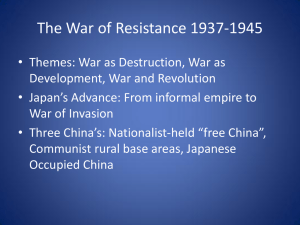

Consequences of the Rape of Nanking During the Sino-Japanese War, Japanese forces capture Nanking, the capital of China. At that time, the Chinese government fled to Hankow (Matson 1). The Chinese were resisting the Japanese forces. In order to break this Chinese resistance, Japanese General Matsui ordered the destruction of the Nanking. The Nanking Massacre is an atrocity in the history of Japan-Chinese relations. The massacre was a six-week mass murder and war rape followed by Japanese capture of Nanjing (Nanking), on December 13, 1937 (Chang 100). During the period Japanese Soldiers disarmed thousands of Chinese civilians and war prisoners. Japanese soldiers also raped 20,000 – 80,000 women. The rape of Nanking remains a contentious issue in politics. Some historical revisionists and Japanese nationalists dispute the event claiming that the massacre was exaggerated for propaganda purposes (Honda 45). There are enormous efforts by Japanese Nationalists to deny or rationalize Japanese war crimes. However, the controversy arising from the Rape of Nanking remains a stumbling block in Sino-Japanese relations. It is also a stumbling block to international relations between Japan and other Asia-Pacific nations such as South Korea and the Philippines (He 50). Many senior members of the Japanese high command were responsible for the atrocities committed by Japanese soldiers in Nanking including Emperor Hirohito. Emperor Hirohito made all the major decisions during the operation including the decision to invade china in 1937. Hirohito’s uncle, Prince Asaka was a key player in the operation because he ordered the Japanese soldiers to kill all captives. In addition, he was responsible for the gendercide against Nanking’s men. General Nakajima Kesago, commander of the 16th division was also held responsible for the Nanking Massacre. He ordered the beheading of two war prisoners as a test of his new sword (Yin and Young 284). In 1946-1947 there were war crimes trials in Nanjing. However, the trials only affected a few Japanese war criminals. Tani Hisao, a commander of the 6th division was sentenced to death in March 1947 and executed. The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE) tried up to 30 key Japanese commanders. The tribunal tried Commander Matsui Iwane of the Central China Expeditionary Force. Matsui and other six ‘Class A’ war criminals were executed. General Yanagawa Heisuke and Lieut. General Nakajima Kesago died of natural cause before they could be executed (Yamamoto 112). However, some members of the royal family who were also responsible for the Nanking massacre were not tried and executed. Emperor Hirohito and Prince Asaka received immunity since they members of the royal family. In Tokyo, many Japanese political and military leaders faced tribunal on war crimes. Majority of judges in Tokyo ruled out that General Matsui was responsible for all the atrocities in Nanking (Yoshida 96). However, some Japanese scholars deny the killings during the massacre claiming that authorities justified the deaths either militarily, accidentally or as isolated cases of atrocities. These scholars claim that people fabricated the massacre for political reasons (Shudo 10). The Japanese government admitted and was guilty of the killing thousands of civilians, looting and other crimes its army committed during the war. However, some Japanese officials still deny the killings arguing that the deaths were military in nature. Other consequences of the massacre included social and economic effects (Fisman, Hamao and Wang 34). Countries like Germany admitted their guilt for wartime genocide and passed laws to make holocaust denial a crime, there is no equivalent legislation in Japan (Rees 1). Works Cited Chang, Iris. Rape of the Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II. New York: BasicBooks, 1997. Fisman, Hamao and Wang. The Impacts of cultural aversion on economic exchange: Evidence from shocks to Sino-Japanese relations. University of Southern California, 2012. He, Yang. "Remembering and Forgetting the War: Elite Mythmaking, Mass Reaction, and SinJapanese Relations 1950-2006." History and Memory, Volume 19, Issue 2 (2007): 43-74. Honda, Katsuichi. The Naning Massacre. M.E. Sharpe, 1999. Matson. Nationalism and the Nanjing Massacre. 2012. Rees, Jasper. "Why does apan Still refuse to face up to the atrocity its army revelled in?Two new films have reopened old wound about the Nanking Massacre." DailyMail Online 28 April 2010. Shudo, Higashinakano. The Nanking Massacre: Fact Versus Fiction. New York: Pegasus, 2005. Yamamoto, Masahiro. Nanking: Anatomy of an Atrocity. Wesport, Conneticut: Praeger, 2000. Yin, James and Shi Young. The Rape of Nanking. Innovative Publishing Group, 1999. Yoshida, Takashi. The Making of the "Rape of the Nanking": History and Memory in Japan, China. Oxford University Press, 2006.