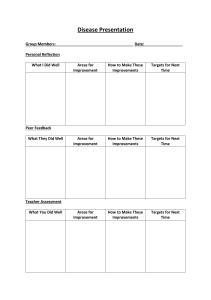

The Journal of Experimental Education, 2011, 79, 64–83 C Taylor & Francis Group, LLC Copyright ISSN: 0022-0973 print /1940-0683 online DOI: 10.1080/00220970903292884 MOTIVATION AND SOCIAL PROCESSES Impact of Discussion on Peer Evaluations: Perceptions of Low Achievement and Effort Todd M. Huenecke and Gregory A. Waas Northern Illinois University The authors placed 5th-grade students into small groups of 3 in order to examine the impact of group discussion and displayed effort on children’s evaluations of a lowachieving peer. Low effort by a target peer resulted in negative evaluations across attributional, affective, help-giving, and social response dimensions. Children who participated in group discussion before making individual evaluations exhibited a polarizing effect in which more extreme evaluations were made than when children did not participate in group discussion. Although all children were affected by both effort level and discussion conditions, gender differences were observed. These findings (a) highlight the importance of addressing the role of the peer group when working with low-achieving children and (b) underscore the impact of effort attributions and low achievement on peer perceptions among elementary-age children. Keywords: achievement, attribution, child development, individual differences, peers and peer influence, social context, social development CHILDREN WHO EXHIBIT low levels of academic achievement are at greater risk of social rejection by their peers than are normal-achieving classmates (e.g., Stone & La Greca, 1990; Vaughn, McIntosh, Schumm, Haager, & Callwood, 1993). A large body of research has examined the characteristics of low-achieving Address correspondence to Gregory A. Waas, Department of Psychology, Northern Illinois University, 1425 West Lincoln Highway, DeKalb, IL 60115, USA. E-mail: gwaas@niu.edu IMPACT OF DISCUSSION ON PEER EVALUATIONS 65 children that are associated with peer relationship difficulties (e.g., Kistner & Gatlin, 1989; Margalit & Levin-Alyagon, 1994). However, these efforts leave unaddressed the degree to which negative peer evaluations are based on a child’s low achievement itself or on characteristics that are often attributed to low-achieving children such as low effort. Moreover, this research has neglected important group social factors that may contribute to children’s evaluations of a struggling classmate. This failure to clearly delineate the ways in which children’s social interactions influence how they understand and respond to achievement information about a peer is unfortunate because school is the primary social setting for most children, and achievement-related information is likely to be available and salient to the peer group. In the present study, we sought to examine the unique impact of perceived low effort on children’s evaluations of a target peer and to investigate the role that children’s social discussion plays in the formulation of peer judgments about an at-risk child. Social Discussion and Individual Decision Making A large body of research has documented the impact of social discussion on attitudes, beliefs, and decisions among adults (e.g., Kerr, MacCoun, & Kramer, 1996). For example, group discussion has been shown to have both an attenuating and polarizing effect on group members’ attitudes depending on such factors as the characteristics of the group and decision-making task demands. Attenuation occurs when group discussion mitigates the tendency for individuals to make dispositional attributions about a target person (i.e., fundamental attribution error). Such an effect might result from group members correcting each other’s judgment errors or increasing individuals’ sensitivity to mitigating situational factors when evaluating the target person (e.g., Wright, Luus, & Christie, 1990). Polarizing effects, however, might also occur in which group discussion increases an individual’s tendency to make extreme judgments about an issue or a person. Among adults, group polarization may arise as a result of exposure to new information, reinforcement among group members, repetition of stated positions, and social perception factors (e.g., Brauer, Judd, & Gliner, 1995; Zuber, Crott, & Werner, 1992). Despite the extensive research that exists on the impact of social discussion on adults’ decision making, there has been virtually no empirical research on the influence of group discussion on children’s social perceptions of peers. Instead, previous research with children has tended to aggregate individual children’s evaluations of a target peer (e.g., calculate mean sociometric ratings) in order to estimate peer group perceptions. Such an approach is limited by its failure to account for the influence of children’s group interaction on their perceptions of a peer. Indeed, emerging research investigating the impact of social interaction modalities such as relational aggression and gossip underscore the importance of 66 HUENECKE AND WAAS such group-based processes in children’s peer evaluations (e.g., Crick, Ostrov, & Werner, 2006; Ostrov & Godleski, 2007). This influence of group social discussion is particularly relevant to older children. An extensive body of research has demonstrated that children engage in more psychologically complex discussions of peers as they get older. For example, whereas preschool children tend to tell stories about a peer that involve simple scripts and routines, elementary-age children make more extensive use of psychological (e.g., goals, motivations) and evaluative content in their stories (e.g., Engel & Li, 2004; Nelson, 1993). Including the effects of group discussion in analyses of peer evaluations is also important because such constructs as peer rejection are inherently social phenomena involving group interaction, which may be subject to group processes such as polarization and attenuation. One of the most pervasive types of information that school-age children share about each other—and use as the basis for peer evaluations—relates to academic performance (e.g., Gest, Domitrovich, & Welsh, 2005; Stipek & Mac Iver, 1989). Perceived Effort and Peer Evaluations Although many aspects of a child’s academic performance (e.g., concentration, problem-solving strategies) are not easily observable by the peer group, children are often aware of classmates’ stated attitudes, overt behaviors, and academic outcomes. One of the most likely cues children look to in an attempt to understand another child’s performance is observed effort (Newman & Spitzer, 1998). If an individual is observed to fail at an academic task while exhibiting low levels of effort, observers will tend to attribute control of and responsibility for his or her failure to the individual (Weiner, 1993). Moreover, because such failure could potentially be mitigated by greater effort, observers will also tend to experience low levels of pity and be unlikely to engage in helping behaviors. Last, there is an increased probability of anger and negative behavioral response by observers when failure is viewed as being due to low effort. Conversely, when an individual is perceived as exerting high levels of effort, observers are more likely to offer assistance (Weiner, 1980). Karasawa (1991) investigated the influence of perceived effort on peer responses by examining college students’ evaluation of three hypothetical scenarios in which peers were depicted as having academic difficulties arising from being sick, not trying, or trying and still failing. Participants provided attributions about the likely cause of the problem, ratings of their intentions to help the student, whether they would criticize or praise the student, and how much effort they believed the student had exerted. As predicted, low effort was perceived as a controllable cause, and raters reacted to failure outcomes as a result of low effort with anger, low pity, and a disinclination to help the peer. In an extension of Karasawa’s (1991) study, Bennett and Flores (1998) asked elementary and middle school children to imagine being a member of a IMPACT OF DISCUSSION ON PEER EVALUATIONS 67 partnership, working on an assigned project with a hypothetical peer depicted as either sick or exerting no effort, thus placing the assigned project in jeopardy. As expected, all children attributed more culpability and fault to the peer exhibiting low effort, and all children felt more anger, less pity, and were less willing to help the peer. Younger participants (third- and fourth-grade students), however, rated themselves as somewhat less angry and more willing to help the peer than were older participants (sixth- through eighth-grade students). These findings support the hypothesis that even elementary-age children are sensitive to displayed effort by their peers when such effort information is highly salient and the participant is directly affected by the peer’s level of effort and achievement outcome. Left unaddressed, however, is the degree to which children are responsive to effort information in more realistic academic settings in which direct dependency on the peer does not exist. In the present study, we examined children’s sensitivity and responsiveness to displayed effort cues that children are likely to encounter in day-to-day classroom interactions (e.g., work habits) but that do not involve dependency on the low-effort peer’s academic success. Bennett and Flores (1998) noted that any factor that increases the salience or effect of effort cues may have significant implications for social interactions such as help-giving behavior. One of the most common ways that a child’s effort and achievement outcomes might be highlighted among peers is through group discussion. As such, evaluating the influence of social discussion on children’s perceptions of a low-achieving target peer will provide greater understanding of one mechanism by which children form such peer evaluations and make decisions regarding social acceptance of a peer. The Present Study In the present study, we examined the influence of group discussion on children’s evaluations of a hypothetical low-achieving peer exhibiting either high or low effort. Participants were asked about their responses toward a hypothetical classmate across attributional, emotional, and behavioral dimensions. We hypothesized that participants would view the peer exhibiting low effort more negatively across affective, attributional, and interpersonal dimensions than the peer exhibiting high levels of effort, and that these differences would be magnified when participants had engaged in social discussion about the target peer. METHOD Participants A total of 120 fifth-grade students (M = 10 years, 8 months), equally divided by gender, participated in the study. Participants were from lower to middle socioeconomic status homes (43% eligible for free or reduced-price lunch) and 68 HUENECKE AND WAAS represented the ethnic composition of the community (85% Anglo American, 12% Hispanic American, 3% African American and Asian American). All children received informed parental consent and provided oral assent before their participation in the study. Target Peer Descriptions All participants heard descriptions of two hypothetical classmates depicted as experiencing academic failure. In the high-effort condition, the target peer was described as being compliant with task instructions, exerting maximum effort, and using class time efficiently. In the low-effort condition, the target peer was described as frequently not completing assignments, exhibiting low motivation, and exerting minimum effort. In both conditions, target peers were depicted as receiving poor grades and often having to redo class assignments. With the exception of effort level, the target peer descriptions were controlled for non–effort-related details, overall length, and readability level. Target peer descriptions are presented in the Appendix. Group Discussion Condition Participants were randomly assigned to either a discussion or no-discussion condition. Following each peer description, participants in the discussion condition engaged in a semistructured discussion. These discussions consisted of a trained interviewer prompting the group to discuss the target peer on the dimensions of academic performance (e.g., “Let’s talk about what kind of student he/she is, and how that affects his/her grades”), affective response (e.g., “How do you feel about him/her?”), and social inclusion (e.g., “Let’s talk about whether you would like to do things with him/her”). The group discussed each dimension for 3 minutes, and the interviewer ensured that all participants stated an opinion on each dimension. The interviewer provided up to two prompts if the group did not use the full 3 minutes, the discussion was off topic, or a specific member of the group did not contribute during the time allotted for discussion. During these discussion periods, children were generally willing to discuss the target peer, and in the majority of cases, children used the full 3 minutes allotted. Participants often related the information presented about the target peer to actual peers in their classrooms, and group discussions were most spontaneous and animated when children discussed their willingness to include the target peer in a social or academic group. The order in which evaluation dimensions were discussed was counterbalanced between groups. After the group discussion, participants individually completed the dependent measures. In the no-discussion condition, participants completed the dependent measures immediately after the peer descriptions. IMPACT OF DISCUSSION ON PEER EVALUATIONS 69 Dependent Measures Participants’ individual perceptions of and responses toward the low-achieving target peer were examined on seven dimensions used in previous research on children’s attributions (e.g., Juvonen, 1992; Karasawa, 1991; Weiner, 1980). These included the following: perceptions of the target peer’s effort level (e.g., How hard does Adam/Beth try to do well in school?); attributional beliefs about the target peer’s control over his or her academic performance (e.g., Could Adam/Beth have gotten better grades?); affective responses of anger (e.g., How mad would you feel toward Adam or Beth when he or she received a bad grade?) and pity (e.g., How sorry would you feel for Adam/Beth when he/she received a bad grade?) toward the target peer; willingness to include the peer as a group member in an academic setting (e.g., How much would you like to have Adam/Beth be in your group to do a science project?) and social setting (e.g., How much would you like Adam/Beth to be on your after-school soccer team?); and an estimation of the target peer’s ability level (e.g., How smart is Adam/Beth?). Participants rated the peer on each dimension using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a lot). Procedure Participants were randomly assigned to same-gender groups composed of 3 students (20 groups of boys and 20 groups of girls). Groups consisted of same-gender peers to reflect the composition of typical fifth-grade social affiliations. Individual groups comprised children from the same classroom so that all participants were familiar with other members and group discussion occurred among known peers. After completion of assent procedures, each group was orally read two peer descriptions (in counterbalanced order) describing a same-gender hypothetical peer who exhibited either high or low effort in conjunction with academic failure. After group discussion (in the discussion condition) or immediately after the peer description (in the no-discussion condition), participants were provided written response forms on which to record their ratings of the peer on the seven dependent measures. Each group received a randomly ordered set of ratings, with the exception of the ability item, which was always presented last. Participants were seated so that children were not aware of other group members’ ratings. After all participants completed the ratings for the first target peer, a distracter task was completed (i.e., children were asked to indicate three things they would most like to do with their best friend, and then share one choice with the group), and the process was then repeated for the second target peer. RESULTS To examine the impact of group discussion on children’s evaluation of the target peer, we conducted a series of 2 × 2 × 2 repeated measure analyses of variance in 70 HUENECKE AND WAAS which peer effort level, discussion condition, and gender served as the independent variables, with effort condition serving as the repeated measure. Children’s ratings of the target peer on effort, control, anger, pity, academic acceptance, social acceptance, and ability served as the dependent measures. Means and standard deviations for participants’ ratings on these measures are provided in Table 1. As an initial check of the displayed effort manipulation, participants were asked to rate the target peer on the degree to which they viewed the peer as trying to do well in school. As expected, participants in the high-effort condition viewed the peer as exhibiting significantly greater effort than did participants in the low-effort condition, F(1, 116) = 235.01, p < .001, η2 = .67. This strong main effect, however, was qualified by a three-way interaction involving effort condition, discussion condition, and gender, F(1, 116) = 9.17, p < .01, η2 = .07. Followup examination of the two-way interactions for male and female participants separately indicated that among girls only, a polarizing effect was observed in the discussion condition. As depicted in Figure 1, there was a greater discrepancy between girls’ effort ratings of high- and low-effort peers when engaging in group discussion of the peer than in the no-discussion condition, F(1, 58) = 12.60, p < .001, η2 = .18. 5 High Effort Peer Low Effort Peer 4 3 2 1 0 Discussion No Discussion Discussion Condition FIGURE 1 Discussion × Effort interaction among girls for ratings of effort. 71 4.27 (1.17) 4.17 (0.83) 2.97 (1.16) 1.93 (1.17) 3.83 (1.44) 3.47 (1.31) 3.23 (1.19) Boys Boys 3.63 (1.77) 3.83 (0.83) 2.83 (1.21) 2.43 (1.36) 3.77 (1.25) 2.93 (1.31) 3.17 (1.42) Girls No discussion 4.50 (0.97) 3.87 (0.86) 2.93 (1.36) 2.60 (1.19) 3.80 (1.19) 3.10 (1.52) 3.13 (1.14) High effort 4.53 (0.82) 3.80 (0.61) 2.93 (1.05) 1.67 (1.15) 4.30 (0.70) 2.87 (1.25) 3.60 (1.13) Girls Note. Standard deviations are in parentheses. Effort Control Ability Anger Pity Academic acceptance Social acceptance Peer rating Discussion 1.13 (0.35) 3.37 (1.40) 1.53 (0.86) 2.63 (1.43) 2.07 (1.14) 1.20 (0.41) 1.83 (1.15) Boys Boys 2.50 (1.69) 4.07 (0.91) 3.13 (1.38) 2.20 (1.13) 3.20 (1.21) 2.67 (1.56) 3.13 (1.41) Girls No discussion 1.47 (0.86) 3.67 (1.15) 1.57 (0.86) 3.00 (1.46) 2.07 (1.39) 1.50 (0.78) 2.30 (1.06) Low effort 1.20 (0.48) 3.63 (1.30) 1.90 (0.92) 2.33 (1.37) 2.03 (1.19) 1.53 (0.90) 2.17 (1.12) Girls Discussion TABLE 1 Means and Standard Deviations of Peer Ratings 72 HUENECKE AND WAAS As expected, children rated peers who exhibited low levels of effort in the context of school failure more negatively across all dimensions. They viewed the peer as having lower control, F(1, 116) = 4.28, p < .05, η2 = .04; having lower ability, F(1, 116) = 37.25, p < .001, η2 = .24; deserving less sympathy, F(1, 116) = 121.82, p < .001, η2 = .51; and more anger, F(1, 116) = 6.32, p < .05, η2 = .05. Moreover, participants were less likely to accept the low-effort peer in academic group activities, F(1, 116) = 78.41, p < .001, η2 = .40; and in social group activities, F(1, 116) = 41.69, p < .001, η2 = .26. These findings were qualified, however, by interactions involving both the participants’ gender and participation in group discussion about the peer. We found strong and consistent evidence for the hypothesized polarizing effects of social discussion about the low-achieving peer. As depicted in Figure 2, participants in the discussion condition were much more willing to accept the high-effort peer into a social activity than the low-effort peer, whereas this distinction was less pronounced in the no-discussion condition, F(1, 116) = 11.78, p < .001, η2 = .09. We found polarizing effects consistent with this pattern for academic acceptance, F(1, 116) = 7.88, p < .01, η2 = .06; feelings of anger toward the peer, F(1, 116) 4 High Effort Peer Low Effort Peer 3 2 1 0 Discussion No Discussion Discussion Condition FIGURE 2 Discussion × Effort interaction for ratings of social acceptance. IMPACT OF DISCUSSION ON PEER EVALUATIONS 73 = 3.87, p < .06, η2 = .03; and attributions about control, F(1, 116) = 4.91, p < .05, η2 = .04. Similar to the results for attributions about effort, we found three-way interactions for ratings of pity, F(1, 116) = 8.44 p < .01, η2 = .07; and ability, F(1, 116) = 4.79, p < .05, η2 = .04. We followed up these three-way interactions by examining the Effort × Discussion interactions for each gender separately, and these analyses indicated that only girls exhibited the polarizing effects of group discussion. As depicted in Figure 3, girls in the discussion condition were more sympathetic toward the high-effort peer than the low-effort peer, whereas this difference was less pronounced in the no-discussion condition, F(1, 58) = 19.46, p < .001, η2 = .25. We found a similar pattern for ratings of ability. Girls participating in discussion made a greater distinction between high- and low-effort peers, with high-effort peers being rated as having more academic ability, than did girls in the no-discussion condition, F(1, 58) = 9.14, p < .01, η2 = .14. Additional effects involving gender were found for participants’ willingness to accept the low-achieving peer into a student work group and attributions about the controllability of the peer’s academic performance. As depicted in Figure 4, we observed an Effort × Gender interaction for academic acceptance in that boys 5 High Effort Peer Low Effort Peer 4 3 2 1 0 Discussion No Discussion Discussion Condition FIGURE 3 Discussion × Effort interaction among girls for ratings of pity. 74 HUENECKE AND WAAS 4 High Effort Peer Low Effort Peer 3 2 1 0 Boys Girls Participant Sex FIGURE 4 Effort × Gender interaction for ratings of academic acceptance. were more negative (i.e., less willing to work with the peer on a group project) toward the low-effort peer than toward the high-effort peer, whereas this effect was not as pronounced among girls, F(1, 116) = 13.48, p < .001, η2 = .10. It is interesting to note, however, that we observed an opposite pattern in a Discussion × Gender interaction for academic acceptance, in that girls were more negative about the peer following discussion, whereas boys showed no discrepancy as a function of discussion condition, F(1, 116) = 4.31, p < .05, η2 = .04. Last, we observed an Effort x Gender interaction for attributions of controllability, in that boys viewed the high-effort peer as having greater control than the low-effort peer, whereas girls exhibited no differences in their ratings of the target peers, F(1, 116) = 5.59, p < .05, η2 = .05. DISCUSSION The primary goals of the present study were to examine the ways in which children’s perceptions of a low-achieving classmate’s academic effort influenced social evaluations about the peer and, in particular, the degree to which group discussion about the peer affected these social evaluations. We predicted that peers displaying IMPACT OF DISCUSSION ON PEER EVALUATIONS 75 low levels of academic effort would be viewed more negatively than would peers exhibiting high levels of effort, and social discussion would tend to have a polarizing effect on children’s evaluations across a wide array of social dimensions. These predictions were largely supported, and they have implications for both how we conceptualize low-achieving children’s peer relationships and possible interventions with children experiencing academic difficulties. The Impact of Perceived Effort on Evaluations The existence of peer-relationship problems among low-achieving children is well established in the research literature (e.g., Stone & La Greca, 1990; Vaughn et al., 1993). The present study demonstrated experimentally that elementary-age children were highly responsive and negative toward peers exhibiting low levels of effort in the context of school failure. Indeed, children exhibited less pity and greater anger toward the low-effort peer, and participants were less willing to accept the low-effort peer into both academic and social groupings. These findings are consistent with previous research involving both adults and children. Karasawa (1991), for example, reported strong and pervasive negative evaluations among college students when evaluating a peer described as falling behind on a class group project as a result of low effort. Bennett and Flores (1998) replicated these findings among elementary and middle school age children and reported that participants viewed a low-effort peer with greater anger, blame, and perceptions of responsibility. Participants also responded to the peer with less pity and less willingness to provide assistance. It is important to note that in these previous studies the hypothetical peer was depicted as being a member of a small group that included the study participant, and the group was described as working together on a required academic project. Participants, therefore, had a direct stake in the productivity of the peer, thus making the peer’s effort highly salient and the repercussions for low effort by the peer directly relevant to the welfare of the participant (i.e., peer’s performance would influence participant’s grade). In the present study, however, no such participant dependence on the peer was suggested in the hypothetical scenarios. Nevertheless, participants remained strongly influenced by the effort level displayed by the target peer across all evaluation dimensions, even those dimensions not related to academic achievement. Participants directed more anger and less pity at the low-effort peer, and they were less willing to include the peer in either academic or social activities. These findings are consistent with Weiner’s (1994) argument that attributions of effort implicate moral judgments about a target peer, and these judgments are most negative when low achievement is viewed as a consequence of low effort. The fact that children were resistant to including the low-effort target peer in 76 HUENECKE AND WAAS even nonacademic activities (e.g., a soccer game) highlights the generality of such evaluations among elementary-age students when considering the academic performance of peers. The fact that such negative and general evaluations were made even when the peer’s low effort had no consequences for the participant raters underscores the importance of effort cues among elementary-age children. It will be important for future researchers to explore the ways that children integrate such effort cues with other types of peer information such as ability, interpersonal, and emotional cues. It is interesting to note that participants tended to rate the peer exhibiting high effort as having greater academic ability and greater control over their level of achievement than the low-effort target peer. Although consistent with participants’ relatively positive view of the high-effort peer, these ratings conflict with the other key piece of information presented about the target peer, that he or she experienced academic failure despite high levels of effort. One may expect that when faced with the combination of information that a target peer is both failing and exerting high levels of effort, an observer would conclude that the peer actually had low academic ability and therefore relatively low control over achievement success. The failure of fifth-grade students in the present study to reach these conclusions may be related to children’s limited ability to differentiate between such constructs as ability, effort, and control. Several researchers, for example, have reported that before approximately 11 years of age, children tend to overestimate the power of effort in producing success and preventing failure, and they tend to conflate effort and ability (e.g., Kunnen, 1993; Normandeau & Gobeil, 1998; Skinner, 1990). Miller and Hom (1997) reported that only 28% of fourth-grade students exhibited an understanding of ability as “capacity” (i.e., ability constrains the effects of effort) in reasoning about a peer’s achievement, whereas by the sixth grade, 72% of children demonstrated this understanding. In the present study, among children at a transition age (M age = 10 years, 8 months), there appeared to be a strong tendency to conflate these constructs when evaluating the target peer. It may be that the developmental progression of children’s thinking about such concepts as achievement, effort, control, and ability is somewhat slower when carried out in more realistic social contexts in which children are required to coordinate multiple pieces of information about a target peer. One implication of these findings is that the impact of public attributions about a child’s effort and ability may be more complicated than once thought. Previous research has suggested that a teacher’s attribution of low effort in response to a child’s poor achievement would increase the child’s self-esteem, self-efficacy, and future effort on the task (e.g., Clark, 1997; Weiner, Graham, Stern, & Lawson, 1982). Moreover, Juvonen and Murdock (1993) reported that among eighth-grade adolescents, students were sensitive to attributions about effort and ability depending on whether the attributions were being used to explain success or failure and whether the attributions were being made to parents, teachers, or peers. Whereas IMPACT OF DISCUSSION ON PEER EVALUATIONS 77 adolescents were more likely to attribute academic success to high ability when communicating with parents or teachers, they were more likely to cite low effort as responsible for failure when communicating with peers. These different attributional patterns are likely the result of adolescents’ firm understanding of the compensatory relation between effort and ability, such that high effort resulting in failure is suggestive of low ability (Graham, 1990; Juvonen & Murdock, 1993). When communicating with peers, attributing failure to low effort may be a strategy for saving face; however, when communicating with teachers or parents, such a strategy would be more likely to evoke anger. For adolescents, therefore, a teacher’s strategy of attributing failure to low effort makes sense in that it promotes greater effort by the student on future tasks and preserves the preferred public image of the adolescent. However, among younger children, such as those in the present study, public attributions about low effort may have the paradoxical effect of further damaging peers’ opinion of the low-achieving child’s ability. Such public attributions may also lead to greater levels of anger, less sympathy, and more social rejection. These findings underscore the importance of teacher sensitivity to developmental differences in how children make use of social information about others and understand the public attributions that are common in the classroom. It will be important for future research to more clearly delineate the progression of children’s understanding and use of attributional information in the classroom context. Moreover, cultural differences in perceptions of effort and academic achievement (e.g., Taylor & Graham, 2007), and how these perceptions are integrated with other characteristics associated with social popularity and rejection await further investigation. We expected the negative implications of perceived low effort by a peer found in the present study, and these findings represent a direct extension of previous research efforts. However, children’s evaluations about each other typically take place in a social context involving social exchanges such as gossip, information sharing, and social inferences. By experimentally manipulating children’s discussion of a target peer in the present study, we were able to explore the impact of such discussion on children’s subsequent social evaluations. The Role of Social Discussion Children who participated in group discussion exhibited consistent polarizing effects across multiple dimensions of evaluation. For ratings of controllability, anger, and both academic and social acceptance, all participants who engaged in discussion made a greater distinction in their evaluations between high- and loweffort peers than did participants in the no-discussion condition. Similar polarizing effects were exhibited by girls only when rating the target peer on the dimensions of effort, sympathy, and ability. 78 HUENECKE AND WAAS Research on group discussion with adult participants has demonstrated that the social act of discussing beliefs and available information about a target person, a pending decision, or a controversial issue tends to influence group member’s attitudes, beliefs, and decision making (e.g., Crott, Szilvas, & Zuber, 1991; Wittenbaum & Stasser, 1995; Wright & Wells, 1985). However, previous research efforts have reported that group interaction can have either a polarizing or a corrective effect on participants’ judgments. For example, Wright and Wells reported that group discussion tended to reduce dispositional bias (i.e., the tendency to make dispositional inferences about a target other) among adults, and Wright et al. (1990) reported that participants who made judgments after a discussion of a target person’s behavior were less likely to manifest the consensus underutilization effect (i.e., under use of information about how others behave when considering the causes of a target’s behavior). Conversely, other researchers have reported increased polarization following group discussion (e.g., Brauer et al., 1995; Crott et al.; Zuber et al., 1992). To date, however, the degree to which such group discussion influences children’s judgments has been largely unaddressed. A number of explanations have been offered to explain the group polarization phenomenon including participants’ exposure to new information through discussion, repeated attitude expression, hearing other group members repeat and validate each others’ ideas, a desire to be consistent with group norms, and a variety of interpersonal processes (e.g., Brauer et al., 1995; Zuber et al., 1992). Kerr et al. (1996) noted that when a person is making judgments within the context of a group, the information-processing task is altered from that of individual decision making to one involving a variety of social interactive variables. For example, members are often concerned with maintaining group interpersonal relationships, and therefore issues relating to impression management may influence decisions, attentional processes are altered (e.g., distractions increase), other group members’ reactions to stated opinions may influence information processing, and articulating and defending one’s own views (and hearing others defend their views) may heighten awareness of alternative positions and information-processing strategies. Whereas the research on how such mechanisms influence decision making among adult group members is extensive, little is known about how such mechanisms might influence children’s attitudes and behaviors following group discussion. It is interesting to note that much of the previous research indicating the corrective influence of group interaction has involved groups reaching a collaborative decision representing the entire group. In the present study, however, children maintained their independence to formulate their own conclusions about the target peer following group discussion. This difference in the nature and task demands of the group experience may account for the fact that polarization was observed in the present study. Children participated in a fairly structured discussion in which all children articulated their opinions about the target peer’s achievement, effort, and possible motivation. The repetitive exposure to fellow group members’ IMPACT OF DISCUSSION ON PEER EVALUATIONS 79 viewpoints on these issues may have served to reinforce more extreme views of the peer than if evaluations were made without group discussion. This possibility is consistent with Brauer et al. (1995), who suggested that exposure to repeated expressions of an attitude may be an important mechanism in shifting individuals’ judgments. This phenomenon is particularly relevant to the group discussions in the present study specifically but also to the nature of children’s reputation information exchange more generally. In our study, children engaged in a discussion of the peer that involved a substantial amount of repetition of participants’ expressed views of the target peer. Brauer et al. reported that such repetition and validation of views in the context of group discussion is partly responsible for the group polarization effect. When considered in the context of how children likely communicate with one another about a target peer’s academic performance, these findings shed light on one mechanism by which low-achieving children may be socially ostracized by their peers. Children’s informal communication and gossip about another peer’s academic struggles likely involve a high rate of repeated observations and judgments about the peer rather than reflective analysis of the peer’s performance. Such repetition of stated viewpoints is precisely the kind of information exchange that Brauer et al. (1995) found to be instrumental in generating more extreme judgments of a target peer. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that in the absence of a precise verbal record of the participants’ discussions, it is impossible to draw firm conclusions about the specific mechanism by which social discussion resulted in the observed polarizing effect. However, the present findings that children’s discussions have such a polarizing effect on their judgments of a peer underscore the importance of future research more closely examining the impact of social interactions on peer perceptions. It is interesting that, although evidence of the polarizing effect of discussion was found among all children for ratings of anger, attributions of controllability, and willingness to accept the peer into an academic work group, the polarizing effect only among girls was found for ratings of pity, ability, and effort. These findings may suggest a somewhat greater sensitivity and responsiveness of girls to the effects of group discussion. This possibility is consistent with reported gender differences in social interactions in that the peer relationships of girls are characterized by higher levels of intimacy and self-disclosure than are the social relationships of boys (e.g., Underwood, 2004). In contrast with girls’ greater sensitivity to the group discussion manipulation, boys were found to be somewhat more responsive to the effort manipulation for attributions of control and academic acceptance. Juvonen and Murdock (1993) suggested that effort attributions may be related to perceptions of competitiveness, and in the present study children tended to view low effort as associated with lower ability. These findings may suggest that boys are more sensitive to peer-related social information that has relevance for competitive success. As such, boys were 80 HUENECKE AND WAAS less willing to accept the peer into an academic work group in which the peer’s relatively low effort, control, and ability might negatively impact the participant’s own grade. Although the reasons that girls may be more responsive to discussion and boys may be more responsive to effort cues remain speculative, these findings underscore the possibility that older elementary-age children may exhibit genderbased differences in how social information about a peer’s academic performance is processed and used during the formulation of judgments about the peer. The precise nature and implications of such differences for classroom based practices, as well as academic interventions, remains for future research. Last, it is worth noting that although we demonstrated the effects of group discussion on peer perceptions of a child exhibiting low achievement, these findings may also be relevant to the effects of social information exchange through group discussion for other child characteristics relevant to peer relationships. For example, it is well established that such characteristics as aggression, impulsivity, and other externalizing behavioral difficulties are strongly related to negative peer perceptions (e.g., Parker & Asher, 1987). Moreover, it has been widely reported that improving the social acceptance of children exhibiting such difficulties is a major challenge for clinicians (e.g., Bierman, 2004; Weisz, Weiss, Han, Granger, & Morton, 1995). The present findings regarding the impact of group discussion may point to one mechanism by which a child’s negative reputation is propagated, and even increased, among the peer group. It will be important for future research to examine the role of social discussion in peer evaluations of other characteristics that are relevant to peer relationships, and for both researchers and clinicians to incorporate the role of the peer group into their treatment planning for such at-risk children. To this end, it will be useful for future research efforts to examine the precise mechanism by which social discussion influences children’s social decisions. Audiotaping and coding of children’s group discussion will allow for a more precise analysis of why such polarization occurs and may contribute to the development of interventions that target peer perceptions of at-risk children. A more detailed assessment of children’s perceptions and attitudes toward the low-achieving peer will also be important in future research efforts. The use of structured interviews, for example, would provide greater insight into what dimensions of evaluation are most relevant to the group polarization process. Finally, although this study is useful in experimentally documenting the impact that children’s low effort and group discussion may play in peer evaluations, it will be important to replicate and extend these findings in the naturalistic environment of the classroom. AUTHOR NOTES Todd Huenecke is a practicing school psychologist in the Western suburbs of Chicago with research interests in the areas of social perception and decision IMPACT OF DISCUSSION ON PEER EVALUATIONS 81 making. Gregory Waas is an associate professor in the Department of Psychology at Northern Illinois University with research interests in children’s peer relationships and social cognition. REFERENCES Bennett, T. R., & Flores, M. S. (1998). Help giving in achievement contexts: A developmental and cultural analysis of the effects of children’s attributions and affects on their willingness to help. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90, 659–669. Bierman, K. L. (2004). Peer rejection. New York: Guilford Press. Brauer, M., Judd, C. M., & Gliner, M. D. (1995). The effects of repeated expressions on attitude polarization during group discussions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 1014–1029. Clark, M. D. (1997). Teacher response to learning disability: A test of attributional principles. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 30, 69–79. Crick, N. R., Ostrov, J. M., & Werner, N. E. (2006). A longitudinal study of relational aggression, physical aggression, and children’s social-psychological adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34, 131–142. Crott, H. W., Szilvas, K., & Zuber, J. A. (1991). Group decision, choice shift, and polarization in consulting, political, and local political scenarios: An experimental investigation and theoretical analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 49, 22–41. Engel, S., & Li, A. (2004). Narratives, gossip, and shared experience: How and what young children know about the lives of others. In J. Lucariello, J. Hudson, R. Flvush, & P. Bauer (Eds.), Development of the mediated mind: Sociocultural context and cognitive development (pp. 151–174). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Gest, S. D., Domitrovich, C. E., & Welsh, J. A. (2005). Peer academic reputation in elementary school: Associations with changes in self-concept and academic skills. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97, 337–346. Graham, S. (1990). Communicating low ability in the classroom: Bad things good teachers sometimes do. In S. Graham & V. S. Folkes (Eds.), Attribution theory: Applications to achievement, mental health, and interpersonal conflict (pp. 17–36). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Juvonen, J. (1992). Negative peer reactions from the perspective of the reactor. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84, 314–321. Juvonen, J., & Murdock, T. B. (1993). How to promote social approval: Effects of audience and achievement outcome on publicly communicated attributions. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85, 365–376. Karasawa, K. (1991). The effects of onset and offset responsibility and effects on helping judgments. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 21, 482–499. Kerr, N. L., MacCoun, R. J., & Kramer, G. P. (1996). Bias in judgment: Comparing individuals and groups. Psychological Review, 103, 687–719. Kistner, J. A., & Gatlin, D. (1989). Correlates of peer rejection among children with learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 12, 133–140. Kunnen, S. (1993). Attributions and perceived control over school failure in handicapped and nonhandicapped children. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 16, 113–125. Margalit, M., & Levin-Alyagon, M. (1994). Learning disability, subtyping, loneliness, and classroom adjustment. Learning Disability Quarterly, 17, 297–310. Miller, A. T., & Hom, H. L. (1997). Conceptions of ability and the interpretation of praise, blame, and material rewards. Journal of Experimental Education, 65, 163–177. 82 HUENECKE AND WAAS Nelson, K. (1993). Events, narratives, memory: What develops? In C. Nelson (Ed.), Memory and affect in development: The Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology (Vol. 26, pp. 1–24). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Newman, R. S., & Spitzer, S. (1998). How children reason about ability from report card grades: A developmental study. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 159, 133–146. Normandeau, S., & Gobeil, A. (1998). A developmental perspective on children’s use of causal attributions in achievement-related situations. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 22, 611–632. Ostrov, J. M., & Godleski, S. A. (2007). Relational aggression, victimization, and language development: Implications for practice. Topics in Language Disorders, 27, 146–166. Parker, J. G., & Asher, S. R. (1987). Peer relations and later personal adjustment: Are low accepted children at risk? Psychological Bulletin, 102, 357–389. Skinner, E. A. (1990). What causes success and failure in school and friendship? Developmental differentiation of children’s beliefs across middle childhood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 13, 157–176. Stipek, D., & Mac Iver, D. (1989). Developmental change in children’s assessment of intellectual competence. Child Development, 60, 521–538. Stone, W. L., & La Greca, A. M. (1990). The social status of children with learning disabilities: A reexamination. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 23, 32–37. Taylor, A. P., & Graham, S. (2007). An examination of the relationship between achievement values and perceptions of barriers among low-SES African American and Latino students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99, 52–64. Underwood, M. K. (2004). Gender and peer relations: Are the two gender cultures really that different? In J. B. Kupersmidt & K. A. Dodge (Eds.), Children’s peer relations (pp. 21–36). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Vaughn, S., McIntosh, R., Schumm, J. S., Haager, D., & Callwood, D. (1993). Social status, peer acceptance, and reciprocal friendships revisited. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 8, 82–88. Weiner, B. (1980). May I borrow your class notes? A attributional analysis of judgments of help giving in an achievement related context. Journal of Educational Psychology, 72, 676–681. Weiner, B. (1993). On sin versus sickness: A theory of perceived responsibility and social motivation. American Psychologist, 9, 957–965. Weiner, B. (1994). Ability versus effort revisited: The moral determinants of achievement evaluation and achievement as a moral system. Educational Psychologist, 29, 163–172. Weiner, B., Graham, S., Stern, P., & Lawson, M. E. (1982). Using affective cues to infer causal thoughts. Developmental Psychology, 18, 278–286. Weisz, J. R., Weiss, B., Han, S. S., Granger, D. A., & Morton, T. (1995). Effects of psychotherapy with children and adolescents revisited: A meta-analysis of treatment outcome studies. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 450–468. Wittenbaum, G. M., & Stasser, G. (1995). The role of prior expectancy and group discussion in the attribution of attitudes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 31, 82–105. Wright, E. F., & Wells, G. L. (1985). Does group discussion attenuate the dispositional bias? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 15, 531–546. Wright, E. F., Luus, C. A. E., & Christie, S. D. (1990). Does group discussion facilitate the use of consensus information in making causal attributions? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 261–269. Zuber, J. A., Crott, H. W., & Werner, J. (1992). Choice shift and group polarization: An analysis of arguments and social decision schemas. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 50–61. IMPACT OF DISCUSSION ON PEER EVALUATIONS 83 APPENDIX Target Peer Descriptions High effort (boy version): When you are in class, you notice that Adam is usually working on the things he is supposed to. Last week you were sitting with Adam when the teacher gave an assignment; he started to work on it right away. The other day, when you worked on a project with Adam, he worked really hard. You noticed that when the class has an assignment, Adam uses the whole class period. He said that he wants to try really hard to do a good job. When he doesn’t understand something, he asks the teacher for help. When you sit next to Adam and you get your papers back, you see that he gets bad grades. Sometimes he has to do assignments over because he did them wrong the first time. Low effort (girl version): Whenever you look over at Beth, it seems like she is hardly ever working. The other day the teacher was collecting everyone’s papers, and Beth didn’t turn hers in. Later, when you were working with Beth, you noticed that it was hard to get her to try very hard. When you work next to Beth, it seems like she takes a long time to get started. One time, you saw Beth just write some answers down and put the assignment away. She said she didn’t understand it anyway, but she didn’t even ask for help. Other kids told you that Beth gets bad grades. One time you saw her homework, and the teacher wrote a note saying that she had to do it over. Copyright of Journal of Experimental Education is the property of Taylor & Francis Ltd and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.