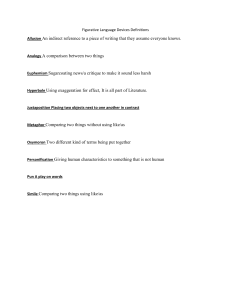

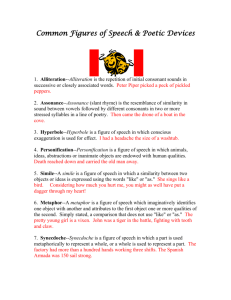

5 Common Types of Poetic Device and their Uses: Jodie Lee, English Tutor and HSC All Rounder take us through the most common types of poetic devices and how to use them. With this handy guide, your poetic analysis will start sounding like... poetry! English Tutor and HSC all-rounder, Jodie Lee, takes us through 5 common types of Poetic Devices and their Uses, to help you through your HSC English journey. We cover five types of common poetic devices and their uses to help you through your HSC: Alliteration Caesura and enjambment Imagery Juxtaposition and oxymoron Personification and Pathetic fallacy Writing an analysis of poetry without knowing poetic devices is like solving a Rubik’s cube with no hands: you just wouldn’t do it. Memorising them is one thing but understanding their effect on the audience is harder still. But if you believe learning the techniques to be a lost cause, think again. Here are five useful types of poetic devices to help you get started on your HSC English journey. Alliteration Alliteration comes from the Latin phrase littera, meaning “letter of the alphabet”. It‘s the repeated sound at the beginning of a string of words. Think of Dunkin’ Donuts and Krispy Kreme. You’re more likely to remember them, which only recalls your fantasised image of those delicious jam doughnuts. In the same way, poetry can become more musical and memorable as the repeating sound is often pleasurable to hear out loud. Example: “Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary.” —Edgar Allen Poe, “The Raven” Caesura and enjambment Caesura is the Latin word, literally meaning “a cutting”. This is as if someone were to say, “Stop!” in the middle of their sentence. By disrupting the rhythm of the poem, you pay the line more attention due to the dramatic, staccato effect. Example: “Nuts, bolts, nails, car-keys. A fount of broken type.” —Ciaran Carson, “Belfast Confetti” Enjambment is of French origin and means “to stride over”. It means to continue sentences beyond the end of one line. Think of the way we text. If the sender breaks up their complete sentences, the receiver might sit there, eyes glued to the phone, and wait in anticipation for the coming texts. It causes your eyes to follow onto the next line to get closure while still holding onto the idea expressed. Example: “April is the cruellest month, breeding Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing Memory and desire, stirring Dull roots with spring rain.” —T.S. Elliot, “The Waste Land” Imagery Imagery literally means language that produces images. I could tell you that it’s raining outside, or instead, describe heavy rain hitting the metal rooftop and the smell of damp earth. Not only does this create a more striking image of the scene, but it also evokes certain emotions attached to what your senses imagine. Example: “Blue! ‘Tis the life of waters–ocean And all its vassal streams: pools numberless May rage, and foam, and fret, but never can Subside if not to dark-blue nativeness.” —John Keats, “Blue! ‘Tis the Light of Heaven” Juxtaposition and oxymoron Juxtaposition comes from the Latin “iuxta” which means to be beside or very near. Like its namesake, it’s when two contrasting ideas are placed closely together, such as light and darkness, life and death, or savoury ketchup and sweet vanilla ice cream. It creates tension and contrast, and can also be a powerful way to express an idea as you can compare it to something else. Example: “Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray. Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage against the dying of the light.” —Dylan Thomas, “Good Night” Oxymoron is a type of juxtaposition, and it’s really more of a direct, paradoxical comparison. This makes sense when you consider its Greek origin, “oxumōron”, which means “pointedly foolish”. Some oxymorons include the living dead and deafening silence. It’s provocative and engaging in that we seek to understand what the oxymoron could possibly mean. Example: “Why, then, O brawling love! O loving hate! O anything, of nothing first create! O heavy lightness! Serious vanity!” —William Shakespeare, “Romeo and Juliet” Personification and pathetic fallacy Personification is what it sounds like: a figurative language tool that gives ideas, objects or animals human characteristics. Death is often personified as a malevolent and destructive force, especially with the Grim Reaper. It adds a human element, communicates ideas more vividly, and connects us to things we can’t normally relate to. Example: “Because I could not stop for Death – He kindly stopped for me – The Carriage held but just Ourselves – And Immortality.” —Emily Dickinson, “Because I could not stop for Death” Pathetic fallacy was coined to originally mean “emotional falseness”. In fact, it is a type of personification where nature is given human attributes, such as leaves “dancing” in the wind. It’s usually done to evoke emotions from the audience or project the emotions of the speaker. Imagine stormy clouds on a bad day—you might describe them as “sullen” to reflect your mood. Example: “The sullen wind was soon awake, It tore the elm-tops down for spite, and did its worst to vex the lake.” —Robert Browning, “Porphyria’s Lover”