American Economic Association

Tax Compliance and Loss Aversion

Author(s): Per Engström, Katarina Nordblom, Henry Ohlsson and Annika Persson

Source: American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, Vol. 7, No. 4 (November 2015), pp.

132-164

Published by: American Economic Association

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24739159

Accessed: 27-10-2019 18:36 UTC

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

American Economic Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to American Economic Journal: Economic Policy

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

American Economie Journal: Economie Policy 2015, 7(4): 132-164

http://dx.doi. org/10.1257/pol.20130134

Tax Compliance and Loss Aversion1

By Per Engström, Katarina Nordblom,

Henry Ohlsson, and Annika Persson*

We study if taxpayers are loss averse when filing returns. Preliminary

deficits might be viewed as losses assuming zero preliminary bal

ances as reference points. Swedish taxpayers can to try to escape

such losses by claiming deductions after receiving information about

the preliminary balance. Using a regression kink and discontinu

ity approach, we study data for 3.6 million Swedish taxpayers for

2006. There are strong causal effects of preliminary tax deficits on

the probability of claiming deductions. Compliance will increase and

auditing costs will be reduced if preliminary taxes are calibrated so

that most taxpayers receive refunds.

[J EL H24, H26j

Two same

taxpayers,

A according

and B, are

about

to filethey

their

tax from

returns.

They

both have the

income and

to the

information

receive

the Tax

Agency

they are both supposed to pay $30,000 in total taxes. However, their employers have

already withheld taxes at source during the year; A's employer $29,000 and B's

$31,000. Hence, A has a preliminary balance of $ 1,000 due, while B will get a refund

of the same amount. According to standard neoclassical theory, both would behave

in the same manner since they both end up with the same tax liability of $30,000. We

find, however, that they behave significantly different: A is much more likely than B

to claim deductions in order to reduce his tax liability. This finding is not consistent

with neoclassical theory. On the other hand, reference dependence and loss aver

sion—as defined in Prospect Theory by Kahneman and Tversky (1979) and Tversky

* Engström: Department of Economics, Uppsala University, P.O. Box 513, SE-751 20 Uppsala, Sweden

and Uppsala Center for Fiscal Studies (UCFS) (e-mail: per.engstrom@nek.uu.se); Nordblom: Department

of Economics, University of Gothenburg, P.O. Box 640, SE-405 30 Gothenburg, Sweden, and UCFS (e-mail:

katarina.nordblom@economics.gu.se); Ohlsson: Department of Economics, Uppsala University, P.O. Box 513,

SE-751 20 Uppsala, Sweden, and UCFS (e-mail: henry.ohlsson@nek.uu.se); Persson: The Swedish Tax Agency,

SE-171 94 Solna, Sweden (e-mail: annika.persson@skatteverket.se). We would like to thank Spencer Bastani,

Fredrik Carlsson, Edoardo Di Porto, Martin Dufwenberg, Olof Johansson-Stenman, Martin Kocher, David Lee,

Mikael Lindahl, Oskar Nordstrom Skans, Matthias Sutter, Mäns Söderbom, Benno Torgler, Clive Werdt, Magnus

Wikström, seminar participants in Aarhus, Deakin; Melbourne, Gothenburg, Växjö, University of New South Wales

(UNSW); Sydney, VATT; Helsinki, UCFS, the UCFS Scientific Advisory Board, the European Commission, the

Finnish and the Swedish Tax Agencies as well as conference participants at the International Institute of Public

Finance (IIPF) 2013 Taormina conference, the Shadow 2011 Münster conference, and the 2011 Swedish Economics

Meeting in Uppsala for their valuable comments and suggestions. We are also grateful to three anonymous referees

for their helpful comments. Financial support to UCFS from Riksbankens Jubileumsfond (RJ), the Swedish Council

for Working Life and Social Research (FAS), and the Swedish Tax Agency is gratefully acknowledged. Nordblom

also acknowledges financial support from the Swedish Research Council, project no. 421-2010-1420, and from RJ.

Some of the work was done as Ohlsson enjoyed the hospitality of the School of Economics, UNSW, Sydney and

the Department of Economics, University of Melbourne during his sabbatical. Financial support for the sabbatical

from the Wenner-Gren Foundations is gratefully acknowledged.

TGo to http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/pol.20130134 to visit the article page for additional materials and author

disclosure statement(s) or to comment in the online discussion forum.

132

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VOL. 7 NO. 4 ENGSTROM ETAL.: TAX COMPLIANCE AND LOSS AVERSION 133

0.08

o

|

■o

0.06-1

co

O)

c

o

ffi

o

-O

0

02-1

,

,

,

0.00-1

.

,

,

-3,000 -2,000 -1,000 0 1,000 2,000 3,000

Preliminary deficit, SEK

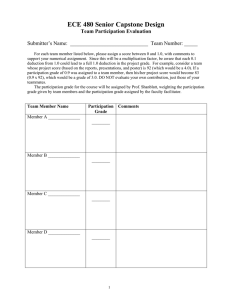

Figure 1. Share Claiming a Deduction as a Function of the Preliminary Deficit

and Kahneman (1992)—predict such outcomes. Loss averse individuals value losses

(in comparison to a reference point) more than gains by the same amount. In ou

particular application it is likely that a zero balance in preliminary tax payments

such a reference point. An individual with a preliminary deficit (A) will, therefo

perceive a higher marginal value of extra income than someone with a preliminar

surplus of the same amount (B). Those with a deficit would consequently be mor

inclined to take (legal or illegal) actions in order to reduce their tax liability. Th

line of reasoning is put forward in some theoretical studies in the area of prospe

theory and tax compliance.1 Recent empirical evidence by Rees-Jones (2014) poin

in the same direction.

We study the entire population of Swedish taxpayers of working age and their

behavior when filing their income tax returns. The high quality tax return data concern

the income year 2006 and the tax assessment year is 2007. The Tax Agency reports

a preliminary balance in taxes due to the taxpayer before the income tax return has

to be filed. The specific action we study is whether and how much taxpayers claim

deductions for "other expenses for earning employment income." Such deductions

may be accurate, but may also express noncompliance: The Swedish Tax Agency

reports that almost all audited claimed deductions for "other expenses for earning

employment income" were rejected.2

Figure 1 shows that the probability of claiming a deduction is indeed higher for

taxpayers with a preliminary deficit than for those with a preliminary surplus. Each

data point in the figure represents the share for taxpayers with a preliminary deficit

in SEK 300 intervals.3

1 See, e.g., Yaniv (1999), Bernasconi and Zanardi (2004), and Dhami and al-Nowaihi (2007).

2See Riksskatteverket (RSV) (2001). A more recent follow-up in 2006 drew a random sample of claimed

deductions. There were mistakes in 93 percent of the cases.

3 The average SEK/USD exchange rate was SEK 7.38 per USD in 2006.

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

134 AMERICAN ECONOMIC JOURNAL: ECONOMIC POUCY NOVEMBER 2015

We design a quasi-experiment using a regression kink and discontinu

to analyze whether the pattern in Figure 1 really is a causal one. This

technique allows us to eliminate potential problems of endogeneity an

in ways that most previous empirical studies have not been able to

behavior to be consistent with loss aversion in the following sense: ta

have a preliminary deficit (taxes due) are more likely to claim deductio

expenses" than those who have a preliminary surplus (tax refund). Th

larger unconditional amounts, on average. None of the covariates exh

evolution around zero preliminary balance. Hence, selection is unlikely

that we have found evidence of a clear departure from neoclassical as

Furthermore, we argue that loss aversion is the most likely candidate

the result. To further strengthen the causal interpretation of our find

use an alternative instrumental variable (IV) approach. The difference

actual and preliminary tax rates is used as an instrument when estimat

ity models for claiming a deduction. The results are confirmed using t

Our conclusion is, therefore, that there is evidence of loss aversion.

We also estimate the coefficient of loss aversion in our empirical an

estimate, A = 2.17 for the full sample, is very close to the estimate r

Tversky and Kahneman (1992), Â = 2.25.

We thus find a causal link from loss aversion to tax filing behavior

some other previous empirical studies also suggesting that people who

too little in advance preliminary taxes are less likely to comply than th

paid too much. These studies do not, however, establish causality.4 To

edge there is only one other study which also has established causality

aversion and tax filing behavior. Rees-Jones (2014) studies tax shelter

US taxpayers. While we study a specific reaction to exogenous ex ante

about taxes due, he uses ex post data to conclude that loss averse taxp

avoid ending up with taxes due.

The major contribution of the paper is thus that we find tax filing

be consistent with loss aversion, which in turn has important policy

Tax authorities could withhold a little bit too much in order to keep

surplus side. This could increase tax payments and reduce the need for

deductions are signs of noncompliance, it could also enhance tax mora

in the long run (Nordblom and Zantac 2012). However, overwithholdin

be used too ambitiously, as that itself could cause credibility problems.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: We discuss pros

and its application to tax compliance in Section I. Section II describes

the institutional setting. We then present a simple theoretical model in

which the taxpayers' decisions are studied. The model provides predic

empirical analysis. Some descriptive results are presented in Section IV

presents the empirical results using the regression kink and discontinu

4See, e.g., Chang and Schultz, Jr. (1990) and Persson (2003). There are also experimental stu

that advance payments actually matter for compliance, e.g., Robben et al. (1990), Schepanski a

and Copeland and Cuccia (2002).

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VOL 7 NO. 4 ENGSTROM ET AL: TAX COMPUANCE AND LOSS AVERSION 135

A robustness check using an IV approach and our estimates of the coef

aversion are found in Section VI. Section VII concludes the paper.

I. Prospect Theory

A. Theory and Evidence

Kahneman and Tversky (1979) defined prospect theory. The eleme

marily use are reference dependence and loss aversion. Hence, people

comes as gains and losses compared to some reference point and c

as more salient than gains. This implies that the utility function is

reference point. Although the concept of loss aversion was first intro

settings (and has been proposed to explain parts of observed risk aver

and Kahneman (1991) show that it can also explain behavior in the abs

Many experimental studies have followed the famous mug exp

Kahneman, Knetsch, and Thaler ( 1990),5 showing evidence of an endow

Tversky and Kahneman (1992); Schmidt and Traub (2002); Gächter, J

Herrmann (2007); Abdellaoui, Bleichrodt, and Paraschiv (2007); an

Bleichrodt, and L'Haridon (2008) are some studies finding evidence o

to various extent in within-subject comparisons. They let the subjects

rather few university students) make several choices and conclude t

individual makes different choices depending on gains or losses. Cam

and DellaVigna (2009) discuss several field experiments that have fou

to be consistent with loss aversion and other components of prospec

(2003, 2004) finds in his field experiments that there is a pronounce

effect (like the one found by Kahneman, Knetsch, and Thaler 1990)

perienced subjects, but that experienced subjects behave in line with

theory. However, Pope and Schweitzer (2011) find that even highly

professional golfers exhibit loss aversion. Crawford and Meng (2011) f

dependence among New York cab drivers in a study where they con

tion in an elegant way. Fehr and Goette (2007) study bicycle messen

that a majority are loss averse, which explains their behavioral resp

increase. Genesove and Mayer (2001), who study sellers of residentia

find loss aversion where the purchase price seems to be the relevant r

B. Tax Compliance and Prospect Theory

Some theoretical studies in the area of prospect theory that focus o

ance suggest the following line of reasoning: Loss aversion implies t

vidual values losses compared with the reference point more than gai

amount. An individual with a preliminary tax deficit (more taxes du

fore, perceive a higher marginal value of extra income than an indi

5 Half of the subjects were given a mug for which they were then asked to give a selling p

asked for their willingness to pay for a mug. The price mentioned by the former group widel

mentioned by the latter.

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

136 AMERICAN ECONOMIC JOURNAL: ECONOMIC POUCY NOVEMBER 2015

preliminary tax surplus (some taxes will be refunded) of the s

with a preliminary tax deficit would consequently be more inc

chance of noncompliance.6 Although Elffers and Hessing (1997

payments promote compliance, they also point to the fact that w

may make people feel wrongly treated, which has an opposing e

Experimental studies find that advance tax payments actually

ance in a fashion consistent with loss aversion.7 Previous studi

data suggest that people who have paid too little in preliminar

less likely to comply than those who have paid too much.8 Non

studies can, however, establish a causal relationship.9

Rees-Jones (2014) is a recent contribution that is relevant to o

lishes a causal relationship between loss aversion and tax shelte

to reduce tax liability, and concludes that taxpayers behave in a

when filing their tax returns. His approach is different from o

ing system is different from the Swedish. He considers measu

by the taxpayer and studies the resulting balance due. The con

implied sheltering is higher in the loss domain although he cann

specific actions. In our study, we concentrate on one specific tax

which we can observe, namely claiming a deduction for other ex

employment income. We study how this is affected by fully ex

from the Swedish Tax Agency before tax returns are to be file

reveals whether you initially are in the loss domain or in the g

how much. We drop taxpayers who we suspect might have taken

measures from our dataset to get the mechanisms as clean as po

below. Hence, our analysis is more direct than the approach in

II. Data and Institutional Setting

Our entire dataset covers all 4.7 million Swedes 16-67 year

ment income and without any business income, filing their tax

the income year 2006. We have access to a limited number o

employment income, marginal tax rate, gender, age, claimed d

expenses for earning employment income," and the preliminar

due.

Taxable employment income includes salaries, social insur

fits (such as sickness benefits and parental benefits), and unem

reduced by the basic exemption.10 It also includes pensions, bu

6See, e.g., Elffers and Hessing (1997), Yaniv (1999), Dhami and al-Nowaihi (20

Zanardi (2004).

7See, e.g., Kirchler and Maciejovsky (2001), Schepanski and Shearer (1995), R

Copeland and Cuccia (2002).

See, e.g., Cox and Plumley (1988), Chang and Schultz, Jr. (1990), and Persson (200

9 That receiving a refund or having taxes due affects people's behavior has previously

ing other issues than compliance. Feenberg and Skinner (1989) find that owing a balance

prompts greater contributions to individual retirement accounts. Feldman (2010), howev

tax withholding while marginal tax rates were preserved, instead leads to reduced IRA c

10We do not have information on employment status, such as unemployment or sick

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VOL. 7 NO. 4 ENGSTRÖM ET AL.: TAX COMPLIANCE AND LOSS AVERSION 137

expected to have salary income and, therefore, any other expenses tor earnin

employment income. This explains the upper age limit in our sample.

The decision we study in this paper is whether or not the taxpayer claims

deduction for "other expenses for earning employment income" when filing their

tax return. Filing the tax return is one event in the annual sequence of taxpaying:1

employers withdraw preliminary taxes before the salary is paid to the employees

The Tax Agency decides on tax tables specifying employee tax withholdings, i.e.,

the amount that should be submitted directly to the Tax Agency.12 Hence, taxpayin

is typically perceived as automatic for Swedish taxpayers, i.e., there is no need to

take any action of their own.

In April the following year, the Tax Agency sends a preliminary income tax return

to the taxpayer. This tax return is based on the statements of income that the Tax

Agency has received from employers, banks, etc. Virtually all incomes are speci

fied on the tax return form, based on information reported through the legislated

reporting system. Moreover, the Tax Agency calculates a preliminary balance in

taxes due (actual tax liability—preliminary payments made), which is also written

on the tax return. Since preliminary income tax is withheld at source according to

the Tax Agency's tables, the preliminary balance is close to zero for most taxpayers

The preliminary balance may, however, show a deficit (more taxes due) or a surplu

(there will be a tax refund). When filing a tax return, the taxpayer may add missin

information. Because of the extensive reporting by employers etc., the taxpayer doe

not usually have much information to add, but could for instance claim deductions

for "other expenses for earning employment income."

The filing deadline is May 2. After this date, the Tax Agency calculates the fina

tax for the taxpayer, which depending on the preliminary tax payments may be

either a surplus or a deficit. Surpluses are refunded to the taxpayer's bank account i

June or August. If there is a deficit, the taxpayer has to pay the balance in November

or December.13 For the taxpayer there is almost no administrative cost in either case.

In case of a deficit, the taxpayer receives a payment slip from the Tax Agency.

The Swedish income tax system is dual in nature. Capital income is taxed at a flat

national rate of 30 percent, while employment income is taxed progressively and

by both the local governments (municipalities and county councils) and the central

government. Moreover, income taxes are based on individual, and not on household

income. Most Swedes only pay the local employment income tax, which in 2006

ranged from 28.80 to 34.24 percent. The local government employment income

tax consists of two parts—the municipality employment income tax and the county

council employment income tax. High-income earners pay an additional 20 percent

in central government employment income tax on the part of their taxable emplo

ment income that exceeds a threshold that was SEK 306,000 in 2006 and another

11 See also the information from the Tax Agency reproduced in online Appendix A.

12Analogous principles apply for capital income taxation (interest received and paid, dividends, etc.). As

Sweden has a dual income tax system, all capital incomes are taxed at source with 30 percent.

13 The interest paid on surpluses and the interest levied on deficits are independent of the filing date. However

for deficits smaller than SEK 20.000, no interest has to be paid if the taxes due are paid by May 4th at the latest.

deficit is an interest-free loan for quite some time whereas a surplus yields interest from quite early on during th

year. Online Appendix A presents the details that applied during the assessment year 2007. Therefore, the issues

that Slemrod et al. (1997) and Jones (2012) discuss for the United States do not arise in the same way in Sweden.

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

138 AMERICAN ECONOMIC JOURNAL: ECONOMIC POUCY NOVEMBER 2015

5 percent on the taxable employment income that exceeds

was SEK 460,600 in 2006.14 Hence, the Swedish employm

gressive with three brackets. Threshold incomes are the sam

whereas the local employment income tax varies across the c

About 75 percent of the taxpayers in the 4.7 million

employment income lower than SEK 306,000 and therefore

ment income tax, which on average is 32.8 percent. The sh

have a taxable employment income in the interval SEK 3

18 percent. These taxpayers pay the local income tax plus a

their taxable employment income in excess of SEK 306,0

The marginal tax rate in this second tax bracket is 52.8 per

remaining 6 percent of the taxpayers have a taxable emplo

than SEK 460,600. These taxpayers pay the local governmen

central government income tax of 20 percent of taxable emp

SEK 306,000 and an additional 5 percent on taxable emp

SEK 460,600. The average marginal tax rate in this third tax

Final taxes on employment income are determined by the

earned during the full year. However, preliminary taxes on

paid monthly by employers and are estimated assuming the

employment income every month throughout the year. Dev

nary and final taxes are in most cases small and exogenous t

So why may preliminary tax balances deviate from zero at

government part of the employment income tax is levied is a

actual tax rates are set with two decimals of a percentage (fo

or 31.12 percent). The tables for preliminary taxes are, h

ing integer percentages tax rates at source (for example, 31

municipalities for which the tabled tax rates at source are ab

tend to pay too much in preliminary taxes. The opposite ap

municipalities with actual rates higher than the rates used a

that a higher share of those having the preliminary tax rat

preliminary surpluses than those having the preliminary t

wards. The difference is 3.1 percentage points.

The local tax rate is the result of decisions in two separate

ipality and the county council (covering several municipaliti

290 municipalities in 20 counties. Thus, it would be extreme

municipality to set the local tax rate strategically trying to

ples for taxation at source. This would require correctly pre

response of the county council. It would be even more diffic

cil to act strategically in this respect, since it would involve

of several municipalities. It would, consequently, also be very

to predict where to move to take advantage of a lower preli

it should be reasonable to assume that the actual tax rate is

individual taxpayer.

1 In 2006, it corresponded to US$41,460 and US$62,410, respectively.

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VOL. 7 NO. 4 ENGSTROM ETAL. : TAX COMPLIANCE AND LOSS AVERSION 139

0.02:

Preliminary tax rate above actual tax rate

0.005

-6

-4-2

0

2

Preliminary

Figure 2. Relative Frequency Distributions for Taxpayers with

Preliminary Tax Rates Rounded Upwards and Downwards

From Figure 2 it is also apparent that the rounding error is hardly the only

of deviation between preliminary taxes and final taxes. The progressive centra

ernment part of the employment income tax is another possible reason why t

ance may deviate from zero. Employers withhold preliminary taxes according t

Tax Agency's tax tables, which assume that the income stays the same every m

If income varies a lot during the year, the tax withholdings may be misjudged

preliminary taxes may be higher or lower than final taxes. For taxpayers cl

the thresholds between the tax brackets, unanticipated events may create a no

balance. Benefits from the social insurance systems are included in employm

income, but the replacement rates are below 100 percent. Absenteeism may

fore affect the preliminary balance and so may overtime work. A taxpayer

varying employment income over the year will tend not to pay the same amo

preliminary taxes as a taxpayer with the same annual employment income e

distributed over the year. Flaving several employers might also result in insuf

withholdings at source. If every employer withdraws taxes as if they were th

employer, progressivity may result in not enough preliminary taxes being paid

Deviations from a zero preliminary balance may also arise from capital inc

taxation. Interest on loans is deductible at the 30 percent capital income tax

which is not automatically taken into account in the preliminary taxes. Taxp

who pay deductible interest may therefore have preliminary surpluses. Unfortunat

we do not know the taxpayers' deductible interest payments, so we cannot dir

control for this in our analysis.15 This is probably an important source of he

neity in the preliminary balances and may explain why a majority have a prelim

15 On a macro level during 2006, however, 4.7 million of the total Swedish population had deductible in

payments, i.e., a majority of the taxpayers.

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

140 AMERICAN ECONOMIC JOURNAL: ECONOMIC POLICY NOVEMBER 2015

Table 1—Construction of the Sample

N

AN

Original sample 4,674,003

Advance payments - 310,094

Missing values for preliminary deficit —281

Taxable employment income < SEK 100,000 —735,952

Taxable employment income > SEK 1,000,000 —16,704

Full sample 3,610,972

surplus.

for

the

the

total

Since

most

taxpayer

tax

taxpayer

to

precisely

liability.

Our objective is to study th

fore want to exclude individ

This is an important differe

means to affect the balance

Agency to be exogenous to

exclude some taxpayers from

Our

original

sample

consi

ment income and without a

taxpayers as they can affec

then exclude taxpayers who

the Tax Agency at their ow

The reason is that these adva

deductions. The preliminary

ers. We exclude them from t

analysis.

Finally, only taxpayers with "normal" annual taxable employment incomes are

included in our sample. We interpret normal annual taxable employment income to

be in the interval SEK 100,000-1,000,000.17 These selection criteria leave us with

a full sample of 3.6 million taxpayers. Descriptive statistics for the full sample are

presented in Table 2.

These 3.6 million taxpayers are studied with respect to deduction behavior.

Taxable employment income could be reduced through approved deductions for

"other expenses for earning employment income" exceeding SEK 1,000 during the

income year 2006. The expenses thus did not have to be large and the specifications

16 There are incentives for taxpayers with preliminary deficits larger than SEK 20,000 to make advance tax

payments before mid-February to avoid having to pay extra interest. See online Appendix A for more information

on interest rates, etc.

17This corresponds to an annual income of US$13,550-$135,000 in 2006. Less than 0.5 percent of our sample

had incomes exceeding SEK 1,000,000. On the other hand, about one-sixth had an income lower than SEK 100,000.

However, we need to exclude those with the lowest incomes since there will be a nontrivial share that bunch at

exactly zero preliminary balance simply because they have zero tax liability. Where the exact cutoff should be is,

however, not easily determined. We therefore made robustness checks based on a SEK 50,000 cutoff instead and

the results remained almost the same.

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VOL. 7 NO. 4 ENGSTRÖM ETAL. : TAX COMPLIANCE AND LOSS AVERSION 141

Table 2—Descriptive Statistics

Full sample Maximum bandwidth sample*

Preliminary

deficit

Preliminary

surplus

Preliminary

All

deficit

Preliminary

surplus

All

810,690

2,800,282

370,929

822,686

Deducting, fraction

0.062

0.044

0.048

0.061

0.042

Deduction, SEK

1,000, conditional

4.72

3.56

3.89

4.21

3.71

3.91

(4.32)

(3.34)

(3.69)

(3.81)

(3.40)

(3.58)

Number of observations

Preliminary balance,

SEK 1,000

Taxable employment

income, SEK 1,000

-10.76

(51.23)

280.1

(136.1)

0.48

Men, fraction

Age, years

Marginal tax rate,

percent

Municipal tax rate,

percent

3,610,972

6.55

2.67

(6.76)

(26.02)

269.1

(115.1)

272.1

(120.1)

0.49

0.49

-1.29

(1.14)

278.1

(131.1)

0.49

1,193,615

0.048

1.61

0.71

(1.15)

(1.77)

277.1

(119.1)

0.50

277.1

(123.1)

0.49

46.8

42.0

43.1

44.9

43.1

43.7

(12.5)

(12.1)

(12.3)

(12.5)

(12.3)

(12.4

39.6

37.5

38.0

38.7

37.9

38.1

(8.8)

(9.1)

(9.6)

(9.1)

(9.3)

32.8

32.8

32.8

32.8

32.8

32.8

(1.0)

(1.0)

(1.0)

(1.0)

(1.0)

(1.0)

(10.0)

Note: Mean (standard deviation).

*Sample selection criterion: weighted preliminary balance in the interval ± SEK 3,000.

were quite vague.18 Hence, there was room for (small scale) tax noncompliance by

means of this deduction.

There are some studies of randomly audited claimed deductions for "other expens

es."19 The overall finding is that 90-95 percent of the claims were not approved. In

some cases, the taxpayer may simply not understand the rules and believe that he

is entitled to the deduction. The taxpayer may knowingly take a chance in other

cases. We cannot, therefore, know whether certain deductions are due to tax evasion,

tax avoidance, or something else. Some claimed deductions are, however, clearly

not due to noncompliance. This is likely to be true especially for large claimed

deductions. Large deductions are more often accurate than small (Persson 2003).

This is an important reason for only including relatively small deductions for "other

expenses." Hence, we concentrate on deductions smaller than SEK 20,000.

It was almost without risk to claim small incorrect deductions in 2007 as the

audit probability was very low for small claimed amounts. Moreover, the taxpayer

was only required to pay the increased tax liability if the claimed deduction was

audited and not approved. There were no fines for incorrectly claimed deductions of

small amounts.20 Neither were there any fines for large rejected deductions provided

18 Some examples that could be approved are expenses for safety equipment, safety clothes, tools, and instru

ments related to work not paid for by the employer, expenses for an office if the employer does not provide one (an

office at home is not approved in general), expenses for books and journals related to work for some occupations if

not paid for by the employer, and expenses for phone calls related to work if not paid for by the employer (not the

phone and not fixed costs for phone service). No receipts have to be submitted to the Tax Agency, but they need to

be ready to show in case of an audit.

19See Riksskatteverket (2001) and Persson (2003).

20The tax law has changed since. The threshold value that expenses have to exceed before the tax liability decreases

was increased considerably. It is no longer possible to claim deductions of amounts smaller than SEK 5,000.

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

142 AMERICAN ECONOMIC JOURNAL: ECONOMIC POLICY NOVEMBER 2015

0.25

0.20

0.15

0.10

0.05

0.00

6

8

10

12

14

Deducted

amount,

SEK

Figure 3. Frequency Distribution of Deducted Amounts

that the taxpayer could prove having had the expenses for which the deduction was

claimed. The choice to claim a deduction was, therefore, completely without risk.

The 3.6 million taxpayers in our full sample should not have had perfect knowl

edge or control of their preliminary deficit. The closer the preliminary balance is to

zero, the more likely it should be that it is truly random whether one ends up with a

surplus or a deficit. In part of the analysis we, therefore, focus on taxpayers with a

preliminary balance in the interval SEK ± 3,000. There are 1.2 million subjects in

this subsample, which we label the maximum bandwidth sample. Descriptive statis

tics for this sample are also presented in Table 2.21 Our approach is that the deduc

tion behavior of these taxpayers can be viewed as a quasi-experiment.

In Table 2, we note that a larger fraction with a preliminary deficit than with a pre

liminary surplus claim the deduction, in both the full and the maximum bandwidth

sample. We also see that, conditional on claiming a deduction, taxpayers with a

preliminary deficit on average claim larger deductions than those with a preliminary

surplus. Hence, the unconditional deduction is almost twice as large on the deficit

side as on the surplus side. Figure 3 shows the frequency distribution of deductions

in the full sample. Most deductions are fairly small and those in the gain domain

(the dotted line) are more concentrated than those in the loss domain (the solid line).

Suppose that those in deficit had behaved as those in surplus on both the extensive

and intensive margin. The overall tax revenue loss due to the deduction would then

be 17 percent lower (and the one stemming from those with a deficit would be

46 percent lower).

21 This sample is based on the preliminary deficit being weighted by the taxpayer's employment income for

reasons that will be explained in Section IV. Weighting increases the probability of including taxpayers with high

employment income in the sample. Employment income and deduction probability are positively correlated. This is

the reason why the deduction probabilities reported in Table 2 in online Appendix B are slightly higher than those

shown in Figure 1.

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VOL 7 NO. 4 ENGSTRÖM ETAL. : TAX COMPLIANCE AND LOSS AVERSION 143

Just from the descriptives of both samples, we see that among those who ha

a preliminary deficit, the probability of claiming a deduction is about 50 percen

higher than among those who have a preliminary surplus. Due to this and to the f

that they on average claim larger deductions, the average taxpayer on the deficit s

reduces his tax payment by twice as much as the average taxpayer on the surpl

side by means of the deduction.

III. An Illustrative Theoretical Model

The purpose of this section is to provide predictions for our empirical exerci

We apply loss aversion and reference dependence to a simple model of dec

making.

Consider a taxpayer i who is about to file his tax return. He receives information

about his preliminary tax balance on the tax return. Taxpayer i has taxes due if he

has a preliminary deficit, D, > 0, and will receive a refund if he has a preliminary

surplus, D, < 0. He compares the preliminary deficit with his reference point.

There has been a lot of discussion about what the valid reference point should

be.22 Dhami and al-Nowaihi (2007) argue that legal after-tax income should be used

as the reference point. This is related to the idea that the reference point should be

based on rational expectations (Köszegi and Rabin 2006), i.e., how much the tax

payer expects to owe or get refunded. Schepanski and Shearer (1995), however, find

that the current asset position is a more relevant reference point for taxpayers than

the expected asset position. Hence, like in many other areas, status quo seems to be a

natural reference point also when filing tax returns. Also Elffers and Hessing (1997)

and Yaniv (1999) argue for status quo as the reference point when analyzing tax

compliance. Therefore, we assume that a zero balance is the reference point for the

taxpayer when filing their return, an assumption also made by Rees-Jones (2014).23

Hence, if Dt > 0, the taxpayer experiences himself to be in the loss domain. He will

be in the gain domain if D, < 0.

The value function with reference dependence and loss aversion is:

-vD, if D, < 0,

(l)

v(A)

=

-AvD, if D, > 0,

where A > 1 is the coefficient of loss aversion.

We follow, e.g., Benartzi and Thaler (1995), Schmidt and Traub (2002), and

Pope and Schweitzer (2011) and assume a linear value function. This implies con

stant marginal values. We disregard strict concavity in the gain domain and strict

convexity in the loss domain by this assumption. Utility tends, however, to be almost

22 See, e.g., the discussion in Kirchler and Maciejovsky (2001).

23 One could argue that since tax filing is a recurring event, previous preliminary balances may be the relevant

reference point. Since our data does not contain information on previous years and our theoretical model therefore is

a one-period model, we rule out this possibility in the present paper. In Section VB, however, we present sensitivity

analyses allowing the reference point to be endogenous.

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

144 AMERICAN ECONOMIC JOURNAL: ECONOMIC POUCY NOVEMBER 2015

linear over very small intervals. A linear approximation sh

since we limit our analysis to a narrow area around zero.

A. Whether to Deduct or Not

A first step is to predict the probability of claiming a deduction to reduce one's

tax liability.

The taxpayer's only choice is whether or not to claim a deduction of a fixed

amount, ö, which is the same for all taxpayers. We analyze what affects the deduc

tion probability. The amount <5 is sufficiently small to ensure that the taxpayer per

ceives to be at no risk of being audited if he claims the deduction.24

Claiming the deduction ö comes at a certain cost, c,-. This cost varies across tax

payers, ct ^ U[0, c]. It may reflect the administrative cost of claiming the deduction

or the moral cost of doing so if the deduction is not legitimate. The deduction is

worth tö, where t is the constant marginal tax rate.

The taxpayer compares the value of his preliminary tax balance, V(—Dt), to the

value if he claims the deduction, V{tô — Dt) — q. He claims the deduction if the

latter exceeds the former. There are three different domains where the taxpayer may

end up depending on the sign and size of Dt. The three conditions for claiming the

deduction S are:

A: q < vtö if Dt < 0,

(2) B: q < v[tö + D,(A - 1)] if A € (0,f<5],

C: c, < XvtS ifD, > tö.

The value of the deduction in the three cases a

The assumption of a uniformly distributed co

conditions (2) to predict the share of taxpayer

preliminary deficits. The share is increasing in

claiming the deduction in the loss domain is lo

A larger share of the taxpayers should, therefo

the gain domain. For those with a positive bala

should be independent of the preliminary bal

The same applies for those with a large prel

still will have a deficit even after the deducti

Di e (0, f<5], that the share of taxpayers claim

liminary deficit:

A = v[fj + A(A - 1)],

(3)

i = v(A-l)>0.

24Contrary to previous studies of tax compliance, we abstract from detection risks in our model. Our main

results, however, remain valid even if we include a risky choice of noncompliance.

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VOL. 7 NO. 4 ENGSTRÖM ETAL. : TAX COMPUANCE AND LOSS AVERSION 145

Figure 4. The Value of Claiming a Deduction in

Three Cases Depending on the Preliminary Deficit

We then predict the pattern for the share of taxpayers claiming the deduction to b

as shown in Figure 5.

The pattern in Figure 5 can be summarized as follows:

PREDICTION 1 : The share of taxpayers who will claim the deduction 6 is larger

among those with a preliminary deficit than among those with a preliminary surplus.

PREDICTION 2: The probability of claiming the deduction S, as a function of the

preliminary deficit, has the shape as in Figure 5 with kinks at D = 0 and at D = td.

How important is loss aversion in terms of magnitude? Loss aversion implies

that the utility (or value) function is steeper for gains than for losses, but how

much steeper? The coefficient of loss aversion, A, should capture this. There is no

overall consensus on how A should be measured. Tversky and Kahneman (1992

originally defined it as the ratio of utilities: A = — U(— 1) / C/( 1). Köbberling and

Wakker (2005) instead propose the following definition, which is independent of

unit of payment: A = U\{0) / t/[(0). This was also informally suggested by Benartz

and Thaler (1995). The two definitions are equivalent when the value function is

linear. Abdellaoui, Bleichrodt, and Paraschiv (2007) summarize and discuss various

methods of measuring A.

Our approach is different. We observe a large number of people in the gain

domain and in the loss domain. It is, therefore, possible to estimate an aggregate

coefficient of loss aversion. We plot the shares claiming the deduction for each leve

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

146 AMERICAN ECONOMIC JOURNAL: ECONOMIC POUCY NOVEMBER 2015

p(S>0)

tS

Figure 5. Share of Taxpayers Claiming the Deduction Depending on the Preliminary Deficit

of preliminary deficit as sketched in Figure 5. The share claiming the deduction in

the gain domain is:

(4) /J!S0Ac)dc = x

We observe the actual share, X, in our data. Since the cost is assumed to be

formly distributed, (4) is easily solved to yield:

(5)

The share claiming the deduction in the part of the loss domain where D, > tS is:

(6) £tUc)dc = y

A vtô _ y

Equations (5) and (6) then give A = Y/X. Hence, the coefficient of loss aversi

simply the ratio between the two shares claiming the deduction.

PREDICTION 3: If the cost of claiming the deduction, c, ^ f/[0, c], then the

cient of loss aversion, A, is

X - I

X'

where Y is the share claiming the deduction in the part of the loss domain

Dj > tö and X is the share claiming the deduction in the gain domain.

We will use this prediction to estimate the coefficient of loss aversion, A

Section VIB.

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VOL 7 NO. 4 ENGSTRÖM ETAL.: TAX COMPLIANCE AND LOSS AVERSION 147

B. The Amount Deducted

In this subsection, we derive the empirical predictions from a more general

model. We now drop the assumption of an identical deducted amount and instead let

the deducted amount vary between individuals.

Assume the deduction cost function

Ci = C (Si, Ci),

where c is the individual's cost parameter (independent of D by assumption) and 6

is the size of the deduction. F(c, D) is the conditional distribution function of c. As

above, we make the key assumption that F(c,D) = F(c), i.e., that the distribution

of c is independent of D. In addition, we make the following standard assumptions

(in the following, we suppress subindex i):

(s > 0 (deductions are costly)

(ss > 0 (strictly convex cost function)

C > 0 and (sc > 0 for <5 > 0 (costs and marginal costs of deductions increase in c)

c = Ç(<5, c) is independent of D.

We stick to the same linear value function as in Section IIIA, so the marginal value

of a deduction is MVd = Avt on the deficit side and MVS = vt on the surplus side.

Given A > 1, it follows that MVd > MVS.

The Intensive Margin.—Conditional on claiming a positive deduction, the size (S )

will generally be given by the condition:

(7) MV = (s(S,c).

However, some individuals will bunch at

value of a deduction takes a discontinuou

taxpayer who bunches at zero, the above

effective marginal value MVb e [MVS, MV

Differentiation of equation (7) gives

<8> mv > °

LEMMA 1 : Consider an individual i wh

less of his initial deficit (Dfi Then 8i{D

make a weakly larger deduction on the de

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

148 AMERICAN ECONOMIC JOURNAL: ECONOMIC POUCY NOVEMBER 2015

PROOF:

The result follows directly from equation (8) since MV(D, > 0) is either M

MVj,, or MVS (depending on the ex post position), while MV(Dl < 0) - MVS.

The Extensive Margin.—When determining whether a taxpayer will claim a d

tion or not, we need to compare the total value of a deduction with the total cost

total cost is independent of D by assumption, so we only need to focus on the v

The total value (V) of a deduction is simply the integral over marginal values, i.e

(9) V(D, S) = f°_tSMVdx.

LEMMA 2: (/) The value of a deduction will kink upwards at D = 0 when A

(ii) The value of making a deduction is always higher for D > 0 than for D

PROOF:

(i) Equation (9) directly gives

Vd(D, Ö) = OifD < 0

Vd(D,S) = MVd - MVS = (A - l)r > OifD = 0.

(ii) This follows directly from equation (9) and the fact that MVd > MVS. I

Empirical Predictions.—The model renders two empirical predictions that can

be taken directly to data. However, before deriving those, we need one last lemma

LEMMA 3: A taxpayer i with a given cl will make weakly larger deductions when

starting on the deficit side (D, > 0) compared with the surplus side (D, < 0).

PROOF:

Follows directly from Lemma 1 and 2 above. ■

For the extensive margin we get the following empirical prediction, which

analogous to Predictions 1 and 2 above.

PREDICTION 4: (/) The share of individuals who claim a positive deduction

kink upwards at D — 0. (ii) The fraction of individuals who claim a deduction

always be higher on the deficit side.

PROOF:

Follows directly from Lemma 2 when assuming that F(c) has support in the rel

evant domain. I

It is natural that the (negative) kink in deduction we found at D = tô (see

Figure 5) will not prevail in this more general model where different taxpayers make

deductions of different sizes.

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VOL 7 NO. 4 ENGSTRÖM ETAL.: TAX COMPLIANCE AND LOSS AVERSION 149

In addition to this, we find the following empirical prediction concerning th

unconditional average deduction size (Eö(c,D)).

PREDICTION 5: (i) The unconditional average deduction size will kink upwa

at D = 0. (ii) The unconditional average deduction will always be higher on

deficit side.

PROOF:

Follows directly from Lemma 3 and Prediction 4. ■

When turning to the expected size of the conditional deductions (£[<5(c, D)\6 > 0] )

the model does not make any clear predictions. The reason is that there are two c

teracting effects. On the one hand, we know that a given taxpayer (i.e., a given

will make a larger deduction in the deficit domain. But on the other hand, the

age c, among those who claim a positive deduction, will be higher on the deficit

since the incentives to claim deductions are higher. Now, since Qc > 0 (the ma

ginal cost of a deduction increases in c), this will have a counteracting effect on

average size of the conditional deductions on the deficit side. Theoretically, ei

effect could outweigh the other. Consequently, we would expect to find both

largest and the smallest deductions on the deficit side, while the average conditi

deduction size may be both higher or lower on the deficit side.

C. Summarizing Theoretical Predictions

The model demonstrates that the incentives to claim a deduction are stronger

the loss than in the gain domain. The probability of claiming a deduction is hig

in the loss domain and kinks at D = 0. Also the unconditional amount deducted

is higher in the loss than in the gain domain and also kinks at D = 0. Concerning

the conditional amount, however, we do not have any clear theoretical prediction.

Assuming that the costs to claim the deduction are uniformly distributed among the

taxpayers, the coefficient of loss aversion, A could be estimated as the ratio between

the shares of taxpayers claiming the deduction in the loss and in the gain domain.

IV. Descriptives

Theory predicts that the share claiming deductions, under certain assumptions,

could be illustrated as in Figure 5. We note that the actual behavior presented in

Figure 1 is very similar to this. A larger share of those with a preliminary deficit

claims a deduction for "other expenses" than those with a preliminary surplus. The

share claiming a deduction is independent of the preliminary balance for those with

a surplus as predicted by theory. Less than 4.5 percent of those with a preliminary

surplus claim a deduction for "other expenses." The share is, however, increasing in

the preliminary deficit for those with a deficit.25

25 As this kind of deduction was practically riskless, the share of taxpayers claiming the deduction may seem

surprisingly low. However, Swedes have a high degree of tax morale in an international comparison. This might

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ISO AMERICAN ECONOMIC JOURNAL: ECONOMIC POLICY NOVEMBER 2015

120,000

90,000

0

>%

03

CL

X

Z

60,000

30,000

-3,000

-2,000

-1,000

0

1,000

2,000

3,000

Figure 6. Frequency Distribution of Preliminary Deficits

Moreover, theory predicts that more will be deducted in the loss than in the gain

domain and also that the amounts are more spread in the loss than in the gain domain.

From Table 2 and Figure 3, we learned that not only the share claiming deductions,

but also the conditional amount deducted is larger in the loss domain than in the

gain domain. Hence, unconditional deductions in the loss domain exceed those in

the gain domain as predicted by theory.

Although the observed patterns are in line with theory, we cannot be certain that

they are caused by the preliminary balance; there may be an endogeneity problem.

Plotting the distribution of individuals over preliminary deficits is a simple graphi

cal test of this: If the distribution changes dramatically around zero, the individuals

slightly above zero preliminary deficit will not be representative of those slightly

below. Figure 6 shows that the distribution does not seem to kink or jump at zero,

so at first inspection there is no indication of any selection or endogeneity problem.

We could, however, still have problems with selection that do not show up in the

frequency distribution plot. The individuals slightly below zero could be very dif

ferent from the individuals slightly above even if the distribution is smooth around

the reference point. We, therefore, need to look closely at how the covariates evolve

around the reference point. Suppose there is selection based on any of the covariates

or on any unobservable factor that is correlated with the covariates. This would show

up as a kink or discontinuity around zero. The pattern in Figure 1 could then be due

to selection. If, on the other hand, all covariates evolve smoothly around zero, the

deduction pattern is likely to be caused by differences in the preliminary balance.

Here we will present descriptive tests if the predetermined covariates show kinks

or discontinuities at zero preliminary balance. The formal econometric tests are pre

sented in Section V.

explain why many do not claim a deduction without actually having had any "other expenses" when the potential

gain is only a couple of thousand SEK.

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VOL. 7 NO. 4 ENGSTROM ETAL.: TAX COMPLIANCE AND LOSS AVERSION 151

400,000

[J]

W

-

300,000

--

--

--

-

Weighted

a

Unweighted

200,000

E

>

o

Q.

E

100,000

-3,000 -2,000 -1,000 0 1,000 2,000 3,000

Figure 7. Employment Income as a Function of the Preliminary Deficit

Employment income is a crucial variable. The diamonds in Figure 7 show

relationship between preliminary deficit and employment income. The kink slig

below zero preliminary deficit could be explained as follows. The higher the em

ment income, the more difficult it is to calibrate the tax payments at source correct

the deviations will be scaled up in proportion to the income. Higher employm

income will, therefore, move us further away from zero preliminary balance. Th

exactly the pattern we see in the unweighted version of the relationship.

The unweighted relationship in Figure 7 suggests that we do not have a

rect specification. It could be argued that the marginal utility of claiming a d

tion is higher for a low-income taxpayer. The mechanical kink that is visible

the unweighted relationship should, however, disappear if we instead mea

preliminary deficit in relation to employment income. We therefore define t

weighted preliminary deficit of taxpayer i as:

(10) 4- = (E/E) x D„

where Di is the unweighted preliminary defic

income of taxpayer i, and Ë is average employ

liminary deficit disappears when we measure

employment income; see the squares in Figure

The other conditioning variables do not seem

zero preliminary deficit. Figures 4 and 5 in on

matter whether we use unweighted or weighte

If we weight the preliminary deficit when w

the same when studying the outcome variable

diamonds from Figure 1, squares showing the

similar. Hence, from the graphs we conclude t

a lot at the point of zero deficit, while none of

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

152 AMERICAN ECONOMIC JOURNAL: ECONOMIC POLICY NOVEMBER 2015

0.08,

-3,000 -2,000 -1,000 0 1,000 2,000 3,000

Figure 8. The Share Claiming a Deduction as a Function of the Preliminary Deficit

This suggests that it is actually the deficit itself that causes the behavioral d

ence. However, this is not a formal test, so we continue to the next section, w

we use econometric methods to formally test causality.

V. Estimations

A. Baseline Models

In this section we formally test whether the observed relationship between

liminary deficits and deductions is causal and not due to selection. We follow s

of the empirical strategies suggested in previous work on the regression discont

ity design (Lee and Lemieux 2010) and regression kink design (Card, Lee, and Pe

2009). The empirical tests essentially consist of answering two questions:

• Does the relationship between the preliminary balance and deductions have

statistically significant kink or discontinuity around zero preliminary balan

Can we rule out corresponding statistically significant kinks or discontinuiti

for the predetermined covariates?

If the answer is "yes" to both these questions, it is reasonable to interpret t

relationship as causal.

We will study three, closely related outcome variables that were included in th

theoretical section: the probability of claiming a deduction—the extensive mar

the unconditional amount deducted; and the amount deducted, conditional on cla

ing a deduction. Recall that the theoretical model predicted positive kinks at ze

preliminary deficit for the first and second outcomes (the extensive margin and

unconditional size of deductions), while the theoretical predictions for the third

come (the conditional size of deductions) were ambiguous.

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VOL. 7 NO. 4 ENGSTROM ETAL.: TAX COMPUANCEAND LOSS AVERSION 153

Recall that theory does not predict any discontinuities at zero p

ance in the relation between preliminary deficit and any measure of

completeness, however, we also allow for potential discontinuit

metric specification. A positive discontinuity in, e.g., the probabi

a deduction would be consistent with a fixed subjective cost of en

preliminary deficit—a fixed cost of "losing." Even though such m

predicted by ordinary loss aversion, it would still be a clear indicat

dependence.

Formally, we estimate spline models of the following type (the a

ates: age and gender are suppressed):

(11) A,- — "Y^ctkdj -F ^jßklidf + €j,

k=0

where

4

is

A,

the

is

k=0

the

outcome

(weighted)

measures

the

variable,

preliminary

intercept,

ß0

/,

is

def

measures

(zero preliminary deficit), and ß\ m

The polynomial k ranges from 0, w

nuity at zero preliminary balance, t

ification should be appropriate very

flexible specifications, in particular

We iterate the estimation of each o

many bandwidths. Bandwidths go f

most and SEK ± 500 at the least. W

ence point.26 A bandwidth of SEK

with weighted preliminary balance

A large bandwidth gives a larger sam

A smaller bandwidth, on the other h

estimates. There are 1.2 million taxp

±

3,000)

as

previously

mentioned.

200,000 taxpayers with weighted p

The optimal nonzero polynomial m

determined based on minimizing a

mation criterion weighs better good

is

a

modification

freedom

the

data

two

harder.

best;

(zero).

of

only

Based

the

Akaike

Overall,

for

on

the

very

these

info

SBC

large

m

(s

findings,

estimates based on the linear mode

linear model are reported for a rang

Our primary interest is in the ß\ e

tions from Section III. The ßx param

26We use a logarithmic scale when we iterate ov

at lower bandwidths than at higher bandwidths a

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

154 AMERICAN ECONOMIC JOURNAL: ECONOMIC POLICY NOVEMBER 2015

2.9 2.5 2.2 1.9 1.6 1.4 1.2 1.1 0.9 0

Bandwidth, SEK thousands

Figure 9. Kink—Estimates of 0t on the Probability of Deducting

the reference point or, in other words, the kink. As mentioned above, we are also

interested in whether there is a discontinuity at the reference point. This is measured

by ß0.

Figures 9, 10, and 11 report our estimates of a possible kink at zero preliminary

balance, for the three separate outcome variables. Starting with the extensive mar

gin—the probability of claiming a deduction—we find the following. The estimated

kink is significant for all bandwidths except around SEK 700. The thick solid line

reports the estimated coefficients while the thin lines provide the limits of 95 percent

confidence intervals. The estimated coefficients remain stable and positive in a wide

range of bandwidths from SEK 2,500 to SEK 800. The estimate starts to fluctuate a

lot for very narrow bandwidths. However, the overall pattern indicates a stable and

significant positive kink in the deduction probability.

Turning to the second outcome variable—the unconditional deduction amount—

we find a very similar pattern. As seen in Figure 10, we estimate a positive and

stable kink throughout the whole range of bandwidths. The optimal model is linear

for bandwidths above SEK 800 and the estimates are significant for bandwidths

above SEK 900. We thus find clear evidence of a positive kink in the unconditional

deducted amounts.

For the third outcome variable—the amount deducted, conditional on deducting—

the results are much less clear, however. From Figure 11 it is apparent that the kink

estimates are generally insignificant and the point estimates fluctuate between pos

itive and negative. It is only for bandwidths above SEK 2,000 we find positive and

significant kink estimates. Furthermore, the zero order model is optimal for band

widths below SEK 1,800.

It is also possible, though our theory does not predict so, that there is a discon

tinuity in the relationship between the preliminary deficit and our three different

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VOL. 7 NO. 4 ENGSTROM ETAL.: TAX COMPLIANCE AND LOSS AVERSION 155

200

150

100

50

— ^ , ,y >✓

2.9 2.5 2.2 1.9 1.6 1.4 1.2

1.1 0.9 \0.8 JQ.7 O.e

* 0.5

-50

-100

Bandwidth, SEK thousands

Figure 10. Kink—Estimates of ß\ on the Unconditional Amount Deducted

600 '

400

- 200

c

0)

o

3=

©

O 2.9 2.5 2.2 1.9 1.6 1_.4^^1.2

TO

CD

ra -200

E

"So

LU

—400

-600

-800 '

Bandwidth, SEK thousands

Figure 11. Kink—Estimates of on the Conditional Amount Deducted

measures of deductions. Figures 1-3 in online Appendix B report our

of these. The empirical evidence of discontinuities at the reference point i

rather weak compared with the evidence of kinks. We find the strongest e

a discontinuity for the extensive margin, i.e., the probability of claimin

tion. Concerning the unconditional amount of deductions, Figure 2 shows

pattern. The discontinuity estimate decreases when the bandwidth decrease

overall level of significance is lower than in Figure 10. Finally, we find no

at all of a discontinuity in the conditional amounts.

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

156 AMERICAN ECONOMIC JOURNAL: ECONOMIC POUCY NOVEMBER 2015

We now turn to the corresponding estimates for the three covari

responding to Figures 9-11 and the figures in online Appendix B a

online Appendix C. The results for employment income show that t

is negative and significant for bandwidths between SEK 2,700 and

polynomial order would, in fact, be optimal for smaller bandwidths

ity estimate is only significant for a narrow range of bandwidths be

and SEK 1,000. We continue with the gender indicator. The opti

order is always one. There is a significant negative kink for large

discontinuity estimates are almost always insignificant.

The corresponding results for age show decreasing kink estimates

lower than SEK 2,500. The estimates become insignificant belo

of about SEK 1,400. The optimal polynomial order is one except

bandwidths. The discontinuity estimates are insignificant for band

SEK 1,900.

Let us compare the results for the two outcomes where our theory

(the extensive margin and the unconditional deduction amounts) w

sponding results for the covariates. The estimated kinks for the cov

more unstable. The results for the deduction probability and uncond

show a stable and significant kink for a wider range of bandwidth

covariates. Hence, these results suggest that we can make a causal i

the pattern we see in the data. However, the kinks for the covariate

about omitted factors. This is one of the motivations for the sensitiv

follows.

B. Sensitivity Analysis—Placebo Kinks and Discontinuities

The above analysis shows that the patterns predicted by prospect theory are sup

ported by data.27 However, we also find evidence of kinks and discontinuities—

albeit unstable over different bandwidths—for the covariates. This could be a sign of

selection. On the other hand, there is a risk that even small and economically insig

nificant estimates become statistically significant when the sample size is very large.

It is thus relevant to ask whether kinks and discontinuities at the zero reference

point are more pronounced than kinks and discontinuities at other reference points.

We, therefore, present estimates of kinks and discontinuities based on a range

of different placebo reference points. We let the reference points vary between

SEK —3,000 and SEK 3,000. The bandwidth—symmetric around the placebo refer

ence points—is fixed at SEK 1,000 in all regressions.

The analysis serves several closely related purposes. The evidence of causal

effects becomes stronger if we find that the kinks and discontinuities in deduc

tion measures (deduction probability and unconditional deduction size) are more

pronounced for the theoretically predicted reference point than elsewhere. We might

also fear that selection is driving the increase in deduction probability around zero

27The main analysis is made on all Swedes of working age, i.e., 16-67, but the results are robust to narrower

age grouping as well, such as 18-64 or 25-59 years. Results are available on request.

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VOL. 7 NO. 4 ENGSTRÖM ETAL. : TAX COMPLIANCE AND LOSS AVERSION 157

if the kinks and discontinuities for the covariates are more pronounced around

than elsewhere.

Figure 12 in online Appendix D shows the estimated kinks in deduction proba

bility for different placebo reference points. The kink-estimates peak slightly below

zero at a reference point of SEK —180, which we interpret as zero.28 When the pla

cebo reference point enters the deficit side, the kink estimates turn negative and sig

nificant for reference points in the range SEK 500-1,000. This is consistent with the

concave increase in the deduction probability for those with a preliminary deficit;

see Figure 1. The information criterion prefers a zero polynomial order for reference

points above SEK 1,700 and below SEK 1,000, and the linear model is preferred

elsewhere. The corresponding discontinuity estimates mirror the kink estimates.

There is a local peak in the discontinuity estimates for reference points close to zero

(see Figure 13 in online Appendix D).

Turning to the placebo estimates for the unconditional amounts, we find a sim

ilar pattern. The kink estimates peak slightly below zero preliminary deficit, just

as theory predicts. There are no significant kinks or discontinuities elsewhere (see

Figures 14 and 15 in online Appendix D). The last outcome variable, the conditional

amounts, shows no significant kinks or discontinuities at all (see Figures 16 and 17

in online Appendix D). This is also in line with the theoretical predictions.

To sum up the placebo estimations for the outcome variables, we can conclude

that the results for the three outcome variables are in line with theory.

We now turn to the corresponding analysis of the covariates (online Appendix D

has the figures). We find that neither kink nor discontinuity estimates are more pro

nounced around the zero reference point than elsewhere for any of the covariates.

We, therefore, conclude that selection is a very unlikely source of the increase in

deduction probability around zero. It would require very strong selection on some

unobservable factor to produce the pattern we see in Figure 1. It is hard to come up

with a candidate for such an unobservable factor. It is even harder provided that it

also needs to be virtually uncorrelated with employment income, gender, and age.

Flence, the deduction pattern is highly consistent with loss aversion where it is a

salient difference to people whether they will get a refund or have to pay more.

VI. Extensions

A. An Alternative IV Approach

The analysis in Section V strongly indicates that taxpayers behave in a loss av

manner when filing their tax returns. We find significant kinks and discontinu

in deductions, while the results for the covariates are less pronounced. Howev

they are not completely absent and although our placebo estimates suggest that

actually have causal effects, we also use an alternative IV strategy to corroborat

results. Using this alternative IV estimation, we are also able to estimate the co

cient of loss aversion, (A).

28 Incomes are rounded down to the nearest SEK 100 and refunds lower than SEK 100 are not paid out

deficits lower than SEK 100 are not claimed), so a preliminary balance e (-200,200) could be regarded as

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

158 AMERICAN ECONOMIC JOURNAL: ECONOMIC POUCY NOVEMBER 2015

The IV estimation makes use of the difference between t

ment income tax rate and the local employment income tax r

taxation at source that was discussed in Section II. Actual lo

ment income are set with two decimals (for example 30.83 p

rates at source, on the other hand, are rounded to the clos

31 percent). Taxpayers will tend to pay too much in prelim

in municipalities where tax rates at source are above the ac

the case in 151 of the 290 municipalities in 2006. The prelim

therefore, tend to be in surplus. The opposite applies to taxp

with actual rates above the rates used at source. We use the difference between the

actual and the preliminary rates as an instrument for a preliminary deficit indicator

when estimating probability models for claiming a deduction.29 We use two differ

ent instruments for the preliminary deficit indicator in the IV analysis: the difference

between the preliminary and actual local tax rates; and the interaction between the

first instrument and employment income. The second instrument can be interpreted

as the impact of the rounding on the preliminary balance—theoretically, the round

off error should matter more for high income earners than low income earners. The

IV analysis uses the full sample of 3.6 million taxpayers. The reason for using the

full sample is that sample inclusion should not be endogenous to the instrument.30

The OLS and baseline IV estimate use the standard set of controls, which now also

includes employment income; see the notes to Table 3 for details.31 The models with

interacted treatments also include all relevant interacted controls and instruments.

The upper part of Table 3 reports the estimation results for the probability of

claiming a deduction. The OLS estimate shows that having a preliminary deficit

increases the probability of claiming a deduction by 2.0 percentage points. This

estimate cannot, however, be causally interpreted since preliminary deficit may for

other reasons be correlated with the probability of claiming a deduction.

The causal estimate given by the IV estimation suggests an even stronger effect.

We estimate an impact of 5.0 percentage points. The loss aversion effect is probably

stronger for individuals close to zero (the salient reference point). Individuals fur

ther away from the reference point (both on the positive and negative side) probably

know which side of zero they will end up. When we simply compare the left-hand

side and right-hand side (i.e., OLS), these individuals will attenuate the estimate.

The IV estimate instead identifies the local average treatment effect (LATE), i.e., for

individuals close enough to zero so that the rounding error is pivotal for preliminary

deficit or surplus.

The estimation reported in the third column of Table 3 shows that there is a sig

nificant kink in the relationship between the probability of claiming a deduction

and the value of the preliminary deficit at zero preliminary deficit. The third column

addresses the exclusion restriction by focusing on the relationship above and below

29 In terms of our covariates, the municipalities rounding up and down do not differ statistically from each other.

30Note that the rounding off error affects the preliminary deficit. This means that sample inclusion based on a

bandwidth in the preliminary deficit dimension could make the rounded up sample different from the rounded down

sample in terms of unobservable characteristics.

Employment income was excluded from the Regression Kink and Discontinuity (RKD) models above since

they were based on the preliminary deficit weighted by employment income.

This content downloaded from 93.180.40.214 on Sun, 27 Oct 2019 18:36:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VOL. 7 NO. 4 ENGSTRÖM ETAL. : TAX COMPLIANCE AND LOSS AVERSION 159

Table 3—The Probability of Claiming a Deduction, IV Approach, Full Sample

OLS IV IV IV, gender IV, age IV, income

(1)

Positive

deficit,

(2)

0.020

0.050

preliminary

/,

indicator

(0.000)

(0.006)

(3)

-0.027

(0.046)

(4)

(5)

(6)

0.048

0.055

0.047

(0.007)

(0.010)

(0.007)

-0.0044

Preliminary deficit, £>,,

(0.0022)

amount

Interaction: