and dignity or to pass any other order or direction to safeguard his dignity, including availing his “Right to be Forgotten.” What is the Right to be Forgotten? The “Right to be Forgotten” is the right to remove or erase content so that it’s not accessible to the public at large. It empowers an individual to have information in the form of news, video, or photographs deleted from internet records so it doesn’t show up through search engines, like Google in the present case. What is the law on the Right to be Forgotten? Section 43A of the Information Technology Act, 2000 says that organizations who possess sensitive personal data and fail to maintain appropriate security to safeguard such data, resulting in wrongful loss or wrongful gain to anyone, may be obligated to pay damages to the affected person. While, the IT Rules, 2021 do not include this right, they do however, lay down the procedure for filing complaints with the designated Grievance Officer so as to have content exposing personal information about a complainant removed from the internet. Also Read |Pawan Khera arrest | Section 153A: its use and misuse Moreover, on December 11, 2019, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology introduced the Personal Data Protection Bill in the Lok Sabha. While this bill is yet to be passed by the parliament, owing to a parliamentary joint committee’s suggestion to amend 81 of the 99 sections of the same, Clause 20 under Chapter V of the draft bill titled, “Rights of Data Principal” mentions the “Right to be Forgotten” as the right to restrict or prevent the continuing disclosure of personal data by a “data fiduciary”. What have the courts said so far? While the right is not recognized by a law or a statute in India expressly, the courts have repeatedly held it to be endemic to an individual’s Right to Privacy under Article 21 since the Apex Court’s 2017 ruling in “K.S.Puttaswamy vs Union of India”. In this case, a nine-judge bench, including CJI Chandrachud, referred to the European Union Regulation of 2016 which recognized “the right to be forgotten” an individual’s right to remove personal information from the system when “he is no longer desirous of his personal data to be processed or stored” or when “its no longer necessary, relevant, or is incorrect and serves no legitimate interest”. However, the court also recognized that such a right can be restricted by the right to freedom of expression and information or “for compliance with legal obligations”, or for the performance of tasks in the public interest or on “grounds of public interest in the area of public health” or “scientific or historical research purposes or statistical purposes, or for the establishment” and “exercise or defense of legal claims”. Also Read |Russia’s sports exile and the controversy surrounding ‘neutral’ Russian athletes In “Jorawer Singh Mundy vs Union of India”, an American citizen approached the Delhi High Court in 2021 seeking the removal of all publicly available records of a case registered against him under the Narcotics Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985. He argued that although the trial court acquitted him back in 2011, he was unable to find a job in the United States on account of a quick Google search showing the judgment in his case. Despite a good academic record, this prejudiced his chances of employment, he argued. Thus, the court directed respondents like ‘IndianKanoon’ to remove the same. What are the origins of this Right? The Right to be Forgotten originates from the 2014 European Court of Justice ruling in the case of “Google Spain SL, Google Inc v Agencia Española de Protección de Datos, Mario Costeja González”, where it was codified for the first time following a Spanish man’s quest to make the world forget a 1998 advertisement saying “his home was being repossessed to pay off debts.” Thereafter, it was included in the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in addition to the right to erasure. Article 17 of the GDPR provides for the right to erasure and lays down certain conditions when such a right can be restricted.