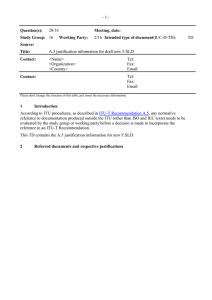

The Indian Journal of Pediatrics https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-019-03130-z ORIGINAL ARTICLE Children ‘At Risk’ of Developing Specific Learning Disability in Primary Schools Sri Lakshmi Chordia 1 & Kanimozhi Thandapani 1 & Arulkumaran Arunagirinathan 1 Received: 22 June 2019 / Accepted: 19 November 2019 # Dr. K C Chaudhuri Foundation 2019 Abstract Objectives To study the proportion of children of age 5 to 7 y at risk of specific learning disability (SLD) and to analyse the sociodemographic risk factors. Methods A school based cross-sectional study was conducted in six schools in Puducherry. Four hundred eighty students were enrolled and study was conducted in a triphasic approach. Phase I- Screening by teachers using SLD-SQ (Specific Leaning Disability – Screening Questionnaire); Phase II- Vision, hearing, and Intelligence Quotient (IQ) assessment were done in students screened positive with SLD-SQ and those with vision or hearing impairment and subnormal intelligence were excluded; Phase IIIRemaining children were subjected to NIMHANS SLD index (Level I profile). Results Of the 480 enrolled students 109 were screened positive with SLD-SQ. Twelve students were excluded in Phase II. Remaining 97 evaluated were evaluated with NIMHANS SLD index and 36 (7.5%) were screened positive. Boys (9.6%) were significantly more affected than girls (4.9%). Similarly, risk was significantly higher in students of government schools (12.1%) than private schools (2.2%). Ignoring punctuation and capitals was the commonest problem in SLD-SQ whereas, dysgraphia was most common in NIMHANS index. Conclusions The present study shows though SLD is highly prevalent and remains undiagnosed due to lack of awareness among teachers and parents. Since early intervention leads to better outcomes, Universal screening should be made mandatory and remedial teaching centres made available, accessible and economical. Keywords Learning disability . Dyslexia . Remedial teaching . Children Introduction Specific learning disability (SLD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that impedes the ability to learn or use specific academic skills (e.g., reading, writing and arithmetic), which is the foundation of other academic learning. The learning difficulties are ‘unexpected’ in that other aspects of development seem to be fine [1]. The prevalence of SLD in India ranges from 1.6%–15% [2–5]. Exact etiology is not known but it is believed to be predisposed by neurological impairment through genetic transmission, developmental anomalies, perinatal insult or malnutrition [6]. * Kanimozhi Thandapani drkani88@gmail.com 1 Department of Pediatrics, Sri Manakula Vinayagar Medical College and Hospital, Puducherry 605107, India If learning disability goes undetected, child’s poor scholastic performance will bring in adverse impact on heath related quality of life by causing poor self-esteem, disturbed peer and family relationships, and unease social interactions [7]. Unfortunately, in India many children remain undiagnosed because of lack of awareness among teachers, parents and health staffs [8]. Also there is no standardized screening protocol favouring early diagnosis or provisions for accessible consistent remedial teaching for intervention. Hence the present study was conducted in primary schools in Puducherry to find out proportion of children of age 5–7 y ‘at risk’ of developing specific learning disabilities and to analyse the socio-demographic risk factors. Material and Methods This school based cross-sectional study was conducted in six schools in Puducherry. Fourteen schools were located within 5 km radius from the authors’ tertiary care centre. By Indian J Pediatr adopting lottery method of simple random sampling, 6 schools were selected. Sample size was calculated as 480 taking prevalence of SLD as 10% [9], confidence interval 95%, absolute precision 3% and 20% non-response rate. After obtaining clearance from Institutional Ethics Committee and permission from Deputy Director of School Education, the study was initiated. All students of age 5 to 7 y from the selected schools whose parents consented were included in the study. The study was conducted with a tri-phasic approach: Phase I – Socio-demographic details of all students were collected. Socio economic status was classified using Modified B.G. Prasad classification (2018) [10]. Specific learning disabilities – screening questionnaire (SLD-SQ) was administered on all the enrolled students with the help of the teachers. SLD-SQ was designed and standardized by Dr. Uday K Sinha at Institution of Human Behaviour and Allied Sciences, copyrighted at 2015 by psychomatrix; permission for its use was obtained from the author. A cut-off score of four or more was considered indicative of possibility of SLD. Sensitivity and specificity of questionnaire is 0.83 and 0.77 respectively for a cut-off of four [11]. Phase II – Children screened positive with SLD-SQ, underwent physical examination (for serious ailments that might intrude with academic performance), vision, hearing and Intelligence Quotient assessment. Vision assessment was done using Snellen’s chart. Visual acuity less than 6/60 was considered abnormal which is cutoff for low vision as per ICD 10 [12]. Hearing assessment was done using Tuning fork 512 Hz by Rinne’s and Webers test. Sensitivity and specificity was 87% and 100% respectively. Hearing was considered impaired if either of the test was abnormal [13]. IQ assessment was done using Seguins Form Board. It is a performance based tool that assesses the visuo-motor skills, eye-hand coordination, visual and spatial perception, cognition speed and accuracy in performing skills. IQ of 90 measured for chronological age was considered cut-off for normal. Correlation with other tests like Malins Intelligence scale for Indian Children and Vineland Social Maturity Scale ranges from 0.31–0.50 [14]. Children who had visual or hearing impairment or subnormal intelligence were excluded from further evaluation. Phase III – NIMHANS SLD index (Level I profile) was administered to children who cleared Phase II assessment of the study. It consists of 8 components: Attention, Visual discrimination, Visual memory, Auditory discrimination, Auditory memory, Speech and Language, Visuomotor skills and Writing skills. Any child less than 8 y who doesn’t perform adequately is considered to have specific learning difficulty or at risk for SLD. Test retest reliability is 0.53 (p < 0.001) [15]. Phase II and III were done by a single investigator to avoid bias. IQ assessment was done by clinical psychologist of authors’ Institute. Data analysis was done using SPSS 24.0 software. Variables such as socio-demographic characteristics, item wise analysis of SLD-SQ, analysis of NIMHANS index were represented in tables showing frequency and percentage. Logistic regression analysis was done to assess the impact of gender, school sector and socio-economic status on risk of SLD. Results The present study was conducted from September 2016 through October 2018. Four hundred ninety two students of age 5–7 y studied in the selected schools. Twelve students were excluded since parents did not give consent. Figure 1 shows the flow of subjects in the study. Majority of them 225(46.9%) were 6 y of age with 53.8% (258) boys and 46.3% (222) girls. Table 1 shows socio-demographic details of students. In Phase I, 109 (22.7%) children had a SLD-SQ score of more than four suggesting possibility of having SLD of which 74 (67.9%) were boys and 35 (32.1%) were girls. This shows higher screened positive male children, compared to female children. In item wise analysis of SLD-SQ, ignoring punctuation and capitals was the commonest problem seen in 174(36.3%) of the students, followed by ineligible writing 133(27.7%). Table 2 shows item wise analysis of SLD-SQ. In Phase II, Out of 109 SLD-SQ screened positive students, 9 had subnormal intelligence, 2 had hearing impairment, 1 had visual impairment and were excluded. Remaining 97 children were assessed with NIMHANS Total number of students of age 5-7 y in selected schools (n=492) 12 excluded since parents did not give consent Total number of students included in the study (n=480) Phase I – Screened with SLD-SQ by teachers 109 screened positive Phase II – Visual impairment (n=1), Hearing impairment (n=2), Subnormal intelligence (n=9) 12 excluded Phase III – NIMHANS SLD index – 36 students identified at risk of SLD Fig. 1 Flow of subjects in the study. SLD Specific learning disability Indian J Pediatr Table 1 Table 3 97) Socio-demographic details of students (n = 480) Characteristics n (%) Age (in years) 5y 6y 7y Sex Boys Girls School sector Government Private Socio-economic status Class I (Upper class) Class II (Upper middle class) Class III (Middle class) Class IV (Lower middle class) Class V (Lower class) S. No Items n (%) 91 (19) 225 (46.9) 164 (34.2) 1. 2. 3. 4. Writing skills Visual discrimination Auditory behavior Auditory memory 35 (36.1) 13 (13.4) 12 (12.4) 10 (10.3) 258 (53.8) 222 (46.3) 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Auditory discrimination Visual discrimination Attention Visuomotor skills Verbal language expression 9 (9.3) 6 (6.2) 5 (5.2) 3 (3.1) 0 255 (53.1) 225 (46.9) n No. of students evaluated with NIMHANS SLD index 8 (1.7) 62 (12.9) 241 (50.2) 141 (29.4) 28 (5.8) n No. of students enrolled in the study SLD index (Phase III) and 36 students (7.5% of study population) were found to be at the risk of SLD. In item wise analysis of NIMHANS SLD index, most of the affected children had difficulty in writing skills [35(36.1%)], followed by impaired visual discrimination [13(13.4%)], poor auditory behavior [12(12.4%)] and inadequate auditory memory [10(10.3%)]. Table 3 shows item wise analysis of NIMHANS index. Analysing the association of socio-demographic factors with risk of developing SLD, it is evident that gender has statistically significant association (p 0.02) with 9.6% of boys being affected compared to 4.6% girls. In socio-economic grounds, 8.3% children from lower socio-economic status (SES) were at risk while only 1.6% from high SES were at Table 2 Item wise analysis of SLD-SQ (n = 480) Item wise analysis of NIMHANS index (Level I profile) (n = risk, yet there was no statistical significance (p 0.48). Comparing school sector to SLD risk status, 12.1% children from government schools were at risk but only 2.2% from private schools were at risk. The association was found to be statistically significant (p 0.000) (Table 4). Discussion The present study was conducted in six schools in puducherry. Three government and three private schools were included to study the differences in prevalence and risk factors. Age group 5 to 7 y was chosen since the age of identification plays a major role in outcome of the child. The screening and assessment tools used were SLD-SQ and NIMHANS SLD index respectively. These tools are recommended by the recent Indian Academy of Pediatrics (IAP) consensus on evaluation and management of learning disability [16]. In the present study, the proportion of children at risk of developing specific learning disability was found to be 7.5%. This S. No Item n (%) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. Ignore capitals or punctuation while writing Writes in ineligible writing Difficulty in differentiating similar sounding words Gets confused in mathematical symbols Forget lessons easily Misplaces words or letters while reading or writing Makes mistakes in solving math problem Makes frequent mistakes in spelling while reading or writing Miss out words or sentences while reading Difficulty in understanding what is taught in class Overall academic ability much below his/her grade level Difficult to make down what is written on the board 174 (36.3) 133 (27.7) 126 (26.9) 126 (26.3) 126 (26.2) 124 (25.8) 123 (25.6) 121 (25.2) 103 (21.5) 89 (18.5) 74 (15.4) 48 (10) n Number of students enrolled in the study Indian J Pediatr Table 4 Association between socio-demographic variables and SLD risk status Variables Gender Boys (n = 258) Girls (n = 222) Socio-economic status High (Class I, II, III) (n = 60) Low (Class IV, V) (n = 420) School sector Private (n = 225) Government (n = 255) Odds ratio 95% Confidence Interval P value 233 (90.3%) 211 (95.1%) 0.407 0.190–0.871 0.02 1 (1.6%) 59 (98.3%) 1.33 0.593–3.006 0.485 35 (8.3%) 385 (91.6%) 5 (2.2%) 31 (12.1%) 220 (97.8%) 224 (87.8%) 0.179 0.071–0.450 0.000 At risk of SLD No risk of SLD (n = 36) (n = 444) 25 (9.6%) 11 (4.9%) p < 0.05 is considered statistically significant finding is closely in consistence with a study conducted at Andhra Pradhesh in 2017 by Bandla et al. (6.6%) [17]. However, it is relatively low when compared to studies conducted by Mogasale VV (15.17%) at Karnataka in the year 2014 and Sridevi et al. (19%) in Hyderabad (2015) [5, 18]. Analyzing various other studies, range of SLD prevalence can be given as 6.6% to 19% in South India [5, 17–20] and 1.58% to 12.8% in north India [2–4, 21–23]. These studies had heterogeneity in sample size, sampling technique, screening tool used, method used for assessing SLD, study setting, study population and environmental background which explains variation in the prevalence figures. The present study showed statistically significant gender difference with boys (9.6%) being affected twice more than girls (4.9%). According to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), learning disability is two to three times more prevalent in boys than in girls [1]. In an article published in JAMA that includes four large epidemiological studies on sex differences in SLD with almost 10,000 participants, it is clearly evident that SLD is substantially more common in boys [24]. A genetic research on X-chromosome has unravelled nine new genes, which because of their location on X-chromosome, are known to affect predominantly males [25]. Also physiological differences between males and females like developmental lag in childhood, biochemical (boys are resilient to proteins), and neonatal differences (hormonal milieu – more exposure to androgen in boys) could play a role [26]. Similarly, students from government schools (12%) were more at risk compared to private school students (2.2%) and there was statistical significance. Lack of adequate training, perhaps due to late admission age, poor parental supervision and involvement could be contributing factors. Regarding socio-economic status, 8.3% children from lower socio-economic status were at risk while only 1.6% from high SES were at risk, yet there was no statistical significance. Similar finding was noted by Padhy et al. [2]. Karande and Bandla et al. stated a high prevalence rate of SLD among high and upper middle socio-economic class [7, 17]. The study settings in these studies were from private remediable clinics whose parents are expected to be economically affordable. With item wise analysis of SLD-SQ, ignoring punctuation and capitals was the commonest problem, followed by ineligible writing. Padhy et al. also used SLD-SQ to screen for SLD [2]. They found missing out words or sentences while reading to be the commonest issue followed by, misplacing letters or words while reading or writing. With item wise analysis of NIMHANS index, 36.1% had difficulty in writing (dysgraphia), followed by impaired visual discrimination in 13.4% and poor auditory behavior in 12.4%. Since age group included in present study is 5 to 7 y, Level I profile is used and if any child does not perform adequately, he/she is considered to have specific learning ‘difficulty’, not disability. Neuronal circuitry is constantly reconstructed in response to experience. Hence effective early intervention can potentially bring in compensatory mechanisms to bridge functional gaps [27]. During the course of study, authors observed that the awareness of teachers on SLD was limited. Kamala et al. conducted a study among teachers in Puducherry and found that their understanding on SLD is sparse [28]. Padhy et al. also reported the same [29]. Strengths of present study are use of standardised screening and assessment tools. Not many studies have been conducted in 5–7 y age children to identify those ‘at risk’ and this is first such study in the region. The use of NIMHANS index in English could have led to overestimation of prevalence in government schools. Also clustering of schools in one region is a limiting factor in generalising the results to whole of Puducherry. The association of other psycho-behavioral conditions were not looked for in the participants. Those identified ‘at risk’ need reassessment at 8 y since few maybe ‘normal late developers’. Indian J Pediatr Conclusions 10. The authors found a proportion of 7.5% children, belonging to age group of 5 to 7 y to be ‘at risk’ of developing SLD with significant male predominance. Teachers and pediatricians should be made aware of early signs of SLD. Screening tools need to be standardised and made available in all vernacular languages. Also universal screening for LD should be made mandatory and remedial centres made accessible and economical. This promotes early identification and intervention, which is crucial to optimise learning and prevent secondary emotional problems. More longitudinal studies on large scale focussing on intervention strategies would help in standardizing the management protocols for such children. 11. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the School teachers who helped them in screening children with SLD-SQ score and Dr. Sindhuri, Assistant Professor, Community Medicine, Sri Manakula Vinayagar Medical College and Hospital for statistical analysis. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. Authors’ Contribution SLC collected the data, reviewed the literature and drafted the manuscript. KT and AA conceptualized the study, reviewed the literature and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to writing the paper and approved the final version of the manuscript. AA is the guarantor for this paper. 19. Compliance with Ethical Standards 20. Conflict of Interest None. 21. 18. 22. References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®), 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Pub; 2013. Padhy SK, Goel S, Das SS, Sarkar S, Sharma V, Panigrahi M. Prevalence and patterns of learning disabilities in school children. Indian J Pediatr. 2016;83:300–6. Arun P, Chavan BS, Bhargava R, Sharma A, Kaur J. Prevalence of specific developmental disorder of scholastic skill in school students in Chandigarh, India. Indian J Med Res. 2013;138:89. Dhanda A, Jagawat T. Prevalence and patterns of learning disabilities in school children. Delhi Psychiatry J. 2013;16:386–90. Mogasale VV, Patil VD, Patil NM, Mogasale V. Prevalence of specific learning disabilities among primary school children in a south Indian city. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79:342–7. Altarac M, Saroha E. Lifetime prevalence of learning disability among US children. Pediatrics. 2007;119:S77–83. Karande S, Bhosrekar K, Kulkarni M, Thakker A. Health-related quality of life of children with newly diagnosed specific learning disability. J Trop Paediatr. 2009;55:160–9. Karande S. Current challenges in managing specific learning disability in Indian children. J Postgrad Med. 2008;54:75. Mugali J, Patil S, Gosavi K, Pattanshetti N, Kovvuri S, Deepthi PT. Study of specific learning disorder in children with poor academic performers. Int J Indian Psychol. 2017;4:153–7. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. Pandey VK, Aggarwal P, Kakkar R. Modified BG Prasad’s socioeconomic classification-2018: the need of an update in the present scenario. Indian J Comm Health. 2018;30:82–4. Sinha UK. Specific Learning Disability- Screening Questionnaire (SLD-SQ). New Delhi: Psychomatrix Corporation; 2012. p. 1–5. World Health Organisation (2004). ICD-10: international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems: tenth revision, 2nded. World Health Organisation. Available at: https://apps. who.int/iris/handle/10665/42980. Kelly EA, Li B, Adams ME. Diagnostic accuracy of tuning fork tests for hearing loss: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599818770405. Koshy B, Thomas T, Mary H, et al. Seguin form board as an intelligence tool for young children in an Indian urban slum. Fam Med Commun Health. 2017;5:275–81. Panicker AS, Bhattacharya S, Hirisave U, Nalini NR. Reliability and validity of the NIMHANS index of specific learning disabilities. Indian J Mental Health. 2015;2:175–81. Nair MKC, Prasad C, Unni J, Bhattacharya A, Kamath SS, Dalwai S. Consensus statement of the Indian academy of pediatrics on evaluation and management of learning disability. Indian Pediatr. 2017;54:574–80. Bandla S, Mandadi GD, Bhogaraju A. Specific learning disabilities and psychiatric comorbidities in school children in South India. Indian J Psychol Med. 2017;39:76–82. Sridevi G, George AG, Sriveni D, Rangaswami K. Learning disability and behavior problems among school going children. J Disabil Stud. 2015;1:4–9. Petchimuthu P, Sharma N, Gaur A, Kumar R. Pattern of specific learning disability and awareness among care providers in children between 8-12 years. Int J Contemp Pediatr. 2018;5:809–14. Kumari MV, Barkiya SM. Children with poor school performance for specific learning disability. Int J Sci Stud. 2016;3:201–5. Kumar J, Suman S. Identification and prevalence of learning disabled students. Int J Sci Res Publ. 2017;7:317–9. Singh RP, Nijhawan A, Nijhawan M, et al. Prevalence of dyslexia among school children in western Rajasthan, Jaipur. IOSR J Dental Med Sci. 2017;16:59–62. Choudhary MG, Jain A, Chahar CK, Singhal AK. A case control study on specific learning disorders in school going children in Bikaner city. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79:1477–81. Rutter M, Caspi A, Fergusson D, et al. Sex differences in developmental reading disability: new findings from 4 epidemiological studies. JAMA. 2004;291:2007–12. Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. "Learning Disabilities In Males: Nine New X Chromosome Genes Linked To Learning Disabilities." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 20 April 2009. Available at: www. sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/04/090419133841.htm Morgan SR. The learning disabilities population: why more boys than girls? A hot area for research. J Clin Child Psychol. 1979;8: 211–3. Shaywitz SE, Morris R, Shaywitz BA. The education of dyslexic children from childhood to young adulthood. Ann Rev Psychol. 2008;59:451–75. Kamala R, Ramganesh E. Knowledge of specific learning disabilities among teacher educators in Puducherry, union territory in India. Int Rev Soc Sci Humanities. 2013;6:168–75. Padhy SK, Goel S, Das SS, Sarkar S, Sharma V, Panigrahi M. Perception of teachers about learning disorder in a northern city of India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2015;4:432–4. Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.