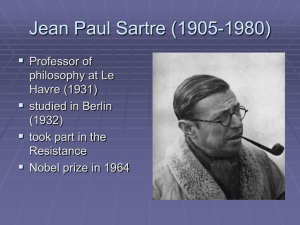

ANGELO ESPINAS EXISTENTIALISM FOR DISCUSION PURPOSE ONLY SARTRE’S PHILOSOPHY Introduction • Sartre felt most at home in cafés and restaurants where he could annex space by dominating the conversation and exhaling smoke…. But, like Kafka, he never felt more free than when he was writing, creating an imaginary space. Paper as magic carpet; pen as wand…. After a paradisal infancy centered on the belief that he was beautiful, he systematically tried to reject his body. To reassure his mind that it had nothing to fear from sibling rivalry with his mal-treated body he consistently ignored all messages [his body] sent out. He resisted fatigue, treated pain as if it were a challenge. To step up his productivity he made reckless use of… stimulants, taking sedatives when he wanted to relax. He resented the time he had to spend on washing, shaving, cleaning his teeth, taking a bath, excreting, and he would economize by carrying on conversations… through the bathroom door. He had no personal vanity…. When his smoke-stained teeth began to decay, he refused to waste time on seeing a dentist…. He took immeasurable pride in his intellect — “I’ve got a golden brain.” (Ronald Hayman, Sartre: A Biography (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987), pp. 21-22. • According to his various biographers, even Simone de Beauvoir, Sartre was a man obsessed with his own intellect, to the neglect of almost all else. He was always certain of his own value to society as a philosopher and writer, always taking the opportunity to demonstrate his superior mind. • Sartre untiring in his pursuit of philosophical reflection, literary creativity. But in the second half of his life, he became active in his political commitment which gained him worldwide acclaim. He is regarded as the father of Existentialist philosophy, and his writings set the tone for intellectual life in the years that followed the Second World War Early Life • • Jean-Paul Sartre was born 21 June 1905 in Paris, the only child of Jean-Baptiste and Anne-Marie Sartre, his parents came from distinguished families. JeanBaptiste Sartre was the son of Dr. Eymard Sartre, a noted country doctor in the Dordogne region of France. Sartre’s mother was the first cousin of Albert Schweitzer, the famous German missionary. Eymard Sartre was a cynical and unhappy man. He had married the daughter of a pharmacist, under the impression her family was well-positioned. Much like his grandson Jean-Paul, it is clear that Eymard cared a great deal about his social status. Eymard had written several medical texts; he published his first work in his early twenties. Anne-Marie Schweitzer was the daughter of Karl “Charles” Schweitzer. While the uncle of famed thinker Albert Schweitzer, Karl was famous ANGELO ESPINAS EXISTENTIALISM FOR DISCUSION PURPOSE ONLY in his own right. Karl had published several texts on religion, philosophy and languages. In fact, Karl was the co-author of a series of texts on English, German, and French. With two authors for grandfathers, Jean-Paul Sartre might have been destined to write • Jean-Baptiste Sartre and Anne-Marie Schweitzer married on 5 May 1904, in Paris. The two were truly in love, Anne-Marie completely dedicated to her husband. Both families seem to have been pleased by the marriage. When Jean-Paul was born his father Jean-Baptiste, was away on a naval assignment. Upon his return he was happy to see his son was. Sadly however, Jean-Baptiste had contracted entercolitis (infection of large intestines) during a voyage to China; he became ill in 1906, and was forced to leave the navy. The young family moved to a farm near Eymard Sartre's residence. And one year after Jean-Paul birth his father in 1906, at the age of 32. Jean-Paul would later write: "The death of Jean-Baptiste was my greatest piece of good fortune. I didn't even have to forget him," • After the death of Jean-Paul's father, his mother moved into her parent's home. His grandfather was a strict man, dedicated to learning, while his mother pampered young Jean-Paul. The year's living in the Schweitzer house affected Sartre for his entire life. Anne-Marie and Jean-Paul shared a room in the Schweitzer residence. Anne-Marie found herself treated like a child by her domineering father and escape his oppressive personality, she showered her young son with attention, often treating him like a toy or a doll. • Karl Schweitzer presided over others with his size and personality. His commanding voice intimidated others. Karl knew he was still attractive, and sought to prove his virility at every chance. As Jean-Paul grew, he saw this "religious" man conduct numerous affairs, including one with a former student. Anne-Marie came to despise her father's behavior, as did her son. Curiously, Sartre would engage in numerous affairs and empty relationships throughout his life. • Physically, Jean-Paul was not attractive. From an early illness, Sartre lost most of his vision in one eye. This eye seemed to look askance, as if Sartre was not paying attention. Worse, it was clear the boy was destined to be short and awkward. Without his curly long hair and fancy clothes, Sartre's ugliness was obvious -- even to his mother. • Some children did not hide their disdain for young Jean-Paul's appearance. His lack of physical size and his odd appearance made him a target for abuse. He began to show signs of a vindictive and angry personality. Jean-Paul's only comfort was his self-confidence; he knew he was smarter than other children. ANGELO ESPINAS EXISTENTIALISM FOR DISCUSION PURPOSE ONLY • Karl also knew his grandson was smart. From seven generations of teachers, Karl was eager to tutor young Jean-Paul. In fact, Karl was quite proud of his "little man" as a student. Curiously, Sartre would deny in several essays and his autobiographies that he had been tutored by his grandfather. Karl, despite JeanPaul's statements to the contrary, was an excellent tutor and was dedicated to his grandson's success. • When he was eight, Sartre received some puppets from his mother which inspired him to write scripts and stage shows. He slowly gained a small group of friends, or at least children willing to tolerate him in return for entertainment. Sartre enjoyed the attention associated with his shows; he had learned that people like a performer. • When Germany declared war in 1914, Sartre was caught up in the frenzy of nationalism he even wrote a short story about a young French private who captures the Kaiser. To prove he is superior to the German, the young Frenchman challenges the Kaiser to a fist fight and wins. Jean-Paul was writing constantly; he felt a sense of power and control while writing. • In 1915, Jean-Paul enrolled at Lycée Henri IV, a well-regarded school. At the school, he easily made friends and demonstrated an abundance of wit. One teacher noted that Sartre possessed an excellent mind, but lacked mental discipline; Jean-Paul did not refine his thoughts. This is a personality trait that Sartre never outgrew, his mind would race from topic to topic, never focused long enough to refine a thought, this tendency also resulted in careless errors. The Stepchild & Rebel • When Sartre was twelve years old, his mother decided to get married again. Sartre viewed this decision as a betrayal on the part of his mother. Sartre had grown unusually close to his mother and demanded all her attentions. His mother has been a consolation of sort from the tension between him and the dominant patriarchs in his family which lasted for his entire life. Sartre rebelled against his grandfather and he quickly rebelled against Mancy - his stepfather. He was constantly in trouble, fought with fellow students often enough that he regularly served after-school detention. • His parents began to worry that Sartre would become a thug -- a common thief or even worse. Sartre stole money from his mother's room and then lied about doing so. His behavior was too much for his stepfather to accept so in 1920, Mancy realizing that he could not control young Jean-Paul, decided to send Sartre to Paris to study at the Lycée Henri IV; Sartre would be a boarder at the school. ANGELO ESPINAS EXISTENTIALISM FOR DISCUSION PURPOSE ONLY Ecole Normale Supérieure • In August of 1924, Sartre placed seventh on the Ecole Normale Superieure (ENS) entrance exams, which are to this day highly competitive. During Sartre's first year at ENS, he was one of only five students of philosophy. The "Normaliens," as ENS students were known, tended to study theology, psychology, and the classics. Philosophy, at least during the 1920s, had fallen from favor, being viewed as a topic without application. Sartre enjoyed the study of psychology and studied and critiqued Freud throughout his writings. • He read a lot of classic literature, and while he claimed that he did not read the "classics" while at ENS, library records indicate Sartre checked out hundreds of books, many of them classics. Reading hundreds of works gave Sartre a vast amount of information from which to construct his papers as a student. • Unfortunately, Sartre was still as disorganized intellectually, some of his teachers observed that Sartre would base papers upon theories he only partially understood and he was quick to draw conclusions. However, his gift with words sometimes masked Sartre's ignorance or even intentional errors. His eloquence served Sartre as a substitute for any depth of knowledge. • Simone de Beauvoir • In 1928, Jean-Paul placed last -- fiftieth -- in his class at the Sorbonne on his agrégation, a form of exit exam. The topic of Sartre's paper had been Nietzsche's writings and "contingency." That was difficult for Sartre to accept, who considered himself quite smart. However, this failure would serve to be the most important event in his life. He was forced to wait for another examination, and while waiting for his next examination he met Simone de Beauvoir. • Sartre and de Beauvoir were intellectual match. De Beauvoir offered Sartre emotional and professional companionship throughout his life. For the next agrégation the two studied together. Sartre placed first on the exam this time, and de Beauvoir placed second. Somehow throughout their life together, this is how they are remembered: together one right after the other. • • The love affair of Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre is the most unconventional of relationships. They were never exclusive, both having other lovers at different times in their lives. The pair never lived together and marriage was definitely out of the question for both -- it represented society's view of relationships. According to many sources, they addressed each other formerly, as colleagues more than romantic lovers. • They helped influence the way the world views the concept of the Self and its relation to personal freedom. Together they challenged the way we view ANGELO ESPINAS EXISTENTIALISM FOR DISCUSION PURPOSE ONLY commitments and relationships. Simone de Beauvoir, like Sartre, was responsible for shaping the post-war minds of France and the world. Her book The Second Sex has frequently been considered the spark that fueled the modern feminist movement of the 1960’s. Sartre and de Beauvoir kept their pact of transparency, being totally open and honest about their lives. These two great minds had the personal resolve and dedication to this philosophy, and also that they chose to pursue it hand and hand. First Encounter with Phenomenology • One night while in Paris, Sartre and de Beauvoir were drinking with a school friend, Raymond Aron, and in the course of their conversation Aron mentioned about phenomenology. He used a beer mug to illustrate phenomenology, discussing the mug's properties and essence. Sartre was intrigued, so he began to read about this school of philosophy. In 1933 Jean-Paul went to Berlin to study the lectures of Edmund Husserl. After a year, Sartre returned to teaching with new enthusiasm. When Sartre published the novel Nausea in 1938, he included a phenomenological analysis of a glass of beer in the novel, as a tribute to Raymond Aron. • When World War II broke, Sartre was enlisted in the military once again. Sartre served in the meteorological service, launching weather balloons. Unfortunately, Sartre was captured on 21 June 1940. While in the stalag, Sartre spend much of his time writing what was to become Being and Nothingness. According to one biographer, Sartre neglected himself while imprisoned, washing rarely, failing to shave, and developing a reputation for being rather foul. Sartre escaped in March 1941 and managed to return to Paris and somehow returned to his teaching post. Existentialism and Politics • • In June 1943, Sartre's anti-Nazi play The Flies opened at a Paris theatre, after 40 performances it closed but left quite an impression among the artistic community of Paris. After the war Sartre found himself famous --and "existentialism" was the philosophy to study. Sartre spread his idea through his editorship of the magazine, Les Temps Modernes, a publication was named for the Charlie Chaplin film Modern Times. • As existentialism grew in popularity Sartre slowly left the philosophy that had brought him fame. Sartre claimed a "conversion" to Marxism. Such move to the political left was partly influenced by Maurice Merleau-Ponty. As the Cold War developed, Sartre came to support the Soviet Union. However, his support of Soviet Communism cost him of his friendship with Albert Camus. ANGELO ESPINAS EXISTENTIALISM FOR DISCUSION PURPOSE ONLY • • In 1960 Sartre published his work in defense of Marxism, The Critique of Dialectical Reason. It was meant to be two volumes, but the second was abandoned by Sartre before completion. The unfinished work was published after Sartre's death. In The Critique, Sartre tried to defend "pure" Marxism as respecting individual freedoms, unfortunately however for Sartre, most people saw Marxism as it existed in the Soviet Union, as a system curtailing human freedom. • In 1964, Sartre was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature. He refused to accept the award on "political" grounds. In 1968, Paris university students rebelled and called for various reforms. Sartre's support of the students caused him problems with both the left and the right in France. The right leaning supporters of President de Gaulle thought Sartre contributed to the protests. The French Communist Party did not support the students, thinking their demands for liberalized education unreasonable. Both the left and right in France considered the universities fine as they were. Last Years • From 1968 until his death, Sartre embodied the left, socially and politically. He stopped wearing suits and ties, protested the Vietnam War, and found a new following in student "radicals" in both Europe and America. By the late 1970s, Jean-Paul Sartre's body began to rebel. He smoked two packs of cigarettes a day, drank heavily, and used amphetamines while writing. For all this talk about logic and individual will, Sartre could not stop his bad habits. • On April 15, 1980, Sartre died. Simone de Beauvoir attempted to spend the night next to his body, but hospital employees removed her from his bed. She had loved him since they met to study for the agrégation. Sartre's popularity might have diminished by the end of his life, but his death brought forth the kind of emotional displays normally reserved for great political leaders. More than 50,000 people lined the streets of Paris for Sartre's funeral procession on 19 April 1980. Sartre's ashes were buried at the Montparnasse Cemetery. Later, Simone de Beauvoir's ashes were buried next to his. Works • Emotions: Outline of a Theory, Essay: 1936 (L'Imagination) • Transcendence of the Ego, Text: 1937 (La Trascendance de l'Ego) • Nausea, Novel: 1938 (La Nausée) • Being and Nothingness, Essay: 1943 (L'Etre el le Néant) • The Flies, Play: 1943 (Les Mouches) • No Exit, Play: 1944 (Huis Clos) • The Age of Reason, Novel: 1945 (L'Age de raison) • Existentialism and Human Emotions, Text: 1946 (L'Existentialisme est un ANGELO ESPINAS EXISTENTIALISM FOR DISCUSION PURPOSE ONLY humanisme) • Anti-Semite and Jew, Essay: 1946 (Réflexions sur la question juive, written 1943) • The Respectful Prostitute, Play: 1947 • Dirty Hands, Text: 1948 (Les Mains sales) • Saint Genêt, Biography: 1952 • The Critique of Dialectical Reason, Text: 1960 • The Family Idiot, Critique: 1982 Philosophical Influences • Sartre spent most of his life in Paris. After a traditional philosophical education in prestigious Parisian schools that introduced him to the history of Western philosophy with a bias toward Cartesianism and neo-Kantianism, he went to the French Institute in Berlin where he read the leading phenomenologists of the day, Husserl, Heidegger and Scheler. He appreciated Husserl's restatement of the principle of intentionality (all consciousness aims at or “intends” another-thenconsciousness) that seemed to free the thinker from the inside/outside epistemology inherited from Descartes while retaining the immediacy and certainty that Cartesians hold so highly. • In his masterwork, Being and Nothingness Sartre tackles Heidegger’s version of Husserlian intentionality by insisting that human reality (Heidegger's Dasein) is “in the world” primarily via its practical concerns and not its epistemic relationships as Husserl intended. This lends both Heidegger's and Sartre's early philosophies a kind of “pragmatist” character that Sartre, at least, will never abandon. • Sartre may have read the phenomenological ethicist Max Scheler, whose concept of the intuitive grasp of model individuals is illustrated in Sartre's reference to the “image” of the kind of person one should be that both guides and is fashioned by moral choices. But Scheler following the Husserlian idea argues for the “discovery” of such value images, Sartre on the other hand insists on their creation. Here Sartre’s “existentialist” version of phenomenology is already in evident. • Sartre was also influenced by Marxist ideas. Although he was not a serious reader of Hegel or Marx until during and after the war he came under the influence of Alexandre Kojève's Marxist and proto-existentialist interpretation of Hegel. Kojeve was a Russian born French Marxist philosopher who introduced Hegel into the 20th century French philosophy. But it was Jean Hyppolite's translation of and commentary on Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit that marked Sartre's closer study of the seminal German philosopher. • In his last years, Sartre became almost totally blind. Yet he continued to work with the help of a tape recorder, producing with Benny Lévy portions of a “co-authored” ethics, the published parts of which indicate that its value is more biographical than philosophical. After his death, thousands spontaneously joined his funeral ANGELO ESPINAS EXISTENTIALISM FOR DISCUSION PURPOSE ONLY cortège in a memorable tribute to his respect and esteem among the public at large. The headline of one Parisian newspaper lamented: “France has lost its conscience.” Phenomenology and Ontology • • Sartre’s task was to develop a phenomenological ontology, that is, to study the way the world is revealed through the structures of consciousness. Through the study of the structures of consciousness, Sartre believes that this will provide us with an ontology, or an account of what the world must be like for experience to be the way it is. Sartre’s philosophy owes much to Heidegger, but there are certain differences between the two. For Sartre, the standpoint of the human subject is the beginning and the end of his philosophy which means that he studied the human individual condition for the sake of the meaning of existence of the human individual. For Heidegger on the other hand, while the starting point is the Dasein, his philosophy must end up with ‘being.’ For Sartre, human consciousness confronts a totality of being that is alien and meaningless as Sartre emphasized human willing and action. This thinking goes with it a kind of subjectivism that Heidegger tried to avoid. For Sartre we must make our way in the world by subjectively creating meaning rather than having it by “letting be” as Heidegger proposed. • Like Husserl and Heidegger, Sartre distinguished ontology from metaphysics and favored the former. For Sartre, ontology is primarily descriptive and classificatory; ontology is a description of human existence. Metaphysics on the other hand purports to be causally explanatory, offering accounts about the ultimate origins and ends of individuals and of the universe as a whole. • His Being and Nothingness is subtitled a “Phenomenological Ontology.” Its descriptive method moves from the most abstract to the highly concrete. It analyzes two distinct and irreducible categories or kinds of being: the in-itself (ensoi) and the for-itself (pour-soi), roughly the nonconscious and consciousness respectively, adding a third, the for-others (pour-autrui). • Being-in-Itself. Sartre applied the French "en-soi," which loosely means "in-self," to describe the state of being of objects -- things without self-awareness. Sartre's "Being-in-Itself" represents the idea that only concrete phenomena have any ontological status; only the concrete is real. Husserl's approach to phenomenology was embraced by Sartre as a basis for existential exploration. To simplify this concept, Sartre might state that a rock is a rock -- it cannot change what it is. In this manner, Sartre suggests there is facticity, or truth, in the existence of some objects. ANGELO ESPINAS EXISTENTIALISM FOR DISCUSION PURPOSE ONLY • Being-for-Itself. In contrast to "Being-in-Itself" is Sartre's "Being-for-Itself" -- a state of self-awareness and control. Walter Kaufmann explains the differences thusly: The pour-soi (for-itself) is that being which is aware of itself: man. • Sartre's "Being-for-Itself" describes human consciousness as possessing the characteristics of incompleteness and potency, with an indeterminate structure. The absence of a Creator leaves man without a predefined nature. Without a nature, individuals are nothingness. In effect, the essence of man is a complete lack of everything. Nothingness, Sartre thought, was freedom and free will. Applying this definition of nothingness to individuals, mankind is freedom. Sartre contended that not only was the individual free, but the essence of mankind was freedom. As a result of this freedom, individuals are responsible for all their actions and thoughts. • • I am responsible for everything... except for my very responsibility, for I am not the foundation of my being. Therefore everything takes place as if I were compelled to be responsible. I am abandoned in the world... in the sense that I find myself suddenly alone and without help, engaged in a world for which I bear the whole responsibility without being able, whatever I do, to tear myself away from this responsibility for an instant. o Being and Nothingness, "Being and Doing: Freedom” • Only the in-itself is conceivable as substance or “thing.” The for-itself is a no- thing, the internal negation of things. The principle of identity holds only for being-initself. • Being-in-itself and being-for-itself have mutually exclusive characteristics The initself is solid, self-identical, passive and inert. It simply “is.” The for-itself is fluid, nonself-identical, and dynamic. It is the internal negation or “nihilation” of the initself, on which it depends. Viewed more concretely, this duality is cast as “facticity” and “transcendence.” Human beings are entities that combine both, which is the ontological root of our ambiguity. • • The “givens” of our situation such as our language, our environment, our previous choices and our very selves in their function as in-itself constitute our facticity. But as conscious individuals, we transcend (surpass) this facticity in what constitutes our “situation.” In other words, we are beings “in situation,” but the precise mixture of transcendence and facticity that forms any situation remains indeterminable, at least while we are engaged in it. Hence Sartre concludes that we are always “more” than our situation and that this is the ontological foundation of our freedom. We are “condemned” to be free. ANGELO ESPINAS EXISTENTIALISM • FOR DISCUSION PURPOSE ONLY • The category or ontological principle of the “for-others” comes into play as soon as the other subject or Other appears to us. The Other cannot be deduced from the two previous principles but must be encountered. This is illustrated by Sartre's analysis of the shame one experiences at being discovered in an embarrassing situation. Such situation carries the immediacy and the certainty of our perception of other “minds.” Existence Before Essence • Sartre is responsible for the dictum that existentialism is best known for: existence precedes essence, (but these has a different definition from the Aristotelian concepts). For existentialism only man "exists," (Heidegger insisted that only man "exists" in the sense that only man can stand out of his existence and evaluate his own existence). Hence, man's existence is different from other objects in the world. The essence of a thing is the set of its defining properties. For Sartre an entity’s essence precedes its existence only if it is a manufacture object or article; with respect to such article or object, we can inquire what is it or what is it for. The initial ideas, for example, of the statue in the sculpture’s mind or the blueprint of an architect, are examples of how the essences of created things precede their actual existence. • But for human beings, there is no such blueprint of how we would be or how or what we are. Sartre was clear in his description, he wrote: o "It means that first of all, man exists, turns up, appears on the scene and only afterwards defines himself." (The Humanism of Existentialism from Essays on Existentialism) o • Thus man exists first and gradually creates and defines his own essence. • Therefore, Sartre stressed: "Man is nothing else but what he makes of himself. Such is the first principle of existentialism...man first exists, that is that man first of all is the being who hurls himself toward a future and who is conscious of imagining himself as being in the future." (THE from EE.) • Rather than being an essence, man is the structureless phenomenon of consciousness in the world. Man as consciousness, as a for-itself, is purely transparent, volatile self-projection continually negating the staticity, structure and heaviness of the in-itself. "Man at the start is a plan which is aware of itself...nothing exists prior to this plan." (THE from EE. p.36.) • Hence for Sartre, nothing at the core of a person defines what he is. We cannot describe someone as naturally selfish, aggressive, good, social, rational, nor assigns a universal essence to him. One is social, only when he chooses to engage ANGELO ESPINAS EXISTENTIALISM FOR DISCUSION PURPOSE ONLY in social activities, but this does not define what or who he is. But while there is no universal human nature there is a universal human condition. • We all face the same challenges, same questions, same limitations, but within these existential structures we respond in our own unique way. • Situation • Existentialism stressed the situated character of man's existence. For Sartre situation is "my position in the midst of the world defined by the relation between the instrumental utility or adversity in the realities which surround me and my facticity." (Being and Nothingness) • Situation cannot be considered as set of constraints to which man is subject. Situation stems from the illumination of constraints by freedom which gives to it its meaning as constraints. (BAN, Being and Doing) Sartre further stressed: • But precisely because I project myself toward an end across a world of relations, I now meet with consequences, with linked series, with complexes, and I must determine to act according to laws. These laws and the way I make use of them decide the failure or success of my attempts. But it is through freedom that lawful relations come into the world. Thus freedom enchains itself in the world as a free project toward ends. (BAN p. 551/ BAD p. 276.) • Sartre emphasized that it is useless to talk about action without cause, or end or motive, for there cannot be any action without cause or motive, and such does not concern the question of freedom. And although there is no act which does not have any motive or cause, "it is the act which decides its ends and motives and the act is the expression of freedom." (BAN. p. 414.) • Thus, Sartre although maintaining that there is always a situation from which man chooses, its influence upon man's freedom is inconsequential, the past has no effect on man's choices, man does not choose in the light of past choices. Human Freedom • When existentialists talk about freedom they refer to personal freedom, that is the power of the person over his actions, his person and self. The person has the capacity to determine his action and his self. Man as a subject determines himself, it is he who creates his personality, he is the product of his own decision; he cannot be the product of any form of determination, whether social, economic or biological. • Sartre asserts that it is through freedom that man defines his essence. Freedom makes possible the essence of man, and man cannot escape this freedom. Human freedom precedes essence in man and makes it possible; the essence of the human being is suspended in his freedom. What we call freedom is impossible to ANGELO ESPINAS EXISTENTIALISM FOR DISCUSION PURPOSE ONLY distinguish from the being of "human reality." (BAN) Man's essence is freedom and we cannot distinguish his being and freedom. His being is his freedom; he does not exist and later on becomes free. Sartre wrote: "Man does not exist first in order to be free subsequently; there is no difference between the being of man and his being free." (BAN) • How does Sartre explain the relation of the past to man's future or present project? Sartre said that the meaning of the past is strictly dependent on my present project. This means that the fundamental project which I am, decides absolutely the meaning which the past can have for me and for others. I alone can decide at each moment the significance of the past, by projecting myself toward my ends I preserve the past with me and by action I decide its action. (BAN. p. 498.) Responsibility • • With such great emphasis on the freedom of man, Sartre declared that man is condemned to be free and he carries the whole world on his shoulders, he is responsible for the world and for himself as a way of being. (BAN p. 553/ BAD p.277) Being the uncontestable author of an event and of himself; he is accountable for it. Man must assume the situation with the proud consciousness of being the author of it, for it acquires meaning only in and through his project. It is senseless therefore to complain since nothing alien has decided what we fell, what we live and what we are. "In this sense the responsibility of the for-itself is overwhelming since he is the one by whom it happens that there is a world." (BAN.) Responsibility then is a logical consequence of freedom. Bad Faith and Authenticity • Sartre warns us against the trap of labeling ourselves for this only denies our freedom. One may say, I am conservative or this and that. People can put labels on others by referring to them as this kind of person or that kind of leader. Labels become our identity only because we make them so. • The attempt to deny our freedom is called by Sartre as bad faith. In bad faith, we see ourselves as products of our circumstances, or the attempt to identity ourselves with our past choices while closing off our future possibilities. In bad faith, we become an ‘in-itself’ a being that is defined or has a fixed identity. As free individuals, we must exercise our freedom and create or invent our own essences. ANGELO ESPINAS EXISTENTIALISM • FOR DISCUSION PURPOSE ONLY For Sartre, only when we take our responsibility for the meaning of our past and present and self-consciously choose our future, will we achieve authenticity. Authenticity is the true value in an otherwise valueless universe. The Gaze and Others as Hell • Man is not alone in the world. He must accommodate himself with others who are also fighting to exist. The For-Itself (i.e. man) is also for others (pour autrui). He meets others through the body, the physical manifestation of one’s being-in-theworld. • For Sartre, shame is the original feeling that brims about the realization of the existence of others. Sartre uses the example of looking through a keyhole, an act that – according to Sartre – induces a thrill because of the thought that someone might realize that the peeper is looking through the keyhole. In that moment, one sees oneself as other people would see him - as an object. Shame, therefore, is the shame of oneself in the gaze of the other. It is the crushing realization that one is a little more to others than the physical manifestation of one’s body in their sight. • The Other is a scandal: the Other holds the power to regard one as somebody that he is not. The gaze of others exposes the person and makes him weak and fragile, turns him into an object of gaze. • “If there is an Other, whatever or whoever he may be, whatever may be his relations with me, and without his acting upon me in any way except by the pure upsurge of his being – then I have an outside, I have an essence. “ (Being and Nothingness, p. 321) • The only defense left at one’s disposal is to transform others, to turn them into an object for one’s own consciousness and with his own characterization. The self must rid ourselves of others, to escape and to reclaim oneself and the freedom that the Other’s gaze is depriving him of. Consciousness invents this subterfuge to continue to exist as a subject. This is an effort of the self to resist the attempted subordination of the self by the gaze of the Other. Notion of God • Sartre’s notion of God can be summarized in these propositions: God as a perfect being is a contradiction; and the idea of God as a creator denies man of the opportunity to create his own essence through his freedom. Consequently, the affirmation of God's existence would negate the recognition of man's freedom. Hence God's existence must be denied. God the Perfect Being: A Contradiction in Itself ANGELO ESPINAS EXISTENTIALISM FOR DISCUSION PURPOSE ONLY • Sartre conceived God as a perfect being. Such a being can only be one who is at the same time "in-itself" and "for-itself." This follows from the idea of Sartre that there are only two beings, the 'in-self' and the 'for-itself.' The 'in-itself' is full and massive; it manifests perfection and fullness of being, however it is unconscious. The 'for-itself' is conscious and ontologically emerges after the 'in-itself,' it is fundamentally a lack of being and insufficient, this very lack is express in desire. • God to be a perfect being must have the same qualities of the 'in-itself' and the 'for-itself.' But such combination is an impossibility, for God cannot be both conscious and unconscious, he cannot be both fullness of being and lack of being. Thus the idea of God as a Perfect Being is a contradiction. God as the Superior Artisan • Sartre also described God, the Creator as superior artisan. In the factory, he said, the manufacturer already has an idea of every object that he creates. Thus every object in his shop follows exactly what he has in mind. God is like this manufacturer, a superior artisan. As a superior artisan, when he creates, knows exactly what he is creating. • "Thus the concept of man in the mind of God is comparable to the concept of a paper-cutter in the mind of the manufacturer... Thus the individualized man is the realization of a certain concept in the divine intelligence." (THE from EE. p. 35.) • When God created man he knows exactly the nature of man, and man cannot be but what God created him to be. Sartre opposed such view for to accept God as a creator is to deprive man of the opportunity to create himself. If God does not exist there is nobody to define human nature. • It is therefore necessary to deny his existence. "If God does not exist, there is at least one being in whom existence precedes essence, a being who exists before he can be defined by any concept and that this being is man." (THE from EE p. 35.) Sartre’s Atheism • What influenced Sartre to be an atheist? What triggered this atheistic stand? We find part of the answer in his autobiography, Les Mots (The Words). From his autobiography we see that just like any existentialist whose philosophy was very much influenced by his experiences and personal life, Sartre philosophical stance on God was affected by his early experiences and his personal life. ANGELO ESPINAS EXISTENTIALISM FOR DISCUSION PURPOSE ONLY • First of all, Sartre did not experience a truly Christian life. His grandfather Charles Schweitzer used to ridicule Catholicism and his mother while not approving the latter's attitude on Catholicism, tolerated it. In his autobiography, Sartre admitted that he prayed although he got bored with the holy. He wrote: In my nightshirt, kneeling on bed, with my hands together, I said my prayers every day, but I thought of God less and less often. ("Les Mots" pp. 81-82.) • Sartre's denial of God stems mainly from his childhood experiences, especially on the fact that his elders introduced to him the kind of God that he never needed. He recounted that he was longing for the God who made him for his glory but he could not recognize such God in the fashionable God that was introduced to him. He was looking for a Creator, but instead he was introduced to a "Big Boss." • • I felt myself superfluous, therefore I had to disappear... the more absurd life was, the less bearable was death. I reached out for religion, I longed for it, was the remedy. Had it been denied of me I would have invented it myself. Raised in the catholic faith, I learned that the Almighty had made me for his glory. That was more than I dared dream. But later, I did not recognize in the fashionable God in whom I was told to believe the one whom my soul was awaiting. I needed a Creator, I was given a Big Boss.The two were one but I did not realize it. I was serving without zeal, the Idol of the Pharisees. (Les Mots.) • The kind of God that he encountered in his early life was like his grandfather, a "Big Boss" who would look at him in a very strange manner, that the only fitting reaction is one of rebellion. In his autobiography Sartre describes it this way: o For several years longer, I kept up public relations with the Almighty; in private I stopped associating with him. Only once I had the feeling that He existed. I had been playing with matches and had burnt a mat; I was busy covering up my crime when suddenly God saw me. I felt His gaze inside my head and on my hands; I turned round and round in the bathroom horribly visible, a living target. I was saved by indignation; I grew angry at such a crude lack of tact, and blasphemed, muttering like my grandfather: "Sacre nom de Dieu de nom de Dieu de nom de Dieu," He never looked at me again. (Les Mots.) • Hence much of Sartre's negative attitude towards religion and God were influenced and triggered by this experience, which he called "misunderstanding," "mistake" "accident." ANGELO ESPINAS EXISTENTIALISM FOR DISCUSION PURPOSE ONLY o Whenever anyone speaks to me about Him today, I say with the easy amusement of an old beau who meets a former belle: Fifty years ago, had it not been for that misunderstanding, that mistake, the accident that separated us, there might have been something between us. (Les Mots.) • If Sartre carried on his denial of God to the end even though it is not demonstrated apodictically, it is because it is necessary, necessary both philosophically for his philosophical stance on freedom and personally, for nothing will change if one denies God.