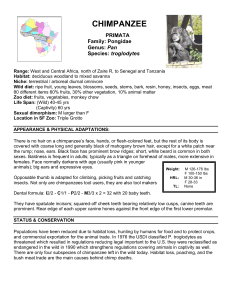

What is Evolution? Humans did not evolve from apes, gorillas or chimps. We are all modern species that have followed different evolutionary paths, though humans share a common ancestor with some primates, such as the African ape. The timeline of human evolution is long and controversial, with signi icant gaps. Experts do not agree on many of the start and end points of various species. So this timeline involves signi icant estimates. To say we are more "evolved" than our hairy cousins is just wrong. (See how long you last naked in the Congo Heartland, and then tell me who's got the evolutionary upper hand.) Thinking that a species evolves in order to survive is to put the cart before the horse. Genetic mutations happen all the time, without fanfare and often without any measurable change in the organism's lifestyle. In general, the mutations most likely to be passed to future generations are those that prove useful to either individual or species survival. The "usefulness" of a mutation depends largely on shifting environmental factors like those of food, predators, and climate, and also on social pressures. Evolution is a matter of illing ecological and social niches. African apes are still around because their environment has encouraged the reproductive success of individuals with different genetic material than ours. Evolution is an ongoing process of trial and error, of which all modern primates are still a part. Chimps vs. Humans: How Are We Different? "Give orange me give eat orange me eat orange give me eat orange give me you." That's the longest string of words that Nim Chimpsky, a chimpanzee who scientists raised as a human and taught sign language in the 1970s, ever signed. He was the subject of Project Nim, an experiment conducted by cognitive scientists at Columbia University to investigate whether chimps can learn language. After years of exposing Nim to all things human, the researchers concluded that although he did learn to express demands — the desire for an orange, for instance — and knew 125 words, he couldn't fully grasp language, at least as they de ined it. Language requires not just vocabulary but also syntax, they argued. "Give orange me," for example, means something different than "give me orange." From a very young age, humans understand that; we have an innate ability to create new meanings by combining and ordering words in diverse ways. Nim had no such capacity, which is presumably true for all chimps. Many cognitive scientists believe that humans' ability to innovate by varying syntax engenders much of the richness and complexity of our thoughts and ideas. This gulf between humans and our nearest primate relatives is but one of many. Stance Humans are bipedal, and except for short bouts of uprightness, great apes walk on all fours. It's a profound disparity. Kevin Hunt, director of the Human Origins and Primate Evolution Lab at Indiana University, thinks humans' ancestors stood upright in order to reach vegetation in low-hanging tree branches. "When Africa started getting drier about 6.5 million years ago, our ancestors were stuck in the east part, where the habitat became driest," Hunt told Life's Little Mysteries. "Trees in dry habitats are shorter and different than trees in forests: In those dry habitats, if you stand up next to a 6-foot-tall tree, you can reach food. In the forest if you stand up, you're 2 feet closer to a tree that's 100 feet tall and it doesn't do you the least bit of good." Thus, our ancestors stood up in the scrubby, dry areas of Africa. Chimps in the forests did not. Charles Darwin was the irst to igure it out why the simple act of standing up made all the difference in separating man from ape. One word: tools. "Once we became bipedal, we had hands to carry tools around. We started doing that only 1.5 million years after we became bipedal," Hunt explained. Give it a couple million years and we turned those chipped stones into iPads. Strength According to Hunt, if you shave a chimp and take a photo of its body from the neck to the waist, "at irst glance you wouldn't really notice that it isn't human." The two species' musculature is extremely similar, but somehow, pound-for-pound, chimps are between two and three times stronger than humans. "Even if we worked out for 12 hours a day like they do, we wouldn't be nearly as strong," Hunt said. Once, in an African forest, Hunt watched an 85-pound female chimp snap branches off an aptly-named ironwood tree with her ingertips. It took Hunt two hands and all the strength he could muster to snap an equally thick branch. No one knows where chimps get all that extra power. "Some of their muscle arrangement is different — the attachment points of their muscles are arranged for power rather than speed," Hunt said. "It may be that that's all there is to it, but those who study chimp anatomy are shocked that they can get that much more power out of subtle changes in muscle attachment points." Alternatively, their muscle ibers may be denser, or there may be physiochemical advantages in the way they contract. Whatever the case may be, the outcome is clear: "If a chimp throws a big rock and you go over and try to throw it, you just can't," Hunt said. Conversation Herb Terrace, the primate cognition scientist who led Project Nim, thinks chimps lack a "theory of mind": They cannot infer the mental state of another individual, whether they are happy, sad, angry, interested in some goal, in love, jealous or otherwise. Though chimps are very pro icient at reading body language, Terrace explained, they cannot contemplate another being's state of mind when there is no body language. "I believe that a theory of mind was the big breakthrough by our ancestors," he wrote in an email. Why does he think that? It goes back to Nim the signing chimp's linguistic skills. Like an infant human, Nim spoke in "imperative mode," demanding things he wanted. But infantile demands aren't really the hallmark of language. As humans grow older, unlike chimps, we develop a much richer form of communication: "declarative mode." "Declarative language is based on conversational exchanges between a speaker and a listener for the purpose of exchanging information," Terrace wrote. "It is maintained by secondary rewards such as 'thank you,' 'that's very interesting,' 'glad you mentioned that.' In the case of declarative language, a theory of mind is clearly necessary. If the speaker and the listener could not assume that their conversational partners had a theory of mind there would be no reason for them to talk to each other. Why bother if there is no expectation that your audience would understand what you said?" He added, "I know of no example of a conversation by non-human animals." This limitation, perhaps more than any other, prevents a series of events like that in the new ilm "Rise of the Planet of the Apes." In the ilm, chimps learn sign language — a realistic scenario. But it's a stretch to imagine them using their new skill to discuss and plan a world takeover. Genes The chimpanzee genome was sequenced for the irst time in 2005. It was found to differ from the human genome with which it was compared, nucleotide-for-nucleotide, by about 1.23 percent. This amounts to about 40 million differences in our DNA, half of which likely resulted from mutations in the human ancestral line and half in the chimp line since the two species diverged. From those mutations come the dramatic differences in the species that we see today — differences in intelligence, anatomy, lifestyle and, not least, success at colonizing the planet.