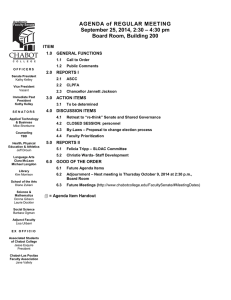

Architecture as a means of conveying emotions Laurent Khuat Duy 0876821 Philosophy in Architecture (7X700) dr. J.C.T. Voorthuis 26/11/2013 been countless times witnessed empirically. Suffice it to mention the number of people who, every year, come to Paris to “see the Eiffel Tower”, or fly to Bilbao to “experience the Guggenheim”. They go there to see something new, something that will make them live and adventure with memorable emotions. The perfection Do you really think such a beauty exists? A work of architecture that would universally be recognized as beautiful, a design that would automatically put a smile on the face of its visitors or owners? What is interesting is to understand how a building triggers emotions in an individual. Besides their traditional sheltering function, buildings speak. Alain de Botton (2006) adds that the buildings invite, rather than force, people to share their lifestyle. In fact, it is not solely the visual aspect of a building that makes it attractive, but also the values it conveys. This is a very strong idea: it means that if we find a building beautiful, it might not be because of its visual appearance, but rather for what it symbolizes. As a consequence, there can be as many visions of beauty as there exist visions of happiness. If yes, think twice. « Those who have made architectural beauty their life’s work know only too well how futile their efforts can prove ». It is in these words that Alain de Botton (2006, p. 1718) describes the vain effort of architects that believe they can enforce happiness by the sole beauty of their designs. He adds: “Not only do beautiful houses falter as guarantors of happiness, they can also be accused of failing to improve the characters of those who live in them.” Is then architecture as a means to influence people’s behavior a chimera? I don’t believe so. This is what I will demonstrate, as we explore the question of how can architecture be used to create strong emotions, and how is this fact being used in our modern society? De Botton stops there, but I would like to go a bit further, because this last statement raises the following question: does this divergence in values from person to person constitute an unsolvable problem when we want to generate a unique design? The first part of the question will be explored by looking at the book of Alain de Botton, The Architecture of Happiness (2006). The second part of the question can be answered in several ways. I decided to present one of them, namely how architecture is used as a tool to influence people’s behavior through consumerism, as described by Kevin Ervin Kelley in his essay Architecture for Sale(s): An Unabashed Apologia. A priori, we could think that if the building does not convey the values that the architect intended the visitors to experience, it is in itself a major design failure. And since each of us has a different values and visions of a perfect design, this seems like an impossible challenge. Fortunately the task is not as desperate as it could seem, because what really matters is that only the majority of the people for whom the work of architecture has been designed respond to it as the designer intended. It is thus of primary importance to take into account the Creating emotions… In our question, we imply that a building is capable to generate emotions. This fact has 2 as music, touch, smell, feeling of safety or body perfection) with the new product. cultural environment in which the building will be placed. A futuristic building in a progressive city will not be welcomed the same way in an historic medieval city. And a medieval city in China will not welcome a gothic cathedral the same way as a medieval city in France would. So would an architectural masterpiece be in fact… a mere commercial display? A giant one, with all the lights, bells and whistles, but still a machine with unconfessed lucrative goals… That is what we are going to explore in the next section. In that respect, the design of a building is similar to the design of a commercial: if a new beauty cream is designed for women between 20 and 40 years old, the designer won’t care whether a 70 years old man doesn’t like the commercial. Architects at the heart of a design strategy … and using them. In his book “Commodification and Spectacle in Architecture” (2005), William S. Saunders gathered ten essays on the role of architecture in commoditization. I have chosen to focus on the essay of Kevin Ervin Kelley (2005) because it fits particularly well in our attempt to describe how architecture can be used to influence people. Now imagine that we have defined our target our target audience, that is, the profile(s) of the people that we want our building to have an impact on. How do we know they will like the place? In fact, what makes us like a place? Everyone has experienced that: there are places where we really feel at home. They could even be a library, or a restaurant, but those places are in harmony with us. Alain de Botton (2006) explains that the reason for which we like a place is that it reminds us of our ideal self. Things in our surroundings embody ideals we respect. We arrange our home in such a way that we are reminded of who we want to be, of what makes us feel at peace. Kelley does not see merchandizing as an immoral thing. As long as lies or long-term negative impact on health are not involved, retail can be seen as a positive contribution to people well-being. This can be by the life improvements that the product will bring, or simply by the shopping experience itself. For example, a shopping mall, by its existence, will offer social places, such as cozy cafés, where people could enjoy the atmosphere as part of their shopping tour. Such a shopping mall could be seen as a giant trap where people are subtly manipulated and pushed to consumption, but Kelley thinks otherwise: “we [designers] think that we are helping stores get credit (purchases) for the things they do well.” (2005, p.55). In fact, this is the main reason for which we buy objects, especially decorative ones: it is a bit like buying a virtue or an ideal lifestyle that the object represents. We can expand de Botton’s observations by having a look at marketing strategies: in a commercial spot, the real quality of the product does not takes the front of the scene. Rather, the goal of the 20 seconds is to make us associate things we already like (such What is interesting is the place of the architect in this consumerism trend. Kelley states that the 3 architects are educated to see themselves as artists that can distinguish themselves from the materialistic-oriented parties, traditionally perceived as dishonest. In reality they should instead embrace the opportunity to have a role to play in giving the visitors a positive experience by helping them getting pleasure through their purchases. regain their (lost) power. But to my point of view, he is rather defining a new kind of job, which is not systematically applicable to all architects. We could therefore position the architects over a gradual scale: on one end would stand the traditional architect. His role is to design buildings that facilitate the functioning of the institution that occupies it, and/or is of pure aesthetic purpose. On the other end of the scale would stand a consumerism-oriented designer, who would combine architectural competencies with marketing and economics competencies. He would be the central brain of the marketing strategies. I can only agree with Kelley up to a certain point. While casual consumption of non-needed goods can provide pleasure and is harmless, the border with manipulation is often not clear. Casual purchases can give an ephemeral sense of satisfaction while in the long run leaving the customer in a bitter state of disillusion. Furthermore, it is well-known that lots of goods are designed to maximize the addiction of its consumers. Up to a point where people can’t stop consuming (alcohol, bets, Coca-Cola…) and tumble toward their ruin. As we could see, in consumer-oriented places, architecture is used to generate emotions and is part of an overall marketing strategy. The strength of the architect lies in his creativity. A good idea will make the sale, not the construction plans. Kelley supports this opinion: “Our major emphasis should not be on negotiating and selling construction documents. We ought to sell our ideas and give away construction documents […] Ideas are not related to square footage; they should be sold based on their ultimate value to the client. A big idea merits a big paycheck.” (Kelley, 2005, p. 53). Kelley points out that the current role of an architect is subordinated to an overall strategy whose purpose is to make people consume. He deplores this position, because instead of having marketing and advertisement agencies buying out architecture services, the architect could be adopting a more capitalist-oriented mind: he could widen his role by being at the center of the design and being the one calling for the services of marketing agencies. In fact, Kelley reoriented his own company from a role of architect to a role of designer, as it encompasses not only the architectural design, but also all other aspects (marketing, advertising, branding) that gravitate around the sale of products. As mentioned earlier, these products will be representative of a specific lifestyle and the values it implies. Illustration I would like to illustrate the usage of architecture as an influence medium in a mercantile environment through two examples to show how different designs can trigger opposite emotions, and still be used to attract the customers. Kelley seems to point to a general direction that the architects should follow if they want to 4 Example 1: Frank Gehry’s EMP The Experience Music Project is a museum in Seattle, designed by Frank Gehry and funded by the Microsoft billionaire Paul Allen. Laid down besides the gracious Space Needle in the heart of Seattle, Gehry’s deconstructivist building was considered by many locals as blasphemous (Frank, 2005). Fig. 1. Experience Music Project Museum, Seattle. Outdoors view. Seen from outside, the window-less undulating shape of the building is uncommon and catches the eye. The structure seems to be in movement, floating in the wind. It makes the visitor want to know more… Once inside, we are in for a surprise: apparent structural elements, metallic foils, and various styles are mixed together in some sort of cacophony. A giant cone made of guitars reaches for the ceiling. Our visual senses are aggressed from all directions. Every wall is sculpted in a different way. Visiting this museum is like an exploratory journey, designed to trigger our emotions, to shock us with the unexpected. We browse from one architectural style to the next, without aesthetical coherence, but this is the way that the museum displays the major innovations in architecture, as well as in music. Fig. 2. Experience Music Project Museum, Seattle. Indoors view. The plan of Paul Allen, as explained by Thomas Frank (2005, p. 69), is to make a monument to himself, permanently re-image Seattle as a postindustrial town run by and for persons such as himself, demonstrate high-tech gadgetry (that you might be inclined to purchase or use later on), and become financially self-supporting. Fig. 3. Experience Music Project Museum, Seattle. Guitar tower. So clearly a monument to himself and his products, while keeping the cash balance positive. This illustrates how a shocking architecture can be used for self-promotion. 5 Example 2: Marina Bay Sands When I went to the Marina Bay Sands, I had a strong feeling of peacefulness. The climate was moist and hot, but the presence of a large bay of water gave it a peaceful atmosphere. When I wandered closer to the building, in the late afternoon, the fresher temperature, the open terraces and the fountains made me feel like I was walking through Zen gardens. When entering the building, which is in fact a giant shopping mall overhung by apartments, I had a similar sensation to the one I had when entering a cathedral: the tall ceiling reaching to the sky and the daylight filtering through the windows conveyed a strong impression of majesty. The shopping area in itself was rather similar to nowadays commercial centers: clean, neat and luxurious. In the evening, free light shows were scheduled, and I could enjoy the panoramic view from the lounge bar at the top terrace. Fig. 5. The atmosphere was very relaxing, with the added bonus of the pleasure of discovery and the wow-effect created by the grandiose architecture. It could keep me there for a long time, which is precisely what the retailers expect from their visitors. Fig. 4. view. Marina Bay Sands, Singapore. Indoors view. Conclusions We have learned from Alain de Botton that buildings talk to us. They generate emotions whenever they evoke us some values or a certain lifestyle. This capacity is not a specificity of buildings. It also holds for other types of products, such as consumer goods. As our world is trending towards commoditization, complete marketing strategies are set into place, and architectural design has a major role to play. Kelley encourages us architects to place ourselves at a key point of the design process rather than remaining a “subordinated tool that generates construction plans”. The strategic design ideas should be at the center, rather than the architecture plans. Marina Bay Sands, Singapore. Outdoors 6 We illustrated by two examples how architecture is being used nowadays to generate emotions in the consumer, and make him want to spend his time in a consumerism-oriented building. The generated emotions are rather different, but both approaches reach their goal in their own way. Literature De Botton, A. (2006). The architecture of happiness. London, England: Penguin Books Ltd. Saunders, W. S. (2005). Commodification and spectacle in Architecture. A Harvard Design Magazine Reader, 1. Kelley, K. E. (2005). Architecture for Sale(s): An Unabashed Apologia. A Harvard Design Magazine Reader, 1, 47-59. I found that de Botton and Kelley exposed in a relevant way how architecture can generate emotions and how the latter can be used to influence people as a part of a marketing strategy. However it is important to mention that these are only chosen examples showing the usage of emotion in architecture. Alternative mechanisms to generate emotions through architecture can be found in other studies such as “Emotion in Architecture” by Simon Droog and Paul de Vries (2009). Frank, T. (2005). Rocking for the Clampdown: Creativity, Corporations, and the Crazy Curvilinear Cacophony of the Experience Music Project. A Harvard Design Magazine Reader, 1, 60-77. Droog, S., & De Vries, P. (2009). Emotion in Architecture – The experience of the user. Electronic book retrieved November 19, 2013, from http://issuu.com/pauldevries/docs/20090202_e motioninarchitecture_big Figures Fig. 1 Retrieved November 19, 2013, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:EMPPano11.jpg Fig. 2 Retrieved November 19, 2013, from http://www.flickr.com/photos/yeblind/971767808/ Fig. 3 Retrieved November 19, 2013, from http://megbfrankinteriors.com/frank-gehry-and-theemp-museum Fig. 4 Retrieved November 19, 2013, from http://www.rockpool.com/2013/03/lauren-insingapore-l-part-2/marina-bay-sands-hotelsingapore/ Fig. 5 Retrieved November 19, 2013, from http://denoxa.com/interior/marina-bay-sandssingapore-casino-hotels-reach-newheights/daman.co.id%5Ewpcontent%5Euploads%5E2011%5E03%5EMarina-BaySands-Singapore-interior 7