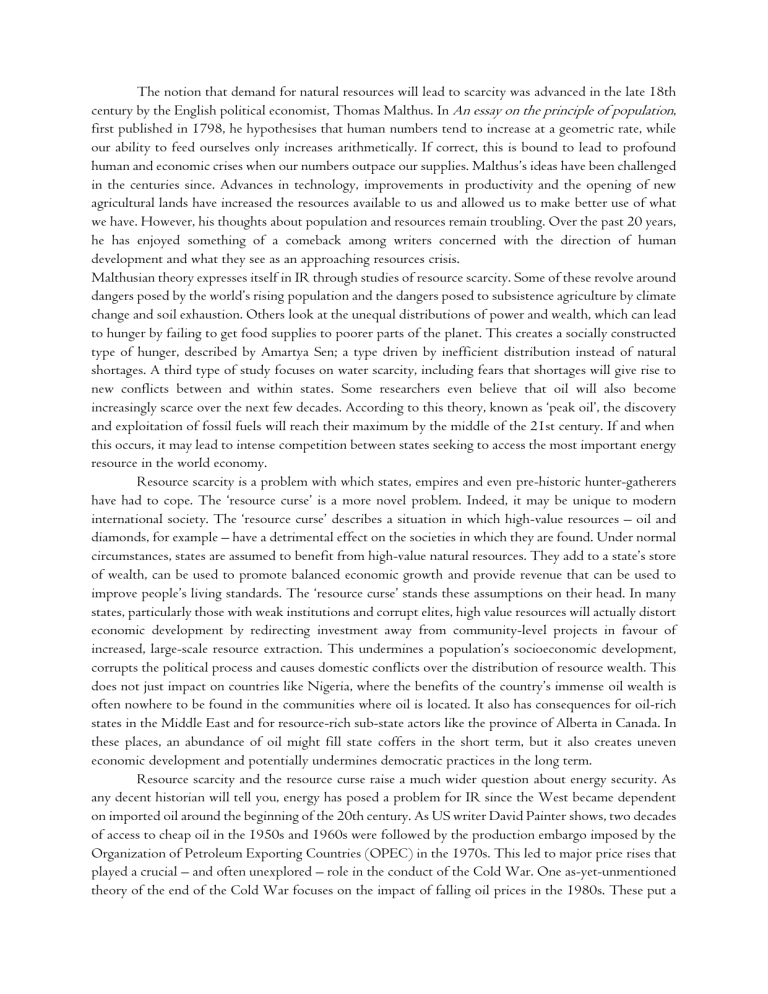

The notion that demand for natural resources will lead to scarcity was advanced in the late 18th century by the English political economist, Thomas Malthus. In An essay on the principle of population, first published in 1798, he hypothesises that human numbers tend to increase at a geometric rate, while our ability to feed ourselves only increases arithmetically. If correct, this is bound to lead to profound human and economic crises when our numbers outpace our supplies. Malthus’s ideas have been challenged in the centuries since. Advances in technology, improvements in productivity and the opening of new agricultural lands have increased the resources available to us and allowed us to make better use of what we have. However, his thoughts about population and resources remain troubling. Over the past 20 years, he has enjoyed something of a comeback among writers concerned with the direction of human development and what they see as an approaching resources crisis. Malthusian theory expresses itself in IR through studies of resource scarcity. Some of these revolve around dangers posed by the world’s rising population and the dangers posed to subsistence agriculture by climate change and soil exhaustion. Others look at the unequal distributions of power and wealth, which can lead to hunger by failing to get food supplies to poorer parts of the planet. This creates a socially constructed type of hunger, described by Amartya Sen; a type driven by inefficient distribution instead of natural shortages. A third type of study focuses on water scarcity, including fears that shortages will give rise to new conflicts between and within states. Some researchers even believe that oil will also become increasingly scarce over the next few decades. According to this theory, known as ‘peak oil’, the discovery and exploitation of fossil fuels will reach their maximum by the middle of the 21st century. If and when this occurs, it may lead to intense competition between states seeking to access the most important energy resource in the world economy. Resource scarcity is a problem with which states, empires and even pre-historic hunter-gatherers have had to cope. The ‘resource curse’ is a more novel problem. Indeed, it may be unique to modern international society. The ‘resource curse’ describes a situation in which high-value resources – oil and diamonds, for example – have a detrimental effect on the societies in which they are found. Under normal circumstances, states are assumed to benefit from high-value natural resources. They add to a state’s store of wealth, can be used to promote balanced economic growth and provide revenue that can be used to improve people’s living standards. The ‘resource curse’ stands these assumptions on their head. In many states, particularly those with weak institutions and corrupt elites, high value resources will actually distort economic development by redirecting investment away from community-level projects in favour of increased, large-scale resource extraction. This undermines a population’s socioeconomic development, corrupts the political process and causes domestic conflicts over the distribution of resource wealth. This does not just impact on countries like Nigeria, where the benefits of the country’s immense oil wealth is often nowhere to be found in the communities where oil is located. It also has consequences for oil-rich states in the Middle East and for resource-rich sub-state actors like the province of Alberta in Canada. In these places, an abundance of oil might fill state coffers in the short term, but it also creates uneven economic development and potentially undermines democratic practices in the long term. Resource scarcity and the resource curse raise a much wider question about energy security. As any decent historian will tell you, energy has posed a problem for IR since the West became dependent on imported oil around the beginning of the 20th century. As US writer David Painter shows, two decades of access to cheap oil in the 1950s and 1960s were followed by the production embargo imposed by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in the 1970s. This led to major price rises that played a crucial – and often unexplored – role in the conduct of the Cold War. One as-yet-unmentioned theory of the end of the Cold War focuses on the impact of falling oil prices in the 1980s. These put a major squeeze on the troubled Soviet economy, which received most of its foreign currency from exports of oil and gas, eventually pushing it into bankruptcy and political collapse. One factor above all has pushed energy to the top of a very long list of non-military security issues: the terrorist attacks on the USA in September 2001. These events changed the way that US citizens thought about the world. Overnight, it seemed that the country had become too dependent on Middle Eastern oil. It was at this crucial juncture, when fear ran headlong into the USA’s long-standing relationship with Saudi Arabia – which possesses over 25 per cent of the world’s known oil reserves – that the US debate about energy security began in earnest. Even President G.W. Bush, an experienced operator in the oil industry, began to muse that it was high time for the USA to find alternative sources and forms of energy. Given the depth of their commercial links and the size of Saudi reserves, there was never much chance that the USA was going to abandon Saudi Arabia completely. Nevertheless, the question had been asked and a code of silence had been broken. We will have to wait to see how the USA – and the West more generally – will try to achieve energy security without becoming ever more deeply embroiled in the unstable regional politics of the Middle East. One surprising change has been the rapid rise in US oil and gas production thanks to hydraulic fracturing – a controversial technique for accessing hard-to-reach supplies underground. This has seen the USA go from the largest net importer of oil to a potential exporter, radically redrawing the world’s energy map.