Ha-Joon Chang - 23 Things They Don't Tell You About Capitalism-Allen Lane (2010)

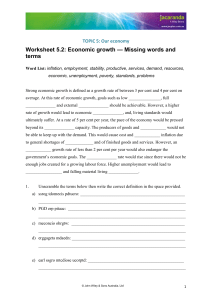

advertisement