Systems Engineering: Conceptual Design - Capability Gaps

advertisement

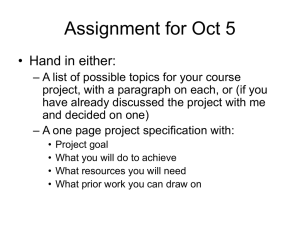

SYSTEMS ENGINEERING MOOC 5 – CONCEPTUAL DESIGN PART 1 For organisations to be successful in whatever their endeavours, they need to be actively involved in thinking both operationally and strategically. Operational thinking allows them to continue day to day, or business as usual operations in a smooth, efficient and effective manner. Operational thinking does not necessarily allow organisations to consider the longer term direction that the organisation should take in conducting business. Nor does it allow the organisation to maintain an awareness of longer term opportunities and threats. For this view, organisations need to think strategically. In some cases, organisations uncover gaps in their current capability that will impact on their ability to move in the desired strategic direction. These capability gaps may be critically important to the organisation. Some capability gaps will prevent an organisation from achieving the strategic objectives that have been established, with resultant long term consequences. The gaps may result in opportunities that the organisation is unable to exploit. The gaps may open vulnerabilities to threats from competition or adversaries. Capability gaps come in an endless variety of shapes and sizes. If I consider my own life, I have plenty of capability gaps. For example, I would love to be able to surf at the beaches near my home but I am unable to do this currently. I don’t currently own a surfboard, I don’t currently have roof-racks on my car and I don’t currently have the necessary skills to stand on a surfboard. I clearly have a serious capability gap. 1 On a more serious note, I know of commercial organisations who have identified niches in their markets but lack the ability to be able to exploit those niches. Their capability gap is in the form of a lack of people, processes and tools to perform product development in order to address those niches with marketable solutions. On a larger scale, some Governments around the country would like to plug gaps in Governmentprovided services such as health services for disadvantaged people, or transportation services for particular regional areas. Some military organisations around the world may want to be able to monitor their national boarders but currently lack the capability to do this to a desired level. Once business stakeholders become aware of critical capability gaps and commit to either closing or reducing those gaps, they are establishing the need for a solution. Naturally organisations will probably not be able to address all of the gaps in their capability. They will need to prioritise the gaps and concentrate on addressing the most critical gaps first. Establishment of a need for a solution marks the start of the systems engineering lifecycle and indeed the start of what we call the Conceptual Design phase of that lifecycle. We typically address these capability gaps in a methodical manner. We start by concentrating on the business or organisational needs and what the resultant requirements for the eventual solution might be. Business needs and requirements are, after all, what we are trying to address so understanding these [are] a logical starting point. We then have a look at what the relevant stakeholders within the business would like to achieve. These stakeholders will be people who are involved with the business or organisation in the areas where the need exists. They will have particular views on what is required by the eventual solution also. We then move onto what some people consider to be the start of traditional systems engineering where we take the business and stakeholder needs and 2 develop a formal understanding of the system-level requirements that our potential solutions must meet if they are to satisfy stakeholder and business needs. An understanding of system level requirements allows us to take a detailed look at the potential system level solutions that may exist. We will be interested in knowing what level of compliance these solutions will exhibit, what options the solutions come with, how much they costs and how long they will take to realise. We will also be interested in the risks associated with each solution and longer term issues such as sustainment and disposal. This will allow us to select a preferred system level solution. This process is sometimes referred to as system level synthesis to give the feeling of evolving design. The term synthesis has its roots in Latin and, before that Greek, meaning to “place together”. The need to stop our work periodically and check that we are on the right path is almost so obvious that it goes without mention, but in this MOOC we will mention it anyway. Once we have done all of this work with our business stakeholders and think we are ready to move on to solving their business needs, we will draw breathe and have a look at what we have achieved. This will give everyone a chance to review the work, look at the problem space that we have defined, look at the preferred system level solution we have selected and confirm that we are ready to move on to the next stage. We call this review a system design review because, well, that’s what it is. A review of the system level requirements and the system level solution to ensure that the two are appropriately understood and appropriated matched before proceeding. Let’s take a look at each of these 5 steps in order to gain a better appreciation of what is going on. Let’s assume that the business stakeholders have selected a capability gap for reduction or closure, there is plenty of work for them to do in order to start addressing this gap. Let’s look quickly at what needs to be done in order to define the business needs and requirements and we will then look at each of these areas in more detail. Firstly, the business needs to determine which organisational stakeholders will be given responsibility for identifying the business needs and requirements associated with the gap. These major business stakeholders will then be tasked with identifying the constraints associated with situation. Constraints can take many forms but 3 invariably exist and limit the options open to the organisation in terms of the ultimate solution to their business needs. Stakeholders are then able to develop a more thorough understanding of the business needs that must be addressed by the system by exploring the missions, goals and objectives that the solution must address. Systems rarely sit in a perfectly isolated situation, so it is critical also to understand where the system sits in relation to its environment and other external systems. This allows the stakeholders to understand and articulate the scope of the system. That is, what is considered in-scope, or part of the system and what is considered to be beyond the scope of the system. This activity also allows stakeholders to start to understand the potentially numerous interfaces with the external environment that will need to exist. This information will allow stakeholders to look at feasible alternative solutions and extract more formal business requirements associated with the capability gap. These business requirements will be more formally stated than the needs. Whilst the needs paint a picture of the problem and desired solution, the resultant business requirements are a further decomposition of the needs so that we can understand exactly what the business requires of the ultimate solution when it is deployed. When this work is complete, it is generally documented and reviewed by the business in order to endorse the work as representing what is required. This could be thought of as a formal approval process to allow the business needs and requirements to be used as the basis of the subsequent systems engineering effort. Let’s look at these steps in more detail. The business needs to identify the people who will be able to execute the process described earlier. The people will be selected because they are either affected by the system in some way or can affect the system in some way. Selection of the correct stakeholders is an important first step because they will shape the system to come. Not everyone who is affected by or has an affect on the system will be considered stakeholders. This list would be far too large to be useful. The business needs to restrict the stakeholders to those who are considered to have a right to affect the system. 4 Examples of typical stakeholders might include representatives from management who are directly impacted by the system or the need that the system is being designed to satisfy. Engineering and technical people who will be responsible for design, development, testing and acceptance activities associated with the system may also be considered key stakeholders. Maintenance and logistics personnel who will be responsible for sustaining the system (and ultimately disposing of the system) will have a direct interest in forming the requirements for the system. In this way, the compelling metrics of lifecycle cost can be taken into account. Also, the people who will use the system or benefit from the system will typically be represented in the key stakeholder group. These stakeholders will have plenty of work to do in the early stages of conceptual design. One of the things we need to understand as early as possible is the presence of constraints on the system. These constraints will be imposed on the system by virtue of circumstance and will effectively limit options associated with the system. If the system is not designed with these constraints in mind, it may fail to operate correctly when the constraints are imposed on it and therefore fail to deliver the results expected from it. Examples of constraints include business constraints like policies, procedures, standards, or existing relationships or contracts. Project constraints such as budget and schedule limits will impact on the options available. External constraints that are beyond the control of the organisation may also need to be identified and considered. Examples may include laws and regulations, and the availability of skilled workforces. Finally, there may be some designrelated constraints that need to be identified and considered. Examples may include technology stability and availability, design tool availability, and production and construction capabilities or limitations. 5 Once we have the right stakeholders on board and we understand the constraints under which we are operating, the stakeholders are able to start working on developing an appreciation of the business needs that are driving the requirement for a new system. A good starting point in any development of needs is to look at the mission of the system. This should be a concise statement, maybe only a sentence or two long, that captures essence of the system. Once captured, the mission is generally explained and expanded on by a series of goal statements that relate to the mission. From the goals will come objectives that will help describe what the system needs to be able to achieve. In this way, we end up with a hierarchical structure where the mission spawns a number of goals which, in turn, spawn a number of objectives. Another valuable exercise for the stakeholders to undertake is the development of short stories or descriptions of how the system will be used to solve the business need. These stories or descriptions are often called scenarios and allow stakeholders to paint a picture of the system and its use. Scenarios help develop an understanding of the importance of the operational and support environment, the various actors that will be involved with the system, the many external systems that may interact with the system, and the types of things that may go wrong when the the system is being used. Scenarios may be developed using common tools like functional flow block diagrams, drawings, illustrations, simulations and models….whichever is the most effective way of describing how the system will be used. Whilst stakeholders are busy developing scenarios that describe how the system will be used and supported, they should also be thinking about how the effectiveness of the system in meeting business needs is going to be confirmed. Convincing sets of stakeholders that their expectations of the system have been satisfied is often referred to as validation. Determining the top level validation criteria is therefore something that needs to be done whilst engaging with the relevant stakeholders. Knowing how a system is going to be validated by the groups of stakeholders is something that will impact on the development of subsequent business, stakeholder and system level requirements via a hierarchy of measures of effectiveness, measures of performance and related requirements verification statements. Finally, to complete the elicitation of business needs, stakeholders should define any important lifecycle concepts associated with the system. 6 Some of these concepts will be supported by the scenarios that have already been developed but it is important for business stakeholders to explain their concepts, thoughts, and expectations in relation to: - How the system will be operated (sometimes called an Operational Concept or OpsCon) - How the system will be acquired (called an acquisition concept covering things like the expected use of contractual models arrangements and so on) - How the system will be deployed or transitioned from the acquisition phase to the utilisation phase - How the system will be supported during the utilisation phase including ideas for contracted support versus in house support and so on - And how the system will ultimately be disposed of including expectations, constraints or requirements associated with disposal. Whilst we are working on our basic business needs, we will also be developing a much better understanding of the scope of our system. We are looking to understand the context of our system (in terms of its environment and external systems), define the boundary of our system (that is, where our system begins and ends in terms of its environment and external systems) and therefore what external interfaces exist between our system and the external systems in our environment. The context of our system in terms of how it sits within its environment and external systems is often explained with a diagram called, not surprisingly, a context diagram. We have included a simple context diagram for a domestic burglar alarm system to give you an idea of what we are talking about. We can see here that if we are developing an alarm system for our house, it does not sit in isolation. It sits and operates within an existing and surprisingly complicated environment. Largely it sits within our house but in doing so may interact with intruders as well as us. It will probably interact also with our home’s power system and the telephone network that connects our house to the outside world (on our diagram we have shown this as the standard public switched telephone network or PSTN). This might be mandated by a key stakeholder for some reason. Of course if this we not mandated we would be more general and leave the nature of that connection up to the designers in order to explore more modern options for connecting our alarm to the monitoring 7 agent. But, in keeping with the idea that a picture paints a thousand words, you get the picture about a context diagram. The context diagram also helps clarify the boundary between our system and the external systems. For example, we are not responsible for power to the system. The power distribution subsystem in our house is responsible for that. This boundary will probably constrain our options but it represents a boundary between our responsibilities and those of an external system such as the power subsystem. Also shown on the context diagram are some external interfaces (listed in red from E01 to E10). This allows us to start highlighting interfaces that need to exist across our system boundary in order for our system to work properly. Sometime our system will be responsible for providing something to an external system. For example, E05 and E06 involve the interface between the alarm and the telephone network. The alarm system will be responsible for achieving certain functions in order to interface with the PSTN in order to alert the monitoring agent of alarm operation. One interface may be to provide continuous status information to the agent whilst another interface may be responsible for alerting the monitoring agent to the presence of an alarm event caused by an intruder. Sometimes, our system will expect certain things from external systems via an interface. For example, E03 is an interface where our system will expect to get single phase, 240V AC power at 50 Hz frequency over a standard powerpoint. These interfaces are important to us because we need to make sure that the external system with whom we are interfacing does, in fact, support the interface we are expecting. PART 2 It is now time to translate the business needs into more formal business requirements. Whilst undertaking this process, stakeholders are also required to look at the feasible alternatives associated with closing the capability gap. Feasibility assessment will allow the stakeholders to concentrate their efforts on defining business requirements around the most feasible solution space. Note that they have not chosen or defined the solution at this stage but have merely assessed the 8 most likely solution option when looking at requirements. This avoids wasted effort and also focuses the business requirements, making them more useful in the following stages. For example, earlier I mentioned an example of a military capability gap associated with monitoring national boarders. The likely options for doing this (that is the possible solution spaces) may include satellite surveillance, surveillance from unmanned aerial vehicles, surveillance from manned aircraft, or surveillance from warships. These may all be technically feasible but the business needs and constraints are likely to rule some options out. For example, we may not have the money or time to establish a satellite-based system. We may not have the manpower or desire to establish warship capability. The feasible options may be limited to either manned or unmanned aircraft. The stakeholders responsible for extracting business requirements should therefore concentrate on the feasible solution spaces only. These business requirements will be more formally stated than the needs and will eventually guide the development of engineering requirements for our system. Whilst the business needs paint a picture of the problem and desired solution, the resultant business requirements are a further decomposition of the needs so that we can understand exactly what the business requires of the ultimate solution when it is deployed. We will capture these requirements in a structured (organised) artefact that we call the Business Requirements Specification or BRS. Once the business requirements are established in the context of the business needs, the stakeholders can document and record all of the information. We are going to propose recording all of this information in the form of an artefact that we call the Business Need and Requirements which consists of a preliminary Lifecycle Concept Document or PLCD and a Business Requirements Specification or BRS Once produced and updated, we will conduct some form of requirements review with key stakeholders and organisational decision makers to review and agree to the PLCD and the BRS. That will then allow us to pass this information onto groups of more operationally focussed stakeholders for refinement and further development. 9 We have endorsed Business Needs and Requirements from the previous work. This shows that management are confident that there is a need existing for a new or improved system and that they understand those needs sufficiently to move on with the process. We have a preliminary lifecycle concept document that describes all of the lifecycle concepts (including concepts of acquisition, operation, support and disposal) and we have a Business Requirements Specification that define the agreed business requirements for the system. We now look to build on this work by using selected groups of more operationally focussed stakeholders. These stakeholders are more on “the coal face” so to speak and are able to look over the Business Needs and Requirements and give them a more refined feel. To acknowledge the refinement process, we are going to call the resultant work the Stakeholder Needs and Requirements. In performing this work, the operational stakeholders will look over all of the previous work including the mission, goals and objectives, the scenarios and the lifecycle concepts. They may develop more refined scenarios that are sometimes called vignettes to capture more detail and operational nuances. They will also refine the validation criteria in order to communicate how stakeholders could be convinced that their expectations have been met. They will refine the Preliminary Lifecycle Concept Document into the initial Lifecycle Concept Document or LCD and they will further develop the Business Requirements Specification into a Stakeholder Requirements Specification or StRS. In some cases, the refinement may be minor but in other cases the LCD and StRS may represent quite substantial developments. Regardless, we will finalise their effort by reviewing the LCD and StRS via another requirements review. Armed with endorsed Lifecycle Concepts in the LCD and endorsed Stakeholder Requirements in the StRS, we are in a position to embark on a major systems engineering task within conceptual design. This task is generally dominated to a system level requirements analysis. As an introduction to this process, I need to warn you that performing requirements analysis and writing effective system level requirements is a tough job. It is a job for a team of people because more heads are better than one. It is a job for experienced people because practice makes perfect (although you will 10 find perfection difficult to come by in the requirements analysis space) and it is a job that requires iterations, reviews and rework. We are aiming to describe what the system must be able to do in order to satisfy the stakeholder requirements in the StRS. We try to avoid specifying how the system should be designed at this stage. If we start specifying the design at this stage, we risk overlooking innovative ways of solving the problem. We also risk taking responsibility for a design that simply doesn’t work. We should specify what we want the system to do and leave the design to the experts we engage to perform preliminary and detailed design later in the process. We will record the system-level requirements in an artefact that we will call the System Requirements Specification (SyRS). As we are drafting this artefact, we establish and maintain traceability from our system requirements back to the Stakeholder requirements to ensure that everything we specify has a reason for being there. We also trace from the Stakeholder requirements forward to the systemlevel requirements to ensure that we have addressed all of the stakeholder requirements. Traceability (forwards and backwards) between different levels of the requirements hierarchy is a cornerstone of requirements engineering. In this case, it is traceability between the stakeholder and systemlevel requirements that is of interest. Later the traceability of interest will be between the systemlevel requirements and the lower level design requirements of our solution. A useful starting point for our requirements definition effort is to establish a requirements framework or breakdown structure. We have probably already established a requirements breakdown structure in the previous process where we were looking at the Stakeholders Requirement Specification. If already established, we can review, refine and reuse the structure. It not established already, then now is the time to get one in place. An example of an RBS for a burglar alarm is illustrated. The structure will help us when performing requirements work because it will allow teams of people to be working on the task at the same time without duplicating effort. For example, we could have one team or person looking at our detection requirements (under heading 2) whilst another team or person is looking at reporting requirements under 11 section 4. The RBS provides a common framework against which different teams of people can have discussions and it will provide a common framework against which requirements can be allocated when the time comes. This will allow similar requirements to be grouped and allocated to single sections of the framework (assisting in correcting conflicting requirements) and guarding against duplication or omission of requirements. We then start performing our system level requirements analysis. We are looking to answer some fundamentals questions about our system: -What does the system need to be able to do? This is where our functional requirements help. Functional requirements define what the system needs to be able to do. -How well does the system need to be able to perform those functions. Performance requirements associated with our functional requirements define performance levels -What other characteristics are required of our system? These are typically emergent properties (or non-functional requirements) associated with our system. These might include factors like reliability, useability or maintainability as examples. -What other systems are involved with the system? We may need to define external interface requirements (probably specialised examples of functional requirements) associated with our system -Under what conditions is our system expected to operate? We also need to be able to define how we are going to verify our system performance against these requirements. It is important to note that verification is a term in systems engineering meaning to confirm system performance against specified requirements. Recall that we have used validation in previous discussions to mean confirmation that our stakeholders have been satisfied. Often, people use the two terms interchangeably - which is incorrect. Also people often combine the terms and describe a process as being “V&V”. Unless the acronym “V&V” is used carefully, it may also be used incorrectly. If we are talking about confirming a system against a specified requirement, we are talking about verification. Establishing verification requirements at the same time as writing the functional/nonfunctional requirements statements is considered to be good requirements writing practice. It forces the author of the requirement to ask “how would I confirm this requirement?” It often highlights 12 problems with the requirements statement and forces the author to revise the statement in order to make it more verifiable. This is a worthwhile exercise. While we are writing our requirements, it is also recommended to allow authors to record rationale or notes associated with each requirement. This allows the author to explain the background to the requirement for future reference. Traceability may provide some rationale for the requirement but may not be enough to explain why a requirement exists. Rationale may protect requirements from being changed in the future without due consideration as to why the requirement was there in the first place. I can given an example of where I have benefited in the past from recording rationale. I remember being responsible for writing requirements for a large project a number years ago. One day, 5 years after finishing my task, I received a phone call from someone on the project asking why I had assigned specific performance levels against some requirements. The caller said that I had recorded a rationale pointing to a meeting I had had with air traffic controllers relating to controlling aircraft in tight formation. Once I was reminded of the rationale (the meeting), I was able to explain exactly why the requirements were written the way they were and who the caller should refer to for further information. In the absence of this rationale, I think I would have struggled to recall why the requirement was written that way. It is possible that the requirement would have been changed with possible adverse consequences on the relevant stakeholders (in this case, the air traffic controllers). Once the requirements have been written, they are re-read and analysed against the parent stakeholder requirements to ensure that they are of adequate depth and detail. Further detail or breakdown occurs if required. The requirements are then allocated to one of the locations in the requirements breakdown structure. We look at the requirements breakdown structure and work out where within the structure the requirement best fits. If it turns out that the requirement could reside in more than one location in the structure, we make a decision, record it once and then refer to it from the other locations. Duplicating and repeating requirements is considered bad practice and will result in potential conflict and confusion in the future especially if requirements change. 13 We now have our requirements in a structured form that we will call a System Requirements Specification (SyRS). This may be a physical document, it may be a spread sheet or it may be in the form of a structured and populated database. It could even be in the form of a model of the desired system that is able to illustrate the system requirements via simulation. There are plenty of reference sources around that explain what structure and content should be used for this level of specification. Its form is not as important as its existence. It is only a draft at the moment because we are likely to categorise our requirements as mandatory, important or desirable. For example, we may have a functional requirement associated with detection range for our burglar alarm and we might have three levels of performance. We might say that the alarm needs to be able to detect a 80 kg human under certain environmental conditions from 10 m (mandatory), 12 m (important) and 15 m (desirable). This allows us some flexibility in expressing our requirements and also allows us to assess the value of different solutions when we look at possible solutions in the next stage. Whilst this concept helps us at the moment, we will not leave those levels in the final specification. We will replace those levels with the agreed level that the selected solution claims to be able to achieve. We have been doing a lot of work in order develop and document the system level requirements. As discussed earlier, is seems like common sense that we would review our work before proceeding. This is certainly the case with our requirements. Unimaginatively, we are going to call these reviews system requirements reviews or SRRs. Sometimes, if we are dealing with a straightforward situation, we might only conduct single SRR for our system. But, in all likelihood, a single review won’t be sufficient. We will probably conduct a series of reviews in a work-review-rework cycle until we are happy with our set of requirements. This idea of a series of reviews leading to a complete and agreed set of requirements is illustrated. Either way, once we have completed our SRR process, we are ready to move onto our system level synthesis. 14 The draft SyRS is sent to potential solution providers. These may be external organisation or may be inhouse solution providers. These providers will review the specification and try to match it to what they can offer in the form of a solution. They also note any differences between their potential offer and the draft SyRS Differences might be discrepancies or noncompliances or they might be additional functions or enhanced performance levels that the proposed solution will offer. In most cases, solution providers will propose a revision of the draft SyRS to make it better align with their proposed solution. Potential solution providers also advise the acquirer of their solution, the cost and schedule associated with its delivery, and the proposed revision to the SyRS. The acquirer considers all of these “offers” from different suppliers before making a decision about which way they are going to proceed. It is normal to conduct a period of negotiation and offer definition with the preferred supplier so that both the acquirer and supplier are very clear about what is required and what is being offered (including how the system is going to be verified by the customer prior to acceptance). The SyRS will be a very important part of these discussion and by the end of the discussions, the specification needs to be refined and agreed and needs to unambiguously define the what, how well, etc etc of the proposed solution. The draft SyRS is sent to potential solution providers. These may be external organisation or may be inhouse solution providers. These providers will review the specification and try to match it to what they can offer in the form of a solution. They also note any differences between their potential offer and the draft SyRS Differences might be discrepancies or noncompliances or they might be additional functions or enhanced performance levels that the proposed solution will offer. 15 In most cases, solution providers will propose a revision of the draft SyRS to make it better align with their proposed solution. Potential solution providers also advise the acquirer of their solution, the cost and schedule associated with its delivery, and the proposed revision to the SyRS. The acquirer considers all of these “offers” from different suppliers before making a decision about which way they are going to proceed. It is normal to conduct a period of negotiation and offer definition with the preferred supplier so that both the acquirer and supplier are very clear about what is required and what is being offered (including how the system is going to be verified by the customer prior to acceptance). The SyRS will be a very important part of these discussion and by the end of the discussions, the specification needs to be refined and agreed and needs to unambiguously define the what, how well, etc etc of the proposed solution. Once we have a solid understanding of our requirements (via the SyRS) and we have selected and negotiated a preferred solution via system level synthesis, we conduct a system level design review to confirm that we are ready to move onto preliminary design. Not surprisingly, we call this a System Design Review or SDR. During SDR, we will investigate: - the proposed solution - the refined SyRS -the traceability back to the Stakeholder Requirements Specification (StRS) and -the planning that has been put in place to execute and manage the technical program Like all of our reviews, we need to run the SDRlike a professional technical meeting. This means that we need to establish an agenda, nominate a chairperson(s) and secretary, take minutes and action items, and then follow those up following the meeting. Once complete to the satisfaction of acquirer, we are ready to move onto the next stage of the process. 16