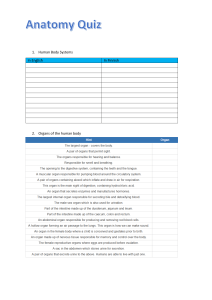

TRADE RESTRICTIONS IN UNITED STATES OF AMERICA DURING THE TRADE WAR A Project submitted to H.R College, Mumbai By Vansh Rakesh Shah Class: M-COM-I (business management) year 2021-2022 Roll no: HFPMCBM066 Semester – I Subject: International Economics INDEX NO. TOPICS PAGE 1 INTRODUCTION: ECONOMIC HISTORY OF USA 1 2 TRADE RESTRICTIONS OF USA 2-19 3 BIBLIOGRAPHY 20-22 INTRODUCION : HISTORY OF USA The country has trade relations with many other countries. Within that, the trade with Europe and Asia is predominant. To fulfil the demands of the industrial sector, the country has to import mineral oil and iron ore on a large scale. Machinery, cotton yarn, toys, mineral oil, lubricants, steel, tea, sugar, coffee, and many more items are traded. The country's export list includes food grains like wheat, corn, and soybean. Aeroplane, cars, computers, paper, and machine tools required for different industries. In 2016 United States current account balance was −$469,400,000,000. Relatively few US companies export; a 2009 study reported that 18% of US manufacturers export their goods. Exporting is concentrated to a small number of companies: the largest 1% of US companies that export comprise 81% of US exports Trade barriers are government-induced restrictions on international trade. Man-made trade barriers come in several forms, including: • Tariffs • Non-tariff barriers to trade • Import licenses • Export licenses • Import quotas • Subsidies • Voluntary Export Restraints • Local content requirements • Embargo • Currency devaluation • Trade restriction Most trade barriers work on the same principle–the imposition of some sort of cost on trade that raises the price of the traded products. If two or more nations repeatedly use trade barriers against each other, then a trade war results. Most trade barriers work on the same principle–the imposition of some sort of cost on trade that raises the price of the traded products. If two or more nations repeatedly use trade barriers against each other, then a trade war results. Economists generally agree that trade restrictions are detrimental and decrease overall economic efficiency. This can be explained by the theory of comparative advantage. In theory, free trade involves the removal of all such restrictions, except perhaps those considered necessary for health or national security. In practice, however, even those countries promoting free trade heavily subsidize certain industries, such as agriculture and steel. Trade restrictions are often criticized for the effect they have on the developing world. Because rich-country players set trade policies, goods, such as agricultural products that developing countries are best at producing, face high restrictions. Trade restrictions, such as taxes on food imports or subsidies for farmers in developed economies, lead to overproduction and dumping on world markets, thus lowering prices and hurting poor-country farmers. Tariffs also tend to be anti-poor, with low rates for raw commodities and high rates for labour-intensive processed goods. The Commitment to Development Index measures the effect that rich country trade policies actually have on the developing world. Another negative aspect of trade restrictions is that it would cause a limited choice of products and, therefore, would force customers to pay higher prices and accept inferior quality. In general, for a given level of protection, quota-like restrictions carry a greater potential for reducing welfare than do tariffs. Tariffs, quotas, and non-tariff restrictions lead too few of the economy’s resources being used to produce tradeable goods. An export subsidy can also be used to give an advantage to a domestic producer over a foreign producer. Export subsidies tend to have a particularly strong negative effect because in addition to distorting resource allocation, they reduce the economy’s terms of trade. In contrast to tariffs, export subsidies lead to an over allocation of the economy’s resources to the production of tradeable goods. TRADE RESTRICTION OF U.S.A Trade Impact Estimates And Foreign Barriers U.S. foreign direct investment, or U.S. electronic commerce of specific foreign trade barriers and other trade distorting practices. Where consultations related to specific foreign practices were proceeding at the time of this report’s publication, estimates were excluded, in order to avoid prejudice to these consultations. The estimates included in this report constitute an attempt to assess quantitatively the potential effect of removing certain foreign trade barriers to particular U.S. exports. However, the estimates cannot be used to determine the total effect on U.S. exports, either to the country in which a barrier has been identified, or to the world in general. In other words, the estimates contained in this report cannot be aggregated in order to derive a total estimate of gain in U.S. exports to a given country or the world. Trade barriers or other trade distorting practices affect U.S. exports to another country because they effectively impose costs on such exports that are not imposed on goods produced in the importing country. In theory, estimating the impact of a foreign trade measure on U.S. exports of goods requires knowledge of the (extra) cost the measure imposes on them, as well as knowledge of market conditions in the United States, in the country imposing the measure, and in third countries. In practice, such information often is not available. Where sufficient data exist, an approximate impact of tariffs on U.S. exports can be derived by obtaining estimates of supply and demand price elasticities in the importing country and in the United States. Typically, the U.S. share of imports is assumed constant. When no calculated price elasticities are available, reasonable postulated values are used. The resulting estimate of lost U.S. exports is approximate, depends on the assumed elasticities, and does not necessarily reflect changes in trade patterns with third countries. Similar procedures are followed to estimate the impact of subsidies that displace U.S. exports in third country markets. The task of estimating the impact of non-tariff measures on U.S. exports is far more difficult, since no readily available estimate of the additional cost these restrictions impose exists. Quantitative restrictions or import licenses limit (or discourage) imports and thus raise domestic prices, much as a tariff does. However, without detailed information on price differences between countries and on relevant supply and demand conditions, it is difficult to derive the estimated effects of these measures on U.S. exports. Similarly, it is difficult to quantify the impact on U.S. exports (or commerce) of other foreign practices, such as government procurement policies, non-transparent standards, or inadequate intellectual property rights protection. In some cases, particular U.S. exports are restricted by both foreign tariff and non-tariff barriers. For the reasons stated above, estimating the impact of such non-tariff barriers on U.S. exports may be difficult. When the value of actual U.S. exports is reduced to an unknown extent by one or more than one non-tariff measure, it then becomes derivatively difficult to estimate the effect of even the overlapping tariff barriers on U.S. exports. The same limitations apply to estimates of the impact of foreign barriers to U.S. services exports. Furthermore, the trade data on services exports are extremely limited in detail. For these reasons, estimates of the impact of foreign barriers on trade in services also are difficult to compute. With respect to investment barriers, no accepted techniques for estimating the impact of such barriers on U.S. investment flows exist. For this reason, no such estimates are given in this report. The same caution applies to the impact of restrictions on electronic commerce. The NTE Report includes generic government regulations and practices that are not specific to particular products. These are among the most difficult types of foreign practices for which to estimate trade effects. In the context of trade actions brought under U.S. law, estimates of the impact of foreign practices on U.S. commerce are substantially more feasible. Trade actions under U.S. law are generally product-specific and therefore more tractable for estimating trade effects. In addition, the process used when a specific trade action is brought will frequently make available non-U.S. Government data (from U.S. companies or foreign sources) otherwise not available in the preparation of a broad survey such as this report. In some cases, stakeholder valuations estimating the financial effects of barriers are contained in the report. The methods for computing these valuations are sometimes uncertain. Hence, their inclusion in the NTE Report should not be construed as a U.S. Government endorsement of the estimates they reflect. Technical Barriers To Trade / Sanitary And Phytosanitary Barriers with Algeria Technical Barriers to Trade Vehicles In March 2019, Algeria enacted various new safety requirements for imported vehicles, with a focus on passenger automobiles. Algerian Government officials have asserted over the last six years that these requirements apply to all vehicles, but the requirements appear to affect imported vehicles disproportionately. Under the procedures intended to enforce the requirements, all vehicles entering the country must be accompanied by a “certificate of conformity” before they are inspected by a representative of the Ministry of Industry. Algeria also requires this certificate in order for importers to obtain from a bank the letter of credit necessary to finance a vehicle importation. These restrictions remain in place even as the government has restricted the volume of automobile imports. Food Products Algeria requires imported food products to have at least 80 percent of shelf life remaining at the time of importation. All products containing pork or pork derivatives are prohibited. Sanitary and Phytosanitary Barriers The Algerian Government currently bans the production, importation, distribution, or sale of seeds that are the products of biotechnology. There is an exception for biotechnology seeds imported for research purposes. In 2020, U.S. and Algerian authorities finalized certificates for chicken-hatching eggs, day-old chicks, and bovine embryos. U.S. and Algerian veterinary authorities continue to engage in negotiations on export certificates to allow for the importation of U.S. semen, beef cattle, dairy breeding cattle, and beef and poultry, poultry meat and products. Pharmaceuticals Barriers With China For several years, the United States has pressed China on a range of pharmaceuticals issues. These issues have related to matters such as overly restrictive patent application examination practices, regulatory approvals that are delayed or linked to extraneous criteria, weak protections against the unfair commercial use and unauthorized disclosure of regulatory data, and the need for an efficient mechanism to resolve patent infringement disputes. At the December 2014 JCCT meeting, China committed to significantly reduce timeto-market for innovative pharmaceutical products through streamlined processes and additional funding and personnel. Nevertheless, time-to-market for innovative pharmaceutical products in China remains a significant concern. Another serious ongoing concern stems from China’s proposals in the pharmaceuticals sector that seek to promote government-directed indigenous innovation and technology transfer through the provision of regulatory preferences. For example, in August 2015, a State Council measure issued in final form without public comment created an expedited regulatory approval process for innovative new drugs where the applicant’s manufacturing capacity had been shifted to China. The United States has urged China to reconsider this approach. In April 2016, China’s Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) issued a draft measure that effectively would require drug manufacturers to commit to price concessions as a pre-condition for securing marketing approval for new drugs. Given its inconsistency with international regulatory practices, which are based on safety, efficacy, and quality, the draft measure elicited serious concerns from the U.S. Government and industry. Subsequently, at the November 2016 JCCT meeting, China promised not to require any specific pricing information as part of the drug registration evaluation and approval process and, in addition, not to link pricing commitments to drug registration evaluation and approval. Given China’s lack of follow through in other areas, as discussed in this report, the United States remains concerned about whether these promises will be regularly fulfilled in practice. Accordingly, the United States remains in close contact with U.S. industry and has been examining developments carefully in this area. In April 2017, in response to sustained U.S. engagement, China issued amended patent examination guidelines that required patent examiners to take into account supplemental test data submitted during the patent examination process. However, as of March 2021, it appears that patent examiners in China have been either unduly restrictive or inconsistent in implementing the amended patent examination guidelines, resulting in rejections of supplemental data and denials of patents or invalidations of existing patents on medicines even when counterpart patents have been granted in other countries. CFDA also issued several draft notices in 2017 setting out a conceptual framework to protect against the unfair commercial use and unauthorized disclosure of undisclosed test or other data generated to obtain marketing approval for pharmaceutical products. In addition, this proposed framework sought to promote the efficient resolution of patent disputes between right holders and the producers of generic pharmaceuticals. However, in 2018, CFDA’s successor agency, the State Drug Administration (SDA), issued draft Drug Registration Regulations and implementing measures on drug trial data that would preclude or condition the duration of regulatory data protection on whether clinical trials and first marketing approval occur in China. Subsequently, in August 2019, China issued a revised Drug Administration Law, followed by revised Drug Registration Regulations in January 2020. Neither measure contained an effective mechanism for early resolution of potential patent disputes or any form of regulatory data protection. Agricultural Barriers Agriculture includes animals and animal products, fishery products, plant and plant products, processed foods, and beverages. U.S. trade agreements have contributed to greater U.S. trade in many agriculture products by lowering or eliminating tariffs on products, helping to ensure that food safety standards do not create unnecessary obstacles to trade, and providing increased transparency for sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures and product standards, as well as access to dispute settlement processes. During the Uruguay Round, WTO members negotiated two agreements that primarily affect trade in agricultural products: the Agreement on Agriculture and the Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS Agreement). While the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) technically always applied to agricultural trade, it contained exceptions that limited its disciplines on agricultural trade. The Agreement on Agriculture made the GATT disciplines more effective by closing loopholes and introducing new disciplines on domestic production and agricultural trade policies that may distort global trade. U.S. FTAs build on the Agreement on Agriculture by including provisions that increase market access between parties while using mechanisms to protect import-sensitive agricultural products, such as safeguards and tariff rate quotas (TRQs). The SPS Agreement recognizes the rights of members to adopt measures necessary to protect human, animal and plant life or heath but also imposes disciplines that seek to ensure that SPS measures are not applied in a manner that would arbitrarily or unjustifiably discriminate between WTO members or act as disguised restrictions on trade. Ethical Barriers Despite international trading laws and declarations, countries continue to face challenges around ethical trading and business practices. International trade is the exchange of goods and services across national borders. In most countries, it represents a significant part of gross domestic product (GDP). The rise of industrialization, globalization, and technological innovation has increased the importance of international trade, as well as its economic, social, and political effects on the countries involved. Internationally recognized ethical practices such as the UN Global Compact have been instituted to facilitate mutual cooperation and benefit between governments, businesses, and public institutions. Nevertheless, countries continue to face challenges around ethical trading and business practices, especially regarding economic inequalities and human rights violations. There are three broad ethical frameworks that are in conflict which make answering this question difficult. The ethics of a trade war depend, in large part, upon which set of values you choose to prioritize. The prevailing view, up to the 2016 elections, drew heavily on the "democratic peace", the "great capitalist peace" and the rising GDP/democratization theses as well as the precepts of the liberal school of thought in international affairs. Interdependence between the Chinese and American economies would create conditions to prevent conflict, channel China's "rise" into the so-called "responsible stakeholder" that would shoulder more of the burden in international affairs (implicitly lessening the burden on the United States), lift people out of poverty, and set conditions for gradual, evolutionary democratization that would cement better Sino-American relations and benefit the cause both of global order and of human rights. A trade war risks all of that by incentivizing conflict and removing the linkages which might cushion tensions, and, by negatively impacting the standard of living of both Chinese and Americans who depend on the trading relationship, can be seen as unethical in that regard. A counterargument that draws on both democratic and realist critiques argues that the trading relationship has allowed a Chinese regime that is antithetical to liberal values at home and to the existing international system to acquire more power and resources, which it has used to both pursue greater capabilities to act in the world (often at odds with U.S. preferences) but also to more effectively repress its citizens at home. Disconnecting the U.S. and Chinese economies, despite the short-term pain, is ethical in the long run for removing any tacit U.S. support for China's unliberal practices at home which are at odds with American values but also to lessen the economic and technological bases from which China is emerging as a near-peer competitor to the U.S. A third view is the transactional one: does trade with China help or hurt Americans? Here, the ethical assessment is mixed, for some Americans have benefited from the relationship, while others have not. Assessment therefore is in the eye of the beholder as to whether the "right" people are being helped or hurt either by the trading relationship or by the trade war. Cultural Barriers It is typically more difficult to do business in a foreign country than in one’s home country due to cultural barriers. It is typically more difficult to do business in a foreign country than in one’s home country, especially in the early stages when a firm is considering either physical investment in or product expansion to another country. Expansion planning requires an in-depth knowledge of existing market channels and suppliers, of consumer preferences and current purchase behaviour, and of domestic and foreign rules and regulations. Language and cultural barriers present considerable challenges, as well as institutional differences among countries. With the process of globalization and increasing global trade, it is unavoidable that different cultures will meet, conflict, and blend together. People from different cultures find it hard to communicate not only due to language barriers but also because of cultural differences. In a survey of Texas agricultural exporting firms, Hollon (1989) found that from a firm management perspective, the initial entry into export markets was significantly more difficult than either the handling of ongoing export activities or the consideration of expansion to new export product lines or markets. From a list of 38 items in three categories (knowledge gaps, marketing aspects, and financial aspects) over three time horizons (start-up, ongoing, and expansion), the three problems rated most difficult were all start-up phase marketing items: • Poor knowledge of emerging markets or lack of information on potentially profitable markets • Foreign market entry problems and overseas product promotion and distribution • Complexity of the export transaction, including documentation and “red tape.” Two of these items, market entry and transaction complexity, remained problematic in ongoing operations and in new product market expansion. Import restrictions and export competition became more problematic in later phases, while financial problems were pervasive at all phases of the export operation. In the U.S., where individualism is valued above all else, the country is run from the bottom-up, perfectly exemplified by the start-up culture zeitgeist of the Silicon Valley. In China, where collectivism is valued above all else, the country is governed primarily through a top-down approach, with the government regularly doling out generous government subsidies and support. These opposing styles of governance have their upsides and downsides. With an emphasis on the individual, individual interests are put ahead of the collective, leaving room for more open conflict. As a result, it can be hard to pivot and conduct concerted pushes through government initiatives. With a top-down approach, the importance of the leaders’ competence is pronounced. If all goes well, this approach can be highly fruitful, leading to an all-in allocation of resources towards a common goal. The caveat is that this policy amplifies failed leadership, manifesting events parallel to Mao’s catastrophic Great Leap Forward. Another roadblock for the U.S. to hurdle is the stubbornness of the Chinese Politburo. Because the Chinese government extols stability and places the utmost importance on its image of legitimacy, any deal made with the U.S. won’t put them on a serious back-foot. Currently, the United States has several misgivings towards China’s trade policies. China is not doing enough to curtail intellectual property theft and is, in many cases, facilitating it. China employs a policy called Forced Technology Transfer (FTT), which forces companies to share technology for access to the Chinese market. Additionally, unfair trade practices, China’s top-down approach and generous support for domestic enterprises undermine free-market principles Technological Barriers Standards-related trade measures, known in WTO parlance as technical barriers to trade play a critical role in shaping global trade. U.S. companies, farmers, ranchers, and manufacturers increasingly encounter non- tariff trade barriers in the form of product standards, testing requirements, and other technical requirements as they seek to sell products and services around the world. As tariff barriers to industrial and agricultural trade have fallen, standards-related measures of this kind have emerged as a key concern. Governments, market participants, and other entities can use standards-related measures as an effective and efficient means of achieving legitimate commercial and policy objectives. But when standards-related measures are outdated, overly burdensome, discriminatory, or otherwise inappropriate, these measures can reduce competition, stifle innovation, and create unnecessary technical barriers to trade. These kinds of measures can pose a particular problem for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which often do not have the resources to address these problems on their own. Significant foreign trade barriers in the form of product standards, technical regulations and testing, certification, and other procedures are involved in determining whether or not products conform to standards and technical regulations. These standards-related trade measures, known in World Trade Organization (WTO) parlance as “technical barriers to trade,” play a critical role in shaping the flow of global trade. Standards-related measures serve an important function in facilitating global trade, including by enabling greater access to international markets by SMEs. Standards-related measures also enable governments to pursue legitimate objectives, such as protecting human health and the environment and preventing deceptive practices. But standards-related measures that are non-transparent, discriminatory, or otherwise unwarranted can act as significant barriers to U.S. trade. These kinds of measures can pose a particular problem for SMEs, which often do not have the resources to address these problems on their own. Arguments Against International Trade Capital markets involve the raising and investing money in various enterprises. Although some argue that the increasing integration of these financial markets between countries leads to more consistent and seamless trading practices, others point out that capital flows tend to favor the capital owners more than any other group. Likewise, owners and workers in specific sectors in capital-exporting countries bear much of the burden of adjusting to increased movement of capital. The economic strains and eventual hardships that result from these conditions lead to political divisions about whether or not to encourage or increase integration of international trade markets. Moreover, critics argue that income disparities between the rich and poor are exacerbated, and industrialized nations grow in power at the expense of under-capitalized countries. Anti-Globalization Movements The anti-globalization movement is a worldwide activist movement that is critical of the globalization of capitalism. Anti-globalization activists are particularly critical of the undemocratic nature of capitalist globalization and the promotion of neoliberalism by international institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. Other common targets of anti- corporate and anti-globalization movements include the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the WTO, and free trade treaties like the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA), the Multilateral Agreement on Investment (MAI), and the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). Meetings of such bodies are often met with strong protests, as demonstrators attempt to bring attention to the often devastating effects of global capital on local conditions. On November 30, 1999, close to fifty thousand people gathered to protest the WTO meetings in Seattle, Washington. Labour, economic, and environmental activists succeeded in disrupting and closing the meetings due to their disapproval of corporate globalization. This event came to symbolize the increased debate and growing conflict around the ethical questions on international trade, globalization and capitalization. Criticism of the Global Capitalist Economy: Demonstrations, such as the mass protest at the 1999 WTO meeting in Seattle, highlight ethical questions on the effects of international trade on poor and developing nations. The Argument for Barriers Some argue that imports from countries with low wages has put downward pressure on the wages of Americans and therefore we should have trade barriers. It is asserted that trade has created jobs for foreign workers at the expense of American workers. It is more accurate to say that trade both creates and destroys jobs in the economy in line with market forces. Economy-wide trade creates jobs in industries that have comparative advantage and destroys jobs in industries that have a comparative disadvantage. In the process, the economy’s composition of employment changes; but, according to economic theory, there is no net loss of jobs due to trade. Over the course of the last economic expansion, from 1992 to 2000, U.S. imports increased nearly 240%. Over that same period, total employment grew by 22 million jobs, and the unemployment rate fell from 7.5% to 4.0% (the lowest unemployment rate in more than 30 years.). Foreign outsourcing by American firms, which has been the object of much recent attention, is a form of importing and also creates and destroys jobs, leaving the overall level of employment unchanged. There is no denying that with international trade there will be short-run hardship for some, but economists maintain the whole economy’s living standard is raised by such exchange. They view these adverse effects as qualitatively the same as those induced by purely domestic disruptions, such as shifting consumer demand or technological change. In that context, economists argue that easing adjustment of those harmed is economically more fruitful than protection given the net economic benefit of trade to the total economy. Many people believe that imports from countries with low wages has put downward pressure on the wages of Americans. There is no doubt that international trade can have strong effects, good and bad, on the wages of American workers. The plight of the worker adversely affected by imports comes quickly to mind. But it is also true that workers in export industries benefit from trade. Moreover, all workers are consumers and benefit from the expanded market choices and lower prices that trade brings. Yet, concurrent with the large expansion of trade over the past 25 years, real wages (i.e., inflation adjusted wages) of American workers grew more slowly than in the earlier post-war period, and the inequality of wages between the skilled and less skilled worker rose sharply. Was trade the force behind this deteriorating wage performance? Some industries, or at least components of some industries, are vital to national security and possibly may need to be insulated from the vicissitudes of international market forces. This determination needs to be made on a case-by-case basis since the claim is made by some who do not meet national security criteria. Such criteria may also vary from case to case. It is also true that national security could be compromised by the export of certain dualuse products that, while commercial in nature, could also be used to produce products that might confer a military advantage to U.S. adversaries. Controlling such exports is clearly justified from a national security standpoint; but, it does come at the cost of lost export sales and an economic loss to the nation. Minimizing the economic welfare loss from such export controls hinges on a well- focused identification and regular reevaluation of the subset of goods with significant national security potential that should be subject to control. The Argument Against Barriers Economists generally agree that trade barriers are detrimental and decrease overall economic efficiency. Most trade barriers work on the same principle: the imposition of some sort of cost on trade that raises the price of the traded products. If two or more nations repeatedly use trade barriers against each other, then a trade war results Economists generally agree that trade barriers are detrimental and decrease overall economic efficiency, this can be explained by the theory of comparative advantage. In theory, free trade involves the removal of all such barriers, except perhaps those considered necessary for health or national security. In practice, however, even those countries promoting free trade heavily subsidize certain industries, such as agriculture and steel. International trade: International trade is the exchange of goods and services across national borders. In most countries, it represents a significant part of GDP. Trade barriers are often criticized for the effect they have on the developing world. Because rich-country players call most of the shots and set trade policies, goods, such as crops that developing countries are best at producing, still face high barriers. Trade barriers, such as taxes on food imports or subsidies for farmers in developed economies, lead to overproduction and dumping on world markets, thus lowering prices and hurting poor-country farmers. Tariffs also tend to be anti-poor, with low rates for raw commodities and high rates for labour-intensive processed goods. If international trade is economically enriching, imposing barriers to such exchanges will prevent the nation from fully realizing the economic gains from trade and must reduce welfare. Protection of import-competing industries with tariffs, quotas, and non-tariff barriers can lead to an over-allocation of the nation’s scarce resources in the protected sectors and an under-allocation of resources in the unprotected tradeable goods industries. In the terms of the analogy of trade as a more efficient productive process used above, reducing the flow of imports will also reduce the flow of exports. Less output requires less input. Clearly, the exporting sector must lose as the protected import-competing activities gain. But, more importantly, from this perspective the overall economy that consumed the imported goods must also lose, because the more efficient production process–international trade–cannot be used to the optimal degree, and, thereby, will have generally increased the price and reduced the array of goods available to the consumer. Therefore, the ultimate economic cost of the trade barrier is not a transfer of well-being between sectors, but a permanent net loss to the whole economy arising from the barriers distortion toward the less efficient the use of the economy’s scarce resources. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) is an agreement signed by the governments of Canada, Mexico, and the United States, creating a trilateral trade bloc in North America. The agreement came into force on January 1, 1994. It superseded the Canada – United States Free Trade Agreement between the U.S. and Canada. In terms of combined GDP of its members, the trade bloc is the largest in the world as of 2010. NAFTA has two supplements: the North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation (NAAEC) and the North American Agreement on Labour Cooperation (NAALC). The goal of NAFTA was to eliminate barriers to trade and investment among the U.S., Canada, and Mexico. The implementation of NAFTA on January 1, 1994 brought the immediate elimination of tariffs on more than one-half of Mexico’s exports to the U.S. and more than one-third of U.S. exports to Mexico. Within 10 years of the implementation of the agreement, all U.S.–Mexico tariffs would be eliminated except for some U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico that were to be phased out within 15 years. Most U.S.–Canada trade was already duty free. NAFTA also seeks to eliminate non-tariff trade barriers and to protect the intellectual property right of the products. The agreement opened the door for open trade, ending tariffs on various goods and services, and implementing equality between Canada, America, and Mexico. NAFTA has allowed agricultural goods such as eggs, corn, and meats to be tariff-free. This allowed corporations to trade freely and import and export various goods on a North American scale. BIBLIOGRAPHY WEB LINKS: General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/General_Agreement_on_Tariffs_and_Trade. tariff. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/tariff. multilateral. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/multilateral WTO2005. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WTO2005.png. EU. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/EU. transparency. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/transparency. euro. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/euro. European Union. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/European_Union. WTO2005. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WTO2005.png European Union. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:European_Union.svg. Nafta. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nafta. tariff Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/tariff. trade bloc. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/trade%20bloc. free trade. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/free_trade. WTO2005. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WTO2005.png. European Union. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:European_Union.svg North American Agreement (orthographic projection). Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:North_American_Agreement_(orthographic_projection).svg. Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AsiaPacific_Economic_Cooperation Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AsiaPacific_Economic_Cooperation. bloc. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/bloc. WTO2005. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WTO2005.png. European Union. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:European_Union.svg. North American Agreement (orthographic projection). Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:North_American_Agreement_(orthographic_projection).svg https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-business/chapter/international-trade-agreements-andorganizations/ https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=bb099306-c121-4b62-ab90-69c254beba38 https://www.investopedia.com/articles/economics/08/tariff-trade-barrier-basics.asp https://www.carnegiecouncil.org/publications/articles_papers_reports/ethical-considerations-in-a-trade-warwith-china https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/reports/2021/2021NTE.pdf